24

28

Publisher Jim Burch

Editor

Dennis Burch

Design & Layout

Field Representative

Lendall & Sue Scott

Contributing Writers

Mike Bell

Jeffrey Bradley

Charlie Francis

Sarah Meredith

James Nalley

Brian Swartz

24

28

Publisher Jim Burch

Editor

Dennis Burch

Design & Layout

Field Representative

Lendall & Sue Scott

Contributing Writers

Mike Bell

Jeffrey Bradley

Charlie Francis

Sarah Meredith

James Nalley

Brian Swartz

by James Nalley

by James Nalley

At the time of this publication, Mainers will have survived yet another set of winter and mud seasons. This brings to mind the well-known line from Thomas Tusser’s 1157 poem, A Hundred Good Points of Husbandry: “Sweet April showers Do spring May flowers.” Although it would be more appropriate for Maine to write “Sweet April [mud] Do spring May flowers,” the end result is the same: It is time to take out the vases and brighten up your home with some colorful flowers.

In this regard, May is tulip season in Maine. According to Andy Brand, Curator of Living Collections at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens in Boothbay, tulip bulbs are usually planted in the fall before the ground freezes and by planting varieties with different bloom times, there will be tulips blooming from early to late spring. In addition, “tulips are divided into classes based on bloom time and form. One of the most intriguing classes is the fringed tulip, with Cummins as a fine example. Each lavender-violet petal is adorned with frilly white fringes that reminds me of frost crystals on a chilly spring morning.”

In general, tulips are cup-shaped

with three petals (the parts of a flower that are often colored) and three sepals (the outer parts of a flower that enclose a developing bud). There is also just about a tulip for every setting, ranging from small ones in woodland areas to larger ones in formal garden beds. Moreover, the upright flowers, which grow one per stem, can vary in shape from simple cups and bowls to complex goblets. As for their height, they can range from 6 inches to 2 feet.

Among the many beautiful varieties, there are the wild tulips, such as Lilac Wonder, which are small (3 to 8 inches) and tougher than hybrids. Triumph hybrids are the typical single, cup-shaped tulips that make up the largest grouping of the flower. They include: Calgary, with snowy-white petals and bluegreen foliage; Ile de France, with red blooms on stems that can be up to 20 inches; and Cracker Tulip, with purple, pink, and lilac petals.

Finally, with all of this information on tulips, why not expand your knowledge a bit more? First, as stated in the Almanac by Yankee Publishing, “If you dig up a tulip bulb in late summer, it is probably not the same bulb you planted last fall. It is her daughter. Even while the tulip is blossoming, the bulb is di-

viding for the next generation.” Second, in 17th-century Holland, the newly discovered tulip was “such the rage and fashion that a handful of bulbs was worth approximately $44,000” (in today’s economy).

On this note, let me close with the following jest: A bagpiper was asked by a funeral director to play at a graveside service for a homeless man with no family or friends. The funeral was to be held at a remote cemetery and this man was the first to be laid to rest there. Since the bagpiper was unfamiliar with the area, he became lost. He eventually saw a backhoe and crew, even though a hearse was nowhere in sight. Anyway, he apologized, threw a tulip in the open grave, and played the songs with his heart and soul. Meanwhile, the workers gathered around and started to weep. After he finished, he said a short prayer, packed his bagpipes into his car, and drove off. After he left, one of the workers said, “Sweet Jesus! I’ve never seen nothin’ like that!...and I’ve been putting in septic tanks for 20 years!”

The story of Silas Soule, a native son of Maine, is a fine example of quiet courage and patriotism of the highest order. Born into an illustrious New England family, Soule was one of many who migrated west and participated in the border wars that foretold the coming of the Civil War. His service in the Union volunteers in Colorado during that war would bring him face to face with evil itself and lead to martyrdom.

Born in Bath in 1838, Silas Soule was raised both in Maine and later in Massachusetts. He was descended from George Soule, who had arrived aboard the Mayflower as an indentured servant in 1620. The Soule family returned

to Freeport where they were part of a utopian farming community that led to little success. By the middle of the 1850’s, as slavery consumed the public spaces of debate, Silas and others of his family went west to work to contain the spread of this evil process.

Young Soule was involved in a variety of anti-slavery events in “Bleeding Kansas.” His leadership during a raid to secure an imprisoned abolitionist leader led to some renown. Those skills would lead him to consider a daring rescue of imprisoned members of John Brown’s failed raid in 1859. Brown refused the rescue, preferring to become a martyr. Soule’s focus soon turned to other pursuits and he found himself in Colorado

in a gold rush that held great promise, but little by way of results.

When the war between the states began, Soule volunteered for the Union army. He saw action at the Battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico territory in March of 1862. The leadership he developed in Kansas and demonstrated in combat led to rapid promotion. During the years of Civil War, troubles between native peoples and the onslaught of white explorers, farmers and thrill seekers were inflamed, and the governor of Colorado, John Evans, called for military action. Soule was part of an expedition that tracked down a village of Cheyenne and Arapahoe along Sand Creek in southeast Colorado. Col. John Chivington, nicknamed the “fighting parson” lead his troops, including Soule, into a sleeping village of natives and brought such death and destruction that later accounts would make even the most removed eastern

establishment types blanch.

While most of the men were away from camp, soldiers shot elders and women, and savagely killed even babies, all while a white flag and US flag flew above the village. Captain Soule refused to participate in the slaughter and ordered the men under his immediate command to stand down. In the months ahead, Soule would voice his concerns about the events in letters and testify against Chivington as part of an army investigation in January 1865.

The letter that Soule penned to his former colleague, Major Ned Wynkoop, was unsparing in its disgust about the massacre. In horrifying detail, he described the blood lust that seemed to have taken hold of the men as they attacked the village at Sand Creek. He would repeat the charges to the army investigators. The repercussions from his testimony and that of others, had wide ranging impacts. Chivington soon

left the army, and even territorial governor Evans was forced to resign. Silas Soule stood his ground and stayed his course. His life took a positive twist when he married Miss Theresa Coberly on April 1, 1865. On the evening of Sunday April 23, just three weeks after his wedding, Soule was out and about in the streets of Denver. He and his bride had been out earlier that evening and she had been escorted home.

Soule, as Provost Marshal for Colorado, went to investigate a disturbance at what is now 15th and Arapahoe in downtown Denver. There he encountered two men. In an apparent effort to disarm the men, Soule drew his weapon. In his own defense, he fired, hitting one of the other men in the hand. That man, a soldier whose name I shall not mention, then fired, hitting Soule in the head. Silas Soule was dead before he hit the ground.

To this day, historians debate wheth(cont. on page 6)

(cont. from page 5)

er the shooting was just another event in the daily life of a growing western city or was it a hit on Soule from people he had angered post Sand Creek. The jury is still out. To this day Silas Soule is honored for his courage by those he refused to fire upon. The Arapaho and Cheyenne nations have, in the past, honored Soule with a peace run to the battlefield at Sand Creek.

A plaque in Denver at the junction of 15th and Arapahoe recalls his death. And there is a movement to rename Mt. Evans along the front range. One of the other names mentioned is Mount Soule. Silas Soule rests today far from his home state of Maine. The good people of Colorado care for his mortal remains as he cared for their safety so many years ago. It is, as a great American once said, altogether fitting and proper that they should do this.

The town of Yarmouth is one of the oldest seaports on the Maine coast. It is a town of quiet, treelined streets and gracious old homes as well as bustling new businesses that lies just a bit off the beaten track. To reach Yarmouth it is necessary to leave the main highway, and in doing so the traveler may feel that he or she has taken a step back in time. It is a step away from the faster-paced life of the larger communities of the region and back into a time when life revolved around the changes of the seasons. When visiting the town today, it is somewhat difficult to visualize it as it once was — one of the most important ports in the world, a port where fishing and merchant vessels

once filled its harbor as they loaded and unloaded cargo. Nor is it easy to see it as a town where its earliest settlers lived in fear of their lives. Yet that is Yarmouth. But what Yarmouth? Or better yet, which Yarmouth, for there is more than one.

The above description could be that of any of four towns bearing the name Yarmouth. The oldest of the four, all of which are seaports, is, of course, Yarmouth, England. The next oldest is usually identified as Yarmouth, Massachusetts. The last two are Yarmouth, Nova Scotia and Yarmouth, Maine. Which of the latter three is older depends on one’s viewpoint, however. Yarmouth, Nova Scotia was incorporated as a town before Yarmouth, Maine. The Maine town was first called Westcustago by the settlers who arrived there at the same time as those who settled Yarmouth on Cape Cod. When the name was changed here in Maine, it was originally called North Yarmouth to distinguish it from the one (cont. on page 12)

(cont. from page 11)

on Cape Cod. But both towns in the United States were settled before the Canadian Yarmouth.

Strictly speaking, all four towns named Yarmouth bear a name that denotes a geographical location at the mouth of a river. The river is the river Yare. Yare is an old English word meaning nimble, which certainly fits for Yarmouth, Maine, as the Royal River is as nimble a river as the Yare in England. Neither of the other towns named Yarmouth, however, are graced by anything resembling a river, much less a nimble one.

One of the newer initiatives in furthering the development of international goodwill is the sister-city movement where towns far removed from each other declare themselves adopted. For example, Cooperstown, New York, which calls itself the birthplace of baseball, and Windsor, Nova Sco-

tia, which claims a similar distinction as the birthplace of hockey, are sister cities. In like manner, a mini cottage industry has sprung up with coffee-table books filled with pictures and descriptions of towns bearing like names. In fact, one of the first of these, Towns of New England and Old England, had as its centerpiece Yarmouth, England and Yarmouth, Massachusetts. However, it made no mention of either Yarmouth, Nova Scotia or Yarmouth, Maine, each which have many similarities to the first town bearing the name of Yarmouth as well as to each other and the Yarmouth on Cape Cod.

All of the towns bearing the name Yarmouth first owed their livelihood — at least in part — to fishing. The first settlers on the Royal River, as it was first known, named after William Royall, began arriving in the 1630s due to the reports of the area’s abun-

dant timber, game, and fish. While the same attractions led to the settlement of the other Yarmouths, that is just the beginning of the coincidences linking the four.

The residents of Yarmouth, England suffered early on from the depredations of marauding Danes. In like manner the earliest residents of Yarmouth on the Cape and Yarmouth in Nova Scotia lived in fear of Indian attack. The Plantation of North Yarmouth in the District of Maine was attacked and destroyed three times by Indians. Each time, however, the settlers returned to rebuild their log cabin homes. In fact, one of the most famous settlers of North Yarmouth, an Indian Scout named Joseph Weare, whose brother-in-law was killed by Indians, vowed to kill an Indian for every drop of blood lost by his brotherin-law.

One of the most unique coincidenc-

es involving all four of the Yarmouths involves John Winthrop, the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Winthrop, as governor of the colony, was, of course, often seen on the dirt roads of the Cape Cod Yarmouth. Winthrop also visited the other three Yarmouths.

John Winthrop sailed on the Arbella for the New World from Yarmouth, England. The Bay Colony claimed jurisdiction over Maine and established trading posts at Cushnoc (Augusta) and Castine. Winthrop stopped at Westcustago at least once on his way further downeast and even sailed to the Bay of Fundy, landing near the future site of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia to investigate the possibility of establishing an English presence there to counter that of the French at Port Royal.

All four towns named Yarmouth are almost synonymous with the sea. In fact, a character in a novel once

said, “If land [in Yarmouth] had been a little separated from the sea, and the town and the tide had not been quite so mixed up, like toast and water, it would have been much nicer.” Later this same character did say he had done the town an injustice.

The character was Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield. Dickens must have had a special place in his heart for Yarmouth, England for he used the town as a setting several times. In fact, his description of Mr. Peggotty’s house, which was actually a derelict ship on the Yarmouth shore, is one of the most famous in all literature.

Charles Dickens visited Massachusetts, Maine, and Nova Scotia. There is no record of his ever having actually visited the Yarmouths bearing the name of that oldest one in England. One wonders how he might have described them had he done so.

Asharp-eyed Brunswick police officer shut down a daring, but slightly incompetent gang of car thieves working across the Northeast in autumn 1921. On Tuesday, October 18, John Adams of Potsdam, New York noticed that his Ford touring car had gone missing. He certainly had not lent the expensive automobile to anyone, so he reported it stolen, and the Potsdam Police Department issued an APB. Brunswick Police Chief William B. Edwards was on duty on Tuesday morning, October 15, when Topsham selectman E. W. Mallett reported that someone had entered his garage overnight and stolen a blanket, a can con-

taining five gallons of oil, and two inner tubes. Edwards realized that based on the theft, someone’s automobile had suffered two flat tires and a major oil leak. Now where would such a damaged vehicle be located?

Edwards soon stopped by the Eagle Garage in Brunswick. Inside was a badly damaged Ford with “a broken mud guard, [a] bent forward axle, [and a] damaged running guard and radiator.” The Vermont license plate attached to the Ford’s rear read “30-146,” and someone had written “the same number” on the “pasteboard card” attached to the front of the touring car. Its lights were illegal in Maine.

Edwards queried the mechanics, who reported that about 11 p.m., Monday a man had called the garage to send a tow truck to bring in the Ford, badly damaged after colliding with another vehicle “near the cement bridge on the Federal highway in Topsham.” Edwards decided to wait.

A short while later “three young men” entered the Eagle Garage and asked the mechanics how the Ford repairs were coming along. Edwards approached the men and asked their names. William James Tyro was from Cornwall, Ontario and William Kennedy McGatrey was from somewhere in New Jersey. William E. Kersey was

from Rumford.

Let’s see your drivers’ licenses, please, Edwards asked.

The three men apparently patted their pockets and checked their wallets before admitting they could not produce one single license. Edwards promptly ran them to the Brunswick police station and locked ’em up that early afternoon.

A message brought Selectman Mallett to the Eagle Garage. Searching the Ford, he found his two missing inner tubes. Thieves the trio definitely were.

Edwards questioned the suspects, who admitted they had picked up Kersey in Rumford, where the two outof-staters had arrived and conned the locals out of money. A strike was under way at the Rumford paper mill; claiming they were strike-breakers, Tyro and McGatrey told F. E. Kenney, the strike committee’s treasurer, that they would leave town if given money to buy gas

and oil.

Promised a free ride to Boston, where he hoped to find work, Kersey collected $8 from unsuspecting Rumford residents. He climbed into the Ford touring car, and Tyro and McGatrey headed south. Edwards contacted the Rumford police, who “gave Kersey an excellent recommendation,” so the Brunswick chief let him go.

As for that Ford: We paid a guy named Kenney $100 for that car in Barre, Vermont, Tyro and McGatrey claimed. Nah, that doesn’t fly, Edwards figured. He called the Barre police chief, “who had never heard of any of the trio.” Edwards then called the Vermont secretary of state’s office and learned that the license plates had been issued to Harry F. McLain, who lived in Topsham, Vermont.

Summoning witnesses to the Brunswick police station on Wednesday, Edwards individually questioned Tyro and

McGatrey. Their stories switched back and forth until they realized the jig was up.

I confess, each perp admitted. They claimed that they and Kenney (a madeup person, his name based on F. E. Kenney’s) had stolen Adams’ Ford. Kenney (who had a license) supposedly drove them to Burlington, Vermont, where they substituted the stolen Vermont plates for the New York plates. Angry that Kenney would not let them drive, Tyro and McGatrey again “stole” the Ford after their companion stepped into a local store.

The perps meandered south to Boston, then north to “Lewiston, Rumford and other places” and hoped to sell the Ford for $150. After selling the car, Tyro and McGatrey intended to steal a Maine-licensed car, attach the Vermont plates to it, and sell that stolen car in New York State.

Edwards telegraphed the Potsdam (cont. on page 18)

(cont. from page 17)

police on Wednesday, the two perps waived extradition, and accompanied by the angry John Adams, Officer Stone of Potsdam arrived in Brunswick by train on Thursday to take Tyro and McGatrey to the Empire State. Meanwhile, Edwards found two suitcases belonging to the perps; inside were new suits, “about two dozen pair of men’s silk hose[,] and a number of fine handkerchiefs in their original wrappers.” Tyro and McGatrey were also clothing thieves!

Adams was driving when the repaired Ford rolled out of Brunswick on Sunday, October 30. Officer Stone handcuffed together the adjoining hands of Tyro and McGatrey and then handcuffed their outboard hands “to the sides of the automobile.”

The quartet stopped that night in St. Johnsbury, Vermont (the local police tossed the perps in the local jail) and paused briefly in Topsham, Vermont

on Monday to return McLain’s stolen license plates. Then Adams and Stone delivered Tyro and McGatrey into the

Football Coach Fred V. Ostergren was unsure as to how much gridiron talent Bowdoin College would field for the 1921 season, but he got his answer soon enough: a lot of talent. Ostergren and Captain Al Morrell announced in early September that practice would start at Whittier Field in Brunswick on Monday, September 12. Qualifying players would run through their exercises and drills each morning and afternoon for the next two weeks.

Ostergren wanted his players in tiptop shape for their seven-game schedule. Bowdoin’s “varsity eleven” (as the local press dubbed the squad) would open their season with an at-home practice game on Saturday, September 24 against the Army team from Fort

Williams in Cape Elizabeth. The popular annual matchup with Bates had dropped off the schedule, leaving October 29 open.

Tryouts started a day late on Tuesday, September 13, and Ostergren reported that around 40 candidates showed up, including some veterans. Most candidates quickly suited up and got down to business.

Ostergren split the football candidates into Team A and Team B for the team’s first scrimmage played on Wednesday, September 21. “Both teams played well and the new men made an excellent showing,” a sportswriter noted. Playing across three 15-minute periods, Team A won, 17-0.

Bowdoin officially opened on Thursday, September 22, with a record 162 freshmen joining the upper classes returning for the college’s 120th year. Enrollment stood at 448 students. The day kicked off with a chapel service, during which Bowdoin President Kenneth Sills stressed financial responsibility and “the necessity of work.”

Fort Williams bowed out of the practice game, but Rhode Island State (cont. on page 20)

College arrived in Brunswick to open the regular season on Saturday, October 1. Some 800 fans watched the action seesaw back and forth, with Bowdoin stopping Rhode Island drives at the sixand 15-yard lines. The visitors jammed up Bowdoin at its one-yard line late in the second period.

Not until the fourth period did Bowdoin score on a carry from two yards out. A safety boosted the home team’s winning score to 9-0.

The next Saturday Bowdoin traveled to Williamstown, Massachusetts to play Williams College in a rain-soaked game that resulted in a 0-0 tie. Bowdoin running back Joe Smith ran 45 yards to the home team’s 15-yard line in the fourth period, but Williams stifled the Bowdoin offense. A field goal attempt from the Williams’ 30-yard line missed, and the home team could not capitalize on its own field-goal opportunities.

Bowdoin fans awaited news of three football games on Saturday, October 15. The varsity team went to Hartford, Connecticut to play Trinity College. Bowdoin defenders blitzed their opponents’ line to block a punt and regain possession on the Trinity 32-yard line less than six minutes into the first period. Bowdoin quickly scored, got the extra point, and took home a 7-0 victory.

Meanwhile, Bowdoin’s “second eleven” beat Thornton Academy, 7-0, at Saco, and Bowdoin’s freshman squad defeated Bangor High School, 7-0, at Bass Park. Butler, the right tackle for Bowdoin, “caught the kickoff and ran through the Bangor team, nearly the length of the field for a touchdown,” wrote an awed sportswriter.

That evening in Brunswick, “a jubilant crowd of freshmen … pulled the chapel bell in celebration of the triple

Colby came to Brunswick on October 22 for Bowdoin’s first Maine college-series game. “A very large crowd” turned out on an “afternoon just perfect for football,” except for the “strong cross wind.” The Bowdoin varsity took Colby apart, gaining 121 yards versus the visiting team’s 50 on the ground and 105 yards versus eight yards for Colby in the air. Bowdoin claimed an 18-6 win.

With October 29 a bye, Bowdoin geared up for the Saturday, November 5 “final game in the State championship series,” to be played at Orono against the University of Maine team. A few Bowdoin players nursed injuries from the Colby game, but overall the squad was “for the most part in excellent condition.”

Rain fell overnight November 4-5, the sun briefly shone Saturday morn-

ing, and then “a gale began to sweep over the field[,] bringing with it a snowstorm that froze the very blood,” a sportswriter said. Snow continued falling throughout the game, “and the field was a veritable marsh” as 4,600 fans jammed the bleachers.

The snowstorm “increased in fierceness,” and many fans left, “but the hardy players still fought on, with freezing hands and muddy bodies.” The wind essentially shut down the aerial attacks, and the teams scored on the ground. Small, a UM runner, broke around his team’s left end and slogged 67 yards through the muck to score. Bowdoin fullback Morrell “made a beautiful flying tackle” late in the run, but slipped and caught Small’s foot square in his face. That was Maine’s only touchdown, however, and Bowdoin scored twice to win the state championship, 14-7. After spending much of the sea-

son sidelined with a damaged tendon, Al Morrell came off the bench and “made several wonderful punts considering the weather.”

The ecstatic Bowdoin players hoisted Coach Ostergren to their shoulders

and paraded off the football field with many other Bowdoin students in tow. The Bowdoin College band played the familiar “Bowdoin Beats” as the visiting team celebrated Bowdoin’s first win against UMaine since 1918.

Like Benjamin Franklin, another titan of the age, William King was an industrious up-by-thebootstraps type of man of relentless energy who was able to amass immense fortune and power. Both were known also for their integrity and a lifelong habit of thrift and saving. Born in February 1768 to a prosperous Scarborough family that fell on hard times, King managed only the briefest education before setting out on the road. At just 21, this “stalwart lad in crude homespun” was already following the way toward the town of Bath and his destiny. Insight, perseverance, and a hard work ethic enabled his mastering the diverse

realms of business, politics, the military, and even to become the first governor of Maine.

First, he went about building his finances. Arriving threadbare in Topsham but ready for work, he started out learning the lumber trade. In no time he was owning a sawmill, a shipyard, and an entire fleet of merchant vessels. Next, he opened the state’s first cotton mill, the first bank in Bath, and possessed such extensive real estate holdings that from them emerged the eventual town of Kingfield. Soon he was one of the richest and most influential men in the province.

In today’s parlance King was a

workaholic; but he didn’t scrimp, and always enjoyed the finer things that life had to offer.

By 1804 he was already representing Bath in the State Legislature in Boston and later served in the State Senate. As a “Jeffersonian”, or Democratic-Republican, King displayed a positive genius for pursuing the nonpartisan approach, which burnished his honesty to epic proportions. Later this paid big political dividends. It was about at this time that his regal style also began to earn him the nickname as “the Sultan of Bath.”

One bill he sponsored helped put an end to unscrupulous early land practices. Wilderness setters might suddenly find themselves dispossessed, evicted, and forfeiting all that they owned if an earlier claim could be established. This new bill provided they at least be adequately compensated. Fairness like this went a long way at election time.

With the War of 1812 King was appointed a major general in charge of raising militia and coastal defenses. It also allowed him to keep an eye on his empire. For unstinting effort, he was made a colonel in the regular United States Army. In 1813 he began his valiant seven-year campaign to separate the province of Maine from Massachusetts, largely due to frustration with the Commonwealth’s failures during the war. And he proved just the man for the job: well-known, well-to-do, and well-connected, he was at the height of his popular powers. A coalition gradually formed to push for independence and the 1819 referendum that passed in a landslide. A year later, as part of the Missouri Compromise, Maine became the Union’s 23rd state, and King was elected its very first governor.

Of all his amazing accomplishments this is the one that defined him the most.

Tall, stentorian, edgy, and pushy —

common traits in this age of Napoleon — King had the ability to dominate just about any room that he entered. Still, he served barely a year before being called away to assume a commission in Washington.

A natural leader, King could be caustic, too, bringing his famously pointed wit to bear against his fellow politicos. And he was prone to winning debates by shouting down his opponents. A bit of a cranky iconoclast, he liked to recount that his relationship with the church usually made him come out smelling “about like a skunk.” This dour demeanor did not extend to the alcohol served plentifully at his table despite a strong popular sentiment against it. Too liberal by half in his views for most of his peers, even his card parties could become a source of contention. Said to be uncommonly fond of the game, the Sultan would slap his hand down thunderously on the table, while (cont. on page 26)

somehow always remaining the perfect host. Of a type immediately loved or hated, most contemporary accounts of him describe a man truly deserving of all his accolades.

Gracious, genteel, but ever striving, King married according to his station and wed Ann Frazier, the belle of Boston society. He reportedly cut a dashing figure resplendent in a military coat of vivid scarlet lining as he escorted his rustling bride down the aisle. Summering at Stonehouse Farm amid acres of rolling pastures and ripening orchards set atop Whiskeag Hill, in that mansion of polished granite Governor King and his lady would entertain as royally as in the olden times of yore. From its lofty cupola the Sultan could overlook and admire his entire domain while his ships lay gently abob on the Kennebec River. That site is now on the list of the National Register of Historic Places.

Remaining a pillar of strength, the

aged King kept to a busy schedule. Freemason, trustee of Bowdoin College (despite the limited education) and by appointment the Customs Collector of Bath, all lay before him. Later still he ran again for governor but lost. As the end approached, that brilliant mind gradually dimmed, and he fell a victim to ill health and a woeful string of domestic troubles.

An 1852 statue of King depicts an imposing figure dressed proudly in Western boots but draped in a Roman toga. He died at home, in Bath, in July of that year, at the age of 85 and lies buried in Maple Grove Cemetery.

by James Nalley

by James Nalley

In 1860, at the 36th U.S. Congress in Washington, D.C., Illinois Congressman, and abolitionist Owen Lovejoy made several remarks in regard to the 1837 murder of his brother Elijah Lovejoy. After Wisconsin Congressman John Fox Potter made follow-up remarks, Virginia Congressman Roger Pryor edited Potter’s official remarks and eliminated any mention of the Republican Party. After Potter outrightly objected, Pryor challenged Potter to a gentleman’s duel. According to the article “The Pryor-Potter Duel” (1944) by William Hesseltine, Potter selected a Bowie knife as the prospective weapon, causing the duel to be cancelled and his choice of weapon to be referred to

as “vulgar, barbarous, and inhuman.” Over time, he had earned the nickname “Bowie Knife Potter.”

John Fox Potter was born in Augusta (then Massachusetts), on May 11, 1817. He attended local public schools, but completed high school at Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire. After his marriage to Frances Elizabeth Lewis from Portland the couple (along with her father and unmarried sisters) moved to a farm in Wisconsin.

After he was admitted to the Wisconsin bar in 1837, Potter began his legal practice in East Troy. He eventually served a judge in Walworth County from 1842 to 1846. Over the next de-

cade, he became increasingly involved in politics as a Whig. In 1856, he was elected as a member of the Wisconsin State Assembly, and he served as a delegate at the Whig National Convention in the same year. After the Whig Party failed to develop an effective campaign platform and was dissolved later that year, Potter became a Republican. Wisconsin voters then elected Potter to the U.S. House of Representatives, after which he won re-election twice.

It should be noted that this was a particularly turbulent time in Congressional history. According to the Wisconsin Historical Society (WHS), “Conflicting ideologies, customs, and personalities threatened to tear Congress apart. The issues of slavery and states’ rights deeply divided the nation’s lawmakers, and debate and compromise routinely yielded to verbal confrontations, personal humiliations, and physical assaults.” In this hostile

environment, Congressman Lovejoy from Illinois gave a fiery anti-slavery speech (with mention of the murder of his brother), after which Congressman Pryor from Virginia objected to the former’s demeanor. Then, in Lovejoy’s defense, John Potter argued that he was fully allowed to express himself. Several days later, Pryor and Potter bickered with one another about the official record of the incident, which the former had edited.

As stated by the WHS, on April 8, 1860, “Believing that Potter offended his honor, Pryor challenged him to a duel, after which Potter accepted the fight and chose a Bowie knife.” After Pryor stated that his selection of weapon was “vulgar, barbarous, and inhuman,” Potter replied, “The custom of dueling itself is barbarous and inhuman.” Eventually, “the District of Columbia police arrested both men to keep the peace. The duel never occurred.”

Naturally, the print media sensationalized the event, with Northern newspapers condemning the duel as a vulgar Southern practice. Meanwhile, Potter’s Democratic opponents in Wisconsin demanded his resignation and accused him of political grandstanding. As for the Republicans, they made Potter a hero, after which supporters from across the country sent him knives of every size in honor of his newly acquired nickname.

From May 16 to 18, 1860, the Republican Party held its National Convention in Chicago, Illinois, where it nominated Abraham Lincoln for President. According to the WHS, “At the convention, delegates from the slave state of Missouri presented Potter with a 31-pound, 6-foot-long folding knife to commemorate his ‘victory’ over Pryor. It was the highlight of the convention and it earned national press exposure when it was dubbed the ‘monster (cont. on page 30)

(cont. from page 29)

Bowie knife.’”

Eventually, and ironically, Potter was considered one of the “Radical Republicans,” due to his support for African American civil rights and his belief that slavery should eventually be banned. In February 1861, Potter was one of 131 American politicians at the Peace Conference of 1861. The purpose was to avoid the secession of the eight slave states, which had not done so as of that date. Their meeting failed and it paved the way for the U.S. Civil War in April of that year.

Much like today, when a politician is somewhat controversial, a challenger appears. In 1862, Potter was challenged and defeated in his race for re-election by fellow Maine-born lawyer and Democrat James Brown. When he left office in January 1863, he declined an appointment as Governor of the Dakota Territory (the northernmost part of

the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase). Later that year, the Lincoln administration appointed Potter as Consul General of the United States in the British-controlled Province of Canada from 1863 to 1866. At that time, Potter resided in the city of Montreal.

In 1866, Potter returned to East Troy, Wisconsin, where he resumed his legal practice. On May 18, 1899, Potter died at his home. He was 82 years of age. As for his legacy, Potter kept the oversized knife in his home until too many visitors started to annoy him. He eventually donated the knife to Lawrence College in Appleton, after which the college donated it to the WHS in 1957. Interestingly, on one side of the knife, the engraving reads “Presented to John F. Potter of Wisconsin by the Republicans of Missouri 1860.” However, the other side of the knife reads, “Will always meet a Pryor engagement.”

by Sarah Meredith

by Sarah Meredith

On the tip of Southport Island, away from the hustle and bustle of nearby Boothbay Harbor, the Newagen Seaside Inn has been preserved as an elegant reminder of a bygone era. There are no telephones or televisions in the rooms and the unspoiled beauty of this seaside world inspired one of the natural world’s greatest champions, Rachel Carson. The noted marine biologist completed much of her research and writing for The Edge of the Sea and later for her internationally acclaimed Silent Spring at Newagen.

Born in 1907 in Pennsylvania, Rachel Carson developed her deep love for nature as a child, exploring the woods at her mother’s side. After studying

marine biology, Rachel graduated from college in 1929 and then continued her studies of ocean life at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts and received her masters in zoology from Johns Hopkins University in 1932.

Rachel began her career as a naturalist writing radio programs for the Department of Fisheries during the Great Depression. Her talent for communicating science to the public led to her work as Editor-in-Chief of all publications for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Conservation, natural resources and natural history were topics explored in Rachel’s scientific research.

She also began writing prose, which

was well received by the public. The Sea Around Us won the National Book award in 1952 and was on the non-fiction best-seller list for thirty-nine weeks. After a fifteen-year career with the Fish and Wildlife department, Rachel decided to pursue writing fulltime in 1952. Publishing articles such as Help Your Child to Wonder and Our Ever-Changing Shore, Rachel shared her love of the ocean with a wide audience.

During the 1950s and 1960s Rachel spent many weeks vacationing and studying in the quiet of Newagen. A story is told that Rachel once spent such a long time wading in the chilly tidal pools of Newagen’s coast that she

(cont. on page 34)

(cont. from page 33)

needed to be carried back to the inn. Warming herself by the fire and writing The Edge of The Sea, Rachel created a portrait of Newagen that draws guests from all over the world.

I can’t think of a more exciting place to be than down in the low tide world, when the ebb tide falls very early in the morning, and the world is full of salt smell, and the sound of water, and the softness of fog. Rachel Carson, The Edge of the Sea

With the publication of Silent Spring in 1962, Rachel drew some criticism as an alarmist for her criticism of pesticide use. Today she is recognized as one of the most influential scientists of the twentieth century (Time, 1999) for her groundbreaking study of the negative effects of pesticides on the environment. She spoke out often to remind the public that we are all a part of the ecosystem and will be affected by pollutants along with the natural world.

Shortly before her untimely death in 1964, Carson spent her last visit to Maine at the inn. The tall foliage, the migration of the monarch butterflies and the fading of the wildflower gardens spoke to Rachel as a reminder of life’s eternal cycles.

September 10, 1963

Dear One, This is a postscript to our morning at Newagen, something I think I can write better than say. For me, it was one of the loveliest of the summer’s hours, and all the details will remain in my memory: that blue September sky, the sounds of wind in the spruces and surf on the rocks, the gulls busy with their foraging, alighting with deliberate grace, the distant views of Griffiths Head and Todd Point, today so clearly etched, though once half seen in swirling fog. But most of all I shall remember the Monarchs, that unhurried westward drift of one small winged form after another, each drawn by some

invisible force. We talked a little about their migration, their life history. Did they return? We thought not; for most, at least, this was the closing journey of their lives. But it occurred to me this afternoon, remembering, that it had been a happy spectacle, that we had felt no sadness when we spoke of the fact that there would be no return. And rightly — for when any living thing has come to the end of its life cycle we accept that end as natural. For the Monarch, that cycle is measured in a known span of months. For ourselves, the measure is something else, the span of which we cannot know. But the thought is the same: when that intangible cycle has run its course it is a natural and not unhappy thing that a life comes to its end. That is what those brightly fluttering bits of life taught me this morning. I found a deep happiness in it — so, I hope, may you. Thank you for this morning.

This letter was written by Rachel Carson on her last full day in Maine to her dear friend, Dorothy Freeman. That morning the two of them sat on the west lawn of the Newagen Inn as Rachel’s declining health forced her to consider her own mortality. After a battle with cancer, Rachel passed away the following spring. She chose Newagen as her final resting place. Her ashes were scattered to the winds and sea and a plaque was erected in her honor on our western shore.

Today’s inn guests can be enthralled by the same tidal pools, savor the sounds and the smells of the sea and the softness of fog, and explore a milelong seaside trail. Innkeepers continue the careful stewardship of this precious natural wonder and the tradition of hospitality that welcomed Rachel

so many years ago.

There is no doubt about it, Boothbay Harbor is one of the most beautiful towns on the coast of Maine. This is one of the reasons why it attracts so many summer visitors who return year after year to wander its delightful streets exploring unique boutiques, sampling the fine food of its restaurants, or taking a cruise on one of the many vessels that call Boothbay Harbor their home port.

Boothbay Harbor is more than a simple tourist attraction, though. The stately Victorian homes speak to a bygone era when ship captains walked the town’s streets. The footbridge across the harbor gives glimpses of offshore

islands where summer colonies bask in the sun much the way they did a century and more ago.

If there is a single thread running through Boothbay Harbor’s history it is the sea. The peninsula on which it sits — smack in the middle of the most jagged and broken shoreline in the world — could almost pass for an island. For this reason, the residents of the town have always looked to the vast blue stretches of the Atlantic rather than inland. In fact, when there was some desultory discussion of the Knox and Lincoln Railway running a spur to the Boothbay waterfront in the 1870s, there was no interest in town. The sea

was the townspeople’s highway and railroad, and nothing illustrates this more than the vessels which have been associated with the area since its earliest days. They are vessels bearing names like Little Squirrel, Little James, Bowdoin, Sunbeam, Argo, and Balmy Days. And, they and others like them all add their bit to the storied communities and islands of the Boothbay region.

Today Boothbay Harbor is home to all sorts of pleasure craft, lobster and fishing boats, and cruise ships. Long before these vessels appeared in Linekin and Sheepscot bays, however, the ships of captains like John Smith, Bartholomew Gosnold, George Wey-

mouth, and Samuel Champlain cruised off Boothbay. The explorers were followed by Basque, Breton, Portuguese, and English fishermen. Then came the fur traders.

Probably the first shipwreck in the Boothbay region was that of Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s Little Squirrel. The Little Squirrel was a fur trader that sank in a storm in Boothbay Harbor in 1583. Tradition has it that Squirrel Island, the nearest land where the Little Squirrel floundered, is named for her. In the 1880s a group of Lewiston businessmen and college professors from Bates purchased the island for $2,200 for a secluded retreat. Today the Squirrel Island Corporation maintains that tradition of peaceful reclusiveness.

In 1624 the Little James suffered a fate similar to that of the Little Squirrel. The Little James was the first coastal trader and fishing boat owned by the Pilgrims of the Plymouth Colony. She

was wrecked off Cape Newagen. Unlike the Little Squirrel, the Little James was salvaged, however. Undoubtedly her repairs were a heavy financial burden for the struggling Pilgrim colony.

It would not be until the early nineteenth century that the first lighthouses would be built to warn mariners of the rocky coast and shoals of the Boothbay region. Altogether seven were constructed. These include Ram Island, The Cuckolds, and Burnt Island at the entrance to Boothbay Harbor and Hendricks Head off of Southport in Sheepscot Bay.

During the Revolution and the War of 1812, British warships caused more than a bit of trouble for Boothbay area fishermen and residents. The infamous Lieutenant Henry Mowatt appropriated some sheep and other victuals for his ships during a stopover at Boothbay when he was on his way to set fire to Portland (then Falmouth). Another

British landing party set fire to Benjamin Sawyer’s tavern on Ship’s island. Sawyer was able to repair the damage, however. Today the former tavern is thought to be Boothbay’s oldest house. The fact that Sawyer chose to have his tavern on an island speaks to how local residents regarded the water as a roadway. Today the island is known as Sawyer’s Island.

In the mid-1800s Boothbay and Southport rivaled Gloucester as Grand Banks fishing ports. By the turn of the twentieth century, however, the deepwater fisherman had been replaced by the lobsterman, and tourism had become the backbone of the area’s economy. Beautiful Spruce Point saw the construction of some sixty log cabins as well as famous Sprucewold Lodge, one of the largest log hotels in the country.

During the Great War Boothbay shipyards worked round the clock to build vessels for the American military. (cont. on page 38)

(cont. from page 37)

Here, too, one of the most famous vessels ever built in Maine, the Bowdoin of Arctic explorer Donald MacMillan, was constructed.

During World War II Captain Eliot Winslow, commander of the Coast Guard Cutter Argo, often anchored in Boothbay waters. In May of 1945 four German submarines surrendered to the Argo in Casco Bay. Captain Winslow went on to serve as first officer for Bath Iron Works naval vessel trial runs. Later he operated a cruise ship out of Boothbay Harbor. The ship was named the Argo after his Coast Guard cutter.

Today the Boothbay region continues its maritime traditions with more than forty cruise vessels. As for the town of Boothbay Harbor, it is definitely a walking town in the summer when cars fill its narrow winding streets that were laid out and built long before the automobile was even thought of, and the sea was the most important avenue of transportation.

Original Downeast fudge made daily using New England family recipes from a blend of imported cocoa beans plus fresh cream and butter. We are the connoiseur’s choice.

See operating antique turn-of-the-century Kiss Wrapping Machine. Watch the Harbor’s only candy-maker cook, pull, flavor, design and wrap Maine’s nicest-eating Saltwater Taffy. Our Peanut Butter Kisses are World’s Best!

Both located at 7 By-Way in Boothbay Harbor, Maine (Downeast Candies • P.O. Box 25 • Boothbay Harbor, ME 04538 • 207-633-5178)

“Casual Inside and Outside Dining on a Traditional Maine Fishing Wharf”

“Seafood at its Best”

Steaks & Chowders Too!

Featuring Single, Twin & Triple Lobster Specials and Select Your Own Larger Lobsters!

207-677-2200

Route 32, New Harbor • Maine shaws-wharf.com

Where shipyards once spread along Thomaston harbor, only the Dunn & Elliott sail loft stands today at 54 Water Street, on land bought by Thomas Dunn and George Elliott in 1873. According to Major Shipyards and Shipbuilders of Thomas, Maine, 1820-2020, Walter Dunn & Co. built the sail loft in 1874. Nearby stood the Stetson & Gerry Shipyard, which Thomas Dunn and George Elliott acquired in 1879. They would launch 56 ships at their renamed shipyard through 1920. From the sail loft came the sails made for the last barkentine built in Maine, a ship that suffered an ignominious fate.

Steel-hulled steamships had largely displaced wooden-hulled sailing ships by the early 20th century. The Dunn and Elliott fleet had shrunk significantly, but as the United States joined the Great War in 1917, the businessmen resumed building sailing ships.

The yard first turned out a four-masted schooner. Then in 1919 Arthur, Frank, and Richard Elliott built two barkentines: the 1,216-ton barkentine Cecil P. Stewart and the 1,087-ton Reine Marie Stewart, designed to carry coal. Each had four masts, with the foremast square-rigged and the three other masts fore-and-aft rigged. Dunn & Elliott launched the five-masted

1,512-ton schooner Edna Hoyt in 1920. That ship was the last of her kind built in Maine.

The sailing ships were workhorses, intended to haul freight until economic or hull conditions rendered a ship impracticable to operate. A ship’s value could decline precipitously with age; Dunn & Elliott spent $200,000 to build the Edna Hoyt, but got only $25,000 upon selling the schooner in 1924.

Coal-hauling gradually shifted to the railroads, which took business away from coastal shipping. The Reine Marie Stewart hauled coal until 1928; left moored in Portland, the barkentine was towed to Thomaston and tied at the

Dunn & Elliott wharf. There the ship slowly deteriorated until sold by Arthur Elliott in 1937.

The new owners rigged the Reine Marie Stewart as a schooner. After World War II began in September 1939, German U-boats started sinking freighters and tankers carrying cargo and petroleum to Britain. As ship losses outpaced new construction, the demand rose for intact hulls that could haul freight, and the Reine Marie Stewart was pressed into service in 1942.

She sailed under the flag and registry of Panama, a neutral nation. In spring 1942 New York City stevedores loaded the Reine Marie Stewart with fruitbox lumber. After filling the holds, the stevedores stacked lumber on the deck six-to-eight feet high and then covered the cargo with canvas. The unarmed schooner soon sailed with 11 crewmen and steered for the West African coast.

Meanwhile, the Italian submarine

Leonardo Da Vinci prowled the warm waters toward which the Reine Marie Stewart sailed. Launched in mid-September 1939, the 251-foot Marconi Class submarine displaced 1,465 tons and had eight torpedo tubes, four anti-aircraft guns, and a 100-millimeter deck gun, a large weapon.

Commanded since October 1941 by Capitano di Corvetta Luigi Longanesi Cattani, the Leonardo Da Vinci spent early 1942 seeking Allied shipping near the Brazil coast, where convoys headed to and from Cape Town and the Indian Ocean sometimes passed. Cattani sank the 3,557-ton Brazilian-flagged freighter SS Cadebelo (outbound from Philadelphia) on February 14 (there were no survivors) and the 3,644-ton Latvian-flagged SS Everasma on February 27. There were 15 survivors from that 25-year-old freighter.

Briefly returning to the German U-boat base at Bordeaux, France, Cat-

(cont. on page 42)

(cont. from page 41)

tani put to sea on May 11 and reached West African waters. Late on June 2 he spotted the Reine Marie Stewart some 40 miles southwest of Freetown, Liberia. Becalmed, the engine-less schooner did not display any lights and sailed alone.

Cattani shelled the ship with his deck gun, but after the schooner did not sink, he launched a torpedo that blew a hole in the wooden hull. The 11 crewmen took to a 16-foot wooden lifeboat powered by an inboard motor. As they steered toward the nearby African coast, they were picked up by the British-flagged SS Afghanistan, which docked at Cape Town in late June and put the sailors ashore. They later returned to the United States aboard the SS Monterey, a 1931-launched ocean liner converted to a troopship during the war.

Today the Reine Marie Stewart lives on in oil paintings by 20th-century art-

As for

by Brian Swartz

by Brian Swartz

When Copperheads threatened the riotous ruination of Rockport Village in August 1863, Rockland Unionists came spoiling for a fight. The ruckus was over the national draft, vehemently opposed by people sympathetic to the Confederacy or at least against the war. Many pro-Southerners lived in the loyal states, including Maine. Because they looked like their pro-Union neighbors, they were called “Copperheads,” after the forest-floor camouflaged poisonous snake.

Via congressional legislation, the Lincoln Administration had created two classes of draft-eligible men in

summer ’63. The first class included all men ages 20 to 35 and unmarried men older than 35 and younger than 45. These men could be drafted at any time. The second class included married men aged 36 and older. These guys would not be drafted until the first class was all called up.

Congress excluded men in particular jobs, such as governors, from being drafted, but required each loyal state to register all other men for the draft. Maine officials poked into every nook, cranny, and cove to find and enroll its draftees.

Then names were drawn in July, and every man picked became a draft-

ee, technically under military law. If a Mainer “skedaddled” (fled) or hid to avoid the draft, he technically became a deserter.

A draftee could hire a substitute to take his place. The price was initially negotiable; the draft law also let a man pay a $300 commutation fee to avoid being drafted, so $300 became the going rate for a substitute.

Copperheads in some Maine towns concocted a scheme to help men avoid being drafted. For example, in summer 1863 “the town of Camden … voted to give its drafted men $300 each, to be used as they saw fit, and town orders were prepared,” a local newspaper re-

ported. With $300, a Camden draftee could hire a substitute or pay the communication fee, all courtesy of Camden taxpayers.

In that era Camden and Rockport were one and the same, merged officially as “Camden.” Not until February 1891 did Rockport split from Camden. But “these [1863] orders the selectmen refused to sign, on the ground that they were illegal, which exasperated the ‘copperheads’ to such extent that it is reported … they had plotted to burn the buildings of the selectmen and other loyal citizens,” the newspaper noted.

“There were loud threats and anticipations of trouble” on Saturday, August 22 and Sunday, August 23.

The noise seemingly came loudest from Rockport Village. On Monday evening, August 24, “two citizens” of that place arrived in Rockland, found Mayor Wiggin, and claimed that Rockport Village “had been threatened with fire and riot by ‘copperheads’ and some

of the drafted men.”

Could “the government schooner now lying here” go to Rockport Harbor and protect the village? the men asked Wiggin.

He contacted the schooner’s skipper, a “Capt. Edwards,” who “immediately took on board a crew of about thirty volunteers and soon ran his vessel up to the port, with a fair wind” and while entering Rockport Harbor “fired a gun,” the newspaper reported. Edwards then “moored his schooner close to the village with her [the ship’s] guns shotted, lanterns burning, and muskets stacked in readiness for immediate use.

“The presence of this effectual persuasive to law and order doubtless had a strong ‘moral’ influence on the disaffected persons, as no riotous demonstration was attempted, nor has the public peace been disturbed since,” the newspaper editorialized.

The tale made for exciting reading and rippled through Camden and Rock-

land. In Rockport Village, “Messrs. Carleton, Norwood & Co.” owned ships and ran a two-story grist mill set about 100 feet from the Camden Harbor shore.

The company’s proprietors took issue with the story, however, and signed and sent “a communication” to the paper. The letter claimed “the statements which have been made about an apprehended riot in that [Rockport] village to be ‘false and slanderous.’”

The businessmen wrote that while “the two citizens” of Rockport Village “were sent” to Rockland for help on August 24, “‘there was not, nor had there been, the least appearance of a riot [original italics].’”Ninety percent of village “citizens … without regard to party, will sustain the assertion.”

But — and this was a big but — the businessmen acknowledged that the selectmen’s decision “produced a feeling of anger and hatred against them, and that ‘some of the conscripts or their rel(cont. on page 46)

(cont. from page 45)

atives may have made some wrong and unguarded expressions.’”

Both Democrats and Republicans voiced such opinions, Messrs. Carleton, Norwood claimed without providing evidence. The entire riot story “is false and absurd,” the businessmen stated. When the government schooner anchored offshore, “no ‘Knots of Copperheads’ [were] standing around the streets,” which “were as silent and deserted that night as usual.”

The ship, cannons, “‘battle-lanterns,’” and “‘glittering muskets’” was “lost on the ‘Copperheads,’ who were all ‘sleeping quietly in their beds,’” according to Messrs. Carleton, Norwood. The “loyal men in Rockport” were “foolish and absurd” in their “statements of the unsafety” of the village.

So, the August 24 show of force either did or did not quell riotous inclinations among certain Rockport Village residents, and peace reigned.

by Charles Francis

by Charles Francis

On December 20, 1848 an advertisement appeared in the Belfast Republican Journal announcing that the bark Suliote would sail from Belfast for San Francisco on January 30, 1849. The Suliote and Belfast deserve a note in the history books because the bark was the first vessel to take 49ers bitten by the “gold bug” around Cape Horn to the new El Dorado of the West. Intriguingly, Belfast may have another tie to the fabled year 1849, besides the fact that the first ship laden with 49ers sailed from there. According to Ronald Banks, dean of Maine historians, James Marshall, the foreman at Sutter’s Mill who made the first California gold discovery, had ties to

Belfast. Because of Marshall, Belfast became one of the first if not the first community in the east to learn of the potential California bonanza. For that reason, Belfast residents and residents of other nearby downeast towns had a bit of a jump over other easterners also bitten by the gold bug. It was a small jump, however. A day after the Suliote left Belfast, the Bonnie Adele was loading passengers in New York who were bound for the goldfields.

While Bangor provided the bulk of the Suliote’s passengers — twenty-four hailed from there — Belfast and other Waldo County and downeast towns were well represented on the ship’s passenger list. Benjamin Griffin, editor

of the Belfast Republican Journal, quit his position to head around the Horn. William Weeks, a Unity lawyer, did the same thing. In addition, there were passengers from towns like Brooks, Lincolnville, and Camden. One aspiring prospector who learned of the Suliote’s departure traveled from Boston to make the trip.

There were two major highlights in the pre-sailing days of that long-ago January. One involved the arrival of the 49ers from Bangor. They showed up in Belfast with their own band heralding their presence. The other involved lawyer William Weeks, who gave an inspiring talk of the wonders of the West in a local temperance hall.

While the Suliote was the first vessel to carry Mainers to the California gold fields, it would not be the last as 49ers who possessed a way with words like Benjamin Griffin and William Weeks would write home encouraging others to follow them. Hundreds, if not thousands, would do so. Some would take the long route around Cape Horn, and others would sail to the Isthmus of Panama, and then cross to the Pacific and take another ship up the coast. Some of the latter would contract yellow fever, while others would disappear never to be heard from again.

The Suliote, with her forty-six passengers, left Belfast Harbor on a bitterly cold day. Six months later, which was about the average length of time it took Maine vessels to reach northern California, the Suliote dropped anchor in San Francisco Bay. The Suliote was followed by a steady stream of vessels heading down the east coast of the

United States for Cape Horn or the Isthmus of Panama.

Sailing around Cape Horn could be a harrowing experience. Some ships went down. Crosby Fowler, caught up in the stories sent home by William Weeks, wrote home shortly before his death in the goldfields, and stated that even though they had fair sailing all the way, “it was a weary trip.” Fowler was just twenty when he left his Waldo County home and celebrated his twenty-first birthday crossing the Gulf Stream. Fowler’s friend and traveling companion, John Scribner, died on the trip and was buried at sea.

Walking across the Isthmus of Panama could be just as dangerous as rounding the Horn. For one thing, there were bandits who made a living preying on the unwary. While it was possible to hire armed guards to guide one during the crossing, it was necessary to have the wherewithal to pay them. One Uni-

ty man, Anaziah Trueworthy, who, with a large group of other Waldo County men had walked across the Isthmus, died of fever off Acapulco.

Upon arrival in California, the first 49ers encountered a host of new problems. Food was expensive — a single egg could go for as much as a dollar. Unscrupulous merchants also charged premium prices for equipment and clothing. Living conditions were unsanitary to say the least. There simply weren’t enough buildings to house the hordes that arrived almost weekly. There was no law to speak of in the mining camps. Mexican authorities were doing everything to stem the tides of “gringos” descending on their shores. Thievery and murder were the order of the day. Miners had to be on constant lookout lest their gold be stolen. And, too, there were gamblers and other drifters who were ready at a moment’s notice to fleece an unsuspecting (cont. on page 50)

(cont. from page 49)

miner out of everything he had worked for.

By 1852, however, conditions had taken a turn for the better. That year Jonathan Parkhurst wrote home to his family in Waldo County that, “The mode of living has greatly improved and the price of provisions greatly reduced.” He went on to describe the crop yield of the farms in glowing terms, especially those in and around Sacramento. He would eventually quit mining and become an owner of orchards.

Very few 49ers struck it rich. The real money was to be made in providing miners with goods and services. Curtis Mitchell of Unity was one of the few Waldo County men who actually made a fortune, be it a small one. Tradition has it that he came home with some $40,000. For the rest, it can be said that they represented a spirit of daring-do the likes of which has seldom been seen since.

The USS Minneapolis spent May and June of 1896 cruising the waters of the Baltic Sea. Her reason for being there was to represent the United States during the coronation ceremonies of Nicholas II, Czar of all the Russias.

The Minneapolis was a 7357-ton protected steel cruiser. She had a sister ship, the USS Columbia. Both were built in Philadelphia in 1894 and were state-of-the-art warships. The Minneapolis and the Columbia were constructed as commerce destroyers. They weren’t the only steel vessels built for the US Navy as the nineteenth century waned and the twentieth loomed on the horizon. Other steel warships built in

this general time period included three battleships, small, fast torpedo boats, and landing craft.

The construction of steel vessels for the US Navy in the later years of the nineteenth century marked America’s entry on the world scene as a legitimate naval power preparing to rival mighty Britain and other European maritime powers. The steel vessels would first show their might in the Spanish-American War, in the Caribbean and in the Philippines.

It was a Maine man who was largely responsible for the creation of America’s modern steel Navy. His name was Charles A. Boutelle. Boutelle was a Maine Congressman. Boutelle’s Con-

gressional bills created the steel Navy. Politicians in Washington listened to Charles Boutelle when he spoke on naval matters. He knew of what he argued for. He was a naval hero — the sort of hero of whom legends are made. Among other points of note in Boutelle’s life, the Confederate fleet defending Mobile Bay surrendered to him. The surrender was the conclusion of David Farragut’s famous attack on Mobile.

Charles Boutelle was one of the great Maine political figures of the late nineteenth century. He was a power in the state and in Washington. Though his name is largely forgotten today, there was a time when Boutelle was one of the most powerful and loved

figures in the state. In Maine, Charles Boutelle sat at the helm of one of the state’s most influential newspapers, the Bangor Whig and Courier. In Washington, Boutelle chaired the powerful House Naval Affairs Committee. More, Boutelle was a powerful orator. When he spoke he drew attention and was listened to. When he spoke in Congress on the US annexing Hawaii he swung votes on the issue. The same was true when he spoke in favor of particular candidates at the Republican National Convention.

That Charles Boutelle was drawn to things naval and maritime comes as no surprise given that his father, for whom he was named, was a shipmaster. The man many historians identify as the father of the modern US Navy was born in Damariscotta in 1839. And like many a Damariscotta-born youth, Boutelle went to sea at an early age, at fifteen.

Charles Boutelle was descended from two old Damariscotta River families. His mother Lucy was a Curtis. And like many born on the banks of the Damariscotta, Boutelle looked beyond his immediate surroundings to the wider world.

Some would find it surprising that Charles Boutelle was a highly articulate man, that he went on to become a newspaper editor, and that he left school at an early age to go to sea. He has, however, been described as a charismatic speaker and an eminently persuasive writer.

Boutelle’s highest level of formal education was a single year spent at North Yarmouth Academy. Young Charles went there because his parents had moved to Brunswick, and North Yarmouth was the best school in the area. Other than the one year spent at North Yarmouth, Boutelle was self-educated. It might even be proper to say

he was self-cultured. He read the classics, Cicero and Seneca. The great Romans were his models for public speaking and writing editorials.

Charles Boutelle had spent some eleven years at sea when Fort Sumter was fired on. When Lincoln issued his first call for volunteers for the Union Army and Navy, Boutelle answered. Because of his experience at sea he was made Acting Master of the gunboat John Paul Jones. The John Paul Jones, an old sidewheel wooden steam craft, was assigned blockade duty.

Boutelle must have proved his mettle as commander of the John Paul Jones for his next command was the more modern Sassacus. The Sassacus was another steam gunboat and it too was wooden. In May of 1864 the Sassacus engaged the Confederate ironclad Arbemarle. Boutelle rammed the Arbemarle. Then the Sassacus received a direct hit to the boiler. However,

(cont. from page 55)

Boutelle was commended for “gallant action” and promoted to lieutenant, the highest rank attainable for officers not of the regular Navy.

Union Navy duty provided Boutelle with the first insights that led to his fight for a steel Navy for America. He saw first-hand how armor-clad gunboats dominated older wooden craft.

Boutelle’s last wartime command was the Nyanza, another wooden steam vessel. It was while Boutelle was on her that he took part in Farragut’s attack on Mobile Bay. Following this action, Boutelle was placed in command of Union naval forces on Mississippi Sound. It was his last wartime service.

Following the war, Boutelle secured a position as captain of a steamer running between New York and Delaware. He also married. His wife was Elizabeth Hodson, daughter of prominent Maine attorney and Maine State Adjutant General John Hodson. The couple

had three daughters. In 1870, through the offices of his father-in-law, Boutelle was offered the editorship of the Bangor Whig and Courier. In 1874 Boutelle and a partner purchased the paper. It remained in his control until 1900.

Boutelle’s first run for Congress came in 1880. He lost to the incumbent by just under nine hundred votes. He ran in 1882 and won, continuing to be re-elected through 1901 when he resigned for reasons of health.

Charles Boutelle suffered what may have been a brain hemorrhage on December 21, 1899. He never recovered. Nevertheless, his friends and political allies submitted his name for re-election in 1900. The fact that he was elected for a last time with one of his largest margins of victory ever, speaks to the regard voters had for him.

Charles Boutelle died in May of 1901. Just prior to his passing he was promoted to the rank of Navy Captain,

Retired, by joint resolution of Congress. It is the rarest of honors for a volunteer naval officer.

At the time of his passing the New York Times wrote that Charles Boutelle “actively championed the policy that has resulted in the present perfection of steel armor plants, and encouraged the use of American designs and materials in the building of iron ships. He took a leading part in promoting the condition of naval preparedness with which the United States entered into the Spanish war, and to which the Nation is largely indebted for its speedy termination.” The words are a telling tribute to the man who was born on the banks of the Damariscotta River and went on to become an American hero and US Navy proponent.

44 North Architects..........................................................................31

ADA Fence Company, Inc. ................................................................12

Affordable Well Drilling Excavation & Forestry.................................13 American Awards Inc. ......................................................................29

Augusta Civic Center...........................................................................8

Bailey Island General Store...............................................................19

Balmy Day Cruises............................................................................34

Bath-Brunswick Regional Chamber of Commerce............................19

Bay Wrap..........................................................................................57

Bean Maine Lobster..........................................................................11

Belfast Area Chamber of Commerce................................................45

Bennett's Gems & Jewelry................................................................47

Birches Lakeside Campground..........................................................27

Bisson's Center Store..........................................................................6

Blaze Craft Beer & Wood Fired Flavors..............................................46

Bonnie's Place..................................................................................43

Boothbay Harbor Chamber of Commerce.........................................32

Bowen’s Tavern.................................................................................46

Brillant & Son’s Inc. Auto Repair & Restorations..................................6

Busted Knuckle Tires & Repair.........................................................55

C&J Chimney & Stove Service, LLC......................................................3

Cabot Mill Antiques..........................................................................17

Cahill Tire Inc. ..................................................................................24

Camden Harbor Cruises.....................................................................45

Camden Opera House.......................................................................43

Cameron's Lobster House.................................................................19

Cantrell Seafood...............................................................................16

Cayouette Flooring, Inc. ..................................................................55

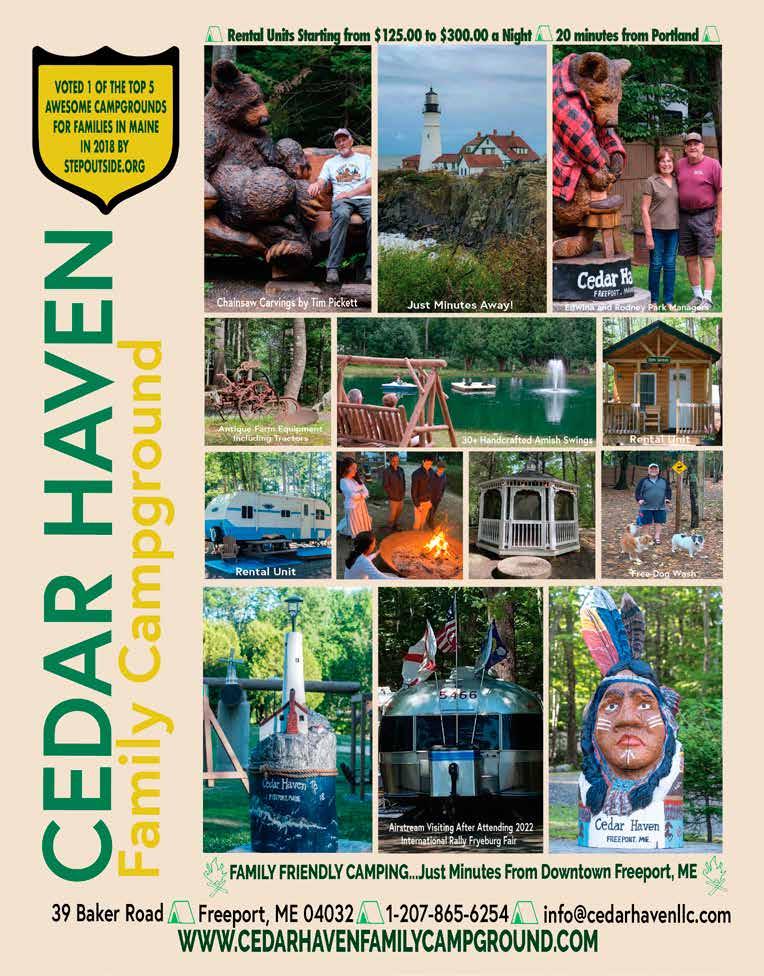

Cedar Haven Family Campground.........................................back cover Cedar Mountain Cupolas..................................................................13 Central Exterminating Services.........................................................46

Chase Farm Bakery............................................................................26

China By The Sea...............................................................................54

Clayton's Café & Bakery......................................................................4

Coastal Car Wash & Detail Center.....................................................33

Coastal Maintenance Painting..........................................................32

Coastal Motors..................................................................................33

Colburn Shoe Store...........................................................................48

Comfort Inn - Brunswick..................................................................21

Copeland's Garage............................................................................40

Cornelia C. Viek, CPA...........................................................................5

Cote's Transmission............................................................................7

Creamer & Sons Landwork, Inc. .....................................................24

Daffy Taffy Factory & Fudge Factory.................................................38

Damariscotta NAPA...........................................................................31

Dark Harbor Boat Yard......................................................................56

Design Architectural Heating...........................................................12

Dirigo Waste Oil................................................................................12

Donald E. Meklin & Sons..................................................................55

Downeast Ice Cream Factory............................................................35

Downtown Diner...............................................................................53

Dow's Eastern White Shingles & Shakes............................................3

Driscoll's Excavation & Tree Service..................................................20

El Rodeo Mexican Restaurant...........................................................17

Elmer's Barn & Antique Mall...............................................................7

Fairground Café................................................................................16

Five Islands Lobster Co. ...................................................................25

Five K First Class Landscape Arborist.................................................30

Flux Restaurant & Bar......................................................................16

Freeport Antiques and Heirlooms Showcase....................................11

Friends of Fort Knox..........................................................................51

G&G Cash Fuels................................................................................28

Genuine Automotive Services..........................................................42

Goggin's IGA.......................................................................................7

Goose River Golf Club........................................................................43

Granite Coast Orthodontics..............................................................45

Granite Hall Store.............................................................................39

Griffins - The Other Place...................................................................56

Grimaldi Concrete Floors & Countertops..........................................12

Gulf of Maine Books...........................................................................6

Haggett Hill Kennels........................................................................54

Haley Power Services........................................................................50

Paul Pinkham's Auto Repair...............................................................5

Pemaquid Craft Co-op......................................................................40

Pen-Bay Glass, Inc. ...........................................................................56

Penobscot Marine Museum..............................................................10

Perry's Nut House.............................................................................47

Pinkham's Gourmet Market..............................................................33

Plants Unlimited...............................................................................44

Quick Turn Auto Repair & Towing......................................................32

R.J. Energy Services, Inc. ..................................................................53

R.W. Glidden Auto Paint & Body Specialists......................................39

Rainwater Solutions.........................................................................58

Red's Automotive.............................................................................48