Chapter 1: Literature/contextual Review

1.3 Aims and Scope

My research aims to discover the strengths that come from, not just bringing the public into the gallery space, but including them. Due to this, within my studies, I was particularly interested in finding other works that research and document this collaboration within the curatorial and art world. Key sources I found vital to building my knowledge and practice include Simon (2010) and Riding (2022). Other related areas of research are subculture, participation, inclusivity, and engagement within art spaces. In terms of engagement and challenging the traditional notions of curatorial approaches, an analysis of the work of Harry Meadley demonstrates this. This study includes an interview (2022) with him.

1.2 Collaboration

Deborah Riding is an arts educator, curator and researcher focused on engaging audiences through relevant programmes and research. In her Tate paper, Curating Spaces for Not-Knowing (2022) says

‘Of particular interest to me in my research has been the understanding and value of the knowledge generated, developed and exchanged around artworks in these spaces.’ (Riding,2022)

2

This notion is that introducing more diverse voices in these spaces can lead to greater communication and interpretation of works. This idea is expressed, not just by Riding, but by several other writers on this subject.

Nina Simon’s The Participatory Museum (2010) tells us that a greater emphasis on participatory design within an institution can help to breathe life into decaying institutions. She calls for a new model that incorporates these ideas into the modern art space:

“It showcases the diverse creations and opinions of non-experts. People use the institution as meeting grounds for dialogue around the content presented. Instead of being “about” something or “for” someone, participatory institutions are created and managed “with” visitors.” (Simon, 2010)

Following my research into Riding and Simon, there are two main concepts I’m planning to incorporate into my work. This is co-creation and the democratisation of interpretation.

1.3 Gender and Sport

Due to the nature of my curatorial project, Through the Viewfinder, it seemed another relevant topic of research to include would be gender disparities within sports (with a direct focus on skateboarding). This is a highly relevant topic with an ever-growing achieve of knowledge. To aid with my research into this topic, I consulted the works of both Carr (2016) and Abulhawa (2008)

3

The first article I read was work by John Carr in his 2016 essay Skateboarding in Dude Space: The Roles of Space and Sport in Constructing Gender Amongst Adult Skateboarders. Which, Carr explores under what conditions could help those who are not cisgender males navigate and access male sporting spaces. He concludes that it is not work that can be passive in nature but is reliant on male skaters to reject this ‘persistent patriarchy that characterizes so much skate culture.’ (Carr, 2016, p.33)

Also, within this subject, I read Dani Abulhawa’s Female Skateboarding: Re-writing Gender (2008). In which, Abuluawa describes spaces that seem off-limit to specific social and cultural groups as ‘another world’. Going further to state that it is possible that the cultural importance of certain traditional sports is due to this female exclusion.

More specifically, it represents the difficulty which women face when participating in malegendered activities; for Massey it is not only the playing fields that seem barred but also the activity being undertaken. (p56)

My curatorial proposition within Through the Viewfinder is to help open an inclusive, albeit temporary, space. However, this project can be written about by participants and curators and have a wider reach across both the skateboarding and curatorial communities.

1.4 The Gazes

Another key theoretical idea that I found highly relevant to the research of my personal project was the notion of the male gaze in comparison to its female counterpart. The framework of my project is all about giving those who identify as female a space to create work in art spaces that are heavily male-dominated, lacking

4

the female gaze. To build on my research I investigated the published works of Laura Mulvey (1975)

One of the first texts I came across about this male gaze within skateboarding was ‘If You Hate @Skatemosss, What You Really Hate Is The Male Gaze’, a Skateism article by Tobias Coughlin-Bougue. In which Bougue discusses how the male gaze pushes female skateboarders that are conventionally attractive to the foreground, even if at times their counterparts who are ‘better’ skateboarders are pushed to the side

Their hearts are very much in the right place, a place of wanting to live in a society that celebrates women for their talents and contributions, not how badly men want to sleep with them

(Coughlin-Bogue, T. 2019)

The most significant text I researched about the gazes was Laura Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. As the inventor of the term ‘the male gaze’ it was paramount to include her in my research on the topic. In the chapter ‘Woman as Image, Man as Bearer of the Look’, Mulvey describes women’s main roles within film as that of being looked at and displayed.

‘The determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure’

(Mulvey, L, 1975)

5

However, whilst relevant to media, this theory can be applied to a whole host of other scenarios. In terms of skateboarding itself, Jess Melia (founder of community organisation Rolling with the Girls) summarises this clearly in an interview I carried out.

“Because of the male gaze women tend to be very weary of making themselves potentially look silly by failing over, which can also put you in a vulnerable position. This especially is made worse by being in such a male dominated environment.”

(Melia J, 2022)

2. History of Curation

Historically, environments of curatorial nature such as museums and galleries have been of a ‘white cube’ nature. This term was coined in 1976 by Brian O’Doherty, an artist and critic who titled one of his essays “Inside the White Cube”. Whilst this term was new the style of display had long dominated art spaces. This is just one of the ways in which the art world has gained this sense of being untouchable and uninviting to the public. In my curational work, I am to break away from the concept of the ‘white cube’ gallery, with my practice embodying accessibility and inclusivity.

6

(Fig 1)

‘When museums homogeneously present art as isolated in static, chronological, white rooms, it can dull visitors' reactions to the artwork, decrease their capacity to think about it contextually and alienate those with no previous knowledge (Birkett, W. 2012)

In its literal sense the Latin word “curator” means “to take care”. The role of the curator has always been the process of selecting, organizing, and presenting items in a meaningful way Adrian George describes this in an interesting way in The Curators Handbook ‘The language of curating is comparable to that of editing. The shared activities of selecting, assembling, arranging, and overseeing ideas…As editors of ideas, curators bring forward art and cultural practices to make the ideas available to

7

audiences not only through exhibitions, but publications, websites, forums, and other events.’ (George, A. 2015). This is true to the nature of curators as they need to constantly edit, push collaborators to explore their best work and know what to include and what to exclude from the final form.

An early example of curation as a practice can be traced back to ancient Egypt. Artefacts and sculptures of cultural significance would be collected by affluent members of society as a symbol of power and wealth. Furthermore, in ancient Greece, wealthy individuals would accumulate large collections of artworks. These formed the foundations for some of the world’s first museums. This practice evolved further during the Renaissance through the act of commissions. Members of wealthy backgrounds would commission artists to produce original works of art to display within private collections. In the modern age, curators are responsible for not only selecting and organising information but also making them accessible and meaningful to the public. They both preserve and interpret cultural heritage, as well as shape our understanding of the world around us.

However, the role of curators is constantly changing and has evolved to include a wide range of different fields, not just museums and galleries, but digital platforms too. An example of curating digital platforms would be Instagram. Its reach and longevity go beyond that of a traditional gallery space, bringing greater access to the masses. Furthermore, it also allows people to co-create and curate such spaces.

8

I intend to use a mixture of physical and digital mediums for my final exhibition (further detail available in section 6 about my project ‘Through the Viewfinder’.

‘Digital revolution, for instance, necessitates curators to engage a new type of audience who might experience the museum only virtually, and an increasingly multicultural society demands that curators acknowledge and drive new ways of understanding and presenting diverse art practices from across the world’ (Lee, S. 2018).

9

(Fig 2 & 3)

2.1 The changing role of the Curator

The role and responsibilities of the curator are ever-changing, and its broad definition is hard to encapsulate. What was once looking after collections and hanging exhibitions, now also includes collaborating and facilitating. The New Curator (2016) describes the profession as having six main components: Researcher, Commissioner, Keeper, Interpreter, Producer and Collaborator.

Once lofty and reserved for use in relation to people working in the arts, it has now become fashionable among bloggers, editors, stylists, disc jockeys, club promoters, marketers, baristas, thrift-store owners, and even mid-level corporate managers who are all rediscovering themselves as curators.

(Niemojewski, R. 2016)

A great example of this breaking away from the traditional mould of what being a curator can be is Artangel. An organisation created in 1985 that blurs the lines between both curation and production. One project, titled A Room for London (2012) depicts both collaboration and breaking away from a white cube space. The development of the room itself was done so through an architectural competition, in which both artists and architects were asked to design a space that could be both a hotel room and a creative studio. The winning design was inspired by the riverboat used by Joseph Conrad in 1890, written about in his work Heart of Darkness. This boat itself is perched on top of the Southbank Centre. Throughout the year 38 musicians, artists and writers were invited to stay in the installation to create new work. Including names such as Laurie Anderson, Jarvis Cocker, Teju Cole and David Bryne.

10

(Fig 4)

Furthermore, there was also a competition where the public was called upon to submit ‘ground-breaking ideas for the transformation of the capital’. The best twelve ideas won a night in the installation. Some of these winning ideas included ‘No Home to Waste’ by Katharine Hibbert which wanted to find a solution to the 40,000 empty homes within London. The suggested idea was to place volunteer workers in these empty homes as temporary property guardians. Another idea was ‘The Bird House’ which saw Amanda Lwin hoping to turn one of East London’s old railway terraces into a walk-in aviary.

This is a clear example of collaborative methods within the art sphere doing good for the public and those in need.

3. Types of collaboration within curation:

11

There are multiple forms of collaboration within the world of curation and these multiple forms can enhance the curatorial process by bringing together different perspectives and skills.

Another mode of collaboration within the curated space is curator-audience collaboration. This touches on methods such as co-curation and crowdsourcing under the wider bracket of curator-audience collaboration. This method is based on the idea that the audience is a key part of the curation process and thus should include them in the undertaking of the project

An example of such audience participation would be The Venice Vending Machine project. This project began in 2011 and is a moving live-art installation that asks the question of how society values art, created by Mariana Moreno. The title of vending machine might have you think of a monetary transaction, but rather than this, a conversation with the curator allows you to possess a randomly dispensed ball holding a small work of art. The works can be anything from paintings, drawings, sculpture, photography, memory stick containing videos and mini-installations

12

(Fig 5)

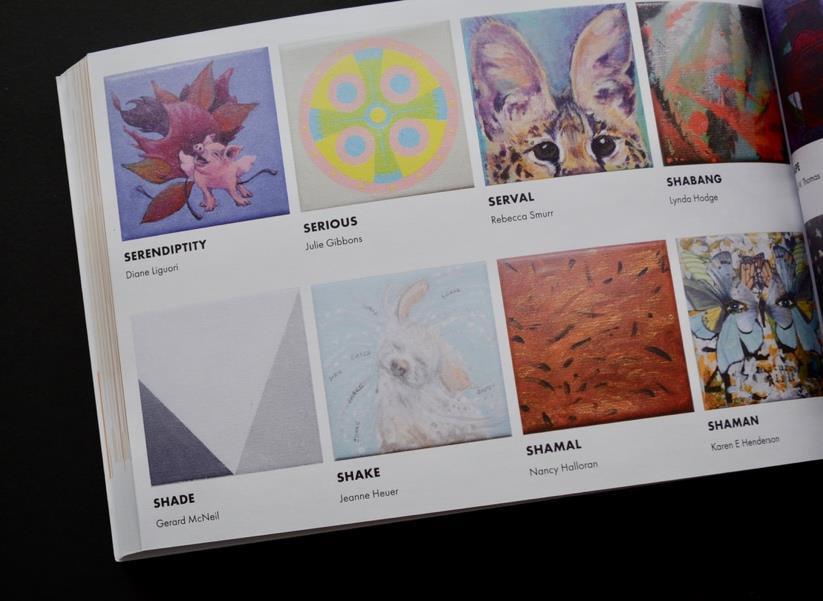

3.1 Crowdsourcing

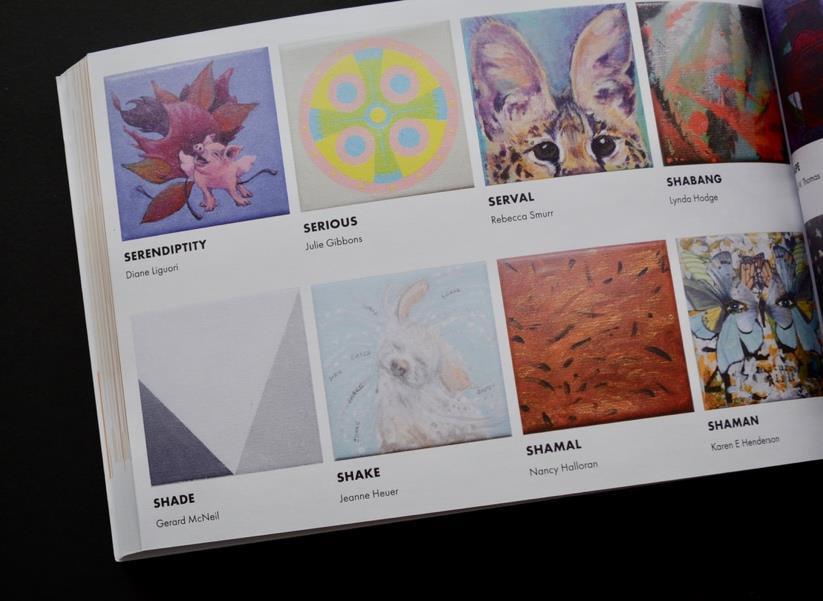

Crowdsourcing is a method of obtaining ideas and/or content from a large group of people, usually through virtual means. This has had heightened popularity in the past few years due to both its accessibility and the vast range of knowledge readily available. By harnessing this wide audience, curators can create collections and exhibitions that are more representative of the population through diverse perspectives. This could, in turn, lead to a more inclusive and collaborative cultural landscape within the art world. An example of such a practice would be ‘The Canvas Project’ by Brooklyn Art Library. Participants from all over the world were sent a 4x4 inch blank canvas alongside a prompt word. The words were sourced using their global community of artists to submit words. The returned canvases were featured in ‘A Visual Encyclopaedia: A Global Visual Interpretation of Words’.

13

(Fig 6)

3.2 Co-Curation

Co-curation is the form of collaboration that I am most interested in and use within my practice. This involves working with the audience to curate an exhibition and in doing so makes them active participants in the process and helps to create a more diverse exhibition. This can be through inviting community members and underrepresented groups, as well as artists and experts. This links to my own project as I am working with both members of the skateboarding community, particularly with the more underrepresented amongst them.

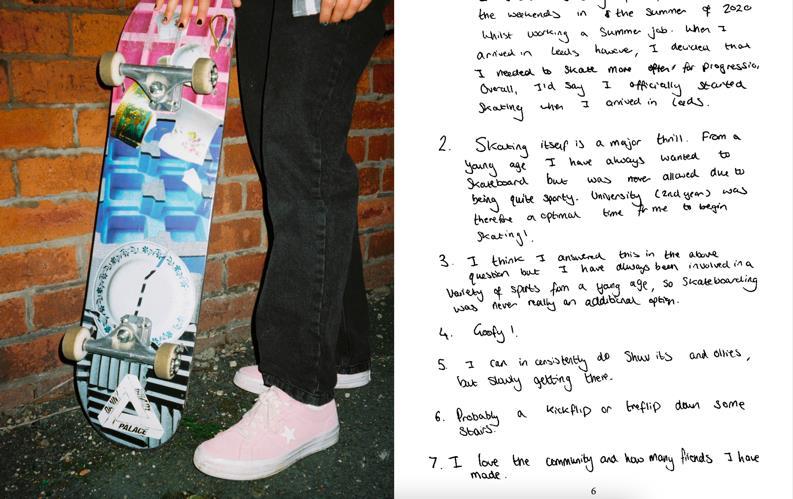

3.3 Collaboration within skateboarding

14

This collaboration can be seen outside of the gallery walls, as it plays a central role within the skateboarding community. Skateboarders recognize the value of working together, exchanging skills, and pushing boundaries. This can be seen within different areas of skateboarding such as capturing a video of a trick for another skateboarder, creating larger skate videos, taking part in doubles (two or more skateboarders doing a trick in the same video) or coordinating a skateboarding event. This collective energy within the community propels the advancement of tricks, styles, and the culture of what it is to be a skateboarder.

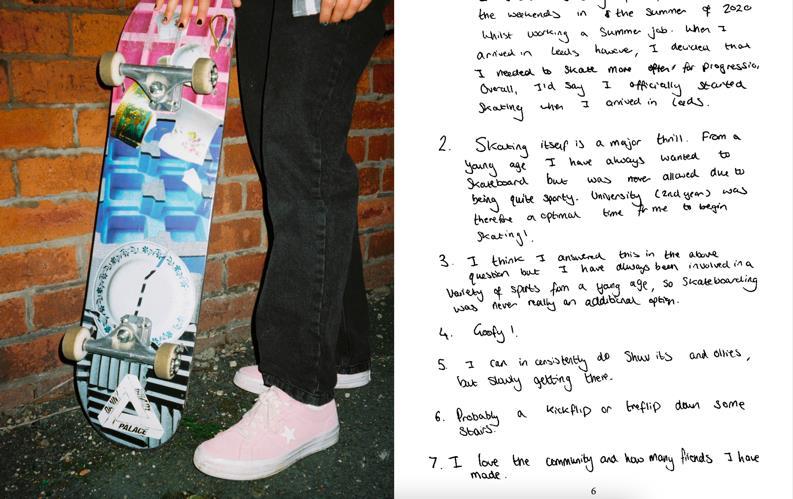

(Fig 7)

4. Nina Simon, ‘The Participatory Museum’

During my studies into collaborative practices in the art world, I came across Nina Simon’s work ‘The Participatory Museum’. This is one of the key texts that frame my study. This is stated by Simon herself to be a guide to working with members of the community, as well as visitors, to bring cultural institutions into the 21st century by

15

becoming ‘more dynamic, relevant, essential places.’ (Simon, N. 2010). In which, Simon describes a new form of curating. Traditionally curating is done noncollaboratively with institutions preferring ‘to experiment with participation behind closed doors.’ (2010). Simon, instead, believes that museums shouldn’t be visited spaces but those you actively participate with and connect with culture. This would benefit not only those participating but the art sphere itself. Only 19 per cent of the UK population attends an exhibition or collection of art, photography, or sculpture, according to the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. This vastly limits the different perspectives of art due to the limited amount of people engaging and doing so would allow us the opportunity to create a space that allows us to express our inner selves by exploring our unique emotions, experiences, and thoughts. Clearly more solutions to engage publics in curation practices needs to be done. There are some good practices out there, that need to become more widespread. This study is part of the solution to make the curated space itself more inclusive and polyvocal.

One thing I found distinct about this work was how, unlike many of the spaces she speaks about, her work is coherent to a wide range of audiences. Most of the time works like these are written in a way that caters only to those with the utmost understanding of in inner workings of such institutions. It’s refreshing to see an essay in which someone with no insider knowledge could read, and I think it’s a true insight into what she’s hoping will be achieved. Furthermore, she’s spoken about the key points within this essay via a TED TALK, again increasing and diversifying the audience. Alike Simon, my approach is also inclusive, and this study is part of the solution to a necessary set of changes, as evidenced through the recent initiative ‘Let’s Create’ by the Arts Council England. They hope to create ‘a country united by culture’.

16

Simon’s work stood out to me as it links so clearly to my own position as a curator. My curatorial approach as an artist-curator is feminist-based thinking that hopes to uplift and represent marginalised groups, giving them a space to share their experiences whilst simultaneously raising awareness and prompting action. I focus on underground, nonconformist subcultures to find the hidden stories that may be waiting to be discovered. My other values include interaction, collaboration and focusing on being outside the white cube. Both of our practices are situated in the progressive approach of co-curating with the public, in Simons's case, or minority groups such as female skaters in mine.

5. Harry Meadley

During my preparations and research for the forthcoming exhibition project, ‘Through the Viewfinder’, I contacted the local artist, curator and skater Harry Meadley. Meadley describes his approach to work as taking ‘a conversational and cooperative approach to art making, often working with galleries and arts organisations in the development of projects that address how art operates in a social context whilst seeking to challenge, transform and reclaim the intended uses of public space’ (Meadley, H. no date).

In a recent interview I organised with Harry Meadley he said the following about what he describes his more collaborative works as being done so to

‘To humanise the institution, to give the public "want they want” and see what that means, and to open up a wider conversation about public ownership.’

(Meadley, H. 2023)

This collaborative way of working can be seen through the solo exhibitions ‘But What if we tried?’ (2020) and ‘Free-for-All’ (2022) at Touchstones and his current work for Leeds 2023

17

under the title ‘My World My City My Neighbourhood’. Whilst any of these projects are relevant to the themes of collaboration and opening white cube spaces for the masses, Freefor-All is, in my opinion, the best example of doing so.

This collaborative nature in Meadleys work has become even more apparent due to closely working with him on his upcoming work for Leeds 2023 Year of Culture. In which, his idea is to host an exhibition of skateboarder’s art, from graphic design to paintings. Alongside practical skateboarding sessions and carrying out maintenance on some of Leeds best skate spots. He’s invited both Hilda Quick (photographer and skateboarding videographer) and I to curate a forthcoming exhibition for Leeds 2023 on the theme of skateboarding.

The forthcoming exhibition will be held at Black Space Gallery. The location itself is highly relevant to the skateboarding community, due to it being opposite a frequented skate spot: Playhouse Theatre. The theme of the exhibition is showcasing what a creative and artistic environment the skateboarding scene is. We aim to include art from local skate artists that work within a wide range of practices such as tattoo artistry, photography, fine art and graphic design. We will be creating an open call to have the best chance at showcasing a true representation of Leeds. We will be carrying out everything from the idea generation to the instillation.

5.1 Free-For-All

Free-For-All was an exhibition hosted by Touchstones from 23 July – 11 September 2022 and commissioned by Meadley. The tagline is a new type of exhibition where the gallery is

18

yours. Consisting of open mics, dog-friendly days, open exhibitions and using the gallery in other ways no one has yet thought of. The 7 weeks brought over 100 people bringing in their artwork and 50+ individual workshops. Due to the rebellious nature of the exhibition, it gained traction from the likes of BBC Front Row.

19

(Fig 8 & 9)

‘The one thing almost every gallery has is walls…’ (Meadley, 2022)

In the above images, you can see the style of display of some of Meadley’s work. Both images are very far removed from traditional styles of display. The above seems closer to a teenage bedroom covered in posters than the usual equidistance spaces between artworks within a white cube space. The second is a true visualisation of handing over the gallery space. Graffiti, like skateboarding, is not something often seen within the gallery walls.

The artists in this case were a free art group named ‘Creative Teens’, ran by Dani Burke and helping to give a voice to shy and anxious teenagers. There were no limits on what they could or couldn’t write or draw, although a lot of them seemed to focus on

20

environmental issues. On the topic of this installation of the wider exhibition, Meadly says: ‘Let people make their own contribution to the gallery, and this then generates a personal connection to the gallery. Just imagine if every young person had the opportunity to spray paint all over their local art gallery like this.’ (Meadley, 2022)

This interactive piece is reminiscent of 2019 exhibition ‘Yoko Ono at Leeds’. This was a selection of interactive installations from the artist including Wish Trees (1996/2019) and Skylanders (1968/2019). However, the one with comparisons to Meadley’s work was titled Add Color Painting (Refugee Boat).

(Fig 10)

This instillation creates an open invitation, extended to the audience, to take part. IUn the words of Mori Art Museum ‘It forms a metaphor for the idea that every moment in our ever-changing livres is beautiful.’ By doing so, Ono creates spaces for voices that

21

aren’t just her own. There's also something that seems to awaken the child within us; being handed a paintbrush and a blank wall.

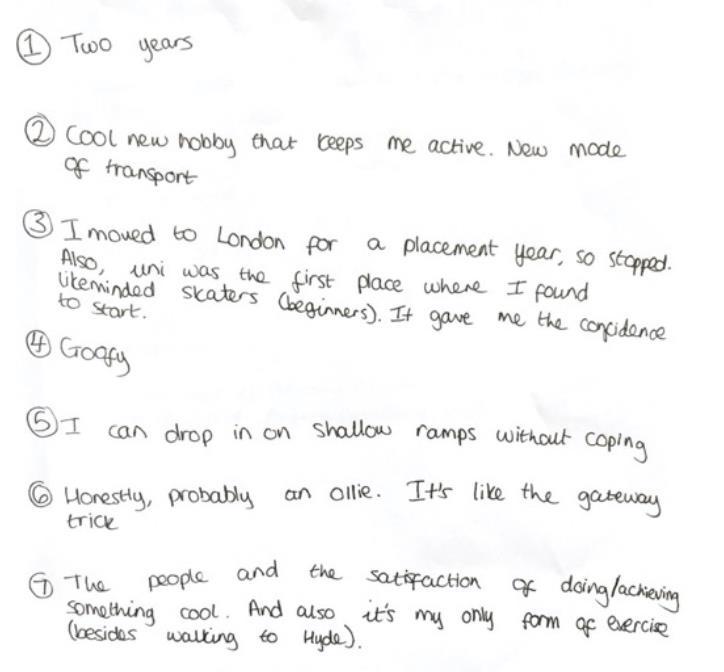

6. Through the Viewfinder

Another instance of inclusive practice is the forthcoming project, ‘Through the viewfinder’ (2023) which is planned in parallel to this study and is informed by it. This project sees me handing over the role of the curator and photographer to members of the skateboarding scene who identify as a marginalised gender, in the hopes of seeing individuals partake in art who may not have done otherwise. There is no direction on what they should document other than to try and capture the skateboarding scene as they see fit and a short briefing on how to properly utilise the camera. I’m carrying out photo-taking sessions with small groups of people to make the work that will eventually be exhibited. Something I hadn’t anticipated was how difficult it would be to completely hand over aspects that I usually have full control over and find myself having to hold back on suggestions.

Whilst the project will be physical in terms of it being displayed in an exhibition, I intend to preserve it through a digital medium such as Instagram or its own stand-alone website. As well as creating a wider reach of those who will see the works, it also helps with accessibility for those who may want to see it but have underlying issues that mean they cannot.

The work itself makes observations about the historically exclusively male-dominated culture and how this negative history is slowly being taken apart. My personal interest in this project has stemmed from my own experiences of being a beginner in this environment as well as the conversations I have had with other like-minded beginners and the intimidation they initially feel entering.

22

During my involvement in the Leeds skateboarding community for the past two years, I have engaged in various projects centred around it. In interviews, a common topic that arises when discussing why women may have been deterred from learning skateboarding is the lack of representation of fellow female skaters. Chloe Southworth, a beginner female skater, emphasized how discovering like-minded individuals at university gave her the confidence to begin her skateboarding journey. This challenge can be attributed to the mindset that separates girls and boys in physical education, promoting gendered sports. This notion conveys to young girls that if they have an interest in activities like football or skateboarding, they should instead participate in sports traditionally associated with females, such as dance or netball. This ingrained sexism may unconsciously influence these women as they grow up, making them feel like they don't belong in the skatepark. This can be backed up by Iain Borden (2001) in his critical study of ‘Skateboarding, Space and the City’. In which he states, ‘external factors may also lead to young women not taking up skateboarding, as for sport in general’. Furthermore, by Penney (2003) in ‘Gender and Physical Education: Contemporary Issues and Future Directions’. In which its stated that this separation of genders is:

‘likely to reinforce stereotypical images, attitudes and behaviours relating, amongst other things, to how they should feel about their own and other’s bodies, who can legitimately participate in what physical activities, when and why.’

23

(Fig 4)

In terms of participators in the project and their feedback on being involved, Eleanor Woods (A member of the second photo-making session) said

‘For me, participating in your project made me want to showcase the joy that skateboarding brings me; whether that was an action shot or a candid one, it didn’t matter as much as capturing that feeling did. I feel boundless and secure all at once when I skate with my community, and I wanted to try and show that in the work I made. I already enjoy photography, so this was a chance for me to try shooting in a setting that is totally different from the ones I’m accustomed to,

24

and to appreciate a different side of skateboarding that I don’t often get the chance to experience.’

(Woods, E. 2023)

This quote shows just how important this style of collaboration is, particularly including those from a minority group.

A project with some similarities would be Being Inbetween by Carolyn Mandelsohn and Girl Power by New Focus. Mendelsohn’s work Being inbetween was a series of over 90 portraits of girls between the ages of ten and twelve. This project demonstrated an exploration of the ‘complex transition between childhood and young adulthood’ (C, Mandelsohn. 2021).

Alongside each photograph was a corresponding interview allowing each respective individual the chance to create a dialogue on ambitions, aspirations, hopes and fears.

(Fig 12)

25

Aside from the fact that the project itself offered a representation of a minority gender, as well as further diversity within such a group, there was another link between this project and my own- participation. The featured girls were both creative participants and collaborators. Mendelsohn allowed everyone to select their own clothing and choose their own stance for their portrait. This is very similar to my method of granting complete creative freedom to the people that partook in my project. Furthermore, I even found similarities in some of my older work on the topic of gender and skateboarding. Particularly in the layout within Rolling with the Girls Zine #1 and how I chose to display the photographs with a corresponding interview.

26

(Fig 13)

(Fig 14)

I opted for this opportunity to be for minority genders only given that historically skateboarding, specifically those who create skateboarding media (videography, photography etc), have been male dominated. Dani Abulhawa speaks about this in her essay Female Skateboarding: Re-writing Gender: concerned with the notion of female skateboarders occupying an “edgeland” position within the subculture and how, from these edgelands, female participants might rewrite their involvement through the performance of gender.

(Abulhawa, D. 2008. p57)

27

(Fig 15)

The 2001 documentary Dogtown and Z-Boys evidences this male domination of skateboarding culture and its visual documentation. Even though their female counterparts had been skating since skateboarding inception, such as Patti Mcgee and Peggi Oki, many of the original photographers of this subject are male. There’s a true lack of diversity when it comes to portraying the experiences and voices of anyone other than males.

28

The photograph may allude to masculinity, but both its gaze and subject remain female. Of the male gaze is thought to be toxic, the female gaze is corrective. It is a perfect, virtuous circle, and entirely natural.

(Tsjeng, Z. 2017)

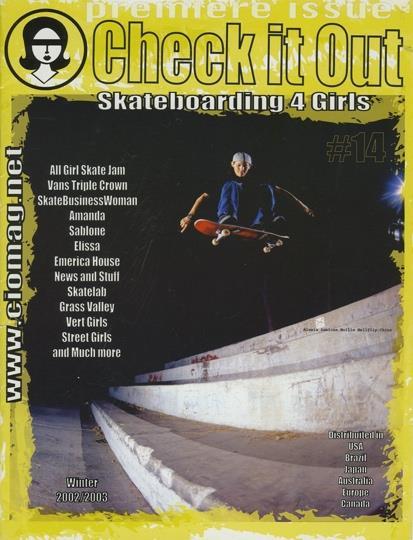

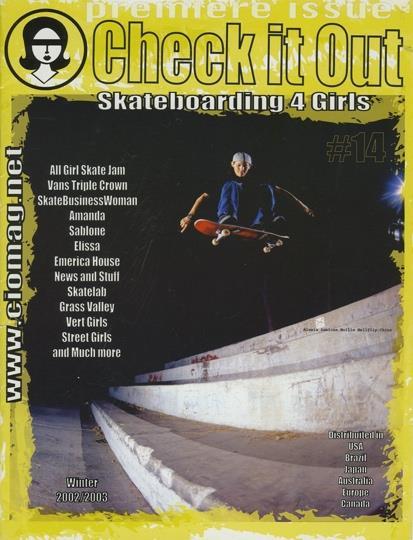

When typing ‘well-known skateboarding photographers’ into Google search the names that appear time and time again are Glen E. Friedman, Giovanni Reda and Ed Templeton. Back in the 80s and 90’s there weren’t as many female skateboarders and even fewer female skateboarding photographers. It wasn’t until the 1990s, 40 years after its origin, that Check It Out was formed. This was the world’s first female-led skateboarding magazine created by Brazilian photographers and skaters Liza Araujo and Luciana Ellington.

The importance of this type of representation cannot be overstated. Before having an entire issue of female representation they'd often be a ‘token female’. The ‘token’ is included within a larger group to make the audience believe inclusivity has been achieved when this is not the case.

Sometimes it seems companies get a token girl to tick a box

(Evans, 2021)

This publication has laid the groundwork for others such as Skateism, Skate Witches, and OH-SO! And Dolores Magazine.

29

Fig 9

7. Conclusion

Examples of curation and critical discussion have shown that collaboration within, and outside of, the art world is a powerful tool which can allow for the sharing of ideas, perspectives and techniques whilst also fostering a sense of community and support in an industry that at times can feel agnostic at times. This way of working is not only beneficial but necessary. When art institutions and artists use the tool of collaboration, the industry itself

30

becomes more inclusive and approachable to those not already in the field. The evidence suggests that this can welcome more individuals into the art world.

The aim of this dissertation is to inform a co-creative and inclusive curation practice. This has taken the form of making previously inaccessible environments such as skate spaces, skateboarding media, and art institutions more accessible. As well as doing the same for subjects and marginalised identities, these include females, those who identify as non-binary and trans people. This approach has been applied within my work ‘Through the Viewfinder’ by taking the media of skateboarding photography, an area where those other than cis men are less likely to be published in publications compared to their counterparts.

My practice, going forward, will be informed by my research within this study. In terms of the literature review, particularly the work of Laura Mulvey (1975) and Tobias CoughlinBogue (2019). These works taught me that the male gaze is wider than just cinema and other forms of art, but instead impacts on every area of visual communication and behaviours. This includes group and identity dynamics within skateboarding and the curated spaces

Furthermore, in the section on Harry Meadley’s ‘Free-for-All’ backed by Nina Simon (2010), I saw that his style of curation is the highest form of collaboration and participation. Rather than have one specific aspect of the project be collaborative or open to the public, he often hands over the role to them. This is a method of work I can see myself continuing to use in the future. It opens the door to more interesting exhibition work and a better chance at incorporating art into the life of the average person.

In terms of ‘Through the Viewfinder’, I thought several elements went well. For instance, the feedback from the participants was very positive. All of them stated that they enjoyed the

31

experience to be closer to the sport in a different way. However, an aspect that I didn’t anticipate being a struggle was having to step back as an image-based creative. Handing over your personal camera and not being able to give suggestions for composition or subject matter was an unexpected battle. This was most likely worsened due to my photography background. Another difficult factor was the fact that the medium used was 35mm film. Not being able to immediately see the works created made it harder to plan for the forthcoming exhibition and envision what such an exhibition could look like.

I hope to continue this project and continue to implement the collaborative form of curation and visual language of skateboarding culture. Whilst using the professional curatorial framework to inform future works. Early plans surrounding this continuation include but aren’t limited to, regular meetups with work being shared on an Instagram page or the work being released bi-annually through a series of zines. This will help this project become a sustainable practice and the continuity and longevity of the project could increase the presence of neglected identities, places and subject matters.

To conclude working collaboratively is defiantly more complex and time-consuming in the organisation stages, but this extra investment in the co-creative approach is worth it. This is due to the greater impact of the work produced, helping to create more inclusive projects which represent the underrepresented identities. All of these benefits help to showcase a more diverse proportion of the artwork being created in our modern society.

32

Bibliography:

Abulhawa, D. 2008. Female Skateboarding: Re-writing Gender. [ONLINE] Avaliable at:

https://www.royalholloway.ac.uk/media/5267/08_female_skateboarding_abulhawa.pd

f [Accessed 13/02/23]

33

Bäckström, Å., Nairn, K. (2018)

Skateboarding beyond the limits of gender?: Strategic interventions in Sweden Leisure Studies, 37(4): 24-439 https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2018.1462397

Birkett, W. 2012. To Infinity and Beyond: A Critique of the Aesthetic White Cube. [ONLINE] Available at:

https://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1211&context=theses [Accessed 25/02/23]

Bogue, T. (2019). If you Hate @Skatemosss, What You Really Hate is the Male Gaze’. Skateism, 8 April. [Accessed 10 January 2023] Avaliable at: https://www.skateism.com/skatemosss-male-gaze/

Carr, J. 2016. Skateboarding in Dude Space: The Roles of Space and Sport in Constructing Gender Among Adult Skateboarders. [Online] Avaliable at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307897381_Skateboarding_in_Dude_Space_ The_Roles_of_Space_and_Sport_in_Constructing_Gender_Among_Adult_Skateboarde rs Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. 2017. Taking Part focus on: Arts. [ONLINE] Available at:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment _data/file/740256/April_2018_Arts_Focus_report_revised.pdf. [Accessed 28/02/23]

34

Droitcour, B. N.d. Breaking away from the white cube. [ONLINE] Available at https://www.artbasel.com/news/breaking-away-from-the-white-cube?lang=en [Accessed 03/02/23

Evans, R. 2021, Issue 19 Interview, Vague Magazine, Guy Jones and Jono Coote. 22 December 2021.

Front Row BBC Sounds. 2022. 01 Aug. Avaliable at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m0019r0z

Jansen, C. (2019) Girl on girl art and photography in the age of the female gaze. London: Laurence King Publishing.

Krahmer, B. 2015. A History of Curating – Past and Present. [ONLINE] https://journals.openedition.org/critiquedart/19153?lang=en [Accessed 24/02/23]

Lee, S. -K 2018. The Changing Roles of Curators. [ONLINE] https://www.mplus.org.hk/en/magazine/sook-kyung-lee-on-the-changing-roles-ofcurators/ [Accessed 25/02/23]

Meadley, H. 2022. Free-for-all. [ONLINE] Available at: https://harrymeadley.studio/free-forall. [Accessed 1 March 2023].

Meadley, H.. 2022. Give galleries to the people. [ONLINE} Available at https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/magazine/article/give-galleries-people. [Accessed 28/02/23]

Milliard, C. et al. (2016) The new curator: (researcher), (commissioner), (keeper), (interpreter), (producer), (collaborator). London: Laurence King Publishing.

35

O’Doherty, B. 1986. Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space.

[ONLINE] Available at: https://arts.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/arc-oflife-

ODoherty_Brian_Inside_the_White_Cube_The_Ideology_of_the_Gallery_Space.pdf

[Accessed 25/02/23]

Share Museums East (n.d). Cocreating Community Projects. Avaliable at: https://www.sharemuseumseast.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Co-creating-

Community-Projects.pdf [Accessed: 03/02/23]

Your Trust Rochdale (2022). Free-For-All Artwork Open Call. Avaliable at: https://www.yourtrustrochdale.co.uk/free-for-all-artwork-open-call/ [accessed: 13/04/23]

Images:

Fig 1: An image of a white cube-style space in Bermondsey. [Online]. [Accessed 13 April 2023]. Available at:

https://tarastanleyfineart.wordpress.com/2015/11/12/introduction-to-curation/

36

Fig 2 & 3: Two images of the word ‘curation’ being used outside of the art world

Fig 4: An image of A Room for London [Online]. [Accessed 10 January 2023]

Avaliable at: https://davidkohn.co.uk/img/cXUrVE1rMEUvNkFLdW1FTGM1Q0NZQT09/dka-152room-web-01-hosea.jpg

Fig 5: An image of The Venice Vending Machine. [Online]. [Accessed 9 January 2023]

Available at: https://images.squarespacecdn.com/content/v1/5ab7ce2ce2ccd1996fea7dbb/1574591618658WFRGN5DQVHGBCFX0SMV6/IMG_20191122_1900214.jpg

Fig 6: Photograph of a page from the canvas project [Online]. [Accessed 10 December 2022]. Available at: https://www.gerardmcneil.com/home/the-canvas-project5076587

Fig 7: An image of a videographer filming a skateboarder. [Online]. [Accessed 5 June 2023] Available at: https://soloskatemag.com/upload/News/photo_clement_harpillard_romainbatard_filmin

g_lilian_fev_for_giddy_11_2020-12-14-143817.jpg

Fig 8 & 9: Images of Harry Meadley’s Free-For-All exhibition at Touchstones, Rochdale. [Online]. [Accessed 21 November 2022] Available from: https://harrymeadley.studio/free-for-all

37

Fig 10: An image of Yoko Ono at Leeds Exhibition. [Online]. [Accessed 5 June 2023]. Available at:

https://www.leeds-art.ac.uk/news-events/blog/yoko-ono-at-leeds/

Fig 11: An image from ‘Through the Viewfinder’ taken by Jess Melia.

Fig 12: Carolyn Mendelsohn. 2021. Being Inbetween. Photograph. [Accessed 13 April 2023] Available from: https://www.northerneyefestival.co.uk/being-inbetween

Fig 13: Spreadsheet from Rolling with the Girls issue 1 by Lauren Mudge

Fig 14: P Carolyn Mendelsohn. 2021. Photograph of Abigail from Being Inbetween. [Accessed 13 April 2023] Available from: https://hundredheroines.org/noticeboard/beinginbetween-carolyn-mendelsohn/

Fig 15: Phone image of Abby Smith photographing Liv Teasdale for ‘Through the Viewfinder’.

Fig 16: Image of Check It Out Magazine’s cover for issue 14. 2003. Photograph. [Accessed 19 April 2023] Available from: http://girlsskatenetwork.com/2003/01/15/check-it-out-magazine-issue-14-out-now/

38

Appendix A

Interview with Harry Meadley:

L: Can you describe your artistic background?

H: Having gone to art school (Leeds Foundation course) mainly off the back of my interest in making skate videos / websites with a mind to get better access to equipment and skills, I found that once I was there, and began being introduced to more conceptual artistic practices, the idea of art making and art in a more contemporary context really appealed to me. The course had an initial diagnostic stage, at the end of which you are put into a different subject pathway, even though I said I wanted to

39

Graphics, the tutor who was the head of graphics refused me and said I need to do Fine Art instead. I think often about this moment.

From there I developed through the rest of my art school experience what was a pretty solidly conceptual art practice which in an of itself was an interrogation of art making, exhibition making, art institutions, and the role of the artist. Over the following decade I produced hundreds of works which were each an attempt to take on a different type of artwork, thinking I could ‘do them all’, learn from the process, and see where that lead me. Even still, it stayed very much within a traditional gallery / exhibition context, was heavily object-based, and was still conforming to artworld norms. I hit a point where I decided to stop producing any object-based work, and would only make work by talking. This initially started with a series of anecdotal performances and conversationbased works but then lead onto the idea of initiating longer-term projects where I work conversationally with and within groups of people to realise larger institutional change.

L: My World, My City, My Skate spot is a fascinating project, particular in terms of participation and collaboration. How did this project come into fruition?

Other than one or two artworks, which maybe made slight references to skateboarding, I had always kept those two world separate. Over the years my practice transformed into becoming much more socially engaged and centred around barriers between art institutions and the communities who surround them. Though having worked with a few different communities, I had never worked with the one I myself am actually a part of. When Leeds2023 advertised their My World, My City, My Neighbourhood commission for a series of co-creation projects with communities in Leeds it sort of felt like a calling.

Quite unusually, I wrote what was actually quite a bolshy application where I basically said that if Leeds2023 didn’t include the city’s skateboard community it would be unjust given their tag line of “letting culture loose”. As a co-creation project it was necessary to have a project outline, so I just made an argument for why it would be important and significant for skateboarding to be included, why Leeds is lagging behind in relation to other cities who do engage with their skateboard community, and how, as a long-time Leeds skateboarder myself, this would be a project very close to my heart, and as an artist I have enough relevant experience.

Thankfully they accepted it (the Olympics being on at the time they were selecting may have helped too), and from there I had to figure out how and what the project would be. I started by basically talking to loads of people I know already who skate in Leeds, and where possible making efforts to to meet and talk with a those I didn’t. There was naturally a lot of ideas thrown up but what really stood out was how many female and non-binary skaters voiced a wish to want to street skate more, but that there were various barriers preventing them. It felt like aiming to do anything to do with street

40

skating in the city centre beyond that point would not be right before we addressed this issue first.

L: As a studying curator I am really interested in breaking away from the white cube. Can you tell me a bit more about your inspiration and how you went about your projects ‘But what if we tried’ and ‘Free-for-All’.

H: Initially I was invited by Touchstones (a municipal art gallery in Rochdale) to propose an idea for a project in response to their collection. Whereas other artists in the eventual programme did visits to the gallery store and went through the collection / archive, I took the approach to have conversations with the staff at the gallery and hear their thoughts about the collection. One thing that stood out was that it is a common complaint by visitors that not more of the collection is on show. In talking with the curator, and hearing the complexities of why it is difficult to show more of the collection - I just said “but what if we tried?”. From there the work / project developed into what was essentially a challenge for the gallery to attempt. I then acted more as an observer, and filmed a behind-the-scenes documentary of the process in the year or so leading up to the exhibition itself. The idea being that the work is as much about the display of the collection, as it is the display of the small team and social / political constraints they have to operate within. To humanise the institution, to give the public "want they want” and see what that means, and to open up a wider conversation about public ownership.

Though primarily an observer, I essentially became a member of staff / part of the team, and gained a wealth of first hand experience working with and within the gallery. From building a longer-time relationship with the gallery this has lead to the more recent project Free-for-All and is something I’m continuing to build upon for future projects with the gallery as well.

Whilst But what if we tried? was on, I was invited to do a residency at Jatiwangi Art Factory in Indonesia. It would be hard to fully talk through everything that’s amazing about JaF here but one thing that really stood out is that they operate an art space that is permanently open (literally they have no door) and are super integrated with the community they are within (their actual neighbours). In a way, Free-for-All, the idea of giving over the gallery for anyone to use / occupy how they want, is a combination of my experiences with But what if we tried? and Jatiwangi Art Factory.

L: How long have you been skating for, what made you begin?

H: I’ve been skating for 23 years now. When I was 11 I’d seriously injured my knee and had spent a year or so not being able to walk. I’d just got back to being able to walk a bit, and one of my older borther’s friends skated and as a 12 year who didn’t

41

easily fit into mainstream society I was pretty primed to be compelled by it. He started to show me a few basics and from there I was fully hooked.

L: Why do you think there’s such a high correlation of being a skater and being a creator?

H: Skating as a physical act in and of itself is a very enticing and addictive thing to do, but beyond that there is a “coolness” (for want of a better word) attached to skateboarding that adds to its appeal. The role of fashion, graphics, music. photography, video making, writing, and aesthetic appreciation (in terms of stylish bodily movement) are deeply entwined with it as a cultural practice. There is a culture to skateboarding which is as much a part of it as the act itself, and as a culture has often been an outsider / subversive / counter culture which maybe more naturally appeals / aligns with people who are equally drawn to creative practices.

L: In your opinion what can long-standing members of the skateboarding scene do to encourage and support women?

H: One of the main issues is that when you have a field that was been historically maledominated, when eventually women begin to claim some of that space for themselves, the majority of the older males, who most likely are quite happy with the presence of women / progressive change, don’t feel that it is their place “to get involved” in the spaces that (usually younger) women have had to carve for themselves. There is maybe a fear of feeling like you are forcing yourself (maleness) into those spaces, and that women should maintain their own agency, and a male presence may be problematic. That is certainly something to be conscious of, but equally, not feeling like you have a role, or are able to help / support women in and of itself perpetuates a division. One thing to become aware of is also how choosing to distance yourself (maybe out of politeness) from the female / n-b skate community continues to keep things unbalanced and is still exclusionary.

I feel the work done by so many female and n-b skaters to make skateboarding more inclusive, creative, and positive is something I have also massively benefited from - it makes me love skateboarding even more. We should be appreciative of this and seek to think how we can help them back - which isn't necessarily about there being one thing every male skater can do, but at the very least they should start conversations, ask how they can help, and go from there.

Appendix B:

42

43