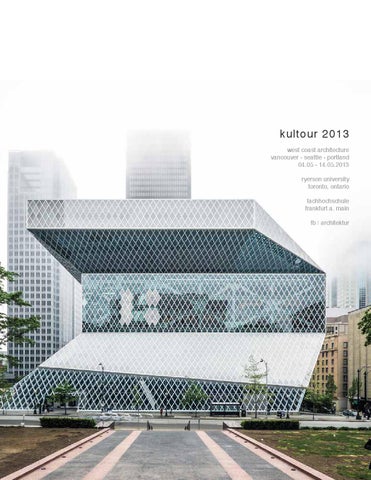

kultour 2013 west coast architecture vancouver - seattle - portland 04.05 - 14.05.2013 ryerson university toronto, ontario fachhochschule frankfurt a. main fb | architektur

1

kultour 2013 west coast architecture vancouver - seattle - portland 04.05 - 14.05.2013 ryerson university toronto, ontario fachhochschule frankfurt a. main fb | architektur

1