E N Q U I R Y

LEARNING & RESEARCH AT DOWNE HOUSE

Welcome to the Lent term edition of our staff Learning and Research Journal, the Enquiry. Across this issue you will find a wealth of ideas and reflections from members of the Downe House community about all things educational research and Teaching and Learning.

We begin, importantly, with a section devoted to student perspectives about their own learning experience. Here, we asked students from different year groups to write a brief summary of something they enjoy or find useful in their learning. They were given no further brief or guidance. The comments are, not surprisingly, very insightful!

We then move onto a section that looks at metacognition and what this might mean in the classroom. We begin with an article by Kerry Treacy that combines our own Downe House DNA with its possible use as a metacognitive tool within the classroom. Isla McLachlan then explores the same topic of metacognition, but in relation to a project she completed as part of her PGCE, again with a focus on how metacognition might help to improve students learning outcomes.

This section is then followed with one on pastoral and student wellbeing, with Alice Startup reporting on a conference she attended in which they explored how to help students to break the rumination cycle. This neatly connects back to the previous section, both connected by the focus on helping students to self-reflect and self-regulate.

We conclude with a section based around different aspects of memory and revision. Our Deputy Head, Matt Godfrey, begins this section by offering an account of how to revise effectively in the words of our own pupils. There are lots of great tips here, all the more important as we move into Summer term. Rachel Philipps-Morgan then looks at the broader topic of retrieval practice and how she is utilising this in her own practice. Jane Basnett then explores the many benefits of Quizziz, not only for its retrieval capabilities but also how it might help us to plan lessons, before Andy Atherton looks at a start of lesson routine he favours that again helps students with recalling valuable information.

Justin Bartholomew, to conclude this issue, offers his thoughts about the excellent book, Dan Willingham’s Why Don’t Students Like School?

Our thanks go to everyone that took the time to write and submit an article as well as Sue Lister who was instrumental in preparing and designing this edition. The next edition of The Enquiry will be published in Michaelmas 2022 as a retrospective of Summer term. A Call for Papers will be announced soon, but if you have an idea and would like to contribute please do get in touch with any member of the Editorial Committee.

A

The Enquiry Editorial Committee

Andy Atherton

Charlotte Williams

Kerry Treacy

George Picker

STAFF JOURNAL DEDICATED TO REFLECTIONS ON EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH AND TEACHING AND LEARNING AT DOWNE HOUSE SCHOOL

One lesson strategy that my teachers use that I find really helpful is a start of lesson quiz. We do it unaided as soon as we arrive. It is a memory exercise to recall what we learned in the previous lesson. We do this during our English lessons with Dr Atherton and it is mainly to help us remember quotations and things about characters. It may be recreating a sheet we did during the last lesson or getting us to remember certain images. We often have to remember a number of quotations from a poem or text we have been studying and I find that it really helps me with recalling them! I also find that it means we all have something to do when we come into the lesson, which means that it does not take up much of the lesson time because we have not been chatting to one another. It means we can recall quotes and explanations more quickly so we don’t need time to think about them in the exam, giving us more time to write the essay. The start of lesson task does not always directly relate to exam skills but can be fun too! It has also helped me to get into a mindset that is ready for the lesson and to enjoy learning. This strategy has helped me immensely with preparing for my exams and helps with remembering even really obscure quotations!

One of the most fundamental challenges a student faces with any subject is the recollection of knowledge. It is this that often hinders a student’s learning: the persistent ritual of writing quotes and historical facts on flashcards, endlessly and without considering the fascinating, subtle complexities that a piece of writing may contain.

As a student who loves essaybased subjects, particularly English, an aspect of class that I find significantly valuable to my learning is whole class discussion. Not only is it sharing ideas that fuels my interest for the subject, but the response involved as well. The opinion of another, or an intricate idea that I may not have considered, makes the lessons constantly intriguing. It is this active participation that partly makes class discussion so valuable, as writing a response or essay afterwards can seem significantly easier, and thus, it can be carefully crafted, thought provoking and complex. The response and feedback involved in a class discussion is key to one’s learning. Students acquire analytical skills and learn to think comprehensively on the spot. This instant generation of ideas

is a skill that is crucial in any essay-based exam, and therefore, although class discussion allows students to delve into a topic in more depth and detail, it helps with exam preparation as well. Ultimately, the thing most crucial to a student’s learning, is intellectual intrigue and whole class discussion promotes this. But we must consider, how can one topic, quote or even word be so interesting? It fundamentally comes down to the passion a teacher has for their subject, and how they use this in the classroom to enhance their students learning. Class discussion is particularly interactive, promoting the learning of material and allowing a more profound, complex approach to a topic. One where content and depth can be tackled in synthesis. Despite GCSEs looming, a teacher’s persistent passion for their subject and an interactive class is a powerful combination. It is one that has continued to shape my love and interest to learn and I have never more thoroughly enjoyed my favourite subjects than now.

ULTIMATELY, THE THING MOST CRUCIAL TO A STUDENT’S LEARNING, IS INTELLECTUAL INTRIGUE AND WHOLE CLASS DISCUSSION PROMOTES THIS.

One thing I find particularly valuable to my learning is a proactive approach in lessons such as whole class activities like discussions or acting out sections of books in which everyone gets involved. In particular, discussions are invaluable in lessons. It is not only more interesting to be listening to everyone’s different interpretations and ideas but also really effective. We are able to gain from all these different perspectives and use a combination of all our ideas in our work. This means we always have ample amount of points to make in essays. While having traditional points from our teachers we also come up with different ideas which add further interests and in-depth views to our essays. I find it extremely interesting that we all notice different things that others may not have considered. Activities that engage the whole class mean

everyone is more focused as we are all involved. Other interactive activities such as Kahoot or Quizlet live I know are super popular. Even though we are all 16 and 17 years old, we still love games as we all have healthy competitive spirits! Games are always a lot of fun while effectively testing our knowledge and understanding. These kinds of activities are also helpful for active recall and can break up the lesson. I sometimes find it easier to get distracted, particularly near the end of a lesson when we have been consistently note-taking. Although reading and writing from a board is helpful and gets the information across, when more collaborative activities are used, I find I remember the work better. When copying down from a whiteboard, I don’t always fully take in what I am writing and can go into autopilot, whereas if handson activities are used around notetaking, I find it a lot more effective. Through an interactive approach more people are involved and engaged in every lesson but also have something to look forwards to like a game at the end.

DESPITE GCSES LOOMING, A TEACHER’S PERSISTENT PASSION FOR THEIR SUBJECT AND AN INTERACTIVE CLASS IS A POWERFUL COMBINATION. IT IS ONE THAT HAS CONTINUED TO SHAPE MY LOVE AND INTEREST TO LEARN AND I HAVE NEVER MORE THOROUGHLY ENJOYED MY FAVOURITE SUBJECTS THAN NOW.

A PUPIL IN THE LVI EXPLORES THE IMPORTANCE OF INTERACTIVITY IN ONE’S LEARNING

MISS KERRY TREACY (HOUSEMISTRESS OF YORK, TEACHER OF DRAMA) EXPLORES HOW WE MIGHT USE OUR DOWNE HOUSE DNA AS PART OF OUR LESSONS, FOCUSSING STUDENT ATTENTION ON THE SKILLS THEY ARE AND COULE BE EXHIBITING.

At Downe House, there is a clear message that we communicate to parents and prospective parents; we develop the students to discover how they will navigate our ever-changing world. We look for opportunities both inside and outside of the classroom to develop the Downe House ‘DNA’ maximising their ability to be successful both professionally and personally. But do we maximise the use of the Downe House DNA in our classrooms explicitly? Not only is this a great way to demonstrate to prospective parents how we prepare their child to be an exceptional person in society, but it can be an incredible tool in the classroom to develop metacognition.

I’m sure that we have all spent time at some point throughout our teaching careers discussing metacognition and the benefits that this would have on

our students. Students having an understanding and knowledge about and being able to regulate their own thinking develops their creativity, problem solving, analytical, collaborative, and communicative skills (Conyers & Wilson, 2016:2). By developing metacognition in our classrooms, we are supporting the brain strengthening neuronal connections, synaptogenesis, which in turn supports students improving not only their academic ability, but their brain’s ability to change and grow over time (Conyers & Wilson, 2016:24). To support the development of metacognition, students will need to understand the cognitive processes that they go through and evaluate their use. When investigating cognitive processes, we can fall into the pitfall of identifying the challenges that may be facing our students rather than selecting the cognitive tools that we wish to bring to the lesson explicitly to teach with metacognition (Conyers & Wilson, 2016:10). Many of us instinctively teach with metacognition as we will identify the cognitive processes, or tools, that students could apply to their work. However, I am curious as to how we may further develop our practice through utilising the Downe House ‘DNA’ and embedding this in our lessons.

The brilliantly creative marketing team explored how to visually bring to life the attributes that we identify as the Downe House DNA. This concept considered what we would aim to instil in the students to best prepare them for the challenges they will face in the working world. And so, we decided on the following attributes:

■ Aspiration

■ Collaboration

■ Communication

■ Compassion

■ Creativity

■ Outward looking

■ Resilience

■ Digitally ready (newest addition)

I would like you to cast your minds back to January 2020. For those of us that were here working at Downe House, we undertook an INSET session in which we were asked, in departments, to explore the characteristics of the Downe House DNA and consider how they are identifiable in our classrooms. Each department gave a wealth of examples as to how each strand of the DNA was presented in their teaching practice to benefit the student’s development holistically. Some subjects naturally lend themselves to an attribute such as Drama; through exploration of the social, cultural, historical, and political context surrounding a set play, students are building empathy and compassion for a character’s given circumstance. The Maths department are consistently demonstrating the benefit of building resilience as students endeavour to solve problems and overcome the barriers they may be faced with particularly problematic equations. It was inspiring to hear from representatives from each department sharing how they embed the DNA in their teaching practice to further support the students.

As mentioned previously, teaching with metacognition is a way to explicitly model metacognition and the cognitive processes, or tools, in the classroom to enable students to develop these skills further. When stepping away from the January 2020 INSET session, I was faced with a question: how might we use the Downe House DNA to model cognitive processes? This question ruminated in my mind as I explored how we could explicitly explore the use of the DNA in our classrooms. Initially, I printed the icons and placed them on the whiteboard as though following a learning journey for each lesson. The Outward looking icon would be used to pose a ‘bigger question’ for the lesson to encourage the students to consider how the content may relate to issues we are facing in society. The Aspiration icon would sign post the extended learning task for those students who needed further challenging in their learning. This then led me to incorporating the icons into my PowerPoint presentations however, I found the students were not fully engaging with this concept. Some students were not fully aware of what each icon meant and how this may relate to their learning.

Developing my use of language in the classroom was the next step to take. Through explicitly labelling a task to develop their resilience through a ‘Do Now’ activity as they entered or developing their communication through offering verbal feedback to a peer, we were then beginning to see students being able to identify the cognitive process they were using. As lessons continued and the students became more familiar with each icon, we could see the student’s confidence grow as they continued to practice an array of cognitive processes. With further practice, the students will be developing their neuronal connections strengthening their brain’s ability to change and grow, thus embedding the Downe House DNA for life.

I am curious as to how you may embed the Downe House DNA in your classrooms whether that be through your language, displays, PowerPoints or marking. Consider how you may develop your practice of teaching with metacognition through the use of the Downe House DNA and share this within departments. This could be the beginning of a new marketing tool for our staff; whoever you are, whoever you want to be, be a Downe House teacher.

WITH FURTHER PRACTICE, THE STUDENTS WILL BE DEVELOPING THEIR NEURONAL CONNECTIONS STRENGTHENING THEIR BRAIN’S ABILITY TO CHANGE AND GROW, THUS EMBEDDING THE DOWNE HOUSE DNA FOR LIFE.

MISS ISLA MCLACHLAN (TEACHER OF ENGLISH) EXPLORES HOW SHE HAS USED METACOGNITION WITH HER LV CLASS IN ORDER TO IMPROVE THEIR PERFORMANCE, WITH A SPECIFIC FOCUS ON THE BENEFITS OF MODELLING. THIS IS A SHORTENED VERSION OF A WIDER RESEARCH PROJECT COMPLETED AS PART OF A PGCE.

As part of my teacher training, I decided to complete a study investigating metacognition with my LV class, focussing on AQA GCSE English Language Paper 2 Section B. This section is centred on creative writing, and I measured the impact of modelling using test results and student questionnaires. This study followed the January mock exams and enabled me to explore truly helpful methods of building upon the work completed during this examination period.

This study was influenced by:

■ a Guidance Report by the EEF

■ Sweller’s research into worked examples

■ Dent and Koenka’s idea of standard of work

■ Tharby’s five practical principles for implementing modelling in the classroom

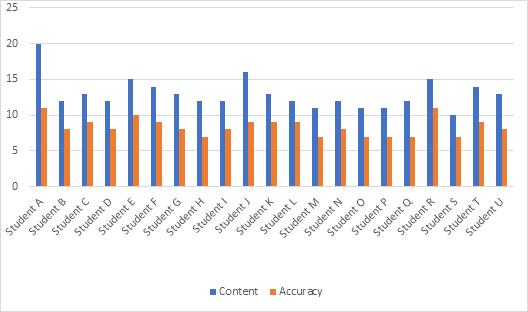

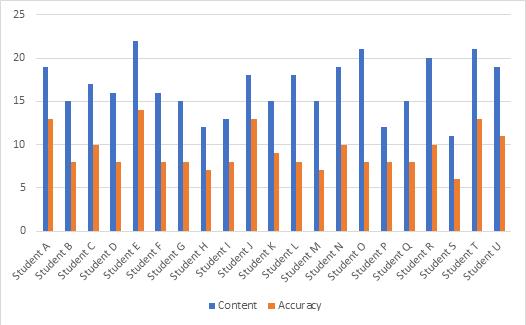

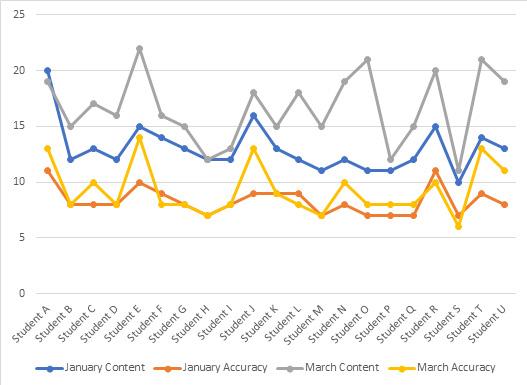

The quantitative data for this study was collected using two domainreferenced tests. The test marks are split, according to AQA’s marking criteria, into “content” (out of 24 available marks) and “accuracy” (out of 16 available marks).

I also used questionnaires to ask students to reflect on the lesson which had just taken place, in which a response was modelled by me, taking ideas from the class into consideration, as well as to reflect on the marks they had achieved in their March assessment. The students moved through individual, personal

tasks reflecting on their personal performances in their mock exams, to marking model paragraphs followed by colour-coding a model essay according to its more and less successful elements.

■ study does not take student effort levels or motivation into account, nor how much preparation or revision was completed in advance of assessments.

■ time-scale, as this study was conducted over a period of only two months with one hour per week dedicated to this study.

Student S achieved one mark higher for both content and accuracy. Student H’s marks remained the same for both content and accuracy. Student E’s accuracy marks increased by 5, while her content increased by 7, and Student L’s accuracy marks increased by 1, while her content increased by 6. Student K’s accuracy mark remained the same, but her content increased by 2 marks. For students B, I and M their accuracy marks remained the same, while their content marks increased by 3, 1 and 4 respectively. Student O’s accuracy mark increased by 1 mark, and her content increased by 10. Of those thirteen students who have not been identified as EAL, SEN or academically more able, each individual student’s overall mark increased by 4.8 ± 3.3 (mean ± standard deviation). Statistically, the mean is a calculation of the average mark increase, while standard deviation depicts the spread of marks across the cohort.

The results of this study suggest that modelling has a positive impact on students’ overall marks. No student lost marks between the January and March tests, however, there is a discrepancy between the impact modelling appears to have had on marks awarded for content and accuracy respectively. It is possible that modelling was

THE OVERALL OUTCOMES OF THIS STUDY MAKE A STRONG CASE FOR THE IMPORTANCE OF MODELLING WITHIN TEACHING ESPECIALLY WHEN COMBINED WITH OPPORTUNITIES FOR METACOGNITIVE REFLECTION.

effective in terms of producing new ideas regarding tone, style and register, but the short time scale did not provide enough time for modelling to impact grammar, spelling or sophistication of language.

As Figure 5 outlines, every member of the class’ overall mark improved in the March test, when compared with the January test, with the exception of Students H and S, whose overall marks remained the same.

Modelling appears to have had a neutral impact on accuracy marks for some students, however does seem to have a net positive impact across the class. The content marks of students B, I, K and M increased by 2.5 ± 1.3. Although there was a 1 mark decrease in accuracy marks for Students F, R and S, this did not result in an overall mark decrease for either student. However, students B, F and U commented that they did not think of the modelling exercises whilst completing the March test, but still thought that these exercises helped them to complete it. These students, therefore, suggest that modelling can have an unconscious impact as well as a more explicit one for other students.

The overall outcomes of this study make a strong case for the importance of modelling within teaching especially when combined with opportunities for metacognitive reflection.

MISS ALICE STARTUP (ASSISTANT HOUSEMISTRESS YORK, TEACHER OF HISTORY) EXPLORES CURRENT RESEARCH SURROUNDING HOW TO HELP STUDENTS TO BREAK THE RUMINATION CYCLE.

I recently attended a Conference for Early Career Teachers that explored many aspects of the teaching profession and gave both generalised and subject specialist information. One of the lectures I attended was given by Professor Patricia Riddell from the University of Reading, who explored how we can help our students, both pastorally and academically, by giving them the tools to differentiate their negative emotions, as well as breaking the cycle of rumination. I found this lecture fascinating, and after further research, I realised the importance of differentiating negative emotions.

A recent study conducted by the University of Rochester (2019) claimed that students who cannot clearly express their feelings or who generalise their negative emotions by saying ‘I am sad’ or ‘I feel bad’ rather than pointing to the exact emotion, are more likely to suffer from generalised depression and lead to them snowballing towards panicking and a vicious cycle of repetitive negative emotions. This obviously has an impact on their academics as they are less likely to concentrate and become focused on these feelings. Not all negative emotions are bad, and experiencing negative emotions helps to build resilience in students however constant experiences of negative emotions can be detrimental to pupil progress and motivation.

WE CAN HELP OUR STUDENTS, BOTH PASTORALLY AND ACADEMICALLY, BY GIVING THEM THE TOOLS TO DIFFERENTIATE THEIR NEGATIVE EMOTIONS, AS WELL AS BREAKING THE CYCLE OF RUMINATION.

During the lecture, Professor Riddell dealt with how we can help our students when they experience these negative feelings and how they can break the rumination cycle that occurs when pupils cannot effectively deal with their negative emotions. Whilst much of the lecture focused on how different parts of brain affect students processing their feelings, what I found most interesting was the differences between Depression, Anxiety, Stress and Overwhelm. The most commonly confused emotions are stress and overwhelm, and the words are often used interchangeably even though they mean completely different things.

Professor Riddell explained that stress prevents students relaxing and puts them in a constant state of alert where they are likely to become irritable if there is delay or interruption to their activities, whereas overwhelm leads to apathy and often results in students simply stopping everything, as the body cannot carry on and must rest – often coined as burnout. So, if we can identify how a student is feeling, we need to then help them to recognise it too without it spiralling to rumination. Simple exercises such as asking students to say out loud how they feel and then breaking this down further to pinpoint their exact feelings can help them feel calmer. I have recently tried this in the boarding house, and students who were able to break down their feelings responded much more to support

and were able to begin to recognise whether their issues were blown out of proportion or not.

Another interesting aspect of Professor Riddell’s lecture was how rumination affects our students. When students constantly think about the same negative emotions, there is a risk of this developing further into generalised depression or anxiety. Helping students to stop ruminating is vital if we are to support them. Professor Riddell suggested many practical tips to help students, such as thinking of and completing one small action, or talking or writing down how they are feeling, or asking themselves what advice they would give to a friend in their situation and to follow this. These are all very good strategies, but when working with students, particularly in the boarding house, I have noticed that they are unable to recognise when they are ruminating and therefore continue to work themselves into a state, usually about events in the past or things they have no control over. Once again, by working with students to help them differentiate their negative emotions they will become more confident in recognising when they are ruminating and will eventually, given the tools, be able to break the rumination cycle with minimal support. This is why mindfulness is so important to students, as it gives them practical tools to help them distract their brains in a controlled and calm manner. I have found that

explaining to students that they are ruminating and are fixating on past events they have no control over allows them to begin to move into breaking the cycle naturally, and gentle tips such as deep breathing or visualising random objects helps them to begin to calm down. Even tiredness plays a role here, as when we are tired or have just awoken, perhaps in the middle of the night with worries, our logical brain is “turned off” and things will seem much worse than they are. Students should be reminded to revisit these thoughts in the morning when they are well rested – it will not be as bad as they think it is! Breaking the rumination cycle is vital to help students build resilience and will help them to prioritise their emotions.

Overall, the lecture showed me the scientific angle of what we see with our students everyday –whether they are upset, angry, annoyed, bored or overwhelmed. It allowed me to think practically about how we can help our students to build their resilience, whilst also giving them the tools to support themselves as they face new challenges beyond the safe space of Downe House. Differentiating negative emotions is hard, even for adults, but by talking to and listening to our students, we can help them to start to recognise how they are feeling and support them to use the tools they have learnt to make negative emotions feel less daunting.

SIMPLE EXERCISES SUCH AS ASKING STUDENTS TO SAY OUT LOUD HOW THEY FEEL AND THEN BREAKING THIS DOWN FURTHER TO PINPOINT THEIR EXACT FEELINGS CAN HELP THEM FEEL CALMER.

EFFECTIVE REVISION STRATEGIES WITH PUPILS WHO ARE FACING GCSE AND A LEVEL EXAMS THIS SUMMER.

The pandemic means that our current UV and UVI girls will be the first pupils in two years to sit conventional GCSE and A level exams in the summer. So, ahead of the Easter holidays, I gathered some pupils whose teachers had told me were smart and effective workers – and I grilled them on their revision strategies. This is what they told me: and while different techniques work for different pupils, there should be something for everyone here. There’s even a couple of tips for parents…

YOU ALL DO LOTS OF SUBJECTS AT GCSE: WHAT’S THE BEST WAY TO MANAGE THE WORKLOAD?

Jocelyn (UV): “I am doing 11 GCSEs, so there’s a lot to learn! Some subjects are more time consuming than others – like Textiles. I condense each topic for each subject into bullet points on a sheet or card. For example, I create a flashcard for each case study in geography. Compressing the information in this way makes it easier to learn.”

Queena (UVI): “I spent a great deal of time completing practice papers for GCSE. It was effective but now, at A level, I find it more valuable to read around my subjects – it’s more interesting, and I learn more that way, too.”

Juliette (UV): “I must prioritise and decide which subjects I need to spend most time on. Some subjects are more content heavy than others.”

WHAT STRATEGIES DO YOU USE FOR MEMORISING INFORMATION?

Zara (UV): “I find testing myself on a mini-whiteboard very helpful. I learn and then write out a Latin passage or my English quotes on a whiteboard –then I check, correct and wipe it clean – and then repeat until I feel confident I know it all.”

ALL pupils: Quizlet is a highly effective way to learn language vocabulary. “I created a 500-word Quizlet for my Latin vocabulary” (Zara, UV).

Tilly (UVI): “As part of my A level revision, I like to do a past paper for each topic: it helps me to remember and reinforce my learning. I also use a whiteboard to help memorise important information. I’m a fan of mind maps –they can be a really good way to organise your thoughts and give you a kind of ‘picture’ to remember. It’s a good idea to break each subject down into smaller, more manageable topic areas.”

Queena (UVI): “I learn through speaking. I write detailed notes and then I read them to myself – aloud –even if other people think I’m crazy! Sometimes I record myself and listen to myself repeatedly until the information sinks in.”

Tilly (UVI): “Everyone is motivated in different ways. Ultimately, you must make the decision to work yourself: once you do this, you will make time to study effectively. I aim for five hours of work a day – with some days off.”

Zara (UV): “I turn a timer on when I work – simply so I can see how long I’ve worked for. I find it satisfying at the end of a revision session and can see that I have been working for a long time.”

Queena (UVI): “I don’t like to work within a time limit: I am more list orientated. I like to write down a list of goals for the day as it’s really satisfying ticking them off.”

“I TURN A TIMER ON WHEN I WORK –SIMPLY SO I CAN SEE HOW LONG I’VE WORKED FOR. I FIND IT SATISFYING AT THE END OF A REVISION SESSION AND CAN SEE THAT I HAVE BEEN WORKING FOR A LONG TIME.”

Alice (UV): “I tried using lists but I wasn’t very good at estimating how long each task would take – and it can be quite demoralising if it takes a long time to work though a list. So, I prefer to set myself a time limit for revision during the holidays – it’s 4-5 hours each day.”

Alice (UV): “The Forest app is a very useful tool for keeping focused. You can set the time that you want to remain focused – say, 30 mins – and during this period a ‘digital’ tree will begin to grow on your phone’s screen. But if you touch your phone, the tree dies! You gain points each time a tree grows fully, and then you can trade these points in to plant a tree in the real world – so, an app with a green conscience! Another app, Pomodoro, is simple but effective: set a timer for 25 minutes, work until it runs out, then take a 5-minute break – and repeat the process three more times. After that, take a 15- to 30-minute break. That’s one full Pomodoro cycle. Despite how basic it sounds, the Pomodoro Technique is incredibly effective.”

Zara (UV): “I think pressure from parents is counterproductive. Personally, I feel guilty if I don’t work sufficiently hard – so I guess it’s a built-in motivation.”

Juliette (UV): “My elder brother was very lazy and so I benefited from witnessing him and realising I didn’t want to make the same mistake!”

Tilly (UVI): “I think Downe House is good at making you take responsibility for your own learning. I wasn’t great up to GCSE but I have become better at this during A levels.”

Queena (UVI): “The scientist Richard Feynman said that the best way to learn something is to teach it. I agree. So, if I really want to understand a topic, I can choose a friend or relative and try to explain it to them. It’s an effective way to learn something yourself and it forces you to really understand what you are talking about.”

Juliette (UV): “I find the CGP revision books very helpful and clear (especially the maths and science ones): so, get your parents to buy them!”

Queena (UVI): “Personally I like to work in my room: everything is familiar and convenient. But I do also like working in the Murray Centre – it can be refreshing to have a change and the atmosphere is conducive to study. I sometimes stay there for five hours at a time at the weekend.”

Tilly (UVI): “I love the Murray Centre – particularly on Sundays. I like to go there and find my own space, and I can take my time.”

Zara (UV): “I know some students find it helpful to work in one of the organised study sessions during the evenings (6.30pm7.30pm and then 7.30pm-8.30pm). It can just be helpful to be in a room of other people who are focused on their learning.”

My thanks to our revision experts quoted in this article, and I hope some of their tips are useful to other pupils out there. Happy revising!

MRS RACHEL PHILLIPS-MORGAN (DEPUTY DIRECTOR SAUVETERRE) DISCUSSES HOW SHE HAS BEEN USING RETRIEVAL PRACTICE IN HER OWN PRACTICE AS WELL AS THE UNDERPINNING COGNITIVE RATIONALE.

In December 2021, as we eagerly awaited the arrival of our first group of students to France, the teachers at Downe House Sauveterre undertook some academic research to help develop our practice. The focus of the research was teacher-led, so after being inspired by the retrieval practice study the English Department had undertaken at Downe House UK, I decided to focus on retrieval practice and which techniques are proven to be most effective at strengthening recall.

Hermann Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve seemed a good place to start my research, since the rate at which new information is forgotten is, quite frankly, alarming! His experiments into how memory fades over time helped reveal several key features about memory:

■ Memories weaken over time.

■ The biggest drop in retention happens soon after learning.

■ It’s easier to remember things that have meaning.

■ The way something is presented affects learning. The same set of information can be made more or less memorable, depending on how well it’s communicated.

■ How you feel affects how well you remember.

All of these points made me immediately think about my own teaching and to consider how I account for these in my day-to-day practice, particularly how I address and manage the fact that the biggest drop in retention happens soon after learning. Reflecting on my teaching, I realised that in my planning I regularly prioritised other components of teaching and learning, particularly content delivery (for Key Stage Three and GCSE), variety, engagement and exam technique (A-Level), and whilst I have always known that retrieval is a vital component of effective learning, it dawned on me that in my planning I take more of a ‘scatter-gun’

approach to retrieval practice, incorporating retrieval regularly, but randomly, rather than applying a consistent and considered approach.

In looking for a more consistent approach to effective retrieval practice, my research took me to The Learning Scientists, whose short instructional videos online I found highly informative and accessible.

WITH EACH RETRIEVAL OF TAUGHT INFORMATION, THE RATE OF MEMORY DECAY SLOWS DOWN MORE AND THUS THE INFORMATION BECOMES MORE DIFFICULT TO FORGET. THE INFORMATION THEN BECOMES MORE EMBEDDED IN THE LONG-TERM MEMORY.

Their research produced six key strategies for effective retrieval, which are:

■ Spaced Learning

■ Interleaving

■ Elaborate

■ Examples

■ Dual Coding (words and visuals)

■ Retrieval practice

The above strategies used in conjunction are proven to be high-impact and effective in strengthening recall.

Whilst it offered me comfort to know that many of these things I have already been using in my guidance to students about effective revision, Spaced Learning and Interleaving in particular are techniques that I hadn’t really emphasised previously.

Spaced learning is returning to the same piece of information, but with different spaces of time between. This helps address the memory loss reflected in Hermann’s Forgetting Curve. With each retrieval of taught information, the rate of memory decay slows down more and thus the information becomes more difficult to forget. The information then becomes more embedded in the long-term memory.

Interleaving is also an approach I will emphasise more going forward, particularly when it comes to revision guidance. This is where you switch between topics regularly in your retrieval practice and revision, and whilst this is likely to be more challenging, it is proven to be a more effective technique in embedding information in the long-term memory.

This research has allowed me to reflect on my own practice and has armed me with more effective strategies that are proven to strengthen recall. In my planning, I am now even more aware of how important it is to always begin a lesson with a short review of previous learning, as well as engaging students in a weekly and monthly review much more consistently. Despite the inevitable pressures of pace and content delivery, I want my planning to truly reflect the mantra ‘we revise throughout the course, not just at the end’, so I have moved retrieval significantly up my priority list. Providing revision guidance and strategies that are backed by scientific research also allows me to say with more confidence to students that they need to move beyond rereading, highlighting, and copying in their revision, no matter how comfortable they are with these approaches, to the six active retrieval strategies listed above. Armed with this active approach to retrieval, they are sure to give themselves every chance of success when it comes to the exams.

I am not sure that when I first started teaching – over a quarter of a century ago – that I considered this question as seriously as I do now. My planning and the resources I created back then were so very different to my planning nowadays. Today, my curiosity about my students’ learning leads me to consider the quality of learning going on and how I can adapt what I am doing to further improve progress.

Indeed, just before the millennium the acronym AFL (Assessment for Learning) came into teacher speak and is now very much part and parcel of the teacher toolkit. Assessment for Learning (AFL) “is about empowering pupils to be owners of their own learning” (Gadsby, 2012) and is essentially a cyclical process that “aims to close the gap between a learner’s current situation and where they want to be” (Cambridge Assessment International Education, n.d.). Thus, AFL plays a big part in improving learning and

THE MANY USES OF QUIZZIZ, EXAMINING ITS CAPABILITY NOT ONLY FOR STUDENT RETRIEVAL BUT ALSO FOR TEACHER PLANNING.

over the years there have been numerous well-known strategies that I have employed to enable me to understand how my students are progressing.

However, with the advent of digital technologies this whole process has been significantly enhanced and has become much more effective not just for me but for each student in my class. One of the most powerful outcomes of using technology in assessment is that learning is adapted so that each individual’s needs are met, and learning is no longer simply a one-size fits all experience. In this article I am going to focus on Quizizz which is a tool that can be used in all subject areas.

I am concentrating on Quizizz because it is a tool for which the school has recently bought a subscription and with this subscription comes some compelling technology that will undoubtedly enhance student learning and teacher awareness of their students’ progress which, in turn, will feed forward into teacher planning.

This is an online tool that gives both teacher and students an in-depth understanding of current learning. Quizzes no longer need to be based solely on the written word but can also feature video clips from You Tube or even audio clips. If the quiz is set up as a lesson, as opposed to an ordinary multiple-choice question and answer test, slides can contain useful information that move learning on, and these slides can be created, in situ, on the website or imported from previously created PowerPoints. Of note, is that the site has a huge bank of questions already in existence that can be used as they are or simply adapted to meet the teacher’s needs. Questions need not be restricted to multiple choice as it is possible to pose open-ended questions, gap-fill questions, drawn responses and polls. It is possible for students to provide audio and video responses which really opens up the options and provides great flexibility.

As well as instructor-paced lessons and quizzes where the teacher controls the pace and can see at a glance how students are coping, there are also student-paced lessons and quizzes, where learners

can proceed at their own pace and can immediately address any misconceptions they might have. For me, this latter is of huge importance because not only can I ascertain my students’ progress, but they can see for themselves how they are progressing and understand where the gaps are in their knowledge, allowing them to move on independently.

Furthermore, with our subscription we can supplement questions with some detailed answer explanations and links to further help our students in their acquisition of knowledge on particular topics thus catering for the different needs of individuals (Check out https://edpuzzle.com for a tool with similar functionality). Of course, the ability to complete these tasks as part of a student paced lesson or prep means that learning can advance in an appropriate direction for each student at a pace that is right for them.

And now to the aforementioned ‘compelling technology’. Tests can be set up in such a way that reattempts become more meaningful. So, the system allows the instructor to request students to attempt a test a number of times. Via adaptive algorithms each student will receive a unique set of questions which will focus on previously incorrect responses and unseen questions allowing for deeper learning at every attempt. It is the closest thing to a student having their own individual teacher at their side whilst they are learning. This online ‘teacher’ can assess learning and address confusion by providing extra help when a student gives the wrong answer and can thus facilitate student progress.

The magic of Quizizz does not stop there. As a teacher, the data that can be captured is very detailed and indicates how individuals need to progress and how objectives for whole classes can be adapted. Quizzes like those we can set on this website are more about learning than ‘testing’ per se. For students, the lowstakes quizzing provided by the website allows them to recalibrate their understanding of what they do and do not know, and this is undoubtedly one of the best habits we can instil in our students.

ONE OF THE MOST POWERFUL OUTCOMES OF USING TECHNOLOGY IN ASSESSMENT IS THAT LEARNING IS ADAPTED SO THAT EACH INDIVIDUAL’S NEEDS ARE MET, AND LEARNING IS NO LONGER SIMPLY A ONE-SIZE FITS ALL EXPERIENCE.

At the start of this issue of The Enquiry, we heard from three Downe House pupils about what they find most valuable in their learning. One student, Hermione, emphasised how useful she finds lessons that begin with a quick start of lesson quiz. Without realising it, Hermione is describing here a strategy that Doug Lemov calls a Do Now task. Hermione expertly identifies the benefits of this start of lesson routine just as ably as Lemov himself would. As such, in this article, I wanted to explore how this routine works, how to deploy it as effectively as possible, and why, as Hermione identifies, it can be a really valuable way to start a lesson.

In its simplest form, a Do Now task is a short activity waiting for students as they enter the classroom, which, when a routine expectation, ensures students can begin work immediately and without prior instruction or discussion.

According to Lemov, an effective Do Now task should conform to four criteria to ensure it remains effective and focussed:

■ It should be located in the same place each lesson so that students know exactly where to look. This might be on the board, a piece of paper, pre-uploaded to OneNote in the same section each time, visible on a PPT slide. The location does not especially matter so long as it is consistent.

■ Students should be able to complete it without any direction from the teacher and without any discussion, and, in most cases, without any material aside from what is already provided. This is partly what separates the Do Now from other kinds of start of lesson activities that might require prior instruction once students are seated and ready. The function of the Do Now is to be completable in and of itself. As Lemov explains, ‘some teachers misunderstood the purpose of the Do Now and start by explaining to their students what to do and how to do it’. As the aim is to build a habit of selfmanaged independent work.

■ The activity, whatever it might be, should take 3 to 5 minutes to complete and typically require some kind of written outcome. This better enables the teacher to hold students to account for its completion, as well as more easily being able to identify who is and is not engaging.

■ Broadly speaking, the activity should either preview the day’s lesson or review previously taught material. In this sense,

a typical Do Now might ask students a question that will feed into the day’s lesson or be some kind of retrieval task.

According to Lemov ‘the single most common downfall I observe with Do Nows is a teacher’s losing track of time whilst reviewing answers’ so that ‘the Do Now has replaced the lesson that was originally planned’. Lemov suggests that the review ought to be roughly the same amount of time given to students to complete the task, which is 3 to 5 minutes.

This necessitates, as Lemov explains, the art of ‘selective neglect’. It would not be possible to review

every student response and instead the review ought to be predicated on sampling a selection of responses and extrapolating from that sample a sense of how the class as a whole may have fared. This can then inform immediate next steps, if you have identified an obvious misconception, or feed into what material ought to be revisited in a subsequent Do Now.

Lemov also makes the point that the ideal review should, generally speaking, be combined with Cold Call so that the sample is a more accurate representation of class performance and not determined by volunteered responses.

As described in Lemov’s original criteria, the ideal Do Now is something that can be completed without teacher instruction or intervention; the learning begins before the lesson itself. As such, and whilst of course specifics may always change from class to class, teacher to teacher and lesson to lesson, a typical Do Now routine may look something like this:

■ The Do Now is waiting for students in an expected location and the format of the task is well rehearsed so as not to introduce unnecessary complexity: the material might be complex, but ideally not the way in which it is presented or delivered

THE IDEAL DO NOW IS SOMETHING THAT CAN BE COMPLETED WITHOUT TEACHER INSTRUCTION OR INTERVENTION; THE LEARNING BEGINS BEFORE THE LESSON ITSELF.

■ Students enter the classroom and immediately begin working on the Do Now task independently and without need for discussion (unless of course that is part of the Do Now procedure)

■ There is some kind of review of the Do Now

■ The lesson begins in a more formal sense with the teacher welcoming the students and beginning that day’s material

All of this might take in the region of 10 minutes and the above routine can be explicitly taught and rehearsed with students until it becomes second nature, with the option to review and refresh if needed later in the year.

by Dan Willingham

by Dan Willingham

I have an admission: for much of my early teaching career, I held the secret belief that much of what we were being told, about how to teach, was not entirely based on fact. I remember when this sneaking suspicion first crept in during in my NQT year. A visiting consultant impressed upon us newbies the absolutely vital act of writing the lesson aims on the board before every class. Learning would be severely impaired (or so we were led to think) if this simple ritual was not assiduously adhered to. Upon asking the be-suited chap on which research his claims were founded, he replied, (apparently without irony) that he was unaware that there had been any research conducted on this issue at all. Of course, it was extremely difficult to swim against the tide at the time as even OFSTED, built their judgement of a teacher’s lessons precisely on this kind of spurious thinking.

Fast forward to 2014 and a discovery that began to restore my faith in our profession. I read Seven Myths About Education by Daisy Christodoulou and it was like turning on a light. For those teachers that have not read this it is a forensic examination and demolition of certain pervasive educational orthodoxies that, as Christodoulou outlines, are either not based on the available research or even run counter to it. Although superbly written, what

makes Christodoulou’s arguments most compelling is that they are based on meticulous research. This text, and others like it, have been at the vanguard of a new evidence-based approach to education; one that promises to yield genuine and worthwhile results.

Since Seven Myths, I have read various books about teaching, but none had the same impact until last year when I read the entertainingly written Why Don’t Students Like School? by Daniel Willingham. In this text, the author lifts the lid on the science of learning and most importantly, how our actions in the classroom impact our students’ cognitive processes. Some of his findings are surprising and even counterintuitive, but every one is based on extensive research. Now, as my intention in writing this piece is to encourage you to read the book yourself, I thought I would share my top three take-aways –something incredibly hard to do with a book that is absolutely jam-packed with great ideas and insight. Anyway, here goes:

■ Although the title of the book is designed to be provocative, there is more than a grain of truth underpinning the assertion that ‘students don’t like school’. Willingham deals with this early on stating, “People are naturally curious, but we are not naturally good thinkers; unless the

cognitive conditions are right, we will avoid thinking.” The idea that “the mind is not designed for thinking” may sound flippant and indeed, just plain wrong, but the scientific evidence is overwhelming, and the author ably demonstrates the veracity of his assertion through a series of cognitive tasks for the reader to try (and fail) themselves. The fact that, “compared to your ability to see and move, thinking is slow, effortful and uncertain” is the key principle that guides all of Willingham’s advice.

■ If we accept that thinking is hard, then as teachers we need to, “respect students’ cognitive limits.” One of the most fascinating insights for me was learning about the interplay between our vast long-term memories and our highly limited working memories. Learning involves the use of both and to introduce too much new information in one go causes the cognitive load to be so much that it impedes learning. A way we can help is by ensuring that students are constantly growing their long-term memories with relevant subject knowledge. This will help to prevent working memory from becoming overloaded – a common source of student dissatisfaction with learning.

■ Closely linked to the importance of memory is another fact that

Willingham draws attention to: “Factual knowledge must precede skill.” Although many readers will think this is blindingly obvious, I must point out that during my teacher training, I was confidently told by a deputy head that we were “in the business of teaching skills, not knowledge”. When I politely suggested that skills could not exist in the absence of knowledge, I found myself outranked, and therefore ‘wrong’. Willingham is keen to show his readers that what he asserts is also true – you do not merely need to place blind trust in what he says. In one fascinating experiment he cites, it was found that the best predictor for whether or not a child would comprehend a text about baseball, was not their general reading ability (skill) but whether or not they had a pre-existing interest in the game (knowledge).

This list could easily contain ten, twenty or even fifty points and they are all solid, pedagogical gold. Most importantly perhaps, is the specific advice that Willingham gives regarding how we might use this knowledge to better prepare our lessons and teach our students. If you read only one book about teaching, make it this one. I mentioned Seven Myths About Education at the beginning of this article and it is an excellent book.

However, it should be noted that Christodoulou herself was influenced by Daniel Willingham’s work and whilst Seven Myths is an excellent read, Why Don’t Students Like School? treats the subject in rather more depth.

LEARNING

INVOLVES THE USE OF BOTH AND TO INTRODUCE TOO MUCH NEW INFORMATION IN ONE GO CAUSES THE COGNITIVE LOAD TO BE SO MUCH THAT IT IMPEDES LEARNING. A WAY WE CAN HELP IS BY ENSURING THAT STUDENTS ARE CONSTANTLY GROWING THEIR LONG-TERM MEMORIES WITH RELEVANT SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE.

5 invaluable lessons from cognitive science | Feature | RSC Education

This short but excellent article suggests 5 essential lessons from cognitive science that undoubtedly will have a positive impact on teachers’ practice

Noise and the Art of Mirror-Modelling | Round Learning

An excellent blog post on how to get modelling right

Teaching | A note on marking and feedback –Kat Howard (wordpress.com)

A very valuable reflection on marking and feedback and how to do this in a sustainable and effective manner

Ruth Ashbee: The Dos and Don’ts of Curriculum Leadership – ResearchED In this conference presentation Curriculum Leader Ruth Ashbee explores the keys to great curriculum design.

Our book of the term Slow Teaching by Jamie Thom, and many more, are available for staff to borrow in the Staff Research Library, situated in the Staff Common Room.

For a book that claims to help find calm and clarity in the classroom, this is perhaps more relevant now than ever before. Here, Thom explores what he describes as ‘slow pedagogy’ and the positive impact this approach can have on student outcome. This includes discussions of classroom management, classroom dialogue, building meaningful relationships, and leadership. The book provides an excellent exploration of the power of deliberate, purposeful and ‘slow’ teaching.

02.

Conyers, M. & Wilson, D. (2016). Teaching Students to Drive Their Brains: Metacognitive Strategies, Activities, and Lesson Ideas. ASCD.

Hartman, H. J. (2002). Metacognition in Learning and Instruction; Theory, Research and Practice. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hillwig, S. A. & Kolencik, P. L. (2011). Encouraging Metacognition; Supporting Learners Through Metacognition Teaching Strategies. P. Lang.

Perfect, T. J. & Schwarte, B. L. (2022). Applied Metacognition. Cambridge University Press.

03.

MODELLING METACOGNITIVELY

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2007) Research Methods in Education. 6th edn. Oxon: Routledge.

Denscombe, M. (2008) ‘Communities of Practice’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 2(3), pp. 270-283.

Dent, A. and Koenka, A. (2016) ‘The Relation Between Self-Regulation Learning and Childhood Achievement Across Childhood and Adolescence’, Educational Psychology Review, 28(3), pp.425-474.

Durrington Research School (2018) Developing a ‘Disciplined Inquiry’ Approach. Available at: < https:// researchschool.org.uk/durrington/news/developing-adisciplined-inquiry-approach/> (Accessed: 1-11-20).

Muijs, D., Stringer, E. and Quigley, A. (2018) Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: Guidance Report. Available at: https:// educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/ Publications/Metacognition/EEF_Metacognition_ and_self-regulated_learning.pdf (Accessed: 11-12-20).

Sweller, J. (2008) ‘Cognitive Load Theory and the Use of Educational Technology’, Educational Technology, 48(1), pp. 32-35.

Tharby., A (2015) How To Use Modelling Successfully in the Classroom. Available at: https://www.tes.com/ news/how-use-modelling-successfully-classroom Accessed: 10-02-21).

07.

Brown, P., Roediger III H. L., McDaniel M. A, (2014). Make it stick. The Science of Successful Learning Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

From www.cie.org.uk: https://www.cambridgecommunity.org.uk/professional-development/ gswafl/index.html#:~:text=%20Assessment%20 for%20learning%20in%20practice%20%20 1,thinks%20about%20their%20own%20learning.%20 This...%20More%20?msclkid=ed074767b04211ecad8a8a4d0c3ad3c8

Gadsby, C. (2012). Perfect Assessment for Learning. Independent Thinking Press

WHOEVER YOU ARE, WHOEVER YOU WANT TO BE, BE A DOWNE HOUSE TEACHER