LEARNING & RESEARCH AT DOWNE HOUSE

Welcome to the Lent term edition of our staff Teaching and Learning journal, the Enquiry. Across this issue you will find a wealth of ideas and reflections from members of the Downe House community about all things Teaching and Learning.

We begin, importantly, with a section devoted to student perspectives about their own learning experience. Here, we asked students to write a brief summary of something they enjoy or find useful in their learning. They were given no further brief or guidance. The comments are, not surprisingly, very insightful!

We then move on to three articles that explore, in different ways, the role of challenge and support within the classroom. Setting the scene, Andrew Atherton introduces us to the concept of desirable difficulties from the research of husband and wife, Rob and Elizabeth Bjork. Often, they argue, what seems difficult in the short term in fact enhances progress and learning in the long term. Next, Matt Rivers and James Seddon consider the role that support plays within the Physics Department and then Tim Breeze explores the vibrant debates within the MFL community about when and when not to teach in the target language.

Next, we move on to an article about Downe House’s unique model of CPD, Excellence in Teaching. The focus this term has been metacognition, and colleagues reflect on what this is and why it matters. We then move on to an article by Jane Basnett that explores collaboration and the role it plays in the classroom as well as how this can be enhanced through digital technology.

Finally – and a fitting end to this edition – Matt Godfrey explores why being a teacher is an incredibly worthwhile career; sentiment shared, I’m sure, by everyone reading this!

Our thanks go to everyone that took the time to write and submit an article. The next edition of the Enquiry will be published in Michaelmas 2024 as a retrospective of Summer term 2024. A Call for Papers will be announced soon, but if you have an idea and would like to contribute, please do get in touch.

Dr Andrew Atherton Director of Learning and Research

A STAFF JOURNAL DEDICATED TO REFLECTIONS ON EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH AND TEACHING AND LEARNING AT DOWNE HOUSE SCHOOL

DONG (UV) TALKS ABOUT THE VALUE OF STARTING A LESSON WITH A SHORT RETRIEVAL QUIZ AND WHOLECLASS DISCUSSION.

I have been introduced to and used many different techniques for learning, but one technique that I have found particularly useful in terms of having better self-recognition and improvement would be the starter questions at the beginning of every lesson. Not only can these questions help you recall the information from the previous lesson, but they are also valuable opportunities to gain insights into our strengths and weaknesses and use that knowledge to get one step closer to our goal. Furthermore, I feel that this technique starts the lesson with an impact by involving the students from the moment they enter the classroom.

Another technique that I have always found beneficial is wholeclass discussion. As well as being able to share your ideas with your friends, which can help increase the students’ attention and help maintain their focus by involving them in the learning process, class discussions can also encourage students to learn from one another and to articulate course content in their own words. On a deeper level, I feel that class discussions provide a framework for students

to think critically out loud about the topics being covered in class.

Personally, I think that getting feedback from your teachers would probably be the best way to improve, as it influences how students feel about their course, their performance, and themselves. Whether it is how you learn or just a simple comment in general, which can go a long way, effective feedback provides specific guidance on how to improve learning outcomes and enables students to think about the learning involved in the task and not just the activity of completing the task. Therefore, it would be important to have structured feedback in such a way as to maintain or increase students’ motivation and to encourage them to focus on learning goals rather than performance goals (e.g. passing a test).

(UIV) COMMENTS ON WHY GOING OUTSIDE IS SO VALUABLE FOR HER LEARNING.

Something that really helps my learning is going outside. When I’m inside, sometimes it feels a bit stifling, but when I’m outside, I feel so much lighter, and I think a change of scenery can really benefit your ability to learn. Obviously, it comes with its drawbacks: the sun makes it

tricky to see your laptop screen, the weather always tends to be against you, and you have to dress up according to the weather, but if you can find a shady spot it makes all the difference. My favourite memory of school was when I was nine years old, in the month leading up to the summer, my teacher decided that we would do all our English lessons outside, under the shade of the willow dome. As a result, my classmates and I became not only more interested in the book we were learning about, but also happier and less argumentative (which I was very grateful for – some of the classroom squabbles got quite heated). Since then, I often go outside to work, especially in the summer, as I find it improves my focus, helps me memorise things, and makes my mood better, and I’m not alone in this: studies show that it leads to increased happiness, improved creativity, reduced stress, and better focus.

OF RETRIEVAL QUIZZES, LESSONS START WITH AN IMPACT BY INVOLVING THE STUDENTS FROM THE MOMENT THEY ENTER THE CLASSROOM.

EXPLORES THE CONCEPT OF DESIRABLE DIFFICULTIES AND WHY THEY MAKE A DIFFERENCE TO STUDENT LEARNING.

As discussed in the February issue of the Enquiry, and as outlined by Nick Soderstrom (2019), ‘long-term learning can be enhanced by intentionally impairing short-term performance’ (2019). Strategies that appear to hinder or disrupt short-term progress (performance) can in fact have great benefit for long-term understanding and retention (learning). These strategies are what Bjork has labelled ‘desirable difficulties’ (1994), desirable because they improve long-term learning, but difficult because they might appear to slow progress initially.

In this issue of the Enquiry, we’ll discuss each of the three desirable difficulties that Bjork outlines and the implications they may have for classroom teaching.

Rather than being only viewed as an assessment of the learning that has already taken place, Bjork (2011) and Henry Roediger (2006) argue that testing should be seen also as a way of facilitating future learning. What is called the testing effect describes the fact that the act itself of being tested and successfully retrieving information leads to more effective long-term retention. Testing, then, in the words of Bjork, should be viewed as a learning event in its own right and not just a measure of all other learning events.

With this in mind, we might consider which of the following four might be most conducive to long-term learning:

■ A: Study Restudy Restudy Restudy Test

■ B: Study Restudy Restudy Test Test

■ C: Study Restudy Test Test Test

■ D: Study Test Test Test Test

Despite students often feeling most comfortable with (A), which is because it induces short-term performance, (D) is far more effective for long-term retention because it harnesses the testing effect. The testing becomes part of the sequence of learning and not simply a future assessment of it. This manner of studying also taps into what is called the generation effect, which describes the fact that if a student generates a solution or answer as opposed to being presented with one then retrieval is strengthened. This is assuming, though, there are not fundamental flaws or gaps in understanding, in which case reteaching would be most beneficial: the testing effect assumes there is enough of a knowledge-base to be tested.

But what kind of testing would be most beneficial? The key to harnessing the power of the testing effect is to use frequent, low-stakes quizzing. Low-stakes quizzing, as opposed to the high-stakes testing of mock exams, can take many forms (with other suggestions listed in Sherrington’s post at the end), such as:

■ Flashcards or apps such as Quizlet

■ Knowledge dumps

■ Quizziz

■ Kahoot

■ Retrieval relay

■ Microsoft Forms

■ Elaborative-Interrogative

■ Paired quizzes

It is also especially beneficial, and logistically effective from a teacher’s point of view, for these low-stakes quizzes to be self-marked wherever possible.

This also has the added benefit of tapping into a student’s metacognitive awareness of their own current strengths and weaknesses (‘I don’t seem to know X very well so I should revise it more’).

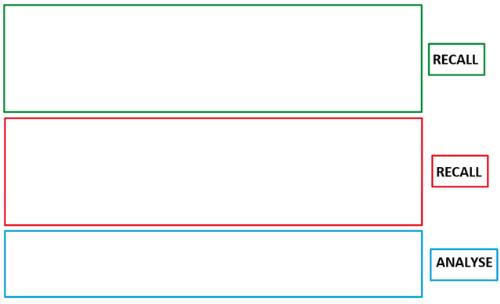

One way in which to integrate low-stakes quizzing into lessons is to begin every lesson with a retrieval task based on previously learned material. The above format, waiting for the students on the board as they enter the classroom, covers material from the last lesson (green), the previous topic (red) and then a longer, more analytical question (blue). [1]

Whatever format it might take the key takeaway is that the opportunity for retrieval of information that promotes generation is more effective than a further study event. Whilst restudying may enhance performance, it tends not to be as effective for long-term retention. What this looks like will obviously vary from classroom to classroom and discipline to discipline.

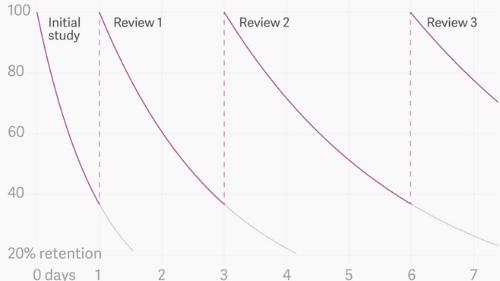

One of the reasons students find massed practice (like cramming) so attractive is because it does enhance short-term performance, but it is deadly for long-term retention of information. It has long been understood that over time we become less likely to be able to retrieve information previously learned (especially when it has been crammed) and so revisiting material at regular intervals facilitates longterm learning, an idea related to the Theory of Disuse. Ebbinghaus’ original research into memory decay, called the Forgetting Curve, is typically represented as shown. [2]

What is interesting to note is that the initial rate of decay after first studying the material is very steep, but that with each subsequent spaced review the forgetting curve is actually eased, increasing what is called its retrieval strength. Thus, as Ebbinghaus initially demonstrated and as has subsequently become what Bjork calls one of the most robustly

evidenced ideas across the study of memory, every time a memory is retrieved, that memory is more accessible in the future. The more we revisit material at regular intervals across time the more robust our recall of that information becomes.

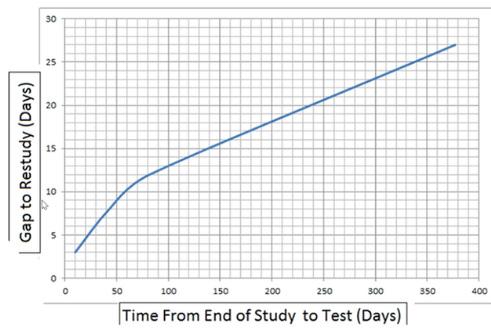

The perhaps more salient question, though, is what is the optimal time to revisit material after initial study?

In a recent ResearchEd presentation and based on an Action Research project into Ebbinghaus, Damien Benney constructed the above graph that plots the optimal gap between initial study and review in light of when that material will be needed for a future examination. For instance, using the above, if an examination was due in 50 days from the point of initial teaching then Benney concluded the optimal gap would be a total of nine days, perhaps much sooner than one might anticipate. [3]

It is here that synergies between the testing effect and spacing effect become most powerful. What would be the best way to revisit the previously taught material and to return to it at regular intervals? Following Bjork and Roediger, the answer would be to revisit by using low-stakes testing as a learning event. As such, building time into a sequence of learning for frequent revisiting of previously studied material will help students to retain it in the long term.

AS BJORK

EXPLAINS,

‘BLOCKED PRACTICE APPEARS OPTIMAL FOR LEARNING BUT INTERLEAVING ACTUALLY RESULTS IN SUPERIOR LONG-TERM RETENTION’.

Interleaving is often held in contrast to blocking where the latter refers to material being studied in one single sequence, but interleaving refers to material from several related areas being taught continuously. This is similar to spaced practice, but whereas spacing typically refers to distributing the same topic, interleaving involves distributing different types of problem or topic.

The example that Dunlovsky (2012) gives is to imagine a student learning addition and subtraction. Typically, they might spend a block of practice adding and then a block of practice subtracting. The next topic may then introduce division and multiplication and practice may begin with one before moving to the other. This would be an example of massed practice or blocking. However, interleaving would involve solving one problem from each type before solving a new problem from each type. As Bjork explains, ‘blocked practice appears optimal for learning but interleaving actually results in superior long-term retention’. Blocking feels neater and shortterm gains give the illusion of it being more effective, but research would indicate this is not necessarily the case.

The efficacy of interleaving can partly be explained because it naturally compels spaced practice, but it also helps to promote making connections across and between different topics, which can result in high-order thinking.

Both spacing and interleaving have fascinating implications for curricular design and the sequencing of content. Is it better, for instance, to teach Topic A and then Topic B or to find a way to interleave material from Topic B during the study of Topic A? What would be the best way to revisit material from Topic A during the study of Topic B? What topics or materials are closely related enough to benefit from being interleaved? As with any such questions, answers need always be rooted within specific disciplines and debated by subject experts as no one answer will fit all.

MATT RIVERS (HEAD OF PHYSICS) AND JAMES SEDDON (TEACHER OF PHYSICS)

OUTLINE THE SUITE OF SUPPORT THAT EXISTS FOR STUDENTS AT DOWNE HOUSE STUDYING PHYSICS.

ACADEMIC INTERVENTIONS

PHYSICS

Study sessions, mentoring, clinics, and action plans all form essential parts of academic life at Downe House, providing extra support to those girls who, for whatever reason, are currently underperforming in a subject. These strategies are collectively known as academic interventions and they are purposeful, targeted work packages, designed to give a lending hand to bring the girls back on track.

How teachers select whom is to be given an academic intervention can be a difficult question. Historically in Physics we have used a teacher-led approach, where each teacher is asked which of their pupils they think

will need an intervention. After all, the teachers know their pupils best so they should have a well-informed idea. This was then cross-referenced against MidYIS data to help judge whether an intervention would be likely to lead to significant improvement.

Whilst the historical method has arguably worked quite well, there is a question of fairness. On the whole, we would imagine that a girl requiring intervention would be identified as such regardless of her teacher. However, this cannot be guaranteed.

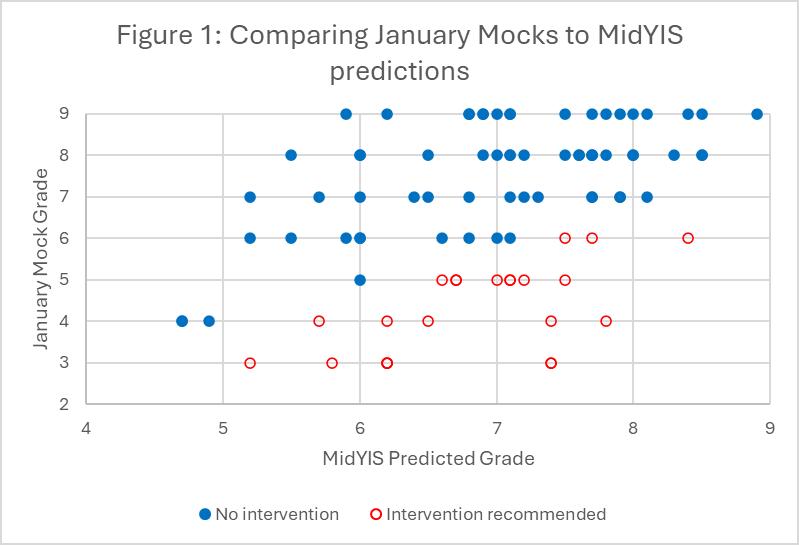

With the above in mind, this year we tried something different. Rather than depending primarily on teacher knowledge, we have switched the order to use data first and then teachers. In the first step, we use pupil data to generate a list of girls perhaps needing intervention. In the second step, we use individual teacher knowledge to confirm the names on the list that was generated from the first step.

The data-driven approach has two aspects:

Forward-looking, where we compare the girls ‘now’ to their predictions for the final exams, allowing for the fact we expect some further growth. An example of this is shown in Figure 1, which compares data for an anonymised Upper Fifth (UV) from their January Mock grades and their MidYIS predictions. In this example, we have assumed that the girls’ grades will increase by a further 1.0 between January and the GCSEs, so a girl currently scoring 1.5 grades or more below their predicted grade is highlighted as requiring intervention. Why do we choose to compare Mock data to MidYIS predictions? Pragmatically, it is readily available. Why do we choose a grade uplift of 1.0 between Upper Fifth (UV) January Mocks and GCSEs? This is the ‘best case’ whole-year average performance from recent years, but there is an argument that we should use the ‘average case best.’

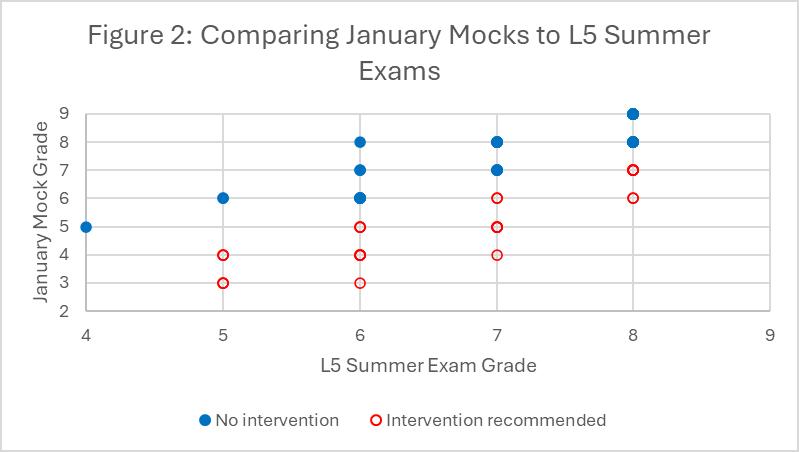

Backward-looking, where we compare the girls ‘now’ to their most recent previous exams. The data from our sample year is shown in Figure 2, where we have identified girls perhaps needing intervention as those scoring less in the Upper Fifth (UV) Mocks than in the Lower Fifth (LV) summer exams.

OUR NEW APPROACH HAS IDENTIFIED 28 PUPILS IN UPPER FIFTH THIS YEAR AS REQUIRING INTERVENTION, WHICH IS SIGNIFICANTLY MORE THAN WE HAVE IDENTIFIED IN RECENT YEARS, SO OUR NEW APPROACH HAS CLEARLY MADE A DIFFERENCE.

The data-driven approach provides two lists of girls requiring intervention: those that were identified by the comparison to future predictions and those that were identified by the comparison to previous exams. The lists are then circulated to the relevant Physics teachers to confirm the names and add any others. This allows teachers to use their knowledge of the specific girls to highlight, for example, extraordinary circumstances which should be taken into account, and the list is altered accordingly.

Our new approach has identified 28 pupils in Upper Fifth this year as requiring intervention, which is significantly more than we have identified in recent years, so our new approach has clearly made a difference. We will have to wait and see whether the GCSE grades will be correlated with this extra support, but from speaking with several of the girls on the intervention, they all said that they found it valuable.

Moving forwards, the system is not yet complete. Questions exist over how much uplift to expect at various stages of a ‘standard’ trajectory, whether to include value added? Or whether girls following nonstandard trajectories are accurately identified. We are also keen to explore how grade uplift over the final year of the course varies between pupils at different levels of attainment.

We want the very best for the girls and we want to ensure clear strategies are in place to provide additional support where it is needed.

TIM BREEZE (TEACHER OF CHINESE AND HEAD OF THE ELECTIVE PROGRAMME) EXPLORES SOME OF THE FASCINATING DISCIPLINARY DEBATES THAT TAKE PLACE WITHIN THE MFL TEACHING COMMUNITY ABOUT HOW TO USE THE TARGET LANGUAGE IN TEACHING.

The role of the target language (TL) spoken by the teacher in foreign language classrooms has long been a subject of debate among educators. While some advocate for complete immersion in the TL, others posit a more balanced approach that incorporates the

use of both the TL and the students’ native language (L1). Advocates of full TL immersion argue that it provides students with an authentic language learning experience, akin to natural language acquisition. They believe that sustained exposure to the TL facilitates the development of superior listening and speaking proficiencies, along with cultural comprehension (Swain & Lapkin, 2000). Immersion also encourages students to think in the TL, promoting fluency and reducing reliance on translation (Krashen, 1981).

However, the practical application of full TL immersion often presents challenges, especially for beginners or

younger learners. Students may feel overwhelmed or frustrated when they do not understand instructions or explanations given by the teacher solely in the TL. From my own experience of learning languages, it is very easy to ‘switch off’ when listening to long stretches of the TL and await familiar English cues. This can lead to decreased motivation and comprehension, hindering students’ overall language acquisition. From the teacher’s perspective, using the target language may slow down the pace of instruction, putting extra pressure on the limited time available to cover the curriculum.

In the Mandarin Chinese classroom, the teacher’s use of the target language is complicated further by several challenging aspects inherent to the Chinese language. Notably, Chinese and English lack cognates –words in two different languages that have similar or practically identical meanings (Yang et al, 2017), with only a minuscule subset of words such as ‘咖啡 kāfēi coffee’ and ‘沙发 shāfā sofa’ exhibiting any semblance to English. Moreover, Chinese has a relatively few numbers of sounds and syllables, meaning that lots of the language can sound very similar to the listener, with the addition of tones compounding the problem further. Therefore, for novice Chinese learners, listening to a Chinese teacher speaking the TL in the classroom can be a daunting task, requiring the use of a range of strategies to support and improve students’ listening skills.

One of the key strategies when it comes to promoting my own use of the TL is using as much Chinese as possible, even if this is at the expense of delivering an absolute authentic experience (Macaro, 2005). Much of my ‘teacher speak’ in the classroom is formed using intra-sentential code-switching, where a key word or phrase is switched to Chinese or English (Macaro, 2005), focusing on the use of high-frequency of words such as ‘作业 zuòyè prep’ and ‘安静 ānjìng quiet’. Although this is considered by many teachers to ‘neither be an asset nor a valuable addition’ (Macaro, 2005, p. 63), my strategy is to select and focus on these words and expressions and use them at every available opportunity in the classroom, as well as encouraging students to use them, thereby ensuring consistent exposure for students over the three-year GCSE course.

I am aware that sometimes this style of ‘teacher speak’ might result in some words and phrases being used in an unnatural way and there is definitely an argument that this type of recourse to ‘Chinglish’ can be a contentious issue (Macaro, 2005). Nonetheless, given the time constraints and complexities associated with the GCSE Chinese examination – in particular the formidable listening component – I feel taking every opportunity to immerse students in as much Chinese as possible should be paramount.

ATHERTON (DIRECTOR OF LEARNING AND

KATHARINE HENSON (DIRECTOR OF CURRICULUM), AND ISLA MCLACHLAN (TEACHER OF ENGLISH & KS4 CO-ORDINATOR) REFLECT ON THE LATEST CPD CYCLE OF OUR EXCELLENCE IN TEACHING, FOCUSING ON METACOGNITION.

Investing in teacher training means investing in better pupil outcomes. This is something we take very seriously at Downe House, and for good reason. Effective teacher training is often cited as one of the most effective levers for improved pupil progress. Educational researchers Rob Coe and CJ Rauch explain, CPD is ‘arguably the single most important thing that teachers and school leaders can focus on to make a difference in children’s learning’.

Part of Downe House’s suite of opportunities for helping teachers to improve so pupils learn better – and there are many – is our flagship CPD cycle, Excellence in Teaching. The idea is a simple one, but incredibly powerful. Every term colleagues deliberately focus on a different pedagogic strand related to Teaching and Learning, with previous topics including student motivation, collaboration, and scaffolding. Each cycle is divided into three related phases:

■ Introducing the Strand: Colleagues are introduced to the termly strand by someone from within the Common Room who has a particular interest or expertise in it. Learning from each other, colleagues better appreciate the pedagogic principles underpinning the given focus.

■ Departmental Discussion: Over several weeks, colleagues adapt and experiment, trying out new ideas in their classrooms related to the termly strand. They come together within their departments to discuss what the topic looks like within the context of their specific disciplines and what it might look like in their teaching.

■ Sharing Best Practice: Finally, having tried new approaches, colleagues come back together to evaluate and share what has and hasn’t worked.

Excellence in Teaching gives colleagues the golden opportunity to focus on a specific area of their practice over a sustained period of time, trying new things and learning from one another. It leverages our collective expertise whilst allowing space to really reflect and evaluate what works in our classrooms.

The focus for the Lent term is metacognition. In the rest of this post, let’s consider what exactly this is and why it matters.

Often defined – perhaps too simplistically – as ‘thinking about thinking’, metacognition describes the various cognitive and emotional processes that take place within a student before, during and after they complete a given task. It is about self-knowledge and how students can use this to perform even better on whatever it is they’re doing. As Jenny Webb describes, ‘a metacognitive learner is one who has knowledge and control over cognitive skills and processes’.

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) (one of the most trusted and significant research bodies for education) further defines metacognition into three areas:

■ Knowledge: the knowledge students have about the task at hand and what it is they need to do.

■ Regulation: the insight students have during the task itself in terms of how well they are doing and whether they ought to change their strategy.

■ Motivation: the motivation students must have to continue with the task, even when it gets difficult.

In this first session of our Excellence in Teaching cycle, colleagues – led by Andy Atherton, Director of Learning and Research – discussed this definition of metacognition and, crucially, shared practical strategies for how to help students become more metacognitive learners.

We’ll now hear from Katharine and Isla as they reflect on what metacognition might look like in the classroom for them.

What does metacognition look like in the Maths classroom?

■ It’s OK to get things wrong. Encourage students to learn from their mistakes, ask why it went wrong, how might they adapt their strategies?

■ Learning through patterns: be prepared to try things out and look for similarities that aid understanding.

■ Break problems down into smaller parts: identify the information in the problem and start with the simple steps, the next steps will become more apparent as you gather information.

In summary, encourage confidence and independence with a ‘have a go’ attitude.

Perhaps for English the most common integration of metacognition in the classroom takes the form of modelling. This is more than simply writing an essay while students watch: it includes taking note of the thought processes going through the teacher’s mind either orally or in a separate location on the page. This embeds students centrally in the process, rather than allowing them to take the role of passive observers.

In order to succeed in English, it is also essential that a student is self-reflective and able to apply their targets in a way that addresses the mark scheme’s stipulations for improvement. The department has designed various reflective tasks which invite the students to identify where their targets are applicable to their own work and rewrite this section accordingly.

On a more creative level, GCSE students are offered the opportunity to attempt creative writing individually before offering and adapting their ideas in a wholeclass setting to produce a model essay which everyone has contributed to. In summary, metacognition pervades each English lesson at Downe House, be this in Literature or Language, analysing a writer’s methods or using methods of one’s own creatively.

JANE BASNETT (DIRECTOR OF DIGITAL LEARNING)

OFFERS A PRACTICAL EXPLORATION OF HOW TECHNOLOGY CAN HELP US TO ENCOURAGE COLLABORATION WITHIN THE CLASSROOM

I am an advocate for pedagogyinformed teaching. I firmly believe in grounding educational practices in robust pedagogical theories and methodologies. As such, I do not use technology just because I have access to it, but because it very much enables me to undertake a wide variety of activities in a more effective and efficient manner. As we all know, technology should be

used in a way that enhances the learning experience and augments the feedback that can be given to the pupil and the fast observations that can be made via the rich data accessible to the teacher.

In The Learning Rainforest, Tom Sherrington discusses two distinct teaching styles, labelled Mode A and Mode B, underscoring the idea that educators often alternate between various teaching methods to enrich and diversify learning experiences. Mode A encompasses traditional, teacherdirected instruction as its core, while Mode B encompasses a wide range of student-centred activities. In Mode B, students

often have the opportunity to choose their learning path, which may include in-depth discussions or collaborative work, highlighting the dynamic nature of teaching practices. On this occasion I would like to focus on the latter.

Obviously, there are many benefits of working together, not least the ‘learning gains’ (Sherrington, The Learning Rainforest) for pupils, the support they give each other and the feedback they provide. Technology offers an excellent opportunity to get pupils engaging together synchronously or even asynchronously. For the teacher, being able to check individual and group outcomes

at the end of the task or at any given moment during the process is invaluable and not so easily achieved when the collaborative task is completed on paper which then gets taken away not to be seen by the teacher until the next lesson. But I am moving too fast. Let’s go back to the beginning and consider how a group activity should be set up.

As with all group work (whether online or on paper), it is important to establish the ground rules, setting out who will complete which part of the task and giving all pupils the opportunity to reflect on their own work as well as looking over the work of the others in their group. Whilst each member will have a role to play it is important to remember that they are working collaboratively to produce a whole. The role played can be established prior to the activity or by the teacher themselves; no one should be a passenger and the collective outcome hinges on every individual’s effort. Technology enables the seamless tracking of each participant’s contribution allowing for a quick overview of everyone’s involvement.

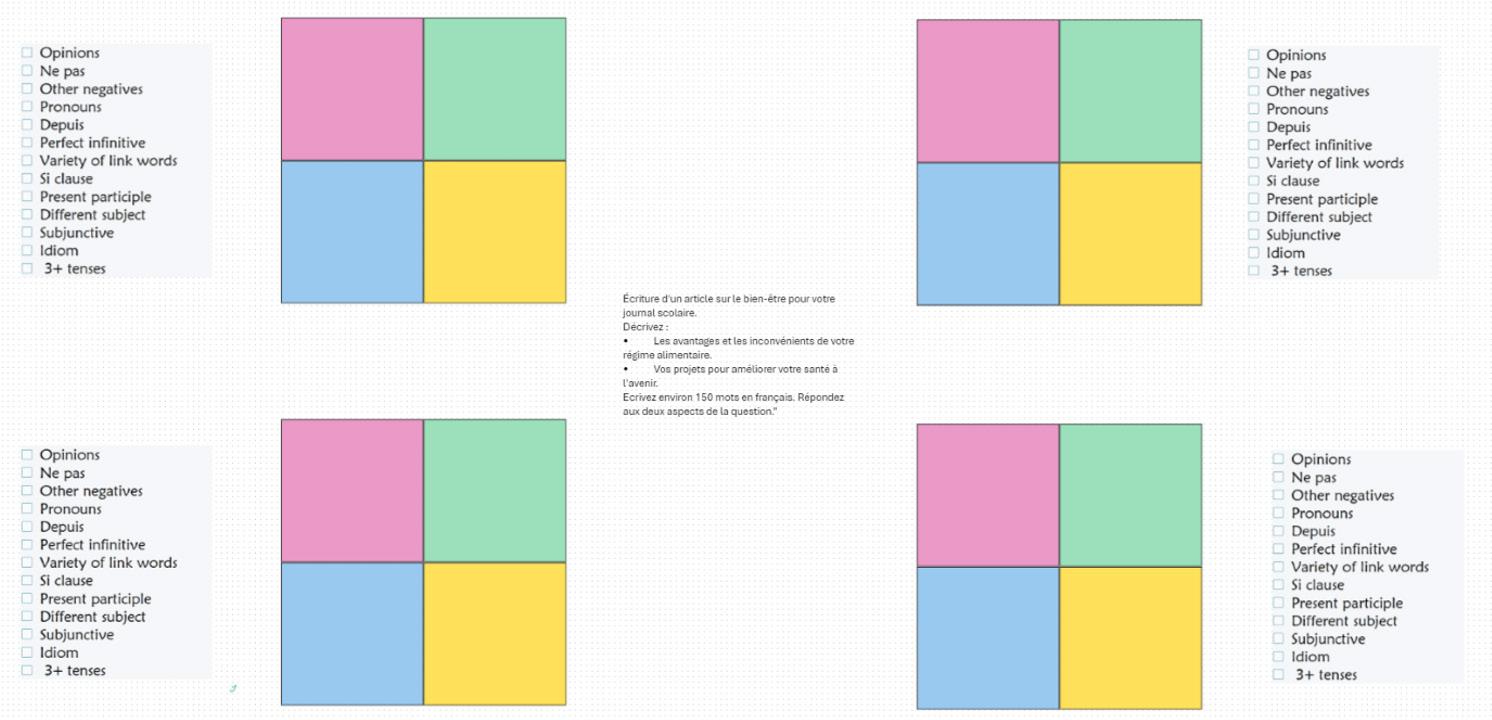

My recent experience with this kind of task has focused on the production of a 150-word essay for GCSE French. This is the more complicated of the two essays that pupils write and it is the one that causes the most anxiety. It is helpful, when modelling how to complete the essay, to suggest that pupils break down the two-bullet point question into smaller chunks, which does mean that pupils have to decide for themselves how they would like to develop their essay. Add to this, the fact that pupils know that there are linguistic challenges they must meet, the essay can seem a little overwhelming. After a conversation with my Head of Department I realised that the 150-word essay is the perfect task to be completed collaboratively.

There are a number of tools that can be harnessed for collaborative learning, but, in my opinion, none is better than the tools that we have at our disposal via Microsoft Office 365; the collaboration space in Class Notebook or Microsoft Whiteboard. For both these tools, it is possible to set up a template, thus saving you valuable time. [1]

With a template, the only item that would need to change would be the title and perhaps the list of grammatical structures might need adapting depending on the stage of learning.

With the template set up, the class split into four groups (or as required), and the task can be commenced. Within their groups pupils can discuss how to break down further the two bullet points and discuss the grammatical structures they might employ, making decisions about which structures work most effectively given the essay topic and where they might fit best. With the overview, the teacher can quickly see how each individual is working, which direction they are taking their essay and steer the group accordingly, checking individual and group outcomes. [2]

Tackling the essay in this way obviously means that as a teacher, there are fewer essays to review, detailed feedback can be given more quickly and this benefits both teacher and pupil alike. Furthermore, with both Microsoft Whiteboard and the collaboration space in Class Notebook, pupils can have access to all essays and learn from each other; it is a very powerful way to enable success for a task that can be considered hard by the pupils.

One further advantage of this collaborative approach is the opportunity to participate in important discussions about digital citizenship. As pupils navigate sharing the same online space, it becomes essential for them to adopt constructive digital citizenship behaviours. Establishing clear guidelines and promoting a culture where students stop to consider their actions, aiming to respond with positivity and empathy, is crucial. Do not underestimate the importance of this aspect of the collaborative task. It might take pupils a moment or

two to get focused, but ultimately, as they build up their response as a group even the most recalcitrant individual can see the benefits of working in this way.

Historically, before the use of technology, teachers might have eschewed collaborative tasks due to the challenges in guaranteeing that every student contributes equally. Moreover, identifying activities where each person’s contribution is both suitable and enhances the collective outcome has been a concern. My experience, this time, has shown me that not all the discussions about individual responsibilities yielded fruitful results and the process of group evaluation was sometimes overlooked. However, on the whole, the groups did review their work well. Even so, I intend to focus on individual responsibility and the review process in such future endeavours. Nonetheless, I am convinced that leveraging technology to facilitate teamwork presents numerous benefits and is an undeniably smart strategy which we should readily embrace.

TO CONCLUDE THIS EDITION, MATT GODFREY (DEPUTY HEAD) OFFERS SOME FINAL WORDS AS TO THE JOY AND POWER OF A CAREER IN TEACHING.

Have you been watching the Netflix series One Day? The Guardian gave it a five-star rating, describing it as a ‘highly bingeable love story packed with magnificent nostalgia and a sublime soundtrack’. I strongly agree and I highly recommend it.

The series is based on David Nicholls’ 2009 best-selling and much-loved novel of the same title (also highly recommended by me, by the way!). The two main characters, Dexter and Emma, meet at Edinburgh University in 1988, and the subsequent epic love story spans the following 20 years, with all the action taking place on a single date on each subsequent year, 15 July, St Swithin’s Day.

As we track the vicissitudes of Emma and Dexter’s personal and professional lives, we feel moments of both profound sympathy and utter exasperation for both characters. Dexter generally comes out worse along the way, as he is more easily inclined towards entitlement, narcissism, and selfishness (although generally managing to be an engaging and loveable character at the same time – at least to Emma).

One of Dexter’s lowest ebbs takes place in an expensive London restaurant when both characters are in their mid-20s. Dexter’s career as a TV presenter is going well and he has started to enjoy the lavish lifestyle of a minor celebrity. Emma, meanwhile, is teaching in an inner-city comprehensive and is cash strapped.

During their lunch date, Emma finds Dexter’s behaviour obnoxious and arrogant; his recent success has gone to his head, as have the alcohol and drugs that have become his crutch. He tells Emma that her chosen career path is dull and uninspiring. He (unknowingly) quotes George Bernard Shaw by saying to her: ‘You know what they say…those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.’

At this, the feisty Emma pushes the table on to Dexter in horror, spilling the expensive food and drink all over his trendy clothes, and she storms out, shortly before declaring to him that their friendship is over (at least for the time being…).

Bravo, Emma!

The irony of Dexter’s remark is not lost on the audience. His unkind comment cannot hide the fact that it is in fact his own life that is spiralling out of control. He is keenly aware of the vacuous, shallow nature of his own work but reacts angrily – and possibly with

jealousy – at seeing his best friend, Emma, succeeding in a rewarding and challenging role.

Like many teachers, I delayed my own entry into teaching because I was keen to try other things before committing myself back to school. But I have no regrets. My experiences in a range of different schools – and now in Downe House – have proved far more rewarding that the jobs I had before I entered the profession.

In fact, I now enjoy advocating for the profession, and I believe that many people underestimate the rewards and perks of a career in teaching.

That is why on Tuesday 19 March we held an event at Downe House in partnership with Bradfield College and a local comprehensive school, The Downs School, to promote teaching as a career. Our three schools are more fortunate than many in terms of the field of candidates for vacancies, but we are not complacent: we feel the need to champion our profession and build an awareness in our region for the opportunities we provide.

The event was a great success, generating lots of thoughtful and excited discussion about all that a career in teaching can offer. We look forward to hosting a similar event in the future.

Cold Calling: The #1 strategy for inclusive classrooms – remote and in person –Tom Sherrington

In this blog Tom Sherrington explores the power and benefit of the questioning routine.

Leadership | What Do Expert Teachers Know, Do and Need? – Kat Howard

Rob and Elizabeth Bjork: ‘Making Things Hard on Yourself, But In a Good Way: Creating Desirable Difficulties to Enhance Learning’ (2011).

Macaro, E. (2005). Codeswitching in the L2 Classroom: A Communication and Learning Strategy. Educational Linguistics, pp.63–84.

In this blog post, Kat Howard considers what makes leadership within schools effective. This much I know about…inclusive, engaging teaching –John Tomsett

In this blog post, John Tomsett explores the importance of creating an inclusive and engaging classroom, but, just as importantly, how to do it.

The Learning Rainforest: Great Teaching in Real Classrooms –Tom Sherrington This book captures different elements of our understanding and experience of the art and science of teaching. It’s packed with strategies for making great teaching attainable in the context of real schools.

Nick Soderstrom: ‘Learning Vs Performance: A Distinction Every Educator Should Know’ (2019).

John Dunlovsky: ‘Strengthening the Student Toolbox: Study Strategies to Boost Learning’ (2013).

Tom Sherrington: post ‘10 Techniques for Retrieval Practice’ (2019).

Henry Roediger: ‘Test Enhanced Learning’ (2006).

David Didau: ‘Deliberately Difficult: Focusing on Learning Rather than Progress’ (2013).

Krashen, S.D. (1981). Second Language Acquisition and Second Language Learning. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Swain, M. and Lapkin, S. (2000). Task-based second language learning: the uses of the first language. Language Teaching Research, 4(3), pp.251–274.

Yang, M., Cooc, N. and Sheng, L. (2017). An Investigation of CrossLinguistic Transfer Between Chinese and English: a MetaAnalysis. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second Foreign Language Teaching 2(15).

Sherrington, Tom. “The Learning Rainforest.” Sherrington, Tom. John Catt Educational Ltd, 2017. Tom Sherrington, Oliver Caviglioli. Teaching Walkthrus Five-Step Guides to Instructional Coaching. John Catt, 2020.