EXPEDITION NORTHEAST

Justin Barbour’s Historic Journey

A Quest for Discovery

Uncovering Shackleton’s Lost Vessel

Tim Collins photo INTO THE WILD

Editor-in-chief

Dillon Collins

Assistant Editor

Nicola Ryan

Art Director

Vince Marsh

Marketing Director

Tiffany Brett

Publisher and CEO

Grant Young

President and

Associate Publisher

Todd Goodyear

Distribution and Subscription Representative

Marlena Grant

Advertising Sales

Account Manager

Ashley O’Keefe

General Manager and Assistant Publisher

Tina Bromley

To subscribe, renew or change address use the contact information above.

Canada Post Canadian Publications Mail Sales Product Agreement #40062919

The advertiser agrees that the publisher shall not be liable for damages arising out of errors in advertisements beyond the amount paid for the space actually occupied by the portion of the advertisement in which the error occurred, whether such error is due to the negligence of the servants or otherwise, and there shall be no liability beyond the amount of such advertisement. Pen names and anonymous letters will not be published. The publisher reserves the right to edit, revise, classify, or reject any advertisement or letter.

© 2024 Downhome Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission of the publisher.

Printed in Canada

Survival. It’s one of our basic human instincts.

The tireless pursuit of food, water and shelter are primal, hard-wired intangibles programmed deep down in our special somewhere. We all hope that, when push comes to shove, we’ll have that intestinal fortitude and sandpaper grit to push through pain both real and imagined, to persevere through hell or high water. As with nature, not all are up to the task, particularly when it comes to navigating rough and rugged terrain. To that end, we proudly highlight stories of survival in its many forms. Justin Barbour’s gruelling year-plus trek through the wilderness, Bernie Howgate’s decades-old Big Land odyssey and the newly discovered vessel with ties to legendary explorer Ernest Shackleton exemplify our collective inner strength, while Sheila Cooper’s tribute to her son and Dave Paddon and Lester Green’s ode to their fathers are testament to the human spirit. From adventurers and navigators pushing the boundaries of human limitations, to those brave souls who find the will to rise and rebuild following a great loss or tragedy, titanium guts and overflowing hearts are proudly on display in this issue of Inside Labrador.

Dillon Collins Editor-in-chief dillon@downhomelife.com

Everyone has a tale to tell. And we want to see your stories about Labrador. Maybe it’s a recollection of the way things used to be, a historical piece, or a story about somebody doing great things in your community. Maybe it’s a travel story about a trip somewhere in the Big Land. Whatever your story, in verse or in prose, our readers would love to see it and so would we.

If you’re better with a camera than a keyboard, you’re in luck, too - we’re also looking for photos of Labrador. From snapshots while berry picking to compositional studies of the landscape and everything in between, we love looking at your images.

Published submissions will receive $20 in Downhome certificates to spend in our stores and online at www.shopdownhome.com.

Send your photos and stories to editorial@downhomelife.com or upload them to our website at Downhomelife.com/submit.

Adventurer Justin

reflects on his year-long odyssey through Canada’s wilderness

BY DILLON COLLINS

Barbour

Some folks are just wired differently.

To ask Justin Barbour, explorer, speaker, content creator and all-around go-getter, the Bauline native would likely put himself in that small percentage of those who thrive outside of comfortable boxes.

Perhaps that’s putting it mildly when isolation, brutal weather and threats ranging from rugged terrain, animal life and well-acquired exhaustion are your ideas of a good time.

Justin’s most recent, and indeed daunting task –dutifully titled Expedition Northeast – saw the author and adventurer set out from Puvirnituq, Quebec, along the northeastern shores of Hudson Bay in July of 2023, beginning an arduous journey through remote Quebec, Labrador and Newfoundland, the longest solo journey ever attempted through northeastern Canada. He’d finish the saga some 372 days and 3900 km later, marching out of the fog at Cape Pine Lighthouse on July 22nd, 2024, bookending the most physically and mentally demanding trek of his life.

“You’re just worried about survival, really, looking after yourself. And it boils down to that,” Justin shares during a sitdown with Downhome. “It’s just very focused on the survival aspect, keeping a bit of grub going and keeping on moving and making sure you’ve got a good spot to set up camp and all that good stuff. It’s different. I think about our great grandfathers who were out living that type of lifestyle, and then they came back like myself now and they said, okay, now you got to go on the computer for eight hours a day. They’d take the computer and dropkick it right out in the woods.”

Justin’s trek across Labrador stared in Puvirnituq, Quebec and ended in Cape Pine, Newfoundland.

Above: Justin’s last camp in northern Quebec.

Indeed, reacclimatizing to civilian life following a year-plus in the bush requires some adjustments. Choice, for example, is prevalent where former options were, at best, limited.

“Out there on the trail all year long, it was simple,” Justin explains. “There were only a few things to be concerned about on a day-to-day basis: waking up, breaking camp, setting a daily goal for distance, for example, where I might make it to finding a good campsite, some good water, somewhere to find a bit of food along the way. And that was it. I had the few dozen items either with me in a canoe, on a toboggan or in a backpack, depending on how I was going, or on

the bike for that phase of it. Then I get back and there are a lot more choices around home. You’ve got family and friends and work and there’s emails, the rat race, it’s a different life. So I’m just taking my time to get back to the same pace I had before I left.”

From beginning to end, the genesis of Expedition Northeast was more than six years in the making, the culmination of years worth of pushing both body and mind in increasingly trying circumstances.

“I’ve just been working my way up. I did three months. I mean, that’s a quarter of a year. I did most of the summer and all the fall until freeze up in Labrador back in 2018. When I left

up there in 2018, I had struck ice. You know, winter came really early this particular year. And I said next time winter comes, I want to be ready,” Justin recalls.

“I wanted to spend a full year and be out there with every season as it changed, and of course, cover a long distance and see the whole route. I

and while Justin owes a great deal to his wife Heather, family, friends and partners – especially his devoted travel companion, Cape Shore water dog Saku – he has come to appreciate the subtle art of isolation.

“First and foremost, it’s my choice to go out there and do it. I wouldn’t have done something like that if I

“First and foremost, it’s my choice to go out there and do it. I wouldn’t have done something like that if I wasn’t content with my own company.”

crossed over probably 1% of the route I had been on before, so it was completely new parts of this side of the country. I got to be out for a full year and see the seasons change a lot more intimately.”

It takes a village to raise an explorer,

wasn’t content with my own company,” he shares. “I thrive in my own company. I’m used to spending a lot of time doing some of these earlier trips. I mean, I did them all on my own. I had Saku there and the husky for a lot of them, but this became sort

of a thing. I got into doing these trips around eight or nine years ago, and I started doing them on my own, and they got longer and longer, and I certainly wasn’t signing anyone up once I started to get into three or four weeks plus.”

Make no mistake, the size and scope of the expedition did mean testing those nerves of steel. Justin admits he was often pushed, with lonesome feelings creeping in during the dead of night, though putting his nose to the

grindstone and focusing on the task at hand would keep melancholia at bay.

“The fact of doing it for a full year, I knew I was stepping into new territory. I had no dog for six months of the trip, and that was probably the most difficult part. Having Saku there, you never feel alone. Not for a second. You’re busy just trying to ensure your survival on a day-to-day basis so that there’s not much time (to dwell). Maybe lying in the tent in the evening for an hour before bed I’m thinking to

Above: Justin and Saku navigating Leaf River in Northern Quebec.

Right: Completing the Trans Labrador Highway

myself, jeez, it’d be nice if Heather were here now, just to share the experience more than anything. In the winter when I had no dog, it was a bit of a different beast, but you just keep going, keep moving,” Justin admits.

“My mind did start to get a bit more idle without the dog, but again, there’s always something to do. Get some firewood ready for the next morning or root through the kit, maybe there’s something too heavy and I’m going to burn it in the fire or maybe something got to be repaired, and all evening long I’m looking through the maps, trying to figure out where I’m going the next day.

“So there’s so much to do. Being alone and getting through that stuff was a sacrifice of doing the expedition and getting through those mental challenges is pretty exciting. I’m a bit fascinated with that side of it as well,

being on my own and having to motivate myself constantly to keep that positive mindset and, sometimes motivation is not enough. It’s just discipline and getting up and doing it.”

Justin’s body was taxed as strenuously as his mind across a year-plus through rough and rugged terrain. Encountering creatures ranging from moose, pine marten, musk ox and bear while navigating sub-zero temperatures in the winter and searing heat in the summer, Justin received the full brunt of Mother Nature’s exhaustive push and pull.

“There were a lot of hard moments on the trip. Getting into the winter and the short days was a trying time,” he says, reflectively. “I was following a riverway at this point in time, and it was still early in the winter. So a lot of the rapids and stuff were not frozen up safe enough to go along the shore.

So I’m in the woods and having to beat a trail through, two, three, four feet of soft, powdery snow. And some days I only got 4 or 5 km a day. Knowing that I had thousands of kilometres left, I started to get impatient, but again, just grounding myself. Giving up was never an option.”

This past spring Justin bikepacked 1150 km across the Trans Labrador Highway, averaging 100 km a day when conditions were optimal, sporting roughly 70 lbs of gear through wet and grimy weather that soaked him to the bone.

“I had a $500 bike from Canadian Tire. I wasn’t outfitted for winter with one of these nice, fancy fat bikes that cost five grand. So she was freezing up on me, and I had no one coming behind me. There was no support team. I wasn’t staying in a van every evening. The tent was on the back of the bike. I had a -40 sleeping bag, and I rode the bike as long as I felt like it all day and then I set up camp and tucked myself in the woods some-

where. You’re not getting much traffic on the highway, but I didn’t want to be in the thick of it. So I’d tuck off somewhere, have a little fire, get up and go on again.

“I battled some crappy weather, and a lot of rain, but I just chipped away at it. The bike was different too, because I felt like on the bike there would be lots of gliding. In Labrador City I said jeez, I feel like I’m on a rocket compared to what I was at, walking and canoeing. But I quickly found out that it wasn’t easy.”

Weeks removed from the expedition and faced with the more business end of an operation with content to be made, books to be written and endless footage to splice together, Justin is afforded time to reflect. Big picture, little moments, lasting memories and the trail in his rearview, Justin Barbour has had a chance to wind through roads many of us will never tread.

“Get out and do what you love to do,” he urges. “If you love something

Justin and Heather reunited west of Churchill Falls

enough, you can find a way to make a living at it and make money at it, in this day and age, more than ever. If you love playing Tiddledywinks enough, you can make a living off of that. If you want to go and put videos on YouTube and promote yourself and send emails to people who might be interested and get your foot in the door and provide valuable material to people, you can make a living. That’s my mentality. And this is something I wanted to do, and I’ve always been someone who, if I get an idea in my head, I’m running with it. And that’s it. Get out and get after it. Life’s too short not to.”

Follow Justin Barbour online at NLExplorer88 on X, Newfoundland Explorer - Justin Barbour on Facebook, @nlexplorer88 on Instagram and @JustinBarbournlexplorer on YouTube.

and Saku

896-6916 (fax)

Justin

at Cape Pine Lighthouse

A historic wreck has been discovered off the coast of Labrador

BY NICOLA RYAN

There was no way three strangers could possibly appear from nowhere at the whaling station.

Yet here they were. On May 20, 1916, Ernest Shackleton, Frank Arthur Worsley and Tom Crean, exhausted and freezing, had staggered into isolated Stromness – a whaling station on the northern coast of South Georgia Island in the South Atlantic. In an incredible feat of determination and desperation – a journey so arduous, hearing of it made the Norwegian whalers weep – they had travelled from Elephant Island, more than 1300km away.

The Heroic Age

Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Atlantic Expedition of 1914-1917 is his most famous journey. The crew of the doomed Endurance faced months trapped in pack ice in the Weddell Sea before the ship was crushed and they were stranded on Elephant Island – an ice-covered, mountainous island off the coast of Antarctica. Shackleton’s rescue mission led him and five men on a perilous 16-day voyage across the icy waters of the Southern Ocean in an open lifeboat, followed by a gruelling trek across the mountains and glaciers of South Georgia’s interior. Shackleton eventually returned to the stranded crew, successfully rescuing all 28 men after nearly two years of survival in extreme conditions. It was an incredible feat of humanity and endurance, cementing Shackleton’s place as one of the premier adventurers of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Shackleton intended to return to the Antarctic, and a new venture financed by British businessman John Quiller Rowett was planned for 1921. The Shackleton-Rowett Expedition had just arrived at South Georgia onboard the new ship, Quest, on January 5, 1922, when Shackleton, in his bunk, had a sudden heart attack and died. He was only 47 years old.

Wreck of the Endurance

Ernest Shackleton’s Quest was used as a research vessel, a rescue ship, a naval vessel and as a sealing ship before it sank off the coast of Labrador in 1962.

The Quest

After Shackleton’s death, Quest was acquired by a Norwegian company. It was involved in other important expeditions, including the 1930-31 British Arctic Air Route Expedition led by British explorer Gino Watkins. It was used in Arctic rescues and served in the Royal Canadian Navy during the Second World War before resuming work as a sealing ship. Finally, on May 5, 1962, Quest was damaged by ice and sank off the coast of Labrador. It would rest there, lost and unreachable on the ocean floor, waiting to be rediscovered, for more than 60 years.

The Shackleton Quest Expedition

On June 9, 2024, an international team of marine archaeologists, explorers, and scientists, led by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, discovered the wreck of Quest using sonar equipment operated by experts from Memorial University’s Marine Institute. The discovery coincided with the 150th anniversary of Shackleton’s birth.

“It’s been an exciting time, my goodness,” Rosemary Thompson, Vice President of Communications and Marketing, says over the phone from

the Royal Canadian Geographical Society (RCGS) office in Ottawa, as she details the discovery and the sixyear process of organizing the expedition.

“The president of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society [The Hon. Lois Mitchell], reached out to Dr. Paul Brett at Memorial University’s Marine Institute to say ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting if we could find this?’ And Paul was very supportive and that’s how it got started. So Memorial was very much one of the most important partners in getting this thing together,” she explains.

Quest sank in the water off of Mi’Kmaq, Innu and Inuit territories, so the RCGS also partnered with the Miawpukek First Nation and their shipping company, Miawpukek Horizon.

“We worked with Chief Mi’sel Joe and they were very much part of the

planning process to get things going. Another person who was very important was Meagan Murphy from Leeway Odyssey, she helped so much in the planning phases to get the small ship out there to find the wreck,” Rosemary says.

The expedition, led by the RCGS Chief Executive Officer John Geiger also included Jan Chojecki, grandson of John Quiller Rowett, and Norwegian Tore Topp whose family owned Quest from 1923 to 1962. Before setting out, Search Director David Mearns and the team of researchers led by Antoine Normandin meticulously analysed historic logs, maps, and environmental data, combining it with modern technology to estimate the ship’s location.

After 17 hours of searching, researchers identified a potential match for the wreck located at a depth

A side-scan sonar image shows the wreck of Quest lying upright and intact on the seabed at a depth of 390 metres.

of 390 metres in the Labrador Sea, near Battle Harbour. They conducted multiple sonar scans from various angles to verify their findings. These repeated passes, four in total, allowed them to capture detailed images of the site and accurately measure the wreck’s dimensions to confirm a match with high confidence, leading

them to conclude that the wreck is indeed that of Shackleton’s final vessel.

“It was an amazing, amazing thing,” Rosemary says. “It was not easy, none of it was easy. But they did a lot of research and they did their homework and because of that, once everything got underway, they found it really

Antoine Normandin, David Mearns and Tore Topp examine sonar imagery of the wreck on Mearns’ phone.

Jill Heinerth/Can Geo photo

Can

Geo photo

The 2024 Shackleton Quest Expedition team poses with the flag of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society on the deck of LeeWay Odyssey the morning after the find. Standing, left to right: Geir Kløver, Derek Lee, Jan Chojecki, John Geiger, Tore Topp, Katherine Smalley, Mark Pathy, Craig Bulger. Kneeling, left to right: Sarah Walsh, Martin Brooks, Antoine Normandin, David Mearns, Jill Heinerth, Alexandra Pope.

quite quickly, which is amazing. The research was really, really well done.”

The discovery of the vessel, upright and intact on the seabed, represents the last major part of the puzzle in assembling Shackleton’s physical legacy.

“So now the big question is can they go out again and use ROVs [remotely operated vehicles] to get better imaging. That’s something that’s under discussion right now,” Rosemary says.

“We want to protect it. It’s part of our marine history and it’s an important historical and archaeological artefact. So our hope is that we can go back to get really fine imagery. We’d like to have an exhibition and a book and potentially a documentary that would be made so that people can

learn more and more about this amazing figure – Ernest Shackleton –and also about this amazing ship because it had a long life in the cold waters off of Canada. These ships can tell us a lot about our own history and how we developed as a country.”

The successful discovery of the Quest stands as a testament to the extraordinary teamwork and dedication of the international expedition team, whose combined skills and determination made this historic find possible. It’s an achievement that celebrates Shackleton’s enduring legacy, deepens our appreciation of polar exploration, and highlights Newfoundland and Labrador as a leader in ocean research.

Jill Heinerth/Can

Geo photo

BY LESTER GREEN

Author’s Note: The following excerpt was a story I recorded when I took a Newfoundland Folklore course at Memorial University in 1978. I interviewed Dad, William Green, about his many voyages, and this was his recollection of his first voyage:

Around the middle of April 1935, I made my first voyage to Labrador. We loaded R.A. Squires, father’s schooner, with birch junks, wooden stakes, splits, barrel hoops, lumber and a few barrels of herring we caught in the first part of the winter. We shipped this to St. John’s to sell for grub for Mom and them ‘cause they couldn’t get any when we were gone to Labrador.

Father, me, Wallace, and I think it was George went to St. John’s, and the rest of the crew stayed to get the fishing gear ready.

When we got to St. John’s, we would tie up at Baine Johnston’s wharf, and we sold the stuff and bought grub for Mom and them. Father would get credit for gas, tar for barking the trap, about 160 hogheads of salt and grub for the boat. We loaded the boat with freight like flour, cans of food, things for stores, and items people asked us to get like a stove, chairs, and other stuff. When we returned, these things were dropped off at Little Heart’s Ease, Southport, Gooseberry Cove and St. Jones Without.

In early June, we loaded the gear aboard the R.A. Squires for the voyage to Labrador. The gear was a trap skiff, two punts, three codtraps, seven to ten lines of trawl and a salmon net to catch a few salmon to eat. The skiff was 28 feet long and had a five Acadia in her.

We left home on Thursday, 18th of June, with Dad, me and Wallace aboard. We stopped off Gooseberry Cove to pick up John Robert Spurrell, Uncle Dickie Seward, Edward Spurrell, and George Smith. Off Trin-

Lester’s father and skipper of the R.A. Squires, William Green

ity, it was some foggy, and someone yelled, “Sure, we got no tea!”

We pulled the jib down and hauled up the skiff. Uncle Dickie and Wallace jumped aboard and went ashore in Trinity to get the tea. We had to keep blowing the horn so they could fix a course to come towards us.

When they got aboard, we hoisted the jib and set the course for Catalina. The fog lightened, and we saw a schooner off the bow. Dad said, “Sure,

that’s Uncle Moses Martin from Little Heart’s Ease, and we should follow him into the run and go across Bonavista Bay.”

We got down to St. Anthony just before dark and anchored in the harbour for the night. We spent a few days in St. Anthony. Dad met his old buddy, Uncle Stevey White, from New

We stopped at places like Hawke Harbour and Huntingdon Shore, and finally, we anchored at Snack Cove. We took out the traps and found out about the berths from settlers and Uncle Stevey. About a week after, there was some storm from the Northeast. After the storm, we helped Uncle Stevey get his trap off the bottom. We

Perlican. Dad said we’ll go down to Labrador with Uncle Stevey and fish near him.

The next day we left, and off Quirpon there was some mess of schooners. I’d say 30 or 40 from Conception Bay, Trinity Bay, Bonavista Bay and some from around the Cape. We crossed the straits, schooners raced past each other, and others passed them. The schooners all split up on the coast of Labrador. Some landed Planters and their gear. Others found a place for trap berths.

tore the bottom of the trap to get it free from the rocks.

The collector boat came down and told us there were lots of fish in Packs Harbour. So we got the traps aboard, took the 260 quintals and headed for Packs Harbour. There were two schooners at Packs Harbour when we got the traps in the water. Uncle Stevey fixed his trap and put it out. There was no fish the first couple of days. The two schooners that were there left. After that boy, was there ever fish!

We’d haul the trap, load the skiff, and put the rest in a codbag. We brought the skiff load to the schooner and got something to eat while the cook would prong up the fish. After a quick lunch, we’d go up on deck and clear away the fish. Dad was a splitter, Wallace was the header, and I was a cut-throat. John Roberts was the salter. Edward and George were the rousers. They would dip the fish out of the tub and throw it down in the hole to the salter. We didn’t have a cook, but Uncle Dickie did most of the cooking.

Sure, sometimes it would be dark by the time you were finished, so we’d put the kerosene lamp over the splitting table. Sometimes we would rig a torch, and by the time you were fin-

ished your face would be black as ink. We finished the load around 12:00 or 1:00 in the morning and grabbed a quick nap because we’d go out around 4:00 am or 5:00 am to haul the trap again.

Coming back from Labrador, she would be a strake clear of the water’s edge. We’d have about 700 quintals of salt fish and about six casts of cod liver oil aboard. We dropped the boys off at Gooseberry Cove and headed home. It was around the middle of August. The boys would come up later to help us take the gear off the schooner. Around September, we get ready to dry the fish. The schooner would get half the voyage and the crew the other half. Dad, Wallace and my share were included in the crew

The R.A. Squires docked in St. Jones Without

share. Our share was left at St. Jones, and the crew’s share was given to them to dry. If it spoiled their share, they would get nothing. The boat share was given to people from Gooseberry Cove, Butter Cove, Southport and Little Heart’s Ease to dry. We’d give the people so much a quintal, but most of the time, they wouldn’t take money but wanted to get something in St. John’s, perhaps a jacket, pair of pants, or pair of rubber boots.

Around October, Dad would go down to people who had the fish to dry. If the fish were to his liking, we’d come down, and with the rest of the crew, we’d collect the dry fish and put it in the hole. When we’d get it all aboard, the schooner headed to St. John’s.

We would beat in the narrows and tie up at Baine Johnston wharf. The next morning, Wallace went up to the office, and when he came down, we’d start culling the fish. The weighmaster would keep track of the weight, but we kept count of the barrows, and each barrow would have a draft of about two quintals of fish. We paid Baine Johnston a payment on the boat and the supplies we had there in the spring. What was left was shared among Dad, me, and Wallace.

We’d go shopping then with Mom and Melita to buy food and clothes for the winter. The stores we’d go to were the Big Six, Harris & Hiscocks, Lon-

don, Ayre’s and others, but I can’t remember the names. When we were ready to go, we’d take the freight down to the wharf and load it aboard. Getting out of St. John’s in the fall was hard, but we set sail when we got our chance.

When we get back home we carried the freight to the people that sent out by us. Then we’d come back and moor the schooner up in Ferry’s Cove under full force for the winter by carrying two anchors ashore and having two more on the bow. We carried two more span lines ashore in the cove. The lines kept the schooner from swinging in the winds. After she was moored, we’d take down the riggings and build up a place in the hole for the canvas. Then she was left for the winter.

Book Review

What Can You See (From A-Z) Under the Labrador Sea

By K. Erin Snow REVIEWED BY DENISE FLINT

What Can You See (From A-Z) Under the Labrador Sea is an alphabet book from first-time author K. Erin Snow that’s both charming and unique. Each letter of the alphabet is given a single word that relates to something on or near Snow’s ancestral home on Spotted Island in Labrador (not just under the sea but upon it and beside it). It’s a lovely concept and if that weren’t enough the English word chosen for each letter is then accompanied by the Inuktitut name. So the reader learns that, for example, the Inuktitut name for iceberg is pikalujak and anchor is kisak. What a terrific idea. Even some of the English words are culturally unique – winkle becomes wrinkle and grampus becomes grumpus, in the dialect of this part of Labrador at least.

Books for children can be made or broken on the strength of their illustrations. The illustrations by Dayla Williams are absolutely delightful, simple, lively and beautifully coloured in a way that brings a degree of joyfulness to the book.

Unfortunately, there were several typos and other problems with the writing in the book and its flimsy construction means it probably won’t be able to withstand multiple readings. A pronunciation guide would have been helpful as would a title page. Even so, What Can You See (From A-Z) Under the Labrador Sea is both fun and educational. Children and the ones who read this book to them should have a great time with it.

Q&A With the Author

Denise Flint: Tell us a bit about yourself.

K. Erin Snow: I’m an Indigenous woman from Labrador with roots in both Newfoundland and Labrador. I’m a mother of one son, a wife and a new author. I did a two-year Indigenous studies program at MUN, then found my passion for wanting to help Indigenous people and Indigenous communities. In 2018 I took a leave from my government job and that’s when I really understood my own culture, and why things are the way they are. It was a kind of ‘ah ha’ moment.

I found there weren’t many options to learn about our own Indigenous culture in Newfoundland. I decided to start a Labrador consulting service to offer cultural awareness of Indigenous learning within our own province. There has been some interest, but it’s still under development. There’s a need for learning within certain sectors of government, so I’m hoping with this book I’ve created specifically to provide cultural awareness of my homestead on the southern coast, that there’ll be more opportunities to have my book into the Department of Education and the school system and incorporate Indigenous knowledge at the learning level.

DF: Where did you find your team to produce this book?

KES: I ended up reaching out to a young girl [an artist] who was dating someone from my island. She was visiting the island with her boyfriend and I knew I wanted to work with someone who could visualize it when I was saying it.

The translator I knew from when I took some basic Inuktitut sessions and she was one of the instructors online during COVID. She was visiting St. John’s and I saw her outside a local store and I had a conversation with her and asked if she would be interested in doing the translations.

DF: Why does this book matter?

KES: It matters because it keeps culture alive, it keeps cultural language alive and it touches on truth and reconciliation. I dedicated the book to my father, who is a residential school survivor, and I think it’s important to keep joy in our culture when sometimes there’s not joyful memories.

DF: How did you pick the words you used and why were some translations left out?

KES: I picked the words based on what I see in my culture and what I saw growing up on Spotted Island and I picked them based on making them educational but informative. I wanted what’s in the sea and also what’s by the sea mixed in. Some of the words were selected because they were important to me and reminded me of my heritage and upbringing. Some words I did ask for opinions on, including the word lumpfish which my dad picked because it’s the coolest fish in the sea. Some of the words were not translated because the translator didn’t have those words in her experience. Inuktitut has different dialects and if my translator said there’s no word for that it was not included. Every language is different. That there’s no word for it is part of the culture.

The Great Outdoors Visiting Lab West

One of two Great Blue Herons dropping by Labrador West on a beautiful morning. TIM COLLINS Labrador City, NL

Scenes from L’Anse au Loup

ROSEANN LINSTEAD L’Anse au Loup, NL

Hopedale View

View overlooking the airstrip looking out the cove.

STEPHEN COLBOURNE Hopedale, NL

The Beauty of Labrador

Wagz stops for a rest with the perfect backdrop behind her.

DEANNE HUSSEY Labrador City, NL

Central Labrador’s Sheila Cooper has created Jon’s Place, a haven for those battling addictions in memory of her late son.

BY HEIDI ATTER

Along the quiet stretch

of highway between Happy ValleyGoose Bay and North West River in central Labrador, stands a new sign. In large letters, it welcomes people to ‘Jon’s Place.’

Flower pots line the entrance, with walkways leading to a pond with a small flowing waterfall. Colourful offices surround the area with chairs on the office deck. Sheila Cooper has been working to build a space like this for years. She looks around it with pride, surrounded by her brother and sister, cousins, children and nephews. “It’s like your own little piece of heaven,” Sheila says.

The campground includes rental cabins, fully-serviced campsites for RVs, and unserviced campsites for tents.

Jon’s Place is named in memory of Sheila’s son, honouring him and others who lost their lives after battling addictions.

Left: Sheila Cooper and her son Jeremiah beside their waterfall pond near the entrance of Jon’s Place.

Sheila Cooper lost her son to fentanyl poisoning in 2022. The Labrador woman has turned her grief into action creating a place in memory of her son where people can rest and reconnect.

Jon Cooper was 36 years old when he attended a concert in Alberta. He purchased a gram of cocaine, without knowing it was laced with fentanyl. He died in 2022. Jon was a husband, tattoo artist and world traveller.

A photograph of him and others who have died following battles with addictions stands at the entrance of the park, with large letters reading ‘Wish You Were Here.’

“Jon was amazing, nice, worked hard, all around good guy,” Sheila explains. “He was an adventure seeker. He did deep sea diving, diving with sharks, snowboarding, anything that had a bit of adventure in it, he was game.”

Since his death, Sheila has become a vocal advocate for awareness surrounding addiction. She created a non-profit called Jon’s Afterlife Com-

munity Outreach, which provides safe-using supplies and is a judgement-free contact connecting people to food banks and women’s shelters, lending a hand to anyone in need.

“We’re handy for being like a middle person for people who don’t know where to reach out,” Sheila shares.

She hopes to expand the non-profit to include youth events and provide a supportive environment so young people don’t turn to drugs and alcohol as they age.

While she helps people in her community of North West River and nearby Happy Valley-Goose Bay who do use drugs, Sheila says the campground is a zero-tolerance area for drug use and will not allow anyone to use substances while staying on the land. She explains that is out of respect for her son and the others who

Jon Cooper died of fentanyl poisoning in 2022. Now a photograph of him and others who died after battles with addictions hangs at the front of Jon’s Place, with a sign reading ‘Wish You Were Here.’

have lost their lives, adding that the campground is meant to be a safe, healing place and family-friendly.

She hopes it may grow into a place where people and families can spend time, rebuild relationships and work to heal and stay clean together.

“It’s like constant camping and you have all the amenities,” Sheila says. “It’s peaceful and calming.”

After becoming clean, parents are often permitted supervised visitation with their children in care to begin to rebuild relationships. Sheila explains that these visits could take place at the campground, giving parents and chil-

dren a neutral place to start fresh.

“Bring them down,” Sheila urges. “I think they would love it and not only that, I think it gives the parents and kids time to be together. There’s no outside distractions.”

Parents don’t need to worry about navigating a social worker’s schedule, Sheila shares, as she has been a foster parent for decades and can supervise on behalf of child protective services.

“A chance to start over, right? For both of them,” she says warmly.

The healing space has been years in the making. It was formerly called Goose River Lodges and was started

Sheila Cooper dreams of a place where families can reconnect, recharge, and heal together in central Labrador.

by a couple who built it from the ground up. After they passed away, it went to their son. Sheila says she could envision the sign at the entrance and reached out to him to buy the property. “Getting (Jon’s) name up on that board was a big deal for us. And getting to see it there finally was amazing,” she shares. “It seems like it’s falling together.”

Jon’s Place has been a labour of love for the entire family. Sheila’s brother, sister, and nephews, to name a few, have all pitched in, especially her nephew Isiah Cooper Crane, who lost a brother to fentanyl use. They aimed to name a cabin after Isiah’s brother, but the two weren’t sure which one to pick. While replacing plumbing in Cabin 8, something caught Isiah’s eye. ‘Crane’ was written in magic marker on the tub. She says the two of them knew that was the cabin meant to be named in his memory.

Sheila has been working to speak with families, receiving permission to name the cabins after those who have died through addiction. She hopes

that people can remember the whole person, not just their struggle.

“I find like they’re doing me a favour,” Sheila says of the families granting permission. “Maybe it’s part of my healing too.”

Being on the land has been a way for Sheila to stay busy, keeping her mind occupied instead of dwelling on negative thoughts. “Nature is the healer of all healers, that’s how it is with any issue you have,” she says, reflectively. “The serenity that you will get from being in the wilderness will cover you.”

Sheila explains that, especially for Indigenous peoples, it’s important to sit and consider that this is where their grandmother and great-grandfather walked, the lands their ancestors lived on and thrived on.

She hopes to have Jon’s Place up and running this winter, with the dream of year-round availablity, given its proximity to the Birch Brook Cross Country Ski Club and a local church working to restart the local downhill ski hill. She says they can support anyone

new to winter camping and even set up a traditional Labrador tent for a unique experience.

“There’s not much to it. It’s good fun,” she says with a smile.

Sheila has large dreams of what the eight acres may grow into over the next five years. She hopes to eventually install hot tubs, a swimming pool and even a pump track for children to use balance bikes, a go-kart track, and more hiking trails and paths.

“There’s so much potential here,” Sheila says. “It’s limitless.”

If Jon were still around, Sheila has no doubt he would be right there helping build it. “I think he would love it,” she says proudly. “He would definitely be here.”

For more information contact Jon’s Place at 709-899-6060

Sheila (centre) and her brothers, cousins, nephews and sons have been working during the summer and fall to get Jon’s Place up and running. The group hopes to start accepting reservations for cabins or tent rentals this winter.

Downhome History

Amanda Buckle photo

BERNIE HOWGATE Downhome • July 1994

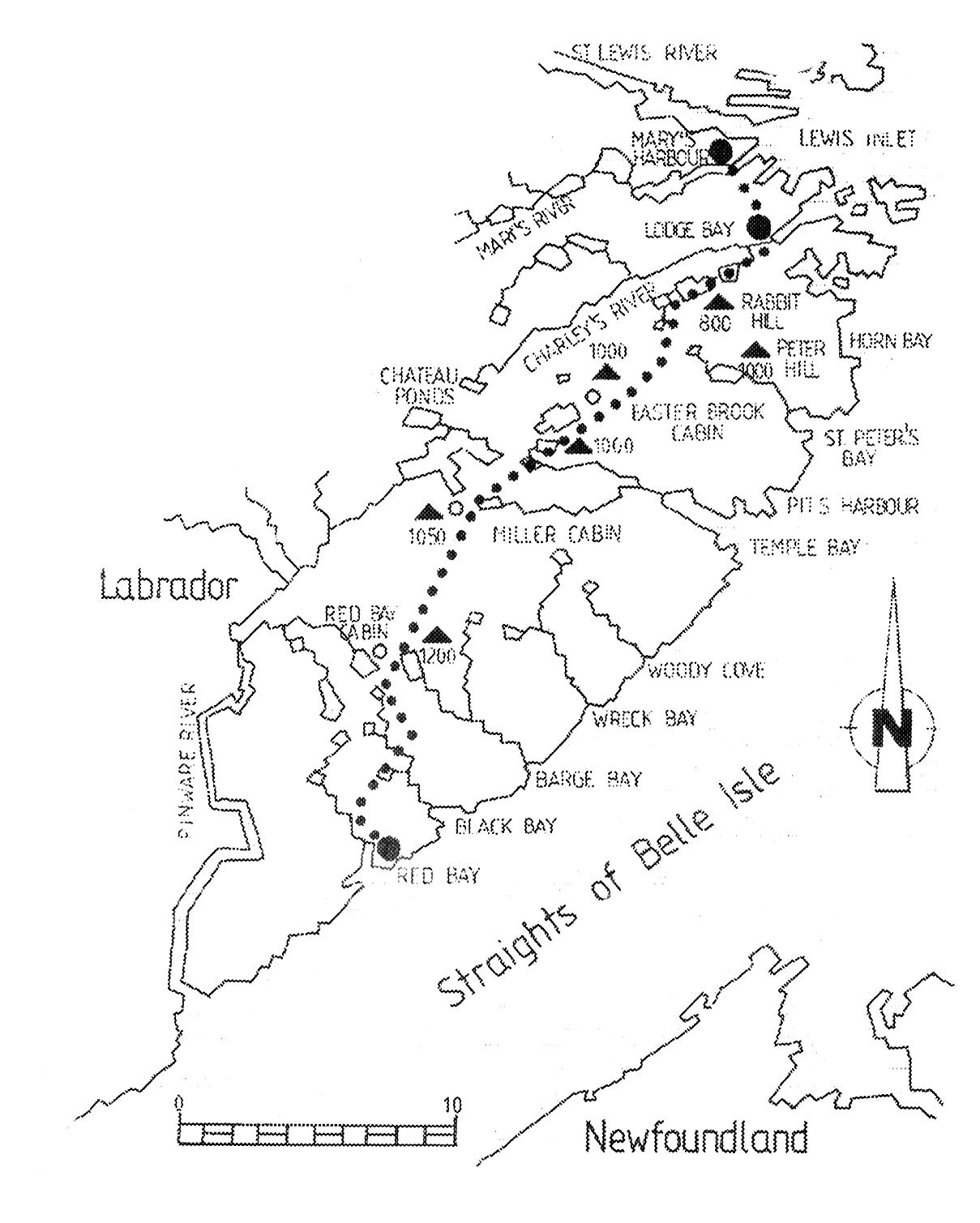

In this flashback through our Downhome archives, our July 1994 issue published the second of 14 episodes from author and adventurer Bernie Howgate from his eight-month, 4,000kilometre solo trip up the Labrador coastline. The first part of the journey was on foot dragging a sled in the dead of winter. The second part was by kayak during the summer. This is the second excerpt from his journey through Labrador:

Feb 1, 1992: The good news is I made it to Red Bay. The bad news is I haven’t moved in the last three days. For four nights I’ve been snowbound in an emergency shelter en route to Mary’s Harbour. Every morning I’ve woken at 6 a.m., turned to the CBC weather forecast, heard the blizzard warning, then buried myself deep back into my sleeping bag. I’m now on Labrador time. My pace is now governed by nature, not time schedules.

A map of the Red Bay leg of Bernie’s Labrador journey, originally published in July 1994’s Downhome

Seven days ago I woke to the sweet smell of frying bacon. Outside the scene was a blanket of snow. There’s something about winter that brings life and symmetry to the north, and Red Bay was no different. My months of planning had paid off. A family who had never even heard of me until a week before had welcomed me with open arms.

Red Bay is literally the end of the road and my start off point for my winter trek to Goose Bay. Nestled in a natural deepwater harbour at the end of the Belle Isle Straits, this once great whaling port has dwindled to a scattered community of 100 families.

My first morning brought with it a few surprises. News

travels fast out here. I was an instant celebrity. “Are you the walking man?” I had a new title.

Having just come from the melting pot of Toronto it was strange at first meeting people who nearly all looked the same, and also whose dialects were hard to follow. Words overlapped. Sentences seemed to hang in the air, waver back like rubber bands. The same questions followed me at every turn. “Why walk? See a doctor lately? Come to find yourself, have we?” but the concourse was if I lived to cross the dangerous ‘barrens’ to see Mary’s Harbour, then I’d arrived.

The cold at first was deceptive. Under a clear sky the slightest breeze bites into your skin, knuckles crack and bones ache. The crisp morning snow that crunched underfoot would by nightfall, sing back to you. Stars were that clear you felt you could

reach up and touch them and the northern lights hidden by city hazes in Labrador rush over the horizon towards you.

All day and night there was constant motion, skidoos everywhere. Traplines needed tending, wood chopped and collected, but most of all the prime use was to visit. That visible interaction behind closed doors that binds communities together. A steady stream of people arrived at our doorstep to meet the new visitor. Maps were poured over, routes checked. My fibreglass shed damaged in transit was repaired and the inevitable open-ended invitation, “When you’re in Cartwright, drop in on my brother?”

On my last night, I was invited to a potluck supper. The venue was the community centre. Each family was to bring some food, and by the time we

got there, tables were full to overflowing. There was moose stew, chicken pie, brazed duck and every conceivable bakeapple pie variation you could think of. There wasn’t a spice to be tasted. Here was good wholesome food made by people with simple tastes, but warm hearts.

The tables were set in two straight lines. Men at one side, women at the other. The vicar said grace, then it was onto the serious business of eating, and that night many a tall story was stretched to the limit.

Now I’m my own man. Outside the blizzard is still blowing. I’ve just stoked up the fire. Soon it will be time to slip back into my sleeping bag before the temperature drops. Maybe tomorrow the weather will be clear. Next stop is the ‘barrens’ and Mary’s Harbour.

Lunchtime walks under a wide open sky. CONNIE BOLAND Nain, NL

Labrador Voices

BY JEANETTE RUSSELL

The MV Island Lady was lost at sea on the final day of the commercial cod fishery near Battle Harbour, Labrador on September 17, 2021, claiming the lives of my son, Marc Russell, and his crew member, Joey Jenkins. The loss of the Island Lady is more than a profound personal tragedy – it exposed a gravely deficient marine safety net illustrating critical gaps in the provision of primary search and rescue resources in Labrador.

The current distribution of primary search and rescue resources in Newfoundland and Labrador fails to offer fish harvesters and marine seafarers in Labrador the benchmark of safety afforded to their island counterparts, furthermore, it fails to meet the national standards available in other regions of Canada. An investment of federal funding is required to ensure all fish harvesters in Newfoundland and Labrador receive an equal measure of protection affording maximum workplace security and environmental protection.

Top left: Marc Russell, and his crew member, Joey Jenkins

The installation of primary lifeboat stations in Labrador is essential to equally protect all fish harvesters, regardless of where they work in the province.

The current distribution of search and rescue resources in the province illustrates an unbalanced and inequitable investment of federal funding. Newfoundland is equipped with seven search and rescue lifeboat stations, plus three inshore rescue boat stations, while Labrador has no primary search and rescue resources. Importantly, one-third of the lifeboat stations in Newfoundland were installed since 2015 under funding from the Ocean Protection Plan, however, no comparable resources were funded in Labrador during this same period.

On the island, federal funding has established two year-round lifeboat stations in Burin and Burgeo; five seasonal lifeboat stations in St. Anthony, Port au Choix, Lark Harbour, Twillingate, and Old Perlican, plus three seasonally operated Inshore Rescue Boat stations in Bonavista Bay, Conception Bay, and Notre Dame Bay.

This distribution of resources, favouring Newfoundland, defies logic and begs the question: Where is the comparable federal investment to secure primary search and rescue resources for Labrador?

Since 2021, extra attention and lobbying efforts have elevated the issue of marine safety and the provision of

A map of search and rescue resources in the province clearly shows the absence of such facilities in Labrador.

It is time for the Canadian Coast Guard to invest in primary lifeboat stations in Labrador to enhance search and rescue capacity, improve overall maritime search and rescue delivery, and rectify the provincial inequity in the funding and distribution of primary search and rescue assets.

primary search and rescue in Labrador. Federal investments have been secured under the Volunteer Community Boat Program and First Nations Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary, however, these efforts, while an essential start, are insufficient to afford a comparable measure of protection to Labrador.

It is time for the Canadian Coast Guard to invest in primary lifeboat stations in Labrador to enhance

search and rescue capacity, improve overall maritime search and rescue delivery, and rectify the provincial inequity in the funding and distribution of primary search and rescue assets.

Just as the ocean shapes the coastline, search and rescue delivery must also transform to deliver maximum protection to all fish harvesters and seafarers in Newfoundland AND Labrador.

Labrador Voices

BY CAROLYN ROMPKEY

We came to North West River, Labrador in 1963 – Bill as the principal of the Yale School, and I taught grades 5 and 6. The school was built with money raised by Yale University students, who had heard of North West River through the Grenfell Mission and had come to help build it. Bill and I had both gone to schools in St. John’s which were run on the British system, as was Yale, because the province had not yet joined Canada. That made it very easy to fit into the system in place. What a pleasure to find a school in a small community that had been run in a way that we were used to.

As winter came we discovered that we had two very good hockey teams, which Bill and some of the senior boys coached. They competed with Happy Valley and Robert Leckie School (the Canadian base school). We had a rink behind our school, which was very fortunate, but of course, it had to be maintained. Shoveling the snow and clearing the rink was no problem. When that needed to be done, Bill would go to the different classrooms and ask the older children to bring back

shovels after lunch, and they would clear the ice, then it had to be flooded. The teachers and older students took on this task, and some of the fathers as well. Enter Cyril Michelin, father of hockey-playing sons, and very inventive and clever. He got a komatik, turned an empty drum on its side and attached it to the komatik. After poking holes in one end of the drum, he attached a tarp to it and trailed the end of it so it touched the ice. The “Zamboni” was dragged to the River and filled with water. The two ropes attached to the komatik were used to drag it around the rink. The Michelin Zamboni was born.

Our school and town teams did very well. We were a small community, but naturally very good at sports. Just getting our teams to Happy Valley-Goose Bay was an adventure. From North West River we sent everyone across the river by cable car because there was no bridge yet. Next, we met up with Sid Blake, or Harold Blake, who would taxi the team to the Goose River. When the Goose River was not frozen, there was always a boat moored at the river’s edge to take teams across.

In winter, when it was frozen we drove across Goose River. There we were met by a school bus from Robert Leckie school, which took the team to the arena where the game was to be played. Then, of course, we would reverse the procedure to get home. I

will add that the hockey teams needed uniforms, so where to find the money? It was decided that when the redberries were ripe in the fall, the students would go to North West Point and pick the berries. The Hudson Bay store promised to buy some, as well as residents. Well, it was a tremendous success, and we had more than enough money to buy the uniforms.

I am proud to say that we held our own, and won more often than not. Bill decided that we should have a “Hockey Night in Labrador”. Hank Schouse generously said he would sponsor it. It would be a dinner, there would be trophies, and fathers would accompany their sons. Some local fathers became “fathers for a night” to the boys from the Dorm. It was a great success.

I had been a physical education teacher before coming to Labrador and I enjoyed doing as many things with the children as I could without a gym. I decided that the women should not be left out. We formed a ladies’ broomball team, which played at night and had a wonderful time. One night, I even froze my nose, which prompted us all to knit nose warmers. The rink provided no end of fun and skating pleasure for our community. It was well used, well cared for and well enjoyed. This is just one of the wonderful memories of our time in North West River, Labrador.

A tragedy leads to silver linings for one Labrador community

BY DAVE PADDON

In the spring of 1945

my father, Dr. Tony Paddon, was just back from his war service in the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve. He had spent the entire time at sea as a Surgeon Lieutenant-Commander (ship’s doctor) and had served on North Atlantic convoy escorts as well as on minesweepers during the Normandy invasion. After being torpedoed in the English Channel in March 1945, his ship had been written off and hostilities had ceased while he was waiting to join another.

Upon returning to his home in North West River, he took over the running of the small Grenfell Mission hospital there, thus relieving his Mother, nurse Mina Paddon, who had spent the last five years doing the job in very difficult circumstances. Her husband, Dr. Harry Paddon, had died in 1939 of a simple bacterial infection. Antibiotics could have saved his life, but they weren’t available at the time.

For Dad, you might say it was out of the frying pan and into the fire. Nobody was shooting at him, but the problems he faced in the fields of health and education in Labrador were monumental and he devoted the rest of his working career to overcoming them. No doubt he was mulling over these issues while walking home from the hospital in the summer of 1945 when a local lad came running up to him with a small object clutched in one hand. “What’s this

doctor?” he inquired. My father then got what was probably the biggest surprise of his life (If you exclude being torpedoed in the middle of the night a few months previous!).

I now need to take you back to January 1945:

The war was winding down, but the great airlift of men and aircraft from North America to Europe was at its height. Many of these aircraft transited through Goose Bay (about 25 miles west of North West River on the same

body of water).

Due to the wartime requirements pilot experience was low and the accident rate was high. Many aircraft were lost or came to grief trying to arrive or depart Goose Bay. During my own early flying career, I was a Twin Otter co-pilot based in Goose Bay and I often flew with Roy Cooper. He had been a Mosquito night fighter pilot during the war and would point out wrecks to me as we flew out to the coast of Labrador.

A USAF B-24 Liberator similar to this one crashed in Lake Melville in 1945

Sometime around midnight on January 13th, a USAF B-24 Liberator bomber went down shortly after takeoff from Goose Bay. There was one survivor from the nine-man crew, but he died about a week later despite heroic efforts to save him (efforts which included flying brain surgeons in from the U.S.). I recently obtained the accident report and it was speculated that one engine may have produced a long trail of flame when

only a few hundred feet up and there would have been little time to recover from a spiral dive.

Returning to the summer of 1945 and the sight of a dumbfounded doctor staring down at a small shiny object clutched in the hand of a young boy. “Where did you get THAT?!” Dad exclaimed.

The youngster said it had been on the beach and that more were coming in on the tide. My father ran the short

My father ran the short distance to North West River’s beautiful sandy beach and was further amazed to see dozens of the little things lying about above the high water mark.

brought back to climb power shortly after take-off. This was not an unusual occurrence with a new engine and the flame would quickly extinguish,

The Captain, Roger J. Mellion, was 21 years old and had 436 hours total flight time. It’s not hard to imagine him being distracted by what must have seemed like a dangerous fire and subsequently losing his instrument scan. The aircraft would have been

distance to North West River’s beautiful sandy beach and was further amazed to see dozens of the little things lying about above the high water mark. He told the boy to get all his friends and pick up as many as they could and that he would give them two cents for each (not bad money for a kid in Labrador in 1945). Dad soon found himself surrounded by a gaggle of excited youngsters who

The little vials were washing up on shorelines and islands all around the head of Lake Melville and Dad instituted a search which resulted in the collection of some 300-400 of them.

were grabbing all they could. He did the same and at one point he stood up, stared wistfully at one of the little objects and thought “If I’d had you a few years ago I could have saved my own father’s life.”

He was holding a vial of penicillin.

It’s hard to overstate how valuable a find this was. Penicillin was new in

those days and the medical mission my parents and grandparents worked for simply couldn’t get any. The Allied militaries had it but were using it to treat wounded servicemen in Europe and the Far East. As was the case with my grandfather, a simple bacterial infection could be fatal back then and unless you were wealthy or connected

you were probably out of luck. And it was miraculously effective. My mother was a nurse in central England throughout the war and could remember giving it to wounded troops. They would quickly recover from horribly infected wounds.

The little vials were washing up on shorelines and islands all around the head of Lake Melville and Dad instituted a search which resulted in the collection of some 300-400 of them. There was a prize for whoever could bring in the most which was won by Sandy Ritch, who I remember very well. It was put to use immediately and one of the first to benefit was a little girl named Stephanie Peacock.

Stephanie lived in Nain on the north coast of Labrador and had contracted pneumonia after falling into the town’s freezing harbour. She was close to death when Dad arrived on a dogteam medical patrol. He wasn’t even sure how much of the precious drug to give her but took his best guess.

Within a few hours, Stephanie was sitting up looking for something to eat and I had the great pleasure of getting her side of the story during a visit to Gander, where she is a retired school teacher. I also talked to 93year-old Mrs. Jean Crane, who was

one of the youngsters who helped pick up the vials in 1945. What an amazing experience to talk to these two ladies!

My father used every vial of the penicillin that washed ashore that day, even into the 1950s when antibiotics became more readily available. He just couldn’t bring himself to throw it away. I find it interesting to speculate about how many of my fellow Labradorians are around today thanks to this event.

To conclude, I will say to the reader that every January 13th I take some time to think of Captain Roger J. Mellion and the eight other young men who lost their lives in the crash of B24 Liberator S/N 44-49538 “The Murmuring Mummy” on that day in 1945. It can’t be confirmed absolutely, but circumstantial evidence indicates that the penicillin had been part of a freight consignment on the aircraft. It had remained aboard the wreck and gone to the bottom of Lake Melville when the ice broke up in the spring. A few months later it drifted ashore. Mellion and his crew never made it to Europe to take part in the fight against totalitarianism, but they made a huge contribution to the lives of Labradorians through their sacrifice.

Reflecting on a simpler time in Newfoundland and Labrador

BY ALBERT BUTT

Part Two

The Kyle

Before departure on the SS Kyle, my parents needed to spend about two weeks getting sufficient supplies and food for what was normally a three-day voyage. We had a very large, homemade wooden box which we called the ‘bread box’, with rope handles which contained several loaves of homemade bread, hard bread, molasses cookies, Good Luck margarine, tea, several tins of Carnation milk, pepper and salt, etc. When we returned in the fall, the bread box was mostly filled with bakeapples.

The author’s mother with the SS Kyle which ran aground on a sand bar in Harbour Grace

SS Kyle stuck in ice off St. Anthony for 17 days in 1948.

During those years there were no medical services at Square Islands, but there was a lady in the settlement who often posted a notice to let us know that clergy or a medical boat would be coming. I don’t think I ever used any medical services, but I do remember attending a church service outside her house. I also remember things my mom took, including Bayer aspirin, Buckley’s cough syrup, iodine, Vicks VapoRub, Mercurochrome, Scott’s Emulsion and Brick’s Tasteless Medicine. It was not uncommon to use some of the above to treat blisters when jigging for codfish, setting and hauling fishing nets, splitting or salting and drying fish.

I remember my sister Iva falling on a rock and cutting her leg and my mom making a bread poultice to help the healing. In those days, a bread poultice was a popular traditional home remedy for addressing boils, skin conditions, injuries and infected areas. It was a soft and moist paste of bread and milk applied to problem areas. It was beneficial because it generated heat, helped heal infections and reduced pain. I also remember my mom burning white cloth from a flour sack, which she’d put on different cuts to prevent infection.

I read somewhere that the SS Kyle was Newfoundland’s first scheduled ferry and was the coastal boat most

used to transport supplies and provide transportation for people from Carbonear to Square Islands. When built, it was an icebreaker in the water, as it was equipped with a heavy forward end and spoon-shaped bow designed for safety purposes. It was part of the Alphabet Fleet and was named in accordance with the naming convention of the Reid Newfoundland Company, which stated that their ships must bear the name of a Scottish town. It entered the service in 1913 and, in 1926, was moved to the route between Carbonear and Labrador ports. It was designed to hold 68 first class and 142 second class passengers, with this number often exceeded because I know some men stayed in the cargo holds. I don’t know if anyone travelled first class, but I know my family travelled second class and occupied iron bunks in the steerage. Children were placed in the lower bunks because if the boat rolled, they would just roll on the floor rather than fall from the high bunks. The Kyle provided 33 years of service on the Labrador run.

Over the years there were many captains for the SS Kyle, including Captains Tavenor, Burgess, and Connors, but I believe it was Captain O’Keefe

during my time, who, like the passengers, faced many dangers while travelling to the Labrador including high winds, tides, fog, high waves, icebergs, growlers and slush ice.

Having faced such conditions so many times – including the 17 days we were stuck in the ice off St. Anthony – I have no problem relating to the people who make a living from the sea like the movie The Perfect Storm, or Wicked Tuna: Outer Banks with boats named Saga, Northwestern, or Wizard; or the coast guard delivering supplies to the high arctic, or the loss of the MV William Carson, which sank in 1977 near Battle Harbour after hitting heavy ice.

One of my greatest fears was the Kyle crossing White Bay, which was considerably rougher than crossing the other bays. Very often, and sometimes during the night, we ran into the teeth of a full-blown Atlantic storm complete with strong winds and high waves which crashed onto the bow. When it rode up on a wave, I often slid down to the bottom of my bunk because the bow had gone under the wave. I could feel the Kyle crest then crash down the other side of the wave. The Kyle would wobble and then slowly but surely the bow

would come out of the water, only to ride up the crest of another wave. I was often scared, but do not remember ever getting seasick.

The Second World War may have started overseas, though it did have a definite impact on the lives of people living along the shores of Newfoundland and Labrador. It was reported that German submarines were seen in Conception Bay, where Carbonear is situated. In 1942, four iron ore carriers were felled by German U-boats around Bell Island, which is just off the coast. The SS Caribou, a Newfoundland passenger ferry, was torpedoed by a German submarine with a loss of 137 people.

Because of the number of German U-boats targeting merchant ships, basic food supplies were scarce to the point that the government introduced ration books to Newfoundlanders to avoid the hoarding of such supplies. A rationing order was passed in 1943 when I was seven years old. Local fishing families like mine were impacted, as I remember the Kyle only steaming forward along the coast during dark hours when blackout regulations were suggested, which was deemed necessary to avoid the U-boats.

In general, the trip from Carbonear to Square Islands was three to four days, depending on the weather. But in 1948, when I was 12 years old, we were stuck in the ice off St. Anthony for 17 days. During those 17 days, food was scarce and we lived mostly on bread from a bakery, which we called ‘baker’s fog’, and corned beef from a tin, which we called ‘bully beef’. There’s a photo of my brother

Albert’s brother Reg Butt and friend Bob Forward sit on the Kyle’s anchor while stuck in ice off St. Anthony

Reg and his friend Bob sitting on the anchor of the Kyle while stuck in the ice. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then this falls into that category.

The Kyle usually made its last Labrador run in late October, but in most cases, smaller settlements did not have a big enough wharf or deep enough water to dock the larger coastal boats, so they were put in a holding pattern until settlement motorboats came alongside to deliver or pick up people and supplies. There were no roads between communities and therefore all connections were made by boat.

I remember one summer when my sister Iva was supposed to come to Square Islands but was not on the scheduled trip because it was determined that there were no passengers for Square Islands. I remember my parents being worried, though she got off in Snug Harbour and returned to Square Islands (approximately 20 miles) the next day on one of the boats that were collecting salmon along the coast

*Stay tuned for part three of our series ‘A Life Remembered’ in the November 2024 issue of Downhome Magazine.

Spotted Island

BY NATHAN FREAKE

Fall in Labrador is so brief there are only a lucky few who witness it. When most think of life up north, they picture the cold wind, the mounds of snow, and the long –and I mean long –winters. However, not many stop to consider the spectacle of the Labrador fall. It’s something to behold but be warned. Blink and you might miss it.

The transition from summer is quick. The winds begin to carry cooler air in early September, and the mornings bring more frost than dew. I remember, as a young boy, running late for the bus and forgetting to throw on a sweater. Looking out the window, the sunshine could have fooled anyone, but as I opened the door and ran to the bus stop, the air was far from a summer breeze.

autumn season, it’s almost a necessity to get outside and enjoy it.

During our winters you have time to take it all in, while in the fall you have to make the most of it. The transition to winter comes fast, and you never know how early it will strike.

One of my favourite things to do in the fall is kayaking on the lake around our cabin, though, unfortunately, I haven’t done this as often as I should.

During our winters you have time to take it all in, while in the fall you have to make the most of it. The transition to winter comes fast, and you never know how early it will strike.

The frost on the car’s windows should have been a good indicator, but you know how it is when you’re running late. The grass, green and glossy like thick hair gel crunched and splintered like glass beneath me. I’ll always remember the instant warmth of the bus. On the bright side, I didn’t have to drag home a sweater in my hands –not much need for it when the afternoon sun had taken care of the prior night’s cooling.

The sights of the Big Land during those few brief weeks are breathtaking. In the mornings the lakes and ponds are blanketed with billows of fog, the hills rolling with a sea of trees, shifting colours from yellow to orange, to red. In the evening, the golden glow of the hills is a sight ripped straight from fantasy fiction. Walking a trail, with the bright leaves coating the ground below, the sun peaking through the trees seems to last only a few moments before fading. With the quick waning of our

There aren’t many opportunities to do this as the short season and the Monday-to-Friday lifestyle significantly limit the hours we can take advantage of it. There’s nothing quite like the last ride in a kayak before the winds begin to change toward winter. The lifejacket strapped around you feels smaller than it does in the summertime because you’ll be chilled without a hoodie and a plaid jacket beneath. Your breath is visible briefly in the frigid air, and your fingers are slow to uncoil around the paddles. All around you, the flat surface of the water reflects a kaleidoscope of changing trees, and the evening sun warms the tip of your nose and washes over the landscape.

Sitting there under the autumn sky of the Labrador makes you feel so small in a world so large, and it’s a privilege to experience.

There are 365 days in a year and so few of those make up a Labrador fall. Make sure you make the most of them.

photo finish

Blueberry Sunset

In between the rain the blueberries just added to the beautiful colour-filled sky here in Labrador City

KEITH FITZPATRICK

Labrador City, NL