Review

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Evolutionary Adaptation to Lifestyle and the Environment

Jim Parker, Claire O’Brien, Jason Hawrelak and Felice L. Gersh

Special Issue

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

Edited by Dr. Michał Kunicki

4.5

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031336

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Review

PolycysticOvarySyndrome:AnEvolutionaryAdaptationto LifestyleandtheEnvironment

JimParker 1,* ,ClaireO’Brien 2,JasonHawrelak 3 andFeliceL.Gersh 4

1 SchoolofMedicine,UniversityofWollongong,Wollongong2500,Australia

2 FacultyofScienceandTechnology,UniversityofCanberra,Bruce2617,Australia; Claire.obrien@canberra.edu.au

3 CollegeofHealthandMedicine,UniversityofTasmania,Hobart7005,Australia;Jason.Hawrelak@utas.edu.au

4 CollegeofMedicine,UniversityofArizona,Tucson,AZ85004,USA;felicelgersh@yahoo.com

* Correspondence:jimparker@ozemail.com.au

Citation: Parker,J.;O’Brien,C.; Hawrelak,J.;Gersh,F.L.Polycystic OvarySyndrome:AnEvolutionary AdaptationtoLifestyleandthe Environment. Int.J.Environ.Res. PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph19031336

AcademicEditor:MichałKunicki

Received:3December2021

Accepted:21January2022

Published:25January2022

Publisher’sNote: MDPIstaysneutral withregardtojurisdictionalclaimsin publishedmapsandinstitutionalaffiliations.

Copyright: ©2022bytheauthors. LicenseeMDPI,Basel,Switzerland. Thisarticleisanopenaccessarticle distributedunderthetermsand conditionsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY)license(https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ 4.0/).

Abstract: Polycysticovarysyndrome(PCOS)isincreasinglyrecognizedasacomplexmetabolic disorderthatmanifestsingeneticallysusceptiblewomenfollowingarangeofnegativeexposuresto nutritionalandenvironmentalfactorsrelatedtocontemporarylifestyle.ThehypothesisthatPCOS phenotypesarederivedfromamismatchbetweenancientgeneticsurvivalmechanismsandmodern lifestylepracticesissupportedbyadiversityofresearchfindings.Theproposedevolutionarymodel ofthepathogenesisofPCOSincorporatesevidencerelatedtoevolutionarytheory,geneticstudies, inuterodevelopmentalepigeneticprogramming,transgenerationalinheritance,metabolicfeatures includinginsulinresistance,obesityandtheapparentparadoxofleanphenotypes,reproductive effectsandsubfertility,theimpactofthemicrobiomeanddysbiosis,endocrine-disruptingchemical exposure,andtheinfluenceoflifestylefactorssuchaspoor-qualitydietandphysicalinactivity. Basedonthesepremises,thediverselinesofresearcharesynthesizedintoacompositeevolutionary modelofthepathogenesisofPCOS.Itishopedthatthismodelwillassistcliniciansandpatientsto understandtheimportanceoflifestyleinterventionsinthepreventionandmanagementofPCOSand provideaconceptualframeworkforfutureresearch.Itisappreciatedthatthistheoryrepresentsa synthesisofthecurrentevidenceandthatitisexpectedtoevolveandchangeovertime.

Keywords: polycysticovarysyndrome;evolution;insulinresistance;infertility;toxins;endocrinedisruptingchemicals;environment;lifestyle;diet

1.Introduction

Polycysticovarysyndromeisareversiblemetabolicconditionthatmakesasignificant contributiontotheglobalepidemicoflifestyle-relatedchronicdisease[1–3].Manyof thesechronicdiseasesshareasimilarpathogenesisinvolvingtheinteractionofgeneticand environmentalfactors[4–6].TherevisedInternationalGuidelinesfortheassessmentand managementofwomenwithPCOSemphasizethattheassociatedmetabolicdysfunction andsymptomsshouldinitiallybeaddressedvialifestyleinterventions[7].Aunified evolutionarymodelproposesthatPCOSrepresentsamismatchbetweenourancientbiology andmodernlifestyle.

Evolutionarymedicineisanemergingdisciplineinvolvingthestudyofevolutionary processesthatrelatetohumantraitsanddiseasesandtheincorporationofthesefindings intothepracticeofmedicine[8].Evolutionarymedicinebringstogetherinterdisciplinaryresearchtoinformclinicalmedicinebasedontheinfluenceofevolutionaryhistoryonhuman healthanddisease[9].Previousutilizationoftheprinciplesofevolutionarymedicinehas beenlimitedtomonogeneticdiseases(cysticfibrosis,sicklecellanemia,phenylketonuria andmanyothers),drugresistanceofmicroorganisms,tumorgrowthandchemoresistance[8].Futureinsightsintotheapplicationofevolutionaryresearchoffersthepotential

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031336https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph

toimproveandpersonalizetheestablishedmedicalandscientificapproachestocomplex chronicdiseasessuchastype2diabetes,metabolicsyndromeandPCOS[5,9].

Theevolutionaryoriginsofcomplexchronicdiseasesincorporateconsiderationsofrelativereproductivefitness,mismatchbetweenourbiologicalpastandmodernenvironment, trade-offsinvolvingcombinationsofgenetictraits,andevolutionaryconflicts[8,10].These evolutionaryfactorsarerelevantwhenanalyzingthecontributorstothepathogenesisof PCOSinmodernandmodernizingsocietiesthatresultinamismatchbetweenourrapid culturalevolutionwithourslowbiologicalevolution[11,12].Theuniqueculturalevolution ofhumansdoesnothaveaplausibleanalogueinmostotherspeciesandisincreasingly recognizedtoplayasignificantroleinthepathogenesisofmetabolicdiseasessuchas PCOS[5,13–17].

Polycysticovarysyndromeisacomplexmultisystemconditionwithmetabolic,endocrine,psychological,fertilityandpregnancy-relatedimplicationsatallstagesoflife[7,18]. ThemajorityofwomenwithPCOSmanifestmultiplemetabolicfeaturesincludingobesity, insulinresistance(IR),hyperlipidemiaandhyperandrogenism[19,20].PCOSresultsin anincreasedriskofdevelopingmetabolicdisease(type2diabetes,non-alcoholicfatty liverdisease[NAFLD]andmetabolicsyndrome),cardiovasculardisease,cancer,awide arrayofpregnancycomplications(deepvenousthrombosis,pre-eclampsia,gestational diabetes[GDM],macrosomia,growthrestriction,miscarriage,stillbirthandpretermlabor)andpsychologicalproblems(anxiety,depression)[6,21–25].PCOSispartofacluster ofinter-relatedmetabolicconditionsandmakesasignificantcontributiontothechronic diseaseepidemic.

ExtensiveresearchsuggeststhattheetiologyofPCOSinvolvesaninteractionbetween environmentalfactorsandgenevariants,althoughithasbeensuggestedthatgeneticfactors contributelessthan10%todiseasesusceptibility[26–28].Alargenumberofgeneticand genome-wideassociationstudies(GWAS)haveidentifiedcommongenelociassociated withPCOSphenotypesindifferentethnicpopulations[29–31].Theseappeartobenormal genevariantsorpolymorphisms,giventhefrequencyandtypeofgenesthathavebeen identified.PCOSisthereforeviewedasapolygenictraitthatresultsfromaninteraction betweensusceptiblegenomicvariantsandtheenvironment.

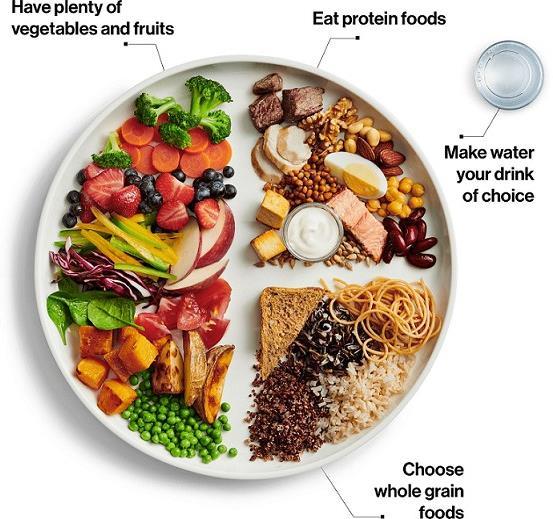

PCOSeffectsupwardof10%ofreproductive-agedwomen,estimatedatover 200million womenworldwide[32,33].PCOSisthoughttobeincreasinginincidenceinbothdevelopinganddevelopednationsasaresultoflifestyle-relatedchangesindietquality,reduced physicalactivity,ubiquitousenvironmentalendocrine-disruptingchemicals(EDC),altered lightexposures,sleepdisturbance,heightenedlevelsofstressandotherenvironmental factors[11,34–38].Thesefactors,andthehighprevalenceofPCOS,suggestthattherecould beanevolutionarybasisforthesyndrome[15,16,39].Evolutionarymedicinehaschanged theparadigmforunderstandingPCOS,acknowledgingmanyofthecontributinglifestyle andenvironmentalfactorsthatfacilitatetheobservedmetabolicandclinicalfeaturesand thatarealsosharedwithrelatedmetabolicdiseases[8].These“mismatchdisorders”are estimatedtomakeasignificantcontributiontochronicdiseaseindevelopedcountriesand agrowingproportionofdisabilityanddeathindevelopingnations[3].Accordingtothe GlobalBurdenofDiseaseStudy,thehumandietisnowtheleadingriskfactorformorbidity andmortalityworldwide[3].Inkeepingwiththesefindings,dietisrecognizedasoneof themajorcontributorstothegrowingprevalenceofPCOSglobally[7,40].

DietaryandenvironmentalfactorsarehypothesizedtohaveanimpactondevelopmentalprogrammingofsusceptiblegenevariantsinwomenwithPCOS[41–43].Extensive experimentalevidencesuggeststhatprenatalandrogenexposuremayplayaroleinthe pathogenesisofPCOS-likesyndromesinanimalmodels[19,44–46].ThediscoveryofnaturallyoccurringPCOSphenotypesinnon-humanprimatessupportsasurvivaladvantage ofahyperandrogenic,insulinresistantphenotypewithdelayedfertility[47].Inhumans, theoriginofexcessandrogensmaybefrommaternal,fetalorplacentalsources.Inaddition,emergingandconcerningevidencesuggeststhatEDCmaycontributetoalteredfetal programmingandplayaroleinthepathogenesisofPCOS[41,48].

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 2of25

Inuterogenomicprogrammingofmetabolicandendocrinepathwayscanincreasethe susceptibilityofoffspringtodevelopPCOSfollowingexposuretospecificnutritionaland environmentalconditions[45].ThisviewofthepathogenesisofPCOSisconsistentwith theDevelopmentalOriginsofHealthandDisease(DOHaD)modelproposedbyNeel[49]. Postnatalexposuretolifestyleandenvironmentalfactors,suchaspoor-qualitydietand EDC,mayactivateepigeneticallyprogrammedpathwaysthatfurtherpromotetheobserved featuresofPCOS.Dietaryandlifestyleinterventionshavedemonstratedthatmanyofthe clinical,metabolicandendocrinefeaturesofPCOScanbereversed[7,50,51].

Lifestyle-inducedchangesinthegastrointestinaltractmicrobiomeareanothersignificantfactorintheetiologyofPCOS[52,53].Dysbiosisofthegutmicrobiotahasbeen hypothesizedtoplayaroleinincreasedgastrointestinalpermeability,initiatingchronic inflammation,insulinresistance(IR)andhyperandrogenism[40].Numerousstudieshave reportedreducedalphadiversityofthemicrobiomethathasbeenassociatedwiththe metabolic,endocrineandclinicalfeaturesobservedinwomenwithPCOS[54,55].The resultingdysbiosishasbeenshowntobereversibleafterinterventionsaimedatimproving dietqualityortreatmentwithprobioticsorsynbiotics[50,51,56–58].

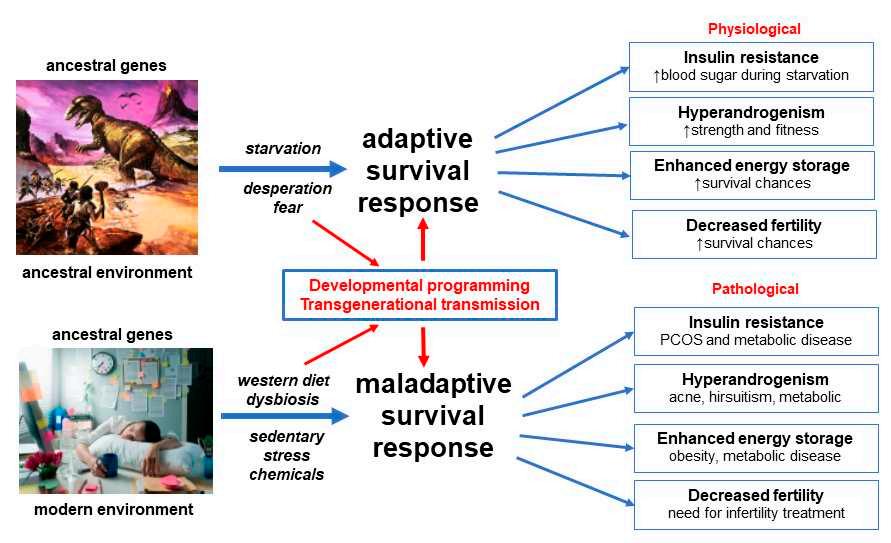

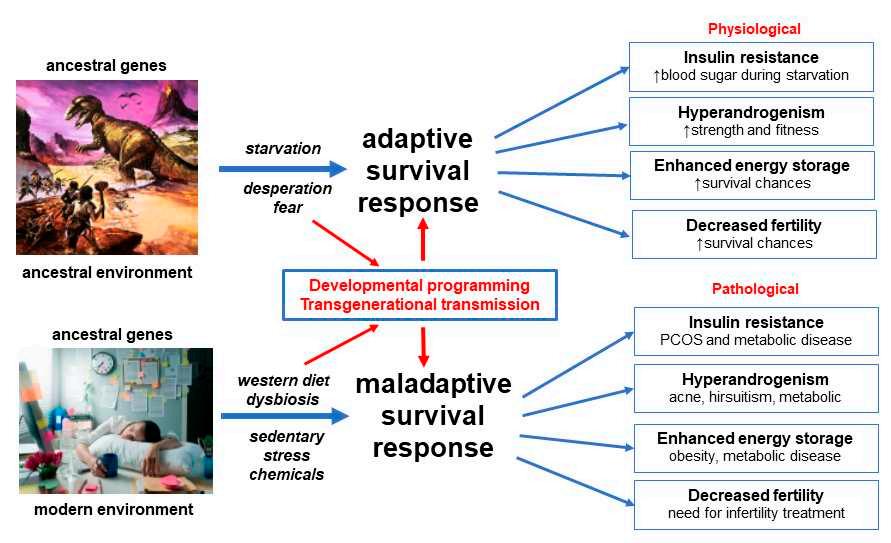

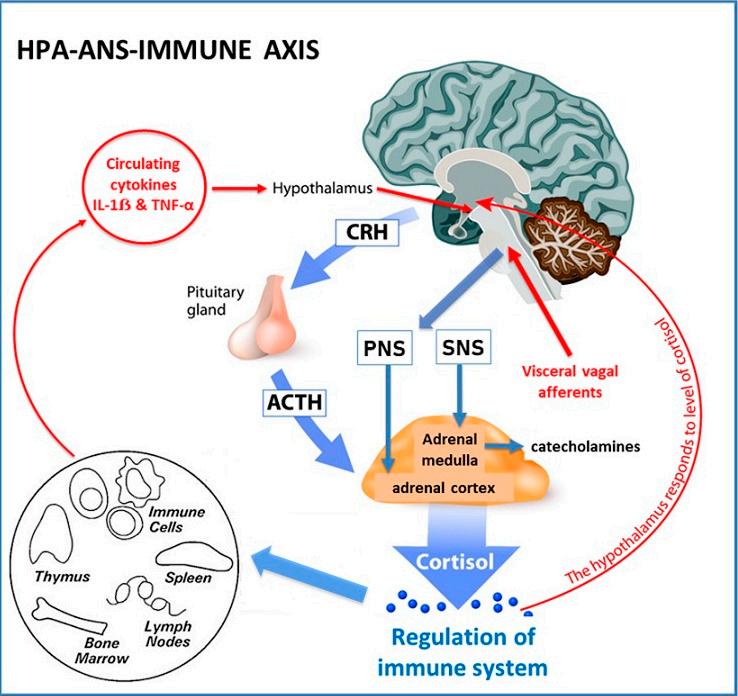

AunifiedevolutionarytheoryofthepathogenesisofPCOSproposesthatancient geneticpolymorphismsthatwerealignedwiththeenvironmentofthatera,resultedin anadaptivesurvivaladvantageinoffspringinancestralpopulations[14–16,28].When thesesamegeneticvariantsareexposedtomodernlifestyleandenvironmentalinfluences, maladaptivephysiologicalresponsesoccur.Theprioradvantagesofinsulinresistance, hyperandrogenism,enhancedenergystorageandreducedfertilityinancestralpopulationsbecomepathologicalandresultintheobservedfeaturesofPCOSincontemporary women(Figure 1).

2.MaterialsandMethods

Theliteraturesearchfocusedonresearchpublicationsrelatedtothepathogenesisof PCOSusingthekeywordslistedaboveandrelatedmeshtermsfordataontheevolutionary aspectsofPCOS,geneticstudies,inuterodevelopmentalepigeneticprogramming,transgenerationalinheritance,metabolicfeaturesincludinginsulinresistance,obeseandlean PCOSphenotypes,reproductivechangesandsubfertility,impactofthemicrobiomeand dysbiosis,possibleeffectsofendocrine-disruptingchemicalexposureandtheinfluenceof lifestylefactorssuchasdietandphysicalactivity.ThedatabasessearchedincludedPubMed,

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 3of25

Figure1. Evolutionarymodelofthepathogenesisofpolycysticovarysyndrome.Adaptedwith permissionfromRef.[12].2021JournalofACNEM.

Scopus,CochraneandGoogleScholar.Relevantpaperswereselected,andcitationsearches wereperformed.

Thepresentmanuscriptsynthesizesthefindingsintoaunifiedevolutionarymodel. Thefollowingtextispresentedasanarrativereviewoffactorsinvolvedinthepathogenesis ofPCOSandisdiscussedintenmainsubjectareasthatprovidetherationaleforthe developmentofaunifiedmodel.1.Evolution2.Genetics3.DevelopmentalEpigenetic Programming4.MicrobiomeandDysbiosis5.Insulinresistance6.Obesityandthe leanparadox7.Endocrine-DisruptingChemicalExposure8.Lifestylecontributorsto thepathogenesisofPCOS9.CircadianRhythmDisruptionandPCOS10.Conceptual FrameworkandSummaryoftheUnifiedEvolutionaryModel.

3.PathogenesisofPCOS

3.1.Evolution

ThedescriptionofPCOSphenotypescanbefoundinmedicalrecordsfromantiquity andthemodernsyndromewasdescribedover80yearsago[17,59].Nevertheless,there isongoingdebateregardingtheevolutionaryoriginsofPCOS[15–17,39,60–64].PCOS susceptibilityallelesmayhaveariseninourphylogeneticancestors,inthehunter–gatherer PaleolithicperiodoftheStoneAge,aftertheNeolithicAgriculturalRevolutionorfollowing theIndustrialRevolution[16,17].Fromanevolutionaryperspective,nearlyallgenetic variantsthatinfluencediseaseriskhavehuman-specificorigins,butthesystemstheyrelate tohaveancientrootsinourevolutionaryancestors[8].Regardlessoftheprecisetiming oftheoriginofPCOSinhumans,thecomplexmetabolicandreproductivegenevariants identifiedinwomenwithPCOSrelatetoancientevolutionary-conservedmetabolicand reproductivesurvivalpathways[15,29].Althoughevolutionaryhypothesesaboutdisease vulnerabilityareimpossibletoprovetheyhavethepotentialtoframemedicalthinkingand directscientificresearchfortheproximatecausesofdisease[15,60].

MultiplehypotheseshavebeenproposedregardingtheevolutionaryoriginsofPCOS andrelatedmetabolicdiseases[8,60,63].Thesehypothesesarefocusedontherelative importanceofmetabolicsurvivaladaptationsversusimprovedreproductivesuccess,ora combinationofboth.Adetailedanalysisofthesehypotheses,andthecomplexitiesofthe evolutionaryconsiderations,havebeenreviewedelsewhereandisbeyondthescopeofthe presentreview[8,60].OnecommonthemeisthatPCOSmaybeviewedasa“conditional phenotype”whereaspecificsetofconditionshasunmaskednormallyunexpressedor partlyexpressedgeneticpathways,whichthenprovideasurvivaladvantageundercertain environmentalconditions[14,16].

Allorganismshavephysiologicaladaptiveresponsestodealwithchangingenvironmentalconditions(starvation,fasting,physicalthreat,stressandinfection)andthevarying demandsofinternalphysiologicalstates(pregnancy,lactationandadolescence)[14,65]. IthasbeenproposedthatthePCOSphenotypemayhavebeeninvokedinspecificenvironmentalconditionsinancestralpopulationsasashort,mediumorevenlong-term adaptivesurvivalmechanism[15–17].TheviewofPCOSasaconditionalphenotypeproposesthatthesephysiologicalresponsesbecomepathologicalinourmodernenvironment duetofactorssuchasfoodabundance,reducedphysicalactivity,circadiandisruption, stressandenvironmentalchemicalexposure.Thetransgenerationalevolutionarytheory ofthepathogenesisofPCOSencompassesalloftheaboveideastoexplaintheobserved pathophysiologicalandclinicalfeaturesofPCOS[28].

Itisgenerallyacceptedthatalmostallpre-industrialsocietiesandanimalpopulations experiencedseasonalorunpredictableepisodesoffoodshortagethatappliedevolutionary pressuretodevelopmetabolicandreproductiveadaptivesurvivalresponses[17,49].It isalsoappreciatedthatmetabolicandreproductivepathwaysareinterconnectedand involvereciprocalfeedbackcontrolmechanisms[66–68].Duringperiodsofstarvation, anorexiaorexcessiveweightgain,reproductionisdown-regulatedandovulationbecomes irregularorceases[69,70].Similarly,metabolicfunctioniscoordinatedwiththemenstrual cycletoensureoptimalphysiologicalconditionsforfertilization,implantation,pregnancy,

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 4of25

parturitionandlactation[71].Recentresearchhaselaboratedonthedetailsofhowsomeof thesecomplexregulatorymechanismsinteractusingspecifichormonal,nutrientsensing andintracellularsignalingnetworks[72–74].

Detailsofthemechanismsunderlyingtheproposedadaptivesurvivaladvantages ofIR,hyperandrogenism,enhancedenergystorageandsubfertilityhavebeenobtained frompaleolithicrecords,animalmodelsandhumanpopulationsexposedtoadverseenvironmentalconditionssuchaswarandfamine-inflictedstarvation[14,16,62,63].Multiple linesofevidencesupportthemaladaptiveresponseofhumanpopulationstorapidly changingnutritional,physical,psychologicalandculturalenvironments,inthemodern world[5,11,14,75].These“adaptations”resultinpathologicalresponsestoIR,hyperandrogenism,enhancedenergystorageandovulation(Figure 1).

Theoriesofevolutionarymismatchhavealsobeenadvancedtoexplainallofthe clusterofmetabolicdiseasesassociatedwithPCOS(type2diabetes,metabolicsyndrome, NAFLDandcardiovasculardisease)andfollowthesamesetofbasicprinciplesandexplanations[14,76].Thiscommonbodyofevolutionaryevidenceissupportedbytheincreasing incidenceofmetabolic-relateddisease,suchasdiabetesandobesity,indevelopedcountries andindevelopingnationsadoptingaWesterndietandlifestyle[11,77].Inaddition,the demonstratedreversibilityofPCOSandrelatedmetabolicandbiochemicalfeaturesfollowingchangesindiet,increasedphysicalactivityandotherlifestyleinterventions,adds furthersupporttoatransgenerationalevolutionarymodel[50,51].

3.2.Genetics

TheheritablenatureofPCOShasbeenproposedsincethe1960′ sfollowingarange offamilial,twinandchromosomalstudies[78–80].Cytogeneticstudiesfailedtoidentify karyotypicabnormalitiesandgeneticstudiesdidnotshowamonogenicinheritancepattern followingexaminationofcandidategenes[81,82].Inaddition,twoormorephenotypes canbepresentinthesamefamilysuggestingthatsomeofthephenotypicdifferencescould beaccountedforbyvariableexpressionofthesamesharedgenes[81,83].

Themappingofthehumangenomein2003[84]andthepublicationofthehuman haplotypemap(morethanonemillionsinglenucleotidepolymorphismsofcommon geneticvariants)in2005[85],leadtotherealizationthatmostDNAvariationissharedby allhumansandisinheritedasblocksoflinkedgenes(linkagedisequilibrium)[86].These advancesenabledarevolutionincase-controlstudiesandthedevelopmentofGWASwhich maptheentirehumangenomelookingforsusceptibilitygenesforcomplextraitssuchas obesity,type2diabetesandPCOS[81].

ThefirstPCOSGWASwaspublishedin2010anddemonstrated11genelociassociated withPCOS[87].Additionallocihavesubsequentlybeenfoundinseveraldifferentethnic groups[86,88].ThefirstGWASanalysisofquantitativetraitswaspublishedin2015and showedthatavariant(rs11031006)wasassociatedwithluteinizinghormonelevels[88]. ThelargestGWASincludedameta-analysisof10,074PCOScasesand103,164controls andidentified19locithatconferriskforPCOS[29].Thegenesassociatedwiththese lociinvolvegonadotrophinaction,ovariansteroidogenesis,insulinresistanceandtype 2diabetessusceptibilitygenes.ThefirstGWASusingelectronichealthrecord-linked biobankshasintroducedgreaterinvestigativepowerandidentified2additionalloci[89]. Thesevariantswereassociatedwithpolycysticovariesandhyperandrogenism(rs17186366 near SOD2)andoligomenorrhoeaandinfertility(rs144248326near WWTR1)[89].In additiontoidentifyingcommongenevariantsforPCOSphenotypes,findingthesame signals(THADA,YAP1andc9orf3)inChineseandEuropeanpopulationssuggeststhat PCOSisanancienttraitthatwaspresentbeforehumansmigratedoutofAfrica[81].

MorerecentlyMendelianrandomization(MR)studieshavebeenusedtoexplorethe potentialcausativeassociationbetweengenevariantsidentifiedinGWASand PCOS[90,91] ManyofthegenevariantsidentifiedinGWASarelocatedinnon-codingregionsof DNA[92].ThegenesorfunctionalDNAelementsthroughwhichthesevariantsexert theireffectsareoftenunknown.Mendelianrandomizationisastatisticalmethodology

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 5of25

usedtojointlyanalyzeGWASandquantitativegenelocitotestforassociationbetween geneexpressionandatrait,duetoasharedorpotentiallycausalvariantataspecific locus[93].AdetailedanalysisofMRmethodologyandthelimitationsofthisstatistical toolisbeyondthescopeofthepresentreview.AlthoughMRstudieshavethepotential toinfercausationitisrecognizedthattheyalsohavelimitationsin PCOSresearch[90]. Nevertheless,preliminaryevidencesuggeststhatseveralgenesrelatedtoobesity,metabolic andreproductivefunction,mayplayacausalroleinthepathogenesisofPCOS[90,91].

DecadesofgeneticresearchhasthereforecharacterizedPCOSasapolygenictraitthatresultsfrominteractionsbetweentheenvironmentandsusceptiblegenomic traits[27,29,79,88] Thefailuretoidentifyaqualitativeormonogenicinheritancepatternandthefindings fromGWAS,MR,familialandtwinstudies,suggeststhattheheritabilityofPCOSislikely tobeduetothecombinationofmultiplegeneswithsmalleffectsize,ashasbeenfound withobesityandtype2diabetes[79,80,94–96].Polygenictraitsaretheresultofgenevariantsthatrepresentoneendofthebell-shapednormaldistributioncurveofcontinuous variationinapopulation[97].Fromanevolutionaryperspective,womenwithPCOS mayrepresentthe“metabolicelite”endofthenormaldistributioncurve,beingableto efficientlystoreenergyinperiodsoffoodabundanceanddown-regulatefertilityintimes offoodscarcity,oreveninanticipationofreducedseasonalfoodavailabilityasapredictive adaptiveresponse[16,17,60].

TherealizationthatPCOSisaquantitativetrait(phenotypedeterminedbymultiple genesandenvironmentalfactors)hasfar-reachingimplicationsforthediagnosis,treatment andpreventionofsymptomsandpathologyassociatedwithPCOS.Theimplications requireashiftinthinkingaboutPCOSasa“disease”toavariationofnormalmetabolic andreproductivefunction.Thisshiftinvitesachangeinvocabularyfromtalkingabout “disorder”and“risk”totalkingabout“expression”and“variability”[97].Thisnew understandingsupportsandreinforcesanevolutionarymodelofthepathogenesisofPCOS. Inkeepingwiththismodel,multiplelinesofevidencesuggestthatinheritedPCOSgene variantsaredevelopmentallyprogrammedinawaythatprimesthemforactivationby nutritionalandenvironmentalfactorsinpostnatallife[41,42,98].

3.3.DevelopmentalEpigeneticProgramming

ThedevelopmentalprogrammingofPCOSrepresentschangesingeneexpression thatoccurduringcriticalperiodsoffetaldevelopment[99].Followingfertilization,most parentalepigeneticprogrammingiserasedanddramaticepigenomicreprogrammingoccurs[100].Thisresultsintransformationoftheparentalepigenometothezygoteepigenome anddeterminespersonalizedgenefunction.Compellingevidenceshowsthatawiderange ofmaternal,nutritionalandenvironmentalfactorscaneffectfetaldevelopmentduring thesecriticalperiodsofprogramming[44,98,99,101,102].Theseincludehormones,vitamins, diet-derivedmetabolitesandenvironmentalchemicals[48,98,103,104].Inaddition,epigeneticreprogrammingofgerm-linecellscanleadtotransgenerationalinheritanceresulting inphenotypicvariationorpathologyintheabsenceofcontinueddirectexposure[98].

Experimentalstudiesinprimates,sheep,ratsandmiceshowthatPCOS-likesyndromescanbeinducedbyarangeoftreatmentsincludingandrogens,anti-Mullerian hormoneandletrozole[19,44,46].Nevertheless,thereissignificantdebateregardingwhen ananimalmodelqualifiesasPCOS-like[105].Themodelusedandthemethodofinduction ofPCOSphenotypesthereforeneedstobecarefullyscrutinizedwhengeneralizingfindings fromanimalresearchtowomenwithPCOS.Mostoftheanimalandhumanresearchon thedevelopmentaloriginsofPCOShasfocusedontheroleofprenatalandrogenexposure.Thishasbeenextensivelyreviewedinnumerouspreviouspublications[41,46].This researchhasresultedinaproposed“twohit”hypothesisforthedevelopmentofPCOS phenotypes[43,45].The“firsthit”involvesdevelopmentalprogrammingofinheritedsusceptibilitygenesandthe“secondhit”arisesduetolifestyleandenvironmentalinfluences inchildhood,adolescenceandadulthood[41,106].

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 6of25

IfPCOSisaquantitativetraitinvolvingnormalgenevariants,assuggestedbytheevolutionaryconsiderationsandfindingsfromgeneticresearch,thenthe“firsthit”mayresult fromnormaldevelopmentalprogrammingeventsasoccurswithothergenevariants[102]. Accordingtothishypothesis,thepolygenicsusceptibilitygeneswouldbenormally“activated”and“primed”torespondtofuturematernalandenvironmentalconditionsand exposures,aswouldbethecasewithmanyothernormalgenes[28].Inaddition,the susceptibilityallelesmaybe“activated”or“functionallyenhanced”byarangeofmaternal andenvironmentalfactors,asisusuallypresumedtobethecaseinPCOS[5,14,102].This developmentalplasticitywouldprovideamechanismforapredictiveadaptiveresponse, basedoninputsfromthematernalenvironmentthatcouldbeusedtoprogrammetabolic andreproductivesurvivalpathways,tobetterpreparetheoffspringforthefutureworldin whichtheymaybeexpectedtolive[107].

Parentallifestylefactorsincludingdiet,obesity,smokingandendocrine-disrupting chemicals,haveallbeenshowntomodulatediseaserisklaterinlife[104,108,109].The originaldescriptionofthefetalorigin’shypothesisproposedthatpoormaternalnutrition wouldincreasefetalsusceptibilitytotheeffectsofaWestern-styledietlaterinlife[49]. Subsequentstudieshaveconfirmedthatmaternalexposuretoeithernutrientexcessor deficit,canhavelong-termconsequencesforthehealthoftheprogeny[104].Evidence fromhumanandanimalstudiessuggeststhatmaternalobesityprogramstheoffspringfor increasedriskofdevelopingobesity,hyperglycemia,diabetes,hypertensionandmetabolic syndrome[108].

ThedevelopmentaloriginsofPCOSmayhavebeenduetodifferentfactorsinancestral andmodernpopulations[17,60].Ithasbeenhypothesizedthatenvironmentalstress, infection,nutrientdeprivation,fetalgrowthrestrictionandstresshormoneresponses mayhaveresultedinmaternallymediatedmodulationofgeneexpressioninancestral offspring[17,110].Someofthesefactorshavebeeninvestigatedandconfirmedinmodern populationssubjecttostarvationandextremeenvironmentalconditions[111].Incontrast, alteredfetalprogramminginmodernsocietiesmaybesecondarytomaternalovernutrition, sedentarybehavior,obesity,emotionalstress,circadianrhythmdisruption,poorguthealth orenvironmentalchemicalexposure[35,101,112,113].Thepreconceptionandpregnancy periodsthereforeprovideauniqueopportunityforlifestyleinterventionsthatpromote optimalfuturehealthforboththemotherandtheoffspring(Figure 2).

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 7of25

Figure2. Nutritionalandenvironmentalinfluencesthroughoutthelifecourseandtheperpetuation ofthetransgenerationalinheritanceofpolycysticovarysyndrome.ReprintedfromRef.[28].

3.4.MicrobiomeandDysbiosis

Thegastrointestinalmicrobiomeisnowappreciatedtoplayacentralroleinhuman healthanddisease[114,115].Themicrobiomeisknowntoco-regulatemanyphysiological functionsinvolvingtheimmune,neuroendocrineandmetabolicsystemsviacomplex reciprocalfeedbackmechanismsthatoperatebetweenthemicrobialecosystemandthe host[116,117].EvidencefromstudiesinWesternpopulations,hunter–gatherersocieties andphylogeneticstudiesinotherspecies,haveattemptedtoplacethehumanmicrobiome intoanevolutionarycontext[118].Althoughmicrobesclearlyimpacthostphysiologyand havechangedalongbranchesoftheevolutionarytree,thereisongoingdebateregarding whetherthemicrobiomecanevolveaccordingtotheusualevolutionaryforces[119,120]. Nevertheless,ithasbeenarguedthatfocusingonfunctionalpathwaysandmetabolicroles ofmicrobialcommunities,ratherthanonspecificmicrobes,providesabettermodelfor understandingevolutionaryfitness[118].Theco-evolutionofthemicrobiomeandhuman physiologymaythereforebeimportantinunderstandingthedifferencesbetweenancient adaptivephysiologicalsurvivalmechanismsandmodernlifestyle-relatedpathological responses,inwomenwithPCOS(Figure 1).

TwinstudiesandGWASshowthathostgeneticscaninfluencethemicrobiomecomposition,andmicrobescanexerteffectsonthehostgenome,althoughtheenvironmenthas animportantrole[121,122].Humansareconstantlyadaptingtothegutmicrobiometotry todeterminewhichmicroorganismsarebeneficialorharmful.Immunegenesinvolved inthisprocessarethemostrapidlyevolvingprotein-encodinggenesinthemammalian genome[123,124].Diversificationofmicrobesallowshumanstoaccessdietarynichesand nutritionalcomponentstheyotherwisewouldnotbeabletoaccess,whichmaybebeneficialandultimatelyleadtotheintegrationofspecificmicrobesintotheecosystem[125]. Althoughnolivingpopulationtodaycarriesanancestralmicrobiome,comparisonstudiesofnon-WesternandWesternpopulationsshowsignificantdifferencesintherelative abundancesofcommonphylaandamuchgreaterspeciesdiversityinnon-Westernpopulations[126,127].Areviewofnon-humanprimateandhumangutmicrobiomedatasets, revealedachangingmicrobiomeinresponsetohosthabitat,seasonanddiet,although thereappeartobecommonspecies-specificsymbioticcommunities[118].

Rapidhumanculturalchangeshaveresultedinsignificantdietarymodificationsin urban-industrializedcommunitiesandshiftedthemicrobiomeatanunprecedentedrate. Theresulthasbeenthedevelopmentofamismatchbetweenhumanmetabolicgenesand bacteriathatenhancefatstorage[128].Inourevolutionarypast,whennutrientswerescarce, ithasbeentheorizedthathostselectionledtothemaintenanceofmicrobesthatenhance nutrientuptakeorhostenergystorage.However,inthemodernenvironment,wherea high-fat,high-sugar,low-fiberdiethasbecomecommonandeasilyaccessible,integration ofthesemicrobesleadstomaladaptivephysiologicalresponses[40].Formetabolically thriftyindividualswithPCOS,harboringmicrobesthatenhanceenergystorageescalates theevolutionaryconflict,furtheringthedevelopmentofinsulinresistanceandtherefore progressiontoobesityandtype2diabetes[12,129].Furthercompoundingthismaladaptive responseisthelossofmicrobesthatarerequiredtoaccessotherdietaryniches.One exampleisthelossofsymbioticspeciesofTreponemainindividualslivinginurbanindustrializedcommunities[130].Achangefromtheancestralhunter–gathererdiet,where foodsconsumedchangedseasonallyandawidevarietyoffoodcomponentswereeaten,to adietthatissimilaracrossseasonsandsignificantlylessvaried,isanotherlikelycontributor toreduceddiversityofthemicrobiomesofindividualslivinginurbanized–industrialized communities[131].

ThemajorityofwomenwithPCOSareoverweightorobeseandevidenceindicates thatthemicrobiomeofobeseindividualsiscapableofextractingmoreenergyfromthehost dietcomparedwiththemicrobiomeofleanindividuals[132].Thisisthoughttobedriven byanexpansioninpro-inflammatoryspeciesofbacteria,suchas E.coli,andadepletionof anti-inflammatorybacteriasuchas Faecalibacteriumprausnitzii [133,134].Chroniclow-grade

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 8of25

‘metabolic’inflammation,ormeta-inflammation,isaresultofanimbalancedgutmicrobiomethatpromotesthedevelopmentofinsulinresistanceandtype2diabetes[135–137].

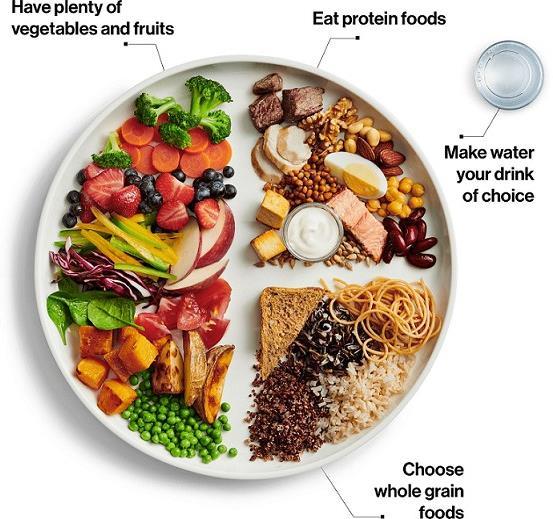

ThedysbiosisofgutmicrobiotatheoryofPCOS,proposedbyTremellenin2012,accountsforthedevelopmentofallofthecomponentsofPCOS(multipleovarianfollicles, anovulationormenstrualirregularityandhyperandrogenism)[40].Thetheoryproposes thatapoor-qualitydietandresultingimbalancedmicrobiome,inducesintestinalpermeabilityandendotoxemia,exacerbatinghyperinsulinemia.Increasedinsulinlevelspromote higherandrogenproductionbytheovariesanddisruptsnormalfollicledevelopment. Metabolic,endocrineandenvironmentalfactorsassociatedwithPCOSarenotmutually exclusive,andthereforetheirrelativecontributionstodysbiosisinPCOSremainsuncertain[138].Consumingabalanceddietthatislowinfatandhighinfiber,canalsorestore balancetotheecosystem(termedeubiosis)[50].Arecentstudyshowedthatdietaryintake offiberandvitaminDwassignificantlydecreasedinbothleanandobesewomenwith PCOS,comparedtohealthycontrols,andcorrelatedwithlowerdiversityofthegutmicrobiome[139].Dysbiosisisreversiblewithimprovementindietqualityaugmentedbythe additionofprobioticsorsynbiotics[51,56–58].

Dysbiosisisaconsistentfindingwhenlookingatthemicrobiomeofwomenwith PCOS[140–143].Althoughmoststudiesaresmall,dysbiosishasconsistentlybeenfound tocorrelatewithdifferentphysiologicalparameters,suchasobesity,sexhormonesand metabolicdefects[140,141,143].Similartomicrobiomesassociatedwithobesity,themicrobiomesofindividualswithPCOShavegenerallybeenfoundtohaveloweralphadiversity (lowernumbersofbacterialtaxa)thancontrols,andmoststudiesdescribeanaltered compositionoftaxarelativetocontrols[140,143].However,thebacterialtaxaobserved tobeeitherincreased,depletedorabsentinPCOSdiffersfromstudytostudy.Thisis likelyduetoboththeimmenseinter-individualvariationinmicrobiotas,aswellthefact thatPCOSisaquantitativetraitwithwomenwithvariousdegreesandlevelsofobesity andsexhormones.

Inkeepingwiththedevelopmentaloriginshypothesispreviouslydiscussed,maternal androgensmayalterthecompositionandfunctionofthemicrobiome,thereforefacilitating thepathogenesisofPCOS[140].Onestudyshowedthatbetadiversity,whichisusedto measuredifferencesbetweengroups,wasnegativelycorrelatedwithhyperandrogenism, suggestingthatandrogensplayasignificantroleindysbiosis[140].The‘firsthit’in uteromaythereforecombinewithverticaltransmissionofadysbioticmicrobiomefroma motherwithPCOS,resultingindysbiosisintheoffspring.Preconceptionandpregnancy provideauniqueopportunitiesforlifestyleanddietaryinterventionsaimedatrestoring eubiosis,toenablethetransferenceofabalancedecosystemtotheoffspring,viavertical transmission[118].

Theaccumulatingscientificevidencestronglysupportsthesignificantroleplayedby themicrobiomeinthepathogenesisandmaintenanceofPCOS,consistentwithresearchin otherrelatedmetabolicconditions.Theroleofdysbiosisissupportedbyover30proof-ofconceptstudiesthathaverecentlybeenreviewed[144].Dysbiosisisthereforeasignificant factorinthepathogenesisofPCOSandanimportantcomponentofaunifiedevolutionary model.Dysbiosisrepresentsamaladaptiveresponseofthemicrobiometomodernlifestyle influencesandisamodifiablefactorinthetreatmentofwomenwithPCOS.

3.5.InsulinResistance

ThereareseveraldilemmaswhenassessingtheroleofIRinwomenwithPCOS. ThereisnoconsensusonthedefinitionofIR[145,146],measurementisdifficult[147,148], whole-bodyIRisusuallymeasuredalthoughitisrecognizedthatIRcanbeselective beingeithertissue-specificorpathway-specificwithincells[149–151],normalvaluesare categoricalanddeterminedbyarbitrarycut-offs(4.45mg/kg/min)[145],testingisnot recommendedinclinicalpractice[38],reportedprevalenceratesinobeseandleanwomen varywidely[147,152],andthesignificanceofIRasapathognomoniccomponentofPCOS isanareaofdebate[153–155].

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 9of25

Despitetheselimitations,itishypothesizedthatIRisasignificantproximatecause ofPCOSandisintrinsictotheunderlyingpathophysiology[44,156].Inaddition,itis recognizedthatIRplaysamajorroleinthepathophysiologyofallofthemetabolicdiseases, cardiovasculardisease,someneurodegenerativediseases,andselectedcancers[22,157]. Insulinresistanceisthereforeconsideredtobethemaindriverformanydiseasesand makesasignificantcontributiontothechronicdiseaseepidemic[158].Nevertheless, beingabletovarythesensitivityandphysiologicalactionofinsulinisthoughttohave conferredasignificantadaptivesurvivalroleinmanyanimalsthroughoutevolutionary history[146,159].IthasbeenproposedthatIRmayhaveevolvedasaswitchinreproductive andmetabolicstrategies,sincethedevelopmentofIRcanresultinanovulationandreduced fertility,inadditiontodifferentialenergyrepartitioningtospecifictissues[159].

Insulinreceptorsarelocatedonthecellmembranesofmosttissuesinthebody[160]. Ligandbindingtothealpha-subunitinducesautophosphorylationofspecifictyrosine residuesonthecytoplasmicsideofthemembrane[160,161].Theactivatedinsulinreceptorinitiatessignaltransductionviathephosphatidylinositol-3kinase(PI-3K)metabolic pathwayandthemitogen-activatedproteinkinasepathway(MAPK)whichisinvolved incellgrowthandproliferation[161].Insulinisananabolichormonethatfacilitates glucoseremovalfromtheblood,enhancesfatstorageandinhibitslipolysisinadipose tissue,stimulatesglycogensynthesisinmuscleandliverandinhibitshepaticglucoseoutput[161].IRcanbedefinedasastatewherehighercirculatinginsulinlevelsarenecessary toachieveanintegratedglucose-loweringresponse[146].IRresultsfromalterationsto cellularmembraneinsulin-receptorfunctionorintracellularsignaling,enzyme,metabolic orgenefunction[146,160,161].

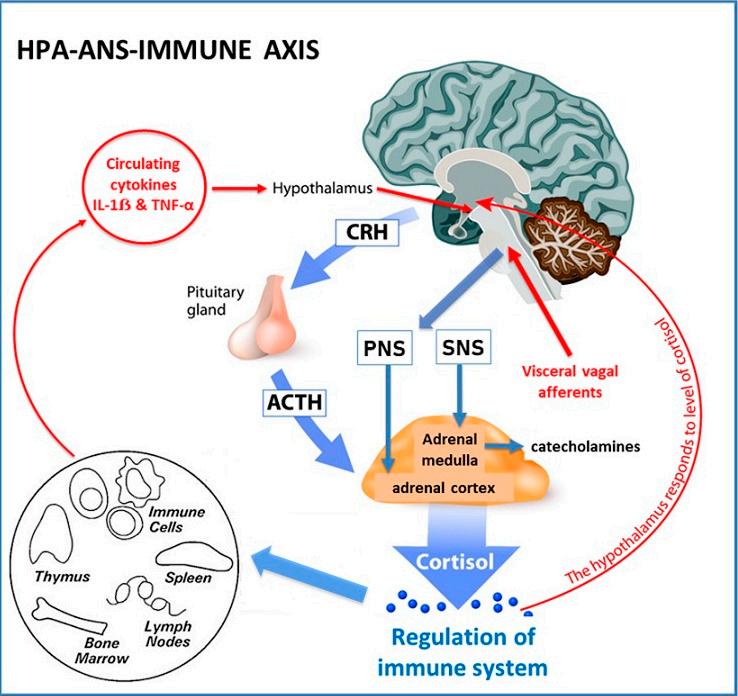

Insulinresistancecanbecausedbyawidevarietyofmechanismsthathavethe abilitytodisruptanypartofthismetabolicsignalingsystem[53,161].Theseinclude autoantibodies,receptoragonistsandantagonists,hormones,inflammatorycytokines, oxidativestress,nutrientsensorsandmetabolicintermediates[160–163].Physiological regulationofinsulinfunctioncanbeviewedasanadaptivemechanismtoregulatethe metabolicpathwayofinsulinsignaling(PI-3K),inresponsetochangingenvironmental conditions[starvation,fear,stress][164,165]orduringnormalalterationsofinternalstates (pregnancy,lactation,adolescence)[65,146,152].

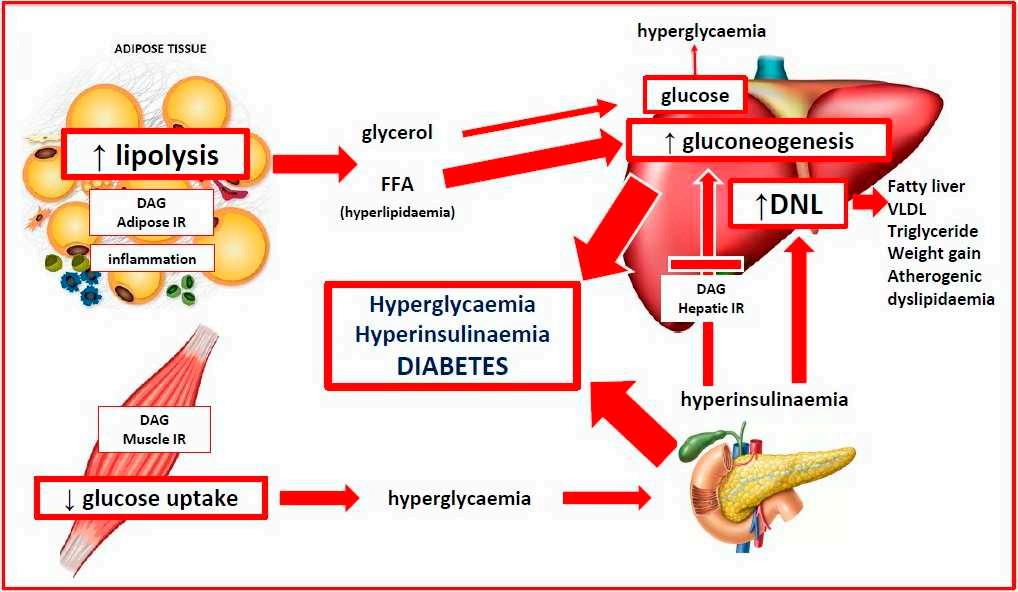

ThephysiologicalactivationofIRallowstheorganismtoswitchfromananabolic energystoragestatetoacatabolicorenergymobilizingstate.Thisallowsfreefattyacids tobemobilizedfromadiposetissue,whicharethenconvertedtoglucoseintheliver andreleasedintothecirculation[161].Asaresultofthismetabolicchange,bloodsugar levelsaremaintainedforvitalmetabolicprocessesandbrainfunction[14].Thisadaptive protectivemechanismcanbepathway-specificduringperiodsofgrowth,suchaspregnancy, lactationandadolescence,sothatonlythemetabolicsignaling(PI-3K)isinhibitedandnot themitogenicpathway(MAPK),whichmayevenbeup-regulated[30,65,160].

Whenthephysiologyofinsulinfunctionisconsideredtobeaquantitativeorcontinuousvariablefromanevolutionaryperspective,itislikelythatallwomenwithPCOS, whetherobeseorlean,havereducedinsulinsensitivity[152,155,166].Asystematicreview andmeta-analysisofeuglycemic-hyperinsulinemicclampstudiesfoundthatwomenwith PCOShavea27%reductionininsulinsensitivitycomparedtobodymassindex(BMI)and age-matchedcontrols[155].Inevolutionaryterms,womenwithaPCOSmetabolicphenotypewouldhaveincreasedsurvivalchancesduringtimesofenvironmentalorphysiological demandforalteredenergymetabolism,butbemorevulnerabletothepathologicaleffects ofIRwhenexposedtomodernlifestylefactors[14,17,159].Inparticular,apoor-quality, high-glycemic,high-fat,low-fiberdiethasbeenshowntocauseIR[40,167].Asdiscussed inthedysbiosissection,diet-relatedchangesinthegastrointestinalmicrobiomehavealso beenshowntocauseIRinwomenwithPCOS[53,55].Numerousstudieshaveshownthat dietarymodification[168–170],ortreatmentwithprobioticsorsynbiotics,hasthepotential torestorenormalinsulinfunction[57,171].

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 10of25

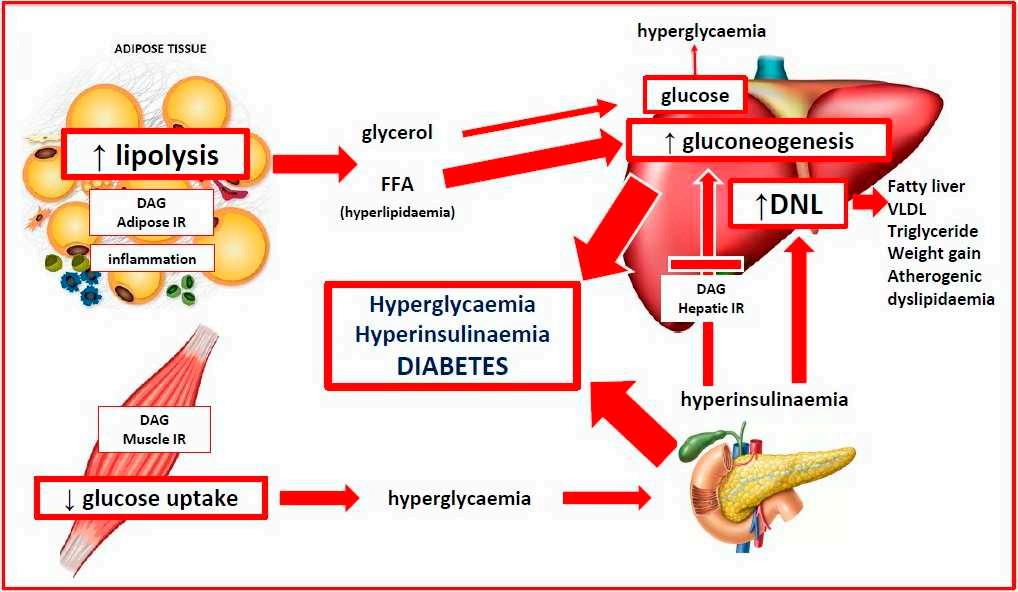

Consumptionofahigh-glycemic-loaddietresultsinrapidincreasesinbloodsugar levelsthatcausecompensatoryhyperinsulinemia[167,172].Excessivedietaryintakeof glucoseandfructoseareconvertedtofattyacidsbydenovolipogenesisintheliver, transportedtoadipocytesvialipoproteins,releasedasfattyacidstoadipocytesandstored infatglobulesastriglycerides[161].Asaresultofnutrientoverload,diacylglycerol,the penultimatemoleculeinthesynthesisoftriglyceride,accumulatesinthecytoplasmand bindswiththethreonineaminoacidinthe1160positionoftheinsulinreceptor.Thisinhibits autophosphorylationanddown-regulatesthemetabolicPI-3KpathwayandcausesIR[161]. Thisprocesshasthepotentialtobereversiblefollowingchangesindietquantityandquality, ashasbeenshowntooccurwithcalorierestriction,fasting,time-restrictedeating,gastric bypasssurgery,lowsaturatedfatandlowglycemicdiets[168,170,173].Dietshighinanimal proteinorsaturatedfatcanalsocauseIRindependentofBMI[174,175].Thesemechanisms providetherationalefortheprincipalrecommendationoftheInternationalGuidelines thatwomenwithPCOSshouldbeadvisedaboutdietarymodificationasthefirstlineof managementinallsymptompresentations[38].

3.6.ObesityandtheLeanPCOSParadox

InsightcanbeobtainedintotheroleofobesityinwomenwithPCOSbyexaminingtheevolutionaryhistory,geneticstudiesandpathologicaldisordersofadipose tissue[151,176,177].Theabilitytostoreenergyisabasicfunctionoflifebeginningwith unicellularorganisms[176].Inmulticellularorganisms,fromyeasttohumans,thelargest sourceofstoredenergyisastriglyceridesinlipiddropletsinordertoprovideenergyduring periodswhenenergydemandsexceedcaloricintake[176].Understandingthebiological functionsofadiposetissuehasprogressedfromenergystorageandthermalinsulationto thatofacomplexendocrineorganwithimmuneandinflammatoryeffectsandimportant reproductiveandmetabolicimplications[176,178].

Adiposetissueisorganizedintobrownadiposetissue(BAT)andwhiteadiposetissue (WAT),bothwithdifferentfunctions[178].AlthoughtheevolutionaryoriginsofBATand WATarethesubjectofongoingdebate[176],BATislocatedinthesupraclavicularand thoracicprevertebralareasandisprimarilyinvolvedincoldthermogenesisandregulation ofbasalmetabolicrate[179].WATisdistributedinmultipleanatomicalareassuchas visceraladiposetissue(VAT)andsubcutaneousadiposetissue(SAT)andfunctionsasa fatstoragedepotandanendocrineorgan[178,179].AnadditionallayerofSATisthought tohaveevolvedasinsulationagainstcoolnighttemperaturesinthePleistoceneopenSavanah[180].ThelowerbodydistributionofSATinwomenishypothesizedtohaveevolved toprovideadditionalcaloriestorageforpregnancyandlactationandisuniquetohuman females[14].LowerbodySAThasametabolicprogramthatmakesitlessreadilyavailable forevery-dayenergyneeds,butitcanbemobilizedduringpregnancyandlactation[14]. Inaddition,excessaccumulationofSATismuchlesslikelytocauseIRandmetabolic dysfunctionandexplainswhyIRisnotobservedinallobese individuals[151,181].Visceral WATisassociatedwithIRinwomenwithPCOSleadingtobothmetabolicandreproductive problems[182].

Multiplelinesofevidencefromevolutionaryhistory,geneticandtwinstudies,support ageneticbasisforobesityanddifferencesinobeseandleanphenotypesinwomenwith PCOS[183–186].ThemajorityofwomenwithPCOSareoverweightorobese,withreports rangingfrom38–88%[152,186].StudiescomparingobeseandleanwomenwithPCOShave severalmethodologicalproblemsincludingsmallsamplesize,overlapofPCOScharacteristicswithnormalpubertalchanges,non-standardizeddiagnosticcriteria,andlimited generalizabilitytotheentirepopulationduetoafocusonaspecificethnicgroup[166,182]. Inaddition,mostofthestudiesexaminingbodycompositioninPCOShavereliedon anthropomorphicmeasurements(BMI,waistcircumference,waist-to-hipratio)whichare consideredinaccuratecomparedwiththecurrentgold-standardofmagneticresonance imaging[182].Consequently,thereiswideheterogeneityinreportsexaminingtherelation-

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 11of25

shipbetweenbodycompositionmeasures,includingextentofVATandmetabolicchanges suchasIR[186].

Inhumans,thereislargeindividualvariationinthefatstoragecapabilityandexpandabilityofdifferentadiposetissuedepots[151].Ithasbeenhypothesizedthatonce thegeneticallydeterminedlimitofexpandabilityofSATisreached,thereisexpansion ofVATandexcesslipidaccumulationinmuscle,liverandotherorgans,resultinginIR, inflammationandmetabolicdysregulation[151].Wehypothesizethatleanwomenwith PCOShaveageneticallydeterminedlimitedabilitytostoreexcesslipidinSAT,butdevelop increasedlipiddepositioninVATandorganssuchastheliver,resultinginmetabolic dysregulationandIRinasimilarmannertowhatoccursinobesewomenwithPCOS.The widevariationinthegeneticlimitationofSATexpansionisalsosupportedbystudiesin individualswithlipodystrophy.

Lipodystrophiesareaheterogenousgroupofrareinheritedandacquireddisorders characterizedbyaselectivelossofadiposetissue[177,187].Theyareclassifiedonthebasis oftheextentoffatlossasgeneralized,partialorlocalized[187].Patientswithcongenital generalizedlipodystrophyhaveageneralizeddeficiencyoffatfrombirth,usuallyhave severeIRanddevelopdiabetesatpuberty.Asaconsequenceofgeneticallylimitedability forSATlipidstorage,lipidscanonlybestoredectopicallyinnon-adipocytesresultingin majorhealthconsequencesincludingIR,fattyliver,diabetesandPCOS[188].Incontrast togeneralizedlipodystrophy,patientswithfamilialpartiallipodystrophyhavenormal fatdistributionatbirthbutlooseSATinthelimbs,buttocksandhips,atpuberty.Fifty percentofwomendevelopdiabetesand20–35%developirregularperiodsandpolycystic ovaries[177].Despitetherarenatureofthesesyndromesmuchhasbeenlearnedaboutthe underlyinggeneticvariantsinvolved[187].

Elucidationofclinicalsubtypesandthegeneticbackgroundofpatientswithlipodystrophiesmaypavethewaytonewinsightsintotheroleoffatpartitioningandobesity,and hasimplicationsforunderstandingthepathogenesisofinsulinresistance,diabetesand PCOS[177].LeanwomenwithPCOSmayhaveageneticpredispositionforlimitedSAT fatstorage,coupledwithunderlyingmetabolicpredispositionsthatresultindeposition ofexcesslipidinVATandliverandtheobservedmetabolicfeaturesofIR,fattyliverand diabetes.IftheextentofIRandectopicfatdepositionisexcessive,theresultinghormonal changesmaybesufficienttocauseoligomenorrhoeaandsubfertilityasoccurswithsecondaryfamilialpartiallipodystrophytype2[188,189].Ifthisunderlyingmechanismis confirmedinfuturestudies,themaindifferencebetweenwomenwithleanorobesePCOS maybethecombinedeffectsofmetabolicprogrammingandthegeneticallydetermined extentofSCTfatdeposition.Thiswouldexplainwhyleanwomenhaveallthesameclinical, biochemicalandendocrinefeatures,althoughpossiblylesssevere,thanoverweightand obesewomenwithPCOS[186].

3.7.Endocrine-DisruptingChemicalExposure

Anthropomorphicchemicalexposureisubiquitousintheenvironmentandhaspossibleeffectsonmanyaspectsrelatedtowomen’shealthandPCOS[36,190–192].The identificationofmorethan1000EDCinfood,air,water,pesticides,plastics,personalcare products,andotherconsumergoods,raisesspecificconcernsforpregnantwomenand womenwithincreasedsusceptibilitytometabolicdiseasessuchasPCOS[36,172,192–194]. AccumulatingevidencesuggeststhatEDCmaybeinvolvedinthepathogenesisofPCOS giventheirknownandpotentialhormonalandmetaboliceffects[36,190,195].Thisincludes manyoftheareasthathavebeenconsideredintheunifiedevolutionarymodel,suchas developmentalepigeneticprogramming,microbiomecompositionandfunction,metabolic processessuchIR,andregulationofbodyweight.

ManyobservationalstudieshavedemonstratedthepresenceofEDCinmaternaland fetalserumandurine,amnioticfluid,cordbloodandbreastmilk[196–198].Sixclasses ofEDChavebeenshowntocrosstheplacentaconfirmingthatthefetusisexposedatall stagesofdevelopment[109,196].Althoughitisimpossibletoperformexperimentalstudies

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 12of25

inhumans,evidencefromepidemiological,moleculartoxicologyandanimalstudies providecompellingevidenceofadversedevelopmentaleffectsandtransgenerational toxicity[172,190,192,199].TherealizationofthetragiceffectsofDESinthe1970′ swasfirst exampleofaninuteroexposurecausingserioustransgenerationalhealtheffects[192].

SeveralestrogenicEDChavebeenassociatedwithbirthoutcomesthatarethoughttobe associatedwiththedevelopmentofPCOS[190].Theseincludedecreasedbirthweight(perfluoroakylsubstances[PFAS],perfluorooctanoicacid)andpretermbirth(di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate)[190].PrenatalexposuretoandrogenicEDC(triclosan,glyphosate,tributyltin, nicotine)isofincreasingconcern,giventhesuspectedepigeneticroleofinuteroandrogen exposureinthepathogenesisofPCOS[48,200,201].

Asaresult,implementationoftheprecautionaryprincipleisahighpriorityincounsellingwomenwithPCOS[202].Internationalprofessionalbodies(TheRoyalCollegeof ObstetriciansandGynecologists,EndocrineSociety,FIGO)haverecommendedthatallpregnantwomenshouldbeadvisedofthepossiblerisksofEDCandthateducationprogramsbe developedtoinformhealthprofessionals[203–205].Anexplanationofthepathogenesisof PCOSshouldincludereferencetoenvironmentalchemicalexposureandopenthewayfor moredetaileddiscussionofspecificpersonalizedadviceandlifestylerecommendations.

3.8.LifestyleContributorstothePathogenesisofPCOS

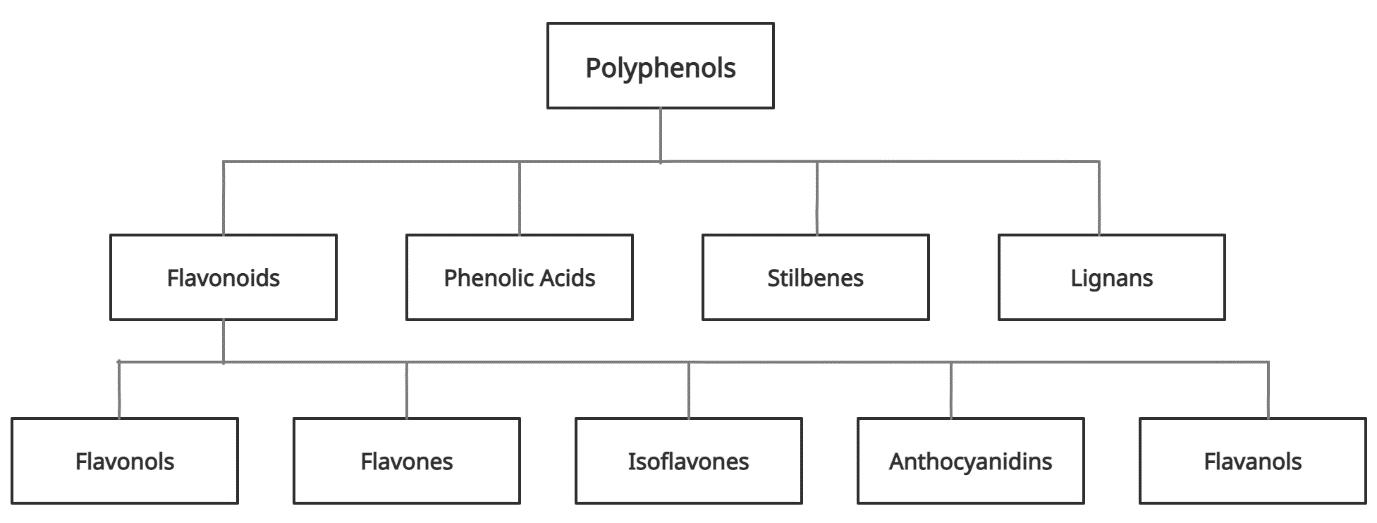

Severallifestylefactorshavebeeninvestigatedfortheirroleinthepathogenesis ofPCOS.Theseincludediet,exercise,stress,sleepdisturbance,circadiandisruptionand exposuretoenvironmentalchemicals[28,41,206].Recentadvancesingenomics,epigenetics, metabolomics,nutrigenomics,evolutionarybiology,computertechnologyandartificial intelligence,areprovidingmanyinsightsintothemechanismsofhowlifestylefactors impactthepathogenesisofPCOS[9,90,207,208].Nutritionalstudiesbasedondietindices, dietcompositionandmetabolomicshaveidentifieddietarycomponentsthatcontribute toahealthyeatingpattern[51,207,209,210].Healthydietpatterns,orwholefooddiets, havebeenfoundtobeeffectiveincontrollingandreversingmanyofthesymptomsand metabolicalterationsassociatedwithPCOS[50].

Aspreviouslydiscussed,themodernWesterndietandlifestyleisatoddswithour evolutionarybackground.Onedietarycomponentthatdifferssignificantlyinancestral andmodernpopulationsisdietaryfiberintake.Assessmentofdietaryfiberintakeisalsoa goodsurrogatemarkerforahealthywholefooddiet.Ingeneral,ourtraditionalhunter–gathererancestorsconsumedsignificantlymorefiberthanmodernpopulations.Studies thathaveinvestigatedthedietarypatternsofremainingcontemporaryhunter–gatherer societies,havefoundtheirdietaryfiberintaketobearound80–150gperday[211].This contrastswiththecontemporaryWesterndiet,wheretheaveragefiberintakeis18.2gper dayinchildrenand20.7gperdayinadults[212].Adequatedietaryfiberconsumptionis importantasithasseveralbenefits,suchasimprovedinsulinsensitivity,reducedblood glucoselevels,decreasedsystemicinflammation,lowerserumlevelsofandrogensandLPS, allofwhichhavebeenlinkedtothepathogenesisofPCOS[213–216].

Recentsystematicreviewsofobservationalstudiesandrandomizedcontrolledtrialshave founddietaryfiberconsumptiontobeinverselyrelatedtoriskofobesity, type2diabetes, andcardiovasculardisease[217,218].ArecentcohortstudyfromCanadafoundthat obesewomenwithPCOSconsumedsignificantlylessdietaryfiberthannormalweight womenwithoutPCOS[219].Inaddition,fiberintakeofwomenwithPCOSwasnegatively correlatedwithIR,fastinginsulin,glucosetoleranceandserumandrogens[219].Hence, themismatchbetweentheamountoffibertraditionallyconsumedandthefibercontentof Westerndiets,maybeanimportantdietarycomponentcontributingtotheincreasedrates ofPCOSseenindevelopedanddevelopingnations.

3.9.CircadianRhythmDisruptionandPCOS

Thecircadianrhythmisamechanismwithwhichlivingorganismscansynchronize theirinternalbiologicalprocesseswiththeexternallightanddarkpatternoftheday[220].

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 13of25

Circadianrhythmshaveformedacentralcomponentoftheevolutionaryadaptationofall organismstoavarietyofenvironmentalconditions,fromprocaryotestocomplexmulticellularorganisms[221–223].Mostorganismsexperiencedailychangesintheirenvironment, includinglightavailability,temperatureandfood.Hundredsofthousandsofyearsof evolutionhavesynchronizedtherhythmicdailyprogrammingofinternalmetabolic,endocrineandbehavioralsystemstotheexternalenvironmentalconditions[222].Circadian clocksanticipateenvironmentalchangesandconferapredictiveadaptivesurvivalbenefit toorganisms.

Thenormalfunctionofthecircadiansystemisbasedonahierarchicalnetworkof centralandperipheralclocks[224].Thecentral,ormasterclock,isinthesuprachiasmicnucleusintheanteriorhypothalamus.Itisstrategicallyplacedtocommunicatewithmultiple physiologicalhomeostaticcontrolnuclei(bodytemperature,metabolicrate,appetite,sleep), pituitaryhormonalsystems(gonadal,thyroid,somatotrophic,adrenal),theautonomic nervoussystem(digestion,heartrate),andconsciouscorticalcenters(behavior,motivation, reward,reproduction)[225].Humansareprogrammedforspecificdayandnight-timesurvivalbehaviorsthatareregulatedbytheavailabilityoftemperature,feedingandsunlight. Photonsoflightstimulatespecializedphotoreceptorsintheretinalganglionlayerwhich transmitanelectricalimpulsetothecellsofthemasterclockviatheretinohypothalamic tract[226].Thecentralclockcanthenconveyrhythmicinformationtoperipheralclocks inothertissuesandorgansthroughoutthebody[224].Feedingandfastingcyclesarethe primarytimecuesforcircadianclocksinperipheraltissues[227].

Circadianclocksexistinallcells,includingthemicrobiome,andfunctionasautonomoustranscriptional-translationalgeneticfeedbackloops[228,229].Thechanging lengthofdaylight,determinedbytherotationoftheearthonitsaxis,requiresthatthe autonomousclocksarereset,orentrained,onadailybasis[230].Themolecularmechanismsofcircadianclocksaresimilaracrossallspeciesandareregulatedbygenetic enhancer/repressorelements,epigeneticmodulationbymethylationandacetylation,posttranslationmodificationofregulatoryproteins,andavarietyofhormonalandsignaling molecules[220,229,231].Thiscomplexinterconnectedregulatoryframework,ensuresthat thesamemoleculesthatregulatemetabolismandreproduction,alsocontributetoabidirectionalfeedbacksystemwiththeautonomouscircadiancircuits[224,231].Thisresultsin synchronicityofinternalphysiologywithenvironmentalcues,tooptimizebothindividual andspeciessurvival.Evolutionhasthereforeprovidedamechanismforhumanstoadapt andsurviveundertheselectivepressuresoffoodscarcity,seasonalchangesinsunlightand arangeoftemperatureexposures.

Theevolutionaryadaptivesurvivalbenefitofsynchronizedcircadiansystemsin ancientpopulationsisinmarkedcontrasttothemultiplecircadiandisruptionsthatare associatedwithmodernlifestyle.Theseincludepoor-qualitydiet[232],impropermeal timingandalteredfeeding-fastingbehavior[233,234],sub-optimalexercisetiming[235],disruptedsleep-wakecycles[236],shiftwork[237],EDC[238],andstress[239,240].Changes inalloftheseparametersarecorrelatedwithsignificantincreasesinobesity,diabetes, cardiovasculardisease,andsomecancers[222].Notsurprisingly,lifestyle-relateddisturbancesofcircadianrhythmshavealsobeeninvestigatedfortheirroleinthepathogenesisofPCOS[35,241,242].Theavailableevidencesuggeststhatcircadiandisruptionhas detrimentaleffectsoninuterodevelopment[243],alteredmetabolismandinsulinresistance[241,244],bodyweightandobesity[245],andfertility[34].Alltheseinfluencesare relevanttoanevolutionarymodelofthepathogenesisofPCOS.

Recognitionoftheimpactoflifestylebehaviorsoncircadiandysregulationand metabolicandreproductivefunction,opensthewayfortargetedinterventionstrategies tomodulateandreversetheseeffects[246].Theseincluderegularmealtiming[222,247], time-restrictedfeeding[248,249],restorationofnormalsleepcycles[250],optimalexercisetiming[235],limitationofexposuretobrightlightatnight[251],andimproveddiet quality[227].RecognitionofcircadiandysfunctionandtheinvestigationoflifestyleinterventionsshouldbeapriorityinbothclinicalmanagementandfutureresearchinPCOS.

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 14of25

3.10.ConceptualFrameworkandSummaryoftheUnifiedEvolutionaryModel

TheevolutionarymodelproposesthatPCOSisaconditionthatarisesfromtheinheritanceofgenomicvariantsderivedfromthematernalandpaternalgenome.Inuterofetal metabolic,endocrineandenvironmentalfactorsmodulatedevelopmentalprogrammingof susceptiblegenesandpredisposetheoffspringtodevelopPCOS.Postnatalexposureto poor-qualitydiet,sedentarybehavior,EDC,circadiandisruptionandotherlifestylefactors activateepigeneticallyprogrammedpathways,resultingintheobservedfeatures.

Dietaryfactorscausegastrointestinaldysbiosisandsystemicinflammation,insulin resistanceandhyperandrogenism.Continuedexposuretoadverselifestyleandenvironmentalfactorseventuallyleadstothedevelopmentofassociatedmetabolicconditionssuch asobesity,GDM,diabetes,NAFLDandmetabolicsyndrome(Figure 1).

Balancedevolutionaryselectionpressuresresultintransgenerationaltransmissionof susceptiblegenevariantstoPCOSoffspring.Ongoingexposuretoadversenutritionaland environmentalfactorsactivatedevelopmentallyprogrammedgenesandensuretheperpetuationofthesyndromeinsubsequentgenerations.TheDOHaDcyclecanbeinterrupted atanypointfrompregnancytobirth,childhood,adolescenceoradulthoodbytargeted interventionstrategies(Figure 2).

Insummary,weproposethatPCOSisanenvironmentalmismatchdisorderthat manifestsafterinuterodevelopmentalprogrammingofaclusterofnormalgenevariants. Postnatalexposuretoadverselifestyleandenvironmentalconditionsresultsintheobserved metabolicandendocrinefeatures.PCOSthereforerepresentsamaladaptiveresponseof ancientgeneticsurvivalmechanismstomodernlifestylepractices.

ComprehensiveInternationalGuidelineshavemade166recommendationsforthe assessmentandmanagementofPCOS[38].Webelievethecurrentunifiedevolutionary theoryofthepathogenesisofPCOSprovidesaconceptualframeworkthatmayhelp practitionersandpatientsunderstandthedevelopmentofPCOSsymptomsandpathology inthecontextofourmodernlifestyleandenvironment.Itwillhopefullycontributeto improvedcommunication,resultinimprovedfeelingsofempowermentoverthepersonal manifestationsofPCOS,improvecompliance,reducemorbidity,increasequalityoflifeand informfutureresearch(Figure 3).

4.Conclusions

Substantialevidenceanddiscussionsupportanevolutionarybasisforthepathogenesisofpolycysticovarysyndrome,althoughmanyofthemechanisticdetailsareyetto

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 15of25

Figure3. Impactoftheunifiedtheoryonthemanagementofpolycysticovarysyndrome.Reprinted fromRef.[28].

bedetermined.Nevertheless,multiplelinesofevidencefromevolutionarytheory,comparativebiology,genetics,epigenetics,metabolismresearch,andcellbiology,provide supportiveevidenceandhypothesis-generatingdata.Theabilityofanimalstosynchronize internalphysiology,metabolismandreproductivefunction,withourchangingexternal environmentandhabitat,areanecessaryrequirementforindividualandspeciessurvival. Theco-operativeandsometimescompetitiveevolutionofmetabolismandreproduction providedadaptivesurvivalmechanismsinancestralenvironmentsthatappeartobemaladaptiveinmodernenvironments.Anevolutionarymodelthereforeprovidesaframework toenhancepractitionerandpatientunderstanding,improvecompliancewithlifestyleinterventions,reducemorbidity,improvequalityoflifeandwillevolveandchangeovertime.

AuthorContributions: J.P.conceptualized,designedandwrotetheoriginaldraftofthemanuscript; C.O.conceptualization,writing,reviewedandeditedthemanuscript;J.H.conceptualization,writing, reviewedandeditedthemanuscript;F.L.G.conceptualized,reviewed,editedandsignificantly improvedthemanuscript.Allauthorscriticallyrevisedthemanuscript.Allauthorshavereadand agreedtothepublishedversionofthemanuscript.

Funding: Thisresearchreceivednoexternalfunding.

InstitutionalReviewBoardStatement: Notapplicable.

InformedConsentStatement: Notapplicable.

DataAvailabilityStatement: Notapplicable.

Acknowledgments: PermissiontoreprintFigures 1–3 wereobtainedfromtheJournaloftheAustralasianCollegeofNutritionalandEnvironmentalMedicine.

ConflictsofInterest: Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictofinterest.

References

1. Bodai,B.I.;Nakata,T.E.;Wong,W.T.;Clark,D.R.;Lawenda,S.;Tsou,C.;Liu,R.;Shiue,L.;Cooper,N.;Rehbein,M.;etal.Lifestyle Medicine:ABriefReviewofItsDramaticImpactonHealthandSurvival. Perm.J. 2017, 22,17–25.[CrossRef][PubMed]

2. McMacken,M.;Shah,S.Aplant-baseddietforthepreventionandtreatmentoftype2diabetes. J.Geriatr.Cardiol. 2017, 14, 342–354.[CrossRef][PubMed]

3. Gakidou,E.;Afshin,A.;Abajobir,A.A.;Abate,K.H.;Abbafati,C.;Abbas,K.M.;Abd-Allah,F.;Abdulle,A.M.;Abera,S.F.; Aboyans,V.;etal.Global,regional,andnationalcomparativeriskassessmentof84behavioural,environmentalandoccupational, andmetabolicrisksorclustersofrisks,1990–2016:AsystematicanalysisfortheGlobalBurdenofDiseaseStudy2016. Lancet 2017, 390,1345–1422.[CrossRef]

4. Parker,J.NEM:ANewParadigmforUnderstandingtheCommonOriginsoftheChronicDiseaseEpidemic. ACNEMJ. 2018, 37,6–11.

5. Glastras,S.J.;Valvi,D.;Bansal,A.Editorial:Developmentalprogrammingofmetabolicdiseases. Front.Endocrinol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

6. Zore,T.;Joshi,N.V.;Lizneva,D.;Azziz,R.PolycysticOvarianSyndrome:Long-TermHealthConsequences. Semin.Reprod.Med. 2017, 35,271–281.[CrossRef]

7. Teede,H.;Misso,M.;Costello,M.;Dokras,A.;Laven,J.;Moran,L.;Piltonen,T.;Norman,R. InternationalEvidence-BasedGuideline fortheAssessmentandManagementofPolycysticOvarySyndrome2018;NationalHealthandMedicalResearchCouncil[NHMRC]: Canberra,Australia,2018;pp.1–198;ISBN9780646554709.

8.Benton,M.L.Theinfluenceofevolutionaryhistoryonhumanhealthanddisease. Nat.Rev.Genet. 2021, 22,269–283.[CrossRef]

9. Painter,D.Theevolutionofevolutionarymedicine.In TheDynamicsofScience:ComputationalFrontiersinHistoryandPhilosophyof Science;PittsburghUniversityPress:Pittsburgh,PA,USA,2020.

10.Fay,J.C.Diseaseconsequencesofhumanadaptation. Appl.Transl.Genom. 2013, 2,42–47.[CrossRef]

11. Pathak,G.;Nichter,M.PolycysticovarysyndromeinglobalizingIndia:Anecosocialperspectiveonanemerginglifestyledisease. Soc.Sci.Med. 2015, 146,21–28.[CrossRef]

12. Parker,J.;O’Brien,C.Evolutionaryandgeneticantecedentstothepathogenesisofpolycysticovarysyndrome[PCOS]. J.ACNEM 2021, 40,12–20.

13. Stearns,S.C.Evolutionarymedicine:Itsscope,interestandpotential. Proc.R.Soc.BBiol.Sci. 2012, 279,4305–4321.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

14. Tsatsoulis,A.;Mantzaris,M.D.;Sofia,B.;Andrikoula,M.Insulinresistance:Anadaptivemechanismbecomesmaladaptiveinthe currentenvironment—Anevolutionaryperspective. Metabolism 2013, 62,622–633.[CrossRef][PubMed]

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 16of25

15. Shaw,L.M.A.;Elton,S.Polycysticovarysyndrome:Atransgenerationalevolutionaryadaptation. BJOGInt.J.Obstet.Gynaecol. 2008, 115,144–148.[CrossRef][PubMed]

16. Charifson,M.A.;Trumble,B.C.Evolutionaryoriginsofpolycysticovarysyndrome:Anenvironmentalmismatchdisorder. Evol.Med.PublicHealth 2019, 2019,50–63.[CrossRef]

17. Azziz,R.;Dumesic,D.A.;Goodarzi,M.O.Polycysticovarysyndrome:Anancientdisorder? Fertil.Steril. 2011, 95,1544–1548. [CrossRef]

18. Teede,H.;Deeks,H.;Moran,L.Polycysticovarysyndrome:Acomplexconditionwithpsychological,reproductiveandmetabolic manifestationsthatimpactsonhealthacrossthelifespan. BMCMed. 2010, 8,41.[CrossRef]

19. Sanchez-Garrido,M.A.;Tena-Sempere,M.Metabolicdysfunctioninpolycysticovarysyndrome:Pathogenicroleofandrogen excessandpotentialtherapeuticstrategies. Mol.Metab. 2020, 35,100937.[CrossRef]

20. Glueck,C.J.;Goldenberg,N.Characteristicsofobesityinpolycysticovarysyndrome:Etiology,treatment,andgenetics. Metabolism 2019, 92,108–120.[CrossRef]

21. Reyes-Muñoz,E.;Castellanos-Barroso,G.;Ramírez-Eugenio,B.Y.;Ortega-González,C.;Parra,A.;Castillo-Mora,A.;DeLa Jara-Díaz,J.F.TheriskofgestationaldiabetesmellitusamongMexicanwomenwithahistoryofinfertilityandpolycysticovary syndrome. Fertil.Steril. 2012, 97,1467–1471.[CrossRef]

22. Rodgers,R.J.;Avery,J.C.;Moore,V.M.;Davies,M.J.;Azziz,R.;Stener-Victorin,E.;Moran,L.J.;Robertson,S.A.;Stepto,N.K.;Norman,R.J.;etal.Complexdiseasesandco-morbidities:Polycysticovarysyndromeandtype2diabetesmellitus. Endocr.Connect. 2019, 8,R71–R75.[CrossRef]

23. Wu,J.;Yao,X.Y.;Shi,R.X.;Liu,S.F.;Wang,X.Y.Apotentiallinkbetweenpolycysticovarysyndromeandnon-alcoholicfattyliver disease:Anupdatemeta-analysis. Reprod.Health 2018, 15,77.[CrossRef][PubMed]

24. Yumiceba,V.;López-Cortés,A.;Pérez-Villa,A.;Yumiseba,I.;Guerrero,S.;García-Cárdenas,J.M.;Armendáriz-Castillo,I.;GuevaraRamírez,P.;Leone,P.E.;Zambrano,A.K.;etal.OncologyandPharmacogenomicsInsightsinPolycysticOvarySyndrome:An IntegrativeAnalysis. Front.Endocrinol. 2020, 11,840.[CrossRef][PubMed]

25. Li,G.;Hu,J.;Zhang,S.;Fan,W.;Wen,L.;Wang,G.;Zhang,D.ChangesinResting-StateCerebralActivityinWomenWith PolycysticOvarySyndrome:AFunctionalMRImagingStudy. Front.Endocrinol. 2020, 11,981.[CrossRef][PubMed]

26. Cooper,H.;Spellacy,W.N.;Prem,K.A.;Cohen,W.D.HereditaryfactorsintheSteinleventhal1968. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1968, 100,371–387.[CrossRef]

27. Diamanti-Kandarakis,E.;Piperi,C.Geneticsofpolycysticovarysyndrome:Searchingforthewayoutofthelabyrinth. Hum.Reprod.Update 2005, 11,631–643.[CrossRef][PubMed]

28. Parker,J.UnderstandingthePathogenesisofPolycysticOvarySyndrome:Atransgenerationalevolutionaryadaptationtolifestyle andtheenvironment. ACNEMJ. 2020, 39,18–26.

29. Day,F.;Karaderi,T.;Jones,M.R.;Meun,C.;He,C.;Drong,A.;Kraft,P.;Lin,N.;Huang,H.;Broer,L.;etal.Large-scale genome-widemeta-analysisofpolycysticovarysyndromesuggestssharedgeneticarchitecturefordifferentdiagnosiscriteria. PLoSGenet. 2018, 14,e1007813.[CrossRef]

30. Crespo,R.P.;Bachega,T.A.S.S.;Mendonça,B.B.;Gomes,L.G.AnupdateofgeneticbasisofPCOSpathogenesis. Arch.Endocrinol.Metab. 2018, 62,352–361.[CrossRef]

31. Jones,M.R.;Goodarzi,M.O.Geneticdeterminantsofpolycysticovarysyndrome:Progressandfuturedirections. Fertil.Steril. 2016, 106,25–32.[CrossRef]

32. Varanasi,L.C.;Subasinghe,A.;Jayasinghe,Y.L.;Callegari,E.T.;Garland,S.M.;Gorelik,A.;Wark,J.D.Polycysticovariansyndrome: PrevalenceandimpactonthewellbeingofAustralianwomenaged16–29years. Aust.N.Z.J.Obstet.Gynaecol. 2018, 58,222–233. [CrossRef]

33. Ding,T.;Hardiman,P.J.;Petersen,I.;Wang,F.F.;Qu,F.;Baio,G.Theprevalenceofpolycysticovarysyndromeinreproductiveaged womenofdifferentethnicity:Asystematicreviewandmeta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8,96351–96358.[CrossRef][PubMed]

34. Shao,S.;Zhao,H.;Lu,Z.;Lei,X.;Zhang,Y.Circadianrhythmswithinthefemalehpgaxis:Fromphysiologytoetiology. Endocrinology 2021, 162,bqab117.[CrossRef][PubMed]

35. Wang,F.;Xie,N.;Wu,Y.;Zhang,Q.;Zhu,Y.;Dai,M.;Zhou,J.;Pan,J.;Tang,M.;Cheng,Q.;etal.Associationbetweencircadian rhythmdisruptionandpolycysticovarysyndrome. Fertil.Steril. 2021, 115,771–781.[CrossRef][PubMed]

36. Piazza,M.J.;Urbanetz,A.A.Environmentaltoxinsandtheimpactofotherendocrinedisruptingchemicalsinwomen’sreproductivehealth. J.Bras.Reprod.Assist. 2019, 23,154–164.[CrossRef][PubMed]

37. Basu,B.;Chowdhury,O.;Saha,S.Possiblelinkbetweenstress-relatedfactorsandalteredbodycompositioninwomenwith polycysticovariansyndrome. J.Hum.Reprod.Sci. 2018, 11,10–18.[CrossRef]

38. Teede,H.J.;Misso,M.L.;Costello,M.F.;Dokras,A.;Laven,J.;Moran,L.;Piltonen,T.;Norman,R.J.;Andersen,M.;Azziz,R.;etal. Recommendationsfromtheinternationalevidence-basedguidelinefortheassessmentandmanagementofpolycysticovary syndrome. Fertil.Steril. 2018, 110,364–379.[CrossRef]

39. Casarini,L.;Simoni,M.;Brigante,G.Ispolycysticovarysyndromeasexualconflict?Areview. Reprod.Biomed.Online 2016, 32, 350–361.[CrossRef]

40. Tremellen,K.;Pearce,K.DysbiosisofGutMicrobiota[DOGMA]—AnoveltheoryforthedevelopmentofPolycysticOvarian Syndrome. Med.Hypotheses 2012, 79,104–112.[CrossRef]

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 17of25

41. Parker,J.;O’Brien,C.;Gersh,F.L.Developmentaloriginsandtransgenerationalinheritanceofpolycysticovarysyndrome. Aust.N.Z.J.Obstet.Gynaecol. 2021, 61,922–926.[CrossRef]

42. Abbott,D.H.;Dumesic,D.A.;Franks,S.Developmentaloriginofpolycysticovarysyndrome—Ahypothesis. J.Endocrinol. 2002, 174,1–5.[CrossRef]

43. Rosenfield,R.L.;Ehrmann,D.A.ThePathogenesisofPolycysticOvarySyndrome[PCOS]:ThehypothesisofPCOSasfunctional ovarianhyperandrogenismrevisited. Endocr.Rev. 2016, 37,467–520.[CrossRef]

44. Stener-Victorin,E.;Padmanabhan,V.;Walters,K.A.;Campbell,R.E.;Benrick,A.;Giacobini,P.;Dumesic,D.A.;Abbott,D.H. AnimalModelstoUnderstandtheEtiologyandPathophysiologyofPolycysticOvarySyndrome. Endocr.Rev. 2020, 41,538–576. [CrossRef][PubMed]

45. Abbott,D.H.;Dumesic,D.A.;Abbott,D.H.Fetalandrogenexcessprovidesadevelopmentaloriginforpolycysticovarysyndrome. ExpertRev.Obs.Gynecol. 2009, 4,1–7.[CrossRef]

46. Abbott,D.H.;Kraynak,M.;Dumesic,D.A.;Levine,J.E.InuteroAndrogenExcess:ADevelopmentalCommonalityPreceding PolycysticOvarySyndrome? Front.Horm.Res. 2019, 53,1–17.[CrossRef][PubMed]

47. Abbott,D.H.;Rayome,B.H.;Dumesic,D.A.;Lewis,K.C.;Edwards,A.K.;Wallen,K.;Wilson,M.E.;Appt,S.E.;Levine,J.E. ClusteringofPCOS-liketraitsinnaturallyhyperandrogenicfemalerhesusmonkeys. Hum.Reprod. 2017, 32,923–936.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

48. Hewlett,M.;Chow,E.;Aschengrau,A.;Mahalingaiah,S.PrenatalExposuretoEndocrineDisruptors:ADevelopmentalEtiology forPolycysticOvarySyndrome. Reprod.Sci. 2017, 24,19–27.[CrossRef]

49.Neel,J.V.DiabetesMellitis:A“thrifty”genotyperendereddetrimentalby“progress”? Am.J.Hum.Genet. 1962, 14,353–362.

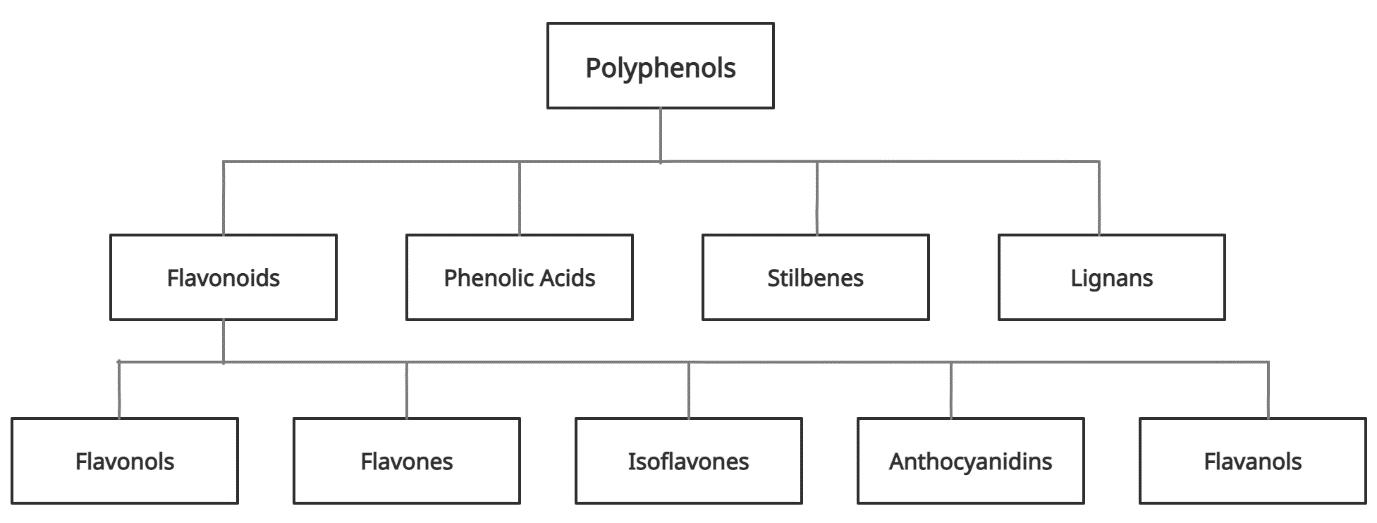

50. Parker,J.;Hawrelak,J.;Gersh,F.L.Nutritionalroleofpolyphenolsasacomponentofawholefooddietinthemanagementof polycysticovarysyndrome. J.ACNEM 2021, 40,6–12.

51. Tremellen,K.P.K.Nutrition,Fertility,andHumanReproductiveFunction.In Nutrition,Fertility,andHumanReproductiveFunction; CRCPress:Adelaide,Astralia,2015;pp.27–50.

52. Rizk,M.G.;Thackray,V.G.IntersectionofPolycysticOvarySyndromeandtheGutMicrobiome. J.Endocr.Soc. 2021, 5,bvaa177. [CrossRef]

53. He,F.F.;Li,Y.M.Roleofgutmicrobiotainthedevelopmentofinsulinresistanceandthemechanismunderlyingpolycysticovary syndrome:Areview. J.OvarianRes. 2020, 13,73.[CrossRef]

54. Chen,F.Analysisofthegutmicrobialcompositioninpolycysticovarysyndromewithacne. ZigongMatern.ChildHealthHosp. 2019, 35,2246–2251.

55. Zhou,L.;Ni,Z.;Cheng,W.;Yu,J.;Sun,S.;Zhai,D.;Yu,C.;Cai,Z.Characteristicgutmicrobiotaandpredictedmetabolicfunctions inwomenwithPCOS. Endocr.Connect. 2020, 9,63–73.[CrossRef][PubMed]

56. Tabrizi,R.;Ostadmohammadi,V.;Akbari,M.;Lankarani,K.B.;Vakili,S.;Peymani,P.;Karamali,M.;Kolahdooz,F.;Asemi,Z. TheEffectsofProbioticSupplementationonClinicalSymptom,WeightLoss,GlycemicControl,LipidandHormonalProfiles, BiomarkersofInflammation,andOxidativeStressinWomenwithPolycysticOvarySyndrome:ASystematicReviewand Meta-analysisofRa. ProbioticsAntimicrob.Proteins 2019,1–14.[CrossRef][PubMed]

57. Darvishi,S.;Rafraf,M.;Asghari-Jafarabadi,M.;Farzadi,L.SynbioticSupplementationImprovesMetabolicFactorsandObesity ValuesinWomenwithPolycysticOvarySyndromeIndependentofAffectingApelinLevels:ARandomizedDouble-Blind Placebo-ControlledClinicalTrial. Int.J.Fertil.Steril. 2021, 15,51–59.[CrossRef][PubMed]

58. Karimi,E.;Moini,A.;Yaseri,M.;Shirzad,N.;Sepidarkish,M.;Hossein-Boroujerdi,M.;Hosseinzadeh-Attar,M.J.Effectsof synbioticsupplementationonmetabolicparametersandapelininwomenwithpolycysticovarysyndrome:Arandomised double-blindplacebo-controlledtrial. Br.J.Nutr. 2018, 119,398–406.[CrossRef][PubMed]

59. Stein,I.F.;Leventhal,M.L.Amenorrheaassociatedwithbilateralpolycysticovaries. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 1935, 29,181–191. [CrossRef]

60. Corbett,S.;Morin-Papunen,L.ThePolycysticOvarySyndromeandrecenthumanevolution. Mol.Cell.Endocrinol. 2013, 373, 39–50.[CrossRef]

61. Rodgers,R.J.;Suturina,L.;Lizneva,D.;Davies,M.J.;Hummitzsch,K.;Irving-Rodgers,H.F.;Robertson,S.A.Ispolycysticovary syndromea20thCenturyphenomenon? Med.Hypotheses 2019, 124,31–34.[CrossRef]

62. Holte,J.Polycysticovarysyndromeandinsulinresistance:Thriftygenesstrugglingwithover-feedingandsedentarylifestyle? J.Endocrinol.Investig. 1998, 21,589–601.[CrossRef]

63. Corbett,S.J.;McMichael,A.J.;Prentice,A.M.Type2diabetes,cardiovasculardisease,andtheevolutionaryparadoxofthe polycysticovarysyndrome:Afertilityfirsthypothesis. Am.J.Hum.Biol. 2009, 21,587–598.[CrossRef]

64. Dinsdale,N.L.;Crespi,B.J.Endometriosisandpolycysticovarysyndromearediametricdisorders. Evol.Appl. 2021, 14,1693–1715. [CrossRef][PubMed]

65.Sonagra,A.D.NormalPregnancy—AStateofInsulinResistance. J.Clin.DiagnosticRes. 2014, 8,CC01.[CrossRef][PubMed]

66. Lipovka,Y.;Chen,H.;Vagner,J.;Price,T.J.;Tsao,T.S.;Konhilas,J.P.Oestrogenreceptorsinteractwiththe α-catalyticsubunitof AMP-activatedproteinkinase. Biosci.Rep. 2015, 35,e00264.[CrossRef]

67. López,M.;Tena-Sempere,M.EstradioleffectsonhypothalamicAMPKandBATthermogenesis:Agatewayforobesitytreatment? Pharmacol.Ther. 2017, 178,109–122.[CrossRef][PubMed]

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 18of25

68. Rettberg,J.R.;Yao,J.;Brinton,R.D.Estrogen:Amasterregulatorofbioenergeticsystemsinthebrainandbody. Front.Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 35,8–30.[CrossRef][PubMed]

69. Alaaraj,N.;Soliman,A.;Hamed,N.;Alyafei,F.;DeSanctis,V.Understandingthecomplexroleofmtorcasanintracellularcritical mediatorofwhole-bodymetabolisminanorexianervosa:Aminireview. ActaBiomed. 2021, 92,e2021170.[CrossRef][PubMed]

70. Seif,M.W.;Diamond,K.;Nickkho-Amiry,M.Obesityandmenstrualdisorders. BestPract.Res.Clin.Obstet.Gynaecol. 2015, 29, 516–527.[CrossRef]

71. Draper,C.F.;Duisters,K.;Weger,B.;Chakrabarti,A.;Harms,A.C.;Brennan,L.;Hankemeier,T.;Goulet,L.;Konz,T.;Martin,F.P.; etal.Menstrualcyclerhythmicity:Metabolicpatternsinhealthywomen. Sci.Rep. 2018, 8,14568.[CrossRef]

72. Roh,E.;Song,D.K.;Kim,M.S.Emergingroleofthebraininthehomeostaticregulationofenergyandglucosemetabolism. Exp.Mol.Med. 2016, 48,e216.[CrossRef]

73.Ong,Q.;Han,W.;Yang,X.O-GlcNAcasanintegratorofsignalingpathways. Front.Endocrinol. 2018, 9,599.[CrossRef]

74. Gnocchi,D.;Bruscalupi,G.Circadianrhythmsandhormonalhomeostasis:Pathophysiologicalimplications. Biology 2017, 6,10. [CrossRef][PubMed]

75. Ludwig,D.S.;Aronne,L.J.;Astrup,A.;deCabo,R.;Cantley,L.C.;Friedman,M.I.;Heymsfield,S.B.;Johnson,J.D.;King,J.C.; Krauss,R.M.;etal.Thecarbohydrate-insulinmodel:Aphysiologicalperspectiveontheobesitypandemic. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2021, 114,1873–1885.[CrossRef]

76. Gluckman,P.D.;Hanson,M.A.Developmentalandepigeneticpathwaystoobesity:Anevolutionary-developmentalperspective. Int.J.Obes. 2008, 32,S62–S71.[CrossRef][PubMed]

77. Balakumar,P.;Maung-U,K.;Jagadeesh,G.Prevalenceandpreventionofcardiovasculardiseaseanddiabetesmellitus. Pharmacol.Res. 2016, 113,600–609.[CrossRef]

78. Crosignani,P.G.;Nicolosi,A.E.Polycysticovarydisease:Heritabilityandheterogeneity. Hum.Reprod.Update 2001, 7,3–7. [CrossRef][PubMed]

79. Vink,J.M.;Sadrzadeh,S.;Lambalk,C.B.;Boomsma,D.I.HeritabilityofpolycysticovarysyndromeinaDutchtwin-familystudy. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2006, 91,2100–2104.[CrossRef][PubMed]

80. Kahsar-Miller,M.D.;Nixon,C.;Boots,L.R.;Go,R.C.;Azziz,R.Prevalenceofpolycysticovarysyndrome[PCOS]infirst-degree relativesofpatientswithPCOS. Fertil.Steril. 2001, 75,53–58.[CrossRef]

81. Dunaif,A.Perspectivesinpolycysticovarysyndrome:Fromhairtoeternity. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2016, 101,759–768. [CrossRef]

82.Kosova,G.;Urbanek,M.Geneticsofthepolycysticovarysyndrome. Mol.Cell.Endocrinol. 2013, 373,29–38.[CrossRef]

83. Legro,R.S.;Driscoll,D.;Strauss,J.F.;Fox,J.;Dunaif,A.Evidenceforageneticbasisforhyperandrogenemiainpolycysticovary syndrome. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA 1998, 95,14956–14960.[CrossRef]

84. Lander,E.S.;Linton,L.M.;Birren,B.;Nusbaum,C.;Zody,M.C.;Baldwin,J.;Devon,K.;Dewar,K.;Doyle,M.;Fitzhugh,W.;etal. Initialsequencingandanalysisofthehumangenome:InternationalHumanGenomeSequencingConsortium. Nature 2001, 409, 860–921,Erratumin Nature 2001, 411,720.[CrossRef]

85. Belmont,J.W.;Boudreau,A.;Leal,S.M.;Hardenbol,P.;Pasternak,S.;Wheeler,D.A.;Willis,T.D.;Yu,F.;Yang,H.;Gao,Y.;etal.A haplotypemapofthehumangenome. Nature 2005, 437,1299–1320.[CrossRef]

86. Welt,C.K.GeneticsofPolycysticOvarySyndrome:WhatisNew? Endocrinol.Metab.Clin.N.Am. 2021, 50,71–82.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

87. Chen,Z.J.;Zhao,H.;He,L.;Shi,Y.;Qin,Y.;Shi,Y.;Li,Z.;You,L.;Zhao,J.;Liu,J.;etal.Genome-wideassociationstudyidentifies susceptibilitylociforpolycysticovarysyndromeonchromosome2p16.3,2p21and9q33.3. Nat.Genet. 2011, 43,55–59.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

88. Hayes,M.G.;Urbanek,M.;Ehrmann,D.A.;Armstrong,L.L.;Lee,J.Y.;Sisk,R.;Karaderi,T.;Barber,T.M.;McCarthy,M.I.;Franks, S.;etal.Genome-wideassociationofpolycysticovarysyndromeimplicatesalterationsingonadotropinsecretioninEuropean ancestrypopulations. Nat.Commun. 2015, 6,7502.[CrossRef][PubMed]

89. Zhang,Y.;Ho,K.;Keaton,J.M.;Hartzel,D.N.;Day,F.;Justice,A.E.;Josyula,N.S.;Pendergrass,S.A.;Actkins,K.E.;Davis,L.K.;etal. Agenome-wideassociationstudyofpolycysticovarysyndromeidentifiedfromelectronichealthrecords. Am.J.Obstet.Gynecol. 2020, 223,559.e1–559.e21.[CrossRef]

90. Zhu,T.;Goodarzi,M.O.Causesandconsequencesofpolycysticovarysyndrome:InsightsfromMendelianRandomization. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2021.[CrossRef]

91. Sun,Q.;Gao,Y.;Yang,J.;Lu,J.;Feng,W.;Yang,W.MendelianRandomizationAnalysisIdentifiedPotentialGenesPleiotropically AssociatedwithPolycysticOvarySyndrome. Reprod.Sci. 2021,1–10.[CrossRef]

92. Visscher,P.M.;Brown,M.A.;McCarthy,M.I.;Yang,J.FiveyearsofGWASdiscovery. Am.J.Hum.Genet. 2012, 90,7–24.[CrossRef]

93. Zhu,Z.;Zhang,F.;Hu,H.;Bakshi,A.;Robinson,M.R.;Powell,J.E.;Montgomery,G.W.;Goddard,M.E.;Wray,N.R.;Visscher, P.M.;etal.IntegrationofsummarydatafromGWASandeQTLstudiespredictscomplextraitgenetargets. Nat.Genet. 2016, 48, 481–487.[CrossRef]

94. Rung,J.;Cauchi,S.;Albrechtsen,A.;Shen,L.;Rocheleau,G.;Cavalcanti-Proença,C.;Bacot,F.;Balkau,B.;Belisle,A.;BorchJohnsen,K.;etal.GeneticvariantnearIRS1isassociatedwithtype2diabetes,insulinresistanceandhyperinsulinemia. Nat.Genet. 2009, 41,1110–1115.[CrossRef][PubMed]

Int.J.Environ.Res.PublicHealth 2022, 19,1336 19of25

95. Udler,M.S.;McCarthy,M.I.;Florez,J.C.;Mahajan,A.GeneticRiskScoresforDiabetesDiagnosisandPrecisionMedicine. Endocr.Rev. 2019, 40,1500–1520.[CrossRef][PubMed]

96. Khera,A.V.;Chaffin,M.;Wade,K.H.;Zahid,S.;Brancale,J.;Xia,R.;Distefano,M.;Senol-Cosar,O.;Haas,M.E.;Bick,A.;etal. PolygenicPredictionofWeightandObesityTrajectoriesfromBirthtoAdulthood. Cell 2019, 177,587–596.e9.[CrossRef]

97. Plomin,R.;Haworth,C.M.A.;Davis,O.S.P.Commondisordersarequantitativetraits. Nat.Rev.Genet. 2009, 10,872–878. [CrossRef][PubMed]

98. Dumesic,D.A.;Hoyos,L.R.;Chazenbalk,G.D.;Naik,R.;Padmanabhan,V.;Abbott,D.H.Mechanismsofintergenerational transmissionofovarysyndrome. Reproduction 2020, 159,R1–R13.[CrossRef][PubMed]

99. Sloboda,D.M.;Hickey,M.;Hart,R.Reproductioninfemales:Theroleoftheearlylifeenvironment. Hum.Reprod.Update 2011, 17, 210–227.[CrossRef][PubMed]

100. Xu,R.;Li,C.;Liu,X.;Gao,S.Insightsintoepigeneticpatternsinmammalianearlyembryos. ProteinCell 2021, 12,7–28.[CrossRef] [PubMed]

101. Glastras,S.J.;Chen,H.;Pollock,C.A.;Saad,S.Maternalobesityincreasestheriskofmetabolicdiseaseandimpactsrenalhealthin offspring. Biosci.Rep. 2018, 38,BSR20180050.[CrossRef][PubMed]

102. Simeoni,U.;Armengaud,J.B.;Siddeek,B.;Tolsa,J.F.PerinatalOriginsofAdultDisease. Neonatology 2018, 113,393–399.[CrossRef]

103. Risnes,K.;Bilsteen,J.F.;Brown,P.;Pulakka,A.;Andersen,A.M.N.;Opdahl,S.;Kajantie,E.;Sandin,S.MortalityAmongYoung AdultsBornPretermandEarlyTermin4NordicNations. JAMANetw.Open 2021, 4,e2032779.[CrossRef]

104. Behere,R.V.;Deshmukh,A.S.;Otiv,S.;Gupte,M.D.;Yajnik,C.S.MaternalVitaminB12StatusDuringPregnancyandIts AssociationWithOutcomesofPregnancyandHealthoftheOffspring:ASystematicReviewandImplicationsforPolicyinIndia. Front.Endocrinol. 2021, 12,288.[CrossRef][PubMed]

105.Azziz,R.Animalmodelsofpcosnottherealthing. Nat.Rev.Endocrinol. 2017, 13,382–384.[CrossRef][PubMed]

106. Poon,K.BehavioralFeedingCircuit:DietaryFat-InducedEffectsofInflammatoryMediatorsintheHypothalamus. Front.Endocrinol. 2020, 11,905.[CrossRef][PubMed]

107. Bateson,P.;Gluckman,P.;Hanson,M.ThebiologyofdevelopmentalplasticityandthePredictiveAdaptiveResponsehypothesis. J.Physiol. 2014, 592,2357–2368.[CrossRef][PubMed]

108. Catalano,P.M.;Presley,L.;Minium,J.;Mouzon,S.H.DeFetusesofobesemothersdevelopinsulinresistanceinutero. DiabetesCare 2009, 32,1076–1080.[CrossRef][PubMed]

109. Rosenfeld,C.S.TranscriptomicsandOtherOmicsApproachestoInvestigateEffectsofXenobioticsonthePlacenta. Front.CellDev.Biol. 2021, 9,723656.[CrossRef]

110. DeMelo,A.S.;Dias,S.V.;DeCarvalhoCavalli,R.;Cardoso,V.C.;Bettiol,H.;Barbieri,M.A.;Ferriani,R.A.;Vieira,C.S.Pathogenesis ofpolycysticovarysyndrome:Multifactorialassessmentfromthefoetalstagetomenopause. Reproduction 2015, 150,R11–R24. [CrossRef]

111. Schulz,L.C.TheDutchhungerwinterandthedevelopmentaloriginsofhealthanddisease. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA 2010, 107, 16757–16758.[CrossRef]

112. Gaillard,R.Maternalobesityduringpregnancyandcardiovasculardevelopmentanddiseaseintheoffspring. Eur.J.Epidemiol. 2015, 30,1141–1152.[CrossRef]

113. Ishimwe,J.A.Maternalmicrobiomeinpreeclampsiapathophysiologyandimplicationsonoffspringhealth. Physiol.Rep. 2021, 9, e14875.[CrossRef]

114.Gilbert,J.A.;Blaser,M.J.;Caporaso,J.G.;Jansson,J.K.;Lynch,S.V.;Knight,R.Currentunderstandingofthehumanmicrobiome. Nat.Med. 2018, 24,392–400.[CrossRef][PubMed]

115. Valdes,A.M.;Walter,J.;Segal,E.;Spector,T.D.Roleofthegutmicrobiotainnutritionandhealth. BMJ 2018, 361,36–44.[CrossRef]

116. Rinninella,E.;Raoul,P.;Cintoni,M.;Franceschi,F.;Miggiano,G.A.D.;Gasbarrini,A.;Mele,M.C.Whatisthehealthygut microbiotacomposition?Achangingecosystemacrossage,environment,diet,anddiseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7,14. [CrossRef][PubMed]

117. Schmidt,T.S.B.;Raes,J.;Bork,P.TheHumanGutMicrobiome:FromAssociationtoModulation. Cell 2018, 172,1198–1215. [CrossRef]

118. Davenport,E.R.;Sanders,J.G.;Song,S.J.;Amato,K.R.;Clark,A.G.;Knight,R.Thehumanmicrobiomeinevolution. BMCBiol. 2017, 15,127.[CrossRef]

119. Theis,K.R.;Dheilly,N.M.;Klassen,J.L.;Brucker,R.M.;Baines,J.F.;Bosch,T.C.G.;Cryan,J.F.;Gilbert,S.F.;Goodnight,C.J.;Lloyd, E.A.;etal.GettingtheHologenomeConceptRight:AnEco-EvolutionaryFrameworkforHostsandTheirMicrobiomes. mSystems 2016, 1,e00028-16.[CrossRef][PubMed]

120. Douglas,A.E.;Werren,J.H.Holesinthehologenome:Whyhost-microbesymbiosesarenotholobionts. mBio 2016, 7,e02099-15. [CrossRef]

121. Goodrich,J.K.;Davenport,E.R.;Beaumont,M.;Jackson,M.A.;Knight,R.;Ober,C.;Spector,T.D.;Bell,J.T.;Clark,A.G.;Ley,R.E. GeneticDeterminantsoftheGutMicrobiomeinUKTwins. CellHostMicrobe 2016, 19,731–743.[CrossRef]