By Sophie Levenson Sports Managing Editor

By Sophie Levenson Sports Managing Editor

In the walkway off the basketball court in Atlanta’s Georgia Dome, John Feinstein was making a scene.

He had just found out that the media at the 2013 NCAA men’s basketball Final Four had been moved out of courtside seats. The NCAA figured it could make a pretty dollar pushing journalists several rows up and selling those coveted courtside seats as tickets — a preposterous idea to Feinstein, which he made very clear to the unlucky tournament official he found in the hallway between the court and the media room.

Feinstein’s indignation, if expressed poorly, was not unwarranted. If there was a writer who harnessed national attention for college sports, it was Feinstein. He wanted a good view of the game, and he was not used to taking no for an answer.

Feinstein was stubborn and easy to anger. It is easy to find people who hated working with him, or with whom he never agreed. But it is difficult to find anyone who did not respect Feinstein. He cared about what he cared about as passionately as anyone in the world. He spent 51 of his 69 years devoted to sports writing, publishing more than 40 books and hundreds of articles. His book “A Season on the Brink” formed lines of eager buyers down city blocks upon its 1986 release.

He committed to Duke to swim, but lasted roughly one practice with head coach Jack Persons before deciding to refocus his efforts toward writing. Maybe editors are easier to argue with than coaches.

Ann Pelham, Trinity ‘74 and editor-inchief in 1973-74, welcomed him to the office when he first found it, and encouraged him to write about both news and sports. Feinstein did, “reluctantly and briefly,” Pelham said in a message to The Chronicle, before abandoning news to direct all of his energy to sports.

Between 1973-74, Feinstein lived in Wannamaker House I right next to Paul Honigberg, who had also joined The Chronicle’s sports staff. Their junior year, the department voted Feinstein sports editor and Honigberg assistant sports editor. Anne Newman, then a senior, was their editor-in-chief. None of them were best friends. Honigberg and Newman, like most people, were not like Feinstein.

“It’s probably a good thing our offices were separated by a hallway and the newsroom,” Newman said in an email.

I hope that those who follow me here [at The Chronicle], as writers, as students and as people will receive and return the same kind of help I have received.

JOHN FEINSTEIN

Former Chronicle Sports Editor

“I was an outspoken feminist, and he was, well … John. One day I called him our own Howard Cosell, referring to the famously obnoxious sports broadcaster. I think he took it as a compliment.”

Honigberg spent his time outside the office with his fraternity brothers. Feinstein moved off campus at the start of his sophomore year and hung out with his cat, Venus. He called him “Veni.”

“Consider the Source,” while freelancing and stringing. As a sophomore, he started calling George Solomon, The Washington Post’s sports editor, to pitch ACC basketball stories. Solomon would concede, mostly because he got tired of the phone ringing.

Feinstein edited a small-but-mighty sports staff for two years.

A Duke courseload on top of editing is no small task, but Feinstein’s ability to work was unmatched.

When his internship ended, the Post’s Metro desk — then headed by Bob Woodward — hired him. Feinstein’s professional career began because of a dramatic love for sports and a determination to understand the people involved with them. But he conquered the shift to non-sports reporting, too. He built relationships with police officers (covering night cops) much like he had built them with coaches.

You want [a reporter] to be aggressive and tough and maybe overbearing. Get the story. He was a star.

BOB WOODWARD

He was a tough but fair editor. He didn’t write over his reporters, though it must have been tempting for a guy who took his own convictions as fact. Instead, he taught them how to be better. He would remind Honigberg that he was writing too much like a fan, when this was supposed to be serious stuff. His critiques were helpful, his compliments treasured.

Feinstein’s former editor

“The police liked him,” Solomon said. “He was there all the time.”

Solomon loved him and so did Woodward, but other editors could not stand Feinstein’s abrasive behavior. One editor in particular, Woodward said, repeatedly tried to fire Feinstein for “being Feinstein.” Woodward would not allow this.

John Feinstein died March 13. He and his career — which might have been the same thing — began at The Chronicle.

The Chronicle’s office on Duke’s campus sprawls across the top floor of a building tucked between the Duke Chapel, dining hall and auditorium. It has for about 70 years. Feinstein had to walk up three steep flights of stairs to get to his first newspaper office. Like most things in his work life, they could not discourage him.

That was where Feinstein started writing about the thing he had always loved.

“Sports have been an important part of my life for as long as I can remember,” he wrote in his senior Chronicle column. “When I was little if my parents wanted to punish me they wouldn’t let me watch the Mets or the Jets on the television.”

But the two young men were always together, toting typewriters across ACC territory to write game stories, sharing late meals at the Cambridge Inn — a snack bar on campus — and watching nights in the office become early mornings. Feinstein drove them to football and basketball games in a beat-up Pontiac Bonneville. Honigberg would wait for him in the press box after they filed their stories for The Chronicle because local papers around North Carolina paid Feinstein to sling college sports for them. He would hook up the portable fax machine that “usually worked” to the telephone line and send his stories.

Feinstein was virtually as prolific in college as he was in his professional career. He often wrote more than one story a day for The Chronicle, along with his weekly column,

“When you wrote a good one, and he said, ‘This is really good,’ or, ‘You asked a really good question’ … you felt like it meant something,” Honigberg told The Chronicle.

“You couldn’t help [but] love him while he was hell-bent on making his way in the world,” Newman said.

His senior year — still sports editor — he would argue with Howard Goldberg, the 197677 editor-in-chief, about the length of his pieces.

“He pounded out these disproportionately long stories on a typewriter with astounding speed and refused to trim them, insisting people on the University campus would read every word,” Goldberg wrote in “Connecting,” the AP retiree newsletter.

Goldberg stopped trying to control their length when Feinstein threatened to throw him out of a window. The Chronicle’s offices are on the third floor.

Feinstein made The Chronicle a better paper. He wrote about athletes, coaches and fans. He wrote about sports with a hard focus on the people inhabiting them. He wrote with an irreverence seasoned by dry humor.

Previewing the men’s basketball ACC Tournament in March 1975, Feinstein wrote, “Then at 8 p.m., after the Duke-Clemson clash and several cocktail parties for the moneyed gentry that will be in attendance…” A few months later, he wrote that Duke football fans “in recent years have found themselves sitting around waiting for the roof to fall in.” In December 1975, after the season had ended, he wrote, “There was excitement in the ACC this season, but even though conference fans don’t like to admit it most of the football was pretty mediocre.”

When Harsha Murthy started working for The Chronicle in the fall of 1977, Feinstein had just graduated. Already legendary at 22, however, he had not really left the building.

“There was that tradition that John had established of going out and getting the story,” Murthy said.

While Murthy and his peers worked to uphold the standard set by Feinstein, he was busy arguing his way into stories in Washington. Solomon hired Feinstein as an intern for the Post when he graduated from Duke. In 1977, just a few years after breaking the Watergate scandal and publishing the Pentagon Papers, the Post was full of journalism giants of the present and future. They fazed young Feinstein for one day.

“And then he became Feinstein,” Solomon said.

“You want somebody to be aggressive and tough and maybe overbearing. Get the story,” Woodward said. “He was a star. You never … fire your star.”

So Woodward told the editor he would file a personnel report on Feinstein, which seemed to appease her. She complained again, and was satisfied with another report. The Post, at the time, did not actually have a personnel department, so the “reports” went nowhere. For Woodward, Feinstein’s results demanded that the Post kept him as long as it could.

Feinstein went back to sports under Solomon when the job opened up. Sports writing was serious journalism for Feinstein; the subject of his story became the most important person in the world, whether it was Mike Krzyzewski or a minor league baseball player.

Maybe that drove his competitive instincts. Maybe they originated from his days as an athlete. Perhaps they came from his family.

Feinstein’s father was a serious man. Martin Feinstein was born in Brooklyn to Jewish-Russian immigrant parents. He was an army man, and then a music man, working for famed impresario Sol Hurok before taking over as executive director of the Kennedy Center the year before his son started at Duke. When John was in high school at Columbia Grammar, Martin moved from New York to Washington, D.C. Martin Feinstein married three times; John twice.

Young Feinstein “was as competitive as any competitive ball player,” according to David Remnick, who bore witness to it as a sports reporter working alongside Feinstein in the early 1980s. At the Post, they called Feinstein “Junior,” because that was what people called John McEnroe, the star tennis player famous for his terrible temper.

Remnick liked Feinstein. He found him funny, maybe because he understood the humor of a middle-class Jewish boy from New York. He did great impressions. Of Dean Smith, of Solomon.

Not everyone found him so funny. He was direct, often rude. He believed his opinion to be fact; he listened to arguments, but rarely, if ever, changed his mind. Sometimes he would argue with colleagues or editors and they wouldn’t speak for months.

Barry Svrluga, a Duke graduate and sports writer at the Post, said Feinstein “wasn’t afraid to throw an elbow to get past the PR person.”

By Tyler Walley Associate Editor

Generational talent is nothing new for Duke basketball. The men’s program has yielded eight Naismith National Players of the Year, while the women’s team has produced WNBA champions like Lexie Brown and Chelsea Gray. Despite this, it is rare for both teams to simultaneously have a mercurial freshman on their rosters.

However, the stars have seemingly aligned on the 2024-25 Duke basketball season. Two freshmen from the 44th parallel — Newport, Maine’s Cooper Flagg and Toronto’s Toby Fournier — have made a strong case as the best men’s-women’s freshman duo in Duke’s storied history. Flagg and Fournier were both named ACC Rookie of the Year, just the third time that both programs have won the conference’s newcomer award in the same year. How have they improved this year, and what is in store for them as the NCAA Tournament begins?

Cooper Flagg: Improved efficiency and consistent defense

In a previous column published Jan. 4, I wrote that Cooper Flagg needed to work on his

outside shooting while taking more shots in the paint. Since Duke’s Dec. 31 win against Virginia Tech, Flagg has played exceptional basketball, averaging 20.4 points, 6.8 rebounds and 4.5 assists per game on 53.1% shooting. He has shot 36.8% from 3-point range on the season and continues to dominate in the paint.

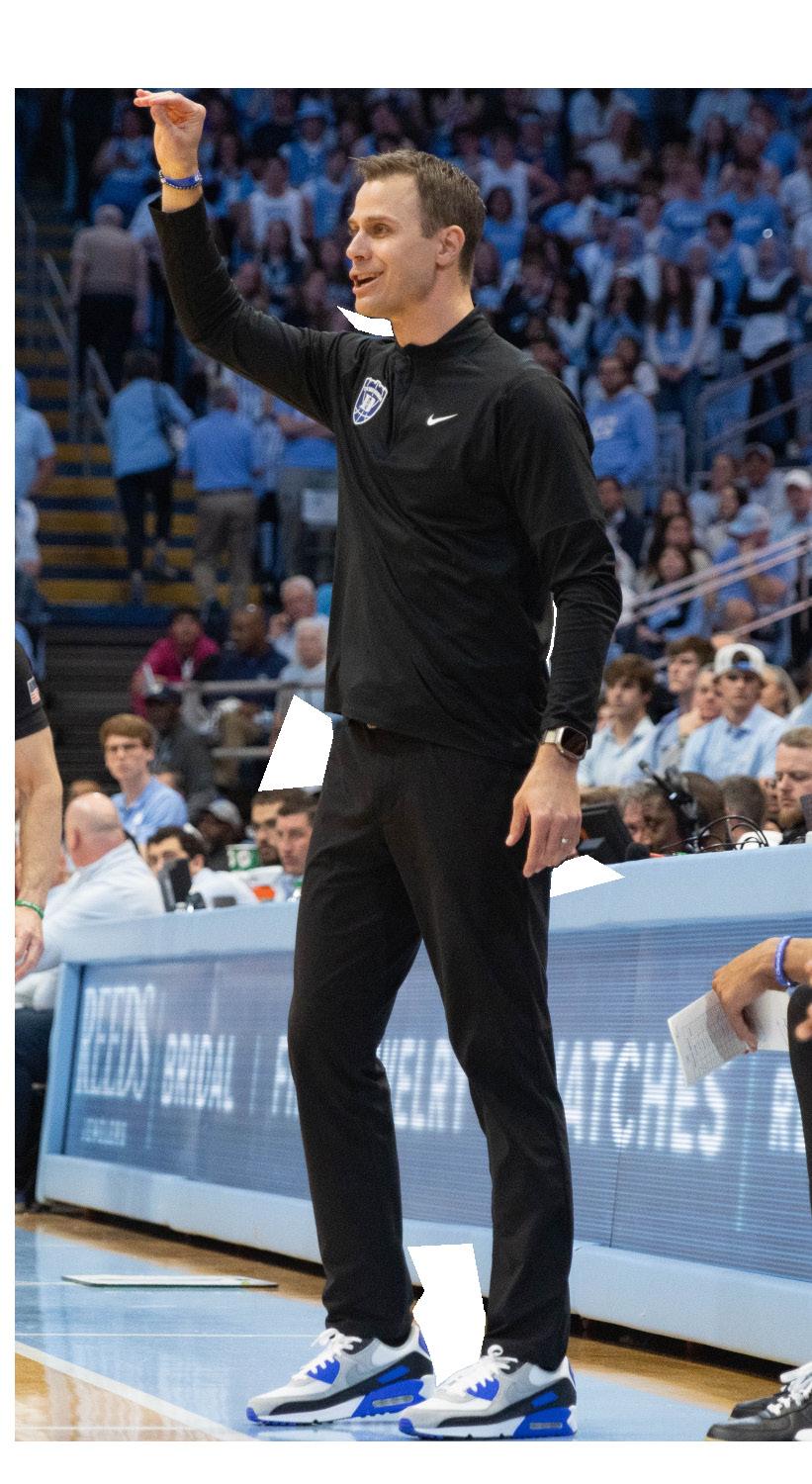

Flagg’s finest performance came Jan. 11 against Notre Dame, where he scored 42 points on just 14 field-goal attempts, setting the ACC single-game freshman record in the process. The freshman made a season-high four threes, which included three in the first seven minutes of the game. For head coach Jon Scheyer, the game was the actualization of Flagg’s outside shot.

“When you’re so talented and can create a shot almost any time, you’re not used to being mentally prepared to shoot,” Scheyer said after the game. “[Flagg’s] had to work through that some. It’s never been, ‘We need to make him a good shooter.’ He’s been a good shooter … to see it translate into a game like this is terrific.”

Even moments of adversity seem to be shortlived. Against Clemson Feb. 8, an ill Flagg had shot a poor 2-for-11 through 33 minutes, but with the contest slipping out of the Blue Devils’ reach, the freshman pulled them right back

in it. He scored 14 of Duke’s last 17 points, including three 3-pointers. If not for an ill-timed slip with 14 seconds to go, the Blue Devils may have emerged from Littlejohn Coliseum with a comeback victory.

“Cooper was just being Cooper there,” Scheyer said about Flagg’s scoring run. “He just has a special will.”

Flagg has been exceptional from the start of his college career on defense. His 49 steals lead the team and rank in the top 10 of the ACC. One of his best occurred in Duke’s Feb. 12 win against Cal, where he turned an errant pass from Joshua Ola-Joseph into a reverse slam. Flagg briefly checked his assigned player on defense before snapping his head back to intercept the pass, leading to a season highlight.

Another impressive highlight came late in the first half in Duke’s Feb. 17 victory over Virginia. Flagg, who had notched a nice rejection earlier in the game, recognized that teammate Kon Knueppel was lagging behind the Cavaliers’ Blake Buchanan. The freshman quickly adjusted, and with the rim in his face, altered Buchanan’s shot just enough to get the stop and log a block.

“Cooper does not care [about statistics],” Scheyer said following Duke’s Feb. 15 victory against Stanford. “He cares about winning.”

Flagg went down with an ankle sprain in Duke’s ACC Tournament quarterfinal against Georgia Tech. While the Blue Devils were still able to cut down the nets without him, their efficiency took a noticeable hit. From the beginning of the season to Duke’s regularseason finale against North Carolina, the Blue Devils were the second-most efficient team in college basketball, according to Bart Torvik. However, in three games where Flagg was mostly absent, Duke dropped to 13th.

For Flagg, the ACC Player and Rookie of the Year, dreams of securing Duke’s sixth national championship seem well within reach. If the Blue Devils get there, expect Flagg’s season-long improvement and resilience to be major reasons why.

Toby Fournier: Versatile scoring and short memory

As the 10th-ranked prospect on ESPN’s 2024 HoopGurlz recruiting rankings, Toby Fournier was expected to be an immediate impact player for the Blue Devils. While her famous dunking ability has yet to materialize in a game, her production has been outstanding, especially for a freshman.

“Toby plays the game at a really high level athletically,” head coach Kara Lawson said following Duke’s Feb. 6 win over Clemson. “She’s able to score, she’s able to rebound, she’s able to block shots.”

Fournier has done well in all three of those categories this season. The six-time ACC Rookie of the Week averages 13.4 points, 5.3 rebounds and 1.1 blocks per game while making 53% of her field-goal attempts. Her nine games with 20 or more points rank second all-time among Duke freshmen.

“Toby’s great … she’s a bucket,” junior guard Ashlon Jackson said following Duke’s Feb. 9 win over Miami. “Being able to lean on her and have her carry some of the load as a freshman is very impressive.”

Fournier has been particularly good about following her off-nights with strong performances. After scoring just two points

See FRESHMEN on Page 8

78 70

Cooper Flagg and Maliq Brown got hurt in the first half.

Kon Knueppel scored a career-high 28 points.

Knueppel, Khaman Maluach and Isaiah Evans combined for 56 of Duke’s 78 points.

74 71

The Blue Devils ended the first half on a 15-0 run.

Patrick Ngongba II netted 12 points, his first career double-digit scoring game.

After a North Carolina lane violation, Knueppel iced the game with two free throws.

73 62

Tyrese Proctor made a career-high six 3-pointers.

Only three Louisville players registered a field goal in the second half.

Duke trailed by five after 20 minutes, and is still undefeated when behind at halftime.

By Ranjan Jindal March 15, 2025 Sports Editor

CHARLOTTE — “Have a short memory.”

Duke guard Tyrese Proctor had a simple answer Thursday to the key to success in the ACC Tournament. After two of their worst 3-point shooting performances of the season and two monumental injuries, the Blue Devils followed the advice of their junior leader.

Duke defeated Louisville 73-62 in the ACC championship for its second league title in three years. The Blue Devils snapped the Cardinals’ 11-game win streak, and even without Cooper Flagg, Duke basketball will soon have a banner flying high. Duke’s backcourt trio — Proctor, Kon Knueppel and Sion James — led the way with 19, 18 and 15 points, respectively.

capped off by an emphatic Khaman Maluach rejection leading to the under-eight timeout.

“Edwards really had it going. So we we stayed with him a little bit more [on screens] when typically we like to get back, and Khaman does a great job protecting the rim,” Scheyer said. “They shoot so many threes, but we thought they were a paint team, so protecting the paint was a big key tonight.”

Edwards attempted to bring his team back, but the energy shift on both sides of the floor was too much for Kelsey’s squad to overcome. The Cardinals not named Edwards only had three field goals in the second half.

We didn’t need any Superman performances or anything like that. Everybody just stepped up and added to the team.

“Really proud of our team. To win this ACC championship, to win an outright regular season and to win in the tournament is special,” head coach Jon Scheyer said. “For us to be tested the last three games the way that we have, I think we’re going to learn a ton from it, and gives us extra motivation and lessons to move forward.”

Duke guard

Louisville graduate transfer Terrence Edwards Jr. opened the second half with an airball, and Proctor hit a three to immediately set the tone. Knueppel curled off a screen for his patented layup, and all of a sudden, the game was tied.

But Edwards was unfazed by the “airball” chants in the Spectrum Center and remained the best player on the floor with five quick points. He even hit a prayer over the outstretched arms of James as the shot clock expired above for 22 points on the evening. The 6-foot-6 former James Madison standout — averaging 16.2 points per game — was a thorn in the Blue Devils’ side all evening, exacerbating the effect of Flagg’s absence.

But Duke’s Group of 5 transfer had something to say. James scored 10 points in just four minutes, bookended by a pair of triples, the latter of which forced a Pat Kelsey timeout. Proctor hit a transition 3-pointer, and Duke led 57-47 with 11:08 left to play. The Blue Devils never looked back.

A defensive lapse from Louisville allowed Proctor to shoot a wide-open 3-point jumper from nearly the same spot as earlier, and Duke continued to extend its lead.

The Blue Devils ratcheted up their defensive pressure as well, blitzing screens and boxing out with more physicality, especially with the entrance of Patrick Ngongba II. The driving lanes that were once open immediately shut, and every Cardinal that touched the painted area was swarmed by a contingent of Duke blue. A block party ensued with five in the first 12 minutes of the second half,

“We just came out and played Duke defense. We went into the locker room at halftime, we regrouped together,” Maluach said. “We knew we had to get stops and rebounds, and that’s what we did.”

In the first half, Louisville grasped the momentum by tying the game at 25. Proctor hit a deep top-of-the-key 3-pointer off a Caleb Foster offensive rebound to wrestle the lead back, but once again, Edwards responded to tie it at 28 with 3:08 left in the half.

Duke went to zone after the break, attempting to trip up Louisville like it did with Georgia Tech Thursday night. However, the well-coached Cardinals were prepared.

The first play was a back screen on Maluach in the middle of the zone for a James Scott dunk, and Edwards hit his third 3-pointer of the contest on the subsequent possession to give Louisville the lead, which it kept to take a 38-33 halftime lead.

It felt as though Duke didn’t get a clean defensive rebound for the majority of the contest, but the second half was vastly different from the first.

Despite two of the best defenses in the league going at it, both sides showcased elite shotmaking ability to start. When possessions didn’t end in turnovers — as the inevitable ACC championship game butterflies found their way into the players — Duke and Louisville both connected on impressive shots.

Knueppel dove on the floor to tip it to Proctor. The ball found its way to Isaiah Evans, who hit a stepback three to give Duke a 14-12 lead with 13:12 remaining. Proctor continued the Blue Devil 3-point barrage with a left-wing splash. Not to be outdone, Edwards responded with a stepback to cut it back to two.

“I thought everybody contributed, and everybody pitched in, and we didn’t need any Superman performances or anything like that. Everybody just stepped up and added to the team,” Knueppel said.

Louisville point guard Chucky Hepburn hit two midrange fadeaway jumpers and a 3-pointer for his team’s first seven points of the evening. But he was held to just seven more the rest of the way, key to the Blue Devil win.

By Elle Chavis March 9, 2025 Associate Editor

GREENSBORO, N.C. — Queens of the ACC.

Almost exactly a year ago, the Blue Devils lost to the Wolfpack in the ACC championship. A month ago, they again lost to N.C. State behind 36 points from Aziaha James. This time though, not even James’ heroics could stop Duke from winning its first ACC championship under head coach Kara Lawson.

“We faced some of the best teams in the country three days in a row,” Lawson said. “We were able to put it all together in a weekend. And that’s what you want to be as a team in March that can put it all together.”

En route to claiming the ACC crown, the Blue Devils knocked off Notre Dame and Louisville, two teams they lost to in the regular season. But those regular-season losses clearly had no effect on Duke as it proved one thing is for certain: March is different.

Twenty-two points from both junior Ashlon Jackson and sophomore Oluchi Okananwa paved the way for the Blue Devils as they took down the top-seeded Wolfpack 76-62.

Even though Duke (26-7) was down in the first half, it was never out of the game. By the time the first half ended, the Blue Devils had cut the lead to 36-29, courtesy of a finalpossession 3-pointer from Jordan Wood.

“I was like, ‘Oh, this is my time,’” Wood said of her shot. “Coach Kara always says that being ready and staying ready is the key to the game.”

That shot seemingly gave the Blue Devils the momentum they needed to walk out of the locker room and into the second half with a new mindset. As it almost always does for Duke, that started on defense. An early steal on N.C. State’s first possession led to a layup from Delaney Thomas. Another rebound from Okananwa gave Jackson the chance for a fast-break jumper.

After Saniya Rivers gave the Wolfpack (26-6) their first points of the half with a clutch 3-pointer, Okananwa responded on the other end with one of her own. After a defensive rebound from Toby Fournier, Reigan Richardson sailed down the court and made the pullup jumper, and suddenly, the game was tied at 42. Another rebound by Fournier gave Taina Mair the ball for the perfectly placed layup as the Blue Devils captured their first lead of the game.

The Wolfpack made it clear though that if the Blue Devils wanted to take them down, they would have to fight with everything they had.

And fight they did.

Having finally lit its spark, Duke refused to let N.C. State extinguish it. The Blue Devils’ defensive pressure enforced a three-minute scoring drought on their opponent to end the third quarter.

“We just kept gaining momentum and making plays on offense, making plays on defense,” Lawson said. “[That was]

something we emphasized with the group. We needed to come out and play our brand of basketball.”

That energy continued into the fourth quarter as the Blue Devils looked to close out the game. The assembled fans at First Horizon Coliseum — mostly repping Wolfpack red — brought on the energy as the closing minutes of the game ticked down. But not even the deafening cheers of the N.C. State faithful could stop the Blue Devils, who hit the motor with no plans of running back.

N.C. State did everything it could to recapture the lead, but Duke had learned its lesson from the last time these two teams met up and never let up on the defensive end. Winning the rebounding battle also aided the Blue Devils in taming their opponent as they handily outrebounded the Wolfpack 44-28.

“Rebounds win games,” Jackson said. “In order for our team to have a chance, we had to continue to buckle down [and] try to get second chances.”

Those rebounds — along with Jackson and Okananwa’s heroics — allowed the Blue Devils to control the pace of the game and fend off the Wolfpack for good.

However, the squad from Raleigh got off to a fiery start to the championship game. Missed looks kept Duke scoreless for the opening minutes of the game. Meanwhile, N.C. State seemed unable to miss. A steal from Rivers led to a 3-pointer from James and before the Blue Devils knew it, they were down 7-0.

Lawson immediately called a timeout to refocus her team from the rocky start. Right out of the timeout, Mair drained a jumper to put Duke on the scoreboard and inject some life into her team.

Shortly after, Okananwa did what she does best: come off the bench with a burst of energy. The Boston native used her unwavering hustle to crash the boards and secure a rebound before charging down the other side of the court and drawing a foul. After missing the second shot from the charity stripe, Okananwa made yet another rebound and scored a layup.

“Oluchi just impacted the game at a really high level on both ends for us in the first half,” Lawson said.

Every time Duke attempted to bring itself back into the game in the first half, the likes of Rivers or Zoe Brooks, who shot an impressive 5-for-6 from the field in the first half, stormed past its usually stalwart defense. Additionally, turnovers gave the Wolfpack even more opportunities to score and build a 19-10 lead going into the second quarter.

It was halfway through the second quarter when the Blue Devils began to right the ship. As veteran leaders are expected to do, Jackson came through with the offensive fire for Duke. Back-to-back jumpers from the junior guard helped keep Duke within reach of N.C. State, and Jackson and Okananwa provided much of the offensive fire for the Blue Devils, continuing to make key shots and rebounds that prevented the Wolfpack from running away with the game.

61 48

The Blue Devils finished with four players in double figures.

In the third quarter, the Cardinals went 5:51 without a field goal.

Duke held Louisville 25 points below its season average.

61 56

Oluchi Okananwa was a perfect 3-for-3 from the field and 6-for-6 from the line.

Duke took the lead after outscoring Notre Dame 1811 in the third quarter.

The Blue Devils won the rebound battle 38-26.

After losing the first quarter 19-10, Duke outscored N.C. State 66-43.

Okananwa and Ashlon Jackson each scored 22 to lead the way.

The Blue Devils held the Wolfpack to just 32% shooting in the second half.

FROM PAGE 3

But there is little that anyone can think of to accuse Feinstein other than a harsh temper and a blatant disrespect for authority.

He “outworked everyone,” as Remnick put it, frequently writing and publishing books in the span of a year without halting his other commitments. He was fearless in his reporting, brave enough to spend the better part of a year with longtime Indiana basketball coach Bob Knight, one of the rare people in the world who might have outstripped Feinstein in attitude and ferocity.

Readers relied on Feinstein to find answers to questions most reporters never asked. He hated flying, so he drove to ask them.

Feinstein was generous in more than one way. He once sent opera tickets to Honigberg and his girlfriend, and he taught reporting to college students. He gave most of the hours of his life to other people, listening to and recording their stories, showing up with his stubborn curiosity and wide-open ears.

“He had a certain mensch-y quality about him,” Remnick said.

In the early 1990s, Feinstein came back to Duke. He formalized his role as teacher and became a visiting professor of journalism.

Feinstein was already a giant in the field; he certainly did not teach for money.

Svrluga took a class with Feinstein his senior year. Ever opinionated, Feinstein told his students how to report, and provided plenty of feedback on their work. The class was a small seminar and Feinstein, for all of his volatility, made that space “a warm environment” for Svrluga. When Svrluga wrote a men’s basketball game preview that The Chronicle published, Feinstein walked into class the next day full of praise.

Most of Feinstein’s columns in The Chronicle — like most of his work — were unapologetic. His final was not. In his farewell column, he wrote with an unusually humble pen.

“As sports editor of this newspaper I have received a remarkable amount of help from the people around me … My only hope is that in the future I will have a chance to contribute to the lives of others as these people have contributed to my life. And I hope that those who follow me here, as writers, as students and as people will receive and return the same kind of help I have received. Maybe it’s corny. But that’s what I think life is all about.”

Feinstein was a grouch and a curmudgeon. A justified, but annoying, know-it-all. An oddball and sometimes a laugh. Certainly a great journalist.

Certainly someone who cared.

The Chronicle is accepting remembrances for Feinstein. To submit yours, email opinion@ dukechronicle.com.

FROM PAGE 4

against South Carolina Dec. 5, she dropped 27 points three days later against Virginia Tech. And following a two-game losing streak to Notre Dame and Louisville, she responded with a dynamic trio of games against Syracuse, North Carolina and Florida State. Fournier averaged 23 points and 7.3 rebounds per game during that span, which included a season-high 28 against the Seminoles. Her game against Florida State was all the more impressive considering she was matched up against Makayla Timpson, one of the best defenders in the ACC.

“It’s definitely the finest performance by a freshman in a league game this season.” Lawson said of Fournier’s outing against Florida State. “And it goes without saying, this is the freshman of the year in the [ACC]. If you can’t see that, you gotta go to the eye doctor.”

Fournier credits the mindset of invulnerability to losses to Lawson, who echoed her words after the game.

“There’s nothing to be embarrassed about losing a game,” Lawson said. “What’s embarrassing is if you lose it and you don’t fix the problem … you’re quitting or you’re choosing to turn a blind eye to what your downfall is.”

While the vast majority of Fournier’s scoring has come under the rim or at the free-throw line, she has shown flashes from longer distances. The freshman has scored five 3-pointers this season, and even nailed a midrange jumper against Syracuse.

“The midrange is definitely part of my development,” Fournier said after the Syracuse game. “When you get that midrange, you’re able to open up a lot of different things … you

can use the shot-fakes to get to the rim, which is one of my strengths.”

A special part of Fournier’s game is her elite back-to-the-basket post-up ability, becoming more uncommon in college basketball. Her 6-foot-2 stature and athleticism allow her to bully defenders to the basket, and her long wingspan grants her the ability to hit shots off the glass from a variety of angles.

Like Flagg, Fournier has always been a capable defender. Her 35 total blocks rank in 10th in the ACC and second among freshmen. Fournier’s career high came against Belmont Nov. 21, where she snagged three blocks to go along with 25 points.

“She’s really versatile defensively,” Lawson said of Fournier at a Mar. 5 media availability. “She can switch onto guards and guard them. She can hold her own against some of the top post players in the league.”

In a chaotic pair of possessions against Miami Feb. 9, Fournier put up a tough shot, which was corralled by the Hurricanes’ Natalija Marshall for the rebound. Fournier’s eyes never wavered from Marshall, which allowed the Toronto native to corral her third steal of the afternoon when Marshall mishandled the ball. Fournier snagged the loose ball and converted a difficult layupand-one.

With the ACC Tournament wrapped up, the spotlights for the NCAA Tournament will be set heavily on two Duke freshmen separated by Ontario Highway 401. Regardless of the season’s ultimate result, Flagg and Fournier have proven that a youth movement for Durham’s finest is in full swing.

Don’t miss anything this March — sign up for Sportswrap, The Chronicle’s weekly email covering Duke sports!

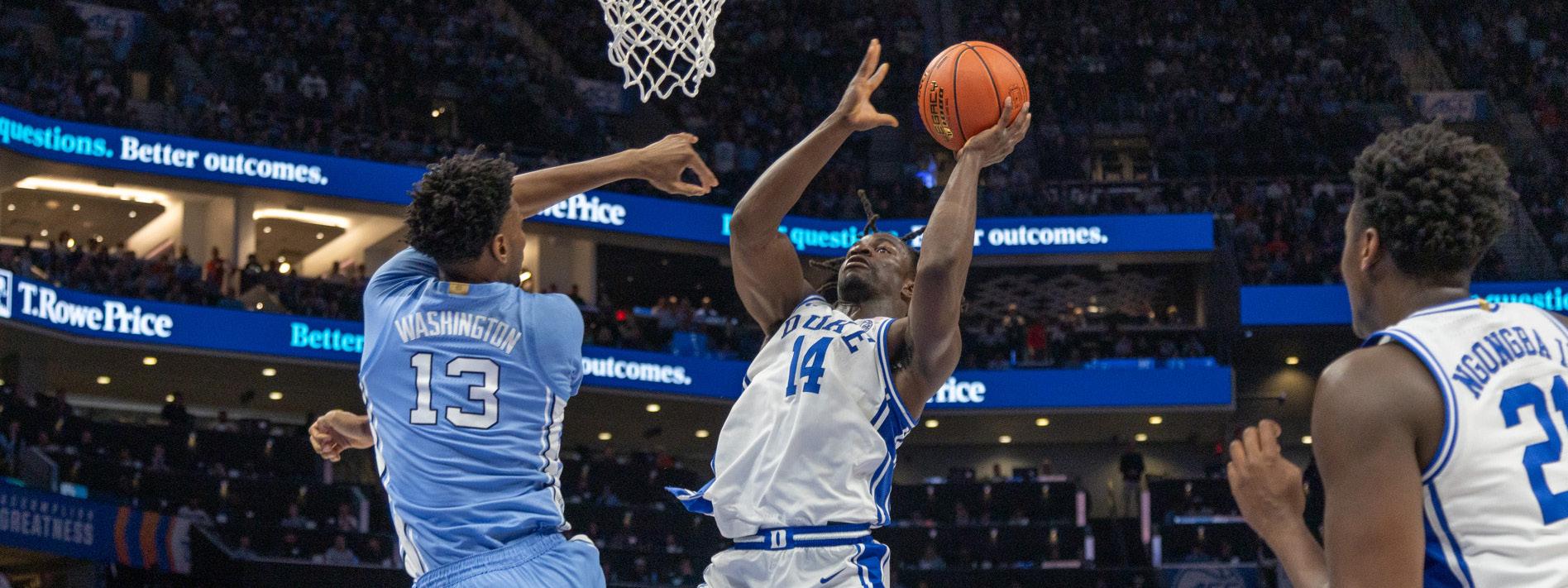

Anabel Howery | Sports Photography Editor Sion James goes for a layup in the ACC semifinals against North Carolina.

Karen Xu | Photography Editor

Tyrese Proctor takes a contested three in Duke’s eventual loss at Clemson.

By Dom Fenoglio Sports Managing Editor

How many games are played in March Madness?

No need to picture a bracket or do any manual counting, there’s an easy trick. Of the 68 teams who make the tournament, 67 have to lose. Sixty-seven games means 67 losers and one national championship.

After winning the ACC regular-season and tournament titles, Duke is gunning to be the last one standing, while the rest of the field is head-hunting the top seed. Only three teams have beaten the Blue Devils all season, and two of those losses came before the new year. While both Kentucky and Kansas outplayed Duke, it is not helpful to analyze those games with months of added context. Since then, Clemson has been the sole blemish, and the Blue Devils even won a pair of high-leverage games without superstar Cooper Flagg.

However, the ACC Tournament also showed that the Blue Devils are not invincible. In the first half against Louisville and the second against North Carolina, Duke’s opponents were the aggressors. As with any win against an elite team, that is the first prerequisite; head coach Jon Scheyer’s team has shown the lion-like instinct to pounce on prey that cannot match its intensity.

The other reasons various teams have found themselves on runs against the Blue Devils are more subtle. More than making a highpercentage of shots, winning the rebounding battle and avoiding turnovers, how can another team beat Duke? Maybe more important, what pieces do teams need?

Find the right matchups

A great example of success against the Blue Devils comes from an unlikely source: the 12-19 Boston College Eagles. In a trip to Chestnut Hill, Mass., Duke eventually coasted to a 25-point win, but Chad Venning stole the show early on. The 6-foot-9, 270-pound center scored nine points in the first half, crashed the offensive glass hard and thoroughly outplayed freshman Khaman Maluach. Scheyer had no answer to Venning until the second half, when the big man was worn down and his team eventually gave way.

Venning exemplifies a type of player the Blue Devils have struggled to defend: a surefooted, physically imposing big man whose main task is to find the basket on offense. Duke is at its best on defense when its constant switching prevents guards from driving past the free-throw line. A frontcourt player with the ability to both pass and score out of the post takes that advantage away.

However, a one-man matchup problem is a necessary, but not sufficient component in beating the Blue Devils. What happened to Venning also happened to Louisville’s Terrence

Edwards Jr. in the ACC championship and countless other players over the course of the season. Scheyer’s defensive unit is too good to get punked by one player. Be it a halftime adjustment, a change in guarding responsibilities or mixing up ball-screen coverages, Duke will get the ball out of the No. 1 option’s hands.

In fact, a team that beats the Blue Devils should have more than two matchup advantages.

Take the ACC Tournament semifinal, where the Tar Heels’ Elliot Cadeau, Ven-Allen Lubin and Seth Trimble all became problems for Duke on the defensive end in the second half. Despite losing a few inches to the Blue Devils’ entire backcourt, Trimble and Cadeau consistently won in transition and got to the basket to score, get fouled or distribute. Duke’s original solution was to pressure Cadeau hard enough to force it out of his hands, while also emphasizing denying Lubin in the post. But Trimble’s own fast-break drives forced the Blue Devils out onto their toes, like trying to catch three balls with two arms. The fact that RJ Davis — North Carolina’s leading scorer — was also a threat further exacerbated Duke’s lapses.

The Tar Heels fielded the second kind of player Scheyer’s team has had a tough time with: smaller, quicker guards with a knack for creating space. For another example, 5-foot-11 Notre Dame guard Markus Burton laid 23 on the Blue Devils, though he was overshadowed by a 42-point outing from Cooper Flagg. Length on the perimeter is certainly a strength for the Blue Devils, but it can be harder for a taller guard like Sion James or Kon Knueppel to follow the feet of a player like Cadeau, Davis or Burton.

Duke won by the skin of its teeth, but by the end of the game it was North Carolina in the driver’s seat. After identifying where they could gain an edge, the Tar Heels leaned hard into those matchups. More than that, though, they did it their way.

Play your game, not Duke’s

It is no secret that North Carolina likes to play fast — ranking 34th in adjusted tempo, according to KenPom. Getting out in transition was the biggest key in the Tar Heels near comeback, but it is not the only way to get past Duke.

Wake Forest, another in-state rival, gave the Blue Devils a major scare in Winston-Salem, N.C., Jan. 25. The Demon Deacons play a starkly different game, looking to slow a track meet into a slug fest. With center Efton Reid III and leading scorer Hunter Sallis, Wake Forest had a few places where it could look to exploit Duke, but the reason it led with 5:44 remaining was due to its suffocating defense.

Because of their syrupy pace, the Demon Deacons make every miss feel like three, often creating a psychological pressure that affects

shooters. Sure enough, the Blue Devils shot just 9-for-32 from 3-point range, well below their season average.

The point here is this: Duke will not lose if it is calling the shots. An aspiring giant slayer must dictate the flow of the game, and create situations instead of reacting to them.

If not for the late-game heroics of Purdue transfer Mason Gillis, Wake Forest could very well have stormed the court for the second time in two years against Duke.

The only team that did get such an experience were the Clemson Tigers. Viktor Lahkin, Ian Schefflein and Chase Hunter got looks they wanted to. Flagg was forced to play constant interior defense and could not find a rhythm on offense for most of the game. The Tigers were physical and confident, and their game plan was simple: make tough shots. Clemson shot 58.8% from the field, becoming the first team all season to shoot above 50% against Duke.

As the first 10 minutes of the game stretched into 20, then 30, the Blue Devils kept waiting for the home team to get cold and go on one of those classic Duke runs. But the Tigers never did.

The key to the Blue Devils’ stifling defense has not been a massive turnover margin or press system, it’s been simplicity. Duke’s opponents average 19.1 seconds per possession, the longest in the nation. Scheyer’s system, and his players’ elite athleticism, forces offenses into running near-perfect sets only to get contested looks.

Still, Clemson looked completely comfortable in its offense. Nor were the Tigers dissuaded by the Blue Devils’ own attack led by Tyrese Proctor. It was clear that Clemson thought it could make more buckets than Duke, and it was right. Flagg finally caught flame in the game’s final minutes, but a slip on the baseline sealed the Tigers as the only ACC team all season to win against the Blue Devils.

Perhaps more than their shot making, the Tigers’ biggest advantage was their aggression. They established a level of physicality from the tip that allowed them to constantly pressure the Blue Devils without fouling. No movement was comfortable, no catch clean. Clemson also outrebounded Duke by 13, including 11 offensive boards. Usually, when watching the Blue Devils it is clear that the other team is trying to keep up. In this game, the Tigers were the ones doing the hunting.

Duke’s offense is simply too good to allow it to run without intervention. The list of shot makers on the roster stretches a mile, and once a player like Isaiah Evans sees one go down, the rim gets about 10 inches wider. So, a team looking to beat the Blue Devils needs to disrupt.

One of the best individual defensive efforts on Flagg came from N.C. State’s Dontrez Styles. The 6-foot-6 forward lived on the

freshman superstar’s hip, and probably would have trailed Flagg back into the locker room if allowed. Flagg, a player known for the ease with which he plays, could not have looked more uncomfortable, and the Wolfpack even built a 13-point lead.

But the problem with such coverage is that it often leads to foul trouble. Styles picked up his third personal foul with 17:44 remaining in the second half, and the Blue Devils’ wore down N.C. State until the Wolfpack’s physicality subsided.

The biggest key to an aggressive defense is depth. It is unreasonable to expect one player, like Styles, to guard a talent like Flagg for a whole game. A team that beats Duke by outmuscling it should have at least nine, probably 10, players capable of playing key minutes.

Clemson sent out 10 players in its win. Back in November, Kentucky’s experience allowed it to play 10 as well, rotating defensive assignments on Flagg to tire him out. Louisville only fielded seven, and was running on empty by the end of the game.

Most of the examples of beating Duke come from teams that, well, did not beat Duke. The Blue Devils have lost one game in 2025 and appear to somehow still have their best basketball ahead of them.

When Duke lost to the Jayhawks and the Wildcats, players like Isaiah Evans and Patrick Ngongba II Scheyer has confident playing for significant minutes.

The top of the Blue Devils’ lineup is strong, but their own depth is what makes them one of, if not the best team in the country.

Plenty of teams have been capable of beating Duke for 20 minutes. Less have lasted longer than 30. Sixty-seven other teams have a shot, but it remains to be seen if another opponent can stay in the ring for the full 40.