7 minute read

The bird behind the legend

The bird behind the legend

SCIENTIFIC NAME

Advertisement

WEIGHT 2.3–4.5 kg

TOP SPEED 110 km/h

WINGSPAN Approx. 165cm

ALTITUDE Can reach a height of 4,800 metres during migration, making it one of the highestflying birds in the world.

DIET They are omnivores with a varied and opportunistic diet. They seek out small mammals, earthworms, snails, crickets, and other large insects in water-meadows, grasslands, and arable fields.

Mention the word “stork” to anyone in Britain and the image that jumps to mind will likely be of a large, majestic white bird carrying in its beak a baby wrapped in a cloth bundle. This image plucked straight from the pages of mythology could well be the only one many people have of this once abundant bird, which is now a rare sight in the UK.

In 1416, the last known breeding pair of white storks in Britain were recorded nesting on St Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh. Since then, there have been no confirmed records of a pair breeding in the wild. Evidence suggests that these spectacular birds were once widespread across the British Isles. Why they failed to survive is unclear, but it was most likely a combination of habitat loss, over-hunting and targeted persecution. Now, more than 600 years later, we are working alongside private landowners and conservation organisations to return storks as a breeding bird in Britain.

LIFE IN THE PENTHOUSE

Outside of the UK, white storks are a familiar sight throughout central and southern Europe and are often found living close to people. Nesting storks are hard to miss as their large, bulky nests stand up to 30m above the ground. They nest either solitarily or in loose colonies of up to 30 pairs, with individuals often returning to the same nest sites each year.

In some regions, such as Cheshinovo-Obleshevo in North Macedonia, silhouettes of the birds standing tall on nests built on telegraph poles, pylons, trees, and rooftops dominate the skyline. In many of these “stork villages”, people have a close connection with the birds, and many consider them to be a sign of good luck. Some people even go as far as to erect cartwheels and platforms onto their roofs to actively encourage them to nest.

A GREAT MIGRATION

In 1822, near the German village of Klütz, an astonishing discovery was made – a stork was found with an arrow embedded in its neck. The fact that it had somehow managed to survive the attack was only part of the mystery surrounding the bird. The weapon was identified as being a kind found only in central Africa. Up until that point, very little was known about bird migration, this discovery was one of several which provided early evidence that birds could migrate over large distances.

Each year, as winter begins to descend over Europe, white storks fly south in spectacular flocks, which can number into the thousands. They take to the skies by day and come down to roost in trees and open country by night. Most individuals migrating from Europe and North Africa will eventually end up in sub-Saharan Africa. Using their large wings, they soar on rising warm air currents reaching altitudes exceeding 1,500 metres and glide over vast distances. As these warm currents only form over land, they cannot migrate across large bodies of water, such as the Mediterranean Sea. Individuals travelling from Europe diverge through the Bosporus in the east or the Strait of Gibraltar in the west.

Sadly, their journey is not without its dangers. Exhausted birds often collide with overhead powerlines and shooting along their migration route still poses a threat to the species.

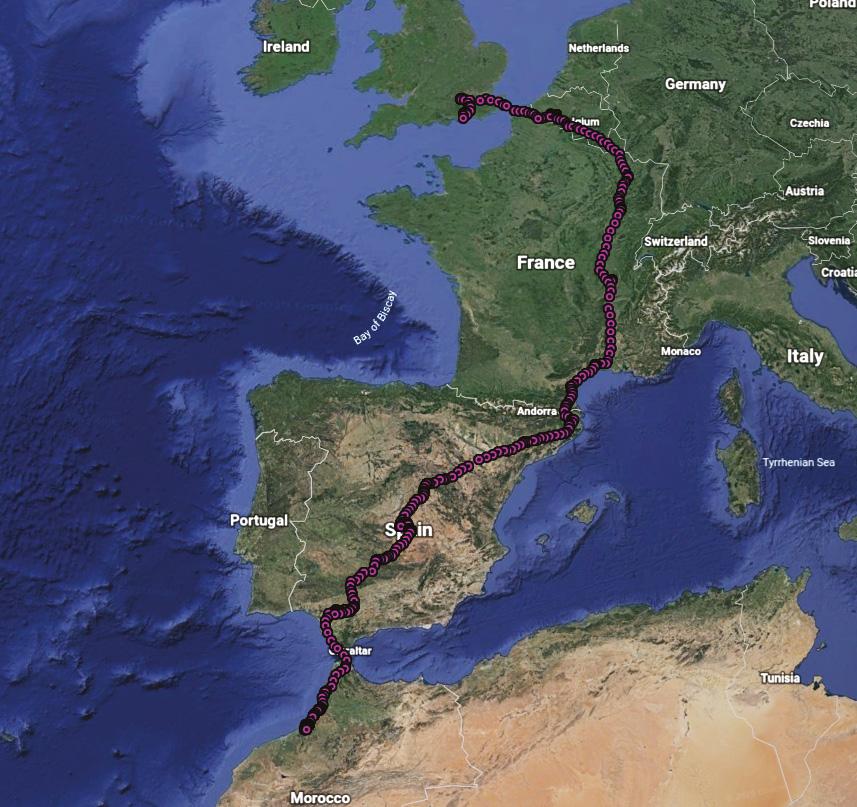

Marge’s migration route

Returning an icon

The White Stork Project aims to restore at least 50 breeding pairs in Southern England by 2030. The project, of which Durrell is a key partner, will focus on releasing at least 250 storks at several sites around Sussex to establish local breeding colonies.

“Across Europe, white storks have lived alongside people for generations and have become a part of the culture and heritage of those countries,” says Durrell’s White Stork Project Officer Lucy Groves. “They have been used in other reintroductions across Europe as a flagship species for wetland creation and restoration. We chose Sussex as an ideal place to release storks as it has vast areas of floodplains and wet grasslands. The hope for them in the UK is to engage and inspire people and drive proconservation behaviour.”

ATTEMPTED NESTING

Earlier this year, a pair of young storks began nesting at the Knepp Estate in West Sussex, which gained a lot of media attention including a feature on BBC Springwatch. “We were thrilled when a couple of our storks built a nest in an oak tree at Knepp this year,” says Lucy. “We watched excitedly as they displayed to each other and began building the nest. The female laid three eggs, and we waited expectantly throughout May, but unfortunately, they did not hatch. The female is still young, having just reached breeding age, and we think that the eggs were infertile. Despite the disappointing news, we are hopeful that they will return next year and attempt to nest again. Storks are faithful to the nests they create and return each year. We will certainly be keeping a close eye on the oak tree in 2020!”

TAKING FLIGHT

White stork takes flight

This summer, 24 juvenile white storks were released at the Knepp rewilding project after being hatched and raised at Cotswold Wildlife Park. “Despite the regular occurrence of vagrants from Europe, natural re-colonisation is unlikely,” says Lucy. “Therefore, the reintroduction of white storks will be carried out in three phases. The first is to create a static population using rescued birds from Warsaw Zoo, these act as a magnet for any storks flying over. The second phase is to create a free-flying population using birds from Poland that are kept at the site for two years in a large aviary before being released. The third phase is to create a migratory population, this is why we are releasing juveniles each year. These young storks have the instinct to fly south in their first autumn, heading towards their overwintering grounds in Africa, and then subsequently returning the following spring.”

The storks have unique coloured rings on their legs so they can be individually identified. Eight members of the group were also fitted with GPS tags so their flight paths can be tracked as they travel south for the winter. “It has been a joy to see the juvenile storks leaving the release pen and taking to the skies with our free-flying adults,” says Lucy. “I have been blown away by the enthusiastic response, not only from our local community but also from birders and members of the public. Many people have provided us with detailed sightings, which are crucial for helping us to understand the behaviour of these young storks. We have had reports stretching from East Sussex to Penzance in Cornwall, where the birds spent some time wowing holidaymakers. We are happy that some of the birds have made their way back to Knepp, while excitingly, others have decided to travel south.

One individual, named Marge, crossed the English Channel in August and headed south through France and Spain. After a week or two spent feeding up on a rubbish tip south of Madrid, she continued south. She eventually crossed the Strait of Gibraltar on 23rd September becoming our first British bred white stork to successfully migrate! She is currently in Morocco in an area which is used by overwintering storks from across Europe.”

ENGAGING A COMMUNITY

The White Stork Project is one of many conservation initiatives outlined in Durrell’s Rewild Our World strategy, but this is about more than just returning lost species. “There is a growing realisation that a positive, connected relationship with nature increases pro-environmental behaviours and is an essential part of wellbeing,” says Lucy. “This nature connectedness holds benefits for individuals, just as it does for the natural world as a whole.

This project will use storks to engage communities to connect with their local wildlife and to strengthen emotional connection towards nature. White storks are charismatic birds. Their large size, colourful plumage, colonial nesting behaviours and well-established folklore already ensures their popularity throughout their European range.

In a time of increasing disengagement with nature in the UK, bringing back the white stork could be a means by which to reignite our affection for the natural world, and drive pro-conservation behaviour change and environmental restoration.”

Young storks raised at Cotswold Wildlife Park

Aerial view of the nest at Knepp

This project is being carried out in partnership with Knepp, Wadhurst and Wintershall, as well as the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, Cotswold Wildlife Park, and Warsaw Zoo. To find out more about the project or report sightings, visit www.whitestorkproject.org.