BANGON

Lessons from the Filipino Vernacular in Post-Disaster Architecture

Lessons from the Filipino Vernacular in Post-Disaster Architecture

POLITECNICO DI MILANO

SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

URBAN PLANNING CONSTRUCTION

ENGINEERING

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN STUDIES

MASTER DEGREE IN ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN DESIGN

A.Y. 2023/2024 DECEMBER 2024

cover image: Drawing by author

Lessons from the Filipino Vernacular in Post-Disaster Architecture

STUDENT

Earl Dan Dela Cruz Baua ID 220781

ADVISOR

Pierre-Alain Croset

CO-ADVISOR

Paolo Scrivano

“Who will be so rash as to say that we have no need of a Filipino “style” in architecture or that that need has already been filled?

Who will be so imprudent as to protest that the architect has no responsibilities to the larger community in which he works?

The buildings of the Philippines must reflect the Filipino ambience. Which more than Filipino topography and climate means the Filipino people?”

Leandro Locsin

Need for a Filipino Style in architecture, 1966

I would like to express my gratitude to my family. Even from afar, their continuous support was invaluable and made it possible for me to pursue my studies.

I thank Professor Pierre-Alain Croset and Professor Paolo Scrivano for the engaging conversations and guidance in the past year.

Finally, thank you to all of the friends and classmates from the Politecnico di Milano for an incredible two years.

Con l’aumento della frequenza degli eventi meteorologici estremi dovuti ai cambiamenti climatici, milioni di persone sono costrette ad abbandonare le proprie abitazioni a causa dei disastri naturali. Molte di queste colpiscono in modo sproporzionato le comunità nei paesi del Sud Globale, che spesso fanno affidamento su aiuti umanitari esterni per il processo di recupero. Questi aiuti comprendono la progettazione e la costruzione di strutture post-disastro.

La ricerca supporta la ricostruzione di abitazioni come un processo continuo, invece di considerarlo un prodotto finale, dimostrando inoltre che un recupero post-disastro di successo si basa sulla sostenibilità a lungo termine. Ai fini di promuoverla, gli architetti che operano in queste situazioni devono assicurarsi che i progetti siano sensibili al contesto culturale e climatico. Come possono quindi gli architetti meglio comprendere l’ambiente in cui stanno progettando? L’architettura vernacolare potrebbe offrire alcune risposte.

Le tecniche e i metodi costruttivi dell’architettura vernacolare si basano su conoscenze sviluppate nel corso dei secoli e rappresentano una risposta diretta al clima e alle abitudini della popolazione locale. L’attenzione a questi fattori potrebbe portare a strutture meglio progettate e, di conseguenza, a un recupero post-disastro più efficace.

Per illustrare i legami tra l’architettura post-disastro e l’architettura vernacolare, la tesi si concentra sulle Filippine, un paese soggetto a disastri naturali e ricco di tradizioni architettoniche. Attraverso ricerche, disegni e progetti architettonici i caratteri vernacolari dell’architettura filippina vengono applicati ai fini di rendere più efficiente il recupero post-disastro, all’interno della nazione.

As the frequency of extreme weather events rise due to climate change, millions of people are being displaced from their homes due to disaster. Many of these disasters disproportionately affect communities in countries of the Global South, which often rely on external humanitarian aid in their recovery efforts. This aid includes the design and construction of postdisaster structures.

The research will show that successful post-disaster recovery is about long-term sustainability and that the sheltering process should be viewed as an ongoing process rather than a final product. To promote sustainability, architects working in postdisaster operations must ensure that their designs are climateresponsive and culturally sensitive in order to be functional and well received by the local people. How then, can architects better understand the local contexts in which they are designing in? Vernacular architecture could provide some answers.

The techniques and construction methods of vernacular architecture are based on knowledge developed over centuries and is a direct response to the climate and ways of life of the local people. Attention to these factors could lead to better designed structures and consequently, more successful postdisaster recovery.

To illustrate the links between post-disaster architecture and vernacular architecture the thesis focuses on the Philippines, a country prone to disaster and that has rich architectural traditions. Through research, drawings and architectural design, this thesis shows how the qualities of Filipino vernacular architecture could be applied to make post-disaster recovery efforts more successful within the nation.

post-disaster; vernacular; filipino; shelter; transitional KEYWORDS

Chapter One: Introduction

Chapter Two: Post-disaster Architecture

Not really natural disasters: A call to action Thesis Methodology

Defining Humanitarian Architecture

What makes postdisaster recovery successful?

The role of architecture Prefabrication and Community Participation Focusing on Transitional Shelters

Transitional Shelters: Case Studies

Chapter Three: The Filipino Vernacular

Defining Vernacular Architecture

Research focus area: The Philippines

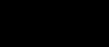

A Short History of the Filipino Vernacular DRAWINGS: Filipino Vernacular Elements

Chapter Four: Research through Design

Chapter Five: Three Transitional Structures

Chapter Six: Conclusions

MINDMAP: Links between post-disaster and the Filipino Vernacular

KUBO: Transitional Shelter Conclusions and Reflections

BATALÁN: WASH Facility

TAGPUAN: Community Pavilion Forming a Design Brief Material Choices and Construction Details

Bibliography

List of figures

Not really natural disasters: A call to action

Thesis Methodology

Quote by Shigeru Ban in the book

Humanitarian Architecture (Ban, 2014)

People are not killed by earthquakes, they’re killed by collapsing buildings… That’s the responsibility of architects, but the architects are not there when people need some temporary structure because we’re too busy working for (the) privileged.

Even a temporary structure can become a home.

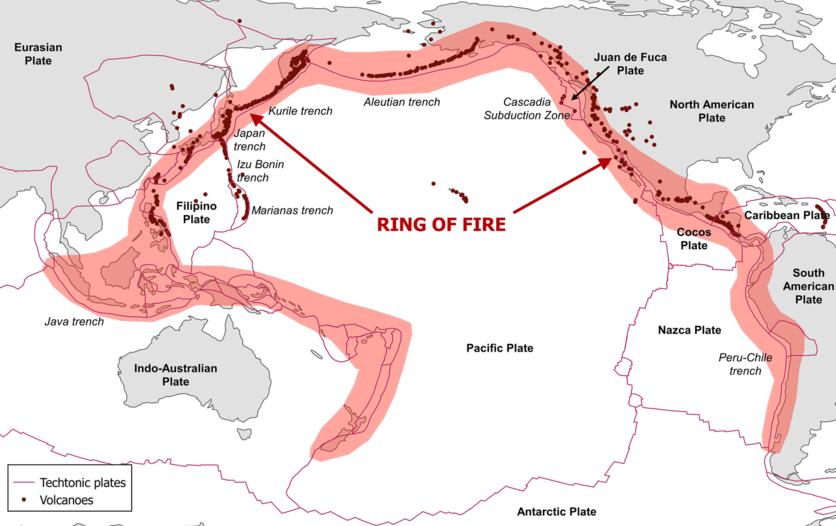

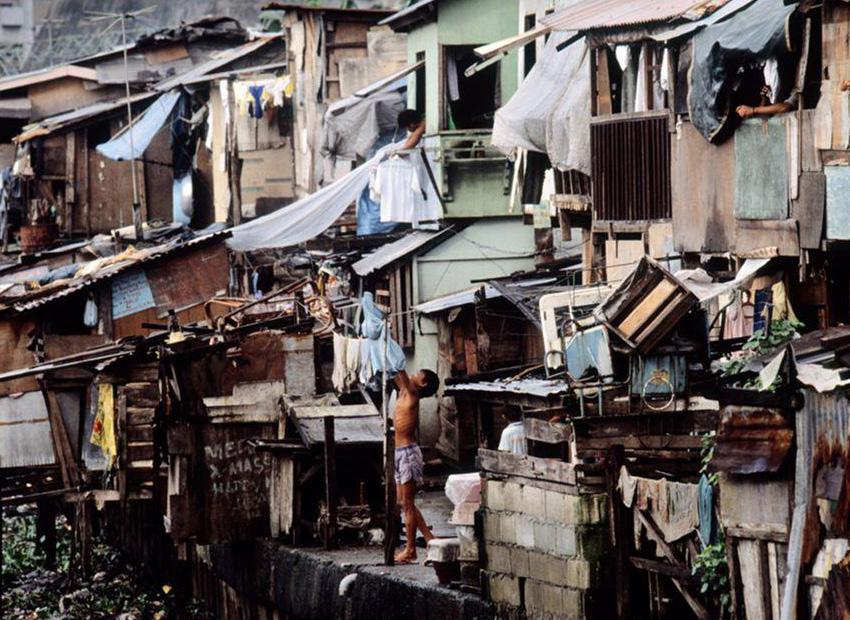

According to UNHCR data, by the end of 2022, approximately 60 million people were displaced from their homes due to conflict and natural disasters (UNHCR, 2023). Typhoon Yolanda, for example, hit the Philippines in 2013. Being one of the most powerful cyclones ever recorded, it affected 11 million people, of which 4 million were displaced. It caused extensive damage to infrastructure and housing throughout the country. Due to the effects of climate change, extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, and as the seas get warmer, scientists predict this could lead to even stronger typhoons in the future.

Such disasters are particularly harsh on countries in the Global South. As the thesis will discuss in the following chapters, a disaster occurs when a natural hazard meets a vulnerable community. Countries such as the Philippines, where poverty is widespread, are particularly susceptible and may not have the resources to recover after a disaster. This is why these countries depend on external aid for assistance; this can include the supply of temporary shelters. Due to a lack of resources, the process of reconstruction and acquiring permanent housing can be slow, and it often happens that afflicted communities are required to stay in temporary shelters for longer periods than anticipated.

The role of an architect is seldom considered essential in post-disaster relief operations. Although architecture is not a primary need such as immediate food, water, and medical aid, an architect’s skills and creative problem-solving are valuable in relief operations from the beginning. David Sanderson,

Director of the Centre for Development and Emergency Practice in the Department of Architecture at Oxford Brookes University, says that the role of architects is minimal in postdisaster operations, and this could be attributed to “the common concept that what they (architects) do is mainly for aesthetic purposes” (Sanderson et al., 2014).

While it is true that many of the issues in humanitarian response are related to political factors and funding, there is certainly a place for architects to contribute in this field. Nonprofit organisations such as TAO-Pilipinas and LokalLab in the Philippines are just two examples that demonstrate the impact architecture can have in revitalising communities.

The motive behind writing this thesis was to shed light on the ways architects can contribute to the success of postdisaster operations. A considerable amount of the academic architectural discourse surrounding post-disaster structures looks at high-tech solutions. In contrast, this thesis approaches the topic from another angle. Looking to traditional knowledge, the thesis aims to highlight the benefits of studying vernacular architecture in order to better support communities in recovering after a disaster.

The intention of the thesis is not to say that vernacular architecture is the only answer to all issues of post-disaster. The complexity and uniqueness of each post-disaster scenario would make it impossible to provide a one-size-fits-all solution. It is simply trying to show the many lessons that can be learned from vernacular architecture and how they could be applied.

The aim of the thesis is to draw links between post-disaster architecture and vernacular architecture, using the Philippines as the area of focus. The structure can be roughly divided into two parts: research and design. The first three chapters set the scene and define the areas of focus. Chapter 4 begins to summarise the research and show the links between successful post-disaster recovery and vernacular architecture. Finally, Chapter 5 exemplifies the research findings with the design of transitional structures that could be found in a post-disaster scenario.

To begin the thesis, we must first determine what makes postdisaster recovery successful. In doing so, the thesis will form a set of criteria to compare with the qualities of vernacular architecture. Chapter 2 defines post-disaster architecture before proceeding to establish this criteria. It discusses the role of architecture in contributing to the success of post-disaster operations. At the end of the chapter, it focuses on shelters in the mid-term stage of relief and provides case studies, which will inform the design brief developed later.

In a similar manner, Chapter 3 first defines vernacular architecture and, more specifically, explores how we can learn from it. It then outlines the reasons for focusing on the Philippines due to its susceptibility to disaster and its deep architectural traditions. The chapter presents a brief history of Filipino vernacular architecture, which is summarised through a series of abstract drawings that attempt to answer the question: what is Filipino vernacular architecture?

From Chapter 4 onwards, the research is brought together through mind maps and a design exercise of three structures that are inspired by the different attributes of Filipino vernacular, thereby demonstrating the connection between vernacular architecture and post-disaster recovery.

Figure 2

Early thesis planning, February 2024

Defining

Humanitarian Architecture What makes postdisaster recovery successful?

The role of architecture

Prefabrication and Community Participation

Focusing on Transitional Shelters

Transitional Shelters: Case Studies

Quotes from “Transitional Shelters Eight Designs” produced by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC, 2012)

Broadly speaking, “humanitarian architecture” is defined as architecture that seeks to improve a humanitarian crisis, whether it arises from conflict, natural disaster, poverty, or disease. The term is often used interchangeably with “disaster relief architecture” or “post-disaster architecture,” which is an umbrella term encompassing various shelters that survivors may inhabit after a disaster. Emergency shelter, temporary housing, transitional shelter, and permanent housing are all examples of shelter typologies in the rehousing process.

While the terms can overlap and are sometimes used interchangeably, the different shelters are typically categorized into three temporal stages: emergency relief, mid-term relief, and permanent relief (Hollmén, 2023; IOM et al., 2012). This chapter will break down these three stages to better define the focus area later in the thesis.

“In some locations such as camps where there is no planned end state, shelters cannot be “transitional“, and temporary shelter must have a long duration.”

“The term T-shelter can mean either Temporary shelters or transitional shelters. This overlapping definition can provide flexibility when the terms temporary or transitional may be politically unacceptable.”

“In some countries the term “transitional shelter“ may become unacceptable, especially where reconstruction on a permanent site is possible. These shelters can be called progressive shelters.”

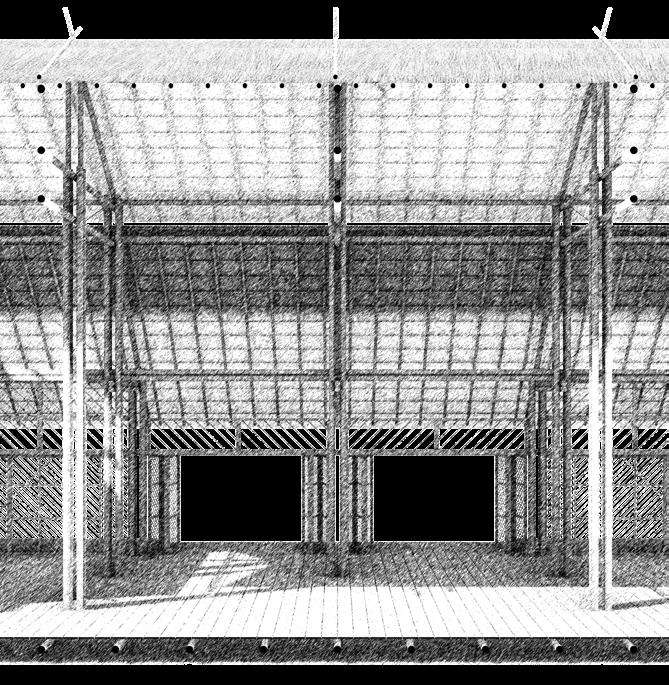

4 Shelter Definitions illustrated by the IFRC

by Shigeru Ban Architects

Aalto University’s WiT Programme is a programme that focuses on training professionals for the humanitarian field. They define emergency relief as the “immediate response to life-threatening conditions,” and IFRC states that the priorities in this stage are speed and limiting costs (Hollmén, 2023).

These structures often take the form of plastic tents provided by NGOs such as the UNHCR, and their primary purpose is to protect survivors from the elements. They are generic, compact, and lightweight structures that are made to be assembled quickly. Emergency relief can also be in the form of existing buildings. In some cases, buildings that are safe to inhabit for survivors are converted into shelter. This is more commonly seen in urban areas where public buildings such as schools, gymnasiums, and community centres can provide survivors with immediate shelter if their homes are uninhabitable.

According to the IFRC, the ideal length of stay in these shelters is between a few days to 3 weeks, but in many cases, people are forced to stay for much longer due to a lack of resources or political reasons (Hany Abulnour, 2014; IFRC, 2012).

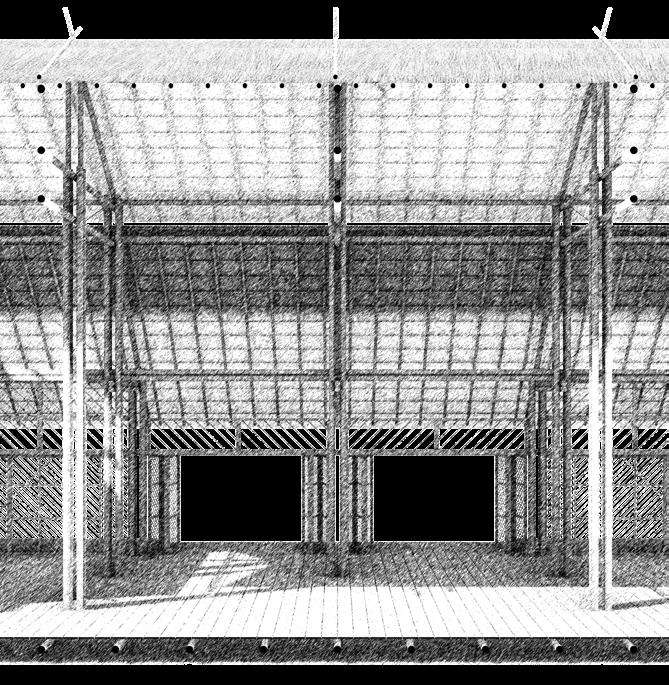

Figure 6

Figure 7 Figure 8 Emergency shelters for Rohingya refugees Shelters in Tacloban, Philippines following Typhoon Haiyan 2013

Shelters in the mid-term stage house survivors while they wait for a permanent solution. In his article “The Post-Disaster Temporary Dwelling: Fundamentals of Provision, Design, and Construction,” published in the HBRC Journal, scholar Adham Hany Abulnour defines the “temporary house” as a shelter with the purpose of supporting the survivors’ transition from the emergency phase to a more normal mode of living, where daily activities such as work, cooking at home, school, and shopping can occur. He mentions that if these structures provide a high-quality standard of living, they can evolve into permanent solutions (Hany Abulnour, 2014).

The term “transitional shelter,” however, carries its own specific meaning, which has become more popular in use since 2004 (IFRC, 2012; Sanderson et al., 2014). The IFRC defines transitional shelters as “rapid, post-disaster household shelters made from materials that can be upgraded or reused in more permanent structures, or that can be relocated from temporary sites to permanent locations. They are designed to facilitate the transition by affected populations to more durable shelter” (IFRC, 2012). The Transitional Shelters Guidelines add to this definition two characteristics: the ability to be resold to generate income to assist with recovery, or recycled for reconstruction (IOM et al., 2012). The IFRC also adds the following to their definition:

“Transitional shelters respond to the fact that post-disaster shelter is often undertaken by the affected population themselves, and that this resourcefulness and self-management should be supported.”

This encouragement for resourcefulness and self-management is an aspect that will be further explored in the following chapters. Therefore, to be defined as a transitional shelter, the shelter must meet one of these five criteria: able to be upgraded, reused, relocated, resold, or recycled. This is what sets it apart from other solutions in the mid-term relief that are typically discarded after use.

Core or progressive housing is another form of an evolving mid-term shelter. The shelter starts with a “core” and over time extensions are added to the house incrementally, usually in line with the financial situation of the family. Similar to transitional shelters, they have an evolving nature and can be reused or upgraded. The key difference is that, unlike transitional shelters, the core house is the permanent home in all stages of its evolution.

TRANSITIONAL SHELTER CRITERIA

CORE SHELTER CRITERIA

UPGRADED REUSED

The criteria for what defines a transitional shelter or core shelter can overlap. In reality, the distinction between the two can at times be blurry but most important to is that both definitions address the structures’ use after the survivors’ temporary needs are met, whether it be transforming into the permanent home or generating income for afflicted communities.

12

Criteria for mid-term relief shelters

Permanent relief simply refers to durable and permanently sited structures. This could be a house that withstood the disaster, a renovated home, or a completely new construction (Hany Abulnour, 2014). Permanent housing is typically sited on or close to the survivors’ original homes. In some cases, relocation is necessary (though usually undesired by survivors) due to political reasons or in cases where the site of the original homes has been badly damaged by the natural hazard, making it unfit to build on.

Typically, once survivors are able to acquire permanent housing, the post-disaster rehousing process can be considered complete. However, as the following chapters will expand upon, the rehousing process is not a simple step-by-step procedure, and in many cases, survivors are required to wait unexpectedly long periods of time before they can transition into permanent housing.

Some scholars question the necessity of categorizing them, arguing that such distinctions have resulted in “redundancy, lack of coordination, fragmented distribution of aid, and wasteful uses of resources” (Lizarralde et al., 2009). These categorizations can also give the illusion that the rehousing process is a simple and linear three-step checklist which survivors must complete to ‘recover.’ This could not be farther from the truth. As the rest of the scholarship and the thesis will underline, post-disaster rehousing should truly be viewed as a process.

However, categorizing the shelters in somewhat rough temporal stages is still useful from the architectural design side. The issues that scholars refer to are usually rooted in the planning, political, and financial side of the discourse. From the architectural side, it is clear that survivors have specific needs at different stages of their rehousing process, and this must be reflected in architectural design. For example, it would make little sense to design something costly and time-consuming in the earlier stages, where an urgent response is required to preserve life. The shelter’s design must be functional for the temporal stage that it will be designed for.

In order to discover how architecture can contribute to the success of post-disaster recovery efforts, we must first define what makes post-disaster recovery “successful.” Departing from this definition, we can then formulate criteria from which the thesis can start to develop a framework for successful postdisaster recovery, focusing on how architecture can contribute to these criteria and inform the rest of the thesis.

It is easy to see post-disaster architecture as a physical product that responds to disaster. In reality, the rehousing process is much more complex than a step-by-step procedure of moving survivors through different shelter types—from emergency to temporary housing, and then to a permanent solution. It should instead be viewed as a process of improving predisaster conditions in an effort toward long-term sustainability, development, and disaster risk reduction (Lizarralde et al., 2009; Davis, 2006).

Therefore, successful post-disaster recovery is inextricably linked to the concept of sustainability. This concept is crucial because it is concerned with how post-disaster operations impact afflicted communities in the long term, well after the disaster has passed and external aid has been withdrawn. In essence, the goal of post-disaster operations is not to be a temporary fix that appears to work but eventually reveals problems that leave communities more vulnerable than before. Conversely, post-disaster operations should serve as a catalyst for development, making communities more resilient than they were prior to the disaster. Here, sustainability can refer to environmental, economic, and social sustainability, which, as this section will show, are all interrelated.

Disasters occur when a hazard is of a certain magnitude that the community is unable to cope with the losses and damages with its own resources, thereby needing external aid. However, disasters, while tragic, can provide a rare opportunity to re-plan and improve the systems that were originally in place (Lizarralde et al., 2009; Abrahams, 2014). In fact, the reconstruction process should go beyond solving the immediate effects of the disaster and should work to decrease vulnerability and increase access to resources to a level higher than that prior to the disaster (Lizarralde et al., 2009).

However, due to the urgency of post-disaster operations, humanitarian actors often do not (or are unable to) shift into this mindset of long-term planning, instead putting their focus and energy on producing a fast response (Abrahams, 2014). This can happen due to political issues, where governments want to appear to be quickly responding to the disaster (Lizarralde et al., 2009; Su & Le Dé, 2020). While there is undoubtedly a need for speed in these operations, issues can arise in the long term if sustainability is not addressed.

An article by Daniel Abrahams, published in the publication Disasters, contains a case study of a transitional shelter in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake. In his findings he concludes that post-disaster operations that do not consider environmental sustainability risk worsening the impact of a disaster and slowing long-term recovery efforts, thereby reducing disaster resilience (Abrahams, 2014). Building on past research, Abrahams (2014) provides a definition of environmental sustainability to strive for in the post-disaster context:

“Sustainable post-disaster activities provide resources to affected citizens to ensure health and safety and to promote redevelopment, without causing further damage to land or existing structures, exacerbating the impacts of the disaster, or placing undue stress on the natural environment.”

DISASTER OCCURS

POST-DISASTER REHOUSING SHOULD BE VIEWED AS A CONTINUED PROCESS INSTEAD...

DISASTER OCCURS

EMERGENCY, TEMPORARY, TRANSITIONAL, CORE ETC.

CONTINUED DEVELOPMENT

SECURE HOUSING ACQUIRED

This definition again highlights the essential shift from viewing rehousing as a step-by-step program to a fluid process of redevelopment that continues after the disaster.

To speak about development and improving access to resources automatically implies an economic impact. The term “The Shelter Effect”, coined by the IFRC, refers to the idea that post-disaster shelters can become catalysts for community development, particularly in developing countries. The IFRC’s short film showcases how a well-designed disaster-resilient shelter can have a ripple effect on the income of one household and slowly snowball into many community developments (IFRC, 2010).

Another important aspect of sustainability is social sustainability. For post-disaster recovery efforts to be successful and sustain the level of development well after external aid has gone, humanitarian organizations must be sensitive to the cultural needs and local conditions of a community and place. The issue is that humanitarian response involving external actors has often been a top-down approach, meaning decisions are made at the governmental level rather than the local level. This can mean that certain cultural needs and local conditions are not recognized (Hany Abulnour, 2014; Felix et al., 2013).

Figure 16

Diagram of contrasting views of the rehousing process

There is also the issue of a cultural gap that occurs when these disasters, typically occurring in the Global South, are responded to by external aid from the West. While many organizations are trying to address this, external actors may not fully grasp the realities of the survivors. Davis observed that there was widespread ignorance by relief agencies of local cultural values and assumptions that their housing models were superior to the local ones (Davis, 1981). While this narrative seems to be changing, the bias may still exist that technologies from the West are superior and that local traditions are inferior, even among local people who can be influenced by the media (Jigyasu, 2009; Davis, 1981).

Regardless, it is clear and supported by research (Oliver, 2006; Potangaroa, 2015; Sliwinski, 2009; Dy & Naces, 2016) that sincere attention to the cultural and local conditions of a place, especially by foreign actors, leads to acceptance by the community, ensuring that proposed solutions will last.

Another aspect of social sustainability is user satisfaction. It is evident that the community’s level of satisfaction with a postdisaster project is linked to the project’s sustainability. Regan Potangaroa, an expert in the post-disaster field, has found through his fieldwork and research that the happiness levels of a community after a disaster are closely related to their longterm resilience and ability to self-support. In his work, he interviewed survivors and measured their responses using the DASS scale. The research demonstrated that there is a tipping point on the DASS scale where, if humanitarian aid succeeds in bringing the score up to 7 (a score based on the ratio of

happy to unhappy responses), communities will become selfsustaining and happy (Potangaroa, 2015).

In summary, post-disaster operations can be considered successful when they meet certain aspects of environmental, economic, and social sustainability. Based on these concepts of sustainability, a set of criteria for successful post-disaster operations can be formed:

Increases a community’s resilience and reduces pre-disaster vulnerability levels.

Improves a community’s access to resources.

Is culturally and locally sensitive.

Spurs economic development.

Is environmentally conscious.

Satisfies users.

So, how does architecture fit into the picture? The next two chapters explore different architectural aspects and how they can meet these criteria to contribute to the success of postdisaster recovery efforts.

If one were to search the term “post-disaster architecture” on Google, they would find images of a wide variety of structures, ranging from small shelters to large housing units. These small shelters, which are often intended to address the emergency and mid-relief stages, are frequently designed to be replicable, prefabricated, and high-tech solutions. Moreover, this recurring image of small, high-tech shelters often originates from academics or practitioners based in Western countries and institutions.

While high-tech solutions can undoubtedly serve their purpose well, Ian Davis, author of Disasters and the Small Dwelling, critiques this approach. He argues, “Inevitably such instant shelters appear to have more to do with the needs of those who generate the concepts and precious little with the harsh, pressing shelter needs of survivors who need far more than physical protection, especially when it arrives in a novel shape” (Davis, 1981). This critique is especially relevant in the postdisaster context. Disaster survivors often lack familiarity with advanced architectural concepts, particularly those developed abroad. Coupled with their vulnerable situation, this makes familiarity a crucial consideration in shelter design. Careful

RECOVERY = SUSTAINABILITY

ENVIRONMENTAL

ECONOMIC CULTURAL

CRITERIA FOR SUCCESSFUL RECOVERY

1. INCREASES A COMMUNITY’S RESILIENCE AND IMPROVES PRE-DISASTER VULNERABILITY LEVELS.

2. IMPROVES A COMMUNITY’S ACCESS TO RESOURCES.

3. IS CULTURALLY AND LOCALLY SENSITIVE.

4. SPURS ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT.

5. IS ENVIRONMENTALLY CONSCIOUS.

6. SATISFIES USERS

attention must be paid to survivors’ local ways of life and cultural contexts.

The role of architects in post-disaster scenarios should not be viewed as that of top-down solution providers. As Lizarralde et al. suggest, architects have a responsibility to identify their role in addressing social challenges. They must “develop the expertise required to respond to those problems and link ethical, functional, and aesthetic considerations” (Lizarralde et al., 2009).

In his extensive experience with post-disaster scenarios, Regan Potangaroa found that with the right technical support—particularly from architects and engineers—affected communities are capable of achieving the outcomes they desire (Potangaroa, 2015).

This chapter explores how various aspects of architecture can contribute to meeting the criteria established in the previous chapter.

ROLE OF ARCHITECTURE

CULTURALLY SENSITIVE DESIGN

CONSTRUCTION: MATERIAL CHOICE, TECHNOLOGIES, AND SELF-BUILDING

RESILIENT AND ADAPTABLE DESIGN

PLANNING FOR THE AFTERLIFE OF TEMPORARY SHELTERS

Figure 19 Simplified model illustrating successful post-disaster recovery.

The issue with the prefabricated, high-tech models that dominate a Google search for “post-disaster architecture” lies in their limited scope. While these models may function adequately to provide physical protection from the elements, they fail to acknowledge a fundamental truth: a shelter must also provide a home.

There is a widespread misconception that, under the extreme pressure of post-disaster conditions, people are willing to abandon their normal patterns of living or traditional forms of dwellings and accept any solution provided to them. However, research and experience show that this assumption is false (Davis, 2006; Davis, 1981; Abrahams, 2014; Potangaroa, 2015). Numerous cases illustrate how post-disaster homes designed and distributed by humanitarian organizations have been abandoned by survivors. This rejection is often rooted in a lack of sensitivity to the cultural and local contexts of the affected communities (Dy & Naces, 2016; Lizarralde et al., 2009).

A shelter must go beyond the provision of physical safety; it must enable survivors to feel socially integrated and regain a sense of belonging. During such vulnerable times, a house often becomes a source of pride and cultural identity. In many cultures, the home carries symbolic importance far exceeding its role as a mere physical structure (Felix et al., 2013).

This reality raises an important question: are external actors equipped to intervene in culturally complex environments outside their own? Paul Oliver asserts that post-disaster relief is one scenario where external intervention is not only appropriate but also “requested, necessitated, even demanded” (Oliver, 2000). However, it is critical that organizations understand that cultural considerations are not secondary concerns but are, in fact, integral to ensuring the sustainability and success of post-disaster shelter projects.

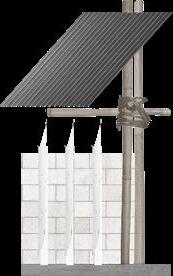

The topic of cultural sensitivity is closely linked to the choice of materials and technologies used in the construction of shelters. The question of using local materials as opposed to imported ones is a choice that is linked to environmental, economic, and cultural sustainability.

By using local materials in post-disaster shelters, costs and delays in transportation are significantly reduced. Additionally, local knowledge of these materials facilitates the involvement of the local workforce, which can spur potential economic benefits and encourage cultural integration (Daniel Félix et al., 2013). Modifications and maintenance of such shelters are also easier, as they rely on local expertise rather than requiring external aid or specialized knowledge often necessary for hightech prefabricated solutions (Daniel Félix et al., 2013).

The concept of self-building and self-maintenance is crucial for long-term sustainability, as communities take charge of their own recovery (GFDRR, n.d.; Potangaroa, 2015; Félix et al., 2013). Scholars have also recognized the value of indigenous and traditional construction processes, which embody centuries of accumulated local knowledge. Such methods are often welladapted to local conditions and may even offer greater disaster resilience compared to modern technologies (Félix et al., 2013; Jigyasu, 2009).

In one case study, informants reported that even if atypical structures, such as plastic modular houses, were less expensive and environmentally sustainable, they would still avoid using them. A related issue with imported materials is their local value or perception. For example, survivors in the Philippines reported feeling safer in lightweight, traditionally constructed shelters rather than concrete structures, fearing that concrete buildings might collapse on them. Additionally, high-tech materials can have significant local economic value, leading survivors to sell them rather than use them to construct shelters (Architecture for Humanity, 2006).

The use of local materials and low-tech solutions is advantageous in terms of environmental, economic, and social sustainability. However, a suitable solution often requires a trade-off between traditional and modern technologies. In Rebuilding After

Disasters: From Emergency to Sustainability, Rohit Jigyasu discusses how optimization, rather than maximization, may be ideal. For instance, while a reinforced concrete box might maximize earthquake safety, it could fall short on other important aspects such as climate adaptability, cultural compatibility, and community familiarity. A balanced trade-off between traditional and modern approaches is often necessary (Jigyasu, 2009). It is important to avoid romanticizing local materials without considering the clear advantages that modern materials can sometimes provide or acknowledging the shortcomings of traditional methods. A pragmatic approach that balances these considerations is essential.

With this topic also comes a discussion around self-building, community participation, and prefabrication. This will be covered in more depth in the following chapter.

Figures 22 and 23 Emergency shelters designed for UNHCR by Shigeru Ban.

Post-disaster projects often emphasize the resilience of a community, but resilient design is equally critical.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “resilience” as:

1. The ability to withstand or recover quickly from difficult conditions.

2.The ability of a substance or object to spring back into shape; elasticity.

In the long term, modifications to shelters are inevitable. This is why local materials and low-tech construction methods are advantageous. Since these shelters are usually located in disaster-prone areas, they must be prepared to withstand recurring natural hazards. In the event of wear or damage, the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) recommends the use of materials and technologies that can be easily repaired (GFDRR, n.d.).

Resilient design, where parts of a shelter can be replaced, reused, or repaired, is especially beneficial in the post-disaster context, where conditions are rapidly evolving. Many organizations advocate for the use of materials that can be re-purposed in the construction of permanent housing, promoting shelter designs that are either modifiable or de-constructible.

Another critical factor these shelters must address is site and land issues. A common problem, particularly with mid-term shelters, is that the original site may no longer be safe for construction, forcing survivors to relocate as mandated by the government. This is especially prevalent in coastal areas. Furthermore, issues related to land ownership can arise, sometimes requiring relocation once a lease period has expired. However, survivors typically prefer to remain in or near their original homes due to familiarity, economic ties, and socio-cultural reasons (Hany Abulnour, 2014; Davis, 2006). For instance, the livelihoods of many coastal communities are tied to fishing-related activities such as fishing, selling and processing fish, boat-building, and net-making. Relocation can disrupt these activities, potentially leading to significant economic setbacks.

A study conducted in Sri Lanka in 2005 after a tsunami sheds light on survivors’ preferences (Asquith & Vellinga, 2006). Survivors were asked to rank their priorities for shelter. Their highest priority was to remain as close as possible to their damaged or ruined homes and their means of livelihood. In contrast, the three lowest-ranked priorities were:

- Occupy emergency shelters provided by external agencies.

- Occupy tents in a camp-site.

- Be evacuated to a distant location.

This research highlights the strong identification families have with the location of their homes. Survivors often prefer to live in crowded situations, sharing space with relatives and friends, rather than accepting temporary shelters or tents offered by external aid organizations. Consequently, post-disaster architecture must be prepared to address the possibility of relocation and be adaptable to various site conditions.

city 2010

One of the issues in post-disaster design is the lack of planning for the units’ destiny after they serve their purpose (Felix et al., 2013). In many cases, these units are still usable, but without proper planning, they are demolished without concern for possibilities of reuse or recycling.

For example, following the 1999 earthquake in the Colombian city of Armenia, 6,000 units of temporary shelters were not planned for use after survivors had transitioned into permanent housing, leading to large amounts of timber and iron being trashed, stored, or lost (Lizarralde et al., 2009).

This highlights the benefits of evolving mid-term shelters, such as transitional shelters, core housing, or progressive shelters. For shelters to be defined as one of these types, they must meet the five attributes that consider the afterlife of temporary structures.

By designing shelters that have a use afterlife, architecture has the potential to contribute to environmental sustainability while also benefiting communities economically and promoting long-term development.

Through the previous chapters we have seen that the biggest driver of post-disaster recovery is sustainability and the ways post-disaster architecture can be a driver of sustainability in an environmental, social and economic way.

Summarising the research the thesis proposes the following six guidelines in how architecture can contribute to the success of post-disaster recovery efforts. These guidelines will be revisited in the section on vernacular architecture and will eventually guide the design of the structures.

Figure 25

Sheeting provided by USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance and distributed by NGOs after earthquake in Nepal

This section briefly addresses two topics that are often discussed in the post-disaster discourse: prefabrication and community participation. The general overview of scholarship surrounding the work suggests two main ideas: prefabrication is undesirable, and community participation is desirable. However, this chapter aims to interrogate these concepts to better understand their role in post-disaster operations.

One of the key criticisms of post-disaster architecture, as suggested in the prior chapter on materials, is that prefabrication should be avoided in post-disaster recovery. While the numerous advantages of local materials and building with the community have already been pointed out, should prefabrication as a concept be completely ruled out?

The current criticisms against prefabrication likely stem from the 1970s and 1980s, when heavy, mass-produced units were ill-adapted to the contexts they were designed for (Lizarralde et al., 2009; Johnson, 2009). They came with issues of high costs, high-tech solutions, and standardization, which meant a lack of attention to the specificities of a place, namely its climate, topography, local customs, and local forms of living. In cases where affordable housing was in constant demand, these temporary units would remain longer than planned. However, because they were high-tech solutions built by specialized contractors, ongoing maintenance by the local people proved difficult (Lizarralde et al., 2009; Johnson, 2009).

In the 2010 Haiti case study by Abrahams, informants reported that they chose local materials and purposely avoided prefabricated shelters for economic reasons:

“I would try not to do the prefabricated [shelters], just because I like to source commodities locally because you do get that cash injection into a local economy, which produces ripple effects and helps jumpstart businesses.”

-(Abrahams, 2014)

All of this has led to a lack of confidence in prefabrication and scepticism (Lizarralde et al., 2009). However, as Lizarralde argues, a systematic rejection of prefabrication in developing countries does not stand up to a cost-benefit analysis.

As an alternative to the heavy industrialization of the 1970s and 1980s, they suggest that the prefabrication of light elements could be beneficial from a cost-benefit point of view (Lizarralde et al., 2009).

With this in mind, an architectural solution could be a combination of prefabricated elements and local technologies, incorporating the best of both while also providing a cost benefit.

Figure 26 (left) Emergency Accommodation Units after Van Earthquakes, Turkey.

Figure 27 (right) Rural Housing Prototype in Apan - DVCH De Villar CHacon Architecture

The dominant narrative in post-disaster recovery is that the participation of survivors in the reconstruction process leads to a more successful operation. The former Office of the United Nations Disaster Relief Coordinator (UNDRO, 1982, p. 55) went as far as to state that: “The key to success ultimately lies in the participation of the local community – the survivors – in reconstruction.”

As nice as the bottom-up approach sounds, the reality is that this principle is hardly put into practice and faces many obstacles (Sliwinski, 2009). Community participation can come in different forms, and the way it is implemented can affect the outcome of the operation in various ways.

Firstly, community participation can refer to the community being involved throughout the planning, design, and construction phases. Participation can also take the form of decision-making or manual labour, sometimes referred to as “sweat participation” (Opdyke et al., 2019). Some scholars have contrasting views on the value of sweat participation, with some findings showing a positive correlation between participation and user satisfaction, while others suggest that this form of participation has little to do with the outcome (Lizarralde et al., 2009; Sliwinski, 2009; Opdyke et al., 2019).

However, many scholars agree on the benefits of involving the community in the earlier phases of strategy and planning (Opdyke et al., 2019). It can strengthen social relationships, benefit psychosocial recovery, and give survivors a sense of ownership over their recovery, leading to positive impacts in the long term (Su & Le Dé, 2020; Sliwinski, 2009). Four case studies in South America attributed their success to the careful coordination of involved parties (Sliwinski, 2009).

In any case, participation by locals is often linked to user satisfaction rather than the actual safety of the shelters (Opdyke et al., 2019). Research has suggested that participation in the design phase did not affect design (Rand, Hirano & Kelman, 2011; Sanderson et al., 2014). This is where the designer fills this expertise gap and can provide technical assistance to communities.

There is also the issue of assuming that communities, particularly in a vulnerable state, would be willing and eager to participate. Canadian anthropologist Alicia Sliwinski discovered in a postearthquake housing project with a community participation scheme that the “good neighbour” rhetoric is not always present and that social and hostile tensions between people can exist (Sliwinski, 2009).

Cultural concepts such as the Filipino spirit of ‘bayanihan’ can also influence levels of community engagement (Opdyke et al., 2019). This spirit of ‘togetherness’ and ‘collectivity’ is often romanticized, especially in the response to Typhoon Haiyan, with many commending the Filipinos’ resilience and ability to recover, attributing it to this spirit of bayanihan (Mangada & Su, 2017). However, these cultural concepts can sometimes be political ways of hiding the slow response and unpreparedness of governments (Mangada & Su, 2017). Surveys by Ladylyn Mangada and Yvonne Su found that while bayanihan did exist, it was rarely seen in more urban areas, and internal conflicts within communities existed.

These arguments do not mean to suggest that community participation is undesirable, nor that cultural concepts such as bayanihan do not have an impact. The spirit of community and resilience through togetherness is absolutely present in collectivist cultures such as the Philippines. It is simply highlighting that participation should not mean solely manual labour but also the involvement of the community in planning and decision-making. By doing this, communities can integrate important cultural aspects from the early stages, contributing to the project’s long-term success. It also clarifies the role of designers as specialists who can provide the technical expertise for communities to execute their desires. It is important that, going forward, one should not over-romanticize cultural concepts and expect communities to act in such generous ways, particularly under the circumstances of post-disaster. Ladylyn Mangada and Yvonne Su summarized it well: “Sometimes surviving is just surviving” (2017).

A group of men relocate a traditional Bahay

CULTURAL

As will be further discussed in Chapter 3, vernacular architecture goes beyond responding solely to physical and climatic factors. Culture, traditions, and the local way of life are intangible factors that also play a part in manifesting the built form.

One of the strongest cultural aspects that has persisted to this day in the Philippines is the nation’s strong community spirit. There is a term in Filipino, “bayanihan,” which refers to a concept of togetherness, cooperation, and unity. This cultural concept is important because it is an essential part of much Filipino vernacular architecture and is also important in postdisaster recovery.

As seen in the case studies of Filipino vernacular architecture, these structures are essentially communal. They are mostly one-unit dwellings for the entire family to occupy, with no real partitions for individual privacy. They are often added to or modified depending on changing family structures. The way that these structures are built to relate to each other through porches, overhangs, and communal outdoor spaces is another reflection of the togetherness among different families. These in-between spaces bring the living space outside but also extend the home to neighbors, welcoming them into the space and inviting discussion.

Even in the case of the Badjao houseboat, the concept of adoption to keep the boat running shows that the concept of family can go beyond blood relatives. In some cases, structures are even designed to host a number of different families, as is the case with the Maranao people, who sleep on sleeping mats in large multi-family halls.

Bayanihan is important because, in post-disaster scenarios, the topic of community participation is a major one, with many arguing that it can define whether post-disaster recovery will be successful or not. Knowing about bayanihan will impact the way that post-disaster structures should relate to each other, negate the need for many partitions and individual privacy, and encourage more communal spaces for communities to interact both indoors and outdoors.

The issue of the current humanitarian situation is that too often, the transitional phase becomes a permanent one, and many are unable to move to permanent housing due to a lack of resources and inability to build permanent, durable shelters.”

- IFRC, 2012

Due to the varying impacts of a disaster and political or financial factors, not all survivors will pass through each stage of housing (Johnson, 2009). Most sources recommend an assessment of the situation to determine whether it is appropriate or even feasible to construct transitional shelters with the resources available (IFRC, 2012; Hany Abulnour, 2014). For example, if the damage to a home is only minor, a rapid or partial rebuilding solution could allow survivors to move from the emergency shelters directly into permanent housing, negating the need for a transitional structure (IOM et al., 2012).

However, when the emergency phase has passed and permanent solutions are still far from being available, mid-term structures are required. Shelters in the mid-term relief stage have huge potential to positively impact the immediate and long-term well-being of survivors, thus meeting the criteria outlined in the previous two chapters. The rest of this chapter expands on the choice of the thesis to focus on designing transitional structures.

As mentioned previously, the reconstruction process is more than simply transitioning people from emergency to temporary housing and then to a permanent solution. It is about improving pre-disaster conditions and promoting the longterm prosperity and sustainability of a community.

Transitional structures, in particular, have great potential to contribute to the long-term development of a community. These evolving structures, which can be reused, resold, recycled,

upgraded, or relocated, continue to serve the community after their initial use as temporary homes. These five attributes have obvious financial benefits for a community. However, as this thesis will explore, transitional architecture can also improve a community’s resilience to future disasters, create more spaces that can adapt to changing needs, and allow survivors to benefit from the positive effects of self-building. All of these factors contribute to an improvement in a community’s access to resources, resilience, and, therefore, a reduction in vulnerability.

The research question at this point is: How can good design of transitional shelters improve a community’s resilience?

It is for this reason that, going forward, the thesis will focus on the design of transitional structures, specifically those that can evolve over time and continue to serve a purpose after their use as temporary residences. Unlike quick-response emergency shelters, these transitional shelters need to be more resilient and designed to support survivors for possibly months to years, given the likely difficulty in acquiring permanent housing. However, these shelters are not intended to be permanent. They should take on a semi-ephemeral nature, not replacing permanent housing.

This semi-ephemeral nature of transitional shelters is a quality that strongly links them to Filipino vernacular architecture, an aspect that will be further explored through the thesis.

Figure 29

Authors diagram of thesis focus in the rehousing process

Although they may be designed for the mid-term stage of relief, these structures have the potential go beyond the transitional stage and remain as permanent structures. For example, they could be repurposed for another function or donated to another community in need. This kind of adaptability that allows the structure to move through the different stages of relief is exactly the quality that can trigger long-term sustainability.

WORKS BY SHIGERU BAN

On September 17, 1995, in light of the Great Hanshin earthquake, a temporary church building known as the “Paper Dome,” made of paper tubes, was designed and built pro bono by Shigeru Ban for the Takatori Catholic Church in Kobe, Japan. After the Takatori parish community decided to build a larger, permanent church building, the “Paper Dome” was deconstructed in 2005. Arrangements had been made to donate it to a Catholic community in Nantou County, Taiwan, which had suffered from the 921 earthquake on September 21, 1999. The parts were shipped to Taiwan in 2006, and after two years of planning, they were reconstructed at the new site in 2008. The reconstruction took four months, and it is now used as a place of worship as well as a tourist attraction.

Similarly, in February 2011, the city of Christchurch, New Zealand, was struck by a 6.3 magnitude earthquake that caused significant damage to the city’s infrastructure. One of the damaged buildings was the iconic Christchurch Cathedral, an Anglican cathedral in the central city and a major tourist attraction. Ban was invited to design a temporary cathedral that would host events and church services while awaiting the original cathedral’s reconstruction (Barrie, 2013). Erected in 2013, the Cardboard Cathedral was originally named the transitional cathedral because of its intention as a temporary structure. Due to its success, it was decided that it would become a permanent structure for The Parish of St. John (Barrie, 2013). The Lonely Planet, a popular travel guide publisher, named Christchurch in the top 10 cities to visit, with the Cardboard Cathedral as one of the key attractions.

There are some questions around the cost-effectiveness of Ban’s work (Architecture for Humanity, 2006), and critics may speculate about how much of the success of these structures can be attributed to his status as an internationally renowned architect. Regardless, both of these examples showcase the potential of temporary structures to have a purpose even after a community has completed the transition to a permanent solution. What were meant to be stand-in places of worship have unexpectedly become major attractions in their respective cities, showing the huge impact post-disaster structures can have even after serving their initial purpose.

Additionally, while post-disaster projects are typically focused on housing units, these examples highlight the need to also respond to the cultural and communal needs of survivors, in this case, providing spaces for religious worship.

Figure 30 (left)

Paper Church in Kobe, designed as a temporary cultural and religious structure.

Figure 31 (right)

Transitional Cathedral designed as a temporary church.

This chapter looks at case studies of shelters in the mid-term relief phase in the Philippines. Due to the uniqueness of each post-disaster scenario, these case studies will provide a basis for what can be expected in terms of site, materiality, cost, and timeline.

This information will then serve as a point of departure when forming the brief for the design stage in later chapters. Each case study has been summarised in terms of materiality and key architectural descriptors. At the end of the chapter, these will be compared against each other, and an “average” will be formed to indicate what is most common or effective in terms of design solutions.

In the end, it will be a combination of the following factors that form the guidelines for the design project:

1. Case Studies

2. Guidelines on materials and processes from Humanitarian Organisations

3. Studies on Filipino Vernacular Architecture

CS01

CS08

CS03

CS04

CS05

CS06

CS02 Indonesia

KEY DESCRIPTION:

Core house structure intended to become a permanent home. Inspired by local rural houses. The core strucure was made of heavy construction while the adjacent part was made of lighter materials, both parts designed to last 20 and 10 years respectively.

Hybrid construction of Interlocking Compressed Earth Block (ICEB) for the core and treated coconut timber and amakan walling for the adjoining room. Materials sourced locally. Technology was familiar as it was already used in the region prior to the project

Coconut timber and amakan walling were replaceable and many families modified the design or built extensions for small kitchens. Fostered a sense of ownership and inclusivity in the design.

High costs meant it reached a relatively low number of beneficiaries (roughly 30% of the targeted afflicted population).

KEY DESCRIPTION:

Transitional, one space shelter built from locally procured, durable, coconut timber. Designed by architects and engineers and inspired by vernacular Filipino houses, well adapted to the tropical climate protecting from the heat and rain.

Elevated shelters anchored on reinforced concrete footings instead of concrete foundations eased land-owner worries concerning irreversible damage to their property.

Raised structure assists with passive ventilation and keeping water and vermin away out. Raised structure meant issues of accessibility for elderly and less-abled.

A shelter can be carried from one place to another by 20 persons or can be easily dismantled and re-erected in another location. Shelter can be easily upgraded into permanent homes, disassembled to make adjustments.

KEY DESCRIPTION:

A core shelter with a built-in toilet constructed from materials available at the local market. A coconut timber structure with amakan walling atop concrete footings and covered by a hipped corrugated iron roof.

Culturally appropriate design was widely accepted by beneficiaries and occupants reported they felt safer in this structure.

Initially difficult to involve the affected people as they were in a distressed state. Over time, participatory activities and focus group discussions built stronger cooperation within the community. To avoid more stress, beneficiaries contributed to the construction process while the NGO managed technical support, material delivery and overall monitoring.

Some components were prefabricated to ensure construction quality, particularly wall panels and structural footings.

KEY DESCRIPTION:

A single room transitional shelter constructed from traditional light materials. Use of amakan for walling and nipa for roofing provided excellent ventilation for shelters.

Has a gable roof with short overhangs to limit upward lift. Large concrete footings were used to level structures on slopes and difficult site conditions.

Most fisherfolk within the transitional site preferred to return to their original community because of unfamiliar fishing grounds near the transitional site. The transitional site was an hour away from the original location proving difficult for work and school.

Communal toilets were constructed alongside the shelters but due to poor maintenance they became unusable. Designed to last only a couple of years then being given to the land owners for private rental and use.

KEY DESCRIPTION:

Constructed from timber trusses, amakan walling, a hipped corrugated iron roof on concrete footings. Includes a small porch and two entrances. Steel straps on roof edges tied the structure down to concrete footings.

Government prevented community from returning to original sites due to them being located in a no-build zone. Permanent homes to be constructed on the same site as the transitional shelters.

Households lived in a tent for a year prior to acquiring these transitional shelters.

Common transitional spaces such as a large bunk house, social centre and basketball courts were also constructed.

Sanitation infrastructure was poorly maintained resulting in households constructing their own unlined pits.

KEY DESCRIPTION:

Owner-driven approach to shelter design. Each household was assisted by architects and engineers to design their own homes according to vernacular design principles. Designed to be core houses that could expand.

Shelters were designed to meet typhoon-resistant standards. So that in the case of future destruction, families would have a core shelter to build back from. Designs were raised or followed the bahay na bato principle of a heavy base and a lighter upper part.

Meaningful community involvement and decision making empowered households in controlling their recovery. Workshops on building, financial literacy and management reinforced this.

Sometimes weaker and cheaper alternatives should be used to encourage replicability.

KEY DESCRIPTION:

The structure is a bamboo frame with that holds a hipped roof of terracotta tiles. The walls are made of woven bamboo and the floor is raised on bamboo joists and panels. The structure is braced with diagonal bamboo members on every side.

Some communities recovered very quickly as they already had knowledge on how to build with bamboo.

The frames connections are pinned with bamboo pegs and secured with rope. Roofing and flooring are fixed with nails.

Once permanent homes were acquired, transitional shelters became kitchens, sheds, small shops, workshops and storehouses.

The project was built on the Javanese self-help culture of gotong royong, a concept similar to that of the Filipino bayanihan that promotes working together towards a communal goal.

KEY DESCRIPTION:

The paper log system was used in conjunction with local materials such as nipa for the gable roof and amakan for the walls. The paper log system by Shigeru Ban is designed to be easily constructed with little time and people required.

The shelter is a hybrid of Shigeru Ban’s paper log system and traditional materials such as nipa for the roof and amakan for the walls. A plywood floor sits atop a foundation of crates filled with bags of sand.

The amakan walls allow light to filter into the space and openings of the awning type allow air and light to pass through the space.

Under the nipa roof is a layer of plastic sheeting which likely serves to protect from heavy rain.

CS01

DISASTER:

HOUSEHOLD SIZE:

TIME TO BUILD:

LIFESPAN:

AREA PER UNIT:

AREA PER PERSON:

COST PER UNIT (USD):

SITE CONDITIONS: (RELOCATION?)

COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION:

KEY ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTIONS:

Typhoon Haiyan, 2013

5,4 people

6 months for 600 units

10-20 years

17,5-21 sqm

3,5 sqm

$5160

No legal status or proof of land ownership. NGO assisted in securing documentation and relocating singular households or small groups from unsafe zones to nearby plots.

A handbook with 3D drawings was distributed to show households how to build their own homes. Some households needed support during construction and making design decisions.

Inspired by common rural houses from the area.

Flexible design to allow for extension and modifications suiting family’s needs.

Built to resist seismic loads of up to 7.2 on Richter scale and 200km/hr wind load.

Tropical Storm Washi, 2011

5 people

2-3 days

5 years

18 sqm

3,6 sqm

$410

Prone to flooding, near the riverbanks. If low-medium risk, households were sited in their original neighbourhood. If land owenership issues arose in the future, structure could easily be moved.

-

Combines traditional materials (locally procured coconut timber, bamboo and amakan walling) with modern materials such as concrete footings and corrugated iron roofing.

Can easily be dismantled, relocated and upgraded.

Typhoon Haiyan, 2013

4,1 people22 sqm

5,4 sqm

$2240

Coastal areas, structures were built above ground to prevent flooding.

Beneficiaries without land were relocated but within the same area.

Initially difficult to involve beneficiaries as they were in a distressed state. However, through focus groups and participatory activities, cooperation become stronger.

Structurally designed to withstand 200km/hr winds.

A hybrid design using traditional materials locally sourced and corrugated iron and concrete footings.

Some shelters included ramps for accessibility.

Typhoon Haiyan, 2013

5,4 people

3 months for 86 units 10 years$1333

The coastal transitional site was one hour away and many families spent large income on commuting to work and school. Fisherman were unfamiliar with the new fishing grounds.

Typhoon Haiyan, 2013

Raised concrete footings helped tackle slopes and difficult terrain.

Constructed from light materials due to expected short life-span.

Good ventilation thanks to nipa roof and amakan wall panels.

2 months for 133 units

Government prevented community from returning to original sites due to them being located in a no-build zone. Permanent homes to be constructed on the same site as the transitional shelters.

Includes a small porch and two entrances. Steel straps on roof edges tied the structure down to concrete footings.

Some households used plastic tarp to cover amakan walls to protect from rain which reduced ventilation.

Ramps for accessibility.

CASE STUDY

SUMMARY

DISASTER:

HOUSEHOLD SIZE:

TIME TO BUILD:

LIFESPAN:

AREA PER UNIT:

AREA PER PERSON:

COST PER UNIT (USD):

SITE CONDITIONS: (RELOCATION?)

Typhoon Haiyan, 2013

5 people11,5-23 sqm

4 sqm

$2250

Earthquake, 20093,5 days per unit 1-5 years 24 sqm$695

Mostly coastal sites, some inland. Coastal, Inland.

COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION:

KEY ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTIONS:

Indigenous communities were involved from the early stage, in planning their homes and managing the construction in an owner-driven design approach. Architects provided technical support.

Beneficiaries were indigenous communities so vernacular design principles were culturally important as well as practical.

A mix of traditional and modern materials were used. Corrugated iron, nipa, plywood, amakan and concrete blocks could be combined.

Some communities were able to construct shelters very quickly thanks to their familiarity with bamboo construction.

The structure is a bamboo frame with that holds a hipped roof of terracotta tiles. The walls are made of woven bamboo and the floor is raised on bamboo joists and panels. The structure is braced with diagonal bamboo members on every side.

CS08 TRANSITIONAL SHELTER

Typhoon Haiyan, 2013

1 day

Coastal.

The structure was constructed by volunteers (some locals).

CS09 TRANSITIONAL SHELTER (ADDITIONAL DATASET)

CS10 TRANSITIONAL SHELTER (ADDITIONAL DATASET)

The shelter is a hybrid of Shigeru Ban’s paper log system and traditional materials such as nipa for the roof and amakan for the walls.

A plywood floor sits atop a foundation of crates filled with bags of sand.

Typhoon Haiyan, 2013

4,8 people4 years 24 sqm 5 sqm

$1960

Soft earth. Built on resettlement sites.

Some households had to relocate as they were located in no-build zones.

Carpenters and assistants came from local communities which generated a source of income.

Community participated in construction and distribution of kits.

Made of coconut timber, amakan walling and corrugated iron roofing.

People personalised their shelters adding small stores and temporary structures outside for livelihood activities.

Typhoon Haiyan, 2013

5 people19,4 sqm

3,9 sqm

$3500

Were able to rebuild in the same location.

Could easily be disassembled meaning less problems if the structure had to be relocated in case of land ownership issues.

Community identified their priorities through participatory workshops.

Beneficiaries were in charge of the storage and safety of construction materials.

Used prefabricated trusses.

Followed the Build Back Safer guidelines provided.

Latrines also constructed considering privacy and security (no gaps in the lower part, locks and close proximity to the shelters).

While varied, a comparison of the case studies data can help to form a rough idea of what can be expected in constructing post-disaster shelters. As expected, many of the findings are in line with the research findings from the previous chapters.

Factors such as costs are difficult to form an average from mainly due to the uniqueness of the scenarios. These costs are usually made up of the cost of materials and the cost of delivery which can both differ greatly depending on the area of the intervention and their access to markets.

It is clear however that the shelter should be relatively simple to construct so that community members, with guidance, can build their own homes. The case studies also show the need for other spaces other than the home, for example, gathering spaces and communal latrine blocks.

DISASTER:

HOUSEHOLD SIZE:

TIME TO BUILD:

ANTICIPATED LIFESPAN:

AREA PER UNIT:

AREA PER PERSON:

SITE CONDITIONS:

COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION:

KEY ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTIONS:

Typically a typhoon

4 to 5 people

Roughly 2-4 days

Anywhere from 1-6 years

19,64 sqm

3,93 sqm

Mostly lowland, coastal sites, some inland. Prepare for uneven ground and the possibility of relocation

Construction of homes should technically simple enough for community to participate.

Use of familiar materials helped with self-building efforts.

Important to have spaces to discuss and host participatory workshops so communities can plan their own recovery.

Often a mix of traditional and modern materials.

Use of prefabricated elements as well as building on-site.

Flexibility and adaptability important qualities for reasons of a changing situation or personalisation of the homes.

Defining Vernacular Architecture

Research focus area: The Philippines

A Short History of the Filipino Vernacular DRAWINGS: Filipino Vernacular Elements

Paramount to the thesis is first defining what is meant by the term “vernacular architecture.” Etymologically, the word vernacular is derived from the Latin word “vernaculus,” which means native and is typically used in the field of linguistics. Paul Oliver, a distinguished architectural historian who specialised in vernacular architecture, loosely defines it as the “native science of building” (Oliver, 2006).

However, Oliver, like other scholars, notes that the usage of the term vernacular can be confusing, too broad, and even problematic. For one, vernacular architecture is sometimes used interchangeably with terms such as popular, traditional, rural, and indigenous. Less commonly used terms such as folk, savage, and primitive architecture can also carry negative connotations. In Rudofsky’s Preface to Architecture without Architects, an important book in the discourse of vernacular architecture published in 1964 following the MoMA exhibition of the same name, he states that some of these terms are generic labels for what he called “nonpedigreed architecture,” suggesting an interchangeable use (Rudofsky, 1964). However, in the past few decades, there has been a rise in scholarly work and discourse around the topic of vernacular architecture (Elizabeth Grant et al., 2017), and while the terms are still often used synonymously, slight distinctions do exist and are debated.

According to Allen Noble’s definitions, “traditional architecture” is built with the knowledge that has been passed down through generations. Under this term is “vernacular architecture,” which is “of the common people” and uses local traditions and materials in its design. It may be built by trained professionals, whereas buildings by untrained persons are referred to as “folk architecture” (Noble, 2007). The definition of indigenous architecture, on the other hand, is widely accepted as that of indigenous peoples who are defined as inhabiting or existing in a land from the earliest times or from before the arrival of colonists. Matunga warns against using labels such as traditional, folk, and primitive, as they can marginalise or frame native building as non-legitimate architecture (Matunga, 2018).

In contrast to Noble’s distinctions, Oliver’s definition of vernacular architecture includes all buildings made by “tribal,

“NONPEDIGREED” ARCHITECTURE = Interchangeable use with:

“VERNACULAR” “RURAL” “INDIGENOUS”

Definitions according to Bernard Rudofsky (1964)

TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURE

Uses knowledge from local traditions & materials

VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE

Can be by trained specialists

FOLK ARCHITECTURE

Untrained professionals

Definitions according to Allen Noble (2007)

POPULAR ARCHITECTURE

Buildings for popular which can be by trained professionals

VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE

By untrained specialists

TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURE

INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURE

FOLK ARCHITECTURE

folk, peasant, and popular societies where an architect or specialist designer is not employed.” He also stresses that vernacular architecture is much deeper than its aesthetic value and that the resulting built form is a manifestation of the processes and traditions that are specific to the culture and conditions of that place (Oliver, 2006).

To avoid confusion and the risk of bringing unwanted negative connotations, the thesis will mostly use Oliver’s definition of vernacular architecture: structures that are constructed by the local people and utilise local knowledge, traditions, and materials. By this definition, the term vernacular encompasses indigenous architecture and includes buildings produced by non-indigenous people that still meet the criteria of localised knowledge and materials.

Definitions according to Paul Oliver.

Figure 41

Author’s diagrams of different definitions for vernacular architecture.

Considering that only 2% of the world’s buildings are designed by architects (Rapoport, 2006), there is a deep wealth of knowledge to be gained from the ways people construct their own dwellings.

In Oliver’s chapters “Vernacular Know-How” and “Ethics and Vernacular Architecture,” he outlines some of the cultural issues to consider when studying the vernacular (Oliver, 2006). Oliver states that “an incipient romanticism pervades much enthusiasm for vernacular architecture.” Scholars studying the vernacular risk romanticising it too much and, consequently, overlooking its limitations.

Vernacular structures come with their own structural, climatic, and safety issues. They typically do not meet the standards of contemporary building. Clearly, there are cases where modern materials have an edge over traditional materials, and vernacular knowledge of construction techniques cannot always be applied to modern materials (Oliver, 1982).

This is where the role of the modern architect comes in—not as a passive admirer of traditional architecture, but one who, with knowledge of vernacular techniques and architectural training, can make balanced evaluations on how to translate the vernacular into the modern with their skillset. For Oliver, it is less about what vernacular architecture can teach architects and more of a call to action (Oliver, 2000).

Romanticising can lead to learning from the vernacular in an incorrect way. When studying the vernacular, the most common approach is to focus on its formal and aesthetic qualities. This approach generally does not work (Rapoport, 2006). The formal qualities are important because they provide a gateway to a deeper understanding of the cultural or climatic reasons behind those forms.

The thesis will aim to break down the formal qualities of Filipino vernacular architecture in order to understand which values and climatic conditions have resulted in such forms. To learn from the vernacular does not mean simply mimicking what already exists.

LEARNING BY COPYING LEARNING THROUGH ANALYSIS

VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE

VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE

DESIGN

CONCEPTS, MODELS, THEORIES

GENERALISATIONS, PRINCIPLES, MECHANISMS ETC.

DESIGN

Figure 42 Amos Rapoport’s model of learning from the vernacular

Architects have long looked to vernacular architecture for inspiration and innovative ways to solve even modern problems. For humanitarian architecture, the connection to the vernacular is the concept of sustainability. As discussed in Chapter 2 of the thesis, sustainability, in its different forms, is essential to successful post-disaster recovery. In these respects, vernacular architecture remains one of the most sustainable ways of building.

As Ozkan puts it: “...vernacular architecture is the highest form of sustainable building, as it not only uses the most accessible materials, but also employs the widest available technologies” (2006).

Vernacular architecture ticks the boxes on all fronts of sustainability. The fact that it is constructed from local materials, born from local customs and traditions, and built by the local people addresses the three aspects of cultural, environmental, and economic sustainability discussed in earlier chapters. It is this connection that forms the primary research question of the thesis:

What can architects learn from the vernacular in postdisaster architecture?