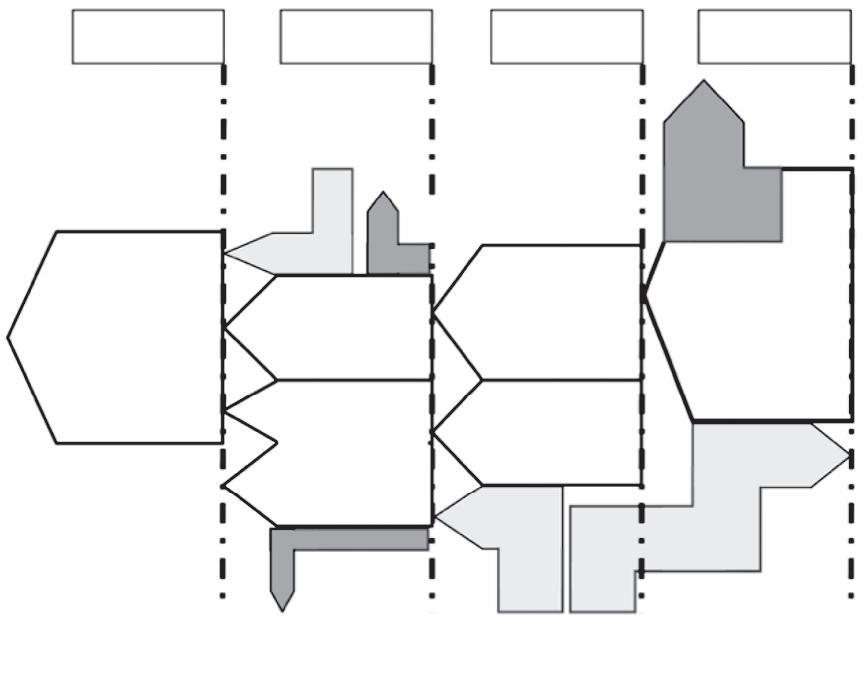

2 Meeting the needs of building occupants 2.1 Occupant-centred planning and building design Buildings are usually designed to meet the main needs of people who will live, work and perform their day-today activities in them. However, in future, buildings must also be designed to produce far lower GHG emissions than they do today. To trigger investments in new buildings and renovations with nearly zero GHG emissions, it makes sense to offer also improved levels of health, well-being and amenity to occupants. All members of building design teams, including architects, engineers, urban planners as well as the builders themselves, need to work together to deliver an occupant-focused approach, and to take the health, well-being and human comfort of future building occupants into account when making each design and construction decision. Such an inclusive approach is not new, but is being revived through the EU Bauhaus Initiative (EC 2021). An earlier example from the World Health Organization’s Healthy Cities Initiative, which dates from the early 1990s, is illustrated in Figure 1. This highlights why the potential impacts of climate change, the growing needs of ageing populations and the importance of minimising energy poverty (see section 2.5) should all be addressed from the earliest stages of the planning and design processes. 2.2 Health and well-being

In offices, uncomfortable thermal conditions or poor air quality have been shown to decrease cognitive performance and productivity (Lan et al. 2011; Satish et al. 2012; Wargocki and Wyon 2017). The following design features are particularly important for ensuring the health and well-being of building occupants. Adequate heating and cooling are essential for the health and well-being of building occupants. These must be provided using systems and controls that are designed to be easily understood by users as, unfortunately, innovations in buildings can be misused by occupants when they are not readily understood. This can lead to higher energy use and GHG emissions, as well as a poor indoor environment (Zhao and Carter 2020). The best way to avoid such problems is not to expect users to behave differently, but rather to design equipment controls so that their operation is intuitive because this will help to avoid their misuse (Naylor et al.

cultural and env mic, iro o n nm o en Living and working ec conditions io

vid di

ef a

o ct

So cia

Education

Unemployment

community ne d n t la ual lifestyl In

Work environment

Agriculture and food production

Water and sanitation

ks or w rs

Gen era l

Buildings with a poor indoor environment, including dampness or mould, darkness, noise or cold, are often linked to building-related health problems. Children living in homes with one of these four risk factors are 1.7 times more likely to report poor health. Children who are exposed to all four factors in their homes are, strikingly, 4.2 times more likely to report poor health (Gehrt et al. 2019).

s ion dit on lc ta

so c

Building occupants require a good indoor environment for their health and well-being. So designers of new buildings and of existing buildings that are to be renovated to nearly zero GHG emission performance standards must give special attention to those factors

that directly affect the quality, comfort and amenity provided by an indoor environment, including temperature, air quality, lighting, humidity and acoustics (IEQ 2020).

Health care services

Housing

Age, sex and constitutional factors

Figure 1 Key interrelationships in healthy cities (adapted from Dahlgren and Whitehead 1991).

EASAC

Decarbonisation of buildings | June 2021 | 7