An Ode to Lesbian Strawberry Farmers

E x p l o r i n g t h e

i n t e r s e c t i o n s between gender, s e x u a l i t y , a n d

a g r i c u l t u r e

Created by Environmentalists of Color Collective, FEM Newsmag, & the Westwood Food Co-op.

& Greet! We are so excited Strawberry Farmers” with een environmental and food hope it pushes you to s the complex inequities that nd inspires you to envision a more just future.

This quarter’s culinary aspect is the humble bean – an ode to the heartiest part of any meal. Beans are found in cuisines spanning the globe, they are a staple protein that requires very little land, water, and resources to grow, which explains why they’re enshrined in ubiquity. In a food system where meat production is typically a potent emitter of greenhouse gasses, beans serve as a delicious and accessible alternative. What’s even more magical is that their nodulating roots replenish the nitrogen in the soil they’re grown in, and have been used for millennia in crop rotation patterns to keep agricultural fields nice and fertile.

Environmentalists of Color Collective and the Westwood Food Co-op started Eat & Greet as a way to bring the community together through food and joy to allow attend the food justice movement. The Environmen Collective was brought together as a means o white-dominated conventions of the contemp justice movement by co-creating a healing sp prioritize the narratives, experiences, and nee environmentalists. The Westwood Food Co-o dedicated to making

g, and sustainable. Their main unity-supported agriculture)

This is FEM’s first UCLA’s intersectional feminist erates within an antiframework, viewing the food nscientious battle exists land and the exploitive powers that be: corporations, settlers, police, etc. When looking at a feminist perspective on the environment, you find there is liberation and healing in returning what we know about food, land, property, resources, etc. into the hands of its routinely marginalized caretakers.

We ask you to think about how you can help mend our broken food system, like buying locally grown and seasonal food within your means, limiting your consumption of red meat, and staying away from brands that use unethical labor practices. As you read this zine, take it home with you, and share it with your friends, family, and peers reflect on the food you eat, how it makes you feel, and where exactly you feel the connection between your food and the people and land who grew it.

Best,

Eat & Greet Introductions + Dishes

Hii, I’m Angel and I made Bhel! Bhel is a popular Indian street food a mix of crispy puffed rice, chopped onions, tomatoes, and various chutneys. My mom and I would always make Bhel when we were feeling lazy and wanted a delicious, crunchy snack. Nowadays I’m making it for large potlucks (like Eat & Greet) and when I’m missing a taste of home.

I’m Grace and I am making a veganized version of frijoles charros (sans chorizo), which is a traditional Mexican pinto bean stew named for the cowboys, or charros, who eat it. I am not Mexican, but I wanted to prepare a dish that pays homage to the country from which pinto beans (and many other phenomenal legumes!) were originally cultivated. Pintos have been grown in the plateaus of Northern Mexico for over 6000 years, and their value to cuisine & agriculture necessitates their appearance at the Eat & Greet.

Hi there! My name is Juliet and I made a citrus and poppyseed cake :) I chose to make this recipe because I wanted to highlight the tastiness of seasonal produce, and show how easy it is to incorporate them into dishes. As a fifth-generation family farmer, it is so important to me that people learn to love buying local & seasonal! Investing in small farms sustains family businesses and the rich culture of rural communities.

1

We sourced our citrus from Guzman Family Farms and Arnett Farms. Find them at the Westwood, Palisades, and Brentwood Farmers Markets (among others)!

Hi, I’m Isabelle and I made Chè Dậu Trắng, a popular dessert originating from central Việt Nam! It’s made from pandan, black-eyed peas, sticky rice, and a coconut milk base and enjoyed warm. My mom would always buy it from the market and since I’ve never been to Việt Nam, it’s a part of our culture that I can share with her here :)

Hello! I’m Bella Garcia, the current Editor-in-Chief of FEM Newsmagazine. With a few FEM staffers, we’ll be making Salvadorian pupusas. These are corn cakes made with masa harina, stuffed with beans and cheese, and served with curtido -- a lightly fermented cabbage relish -- and salsa roja. I was inspired to make pupusas after a night at a queer bar in Los Angeles: Honey’s. I hope to replicate the experience of finding just-the-right LA street food to end a beautiful time with beautiful friends.

2

Yolanda Chavez: A Biography of a Lesbian Strawberry Farmer

By Cali Perez Chavez FEM Newsmagazine

My tia Yoli is one of the women who has deeply impacted how I carry myself, especially as a queer woman. She migrated here from Mexico at the age of 24, still does not speak any English, and comes to every family event with her girl “friend.”

I tell everyone that they will never understand strawberries like I do because of the turmoil I feel when remembering the first eight years the Chavez family children spent in the fields of Santa Maria, alongside the Central Coast. My mother’s memories of the fields are not fond but my aunt nonetheless had plans to buy her own field so that she could extend the kindness the immigrant

population needed in our predominantly Hispanic community. Strawberry fields are not as cute and coquette as white people believe them to be. In them, you’ll find multiple generations of immigrant families working under a beaming sun they saw rise in the frigid morning. Farm work is back-breaking, and heatexhausting, mixed with empty stomachs. My aunt was formed through these struggles, and now that she’s fortunate enough to make their lives different, she does. She directly reverts her profits into improving the quality of life for her workers. Yoli bought a bus to transport workers between their homes and the

3

fields as cars form a barrier to getting to work. As they board the bus in the mornings, premade breakfast awaits them, all in the hopes that working can be accessible and pleasurable. She’s even opened up her home to many who live with her full time

Case Study: Monroe Queer Farmers

By Sydney Pearce Westwood Food Co-op

Monroe Queer Farmers is a collective of queer and transgender farmers that operate on a shared plot of land in Monroe, Maine on Penobscot territory. They not only share the land but “support the growth of each others’ farm businesses and to help train more queer and trans beginning farmers” through farmworker training events and network building. Their projects focus on equity and justice by “redistributing wealth, medicine, food, and seed.” At the heart of Monroe Queer Farmers lies a profound commitment to challenging the norms of agricultural spaces, fostering an environment where queer and transgender individuals can farm without fear of discrimination or marginalization.

Bo Dennis, the owner of the land, who began farming at age 18, formed the collective after struggling with having to hide

his identity as a gay and transgender man in rural farming spaces for safety reasons. Later on, he found community in Monroe, Maine where he ultimately bought land and decided to lease this land to queer and trans people for just $1. This initiative got its footing from Bo’s understanding of the immense resources needed to start a farm, and the obstacles to obtain those resources as marginalized individuals. In addition to making it more economically feasible for queer and trans individuals to begin farming, he also redistributes 10% of his sales along with a matched value of what he pays in taxes to Indigenous land organizing. He acknowledges that his privilege as a white male with financial backing has allowed him to launch this collective – yet he is dedicated to giving back. Bo's journey illustrates his transformation

5

from concealing his identity to establishing a supportive space for queer and transgender farmers, and a business that celebrates no longer having to hide. Bo stated that “a queering of business ownership in a way because it challenges this dominant, very capitalisticrooted thought process about running a business.” By creating a safe and affirming space for marginalized identities within the farming community, Bo and the collective are reshaping the narrative of farming – offering not only resources but also a sense of belonging and empowerment. Monroe Queer Farmers is paving the way for a future where all individuals, regardless of identity, can fully participate and thrive in farming communities – it is a pioneering force in advancing queer farming justice and community empowerment.

6

, '•,J, •1 . .

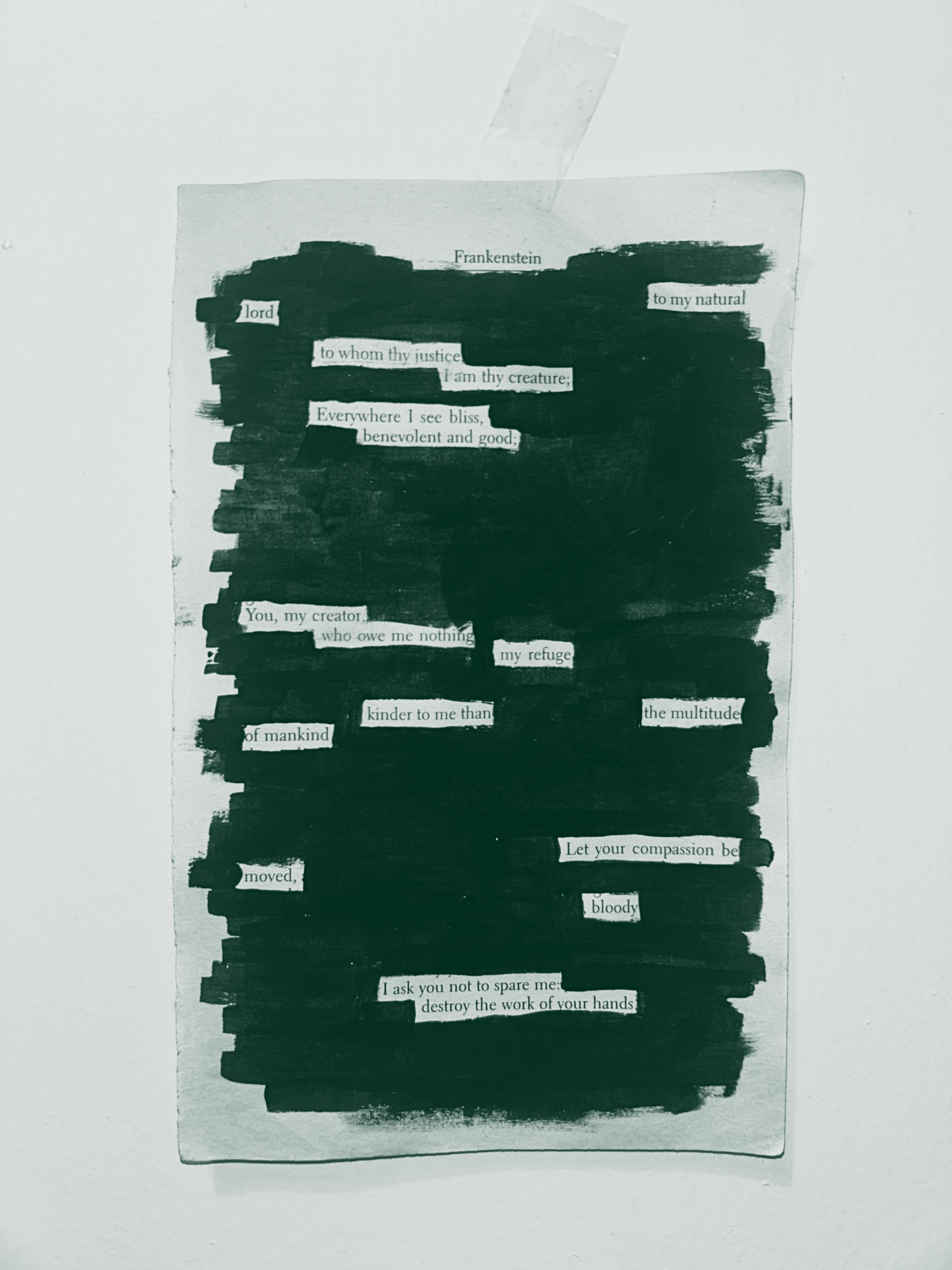

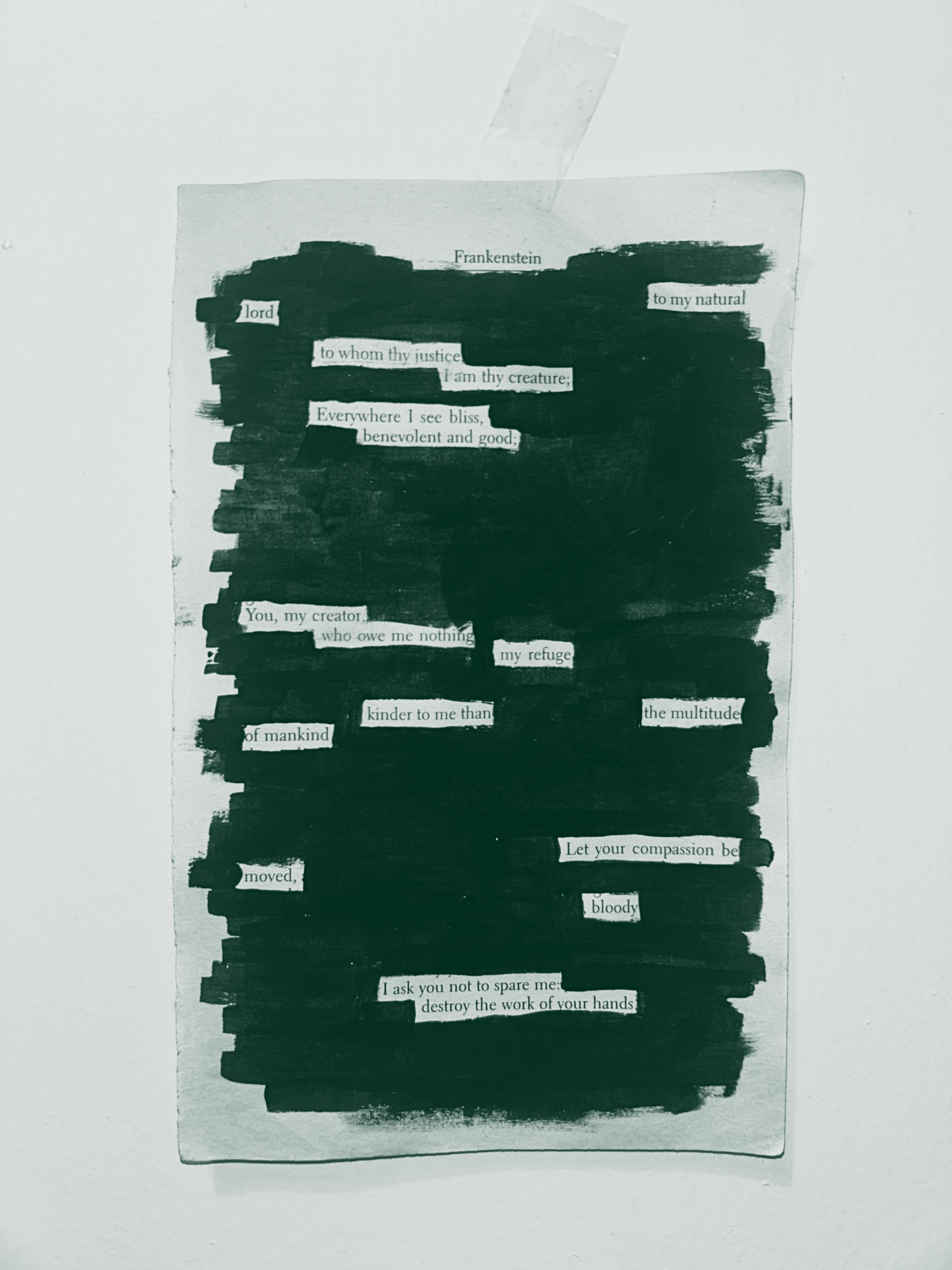

When the Earth Says She Needs You

By Bella Garcia

.

FEM Newsmagazine

Erasing Palestinians: The Uprooting of Palestinian Olive Trees

By Angel More Environmentalists of Color Collective

“The roots of the olive tree are from my soil and they are always fresh; Its lights are emitted from my heart and it is inspired; Until my creator filled my nerve, root and body; So, he got up while shaking its leaves due to maturity created within him.” - Fadwa Tuqan

Shajara el-Fakir,” (the pauper’s tree) and “Shajara Mubaraka,” (the holy tree) is what Palestinians call the olive tree: a tree that gives so much without needing much in return. From religious significance to olive oil to community bonding activities, the tree has brought value and importance to Palestinian lives for so many years. Even with the clear historical and present importance and reliance of olive trees, Israeli settlers and military forces have created obstacles for Palestinian farmers to grow the trees by making permits difficult to obtain, travel to their farmland, and directly uprooting over 800,000 olive trees in the past 56 years. With each tree destroyed, the olive tree has grown to become a symbol of

resistance against Israeli occupation, and nationhood, and simply a symbol of hope.

I conducted interviews with three Palestinians to understand the interviewees’ perceptions of olive tree grove destruction. Iris, Julie, and Roma (aliases) all encapsulate the message that the olive tree is seen as a symbol of resilience, strength, and connection to the land. It represents an intrinsic part of Palestinian identity, intertwined with their history, traditions, and sense of belonging. The destruction of olive trees is perceived as an intentional act aimed at erasing and displacing Palestinians from their ancestral land.

9

with them. The tree is as intrinsic to the land as Palestinians are. The interview then shifted to olive harvesting, an annual family tradition for Iris. The picking of olive trees is a cherished family outing and calls her family’s olive trees a “safe act of defiance.”

Iris talked about how Israelis often replace trees with non-native species that harm the ecosystem. They plant these trees over destroyed villages and croplands, using it as a deceptive gesture of replanting. Iris suggested that while the initial uprooting may not have been intentional, Israelis are now aware of the cultural importance of olive trees. She emphasized the severe repercussions that follow, including the destruction of livelihoods, increased poverty, forced emigration, or relocation to Israeli cities. When I asked Iris about how she was introduced to the uprooting of olive trees she said she knew about it “from the womb.” She grew up hearing about uprooting olive trees, Palestinians being murdered for protecting their olive trees, or border checkpoints barring Palestinians from visiting their farmland from news sources and her family. Just living in Jordan, where many people are Palestinian or closely know a Palestinian, it’s “something that you cannot wistfully ignore.”

10

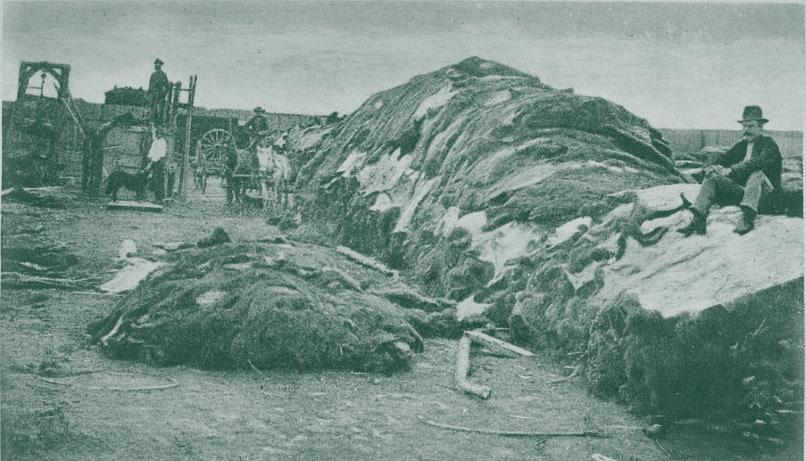

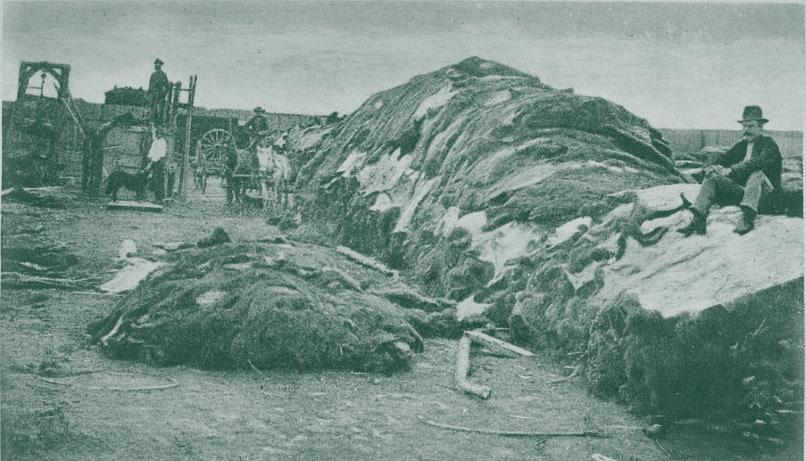

picture of a mountain of 15,000 bison skulls and three colonizers posing with them. This image drew parallels for Julie between the actions of American settlers towards Indigenous people and Israeli settlers towards Palestinians. In her view, the bison in America were an “extension of Indigenous people,” just as olive trees are an extension of the Palestinian people. American settlers killed bison, which Indigenous people respected and relied on for sustenance, as a threat and a display of power. Julie sees a similar motive behind the uprooting of olive trees by Israeli settlers an attempt to erase and displace Palestinians. Uprooting olive trees deprives Palestinians of sustenance, livelihoods, and their connection to the land. When Julie visits her family in Jordan they take her to the Jordan Valley where you can see Israel, including her grandparents’ village. She even was able to see the specific olive tree that her grandfather used to sit under: “he is not on that land anymore, but the tree still is there.”

Julie cites “colonial expansion” as the direct reason why Israeli settlers uproot olive trees. Palestinians are proud people, and when “you get rid of the source of pride,” olive trees, “that humiliates you and that degrades you [...] and makes it as if you never existed.” This can be seen in the European pine trees that Israelis are planting to replace the olive trees. The pine trees “require an extreme amount of resources to keep them going, so why do you want these resources and these forests, if it is not to cover up something that existed, and if not to replace.”

11

and that she believe[s] that Jesus himself used to climb [the Olive Mountain] sometimes.” Roma also refers to “the delicious olives and the healthy olive,” and “our Holy oil in our churches,” as evidence for olive tree importance.

Roma’s husband used to have an orange tree grove. They would sell the fruits from the grove to pay for water, and buy other supplies for the trees and land, and a man would look after the grove. However, this grove was bulldozed in March 2003 by Israeli settlers. After hearing this news, Roma and her daughter immediately visited the grove and saw “the beautiful trees laying on the ground,” and they “couldn't stop crying.” Roma’s neighbor’s grove was also bulldozed, and she has heard many stories about other groves being bulldozed “in the Gaza Strip and other parts of Palestine.”

To my question asking what were Israeli settlers’ motivations behind bulldozing her husband’s grove, Roma responds: “Clear hatred and force. […] They want us to leave our land to them. They came with great force over people who were simple peasants. They shot many people and killed many in such a vigorous way that many people left their villages and ran away to become refugees forever. They left everything they owned. Some left their babies in their hurry and fear and ran away with their lives.”

12

Settler Colonialism, Food, & the Womb

By Juliet Cushing Westwood Food Co-op

The gestating body has become a site of medical injustice due to settler colonialism and the destruction of indigenous foodways. During its campaign of genocide, the United States government sought to replace indigenous ecologies with settler ecologies via violent land theft, the destruction of farmland, slaughter of bison, systematized starvation on reservations, and the criminalization of traditional food harvesting. Tragedy cannot be tucked away in the annals of a history book because this food injustice persists today.

We see it manifest in the bodies of pregnant women where indigenous women are 1.5 to 2 times as likely to develop gestational diabetes compared to white women. This egregious health disparity exposes failings in the medical and social systems

of the United States, and also sheds light on the intersection of race and gender in food injustice. One window into this harm is land theft and its impact on food access. In her book, Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice, Dr. Rupa Marya retells the story of settler colonialism in the Northeast. The Seneca was one tribe affected by the 1838 Treaty of Buffalo Creek. While they had traditionally stewarded 338 square miles of land in Western New York, today, the sum of all Seneca Nation land is under 83 square miles. The deceit of the Ogden Land Company and policy of the U.S. government resulted in a 75% decrease in land access for a tribe that was fundamentally rooted in agriculture. Land theft was repeated on a nationwide scale with the Dawes Act of 1887 where the U.S. government effectively seized 90 million acres of indigenous land and transferred it to non-native ownership.

13

This act of food apartheid robbed tribes of their right to hunt, forage, and farm on an amount of land the size of Montana. We see the effects today as indigenous households are twice as likely to experience food insecurity compared to white households.

Food insecurity is a psychological stressor, inflammatory stressor, and is often compensated for by the consumption of affordable but nutrient-poor food; all of these factors increase an individual’s likelihood of developing gestational diabetes. For 7.8% of all pregnant women, hormonal fluctuations and glucose pathway dysfunction between mother and fetus result in the condition of gestational diabetes: high blood sugar during pregnancy.

Alarmingly, a CDC report from 2020 stated that the rate of gestational diabetes in indigenous women is 11.8%. Indigenous individuals with gestational diabetes experience a condition that lies at the intersection of their race and gender, where the condition is

modulated by food insecurity caused by colonial violence.

We cannot begin to remedy the disparities in gestational diabetes rates without addressing the food apartheid, land theft, and genocide to which it is connected. Food sovereignty is one place to start. The First Nations Development Institute defines it as “access to healthy foods that are culturally appropriate; the ability to produce food in a way that is sustainable; the ability to ensure that the food reaches all members of the community; provision of support for individuals providing the food; and policies in place that ensure control of the food systems and protect the resources needed to provide for the community.”

Some methods of achieving food sovereignty include legal access to land, legal hunting and fishing rights, grassroots food cooperatives, farmer training programs, and financial investment in indigenous-led initiatives.

14

Paper Summary: “Rice Cultivation in the History of Slavery” by

Review by Angel More Environmentalists of Color Collective

Judith Carney

“Rice Cultivation in the History of Slavery” by Judith Carney discusses the hidden role that enslaved Africans had in the planting of rice crops in plantations. Generally, slavery is taught with the perspective that enslaved Africans were just labor or “muscle.” With this perspective, enslaved Africans are portrayed as “less-than-human hands that uncomprehendingly carried out slaveholder directives.” The article “dispels long-held beliefs that Africans contributed little to the global table and added nothing more than muscle to the agricultural history of the Americas.”

The demand for domesticated West African rice grew as the slave trade grew; this rice was used to sustain the enslaved people, and presumably the enslavers. Slave ship captains would prefer to feed enslaved African people “traditional African crops” on board because their mortality rates would lower when they were given familiar food. The myth that Africans “did not domesticate crops,” and “contributed little to world agriculture,” is busted. The rice grain, Oryza glaberrima, was domesticated in West Africa’s Niger River 3,500 years ago. As the paper states “Africans adapted glaberrima to a variety of landscapes and developed specialized farming practices that advanced its diffusion elsewhere in the continent”

Rather than the preconceived notion that enslaved people were just used for labor, it is detailed how West Africans, and especially the women’s, expertise helped with rice cultivation. The paper explains that “nearly all the technologies employed on New World rice plantations bear African antecedents, from the irrigation systems that made fields productive, to the milling and winnowing of grain by African female labor wielding traditional African tools.”

15

A n a t o m y o f a D i s h A r t b y A n g e l M o r e E n v i r o n m e n t a l i s t o f C o l o r C o l l e c t i v e

When the Bison Left the Great Plains

By Grace Donohue Westwood Food Co-op

Around 200 years ago, before the American Midwest was planted with endless acres of genetically indistinguishable corn interrupted only by interstate highways and the occasional Meyers grocery store, the Great Plains were grazed on by enormous herds of bison. Across the world, each grassland ecosystem has its own particular ungulate whose microbiome and feeding patterns have coevolved with the native fauna on which they graze - in North America, it’s the humble buffalo (or Bison bison - a mammal so nice they named it twice?) Buffalo are a keystone species in the American prairie: their stomach bacteria convert cellulose-rich grasses into meat as they march & munch along, all the while aerating soil with their hooves and dispersing seeds for the regeneration of a healthy ecosystem. Their preference for native forbs and grasses allowed

for the flourishing of an incredibly biotically diverse collection of hundreds of plant species that dug their roots into the fertile soils across the middle of the country.

Prior to European colonization, these migrant ruminants were central to the way of life for Indigenous populations living on the Great Plains. Buffalo provided food, materials to build tools, hide for clothing, and a spiritual connection to the land itself. Lakota people have passed down the Legend of the White Buffalo Woman for 2000 years, in which a white buffalo visits in the Great Plains people in the form of a beautiful woman to connect them with the Great Spirit and bring the bountiful food of the buffalo hunt. The woman was first stumbled upon by two hunters, one of whom reached out to grasp her out of desire, but instead was reduced

17

to a pile of bones. Perhaps this reflects the fragility of the buffalo population and their existence on the prairie - they are not to be owned or exploited, but instead to be understood and respected as cohabitors of the prairie lands.

The 19th century saw a mass westward expansion by white Euro-American settlers, who brought with them colonialist ideals about the privatization of property and the exploitability of natural resources. With the Union Pacific Railroad literally laying the tracks for colonization and an army of gun-wielding troops with orders to shoot as many bison as they could, these settlers transformed the prairie landscape into farmland and hunted the Mighty Buffalo to near extinction. By the early 1880s, the unthinkably massive bison population, which numbered somewhere from 20 to 50 million at its peak, had been reduced to less than 1000 individuals. This mass slaughtering led to the demise of the Great Plains ecosystem, and

with it, the economic and cultural foundation of the people who lived there.

The extermination of bison was part of a larger effort by white settlers to systematically deprave the Native Americans who had lived and loved the land for generations. This process was accompanied by the establishment of reservations, the passing of laws to limit land ownership by Indigenous people, and the creation of “reeducation” schools to forcibly assimilate generations of people to the Euro-American culture that had plundered the Great Plains. Bison were replaced with a new ruminant, the cow, although few are grazing vast tracts of land in the way their predecessors were. Instead, cows are squeezed into concentrated

18

Image: More than 15,000 bison skulls (1892)

animal feeding operations (CAFOs) where they are fed genetically-modified corn grown in monocultures on the land that used to be populated by hundreds of grass species.

The killing of the buffalo transformed the landscape of America’s interior, and in the process, laid the groundwork for the industrialized food system we have today of commodity crops and big-name grocery stores. It also diminished the sovereignty that Indigenous Americans held over where and how they got their food, which

has only accelerated in years since. Restoration efforts that center the buffalo to rehabilitate the grassland ecosystem can restore what’s been taken from the land, and perhaps reflect a version of America’s food system where people were connected to the land and the food from which they were eating. The White Buffalo Woman and the herds she brought with her may have all but vanished from the Great Plains, but her message has never never rang more true.

Image: Rath & Wright's buffalo hide yard in Dodge City, Kansas, showing 40,000 buffalo hides.

Image: Rath & Wright's buffalo hide yard in Dodge City, Kansas, showing 40,000 buffalo hides.

19

They Tell Us To Leave Our Mark on The World. Art by Angel More Environmentalist of Color Collective

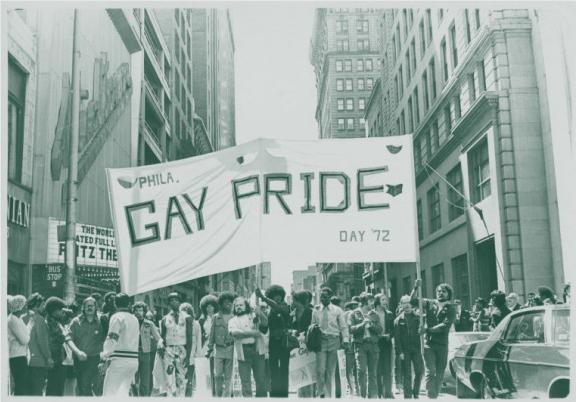

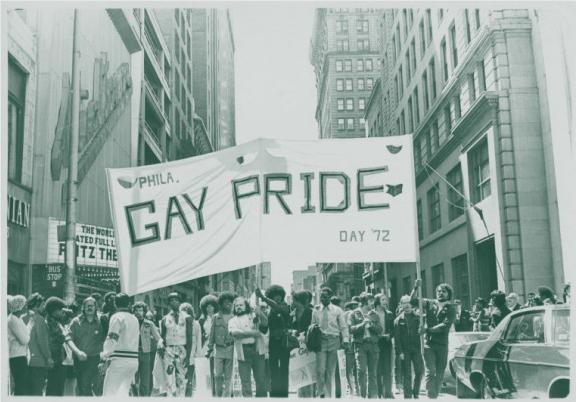

Paper Summary: “Queer and Present Danger” by Goldsmith, Raditz, and Méndez

Review by Juliet Cushing Westwood Food Co-op

disasters, droughts, wildfires, and the like. Queer people physically experience disproportionate rates of exposure due to the “historical

Our campus’ positioning next to the wealthiest neighborhood in 21

among youth who have been rejected or abandoned by their family. Global warming, rising temperatures, and heatwaves place unhoused people at high risk of heatstroke and other heat related illness. On the other end of the spectrum, hypothermia can occur at temperatures above 40ºF if an individual is unable to get dry, a devastating fact when thinking about the unprecedented rainstorms that have recently hit LA and the increasing number of hurricanes on the East Coast.

Queer individuals who are disproportionately policed–BIPOC individuals, transgender individuals, and queer women–experience environmental injustice while incarcerated. Incarcerated individuals are particularly vulnerable to heat related illness because many prisons are unventilated, made of heat-sinking materials, and do not offer adequate medical services.

healthcare due to income inequality as well as mistrust of medical providers and potentially exploitative hospital systems. A lifecourse analysis of the health of queer people reveals that LGBTQ+ individuals have higher rates of respiratory disease, cancer, HIV, and other chronic diseases. ‘Natural’ disasters caused by climate change exacerbate the symptoms of these illnesses and interrupt access to treatment: wildfire smoke and asthma as well as pharmacy closure during a hurricane and access to antiretroviral therapy are key examples.

Queer people are also less likely to have adequate access to

22

Image:PhotofromthefirstPhiladelphiaGayPrideParade(Philly,1972)

What are Food Deserts?

By Samantha Reavis FEM Newsmagazine

In the United States, there has long existed a wealth disparity along racial lines. In capitalist society, economic stature controls most, if not all aspects of one’s life - including what one eats. With supermarkets that offer fresh produce like Whole Foods and Erewhon being relegated to high income neighborhoods, many lowincome neighborhoods in this country can be considered what has been coined a “food desert. ”

Coined in the early 1990s by a resident of public housing in Western Scotland, a “food desert” refers to an area with limited access to fresh, healthy food at a price residents can afford. Typically found in lowincome, minority neighborhoods, food deserts contribute to a rise in childhood obesity because of the increasing concentration of fast food restaurants and convenience stores which offer a wide-range

of processed products. The concentration of supermarkets and fresh produce in middle and upper-class areas leaves the residents of low-income neighborhoods, who are more likely to have inadequate access to public transportation, without options for fresh and healthy food options.

The alternative is usually fast food restaurants or a convenience store which, instead of fresh proteins, fruits, and vegetables, typically carries imperishables: dried, processed foods which lack nutritional value and vitamins. Furthermore, low-income neighborhoods are generally home to more pharmacies than their richer counterparts. Pharmacies often contain unhealthy snack foods like candy, chips, and sugary beverages, which again, leads to a higher prevalence of nonnutritive food options in lowincome, typically minority

23

neighborhoods. Food deserts are of particular harm to working class families, who typically have to work nonstandard hours (e.g., rotating or evening shifts).

Many typical grocery stores close earlier than fast food or convenience stores, making the latter the only available shopping option for these families.

When the racial and socioeconomic stratification of this country segregates food, with healthy and fresh produce ‘belonging’ to the rich, and unhealthy, vitamin-lacking, processed foods delegated to the working class and people of color, not only are the physical health of this nation’s disenfranchised threatened, so are their mental, emotional, and academic well beings. There have been countless studies documenting the positive effects of nutritionally well-rounded diets on academic performance energy, happiness levels, anxiety levels, and sleep.

When the racial and socioeconomic stratification of this country segregates food, with healthy and fresh produce ‘belonging’ to the rich, and unhealthy, vitamin-lacking, processed foods delegated to the working class and people of color, not only are the physical health of this nation’s disenfranchised threatened, so are their mental, emotional, and academic well beings. There have been countless studies documenting the positive effects of nutritionally well-rounded diets on academic performance energy, happiness levels, anxiety levels, and sleep. Thus, when capitalism restricts the poor and working class (proletariat) from these foods, they harm these people’s entire wellbeing, reinforcing the oppression and marginalization of these groups necessary to sustain capitalism and keep the rich in power. Food deserts are just one example of how the subjugation of the working class and people of color in this country are overarching in their scope.

24

Water Management and Agriculture Through a Gendered Perspective

By Anna Vongjesda Westwood Food Co-op

Water is a highly debated and contentious topic. People’s relationship to water is shaped and influenced by socioeconomic, historical, and identity based factors. However, these experiences are not universally equitable; certain communities (notably people of color, low-income individuals, and women) have been historically absent from the academic literature, lacking effective representation of how water affects them (Glade and Ray 2022).

California is no stranger to droughts or water management debates, with a history of water scarcity spanning five decades. There is a need for new perspectives and approaches to long-standing issues, emphasizing the role of gender in water management. This

relationship is becoming increasingly recognized: for instance, The United Nations World Water Assessment Programme suggests that in many societies “women and men express different priorities for water use and conservation.” This highlights the need for the female perspective, often associated with the responsibility of domestic labor, to be voiced in water management discourse.

As with most aspects of life, water is gendered. It reflects the socially constructed notions of gender roles and responsibilities of a particular culture, especially within the household. Existing scholarship has highlighted the benefits of a gendered perspective of management as a whole; in particular sociocultural contexts, its found that that organizations with more

25

women in management had a heavier emphasis on humane orientation (fairness, caregiving, etc.) over power and status structures (Bullough 2022). When it comes to resource management, this can often translate to better understanding of collectivism and communitycentered work, seen through new approaches to existing agriculture practices (Sarah 2023). The farming industry has been hit hard by the drought impacts emphasizing the need to view resource management equitably, not only for direct water allocation but also for food justice.

The Radical Family Farms of Sonoma County is an example of how community-oriented approaches are being used to fill in gaps in the food system. Their regenerative agricultural practices are used to produce and promote culturally relevant crops to Asian heritage in the Bay Area, serving the community to increase food access to the Asian elderly community (AG+ Open Space 2002). As natural resource

debates continue, there is a strong need to continue paying attention to the role of gender in resource management. Gender, its associated labor roles, and its differing conceptions are all important in understanding how people experience natural resources and how to properly conserve them. As droughts persist in California’s future, it is imperative that we take note of the role of female conceptions of resource allocation to ensure a more equitable and fair future for all.

26

Women Farmers In India: A Need to Increase Ownership Of Agricultural Land

By Anya Desai Environmentalists of Color Collective

In rural India, 75% of women work full-time in the agriculture sector; however, women own anywhere from less than 5% to no higher than 14% of the land they cultivate in each of India’s 28 states (Oxfam India 2013).

Land is primarily transferred through inheritance, but religious-centric laws have resulted in women owning significantly less agricultural land than men. As men migrate out of the agricultural sector, women are left behind to tend to the land but are unable to access government benefits if they do not own land in their name. There is a clear need for women in India to get recognition for their work through ownership of land and better wages. As we develop laws and practices that are dedicated to helping women farmers thrive in the agricultural sphere, equity-focused laws must monitored and

implemented correctly so they don’t have adverse effects, like land ceiling laws.

Religious-Centric Inheritance Laws

In India, religious personal laws guide the inheritance process. Inheritance for Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains is governed by the Hindu Succession Act of 1956, which provides all daughters with rights to the father’s share of joint family property by birth and allows women to initiate a partition to joint property (Agarwal, Anthwal, and Mahesh 2021). Many states have statutes that supersede Muslim Sunni and Shia succession laws and prioritize male heirs for agricultural land, effectively preventing many Muslim women from inheriting agricultural land (Agarwal 1988). According to 27

the 2011 Census, together, these inheritance laws affect 96.9% of rural women across India and help explain why they own anywhere from less than 5% to no more than 14% of agricultural land in any given state (Agarwal 1988; Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner 2011).

An Increasingly Feminizing Sector

A 2013 study by Oxfam India found that 75% of rural women work full-time in the agricultural sector while only 59% of men do so (Oxfam India 2013). Consequently, while agriculture is the primary occupation for 62.8% of rural women, it is only the same for 43.6% of rural men (Oxfam India 2013). Additionally, many women work as unpaid cultivators on family farms while laborers on other farms typically receive at least 30% lower wages than male laborers (Oxfam India 2013).

Even though more women are working in the agricultural sector each year as men leave for

ther non-agricultural jobs in urban areas, many women do not own the land they work on.

Ambiguous Definition Of “Farmer”

The 2007 National Policy for Farmers defined “farmer” broadly to include anyone “actively engaged in the economic and/or livelihood activity of growing crops and producing other primary agricultural commodities” (Department of Agriculture and Cooperation 2007, p. 4). In official documents, the government avoids defining “farmer”. Instead, they imply that the term means landowners. Since the government tends to define “farmer” in terms of those who own property, many women are thus denied access to government credits; from help securing inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides; and from extension services that include trainings to use new technologies for agricultural practices (Rao 2006; Ministry of Agriculture, Farmers Welfare ).

28

Eat & Greet is a quarterly community-based potluck. Started by Environmentalists of Color Collective and Westwood Food Co-op in Spring 2023.

“An Ode to Lesbian Strawberry Farmers” and the Eat & Greet event were created, hosted, and shared on Gabrielino and Tongva Land. We acknowledge the Gabrielino/Tongva peoples as the traditional land caretakers of Tovaangar, the land upon which UCLA’s campus is located. We recognize the historic discrimination and violence inflicted upon Indigenous peoples in California and the Americas, including their forced removal from ancestral lands, and the deliberate and systematic destruction of their communities and culture. We honor Indigenous peoples past, present, and future here and around the world, and we wish to pay respect to local elders.

This zine was a collaboration between Environmentalists of Color Collective, FEM Newsmag, and Westwood Food Co-op, with funding provided by The Bruin Advocacy Grant and the Green Initiative Fund.

Layout and Design: Angel More and Bella Garcia

Writers: Cali Perez Chavez, Sydney Pearce, Bella Garcia, Angel More, Grace Donohue, Juliet Cushing, Samantha Reavis, Cali Perez Chavez, Samantha Reavis, Anna Vongjesda, and Anya Desai.

Image: Rath & Wright's buffalo hide yard in Dodge City, Kansas, showing 40,000 buffalo hides.

Image: Rath & Wright's buffalo hide yard in Dodge City, Kansas, showing 40,000 buffalo hides.