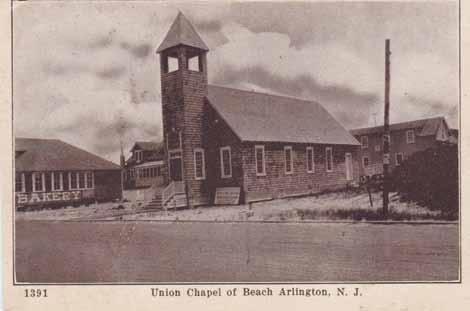

elcome back to beautiful Long Beach Island — 18 miles of history, memories, and this year — anniversaries. The Southern Ocean Chamber of Commerce is celebrating its 110th anniversary which also marks the 110th anniversary of the opening of the original Causeway bridge. Grace Calvary Church is celebrating its centennial all summer and Ship Bottom is coming up on its 100th year as well.

As we do every year, Denis and I drove west to visit our children and grandchildren. This past year, we only drove as far as Longmont, Colorado. Next year we hope to cover the whole east to west as we have done in the past — Atlantic to Pacific — with great stops at national parks, and natural wonders along the way.

Since receiving the Robert Fry Engle glass plates, it has occurred to us that many times, over the past three decades of driving across country, we have traveled the same roads and stopped at the same places Engle photographed. I marvel at Engle’s dedication and stamina. I can only imagine what it must have taken to get some of the breathtaking photos he took. Denis and I travel with a lot of gear, but nothing that even comes close to the photographic equipment Engle hauled up mountainsides through the wilderness. Thank goodness for cell phone cameras.

I am pleased to have a story in this issue about Jack’s De Luxe Diner. It is a unique part of LBI history that holds so many memories for a generation of LBI teens. Especially memorable is the local connection to the acapella group that often sang there. For a while, for many teens Jack’s seemed like the center of the universe.

For me, Jack’s evokes memories of my first car, a 1956-ish sun-bleached Renault Dauphine that I purchased from a man in Loveladies. At $50, the price was right; never mind that the starter was missing. I just needed a few people to push while I popped the clutch to get it started. Once my Renault was moving, it was a great car. No matter where I went, I turned it off as seldom as possible, especially if I was alone. Although, it often attracted help, especially at Jack’s. My youngest sister, Susie, called my car, “Push and Go.” More than any of us, she hated the thought of getting stuck somewhere.

Whenever the fire siren sounded, my sisters and I dashed off to the scene. I suppose you could say we were fire truck chasers. To this day, I still believe it was something we did out of concern. Although, my sister, Merry, says we were simply curious by nature, or perhaps bored. One of the chasings led us to a situation of our own when the siren went off one night after we were already in our PJs. Merry, Susie, and I jumped into my Renault Dauphine and went to find the fire. Of course, the car stopped running; we had to push and pop the clutch in our flannel PJs. Susie will never let me forget that night. Also, she did not want me to write this but an older sister’s prerogative always rules. Just ask any younger sibling.

Celebrating with friends and family on LBI is one of the best ways to make memories. As it is every year, one of our festivities is our chowder and chili cook-off. The winner again this year was Steve McGarry for his grandmother’s Rhode Island clear clam chowder. For our 2024 cook-off we are taking things to a whole new level with the addition of a special guest judge, Chef Andreas of Mensa Eats will be joining us. So, everyone is going to have to step up their game.

Lastly, we are honored to be the recipient of the Ocean County Cultural and Heritage Commission Salute Awards 2024 — Award of Special Merit for extraordinary achievements and contributions to the quality of life in Ocean County: for keeping history alive and promoting local artists, writers, poets, and photographers. I am grateful for my dedicated staff who joins me in thanking the talented writers, artists, poets and photographers, Islanders, vacationers, visitors, and contributors that help us fill the pages of Echoes. We are constantly humbled by those who so generously share their family history, entrust us with heirloom photographs, and share their love of LBI with us. It takes a village to publish Echoes of LBI Magazine. Thank you for being our village.

Celebrate everything. Keep history alive. Enjoy more sunsets.

Cheryl Kirby Publisher, Echoes of LBI Magazine

Echoes of LBI Magazine • Cheryl Kirby, Owner & Publisher • (609) 361-1668 • 406 Long Beach Blvd. • Ship Bottom, NJ • echoesoflbi.com

If you have an LBI story, photography, poetry, nostalgia, beach find or art you would like to share, tell us at echoesoflbi@gmail.com.

Advertisers: Readers collect Echoes of LBI – your ad has the unique potential to produce results for many years beyond the issue date.

Magazine Designer – Sara Caruso • Copy Editor – Susan Spicer-McGarry • Pre-press – Vickie VanDoren

Photographers – Lisa Atkins, Daniel Brede, Barbra Bongiardino, Sara Caruso, Mary De Sane, Kathy DeWitt, Dimitri Cugini, Cheryl Galdieri, Johnny Gofus, Joe Guastella, Nina Herbst, Mary Hoffman, Keith Holley, Diane Keeler, Denis Kirby, Holly Loihle, Marlena Marie Photography, Jeannette Michelson, Jim O'Connor, Maggie O'Neill, Anthony Pitale, Nancy Rokos, Gillian Rozicer, Dottie Pariot, Reilly Platten Sharp, Tyler Steinbrunn, Kathleen Stockman, Diane Stulga, Kelly Travis-Taylor, and Steven Wagner

Contributors – Lisa Atkins, Karen Bagnard, Matthew Bernstein, Pat Born, Jay Bower, Linda Bubar, Sara Caruso, John Chmura, Mary Davey, Nikoleta Dervisevic, Justine Dinardolim, Joyce Ecochard, Nancy Edwards, Cora June Einhorn, Brandon Foley, Michele Foulke, Carol Freas, Judy Gregg, Joe Guastella, Mary Ann Himmelsbach, Nancy Kelly Kunz, Kelly McElroy, Mary McBride Majkut, Pat Morgan, Maureen Newman, Maggie O'Neill, Edith Dalland Parker, Fran Pelham, Gillian Rozicer, Randy Rush, Reilly Platten Sharp, Ann Sheridan, Merry Simmons, Susan Spicer-McGarry, Diane Stulga, Teresa M. Tilton, and Brad Ziffer

Content photo – Nina Herbst • Cover photo – Sara Caruso, story on page 93

Echoes of LBI Magazine™ | Copyright ©2008-2024 Cheryl Kirby, Publisher and Owner | All Rights Reserved

The contents of Echoes of LBI Magazine are property of Cheryl Kirby, publisher, and are protected by copyright and other intellectual property laws. No portion of this publication can be reproduced, transmitted, or republished without the expressed permission of the publisher.

An acrylic interpretation of Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night by Nancy Edwards was awarded 1st Place in Pine Shores Art Association’s Fabulous Fakes Interpretive Division — 2023.

Vincent van Gogh painted the original in June 1889 in Provence, France. His impressive night sky was filled with color. His palette of blue, orange, yellow and pink blends depicted the depths of the night and the mystery of the universe. Making swirling, wavelike lines of color in the background, created rings of light surrounding the stars in the nighttime sky creating movement.

Nancy admired his use of color, texture, and movement with his paint. To add a twist, she replaced his cypress trees with Barnegat Lighthouse and the town in his painting with a dock. —Artwork and story by Nancy Edwards

Bonnie booked a B&B in Barnegat Light, Long Beach Island, on a recommendation from Trip Advisor. Three days off from waitressing in the city would be a welcome break and she loved exploring new beach towns. The ocean seemed to quell a vague unrest in her spirit.

The May weather was sunny and mild. After checking in, she headed to the beach. Long, windswept dunes overlooked the sea. Crashing waves sprayed white foam high into the air as she walked along the edge of the sand. It was a beach, much like many others she had explored. But for some reason, this one filled her with deep contentment. She was surprised at her reaction.

Late afternoon she changed into her favorite blue sundress and headed out to The Barnegat Light restaurant for dinner. It was a classic, old establishment, weathered and filled with historical memorabilia. As she entered, she noticed a waitress wanted sign posted near the front door.

She took a seat at the bar and looked around. A feeling of calm washed over her in a way she had never experienced. She ordered a glass of wine and briefly wondered if she should look into the help wanted.

After ordering dinner, Bonnie headed to the ladies’ room. An old painting hanging on the wall caught her attention. It was of a young woman lying on the sand holding a conch shell and wearing a vintage swim dress and hat in bright blue with stockings and swim slippers. In her own blue dress, Bonnie realized she looked like the woman’s twin.

She asked the bartender if he knew anything about the woman in the picture. “That painting is from the old Barnegat Light hotel. The woman was a waitress there and used to spend all her free time on the beach. A friend painted her in that pose, and the picture hung on the wall of the hotel until the Inn was torn down. Many of our pictures are from that building. We don’t know too much about her, but the locals call her Bonnie Blue due to her hat and swim dress. Come to think of it, you look a lot like her! You could be her ghost.”

The next morning Bonnie took a long walk on the beach at sunrise. Near the jetty she found an unbroken conch shell. As tradition dictates, she held the shell up to her ear. After the initial roar of the ocean, she heard the siren call as the shell whispered, “You are home.” —Written by Maggie O'Neill • Artwork by Carol Freas

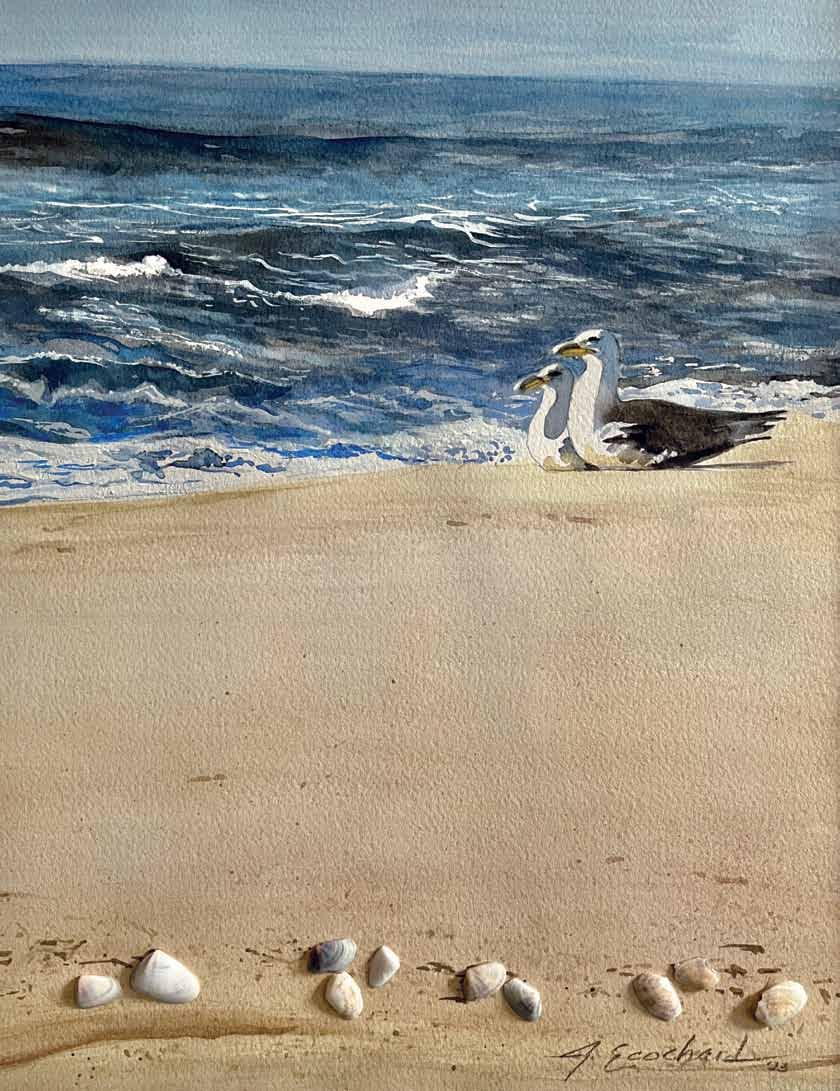

When Late Summer finds us along the island shore, some delightful warmer days arrive for us once more.

The beach is nearly empty, vacationers are few, dogs play fetch, children play catch beside a sea of blue.

Grab a hat and folding chair, sit down, enjoy the sun. Savor these last pleasant days before the winter comes.

—Poetry and artwork by Joyce Ecochard

At a special gathering last August, the spirit of renowned sculptor Boris Blai, the founder of the Long Beach Island Foundation of the Arts & Sciences, was rekindled as a group of those who knew him, studied with him, or whose lives were touched by him came together around special art and artifacts in his honor. Commemorating its 75th year, the Foundation under the auspices of Executive Director Daniella Kerner hosted the event organized by Echoes of LBI Magazine publisher Cheryl Kirby with the assistance of graphic designer Sara Caruso and editor/researcher Susan Spicer-McGarry. Featured speakers included Larry Oliphant, Reilly Platten Sharp, and Susan Spicer-McGarry with special guest Stuart Mark Feldman.

A believer in art as a form of expression and healing, Blai discovered Long Beach Island in 1927, saying later, “the Island is where I found my future.” That future included a decades-long teaching career as a founder of Temple University’s Tyler School of Art and therapeutic teaching with veterans. Early and continuing projects with other noted artists, such as August Rodin, R. Tait McKenzie, and Frank Lloyd Wright, created opportunities to leverage his increasing fame to do what Blai found he loved most — teaching. He believed that everyone can and should work

with their hands, no matter the specific artistic medium, and be exposed as young and often as possible to the idea of artistic expression. From the returning American GIs of World War II to elementary schools in Philadelphia and New York City, Blai — a veteran of the horrors of World War I trench warfare — knew first-hand how art could unlock the spirit and the soul of those disconnected from it. That belief also extended to himself, once a young student at the feet of Rodin in Paris, and later in life, a shattered man reeling from the loss of his teaching position with Temple, the loss of his wife, and the loss of his home at Harvey Cedars. At each crossroads in his life the creative outlet of sculpture allowed his mind, body, and spirit time and an outlet to process all his emotions and find his way forward.

Paying it forward could be described as Blai’s simplest legacy. It was a recurring theme at the core of the particular fond memories shared by those who attended the event.

Director Kerner enjoyed a lengthy career as a teacher and artist at the Tyler School of Arts, getting to see and speak with Blai at times around campus, before transitioning to work full-time with the Foundation he started.

Blai’s former student Stuart Mark Feldman credited his teacher with the lessons needed to become a noted sculptor in his own right and an educator at the Pennsylvania Acad-

emy of Fine Arts. Feldman’s close to life size bronze bust of Blai was on display.

Writer Reilly Platten Sharp is an arts graduate of Bucks County Community College, located at the former home of Stella Tyler who supported the School of Arts and hosted classes with Blai, and has been greatly influenced by the work of Island artists who honed their craft at the Foundation.

Larry Oliphant and his late grandfather, Joe Willy Oliphant, were personal friends of Blai, a multi-generational friendship that sprang from Blai’s admiration of Joe Willy’s talent as a builder in his construction of the Foundation’s structures. Oliphant displayed Blai’s larger than life bronze bust of his grandfather created to commemorate their friendship along with Blai’s favorite chair from his studio.

A collection of artifacts was on display as examples of how the echo of Blai’s spirit lives on. From busts by and of Blai to relics of his legendary art studios, all evoked the great man.

The highlight was a portrait created and donated by local artist Nancy Edwards in tribute of Blai that has been given a place of honor in the Manya wing along with other art and imagery documenting the history of the Foundation —Reilly Platten Sharp

Opposite page, top row, left to right: Rob; Jack with brother Liam and sister Ava Marie; Katherine, Anthony, and Victoria Middle row, left to right: Monica and Daniel; Everett; Heather Bottom row, left to right: Tyler; Cynthia; Catherine

This page, top row, left to right: Eve with her sisters, Harper, and Hadley, and friend Megan; Eva; Joey and Isabel Bottom row, left to right: Mike; Shelby; Guy

Opposite page, top row, left to right: Rob; Jack with brother Liam and sister Ava Marie; Katherine, Anthony, and Victoria Middle row, left to right: Monica and Daniel; Everett; Heather Bottom row, left to right: Tyler; Cynthia; Catherine

This page, top row, left to right: Eve with her sisters, Harper, and Hadley, and friend Megan; Eva; Joey and Isabel Bottom row, left to right: Mike; Shelby; Guy

Icaptured these shots on an early morning birding excursion for the New Jersey Audubon World Series of Birding on May 11th. Our crew, "No Time To Fly," led by mentor Jason Kelsey, had planned meticulously for weeks to make the most of our time. We kicked off our day at 12:30 a.m., rolling out from Jackson towards Island Beach State Park. Along the way, a pit stop in Barnegat treated us to some owl hoots, setting our day off just right. Arriving at the park around 4:30 a.m., we were met with the fresh dawn air and the serene sounds of Chuck-Wills-Widows in the distance. As I geared up to start birding, a subtle hue caught my eye. To our utter amazement, the aurora borealis made a surprise appearance, casting its colorful spectacle on the background of the Big Dipper. I wasted no time grabbing my phone to capture the moment, each snap etching the magic into memory. The site, a testament to nature’s unpredictability and beauty, left us all speechless. As the sun rose, we pressed deep into the maritime forest, eager for more discoveries. By nightfall the next evening, our efforts paid off, tallying up an impressive count of 129 species and landing us a respectable third place in our category. But it was not the accolades that stuck with us; it was the shared wonder of witnessing something extraordinary in our own backyard. Encountering the aurora in New Jersey was an unforgettable moment, a reminder of the wonders waiting to be discovered if we go out and enjoy nature. —Written and photographed by Tyler Steinbrunn, age 15, freshman at the Marine Academy of Technology and Environmental Science. Tyler is an amateur photographer and birder.

One love that is completely shared by two, Endless sunrises that I’ve watched with you, Sharing the beauty from each sunrise to sunset, I wouldn’t change a thing since the day that we met.

Hope, strength and serenity magically paints the sky, As a tear or two of gratitude falls slowly from our eye, Our plans and dreams are reflected upon at this time, Every beam like a new canvas in the sky as they shine.

You’ve given me so very much throughout our years, We’ve shared so much laughter and our share of tears,

The beach at sunrise is such a peaceful and serene place, A place to thank God for his abundant Amazing Grace!

Thanks for being my "Endless Love" each and everyday, May the light of the sun continue to guide us along our way

Each sunrise is a new promise as we gaze up into the sky,

To treasure all of our years of memories made here on LBI.

—Written and photographed by Diane Stulga. Dedicated to her husband Vic, inspired by their wedding song is "Endless Love."

T HE S AME W IND

On Long Beach Island the winter wind is like no other wind you may have experienced. I don’t mean the hurricane winds, or the nor’easter winds. I mean the everyday, in your face, take your breath away, hold on to the car door, chase the mail down the street, don’t even think of an umbrella in rain – kind of wind

It doesn’t come as a visitor, it’s a regular. Knows its way around; how to rock houses on pilings, put white-caps on the bay, and stand flags at attention. At night, if you’re prone to insomnia, when all should be quiet, you hear it whistle through the bedroom walls like a symphony flutist reaching for high C.

And when, just briefly, you think, ‘Not one more day’, crocus struggle through sandy soil, the island begins its move to summer mode and the wind, that chafing winter wind, becomes a soft, salt-air suitor, who lures beachcombers across a five-mile bridge, and welcomes them on hot summer nights disguised as a prodigal, gentle sea breeze.

—Written by Nancy Kelly Kunz

Photography by Lisa Atkins

COYOTES AND THE BEACH AT DARK

You sneak like keen sunset pelted lopers who know the shifting starlit dunes by scent. Something skittish pitches sand. Fervent beau has sheathed his poignant bow mid-note. Changed are they then, as waves oblique to wind.

Whelps fidget beneath the upturned boat you fixed one season on canvas but don’t yet know if it be blessing a bungalow wall or hiding something, a pitted panel, a seeping stain, which has with love trapped time while all around it changed.

—Written by John Chmura Photographyby

Keith Holley

HEAL NOT JUST ONE HEART

It is said, if you can heal the ache in one heart, Then you have not lived in vain.

If you can help one soul through hardship, Then meaning in your life is gained.

But one heart, it seems to me, Is not nearly sufficient; One forlorn soul, whoever it may be, Is still deficient.

The world’s supply of heartache Knows no bounds.

Hardship and sorrow can forever Be found.

Heal not just one heart, But many.

Help not just one soul, But any.

Help as many hearts in pain

As you are able to.

Then you shall not have lived in vain, For only one will not do.

—Randy RushSAILING

Leaving the harbor to sail the ocean blue

An exhilarating feeling of adventure ensues,

Listening as the rocks are sprayed with water, Breathing in the sea air and wind,

Drifting rhythmically riding the waves

Refreshing mist kisses our skin,

Slicing through the reflective water

Sunshine bounces off the mirror like glass,

Cruising along, this sea faring escape

Brings about a sense of heightened freedom,

Seagulls follow paving a path in the sky

While pods of dolphins entertain,

Navigating and floating, we return to shore

With renewed spirit having had this respite.

—Maureen Newman

How do you break open, A sea shell, Closed tightly, At the bottom of the endless ocean?

Turbulence and waves have only Made it stronger. Sitting there, among the rocks, You could easily mistake it for one. Yet, it carries a secret centuries old, A tale waiting to be told. Kindness, innocence and joy, a child-like heart

Beating to the sound of the waves. A pearl of emotion, sincerity and tenderness.

Its white glow

Helped the sea life communicate, In the darkest of nights. Its white glow

Became a light. Misunderstood, she didn’t quite fit in, On the contrary, She stood out from all the sea life, And as you can imagine, That brought great strife. All you could hear was Mermaid’s laughter, Envy growing deep. The pearl no longer had a home In the ocean, So she created her own, Deep within the armor of her shell She felt all alone.

—Written by Nikoleta Dervisevic Photography by Nina Herbst

Standing on the slippery green algae-entombed jetty where black flat slabs jigsawed somehow into place protect the edge.

Indiff’rent to the mighty strike of ceaseless surf they sit scrubbed clean, shining jet wet above the drink. Aquatic floral fluffs below the foam cling with fastened feet to wash their streaming locks. Waving in the drift afloat they transform dull, lifeless rocks on which they dance seductively the rhythms of the temptress tide.

Where the inlet yields; opening her waiting mouth to entreat the boisterous sea to enter to swell the shallows of the bordered bay with salt fresh hope.

Watching waters come and go sliding by inward/outward they flow; following the edge of flood, where wavelets touch their tips. They pass time and each other on their twice daily ride where fill and empty collide. What do they hide? One wonders, curious as Pandora who gave in to the urge, dared to open her guarded jar...

And evil emptied into the world! Yet hope remained inside to fill the void to be kept safe for all who seek its refuge, waiting to be needed.

On ancient sand, shell-cluttered toward the beach I saunter while wisdom sits cross-legged somewhere beyond steel morning clouds. The distant sky draws closer reaching for the earth. Her slender fingers curl about silent vapors on which the children of water are borne again into the heaving ocean’s heavenly reign above and gather, waiting in turn to rain back down into the wet womb of life as the cycle continues…

—Written and photographed by Joe Guastella

Her beautiful face

Smooth and glowing

Grinning and smiling

Laughing and growing

Has marks of wear and tear

Eyes deep like oceans

Sparkling on the surface

But dark and rocky below

Lips like shells

Smooth

Both only from waves crashing over and over

Cheeks

Burned by the sun

Forehead

Cut by the tide

She’s beautiful

In the way a lonely pirate is after finding gold

And realizing there’s no one to share it with

In the way a fisherman watches his friends go back home to their families

Then turning around and walking home alone with nothing but his cap in his hand

In the way a siren is

Wanting love but never being truly loved in return

Her beautiful face

Worn by the ocean

Like sea glass

Making her even more beautiful.

—Cora June Einhorn

It was a moderate winter while you were away. There was only one partial freeze of the bay. The dramatic pictures of Barnegat waters when frozen over will have to wait for another winter and no one complained when the temperatures did not dip too far below freezing. And while we were lucky with snow and ice last winter, the wind seemed endless, day after day. Mother Nature has a unique sense of humor.

The Ship Bottom Christmas Parade filled the borough with its usual holiday spirit. Echoes of LBI Magazine writer Diane Stulga and her husband, Victor, took second place for their jaunty yellow hot rod, adored with holiday wreaths and Disney and Peanuts characters in their festive attire.

Some stores closed; some new businesses opened. Some buildings were torn down; making way for new mixed-use buildings to go up. A skate park will have to wait. Pickle ball still reigns supreme.

The popularity of dining alfresco at Island restaurants continues to grow. Offshore wind turbines were front and center in the news throughout the off-season as was the Ship Bottom Elementary school.

That’s what you missed while you were gone. —Maggie O’Neill

Cold gray skies and freezing temperatures were the perfect backdrop for the warmth and sparkle of The Garden Club’s Holiday House Tour. Held on Thursday, December 7, 2023, more than 1200 visitors bundled up and stood in line to take in the holiday spectacle of five houses brilliantly decorated in the splendor of nature by Garden Club members.

A feast for the eyes and a full-year production, the tour brings to life the creativity and skill of The Garden Club. The event has been held annually since 196l when tickets were $2 and visitors were asked to not wear spiked heels. Now everyone wears soft slippers as they pad through the houses at their leisure.

Along the way, the Boutique at the Surf City firehouse did not require a ticket and was filled with arrangements of greens brought in from the gardens of club members. Alongside was a tour favorite of tasty homemade holiday cookies baked in members’ kitchens. Local vendors brought in luxurious cold weather gear, seashore art and handmade jewelry all arranged for gift shoppers.

The Holiday House Tour is one of two fundraisers that support The Garden Club’s amazing, Island-wide program of

community service. Included in this important work is the protection, preservation, and management of the natural environment of LBI, maintenance of three public gardens, garden therapy, and services for seniors, scholarships for local high school students, programs for young children, and contributions to like-minded organizations throughout the Island and mainland.

The Garden Club also brings the Outdoor Living, Garden Tour and Art Show to the Island in the summer, as the second part of its fundraising program. —Gillian Rozicer

The 57th holiday house tour is scheduled for December 12, 2024. Tickets will be available on the club's website thegardencluboflbi.com

LBI FLY features giant kites, including a full size whale, fairytale creatures, flying scuba divers, sports, and so much more! Events throughout the weekend include a Mayor’s Cup Kite Battle with all six LBI mayors, a night fly at Barnegat Lighthouse, a kite garden installation by local school children, indoor kite flying demonstrations, children’s kite making, kite buggy rides, and a special candy drop. This event is free to the public. Shuttles will be running throughout the weekend. For more information visit lbifly.com

It was a lackadaisical day on the beach and the man had lollygagged the afternoon away with a good book. No worries, no pressure, a divine dullsville. Then out of the corner of his shaded eye he saw a young whippersnapper surfer dude, board safelocked under his arm, as he picked his way across the afternoon sand - a bit of hot-hoppin’ in his step. But there was nothing namby-pamby about him. He was hustling. No time to kibitz with the guys with waves braking deep. He secured his ankle doohickey, then, lickety-split straight into the water to nail a priority spot. Eight strong strokes and an expeditious duck-dive got him there. Patiently he eyed the set, the break was on, he went for air, dropped, tucked into the crest, and cut all the way back to the toe-tips of an applauding hodgepodge of admirers wading in the kiddie-pool-warm water of the sandbar.

—Nancy Kelly Kunz

Irecently watched, with attendant goose bumps, a movie about the making of the song from which those lyrics were taken and wrote them down. Once I had done so, it occurred to me that the three-dotted ellipsis at the end of the last line leaves something unsaid for the reader, or listener to figure out. For me there was a challenge voiced in that chorus — an acknowledgement that it is our chance, our opportunity, to make a better day, “just you and me”— together! The statement rings as true today as it did thirtynine years ago.

In 1985, the entire world came together across TV screens, concert halls and outdoor gatherings to join in singing the song above. It was the anthem, the spark that lit the fire of compassion, raising awareness, spreading the message of suffering that was occurring in Africa. It may be naive to say that music has the power to change the world. However, there is just something about music that can reach into your soul and draw out the belief that you can be more than you are.

Those of you who were lucky enough to attend Compassion Cafe's presentation of GREASE at the Stafford Township Arts Center on May 1st know the feeling. The sounds of singing, laughter and collaboration which required every participant’s care and attention definitely plucked at the collective heartstrings of everyone there.

Compassion Cafe was introduced to the general public three years ago, in March 2021. We made our debut on the pages of Echoes of LBI Magazine in spring of 2022. This is our fourth issue, and it is still an absolute thrill to be included in this extraordinarily well-crafted publication. We offer thanks to publisher Cheryl Kirby and her truly dedicated corps of staff professionals and contributors as they continue to help spread the word of our growing community of caregivers and recipients. That community was born out of a desire to make a tiny piece of our complex, troubled world, our 18-mile-long fragile slice of shoreline and sand dunes, that confronts the mighty Atlantic, a little better. The founders and

organizers wrote the framework for their vision down on paper. They put out a call to families of special needs teens and adults, as well as to folks with a yearning to volunteer, to come aboard. They rolled up their sleeves and went to work. In our introductory article in Echoes, we spoke of Hope as being a fragile thing, yet something that we could count on to carry us through difficult times. We now revisit the Cafe coming up to its fourth season in operation.

Compassion Cafe 2024 — the need is still here! The intangible, uplifting feeling that Compassion Cafe provides to the community has not waned. Initially, there was COVID, and the Cafe offered a way out of isolation, of differences of opinion which caused rifts in families and friendships, a way out of cynicism and a focus for our energies and innate desire to come together as social creatures. It was a welcome change during a time of domestic political and social unrest and confrontation. We look to the Cafe to provide a space for self-esteem, acceptance, for the opportunity to work, to speak, to be heard, to be listened to.

We have friends and neighbors in our retirement community who get excited, even moved to tears to come to the Cafe for a cup of coffee, to hear a song or fill out a survey, to pick up a bag of homemade dog treats, t-shirt, ball cap, or bumper sticker; all of which are emblazoned with the coffee cup and heart logo that shows support for and inclusion in our growing family of believers.

Co-Founder Sue Sharkey’s words:

“As we enter into our 4th year, some might think the honeymoon is over.... we were a novelty when we opened- … But we're as strong as ever! I witness it every time the staff gets together…We (have a) wholehearted belief in…the possibilities for all the people in our employ. Which makes us so much more than a job… our donors (and the Sea Shell) continue to finance our crazy idea of overemployment and tell me they are better people because they have witnessed our little cafe with extraordinary customer service in action. We're here to stay- I’m working on our ten-year plan... who's with me?”

In 2023, Compassion Cafe was honored to be named Employer of the Year by the NJ Chapter of the National Association of People Supporting Employment First. It was an honor, to be sure, but it does not answer the question of why we do what we do. We believe that winning is not determined by score, but by participation. Yes, participation is the key. Participation equals winning. When I say “We,” I do not only mean our wonderful, growing staff of trained customer service representatives and their families. We are a community. We welcome new members. There is a place for everyone who wants to participate, to whatever extent their time and abilities will allow. —Written and photographed by Joe Guastella

Our staff has grown from about thirty employees in the first season to eighty as of September 2023. Our vital volunteer corps has grown right alongside as well. We need each other to move forward. We need customers, donors, interviewers, aides, mentors, nurses, teachers, folks with ideas, organizers, supporters, listeners more than talkers, drivers, buggy-luggers, smilers and, yes, even though we are full-up with teary-eyed onlookers, we need more of those who are moved to tears by what they witness at the Cafe. So, dear reader if you are curious, why not come on down to:

Compassion Cafe at the Oceanfront Sea Shell Resort 10 S. Atlantic Ave, Beach Haven Tuesday, May 14 through Thursday, September 12, 7am till 11am

Compassion Cafe seeks the integration of teens and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities through paid part-time summer employment in a small coffee shop environment with free hands-on training and ongoing support in an atmosphere of joy, community, love, and unconditional acceptance. By providing meaningful employment our employees gain independence, self-confidence, and work skills for future success. Compassion Cafe is a 501(c)(3) partnering with local businesses in a true, non-profit model.

Judy G R e GG and her husband, Joe, of Britton Falls, Indiana were staying at their LBI cottage when Judy decided to participate in the attempt to break the Guinness World Record for the Most People Blowing Conch Horn Simultaneously at Things A Drift in Ship Bottom during the annual LBI Sea Glass & Art Festival on October 5, 2019. “I don’t remember what song we played,” said Judy. “But I know we did it.” Indeed, she and the LBI community came together, succeeded, and still hold the Guinness World Record. Recently, Judy shared her story with Stroll Magazine. Not only did the magazine love her story, but she made it to the front cover.

Laura and Joe Hutchison started Hu TCH i SO n Fi B e RG l ASS P OO l S in 2003. Their son, Joe Jr. would go on to become partner and co-owner in 2017. Through hard work, integrity, and an unparalleled commitment to their customers — Hutchison Fiberglass Pools became and continues to be the premier fiberglass pool company of Ocean County.

Today, more than two decades later, Hutchison Fiberglass Pools is an award-winning family business. These days, Joe Jr. and Laura’s two daughters, Alyssa and Nicole, Laura’s father, Al Vero, and Olivia McKitterick, a close friend who is like a third daughter, are all part of the Hutchison’s in-office team.

From day one, maintaining their commitment to upholding the highest degree of integrity and professionalism has always been and continues to be the Hutchison family’s highest priority. When customers choose Hutchison Fiberglass Pools they become part of the family.

Under the direction of Joe Sr. and Nicole Hutchison the installation department is dedicated to turning the backyard of each customer into a personal oasis. Together with a well-trained crew and a relentless commitment to excellence they successfully make dreams of outdoor living come true.

On the service side of the company, Joe Jr. and Olivia have put together an outstanding service department. With an unsurpassed response time to any issue and an all-inclusive service program — Hutchison’s provides weekly service to more than 350 pools and opens and closes more than 500 pools annually.

The Hutchison family of Hutchison Fiberglass Pools is mindful of giving back to their community in many ways. They believe you can only be as good as the community you are a part of.

When it comes to transforming your outdoor space into a beautiful, functional, and well-maintained retreat, choosing the right contractor makes all the difference. Unlike some companies that specialize in just one aspect of a project, Je RS ey S HOR e PAve RS is a full-service company — specializing in hardscape and landscape design and installation, lighting, irrigation, and property maintenance. With this integrated approach your project flows smoothly from start to finish.

Founded in 2005 by Ocean County natives, Brian Sullivan and Alex Scherer, Jersey Shore Pavers is committed to delivering quality services, and excellent customer care. Brian and Alex work closely with each customer to determine how they want to use their outdoor space and help them explore ideas and options available to achieve those goals.

By offering a full range of services your project benefits from seamless collaboration, good communication, streamlined coordination and consistency in the high quality of workmanship that Jersey Shore Pavers brings to all projects. From design to installation then onto maintenance customers can rely on their expertise, commitment to quality and dedication to customer satisfaction.

Jersey Shore Pavers is a family and friend owned business. Founders Brian Sullivan and Alex Scherer are proud to work where they live and are raising their families. As role models for their children, they believe in the importance of giving back to their communities. Brian and Alex are active in their communities as members of volunteer services, youth sport coaching, and participation in local fund-raising events.

Michele Foulke wanted to get away to LBI. Her husband, Bob, had passed two years ago and September 18th would have been their thirtieth wedding anniversary.

Not wanting to be alone, Michele asked her cousin, Justine DiNardo Lim, to join her. Justine was grieving as well. There had been so much loss in the past few years; Michele’s father, Bobby, in 2019, her husband, Bob, in 2019, and then her Aunt Doris, Justines’s mother. The cousins are very close. They supported each other through it all.

Michele and her mom, Diane Vagianos, booked rooms for the weekend at Hotel LBI. Diane found an article about the Green Bench in an edition of Echoes of LBI Magazine that was in her room at Hotel LBI. She insisted that Michele and Justine find the bench to sit and reflect. The cousins agreed that this was something they would do together. However, the article did not list where the bench was located, only that it was at the top of the beach in Ship Bottom.

So, on September 18th Michele and Justine started at 28th Street and went to each beach entrance looking for the bench. When they took a break Justine called the magazine and left a message. They received a return call with the location along with a request that they take a photo of themselves at the bench for the magazine. And that is where the fun part of their journey began. With both of them sitting on the bench there was no one to take the photo. So, they propped up a cell phone and set the timer on the camera.

They tried a few times. But each time — just as it was ready to shoot the photo — the phone fell to the ground. Michele insisted it was her husband, Bob, causing the phone to fall. Now, instead of sadness, Michele and Justine could not stop laughing.

You see; reflection, grief, or whatever this bench brings you is peace and a moment in time where you are not alone; your loved ones are always around you. —Michele Foulke and Justine Dinardolim

April showers did, indeed, bring May flowers. The Youth Committee of The Garden Club of LBI met at the Surf City library on Wednesday, May 15th to create seasonal arrangements of flowers that attract pollinators.

Locally sourced euonymus greens formed the foundation in a cute tin flower container. Purple daisies, dainty asters, lavender stock, and the star among pollinators, the sunflower, were included. A ceramic bee topped each arrangement.

Each young designer was given the same greens and flowers to work with, yet each took home a unique creation. Packets of sunflower seeds and colorful UV protective sunglasses were given to the participants to encourage them to plant and tend their gardens with pollinator-loving plants all summer long.

The Garden Club’s Youth Committee chair is Jeannette Michelson of Barnegat Light. Members of The Garden Club who assisted were Pauline Gertzen and Sue Warren.

This was the final Youth Committee gathering for the current school year. Meetings will begin again in the fall of 2024. —Gillian Rozicer • Photography by Jeannette Michelson

The Ivanov Group is a select team of dedicated real estate professionals serving Bergen and Ocean Counties. Experienced luxury investment specialists, The Ivanov Group provides invaluable expertise and guidance from acquisition to execution and sale.

As the founder of The Ivanov Group at Keller Williams Realty, Dianna Ivanov specializes in investment properties in the luxury, new construction, and development markets. She is highly regarded for her talent in identifying exclusive investment opportunities, conducting project analysis, and implementing distinctive marketing strategies. Dianna collaborates closely with builders and developers to ensure projects reach profitable completion. Built on mutual trust these relationships allow her to bring the best professionals to her client’s projects.

Beyond real estate, The Ivanov Group is dedicated to bringing awareness to the underserved and making a difference within the community.

With a commitment to advancing the role of women in business and industry, Dianna hosts “Women: A Seat at the Table,” a series of events held at community venues designed to empower women through crucial discussions about business, personal finance, and personal growth.

Dianna’s commitment to her clients is illustrated poignantly by the dedicated team of diversely talented professionals she has assembled to form The Ivanov Group.

Buyer’s agent, Army veteran Leyla McGinn is dedicated to assisting fellow veterans in their goals for homeownership. As Director of

Keller Williams Military in The Ivanov Group, Leyla is committed to educating the veterans community about VA benefits through hosting Veterans Association Mastermind seminars and training.

Stafford Township residents, Marybeth Weidenhof and Keith Weidenhof have more than thirteen years of experience in commercial and residential real estate. Having raised her family here Marybeth has been active in her community for more than three decades through her involvement with The Special Olympics, assisting senior citizens and supporting the arts.

Samantha Cole is licensed in New Jersey and New York. With a background in luxury marketing and small business ownership, Samantha is a skilled negotiator and brings a unique perspective to showcasing her client’s properties. Dedicated to achieving the best results, Samantha builds a genuine connection with her clients, taking the time to understand their unique needs.

As head of the commercial division of The Ivanov Group, Rich Loniewski works with investors to identify profitable projects, guiding them through the challenging investment market. Rich’s background in the lending and investment industry and his experience and perspective are invaluable for even the most seasoned investor.

Committed to giving back, Rich provides mentorship and coaching for new investors.

We are members of the National Association of Home Builders, Women in Building Council, Professional Women in Building, National Association of Women in Construction, and Women in Residential and Commercial Construction. Also on the board of Family Promise of the Jersey Shore and Covenant House.

Echoes of LBI Magazine – Cheryl Kirby, 2024 Recipient of The Ocean County Cultural & Heritage Commission Special Award of Merit in recognition of extraordinary achievements and contributions to the quality of life in Ocean County through her magazine, Echoes of LBI. The commission honored Kirby for publishing Echoes of LBI to keep local history alive and to promote local artists, photographers, poets and authors, and for providing the magazine for free thereby making the heritage of LBI accessible to the broader public; and recognized the magazine as a reverberation of the people, places, and arts that have shaped LBI over the years that is dedicated to retelling the memories of those who have lived, vacationed, and love LBI as well as publishing the artwork of local artist and photographers, and poetry about LBI. To all our contributors who make this magazine possible, thank you! —Photography by Maggie O'Neill

BRAd ZiFFeR, a native of West Orange, New Jersey, fell in love with LBI as a teenager while summering in Surf City.

Now a successful singer, voice-actor, pianist, and producer, with his own record label, Starlux Records, Brad has his own recording studio where he records voice-overs, and produces, mixes, and masters music for himself and others. His love of oldies and Doo-Wop reaches far and wide. His cover of Bobby Rydell's hit, “Wildwood Days,” is currently available for streaming and digital download.

Brad recently relocated to Manahawkin with hopes of finding the ideal spot for his son to attend school and grow in a family-oriented, healthy environment within close proximity to the beach.

This October, Brad will be performing at the LBI Sea Glass & Art Festival at Things A Drift in Ship Bottom, New Jersey. For information on his upcoming performances, and to hear some of his music, follow him on Facebook, YouTube and Instagram @BradZifferProductions and bradziffer.com.

Brad loves God, the shore, being a dad, and being creative. He now lives where his heart has been calling him all along.

inGRedienTS

1 cup plain flour

1 cup softened butter

1/2 cup confectioner’s sugar

1/2 cup cornstarch

One teaspoon salt

One or two teaspoons natural vanilla extract

di R e CT i O n S

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. Bake 20 minutes. Combine the dry ingredients in a large bowl. Use a pastry cutter or fork to cut in the butter and vanilla and lightly bring the mixture together until it resembles breadcrumbs. Take care not to over mix. Tip out onto

Buttery, rich, with a melt-in-the-mouth texture, this shortbread is said to have been the favorite of the late Queen Elizabeth II when at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. Though fit for royalty, it is simple to make and calls for standard ingredients. Cornstarch is the key to this delicate shortbread that crumbles into buttery perfection with every bite.

a lightly floured surface and gently knead to form a dough. Press the dough into a parchment lined 10 x 10 glass baking dish. To form the classic shortbread shape, use a sharp knife to divide the dough down the center. Then cut each half into five equal rectangles.

Use a fork to prick the surface of the shortbread all over and bake for around 20 minutes until the shortbread is a light sandy color. Shortbread should not be browned. Once baked, remove from the oven and use a sharp knife to gently re-score the surface of the shortbread while it is still hot. This will allow the cooled shortbread to break apart more accurately. Gently remove the shortbread from the baking dish after it has cooled. When completely cooled, separate the shortbread and dip each section in melted ruby chocolate. Place on parchment paper until set. —From the kitchen of Susan Spicer-McGarry

Charles Ruby Chocolate available at Things A Drift in Ship Bottom, NJ

All I do the whole day thru, is dream of chocolate. Morning, noon, and nighttime, too, I dream of chocolate…Ruby chocolate: red-pink color, fruity bouquet, velvety, semi-sweet, exotic, and complex with delicate undertones of sun ripened strawberries, fresh sour notes and a fleeting malt finish. —Susan Spicer-McGarry

A gift of nature that surprises and delights with its exceptional natural red-pink color, perfect tension between cacao and berry fruitiness, and luscious smoothness, ruby chocolate is the most uncommon chocolate, born from the ruby cocoa beans that thrive in Brazil, Ecuador and the Ivory Coast. An entirely new chocolate experience without added color or flavoring. Discovered in 2004 by Belgian-Swiss cocoa company, Barry Callebaut and introduced in 2017 as the fourth natural chocolate, ruby chocolate is a new addition to the traditional dark, milk, and white chocolate varieties.

Perfect crab cakes should be brimming with quality crab meat. And for those purists who prefer their crab cakes without added fillers this receipt is all crab.

inGRedienTS

1/4 cup light mayonnaise

2 teaspoons dijon mustard

1 teaspoon horseradish

1 large egg

1 large egg yolk

1/4 cup Parmesan cheese

1 teaspoon onion powder

1 teaspoon garlic powder

1 tablespoon dried parsley

1/2 teaspoon Old Bay seasoning

12 ounces fresh jumbo lump crab meat

1 tablespoon melted butter

1 fresh lemon cut into wedges

diReCTiOnS

Wisk together the mayonnaise, horseradish, mustard, egg, and egg yolk. Add in the dry ingredients and blend well. Gently fold in the crab; taking care not to break up the lumps of meat. Divide the crab mixture into four portions. For appetizers, divide the mixture into six portions.

Shape into balls and place them on a baking sheet lined with parchment paper or an oven-proof silicone mat. Use the palm of your hand to slightly flatten each ball to form a cake. Brush or drizzle each crab cake with melted butter. Bake at 400° for 20 to 25 minutes or until golden brown. Plate and serve hot with a wedge of fresh lemon and the sauce of your choice. Serves four as an entrée or six as an appetizer. —From the kitchen of Mary Anne Himmelsbach

3 cups of cleaned, fresh bluefish

1/2 cup diced sweet onions

2 egg whites

2/3 cup of blue cheese

1/4 cup heavy cream

Sauté onions in coconut oil until translucent. Put bluefish in blender and set on chop for forty seconds. In medium to large mixing bowl, add all ingredients, and mixing well.

Form into patties, and cook for three to four minutes on each side, turning carefully. Garnish with salad greens and lemon.

Skates and rays are common in the waters of the Atlantic Ocean and along the shorelines of New Jersey. When not swimming these flat cartilaginous fish can be found buried in the sandy bottom waiting for their next meal or hiding from predators seeking to make a meal of them.

Rays and skates are oddly configured with mouths, nostrils, and gill slits on the underside of their bodies; eyes and breathing holes are on their upper side. Skates and rays are elasmobranchs; their skeletons are made from flexible strong cartilage rather than bone. Their flattened wing-like bodies allow them to glide with ease and great speed through the water.

Similar in appearance, skates and rays are frequently mistaken for one another. However, there are physical differences that easily distinguish them.

• Rays are generally larger than skates. Skates have a prominent nose-like structure known as a rostrum at the front of their flat body giving it an elongated triangular shape. Skates have a thick shorter tail with a dorsal fin at the tip.

• Rays are generally diamond shaped with distinct wing-like pectoral fins. Rays have longer whip-like tails with a caudal barb located at the base.

• Aside from their appearance, skates and rays reproduce differently. Skates are oviparous, meaning their young develop in egg sacks called mermaids purses while rays give birth to live fully formed young.

• Many species of skates live in cool waters, rays prefer warm water temperatures.

Clearnose Skate (Raja eglanteria) has an average length of thirtythree inches and a translucent snout. They are seen from late spring until early fall when water temperatures are between 50 and 70 degrees fahrenheit.

• Both skates and rays have modified placoid scales for crushing crustaceans, molluscs, and fish. Skates have small pointed teeth, while rays have dental plates with rows of small, flat teeth.

• Both skates and rays have an important role in the ecosystem of the Atlantic Ocean.

Some species of skate and ray commonly found in the waters of the new Jersey coast include:

little Skate (Leucoraja erinacea) are found mostly in estuarine habitats from Sandy Hook to the Delaware Bay. Mature adults are generally sixteen to twenty inches long.

Winter Skate (Leucoraja ocellata) one of the largest skates found in the coastal waters of New Jersey with an average size of thirty to forty inches in length. They are known to be most active between October and early June.

Cownose Ray (Rhinoptera bonasus) is the most common ray observed along the New Jersey coast from May to October and tends to migrate along the Atlantic coast to feed and give birth. They head south in the fall in large schools, sometimes numbering in the thousands. With a kite-shaped body and whip-like tail they are known to jump out of the water creating a loud smacking sound as they dive back in.

Bullnose Ray (Myliobatis freminvillii) has large broad pectoral fins with sharp points and a thin snout and grows to be twenty-four to twenty-eight inches across. Watercolors and story by Nancy Edwards

Best Overall Saturday: David Introini, uranium glass, NY

Best Overall Sunday: Isabel Mullooly, red dice, NJ

People's Choice Saturday: Doreen Rhoads-White, violin-shaped perfume bottle, LBI

People's Choice Sunday: Susan McCormack, amberina wine glass stem piece, NJ

Best Overall Fossil or Artifact: Chase K., fossil great white tooth, LBI

Guess the Glass: Nadine Gunchak, guessed 1234, actual total 1233

The old saying “one person's trash is another person's treasure” could not be truer for the glass collecting community, albeit antiques, sea glass, or both. One form of trash which has captivated the hearts of collectors was once seen as waste from the glass making process. Sometimes it can be found in large chunks, other times beautifully fashioned into whimsical collectibles. This fabulous treasure with a terrible name is slag glass.

WHAT'S in A WORd

The word slag does not have the best meaning in some situations. In the case of glass and iron manufacturing, it refers to the amalgam of chemicals and impurities that floated on the top of the molten material or got stuck to the sides of the furnace, and after the day was done, was scraped out and discarded. Slag is often confused for cullet which are large chunks of glass used by the glass factories to supplement their glass stock. Early cullet may have also included broken or imperfect pieces from a previous batch, as well as bottles purchased back from the public in an early version of recycling. These were then added to existing formulas and melted into new pieces. However, there are two types of glass slag: glass from the end of the day, and pieces that were purposely made by blending assorted colors of glass.

the glass batch. This created the trademark marbled effect seen in most slagware. As the popularity of these pieces grew, batches of glass were intentionally mixed with milk glass to create distinctive bands of color. This created extraordinary, swirled patterns that were as unique to each piece as fingerprints. Early colors were often purple with white swirl, but quickly included other colors such as amber, green, and blue. Today, these pieces are highly sought after by collectors.

American factories also began producing the wonderfully swirled glass. In 1881, cousins Harry Northwood and Thomas Dugan immigrated to Indiana, Pennsylvania from England. In 1902 they took over the Hobbs Bruckenier Glassworks in Wheeling, West Virginia and made their slagware called “mosaic glass.” Around the same year, Challinor, Taylor, and Company also started creating their brand of slag glass made by swirling two colored glass batches together. They quickly grew into one of the most prolific slagware producers in the United States. Other companies would soon follow, including L.G. Wright, Westmoreland, and perhaps most well-known, Fenton.

THe START OF SOMeTHinG BeAuTiFul

Slag glass became a medium used to create beautiful decorative glassware and household dishware. Glass makers usually referred to this kind of slag as malachite, variegated, or marbled glass. First created in northeast England in the 1850s and continuing through the 1890s, companies including Sowerby's Ellison Street Glassworks, Henry Greener's Wear Flint Glassworks, and George Davidson & Company, Ltd. made malachite glass by pulverizing iron slag from blast furnaces and mixing the silicate material into

FAMOuS MAKeRS

Unlike the aforementioned glass companies, The L.G. Wright Glass Company was not a glass manufacturer. Rather, Wright designed and patented several molds for pressed glass pieces. Many of his designs include nesting animals, cups, toothpick holders, ashtrays, and pitchers which have since become highly collectable. Wright also patented several covered dishes including the Atterbury duck, first made in the 1950s. He contracted companies, such as Westmoreland and Fenton, to produce the glassware for him using his molds.

The Westmoreland Specialty Company, founded in 1889 by brothers Charles H. and George R. West, originally made candy and mustard containers in clear and milk glass. Over the years the com-

pany adapted to the changing needs desires of society and added more colors to their manufacturing. Westmoreland began its run of marbled glass in 1972 with only two options, purple or green. Eventually this expanded to include amber also called butterscotch or caramel, cobalt blue, orange, and red marbled glass. Some of their molds would later be sold to Fenton.

Not only the most well-known name in glass making, Fenton was also known for their slag pieces. In 1905, Fenton started out as a glassware decorating company. Soon after they built their own factory in Williamstown, West Virginia and began making glassware. Building off the popularity of milk glass in the 1950s, they began producing works with beautiful slag swirls for other companies. In 1968, they reestablished their decorating department, and in the 1970s introduced exotic new colors including Burmese, Rosalene, and Favrene. It was at this time they started producing their own slag assortment and selling it through their catalogs. In 1981, they partnered with the Levay Distributing Company, who had previously contracted Westmoreland and Imperial, for limited edition glass pieces. Fenton’s ad for its run of slag glass read as follows:

and End of Day Glass, depending on the manufacturer. No two pieces of Marble Glass are alike, each reflecting the individuality of the glass craftsman and the inherent individuality of the glass itself.”

Fenton continued making slag pieces into the 1990s. No doubt its popularity was owed in part to how long it remained in the public eye. While most factories were bought out or burned down, Fenton prevailed. However, in 2007 the company announced that it would stop all glass production, and by July 2011, after one hundred and four years, closed its doors for good. The building was demolished and later turned into an elementary school. Today, their pieces are highly collectible, often bringing] high prices at auction. Even chunks of slag from their production runs are sought out by collectors as colorful reminders of the once thriving company. Other famous U.S. slag glass makers include Imperial, Boyd, Mosser, Summit, Degenhart, Akro Agate, and L.E. Smith.

HiSTORiCAl SiGniFiCAnCe

“Through the years, beginning with the first production of variegated colored glass around 1850, "Marble Glass" has had, and will always have, a magical appeal. The luscious shading and intermixing of vibrant colors has had several names over the years, including Slag Glass

When found on beaches, slag can also be an indicator of early glass making that a glass factory may have been located nearby. Most sea glass collectors are familiar with places like Seaham in the United Kingdom and Davenport, California, where glass factories from around the area dumped leftover glass frequently called “end of day” glass into the sea. However, these are not the only places

where slag pieces, often referred to as multis, can be found.

The not-so-secret history of New Jersey is currently washing up on our shoreline. For over two hundred and fifty years, New Jersey was a powerhouse in glassmaking starting in the 1700s with German immigrants who came to find new opportunities in a new land. One of these immigrants was Caspar Wistar. Originally settling in Philadelphia and working in a brass button factory, Wistar often made sales trips to New Jersey. On one trip to Alloway, New Jersey, he noticed the surrounding area of Salem County would be ideal for glassmaking.

Ever the entrepreneur, he set up his glass house in 1739. Though earlier glass houses existed in other parts of the country, they all failed within a few years of opening.

The Wistarburg Glass Works, also known as the United Glass Company, was the first successful glass house in the United States, even producing glass globes for Benjamin Franklin's electrical inventions. Wistar would hire other German immigrants to work in his factory, and with their skill, New Jersey was put on the map for glass making.

By the late 1800s, more than two hundred and twenty-five glass factories were operating around the state, with the majority being in southern New Jersey. The properties of New Jersey's sand, often referred to as “sugar” due to its high silica content, made it ideal for glass working because it did not require extra refinement. As such, glass houses sprang up around rivers and tidal marshes for easy access to the sand, and the waterways provided a good way to distribute their goods. While these companies did not specialize in the marbled version of slag glass, evidence of southern New Jersey's glass industry remains in the refuse they left behind.

As a creative way to use up the glass leftover at the end of the day glass blowers created whimsies such as elegant glass chains, delicate canes, smoking pipes, paperweights or “dumps,” doorstops, bottles,

and marbles; the variety is almost endless. These pieces were so coveted among the blowers, that they often found their whimsy had been stolen by their coworkers if they returned to work late the following day. Whimsies were either given as gifts or sold in stores connected to the glass factory. One of these whimsies, known as the schnapshund (liquor dog), was owned by the granddaughter of Caspar Wistar. According to Mary Mills, Director of Exhibitions & Collections at WheatonArts, “The glass dog has remained at Wistar’s wife’s ancestral home, Wyck Historic House, Garden, and Farm, in Germantown, Philadelphia for generations.” It is currently on loan to WheatonArts.

In 1888, Dr. Theodore Corson Wheaton founded the T. C. Wheaton Glass Factory to make his own bottles and vials for his pharmacy in Millville, New Jersey. From these humble beginnings, one of the largest glass makers in New Jersey was born. In the 1960s, his grandson, Frank H. Wheaton, Jr., was inspired by a visit to the Corning Museum of Glass in New York, which houses some of New Jersey's original glass pieces, to open WheatonArts. The goal was to bring much of New Jersey's glass history back to its home state and display it for everyone to see. Designed after an early 20th century glass town, Wheaton Village was opened to the public in 1970, with the museum following in 1973. Among the many art glass pieces made at Wheaton, perhaps the most well-known are their commemorative bottles. Some were designed after famous antique bottles while others were of their own making and represented important moments in history, such as the Apollo moon landing or presidential elections. They were sold on site at the Wheaton Village gift shop and are still popular among collectors today.

lOST evidenCe FOund

In many cases, chunks of slag and cullet are found in the areas where old glass factories once stood. Along rivers and at former landfills, slag pieces have been rediscovered. Along some parts of the Delaware

Maurice River, where the large majority of glass factories stood. The tragedy left fourteen dead, 2,500 residents homeless, and $3 million in damage, the equivalent of over $38 million today. Many of the factories, as well as the towns, could not afford to rebuild. The remains of the glass furnaces were discarded along the southern shores of New Jersey to act as seawalls. To this day, pieces of the slag from furnace bricks wash up on these beaches.

ClOSeR TO HOMe

Few Long Beach Islanders are aware that there was once a glass factory in Barnegat. Built in 1893 by Benjamin P. Chadwick, the Barnegat Druggist and Hollow-ware Company, or Barnegat Glass Factory for short, was the only glass house in Ocean County. It specialized in bottles and vials for pharmacies and would later expand as its shares were bought by new owners over the years. Unfortunately, it filed for bankruptcy in 1911, and the plant was sold to The Cox and Sons Company of Bridgeton, New Jersey. It closed officially in 1913. More tragedy struck in 1914 when a fire devastated the building. Abandoned, it was demolished around 1920. Slag and whimsies could be found around the site until apartments were built on the site in 2013.

Bay, the only remaining evidence of a once booming industry still guards the shoreline from erosion. While not as rounded as those of Seaham, the sea glass slag found in southern New Jersey can be multicolored, showing swirls of amber, greens, aqua, milk glass, deep violet, golden yellow, or cobalt. Unlike most examples given so far, this mix of colors was not intentional, but rather represents when one batch of glass was cooled and poured over another, effectively creating layers on the furnace walls. While still attached to the bricks, they look like crystal formations, leading some to mistake them as minerals. When a furnace got too choked with slag, it was discarded, much of which is found along the Delaware Bay. Other times it is found in large chunks of a single color, indicating that it was cullet, and thus never used.

Factories can shut down for a number of reasons, but these factors may have played a role in the demise of southern New Jersey’s glass industry. After World War II, many glassmakers struggled to keep up with a very changed market. New imports from overseas and new competitors including plastics were pushing American glass out. But this was not the only threat the coastal glass factories had to worry about, as natural disasters were a part of everyday life on the east coast. In November of 1950, New Jersey was hit by a devastating storm that caused a massive tidal surge. The flooding wiped out many towns, especially along the Delaware Bay and

The history of glass making is all around us, but it can be difficult to see. Written evidence of dumping slag into waterways has yet to be found because in those days companies did not keep records of trash disposal. However, in the past it was common for landfills and dumps to be located along bays and rivers; the same areas where glass factories were frequently located. Storms also washed out a lot of history, and with it, a lost story, only to be found again by avid beachcombers. The slag glass we find tells that story, whether a swirled piece of a decorative dish or a factory's end of the day leftovers, the history is out there, you merely have to find it. Sara Caruso

The C HAMB e R ed nAu T ilu S (Nautilus pompilus) has been a part of our oceans for 480 million years. It gets its name from the compartments that make up its shell. Within this shell is a siphon tube called a hyponome which controls the animal's buoyancy by regulating the air and water in the chambers. This air and water is then pumped out as a form of jet propulsion, allowing the nautilus to swim.

Like all members of the family Nautilidae, the chambered nautilus lives in the largest, most recently produced chamber of its shell. To create a new chamber, the cephlapod extracts calcium and carbonate ions from seawater, and combines them into calcium carbonate. As it grows the chambers become wider near the opening, or apeture.

Nautiluses are nocturnal and opportunistic hunters. Using their sharp beak and strong tentacles, they prey on crustaceans, fish, and also scavenge off deceased animals that drift to the bottom. They are currently listed as highly vulnerable due to low reproductive rates, slow growth to maturity, and overfishing.

The shell on the cover has been pearlized, meaning the natural surface has been polished to reveal the iridescent nacre, or mother of pearl, a common feature of shells found in the Pacific Ocean. Pouring from its apeture like a bountiful cornucopia is a collection of naturally worn Long Beach Island sea glass found by Merry Simmons over several years of beachcombing.

Turn off the news

Turn off your worries

Put aside your chore list

Just for awhile

For it is the time of year

That we take inventory

Of our true purpose

That which is greater than us

Contemplate

Yet nurture self

With compassionate love;

We all know that this life can be difficult at times

Read a book

Take a quiet walk

Say a prayer

Have a proper cup of tea and a scone

At winter solstice the sun stands still (sol sistere)

With earth at a 23.5 degree axial tilt

I am not smart;

I looked it up

Nevertheless, be like the sun.

Be still

It is true that this is the darkest time of year

Yet without this time of stillness

Without this time of quiet presence

We could not fully appreciate the upcoming light

Once rested and with soul nurtured

Once done reflecting on shedding

What no longer serves us

We are prepared to anticipate

New beginnings

New possibilities

New hopes and dreams

New sense of self

Turn off your news

Turn off your worries

Put your chore list aside

Just for awhile

For it is during this time of solstice

That we begin anew

With hopeful vision as in youth

We go within, and we find our light

—Mary McBride Majkut

Close your eyes and picture the scene. If you are old enough, you may even remember. It is the mid-1960s on a warm summer night. You and your friends are hanging outside Jack’s De Luxe Diner in Ship Bottom. Cars are cruising north and south along Long Beach Boulevard, and you are heading into the diner — a converted train car — for a burger and a shake.

From the street corner you hear four guys singing a cappella under the streetlight. Their harmonies make the hairs on your arms stand up as you stop and listen. It is like a scene out of a movie, and for the locals on Long Beach Island, it is a cultural phenomenon that is replicated from the streets of New York City to Philadelphia with a blend of those two metropolises creating a very unique version of this kind of folk music.

A cappella is the oldest form of musical expression which historians believe predates the invention of language itself. As we have evolved through the human epoch, music has always been a part of our experience, and a cappella has morphed and survived as a folk-art form.

Can you hear them? Can you see them snapping their fingers and lifting their faces

to the starlit sky as the tales of young love waft through the evening air? In this case, the quartet calls itself Eddie and the Soundmasters. The original group included Jimmy “Smitty” Smith, Tommy Enna, Charlie Enna, and Eddie Pine. Over the years, just as a cappella has evolved, so too had the makeup of the group. Rodney “Hooder” Hood soon joined as second tenor. Tommy, Eddie, and Charlie moved on. In late 1965 Dave Gagliardi and Kenny Smith joined Jimmy and Rodney and became known simply as The Soundmasters. Members continued to come and go as the years passed, with Jimmy Smith and Rodney Hood remaining constant. Eventually, baritone Steve Romeo, bass Gene Hacker and top tenor John “Beesh” Bishop would form the final version of The Soundmasters, with John joining in 1998, making the ensemble a quintet.

I recently had the opportunity to sit and chat with Rodney Hood and John Bishop at Rodney’s metal shop in West Creek. “Memories are the best thing we have left,” quipped Rodney, who worked during the day fabricating and installing metal roofs, while singing at night. Today he makes lamps, weathervanes, and decorative pieces from sheet metal in his shop with his son, Ryan, who has taken over the family busi-

ness. John still works in the music industry and sings in an oldies/Motown group called Joey D & Johnny B Band. Their love of the music they made and the camaraderie they formed became quite evident as they took turns reminiscing, and though Jimmy Smith was unavailable at the time, he did note, “It was a great time, at that time of my life. We enjoyed harmonizing and learning

new songs.” They seemed well aware of their contribution to the culture of Long Beach Island and the Jersey shore.

Tales were recounted of the many places they performed, both down the shore and in Philadelphia. The Lamppost in Philly, Fuddruckers, Calloways and Sleepy Hollow in Eagleswood and West Creek, Buckalew’s,

When we acquired a building in Ship Bottom, New Jersey for our new restaurant, Burger 25, we were immediately drawn to its unique architecture. The building revealed its rich history as Jack's De Luxe Diner through distinctive curved ceilings. Our research uncovered that it originally featured a train car diner brought from Philadelphia. Over the years, the building had undergone multiple superficial renovations. Determined to honor its heritage, we undertook a comprehensive renovation, stripping back the accumulated layers to reveal and preserve hidden treasures like curved glass windows and structural beams. In homage to its history and to cater to the summertime crowds on LBI, we incorporated a milkshake bar window into Burger 25, celebrating both the building's storied past and the local love for ice cream. The renovation not only restored the building but deepened our appreciation for its unique story and the opportunity to add to its legacy.

—Aidan Vetter

Joe Pop’s and many other LBI venues., cruise ships, and churches, were only a few of the many places they performed. The Soundmasters were in great demand, earning $500 a gig, though charity events often rounded out their itinerary.

The Soundmasters earned respect within the Doo-Wop and a cappella world. Danny and the Juniors, Pat Barrett and the Crew Cuts, The Street Corner 5, and Frankie and the Fashions were among the many acts that the Soundmasters hung with and performed alongside.

But in the very early days, The Soundmasters honed their craft on the street outside of Jack’s De Luxe Diner in Ship Bottom. Eventually,

the owner of the diner invited the boys to sing inside where they got a real taste of what was to come. The crowds loved the vocal group and business was hopping. Soon The Soundmasters branched out to other bars and restaurants on LBI where the demand for their talents grew throughout the area.

Today, Jack’s De Luxe Diner is Burger 25

The Vetter Family purchased the building and property from the owners of Surf Taco, and after some extensive remodeling, reopened as Burger 25 in June of 2023.

As the location at 1915 Long Beach Boulevard in Ship Bottom was undergoing remodeling, the Vetters discovered that behind the walls they were tearing down

was the old train car from the original structure, still intact and quite viable. New walls were put up with the old window frames left open. The curvature of the car's ceiling was also incorporated into the new design, and if you look hard, you can envision the atmosphere of that old train car with a modern look. It seems fitting that this nostalgic design remains as a reminder of the history of the locale, and as you sit and enjoy one of their well crafted burgers, along with a thick, delicious milk shake or root beer float, you may be able to hear the harmonious voices of a cappella out on the street corner, for this very spot was once the home of The Soundmasters. Randy Rush • Photography of the band courtesy of The Soundmasters Archive

Over fifty years ago, dedicated residents of Long Beach Island with a vision to establish a community hospital united. They diligently raised funds to ensure local access to quality health care, culminating in the opening of Hackensack Meridian Southern Ocean Medical Center, originally Southern Ocean County Hospital, in

1972. Today, philanthropy continues to be vital to Southern Ocean Medical Center, exemplified by the upcoming annual Signature Social hosted by the Southern Ocean Medical Center Foundation to raise funds for a significant surgical expansion to address the community’s growing health care needs.

The Southern Ocean Medical Center Foundation will hold its annual Signature Social at The Farm on Main, a new venue, in West Creek on Friday, July 26. Proceeds from this event will contribute to the estimated $31.4 million surgical expansion project, which will modernize the hospital’s surgical suite over a thirty-month period. The expansion includes enlarging six state-ofthe-art operating rooms to over 600 square feet to accommodate a range of procedures and extending the sterile processing department — a critical component of all surgical suites.

Over the past decade, amid substantial residential and commercial growth in Southern Ocean County, the hospital has expanded its services to accommodate the influx of full-time residents, particularly heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic. This project promises to significantly reduce patient wait times.

The upcoming expansion marks the first major upgrade for Southern Ocean Medical Center in twenty years, energizing the community to rally together once again, leveraging philanthropic efforts to advance the founders’ vision.