PROCEEDINGS University of Dayton Honors Program 2022 Berry Summer Thesis Institute

University of Dayton Honors Program

Publication Alumni Hall 124-125

300 College Park Drive Dayton, Ohio 45469-0311

937.229.4615

Copy Editor: Sam Dorf, Ph.D.

Design and Production Manager: Gina Lloyd

Student Staff: Tara McLoughlin, Editing and Layout

Copyright 2023 University of Dayton Honors Program. All rights reserved.

Reproduction or translation of any part of this work beyond that permitted by the United States Copyright Act without the permission of the copyright owner is unlawful. The copyright of each article is held by the author. Requests for permission or further information should be addressed to the University of Dayton Honors Program.

Arts and Humanities

Musical Expressions and Symbolic Forms

By Jacob Biesecker-Mast

Lovecraft, the Uncanny, and The Sublime: A Psychoanalytic Critique of H.P. Lovecraft's Fiction

By Jules Carr-Chellman

Critical Review of Literature Surrounding 'Cultish' Evangelical Pastor Mark Driscoll

By Phillip Cicero

Music Therapy Treatment Considerations for Adolescents with Attachment Challenges

By Jaylee Sowders

The Snuffed Critique of Modernity: Adapting Brideshead Revisited for the TwentyFirst Century

By Caitlin G. Spicer

Business

Where Do Female Athletes Get Their Role Models? Exploring Women's Basketball in the U.S from Inception to NIL

By Tierra Freeman

Health and Sport Science

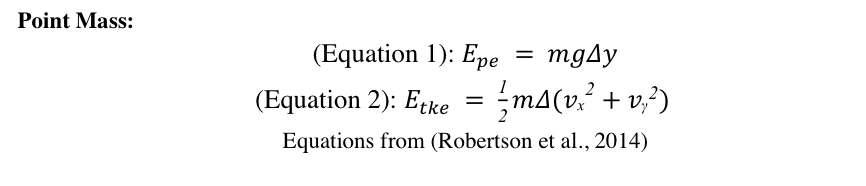

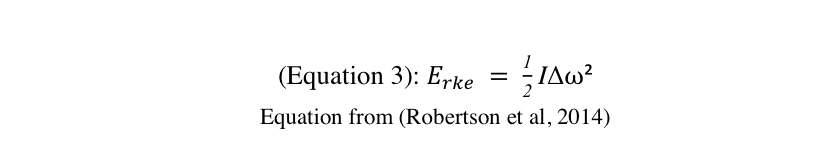

Overview of Cardiovascular Benefits and Mechanical Demands of the Kettlebell Swing Exercise: Implications for Work Economy

By Daniel E. Vencel

Life and Physical Sciences

Identifying the Effects of Low Temperatures and Propionate on L. monocytogenes Growth and Pathogenesis: A Review

By Lizzy Herr

Determining the Effects of Propionate on Listeria Monocytogenes Susceptibility to Lysozome Degradation

By Jeanne Paula E. Sering

Anti-Predation Behavior in Response to Conspecific Visual, Olfactory, and Damage Cues in the Three-Spined Stickleback

By Claire VanMeter

TABLE OF CONTENTS

5 9 14 20 42

49 62 71 77 82

ARTS AND HUMANITIES

Berry Summer Thesis Institute

Musical Expression and Symbolic Forms

Jacob D. Biesecker-Mast1,2,3

University of Dayton

300 College Park, Dayton, OH 45469

1. Department of Philosophy

2. Department of Music

3. Berry Summer Thesis Institute

4. University Honors Program

Thesis Mentor: Neil Florek, M.A.

Department of Philosophy

Abstract:

Frequently the idea of expression comes up when people talk about music’s value in human culture. However, expression is often ill-defined and can be found to be used many ways. Some argue that music is expressive of the creator’s emotions, something like an unrestrained outpouring of emotions as musical form. Some argue that music instead expresses the creator’s knowledge about emotions, rather than the emotions themselves. Others argue music is not expressive at all, but instead is beautiful by virtue of its well-formed nature. This particular perspective, musical formalism, often looks at what is called “absolute music”, or music without any other kind of media like lyrics, and argues that the form of the music, with all its interesting play between various melodies, counter melodies, and chord structure, is that which gives it value rather than any kind of expressive capabilities. Susanne Langer is a scholar who has written much on the philosophy of art and makes compelling arguments for the expressive nature of art, and thus departs from formalism distinctly. Many of her theories treat art as a sort of language that expresses through meaningmaking symbols. This summer I am doing preliminary work, using many of Langer’s theories as a base, on investigating this question: based on the particular syntactic and semantic structure of music, as distinct from other methods of constructing and communicating meaning, what kinds of meaning is music ideal for expressing? In order to answer this question, I am reading various texts by philosophers of music including Susanne Langer, but also Nelson Goodman and Peter Kivy. While Susanne Langer presents a quite relevant and useful broad theory, which argues music allows the expression of the emotional inner-life of human beings, to answer the question, there seem to be some weaknesses in her framework that might be remedied through the introduction of ideas from these other authors. For example, Langer postulates that symbols in music, as distinct from discursive language, do not necessarily refer to an object to make meaning, but instead present concepts as they are through constructing analogous logical relationships. This argument is difficult to make sense of as it would seem that even in this sense, the symbol is referring to the concept in question. If the symbol does not refer to an object, then the symbol is all that is needed to comprehend the concept. If this is the case then how are the symbol and concept distinct? In this case, Goodman offers up the concept of exemplification, in which the symbol exemplifies the concept in question, in addition to presenting it. Ultimately, I hope to argue that the value of music lies, at least in great part, in its capability to not only express the emotional inner-life of human beings, but also that in this act of expression, it does important work conceptualizing and constructing understanding about the world we live in and our experience of that world.

5

In her book, Philosophy in a New Key, Susanne Langer makes the case that music plays an integral role in shaping one’s understanding of the world. This is because, for Langer, musical works are not simply beautiful creations that may bring pleasure to the subject, but are symbolic forms that are vital to the process of conceptualization. Essentially, she argues music helps individuals to create concepts that help them understand the world in particular ways. One of Langer’s main points is that music is what she calls a presentational form, or a form that simply presents concepts to the subject. However, there may be some weaknesses in this argument, including her vague explanation on both the limits of discursive form and the advantages of presentational form. In light of these weaknesses, Nelson Goodman’s concept of exemplification might aid Langer’s theory by postulating a different approach to symbolism in the process of conceptualization.

One key distinction Langer makes is between signs and symbols. Langer argues that signs refer to something about the presence of an object, usually with regards to an action that should be taken in response. A good example of this is a train signal one might find at the intersection between a road and a railway. A train signal is useful because it refers to the eminent presence of an object: the train. Because of this, the signal provides useful information to the subject that can then be used to inform subsequent decisions, such as stopping before the crossing. A symbol, on the other hand, refers to a concept about the object, not just the object’s presence. Essentially, words are representative of the general concept, but can also be used to refer to the specific object as well. One very common example of this is words. The word “train” does not always inform the subject about the presence of a train. Seeing the word “train” on this page should not cause the reader to look around their reading area for a train. Instead, this word references one’s concept of trains: where they are usually found, what they do, how they function, and any number of other related ideas to the object. As Langer explains: “Most of our words are not signs in the sense of signals. They are used to talk about things, not to direct our eyes and ears and noses toward them… they take the place of things that we have perceived in the past, or even things that we can merely imagine…” (Langer 31). It is not that signals are not important, it is just that they serve a different purpose.

At this point, Langer also makes a clear distinction between connotation and denotation for symbols. This is because saying that symbols refer to a concept and a sign to an object is not a complete picture. First of all, it is important to understand that, according to Langer, signs do not just refer to objects, but specifically something about the presence of them. Even a sign pointing to something is referring to the presence of that object. Again, a symbol directly refers to a concept, but

this concept also refers to many objects, the most important one being that which the concept is about. Thus, a symbol can refer to an object through the concept. This is where the terms connotation and denotation come in; Langer explains: “Denotation is, then, the complex relationship which a name has to an object which bears it… The connotation of a word is the conception it conveys” (Langer 64). The relationship between a symbol and a concept Langer calls connotation, while the relationship between a symbol and the object through the concept is called denotation.

This connection between symbolism and conceptualization is an important one for Langer’s argument. If music is symbolic, then it means that music must relate to the subject’s conceptualization of the world. However, Langer does not stop there. So far, all that has been shown is that symbols refer to concepts, not that concepts actually shape the conceptualization process beyond the simple act of dividing up the world, that this is a bag and not a tree for example. For Langer, these symbols actually have some essential quality that necessarily relates them to their concept. Langer argues that symbols and concepts are related by sharing logically analogous forms (Langer 82). In other words, symbols refer to specific concepts because the two both possess some congruent logical form that is important. Take for example the pairing of a mercator projection and the earth itself. While these items are very different, most would easily make the connection between the two. Even though the earth is made of stone, metal, water and organic matter

International

6

while the map might be paper or even digital; even though the map is flat while the earth is a sphere; even though the earth is thousands of miles in diameter while a map might only be several inches; one still makes the connection that the map symbolizes the earth. Langer would argue that this is because the map and one’s concept of the earth share the logical relationships present in the geographic arrangement of features like continents, countries, oceans, and many other features depending on the specific map. That Europe is north of Africa and the two poles are opposite each other is preserved, and makes the map a useful symbol. To use the specific terms, the map connotes the various geographical concepts, and it denotes the earth itself. The idea that symbols are linked to their concepts and objects via logically analogous form is integral to Langer’s argument.

This step is important because it entails that the structure of the symbols themselves is important in the process of conceptualization. Not only is the act of using symbols important for shaping the way one conceptualizes the world, but the nuances of the symbols themselves affect the structures of the concepts. Langer argues there are two main categories of symbols. The first category is discursive symbols, or symbols that lend themselves to discourse. The most prominent example is language. Language consists of sentences that are made up of words, and can be combined in various ways. Some of the key characteristics of discursive form are that sentences are structured linearly and thus must be read one piece at a time, and that connotations in discursive form are general- they refer to concept that often includes many ideas (Langer 97). Additionally, discursive form relies on common understandings of syntax and word-meanings for individuals to be able to derive connotations and denotations from discourse. Often discursive form is taken for granted and some might argue that in order for something to be thinkable and therefore cognitive, it must be able to be articulated in discursive form. However, Langer argues there is another category of symbols that she calls presentational form. Presentational symbols simply present the concept for the subject’s observation and thought, rather than encoding it in words or sentences: “the meanings of all other symbolic elements that compose a larger, articulate symbol are understood only through the meaning of the whole, through their relations within the tonal structure” (Langer 97). Presentational symbols include paintings, dance, music, and other kinds of art forms. Some key aspects of presentational forms is that they do not necessarily require common understandings of various elements, such as words, as the logical relationships are simply presented for observation. Langer argues that presentational forms offer the ability to articulate ideas that cannot be articulated in discursive form due to its limitations, and thus this a key purpose of music.

One key area that discursive form does not articulate well but is articulated well by presentational form is what Langer calls the “inner life”. For Langer, the inner life is perhaps what some would call the emotional life of human beings, even though that does not quite adequately explain it (Langer 98). It is the felt experience of a situation and the very human ways that one might respond to or understand said situation other than explicit reasoning. Take for example the experience of standing before the Trevi fountain in Rome. Discursive form is very helpful for articulating things like the number of people there, the color of the sky, the height of the water, the time of day, or the temperature of the water. Discursive form can help to make a list of all the various objects present and the ways they are related. However, Langer would argue there is a felt experience of being there as a human being with respect to all these objects that cannot be articulated with discursive form. The way the wind feels in one’s hair, the tiny droplets of water from the fountain’s explosion that collide with one’s skin and cool it down from the warm rays of the sun, or that feeling of being around so many other people who are all there to see the same amazing object are just a few examples of things that cannot be well articulated in discursive form, even though it has been attempted here.

www.abbapublishing.com

7

While Langer’s theories may be compelling, there is at least one possible issue. Langer clearly states that presentational forms do not refer to an object or even a concept. Langer instead argues these forms “present” logical relationships for the subject’s conception. But it seems contradictory to claim a symbol does not refer to any object. Nelson Goodman offers a different theory of the relationship between symbol, concept, and object. Goodman postulates the concept of exemplification, in which a symbol represents an object by both possessing and referring to either labels or properties present in the represented object (Goodman 53). The example Goodman uses in Languages of Art is that of a sample of cloth and the whole piece. The sample of cloth symbolizes the larger piece by both possessing the redness, the softness, and the thickness of the larger piece, and also by referring to those qualities (Goodman 53-54). It is important that both possession and reference is present for symbolism to be happening as an identical whole piece of cloth does not symbolize the original whole piece as it is not referring to those properties even though it does possess them. This theory of exemplification bridges the gaps between presentational symbol, concept, and object without introducing any logical inconsistencies. In this way Goodman presents a clearer picture of these relationships, that may allow one to preserve Langer’s other important insights like logical analogy, the roles of connotation and denotation, and the inner life.

Acknowledgements

First, I would like to acknowledge the Berry Family and Honors Program, without which the Berry Summer Thesis Institute could not exist, and thus I could not have had this wonderful opportunity to work on this project. I would also like to acknowledge my fantastic mentor, Neil Florek, for all his work this summer to help me complete this project and push me to do the best work I could. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my fellow Berry Summer Thesis Institute scholars: Phillip Cicero, Jules Carr-Chellman, Daniel Vencel, Caitlin Spicer, Lizzy Herr, Tierra Freeman, Jeanne Serring, Jaylee Sowders, and Claire VanMeter. They made this summer such a joy and I am no doubt a better person because of them.

Bibliography

Goodman, Nelson. Languages of Art. Hackett Publishing Company Inc., 1976. Langer, Susanne. Philosophy in a New Key. Harvard University Press, 1957.

8

Lovecraft, the Uncanny, and the Sublime: A Psychoanalytic Critique of H.P. Lovecraft's Fiction

Jules Carr-Chellman1,2,3,4

University of Dayton

300 College Park, Dayton, OH 45469

1.Department of Philosophy

2.Department of English

3.Berry Summer Thesis Institute

4. University Honors Program

Thesis Mentor: Andrew Slade,

Department of English

Ph.D.

The ideas of the uncanny and the sublime are part of a philosophical tradition that lies at the intersection of psychoanalysis and the critical analysis of art and literature. Psychoanalysis, in a clinical context, works to understand crucial processes that compose the human being while also working to address problems that arise out of those processes. Psychoanalysis, at its core, seeks to answer the crucial questions facing the human condition from a human perspective and to help people live better lives because of it.

Psychoanalysis is also a way to understand the mediums through which we express our feelings, our opinions, and our ideas about who we are in art and literature. Art and literature are the medium for the interarticulation of our individual human experiences. Frida Kahlo, a Mexican painter, once said, “I paint flowers so that they will not die.” This quote summarizes how art is a means by which humans seek to try and fully articulate their ideas about themselves and other people, thereby bringing their perspective closer to being a part of shared human understanding. The field of psychoanalysis is important because of its crucial mission to think about what it is to be human, as it also serves as an essential critical lens through which to understand the expression of the human mind in art and literature. Psychoanalysis as critical theory will yield valuable insights into what it means to be a human being and how humans respond to the social, historical, and cultural problems that face us and our world.

The text that I will examine today was written by H.P. Lovecraft, an American author who, during the late 19th and early 20th century, published horror science-fiction titles such as The Call of Cthulhu (1928), At the Mountains of Madness (1931), and The Shadow Out of Time (1936). Lovecraft’s stories were virtually ignored by the general public until later authors of scholarship began paying attention to his work in the late 1970s, and ever since, scholars have mostly labeled Lovecraftian fiction as simply ‘grotesque’ or ‘weird.’ 1 There is more depth, however, to Lovecraft’s fiction than can be captured by these terms alone and also more complications. While I will not address these in this paper, my larger thesis project will include a section addressing Lovecraft’s racist and xenophobic tendencies. Thus, the aim of this project is to find the deeper meanings in Lovecraft’s texts’ by using a psychoanalytic lens. First, I will explain the Freudian concept of the uncanny, secondly, I will briefly articulate a Burkean understanding of the sublime, and finally, I will make the argument that Lovecraft’s fiction is rooted in elements of the uncanny and the sublime.

The uncanny is colloquially understood as something weird or bizarre that evokes a feeling of disease. A psychoanalytic conception of the uncanny is more than a surface level description of feeling, it emphasizes internal unconscious processes that are fundamental for human beings to exist. Freud says that it might be uncanny to repeatedly observe a number several times in different places throughout the day, or to meet someone that looks almost identical to ones’ spouse.

9

1Harman, Graham, Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy, (Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2012) vii.

More than just uncomfortable, according to Sigmund Freud, the feeling of the uncanny occurs when something that is meant to be buried in the unconscious mind comes to light.2 To further understand the Freudian conception of the uncanny, I will consider the first part of his essay where he etymologically dissects the Germanic roots of the word uncanny.

Freud begins his essay on the uncanny by etymologically examining the two German words Heimlich and unheimlich Heimlich can be translated in English to mean ‘homeliness,’ and unheimlich is understood to mean ‘unhomely.’ To be in one’s home is to be in a private space that is sheltered from the outside world. Thus, the German language secondarily defines the word homely to refer to that which is hidden, and unhomely to define something that has been unconcealed. In this investigation of German etymology, Freud observes a border between the meanings of homeliness and unhomeliness. This border is the place where the uncanny resides. The uncanny can be understood as a feeling that occurs when something familiar, that should be hidden, is revealed. Through a psychoanalytic lens, the things that are meant to be hidden are repressed experiences, ideas, or memories – these things are meant to be quite literally hidden from conscious experience. Freud’s argument, in The Uncanny, is that the reemergence of repressed ideas causes a feeling of uncanniness.

In the second chapter of Freud’s essay on the uncanny, he has several ideas about the experiences that he considers to be uncanny. Freud suggests that the uncanny can be prompted by a number of different things, like witnessing a person having a seizure, or the “repetition of the same thing,” such as numbers observed in a given day, or the “doppelganger,” which could occur in the form of seeing a person that looks identical to one's own acquaintance or themselves.3 As Freud will illustrate, the feeling of uncanniness comes from the partial excavation of ideas, feelings, and memories that have been repressed into the unconscious. The clearest example of the uncanny mentioned by Freud, I think, occurs when a human has a seizure because it physically reveals the electrical anatomical processes that lie behind the animated, nonmechanical essence of human behavior. Understanding a human being as nothing more than a robot is not a thought pattern that is sustainable, so the mind represses the idea or memory out of conscious thought where it will still exist but lay mostly dormant until we observe things that bring that repressed idea to light – then we feel uncanny.

One of Freud’s most provocative and famous ideas was his conception of the human psyche akin to that of a Roman city. Freud explains that the buildings and infrastructure of European cities can undergo destruction, war, and natural disaster, yet they are always rebuilt in a different way on top of the previous foundation.4 If one is walking around Europe, it is easily examined that most buildings, in some way or another, retain elements of a previous form of the building, but at a deeper and more hidden level. This is how Freud asks the reader to understand the human psyche in Civilization and its Discontents. While thinking about the uncanny, it is important to remember that no psychological change or development is ever lost in the human psyche; instead, the mind retains its current form and all previous forms.

Freud conducts an analysis of The Sandman by E.T.A Hoffman to demonstrate how a fictional narrative incites a feeling of uncanniness. Freud argues that the source of uncanniness in the story comes from the sandman himself, whose mythological task is to tear out the eyes of children.5 Through a psychoanalytic lens, the loss of one's eyes comes from a fear of castration, which is observable in The Sandman when Coppelius, the evil doppelganger of Nathaniel’s father, attempts

2Freud, Sigmund, The Uncanny. (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 124.

3Freud, Sigmund, The Uncanny. (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 142

4Freud, Sigmund, Civilization and Its Discontents, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2022),7.

5Freud, Sigmund, The Uncanny. (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 136.

10

to burn Nathaniel’s eyes with a chemical solution and then interferes with all of his love relationships. Freud’s central thesis is that the uncanny is a feeling that comes from repressed psychological material. My central argument in this paper, however, is that the feeling of uncanniness as theorized by Freud is more than an uncomfortable or bizarre experience, but instead, that the uncanny is rooted in more substantial feelings of terror. Take, for example, Freud’s analysis of the uncanny in The Sandman – it is not simply bizarre or strange to fear being castrated by having one's eyes gouged out, it is horrifying. Thus, a conception of the uncanny as simply strange is to misrepresent a feeling that is rooted in terror.

H.P. Lovecraft is skilled at creating a sense of the uncanny, and a prime example of this uncanniness occurs in his short tale “The Outsider.” The story is narrated by a mysterious being who, for as long as they can remember, has lived entirely alone in an inescapable dark castle surrounded by an endless expanse of trees. Eventually, the being feels impelled to escape his prison-like home and scales the ruins of the castle’s staircase, only to reach the top and discover that he has breached the surface of a new world “decked and diversified by marble slabs and columns, overshadowed by an ancient stone church…”6 Longing for human contact, the being scouts out a different castle filled with “an oddly dressed company, making merry, and speaking brightly to one another.”7 As soon as the being enters the castle, there “descended upon the whole company a sudden and unheralded fear of hideous intensity.”8 The being carefully searches for the presence that caused the terror, and upon finding it, reaches out to touch the creature’s paw only to feel “a cold and unyielding surface of polished glass” -- a mirror.9

This brief story constructs an environment through the perspective of the character, which gives the reader a way of understanding the character’s experiences as real within the narrative. The readers’ understanding that the beings’ experience is real becomes ambiguous when the being reaches out toward the monster and realizes that it is, in fact, a reflection of itself. This fits in with the characteristically uncanny feeling that arises “when the boundary between fantasy and reality is blurred.”10 The final moment in the story when the being encounters the monster as himself is an uncanny moment, specifically in the form of what Freud would call a “double” or a “doppelganger.” The uncanny, as we will recall, is “what one calls everything that was meant to remain secret and hidden and has come into the open.”11 For example, in Lovecraft’s short story “The Outsider,” the being in the tower recounts a memory of his first conception of the human form – he describes it as “something that looked mockingly like myself, yet distorted.”12 This is the moment when the being first conceived of someone other than himself – this distorted recollection of the initial encounter with the human form as resembling itself indicates the gradual repression of a narcissism that occurred early on in its life. The central idea here is that the being in Lovecraft’s “The Outsider” is recognizing a frightening distorted version of himself in other objects. This ultimately results in the degradation of the beings’ own self-image, which creates a terrifying sense of the uncanny.

So, we have evidence of a repressed idea in this story. Freud’s argument is that the uncanny experience of the “doppelganger,” or double, occurs when one observes, in adulthood, someone or something else that looks remarkably similar to oneself in reality.13 And this is exactly what

6Lovecraft, Howard P., “The Outsider,” (New York: Library of America, 2005), 11

7Lovecraft, Howard P., “The Outsider,” (New York: Library of America, 2005), 12

8Ibid

9Lovecraft, Howard P., “The Outsider,” (New York: Library of America, 2005), 14.

10Freud, Sigmund, The Uncanny, (New York: Penguin Books, 2003),150

11Freud, Sigmund, The Uncanny, (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 132.

12Lovecraft, Howard P., “The Outsider,” (New York: Library of America, 2005), 8.

13Freud, Sigmund, The Uncanny, (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 141.

11

happens at the end of the story when the being reaches toward the monster only to discover that his hands are touching a mirror, a reflection of himself, a doppelganger. The most significant portion of the story’s plot, when the creature touches the mirror, is tied to subtle details throughout the story in order to articulate an uncanny encounter with repressed infantile narcissism. The Outsider, therefore, is a weird story, it's a grotesque story, and it is, from beginning to end, a tale of an encounter with a feeling of the uncanny.

The goal of using psychoanalysis as a form of critical theory is to analyze pieces of art or literature to detect less obvious meanings or truths that might be ciphered within a narrative. This is done by thinking through the lens of the human psyche. The work of H.P. Lovecraft, and of any artist, is a part of cultural discourse; Lovecraft externalizes his interior life in his fiction. The uncanny is a deeply interior idea. Yet, there is a reason that it happens, and this reason, from the perspective of the psyche, is self-preservation and the uncanny is a feeling that occurs when that which is repressed returns.

Since we have understood uncanniness to be an interior affect, where do we see it externalized? The uncanny cannot be seen– it is felt, but what can be seen is the sublime. The sublime, as it is understood by Edmund Burke, is everything that elicits terror.14 Yet, the sublime is also a “form of self-preservation,” as Burke says, because the feeling of terror caused by something experienced outside of the body triggers a visceral response in the mind that works to preserve the self from death.15 In contrast to the uncanny, the sublime occurs because of an encounter with something exterior to the mind, while the uncanny is an internal mechanism within the psyche. Both concepts, however, seek to preserve the self. So, the uncanny is an internal designation for feelings associated with particular repressed images, and the sublime is a feeling often externalized in images of magnitude and power.

The being in The Outsider, for example, is never developed by Lovecraft. The reader does not know its species, its gender, its age, or what it looks like – all that is concrete is the fact that it exists. This is how the uncanny works in the human psyche – the mind is familiar with the existence of this repressed idea, but unfamiliar with the specifics of its form. At the end of the story, when the creature realizes that the monster is himself, he explains it like so:

“...in that same second there crashed upon my mind a single and fleeting avalanche of soul- annihilating memory. I knew in that second all that had been; I remembered beyond the frightful castle and the trees, and recognized the altered edifice in which I now stood; I recognized, most terrible of all, the unholy abomination of that which stood leering before me as I withdrew my sullied fingers from its own.”16

This is the moment in the narrative when the creature moves from being an internal uncanny idea, to being a full-blown externalized object capable of inciting sublime terror. The creature, through a psychoanalytical lens, could be understood as this completely unknown, yet familiar repressed idea that, when revealed or externalized, triggers a feeling of terror.

14Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 36.

15Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 79.

16Lovecraft, Howard P., “The Outsider,” (New York: Library of America, 2005), 13.

12

Earlier it was stated that The Outsider is a tale of an encounter with the feeling of the uncanny, and now, I have demonstrated that when this internal uncanny feeling becomes externalized, it incites a feeling of terror that constitutes an encounter with the sublime. The language commonly used to talk about this story, and most Lovecraftian fiction, are words associated with low culture, words like weird, grotesque, bizarre, or frightening. What I have shown today is that powerful emotion does not have to be positive, or high – quite the opposite – powerful and important emotions that fuel human self-preservation are oftentimes buried and terrifying. H.P Lovecraft wrote a body of fiction that contains feelings and ideas buried in unseen parts of the world that often make people uncomfortable, however, his misunderstood works still serve as a cultural container of human expression that ultimately define how we understand and preserve ourselves as people.

Bibliography

Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

Freud, Sigmund, Civilization and Its Discontents, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2022).

Freud, Sigmund, The Uncanny. (New York: Penguin Books, 2003). Harman, Graham, Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy, (Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2012.

Lovecraft, Howard P., “The Outsider,” (New York: Library of America, 2005).

13

Critical Review of Literature Surrounding 'Cultish' Evangelical Pastor Mark Driscoll

Phillip Cicero1,2,3

University of Dayton

300 College Park, Dayton, OH 45469

1. Department of English

2. Berry Summer Thesis Institute

3. University Honors Program

Thesis Mentor: Susan Trollinger, Ph.D.

Department of English

Abstract

This project focuses on the rhetoric utilized by Mark Driscoll in a series of blog posts that appeared on the Mars Hill Church website in late 2001 to early 2002. Using Amanda Montell’s theorization of the rhetorical characteristics of a discourse she calls “Cultish” in her book, Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism, this project identifies the various ways Driscoll’s rhetoric fits within her theorization of “Cultish.” The core of this project is a rhetorical analysis of Driscoll’s blog posts that seeks to demonstrate that his rhetoric mobilizes key characteristics of “Cultish.” Then, using Stuart Hall’s theorization of desire, identification, and investment in popular culture texts along with Judith Butler’s notion of subjectivation (the process by which we are always being constructed as subjects by the rhetoric within which we are immersed), this project will aim to explain how Driscoll’s “Cultish” rhetoric attracts and retains audiences one might expect would reject Driscoll. More specifically, this project will argue that Driscoll’s “Cultish” rhetoric has attracted white men who have felt emasculated and disempowered by neoliberal (and other dominant discourses) during late 20th and early 21st century American culture by constructing a “Cultish” form of “Christian” identity that aims to give these men a sense of masculine identity, power, and belonging. Driscoll’s rhetoric does this by constructing a homophobic and misogynistic form of “Christian” masculinity that he aggressively advances as the only form of “Christian” masculinity that is “good.” Thus, his rhetoric gives his reader two options: be actively and explicitly homophobic and misogynistic or admit that you have been “pussified” – that is, completely emasculated.

Introduction

Scandals involving white evangelical churches seem to appear daily in the news. Whether the scandals involve a male church leader engaging in bullying, sexual harassment, sexual abuse, financial fraud, or something else there seems to be no end in sight. The most recent news on the Southern Baptist Convention’s efforts to cover up the hundreds of sexual abuse cases committed by its leadership over the years provides one example of the systematic nature of this problem. One might imagine that in response to these scandals, white evangelicals would flee the churches where these leaders have or continue to serve through coverups or ignorance of the denomination. Only recently have the numbers began to dwindle at white evangelical churches. A notable example is Willow Creek, a white evangelical church with seven campuses and an attendance of more than 25,000 weekly members in 2017 (Smietana). Recently, however, the church has had to lay off thirty percent of their staff due to a 57 percent decrease in attendance following a major sex scandal among their top leadership (Smietana). That said, white evangelicals remain among the largest two religious groups in America (with mainline Protestantism as the other).

The apparent crisis within white evangelicalism invites us to ask why so many Americans remain

14

committed to churches (and other affiliated organizations) and especially to the leadership of those churches when those in charge have been proven to abuse their power in scandalous ways? For those who choose to stay, and many do, what continues to sustain their loyalty and keep them committed to these ministries that have failed them?

To answer this question, this project draws on the work of Amanda Montell whose book, Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism, explores what she argues are the distinctive characteristics of “Cultish” language and how that language attracts and retains adherents. Through the course of the book, she argues that the language of cult leaders is distinctive and that there are strong commonalities among the rhetoric of individual cult leaders. Her goal is to identify and describe those commonalities so that we can identify a “Cultish” discourse when we hear one and understand how it works. This paper explores the connections between “Cultish” and the rhetoric of white evangelical leadership and how it gains and retains adherents amidst scandals.

This project takes as its case study the rhetoric of Mark Driscoll, a pastor who was heavily criticized and removed from his now defunct megachurch, Mars Hill, for aggressive language and bullying. But to understand Driscoll, who he is, why he is important and worth studying, it is important to have some understanding of the discursive context his rhetoric emerged within. To understand that, a brief history of white evangelicalism is needed.

Evangelicalism all begins with the rise of fundamentalism, which came about in response to modernism and historical criticism critical readings of the Bible. Historical criticism is a reading strategy that emerged from modernism that treated the Bible like any other book- with a history, tensions, and contradictions, written by human beings in history instead of God. A scientific theory of evolution also emerged during modernism called Darwinism, which challenges the creation story of the Bible through the process of evolution. In response, Fundamentalists developed something called biblical inerrancy. Biblical inerrancy is the belief that the Bible is completely and truly inerrant, meaning that it is true in all that it says about both history and science. This all culminated in the popular Scopes trial where John Thomas Scopes was put under trial for teaching evolution in his high school science class which went against Tennessee state law. William Jennings Bryan, a popular fundamentalist and politician, joined the prosecution against Scopes, but the trial did not go as Bryan had hoped. The defense put Bryan and biblical inerrancy through a humiliating examination that culminated in public ridicule. While Bryan and the Fundamentalists won the trial, they had been humiliated on a nationwide scale and moved out of the national spotlight to focus on building a network of organizations (like radio stations and private school) which assisted neo-evangelicals when they returned to the public sphere. Neo-evangelicals arose in the 1960s and 70s to change the public perception of fundamentalism after the shameful reputation they gained from the trial. Hoping to “soften” fundamentalism and make it more credible and relevant, neo-evangelicals offered what can essentially be described as a re-branding of fundamentalism that consisted of all the same beliefs of fundamentalism presented in a more appealing way. This is where the problem of masculinity comes from within the evangelical community. The biggest issue for evangelicals at the time was the connection between them and femininity. Most people, when thinking about evangelicals, associated them with not being “manly” men or something that women should be associated with. Masculinity, therefore, has been a core principle for evangelicals and something that has been at the focus of their message for a long time.

Out of all the white evangelical leaders out there, this project chooses to focus on Mark Driscoll because of his overzealous and aggressive language that stood out among other white evangelical leaders. The other interesting thing about Driscoll was how he presented his arguments at Mars Hill. The services at Mars Hill consisted of rock bands playing religious songs, a young audience

15

consisting of 20–30-year-olds, and an unabashed pastor (Driscoll) not afraid to talk about topics like sex, porn, and other taboo topics. This project focuses specifically on Driscoll’s blog posts during a 2-month period in late 2000 to early 2001 because they appear to resonate heavily with “Cultish” and emphasize the offensive nature of Driscoll’s rhetoric.

The methodology used for this examination of Driscoll’s rhetoric and its connections with “Cultish” first began with a content analysis of his blog posts. The purpose of the content analysis was to organize each blog post into two categories: unprompted posts and responses. Those posts were then organized into subcategories of statements drawn from Montell’s work with the purpose of understanding how certain notable statements of Driscoll’s function in the context of his larger rhetoric. Based on the content analysis, the next methodological move was to conduct a close reading of Driscoll’s posts with respect to Judith Butler’s notion of subjectivation in mind to discern how Driscoll’s rhetoric was shaping white evangelical masculinity. This paper argues that Driscoll’s particular cultish rhetoric constructs a Christian identity that goes well beyond common arguments of complementarianism (the idea that men and women have different but equally valuable roles and that men should be in charge) to an intensely misogynist and homophobic identity for what he considers “good Christian men.” This literature review summarizes especially valuable secondary sources that have shaped and will continue to shape this project. It is organized into three sections representing two key terms for the project (evangelicalism and militant masculinity) and, of course, the subject of my project – Mark Driscoll. The sources summarized have helped me to better understand the direction of this project.

Evangelicalism

The core of this project is focused on Mark Driscoll, and, therefore, a more extensive understanding of evangelicalism is needed to understand Driscoll’s misogynist and homophobic rhetoric. Three sources have proven especially helpful in understanding the origins of evangelicalism at a deeper level. The first of those is Margaret Bendroth, who describes Fundamentalism as following five fundamentals: the virgin birth, substitutionary atonement, resurrection, miracles, and biblical inerrancy. She also describes fundamentalism as inherently anti-intellectual (Bendroth 4). Another source that is helpful in understanding evangelicalism is Molly Worthen who describes evangelicalism as a broad concept that cannot be easily defined but mentions that practices that emphasize fundamental doctrines and born-again experiences are indicators (Worthen 4). Kirsten Kobes DuMez, another source, describes evangelicals as people who believe in biblical inerrancy, born-again experiences, and evangelization. She also argues that, while evangelicals certainly identify with those doctrines, but she also argues conservative politics are central to their identity as well (DuMez 5). Both DuMez and Bendroth also help describe the neo-evangelical movement. The neo-evangelical movement, aka new evangelicals, was a period post WWII and heavily in the 1970s where evangelicals tried to broaden their appeal to the public while still maintaining the same beliefs (Bendroth 5). Bendroth and DuMez then discuss the types of strategies and rhetoric that emerged during the neo-evangelical period. Bendroth and Worthen’s work helps this project in its understanding of the overlap between fundamentalism and evangelicalism. Bendroth and DuMez are also helpful in explaining the neo-evangelical period, which is the period where Driscoll gained popularity. This project hopes to build upon these sources by focusing on what Driscoll contributed to the neo-evangelical period and how much he aligns with their definitions of evangelicalism.

Militant Masculinity

Bendroth writes in her book Fundamentalism and Gender that evangelicals used language akin to “militant masculinity” long before neo-evangelicals popularized it in the 70s. Bendroth describes

16

how in the 1920s, the masculine language utilized by evangelicals became more combative in hopes of making Christianity appear less effeminate and pastors depicted as more masculine (Bendroth 64). White evangelicals hoped to construct a Christianity that was less effeminate and connected more with masculinity. Going beyond just the leadership, white evangelicals wanted male members of churches to be looked at as “full-blooded” men. Bendroth describes that, to show their masculinity, pastors began to emphasize their fondness for outdoor sports, would always carry pistols on them, and were not afraid to walk the mean streets of New York’s red-light district. Bendroth’s work reveals that masculinity has been at the core of evangelicals message for decades. (Bendroth 65-66). DuMez writes about how the message from 1920s evangelicals was taken a step further in the 70s with the introduction of militant masculinity.

The term militant masculinity comes from DuMez’s book, Jesus and John Wayne, in which she describes how militant masculinity became ingrained in evangelical culture. DuMez describes in her book how Christian media and notable figureheads, such as James Dobson and Billy Graham, promoted a specific type of white evangelical masculinity, specifically one that highlights a heroic masculinity perhaps best exemplified by popular culture versions of cowboys– like John Wayne. Militant masculinity became part of evangelical culture as events like the Vietnam War, secondwave Feminist movement, and Civil Rights movements were threatening the evangelicals’ important values of family, sex, power, and race (DuMez 12). This period in the 70s during the Vietnam War and social movements is when white evangelicals began to discern what was good and bad in the world by pointing to the symbols of the past, like John Wayne’s cowboys and Mel Gibson’s warrior character, William Wallace, in Braveheart. Evangelicals pointed to the bravery, aggressiveness, and violence that these symbols from the past represented and argued that these were good characteristics for Christian men to have (DuMez 12). The defining of what is good and bad based on agressive symbols of the past is what DuMez describes as militant masculinity, and she argues that this militant masculinity is tied with a culture of fear that calls Christians to arms against the “forces of evil” in the world (with those forces of evil being feminists, other races, and anti-war protestors). Pastors like Tim LaHaye, Bill Gothard, and Mark Driscoll utilized militant masculinity to garner large audiences by generating fear in their audiences towards the “forces of evil” they would determine (DuMez 13).

The work Bendroth has done provides an important contribution in understanding how masculinity has been at the core of evangelical’s arguments for more than 100 years. This work helps understand the origins of Driscoll’s masculine rhetoric and the connections it has with evangelicals from decades before. DuMez’s work on militant masculinity and how it has been used to generate fear within audiences puts the strategies that Driscoll uses to garner audiences in a brighter light. This project is going to focus specifically on how Driscoll was able to garner large audiences through the use of fear but also on what people are identifying with in Driscoll’s language.

Mark Driscoll

Given that this project is a case study of Mark Driscoll’s rhetoric, secondary sources on him as an important figure within white evangelicalism are essential. DuMez’s book, Jesus and John Wayne, provides helpful insights into the man and his rhetoric. The chapter titled “Holy Balls”is particularly helpful because it focuses on Driscoll and the language he used as a pastor at Mars Hill Church. DuMez describes how Driscoll would preach about a “manly-man” Jesus who was an aggressive warrior that rides into battle against the devil (DuMez 194). She talks about how Driscoll became known as “Mark the cussing pastor” who was not afraid to talk about sex in vulgar ways and did not tolerate any of the soft rhetoric, such as acting as your friend or personal enrichment,

17

that other pastors, like James Dobson, would use to talk about Christianity (DuMez 194). The most striking point DuMez makes is in reference to the series of blog posts posted in late 2001 under Driscoll’s pseudonym, William Wallace II, that provide further evidence of Driscoll’s hyper- militant masculinity rhetoric and, thereby, provides an opportunity to understand exactly what was going on in that rhetoric. These posts are what I analyze in this project, and she describes that these blog posts reveal the misogynistic, homophobic, and downright offensive language Driscoll used to preach his beliefs in a much harsher way than other evangelicals had done before (DuMez 195). DuMez provides helpful insight into Mark Driscoll’s career as a pastor and how he utilized hypermilitant masculinity rhetoric. I hope to build upon her work with Driscoll’s blogs by using Butler’s notion of subjectivation and Hall’s theory of identification to understand the ways in which Driscoll’s militantly masculine rhetoric mobilized the desires of emasculated white evangelical men on behalf of identification with his concept of the ideal man.

Jessica Johnson’s book, Biblical Porn, is the only book-length study of Driscoll’s career during his time at Mars Hill Church. Johnson’s book examines how Driscoll’s audiences were recruited into thinking of power through sexual and militaristic means (or Driscoll’s teachings) through a concept called “biblical porn”. “Biblical Porn” refers to the affective labor (something being done to shape someone’s emotions or desires) of branding Driscoll’s teachings on masculinity, femininity, and sexuality as a marketing strategy to bring in more members (Johnson 7). Using Michel Foucault’s teachings on “knowledge of pleasure,” she describes how members of the Mars Hill church were essentially trained to embody Driscoll’s understandings of masculinity, femininity, and sexuality through the nature of his discourse (Johnson 8). Johnson explains this phenomenon as something like a multi-level marketing scheme (MLM) where the person at the top of the chain (Driscoll) recruits members who learn his teachings and then, either voluntarily or involuntarily, end up bringing in more members through the beliefs that are “theirs” but stem from Driscoll. Johnson’s insights provide a new understanding of how Mars Hill worked as an organization that brought in new members and retained current members with unique strategies. It also provides insight as to how Mars Hill functioned with Driscoll at its head and how integral Driscoll was to Mars Hill’s success. Since this project looks at blog posts written during his time at Mars hill but appeared after the fall of Mars Hill, it extends Johnson’s work by taking it further toward the present and enables comparisons among his rhetoric before and after his time at Mars Hill.

Conclusion

This literature review focuses on key secondary sources that shape this project. Bendroth, Worthen, and DuMez all show the importance the Bible, conservative politics, and the neo-evangelical movement are to understanding the ways Driscoll came to become so influential in the white evangelical world. Bendroth’s work in Fundamentalism and Gender reveals that masculinity has been at the core of white evangelicals’ identity for the past 100 years, and DuMez’s work in Jesus and John Wayne reveals that militant masculinity and the construction of “real men”as aggressive, brave, and violent became ingrained in evangelical culture following the many sociopolitical movements of the 70s. In addition, DuMez’s work with Driscoll’s blog posts argue that Driscoll’s rhetoric takes militant masculinity further than other white evangelical leaders at the time provides a framework for this project to analyze the ways in which Driscoll’s militantly masculine rhetoric mobilized the desires of emasculated white evangelical men. Lastly, Jessica Johnson’s book-length work in Biblical Porn provides insight into the organization that Mars Hill was, the ways they gained and retained new members, and what Mars Hill was like under Driscoll’s leadership. This project aims to contribute a deeper understanding of Driscoll’s rhetoric through the theorization of Montell’s “Cultish” which makes it possible to understand the rhetorical processes by which Driscoll’s blog posts attracted and retained an audience in terms of identification and subjectification.

18

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Berry Summer Thesis Institute and the University of Dayton Honors Program for providing me the opportunity to conduct this undergraduate research opportunity, as well as my mentor, Dr. Susan Trollinger, for helping to guide me through my work this summer. I would also like to thank the English Department for its help with resources and the Berry family for its support. Lastly, I would like to thank my cohort for an amazing experience this summer.

References

Bendroth, Margaret Lamberts. Fundamentalism and Gender, 1875 to the Present. Yale University Press, 1993.

DuMez, Kristen Kobes. Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. W.W Norton and Company, 2020.

Johnson, Jessica. Biblical Porn: Affect, Labor, and Pastor Mark Driscoll’s Evangelical Empire. Duke University Press, 2018.

Smietana, Bob. “Willow Creek Cuts Staff Budget by $6.5 Million.” Christianity Today, May 2022. Worthen, Molly. Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism. Oxford University Press, 2013.

19

Music Therapy Treatment Considerations for Adolescents with Attachment Challenges

Jaylee Sowders1,2,3

University of Dayton, 300 College Park, Dayton, OH 45469

1. Department of Music

2. Berry Summer Thesis Institute

3. University Honors Program

Thesis Mentor: Joy Willenbrink-Conte, MA, MT-BC

Department of Music

Abstract

Attachment theory, developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, describes how our first relationships guide much of our social and emotional development throughout life (Bretherton, 1992). When attachment challenges occur, particularly during infancy, the maturation of adolescents as they transition into adulthood is severely impacted. However, the foundation of attachment assessment and treatment are rooted in classist, patriarchal, and white supremacist systems that do not equitably serve a diverse society. With a focus on equity and accessibility in mental healthcare, this study is focused on music therapy assessment and treatment with teenage clients facing attachment challenges and the role of music as a communicative tool and symbolic object for attachment. Through an interpretivist review of attachment theory and music therapy literature, combined with an analysis of relevant music therapy case studies, I will analyze the affordances, risks, and challenges of music therapy experiences in reforming and revising internal working models of attachment (Bowlby, 1969), using a dimensional perspective described by Raby et al. (2021). Music has the potential to address, validate, and promote further inquiry of the social and emotional complexities that often result from traumatic interpersonal relationships. The added musical relationships and music inherent to music therapy may provide new avenues for growth and healing by providing additional objects or secure bases for reconstructive attachment and relationship formation. This research will provide information for current and future music therapists facilitating music therapy with adolescents to address attachment challenges.

Introduction

Music therapy is constantly evolving to promote progressive, integrative, and equitable values in the practice. Individuals with attachment challenges represent a large, but minimally researched client group that has begun to strike therapists’ gaze as attachment and relationship challenges become more apparent in modern society. Although challenges often originate in infancy, attachment behaviors come to light during adolescence as individuation occurs and teenagers seek their own relationships. As music therapy emphasizes the relationships between the client, therapist, and music, it provides external objects and a therapeutic environment that may address and validate their potentially traumatic attachment experiences. Through the integration of attachment theory in current music therapy practice, adolescents with attachment challenges may be supported in reforming and revising internal working models through symbolic and musical methods of expression, reflection, and communication, ultimately fostering positive attachment orientations and behaviors. The following literature review begins with a survey of attachment theory literature, relates attachment theory to the context of adolescence, and finally, discusses music therapy literature pertaining to work with adolescents who are likely encountering attachment challenges.

20

Attachment Theory Foundations

Bowlby and Ainsworth Theory

Attachment theory is fundamental to an understanding of clinical engagement, such as music therapy, with adolescents with attachment challenges. Developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, attachment theory articulates the psychological foundations for relationship formation (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991). Their theory, influenced by Freud and other prominent psychologists of the time, emphasizes the importance of infant-mother attachment and the role such relationships play upon an individuals’ development. Bowlby provided many of the key ideas and definitions that formulate our current understanding of attachment, whereas Ainsworth provided the methodology to study and support the theories (Bretherton, 1992). Bowlby and Ainsworth’s theory of attachment remains one of the most influential and referenced psychological theories in practice.

Dominant western values related to socialization and upbringing elevates the significance of the parent-child relationship during infancy, specifically identifying it as the most important attachment relationship during child development. Bowlby suggests that these parental attachment relationships are imperative for “ego and super-ego development” (Bowlby, 1951, p. 53). Therefore, attachment is a “biological imperative” (Sroufe, 2021, p. 18) and a “domain” within relationships “concerned with seeking and provision of comfort and feelings of safety” (Fearon & Schuengel, 2021, p. 25). It is not the only relationship domain, and not all significant relationships are attachments. Attachment is usually characterized by a “strong desire to share feelings [with the attachment figure], greater emotional reactions when encountering them, more distress or concern upon being separated from them, and more intense grief upon their loss” (Sroufe, 2021, p. 18). According to Fearon & Schuengel (2021), we know very little about how relationships acquire an attachment domain. However, in Bowlby and Ainsworth’s theory of attachment, “attachment relationships promote security,” or intimacy, over familiarity (Sroufe, 2021, p. 21), and the child often derives an understanding of security (or lack thereof) from parental relationships. The nature of one’s parental or primary attachment relationships over time affects the formation and quality of additional attachment figures, in addition to the consistency and reliability of those additional figures.

Early attachment theory research suggested that the primary attachment figure in the infantparent relationship was limited to mothers. However, since attachment theory’s beginnings, attachment relationships have “been extended to children’s relationships with fathers and child care providers, relationships between adult romantic partners, and even relationships with siblings, close friends, teachers, and coaches” (Thompson et al., 2021, p. 4). Nonetheless, especially in infancy for Western societies, primary attachment roles and responsibilities are typically placed upon members of the nuclear family. When the primary attachment figure(s) is not present in a time of need, this can lead to changes in the infant’s mental representation of themself and others (Thompson et al., 2021, p. 4). Thus, according to Bowlby, “family experiences” are the basic “cause for emotional disturbance”(Bretherton, 1992, p. 3). This research, however, is not presented to blame emotional disturbances or attachment challenges on the attachment figures or the upbringing of a child or adolescent. Instead, it is meant to provide knowledge and support for a growing generation of individuals with extraordinary responsibilities, unique pressures, and who face systemic barriers to healthy and productive engagement as a primary attachment figure. As Bowlby suggests, “if a community values its children it must cherish their parents” (Bowlby, 1951, p. 84).

21

Internal Working Models

One of John Bowlby’s greatest contributions to attachment theory is his discovery and description of internal working models (IWMs) (Bowlby, 1969). IWMs are adaptive and “active constructions” of mental representations regarding the self, others, and the world, meant to further protect individuals from subjective threat or harm (Cassidy, 2021, p. 104). More specifically related to attachment relationships, IWMs “anticipate the attachment figure’s likely behavior across contexts” to allow the child to discern its level of security and still maintain energy for other tasks (Cassidy, 2021, p. 104). According to researchers Ross Thompson, Jeffry Simpson, and Lisa Berlin, these “internalized mental representations of relationships” can affect the “behaviors, thoughts, and emotions” within an attachment relationship (2021, p. 4). Filtered through their IWMs, individuals constantly assess others for potential threats to their “social connections, resource and goal attainment, and self-regulation” (Cassidy, 2021, p. 104). IWMs have “predictive, interpretive, and selfregulatory functions owing, in part, to their influences on attention and memory,” and directly impact not only present attachment relationships, but future attachment formation (Thompson, 2021, p. 129).

Besides contributing to a constant assessment of others and the world, IWMs impact identity, esteem, and an individual’s sense of self. As IWMs develop, beginning in the first year of life, early attachment experiences are pertinent to an individual’s persistent model of self (Cassidy, 2021, p. 104). As their ego and super-ego [sic] is not fully developed, an infant’s understanding of self is also often confined to a mirror of their attachment figure; meaning, their model of self is “closely intertwined with the IWMs of attachment figures” (Cassidy, 2021, p. 105). Similarly, two primary needs during infancy lead to a positive model of self: comfort and protection, and the ability for independent exploration. If an attachment figure provides both of these needs, the child is “likely to develop an internal working model of self as valued and reliable” (Bretherton, 1992, p. 23). If these needs are not met, infants, children, and adolescents alike often increase “bids for attention” by showing extreme dependence on the parent or attachment figure, often sacrificing their understanding and expression of self (Cassidy, 2021, p. 108). Ultimately, challenges in forming and maintaining attachments often originate within a negative IWM of self, others, or the world. Through therapeutic interventions involving the help of a therapist or an object serving as a reliable base for secure attachment, IWMs may transform and improve (Bretherton, 1992, p. 26).

Secure Base

To be attached is to explore with the protection of a secure base, according to Mary Ainsworth (1967). She coined the term “secure base” in her research with Ugandan infants and it was further developed in her study with the Strange Situation. With her foundations in security theory, one of the major principles that transferred to attachment theory is that “infants and young children need to develop a secure dependence on parents before launching out into unfamiliar situations” (Bretherton, 1992, p. 4). The secure base acts, not as a limitation for the child, but instead a central point or haven to return to intermittently while exploring or playing (Ainsworth, 1967). These specific attachment figures are expected to provide “protection, comfort, and relief” while “encouraging autonomous pursuit of non-attachment goals” and still remain readily available (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2021, p. 40). The attachment figures’ presence and support act as the “building blocks” for more complex IWMs to develop (Cassidy, 2021, p. 105).

Secure bases are often illustrated through examples of infant and toddler play. In a secure attachment, the child will often separate from the secure base to explore and play, but return periodically for reassurance. The accessibility of the attachment figure shapes the IWM. Besides

22

“sensitivity” and “promptness” of adult responses, the environment in which the attachment relationship forms plays a large role in sense of security (Ahnert, 2021, pp. 33). Shaver & Mikulincer propose that children may even have “context-specific” attachment figures (2021, p. 40), that, even for more insecure individuals, can act as “islands of security” in various contexts throughout socialization (2016, as cited in 2021, p. 42).

Furthermore, secure bases are not limited to guardians or care-providers. As an individual matures, a greater variety of “relationship partners” may become attachment figures and secure bases (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2021, p. 40). In adolescence and adulthood, even the recollection or thought of a real or imagined secure base offers the individual comfort and resources for approaching stressful situations. This sense of security is described as a phenomenon that is “partly ‘felt’ (emotionally), partly assumed and expected (cognitively), and partly unconscious” (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2021, p. 42). This security and maturity ultimately allows IWMs to also develop into a more stable mental representation and include the observed behaviors of others that was not possible in childhood (Ahnert, 2021). Therefore, security in childhood is optimal for development into adolescence and adulthood, where individuals have more choice and autonomy in their attachments. Challenges in attachment are often ignited from insecurity in a child's formative years, leading to a negative model of self or others. However, with appropriate intervention, adolescents can reform these IWMs to promote positive secure base formation and attachment security in future relationships.

Attachment Orientations

Attachment styles and orientations can reflect an individual’s model of self and others determined by their IWMs within attachment contexts. The Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) originally identified three primary classifications of attachment: insecure-avoidant, insecure-ambivalent, and secure (Jacobvitz & Hazen, 2021, p. 48). Since this experiment, fearful or disorganized attachment has been recognized as a fourth classification, and the original titles of each style have been refined and adjusted for adults and maturing individuals. Jacobvitz & Hazen explain that “the three types of insecure attachment classifications- dismissing, preoccupied, and unresolved- are based on the avoidant, ambivalent, and disorganized classifications of infant-caregiver attachment” (2021, p. 48). Moreover, the dismissing and preoccupied classifications have become synonymous with avoidant and anxious attachment orientations. Throughout this research, the terms secure, anxious, avoidant, and fearful will be utilized to name and differentiate attachment styles.

Attachment orientations are characterized by external behaviors representing internal models of self and others. Thus, they are useful for therapeutic assessment and understanding the diverse and evolving spectrum of an individual’s behaviors within relationships that contributes to their general attachment style. Attachment style is a defined and evidence-based classification that is not merely based upon temperament; it is a “lifelong process influencing humans’ capacities to form and maintain our closest relationships” (Jacobvitz & Hazen, 2021, p. 46). Past relationships ultimately affect our attachment orientation, or behaviors, in future relationships, and future relationships can continue to impact our attachment trajectories and understanding of both past and future relationships. An individual’s attachment orientation is an actively evolving cognitive, social, and emotional process (Jacobvitz & Hazen, 2021).

Individuals with secure attachment styles often expect that the “awareness of, reflection on, and expression of feelings, desires, and thoughts will result in positive outcomes” (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2021, p. 43). Furthermore, Shaver and Mikulincer, key contributors to the study of attachment, thoroughly define secure and insecure styles of attachment in relation to IWMs:

23

"People with a secure attachment orientation or style habitually hold positive beliefs about self and others across different relational contexts, whereas people with a less secure style hold these positive beliefs only in contexts in which actual or imagined interactions with a responsive relationship partner arouses feelings of being loved and cared for."

(Shaver & Mikulincer, 2021, p. 43).

Ultimately, secure attachments in a western context are considered optimal. A sense of security can allow individuals to focus their mental resources on “pro-social and growth-oriented activities” instead of preparing “preventive, defensive maneuvers” (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2021, p. 44). Secure attachment enables confidence in a significant context of a person’s life, which allows them to focus on growing within the other contexts (Sroufe, 2021). For insecurely attached individuals, therapeutic interventions often promote the concept of “earned security,” which describes the process of reworking IWMs to achieve a secure state of mind within attachment relationships, despite previously insecure or fearful experiences with attachment (Jacobvitz & Hazen, 2021, p. 50).

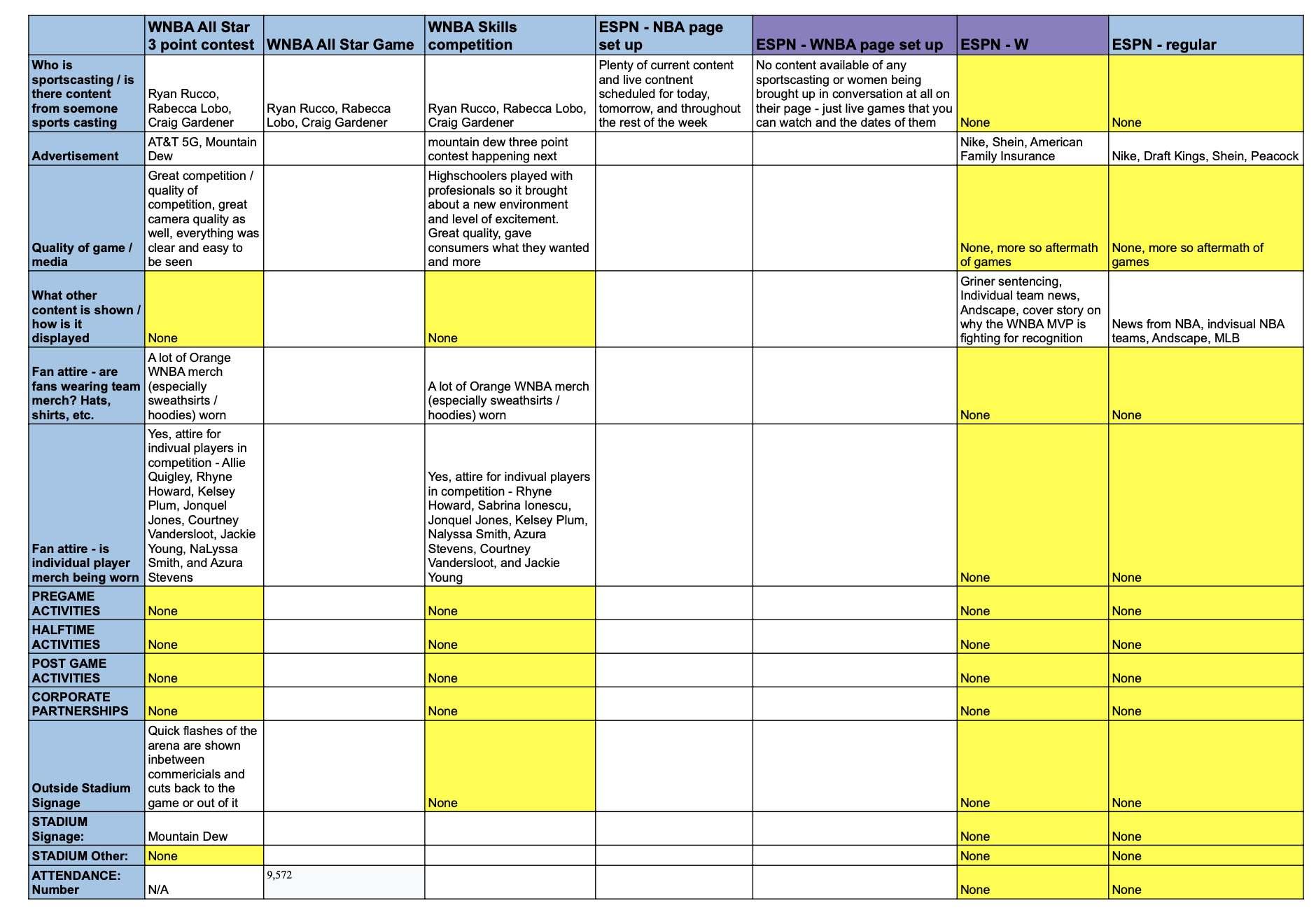

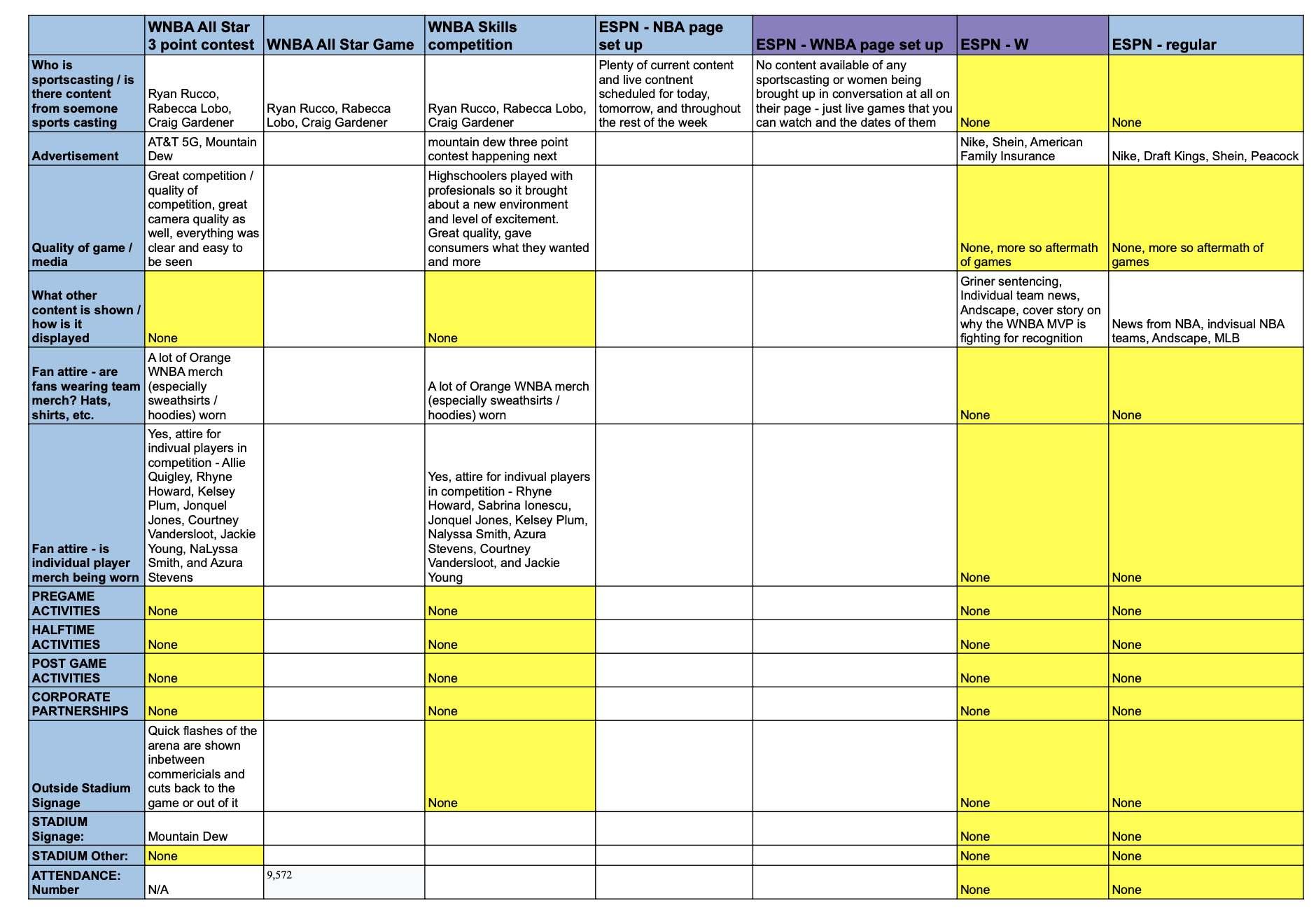

This literature review centers the dimensional perspective of attachment, a modern and salutogenic approach to understanding attachment orientations, primarily described by Raby, Fraley, and Roisman (2021). The dimensional perspective employs continuua, rather than distinct categories, which allows for an understanding of attachment as characterized by fluidity over time and across situations. This also accounts for diversity of attachment behaviors within attachment orientations and behaviors, as researchers have begun to acknowledge that differences in attachment qualities tend to appear in a matter of “degree rather than kind” (Raby et al., 2021, p. 73). Another consideration for using this model to analyze attachment lies within the axes that this two-dimensional continuum describes (See Figure 1). Raby and colleagues describe the two axes of their model as the degrees to which external behaviors reflect internal mental representations:

The first dimension involves the degree to which individuals are comfortable engaging with versus defensively avoid attachment-related thoughts, feelings, and relationship partners, whereas the second dimension involves the degree to which individuals exhibit emotional distress versus are emotionally composed in attachment situations. (Raby et al., 2021, p. 73).

These axes, labeled “emotional distress” (or “composure”) and “relational avoidance” (or “engagement”), directly relate to the IWMs of self and others. Often, psychologists will rename these axes “model of self” for the y-axis, and “model of others” for the x-axis to specifically refer back to IWMs of attachment relationships. This correlation between IWMs and attachment orientations allows for a better assessment of the potential internal and external processes within the therapeutic relationship during intervention.

24

Dimensional Perspective of Attachment

Attachment Assessments

Attachment assessments are typically conducted as the first step in treatment. Since its creation in 1985, one of the primary attachment assessments utilized post-infancy is the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) (George et al., 1985). Although originally created for adults, the content has been adapted to better fit the needs of adolescents. The AAI, according to psychologists, is designed to unveil the unconscious and reveal “defensive processes that may impair adults’ abilities to provide a secure base and safe haven” within their current and future attachment relationships (Jacobvitz & Hazen, 2021, p. 47). This assessment is designed to be objective and categorical to encourage communication about generalized attachment orientations and behaviors, similar to diagnostic assessments (Steele & Steele, 2021). Through dialogue, the assessor notes and analyzes specific signs of stress when the assessee recalls attachment experiences, and uses this information to identify attachment behaviors. However, attachment quality and behaviors are identified through

25

Figure 1

Note. From Raby, K. L., Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2021). Categorical or dimensional measures of attachment?: Insights from factor-analytic and taxometric research. In R. A. Thompson, J. A. Simpson, & L. J. Berlin (Eds.), Attachment: The fundamental questions (pp. 70-78). The Guilford Press.

“coherent, organized language” (or lack thereof). More specifically, security is “scored” through observations of “language, organization, believability, and flexible transitioning between generalized and specific memories” (Crowell, 2021, p. 87). A new wave of music therapy research suggests that attachment assessments may also be facilitated through music therapy techniques that combine music and verbal communication.

Attachment and Adolescents

Adolescence represents a period of immense change. The following literature primarily explores development through the lens of attachment theory, however, there are many more systems that contribute to an adolescent’s development within an attachment context than their level of security in relationships (Sroufe, 2021). Duboi-Comtois and colleagues suggest that adolescents' attachment behaviors are characterized by numerous changes:

Adolescent attachment is the result of both the adolescent and parent’s capacity to redefine their attachment relationship by taking into consideration the individuation process, that is, developmental changes at the social, cognitive, and emotional levels (Dubois-Comtois et al., 2013, p. 1)

To protect adolescents’ processes of individuation and growing independence, attachment becomes a “state of mind” or “symbolic” element rather than a physical presence. Attachment still guides much of the individual’s thoughts, behaviors, and coping mechanisms, but through a reformed relationship with attachment figures and secure bases (Dubois-Comtois et al., 2013, p. 2). This process of individuation changes the fundamental question surrounding mental representations within attachment from: how accessible is my attachment figure, to: “Can I get help when I need it in a way that doesn’t threaten my growing need for autonomy?” (Allen, 2021, p. 165). Adolescence is a period of development marked by the independence to shape their own new and changing relationships, which in turn affects their attachment patterns (Allen, 2021). With all of these new processes and transitions, an adolescent’s attachment security and the mental representations of self, others, and the world are constantly fluctuating. According to psychologist Allen, “stability is logically the wrong thing to be looking for” when working with adolescents and teenagers (2021, p. 163).

Coupled with the tumultuous process of individuation, adolescents’ brain development is not complete until adulthood, meaning adolescents are extremely responsive to attachment-related changes that occur during this period of development. Hughes, a psychologist with expertise in attachment focused treatment, suggests that attachment ruptures can significantly and directly impact cognitive functioning during this time (2014). Although inconsistent with Freudian theory, current research suggests that environmental changes, such as school or home location, can also significantly affect an individual‘s attachment system and processes (Allen, 2021).