All in for learning

Te Tupu: cross-agency support for ākonga

Growing resilient schools Gym programme helps student re-engagement

Start planning your professional development to expand your skills and get ahead. UC has postgraduate options specifically designed for working professionals in education. Part-time and distance study make your learning even easier. Talk to us today about studying next year.

Gain confidence to embed Māori knowledge and culture into your teaching. Flexible term-based learning with noho marae, day wānanga and night classes.

Be a part of language revitalisation for Aotearoa and help immerse mātauranga and te reo Māori into everyday learning in bilingual, immersion and mainstream settings (New Master’s degree subject to Te Pōkai Tara | Universities New Zealand CUAP approval, due December 2022).

Explore the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals and build your leadership, management and entrepreneurial skills around practical applications in your school community.

Gain the skills, knowledge and capabilities to be adaptable in the face of future English language developments, as well as technological advances.

Improve your professional practice and examine significant issues we are facing in education. Choose from courses in E-Learning and Digital Futures, Inclusive and Special Education, Leadership, Literacy, Teaching and Learning Languages and more.

Begin a professional doctorate to investigate an area in education you are passionate about. Choose between a cohort-based approach (EdD) or the traditional research-based approach (PhD), both involve completing an independent thesis.

This is a powerful whakataukī and a challenging one. Thank you for the work you have done in the past year against a backdrop of three years of disrupted learning, coupled with many communities being under considerable pressure.

Many of you have been involved in initiatives to get children and young people present, participating and progressing in their learning. Tai Tokerau schools and kura came together to launch Let’s Get to School Tai Tokerau, a campaign to raise awareness about the importance of regular attendance. A focus on strengthening connections with whānau and the wider community is having a positive impact on attendance at schools such as Waltham School and Addington Te Kura Taumatua in Ōtautahi Christchurch. And many of you are involved in removing barriers to ākonga engagement through the provision of breakfast programmes; participation in Ikura | Manaakitia te whare tangata (free period products); Ka Ora, Ka

Ako | Healthy School Lunches; Duffy Books in Schools, and provision of (or support to get) digital devices.

This year has also presented opportunities to reflect on what we’ve all learned as we’ve navigated the pandemic, and what we might do differently going forward. To support this learning, Erika Ross and Steve Lindsey interviewed school leaders across the country to capture their experiences of leading their communities through Covid-19. Many talked about exploring new ways to engage their students and families, giving students more agency, making wellbeing a priority, and recognising the importance of collegial support.

I was pleased to hear a number of the interviewees describing strengthened relationships with their local Te Mahau team. Growing these relationships and improving the support that we provide to you through Te Mahau will continue to be our priority for 2023.

Thank you again for your mahi this year. Please take the time over the summer to rest, reconnect, and do the things that refresh and recharge you.

Ngā mihi nui Iona Holsted, Secretary for Education

To view the PLD, general notice listings and vacancies at gazette.education.govt.nz

Scan the QR codes with the camera on your device.

Education Gazette is published for the Ministry of Education by NZME. Educational Media Ltd. PO Box 200, Wellington. ISSN 2815-8415 (Print) ISSN 2815-8423 (Online)

All advertising is subject to advertisers agreeing to NZME. Educational Media’s terms and conditions www.advertising.nzme.co.nz/ terms-conditions-credit-criteria

We welcome your story ideas. Please email a brief (50-100 words) outline to: reporter@edgazette.govt.nz

SUBSCRIPTIONS

eleni.hilder@nzme.co.nz

VIEW US ONLINE Web: gazette.education.govt.nz Instagram: @edgazettenz Youtube: youtube.com/ edgazettenewzealand

VACANCIES NOTICES PLD

Reporter reporter@edgazette.govt.nz

Display & paid advertising Jill Parker 027 212 9277 jill.parker@nzme.co.nz

Vacancies & notices listings Eleni Hilder 04 915 9796 vacancies@edgazette.govt.nz notices@edgazette.govt.nz

The deadline for display advertising to be printed in the 7 February 2023 edition of Education Gazette is 4pm on Friday 20 January 2023.

This publication is produced using FSC® Certified paper from Responsible Sources.

Poipoia

Ngā Rangatira mo āpōpō Nurture our young generation The leaders of our future

Abig focus for this year has been getting our children and young people re-engaged with their learning after a challenging few years of navigating the pandemic. As Covid continues to make its presence felt in our communities, many schools, kura and early learning centres have found innovative ways to keep students and their families connected and engaged.

Take Albany Junior High School for example. The Auckland school noticed the toll the lockdowns were taking on its students: the cancellation of community sports, the closure of local parks and the periods of isolation had led to a lack of peer interaction with inappropriate behaviours beginning to surface and anxiety levels soaring. The school leant into its community and began a gym programme for a group of students, which has helped improve not only attendance levels, but also nutrition habits, positive mindsets, and importantly, relational trust. The student feedback at the end of the article is testament to the programme’s success. Jake’s comment resonated particularly with me: “The programme helped me re-engage with school. It gave me something to look forward to every week. It also helped me release a little bit of anger and made me less stressed.”

Thank you for sharing your stories with us this year. We have enjoyed hearing about your mahi, your successes, your fresh approaches, your reflections, your interactions with your communities and we look forward to hearing and sharing more next year.

For now, we wish you a Meri Kirihimete and season’s greetings from the Gazette team. Enjoy the holiday season with your families and friends, and we’ll see you again in 2023!

Te Tupu staff take students to relational therapy using horses at the organisation Leg Up Trust, which supports young people with behavioural issues and learning difficulties.

“It takes a village to raise a child”, the well-known proverb reminds us. Putting the principle into practice in 21st century New Zealand is another matter – but the final evaluation of the three-year Te Tupu – Managed Moves pilot programme to support at-risk children indicates the network’s initiative succeeds in doing just that.

Community involvement to ensure a child’s wellbeing and growth is at the heart of Te Tupu’s wrap-around service for tamariki, their whānau and community support services.

Under the Napier-based Te Tupu pilot programme, a range of services and agencies collaborated to provide a tailored support system across 22 schools for Year 3–8 children at risk of disengagement from learning or of exclusion.

“This programme is for at-risk and vulnerable children at crisis point in their education,” says Te Tupu governance group chair and Tamatea Intermediate School principal Jo Smith.

Community collaboration

Te Tupu is led by a cross-agency governance group made up of school leaders, social sector agencies and iwi, hapū and whānau representation.

Among organisations involved with the programme are Napier health and social service Te Kupenga Hauora – Ahuriri; iwi service provider Roopu A Iwi Trust; the Ministry of Education; the Hawke’s Bay DHB; child welfare agency Oranga Tamariki; New Zealand Police; Resource Teachers of Learning and Behaviour (RTLB); Te Aho o Te

Kura Pounamu (the correspondence school), and strategic leadership development group, the Springboard Trust.

Te Tupu creates a plan tailored for the student and then provides wrap-around support.

“In other programmes, kids had to meet criteria,” says Jo.

“Our intervention is not about students having to fit into a box. We consider what can be put around them, what those services can be. One-size-fits-all doesn’t work. Every child has a different experience depending on what their needs are.”

Close engagement with whānau is integral to the programme’s success. Whānau get support at the same time as the student.

“Our point of difference is all these services work together and wrap around the child. It’s a great community collaboration.”

Part of the time students have with Te Tupu is preparation for transition back into the school environment. The Te Tupu centre offers the child a chance to breathe and to get all the support systems in place.

“Most stay for about 10 weeks, then they transition

Jo Smith“Our intervention is not about students having to fit into a box. We consider what can be put around them, what those services can be. One-size-fits-all doesn’t work. Every child has a different experience depending on what their needs are.”

back to school. Learnings go on while the children are with Te Tupu, and their learnings are brought back to the school.”

Key findings from an extensive data analysis on outcomes undertaken by the Ministry found there was a significant reduction in the stand-down and suspension rates for Napier City tamariki in Years 1–8, from 2015 to 2021; significant improvement in attendance rates for tamariki who have attended Te Tupu, when comparing their pre-Te Tupu attendance to post-Te Tupu attendance.

“This has changed the game,” says Jo. “I haven’t had to exclude a student since this has been operational. I’m absolutely delighted. We’ve seen the programme change lives. Because it’s a community approach, it’s not just school-based.”

Te Tupu staff were concerned students involved in the programme might be stigmatised, says the programme’s coordinator, Damien Izzard.

“But that couldn’t be further from the truth. Many students approach me and ask how they can come to us. I say, ‘hopefully you don’t have to’.”

Te Tupu creates an environment of aroha, says Damien. “One thing that sets us apart from other initiatives is continued support. A chaotic home environment can be a barrier. Many students live in motels. We’re all about reducing barriers.”

Enhancing mana Kaupapa Māori methodologies are used by Te Tupu staff, with care and education centred around a culturally responsive approach.

One such approach is Te Ara Whakamana: Mana Enhancement model. This is a circular framework that uses the Māori creation story and archetypes to connect individuals to their mana.

The Mana Enhancement behavioural programme teaches students to identify their triggers and to work out strategies for responses in various contexts, says the report.

“We are two-thirds Māori students in our environment,” says Damien.

“The Mana Enhancement programme underpins what we do. If we use Maui as atua (deity) of the week we can work with the curriculum around that.”

Te Tupu also uses Mason Durie’s Te Whare Tapa Whā, a model that refers to a wharenui to illustrate the five dimensions of wellbeing. These are taha tinana (physical health), taha hinengaro (mind), taha whānau (family), taha wairua (the spiritual dimension) and taha whenua (appreciating the land, the beauty of nature around us).

“Whether you’re Māori or Pākehā, lots of programmes

use are easily manipulated or very relevant.”

change in mindset Mindset around old-school disciplinary measures is something Te Tupu governance group is desperately trying to change, says Damien.

“We’re not blaming schools for having to use punitive measures. Schools need support for everyone there. Our community has an alternative. We don’t need just the punitive response.”

we

A

“I’m passionate about the success we’ve had. I look at the value of what we do and the number of children and whānau we see. Rather than spend resources on situations when they’re too far gone, we represent pretty good value.”Damien Izzard As part of Te Tupu’s cycling programme staff and students visit sites of cultural significance to learn the stories and promote their turangawaewae.

The report notes whānau and schools had identified that a timely response, with a fast turnaround, had positive impacts on tamariki.

“Since the child came back to school, they have made remarkable progress,” says one student leader in the report.

“They were referred to Te Tupu for defiance, foul language, and running away. The school had come to a point where none of our strategies were working, and the next step would have been exclusion. Now, you couldn’t tell that student from the others. We are just delighted with the progress they have made.”

The financial cost of the programme is far outweighed by the cost of crime and corrections, courts, and police resources, says Damien.

“Another thing is the opportunity cost. These students, if not in school, are losing opportunities to be around positive experiences such as sport.

“I’m passionate about the success we’ve had. I look at the value of what we do and the number of children and whānau we see. Rather than spend resources on situations when they’re too far gone, we represent pretty good value.”

Seeds for the Te Tupu model were sown at a community meeting in which a police representative said if intervention prevented only one of 40 children from committing a serious crime, the cost of investment in that child would cover the cost of running the programme.

“In 2017, for the first time in a long time, all Napier principals gathered together to talk about challenges in schools,” says Jo. “Some vulnerable learners were not getting adequate support.”

A research report presented in the same year included recommendations across five settings: the attitudes and dispositions of individuals; classrooms; education and training provider group Kāhui Ako settings; whānau and community connections and relationships; and system-level responses.

“In response to this recommendation, a cross-agency governance group was formed and Te Tupu was conceptualised,” says the final evaluation report.

“In 2019, funding of $1.086 million was received to enable the concept to be piloted over a three-year period and its success evaluated.”

The evaluations were to explore the effectiveness of Te Tupu as a response to tamariki at risk of disengagement from education.

“We were told to go ahead with the prototype,” says Jo. “Part of the funding included a hefty amount for evaluations but we’re happy. The evaluation will be a consideration in next year’s budget.”

A school in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland has trialled a robust gym programme for a group of physically active ākonga to prioritise wellbeing and re-engage them in learning.

Deputy principal at Albany Junior High School (AJHS) Demian Shaver and teacher Jamie Gresham have selected a diverse group of about 20 students to take part in a programme designed to re-engage them with school.

“We discussed the opportunity with the students and told them it was something new, innovative and how lucky they were to get this chance,” explains Demian.

“After a time, some parents also came along to watch the sessions, hearing that their students were enjoying it and engaging. Having some common ground like this can be game changing for these students and parents alike,” he adds.

The AJHS team explains how the programme came about and what has made it successful.

Demian Shaw, a deputy

In 2020 after our first lockdown, our students started returning to Albany Junior High School.

Like all of Aotearoa, we saw change: signs were placed outside local parks for children saying “closed”, local community backboards and rims were removed so people couldn’t play basketball, local community sport was cancelled. All communication came through a screen, there was little to no new human interactions.

The change was very evident from the start: once loud bustling atriums at school were quiet, students were nervous around each other. Parents were nervous about their children coming to school for the first time since the outbreak and anxiety was at an all-time high.

With anxiety and stress, came behavioural cracks. Students took part in risky activities, reacted badly or extremely to occurrences which were once laughed at, and brought inappropriate behaviours more frequently to school. It was as if students were in a constant state of high emotion, spilling over at each ripple.

One group of students whom we believed suffered the most, were the physically active learners. Without sport, students who may never be on a school’s radar, started showing signs of being at risk behaviourally.

Coming out of lockdown, I was fortunate to get a

chance to try out a new gym, 808, where the workouts push you out of your comfort zone and may seem unachievable, but when you are engaged in them, time and the noise in the head disappears, endorphins are released and at the end of each class you feel successful.

At one school meeting Gemma Woods (the SENCo at AJHS) and I looked at each other and said what about 808? Going back and forth, discussing positives and negatives we all agreed: Let’s do it!

Gemma Woods, SENCo

We started with 20 students coming from a range of ethnicities, attendance rates and learning concerns. Their school attendance rates varied from 52 percent to 93 percent.

These were the students who we repeatedly discussed in guidance meetings, at staff briefings and there were shared concerns for day-to-day interactions. These were the students that you always thought “there’s got to be another way to engage and support them”.

In January 2021 I had an opportunity to create a programme to help motivate a group of students from Albany Junior High School. The programme would be based on helping them achieve better results and higher attendance at school, along with building their selfbelief and teamwork skills.

During that first session I realised that they didn’t know what they were fully capable of. We started off with simple and basic movements: the workout was designed to push them, so they felt slightly uncomfortable. Throughout this workout I saw a lot of the students giving up. Their efforts dropped quickly, and it took a lot of motivation to keep them going.

It was also noticeable that they were only focused on what they were doing and no one else. One part of the workout required them to stay in a squat hold and if anyone stood up everyone had to start again. We had to start again a few times as there was no support or teamwork.

“I’ve seen such a difference in students throughout this whole experience. It started with students who barely knew each other, just working quietly, individually on their tasks. Now, there is a cohesion and a shared understanding that to get the mahi done, they must work together.”

Jamie Gresham

Fast forward to today and the difference is massive. All the students have realised that working together and pushing each other helps them get through any workout.

They also have a much better understanding of what they are capable of and what they can achieve. Every workout gets done with no complaints and with 100 percent effort.

It really has been amazing to see the growth of these students and hear they are doing so much better in their schooling. You can see a boost in their confidence when they come in. Their respect for the gym, each other and staff members including myself as their coach is now visible and it’s fair to say that these students have created their own community within the gym.

From this experience I have learned that this programme isn’t just about what happens at the gym, it’s also about what happens on the way to the gym. There are powerful discussions: we talk about personal hobbies, weekend plans and their long-term ambitions outside of school.

Running this programme on a Friday lent itself to easy conversation starters like “what are you doing this weekend?” and, “how has your week been?” I have found these simple questions open the flood gates, and before we know it, we have made it to our destination with a slightly tighter bond than the week before.

I’ve seen such a difference in students throughout this whole experience. It started with students who barely knew each other, just working quietly, individually on their tasks. Now, there is a cohesion and a shared understanding that to get the mahi done, they must work together.

Demian says that the programme has had a significant impact in many areas including improved attendance, better nutrition habits, positive mindsets and collaboration in the classroom.

“Firstly, it brought relational trust to everyone. When not at 808, students felt more comfortable coming to a staff member during school time and asking for help or discussing personal circumstances.

“As a deputy principal, that is enormous when it comes to dealing with pastoral issues. Tough workouts led to students having to learn more about nutrition. Some of the students started eating better, drinking more water and joining local gyms. This started to create positive mind-sets and friendly competition with one another in a collaborative way.

“The proud moments though, are when you start to see the support happening between one another when they are struggling. Students learning to support one another at the gym was one thing, but seeing them supporting each other in the school setting was remarkable.

“We saw some drastic changes in students, where they made completely different decisions than they otherwise would have made a few months earlier,” he concludes.

How did you feel when returning to school after lockdown, and do you know why you felt like this?

» It felt really good returning to school after Covid. I found online learning hard, and it was annoying for me. The main reason I looked forward to coming back to school was to see my friends.

» To be honest, it felt crazy to come back to school at first. It was great to see all of my friends.

» When I came back to school, I was really nervous. It took some time for me to get my confidence again. I don’t know why I felt this way.

» As soon as I arrived back at school, I felt cramped up. I was full of energy and online learning was really hard and frustrating for me.

How did the gym programme help you to re-engage with school?

» The programme helped me like school again. It was something I could look forward to. It always makes me want to do my best. It helps me focus and try harder. With me having ADHD, it helps me release so much energy. I enjoy doing it with my teachers too! It makes me want to work way harder.

» It has helped me lots. Whenever I do it, I feel calm and happy. It is such a good distraction for me and it takes my mind off other things.

»

School for me is very difficult. There are so many expectations that people have for us and there always seems to be drama around. The programme was like a confidence boost for me. It started helping me with my anger. I could just start to let go and suddenly there would be nothing on my mind.

» The programme helped me re-engage with school. It gave me something to look forward to every week. It also helped me release a little bit of anger and made me less stressed. Since the programme I have now joined a gym and work out in the mornings as well. This has really helped me.

» I like school more for many reasons. Working out has helped me make friends, and I have better relationships with my teachers. It has also really helped me with my emotions. I forget about being angry or sad when I am at the gym. It just seems to make me forget about those things.

» I love school but at times there is just too much drama. The programme just brings happiness without any drama. It is my happy place.

» It has helped me with focus. It taught me that I could trust teachers and be myself, and that people would help me.

» I enjoy school more. It has really helped my mental wellbeing. It seems to make me more organised in my school work and I know I have some people, including teachers, I can trust.

Year 9 student“The 808 programme helped me re-engage with school. It gave me something to look forward to every week. It also helped me release a little bit of anger and made me less stressed. This has really helped me.”

Matt Bateman, principal of Burnside Primary School, and Lynda Stuart, principal of May Road School, both understand the importance of building a resilient culture in schools.

Providing staff with the resources they need is vital, says Lynda (middle).

Principal Matt Bateman says the key to building resilience is having shared values that underpin the vision and direction of a school so that everyone has a consistent and positive experience.

“All of our communications sound the same and make people feel the same. How we greet, how we connect, how we work together, how we celebrate children. They’re all in the context of those values,” he says.

Matt likens it to being part of a family, where everyone is respected and trusts one another. He says having a united family that can convey genuinely positive communication is important as the community can be quick to pick up on points of friction within a school.

“We need to be what we say we are, and that can take a while to get right,” he says. “It might take a few years to build that 100 percent buy in from everybody. Then once that is built, you need to maintain it.”

Setting clear ground rules can provide a climate of safety for those within the school.

“This does not mean that there are no difficult discussions, but it does make it easier when such discussions are required,” Matt comments.

Matt says that, as a principal, one of the ways to ensure a family-like relationship is maintained is through having regular contact.

“I walk around the school in the morning and unlock all the classrooms. We have got a caretaker and I could ask him to do that, but I’d much rather walk through all the spaces... see what’s going on, be able to celebrate the good work that might be up on the classroom wall or on a desk with the teacher, and just have a bit of a chat.”

By doing this Matt can keep up with how his staff are going and share positive news with other members of school – for example telling them it is someone’s birthday. It is also a time to talk about things that may be creating stress for staff members.

“We’ve got a few staff who have children sitting NCEA. I know that they’ll be coming to work a little bit stressed about that. You can have a conversation around how their child is going, what have they got coming up. So, you can sit alongside them and share the stress.

“That small conversation at the start of the day can make them feel that you understand them a little bit. That you understand they’ve got a life outside school that you value, and that other people value, and they can feel supported by the school.”

Matt also creates other opportunities to show support. If staff are going to do something that is outside of their current comfort zone, he will ensure they have the necessary supports to guide them through. This can range from going with staff members who are attending a tangi for the first time to helping teachers involved in their French bilingual unit interact with the French community. Other support can come from positive reinforcement and recognition in staff meetings.

Assemblies that show appreciation of how children are progressing can be a way to build support networks. Matt says they make sure that family and the community know well in advance if a child or their class is going to be celebrated so that they might be able to attend.

Matt Bateman“That small conversation at the start of the day can make them feel that you understand them a little bit. That you understand they’ve got a life outside school that you value, and that other people value, and they can feel supported by the school.”

“Those sorts of celebrations really help the relationship between the classroom teacher, the parent group, and the wider community as well. So, from a point of view of trying to build networks of support and resilience, they are important.”

The ability to create strength through connectedness has been recognised. The name that has been gifted to the school by mana whenua is Tuia, which means to weave together.

“One of the things that mana whenua felt that our school does reasonably well is to weave people, communities, together. By doing that you obviously strengthen the cloth, strengthen the fabric, strengthen the community. If everyone’s aligned, everyone’s supporting each other, we are strong.”

Matt knows that building and maintaining a family environment for the school staff requires good leadership that can also model resilience. For himself, he gains strength from the achievements of his staff but also acknowledges the importance of his family to help him remain positive.

“If I’ve got a bit of an issue that I need some help with, I don’t keep it to myself. I generally am quite happy to share that with other people and have them talk it through and help me so that they can become a part of helping me as well.”

Lynda Stuart understands the stress schools can face. Her school is in a growth process with an increase from 200 students to 1,000 over the next few years. A challenge with this growth, will be continuing with their personalised approach.

“So, one of our challenges is to continue with this and the importance of the school being at the heart of the community. Knowing our families and knowing each and every child really well,” explains Lynda.

The school appreciates being at the heart of a diverse community. May Road School is one of the only schools in New Zealand to be selected as a guardian of a midden, which is a mass that may contain shells, bones, artefacts, charcoal and sometimes oven stones. The midden was gifted to the school following impacts from a housing development.

“We did a pōwhiri into the school as it was very important and significant,” says Lynda. “I don’t think having a midden being gifted has ever happened before in a school.”

According to Lynda schools have always been a space where teachers will reach out to families because they know it can make a difference to issues such as attendance and engagement. However, she feels that the role of the school as the hub of the community has increased during Covid as many people saw schools as go-to place for support and information.

This role is important but if schools are stretched for resources, it can make this process of building and supporting these essential trusting relationships harder, which is stressful for staff wanting to do their best.

“I don’t meet any teachers, any principals, any support staff who didn’t come into their role in order to make the best difference that they possibly could for children, and at the end of the day we know that we’ve got to make those strong relationships to really make a difference for the children.”

To make this difference, many are working very long hours. The Principal Health and Wellbeing Survey, which monitors the health and safety of principals, found that 72 percent of principals work more than 50 hours a week and 16 percent work more than 60 hours a week.

“Two key areas that people are finding hard, which come through really strongly, is the sheer quantity of work and the lack of time to really focus on teaching and learning.”

Time is the major resource that Lynda wants to see being improved to promote resilience in schools. This means having a system that provides schools with the right amount of time to implement change, complete required paperwork and compliances, and have a good work to home balance.

“A resilient school is where we have our people who support our children, whether they be our teachers or our teacher aides or our principal, thriving. Then, I think our children thrive too. I also think that it is where people have the time and the space to do the job that they so desperately want to do.”

“I don’t meet any teachers, any principals, any support staff who didn’t come into their role in order to make the best difference that they possibly could for children.”

Lynda StuartTop: Celebrating cultural diversity creates strength. Bottom: Gatherings are an opportunity to create unity and engagement.

Sylvie and Issy are members of the Rawhiti Kakahu Komiti which has created the contemporary korowai in the background for next year’s Manu Kura Māori prefects at Wellington East.

Sylvie and Issy are members of the Rawhiti Kakahu Komiti which has created the contemporary korowai in the background for next year’s Manu Kura Māori prefects at Wellington East.

Three Wellington schools have combined to learn and share knowledge and skills with an inquiry into how Māori toi in the technology curriculum can enable students, staff and the community to gain lived experiences of mātauranga Māori.

This year, kaiako from Wellington East Girls’ College (WEGC), Hutt Valley High School (HVHS) and Wellington Girls’ College (WGC) have been learning how to create contemporary korowai (cloaks) including weaving taniko (cloak borders). They will also be learning how to craft taonga puoro (traditional instruments).

Nan Walden (Te-Aitanga-a-Mahaaki) is design and evaluation lead of technology at WEGC and Grace Wright is a deputy principal at HVHS. They both say that with the te ao Māori concept of gifting and reciprocity of knowledge, the project has provided opportunities for teachers to connect and explore without fear, which is particularly exciting leading up to the new achievement standards change for Year 11 in 2023.

“The New Zealand Curriculum is changing and with it all the NCEA standards. For everyone there’s a mātauranga Māori portion which they have to include. That’s exciting but I also know that for a lot of people that’s really nerve-racking because there’s a real fear that people don’t know how to tap into expertise to upskill themselves to then teach.

“What’s quite exciting for us is if we each go off and learn something and then share it with each other, you end up with lots of things that you can share,” explains Grace.

“Yes, that’s te ao Māori: the reciprocation of knowledge and sustainability. If you were going to cut down some harakeke for some weaving material, then you would go back and plant another and say a karakia. In the new achievement standards coming out, everything is to do with sustainability and te ao Māori world is all about sustainability, so that marries so nicely,” adds Nan.

In term 2, Wellington East hosted about 10 teachers from Hutt Valley High School and Wellington Girls’ College for a full day workshop to learn about and engage in the tikanga and construction of contemporary korowai and how it can be implemented in their schools.

“The teachers from all three schools can now

teach the skills – they also know the tikanga, karakia, mihimihi, pepeha, waiata that goes with it; then where to order your feathers, where to buy taniko band, and the linings you should use,” says Nan.

A more recent workshop offered kaiako the opportunity to learn about the tikanga and implementation of taniko in the classroom.

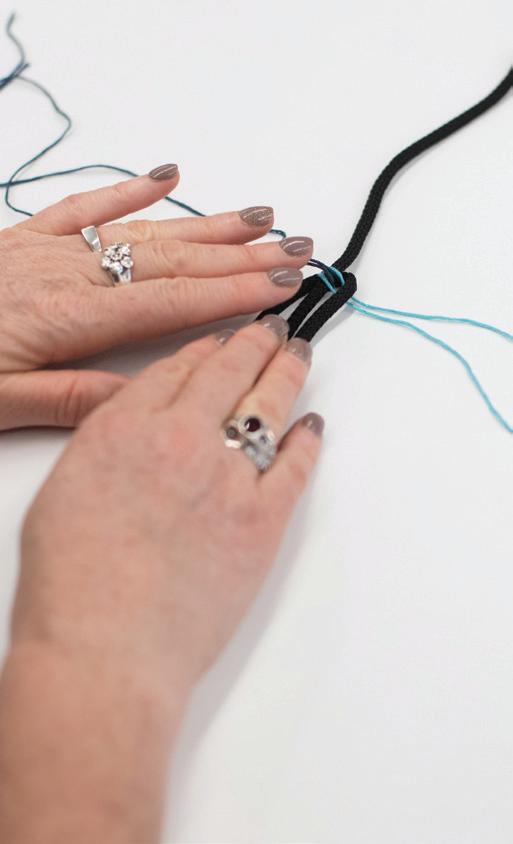

“We did the taniko weaving workshop and we all sat around the table together and we had karakia and we said pepeha, then we learned how to weave together. As we were weaving, we were listening to music and having a good kōrero – that’s what would have happened back in history in a Māori weaving circle. That was a lived experience of mātauranga Māori for those women in that space and it showed whanaungatanga,” says Nan.

The group is also showing whanaungatanga to Whaearua Ross (Ngāti Hauā) , a second-year teacher who is the head of te reo Māori at Wellington Girls’ College and is part of the kaupapa.

“We are here to support her in whatever she needs to manage her teacher load. A lot of demands are made on Māori teachers,” says Nan.

“Wellington Girls’ College is not as involved in the sharing of knowledge yet, but that will come with time, that’s the idea of growing staff competency,” adds Grace.

The first part of the kaupapa is to grow the teachers and then grow the students.

“We’ve done contemporary korowai, we’ve looked at taniko and we’re going to be looking at some taonga puoro. The contemporary korowai was our start but that space is getting bigger as we learn more arts ourselves and share with each other,” says Grace.

“Our vision is to upskill the teachers so that every school can offer everything. If you have it that way and everybody takes charge of it, then you’re not dependant on a single person and you’re not making everything single cell – the teaching is broader, so there are more teachers able to teach it,” she says.

Miranda Hurley, technology teacher at WEGC was

able to learn about contemporary korowai alongside a student.

“It allowed me to feel more confident in being able to implement some of these skills in my Year 10 class in fashion technology and also help other teachers within the workshop.

“We were doing a unit about what makes a hero. A student wanted to make a contemporary korowai for her mother and I was able to learn alongside her and help to guide her while sharing the journey of making my own contemporary korowai.

“This process has meant a lot to me and my student and by the end I could see that she felt confident and supported in being able to incorporate tikanga into her work. This has also continued to grow in her next project which has been very rewarding to see. I hope to implement this more and more in the future,” says Miranda.

Citizens of Aotearoa Nan and Grace believe that teaching and sharing mātauranga Māori is important for all teachers and learners in Aotearoa.

“This year we have developed Te Auaha Hangarau Kakahu Komiti – a group of Year 10 creative technology students who care for and maintain the kapa haka kakahu (clothing) and construct contemporary korowai for gifting, for example to Māori prefects, or teachers who are leaving,” says Nan.

She says that the narrative is not just about Māori or Pākehā, but about being a citizen of Aotearoa.

For example, a group of girls constructed a beautiful red velvet flowing dress and created hijab to go with it as part of their culture.

“For them to be able to see me embracing my culture and disseminating it to my Māori students, then it

“Our vision is to upskill the teachers so that every school can offer everything. If you have it that way and everybody takes charge of it, then you’re not dependant on a single person and you’re not making everything single cell – the teaching is broader, so there are more teachers able to teach it.”Grace Wright A taniko workshop was held at Wellington East for members of HETTANZ (Home Economics and Technology Teachers’ Association of New Zealand) including Rowan Heap and Emma Howell from Wellington High School, pictured with Nan Walden. Making taniko bands.

becomes OK to be whoever you want to be. That identity is crucial.

“Year 12 Creative Technology student, Brooke, is Pākehā but embraces te reo and contemporary korowai construction with karakia and pepeha. She has just finished a contemporary korowai for her father who’s Scottish. She had her clan tartan printed and made, and then she lined the contemporary korowai with that and the band at the top is not taniko – it’s the family tartan. She’s also a NCEA Level 2 Te Reo Māori student – so that incorporation of cultures reiterates my point of being an Aotearoa citizen,” says Nan.

Taonga puoro Grace comes to the project from a different starting point. She teaches creative arts at HVHS’s marae, working out of field Māori standards and incorporating music and technology in the creation of taonga puoro.

“It’s quite a different space from being in a technology room and the process of how you approach the work is quite different. It’s far more from a tikanga basis and a learning of a craft for the culture first rather than the technology,” she says.

Bottom

Right:

“I started from the music department and over the past few years I’ve had students saying they want to learn more – their curiosity has been piqued. They’re coming from a place of sound first rather than in terms of culture,” says Grace.

“But they embrace everything as they go. Their whole view in terms of seeing music as a greater cultural experience changed and opened out beyond just playing into crafting and making. In terms of their kaupapa they’ve gone from making their own instruments to playing and then being able to absorb it into different genres of music. They might have a beautiful piece with guitar and voice and then they can bring in a kōauau (flute) over the top!”

At the end of term 4, teachers from WEGC and WGC will travel to HVHS and embark on a learning journey with Grace in tikanga and traditional instruments – porotiti or purerehua.

“I’ll take them through what I do with the students and they’ll make a relatively straightforward piece. Just a taster, but to have a slightly different approach in terms of working out of the marae. It’s not just about teaching to the technical skills; you could make some of those instruments very quickly with the gear over in the technology block, but how can a student do that at home?

“We might use concrete as sandpaper, so they understand that their resources are all around them and no matter what they’ve got, they can make things. If it’s in a technology room, that limits it to technology teachers, but I want it to be open to any teacher, or whānau to get involved,” says Grace.

The inquiry process the three schools have undertaken has put the focus on the mahi and learning.

“Usually, you would take an achievement standard and apply it to learning, but for this we take that learning and apply whatever achievement standard goes to it. So, it’s more about the learning than how many credits something is worth,” says Nan.

“With the new achievement standards, as teachers explore what they need to in their curriculum areas for mātauranga Māori, it should hopefully change everything so that it becomes about the work and the learning, and the assessments become the by-product. I feel that this might be a place where teachers really experience that because they have to provide authentic learning contexts,” says Grace.

Nan would like to acknowledge Eva Mokalei, kapa haka costume designer and Rewhia King, whānau liaison kaiawhina at WEGC for supporting her on her journey.

Manawatū College has been on a journey of self-reflection and internal evaluation reviewing their practice over the last two years – as part of this they have developed an alternative approach to re-engaging students with their learning in mainstream education.

Manawatū College is located in Foxton; it is a smaller college with 285 students. Principal Matthew Fraser sees the size of the school as an advantage.

“It’s great to be able to work in a small school. I think there are many opportunities with working in a small environment. Connections with people matter, they are stronger, and it is more personal.”

The college has been on a journey of continuous improvement all of which has taken place in collaboration with students, parents, whānau, staff, iwi and hapū.

“A key focus for us at Manawatū College is working to ensure that all students get the best education they can at our school. Fundamental to this work is going through a process of review and self-reflection which are essential parts of the improvement process,” says Matthew.

The school realised the need to address student engagement, particularly for junior students. In March 2022, a group of 10 to 15 students in Years 9 and 10 were identified as having very high pastoral care needs that required significant intervention to support genuine re-engagement with learning.

The school had a number of strategies in place to assist students such as a strong pastoral care system supported by academic coaches. They also used the advantage of having a small community to get to know students and their families on a personal level to help design learning programmes that fitted around individual needs and aspirations. However, they felt some students could benefit from more support to experience success with learning.

“As a school we do many things to support students to succeed with their learning, but we know that for some students that just isn’t enough. It doesn’t quite meet that need. So, REACH came from trying to find an alternative way to engage those students with learning.”

Matthew is quick to point out that REACH is not alternative education, instead it’s about taking an

alternative approach to engaging those students with learning.

The programme name, REACH, is drawn from the school motto, “Beyond Personal Best,” in the sense that the ultimate goal is to support students to ‘reach’ beyond their personal best in all aspects of college life.

To help those in the programme reach beyond their personal best, the team looked at student profiles to work out the ideal approach. Most of the students engaged best when learning was practical, hands on and ideally working alongside a mentor who can inspire them.

The structure of the programme was flexible at the start to allow it to grow according to the needs of students. Matthew describes it as being organic, where there was a goal and direction, but the means to achieve it was not set in stone as this was to be developed over time, informed by learning along the way.

“What guided the approach, was taking our school values and what we already knew about the students, and then focusing on connections and relationships, really getting to know them on a deeper level, and to provide learning experiences in a way they may not have had in the classroom.”

It was decided to use a group approach to enable the students to connect with each other, as well as with the school. The key to its success would be finding the right people to lead and mentor the group.

“We selected people who we knew had good connections to our school community, and one of these was Anthony Woon.He was someone who I knew had strengths in building meaningful relationships with people from all walks of life, and I thought he would be a real asset to the programme.”

Matthew Fraser“A key focus for us at Manawatū College is working to ensure that all students get the best education they can at our school. Fundamental to this work is going through a process of review and self-reflection which are essential parts of the improvement process.”

Anthony “Coach” Woon became the project coordinator and was the person who worked the closest with students.

The students would spend the first and last period in group sessions with Coach, who would also check in with them while they were in class to make sure they were supported.

The check-in session was a time for students to work on preparing for the day and goal setting while eating breakfast together. The check-out session allowed for time to reflect on the day and what they had achieved.

Students would spend the rest of their time in class, except for Wednesday which was an ‘off-site day’. This day was dedicated to the students working on a group project together. Initially this day was planned for work experience at local businesses, but it was felt that working towards achieving a group project would be more beneficial.

“Originally, we sort of thought they could have a day where they go off and they might go to the local mechanics and learn how to build a go-kart or some practical handson projects.

“As we got into the programme, we found more value in providing experiences where they were in the community, down at the beach or other local areas of significance, working as a team.”

One group project was putting on a hāngī for the school and families. The first off-site project day saw the students going to Foxton beach to collect wood that could be used. The day allowed the students to understand local history but also to make their first steps as a group, working on problem-solving and leadership.

According to Matthew, Coach gave reassurance to them as they were not confident in this space (making decisions and figuring out how to complete the task on their own).

The relationships between the group and Coach grew over the weeks, which produced some noticeable changes in attendance. In terms of lateness, there was a 75–96 percent decrease for almost all students. When it came to truancy, all students had reduced truancy and some students had an 82–94 percent decrease, compared to data from term 1.

Motivated by these results the school committed to continuing the programme but with some alterations. One of these was the inclusion of additional students to the group, both male and female.

“We didn’t realise how much of a culture we had developed with that first group until the next one came in. As the next few students joined you could see the first students, without being asked, reminding the new people about the expectations around how the group operates.

“When there is a small group, the process of creating culture can be a lot quicker than with a larger group. The added benefit for future students to the programme means they are joining an established culture of success.”

Other modifications over the year have included reducing the out of class time to help the students transition back to full-time class attendance. They were still able to connect with the group and with Coach. The full day off-site continues and is progressing to developing work placements as well as community interaction.

Matthew is happy to speak with other schools who may be thinking of developing a similar programme.

Much of the success of REACH was due to the relationship that Coach was able to establish with the students.

Some of their feedback includes:

» “He understands where we are coming from and our point of view.”

» “If we are playing up, he puts us in line by keeping calm. He never gets mad, he talks.”

» “He is like our dad at school.”

» “He can sit there and can just look at you and know how your brain works.”

When asked for his advice when it comes to the qualities required of a person like Coach, Matthew says, “You need an approach that is based on the principles of restorative practice and school values, which really boils down to respect, listening and being non-judgemental.

“If there’s an issue, separating the person from the issue. I think sometimes it’s easy when you’re dealing with challenging situations to forget to see the person rather than the issue.

“You need patience. In this programme we’re trying something new and trying an alternative way of doing things and we won’t necessarily change people overnight because that is not what we’re trying to do. We wanted to get to the space where we have deep connections and relationships with those students, supported by somebody who they trust.”

“He was someone who I knew had strengths in building meaningful relationships with people from all walks of life and I thought he would be a real asset to the programme.”

Matthew FraserAbove: Students engaged in a brief and de-brief with Coach during the day Below: The final result of the project was a beautiful meal provided by the students.

With drownings last year being the worst in a decade (90 people drowned), water safety organisations and the Ministry of Education are hoping that a raft of resources and support for teachers will help to address this deadly statistic.

Drowning Prevention Auckland (DPA) offers professional learning and development (PLD) which focuses on empowering teachers to have the confidence and knowledge to teach aquatic education that will help young Kiwis survive in open water environments.

Research commissioned by Water Safety New Zealand in 2017 showed that enhanced learning comes from authentic learning environments, says Ants Lowe, general manager operations, DPA.

“Dr Chris Button, Otago University, did some research, Teaching Foundation Aquatic Skills in Open Water Environments, and concluded what we all knew, that the real learning for students happens in open water settings,” he says.

Lynley Stewart is team leader education for DPA and says that while tamariki and rangatahi may learn water competence in the classroom or pool, the skills and knowledge don’t always transfer well into an open water environment.

“Current evidence recommends 15 water competencies be taught to prevent drowning. The water competencies include all three domains of learning – physical skills, cognitive skills, and attitudes and behaviours. The experts tell us that unless all three are working together, the learning is less effective,” she explains.

While many water safety programmes focus on physical aquatic skills, the 15 evidence-based water competencies seek to integrate and incorporate the three domains.

“Cognitive skills are ones that focus on knowledge and understanding, so that if you’re going to a particular environment, what should you be aware of? Also, being able to identify the risks and dangers and then being able to work through a process so you can mitigate and manage them and make some really sound decisions.

“One of the at-risk groups for drowning are adolescents and young adults. Challenging them to think about what they do and how they could manage that more safely and keep themselves and their mates safe is important. There’s been a bit of a turnaround there. Most of our drownings are now happening in the older adult group,” she says.

Drowning Prevention Auckland supports teachers throughout Aotearoa with a layered approach to inschool PLD in the classroom and swimming pool to open water environments. PLD is also provided for teachers from multiple schools.

Recently a day-long programme was developed in collaboration with Tarawera High School with critical discussion on current good practice in aquatic education and included learning experiences at a river and a lake in the Eastern Bay of Plenty.

“It was an effective collaboration working with the school and local experts so that when we were in the open water we had a strong understanding of these environments, which are used by a lot of the schools for their open water activities. The Bay of Plenty has a lot of inland water ways and so it’s giving teachers the skills and knowledge around those environments,” says Ants.

The PLD also focused on the wider picture of aquatic education encompassing learning in outdoor environments, with an emphasis on foundation learning around the 15 water competencies that should happen before students go into the outdoors.

The group visited the nearby Tarawera River, where participants were actively engaged in site-specific hazard identification and risk management, with the opportunity to discuss potential learning opportunities for students.

“We unpacked that as a potential learning area with students. It was getting them to look at the river and think what are the hazards, dangers and risks in an area like this? Then throwing in the question – who would you use this with? It’s getting them to think through that whole process of decision-making,” says Lynley.

The teachers then went to Lake Rotoiti and, wearing wetsuits to combat the chilly October water temperatures, took part in a couple of scenarios in the water, one of which focused on “free swim time at a school camp” with an emphasis on roles and responsibilities and supervision strategies. They also planned and carried out an emergency response to a situation.

Lynley Stewart“Current evidence recommends 15 water competencies be taught to prevent drowning. The water competencies include all three domains of learning – physical skills, cognitive skills, and attitudes and behaviours. The experts tell us that unless all three are working together, the learning is less effective.”

Learning about planning and preparation are key ways to empower teachers to deliver aquatic education in the open water, says Ants.

“Teachers do an amazing job but it’s a large responsibility for them. It’s about knowing how to have a really great time and also being prepared if things go wrong. That’s looking at the operational planning and making sure that they are prepared for the event.

“How do you supervise all the kids at the same time? How do you ensure that you’re able to intervene but also enable them to learn about, and enjoy, these amazing waterways and know what to do in an emergency response?

“We teach them about a bystander rescue. We advocate not going into the water to save someone because statistics are quite clear that rescuers do get into trouble and may not survive when they try to intervene. Instead we focus on the use of buoyancy aids like putting a chilly bin into the water to rescue someone,” explains Ants.

Ants LoweLynley believes that while many water safety programmes are delivered by outside providers, it’s important that teachers also lead the learning in aquatic education.

“I feel quite strongly about this, in that anything we’re trying to achieve in a learning environment needs to be sustainable. If providers are working with their children and that’s the end of it, it’s not ongoing.”

She says that teachers combining their pedagogical knowledge with the content knowledge of an outside provider allows for effective water safety education.

“For example, in aquatics, it’s ‘what do my students need to learn to be water competent?’ A key input is helping teachers to become familiar with the resources that are available and standing alongside them in the classroom, at the pool and open water environments and supporting them to provide those learning opportunities to students,” she says.

“We evaluate teachers’ perceptions of doing a programme prior to going into the water and afterwards and there’s quite a significant shift, highlighting the fact that people do perceive that they have greater skills and ability than they actually do,” says Ants.

“Also, there’s a strong reliance on the belief that you’ll be OK if you can swim – how do we turn the dial regarding that? Because swimming is a wonderful skill, but there are many other aspects to keeping people safe,” he concludes.

“... there’s a strong reliance on the belief that you’ll be OK if you can swim – how do we turn the dial regarding that? Because swimming is a wonderful skill, but there are many other aspects to keeping people safe.”Read more about water safety education in previous Education Gazette article, Staying afloat with water safety education. The Water Skills for Life Beach programme saw the Gazette’s photographer check out the action in a programme run by Whenua Iti at Kaiteriteri Beach in Nelson earlier in the year.

» The 15 water competencies Water Competencies | Drowning Prevention Auckland (dpanz.org.nz).

» Ministry of Education Water Safety poster https://assets.education.govt.nz/public/Documents/ School/Health-and-safety/Building-water-safetyskills-and-knowledge-Water-Safety-Poster.pdf.

» E-Learning Home | Drowning Prevention Auckland (dpanz.org.nz).

» (PDF) From Swimming Skill to Water Competence: Towards a More Inclusive Drowning Prevention Future (researchgate.net).

» SCHOOLS, Water Safety New Zealand.

» Resources for kaiako and kura RAUEMI RESOURCES, Kia Maanu Kia Ora (kmko.nz).

» Dr Chris Button’s research, Teaching Foundation Aquatic Skills in Open Water Environments.

» Education Outdoors New Zealand online learning modules. Read this story online to link to these resources.

Rangatahi worked diligently alongside practitioners from Te Rākau Theatre Marae, Aotearoa’s longest surviving independent Māori theatre company.

MĀORI HISTORIES

MĀORI HISTORIES

Te Rākau Theatre Marae is working with the Ōtaki community and Ōtaki College to reinvigorate teachings on Māori history, bringing the past into the future in their production, The Battalion.

Actors and students from Ōtaki, Porirua and Te Awa Kairangi ki Tai transported audiences back in time with performances of The Battalion, an original production by Helen Pearse-Otene.

The Battalion tells the story of rangatahi going off to war in the 1940s. Students involved in the project felt a connection to their characters, as the struggles of being a teenager are timeless and relevant, no matter the context.

For four months rangatahi worked diligently alongside Jim Moriarty and practitioners from Te Rākau Theatre Marae, Aotearoa’s longest surviving independent Māori theatre company. Then in October the budding young actors delivered five breathtaking performances of the play, showcasing the abundance of talent in the Kāpiti region.

Te Rākau’s involvement with Ōtaki College and community has been a work in progress for many years and finally came to fruition in June 2022. A financial boost from Creative New Zealand allowed the school to engage in one of the theatre company’s community focused arts programmes, says drama kaiako, Tamsin Dashfield-Speight.

“Everyone seems to recognise what a unique opportunity it is to work with Jim and Te Rākau. It’s such a unique experience and it’s definitely likely they’re going to remember this for the rest of their lives.”

Te Rākau were also recipients of funding from Creative New Zealand, being granted $1.22 million from the Toi Uru Kahikatea long term funding programme which will be distributed over the next three years.

Community engagement was an important value of both Te Rākau and the college for the roll out of

Top left: Performers check in to see where everyone’s at and how people are feeling in porowhita talking circles.

Bottom left: Rangatahi value the sense of belonging and whanaungatanga the experience has given them.

Right: Performers from all year groups and from outside the college banded together to deliver the powerful performance.

the programme. They hoped to bring Aotearoa history, whakapapa, connections, and stories into Te Ao Marama – the world of light, through creative mediums and processes.

While the programme was largely undertaken and developed on Ōtaki College campus, participation was not exclusive to the college students. Students outside of Ōtaki were encouraged to join the group and immerse themselves in both the world of theatre and Māori culture, says Tamsin.

“We opened it up to Year 9s and found that quite a few of them were really keen, and that increased the numbers. We had one or two students who just left and are coming back and doing it, and that’s really awesome. Because the whole point of this was, you know, bringing it into the community.”

Even prior to the performances, the subject matter in The Battalion prompted conversation between rangatahi and whānau as they sought to learn more about their whakapapa and Aotearoa’s rich Māori history.

“I just feel privileged to meet this type of energy wherever I go,” says Jim.

Many of the students’ first exposure to the Māori Battalion came in the production rehearsals and meetings with Te Rākau. Their genuine interest in this history pushed them to do their own research, both through kōrero with whānau and on the internet. This meant the eventual performances were articulately conveyed and immersive as they came from a wealth of knowledge and understanding.

Tamsin witnessed the students’ dedication to the piece as she watched them rehearse during their morning and lunch breaks every day prior to the opening night.

“They’re taking a lot of pride in their work. I think that they’re realising how demanding it is. They’ve been doing physical training, they did some military drills. One of the students here, their dad had been in the Military Police, so he came in and ran some drills. Like it’s a whole experience.

“Everyone seems to recognise what a unique opportunity it is to work with Jim and Te Rākau. It’s such a unique experience and it’s definitely likely they’re going to remember this for the rest of their lives.”

Tamsin Dashfield-Speight

“Jim is their motivational leader and he’s got them motivated. They see his vision too and they want to make it as good as it can be.”

Before the audience filed in, Jim gathered the performers to get them in the zone. He says he was surprised so many stuck around and made it through to the opening night.

“My job is to guide, and to try and bring everybody together at the same required rate of readiness. I can become a little bit unpopular, but everybody understands that... I think it’s the nature of the beast, but we do that together anyway.”

They rehearsed a few dozen times and memorised their lines to each full stop, but naturally nerves were high on the opening night. To get over this the actors lost themselves in the timelines and settings. Their passionate monologues and presence struck a careful balance between engagement and full immersion. The audience weren’t passive spectators, but rather silent characters in the world of The Battalion Ōtaki College staff, whānau members, and Te Rākau

have seen the participants grow in confidence, skill and self-awareness. Jim doesn’t solely credit himself for the developments, and instead takes pride in the rangatahi themselves and the holistic kaupapa Māori values that underpin the theatre’s programme.

Rather than a traditional elevated stage with a modifiable backdrop, creative directors opted for a traverse stage, which mimicked a fashion catwalk. The audience were split in rows parallel to each other and the performance took place in the middle of this. The set up could have proved difficult for the young actors but they rose to the challenge and used the space to engage their audience from all sides.

“It’s definitely been great having outside practitioners and professional theatre practitioners coming in and working with the students. The energy and the passion that brings, and then what that shows the students as well, is so important. It shows that some people follow it [acting] their whole life and just what you can do with theatre,” says Tamsin.

The programme was set to be a one-off project, however the success of the performances and the enthusiasm from those involved may just signal otherwise.

Read more about the lead up to the performance in a previous Education Gazette article, Exploring Māori histories through performing arts.

The performance used a traverse stage, like a fashion catwalk, to capture the audience from all angles.

Mariah Scott may have only just finished her social work degree, but she is no stranger to field work. The last two terms she has been working as a re-engagement officer for Tawa Kāhui Ako.

The Tawa Kāhui Ako is a community of learning dedicated to the support of student success and wellbeing in north Wellington. It has one college, one intermediate and six primary schools. Mariah Scott is based at Tawa College, and it is these students she works the closest with.

The opportunity to create the position of a re-engagement officer came from Ministry of Education funding. The role is designed to help students who are not engaging with school at all. It involves meeting with them and their families to find out what’s going on in their environment, both inside the classroom and at home.

Mariah’s involvement with Challenge 2000 led her to the position. She is one of many personnel attached to the professional and dynamic youth development, community and family social work agency that operates around Wellington.

“My role with them [Challenge 2000] started as a social work student, and now that I’ve finished my degree, it’s rolled through to being a youth worker.

“Part of my role is working for the Kāhui Ako. It’s mainly about those students who are not attending at all or disengaging. Students that have bad attendances which could be for a range of reasons.”

Mariah helps students and families tap into the resources and communities that might be able to support them in their personal lives, and she then looks at ways to make their transition back through to school a bit easier.

“Some of these students haven’t been going to school for a few months or a term or half a year, and it can be really hard coming back into to the learning environment. So, I work on making that as easy and smooth as possible, making plans with their deans or their teachers about how that might look for them, and having individualised plans.”

Mariah will talk to students about what their interests are and how they align to the subjects that they are taking. She will ask which teachers they felt a connection to and whether there is the possibility to move classes or switch

their timetable. She will also look at non-academic activities the school could offer, such as sports, to spark interest in being part of the school environment.

A lot of her work does involve helping to resolve personal problems such as anxiety, depression, or trouble sleeping. In these situations, she will make referrals to other services that might be able to help.

Mariah recognises that re-engaging students is complex and can involve finding multiple services and solutions to help address attendance issues.

“When working with a young person, you’re not just working with the young person, you’re working with their friend groups, whatever’s going on at home, and their interests. So, it’s a lot more complex than saying ‘look, you need to attend school’.”

Even when barriers are removed, success is not always guaranteed.

“It varies on the individual and whatever is going on in their personal life and it depends on the young person’s drive to be attending. That’s why I look at their interests and their future.

“If they do have an idea of what they want to do, then I will say ‘if you want to be a builder, then you need to have your maths, English and science... this is just a minimum criterion and if you don’t like it, this is what it’s going to look like for you when you do leave school’.”

Mariah says Covid has played a part in the some of the levels of disengagement that have been occurring.

“There are students that are Year 11 now or going into Year 11 next year whose whole secondary school experience has been through Covid, and so they haven’t been familiar with the school environment enough to have settled in and don’t feel any kind of connection with school.”

Problems with transitioning between schools has motived Mariah and the Kāhui Ako to work on plans to ease the experience for students. This will involve more than just one visit to the school they will be attending and will include follow-up sessions with students in their first term and mid-year.

“When working with a young person, you’re not just working with the young person, you’re working with their friend groups, their whatever’s going on at home, and their interests. So, it’s a lot more complex than saying ‘look, you need to attend school’.”Mariah Scott Mariah is happy to be working on helping students find success.

Students are encouraged to find out more about the world they live in with projects.

Community guest speakers, a bespoke timetable, and a focus on authenticity helps bring project-based integrated curriculum to life at Mt Hobson Academy.

Mt Hobson Academy (formerly Mt Hobson Middle School) opened in 2003, and Alwyn Poole, now of Innovative Education Consultants, was the teaching principal for the first 18 years. He had developed a projectbased curriculum in 2002 prior to working at Mt Hobson.

Alwyn wanted to find a way to capture the interests of students and have them develop a love of learning. He researched different methods across the world and came

up with a model that he thought would work well in New Zealand.

As part of the model, students have eight projects during the year, which is one every five weeks. During the project, teaching is directed towards equipping students with the skills and knowledge to complete their project.

For example, one of the projects for Year 10 students explores ‘Law and Culture’. One of the project tasks for

science is to explain the role of forensic science in law and to describe how chemicals are used to test for the presence of blood, fingerprints, gunshots, and so on.

At Mt Hobson, the division between classroom teaching and project time is split between four hours of unbroken teaching time in the morning. Alwyn says that having the unbroken time gives students certainty about their day.

This is complemented by the Arts and Activities afternoons which include community learning, community service, art, music, sport and physical education.

Applying learning to real-life contexts

“The debate which has been going on for a while is about, ‘Is education about teaching students how to learn or is it about gaining knowledge?’ I think we hit the pendulum right in the middle with our approach,” says Alwyn.

He appreciates that not all schools may be able to take this approach but says it could also be accomplished with four weeks of teaching directed to a project, and then having one week of solid project time.

The projects allow students to work on authentic tasks and show them how knowledge works within a real-life context.

They also have the ability to make the projects personal, which can help to increase student engagement.

“Children will come to us and tell us what they want to learn.

“Students must decode the tasks, which sounds complicated, but it’s really learning to answer key questions. Initially, students will go, ‘What do I do about

that? I will go and ask a teacher or I will ask at home’. When they’re a little more developed, it’s more, ‘What could I do with this task? I understand what I’m supposed to do, but is there something that I can put on top of it?’”

To help students with their projects, the school will look to different ways they can engage with realistic situations and sources.

“They get a chance to research authentically. They can speak to adults because in the afternoon we have community learning every week where we have guest speakers and field trips,” says Alwyn.

Over the years, Mt Hobson Academy has had 97 percent of graduates progress to Year 11 and achieve Level 1 NCEA. For a good portion of those students, this wasn’t the trajectory when they first arrived at the school (for a range of reasons).

The projects can integrate the learning within a year, but the model is also designed to work across the school so that all years have a combined focus.

Alwyn sees one of the ways in which this helps students is to provide milestones and opportunities to build on progress with the start of each project, rather than an overall year evaluation.

At the end of each project, students and their families are involved in the progress evaluation.

“This approach enables high quality teaching and learning with that nice balance between skill sets and knowledge, which is crucial; you can’t learn without a context.”

“The debate which has been going on for a while is about, ‘Is education about teaching students how to learn or is it knowledge?’ I think we hit the pendulum right in the middle with our approach.”

Alwyn Poole

“I have loved the projects this year as it has allowed the students to explore their own interests and get thoroughly immersed in a particular area at a time. My Year 7–8 class examined the Native Forest project and it is that knowledge that they have applied to calculate that the current carbon tax on our farmers is illogical. One of our students worked out then that a moderately grown field of grass can process more carbon than a fully grown tree.” Marija Naumovska, Academic Manager Mt Hobson Academy

“The project-based learning Mt Hobson offers has been great for my daughter learning from home; not only does it give her the chance to learn what she’s feeling passionate about for the day and interested to engage in it gives her the control to be independent with her learning.” Parent of Year 10 student

“Both our girls really love the project work and are progressing very well academically. They can see the ‘real world relevance’ of the various subjects as they work through each project.” Parent of 6-year-old and 9-year-old girls.

“On Monday, in our period 3 English class, we had Justin Kleinbaum log onto the meeting. As a class, we prepared questions related to law beforehand to ask. He shared his information and experiences about being a lawyer with the class. He talked about the differences between common and civil law, as well as cases he has worked on and what made them memorable. This interview tied in well with our project 7 task.” Year 10 student.

A current campaign by the Ministry of Education, Become a real influencer. Go Teach, aims to encourage more young people to enter initial teacher education and influence the next generation. With real young people talking to other young people about the positive influence teachers had on their lives, this campaign highlights how rewarding a career in education can be.

Teachers are part of the formative years of all young New Zealanders. Their presence is undeniably influential in how the next generation sees and takes their place in the world.

Teachers can elicit hope and ambition in students that they may not find elsewhere. By highlighting this mahi in communities across the country, the Ministry of Education is inviting those wanting to make similar positive impacts to look at how a career in teaching is the way to go.

A teacher’s legacy lives on outside the walls of a classroom.