CO-EDITORS & DESIGNERS (& storytellers)

Sara & Dave Snow

CONTRIBUTORS

Cecelia Brooks

Jennifer Campbell

Al Douglas

Emma Hassencahl-Perley

Emily Lawrence

Kat Frick Miller

Jody Nelson

Colleen Thompson

THANK YOU

To all of you—our readers, advertisers, contributors, our friends and family—for supporting local storytelling and independent print media. We couldn't do it without you!

SUBSCRIBE

edible Maritimes is published four times a year. Subscriptions are $32 and available at ediblemaritimes.ca

FIND US ONLINE ediblemaritimes.ca instagram.com/ediblemaritimes

ADVERTISE WITH US

There is no denying the exquisite beauty of a frosty autumn walk—as if, while we slept, Mother Nature herself had spent an artful night in the trees. And it is hard to resist sharing these moments. Autumn is that time of year when we celebrate the hard work of summer and a garden’s bounty. We bring in baskets of tomatoes to be stewed, squash to be stored and roots to be pickled—all to enjoy together.

In her piece on The Flaxmobile Project, Jody Nelson suggests there is “relationality in small scale”—moments of connectedness in communitybased creative work. This theme of collectivity runs through this issue— whether it’s sharing a recipe or planting seeds, preparing a meal or starting a new project, painting a mural or decorating a cake. In this issue, we bring you stories that highlight the creativity of community and what can happen, as the youth of Hope Blooms show us, when we plant some seeds.

Before you dig in, we want you all to know that the making of this issue was largely fuelled by handheld pastry. We highly recommend cozying up by the fire or setting off on your next adventure with that sort of buttery goodness that is best described by Emily Lawrence, in her piece on a Portuguese favourite, as “shatter pastry”. We can guarantee such goodness goes very nicely with a helping of Maritime storytelling.

Artfully yours,

Sara & DaveAlyssa Mersereau, Marketing Assistant hello@ediblemaritimes.ca ediblemaritimes.ca 506-639-3117

PUBLISHERS

Sara & Dave Snow

Steadii Creative Inc

No part of this publication may be used without written permission by the publisher. Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings and omissions. If, however, an error comes to your attention, please accept our sincere apologies and notify us. Thank you, © 2023 Steadii Creative Inc.

All rights reserved.

St Andrews, N.B., E5B 1C5

edible Maritimes is proudly created entirely by humans and printed in Canada on paper made of material from well-managed, FSC®-certified forests, from recycled material and other controlled sources.

Through 1% for the planet we contribute one percent of our revenue to environmental non-profits.

edible Maritimes

Read it, love it, share it!

Please reuse and redistribute this magazine - read it again and again or pass it on!

it is frosty Mi'kmaq

frost Wolastoqey

We respectfully acknowledge that we are in Wabanaki territory, on the unsurrendered and unceded traditional lands of the Wolastoqey/Wəlastəkwey, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy peoples, who have stewarded this land throughout the generations. This territory is covered by the Treaties of Peace and Friendship which the Wolastoqey/Wəlastəkwey, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy peoples first signed with the British Crown in 1725 recognizing Wolastoqey/Wəlastəkwey, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy title. We stand with them in their efforts for land and water protection and restoration, and for cultural healing and recovery.

Edible Maritimes

Language resources: www.pmportal.org www.mikmaqonline.org

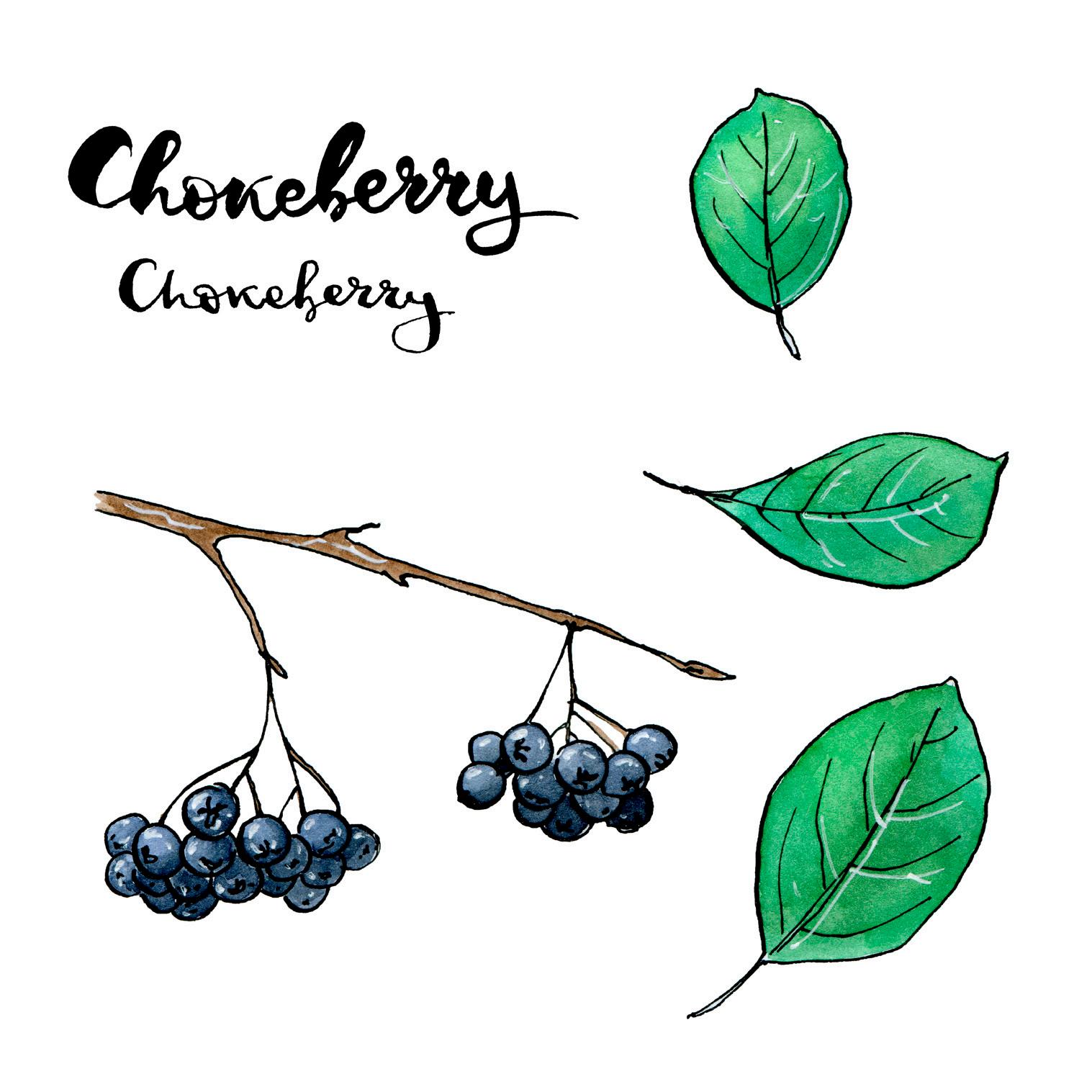

Cecelia Brooks on sweetening fall with wild chokecherries (Prunus virginiana)

WORDS & PHOTOS BY CECELIA BROOKS

WORDS & PHOTOS BY CECELIA BROOKS

Summer is moving towards autumn now with cooler days and evenings. The many white blossoms we saw on the chokecherry trees in springtime have become berries and are beginning to turn from red to black. The chokecherries become sweeter as they darken to black with a slight red hue. The acrid flavour subsides and there are more cherries than one can eat along the sunny edges of our Wabanaki forests, but you need to get there before the birds, raccoons and bears forage them away.

The chokecherry is quite acrid when unripe and that may be why the settlers named them chokecherries, but for the Wabanaki the whole tree is an important food and medicine. The Wolastoqiyik call them oluwiminol (o-lu-wi-minol) while the mi’kmaw word is poqwa’lamgewe’l (bo-hgwaa-lamke-wel). The root word Poqwa’lai means “I have a dry throat” which makes sense as the bark of the tree is collected during the fall to treat sore throats in the winter months. The wolastoqew word has the root “min” which means berry in both the Wabanaki languages. Languages evolve through time and I can only speculate why the mi’kmaw describe the use while the wolastoqew describe perhaps who was known for picking the berries. Oluwi is the wolastoqew name for “Louis”, a French proper name. Whatever the meaning, these berries are abundant and very useful as a food and medicine in the past and certainly into the future.

Black cherries also grow in Wabanakook (land of the Wabanaki) and look very similar and are also sweet but do not grow in clusters as the chokecherry. Be careful to positively identify the chokecherries as they ripen around the same time as buckthorn berries, which are invasive and toxic. Eating the buckthorn berries will cause severe abdominal cramping and diarrhea so be absolutely positive you have the chokecherry shrub. There are many books for plant identification as well as reliable online sources. Positive identification is very important for any wild plants you intend to forage.

The pit of the chokecherry is quite large so it takes quite a bit of harvested fruit to make a dried fruit so I prefer to juice them and make a jelly. The pits make great noisemakers in shakers/rattles if you are a crafter of such things, so save them if you need them. Many recipes for chokecherry jelly use lots of sugar that I find masks the unique flavor of the berries. Pectin is also

used to thicken but if you have the patience you can naturally gel the juice since they are naturally high in pectin. It takes about six pounds of berries to get four cups of juice so pick plenty for a great treat with your peanut butter sandwiches this winter or maybe you can make thumbprint cookies with a dollop of chokecherry jelly in the center. However you decide to eat your chokecherry jelly I am sure you will not be disappointed by the flavor as they have a complex flavour missing from horticultural cherries.

Cecelia Brooks shares her recipe for saving a sweet late summer flavour

4 cups chokecherry juice

2 cups sugar

Juice of one lemon (approximately 2 tablespoons)

First you will need to juice the berries. I use a steam juicer that I use to juice all my wild berries and if you are an avid forager of berries you may want to invest in one. The steam juicer also eliminates the need to strain the juice from the pulp, saving time and effort. You can also make the juice by putting the berries into a large pot with a cup of water and simmer while mashing and stirring for about 30 minutes when the berries will release their juice. You will then need to strain through a jelly bag or line a colander with several layers of cheesecloth. Leave this to drip overnight and don’t squeeze the bag if you want a clear jelly. If you don’t mind a cloudy jelly go ahead and squeeze.

I prefer a less sweet jelly so I use only 2 cups of sugar. The sweetness is entirely up to you so put the juice into a large heavy bottom pot and dissolve 2 cups of sugar in the juice and have a taste. Add more if you wish. Add the lemon juice and bring the mixture to a hard boil on medium-high heat. Keep in mind that the mixture will bubble quite a bit so do not fill the pot more than half full as you will need headspace for the bubbles. Stir continuously to prevent scorching for about 20 minutes or until the temperature reaches 104 C (220 F). Pour the prepared jelly into clean and hot jelly jars. The acidity of this jelly is sufficient to safely can in a water bath so a pressure canner is not necessary. Follow water bath instructions from your canner owners manual. You can also just freeze it or keep in the refrigerator if you plan to eat the lot within a few weeks.

If making the jelly is too much to do now you can also freeze the berries or juice to make later. I met a woman a couple of weeks ago that freezes the juice and puts it in her morning smoothie. I’m not a fan of smoothies but thought this was a great idea to add anti-oxidants to your regular smoothies. Pound per pound there are more anti-oxidants in chokecherries than our beloved blueberries.

Enjoy!

Re-crafting the story of linen in Nova Scotia

Stooking, retting, breaking, scutching and hackling—words that roll off Jennifer Green’s tongue, but have been heard by few in the Maritimes for decades. These words are part of a forgotten legacy of fibre farming—practices that were once carried out by hand and shared by communities.

Flax is the source plant for the fibre used in the making of linen. Flax stands straight and tall, with vibrant violet blooms that close in the night and give way to bolls that hold the flax seeds used as food or pressed for oil. It is the stem that produces the strong and lustrous fibres that are used in the making of linen yarn for weaving into fabric. As a material, linen, and other localized fibres, have been displaced globally by industrial textiles, over 80% of which are derived from polyester and cotton. Material diversity has been lost. We see the same pattern in our food supply. But why does it matter? What is the significance of reviving local linen making?

“We’ve lost a tradition or culture of storytelling through our clothing…seeing our clothing as cultural artifacts, distinct from capitalism,” says Green, Associate Professor in the Textiles and Fashion Department at NSCAD University. Diversity is a part of the cultural story our clothing holds. Brand identity has replaced this. Fast fashion is highly exploitative of people and the planet. The invisibility of this burden, the inequity in who bears it, and the privilege to those who benefit, all fuel Green’s values regarding fashion and its place in society.

Alongside the decline of culture and diversity in our clothing, there has also been a loss of craftsmanship, including the quality of materials. “When I began my linen weaving journey in the early 2000s, I saw that the imported linen and yarn I was buying was dwindling in quality over time. It was fraying and snapped easily,” recalls Green. Her ethos and her artistry craved a return to the source of the materials she was working with, which for linen, means tracing the material back to the flax plant, and back to a local tradition of home grown and processed linen. A reclaiming of quality and story. “In my textile education at NSCAD, there was this belief in the purity of materials—that the materials hold the answers,” shared Green. “It was a natural progression to go from linen weaving to studying the spinning, to growing…going back further and further to the source of the fibre in order to become a more skilled craftsperson and to understand the material in

For Green, getting to know the flax plant was inspirational. She gained a deep understanding of how the properties of the plant relate to those of the linen fibre. “How the plant grows, how it is harvested and processed,” she says, “even how the fibres transport moisture from the root to the tip and hold the plant upright… all contribute to making linen a dimensionally stable material. It has a lot of body to it.” Getting to know the plant connected the dots for Green and grew a deep love and appreciation for the story of linen, which became the heart of her sabbatical project.

It started as a dream of operating a linen farm. “I was actively looking for property. I even had a yurt picked out,” says Green. But things weren’t falling into place. “I was having a hard time finding land and it was just after Covid… the thought of being in a new, somewhat isolated community was a bit daunting.” Green was driving back home to Halifax from a visit to Cape Breton where a fellow lover of linen, Kristi Farrier, had offered Green land to grow flax on so that they could grow together. “I got thinking as I drove, what if that is the answer? Finding several farms to grow flax on is what the research project is about?” Once this idea was sparked, it immediately ‘felt right’ to Green. She dove into making it happen. In only three months, the Flaxmobile was in motion.

You can’t miss the Flaxmobile. It is a souped-up cargo van with a whimsical flax blossom graphic along the side. Jennifer Green hit the road in April of 2022, seeing out a whole season of flax growing on 15 farms across the province. She was there for every stage of the process —planting, tending, harvesting and processing. In exchange for her knowledge and support, farms shared the harvest 50/50 with her. “Most of the farms had never grown flax before so it was an opportunity to have someone teach them the process one-on-one,” says Green.

The goal was to do everything by hand in the first year. TapRoot Farm in the Annapolis Valley has small scale flax processing equipment (a story unto itself) which could be accessed in the future, but the Flaxmobile prioritized starting on a micro-scale. It was important to Green that the project was cross-disciplinary. “If it was just about agriculture, less attention would be paid to the quality of the fibre as a material—the length, oil, and drape of the fibre,” says Green. The emphasis

Page 9: Field of flax with Jennifer Green and her Flaxmobile

Right top: Green with a group of harvest volunteers in Cape Breton

Right bottom: Hackling scutched flax to turn it into a fibre ready to spin.

Page 12: Harvesting flax

Page 13 top: Inspecting flax ready for spinning

Page 13 bottom: Sorting the harvest

Page 9: Field of flax with Jennifer Green and her Flaxmobile

Right top: Green with a group of harvest volunteers in Cape Breton

Right bottom: Hackling scutched flax to turn it into a fibre ready to spin.

Page 12: Harvesting flax

Page 13 top: Inspecting flax ready for spinning

Page 13 bottom: Sorting the harvest

understand the quality of the fibre in relation to the growing and processing. “If we intend to create a textile industry in Nova Scotia, we have so much catching up, or relearning to do. It's why farmers need to be a part of the process.” Through attention to connection, iteration, and shared practice, transfer of cultural knowledge can happen.

We can imagine the making of garments as art or craft but the steps along the way can be too. There is artistry in the know-how and the sensing that goes into every step from seed to garment. We have lost this along the way in favour of doing things faster, easier, or more profitably. At an industry level this is part of the supply chain wherein raw materials are produced or processed in disconnection from the end use of the materials. One of the big motivations for the movement to localize is to close the loop on this supply chain in our local regions. When things are manufactured in our backyards or by people in our communities, we are more likely to appreciate the story of the material and to avoid waste. The Cape Breton Centre for Craft and Design has been digging deeper into sustainable craft, and how a region like Cape Breton can close the loop on the craft supply chain. Interestingly, if you look at home-based crafts, the birthplace of most of our cultural practices, local and sustainable supply of raw materials is built into the practice. Homesteaders close the loop on as many of their essential and material needs as possible, and live with an ethic of sustainability, turning would-be waste products into items of beauty and function. Scrap fabric

becomes quilts, sheared wool becomes clothing, and animal fat becomes tallow for soap.

There is contrast in Green’s nomadic approach to something land-based, but she is not the first to take fibre arts to the road. Weaver, occupational therapist, writer, and educator, Mary Black worked across Nova Scotia in the 1940s-50s, supporting rural craftspeople to develop and market their works. Black travelled around the province with a loom on a trailer, to teach people how to weave again. With a widespread rural population that holds a lot of the remaining traditional knowledge, this mobile service makes sense in order to meet people where they are at. It also echoes the history of itinerant harvesters on the prairies; mobile reinforcements to contribute seasonally to communal labour adds a festive rhythm to the harvest and much needed hands and hearts.

When Green first began her deep dive into flax she would go to the Nova Scotia archives every day. She would diligently and thoroughly go through the censuses from the 17-1800s. “I would make charts, and write down anything related to flax and linen and where it was being produced across Nova Scotia.” This understanding gave her a strong appreciation for the history – how prolific flax growing was in the past. “In a modern context I couldn’t have anticipated how this would translate to the deep appreciation for land and community that came along with it.”

Joining in the harvest of the flax crop here in Cape Breton, I can almost imagine how it may have felt when this was the shared work of community. There is a special kind of conversation that surfaces while we work. We talk of everything and nothing: birds at dawn, grey seals on the shore, sweetgrass harvest, gardening, comparing growing years, sunsets, admiring the variability in the flax plants, and so on. We are present with our senses and feeling the hard work and hot sun in our bodies. The volunteers that came out were all drawn by their own passion for fibre. One harvester, Stephen, was retired from a career in archaeology, with a specialization in fibre.

There is something about doing this on a small scale. There is a relationality to it. It is families, friends and neighbours doing the work, growing on their land, producing unique harvests and unique fibres—a terroir of sorts. It's personal. Plot sizes vary, based on the workload each farm can bear. A typical 4x8 ft plot produces enough fibre to make a small household textile. The labour is definitely the limiting factor, but volume hasn’t been the goal. “I believe in the idea of aggregating what has been grown and making something out of the collective sum of all of the small farms,” says Green, who intends to make work shirts with her share of the fibre—a representation of the shared labour of love. A lasting connection between the places and people that have contributed.

For Green, what started as an interest in sharing her passion for linen gave back in unforeseen ways that fueled a different part of her. “I got to witness and participate in a deeper connection to place,” shares Green. “I experienced hospitality like never before, and loved seeing the way these farming families were living - the way their children had such a strong sense of themselves. Like there’s an essence of something solid that comes from living like this.” With the challenging social and environmental future ahead for young generations, this was reassuring for Green.

The return to hand-grown and hand-processed linen has felt like a ‘coming back to ourselves’ for Green. What started as a post-Covid journey with an anticipation of isolation in rural Nova Scotian communities, has become a journey of connection making. The cultural story of linen as clothing, has unravelled a deep sense of place and history that Green has played a role in weaving together, with the help of so many hands. One farm at a time, Green has been reviving cultural knowledge. One day it may add up to a sustainable fibre industry in Nova Scotia, but she has a sense for where it starts—building of a community knowledge base and a care for it.

The Flaxmobile Project flaxmobile.com Jody Nelson stewards a piece of land on Hunter's Mountain, Unama'ki, where she invests her heart in her farm, her two boys and her community.For the Famous Town Pie Shop's Jennah Barry, it's all about the butter, and process

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

Tucked in behind the busy town centre of Mahone Bay, two customers stand at the counter of a little shop on Orchard Street. They both order coffees and consider their options. One chooses a Caramel Banana Bun and the other an All Day Breakfast pie. The breeze slips in the door, as another customer steps in. She is picking up a custom-order cake. Jennah Barry emerges from the kitchen with a cake box and her one-of-a-kind smile, a smile that radiates warmth well beyond the typical warmth-radiating sphere humans are capable of. It’s the kind of smile that might seem right at home on stage.

Barry is the baker behind Famous Town Pie Shop. She and her partner, Colin Nealis, opened the shop on April 1st and Barry marked the day with a cake iced in floaty clouds on a blue sky and the words “Dreams do come true!”. She had made 250 hand pies for that first weekend and sold all of them in one day. On Monday, she took a deep breath and got back to rolling. They hadn’t expected such instant demand but they are embracing the enthusiasm for their new business.

When the kitchen space in the Orchard Street building came available last winter, Barry and Nealis considered the opportunity for a heartbeat. “It all came together in the span of two weeks,” Nealis says. “We signed the lease in February, and I was leaving on tour at the end of February so we just had a month.”

Despite the quick opening, Barry says the bakery was a long time coming. “I’ve been thinking about this forever and imagining what it would be like,” she says, “the ideas were all there. We just had to put it together.” Barry designed the logo herself and the name is a nod to a shop her grandfather ran in Lunenburg years ago.

In addition to being elbows deep in the pastry business, Barry and Nealis are musicians with a long history of performing and recording together. “We met at jazz school in Toronto,” Barry tells us. “He actually taught me how to cook in college,” she adds. “I hate to say that because my mother is an incredible cook.”

“Her mother is an incredible cook,” Nealis agrees. The pair also agree that cooking together was a central theme in their college days. After college, Nealis returned to his hometown of Victoria, B.C., and a few years later they reunited, both focused on their music careers.

“I really love singing, I’ve played music forever,” Barry says, “but I didn’t really get into the process of practice,

into the industry and the touring. People think music is living the dream but you have to love the process. Colin loves the process. He’s made all of my records. He is a really good producer and can play everything.”

“He likes all of the weird difficult things I don’t like,” she adds with a laugh, “I don’t know how to do numbers and he does—which is make or break in the pastry business.”

“On the creative side,” Nealis says, “When Jennah has an idea she goes with it and she does it very well. Like putting a recipe together. That’s why it works for us. It’s like a yin yang for us.”

“It’s about finding a thing that you love the process of,” Barry adds. “In between touring, I would have baking jobs where I would work for 12 hours straight and I loved the process of it. I really like working with pastry and just want to make food that is warm and good and that I would want to eat. When I eat a cherry pie,” she says, putting her fingers to her lips, “I want that red and the sugar and the sweet. And the pastry, full butter. My mom is a really generous baker and she taught me to be generous. Err on the side of generous.”

In addition to buttery goodness, Barry wants to create things her local community can enjoy all year round. “It’s not hard to sell butter,” she says, “but it’s important to me that the flavours and the price are accessible.”

As we talk about local flavours, our conversation shifts from pastry to music and we talk about renowned folklorist Helen Creighton who travelled throughout the Maritimes, recording and sharing traditional music and stories. “I’ve been thinking,” Barry says, “about how there are so many accents that are disappearing, we’re getting non-colloquial.” We talk about our own intonations and inflections. “Just drive down the road and it changes,” she says. “All of those linguistic regional traits never went away here,” Nealis adds.

“Part of what I want to do here is incorporate Nova Scotia recipes,” Barry says, as if recipes themselves—the ways we prepare food for each other and share those recipes—are a sort of language, with its own distinctive regional traits, those old cookbooks like Creighton’s recordings of traditional music. “I want to go to Nova Scotian recipes,” she explains, “and those old dutch oven cookbooks—super simple but so good. We’ve had a Lunenburg sausage roll and sweet pickled pork pies and they were very popular.”

“I grew up here,” she says, “it was always important to me to make something that I know. I find pies, and meat pies, very maritime.”

Barry and Nealis live with their two children up the road in Clearland where Barry grew up, just a short e-bike ride from Mahone Bay. Nealis is recently back from a tour and is building a recording studio at their home. “I travel a lot for work,” he says, “With the studio, I can be here more.”

Their daughter Margot leaps into the kitchen. “Mama, I want some lemonade,” she says, disappearing just as quickly to see a friend who has just sat down in the garden. “Pastry and kids go well together,” Barry says, “that was a huge thing for me, to make something they would eat.” Nealis points out that the ham and cheese pie is Margot’s go-to, while Barry says two-year old Sonny will try any of them, including the vegan ones.

In addition to hand pies, Barry makes a range of treats that include savoury galettes, caramel pecan pie bars, cookies with sprinkles and others with chocolate chips, cherry-filled cupcakes, pink lemonade snacking cake, and gorgeous cakes elaborately decorated with rich buttercream icing in every shade of every colour. “I

really like making cake,” Barry says.

Meghan, who holds down the front of the shop, leans in through the kitchen door and says “Spicy Pork and Spinach”. Barry responds with a smile and turns to fill a tray with pies. “I never feel like the boss,” Barry says. “It’s really helpful to come at this from being an employee in food because you’re very humble and you know it requires the skill of so many people. You can’t do it all yourself. I’m really lucky that the people around me know how to fill in the blanks.” A typical day at the Famous Town Pie Shop sees Barry in the kitchen, sometimes with another baker, or Gillian who comes in to do trays of shelf-stable flowers for the custom cakes. “I love that I have all of these flowers here,” Barry says as she slides a tray of pies into the oven.

“We have the most incredible team on the entire planet,” Barry says. “Everyone who works here is some kind of artist.”

At the counter, Meghan whirs steamed milk art into a cup of espresso for a customer. “It’s always pretty steady,” she says. Originally from Montreal’s south shore, Meghan came to Nova Scotia for art school and moved to this south shore last fall. Of joining Barry at

Famous Town Pie Shop, Meghan says with a smile, “We’re this group of friends, that get to spend all of this time together.”

Making a batch of hand pies at the Famous Town Pie Shop is a three day process. During assembly, the large table in the middle of the kitchen fills with pies and is truly what dreams are made of. “This is what I want to do—the baking,” Barry says as her eyes light up. “I don’t want to become the HR person, and I’ve been really conscious of that. It would be really nice if we could sustain ourselves with this shop.”

Margot pops in again. “You’re making me a lemonade,” she says with a bit more determination this time.

“Okay, I’m making you a lemonade,” Barry says, with that smile.

Famous Town Pie Shop

16 Orchard St, Mahone Bay, NS

famoustownpie.com

Page 14: Jennah Barry outside her Mahone Bay shop

Page 15: Barry with Gillian's flowers

Page 16 top: Margot bounding into the shop

Page 16 bottom: Nealis at the counter with menu

Page 17: Barry and Nealis

Page 18: Barry with a tray of fresh baked hand pies

The inspiring youth of Halifax’s Hope Blooms show us what it means to be change agents

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

One day, when Kolade Boboye was eight years old, a friend asked him to join her at a community garden. He wasn’t sure gardening was his thing. “What eight year old knows they like gardening,” he says with his broad smile. His friend was convincing, so he went along and soon realized it wasn’t just about gardening. “It was a chance to meet people, so I signed up,” he remembers, “and ever since then I have stuck around.” Fifteen years later, Boboye is the Director of Social Business and Innovation at Hope Blooms, a non-profit organization in Halifax’s North End that engages neighbourhood youth as change agents in their community.

Boboye guides us through the expansive garden that slopes down toward Brunswick Street, between rows of tomato plants, squash plants full of big orange blossoms and bean plants that reach for the sky. Hope Blooms started as a community garden project nearly twenty years ago when Jessie Jollymore, a community dietitian, noticed four abandoned garden beds in Murray Warrington Park. “She had an epiphany to grow food,” Boboye explains, “She wasn’t sure at the time what that would look like but she started an after-school garden program. She really wanted to engage neighbourhood kids. And it was also a way to tackle food security. This area was a food desert,” Boboye says. “The nearest grocery story then was two kilometres away.”

As more youth got involved, their ideas began to shape Hope Blooms and it grew to include several social enterprises where youth learn, hands-on, how to create, build and sustain a social business. Possibili-teas is one such enterprise, where youth partner with Senegalese single mother farmers who grow hibiscus. They purchase the hibiscus and create herbal teas, selling their teas to raise funds for food gardens in other equity deserving communities in the province.

Hot Cocoa Boys, another long-standing social enterprise at Hope Blooms, began as a summertime lemonade business. When the weather cooled the boys switched to hot cocoa and soon found a growing demand. They sell their hot cocoa products at farm markets and partner with Atlantic Superstores throughout Nova Scotia to raise funds for social programs such as the new basketball

court across the street. They are currently saving up to install a portable music studio at Hope Blooms. Most recently, three youth started Oh My Jewels, a social enterprise that brings together their Indigenous, Syrian, and African cultures through beading. They raise funds for youth to participate in leadership camps.

The longest running social enterprise, Fresh Herb Dressings, led to a pivotal moment for Hope Blooms. “I was ten at the time,” Boboye says, “and myself and four or five other youth would go to the Seaport Market with Jessie to sell our dressings.” They were soon selling out by noon and someone suggested they go on Dragon’s Den. It began with a local audition and culminated with Boboye and five other youth members pitching Fresh Herb Dressings on Dragon’s Den. “We worked on our script and our presentation and went to Toronto,” he tells us. They were asking for a $10,000 loan to build a

year-round greenhouse. “They gave us $40,000 to build the greenhouse!” Boboye says, as excited as if it had just happened.

That was ten years ago. The greenhouse project started off modestly. With the support of Build Right Nova Scotia, the Hope Blooms team designed and built an innovative, and beautiful, growing space—a long building on the lower corner of the park with large windows and solar panels along its south-facing roof. Inside, past solar batteries, garlic hangs from the rafters, ginger sprouts in a raised bed, and greens emerge from vertical growing units. “Dragon’s Den put us on a pedestal,” Boboye explains, “and Build Right Nova Scotia reached out. They loved our story and they

Page 19: Boboye in the garden with main building and greenhouse in background

Page 20: Boboye in front of the greenhouse

Page 21 top: El-Beshbeeshy watering the garden

Page 21 bottom: Farms and Greenhouse Programs Assistant Kenzie Morrison in the greenhouse.

This page top: Hope Blooms art from the rafters.

This page middle: Jessie Jollymore, Hope Blooms Executive Director (right) chats with friend, Dennis, under the moss wall in the Global Kitchen for Social Change main building.

This page bottom: Many hands make light work in the kitchen at Culinary Camp.

Right: Chef Tash (at left) gets her culinary campers started on the day's menu.

Page 24: A view of Culinary Camp

Page 25: Art of Hope Blooms and a display of social enterprise products

worked with us to build this greenhouse.” Build Right contractors and tradespeople contributed supplies and labour but it was the participation of Hope Blooms youth that sets this project apart. Boboye was on the design team and the experience sparked his interest in architecture. He points to the large bricks of the back wall that act as heat incubators, just as the bubbles in the windows do. “When it cools, the heat is released,” he explains. The floor beneath us is six feet of gravel to help with drainage and in the back corner, koi fish swim in an aquaponic growing system.

In addition to the greenhouse, Hope Blooms now has farm space at a farm in Broad Cove. This space has increased Hope Blooms’ growing capacity so they can grow more tomatoes, cucumbers, okra, eggplants and other vegetables for their weekly Thursday market and for their Hope Blooms culinary programs. The farm also provides more opportunity for youth to explore and participate in food production from the ground up.

Boboye leads us back outside, through the garden where Ali El-Beshbeeshy is watering tall plants along the raised border of the garden. El-Beshbeeshy started at Hope Blooms when he was young, as a Hot Cocoa Boy as well. He’s now a second-year engineering student at Dalhousie University and a youth leader here at Hope Blooms. Hope Blooms provides scholarships

to its youth through its Fresh Herb Dressings social enterprise. These scholarships add up to $250,000 to date as they support 13 youth in their post-secondary or other educational journeys. Boboye himself is a Hope Blooms scholarship alumnus and studied marketing and philosophy at Antigonish’s St. Francis Xavier University.

He takes us inside the main building—the Global Kitchen for Social Change—where long tables and comfortable seating invite people to sit down and chat. Jessie Jollymore is sitting with a friend at a long table below a towering moss wall. She greets us with her warm hello and a sparkle in her eyes. The space is filling with teens and excited conversation. Hope Blooms runs several summer camps and this week is culinary camp. The teens are donning aprons and gathering around the island in the large open concept commercial kitchen. Natasha Jollymore—or Chef Tash, the Manager of Food Programs—is walking the group through what they will be preparing in the kitchen today. “Chef Tash is also the mastermind behind all of the social enterprise recipes,” Boboye tells us.

When everyone settles into their food prep work, Dave snaps some photos and campers tell him what they are making today. He hands his camera to Alejandro, one of the campers, who eagerly asks for instruction and

sets off to take photos of his friends. The curiosity and enthusiasm in this building are palpable.

After a few more snaps, Alejandro hands the camera back and heads into the kitchen and Boboye takes us to the courtyard. This courtyard comes to life Thursday evenings as vendors set up, musicians play, and neighbours come to pick up fresh and prepared foods and, perhaps most importantly, be social. “The market is like a mini-festival,” Boboye says. The market started during the pandemic when the Hope Blooms team created up to 180 food boxes every week for community families. To improve food accessibility, Hope Blooms helps subsidize some of the food costs by partnering with vendors, and this year Boboye has created an app to help community members use and save their market dollars.

“The Hope Blooms Market Point is like a localized economy,” he explains, “and people are down to pay for market food because they see the value and their financial literacy skills also grow.”

Just below the courtyard, beside the blueberry patch, Maziah Clayton is taking a break at a solar picnic table. Hope Blooms has installed four of these off-grid workstations on their grounds to provide community members a place to charge up, to connect to wifi, and to sit and chat. “Families that live here can sit here in the evening and charge their devices and use the wifi,” Boboye says.

Clayton is one of the founding members of Hot Cocoa Boys. He joined Hope Blooms seven years ago. He’s in grade 11 now and, as a youth leader, trains younger boys how to market their hot cocoa products, and how to be community leaders. Clayton is also part of the new music camp. Boboye and a few alumni started a mobile recording studio which partners with this camp to help grow music and recording skills. “I started making beats, learning from my brother,” Clayton explains, “and now I’m recording.”

In their pitch to Dragon’s Den, one of the youth team, Tiffany, said, “When you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.”

The Hope Blooms community has transformed a grassy, neglected corner in Halifax’s North End into a truly blossoming space to grow and collaborate, cook and create. “I’ve worked in other places,” Boboye says, “but I think we excel here at creativity and adaptability. We aim high.”

Boboye tells us they’ve had requests to franchise but points out it’s not so simple. Every neighbourhood,

is unique—with its own set of challenges and its own needs. Each garden, so to speak, will grow a little differently.

It is impossible to leave this place uninspired. We are buoyed by the energy here and truly feel hopeful. While this approach might look a little different in every community, what a better place the world would be with more Hope Blooms.

Hope Blooms hopeblooms.ca

wici (pixels)

2022, Digital illustration

untitled (doublecurve study)

2023

Digital illustration

Emma Hassencahl-Perley is Wolastoqiyik (person of the peaceful waves river) from Neqotkuk (Tobique First Nation) in New Brunswick. She is a visual artist, curator, educator, and emerging art historian. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Mount Allison University and a Masters of Art in Art History from Concordia University. She resides in Neqotkuk and travels to Fredericton for work.

Emma is affiliated with the Wabanaki Visual Art Program at the New Brunswick College of Craft and Design, where she teaches art history to first-year students. She is the Curator of Indigenous Art with the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, and she maintains a professional art practice comprised of beadwork, murals, and digital illustration.

Emma is the co-author of "Wabanaki Modern," the unearthed story of the "Micmac Indian Craftsmen" of Elsipogtog (then known as Big Cove) that rose to national prominence in the early 1960s. At their peak, they were featured in print media from coast to coast, their work was included in books and exhibitions— including at Expo 67—and their designs were featured on prints, silkscreened notecards, jewelry, tapestries, and even English porcelain.

Her research interests within Indigenous Art History include Indigenous Feminisms, Craft and Textile History, Wabanaki Iconography, Oral History, and Decolonial Theory.

@emma_hassencahlperley

Link to purchase Wabanaki Modern: https:// gooselane.com/products/wabanaki-modern

Through material and visual culture, Emma's art explores her identity as a Wolastoqey ehpit (woman) and citizen of the Wabanaki Confederacy (People of the Dawn). Her painting and beadwork are inspired by Wabanaki double-curve iconography found beaded onto 19th-century textiles. These forms speak about relationships, community life, and being in balance with the universe.

QR Code: An Instagram filter created for “Mawiyewakon (Gathering), my 2023 mural for the 20th annual Tobique Powwow

Idon’t know how old I was when I had my first Portuguese custard tart, but I remember exactly how tall I was: tall enough for my nose to *just* poke over the bakery box on our kitchen counter. At the end of a day trip to Toronto, my mother brought me into Caldense Bakery to grab a dozen tarts to take home. The bakery was bustling and hot with steamy, vanilla-scented air. It was a treat enough to smell and look at these little bright yellow pastries, but to eat them was nothing short of sensational.

My autumnal take on this beloved pastry combines the characteristic custard filling and shattery shell with a classic pumpkin pie. This is the perfect laminated, artisanal pastry for home-bakers to try—it’s as forgiving as your self-described “people-pleasing” friend and incredibly satisfying. If you can make cinnamon rolls, you can make these. Bring these show stopping tarts to your Thanksgiving dinner or Autumn potluck. *crunch*

This recipe makes 12 tarts

For the pastry:

1 cup all-purpose flour

¼ teaspoon + ⅛ tsp salt

⅓ cup + 1 Tbsp water

½ cup unsalted butter, room temperature

For the pumpkin custard:

¼ cup white sugar

2 Tbsp all-purpose flour

3 egg yolks

1 whole egg

Pinch of salt

1 tsp vanilla extract or ½ vanilla bean, split and scraped

1 cinnamon stick

¾ cup whole milk

¾ cup pumpkin puree

Cinnamon for serving

To make the dough, combine flour, salt and water and mix until a dough forms. Gently knead on a floured surface for 1-2 minutes, until the dough’s surface is smooth. Rest for 20 minutes.

Using plenty of flour and a rolling pin, roll out the dough to a 12”x12” square. Imagine the dough to be a pamphlet flyer that folds into thirds. On ⅔ of the dough’s surface, spread ⅓ of the butter into an even layer, leaving a ½ inch border. Fold unbuttered ⅓ of dough overtop of the middle buttered ⅓, then fold the other buttered ⅓ of dough overtop of the folded

sections. The dough is very forgiving, so don’t stress!

Roll out the dough again and repeat the previous step. The dough may want to stay rectangular, but make sure the shorter length measures 12”. After laminating, allow to rest in the fridge for 10 minutes.

Roll out the dough again to a 12”x12” square. Trim edges. Spread the remaining ⅓ of butter over the whole surface. Roll the dough into a log starting at the bottom edge, then wrap in plastic wrap and allow to rest 2 hours or overnight, ideally.

To make the custard, combine sugar, flour, egg yolks and egg, salt, vanilla and cinnamon stick in a mediumsized pot. Add milk gradually while whisking to create a smooth mixture with no lumps. Put on medium heat and whisk constantly until it’s thick as pudding, about 5 minutes. When it starts to bubble, remove from heat. Add pumpkin puree, and whisk until combined. Remove cinnamon stick and vanilla bean, if used.

To make the tarts, pre–heat oven to 500 and place a metal baking sheet in the upper third of the oven.

Remove dough from fridge, cut into 12 even disks and place into muffin tin. Allow to sit for 10 minutes to warm up.

Using your fingers, press down in the center of the dough disk to create an even bottom layer, then press and drag to force the dough up the edges of the muffin tin. Don’t fuss too much. Made a hole? Patch it up and move on.

Distribute the custard between the 12 tart shells, filling them up ¾ full. I use a ¼ cup measuring spoon, filling it up to be ¾ full, then pouring into the tart shells.

Bake on the preheated baking sheet for 14-16 minutes until pastry edges are golden brown, then broil on high for 1-2 minutes until dark spots appear on the custard. Make sure to watch to avoid them burning.

Cool for 20 minutes before enjoying. Sprinkle with cinnamon to serve.

@emilylawrence

Seth Shaw heads up the kitchen at Mysa Nordic Spa in St. Peters Bay, P.E.I., where he runs a full-service restaurant that’s all about seasonality.

WORDS BY JENNIFER CAMPBELL PHOTOS BY AL DOUGLAS

WORDS BY JENNIFER CAMPBELL PHOTOS BY AL DOUGLAS

The Dish is a chef feature in which edible Maritimes asks a chef to produce a dish that represents them culinarily. The dish becomes the basis for a feature on the chef.

Seth Shaw grew up in the state of Maine, but from the age of 19, when he enrolled at the Culinary Institute of Canada, he’s mostly made Prince Edward Island his home. And now, he’s heading up the kitchen at Mysa Nordic Spa & Resort, in picturesque St. Peters Bay, about an hour northeast of Charlottetown.

Asked by edible Maritimes to produce a dish that represents him on a plate, Shaw made an elegant plate of seared scallops, served around a bed of local Swiss chard, fresh from the greenhouse on the property, and new P.E.I. potatoes that were cut into rounds and seared to look like the scallops. Garlic chips, small local clams and tiny bright yellow summer squash garnished the plate, along with basil oil and curry vinaigrette.

“It’s all in one pan,” the chef says as he explains the dish. “You do your potatoes first.”

He used grapeseed oil for the new potatoes, which cook quickly in the pan, then he cooked the scallops on high heat and deglazed the pan with water and red wine vinegar for the Swiss chard and baby yellow summer squash. He crisped the garlic chips beforehand and then drizzled the vinaigrette and green oil and added nasturtiums because they’re pretty, but also impart a peppery taste.

The whole plate was then given a saucing of lemon butter that he swirled the clams in before plating.

The plate represents his approach in the kitchen because it’s all local or regional with scallops from Digby, across the straight and down the coast of Nova Scotia on the Bay of Fundy. P.E.I. new potatoes are a staple of island summer dining, and the rest, with the exception of the lemon, are all locally produced or sourced.

Like many chefs, Shaw starts building a dish and a menu by looking at what’s seasonal and available. Having access to a greenhouse right on the property is a lovely perk of the job and he can bolster his pantry thanks to a local initiative called a “grower station,” which is a hub for area farmers to sell their wares and for chefs to have a one-stop local shop.

“So everything [that grows] on the island they ship

there,” Shaw says. “And then we order. It's a little easier than having to [track it all down on individual farms.] We still have a lot of suppliers, but that one place consolidates about 12 for us.”

Although Shaw was born in Maine, his mother is from Quispamsis, N.B., so growing up, he spent plenty of time in New Brunswick, and a family cottage in Murray Corner put him very close to his ultimate home in P.E.I., where his family also often vacationed.

“When I was looking at culinary schools, the ones in the U.S. were great, but very pricey,” Shaw says. “I was a dual citizen and I knew the culinary school here had a great reputation. We visited in, I think, 2005, and wow, I was very impressed. They gave us a meal in the dining room and it was very formal. And, it was still fairly close to family and the cottage.”

He took a year off after high school—“just to figure life out”—and then enrolled for two years in 2006. Immediately after graduation, he got a chance to represent Canada on its junior team at the International Exhibition of Culinary Art in Erfurt, Germany, in 2008. Often called the Culinary Olympics, it is the biggest gastronomic exhibition in the world, and that year, it attracted 54 nations and 1,600 chefs. The competition was founded in 1896 by a group of German chefs who wanted to showcase German culinary prowess while also learning about other cuisines from around the world. The first competition was in 1900 and it’s taken place every four years since then.

“It was quite a big thing,” he says, adding that the Culinary Institute was the school chosen that year to field the junior team. “I was the right age, in the right place and I did quite well in school so I got chosen for it. We trained for two years.”

There were several parts to the competition, including a cold plate and an à-la-carte plate for 150 people as well as a demo. In the end, his team scored a gold and a silver in the competition and came in ninth in the world. There were nine team members, including Adam Loo, who is head of culinary operations at the Murphy

Left: Chef Seth in the Mysa greenhouse Next page top: A view of Mysa Resort & Spa along St. Peters Bay Next page bottom left: Oven roasted onions Next page bottom right: Chef Seth's pan-seared scallops with a broccolini twist Page 36: Prosciutto and Corn Relish

Hospitality Group, the company that owns Mysa Spa & Resort and several other restaurants all over the island.

After the competition, he returned to Vero Beach, Florida. He’d done an internship at John’s Island Club, a private members-owned club with a “very nice, ritzy golf course” and he returned there for a season on the line.

“The executive sous-chef had done a stage at The French Laundry [a legendary restaurant in California], so that was pretty cool,” Shaw says. “I was under him. He was the person yelling at me. It was a good yell though. And he’d always come and talk to me afterward. It was really hard, but it was good. I learned a lot.”

After that season, he returned to P.E.I.’s Clam Diggers restaurant to work as a sous-chef under Loo, whom he’d met during the culinary competition. “He keeps re-appearing in my life. He introduced me to my wife, Lindsay, who is an islander from Sturgeon. We have two kids and Adam was the best man at our wedding.”

After Clam Diggers, Shaw moved to The Merchantman, a popular Charlottetown gastropub, as sous-chef before moving on to head up the kitchen at The Brickhouse Kitchen & Bar, a fine dining restaurant in downtown Charlottetown. He worked there throughout the worst part of the pandemic and though he loved it, he eventually stepped down.

“I was pretty much part of the great resignation,” he says. “I just needed some time. It ended up being a year and then Adam contacted me about this spa project. At first, it was just going to be a little tiny café, but as we talked, we decided we could do something really special here and he convinced the company to do a fullservice restaurant, and build the greenhouse. It was an opportunity to do something special and I think it is. The number of comments we get are great. We’re really humbled by that because we’re just starting.”

When it comes to mentors and influences, Shaw says Loo has been a big one, but on Canada’s Food Island, there have been many.

“It's a small area,” he says. “All the chefs I’ve worked with or done something with I’ve learned from, so it's pretty cool. You don't burn bridges because you never know where you'll end up next. You just do your work and try to stay focused.”

As the head of the culinary program at the Nordic spa, Shaw makes sure he treats his staff well.

“We do four-day work weeks,” he says. “Often our days are 10 to 12 hours, but sometimes they’re shorter. And with four days, it all evens out. Our mentality is that we want to take care of ourselves so we can take care of our guests.”

Guests certainly seem to be well taken care of. The spa offers massage services as well as the thermal spa experience, where visitors can enjoy a thermal bath, barrel sauna, Finnish sauna and a eucalyptus steam bath as part of their hot therapy. For cold plunges, there’s a Nordic cold bath, a cold plunge bucket, a cool shower and, in colder seasons, the wind from St. Peters Bay. The rest areas include a wood fireplace, a relaxation room, a lookout over the Bay and a meditation mezzanine. Then there’s the dining room, where guests can eat and drink, as well as a cozier living room-type space, with tables, couches and chairs, that overlooks the thermal spa, greenhouse and the bay. There are also guest cottages located to one side of the property, with a field of wild flowers that’s left unmowed for the bees.

In addition to the yields from the greenhouse, which include leaf lettuce, frisée, kale, tomatoes, eggplant and beans, Shaw gets mushrooms from Maritime Gourmet Mushrooms and some produce, including Savoy cabbage, from Soleil’s Farms.

The chef also harvests plenty from the sea, including scallops, halibut and mussels, though he says the latter are usually fall menu items because summer isn’t the best time to eat them.

“You can always get fresh lobster in the Maritimes, so we have a lobster roll,” he says. “We buy it, shuck it and make the rolls. Sometimes, we make lobster pasta.”

His approach is to take high-quality ingredients and highlight their essence.

“I try to put them on the plate without changing them too much,” he explains. “[I don’t want to take] a nice carrot we grew and then purée it. Instead, I’d put the carrot on the plate with some nice spice, and then I’d purée the carrot tops for a chimichurri or something.”

A childhood dream

“I knew I wanted to cook since I was eight years old,”

Shaw says. “It's like one of those weird things you say ‘I'm going to do this’ and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

He remembers cooking with his mom, and making cookies for church.

“It’s really that classic story,” he says of his early experiences. “Just the appreciation that you get from people who say things like ‘Oh, I love those cookies— you did that?’ And it just snowballed from there.”

Mysa Nordic Spa & Resort

St. Peter's Bay, P.E.I. mysanordicspa.com

Jenn Campbell is a native New Brunswicker, who spends part of each summer in P.E.I. with her Islander husband. She's been going to PEI for 30 years, but will always be considered "from away."

Al Douglas is a documentary and food photographer on Prince Edward Island who loves a good feast, especially if it comes with an island view.

Visit ediblemaritimes.ca for Chef Seth's recipe for his seared scallops on a bed of swiss chard

Add Chef Seth's tangy relish to your fall feast

6 ears of corn

2 medium red peppers

1 large red onion

10 thin deli slices of prosciutto

1 tablespoon oil for sautéing

Salt

1 tablespoon parsley, minced

1 tablespoon chive, minced

1 tablespoon dill, minced

1 cup apple cider vinegar

1 ½ cups white sugar

Preheat oven to 425 F. Husk the corn, toss in olive oil and roast in the oven for 12 minutes, turning once. Once cool, remove kernels with a knife. Roast two medium red peppers (tossed in olive oil) in the oven for 10 to 15 minutes. Once the skins are blackened,

remove from the oven, put in a small container and cover. When cool, remove the skins and dice.

Dice the onion. In a cast iron pan on medium heat, sautée all veggies until softened and season with salt. Bake the prosciutto in the oven at 425 F for 6 to 8 minutes, or until crispy. Remove from the oven and break it into pieces.

In a separate pan, heat the vinegar and dissolve the sugar into it to form a syrup. In a mixing bowl, combine the sautéed vegetables, prosciutto and syrup. Mix until cooled. Add the herbs. Serve with roast chicken or any fish, or put into any creamy pasta.

Dig in!

At Kingsbrae Garden’s Garden Café and Savour, Alex Haun and his culinary team create artisticallyinspired plates utilizing the freshest garden ingredients & products from all over New Brunswick.

Jeff Lutes brings his contagious enthusiasm to the Chandler Room Wine Bar and Kitchen where he and his team prepare sharing plates of seasonally- and seaside-inspired dishes served with a thoughtfully curated selection of wines.

Meet a few of our chefs, and let us wow you this fall!

explorestandrews.ca

Chris Aerni’s Rossmount Inn kitchen honours local ingredients and the people who produce them. Chef Chris and his team focus on the availability of products from their kitchen garden, the nearby organic farmers, the community supported fisheries and not least the seasonal foraging of wild foods.

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

If you’ve read Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series, you know the story—a 20th-century nurse happens upon a rocky cairn and slips through time, finding romance and adventure in 18th-century Scotland. Gabaldon’s writing is irresistible, evocative, drawing you in so that you can almost feel the Scottish mist on your face, or smell the meat-filled bridies warm from the oven. While 21st-century Sarah Bennetto O’Brien, owner and head chef of The Handpie Company, has not yet stumbled upon such a cairn, her journey to Prince Edward Island, and to handheld pastry goodness, might be just as charmed.

The bridie is Scotland’s version of the Cornish pasty—a shortcrust pastry turnover—and when Bennetto O’Brien baked a pan of them for her family years ago, she knew it was the beginning of something special. She had found a recipe for Brianna’s Bridies in one of Theresa Carle-Sanders’ Outlander Cookbooks and baked a pan for her family, with a P.E.I. twist. “It was mind blowing,” she tells us. “Why wasn’t anybody doing this? It was the most delicious version of P.E.I.. Shellfish is one thing but we grow some amazing food here.” She created several recipes for her own handpies, with P.E.I. meat, potatoes and vegetables, and incorporated them into the menu at her Borden-Carleton restaurant— Scapes. It was a tiny restaurant and soon filled with islanders, and visitors, hungry for handpies.

“They became more popular and I got involved in the Food XL program,” Bennetto O’Brien says, “where you pitch one product and it takes you through the whole process. I registered the name The Handpie Company and we found our niche. We switched to focus only on handpies, and then the owner sold the building.”

The loss of the space may have been tragic but it wasn’t long before Islander love of handpies led Bennetto O’Brien to a new home. Local farmer and Handpie Company fan, Lori Robinson, approached her with a plan. She had a building on her land in Albany she thought might be perfect for Bennetto O’Brien. The building had been home to a bank for local farmers and it was ready for something new.

“I did a walkthrough with Lori and there was something about the space,” Bennetto O’Brien says, “It was the sunniest most frigid winter day and the light coming through the windows of what is now the pastry department sold me. It was a crazy increase in square footage but I loved it. I ripped out all of the carpet myself and then, during renovations, I went on a nine

day pasty tour of Cornish, England, with my family, and I got to see where handpies come from.”

She returned and set up shop at the Albany farm bank building. When we visit, the bright kitchen is bustling as staff fill large trays of half-moon pastry, load trays into the oven and handpies into the packaging machine. At the front of the shop, freezers are filled with takeaway pies and the counter is stacked with fresh baked ones.

The magnet pull

Bennetto O’Brien studied culinary arts in Sudbury, Ontario, where she grew up, and went on to work in kitchens in Alberta, British Columbia and Ontario. After high school, she had originally set off to study pre-law but soon found herself missing the kitchen. “Cooking is all I’ve ever done,” she says. “And I needed to get back to working with my hands, with people, in a vibrant community and I am a really high energy person and the kitchen is made for that.” With her red seal certification, she was looking to take her education one step further and found the applied degree program in culinary operations at UPEI’s Culinary Institute of Canada. “No one in my family had ever been east of Ottawa,” she says, “I sold my truck to pay for my plane ticket, gave my notice and I moved to PEI.”

It was during her studies, she met the O’Brien half of her family. Owen O’Brien was a student in the culinary program and the operations class had to pitch their project to his class. In mid-presentation, Bennetto O’Brien was struck by “the big moustache” in the middle

halfway through and stopped,” she says with a laugh, “It was one of those thick Burt Reynolds moustaches.” One month later they got engaged, Bennetto finished her program and then the two married, packed the car, and drove out to B.C. where they apprenticed on an organic dairy farm, making cheese, on Saltspring Island.

It wasn’t long before the Maritimes called them back home. “If you marry an Islander there is a magnet in their hearts,” Bennetto O’Brien says. “My father had passed away and it was a wake up call to be closer to family. My husband’s family is huge so we compromised and moved to Halifax for a couple of years.” They both worked as chefs, Bennetto O’Brien working up until she was nine months pregnant. “I had my son and the magnet pull got stronger,” she says. In 2010 they moved back to the island and found a house in rural P.E.I..

“When I came off maternity leave I found work with a local potter, Island Stoneware,” she remembers. “I worked with them for two years and that was the closest I had worked with someone that entrepreneurial. Darryl and Cindy are amazing and it was pivotal for me— realizing that if you can’t find a job, you can create one.” She knew she wanted to get back into food and when

an organic farm, Crystal Green Farms, and eventually opened her own restaurant, Scapes, in Borden-Carleton. She continues to source ingredients, including loads of flour, from Crystal Green Farms. “They grow and mill wheat so it is so fresh,” Bennetto O’Brien says, “When we get our deliveries every week the bags are still warm.” She sources her handpie ingredients as locally as possible—butter from ADL, flour from Crystal Green Farms, meat from a plant in Albany.

Bennetto O’Brien has banked everything on her handpies and is getting returns beyond what she expected. It is clear from the smiles in the bakery how much she loves her team, and how stoked everyone is to be here. They are in the midst of expanding operations with a new 11,000 square foot facility in Borden-Carleton, complete with office, production and freezer space. The Albany pie bank will continue as the local retail space and with additional staff for the new facility.

Expanding to a larger facility is in part to meet growing demand, and to meet regulations so that she can ship a handpie off the island. “I can see across the bridge,” she says, “but I can’t send a pie.” While the Maritimes are

among the three provinces remains difficult. It is next to impossible to buy a Cape Breton beer in New Brunswick, or a P.E.I. handpie in Nova Scotia. “This has a huge impact on young entrepreneurs,” Bennetto O’Brien says. She has petitioned government about inter-provincial trade in the region. “We all have the same regulations but we’re not allowed to ship to each other,” she explains. “I’m going through several levels of government, investment in staffing and equipment, and this new facility, really just aiming to satisfy our Maritime market. If we were allowed to do that in our current facility we would have been doing it years ago.” Bennetto O’Brien acknowledges the handpie is a complicated product. Once you include certain ingredients—meat or dairy—regulations get complex. And the steps required to ship out of province can be a deterrent to many small business owners.

Her new expansion seems as huge an adventure as stepping through a rocky cairn and landing centuries away. Eyes wide open, and always in a ready stance, Bennetto O’Brien is excited to get production rolling in her new facility and share her love of deliciously filled pastry with the Maritimes.

The Handpie Company, Albany, P.E.I. handpie.ca

Rachel Lightfoot raises sheep and grapes in the Annapolis Valley

WORDS & PHOTOS BY COLLEEN THOMPSON

Rachel Lightfoot raises sheep and grapes in the Annapolis Valley

WORDS & PHOTOS BY COLLEEN THOMPSON

It's lambing season at the Lightfoot & Wolfville farm in the Annapolis Valley. A three-week period of little sleep and being on high alert for the keeper of the flock and modern-day shepherd Rachel Lightfoot.

It's a cold and drizzly Tuesday when I meet Rachel Lightfoot in the parking lot of the Lightfoot & Wolfville winery. Dressed in a stylish plaid raincoat and green Hunter boots, she greets me with her blithe vibe and a broad smile. You would never know that she had spent the previous three weeks running on little sleep, lifting animals more than her body weight, at times covered in amniotic fluid. It doesn't tell the story of the emotional rollercoaster. The three-hour rotation feeding schedule of twin lambs. Equal parts nerves of steel and tenderness.

She is through the busiest part of lambing season and has time to introduce me to the new cohort of thirty-three Olde English “Babydoll" Southdown lambs. All things considered, things have gone well this season. And like the nine previous ones, there have been triumphs and losses. But thirty-three new lives also feel like a gift after a difficult season in the vineyards, challenged by Hurricane Fiona and devasted by a polar Vortex in February. Lightfoot & Wolfville had just hosted the Tasting Climate Change conference the weekend before and are acutely aware of the climate change impact on farming and finding sustainable practices, which is an ongoing commitment. It's the whole reason for the sheep.

Lightfoot & Wolfville is a biodynamic farm, which means everything is done holistically and in synch with the land, the moon, and seasonal shifts. Before walking through the vineyards to meet the flock, I am handed plastic biosecurity booties to pull over my Blundstones. “The sheep are our natural mowers. They keep the weeds between the vineyard rows short, which impacts the health of the soil and eliminates the need for pesticides,” explains Lightfoot. “They start here, between the L’Acadie vines, and then we move them around to other vineyards. They fertilise as they go, and their hooves help build up the soil's microflora, making it more resilient.” Sheep in the vineyards are growing in popularity worldwide as wineries are realising the benefits and the research that points to enhanced carbon sequestration, improved soil health, and microbial biomass and nutrient content in vineyards. Healthier soil means better grapes, which ultimately means better wine.

We walk past a stall where Alder and Hartley, the two

handsome rams, are kept—separate from moms and lambs—their job for the season is done. I see up close why the moniker "babydoll" sheep has been coined for the Olde English Southdown, a heritage breed that originated on the South Down hills of Sussex County, England, in the late 1700s. The sheep are smaller than most, stocky, with short legs, one white and the other brown with a black face. “We are attracted to heritage livestock breeds. Traditional breeds of a bygone era that were common before industrial agriculture became a mainstream practice bred out many original traits and forced these breeds to near extinction,” says Lightfoot. Olde English Southdown Sheep retain essential traits for survival and self-sufficiency, like a strong maternal instinct and natural resistance to diseases and parasites.

“We were initially attracted to the Olde English Southdown's smaller 'miniature' stature, which makes them particularly well suited for vineyard grazing. Then, we learned of their extreme hardiness, highquality fleece, and the unmatched tenderness and flavour of their meat, so they are the perfect fit for our multifaceted farm and winery operation,” says Lightfoot.

The steel barn is a few meters away. The floor is covered in straw and open on one side so that lambs and ewes can wander in and out. A smell of hay, wet wool, and lanolin hangs in the air. Lightfoot has sectioned off a stall in the corner for Dani and her newborn lamb twins. The ewe has had a rough couple of weeks with lambing disease and is unable to feed her lambs. For a while, it was touch and go. “Things have eased up a bit. I had to bottle-feed these two every 3 hours, but now I'm down to about three feeds daily. At ten years old, Dani is one of our oldest ewes, and she developed a condition called pregnancy toxaemia. It's the first time I've dealt with this condition in over ten years of lambing,” says Lightfoot. “It's a metabolic disorder that can affect pregnant ewes during late gestation and is more common in ewes carrying multiple lambs. It is a condition characterised by a negative energy balance, where the ewe's energy requirements exceed its energy intake.”

The condition can be potentially life-threatening for the ewe and her unborn lambs. During late pregnancy, the energy demands of the growing lambs increase, especially during the last six to eight weeks before lambing. If the ewe doesn't consume enough energy to meet these increased requirements, her body uses fat reserves to compensate for the energy deficit. But, the excessive

breakdown of body fat leads to the accumulation of ketones in the blood, resulting in pregnancy toxemia. As the condition progresses, ewes become unable to stand, appear depressed and eventually fall into a coma. It's just one of many challenges Lightfoot has handled this lambing season. And mishaps are part of every season. And in the words of poet and environmentalist Wendell Berry, “When you are new at sheep-raising, and your ewe has a lamb, your impulse is to stay there and help it nurse and see to it and all. After a while, you know the best thing you can do is walk out of the barn.”

There was the ewe who rejected her lamb and would headbutt him whenever he came close. Two breech births required careful intervention to ensure the lambs were delivered safely. There were twins who both had their heads twisted behind their back legs. Sadly, the lambs were lost. But the triumphs and rewards are there too. Dani and her lambs are thriving. Something clicked, and the rejected lamb was finally accepted by his mama. He has filled out beautifully and has been selected by another local farm to become their future flock sire. And in a few weeks, the sun will shine, the buds on the vineyards will burst, and that feeling of exhaustion will turn to sheer joy.

Lightfoot's family has been working on this land for four generations. Rachel, one of five daughters, has chosen to follow in her grandmother's footsteps. "My great grandmother was farming organically and biodynamically long before we gave those things names,” says Lightfoot. “My father grew up here learning from my great grandmother who farmed in a way that would be considered natural farming today— composting, shunning chemical inputs, harvesting and planting according to the lunar cycle. To her it was just the commonsense way to care for your land and feed your family.”

Rooted in the philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, the biodynamic philosophy guiding Lightfoot & Wolfville looks at the farm as a whole, living organism. “At its core, biodynamic farming is a holistic vision of the farm as an integrated, whole, living ecosystem,” says Lightfoot. “This organism comprises several interdependent elements: fields, forests, plants, animals, soils, compost, people, and the spirit of place. Biodynamic farmers work to nurture and harmonise these elements, managing them in a holistic and dynamic way to support the health and vitality of the whole.” Animal husbandry is a crucial requirement in biodynamic farming and is central to providing precious manure important for increasing

soil fertility. Diversity in animals is also beneficial, with each animal bringing a different relationship to the land and unique quality of manure.

Over the last few years, Lightfoot & Wolfville have added several heritage breed livestock (Olde English Southdown Sheep, Jersey x Wagyu cross Cattle, Berkshire cross, and Mangalitsa Pigs), each playing an essential role within the whole-farm system. “The sheep act as lawnmowers and live within the vineyard at certain times of the year,” Lightfoot explains, “grazing the weeds and cover crops and providing organic fertilizer, and the pigs happily forage on our leftover grape skins and vegetable garden scraps. They clear the thick brush through their innate rooting behaviour, promoting airflow and helping with mildew prevention... Here, on the land unsuitable for viticulture, we produce forage for the livestock, such as hay and silage, which they eat throughout the winter months when they no longer grazing on pasture.”

We leave the barn and head outside into the enclosed lambing paddock, like a lamb playschool. It's hard not to go weak in the knees at the sight of thirty lambs frolicking, and the energy and pure joy is palpable. We stand quietly amongst the ba-a-ing, prouncing, frolicking, climbing, suckling, and napping. Lightfoot knows the names of all the ewes and all the stories that accompany them: Lily, Juniper, Indigo, Hazel, Gemini, Daisy, Daffodil, Junebug, Clover, Iris, Chamomile, Julep, Lavender, and Lilac. “You must have a gentle presence,” Lightfoot assures me as I walk among them, taking photographs, “the lambs are usually very skittish, but they are so calm.” They do bring a sense of calm, and I could happily hang out with them all day.

“I've learned some simple and vital truths through my sheep,” says Lightfoot. “Through their annual cycles of lambing, weaning, shearing, pasture rotations, and vineyard grazing, they help keep me connected to the seasonal rhythms and vibrant nature of the farm while teaching me resilience, discipline, and hope.”

11143 Evangeline Trail, Wolfville, NS lightfootandwolfville.com

Page 46: A lamb at the farm

Page 49

top: Rachel Lightfoot with her flock

Page 49

bottom: Sheep amongst the grapevines

Page 46: A lamb at the farm

Page 49

top: Rachel Lightfoot with her flock

Page 49

bottom: Sheep amongst the grapevines

Cocagne Country Colours revives natural dye, together

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

Last night’s rain drips from the leaves of the apple trees that border Marie-Claude Hébèrt’s garden in Cocagne, N.B.. Hébèrt is leading us along rows of sunflowers, past the yellow buttons of dyer’s chamomile and the oranges of marigolds, to a seemingly unadorned plant that is just emerging from its straw mulch. This is madder—a plant that hides its beautiful secret underground. The roots of this plant can grow to a metre in length and have been prized for thousands of years for how they impart hues of red—from deep mulberry to terracotta—to natural fibres of all sorts.

“We use the petals of most of the plants in our dye garden,” Hébèrt explains, “but for madder we use the root. It grows a great red-orange root, that’s why we have the raised bed so we can try to catch that.”

Hébèrt came to this south east corner of N.B. with an interest in colours that started twenty years ago, with paint pigments. She had explored the Atlantic coast, working on organic farms, when she and her partner, a biologist, found a parcel of old farmland and renovated its farmhouse. They are raising their children here, next to a garden of colour. “When we moved here,” she says, “I started taking textile dye classes and then a group of us really got into it.”

Couleurs du Pays / Cocagne Country Colours—a group of growers, farmers, artists, knitters and spinners, and scientists, in Cocagne, who grow and forage plants and mushrooms, raise sheep, grow flax, and spin and dye local wool and linen. They came together with a collective interest in learning the age-old process of natural dyes, together.

With a grant from the GDDPC (Groupe de développement durable du Pays de Cocagne), the group started their local natural dye initiative in 2019. In the context of the pandemic, this might seem like bad timing but, as Hébèrt explains, “it was the best thing for us. We could do our own things during the winter months,” she says, “and then come together in the summer for socially distanced workshops.” Their collective has grown into a tight-knit, community-based project—the kind of program the GDDPC, with its focus on sustainable community development, fosters. “The pandemic really cemented our passion for the project and we really got to know each other,” Hébèrt says.

Typically the dyeing happens at the big barn at the Marcel Goguen Farm, an historic family farm in the village of Cocagne where Bernadette and Marcel Goguen, scientists, farmers and natural dyeing enthusiasts, grow apples and vegetables. This summer, barn renovations

mean dyeing is happening here in Hébèrt’s greenhouse. She leads us past a large pot of water that sits outside, in through the low door of the greenhouse where more pots await, one steaming with orange plant material and another that looks like wool soup. When preparing to dye wool or linen, Hébèrt first places the wool in a pot of water with alum—a mordant—which helps to fix or set the colour. Once rinsed, it can rest, or be placed in the dye pot right away.

Hébèrt strains the plant material—marigolds—from the dye pot and dunks in a mordanted skein of wool. Instantly, it begins to take on a hint of red. “It will change to more green or even yellow,” she explains. “We’ll leave it overnight, that’s when the colour really sets.” By morning it will be golden.