6

NO.

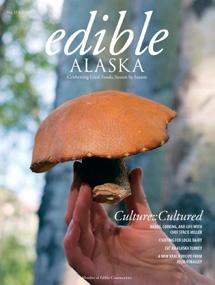

SPRING 2023 Member of Edible Communities Learning Curves edible maritimes the land ~ the sea ~ the people ~ the food

Affordable, versatile and local! Make your day EGGstra special with Maritime Eggs! nsegg.ca eggspei.ca nbegg.ca Visit the Egg Farmers in your province for great recipes and more.

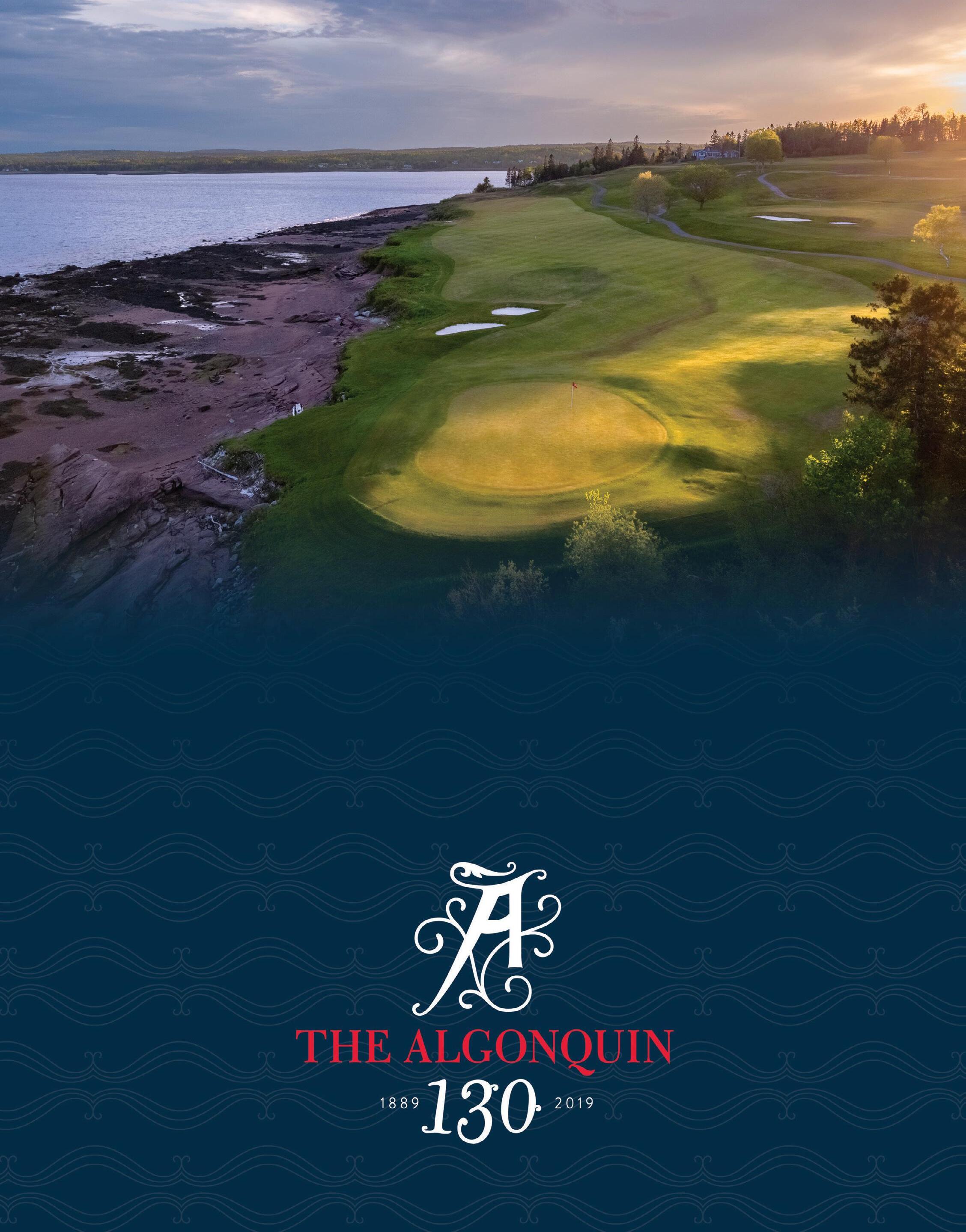

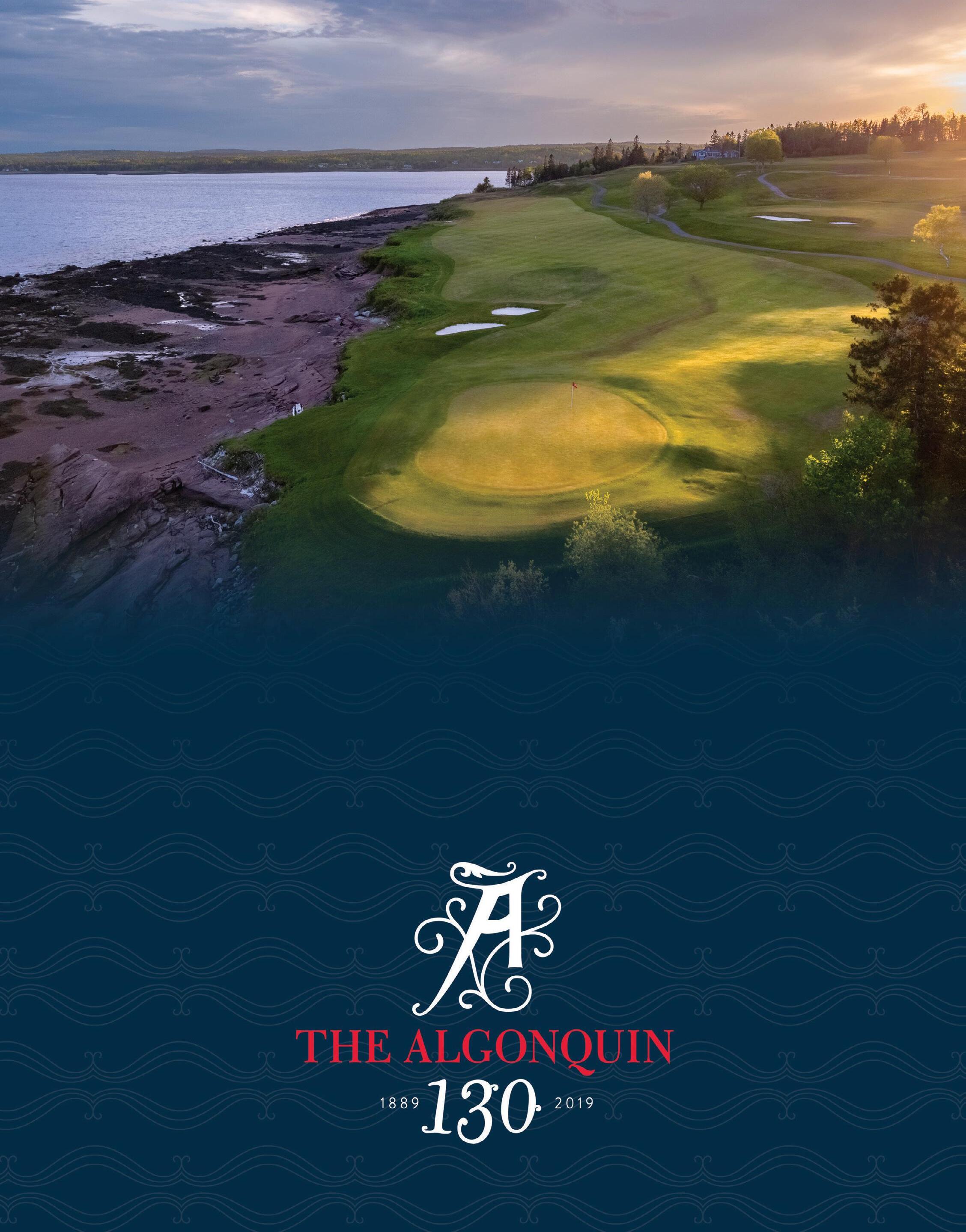

Oh, and did we forget to mention as spectacular as any course in Canada? algonquinresort.com

506-488-3161

AN UNFORGETTABLE SEASIDE EXPERIENCE

Custom Design

Quality Craftsmanship

TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 HELLO FROM US 5 MAWI'OMI 6 SPRING IN THE INTERTIDAL ZONE Follow Nick Chindamo down to the beach 7 LA BELLE ÉNERGIE ET UN BON CAFÉ Louise Fyfe on keeping the coffee coming 10 SHAKER'S UP Brix Experience is mixing up Moncton's food and drink scene 16 THE RADICAL ACT OF COOKING TOGETHER Ten chefs get creative in An Island Collective 24 PORT OF CULINARY CALL Chef Jason Lutes on coming home, and ramen 30 CONSIDER THE KITCHEN Simon Thibault explores what cooking means to him 33 GENERAL STORE REVIVAL Camelia Frieberg's Chicory Blue 38 CHICORY BLUE FIG GALETTE A recipe from Camelie Frieberg 40 WILD ROOTS Chef Kylie Brownell and her sweet Tusket restaurant 42 BIENVENUE À CIELO Emilie LeBlanc and Pat Gauvin offer up a taste of local 47 SPRING ZING A recipe from us 48 CORN SOUP IN WABANAKI Cecelia Brooks on Nixtamalization and two recipes 50 OLD CHARM, NEW TWIST Chef Kim Martin making magic in Sackville Happy reading! On the cover: Chefs Adrianna Remlinger and Lexi Orbanski from An Island Collective Photo by Al Douglas This page: Spring blossoms by Dave Snow

In this issue, you'll find stories of people who are pushing themselves out of their comfort zones and reconnecting with creativity—and each other—in the kitchen or around a big table. They inspire us to get out there and try something new. So let's put on our waders and jump in.

We dedicate this issue to our dear friend Mike Troyer, who was a great lover of food, laughing and sharing his table with family and friends. Two years ago, he and his wife Lindsay moved into a farmhouse on a hill in Antigonish County. Mike then became an orchardist, tending to his apple and pear trees with a view of the Northumberland Straight. He was one of our biggest supporters. We, along with his family and friends, will miss him.

Yours in supporting local, Sara & Dave

above:

Photo next page: Reindeer moss, wild mushrooms, and cranberries - “the taste of a PEI bog”, Chef Nick Chindamo, An Island Collective

edible maritimes

CO-EDITORS & DESIGNERS

the land ~ the sea ~ the people ~ the food

Sara & Dave Snow CONTRIBUTORS

Haqq Brice, Cecelia Brooks, Jennifer Campbell, Nick Chindamo, Amber d'Entremont, Al Douglas, Camelia Frieberg, Inda Intiar, Adam Myatt, Simon Thibault Shakuntala Vadakkath-Woolley, Peggy Walt

THANK YOU

To all of you — our readers, advertisers, contributors, our friends and family, for supporting local and independent print media. We couldn't do it without you!

SUBSCRIBE

edible Maritimes is published 5 times a year. Subscriptions are $28 and available at ediblemaritimes.ca

FIND US ONLINE ediblemaritimes.ca

instagram.com/ediblemaritimes

ADVERTISE WITH US hello@ediblemaritimes.ca ediblemaritimes.ca 506-639-3117

PUBLISHERS

Sara & Dave Snow

Steadii Creative Inc

No part of this publication may be used without written permission by the publisher. Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings and omissions.

If, however, an error comes to your attention, please accept our sincere apologies and notify us.

Thank you, © 2022 Steadii Creative Inc. All rights reserved.

Edible Maritimes is proudly printed in Canada on paper made of material from well-managed, FSC®-certified forests, from recycled material and other controlled sources.

Through 1% for the planet we contribute one percent of our revenue to environmental non-profits.

Read it, love it, share it!

Please reuse and redistribute this magazine - read it again and again or pass it on!

4 edible MARITIMES

Photo

Spring Croci by Dave Snow

Photo by Al Douglas

mawi'omi

Mi'kmaw for gathering

Visit L'nuey at lnuey.ca/education/ to learn more about this word and the importance of mawi'omi.

We respectfully acknowledge that we are in Wabanaki territory, on the unsurrendered and unceded traditional lands of the Wolastoqey/ Wəlastəkwey, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy peoples, who have stewarded this land throughout the generations. This territory is covered by the Treaties of Peace and Friendship which the Wolastoqey/Wəlastəkwey, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy peoples first signed with the British Crown in 1725 recognizing Wolastoqey/ Wəlastəkwey, Mi’kmaq and Passamaquoddy title. We stand with them in their efforts for land and water protection and restoration, and for cultural healing and recovery.

Edible Maritimes

Spring in the intertidal zone

Nick Chindamo takes us to the beach

Iparked my car at the back of an old campground on the North Shore. To get to the beach, you’ll push through a dense patch of Bayberry to a set of steep dunes, all of which are infested with a seaside variant of Poison Ivy.

I visit this beach once a year—in the early spring—when the only signs of this irritating plant are the dried out stems of the previous year, and the tiny new shoots that poke up out of the cold sand. As I climb the sandy hills—I don’t watch my step.

The hills boast extravagant views of the Gulf of the St Lawrence. It’s in places like these that I forget what I came for in the first place, and lose myself—for hours on end—in the rolling waves and intricate landscape. I took in the view from the top, and stumbled along the sandy slopes toward the rocky cove in the distance.

The tide receded as I moved along—and left remnants of sea-life in its tracks. Wracks, Locks, and Sea Mosses flaunted their new Spring growth, and I happily filled my bag (and my mouth) with their display.

Tender Bladderwrack tips that snap in your mouth like a briney, canned Lupini bean. Pelvetia—that chews like a gummy candy. Sea oak—like a tender lettuce. Sea snails. Whelks. Urchin. If you’re into textural (and internal) exploration—this place is a phenomenon.

As I casually hopped along the rocks—mouth full of seaweed —I thought about what this spot would’ve looked like 100 years ago. 1000 years ago. 10,000 years ago. “Did it look the same? Smell the same?” I picked up a small Oyster, shucked it from its shell, and slurped it back. “Did it taste the same? It couldn’t have, right?”

I climbed up onto a small overhang and looked down into the water - where thousands and thousands of empty shells covered the ocean floor. I tossed mine in, and smiled as it floated down and lost itself in the mix.

“All I know…”, I thought to myself, “is that if I were here, in this spot, 10,000 years ago, I’d probably be doing the same thing.”

Nick Chindamo is a wild food enthusiast, avid outdoorsman, chef/storyteller in Epekwitk (Prince Edward Island)

Pelvetia shoots

Brined Badderwrack, like salty Lupini beans

Pelvetia shoots

Brined Badderwrack, like salty Lupini beans

La belle énergie et un bon café

Louise Fyfe on running the busiest little vegetarian café in northwestern N.B.

WORDS BY SARA SNOW

PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

It was an early Saturday morning, and Louise Fyfe was busy in her café on Canada Street in Edmundston. The café was closed when there was a ring at the door. She looked up from her prep work behind the counter to see a very tall man she didn't recognize. This isn't unusual. Fyfe estimates that almost 90% of her customers are travellers, people visiting the area or passing through on their way to other parts of the Maritimes, Quebec, or Maine. The other 10% are locals.

“I opened the door and this guy, he's a really big guy,” Fyfe tells us, “he says ‘You got kombucha here?’ and I'm like ‘Ya, of course.’ Turns out it’s Georges Laraque!” She says with a laugh. “You know, he’s vegan and he had just written this book he was promoting and he asked around town for a vegan spot. So we opened that Saturday morning just for him.”

An early morning encounter with a former-NHL player is nothing out of the ordinary for Fyfe and her busy café. Today, it's a bright Thursday morning and she opened the shop only 30 minutes ago. Already, most tables are full and there are two people in line at the counter, placing orders to go.

Fyfe moves to the table of three next to ours and takes their orders. These three are locals, and regulars. “This is a very special place,” one tells us, “with good coffee and good food.” Fyfe opens Wednesdays and these three are here every week. “The breakfast sandwich is délicieux ,” another tells us.

Café Lotus Bleu International, in downtown Edmundston, is a few hundred metres from the U.S. border and a quick drive off the Trans Canada Highway.

Fyfe grew up in Edmundston and, after high school, left to travel. “I travelled for ten years tasting everything and I had this idea of a coffee shop,” she says. “I never thought I would do it and now I've been doing it for almost 15 years. I wanted to have a place where people could get a really good coffee or tea.”

She carries Epoch Chemistry coffee from Moncton and her shelves are filled with her own loose-leaf tea blends. She stocks a refrigerator daily with freshly prepared take-away meals, soups and sweet treats. Her dishes are inspired by vegetarian cuisine from around the world and her Soupe Dhal is one of the most popular items. Her overflowing notebooks of customer messages

8 edible MARITIMES

include comments such as “Charmant!”, “Wow, quelle belle découverte!”, “Love the vibe!”, and “What a gem!”

Fyfe zips behind the counter to prepare an espresso for a customer. Brewing a cup of coffee is one of her favourite things to do and it's clear in the delicious coffee in our cups. She has already brewed countless cups this morning and it's only 9am. She disappears into the kitchen to prepare sandwiches for another table.

Fyfe tells us “sometimes the busy-ness is unsustainable but it is hard to find staff.” Staff shortages are a common theme throughout the Maritimes with provinces reporting surging job vacancies in hospitality and tourism sectors in 2022.

Monique Nadeau joined Fyfe last year and has been invaluable behind the counter, taking and prepping orders from customers. She takes an order from a customer and waves hello to another. He's from Madawaska, Maine, just on the other side of the bridge, and is picking up his usual order for his crew on his way to work.

Fyfe has also just hired someone new to help her in the kitchen and she's feeling optimistic. Her winter holiday is approaching and she'll close the café for some renovations.

Fyfe originally named her business the Blue Lotus Floating Tea House. “I imagined my life always rolling,” she says. “I'm thinking of a food truck next because if you're going to be by yourself in the kitchen you may as well be in a truck. You can go wherever and your business is with you.”

Her café is full of little bites of wisdom—from the stack of books and magazines by the front door, to the messages on the colourful chakra flags above her counter, to the Book of Answers she keeps on the counter—Fyfe has filled the space with inspiring thoughts to uplift anyone who comes in.

As Fyfe looks to the year ahead, she says “it's up to us, we have to invent the next phase.”

Café Lotus Bleu International

52 Ch Canada, Edmundston, N.B. cafelotusbleu.ca

Shakers up!

Brix Experience is stirring up

Moncton’s food & drinks scene

WORDS BY INDA INTIAR

PHOTOS BY HAQQ BRICE

The bright café at the corner of Moncton’s Bonaccord and St. George Streets may be the first thing that visitors to Brix Experience see. But there’s much more inside the 101-year-old, fourstorey building.

Past the door, at the back of the café, await a bar, a kitchen, private event space and a modern temperaturecontrolled wine and spirit cellar.

I'm here with my partner to try out one of the cocktail classes. We’re fans of the Netflix mixology show Drink Masters, and we're eager to learn more about the flavours that go into various drinks.

At 6 p.m. we join nine other people in a beautiful dimly-lit room, painted dark green, behind the café. In the middle of this room—a bar with a gold-accented tile backsplash. Mixologist Fernando Campos and his colleague Brenda Caverly welcome us.

For this session, Campos leads the group as we learn how to mix three rum-based cocktails: the piña colada, the mai tai, and the knickerbocker. The bar is also stocked with non-alcoholic spirits for those who prefer them.

Brix Experience owner David Ford, a Moncton entrepreneur and pharmacist, says not only is there a demand for non-alcoholic offerings, it allows nondrinkers to participate. “For example, my company here is made up of many different nationalities, and you can’t expect people to have the same preferences,” he says. “This is for everybody.”

Sure enough, one guest opts for a non-alcoholic option.

In the class, we're split into three groups across four stations that are stocked with everything we need to make cocktails, including syrups and juices made fresh by Campos himself. My partner and I are joined by a woman, who has come with two family members.

We pick a glass for each of our cocktails. My favourite—a clear cup in the shape of a pig that I chose for my last drink.

At our stations, we spend some time mixing ingredients with direction from Campos. He checks in on folks from time to time to make sure we are all on the same page.

Then our shakers are up. There is almost a rhythm going on in the room that you could dance to.

After the first drink (and a lot of shaking), a sense of camaraderie begins to build in the room. Staff break the ice further by asking guests to introduce themselves. Turns out, a few people are connected to the space in various ways—through working in or on the building.

It's a lot of fun connecting with new people as we learn, and enjoy our creations. We joke about whether putting three ounces of Triple Sec in one of the cocktails would be too much. “It is called Triple Sec,” I say.

In between each drink, staff serve hors-d'œuvres like roast beef crostini and bite-sized samosas. Guests chat with each other, and the staff.

Campos, who recently moved to Canada from Chile, is passionate and knowledgeable about his craft. Besides teaching the cocktail classes, he also creates recipes and develops programs for the classes.

Ford says it’s great that Campos’s knowledge can be shared with New Brunswickers. “It’s a specialty,” he says. “And now that I’ve taken a few classes, I know how to impress somebody,” he jokes.

Brix began with Ford’s dream of opening a coffee shop. Six years ago, he saw an opportunity and bought the building on 245 St. George St. Though his businesses are all in the healthcare sector, he’s decided to step into the food and drink industry.

“I’ve always wanted a third-wave coffee shop,” he said.

The third-wave coffee movement emphasizes the quality of the beans. Brix’s café carries beans from Vancouverbased roasters 49th Parallel, which focuses on sustainable sourcing and technologically-advanced techniques. The café also sources pastries from CoPain Artisan Bread Company, a bakery in the neighbourhood.

Ford is not the first person to put a café in the building that was once home to the Loyal Orange Lodge of Canada. Popular Moncton coffee shop Café Clementine started there, before moving to Elmwood Drive. “So, I’m just putting coffee back in this corner,” says Ford.

The building’s upper floors are used as a contact centre for one of Ford’s businesses, and high-end lofts for rent. But to fill the rest of it, Ford took inspiration from his business travels around Canada. He envisioned offering various food and drink experiences under one roof.

12 edible MARITIMES

Previous page: Inda with a knickbocker

Above top: Mixologist Fernando Campos at the bar

Above bottom: Students learn the art of the shake

In addition to the café and cocktail classes, Brix also offers culinary classes, wine and spirit tastings, and private event spaces. They can be booked via Brix’s website.

“Part of our goal is to educate people, about spirits, about wine, about beverages and about food. That’s why it’s called the experience centre,” he says. “We want to make sure it’s an experience they’ve never seen before, that it’s cool and memorable.”

Brix’s team of experts shape those experiences. Besides Campos, beverage manager Marcel Richard offers expertise in wines, while Chef Regan Byers, who recently moved from Uxbridge, Ont., heads the food section.

Since opening in mid-October, 2022, Ford says the reception has been overwhelming. Brix was fully booked for the holidays and Ford is building out its team.

Ford says he wants Brix to showcase products from the Maritimes as much as possible, with plans to work with chefs from around the region and to host events promoting New Brunswick oysters, distillers and breweries.

Ford says customers often tell him they don’t feel like they’re in New Brunswick when at Brix.

“But you are in New Brunswick, and we have these things for you,” he says. “You just have to look around and be open.”

Brix Experience

brixexperience.ca

245 St. George St, Moncton

Inda Intiar is a storyteller at heart and loves writing about cultures and travels.

Haqq Brice is a photographer, based in Moncton, who enjoys photography, poetry and cultures.

Top: The bar at Brix Experience

Bottom: David Ford at the coffee bar

Bear River & Annapolis Royal sissibooco ee.com

Morning coffee with friends, market-fresh fare to fuel your adventure, or a hearty meal at one of our homegrown restaurants.

You’ll love our local flavours. hampton.ca

14 edible MARITIMES

Nestled on the banks of St. Peters Bay, Mysa Nordic Spa & Resort is an 18-acre patch of paradise. Prince Edward Island’s first Nordic spa is a serene space designed for relieving stress, immersing yourself in nature, and invigorating the senses.

We offer a wide range of spa and relaxation services including thermal baths, essential oil steam rooms, cold water plunges, a Finnish sauna, meditation sessions, and massages.

Enjoy top-tier food and beverage at our onsite restaurant, then settle into one of our seventeen water view accommodations to watch the sunset.

SPRING 2023 15 MYSANORDICSPA.COM

The radical act of cooking together

Ten chefs come together for An Island Collective

IN CONVERSATION WITH AN ISLAND COLLECTIVE

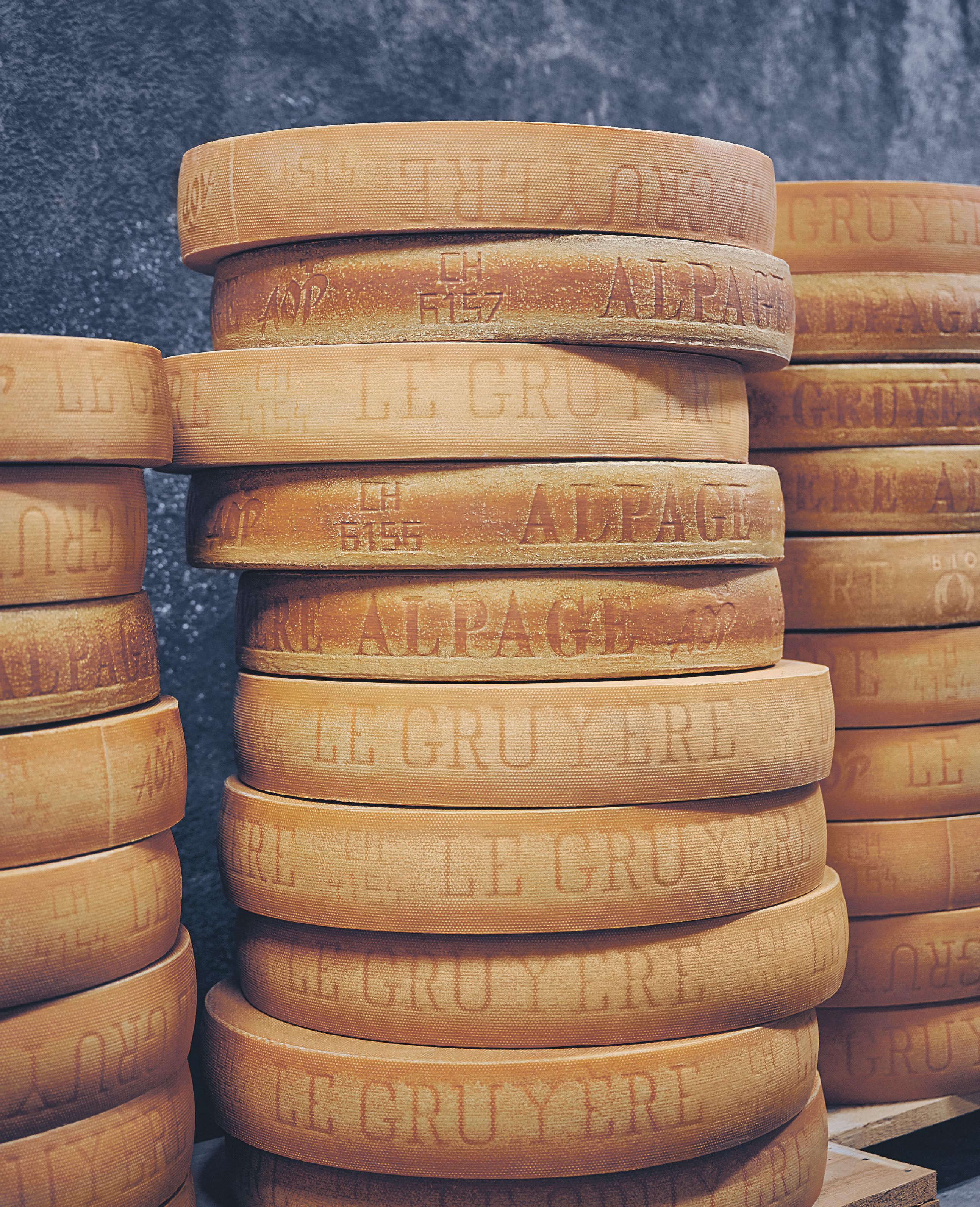

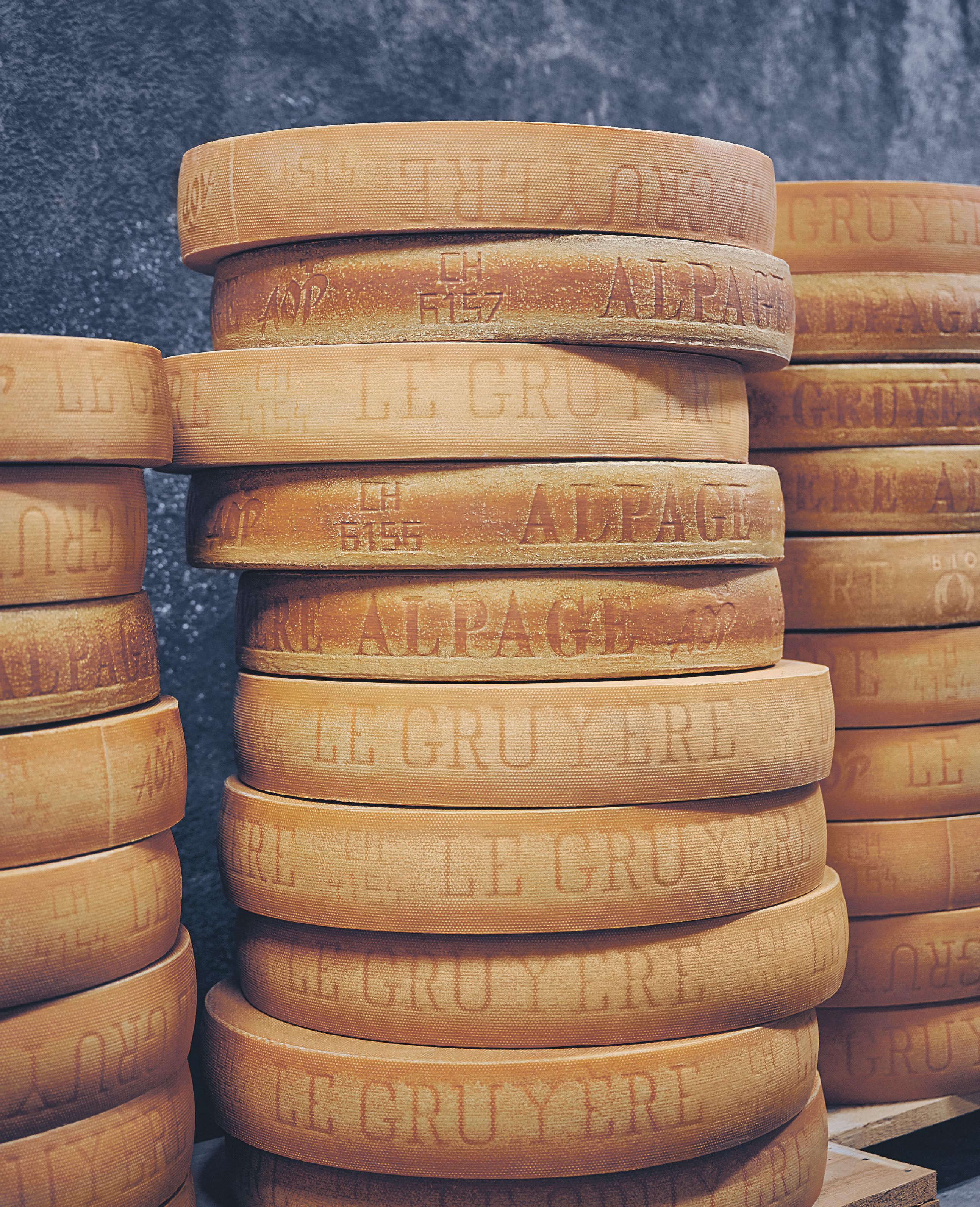

On a mid-December afternoon, ten chefs made their way to Charlottetown’s Founder’s Hall to prepare a meal for 33 guests. They carried preserves and pickles, dried herbs and sprouts, local honey and butter, herbs, mosses and fungi foraged from the forest or the shore, and meats, seafood, and greens they had procured from local farmers and fishers. The event—An Island Collective. Chef Nick Chindamo, wild food enthusiast and engineer of extra-ordinary dining experiences, partnered with Chef Jesse MacDonald, chef instructor with the Culinary Institute of Canada (CIC), to coordinate their second Island Collective dinner event.

Island photographer, and lover of all-things butter, Al Douglas was there to capture the evening. He joins us and the chefs to talk about the dishes they brought to the table and the experiences they left with.

Chefs from left to right: Adrianna Remlinger, Stephane Levac, Jason Mullin, Lexi Orbanski, Alex Seaborn, Adam Sweer, Nick Chindamo, Leslie Flynn, Jesse MacDonald

Missing from photo: Brittany Boothroyd

Chefts in training:

Alec Fyfe and Kabir Singh

Michaela Power (in grey)

Mateo Arsenault (grey toque)

Seated in front: Yasha Rawat, Kylie Atengco and Jakob Gosbee

SPRING 2023 17

PHOTOS BY AL DOUGLAS

The Chefs

Chef Adam Sweet

Sweet, originally from New Brunswick, came to Charlottetown via kitchens in Alberta. He left restaurant work to set up shop as a knife-sharpener and soon established the well known Cook’s Edge in the heart of the city. He and his wife are raising their sons in a veggie-forward way, enjoying the occasional roast-beast over a campfire with friends. “The real way to experience the island is to get into the countryside,” Sweet says.

Chef Alex Seaborn

Seaborn left Toronto, and a career in restaurants, with his partner Kat and set out for a new life on the Island. He joined the Humble Barber in Charlottetown and last year, as a side hustle, he and Kat launched Seaborn Snacks, a culinary popup and catering company. Curious how to cook a beef heart or whip up some homemade ricotta? Seaborn is your guy.

Chef Adrianna Remlinger

Originally from Saskatchewan, Remlinger studied culinary arts and set off for kitchens in Montreal. It wasn’t long before she landed at the Island’s Inn at Bay Fortune where she is now honing her butchery and charcuterie skills—“I find animal butcher exciting,” she says with a smile. In the offseason, she is enjoying quiet island moments, nettles, and studying holistic nutrition.

Chef Brittany Boothroyd

Following graduation from CIC, Boothroyd worked in kitchens in the Alberta Rockies before setting off to travel and cook. She took her passion for vegetables to Melbourne, Australia to immerse herself in one of the world’s most vegan cities, returning to the Island to establish Wild Kitchen, where she offers veggie-forward culinary classes. She and her husband are expecting a wee little chef this spring who will most likely love squash.

Chef Jason Mullin

Mullin studied culinary arts in Toronto and has explored food and cultures everywhere from Chile to Vietnam, Australia to India, Charlottetown to Churchill, Manitoba, extensively documenting his travels and food guides, eventually joining the team at Inn at Bay Fortune in 2018. He is currently diving deeply into the world of fermentation, misos, soy sauces, while making the most of the off-season with his partner— Chef Adrianna.

Left top: Seaborn tops his dish off with his ricotta

Left bottom: Chindamo's Preserved Pear with Blackcurrant Leaf

Right top: Mullin's Chicken, Wild Cranberry and Koginut Squash

Right bottom: Chindamo, Remlinger and Seaborn plate dishes

Chef Jesse MacDonald

MacDonald is an Islander through and through. He grew up in Launching, on the eastern tip of the island where his parents were lobster fishermen. He got his first restaurant job washing dishes when he was 14 and, after several years of kitchen jobs and lobster fishing, he enrolled in the CIC’s culinary arts program. Now over a decade later, he is the executive chef at The Wheelhouse and chef instructor at CIC. Seven of his students joined in the Island Collective dinner, as servers and assisting in the kitchen.

Chef Leslie Flynn

Flynn is also an Islander. He's from Georgetown and started his kitchen career as a dishwasher—at the age of 13. He roomed with MacDonald during culinary school and is now chef at Charlottetown’s Merchantman where seafood is his game. When he has time to cook for himself striped bass is at the top of his list and secret ingredients from his garden and his grandmother's kitchen. His favourite thing—heading out on a tuna boat is his idea of the best time.

Chef Lexi Orbanski

Last fall, Orbanski had dinner at Oxalis Restaurant in Dartmouth, N.S.. She’s now their pastry chef! She grew up north of Winnipeg and travelled east for CIC’s pastry arts program, working as pastry chef at the Inn at Bay Fortune after graduation. She makes exquisite desserts called Smoke in the Woods and Not a Mushroom. At December’s Island Collective, students watched in awe, the faint whisper of “what the --?!”, with her every perfect rocher of ice cream.

Chef Stephane Levac

Nova Scotia forager and Chef, Levac was drawn to cooking by necessity and intuition. He is Ojibway and grew up in the northern Ontario town of Sturgeon Falls and Ottawa. While living in Ottawa, he and his wife Sarah developed a passion for cooking for large groups. They moved to Annapolis Valley, where Sarah grew up, and leaned into this passion, starting a catering company, doing pop-ups at local vineyards and filling the bagel gap at the local market. He is now head chef at Maritime Express and spends as much time as he can foraging in the forest or on the shores of the Bay of Fundy.

Chef Nick Chindamo

Chindamo came to the Island four and a half years ago to work at the Inn at the Bay Fortune and follow his dream of being a chef. What he found, instead, was the chance to get to know himself as a cook. “I deepened my passion for food, and for wild food,” he says, “and I took it in a different direction. Now I run parallel to the restaurant industry.” Chindamo’s path may seem parallel, but the way it criss-crosses with the restaurant world is opening space for new pathways that head deep into the wild world of creativity.

join the second in their Island Collective series. The guidelines—100% local, zero waste and get creative. As with the first dinner, all proceeds would be donated to a local non-profit.

“We wanted to give each chef some exposure,” Chindamo explains. “They are all super friggin' talented.”

“And we wanted to keep things very local,” MacDonald says. “The cool thing is everyone ran with their own flavour profile.”

In developing her dish Orbanski says, “At first, I had to really think about my ingredients because I wanted to keep everything local to PEI. So I chose Juniper, wildflower PEI honey for the gel on the plate and the mousse.”

An Island Collective dinner is not a ten-course dinner but a dinner of ten dishes, each created by a different chef. “Everyone was cooking their own dishes,” Chindamo explains, “so when building the menu I wanted to be sure an overpowering flavour wouldn’t run into the next dish.” He assigned himself a couple of palette cleanser dishes—including an acidic pear dish. “I sliced the pears really thin,” he explains, “compressing them in a vinegar made from blackcurrant leaves, a little blackcurrant oil and blackcurrant gel, to hit the guests with an acidic burst of flavour and clear their palettes.”

“The theme, a taste of nostalgia,” Chindamo explains. “was interpreted differently by everyone.”

“When Nick suggested the theme, it was December,” Remlinger says, “and I thought Christmas—we always made tourtières with my mom. She’s French Canadian and I can remember loads of them on the dining room table. So I thought how could I take that and refine it.”

“The nostalgic part for me,” Sweet says, “was braising and butchering which is what I used to do a lot in my career as a chef. I also don’t get to hand roll pasta very often with two young boys at home so I made an egg yolk pasta and one of the apprentices [CIC students] made orchetti/cavatelli noodles. I turned all of the bones into a rich jus and we did braised lamb with the jus and orchetti with lots of cheese from New Glasgow. Some nice braised meat with orchetti and cheese. It really reminded me of being in the industry.”

Going full rip

Chindamo, who the Globe and Mail just named as one of Canada's next star chefs, is keen to push himself and other chefs out of their comfort zones. The Island Collective has grown out of another of his projects where he invites chefs “to bring their food scraps and we create a ten course dinner with only those scraps. I don’t promote it because it’s just to explore their own creativity,” he says, “and hopefully head back to their

20 edible MARITIMES

restaurant with new ideas on how to reduce food waste.” Similarly, the Island Collective is meant to engage chefs in pushing the boundaries of their own cooking.

“There weren’t any flavour profiles that we thought wouldn’t work,” Seaborn explains. “We could be more creative while keeping it grounded. It wouldn’t matter what these people were serving because everyone is trained well enough that they will make it work into something that is really supremely delicious.”

“It was the opportunity to be yourself unabashedly,” MacDonald adds. “It’s for you so you can really explore what a certain ingredient means to you or a certain technique.”

Levac agrees. “The Island Collective is a great opportunity to showcase what you don’t normally in the restaurant,” he says. “I wanted to feature something that I forage because I often can’t go full rip with foraged ingredients in the kitchen. I like working with game meats but we can’t get our hands on it very often. So I did rabbit terrine with wild nuts and brushed with a fermented fir cone syrup and a juniper custard. I made an apple butter, and a black chanterelle infused cracker with my own fennel salts from the tidal pool water.”

“I do have creative freedom in the kitchen,” Mullin says about his work, “but the Island Collective is a way to break out of the typical dinner and really harness what you want to do.”

In addition to pushing it creatively, each chef had the rare opportunity to present their dish to the guests. “Everyone is waiting for the moment to happen,” Douglas explains, “and, whether it was Alex, Adrianna, or Jason, or any one of the chefs, the guests were hanging on every single one.”

“I was the first course so that was pretty nerve-wracking,” Remlinger says. “I introduced myself and shared my tourtière story, telling them we made tourtières for the post office lady, the bus driver, all the teachers at school. I filled each pastry shell with ground beef, toasted black walnuts and oats in lard—we always had a very fatty oatmeal stuffing as a child—and peas from my garden, island black currants and the secret layer of caramelized onions on the bottom.”

Left: Chindamo and Orbanski with crispy moss.

Top right: Sweet rolling orchetti with Michaela Power Top bottom: Orbanski's Juniper, Buttermilk, and Wildflower Honey

Left: Chindamo and Orbanski with crispy moss.

Top right: Sweet rolling orchetti with Michaela Power Top bottom: Orbanski's Juniper, Buttermilk, and Wildflower Honey

Zero Waste

Perhaps one of the more challenging, and exciting, elements of An Island Collective is the zero waste rule— every bit of every ingredient to be used in the meal. “I did chilli and thyme roasted butternut squash with the peel on since we were going zero waste,” Boothroyd explains, “with wild sumac soy cheese, PEI honey and chillis and I roasted the seeds for the crunch.”

“I did a beef heart with beet tartar with a slew of other ingredients,” Seaborn adds. “We were going for the zero waste idea so as you’re creating more off-cuts, you’re creating more components.”

One of Chindamo’s zero waste tricks is something he calls compost tea. “I collect all of the food scraps—carrot peel, onion skin, meat trimmings—from everyone’s prep and brew it into a really flavourful and layered tea of sorts. What was interesting is that when I told the chefs about this no one wanted to be that person to give me lots of scraps so I had very little to work with which was awesome. That was the whole point of it.”

The Island

The Island Collective brings chefs together from near and far, all with a passion for local, island food. “The

food culture on the island is very strong,” Mullin explains, “and I like how the Island Collective reflects the island so well.”

MacDonald dug into his island roots and prepared a Scallop Crudo, “a nice island dish with a parsnip and maple mousse,” he explains. “I had a little bit of a broth, an Island dashi which was spruce forward, and used a lot of the scraps as well: the peel from the parsnip, the adductor muscles from the scallops themselves and napped the broth over the scallop themselves.” Flynn created a pork belly dish, with pickled beets from his garden and his grandmother’s mustard pickle, for a taste of island tradition. “Using a preserve is a nice way to go zero waste,” he adds.

“Coming from an Islander’s standpoint,” Douglas says, “Events like this can grow our comfort zones and these things are here on PEI and we can appreciate them just as we appreciate a whole lobster plate, or a lobster roll, or fish and chips. So I’m excited to see ingredients that are native to PEI and very plentiful here, start to make it on some of those dishes.”

Camaraderie

“One of the common philosophies between Jesse and I in the creation of the Island Collective is collaboration

22 edible MARITIMES

Right bottom right: Student apprentices plating a dish

and connection,” Chindamo explains. “I think the coolest thing is seeing these chefs come together when they never really have before, some never having even met before,” Douglas adds, “Seeing them all jump into their zones and get it done and push out these amazing looking dishes was very cool for me.”

“It was nice to have that feeling of being in a restaurant again,” Sweet says, “and have that camaraderie—it energized me and made me want to cook again.”

The next event?

“We want to continue this project,” MacDonald says, “to uplift anyone interested in joining, including the students who volunteer to be a part of it.”

“This is wonderful thing that will always be really intentional,” Chindamo says. “Every single part of it well thought out, and one hundred percent collaborative. That’s the goal.”

Al Douglas is a PEI-based photographer who will work for butter, especially if it's cultured.

Port of culinary call

Chef Jakob Lutes’ is the culinary talent behind Port City Royal, a restaurant he opened in his home province after studying in P.E.I. and learning on the job in Ottawa.

WORDS BY JENNIFER CAMPBELL

PHOTOS BY HAQQ BRICE

Jakob Lutes had 18 months left in his engineering degree when he realized that while he enjoyed the studies, being an engineer wasn’t going to be a fulfilling career for him. So, as he puts it, “I quit school and started washing dishes.”

He started washing dishes at McGinnis Landing, a now-closed chain restaurant next to a popular watering hole in Fredericton, N.B., where he’d been studying mechanical engineering. As happens so often, he loved life in the kitchen and soon decided to enroll at the Culinary Institute of Canada at Prince Edward Island’s Holland College.

“I knew that I enjoyed working with my hands,” he says, which makes sense for engineering, too. “What I liked about the engineering was that the math came easy to me, but I prefer to do the building of things, not necessarily the analytic thinking about whether or not a structure is going to work.”

So he started on a path toward building plates of food. The camaraderie he found in the kitchen reminded him of his well-loved days planting trees in Northern Ontario. And it was easy to test the waters in the kitchen by offering to become a dishwasher.

During his internship with the Culinary Institute, he worked in Ste. Catherine’s for Steven Treadwell for five months.

“That shaped my cooking career,” he said.

After he finished his second year at school, he worked on a farm between Charlottetown and Summerside, P.E.I.

“It was owned by Raymond Lowe,” Lutes explains. “He was one of the main spearheads of the organic movement throughout the 2000s. He came from a long line of farmers. His father was a potato farmer and developed the very first patent for a potato in Canada. My job was to essentially attend to the farm and manage people from the woofing program.

After that summer, his partner—now his wife—was enrolling at Carleton University to do a master’s in social work so he followed her to Ottawa.

He sent a note to Ottawa’s chef Marc Lepine at his restaurant, Atelier, because he was interested in

modernist cuisine, but Lepine didn’t need anyone so he went to work at Juniper, another fine dining institution that has since closed. Soon after, Atelier was recognized by en Route magazine as one of the best new restaurants in Canada and it became busy enough to hire Lutes.

Lutes says Lepine and Stephen Treadwell were the two biggest influences on Lutes’ culinary career. He credits Lepine for lots of technical learning and also for teaching him how to run a business.

“At that time, it was 24 seats, so it was a small business,” Lutes says.

From Lepine, he learned how one makes money in that setting, what the structure looks like, how many hours one has to work. He also learned how to like treat people from Lepine, because Treadwell was known as “the Gordon Ramsay of the Niagara region.” Lepine, meanwhile, was “quiet, always thinking, and incredibly creative.”

The Maritimer’s return

Lutes, who grew up in Fredericton, N.B., knew he eventually wanted to return to the East Coast, but Saint John wasn’t on his radar.

He worked for two years as the executive chef at Bartlett Lodge in Algonquin Park and while he was there, he visited his sister, who was living in Saint John at the time.

“I just fell in love with the city,” he says. “And I loved this alley. There's something about the style, all the brick, the height of the buildings, all the potential. I wanted help start something and not necessarily be a part of something that was already established.”

The restaurant is technically in the basement of a building that fronts on the alley’s adjacent Germain Street, but it fronts onto the quaint Grannan Street alley. His restoration of the interior was deliberately rustic, leaving exposed lath and brick, pipes and beams. There are tables and chairs in the rooms to the left and right of the front door, and the one on the left has a large window fronting on to the alley, with a counter and bar stools. The bar and lounge, complete with a welcoming sectional couch, make up the middle. A hole in the floor leads to the basement where the team ages craft beer. There’s a rabbit warren feel to the various rooms and there’s an unselfconscious cool about the place.

SPRING 2023 25

Accolades and adjustments

Lutes established Port City Royal in 2015, the same year it was recognized by en Route as one of the 10 best new restaurants in Canada. Over the years, it has changed and adapted to suit the market in which it finds itself, but nothing forced more change than the pandemic.

“At the beginning of 2019. We were struggling and we had just one too many things break on us,” he says. “I just started getting rid of things, cutting things, including employees. But it started this idea of instead of adding things, what if we just took away? What if we only pursued the things that made us happy and not the things that people expect a restaurant to be?”

That’s been his philosophy ever since, and it’s worked. “I recommend it to anybody,” he says.

When March 2020 hit, he changed the structure again and is now only open Wednesday to Saturday.

“I've got three-day weekends,” he says, adding that those are family days. It’s a trend that chef-owned restaurants

He’s also made some changes to his approach.

“We used to do very New Brunswick-focused hearty meals, while being as creative as possible. But as soon as the pandemic hit, and I was cooking for myself at home, I didn't want to cook home-cooked meals anymore. And I didn't think anybody else wanted them either.”

At that time, his chicken supplier got in touch and said he had a surplus of chicken and no one to take them. Lutes bought them all and then put Korean fried chicken on the menu.

“We knew that we could easily go through his chickens quite quickly,” he says. “Out of each chicken, we could get four portions. We had been doing ramen nights on Wednesdays and that was quite successful so we went all in on ramen. And then we just started doing whatever we wanted. If it came to our minds, we did it.”

He says there are still some creative confinements that he imposes—seasonality being the major one—but mostly, the menu options are wide open.

“A good part of the struggle [of owning a restaurant] is understanding or finding out who the client is,” he says. “It’s understanding a bit of psychology and philosophy and history of business and just trying experiments and seeing if they stick. And I think that's what we enjoy doing. If it doesn't stick, we try something different.”

The Dish

Asked to produce a dish that represents him on a plate, Lutes serves up his Wednesday ramen.

“I love how ramen can be anything,” he says. “It seems as though at the end of the day, so long as you have a noodle and a sauce of some sort, it is a ramen. And I love that because that's how I that's how I approach the world.”

He usually has ramen on the menu these days and the plan is to rotate them monthly. The one he presented when edible Maritimes visited was a shoyu ramen with a pork broth, soy sauce, buckwheat noodles, some sliced beef tataki, pickled shitakes and seasonal vegetables from the revered Saint John City Market.

He uses the services of LifeDirt, a small business in Saint John that bills itself as “the simplest way to get fresh

SPRING 2023 27

local food onto your family’s table.” It offers delivery in greater Saint John and Grand Manan and works with local producers and producers from Nova Scotia. Pete’s Frootique is also a Port City Royal supplier.

When it comes to proteins, he does a lot of his own whole-animal butchery.

“I’d say 95 per cent of it is whole-animal,” he says.

Saint Awesome

Uptown Saint John is enjoying a renaissance, with interesting restaurants slowly filling attractive spaces, breweries popping up here and there and even a whiskey bar called Hopscotch. When en Route magazine awarded Port City Royal the No. 2 new restaurant in Canada, that put Saint John on the culinary map. Just one year earlier, Chef Jesse Vergen of the Saint John Ale House, was a contestant on Top Chef Canada, also bringing attention to the city as a culinary destination.

Lutes had been at Atelier when it received the en Route distinction and Treadwell’s had received it before he arrived, so he knew the importance of the list from a profile point of view. Though in retrospect, he says it didn’t really do anything for them business-wise.

“But it did a lot for me,” he says with a laugh, adding that the external validation was nice and it also put the restaurant on the radar of people outside the city and even the Maritimes.

At the bar

Tom Spencer started working at Port City Royal as soon as he turned 19. He’s now 25, and is general manager and bartender, jobs he balances with a return to university.

“When there was an opportunity to start making drinks and curating the entire drink program—because it's not just doing cocktails, it’s also wine and beer—I took it,” Spencer says, adding that he got his first level of wine certification during the pandemic lockdowns, which gave him something interesting to do “instead of watching Netflix.”

As a bartender, Spencer says he’s not trying to reinvent the wheel. Rather, he prefers to “hone his technique

and try to find innovation” in new and easier ways to do things.

“I love making delicious drinks for people, but I'm also incredibly lazy,” he says with a laugh. “So I try to make everything as simple as possible.”

His first approach to curating what was already a wellrespected cocktail program was to keep what was there in place and then try to add his own spin. At its most basic, he says, there’s a lot of modernism when it comes to cocktails and he too was caught up in that until he realized that the classics have stuck for a reason.

“I think the most creativity just kind of comes from trying to figure out how to do it in your own way with little teeny tiny spins and understanding the nuances,” he says. He says the cocktails on his current menu now sell equally well, which has to be the sign of a good list.

“That’s kind of nice to see, because I've definitely done menus where we have two of 15 things that sell really well and the rest of them are [slow sellers], but now I've got 17 things, they'll pretty much sell the exact same.

Spencer says the intimate bar at Port City Royal allows him to have a close relationship with the people he’s serving, at least in the moment, and gives him a chance to poll them on their thoughts on each cocktail they taste.

The winter list, as this piece was prepared, included classics from Old-Fashioneds to Dry Vodka Martinis, but also some different options, including the quirky Pickleback, which is a shot of Jamieson followed by a shot of pickle brine. It’s an example of a drink that’s been around but is amped up by the restaurant’s superior pickles.

“The Picklebacks are really friggin’ wonderful because the kitch -

Page 24-26: Lutes prepares a Wednesday ramen dish

Page 27: Port City Royal Sign and Preserved Peaches

Right: Tom Spencer mixing a drink

en makes a lot of pickles so I get a lot of them,” he says. “At this point, there might be 20 different vegetables in it.”

Along the same lines are the Paloma, whose tweaks are Amaro Montenegro and Peychaud’s bitters, and the Copper Penny, which features seaweed and sesameinfused scotch.

Port City Royal portcityroyal.com

45 Grannan St, Saint John N.B.

Jennifer Campbell could eat ramen for breakfast, lunch and dinner most days. She doesn't, but she could.

Haqq Brice is a photographer and multidisciplinary artist whose art and creativity are used to express his vision.

Inspired ideas for enduring brands www.steadiicreative.com

Consider the kitchen

Simon Thibault reflects on cooking and learning to trust himself

When you write about food, some people occasionally make presumptions about your personal culinary prowess. The truth is: my knife skills are passable, I have a chronic case of clumsy, and I don’t care if I overcook my pasta. I am, at best, a competent home cook and baker who learned through much trial and error. I didn’t go to culinary school, nor am I of a generation that was taught at someone’s apron strings. My competency in a kitchen isn’t a luxury or a tool of my trade; it was, and still is, a necessity.

At various points in my life, I have lived at or near the poverty line. I had to use my time and money to the best of my abilities, and that meant learning to cook. Not just reading recipes, or shopping well—though those were and are very much part of it—but learning to cook for myself. For my tastes and time.

This is not a “you too can be a plucky home cook” oped about boot-strapping yourself into a farmers market. I’m also not here to give some pollyanna’d presentation on nostalgia and home cooking. Those things do have their own merits, and their own writings, accorded to them. Knowing how to cook, and continuing to learn how to cook, has been a real chore as well as a real salve, and both are worth the effort.

My cooking is dictated by the priorities, privileges, and choices that affect me, and the amount of money and time available to me. On days when I can’t focus on work, or if I may not be able to afford eating out, I know that if I chop an onion, mince some garlic, or put a pot of water on the stove, there will be a tangible result available to me within a set amount of time. A result that will feed me, and satisfy at least some part of me.

WORDS BY SIMON THIBAULT

ILLUSTRATIONS BY ADAM MYATT

Learning to cook can take all kinds of forms. Reading recipes can be inspiring or daunting, depending on who you are. Some people swear by YouTube videos, others by long distance phone calls to family members. Some people have friends show them their tricks of the trade. It doesn’t matter how, when, or what it is, paying attention and repeating certain actions (chopping, mincing, dressing, using your senses) can teach you how and what you want to cook, whatever those dishes may be. If I know how to season a pot of beans or cook grains so that I can eat them for three days without getting tired of them, it’s because I’ve learned over time what works for me, and what doesn’t. That’s what cooking can be.

Cooking is where you can consider your own needs. Not just in terms of nutrition or flavour, but value. Is a certain dish, ingredient, or recipe worth it to you? Some people love making stock, to have it on hand, in the freezer, for whenever. Another person would rather buy their stock in tetra packs or cans. Some people will only buy jam, but I will spend a Saturday pitting sour cherries, chopping rhubarb, and halving plums. Not just because I prefer the flavour, which I do, but because the work of making it is immensely satisfying to me. We all have our own desires, and ways of satisfying them. The act of producing food needs to make sense, to hold value for you. Value that equals the efforts, meets the needs, and does not waste the time used in procuring it.

I am a person who works from home in a small apartment, a kitchenette shoved off to the side of my living/working space. I am best served by lunches that are mostly assembled, rather than cooked. This is why I always have plain cooked rice in the fridge. Brown, jasmine, long grain, short grain, it doesn’t matter, there

SPRING 2023 31

is always rice in this house, and in the fridge. I got into the habit of cooking extra rice when preparing a meal years ago, an extra bit for leftovers, the last bit of stir fry or what have you. Now I will just cook rice for the sake of having it around; I’ll make it on Sunday night while unwinding, or Tuesday morning while caffeinating. Because rice requires only that you pay attention when it has come to a boil, otherwise you’re pretty much golden for options. It is inexpensive and can yield as many variations as your enthusiasm can muster: a quick lunch of fried rice with whatever needs using up in the fridge; microwaved with frozen peas and a fried egg and hot sauce; added to, or made into, soups, stews, congee. That pot of beans I mentioned earlier works really well with nothing more than a little rice, and maybe some shaved hard cheese on top and lots of black pepper.

Although new recipes are no more than a mouse click away, consider the importance of repetition in cooking. Repetition is where you learn about your own tools and talents, foods and flavours that you come to know. You figure out what helps and hinders you. Repeating a recipe more than once gives you more realistic expectations as to your finished dish, where you may want to tweak it, while limiting the possibility of screwing it up. You can tell yourself, “the recipe says to do it like this, but after making it so many times, I know that I prefer it with a little extra of this, and a little less of that. The sauce could stand to cook down a little more too.”

Budgeting the time and funds I have available to me, remembering what works and what doesn’t, I’ve come to know what flavours I prefer, and what works within that budget. Cooking, repeating, has taught me these things. Smoked paprika in small amounts for both heat and depth. A splash of fish sauce or a nub of anchovy paste for a salty umami kick that melts into a dish. Harissa or chili pastes added at the last minute to a bowl of soup to keep their brightness, their heat. Various vinegars instead of lemons for acidity. All inexpensive.

On the little more pricey side of things are dried shiitake mushrooms. They deliver double the punch—when you reconstitute them you end up with both a delicious stock and the mushrooms themselves. That little tub of miso in the fridge goes a long way, like with that mushroom stock, or into a caramel. Parmesan cheese is probably the most expensive item in my fridge, but also the one that can rasped as needed and warranted, metered out with the greatest of satisfaction. A touch on roasted veg, a healthy handful in an omelette or frittata (studded with the leftover veg from last night).

There’s a lot of idyllic writing that pops up in food media when spring comes around. Content is created that details how to “get the best from your asparagus.” When salad greens have returned to farmers markets, someone will inevitably talk about no longer needing to endure root vegetables until next fall. We’re told once again that rhubarb is indeed a vegetable, not a fruit. I’ve said it. I’ve written about it. But this spring, the thing I am most looking forward to is repeating that asparagus frittata, not finding a new way to cook the little spears. I’m happy to eat leafy greens, but I will miss what happens when you slow cook a cabbage in broth. I’m interested in continuing to learn to cook. To learn to trust myself.

Simon Thibault is an author, food writer and editor whose work have appeared in The Globe and Mail, The National Post, CBC and Radio-Canada and many more. Find him at simonthibault.com

Adam Myatt (@trulymadlyadam) is a comedian, artist and writer who lives and works in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

32 edible MARITIMES

General store revival

Camelia Frieberg and her Chicory Blue team have transformed a space at the heart of a community

WORDS BY PEGGY WALT PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

Chicory Blue’s owner is having a multi-tasking kind of day, which is nothing new for Camelia Frieberg, filmmaker turned farmer, turned general store chief cook and bottle washer.

She credits her late father, Joseph Frieberg, a successful businessman, for the entrepreneurial spirit that’s led her to produce her own award-winning films (and a few by Atom Egoyan among others), create a biodiverse farm, develop her Seed to Seed business and help build Nova Scotia’s South Shore Waldorf School, located in a renovated two-room schoolhouse down the road.

But today we’re chatting about her latest venture, reviving a hundred-year-old general store in Blockhouse. She named it Chicory Blue, a nod to the hardy wild plant that sprouts vivid blue flowers in unexpected places, brightening up cloudy days. And while the front porch no longer sports the metal rings where locals once tied up horses, pausing to debate everything from the weather to local politics, comfortable Adirondack chairs now beckon for coffee and a chat. The old cribbage board that was always in use has been found and may make a comeback.

Located just off the highway enroute to Mahone Bay and Lunenburg and 50 minutes from Halifax, Blockhouse was once a thriving community, with the old General Store its central hub. Originally owned by the Langille family, who lived upstairs, it’s lovingly remembered by generations of locals, including Selwyn Langille’s daughter Margot Lutes.

Frieberg glances around. “This multi-purpose room upstairs was once Margot’s bedroom,” she says. “She visits often and loves that we still use the old Enterprise stove her mother cooked on in our baking kitchen. She gave us the most touching thing – four beautiful old China bowls with rose pattern and a little bit of gold. She said, ‘They were my Mum’s, and they were here in the house, and I do think they should come home,’” Frieberg relates. The bowls now serve delicious homemade soups, joining an inventory of vintage dishes lovingly collected by Frieberg from local thrift shops, in keeping with Chicory Blue’s old timey vibe.

Frieberg and her team stock the shop’s shelves with a wide range of local organic products and produce, and hard-to-find spices, locally grown seeds, fresh baked breads and baked goods and delicious meals, including gluten-free, wheat-free and vegan options. But you can also take home 100% recycled toilet paper and

biodegradable soap, or just hang out by the wood stove with an espresso.

The most popular item is their scone. “We sell probably 40-50 a day, and people travel from far and wide to get them. The tomato tart and savoury flatbreads are also really popular,” says Frieberg.

Frieberg got into growing and selling food because of her interest in seeds. “This is really a calling. We like to think we live in a time of greater abundance, but if you look at seed catalogues from the 1940s, there were twelve kinds of broccoli as opposed to the one kind you see at the Superstore or Sobeys. And seeds back then were well adapted to the specific climates of farmers who grew them.” Loving seeds led Frieberg to grow twenty-three kinds of tomatoes and fifteen kinds of melons, which she used to proudly display on her stand at the Lunenburg Farmer’s Market.

“I had white, lime green and yellow zucchinis in all shapes and sizes, and purple and pink and orange and pear-shaped tomatoes. It’s way more interesting,” she

Frieberg takes time to source food from local farmers. Faves include Rumtopf Farm, Sweet Fern Farm (“I supplement my cut flowers with their bouquets”), and Longspell Point Farm in Kingsport who supply “pretty much all our meat, grass fed/grass finished beef, pork and chicken.” She won’t buy meat from someone whose farming practices she doesn’t know, and she searches for certified organic products.

She gets eggs and vegetables and “beautiful spray free fruit” from Kevin at Oakview Farm. “Every year he talks about retiring but he never does, and we won’t let him!” Succession planning on small farms is an issue for Frieberg, who wonders if she’ll find someone to take over her beloved Watershed Farm as Chicory Blue grows.

Being the boss means “fluffing up” vegetables after she’s run around the province sourcing them, doing garden work— “everything started by seed” —training staff or overseeing the drilling of a new well. All hands are on deck, but even after a hard day’s work, Frieberg’s team has been known to knock off and go bowling together in nearby Bridgewater. It’s been a family affair, with daughter Addie working the cash and posting Instagram pics of galettes made with figs that she helped harvest at Watershed Farm.

Having steered the business through lockdowns and changing regulations during Covid, Frieberg has big plans. “We purchased the store the week the pandemic was declared,” she says, “and at first, mostly did online orders.” Since renovating, in just a year they’ve added a full restaurant, outdoor seating, gardens and bike rentals, with plans for a tool lending library.

“The pandemic made it apparent how much we need to be able to provide for ourselves locally, and places like Chicory Blue have shone,” she says. “They’ve been the ones that have borne the brunt of it but also been the places people can turn to.”

Chicory Blue has quickly become a popular gathering place. “We got so lonely over Covid, Frieberg notes. “To come to a place like this, run into people and have human interaction, it sustains us.” The store has opened its gardens and common rooms to wedding and birthday parties, corporate events, craft sales, book-signings and Lunch and Learn sessions on current affairs led by Frieberg’s partner, Angus Smith.

The original general store played a big role in the community too. “It acted as a kind of bank in a way, helping loggers’ and fishermen’s families through the

lean times until they got paid. Frieberg was excited to locate the store’s original cash register, now in use again, noting that it has an “On Tick,” or “On Account” key function, which allowed customers to buy on credit if necessary. She plans to start a membership program to give back to the community through perks and donations.

Asked if her Jewish heritage is reflected in the menu, Frieberg extols the North African and Middle Eastern cuisines: “It’s a true ‘peasant’ cuisine - local and seasonal—so Chicory Blue features falafels, Lebanese lemon soup, dolmades and fabulous harissa dips. Jews have lived in so many places, bringing culinary traditions from all over.” Frieberg and her partner have spent a lot of time in the Middle East and in North Africa and love the foods and flavours of these places While Freiberg's own heritage comes through in all she does, Chicory Blue's doors are wide open to the diversity of community.

The General Store pulls together many of Frieberg’s interests: “Fostering community, growing things, creating beauty, finding ways to bring people together to learn from each other—this is the place where all that happens. There’s this sense that rural communities like Blockhouse can find ways to revive themselves,

and maybe a general store is a foundational piece of that. You can hang here, walk to the yoga studio or the vintage store, take a picnic lunch and ride a bike on the trails.”

Frieberg laughs that growing up in downtown Toronto, no one in her family gardened. “But my grandmother was a child of the shtetl and an itinerant farmworker, she had no choice,” she says.

She reflects again on her father’s example and his many community projects. “He suggested I might want to slow down at this point in my life,” she says with a smile, “and I reminded him that at 89 he was still making business deals. When my dad saw something that could use help, that’s where he stepped in.” As Blockhouse reinvents itself as a destination with its new/old general store at the centre, the (organic) apple hasn’t fallen far from the tree.

Chicory Blue General Store chicoryblue.ca

27 School Rd, Blockhouse

Peggy Walt is a writer, publicist and arts administrator, and holds an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from the University of King's College. When not working on her first book, she loves vintage shopping, gardening and reading. peggywalt.ca

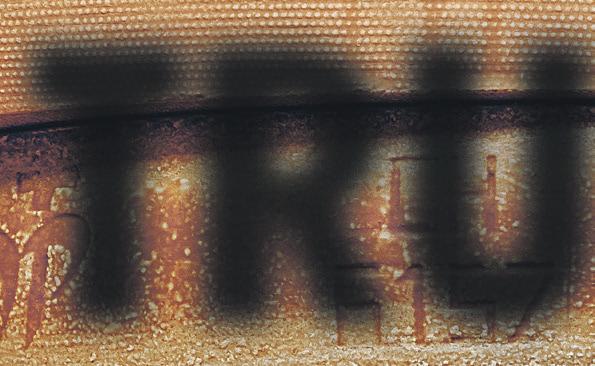

Page 33: Chicory Blue sign that hangs at the bike trail entrance

Page 34: Frieberg stocking shelves

Page 35: Second Floor Library Room at Chicory Blue

Left: Summer flowers in Chicory Blue's backyard garden

Below: Recycled-bicycle wheel bike rack in the backyard

Bottom: Fresh picked Asian Pears

Chicory Blue Fig Galette

These individual fig galettes are so pretty and very seasonal. We grow our figs in an unheated greenhouse and they tend to ripen around late September. This recipe makes about six small galettes, but you could always make one large one and share!

Recipe by Camelia Frieberg

The Dough

1 1/2 cups all purpose organic flour plus a bit more for dusting 11 tablespoon cold unsalted butter cut into 14-16 cubes

1/2 teaspoon fine sea salt

4-5 tablespoons ice cold water (tip: put some ice cubes in the bowl with your ice water and use a tablespoon at a time)

1 large egg yolk (optional for brushing dough before baking)

Place flour and salt in bowl of food processor and pulse once or twice to mix. Add the cubes of butter and pulse again until the butter has broken down into small pea sized clumps. While the machine is on, add one tablespoon of cold water at a time and stop as soon as the dough forms into one big ball. Turn the dough onto a floured surface, roll into a disc about half inch thick, wrap and place in the fridge for an hour (or overnight).

The Filling

8-10 very ripe fresh figs

One block of cream cheese

1/2 cup honey

1 organic orange (zest and juice)

1/2 teaspoon cardamom

Remove the woody stem end of the figs then cut the figs into fat slices from tip to stem. Place the block of cream cheese in a bowl and using a fork mix ¼ cup of the honey and cardamom into the cream cheese until evenly distributed. Place the remainder of the honey into a small saucepan. Add the orange juice and zest to the saucepan and gently heat until the honey is incorporated into the juice.

Preheat oven to 400F and have a cookie sheet and parchment paper ready.

Dust the counter surface and rolling pin with flour. Remove the chilled dough from the fridge and allow it to sit for ten minutes then cut the disc into five or six evenly sized pieces. Roll out dough into 5 or 6 small circles, each approximately 1/8 inch thick and place on parchment paper on cookie tray (don’t worry if the circles aren’t perfect or if the dough cracks at the edges).

Place a large dollop of cream cheese mixture in centre of each circle of dough then place sliced figs over the cheese evenly distributing the figs between the galettes leaving an inch and a half of dough at the edges of each galette. Fold the dough up and over the fig and cheese mixture leaving some of the figs exposed in the very centre. (Optional: Brush the folded-up edges of the dough with egg wash)

Place tray in the oven and bake for approximately twenty minutes then remove tray and drizzle honey orange juice mixture equally over each galette. Return to oven until done, likely another ten minutes. Enjoy!

Shop Local

Canard, Veau de lait, Saucisson, Jambon, Pâté et Galantine

Charcuteries Traditionnelles Françaises

579 Route 945, St-André-Leblanc, NB, 506 532-5579

Green Pig Market

Salisbury

The Spice Box

St Andrews

Find these, and more local favourites, at the Spice Box: 171

Dieppe Farmers Market

Fredericton Farmers Market

Cielo Glamping Haut Shippagan

Co_Pain bakery Moncton

Marché au Corner

Cap-Pelé

A small farm dedicated to growing fresh, local, sustainably grown vegetables and flowers.

St Andrews, NB bantrybayfarm.ca

St Andrews, NB

Prepared take-away foods made daily , Spices, grains and supplements , Fresh seafood and charcuterie

Locally grown produce and owers

SPRING 2023 39

Water Street 3

506-529-8520

, , Baked goods and sweet treats , h

spiceboxcomestibles

Teas, co ee and more

Purveyors of organic local whole foods h

LA FERME LA FERME du DDIAMANT IAMANT

Premium smoked salmon 420 Route 172 Saint George, NB 506-755-1203

Wild Roots

Chef Kylie Brownell mixes new and old in Tusket, N.S.

Imust say I am particularly in awe of this woman, while many restaurants around the world were closing their doors due to the pandemic, Kylie Brownell was opening hers. Branching off at the Tusket exit of Nova Scotia’s Highway 103, the Fishermen’s Memorial Highway, you’ll find Wild Roots waiting for you on the corner.

After working in many restaurants in Halifax and Dartmouth, including The Bicycle Thief, Agricola Street Brasserie and The Canteen, Brownell’s dream of owning her own restaurant, in her neck of the woods, came to fruition in the winter of 2021 and she opened her doors on Mother’s day, 2021.

Walk in the door and you’re greeted with smiles, and instantly feel the warmth. It’s bright, quaint and each table has a unique set of salt & pepper shakers, vintage plates displayed throughout the space. “It’s meant to feel like you’re in my home,” she explains. She’s framed some of her grandmothers’ old recipes and her husband’s great grandmother’s plants make their home here.

Brownell breaks with expectations, offering dishes such as Toasted focaccia bread with baked brie, red pepper jelly, prosciutto, arugula and pickled onions. “I just want to give my community another option,” she says, “I also just wanted to create a place where I would want to go on a date.”

“It was always my dream to have my own restaurant back home, I mean there’s no place like home,” Brownell

A mother of two, wife and restaurateur, Brownell makes time to connect with the community and collaborates with other local businesses. In early December 2022, she partnered with local florist Lisa Fordham of the Flower Bucket, serving up cocktails, Fricot (an Acadian dish), and gingerbread with “the most amazing icing you have ever tasted,” Fordham says.

Wild Roots is not far from the Acadian shores, so it comes as no surprise that her place was packed when she hosted a kitchen party event, with live Acadian music and rich Acadian dishes that celebrated the culture. “It was a hit!” Kylie says with a smile. This past Christmas she hosted a Christmas market out of her space with eight vendors. “There’s room for everyone and I think we should support all the special places our area has to offer,” Brownell says.

Brownell’s restaurant is open from spring to fall, with a few special dinners or events throughout the winter. She switches up the menu with her team frequently, depending on what ingredients are in season and what’s fresh that week but if the focaccia bread is still on the menu, I seriously recommend it.

“People can really tell when you’re being authentic,” Brownell suggests, “so cook what you love, it translates in your food.”

wildrootsrestaurant.ca 4200 Highway 308, Tusket, N.S.

Amber d'Entremont is an Acadian, mother, photographer and multi-disciplinary woman with many strings to her bow.

WORDS AND PHOTOS BY AMBER D'ENTREMONT

Bienvenue à Cielo

Emilie LeBlanc and Pat Gauvin invite you in to share a bite and a story

WORDS BY SARA SNOW PHOTOS BY DAVE SNOW

The Acadian Peninsula, in the northeast corner of New Brunswick, is bordered by la Baie-desChaleurs and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Islands and isthmuses dot its shores as it stretches along the Shippagan peninsula to Lamèque and Miscou Islands, toward the Gaspé Peninsula. Sandy beaches bracket peatlands and salt marshes, while grassy dunes hunker in against the wind and waves and fields of berries work their way inland to farmers’ fields.

Baie Saint Simon, with its eel grass and oyster beds, curls in along the northwest of the Shippagan peninsula. Tucked into a corner of this bay, sit five pearl-like domes, in the trees along le chemin des huîtres—or Oyster Road. This is Cielo Glamping Maritime, a fourseason eco-tourism project in Haut-Shippagan, where owners Emilie LeBlanc and Pat Gauvin are championing a new appreciation, and respect, for this place, their community and local food.

Food in all its forms is central to community here. Shippagan is considered the province’s commercial fishing capital and is home to the Coastal Zones Research Institute and head offices of many fish harvesters’ associations. Wharves, with fishing boats of all sizes and colours, are fixtures in every town along the coast—where people fish for lobster, snow crab, herring, shrimp, oysters, scallops, mussels and more.

“We have berry pickers and foragers too,” Gauvin says. “My aunt and uncle, in their seventies, still pick big five gallon jugs of berries—wild raspberries, blackberries, strawberries. Even cloudberries and cranberries.” He is as passionate about local stories as he is the local food, and has documented many, including a ten-episode series on fishing in the region for Canal D.

Gauvin is a videographer and documentarian and grew up in Lamèque. He met LeBlanc while studying at the University of Moncton. LeBlanc, a dietitian, grew up just south of Moncton, on her family’s third-generation dairy farm in Memramcook. She and her family would take annual summer trips up to the Acadian Peninsula to visit Le Village historique acadien, but, as she explains, “it was when I came with Pat to see family and friends that I fell in love with the place.”

They moved to Shippagan and, while working their day jobs, started dreaming about a new project, possibly involving cheesemaking, to bring people together over music and food and a collective appreciation for this place.

The space

In nearby Paquetville, sommelière and restaurant owner Sonia Jalbert had been partnering with Chef David Forbes, one of Quebec’s most well-known proponents of the movement, to elevate local food in the region. Chef Étienne Buisson, who had worked with Forbes at Charlevoix’s renowned La Ferme in the early 2010s, now worked at Jalbert’s restaurant. “Emilie and I were talking with them,” Gauvin explains, “about how this region is a hidden gem and wondering to promote it.” The conversation took them to Charlevoix to explore its local food initiatives and cheesemaking. They returned, ready to find the perfect location for a fromagerie and they nearly bought one. “That was when we realized it might be hard to make cheese,” Gauvin says with a laugh.

“We really wanted to promote local products,” LeBlanc says. “The idea revolved around the idea of a communal space for the locals and visitors to come and enjoy

a main building they call The Hub, complete with bar and a commercial kitchen. They opened in early 2019. “The pandemic wasn’t good for the bar, of course,” LeBlanc explains, “but the domes were perfect because people were looking for staycations and that's what we promote to encourage local people to shorten your carbon footprint, to not drive so far.”

“When you’re on vacation you don’t always have a lot of time so we wanted to give a glimpse of it here,” LeBlanc says. “Just kind of having everyone mesh with the community—that was our idea.”

A spirit of sharing

The shop space in The Hub is lined with shelves of Cielo’s own pickles, preserves and spices, as well as other products from N.B., including Halcomb honey and Wabanaki Maple syrup, blankets, pottery, candles and skincare products, and refrigerator/freezers full of local charcuterie, fish, seafood and cheese—all made here in New Brunswick. For LeBlanc, this is what it’s all about—sharing the bounty of fine, artisanal products made right here, at home.“At the bar,” Gauvin says, “our wines and beer are all New Brunswick and our cocktails are made with spirits from Fils du Roy in Paquetville.”

In the early days of Cielo, LeBlanc and Gauvin devised the Cielo Board—a charcuterie-inspired way for guests to explore the wide range of local products on offer here. “We want people to discover what is available in the province,” Gauvin explains.

When Jalbert closed her Paquetville restaurant in 2021, Chef Buisson joined the Cielo team. Originally from Joliette, Quebec, Buisson has a passion for creating food that tells the story of a place, he is the perfect fit. He’s expanded offerings to include an line of house-made jellies, pickles and mustards and well as weekly multicourse dinner events. The Cielo Board continues to be a signature item. Guests select from terrines, patés, and cured meats from La Ferme du Diamant, local snow crab, smoked sturgeon and smoked char, smoked by Gauvin’s father. Buisson and his team prepare the board, adding house-made jellies and crackers, edible flowers, greens and other items from their garden.

“The boards bring out the spirit of sharing,” Buisson says. He suggests the perfect board has a little bit of everything, “but I serve oysters first,” he adds. In addition to the Cielo Boards, Buisson and the Cielo team prepare holiday dinners through December and four-course dinners every Thursday throughout the

summer. “I learned at La Ferme,” Buisson says, “to play with the seasons and I’ve kept that, it’s important to us here at Cielo. You see the progression of the summer with our menu.” He sources vegetables and fruit from local producers and from Cielo's growing garden. “Last summer we quadrupled our garden space,” Buisson says. “We are doing our own jellies now, our own pickles and mustards and we made two times the jellies this summer. So it’s really beautiful.” In October 2022, the Globe and Mail named Buisson as one of Canada's next star chefs.

The leap

The shop opens up to a large gathering space with high ceilings and windows that invite the view of the bay right in. The bar sweeps around to the kitchen and, to the left, a large coffee roaster.

Mathieu Noël has just dropped by on his way home from meet-the-teacher night. Noël is the man behind Munro Coffee, named for a deserted island in la Baie St. Simon. “My passion for coffee started in university,” he explains. “In Moncton, there were a few coffee shops where you could get an espresso and I would try all of them. I was always curious about coffee roasting and thought maybe someday I’d have a side business.”

Noël and Gauvin go way back, to high school and skate parks. “I ran into Pat a couple of years ago at a business dinner in town. I hadn’t started roasting and Cielo hadn’t opened. We talked, and a few days later he and Emilie invited me for dinner. They introduced me to this project and invited me to have a roasterie in their new building. This was the kick in the butt I needed.”

A mechanical engineer, Noël has always worked in the fishing industry, working his way to managing one of the largest fish processing plants in Atlantic Canada and, most recently, the fishermans’ association. He started Munro Coffee on the side, roasting once a week and now sells at Cielo as well as distributors along the east coast of the province. In November, he left his position with the fishermans’ association to dedicate more time to Munro Coffee. “We have the capacity to expand quickly,” he says. “It’s just a matter of putting the foot on the gas.” Noël is also embarking on a brand new venture—he and his wife have just purchased two local bookstores, mainstays here for 33 years.

“Now we just close our eyes and take a leap,” Noël says with a smile, “My wife is as crazy as me and she is my partner in the new project.”

The vibe

“Bienvenue à Cielo,” Joliane Robichaud greets a couple at a table by the window. “Quelque chose a boire en entendant?” Robichaud grew up close by in Pokemouche and started working here in June, 2022. She was immediately struck by the Cielo vibe. “Here, it’s like a family,” she says. “I wasn’t used to that kind of vibe in other jobs.”

Music is always on offer in The Hub with special performances by local talent. Gauvin, himself, often picks up his guitar and plays for guests. And tomorrow, Gauvin and LeBlanc will host a group of high school students who are coming in to talk about entrepreneurialism.

Gauvin and LeBlanc, along with Buisson and Noël and the entire Cielo team, are champions of community, bringing people together in celebration of what is right here. It’s clear from their stories, that all good things happen around a table, sharing food and conversation with old friends and new ones.

Cielo Glamping Maritime, Haut-Shippagan, N.B. cieloglamping.com

Page 42: Gauvin and LeBlanc

Page 43: A walk to the beach

Page 44: Buisson and Gauvin and a view of the domes in winter

Page 45: Charcuterie, Cielo pickles, and Noël pulling a shot

Pages 46-47: LeBlanc stocking products, Charcutier and Buisson stirring the pot

Spring Zing

Bite into spring with this simple recipe and play around with it, substituting one crunchy vegetable (or fruit) for another.

2 cups peeled and chopped or julienned spring kohlrabi

2 cups peeled and chopped or julienned radishes

If you don't have kohlrabi or radishes on hand, try carrots, beets, apple, turnip

1 garlic clove, peeled and chopped finely

1 tablespoon peeled and finely chopped ginger