14 minute read

BACK OF THE HOUSE

BACK OF THE HOUSE WOMEN IN THE KITCHEN

Women chefs are well represented in top posts around the Monterey Bay, and we talk to three of them about how they’ve achieved success in what has traditionally been a man’s world.

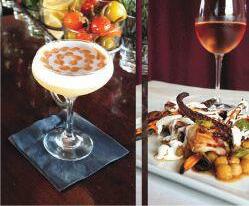

Advertisement

BY PATRICE VECCHIONE PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHELLE MAGDALENA

A woman’s world: from left, Gabriella Café’s Gema Cruz, Art of Food’s Wendy Brodie and Sierra Mar’s Elizabeth Murray all have or currently run restaurant kitchens in the Monterey Bay area.

For most of us, our first meals came from women—our mothers, and later, if we’re women ourselves, we tend to become the home cook. Like countless middle-class American women of the 1960s and ’70s, my mother was a devotee of Julia Child. ough she worked full time at a demanding job outside our home, as soon as she got back from work, just after opening a beer, happy in the kitchen, my mother began preparing elaborate dinners, like shrimp jambalaya or crab crêpes, and what was newly popular in the United States, quiche Lorraine.

How is it that women who for eons have been home cooks don’t dominate professional kitchens? ere, men stand at the top of the field—in terms of prestige, position and, especially, in numbers—as they do in so many others. Deborah A. Harris, co-author with Patti Giuffre, of Taking the Heat: Women Chefs and Gender Inequality in the Professional Kitchen (Rutgers University Press, 2015), says that because home cooking is unpaid work, it is “given less value and viewed as an expression of caring about others.” ere’s the rub, isn’t it?

Only 21% of American chefs and head cooks are women, according to the most recent figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Of the Michelin-starred chefs worldwide, just 1% are women.

In 2017, how can this imbalance still exist? “It’s a combination of the history of the occupation in which women were excluded from cooking schools and professional kitchens for many years, along with development of a masculine work culture that makes it difficult for women to fit in and become accepted,” Harris says. en there are the long hours and, she adds, “e lack of health and maternity benefits, that makes it difficult for women to balance work and family.” A woman’s place may be in the kitchen, that is, as long as she isn’t earning her living there.

In truth, the myriad reasons why individual women decide to become professional chefs and why others choose different careers are as diverse, vibrant and stereotype defying as the half of the human race that women represent.

And here in the Monterey Bay area, we’re quite well represented by female chefs—many of them not just head chefs, but the owners of the restaurants where they cook. In Santa Cruz, there are Kendra Baker of e Penny Ice Creamery, Jessica Yarr at Assembly, Katherine Stern at La Posta and Ayoma Wilen at Pearl of the Ocean, just to name a few. In Pebble Beach, there is Angela Tamura of Pèppoli; in Carmel, Michelle Estigoy at Cultura Comida + Bebida; and in Carmel Valley, Sarah LaCasse at Earthbound Farm. In Monterey there is Stone Creek Kitchen’s Kristina Scrivani and in Moss Landing, Kim Solano, creator of e Haute Enchilada. In Aptos, Cori Goudge-Ayer heads Persephone and Ella King, Watsonville’s beloved Ella’s at the Airport. And not only is this list not the half of the women chefs leading local brickand-mortar restaurant kitchens—it doesn’t begin to count the legions of women chefs who have established thriving local catering businesses.

What follows are conversations conducted earlier this year with three local women chefs about the very different routes they have taken to their professional kitchens and the very different chef’s lives that they have forged.

THE PIONEER

Wendy Brodie is a bright-eyed and lively woman. She’s someone who may return an email with a phone call if she feels conversation would serve best, a rare and welcome gesture these days! Mention her name to anyone in the business and they’ll have only good things to say.

A graduate of the first class of the California Culinary Academy of San Francisco, a celebrated chef and caterer, she was co-owner of the popular Lincoln Court restaurant in Carmel and over her long career has held executive chef positions at such prestigious resorts as e Preserve at Rancho San Carlos and Stonepine Inn. In 2011, she was inducted into the Disciples of d’Auguste Escoffier. She has cooked with such celebrity chefs as Julia Child and Martha Stewart.

I was delighted to be invited to her gorgeous Carmel Highlands home called Zenwood to chat. With its open floor plan and sweeping ocean views, it’s a place where she frequently hosts dinners for those who want to throw a party but aren’t so skilled in the kitchen or whose homes can’t accommodate a crowd. She also teaches and hosts a local, weekly television cooking show, e Art of Food. On a rainy afternoon, with cups of hot tea in hand, we sit down for a leisurely, rambling conversation about her work. Like a racehorse, she says, “I can go around the clock for two or three days non-stop. I get passionate about an event and its overall creation. en I love the collapse afterward and the time spent in reflection.”

About teaching, Brodie says, “I love sharing what I’ve learned along the way so people can make it their own. When they learn cooking methods, they’re free from being recipe driven and can be at the farmers’ market or the supermarket and get inspired by what they see, knowing how to mix this and that. You know, you can give 10 chefs a chocolate chip cookie recipe and you’re going to get 10 different versions.”

For years, Brodie cooked outside her home. “In a restaurant, the line is a machine.” Because so many people who’d go to her restaurant, Lincoln Court, knew her and would want to say hello, she could be seen nearly in flight running between the kitchen and the dining room, but she loved it.

About her time as head chef at Stonepine and e Preserve, she says, “ere were usually set-course meals, and buffets were set up, so I got to also be at the front of the house; it was kind of like a home situation. I could do the centerpieces and flower arrangement. ere was a whole creative element to it.”

Commenting on the role gender plays in the restaurant business, she says, “Many of us have the vantage point of the woman being the main person in the home, the center of home. For me, it’s very comfortable to be able to give and cook and share, though my mother really didn’t know how to cook. Her mother had been a great cook who never passed it on. My mother used to say, “Wendy, you came from a dysfunctional kitchen!’”

As far as having a family of her own, Brodie felt her career limited her choices.

“I realized that if a woman working in a restaurant had a family, she couldn’t run home to a sick kid,” Brodie says. “A guy can have a family and kids and that’s fine. But a woman doesn’t really have that liberty unless there is someone at home taking care of things.” Consequently, Brodie chose to forgo having children. “I never felt it was an option for me,” she says.

As for what she appreciates about the culinary world these days, Brodie says, “ere’s joy in seeing garden people find an heirloom variety that hasn’t been grown in years, or mixing the apricot and plum together to create something new. I love the colored carrots, too—so many things for the culinary artist to be excited about.” And she appreciates the concept of global cuisine, something that the culinary academy didn’t offer at the time.

THE NURTURER

Gabriella Cafe is a Santa Cruz favorite and, as I recently discovered when I came to interview head chef Gema Cruz in the cozy dining room before dinner service started, if you don’t have a reservation for Saturday evening, you may be out of luck. A busy night will have the place serving 100 dinners.

Cruz credits her grandmother for her career choice, and Cruz’s memories of watching her grandmother prepare meals from what the family grew at their rural Oaxaca home continue to inspire her.

Cruz paid close attention to her mother and grandmother as they prepared the family’s meals in their simple home. She saw how hard these women worked, starting early in the day, cooking and cleaning up until late at night.

From her grandmother, she learned, “When you cook happy, your food is delicious because your whole emotion is coming through your body, through your hands and your feet.”

Cruz gets excited telling me about the foods that she grew up eating. “We ate what was on our farm, and rabbit. It’s easy to catch a rabbit in the mountains where it’s harder for poor people to get other protein like beef. You can make a lot of things with the food we grew like pumpkin and corn. In Mexico, you use everything you have. You eat the pumpkin and the seeds, and with corn you use the leaf, too.”

Using sustainable techniques has been a part of Mexican culture forever. What the people don’t eat, the animals do. “Nothing,” says Cruz, “is thrown away.”

Foods from her childhood that she cooks with today include yucca, which she prepares like sweet potatoes, and the herb pápalo. Very strong in flavor, it’s almost a mix between cilantro and arugula. “It comes from Puebla, Mexico,” Cruz says, “One of the local farmers got the seeds because I asked, and he grows it for me!” And what does one do with pápalo? “Mix it with cream and lemon for a sauce to serve on fish,” she says. “It’s totally delicious!”

When she was 17, Cruz’s family left Mexico for California. Shortly after her arrival here, she and her mother began preparing lunches-togo for fieldworkers. Word about her food spread quickly and she began getting requests for holiday dinners and school functions.

Cruz began as a dishwasher at Gabriella Café. Yet, once owner Paul Cocking took her up on her offer to cook, she became the chef. And not just any chef, “the best chef I’ve ever had,” he says. Today, Cruz expertly fills an esteemed post previously held by such local legends as Jim Denevan, Sean Baker and Brad Briske.

What Cruz brings to Gabriella Café is a family and cultural tradition of feeding and caring for people that she blends with a creative approach to food.

When guests visit the restaurant and request something special or have a food allergy, Cruz says, “yes,” and adjusts the ingredients to accommodate them. “Say I’m making rabbit with guajillo sauce and someone doesn’t want guajillo. en I’ll do it Italian style, with prosciutto, sage and cheese. A lot of chefs say, ‘No, I only serve what I have on the menu,’ but I tell the waitresses, ‘You don’t have to come in and ask me. Just tell the person yes.’ And then I make them happy!” She loves doing that; she loves it when diners peek into the kitchen, as they often do, to personally thank her for their meals.

Cruz sees the difference between female and male chefs as a matter of motivation. Because women come from a long history of cooking for their families, she says the work has passion intrinsic to it—a dedication to pleasing people through food. “When I cook,” she says, “it’s like singing and dancing, that kind of happiness.”

Cruz’s children sometimes ask her why she works so much. Her reply is consistent, “Mija, I’m working because I like it and because I want a better life for you. I don’t have time for tired, and once I’m cooking, I’m not tired anymore; I’m transformed. My kitchen is a sacred place.”

THE RISING STAR

Sierra Mar executive chef Elizabeth Murray left her home state of North Carolina and worked for a while in Arizona before landing in Southern California where she cooked at San Diego’s acclaimed George’s at the Cove. From there, she says, “I kind of flew the coop, sold everything I owned, put my knives on my back and went to New York and then Europe.”

With a winter rainstorm quickly approaching, Murray and I sit down together in the bar of Sierra Mar, which is perched atop a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean at Post Ranch Inn.

“I’ve never worked for a female chef,” Murray tells me. “It’s interesting for me, interviewing for chef de cuisine and sous chefs, in general, when somebody comes in who’s had a female mentor or worked for a female chef. I ask, ‘What’s that like?’” ey’re lucky people who will get those jobs, I’d bet, to have the chance to work for this woman chef. Murray is calm and confident, and she knows how to listen.

“I’ve worked with a lot of very aggressive and intense, brilliant, top-of-the-league chefs. From them, I’ve tried to take the good. For me, it’s all pretty new to be in that leadership role. I try to be as upright and respectful, creative, inspiring and team building as I can. If you’re building a team, you have to make your players shine,” she says.

“e person I’ve learned the most from was when I was at George’s at the Cove, working for Trey Foshee, a surfer. He was the most mellow chef of them all. Always respectful, he created positive work environments.”

Murray enjoys immersing herself in different cultures; she’s traveled extensively for her work—spending several months at Noma in Copenhagen before heading to Pappacarbone on the Amalfi Coast of Italy, where she learned by watching and doing. “It was all in Italian, so say I’d be working at the fish station, I’d just memorize names of the species of fish as they appeared on the tickets.” From Italy she took to Paris, working with a great butcher outside the city. During her time abroad, Murray found gender not to be an issue. What mattered was whether you stepped up and worked hard.

Having worked with Michelin-starred chefs, she reflects on the weight that comes with that honor: “If you’re a Michelin chef, that means you have a very specific idea in your mind about what you’re making—how it’s understood, how it tastes. at’s what a lot of the aggressive thing is about. You’re trying to get everybody to perfection. e people working for you need to have that kind of absolute dedication.”

Would Murray’s management style change were she to become a Michelin-star chef, I ask her. “I’ve been in a couple of kitchens where they’ve received a star, been there before and after. I’ve seen that change,” she replies. “I think the people I might respect most in this industry are the people who give back the star. ere was a woman in Germany, recently, who gave back the star and stated, ‘At the end of the day, that’s not what I do.’ I know that Michelin gives recognition of the highest regard to chefs but it can make you do what you do for the wrong reason.”

Murray is thrilled to be running the kitchen at Post Ranch. She lives on the property so her life is concentrated right there in that gorgeous place, where she makes supreme food.

“We’re an internationally known hotel; we’re focused in our way and create a space that is unique. To me, that’s the mantra. If something else follows from that, great.” Here’s a chef not looking for what follows; she’s happily dedicated to what’s right in front of her.

BACK IN MY OWN KITCHEN

My perspective is one of a home cook, not a professional, but sitting down with Wendy, Gema and Elizabeth felt easy, the connection natural. A kitchen has always been one of the places where I’m most at home. Being able to make a meal out of almost nothing is second or, maybe, first nature. Feeding others is about as primal a satisfaction as I can imagine. Certainly, being a woman is part and parcel of this and, though my mother has been gone for 30 years, she often greets me in the kitchen, saying, “A little more garlic, sweetie, don’t you think?”

Monterey artist and writer Patrice Vecchione’s latest book is Step into Nature: Nurturing Imagination and Spirit in Everyday Life. For more, go to www.patricevecchione.com.