5 minute read

GROW BIZ

Cultivating the Future An Ojai Biodynamic Farm Comes of Age

BY LESLIE BAEHR | PHOTOS BY STEPHANIE PLOMARITY

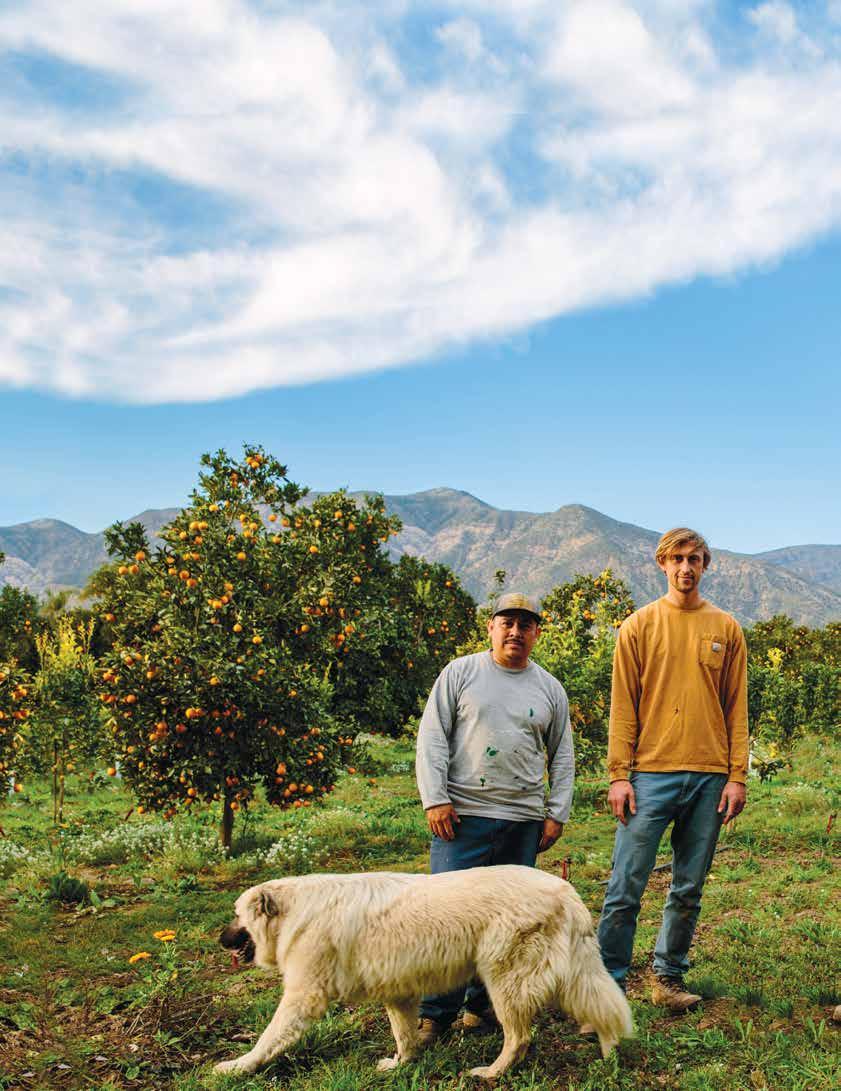

When Reynolds Fleming and his family bought a 20-acre When Reynolds arrived at their new 120-year-old property in orchard in Ojai’s East End, few knew a potential “citrus 2015 (along with his sister Severine, a farmer-activist who helped apocalypse“ (so called by the Los Angeles Times) was quifound the operation), much of the soil was poor, the ecosystems etly spreading throughout Southern California. lacked biodiversity, and the trees were dependent on synthetic ni

Though he hadn’t worked in citrus before, the undertaking seemed trogen fertilizers. To achieve his goals, Reynolds would need to grow an ideal combination of his aptitudes for science, design, innovation more than just food. He needed to grow a prototype, something that and environmentalism. Fleming didn’t just want to do farming. He could demonstrate how “the imperatives of an agricultural system” wanted to understand it, to quantify it, to make it better and eventucould be realigned with those of “the natural systems that envelope ally to teach it. it.” He needed an organic biodynamic farm.

“[I was] really interested in Buckminster Fuller, in Frank Lloyd Put crudely, biodynamic farming ups the ante on organic, transWright—the kind of people who were doing what people had always forming the land from a mere orchard to more of an ecosystem done, but with an ecological sensitivity,” he says. (or self-sustaining “organism,” as biodynamic certifying agency

“I think that what we’re seeing is productivity that’s going to be achieved by not disturbing the natural power of organic methods, and science is what’s going to really strengthen the argument.” —Reynolds Fleming

Demeter puts it). For example, adding animals helps ensure “the waste of one part of the farm becomes the energy for another,” says Demeter.

Totem Ranch, as it would come to be called, had work to do. They planted permaculture zones and refuges for beneficial wildlife and insects. They brought in farm animals to control pests, to weed and fertilize the landscape. They revamped their irrigation system to be more efficient and took measures to restore and recycle nutrients and organic matter back into the system.

All the while, on the other side of the country, the citrus industry was in crisis. The Asian Citrus Psyllid (ACP) pest had invaded Florida, bringing with it the citrus-killing Huanglongbing (HLB) disease.

By 2016 the epidemic had cost Florida an estimated $7.8 billion, nearly 8,000 jobs and a devastating chunk of its citrus, according to an informational hearing. And by 2017, it was clear that HLB was moving into California as well.

Reynolds was not even a year into Totem when he first heard of the epidemic. “In some ways, ironically, I thought that there might be something like that,” he says—be it zoning, climate, or water supply issues.

In theory, the biodynamic principles should render a farm’s immune system better able to resist disease in general and, with every new initiative, the Totem organism hopefully grows stronger.

“The farm is very much a design,” he says. “It’s very much a

Bennett Ranch c. 1900 then (left) and now (right) as Totem Ranch. Reynolds Fleming and Theresa Martinsons (pictured) are restoring the property’s historic house. place where you can be creating new ideas and coming up with new solutions.”

With the help of two employees and his girlfriend, Theresa Martinsons, ideas and solutions abound. They’ve used unmanned aerial vehicles to apply nutrients and ACP treatments, begun breeding beneficial soil microorganisms, use a 1,500-gallon compost tea brewer to further build the soil and work toward precision agriculture through software irrigation analysis and leaf and soil testing.

Meanwhile, the California Department of Food & Agriculture reported last year that ACP quarantines were in effect in 28 counties, Ventura included. Neighboring Los Angeles County already exhibits HLB disease, sparking concern that Ventura is not far behind. As a result of the quarantines, Totem (which sells only through packinghouses, though you may have unwittingly picked up their citrus at local markets like Whole Foods) is required to either wash the fruit, which is not currently feasible for the ranch, or spray organic pesticides, Reynolds says. They spot-treat trees of concern in order to spray the least amount possible.

Perhaps the whole endeavor has only made Totem’s mission more imperative. Just a few years after their original Ojai purchase—now fully organic and Demeter biodynamic certified—they bought the 42-acre orchard next door and began transitioning that as well. The efforts are bearing fruit. “You just see a huge diversity,” says Martinsons.

Today, in addition to Pixie tangerines, lemons and three types of oranges, the ranch has welcomed 50 species of diversified fruit trees such as pomegranate, fig and mulberry, which dot the property and provide a break in the citrus. The soil has come back to life with beneficial microorganisms and can now help sequester carbon, absorb water and provide a more aerated growing environment. Nutrient-restoring cover crops thrive between orchard rows and pollinator species, like bees, are again buzzing among trees.

The second part of the ranch will be certified organic biodynamic in May, but in some ways, Totem is just getting warmed up. They’ve begun restoring the property’s 1890s farmhouse for establishment as a historical landmark. And, like any good prototypers, they continue seeking ways to “quantify the magic” of organic biodynamic practices, potentially serving as a test site for a local university.

“I think that what we’re seeing is productivity that’s going to be achieved by not disturbing the natural power of organic methods,” says Reynolds. “And science is what’s going to really strengthen the argument.”

Leslie Baehr is a science writer and content strategist who works with media outlets, research institutions, not-for-profits, and companies. An alumna of MIT’s Graduate Program in Science Writing, she enjoys exploring the interplay between science and ideas. You can reach her at lesliegbaehr@gmail.com.