29 minute read

Tensions and Shared Key Stewardship Learning

A Word About Process

In a successful social innovation lab, participants move from rigid mental models to an increasing ability to hold tensions as they carve out action-oriented pathways forward. This meant participants had to be aware of their own biases, beliefs, wishes and interests as they supported their teammates’ differing journeys; they also had to balance that with occasionally conflicting feedback from the community. In developing prototype interventions to reduce racism, participants also had to be willing to go on a personal and transformational journey, engaging deeply in counter-cultural ways of being, reflecting, problem-solving and working together as good Treaty people. As well, participants were expected to try new approaches (we are a lab experimenting with ways to reduce racism). Not everything worked and we had to boldly go against the grain in many cases. We embraced this challenge. From the continual feedback we Stewards received on the process and outcomes, we want to share our learning, tensions, and some guiding principles we uncovered that might help in future action-oriented lab explorations and anti-racism initiatives.

It Really Is About Relationships

A problem we noticed early after we launched Shift Lab four years ago was that if someone offered another person a harsh critique — but the two had no pre-existing relationship — the critique would not be taken and reflected upon, and behaviour would not change as a result.

We saw that without a relationship, a person’s wellintentioned critique, or call out, would be dismissed and people would further fall into a polarized, adversarial view.

Relationships are central

Jodi and Derek evaluating a tool used in the lab

This was one reason we landed on the overarching question of Shift Lab 2.0, and the specific core question of how to compel “people of privilege” to overcome white fragility to become better allies and dismantlers of systemic racism. At times in Shift Lab 1.0 and 2.0, we honestly explored whether it’s possible to shame individuals and systems into having healthy relationships and to be less racist. We learned that this approach, over the long-term, would result in relationships rooted in fear, power struggles, and pain.

That said, no one wakes up to their own complicity in systemic racism without some shame, learning, fear, and pain. But people need to come to this themselves for there to be lasting and deep behaviour change. The catalyst for the transformation can come from a jarring external experience, but unfortunately it seems to only create meaningful reflection and behaviour change if it comes from someone a person is in a trusting relationship with.

This became clear through Darryl Davis’s work, which he shared with the Shift Lab in our international Speaker’s Series. Darryl shared the way he has influenced KKK members to renounce the organization through long-term relationship building. As a Black man, he obviously doesn’t agree with them but does the extremely tough work of trying to listen and see the human in the person. His approach is very effective, but also very intensive and risky. We recognized this approach is not the answer for everyone nor is it easy to spread and scale. Still, it illustrates how important relationship building is for change.

On the other hand, we felt we can’t be asking racialized persons to do the tough work of deep relationship building and explaining racism — only to experience the pain it causes, over and over again. This reality is a paradox in effectively tackling racism, and one that requires social innovation. We don’t think we have solved it, but we learned a few things over the last four years in stewarding Shift Lab 1.0 and 2.0. In particular, we felt that as Canadians we could navigate this paradox in a new and novel way through learning from Indigenous perspectives on relationships as that has been a long-ignored view. It is difficult to adequately capture the breadth and depth owed to them, but in Indigenous epistemologies, relationships are key to mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional well-being. Not just relationships between humans, but relationships between interconnected systems and beings. In the Western world, social innovation, design and systemsthinking approaches to community problem solving have emerged, however the attention on relationships is often missed. Design and systems approaches can lean towards breaking down problems into their component parts and determine the core needs in problems to be solved. In good systems-thinking practice, relationships between parts in a system and how power and forces move between them is explored; however it is more often from an analytical place and can tend to devalue emotional, spiritual and land-based perspectives.

As Stewards, we strove to not privilege one worldview more than another. We didn’t want to fall into the trap of “tolerating” worldviews, but actually learn and “go deep” together as treaty relatives in good relations with one another. We felt that if we were going to steward community solutions to racism, then we needed to work on relationships, our own anti-racism journeys, acknowledge mistakes, admit biases and be bold enough not to settle for surface-level pleasantries, but really dig into this wickedly complex issue. Going deep is required for a tough challenge like reducing racism and to do that, high levels of trust and honesty are required for transformational change. As stewards of a process that we guided with diverse community members, we had to constantly check our own journeys at the same time as do our best to safely support the journeys of individuals, four prototype teams, the lab group as a whole, and our work in the community. All of this required doing our best to steward good relationships. This did not mean everyone had to agree and be nice to each other, but instead meant strengthening relationships by digging deep and sharing honestly.

Learning and Suggestions For Centring Good Relationships in Social Innovation Labs

• “Nothing about us, without us”: Do alongside

Indigenous, Black or racialized people, not to, or for.

• If you are white, own it and accept. These conversations will not centre your voice or your feelings. It may be uncomfortable at times, but it’s worth it.

• Act on showing you value people in relationships in a social innovation lab. Compensate them equitably and provide for transportation, childcare and other necessities to support their participation.

• Take as much time as required to get relationships right.

• Bring in people’s unique gifts and expertise.

• Act on and model being true treaty relatives. True reconciliation requires it.

• Humans are not the centre of everything!

Relationships to land, water, spirit, animals are key; be open to it. Learn from Indigenous perspectives in this area. • Try to see the humanity in all people while at the same time setting clear boundaries and not allowing disrespect or dehumanizing behaviour.

Create the lab team’s rules of engagement together.

• Don’t convene Stewards or Core Teams that all think alike. The magic happens in fostering a safe experimental zone of healthy relationships where true diverse perspectives can make the whole better

• Be careful of falling into the trap of black-andwhite thinking patterns. Be willing to be wrong.

• Check your privilege.

• Don’t ask racialized persons to have to explain to white people why racism is so painful, kills people and still is a systemic problem. Direct people to educational resources first.

• Look out for each other.

The “Sleepy Middle” Archetype Is Controversial

Working to effectively shift the “Sleepy Middle” was identified in the research as a powerful leverage point for addressing systemic racism. This was often misinterpreted as coddling the privileged rather than seeing it’s about figuring out how to more effectively wake up the Sleepy Middle who are keeping systemic injustice in place covertly or unconsciously.

Martin Luther King Jr. identified the challenge with white moderates, or what we called the “Sleepy Middle”:

First, I must confess that over the last few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Council-er or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action’; who paternalistically feels he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a ‘more convenient season.

A few years earlier, in 1958, activist and researcher Gerry Gambill (also known as Rarihokwats, meaning “He writes” in the Mohawk language) made similar observations at a conference in Tobique, Manitoba, in a speech titled ‘On the Art of Stealing Human Rights’:

“Convince the Indian that he should be patient, that these things take time. Tell him that we are making progress, and that progress takes time.”

More recently, CNN broadcaster Van Jones commented on a New York City event, where Amy Cooper, a white woman called the police on Chris Cooper, a Black man, in the midst of a bird watching incident in May 2020:

“It’s not the racist white person who’s in the Ku Klux Klan that we have to worry about,’ the former Obama adviser said. ‘It’s the white, liberal Hillary Clinton supporter walking her dog in Central Park.”

There are many well-intentioned, unconscious and “asleep” moderate people who are unaware of the systemic racism they are complicit in upholding.

We wanted to explore what effectively “awakens” the Sleepy Middle — not to give more power and privilege to them, but so they become better allies, make space and contribute to a more equitable world that everyone deserves. We wanted to research what mechanisms could activate the Sleepy Middle. We looked at whether shaming, aggression, and threats could truly awaken the Sleepy Middle or whether it might be creating further polarization and possibly more overt acts of racism.

Even though we Stewards came from activist backgrounds and often wanted to burn unconscious systems of oppression down to the ground, we also wanted to look closely at what works to shift the Sleepy Middle. We recognized it’s likely a mix. To be clear we recognize space needs to be made for strong direct action. There is a place for it in addressing overt systemic racism and injustice. Working on the Sleepy Middle is not glorious; it’s a little boring and not as fiery as activist approaches we were used to. This never meant we were less committed to addressing racism and by choosing to work on shifting the Sleepy Middle we knew we were going to be criticized by our colleagues for not being radical enough. However, if we could contribute to waking up the Sleepy Middle, then this could be a contribution to systems change alongside our direct action colleagues.

One of the tensions to navigate when trying to shift the Sleepy Middle is knowing when and how to provoke effective discomfort and cognitive dissonance, which can elicit deeper reflection on biases and complicity in unconscious systemic racism. We also recognized it’s inappropriate to keep

asking and tasking racialized persons to explain racism.

People who have experienced racism are hurt, in pain, angry and rightfully tired of explaining it. To not burden racialized persons, the team working on countering white fragility decided to not have racialized people on their team help with testing prototypes with folks from the Sleepy Middle. Instead, white allies on the team did the heavy lifting with the Sleepy Middle when explaining and testing the white fragility subscription box prototype. We learned from the core team’s leadership that this was a good example of a diverse team stepping up in the right contexts and not expecting everyone to contribute in the exact same ways.

We feel there is still lots to explore with shifting the Sleepy Middle effectively and there are delicate tensions to navigate. More white people from the Sleepy Middle also need to stand up and not look away from injustice. Racialized voices need to be centred and listened to, but the Sleepy Middle can’t keep asking what they should do to become better allies, and less racist. There are many tensions and paradoxes to navigate, and it will be messy — and people need change now. This will take some tough reflections, tough conversations and it won’t all be pleasant, but it can’t be avoided any longer.

An Example Of The Sleepy Middle Waking Up

Following the global Black Lives Matters protests, sparked by the police killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, the cultural mainstream (i.e., white folks) seemed to understand the prevalence of racism today. At least, they said so, in an unprecedented groundswell of support for anti-racist issues. At the time of this report, it is too early to judge the effectiveness of this massive cultural pivot. While the issue is rife with bland corporate pronouncements of solidarity with little to no action promised, there are good examples of the Sleepy Middle waking up and using their platforms to be anti-racist, as illustrated by an Instagram post by Chicago Blackhawks Captain Jonathan Toews, who was born and raised in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

I can’t pretend for a second that I know what it feels like to walk in a black man’s shoes. However, seeing the video of George Floyd’s death and the violent reaction across the country moved me to tears. It has pushed me to think, how much pain are black people and other minorities really feeling? What have Native American people dealt with in both Canada and US? What is it really like to grow up in their world? Where am I ignorant about the privileges that I may have that others don’t?

Compassion to me is at least trying to FEEL and UNDERSTAND what someone else is going through. For just a moment maybe I can try to see the world through their eyes. COVID has been rough but it has given us the opportunity to be much less preoccupied with our busy lives. We can no longer distract ourselves from the truth of what is going on.

My message isn’t for black people and what they should do going forward. My message is to white people to open our eyes and our hearts. That’s the only choice we have, otherwise this will continue.

Let’s choose to fight hate and fear with love and awareness. Ask not what can you do for me, but what can I do for you? Be the one to make the first move. In the end, love conquers all.

Learning and suggestions for future labs

• Don’t expect racialized persons to keep explaining to the

Sleepy Middle why racism is still a problem.

• Don’t expect a single person to represent or be responsible for the entire views of a community.

• Ask who are you trying to shift and what might be effective.

• Challenge everything you think you know. Question whether tactics/interventions/prototypes are working to shift the way they are intended. Do tests to keep assumptions in check.

• Diversity, unconscious bias and anti-racism training that is one-off, rather than ongoing, doesn’t seem to lead to lasting systems change. However there is some promise in integrating drip campaigns and behaviour nudging to wake the Sleepy Middle up and not going back to old patterns.

• Working on shifting the Sleepy Middle is innovative, controversial and counter-cultural in activist circles.

It will likely be interpreted as not radical enough or another covert way of upholding systemic racism and white supremacy. Don’t shut down radical perspectives that push back on this, make space as there are many different approaches required.

• Remember the importance of relationship-building for sustained change.

No One Is Ever Outside The System

We often grappled with whether the lab exploration was for the 25 Core Team members to undergo a transformational experience, or whether it was for the members to go into the community, learn, and design solutions within the Edmonton context to end racism.

This tension is felt in most labs but can depend on the approach; whether the lab is more inward- or outwardoriented. We felt we had to mix both because you can’t work on racism outside without working on yourself and those you collaborate with. Put plainly, racism isn’t something anyone can solve with an “objective” perspective. Often, in design and systems challenges, stewards of a problem-solving process approach the issue thinking they are the experts in an “objective process.” This is not the case, especially given how wicked the challenge of racism is.

For this reason, the lab journey has to have individual reflections, balanced with ways to explore externally for larger community/systems change. This tension and balance is not easy to navigate. It requires thoughtful planning for both. We strove to steward both individual reflection and external explorations in systems through hosting longer lab sprints, building in time for deeper reflection together and supporting the four prototype teams between sprints. Jodi, in particular, guided the Indigenous ways of reflecting together and listening, so that participants could strengthen relationships and confront bias to learn and move forward positively. Reflecting on racism and lived experiences is triggering, especially for racialized persons, and there needs to be deeper trust and the support of team members in place to not burden people and give space and support when needed.

We were not perfect at navigating this tension. The strength, empathy, and maturity of the Core Team members to support each other was the real gem of Shift Lab 2.0. We recognized that as Stewards we didn’t always need to step in, but strove to create a safe space for deeper exploration. We had to steward hard conversations and address elephants in the room as it would have been inappropriate to leave Core Team members on their own. All of us are never outside systems of power, relationships, biases, emotions, our own stories, and how our stories rub up against other people’s stories.

Top and bottom: Core Teams working in the lab

Learning and Suggestions For Future Labs

• Build in time for individual reflection, provocations, team discussion and deeper ways of listening.

You’ll likely always feel there isn’t enough time and will need to balance what is reasonable to ask of people’s time (compensate them well too) and the process to lead discovery.

• Centring Indigenous knowledge systems around listening, reflecting and relationship building is very helpful for seeing connections between people and systems. Beware of doing this in a tokenistic way. Do it for real and this takes time and relationship building and following proper protocols.

• Recognize and build in time to reflect on bias.

• Have a witness who isn’t a steward of a lab but part of a core team to witness and share at the end of a lab sprint, or workshop on what they observed with how the lab was living up to the espoused values, biases that got in the way and improvements for next time.

• Build in developmental evaluation to keep the stewardship team responding to emergent feedback and adapting to needs of individuals, teams and community.

• Bring in the strengths of core team members to share their knowledge. Don’t fall into the trap thinking that the Stewards need to know it all and have all the answers.

• A lab around a deeply complex issue shouldn’t be about ensuring everyone is nice to each other all the time. If the conversations become heated and emotional, run with it rather than try to squelch it.

This is a difficult, but necessary step if the lab is to uncover previously unearthed insights.

What We Learned Together From Our Triple Helix process

We intentionally centred Indigenous knowledge in the social innovation lab process, and it was woven together with design- and systems-thinking approaches. This meant one worldview wasn’t more important than another. It all required decolonizing practices. Our stewardship team has diverse identities, and brought unique expertise and experiences to ensure our Triple Helix approach wasn’t just an intellectual exercise. We were all learning, creating, and adapting as we journeyed together.

We wanted our lab to be an example of how diverse groups could show up and be good treaty relatives together. We wanted to not just tolerate each other from a distance, but to bring out the best in each other and support each other. To start this with our Triple Helix, we recognized we had to have strong relationships in order to disagree, question ideas, and still have deep respect and friendship. A weave of thread is very strong. Relationships were the weave in the helix.

Indigenous ways of relationship building were key. So, too, were some practical pieces like making the length of a sprint a whole weekend rather than just a day or half day. Working to be bold enough to end racism, we grew strong together. We needed our different perspectives to make the whole greater than the sum of its parts. We sometimes wondered that, if we all want to be better true treaty relatives, perhaps it might take getting together in collectives and working together on something important and in relationship. In other words, the act of working together in a healthy relationship is part of the goal of being better treaty people. If we had more of that in Edmonton, there might be stronger relationships, equity, and a move towards authentic reconciliation.

What Is Ethical To Combine In The Triple Helix?

In creative problem-solving practices like design thinking, a common practice is to remix and combine disparate ideas. Often, innovations emerge from combining seemingly unrelated things in a novel way. To enhance innovation, the Western practice is often to increase collisions and combinations between diverse, often unrelated ideas. For example, the inventor of Velcro saw how plant burrs attached to fur when walking through the forest and remixed this for clothing. Eureka moments often come from these jarring collisions. But in some contexts, there’s a problem with this. Cultural appropriation, especially by Western cultures, raises ethical concerns. The Stewards made a conscious effort to encourage the team to engage ethically with Indigenous knowledge and not to decontextualize Indigenous ideology and apply it to any situation as they saw fit. There needed to be relationships built, protocols followed, and communication with Elders and advisors in order for there to be authenticity.

We worked to not add to the historical legacy of researchers extracting knowledge and practices from Indigenous peoples. The Indigenous knowledge keepers, Elders, and participants bridged the worldviews, pointing out where there may be similarities and also points where things could not be combined and needed to be left on their own. We also were keenly aware that there is no such thing as “pan-Indigenous.” There is a tremendous amount of diversity in teachings, worldviews, and traditions just within Indigeous Treaty 6 peoples, let alone the rest of the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island (North America). The key in ethically weaving the Triple Helix was having Indigenous leadership as an equal part of the decision making and stewardship of the lab.

Ashley sharing on keeping power and privilege in check when designing social innovation prototypes

Tension Between Processes

A deeply ingrained Western worldview is how arguments are built, debated, and judged as true or not. There is an urge for simplicity, reason, a thesis, and key evidence that supports the thesis. This attempts to control, or give the illusion of control, laying things out logically. In design thinking, there are generally five stages you move through, with clear activities and steps at each stage. In systems thinking, there are steps to look at systems, and tools to uncover structures and question biases in a system.

But in Indigenous worldviews and problem-solving processes, there aren’t five steps, a thesis, bullet points. Indigenous worldviews are instead rooted in complex systems, landbased practices, customary laws, languages, and ceremony. Humans aren’t the centre of these relational systems. Indeed, there is a spiritual dimension that weaves throughout and can’t always be explained step by step. A clear tension is the risk of decontextualizing Indigenous practice: these practices cannot be removed from the larger epistemological framework in which they exits. When this happens, misappropriation occurs.

We wondered: Is the end state we want one where everyone is respected to do their own thing, alone, or is it where traditions mix and complement each other so that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts? It’s likely we want a mix of both — some mixing of ideas and traditions and some ideas best left within their own contexts and traditions. With our Triple Helix approach and striving to * model being good treaty relatives we tried to honor this complexity.

* kawâpahtihweyahk esi miyowâhkôhtoyahk ekwa ekakwekisteyihtamahk ôma anohc iyikohk ehâyimak.

It was liberating and helpful when we gave up trying to fit everything Indigenous into a logical view or flow. There needed to be trust to dive in, and to have trust there needed to be relationships. It really is all about relationships. That’s the braid.

Learning and Suggestions for Future Labs

• When including Indigenous knowledge, it is imperative to include an Indigenous leader to guide this work.

• Take turns leading the work of bringing together multiple worldviews.

• kakiskinohtahikoyahk iyiniw enîkânîstahk tân’si ki’kway kesi-isiyinihkâtamihk kesi-mâmawiâpahcihtahk pâpîtos isihtwâwina

• Build and strengthen relationships through ceremony and working together on an important initiative as true treaty relatives.

• Don’t privilege one worldview over another.

• Learn about decolonizing practices.

• Don’t make Indigenous people try to package their traditions in Western frameworks.

• Don’t hope for a set of bullet point.

• To hold our traditions/cultures in high regards as they were given to us by the Creator to use here on

Turtle Island/mother earth.

• Kwayask ka-ispihteyihtamihk anima mâmawwiyohtâmîmaw kâki-iyinamâkweyahk nistam ôta kâ-ahikoyahk ministik/kikâwinaw otaskiy.

Improve Prototype Implementation

One learning from Shift Lab 1.0 that we used in Shift Lab 2.0 was the need to improve the implementation of prototypes. Specifically, we saw how prototypes from 1.0 struggled to launch because none had a “home” or resources for sustained support. In fact, as of July 2020, a prototype from Shift Lab 1.0 has just found a home and funding with a community partner — three years after it was created (and a ton of volunteer work of Shift Lab 1.0 Core Team and Stewardship members).

Social innovation labs throughout the world struggle with implementation. Some lab practitioners feel labs should create a portfolio of ideas co-designed with affected stakeholders. Implementation is very different, in this thinking, from a lab process and should be kept separate. Other lab practitioners, like ourselves, feel there should be a mix of both. If we can’t figure out pathways to implementation, we feel we have let the community we worked alongside down.

From the outset of Shift Lab 2.0, we worked toward launching good ideas from a lab environment into the world. One way was striving in our Shift Lab 2.0 research to garner demandside interest from host organizations and systems. The concept of demand-side and supply-side labs was introduced to us by Mark Cabaj, who was the core developmental evaluator.

Supply- Vs. Demand-side labs

One way to categorize labs is whether they work from the “demand” side of things or the “supply” side. Do these potential prototypes already have a home (demand) or does the lab have to hunt for their home after they have been produced (supply)? The Winnipeg Boldness Project is an example of a demand-side lab: there is a specific context, location, and community that the prototypes are intended to support. The Shift Lab, on the other hand, stayed a supply-side lab. We are developing prototypes that address a particular issue that can be applied in multiple contexts, locations, and communities.

The challenge of supply-side labs

There is a strong need for external partners to get prototypes off the ground. This requires hunting for a place to support the work of the lab and the prototypes it produces. This entails finding not just an organization with the skills, tools, and resources to implement the prototype, but also one with the right cultural fit, desire, and intentions. This element can be time-consuming.

Secondly, once things are rolling and the prototypes are designed there can be a struggle when it comes to handing off the work from the designer(s) to the implementer. In addition to governance and ownership, issues of ability, trust, communication, and the right intention must be answered before a handoff can be made.

Finally, a very specific skillset is required to implement and incubate prototypes. It takes dedicated project managers, grant writers, stellar communicators, and the ability to keep iterating and adapting to ensure the pilot responds to needs.

Shift Lab 2.0 remained a supply-side lab but we got better at incubating and launching ideas

We tried for eight months to find demand for Shift Lab in specific organizations and systems. We tried within HR departments and large institutions, but each wanted to see what would be created first. In addition, none wanted to allow a community team to come into their organization to work on systemic racism and prototype interventions. After lots of attempts, we got comfortable with the limitations of a supply-side lab and honed our strategy to increase our impact with implementation. As of July 2020, our strategy seems to be working much better, as ideas are getting off the ground quicker.

Below are the strategies we engaged to get better at implementation with a supply-side lab

• Seek a great funder that gets social innovation: We partnered with one of the most innovative funders in the country, the Edmonton Community Foundation. We’re not just saying that. ECF is doing very innovative work around granting and funding social innovation. (See

Ashley’s report on funding social innovation labs from our previous Shift Lab 1.0 report in 2017)

• Scope challenge areas well before a lab to have greater impact later: Another reason there was better success with implementation was because we learned from Shift Lab 1.0 about the challenge of scope. We did the research (eight months pre lab) and convened four stellar teams around four challenge areas that Edmonton and Treaty 6 area are really wanting change around. This meant there was naturally more desire for interventions and outcomes at the end.

• Embedded granting Innovation: We had an embedded funder with Ashley from ECF on our stewardship team.

This was not in any way an oversight role, but a broker and bridging role between the lab’s needs and the funder. This allowed for better responsiveness from our funder as learning in the lab emerged and changed overtime. Ashley also has deep anti-racism theory and practice knowledge and deep lab knowledge developed over four years of co-stewarding the Shift Lab. This was a very unique role for a funder and as far as we know unprecedented in social Innovation labs in Canada. It is very delicate to do this right and the deep relationship building, trust and dedication of resources from ECF was key.

• Make small films of what happened in the lab: This one may seem out of step with implementation, but having a couple of short films that explains what happens in a lab and what testing of prototypes looked like in action was helpful for pitching and credibility of the core team’s amazing work.

• Special prototype grant stream just for Shift Lab:

This creative relationship with our funder allowed for the creation of a special grant stream to continue funding

Shift Lab prototypes after the lab was completed. This grant stream has few strings attached, is nimble and has feedback loops to ensure good stewardship of funds and deliverables. These grants are in $10,000 packages for each prototype, and teams can keep applying in $10,000 increments after the completion of deliverables. This has allowed for continued work on prototypes after the lab workshops concluded.

• Prototype showcase event: After the lab workshops closed, we hosted a prototype showcase and invited potential allies, supporters, collaborators to see the community prototypes and have opportunities to get involved. This led to some collaborations with for instance

DevFacto exploring development of the HR reflection pool app prototype.

• Prototype manager role: Post lab we hired contract prototype managers (3) with the specific skill set to continue refining and developing the prototypes. Over six months after the lab, it was their responsibility to oversee the prototype’s continual development, develop budgets for next steps, work plans, and write the $10,000 grants to ECF. They also had to sustain the right relationships and links between the previous core team working on the prototypes and continued iteration. This role was a major game changer for ensuring prototypes kept moving because a dedicated person was assigned the role. See the appendix for the job description and deliverables of a prototype manager.

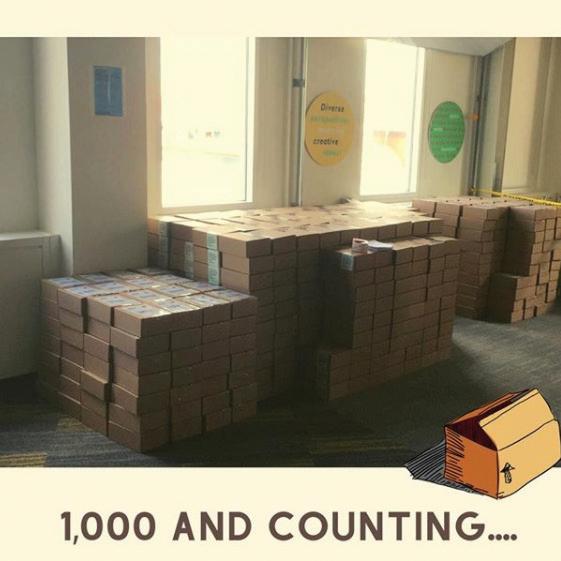

As prototypes evolve, timing can be everything. What’s happening in the system around the lab creates leverage points for prototypes to be desirable, feasible, and viable. For example, the team working on addressing how to help the Sleepy Middle face white fragility launched their anti-racism subscription box (You Need This Box) at the time many white people looked themselves in the mirror after the police killing of George Floyd. As a result, in 48 hours, more than 1,000 requests for the box came in.

The team had planned for 30 boxes.

In less than a week, ECF once again stepped up and funded the creation of the first 2,300 boxes. The demand for this prototype was partially due to circumstances in the ecosystem, but also because we had a prototype manager assigned.