28 minute read

Shift Lab 2.0: Evaluation

Overview

Shift Lab 2.0 adopted a Developmental Evaluation (DE) approach. DE allows social innovators to obtain real-time feedback on the design and implementation of the work so that they can respond and adjust to new learnings and insights.

Note

Though many of our informal evaluation techniques were based in our Triple Helix methodology, we were not able to fully realize braiding formal Developmental Evaluation with Indigenous evaluative methods. We are currently developing and testing a “two-eyed seeing” evaluation tool that attempts this braid. Stay tuned to our website for updates!

Evaluators

• Paige Reeves, Lead Evaluator, Skills Society Action Lab

• Mark Cabaj, Advisor,

Here to There Consulting Inc.

Interested in learning more about Developmental Evaluation? See http://www.betterevaluation.org/en/plan/ approach/developmental_evaluation

Core team members taking an opportunity to better know one another

The evaluation was organized to answer the following broad questions:

• What is working well and not so well in the lab? How can we improve the lab? • What are we learning about racism, the Sleepy Middle, and anti-racism approaches? • What is the likely feasibility, effectiveness and support for the prototypes that emerge out of the lab? • What are implications for future efforts to address racism in Edmonton? • What are implications for other social innovators tackling complex social challenges?

The evaluation was carried out continuously throughout the lab and included:

• Regular meetings between Evaluators and the

Stewardship Team • Surveys distributed to Core Team members after each sprint and at the conclusion of the lab • Core Team summaries of feedback from prototype testing • Focus group and one on one interviews with Stewardship

Team members The evaluation feedback was useful in two ways. First, it supported the Stewardship Team in being responsive to emergent learning throughout the lab. Second, it surfaced learning and reflection thought to be useful for both the social innovation community and others working to tackle racism. Shift Lab 2.0 resulted in four promising prototypes, as well as learning and change amongst Core Team members. In addition to these results, several key insights surrounding lab methodology, racism, and changing the behaviour of the Sleepy Middle also emerged. Broadly speaking, Shift Lab 2.0 and the learning that occurred within it, makes significant contributions for the broader community, others working to tackle racism, and the social innovation community.

This part of the report is organized into two main sections: (1) results and (2) key insights.

Results

This lab resulted in four promising prototypes as well as learning and change among Core Team members.

The Prototypes

A key contribution of Shift Lab 2.0 are the four anti-racism prototypes generated. Each holds great promise to contribute to addressing racism in Edmonton and beyond.

Prototyping involves a continuous iteration process, often in the form of sketches, diagrams, paper models, sticky notes, and other rudimentary materials. The goal is to have each prototype ready for pilot testing with a community partner organization(s). It is a fast, risk-free, inexpensive, messy, and creative process to test promising ideas. At each stage of the prototype’s development, feedback is sought (both internally, amongst the prototype teams and Shift Lab Stewards as well as externally with stakeholders, funders, and partners), considered and evaluated to strengthen elements of the prototype that may be lacking.

The Idea

Keep testing?

Test

The Prototyping Process

Courtesy of Mark Cabaj

Scale

Pilot

Spin-off Keep testing?

Test Scale

Pilot

Spin-off

Prototype 1.1

Evolve

Prototype 1.2

Evolve Keep testing?

Test

Prototype 1.3

Scale

Pilot

Spin-off

Discard Discard Discard

Discard: the prototype is unlikely to be effective, feasible and/ or supported, so should no longer be pursued.

Test: we don’t feel we have received enough feedback from people on our prototype; we need more feedback from other people.

Evolve: the basic idea is good, but we need to further develop and adapt prototype to reflect the changes recommended from others. Then we should test the new version Pilot: the feedback on the prototype is good enough to warrant a more formal pilot project and evaluation.

Adopt or scale: The feedback on the prototype is so good that we don’t need to test it further – it’s ready for implementation.

This includes everything from the initial value proposition of the prototype (Who will use it and how does it benefit them?) to the design and execution of it (Does the prototype do what we want it to do? Is it feasible, reliable, valid?) to the evaluation, communications and distribution plan of the prototype. Similar to prototyping in the technology space, rapid iterations allow for proof of concept as well as other insights to crystallize from an emergent process. This allows for insightful a-ha! moments to happen. However, not every realization gets added on: the prototyping process allows teams to refine and discard elements deemed redundant, counterproductive or out-of-scope. Importantly, this is not considered a failure or limitation. Rather, it is a way of establishing a clearer, more concise vision of what the prototype is supposed to do.

On pages 44-61 of this report find a description of each prototype, the challenge they respond to, how they were tested and what was learned from testing, as well as plans for next steps.

Core Team Member Learning and Change

Core Team members were motivated to participate by a desire to combat racism and effect social change as well as an interest in learning about social innovation, design thinking and centering Indigenous knowledge in the lab. Many Core Team members spoke of the rich learning and, at times, personal transformation that occurred for them through participation in the lab process.

Core Team members experienced an increase in commitment to, and confidence in, addressing racism in their communities.

The majority of Core Team survey respondents felt:

• Their insight and empathy into the general experience of racism stayed the same or increased over the course of the lab

• Their understanding of their own experience and/or interaction with racism stayed the same or increased over the course of the lab

• Their understanding of what they could do to address racism increased over the course of the lab

• Their commitment to addressing racism increased over the course of the lab

• An increase in confidence in their ability to help address racism over the course of the lab

• Spurred to take actions to address racism beyond the specific prototype they were a part of (see Q28 in survey)

This learning is an important outcome of the lab to recognize as it is thought to have ripple effects for tackling racism. Core Team members, even after the end of the lab, will carry this knowledge forward, share it with others and incorporate it into their own personal, work, and community lives. “Learning about and addressing racism is an ongoing, every day commitment. Still so much learning to do and so much opportunity to take action.”

— Core Team Member

“New connections and perspectives that I did not have previously. My understanding of cultural celebrations and Indigenous epistemology through the explanations of design lab processes and story. That was a highlight of my learning and makes me want more.”

— Core Team Member

“The modality and values that the Shift Lab operates under — humanness, kindness, care - will stay with me.”

— Core Team Member

Being mindful of lab principles is key

KEY INSIGHTS

In addition to the results previously outlined, a number of key insights related to lab methodology, racism, and changing the behaviour of the Sleepy Middle emerged out of this lab. See these insights expanded upon in the sections that follow.

Reflections on Lab Methodology

The following insights related to lab methodology emerged as part of Stewardship and Core Team member reflections:

A balanced approach: both planned and emergent

Reconciling the tensions of racism

Supporting ‘going deeper’

Highlights of participant feedback on the process

The need for focussing on more than innovation

Tensions in evaluating prototypes that tackle complex social issues

Reflections on supply-side vs demand-side innovation

Building capacity within the social innovation ecosystem

Stewards strove to strike a balance between ‘planned’ and ‘emergent’ in their overall approach — both serving important purposes and contributing to the overall success of the lab. This balance was baked into the Triple Helix approach that wove together Indigenous, design, and systems worldviews. The Indigenous worldview tended towards the ‘emergent’ side of things with a focus on relationships, being present in the moment, and a reliance on guiding principles rather than rules. The design and systems worldviews tended to lean towards the ‘planned’ side of things with a focus on structure, processes, and tools. Together they provided a ‘roughly right’ mix of structure and emergence.

“Throw out the plan, be in the moment, be present, be in relationship with people … this draws on Indigenous ways of knowing.” — Steward

“I hold onto the ideas of openness and curiosity - to ask myself and others, “when was the last time you changed your mind about something?” — Core Team Member Few contemporary issues are as charged as racism. Early on in the process, each member of the Core Team was made aware that this was the raison d’etre of the lab. Within the confines of the lab, the realities of experiencing racism and the toll it takes surfaced periodically in various ways: • Through the sharing of deeply personal and emotional experiences, particularly from Indigenous and Muslim members of the team • From group discussions and lectures to the Core Team • Collecting and relaying observations from the field during prototype team work

Some of these tensions arose not through direct conflict or provocation but inadvertently: a telling point about racism is the covert as well as overt nature of its expressions. While virtually everyone had fairly deep academic, professional — and, for BIPOC individuals, firsthand experience — this tension still felt jarring every time it arose. At times, Stewards and Core Team members would suggest de-escalating, and relationship building practices to allow the group to process these feelings.

Indigenous advisors

One of the biggest insights from Shift Lab 1.0 was the importance of creating a space and process for lab participants to ‘dig deeper’ into the challenge - exploring their own experiences and the stories of others in order to expand their understandings. In Shift Lab 1.0, participants did not always feel safe - nor felt there was time and space — to engage in deeper reflexive and generative dialogues about racism.

In Shift Lab 2.0, the Stewardship team prioritized creating safe spaces and processes for deeper exploration. Outlined below are some of the strategies, tools, and practices the Stewardship team employed in Shift Lab 2.0 in an attempt to facilitate deeper exploration in Core Teams.

• Otto Scharmer’s “Four Types of Conversation” framework: A formal tool used to help teach Core Team members about different levels of conversation.

• Indigenous epistemologies: Indigenous (primarily but not exclusively Cree) epistemologies, forming one third of the Triple Helix approach, were woven throughout the entirety of the lab approach. Grounded in relationship and reciprocity, these epistemologies contributed to team members’ ability to ‘go deeper’ and build relationships with one another.

“Indigenous epistemologies helped us go deeper and be present … if we didn’t incorporate them I don’t think we would have gotten as deep.” — Steward “I don’t know exactly what will come of them but the relationships that were started have shaped me in ways that I can see and I believe in ways I cannot even begin to understand yet.” - Core Team Member

• Opportunities to share feedback: Formal (e.g. surveys) and informal (e.g. conversations) opportunities for team members to share feedback on their experiences in the process were provided. Feedback was then incorporated into practices moving forward. This contributed to teams feeling heard and understood.

• Constructive conflict: Space was created for teams to feel as though they could openly disagree with one another and strategies were provided on how to navigate this in constructive ways. Conflict allowed for learning and growth in the teams.

“It was powerful learning to see the incorporation of people from many different backgrounds, realities, and experiences coming together, without glossing over difficult conversations or power imbalances, but trying to work with and against them.” — Core Team Member

• Built in shared experiences: Curated experiences such as ceremony, berry picking on the land, and a medicine wheel exercise, provided opportunities for teams to bond over shared experience, be vulnerable with one another, and ultimately build stronger relationships and establish trust. • Time Spent Together: Allowing time to unfold was a big piece! Creating space for going deeper takes time and cannot be rushed. Sprints were intentionally designed to be two and a half days in length and the entire lab process over 18 months long to support this.

The above tools, strategies, and practices enabled the formation of deeper relationships amongst team members. This depth of relationship was critical in enabling teams to go deeper in their grappling with the issue of racism and ultimately strengthened the prototypes.

“If people feel safe and free to share a counter cultural idea this creates a fertile ground for those kinds of ideas to emerge. Fear is a creativity killer … a lot of what you’re trying to do when drawing out creativity is … create a safe zone so people can question — what about this wild idea?” — Steward

“The feeling of community and of family within this group.” — Core Team Member, Sprint 3

Highlights of Participant Feedback on Shift Lab Process

“I appreciated the process that combined learning, action, and interaction among the larger group and smaller teams. The way that the sprints were organized and conducted fostered personal growth for participants, new outlooks, and prepared teams to do the work in between sprints.” — Core Team member

Lab Structure/Governance

Strengths

Core Teams • Diverse mix of engaged, committed, courageous, and curious people Limitations

• Having multiple teams working on differently scoped challenge areas meant there were differences in group processes and at times inconsistencies in process; some found this confusing and challenging at times

Stewardship • Strong facilitation skills, diverse perspectives, solid team dynamics, distributed leadership model

• “In each of our weaknesses, the others had strength” — Steward • Distributed leadership and highly shared decision-making processes can mean it takes longer to get things done

Lab Activities

Upfront Research Strengths

• Provided strong knowledge foundation for teams

Stewardship • Led to rich learning on part of Stewardship and Core Teams that permeated later aspects of the lab process • Provided opportunity to engage broader community in conversations about racism • Raised the profile of the lab

Field Research • Enabled real and meaningful connection with community members with wealth of knowledge and/or experience to contribute Limitations

• Required considerable time and expertise to pull together in meaningful and accessible ways

• Required additional funds, time, and energy to coordinate

• New experience for many led to feelings of uncertainty — some felt more support could have been offered

Prototype Testing • Exciting opportunity to get real time feedback on prototypes • New experience for many led to feelings of uncertainty — some felt more support could have been offered

Community Showcase • Great way to showcase the work of Core Teams and the prototypes that emerged from the lab in a public way • Public nature and fact that not all core team members could attend led to some core team members feeling a lack of closure with the process

Strengths

Logistics/Implementation

Limitations

Project Length • Provided time for relationships to form and a depth of exploration of the issue

Sprint Length • Longer length contributed to deeper relationships being formed, greater introspection • Project ended up taking longer than expected

• Some wished sprints could be even longer to allow for greater depth of relationship/trust and more time to dive deeper into the issue • Sprints were a considerable time commitment and took away from family life for some as they occurred on the weekend

Funding • Huge asset to have a funder that was comfortable with the emergent properties of the lab

Sprint Spacing • Allowed for work in between sessions that could happen on core team terms - greater flexibility was a plus • Provided space for emotional decompression and further reflection

Sprint Location • Action Lab was an excellent space for out-of-box thinking • Pressure to produce tangible, measurable outcomes on timeline and within a budget

• Tricky to find a meeting space that accommodates everyone’s needs

Strengths

Logistics/Implementation

Limitations

Sprint Format/ Content • Design successfully enabled depth of relationship amongst participants. Some participants reported this increased their sense of accountability to one another and created space for people to tackle/explore their own racism and assumptions • Small and large group work enabled learning from others • Skilled lab facilitators enhanced the experience • Mix of stories, interaction, and formal learning • Indigenous ceremony was grounding, centring • Opportunity to get outdoors in some sprints was welcomed

Evaluation • Evaluation points built in throughout the process enabled Stewards to be responsive to group needs • Depth and intensity of content was mentally and emotionally exhausting at times • Not all exercises/attempts worked well!

An attempt at role playing for example was a bust but enabled rich conversation amongst groups in a debrief

• A more embedded model could have yielded deeper insights and strengthened Stewards capacity to incorporate real time changes

The Shift Lab aims to help people develop innovative responses to racism in Edmonton. The case for the focus on innovation is compelling: there are already plenty of resources out there that touch on the topic of racism, with general recommendations on how to do so, but there is comparatively little in Edmonton to help people come up with concrete and novel ways to make it happen. The Shift Lab is a part of filling this gap alongside anti-racism colleagues working in the space.

Yet, while developing, testing, and (if appropriate), scaling innovations is a necessary part of addressing racism, it is not enough on its own. A similar insight was discussed in the Shift Lab 1.0 report where it was noted that a social innovation process should complement, rather than replace, other approaches to tackling racism and poverty.

Although Shift Lab 2.0 was primarily focussed on supporting niche innovations, it also contributed to shifting awareness and culture. One of the ways it did this was through the implementation of an international speaker series targeted to the general public.

International speaker series

The speaker series had an impact on shifting awareness and culture in the following ways:

• Participants more willing to act: Participants in the speaker series reported feeling more willing to act to help reduce racism in some way (Shelly’s talk):

“I feel a bit more ready to take a first step, to learn, and to listen.” — Attendee at Shelly’s talk

“It added more tools to the toolkit and pushed back the fear of a contentious topic.” — Attendee at Shelly’s talk • Spurred to take tangible action: Participants reported they might take the following tangible actions to reduce racism after attending the session: • Reading further literature and seek out other public speaking engagements on racism • Initiating and continuing conversations on race • Share knowledge and practice skills with others including taking learnings back to their workplaces • Approach conversations differently

• Deeper understanding of racism: Participants in the speaker series felt the talks helped them better understand racism and prompted the emergence of a series of significant insights and questions for participants. Insights about: • The systemic nature of racism • Strategies and approaches for talking about and tackling racism including (‘both/and” and “yes/and”) • The different types of racism

The speaker series also positively affected the design and development of the lab process. Many members of the Stewardship and Core Teams attended the speaker series and key learnings were woven throughout the lab process. The different speakers provided tangible frameworks, strategies, and reference points for team members to draw on throughout the lab and in the development of their prototypes.

Overall it was felt that the speaker series was well worth the extra time, energy, and money it took to pull it off as it enriched both broader community and Shift Lab 2.0 team member learning.

“[Racism] … its roots are deep. It has become so normalized. It’s going to take incredible breadth and depth of work to manifest through systemic change; incredible investment to make big change within our cities, provinces, countries.” — Steward

Tensions in Evaluating Prototypes That Address Complex Social Issues

The use and development of prototypes is foundational to a design approach. This is meant to expand the set of solutions generated by encouraging multiple, low cost, low risk experiments. In a design approach, most prototypes are not meant to make it to adoption and even fewer to scaling.

Important learning about developing and testing prototypes that address complex social issues occurred within this lab. These insights are important for improving prototype evaluation in future iterations of the lab as well as for contributing to the development of the broader social innovation ecosystem.

Evaluating prototypes

Prototype evaluation involves inviting would be users, beneficiaries, funders and partners to provide feedback on the strengths and limitations of the idea. In the early phases of prototyping, social innovators present their prototypes to would-be users and partners and get feedback through openended questions. For example:

• Tell me more about…[e.g. How someone would access this service]? • Why did you choose to…[e.g. Include that organization]? • Have you thought about/have you considered... [e.g.

Charging a fee]? As innovators expand on their ideas and refine the details, the prototypes become more fully developed. As a consequence, questions become more focussed:

• Is the prototyped idea coherent? (Do people understand it?) • Is it plausible? (Is it likely to work?) • Is the prototype idea feasible? (Do we have the capacity to do it?) • Is it viable? (Would it be supported by key stakeholders?)

If and when the group feels confident enough to test its idea in a formal pilot project, a more fulsome evaluation design can be developed, involving a more sophisticated approach to measuring outcomes. This will enable the group to decide whether or not the idea is worthy of widespread adoption in the community.

Tricky Tensions That Emerged Related To Testing in 2.0

On the One Hand Tension

On the Other Hand Design Considerations

Testing prototypes is a core component of a design approach

It’s a natural human thing to feel attached to ideas you develop - commitment bias Test freely and vigorously vs test modestly and mindfully

Pursue many prototypes vs Let only a few prototypes survive Testing prototypes on sensitive issues such as racism has the potential to elicit uncomfortable and potentially harmful feelings/responses

Design approaches are built on the ‘letting go’ of ideas with only a few surviving What safeguards need to be in place to mitigate harm during prototype testing?

How do you support teams in overcoming commitment bias and being comfortable with letting go of ideas?

Reflections on Supply-Side vs Demand-Side Innovation

An honest effort to employ demand-side innovation

In the beginning of Shift Lab 2.0, the Stewardship Team sought out organizations who were both interested in addressing racism in their organization or work, and also in partnering with the lab to develop innovations. This was done in an effort to organize the lab process and prototypes to: 1) sharpen the lab’s focus on concrete design challenges and 2) develop and test ideas that had a higher probability of being ‘adopted’ by an institution after the early experimental work in the lab

Despite significant effort, the team was unsuccessful in finalizing such a partnership and instead pivoted to incorporate a supply-side approach.

Some of the perceived barriers to organizations participating as demand-side partners

• Time: In order to partner it seemed like organizations would require more time than we had to offer (eight months) to prepare for the partnership • How could additional time be built into the lab process to provide partners with the space they require to ‘get set up’ for commitment?

• Process uncertainty: Although we could provide them with a rough sketch of what the lab was all about and how it would unfold, we also needed to be honest in sharing that it would be an iterative and emergent process. • What are some ways a social innovation process, which may be new and unknown territory for a project partner, be shared that build understanding and feelings of security on the part of the partner?

• Deliverable uncertainty: Although we could give some general guidelines as to what a partner could expect in terms of deliverables (promising prototypes to be scaled), we could not give specifics. • How can project partners be supported in ‘taking a leap of faith’ and embarking on a social innovation process without knowledge of exact deliverables? • ‘New Kid on the Block’ perception of Shift Lab: When we were approaching possible partners, the Shift Lab was not as established (only two years old by this point) and we felt we were often perceived as the ‘new kid on the block’. There was not the time required to build relationships and trust with project partners. • How can time and funds be built into the social innovation process to create space for relationships and trust to be built with possible partners?

Pivoting to supply-side innovation

In the pivot, the Stewardship Team opted to focus on four diverse design challenges that seemed relevant to the Edmonton context. They then worked to seek out possible ‘adopters’ of the prototypes that emerged using two strategies: 1) a community showcase event; and 2) building out an Innovation Manager role.

Community showcase event

In late October 2019, we held a community showcase event in the last cycle of Shift Lab 2.0 at Norquest College. At this event, Core Teams had the opportunity to showcase their prototypes and get feedback from community members. More than 50 community members, including representatives from municipal and provincial governments, educational, technology, faith and non-profit sectors were in attendance.

Prototype showcase at Norquest College

Innovation manager role

Three innovation managers were hired in the last cycle of Shift Lab 2.0. Their role was to assist with the ‘implementation’ side of the prototypes that emerged from the process. Implementation involves further refining, testing, and adapting prototypes to prepare them for piloting and eventually adoption. Essentially, innovation managers help prototypes move from ideas to minimum viable pilots. Implementation managers were responsible for exploring the following questions:

• What minimum resources are required to pilot an intervention? • Who might be best to implement? • What are the readiness factors for organizations piloting an intervention? • How much more iteration is required? • What lean start-up principles and tools can be used to support implementation?

This role seems to hold great promise in supporting supplyside innovations and so far seems to have allowed the prototypes from Shift Lab 2.0 to move much further and faster than the prototypes in Shift Lab 1.0. Additionally, learnings from this innovation make an important contribution to the broader social innovation ecosystem. We have already heard of other lab practitioners planning to incorporate a similar approach in labs they steward.

Key things that have made this role successful

• Securing additional funding to support innovation managers to continue their work of scaling prototypes even after the lab process had ended • Finding the right people to do the job — people who are highly organized, excellent communicators, persistent, and have a balance of vision and a process mindset on how to get there • Trust in people: The innovation managers, who all had human-services experience, were trusted to be sensitive to the cultural context of the process, the perspectives shared and the outcomes.

Questions that emerged

• How true to the original prototype form does the pilot have to be? Who has the authority to make decisions around this? • How do we navigate ownership of the prototypes when they do scale? How do we honor the role of the Core

Teams who built the original ideas and may or may not continue to be involved in implementation? • Is the extra time, effort, and cost associated with the implementation manager role worth it? Or is it simply another ‘patch’ to address the deeper flaws in supply-side innovation approaches (i.e. Why don’t people pick up our ideas?)?

“I don’t know that doing a supply-side innovation is holding us back. The innovation manager is going well … and has been an innovation in and of itself. Although doing a supply-side lab is often perceived as a problem, for us it is not really seeming like a problem!” — Shift Lab Steward

Prototype showcase at Norquest College

Building Capacity Within The Social Innovation Ecosystem

The immense contribution this lab makes to the broader social innovation ecosystem cannot be undervalued. The structure of the lab methodology lends well to building capacity within the local social innovation ecosystem in Edmonton. Both Core Team and Stewardship members expressed learning a great deal about using social innovation processes to tackle complex social challenges.

• Members of the Stewardship Team gained experience implementing a social innovation process and are now even more prepared and better equipped to harness that to design and implement future social innovation processes • The majority of Core Team members reported participation in the lab process increased both their understanding of a design approach to change and their ability to apply design skills

This knowledge has, and will continue to, be shared widely within the local, provincial, and national social innovation ecosystems. Publications and tools created throughout the lab process are available on the Shift Lab website and used regularly by others working in the ecosystem. Additionally, members of the Stewardship Team have been invited to speak across the country about their work, what they’ve learned, and the unique methodology employed.

Evaluating Behavior Change, Racism, and The Sleepy Middle

One of the core objectives of Shift Lab 2.0 was for lab participants to better understand approaches to behavior change, racism, and the Sleepy Middle in an effort to design solutions that support less racist behaviours. In addition to drawing on their personal experiences, the lab participants explored these subject areas in a variety of ways including small and large group work during sprints, reading research on the topics, sharing stories, and conducting their own “scrappy” research. Below is a summary of (some) of the key insights that emerged from Core Team members. Other insights from Stewards are woven throughout the report.

Practices that support behavior change

Core Team members discussed gaining insights on behaviour change through participation in the sprints. They had an opportunity to take in content, explore behavior change frameworks, and reflect on their own experiences related to behaviour change. They also had an opportunity to ‘try out’ what they were learning within their groups — reflecting on how it went, adjusting their practices, and then trying again. This iterative, reflective learning process appeared to be rich and enjoyable for participants, yielding new insights and revelations they could incorporate into their personal and work lives.

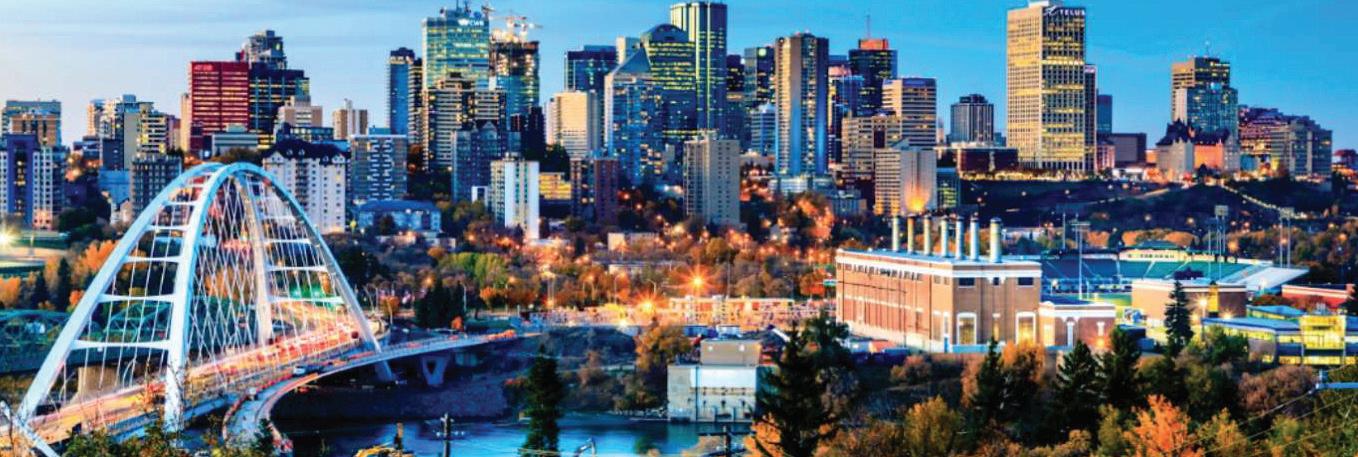

amiskwaciywaskahikan

The following emerged as key practices thought to support behaviour change in the Sleepy Middle related to racism:

• Empathy: A critical component in building mutual understanding across difference. Important to seek to understand the ‘other’ — who they are, their values, their environment, what ‘safe space’ is for them. Relationship is key.

“My awareness of my need to listen more than speak and negotiating that balance” — Core Team Member

“They don’t know they are sleepy, waking up is the most ‘sensitive’ experience” — Core Team Member

“It doesn’t matter how much you disagree with someone’s ideology, you have to recognize them as a human being. It’s the only way.” — Steward

• Practice: Change takes effort, time, and is non linear.

Repetition builds anti-racist “muscle memory” that participants can draw upon in the future.

“Behaviour change is about practice and not one-off disruptions” — Core Team Member, Sprint 2

“Change isn’t always linear. The journey to change is just as important sometimes” — Core Team Member

• Reflexivity: “Turning your gaze inwards,” checking your own biases, building self-awareness and open mindedness, understanding your own reactions, checking privilege, and learning along the way by reading, exploring and talking to other people.

“Being mindful of how your power can unintentionally take away from other’s power” — Core Team Member • Nourishment: Take care of yourself and others, being mindful of what you and they need to do the work well

“Nourish your spirit, heart, and mind continuously” — Core Team Member

• Patience: Meeting people where they are at and having compassion for others regardless of where they are at.

“Everyone is in a different place in their learning journey” — Core Team Member

“I need to be okay that where I am at right now is not where I will end up - and feel no blame” — Core Team Member

• Seek Positive Approaches: Shame doesn’t teach!

Creating safe spaces for conversation is key. Humour can be used as an entry point to something deeper.

“It can’t be too serious or accusatory, need to ensure their safety to open up and learn” — Core Team Member

• Keep it Simple and Subtle: A promising approach that uses gentle nudges, removes barriers, and attempts to make it easy to ‘try something new’. Drip campaigns seem to hold promise.

“Meet them where they are at’ means making it easy and having multiple on ramps for [different] levels of wokeness.” — Core Team Member