Persuasion:

Theory and Research Third Edition – Ebook PDF Version

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/persuasion-theory-and-research-third-edition-ebook-p df-version/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Advertising Research: Theory & Practice 2nd Edition –Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/advertising-research-theorypractice-2nd-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/interpretative-phenomenologicalanalysis-theory-method-and-research-ebook-pdf-version/

Introduction to 80×86 Assembly Language and Computer Architecture – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/introduction-to-8086-assemblylanguage-and-computer-architecture-ebook-pdf-version/

Strategy: An Introduction to Game Theory (Third Edition) 3rd Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/strategy-an-introduction-to-gametheory-third-edition-3rd-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

(eBook PDF) Personality: Theory and Research, 14th Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/ebook-pdf-personality-theory-andresearch-14th-edition/

Handbook of Attachment, Third Edition : Theory, Research, and Clinical

https://ebookmass.com/product/handbook-of-attachment-thirdedition-theory-research-and-clinical/

Reading Statistics and Research – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/reading-statistics-and-researchebook-pdf-version/

Understanding Business Ethics Third Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/understanding-business-ethicsthird-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

Introduction to Corrections Third Edition E-book PDF Version – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/introduction-to-corrections-thirdedition-e-book-pdf-version-ebook-pdf-version/

Detailed Contents

Preface

1 Persuasion, Attitudes, and Actions

The Concept of Persuasion

About Definitions: Fuzzy Edges and Paradigm Cases

Five Common Features of Paradigm Cases of Persuasion

A Definition After All?

The Concept of Attitude

Attitude Measurement Techniques

Explicit Measures

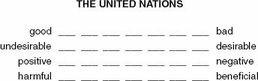

Semantic Differential Evaluative Scales

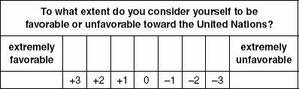

Single-Item Attitude Measures

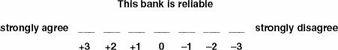

Features of Explicit Measures

Quasi-Explicit Measures

Implicit Measures

Summary

Attitudes and Behaviors

The General Relationship

Moderating Factors

Correspondence of Measures

Direct Experience

Summary

Encouraging Attitude-Consistent Behavior

Enhance Perceived Relevance

Induce Feelings of Hypocrisy

Encourage Anticipation of Feelings

Summary

Assessing Persuasive Effects

Attitude Change

Beyond Attitude Change

Conclusion For Review

Notes

2 Social Judgment Theory

Judgments of Alternative Positions on an Issue

The Ordered Alternatives Questionnaire

The Concept of Ego-Involvement

Ego-Involvement and the Latitudes

Measures of Ego-Involvement

Size of the Ordered Alternatives Latitude of Rejection

Own Categories Procedure

Reactions to Communications

Assimilation and Contrast Effects

Attitude Change Effects

Assimilation and Contrast Effects Reconsidered

The Impact of Assimilation and Contrast Effects on Persuasion

Ambiguity in Political Campaigns

Adapting Persuasive Messages to Recipients Using Social Judgment Theory

Critical Assessment

The Confounding of Involvement With Other Variables

The Concept of Ego-Involvement

The Measures of Ego-Involvement

Conclusion For Review

Notes

3 Functional Approaches to Attitude A Classic Functional Analysis

Subsequent Developments

Identifying General Functions of Attitude

Assessing the Function of a Given Attitude Influences on Attitude Function

Individual Differences

Attitude Object

Situational Variations

Multifunctional Attitude Objects Revisited

Adapting Persuasive Messages to Recipients: Function Matching

The Persuasive Effects of Matched and Mismatched Appeals

Explaining the Effects of Function Matching

Commentary

Generality and Specificity in Attitude Function Typologies

Functional Confusions

Some Functional Distinctions

Conflating the Functions

Reconsidering the Assessment and Conceptualization of Attitude Function

Assessment of Attitude Function Reconsidered

Utilitarian and Value-Expressive Functions

Reconsidered

Summary

Persuasion and Function Matching Revisited

Reviving the Idea of Attitude Functions

Conclusion For Review

Notes

4 Belief-Based Models of Attitude

Summative Model of Attitude

The Model

Adapting Persuasive Messages to Recipients Based on the Summative Model

Alternative Persuasive Strategies

Identifying Foci for Appeals

Research Evidence and Commentary

General Correlational Evidence

Attribute Importance

Belief Content

Role of Belief Strength

Scoring Procedures

Alternative Integration Schemes

The Sufficiency of Belief-Based Analyses

Persuasive Strategies Reconsidered

Belief Strength as a Persuasion Target

Belief Evaluation as a Persuasion Target

Changing the Set of Salient Beliefs as a Persuasion Mechanism

Conclusion For Review

Notes

5 Cognitive Dissonance Theory

General Theoretical Sketch

Elements and Relations

Dissonance

Factors Influencing the Magnitude of Dissonance

Means of Reducing Dissonance

Some Research Applications

Decision Making

Conflict

Decision and Dissonance

Factors Influencing the Degree of Dissonance

Dissonance Reduction

Regret

Selective Exposure to Information

The Dissonance Theory Analysis

The Research Evidence

Summary

Induced Compliance

Incentive and Dissonance in Induced-Compliance

Situations

Counterattitudinal-Advocacy–Based Interventions

The “Low, Low Price” Offer

Limiting Conditions

Summary

Hypocrisy Induction

Hypocrisy as a Means of Influencing Behavior

Hypocrisy Induction Mechanisms

Backfire Effects

Revisions of, and Alternatives to, Dissonance Theory

Conclusion

For Review

Notes

6 Reasoned Action Theory

The Reasoned Action Theory Model

Intention

The Determinants of Intention

Attitude Toward the Behavior

Injunctive Norm

Descriptive Norm

Perceived Behavioral Control

Weighting the Determinants

The Distinctiveness of Perceived Behavioral Control

The Predictability of Intention Using the RAT Model

Influencing Intentions

Influencing Attitude Toward the Behavior

The Determinants of AB

Changing AB

Influencing the Injunctive Norm

The Determinants of IN

Changing IN

Influencing the Descriptive Norm

The Determinants of DN

Changing DN

Influencing Perceived Behavioral Control

The Determinants of PBC

Changing PBC

Altering the Weights

Intentions and Behaviors

Factors Influencing the Intention-Behavior Relationship

Correspondence of Measures

Temporal Stability of Intentions

Explicit Planning

The Sufficiency of Intention

Adapting Persuasive Messages to Recipients Based on Reasoned Action Theory

Commentary

Additional Possible Predictors

Anticipated Affect

Moral Norms

The Assessment of Potential Additions

Revision of the Attitudinal and Normative Components

The Attitudinal Component

The Normative Components

The Nature of the Perceived Control Component

PBC as a Moderator

Refining the PBC Construct

Conclusion

For Review

Notes

7 Stage Models

The Transtheoretical Model

Decisional Balance and Intervention Design

Decisional Balance

Decisional Balance Asymmetry

Implications of Decisional Balance Asymmetry

Self-Efficacy and Intervention Design

Intervention Stage-Matching

Self-Efficacy Interventions

Broader Concerns About the Transtheoretical Model

The Distinctive Claims of Stage Models

Other Stage Models

Conclusion For Review

Notes

8 Elaboration Likelihood Model

Variations in the Degree of Elaboration: Central Versus Peripheral Routes to Persuasion

The Nature of Elaboration

Central and Peripheral Routes to Persuasion

Consequences of Different Routes to Persuasion

Factors Affecting the Degree of Elaboration

Factors Affecting Elaboration Motivation

Personal Relevance (Involvement)

Need for Cognition

Factors Affecting Elaboration Ability

Distraction

Prior Knowledge

Summary

Influences on Persuasive Effects Under Conditions of High Elaboration: Central Routes to Persuasion

The Critical Role of Elaboration Valence

Influences on Elaboration Valence

Proattitudinal Versus Counterattitudinal Messages

Argument Strength

Other Influences on Elaboration Valence

Summary: Central Routes to Persuasion

Influences on Persuasive Effects Under Conditions of Low Elaboration: Peripheral Routes to Persuasion

The Critical Role of Heuristic Principles

Varieties of Heuristic Principles

Credibility Heuristic

Liking Heuristic

Consensus Heuristic

Other Heuristics

Summary: Peripheral Routes to Persuasion

Multiple Roles for Persuasion Variables

Adapting Persuasive Messages to Recipients Based on the ELM

Commentary

The Nature of Involvement

Argument Strength

One Persuasion Process?

The Unimodel of Persuasion

Explaining ELM Findings

Comparing the Two Models

Conclusion

For Review

Notes

9 The Study of Persuasive Effects

Experimental Design and Causal Inference

The Basic Design

Variations on the Basic Design

Persuasiveness and Relative Persuasiveness

Two General Challenges in Studying Persuasive Effects

Generalizing About Messages

Ambiguous Causal Attribution

Nonuniform Effects of Message Variables

Designing Future Persuasion Research

Interpreting Past Persuasion Research

Beyond Message Variables

Variable Definition

Message Features Versus Observed Effects

The Importance of the Distinction

Conclusion

For Review

Notes

10 Communicator Factors

Communicator Credibility

The Dimensions of Credibility

Factor-Analytic Research

Expertise and Trustworthiness as Dimensions of Credibility

Factors Influencing Credibility Judgments

Education, Occupation, and Experience

Nonfluencies in Delivery

Citation of Evidence Sources

Position Advocated

Liking for the Communicator

Humor

Summary

Effects of Credibility

Two Initial Clarifications

Influences on the Magnitude of Effect

Influences on the Direction of Effect

Liking

The General Rule

Some Exceptions and Limiting Conditions

Liking and Credibility

Liking and Topic Relevance

Greater Effectiveness of Disliked Communicators

Other Communicator Factors

Similarity

Similarity and Liking

Similarity and Credibility: Expertise Judgments

Similarity and Credibility: Trustworthiness Judgments

Summary: The Effects of Similarity

Physical Attractiveness

Physical Attractiveness and Liking

Physical Attractiveness and Credibility

Summary

About Additional Communicator Characteristics

Conclusion

The Nature of Communication Sources

Multiple Roles for Communicator Variables

For Review

Notes

11 Message Factors

Message Structure and Format

Conclusion Omission

Recommendation Specificity

Narratives

Complexities in Studying Narrative and Persuasion

The Persuasive Power of Narratives

Factors Influencing Narrative Persuasiveness

Entertainment-Education

Summary

Prompts

Message Content

Consequence Desirability

One-Sided Versus Two-Sided Messages

Gain-Loss Framing

Overall Effects

Disease Prevention Versus Disease Detection

Other Possible Moderating Factors

Summary

Threat Appeals

Protection Motivation Theory

Threat Appeals, Fear Arousal, and Persuasion

The Extended Parallel Process Model

Summary

Beyond Fear Arousal

Sequential Request Strategies

Foot-in-the-Door

The Strategy

The Research Evidence Explaining FITD Effects

Door-in-the-Face

The Strategy

The Research Evidence

Explaining DITF Effects

Conclusion For Review

Notes

12 Receiver Factors

Individual Differences

Topic-Specific Differences

General Influences on Persuasion Processes

Summary

Transient Receiver States

Mood

Reactance

Other Transient States

Influencing Susceptibility to Persuasion

Reducing Susceptibility: Inoculation, Warning, Refusal

Skills Training

Inoculation

Warning

Refusal Skills Training

Increasing Susceptibility: Self-Affirmation

Conclusion For Review

Notes

References

Author Index

Subject Index

About the Author

Preface

This preface is intended to provide a general framing of this book and is particularly directed to those who already have some familiarity with the subject matter. Such readers will be able to tell at a glance that this book is in many ways quite conventional (in the general plan of the work, the topics taken up, and so forth) and will come to see the inevitable oversimplifications, bypassed subtleties, elided details, and suchlike. Because this book is pitched at roughly the level of a graduateundergraduate course, it is likely to be defective both by having sections that are too shallow or general for some and by having segments that are too detailed or technical for others; the hope is that complaints are not too badly maldistributed across these two categories. This book aims at a relatively generalized treatment of persuasion; in certain contexts in which persuasion is a central or recurring activity, correspondingly localized treatments of relevant research literatures are available elsewhere, such as for consumer advertising (e.g., Armstrong, 2010) and for certain legal settings (e.g., Devine, 2012). Readers acquainted with the second edition will notice the addition of chapters concerning social judgment theory and stage models, revision of the treatment of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior, and new attention to subjects such as reactance and the use of narratives as vehicles for persuasion.

This edition also gives special attention to questions of message adaptation. One broad theme that recurs in theoretical treatments of persuasion is the need to adapt persuasive messages to their audiences: different recipients may be persuaded by different sorts of messages. Thus one way of approaching any given theoretical framework for persuasion is to ask how it identifies ways in which messages might be adapted to audiences. For this reason, a number of the chapters concerning theoretical perspectives contain a section addressing this issue (and, as appropriate, this matter also arises in other chapters).

Some readers will see the relationship of this theme to concepts such as “message tailoring” and “message targeting.” In the research literature, these labels have often been used to apply quite loosely to any sort of way in which messages are adapted to (customized for) recipients, although sometimes there have been efforts to use different labels to describe different degrees or kinds of message customization (e.g., sometimes

“targeting” is described as adaptation on the basis of group-level characteristics, whereas “tailoring” is based on individual-level properties). But no matter the label, there is a common underlying conceptual thread here, namely, that different kinds of messages are likely to be persuasive for different recipients and hence to maximize persuasiveness, messages should be adapted to their audiences.

As should be apparent, there are quite a few different bases for such adaptation: messages might be adapted to the audience’s literacy level, cultural background, values, sex, degree of extroversion, age, regulatory focus, level of self-monitoring, or race/ethnicity. A message may be customized to the audience’s current psychological state as described by, say, reasoned action theory (e.g., is perceived behavioral control low?), protection motivation theory (is perceived vulnerability sufficiently high?), or the transtheoretical model (which stage is the recipient in?). It may be superficially personalized (e.g., by mentioning the recipient’s name in a direct mail appeal), mention shared attitudes not relevant to the advocacy subject, and so on.

For this reason, it is not fruitful to pursue questions such as “are tailored messages more persuasive than non-tailored messages?” because the answer is virtually certain to be “it depends” if nothing else, the answer may vary depending on the basis of tailoring. For example, it might be that adapting messages through superficial personalization typically makes very little difference to persuasiveness, but adapting messages by matching the message’s appeals to the audience’s core values could characteristically substantially enhance persuasiveness.

Still, the manifest importance of adapting messages to recipients recommends its prominence. Aristotle was right (in the Rhetoric): the art of persuasion consists of discerning, in any particular situation, the available means of persuasion. Those means will vary from case to case, and hence maximizing one’s chances for persuasion will require adapting one’s efforts to the circumstance at hand. Whether one calls this message adaptation, message tailoring, message targeting, message customization, or something else, the core idea is the same: different approaches are required in different persuasive circumstances.

Adding material (whether about audience adaptation or other matters) is an easy decision; omitting material is not, because one fears encouraging the loss of good (if imperfect) ideas. Someone somewhere once pointed out

that in the social and behavioral sciences, findings and theories often seem to just fade away, not because of any decisive criticisms or counterarguments but rather because they seem to be “too old to be true.” This apt observation seems to me to identify one barrier to social-scientific research synthesis, namely, that useful results and concepts somehow do not endure but rather disappear making it impossible for subsequent work to exploit them.

As an example: If message assimilation and contrast effects are genuine and have consequences for persuasive effects, then although there is little research attention being given to the theoretical framework within which such phenomena were first clearly conceptualized (social judgment theory) we need somehow to ensure that our knowledge of these phenomena does not evaporate. Similarly, although it has been some time since substantial work was done on the question of the dimensions underlying credibility judgments, the results of those investigations (the dimensions identified in those studies) should not thereby fail to be mentioned in discussions of credibility research.

To sharpen the point here: It has been many years since the islets of Langerhans (masses of endocrine cells in the pancreas) were first noticed, but medical textbooks do not ignore this biological structure. Indeed, it would be inconceivable to discuss (for example) mechanisms of insulin secretion without mentioning these structures. Now I do not mean to say that social-scientific phenomena such as assimilation and contrast effects are on all fours with the islets of Langerhans, but I do want to suggest that premature disappearance of social-scientific concepts and findings seems to happen all too easily. Without forgetting how grumpy old researchers can sometimes view genuinely new developments (“this new phenomenon is just another name for something that used to be called X”), one can nevertheless acknowledge the real possibility that “old” knowledge can somehow be lost, misplaced, insufficiently understood, unappreciated, or overlooked.

It is certainly the case that the sheer amount of social-scientific research output makes it difficult to keep up with current research across a number of topics, let alone hold on to whatever accumulated information there might be. In the specific case of persuasion research which has seen an explosion of interest in recent years the problem is not made any easier by the relevant literature’s dispersal across a variety of academic locales. Yet somehow the insights available from this research and theorizing must

not be lost.

Unfortunately, there are not appealing shortcuts. One cannot simply reproduce others’ citations or research descriptions with an easy mind (for illustrations of the attendant pitfalls, see Gould, 1991, pp. 155–167; Gould, 1993, pp. 103–105; Tufte, 1997, p. 71). One hopes that it would be unnecessary to say that as in the previous editions, I have read everything I cite. I might inadvertently misrepresent or misunderstand, but at least such flaws will be of my own hand.

Moreover, customary ways of drawing general conclusions about persuasive effects can be seen to have some important shortcomings. One source of difficulty here is a reliance on research designs using few persuasive messages, a matter addressed in Chapter 9. Here I will point out only the curiosity that generalizations about persuasive message effects generalizations intended to be general across both persons and messages have commonly been offered on the basis of data from scores or hundreds of human respondents but from only one or two messages. One who is willing to entertain seriously the possibility that the same manipulation may have different effects in different messages should, with such data in hand, be rather cautious.

Another source of difficulty has been the widespread misunderstandings embedded in common ways of interpreting and integrating research findings in the persuasion literature. To illuminate the relevant point, consider the following hypothetical puzzle:

Suppose there have been two studies of the effect on persuasive outcomes of having a concluding metaphor (versus having an ordinary conclusion that does not contain a metaphor) in one’s message, but with inconsistent results. In Study A, conclusion type made a statistically significant difference (such that greater effectiveness is associated with the metaphorical conclusion), but Study B failed to replicate this result.

In Study A, the participants were female high school students who read a written communication arguing that most persons need from 7 to 9 hours of sleep each night. The message was attributed to a professor at the Harvard Medical School; the communicator’s identification, including a photograph of the professor (an attractive, youthful-looking man), was provided on a cover sheet immediately

preceding the message. The effect of conclusion type on persuasive outcome was significant, t(60) = 2.35, p < .05: Messages with a concluding metaphor were significantly more effective than messages with an ordinary (nonmetaphorical) conclusion.

In Study B, the participants were male college undergraduates who listened to an audio message that used a male voice. The message advocated substantial tuition increases (of roughly 50% to 60%) at the students’ university and presented five arguments to show the necessity of such increases. The communicator was described as a senior at the university, majoring in education. Although the means were ordered as in Study A, conclusion type did not significantly affect persuasive outcome, t(21) = 1.39, ns.

Why the inconsistency (the failure to replicate)?

A typical inclination has been to entertain possible explanatory stories based on such differences as the receivers’ sex (“Women are more influenced by the presence of a metaphorical conclusion than are men”), the medium (“Metaphorical conclusions make more difference in written messages than in oral messages”), the advocated position (“Metaphorical conclusions are helpful in proattitudinal messages but not in counterattitudinal ones”), and so on. But for this hypothetical example, those sorts of explanatory stories are misplaced. Not only is the direction of effect identical in Study A and Study B (each finds that the concludingmetaphor message is more effective) but also the size of the advantage enjoyed by the concluding-metaphor message is the same in the two studies (expressed as a correlation, the effect size is .29). The difference in the level of statistical significance achieved is a function of the difference in sample size, not any difference in effect size.

Happily, recent years have seen some progress in the diffusion of more careful understandings of statistical significance, effect sizes, statistical power, confidence intervals, and related matters. (Some progress but not enough. It remains distressingly common that even graduate students with statistical training can reason badly when faced with a problem such as that hypothetical.) With the hope of encouraging greater sensitivity concerning specifically the magnitude of effects likely to be found in persuasion research, I have tried to include mention of average effect sizes where appropriate and available.

But there is at present something of a disjuncture between the available methods for describing research findings (in terms of effect sizes and confidence intervals) and our theoretical equipment for generating predictions. Although research results can be described in specific quantitative terms (“the correlation was .37”), researchers are currently prepared to offer only directional predictions (“the correlation will be positive”). Developing more refined predictive capabilities is very much to be hoped for, but significant challenges lie ahead (for some discussion, see O’Keefe, 2011a).

Even with increasing attention to effect sizes and their meta-analytic treatment, however, we are still not in a position to do full justice to the issues engaged by the extensive research literature in persuasion, given the challenges in doing relevant, careful, reflective research reviews. For example, research reviews all too often exclude unpublished studies, despite wide recognition of publication biases favoring statistically significant results (see, e.g., Dwan, Gamble, Williamson, Kirkham, & the Reporting Bias Group, 2013; Ferguson & Heene, 2012; Ioannidis, 2005, 2008). Similarly, meta-analytic reviews too often rely on fixed-effect analyses rather than the random-effects analyses appropriate where generalization is the goal (for discussion, see Card, 2012, pp. 233–234). All these considerations conspire to encourage a rather conservative approach to the persuasion literature (conservative in the sense of exemplifying prudence with respect to generalization), and that has been the aim in this treatment.

Of course, one cannot hope to survey the range of work covered here without errors, oversights, and unclarities. These have been reduced by advice and assistance from a number of quarters. Students in my persuasion classes have helped make my lectures and so this book clearer than otherwise might have been the case. Many good insights and suggestions came from the reviewers arranged by Sage Publications: Jonathan H. Amsbary, William B. Collins, Julia Jahansoozi, Bonnie Kay, Andrew J. Kirk, Susan L. Kline, Sanja Novitsky, Charles Soukup, Kaja Tampere, and Beth M. Waggenspack. Jos Hornikx also provided especially useful commentary on drafts of this edition’s chapters. And I thank Barbara O’Keefe both for helpful conversation and for an unceasingly interesting life: “Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale / Her infinite variety.”