Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/crossed-wires-the-conflicted-history-of-us-telecommu nications-from-the-post-office-to-the-internet-dan-schiller/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Post-Digital, Post-Internet Art and Education: The Future is All-Over Kevin Tavin

https://ebookmass.com/product/post-digital-post-internet-art-andeducation-the-future-is-all-over-kevin-tavin/

Purpose and Power: US Grand Strategy from the Revolutionary Era to the Present Stoker

https://ebookmass.com/product/purpose-and-power-us-grandstrategy-from-the-revolutionary-era-to-the-present-stoker/

History of South Africa: From 1902 to the Present Thula Simpson

https://ebookmass.com/product/history-of-south-africafrom-1902-to-the-present-thula-simpson/

Toxic: A History Of Nerve Agents, From Nazi Germany To Putin’s Russia 1st Edition Edition Dan Kaszeta

https://ebookmass.com/product/toxic-a-history-of-nerve-agentsfrom-nazi-germany-to-putins-russia-1st-edition-edition-dankaszeta/

The Op-Ed Novel: A Literary History of Post-Franco Spain Bécquer Seguín

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-op-ed-novel-a-literary-historyof-post-franco-spain-becquer-seguin/

The History of Hylomorphism: From Aristotle to Descartes 1st Edition David Charles

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-history-of-hylomorphism-fromaristotle-to-descartes-1st-edition-david-charles/

The Internet of Things John Davies

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-internet-of-things-john-davies/

The Synagogue of Satan Dan Fournier

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-synagogue-of-satan-danfournier/

From the Ashes of History Adam B. Lerner

https://ebookmass.com/product/from-the-ashes-of-history-adam-blerner/

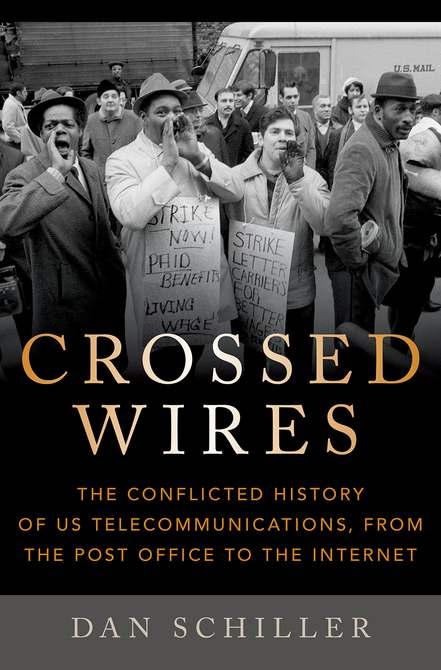

Crossed Wires

DAN SCHILLER

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schiller, Dan, 1951- author.

Title: Crossed wires : the con icted history of US telecommunications, from the post o ce to the Internet / Dan Schiller.

Description: New York, NY, United States of America. : Oxford University Press, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identi ers: LCCN 2022040666 (print) | LCCN 2022040667 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197639238 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197639252 (epub) | ISBN 9780197639245 | ISBN 9780197639269 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Telecommunications—United States—History. Classi cation: LCC TK5102.3.U6 S35 2023 (print) | LCC TK5102.3.U6 (ebook) | DDC 621.3820973—dc23/eng/20221109

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022040666

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022040667

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197639238.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

To My Marvelous Family

PART I. ANTIMONOPOLY

1. Paths into an Imperial Republic: Posts and Telegraphs

2. Antimonopoly, in the Country and the City

3. Business Realignment, Federal Intervention, Class Confrontation

PART II. PUBLIC UTILITY

5.

7.

8.

PART III. DIGITAL CAPITALISM

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to the people who have helped me with the thinking and writing that have gone into this book, which I have worked on by ts and starts throughout most of my academic life.

As a complement to my PhD studies in Communications at the University of Pennsylvania, I enrolled in several graduate History seminars, out of which came a lifelong engagement with radical history. Frequent and o en intense conversations with classmates, above all, with Marcus Rediker and Nancy Hewitt, were formative. Power was not unconditional: While contradictory social relations remained dominative, they were also far from one-dimensional. e views, beliefs, and actions of the dispossessed would be matters of enduring consequence for my research in communications history.

Across town at Temple University, beginning in 1979 I became one of a group of faculty members focusing on the political economy of communications. In addition to her research on “movies and money,” Janet Wasko knew the realities of working for a big media corporation at rst-hand. Vincent Mosco had studied broadcasting and was researching new media; he also brought a fresh experience of Washington, DC, telecommunications policymaking. Dallas Smythe’s engagement with telecommunications—and radical politics—stretched back to the 1930s, and his bibliographic reach was remarkable. In this energizing milieu, I originated my rst courses on telecommunications history and began to supervise talented doctoral students.

A er reading a dra of my book, Telematics and Government (1982), Vinny urged me to undertake a full-blown revision of US telecommunications history. Our conversations about this topic were many, and fruitful. How, though, might I develop a second book about telecommunications—a subject universally written about from the top down, including by me in my earlier work—while ful lling my goal of writing radical social history? Between visits to the National Archives I pondered this question.

In 1986–1987, Everette E. Dennis arranged for me to enjoy a year-long fellowship at Columbia’s University’s then Gannett Center for Media Studies. A tributary of the research I pursued there streamed into this book, from days spent in the AT&T archives—then located at 195 Broadway in New York City. e talented research assistant David Stebenne, now a senior historian and legal scholar, performed invaluable research at Columbia’s libraries.

My book’s next way-station was UCLA’s perfumed campus. Exchanges with Chris Borgman and Elaine Svenonius in the then-Graduate School of Library and Information Science enabled me to cultivate some new thinking. e late historians Gary Nash and Alex Saxton welcomed me, and kept me close to radical social history—as did historian and librarian Cindy Shelton. Courses o ered through UCLA’s Communication program permitted me to continue teaching telecommunications history to undergraduate students.

In 1990 my book moved down the freeway to UCSD. My student, Meighan Maguire, produced an outstanding UCSD dissertation on telephone development in San Francisco. For an independent study class under my supervision, undergraduate Karen Frazer visited the National Archives and shared the documents she copied there on the EEOC case against AT&T. Rick Bonus and Corynne McSherry, each now advanced in illustrious careers, gave me dedicated research assistance. Departmental colleagues Ellen Seiter and Yuezhi Zhao listened, and o ered questions, advice, criticism, and friendship. My doctoral students at UCSD were a constant source of inspiration. Michael Bernstein and other friends in the history and literature departments nurtured common interests and shared the burdens of our common work environment. By now I had determined through extensive archival work and teaching that the history of US telecommunications rested on dynamic and complex sociopolitical power relations: to be valid, it could not be written as a top-down exercise. e late Antonia Meltzo helped me to see the importance of carrying the project forward, and to nd a basis for doing so.

We migrated in 2001 to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In the stacks of UIUC’s Main Library, I found wonderful and unexpected friends under Dewey Decimal Number 384. Alistair Black and Bonnie Mak shared the joys and travails of historical study. Linda Smith o ered helpful counsel. Bob McChesney and I enjoyed many discussions—sometimes with students—about telecommunications, media, and power. Inger Stole, John Nerone, Christian Sandvig, and Jim Barrett and the late Jenny Barrett helped li me out of received thinking. Intellectual refreshment and reintegration came from doctoral students based in multiple departments and disciplines. en-UIUC Chancellor Richard Herman provided resources for me to hold a conference on telecommunications history, which then-GSLIS Dean John Unsworth, an enthusiastic supporter of this project, helped me organize, under the auspices of UIUC’s Center for Advanced Study. CAS Associate Director Masumi Iriye and sta er Liesel Wildhagen were key in ensuring that this event came o successfully. Info editor and long-time telecommunications analyst Colin Blackman both participated in the meeting and opened his journal to papers presented there. Special thanks to Jason Kozlowski and ShinJoung Yeo for imaginative and conscientious research assistance.

In 2016, we moved to Santa Fe, where I worked on this book full-time for six additional years. One portion of it was presented as lectures to Beijing University’s Global Fellowship Program, under the title “Networks and the Age of Nixon.” I am grateful for the invitation to o er these lectures, and to the faculty and sta at Beijing University who arranged and hosted my visit. I also cherish the memory of meal times at Beida, when I was able to meet with a number of communications graduate students and to explain my research approach. I am thankful, above all to my friend and former colleague Yuezhi Zhao, to have had opportunity to make this and other visits to China.

Andrew Calabrese and Janice Peck at the University of Colorado, Boulder have been congenial hosts for presentations based on this book; their own respective analyses of telecommunications and media are buoys for critical thought. So too Rick Maxwell, a kindred spirit who has pioneered study of the media’s systemic damage to the environment. Vinny Mosco read chunks of this book in dra form and gave me numerous valuable comments and suggestions. Richard John o ered detailed notes a er reading a chapter; forwarded me a couple of relevant sources; and invited me to present a portion of this work at a Newberry Library seminar. Yuezhi Zhao read a long chapter dra and helpfully advised me to stick to my guns. I was fortunate to present an early version of one chapter at an annual meeting of the Organization of American Historians.

At Bolerium Books in San Francisco, I am indebted to John, Joe, and Alexander, who alerted me to literally dozens of fugitive primary sources. Caroline Nappo, who coauthored an article with me on postal and communications workers, generously permitted me to use modi ed excerpts from that piece in this book. ShinJoung Yeo and James Jacobs repeatedly took time from their own work to help me with thorny bibliographic issues. Jim Barrett has been a great friend to this book and its author: his vast knowledge of labor and working class history has both saved me from errors and strengthened my story. anks to Victor Pickard for critical readings, support, and friendship. For a semester at Annenberg/Penn, where I made a pair of presentations based on portions of this book and taught a rewarding doctoral seminar—thanks both to Barbie Zelizer and, again, to Victor. Hong Guo helped me to persevere through the nal years. e community of doctoral students with whom I have worked has been a mainstay of my life as a scholar and a teacher. Only a couple of them chose to work on telecommunications; but all became a part of this book’s journey. anks to one and all.

I am immeasurably grateful to the archivists and librarians who helped me bear this study forward: without them this book would not exist. Special thanks to Nick Johnson, who granted me access to his exciting and underused papers at the University of Iowa Special Collections. I appreciate Alan Novak’s willingness to grant me an oral history interview; and I thank Monroe Price for facilitating it.

Susan Davis has lived with this project from beginning to end, a witness to the delight of archival discovery and the agony of authorial expression. She has listened to my thoughts as they sought to form, and read and criticized long sections of this book—sometimes to my consternation, always to my bene t. No less, through the years she has greatly deepened my awareness of the historical importance of traditions of vernacular dissent and popular cultural expression. Lucy and Ethan Schiller have never been too busy to ask about “the book” and to o er advice when I requested it. My brother Zach has been a stalwart: being able to rely on him has made a material di erence to my ability to complete this work.

I am grateful to Nico Pfund for keeping faith. During a virulent season my acquisitions editor, James Cook, managed to nd exceptional readers for this manuscript: their learned, detailed, and critical reviews were inestimably valuable for my revision. And, always good-spiritedly, Kaya Learnard met every deadline as she read and formatted the text—a daunting and much-appreciated labor. Modi ed excerpts from the following works by me have been used in Crossed Wires:

Networks and the Age of Nixon. Beijing: Peking University Press, 2018 (Chinese print edition).

“ ‘Let em Move the Mail with Transistors Instead of Brains’: Labour Convergence in Posts and Telecommunications, 1972–3” (coauthored with Caroline Nappo), Work Organisation, Labour and Globalisation 4, 2 (2010). https://www.scienceopen.com/hos ted-document?doi=10.13169/workorgalaboglob.4.2.0010 License at: https://creative commons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

“ e Hidden History of U.S. Public Service Telecommunications, 1919–1956,” Info Vol. 9 Nos. 2/3, March 2007: 17–28. Emerald.

“Social Movement in U.S. Telecommunications: Rethinking the Rise of the Public Service Principle, 1894–1919,” Telecommunications Policy 22 (4), 1998. Emerald.

Introduction

A Missing History

e infamous Chicago Democratic convention of 1968 nearly didn’t happen, because of a telephone strike.

Illinois Bell Telephone Company was to wire up Chicago’s International Amphitheater, the city’s major hotels, and other downtown locations with extra telephone lines and a variety of specialized circuits. News agencies, national newspapers, and regional and network TV broadcasters would ood into Chicago for the media-rich confab, which was scheduled to begin on August 26th. e complex wiring process would require ve weeks to be completed, before the convention could begin.

Nearly 12,000 members of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) walked out at Illinois Bell on May 8, seeking wage gains to make up for high in ation. (1968 saw the greatest strike wave since 1959, and most of the strikes were signi cantly motivated by economic factors.) By early summer, as the strike grew prolonged, Democratic o cials began to worry. Rumors circulated that Miami was being considered as an alternative site. On July 15, the New York Times reported that an IBEW leader hoped “to avoid the embarrassment of Chicago losing the convention because of our dispute.”1

At the last minute—July 23—an extraordinary x was arranged by Democratic Mayor Richard Daley, the Chicago Federation of Labor, and IBEW o cials. Albeit with some reported “dissension,” the city’s own labor movement authorized 300 IBEW members to install much of the needed wiring on a “voluntary basis”—that is, to undercut the strike. Labor leaders vowed to step up their support for the continuing IBEW walkout in other ways, and restrictions were imposed on the volunteers: no work would be supervised by Bell managers; and no circuits would be installed outside the Amphitheater. e convention could proceed, and Democrats breathed sighs of relief.2 is did not end the matter. Descending on Chicago to greet the o cial gathering were thousands of anti-Vietnam War demonstrators. ey were met by 12,000 Chicago police in riot gear, and an additional 15,000 Army and National Guard troops. As the convention got underway, demonstrators and journalists were tear-gassed and clubbed; many demonstrators were dragged o to jail amid a bloody police riot.3

Crossed Wires. Dan Schiller, Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2023. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197639238.003.0001

Yet breaking news of the protest and its repression did not reach the convention oor. CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite recalled, that “delegates had no idea what was happening.” e reason? IBEW volunteers had not installed microwave circuits needed to broadcast live TV outside the Amphitheater, so that videotape needed to be hand-delivered from Lincoln and Grant parks, where much of the violence was occurring, to the Amphitheater miles away. ere, it was processed and broadcast. is arrangement caused delays of an hour or more. When the video was belatedly aired, so that both delegates and tens of millions of other Americans witnessed the events taking place on the streets, uproar ensued. On live television, Connecticut Senator Abraham Ribico called out Mayor Daley’s “Gestapo tactics” to his face. e existing division between pro- and antiwar factions of the Democratic Party widened into a chasm in real time. e convention, a scholar writes, “su ered a political crisis of epic proportions.”4

e IBEW walkout continued until September 21, so that it lasted 137 days all told. Many union members found other jobs as the economic pressures of being without work became acute. ough IBEW o cials urged members to reject Bell’s nal contract o er, in the end they voted to return to work by a nearly two-to-one margin.5

is story reveals that telecommunications may claim an unexpected significance on the historical stage. It also shows that decisions about networking— in this case, about providing microwave circuits for live coverage—may be a function not of engineering but of power relations and political horse-trading. Crossed Wires unearths many such stories. ey illuminate a history that has evolved through contention and struggle. If we would understand these moments of con ict and change, we need to connect them to prevailing social and political power relations. us, the approach adopted here is not to appeal to an overarching economic theory, a managerial vision, a legal concept, a technological necessity, or a civic consensus. My aims are two: to restore the contour lines le by a divided and dominative society upon network development; and to emphasize how recurrent struggles by workers, consumers, and political radicals have also shaped them. e narrative arc of this book is formed by the marks made on telecommunications, again and again, not only by social and political pressures, but by counter-pressures from below and from the sides—as with the Chicago Convention of 1968. *

How may we open the study of telecommunications in this way, across the span of US history? I have adhered to two chief guidelines in developing my arguments. First, my account places networks within a broad historical sweep, and therefore I have needed to consult an extensive secondary scholarship.

Recent revisions to historical understanding o er vital aid to the student of American telecommunications. e territorial conquests on which the US republic was based, and which indigenous peoples experienced and resisted, were essential to the buildouts of postal and telegraph networks. How diversely exploited workers and small farmers came to labor in the shadow of corporate “monopolies” had everything to do with the swelling late nineteenth century movement to reform privately owned telegraphs and telephones. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, struggles to overcome racist and sexist employment discrimination were essential to a rejuvenation of a public utility conception of telecommunications. In short, because historians have enlarged and o en upended received thinking, it has become possible to plot the course of telecommunications di erently.

However, to get close to the ideas and priorities held by the people who built and operated telecommunications systems, and who clamored to have use of them, a second pathway to knowledge is also needed. is dimension of historical recovery has necessitated research in numerous specialized libraries and archives and antiquarian bookstores. Consulting these source collections has been an indispensable counterpart of scouring the secondary scholarship that is reorienting the American past. It has allowed me entrée to yers, pamphlets, underground periodicals, letters, memoranda, and ephemera that circulated below and behind o cial records of events. As a result I have o en been able to learn more about how postal clerks, letter carriers, telegraphers, telephone operators, and other members of a changing network labor force thought about how these networks were organized. eir ideas and actions of course foregrounded, but also went beyond, the terms of their own employment. Workers notably pressed for more inclusive service provision and for alterations to ownership and control; some even pushed for changes to US patent law. eir mostly disremembered e orts are recognized in this book.

In light of these two methodological priorities, I have undertaken a farreaching revision. Each chapter crystallizes a particular era, aspect, or noteworthy episode; cumulatively, my eleven chapters remap more than two centuries of US telecommunications history, from the Post O ce to the internet.

A er decades of neglect, historians have recaptured for the US Post O ce some of its former stature. As Richard R. John demonstrates, this longtime government department both interacted with major political and cultural movements of the early-to-mid nineteenth century and provided institutional foundations for state-building and industrialization. is recognition, vital in itself, does not complete the task of revaluation.

We will see in Chapter 1 that the government Post O ce and, subsequently, the corporate telegraph shared two shaping features. First and foremost, both served a voracious territorial imperialism. Posts and telegraphs were parts of the process of military conquest and settlement, to the west and to the south of North America. Imperialism was, from the outset, a de ning historical feature of the US political economy—and telecommunications networks were bound up in it. Second, these two networks catered for business users; telegraph service in particular placed the communicative needs of the general population distinctly second.

ere were also divergences. Entangled in party politics, during the second half of the 19th century the Post O ce provided an increasingly cheap, e cient, and universal service. For many contemporaries, therefore, it came to exemplify the best side of the postbellum state. e telegraph, by contrast, was a paragon of modern corporate corruption, the center of a web of monopoly predation,nancial machinations, and political in uence-mongering. e government Post O ce and the corporate telegraph thus presented contemporary Americans— who tended to take for granted, even to naturalize, their common imperial role—with a sharply polarized model of network system development. ere was no question as to which system enjoyed greater esteem, as Chapter 2 emphasizes. Uniting under a credo of “antimonopoly,” reform movements aimed to “postalize” the country’s now swi ly evolving telecommunications in their entirety. Negatively, antimonopolists sought to eliminate powerful corporate monopolies, including those of the Western Union Telegraph Company and, slightly later, the American Telephone & Telegraph Company (AT&T). Positively, they hoped to expand access to telegraphs and telephones; to rationalize rates; and, for some of the workers who campaigned under their banner, to improve labor conditions. is movement carried forward for several decades and it increasingly targeted the wondrous third network system that was being established around the telephone.

Not surprisingly, the postalization scheme and its proponents drew obdurate opposition. AT&T was surpassing Western Union, and AT&T’s executives attempted energetically to disarm the antimonopolists. Municipal, state, and federal authorities were all drawn in, and played disparate roles. Episodically, and through moments freighted with contingency, Chapter 3 shows, during the rst two decades of the twentieth century the postalization movement splintered. Key groups of participants—big business users of networks and independent suppliers of telephone service, thousands of which had rushed in to provide telephone service—unevenly reached a separate peace with the giant telephone company. Many telecommunications workers nevertheless continued to struggle for postalization, out of a conviction that the state would be a less onerous employer than a private corporation.

As testimony shows, many wage workers wanted “industrial democracy”; many citizens wanted to curtail corporate power over the polity; many residents wanted telephone access at home. For a period of years culminating in and immediately a er World War I, workers pressed ahead with what proved to be a nal drive for postalization. ey then endured a bitter lesson at the hands of the Post O ce, as the Department actually took over the operation of telegraphs, telephones and cables on grounds of the war emergency. For a one year interval, advised by top executives from AT&T and Western Union, the Post O ce ran the nation’s networks. A er women telephone operators exhibited sustained and disciplined militancy in resisting the Post O ce’s high-handed management—which was concurrently damaged in middle-class public opinion for other reasons—the administration of President Woodrow Wilson decided to reprivatize the wires. is double exercise of state power not only cut out the ground under telegraph and telephone workers, but also nally shattered the popular network imaginary centered on postalization. Already partially hollowed out by defections, a decades-long e ort to restructure telecommunications now collapsed.

Chapter 4 shows, however, that a disparate reform movement commenced virtually at the same moment. New administrative agencies had been established by dozens of states during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries— public utility commissions (PUCs)—and these had helped broker more stable relations between carriers and big business users. A er World War I, some PUCs unexpectedly began to form a locus of substantive change. A scatter of state commissioners chafed at the restraints on e ective regulation that stemmed from what was sometimes termed a “foreign corporation”: AT&T. is vertically and horizontally integrated company was now the country’s largest unit of capital. Its rate structure was beyond their reach; its nancial practices remained mysterious. In the absence of an e ective federal regulator to act as a counterweight, AT&T’s power posed what some intrepid state regulators identi ed as intractable problems of oversight and accountability.

Initially, their challenges to AT&T were o en rhetorical, and lacked political punch. However, in New York City and, above all, Chicago, persistent municipal rate ghts attained expanding importance as political opportunities opened a er the onset of the Great Depression. e economic collapse caused many subscribers to give up their telephones, and AT&T responded by cutting hundreds of thousands of telephone jobs, notably those of women operators, without cutting its generous dividends to investors. ese actions by the telephone monopoly instilled a bottomless antipathy among workers, and created growing support for telecommunications reform. So, paradoxically, did ruinous competition in telegraph service—between Western Union, the market leader, Postal Telegraph, its beleagured rival, and a handful of new radio-telegraph

companies. While these competitors battered one another, and as Western and Postal supplicated their corporate customers with discounts and rebates, already straitened telegraph workers began to protest their pitiful wages and miserable working conditions.

e experimental genius of the Roosevelt government was to establish what was, for a few years, an unusually robust and interventionist Federal Communications Commission (FCC). e FCC investigated and rescued the telecommunications system from what it identi ed as twin evils: monopoly in a telephone industry dominated by AT&T, and competition in a telegraph industry spinning out of control around multiple suppliers. e New Deal also renovated and modernized the Post O ce.

e centerpiece of its stabilization program was a freshly creative conception of public utility. Rather than continuing merely to anchor legal doctrines for negotiating the terms of trade via state commissions and courts, in the New Deal years the public utility framework was rejuvenated, opened to far-reaching reform initiatives. It became a domain of political ferment; and an un nished vessel, to be lled in ways not yet wholly evident.

At its outset, the FCC gained authority to undertake an unprecedented critical investigation of the nation’s telephone industry. Drawing on a special congressional appropriation, the inquiry combed through AT&T’s corporate records and compiled documentary ndings that proved essential to antitrust prosecutions of the giant company over the succeeding forty years. In the immediate context, nevertheless, AT&T managed to neuter the FCC’s most radical policy prescriptions.

As big business’s credibility had been badly wounded by the Depression, organized labor began to make its own inroads in claiming a public mandate. Chapters 5 and 6 detail how telegraph and telephone workers established industrial unions and how these organizations in turn intervened in telecommunications policymaking—at some points working closely with members and sta at the FCC.

Independent telegraph unions made their voices heard from the start of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and their critique of the industry’s problems di ered sharply from that o ered by telegraph company management. Amid an upswell of radical militancy in the working class, an upstart union of le -wing radio telegraphers renamed itself the American Communications Association (ACA). e ACA emerged just as a great new industrial labor federation—the Congress of Industrial Organizations—was rapidly organizing US heavy industry and pushing forward an o en-radical social unionism. e CIO awarded ACA a charter which conferred upon the small union jurisdiction to organize the entire electrical and electronic telecommunications services industry. (Telecommunications equipment manufacturing was reserved by a far

larger, also Communist-led, CIO a liate, the United Electrical Workers.) e ACA threw itself into industrial and political action. From its base in a failing rival of Western Union—Postal Telegraph—ACA attempted to enlarge its membership at other carriers. Above all, however, it struggled to stave o a merger between Postal and Western Union. Wall Street had aimed for such a combination since the early years of the Depression, and it was expected to result in widespread layo s—especially among the ACA members who worked disproportionately at Postal Telegraph. With its allies in the CIO and the New Deal administration, ACA’s militant social unionism succeeded in forestalling a merger until the middle of World War II.

Again backed by the CIO, ACA organizers also spread out across the far- ung telephone subsidiaries of AT&T. Here they made more limited progress. eir di culties were initially a function of AT&T’s strength as a bastion of “employee representation plans”—company unions—and an unrelenting foe of the CIO’s social unionism. As the war period continued, however, ACA’s lackluster success in AT&T re ected a di erent development: self-organization by telephone workers. Telephone workers were haltingly transforming dozens of AT&T company unions into independent unions and beginning to unite these organizations, separate from either the CIO or the AFL. Composed nearly entirely of white women and men, and fragmented by gender, cra and region, this vast employee group had deemed itself as privileged. However, spurred by lagging pay and the nationwide unionization movement, AT&T employees undertook an uphill climb to establish a genuine industrial organization of their own. A er two strikes—one an epic triumph, the next a near-catastrophic rout—telephone workers united in 1947 within a new international union, the Communications Workers of America. is arduous process re ected not only internal workplace factors but also convulsions in US politics and foreign policy. As World War II ended, business leaders and right-wing politicians mobilized in a bid to arrest the process of domestic New Deal reform, and to contain the reach and power of unions—above all, CIO unions. A great international initiative fed into and strengthened this domestic reversal, as US leaders seized the leadership of global capitalism while, simultaneously, they moved to combat Soviet socialism and to coopt and canalize the revolutionary nationalism that was erupting in the colonial world. e Democratic coalition around Harry Truman (who fell into the presidency at the death of Franklin Roosevelt in April 1945) threw itself into this fraught and complex mission; and the US lurched into a global cold war. Facing intense pressure from within and without, the CIO responded by realigning itself to comport with this cold war policy. is wrenching transition le claw-marks across US society, including on telephone unionism. e CIO stripped the Communistled ACA of its jurisdiction and pushed it aside, in order to bring an initially

fragile and lastingly mainstream CWA into the federation as an a liate union. roughout the 1950s and 1960s, CWA won successive wage and bene ts gains for its increasing membership while becoming one of the nation’s largest industrial unions.

Chapter 7 switches perspective to focus on the sharply changing domain of consumption. e three major services followed distinct paths here. Despite the Western Union-Postal Telegraph merger, telegraph service was still used by only a small fraction of Americans and continued to cater to business users; starting in the late 1950s it became additionally marginalized by a new productsubstitute: computer communications. Despite management rescue schemes, throughout the next decades it became moribund. By contrast, the Post O ce lost none of its general popularity. It did, however, become more commercial. It had acted as a formal channel for the marketing and distribution of commodities since the late nineteenth century, and these functions were massively expanded during the decades a er World War II. Commercial mailings, circulars, and catalogs ooded the mails. Likewise, the telephone network was substantially repurposed to accelerate commodity circulation. Telephone instruments had previously been both beautifully designed and built to last—but on a standard pattern. In the 1960s a widening array of models and styles were introduced, as handsets were turned into objects of consumer desire. Meanwhile, new services, notably outward and inward wide-area telecommunications (800 numbers), breached the defenses of household castles, which again became sites of commercial invasion.

roughout the rst two postwar decades, therefore, the public utility framework itself was modi ed. On one side, completing a process that had originated decades earlier in urban movements for cheap telephone access, a multifarious regulatory program for lowering residential rates at last succeeded, and household telephone service became relatively universal. However, this tremendous achievement was far from an unmixed blessing. It contributed to making endless private commodity consumption, and all that followed from it, a necessity for economic growth. Simultaneously, as Chapter 8 demonstrates, a second mutation also perverted the public utility conception. During the rst postwar decade policymakers used this model to inject an urgent priority to US corporatemilitary technological innovation in and around networking.

roughout prior decades AT&T had built up the world’s preeminent corporate research and development facilities. During the 1930s and 1940s, the patent policies that AT&T a xed to its process of corporate invention drew intense critical scrutiny. Chicago Federation of Labor representative Edward Nockels and a variety of New Deal o cials charged that AT&T’s patents constituted an economic a iction, that the company’s patent monopoly collided with the government e orts to kickstart the economy and reduce mass unemployment. Labor

and government reformers alike demanded forceful intervention. An investigation by the Justice Department commenced during World War II, as responses to my Freedom of Information Act requests reveal. is became a formal antitrust prosecution in 1949, which aimed to break up AT&T so as to lower local telephone rates and thereby to stimulate demand for telephone service. Culminating in the sharply di erent context of the Cold War, however—when regulators were successfully widening household access to telephone service through other means—the agreement reached between AT&T and the Justice Department in 1956 possessed a quite di erent basis. is consent decree le AT&T’s integrated structure intact, while it formally limited AT&T’s commercial services to the regulated telecommunications market as demarcated by the FCC (with the state PUCs). In these ways it rati ed the status quo. However, the decree also compelled AT&T to share its unrivaled trove of patents on easy terms with outside companies, while permitting AT&T itself to operate free of restriction as a military contractor. us it bespoke a militarization of public utility.

At the time, these provisions were generally seen as a slap on the wrist; ultimately, however, they placed AT&T in a vice. Across every industry, from oil to agribusiness, from banking to aerospace, and from chain retailing to auto manufacturing, big businesses were already beginning to integrate innovations in network systems and applications. AT&T, however, was not permitted to supply corporate users with these specialized o erings, which fell outside the realm of regulated telecommunications. Emerging equipment vendors, notably based in the computing industry, sprang up in hopes of catering for this proliferating corporate demand. Might the two be reconciled within the public utility conception? On what terms? Con icts over these questions roiled telecommunications policy throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Chapter 9 examines this moment of transition in light of both rank-and- le insurgencies springing up among postal and the telephone workers and social movement activism churning through American society.

It was a charged era. Both before and a er the election of 1968, notably, there were huge demonstrations against the US war on Vietnam. e incoming Nixon administration, however, also faced a gathering international nancial crisis and initiated a profound re-gearing of geopolitics and US foreign policy. Nevertheless, the status of the US Post O ce was a far from inconsequential item on the presidential agenda. Like his Democratic predecessor, Nixon wanted to transform this longtime government department into a government corporation, with an independent board of governors and a mandate for e ciency— de ned principally in terms of introducing computer technology and catering more fully for corporate bulk mailers.

Most of the politically powerful postal unions rejected such a reorganization, and it remained boxed up in a congressional committee. In March 1970, however,

tens of thousands of miserably paid postal workers, federal employees who were not legally allowed to strike, staged an unauthorized walkout: a wildcat. e strike started in New York City and spread outward from there, across the country and across the di erent postal cra s. While calling out the National Guard to restore mail service—a largely symbolic move—the President began to negotiate behind the scenes, through his trusted aide Charles Colson. Colson importuned James Rademacher, the president of the National Association of Letter Carriers, who had backed Nixon in 1968. Working closely with Rademacher, and o ering pay raises and government recognition of collective bargaining rights for the postal unions—though not a right to strike—the administration induced the wildcatters to return to work and gained the unions’ acquiescence to postal reform. Nixon’s postal reorganization plan thereupon sailed through Congress, with bipartisan support: the United States Postal Service was established. is profound institutional alteration was brokered through compromise with the postal labor force—opposed by many rank-and- le postal workers—whose labor rights were strengthened in the process.

In telephony, meanwhile, the late 1960s and early 1970s again saw a labor upsurge. Groups of militant CWA telephone workers—mainly but not only in heavily unionized New York—demonstrated both antagonism toward their employer and hardening unwillingness to abide by edicts issued by their own union o cials. eir actions portended that business-as-usual within a bureaucratic union, content to operate within the state’s canalized labor relations machinery, could no longer be taken for granted. A national CWA strike in 1971 became an occasion for dissenting rank-and- le telephone workers to exhibit considerable strength and staying power. Some of them displayed a new social unionism, one that opposed CWA’s o cial alignment with US foreign policy as well as AT&T’s racist and sexist employment policies.

Social movement activists—some working within AT&T and others outside it—were concurrently allying with sympathetic lawyers and a maverick member of the FCC to use the telecommunications industry’s legal status as a public utility to try to force an end to employment discrimination. Black, Mexican American, and women workers all contributed. Gay rights activists also demonstrated for employment rights at the telephone company, slightly later. During the Nixon years, their joint endeavors succeeded. e nation’s largest corporate employer was compelled, through a consent decree signed with the Justice Department, to institute a rmative action programs. ese spelled out dramatic change even beyond AT&T. ey established a template for curtailing employment discrimination across the face of corporate America. Revived by workers’ movements to mesh labor and civil rights, and brought home by federal intervention, public utility principles became a springboard to greater social justice and seemed about to open outward on even greater possibilities.

Where might such disruptions to the status quo end? How might they be arrested and, if possible, reversed? Business and political elites persuaded themselves that the political and social problems of the early 1970s lay in too much “entitlement,” too much democracy. e initiatives being undertaken by contemporary rank-and- le workers and activists, many if not most of them women and minorities, did not attest the existence of a unitary movement, indeed, their varied movements betrayed substantial centrifugal force. However disparate, they nevertheless reinforced a conviction among elites that too much power had been amassed—was being exercised—from below. In the view from above, it was the whole messy combination of dissident rank-and- le insurgency, social movement activism, and organized labor’s institutional strength that needed to be contained and countered.

e Nixon Administration engaged this critical problem by redirecting the course of electronic telecommunications through regressive policy interventions. As with postal reorganization, Nixon’s entry point was already established: an Executive Branch proceeding on communication policy conducted by the Democratic administration of Lyndon Johnson during its nal tumultuous year. Chapter 10 unravels the hidden backstory of this proceeding, which was supervised by Undersecretary of State Eugene Rostow, exposing sharp internecine con icts within the undertaking as it progressed. e Rostow Report endorsed the introduction of competition into a limited set of advanced telecommunications services, but expressly retained the public utility framework. e President, however, handed o the unpublished Report to his successor’s transition team, with no recommendation.

During the rst postwar decades, right-wing businessmen had sponsored a recrudescence of free-market economic ideas and policies as an antidote to what they deemed intolerable government regulation. Liberals, by contrast, were becoming persuaded that government had lost an e ective purchase on the regulated industries: that regulators had been coopted by the interests they were supposed to oversee. e result was an increasing convergence in mainstream political opinion. While Democrats endorsed limited competition to restrain a hidebound telephone monopoly, Republicans demanded to pare back regulation on new network industries and markets. It was the Nixon Administration that brought this advancing synthesis to bear upon telecommunications.

Nixon’s men published the Rostow Report, a er determining that it could be used to justify their own much more radical policy program. Nixon’s point-man, a young MIT PhD named Clay T. Whitehead, worked directly with some of the incoming President’s closest advisors, including especially Peter M. Flanigan, an investment banker serving as a top economic aide. Together they set in motion a great lurch in policymaking for advanced networks, initiating an era of digital capitalism.

Nixon plucked Dean Burch, a seasoned Republican political operative, to head the FCC. Henceforward, Burch collaborated closely behind the scenes with Whitehead and other Nixon o cials. eir aims were to open networking to a frontier process of computerization on behalf of big business users, who were demanding access on privileged terms to specialized new equipment and services; and to support new and, though this was never mentioned, antiunion suppliers of such equipment and services.

e early part of what became a protracted transition was conditioned by the hands-o stance adopted by the Communications Workers of America. Rejecting direct political participation in an increasingly bipartisan process of policy liberalization, CWA nevertheless attempted to set up a bulwark against a renewal of corporate power. Early in the 1970s, CWA president Joseph A Beirne initiated merger talks with the two biggest postal unions. CWA’s express goal was to strengthen organized labor by establishing an overarching “American Communications Union”; Beirne glimpsed clearly that CWA needed to prepare itself for contests with capital at a moment when capital was recon guring around new networking technologies. However, this attempt to unite networking labor faltered and, in 1973, it failed—establishing a partial parallel with the 1940s passage to telephone unionism, in which internal fractures and divisions had gured centrally. e top-down movement to policy liberalization thus proceeded without being conditioned by a concomitantly strengthened labor organization. Incremental, and camou aged by a specious rhetoric of competition, liberalization ultimately engulfed US telecommunications. As a growing variety of local and wide area data networks proliferated, and as wireless and satellite systems began to be installed, more and more of the infrastructure big companies used to process and exchange information was stripped out of the casement of public utility. While regulators—Republicans in the Nixon years and Democrats under President Carter—proved complaisant, unions possessed declining leverage—and foreshortened jurisdiction—outside the shrinking sphere of regulated telecommunications. In a trend that rapidly widened through the 1970s and 1980s, corporate employers buttressed their proprietary network operations by embracing union-avoidance strategies. Pivoting sharply at the outset of the Reagan administration (1981), the federal government o ered them sanction. Attempts to reenergize public utility languished decisively in the face of a booming neoliberalism, and its credo that unalloyed corporate decisionmaking freedom should drive network modernization—both domestically and internationally.

In Chapter 11, I return to the formative links which were forged, at the outset, between networking and US empire. roughout the republic’s rst century the Post O ce and, subsequently, the telegraph, were stitched into a process of territorial seizure and occupation. US imperialism proving both durable and

dynamic, telecommunications continued to be vital throughout its subsequent gurations.

US imperialism was always an extracontinental force, however, during the 1890s this quality became systematic with annexations of Hawaii and, by way of the Spanish-American War, of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and other Paci c territories. Hawaii’s strategic location as a cable landing-point was a factor in its takeover. By this time, however, established and emergent capitalist powers had already colonized much of the world, so further opportunities for US territorial occupation were limited. US leaders began to experiment with strategies for securing US investment and pro tmaking outside national boundaries through informal empire. An “American system of international communications” became a cornerstone of this undertaking.

During the interwar period US interests built up several international telecommunications networks, skirmishing with Britain which possessed what was by far the world’s largest territorial empire, backed by its own still-unmatched submarine cable system and unrivaled navy.6 During World War II, o en relying on bases in other countries, the US built out a global network of cables and radio circuits to support the logistics needed to ght the war. With peace, this Allied communications system crumbled.

Global capitalism was then reconstructed. In the face of revolutionary nationalist movements, debilitated colonial powers, and a Soviet Union that not only survived the Nazis but quickly restored its industrial base, the US erected a newmodel empire anchored in its own huge economy. is redesigned system of dominance was built atop multiple pilings. A er World War II the US exercised preponderant power over freshly organized multilateral organizations, including the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the General Agreement on Trade and Tari s, and the United Nations system. US industrial and nancial might faced few signi cant postwar capitalist constraints; and, piggybacking on this strength, US foreign direct investment—previously constrained by preclusive colonial blocs—surged across borders. Hundreds of strategically sited US military outposts, negotiated both with allies and vanquished enemies, now ringed the world. High technology research and development bore the stamp of US military-industrial dominance.

Also constitutive of this informal US empire was an emerging system of USmanaged international communications. Now based on satellite technology, its chief bene ciaries were US multinational corporations and US military command and control structures. An International Telecommunications Satellite (Intelsat) consortium, was set up in the 1960s. It was anchored, crucially, by states, which were represented through the government ministries that operated existing telecommunications services: posts, telegraphs and telephones. e US possessed no such ministry; but it took care to organize Intelsat so that the US

signatory, the private satellite company Comsat, possessed a majority ownership share—and majority voting rights—in the system.

Resented by other signatories, this arrangement was agreeable for the US side. However, ssures deepened as Intelsat moved toward de nitive treaty arrangements. Meanwhile, a fresh wave of antiimperialism grew throughout the countries of what was o en called the ird World; while European and Japanese capitalist rivals posed mounting threats to US economic dominance—notably, in the strategic eld of networking and information technology. Once again it was during the Nixon years that US policy for networks began to be redesigned with an eye to meeting these international challenges.

In keeping with its concurrent e orts to extricate domestic telecommunications from the public utility framework, the Nixon administration rst formulated policies designed to narrow the power of (other) states over international network services, and to augment the role of corporate capital in their stead. is policy program broadened subsequently. During the 1980s and 1990s, the US maneuvered to privatize telecommunications networks worldwide. Dozens of domestic telecommunications operators—previously prized as national ag carriers—were supplanted in any orgy of mostly foreign corporate network investment. At the same time, network functionality was modernized and rearranged to support data transmission between and among computers. As in the United States itself, computer communications was at this stage principally a service for and within corporations and military agencies. It was also disparately con gured. ere were local as well as wide area networks, most built around proprietary and non-interoperable technical standards. US commercial and nonpro t data networks alike were implemented across political jurisdictions; while European and Japanese policymakers sought, somewhat desultorily, to erect protective bulwarks against US networking dominance. is was the context in which, through an opaque and involuted process, one mode of data transport—the one we call the internet—gained over its rivals, shunting state-based competitors into the margins. Its triumph came just a er the collapse of Soviet socialism and the embrace of the capitalist market by China, India and other countries throughout the Global South. e US trumpeted the internet’s ascendancy as a redemption of human rights, and a huge gain for the wretched of the earth. In fact, however, the global internet had been engineered and managed by US-based organizations, and its leading services and applications were dominated by US companies—and well-insulated from (other) states. It was by far the most universal and multifunctional crossborder telecommunications system ever devised: a network t for a full- edged US empire of capital, built around wage labor in what was now a genuinely world market.

Only in 2013 did it become generally known that the global internet was being systematically exploited by interlocking US intelligence agencies and globally commanding US tech companies. A er this, some of the same centrifugal forces that had hit earlier against the Intelsat system again showed themselves with respect to the internet. Economic competitors, above all China, seized internet markets for non-US equipment and service suppliers, while geopolitical rivals— China again in the lead—began to chip away at US organizational dominance.

From the Post O ce of the early republic to the internet of the present day, networks gured throughout US imperialism as the American empire itself was resisted and reorganized. Crossed Wires concludes by sketching how the long and jagged line of political con ict and social struggle likewise continued to mark US telecommunications during the 21st century.