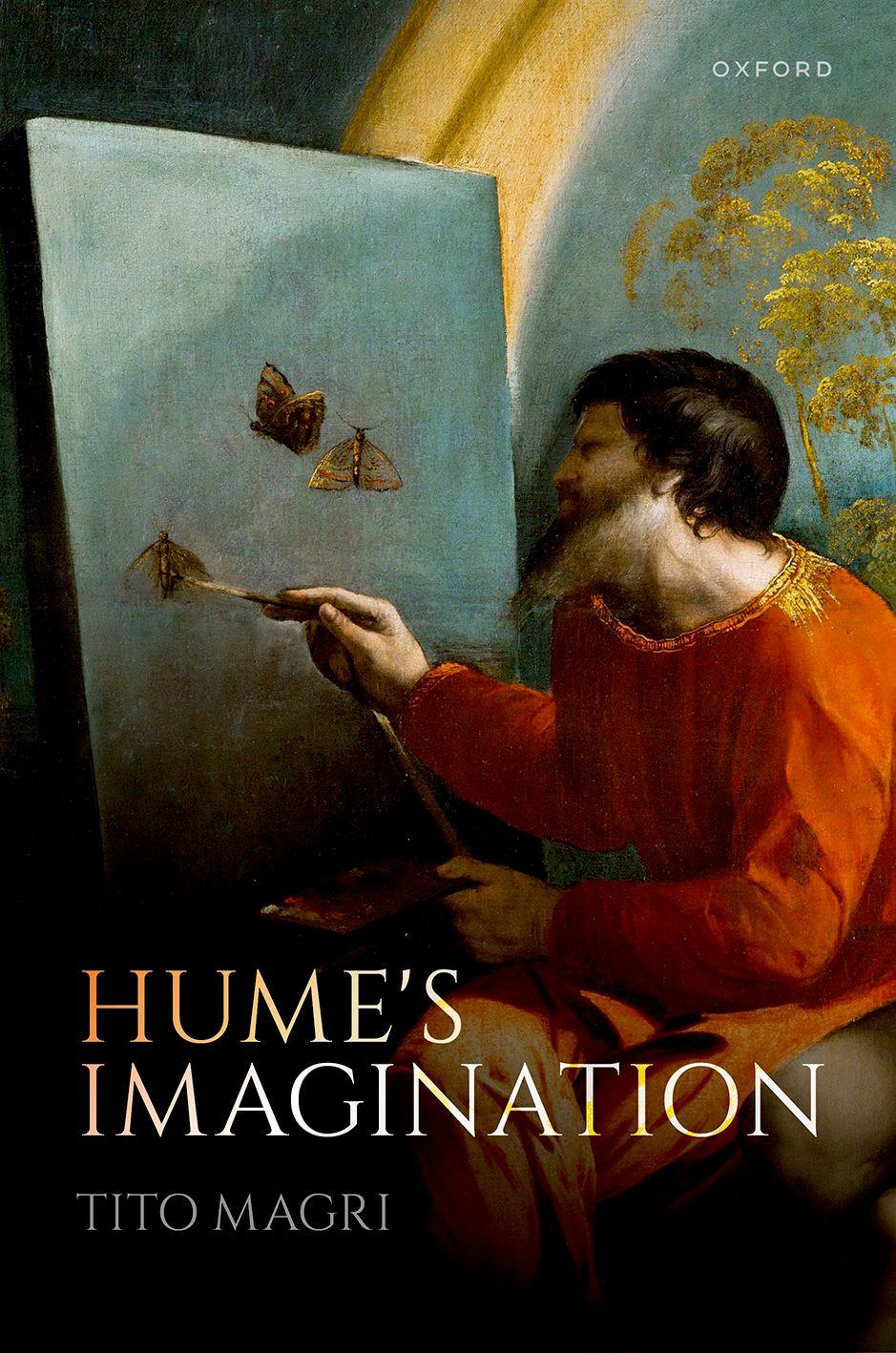

Hume’s Imagination

TITO MAGRI

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Tito Magri 2022

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2022

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022940844

ISBN 978–0–19–286414–7

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192864147.001.0001

Printed and bound in the UK by TJ Books Limited

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

3.

3.1.2

3.2

3.2.1

3.2.2

3.2.3

3.3

3.3.1

4.

3.5

3.4.3

PART II. THE INTELLECTUAL WORLD OF IDEAS

4.1.1

4.2

4.1.4

4.2.1

4.2.2

5.

5.1

5.1.1

5.1.2

5.1.3

5.2

5.2.1

6.

5.3

5.2.2

5.2.3

5.3.1

5.3.2

5.3.3 Explaining A

5.4

PART III. A NEW SYSTEM OF REALITIES

6.1 The Cognitive Gap of Causation

6.1.1 Causal Reasoning and Causal Content: Inferring the Unobserved

6.1.5

6.2 The Nature of that Inference

6.2.1

6.2.2

6.2.3

7.

6.3

7.1

7.2.1

7.2.2 From Necessary Connexion to the Imagination

7.2.2.1

7.2.2.2

7.2.2.3 Causal Necessity and the Imagination

7.2.3 Transitions and Conceptions: Spreading in the Mind, Spreading on the Objects

7.2.3.1 Conceiving Connexions

7.2.3.2 Spreading in the Mind

7.2.3.3 Spreading on External Objects

7.3 Hume’s Philosophy of Causation

7.3.1 The Two Definitions: Structure, Rationale, and Implications

7.3.1.1 The Complexity of Causal Content

7.3.1.2 Inferentialism and the Two Definitions

7.3.1.3 The Ontology of Causation

7.3.2 True Meaning and Wrong Application

7.4 Summary

8. The Ideas which are Most Essential to Geometry

8.1 Representing Space and Time

8.1.1 Manners of Disposition of Visible and Tangible Objects

8.1.2 Finite Divisibility and Adequate Representation

8.2 Imagining Space and Time

8.2.1 An Abstract Idea of Time and Space

8.2.2 The Definitions and Demonstrations of Geometry

8.2.2.1 The Cognitive Gap of Geometrical Equality

8.2.2.3 The Illusion of

8.2.3 A Vacuum or Pure Extension

8.2.3.1 The Missing Idea of a Vacuum

8.2.3.2 We Falsely Imagine We Can Form such an Idea

8.2.3.3 A Vacuum is Asserted

8.3 Summary

9. The World as Something Real and Durable

9.1 The Missing Idea of Body

9.1.1 The Principle Concerning the Existence of Body

9.1.2 The Cognitive Gap of External Existence

9.1.2.1 The Senses

9.1.2.2 Reason

9.2

9.1.3

9.2.1 ‘Spreading out in my mind the whole sea and continent’

9.2.3 ‘A

Hysteresis

9.3.3.1

9.3.3.2

9.4.1

10.

10.1.1

PART V. THE IMAGINATION OR UNDERSTANDING, CALL IT WHICH YOU PLEASE

Preface and Acknowledgements

In this book, I aim to propose a new and unitary interpretation of the nature, structure, functions, and systematic importance of the imagination in Book 1: Of the understanding, of Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature. The interpretation I propose has deeply revisionary implications for Hume’s philosophy of mind, as well as for his naturalism, epistemology, and stance to scepticism. My principal claim is that we can best, and perhaps only understand Hume’s imagination as a mental natural kind if we consider it as the source of a distinctive and necessary sort of mental contents; as the source of new original ideas, like those of cause, body, or self. A basic insight of Hume’s philosophy in Book 1 of the Treatise is that we can be in cognitive contact with objects, their properties, and their relations only sensibly; that we can only represent sensible objects. Impressions of sensation or objects of sense are all we can be acquainted with. Hume complements this radically empiricist commitment with another insight (one which drew Kant’s attention): the ideas and cognitions issuing from object representation fail to explain and to support most of our best-established, ordinary and philosophical cognitive practices.

This combination of claims brings Hume’s philosophy to the verge of paradox. The restriction of object representation to sensibility (impressions of sensation, objects of sense) is both an expression and a condition of the program of naturalization of mind and cognition pursued in the Treatise. This means that the limits Hume detects in object representation are natural to it, are an aspect of our cognitive nature. Therefore, our ordinary and philosophical practices, including the kind of reflection that underlies the experimental method of reasoning and Hume’s naturalism, seem to involve a cognitive impossibility. This sort of paradox could and did motivate either resorting to some special sort of object representation, by intellectual ideas (this is how Hume conceives of rationalist philosophies), or giving up any claim to complex, distinctively human cognition (scepticism). For Hume, this would be the unpalatable choice between a false reason (rationalism) and no reason at all (scepticism). Hume’s way out of this dilemma is not to drop naturalism, or to embrace scepticism. It is to drop the identification of content and cognition with object representation. We can preserve naturalism (object representation is only sensible) without threat of scepticism (conceptual thought and reasoning are possible) by complementing sensible representation with a different, equally natural, but non-representational kind of cognitive content. Contents that are missing from sensible representation and seem to be impossible or spurious can and do perform their cognitive roles

without having to represent objects at all. This is the place and function of the imagination in human nature. Hume’s imagination is our natural faculty of inference and the source of a distinctive kind of ideas, which allow us to overstep the limits of our sensible representation of objects consistently with naturalism. (A reading along similar lines could perhaps be given of the place and function of sentiments in Hume’s morals.)

The book reconstructs how Hume’s naturalist and inferentialist theory of the imagination develops this fundamental insight. Its five parts deal with the dualism of representation and inference; the inferential character and the cognitive structure of the imagination; the explanation of generality and modality; the production of causal ideas; the production of spatial and temporal ideas and of the distinction of an external world of bodies and an internal one of selves; and the replacement of the understanding with imagination in the analysis of cognition and in epistemology. In this way, I aim to remedy to a sort of blind spot in Hume scholarship, because precisely the complexity and the apparent lack of unity of Hume’s imagination seem to be responsible for a relative lack of interpretive attention to this topic. One somewhat surprising conclusion I come to draw is that, at the core of Hume’s philosophy, we find a partial but significant form of inferentialism about mental content. Rather than as a card-carrying representationalist, as he is often considered, we should look at Hume as an early, but important and committed inferentialist. This, at least, if the role of imagination in his philosophy is well understood. In this connection, the study of Hume’s theory of the imagination can also contribute to the current, lively philosophical debate on imagination. Hume’s philosophy can give suggestions about how to treat imagination as a mental natural kind, despite its cognitive complexity and the variety of its roles.

Work on this book has taken quite a stretch of my life. All along these years, I have presented my views about Hume’s imagination and related topics at International Hume Conferences in Canberra, Rome, Las Vegas, and Budapest; at Hume conferences in Rome, Assos, Belo Horizonte, and at the Oxford Hume Forum (online); at the Modern Philosophy Conference at New York University and at the NY/NJ Modern Philosophy Seminar; and at talks at the University of Pittsburgh; University of Florida (Gainsville); University of Reading; Union College (Schenectady); University of Wisconsin (Milwaukee); and at the University of Toronto. All along these years, I profited from helpful discussions with many people about Hume’s philosophy, naturalism and normativity, and mental representation. I here remember D. Ainslie, A. Baier, H. Beebee, A. Bilgrami, J. Biro, S. Blackburn, M. Boehm, R. Brandom, E. Chavez-Arizo, R. Cohon, J. Cottrell, S. Darwall, P. Donatelli, M. Frasca-Spada, C. Fricke, D. Gauthier, A. Gibbard, L. Greco, P. Kail, E. Lecaldano, L. Loeb, B. Longuenesse, S. Marchetti, E. Mazza, J. McDowell, J. McIntyre, P. Millican, D. Norton, O. Oymen, S. Pollo, H. Price, E. Radcliffe, P. Railton, J. Richardson, C. Rovane, A. Schmitter, D. Tamas, J. Taylor,

A. Vaccari, A. Varzi, and two Readers for OUP. Peter Momtchiloff, from OUP, has taken special care of my project. My philosopher friends, Julia Annas and David Owen, have had an important part in this effort. David was perhaps the first philosopher with whom I discussed seriously about Hume’s views on knowledge and reason. Together with Julia, they have so many times provided a wonderful environment for my study and writing. Finally, I have the greatest debt with Don Garrett, whose friendly criticism, suggestions, and encouragement have been a constant and indispensable support for my work.

Introduction: A Magical Faculty

[A] kind of magical faculty in the soul, which, tho’ it be always most perfect in the greatest geniuses, and is properly what we call a genius, is however inexplicable by the utmost efforts of human understanding. (1.1.7.15)

1.1 An Interpretive Blind Spot and a Philosophical Problem

No text of modern philosophy comes close to Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature, especially its Book 1: Of the understanding, in the variety, complexity, and systematic importance of the roles it gives to the imagination. Because of our cognitive nature, we can have ideas with general and modal contents only if they are conceived, transposed, and changed by the imagination. All sorts of reasoning, both a priori and a posteriori, compare ideas conceived by the imagination and depend on its primitive transitions. In this way, what might appear as the ‘whole intellectual world of ideas’, open to our understanding and intellectual agency, is nothing but the result of how ‘the imagination suggests its ideas, and presents them at the very instant, in which they become necessary or useful’ (1.1.7.15). It is the imagination that puts in place the ‘foundation of mathematics’ (1.4.2.2). It ‘peoples the world’, making us ‘acquainted with such existences, as by their removal in time and place, lie beyond the reach of the senses and memory’ (1.3.9.4). This makes it possible for us to have a view of the world as a connected system of continuedly and independently existing objects; it forms all the ‘ties of our thoughts’ and is ‘to us cement of the universe’ (Abstract 35). The transitions of the imagination are the source of our worldview. ‘I paint the universe in my imagination, and fix my attention on any part of it I please’ (1.3.9.4). Even the distinction between the external world of bodies and the internal world of our self or mind comes from the imagination (1.4.7.3). This is the sense in which Hume talks of the ‘empire of the imagination’, of its ‘great authority over our ideas’ (Abstract 35), claiming that on its principles ‘all the operations of the mind must, in a great measure, depend’ (Abstract 35). It is no surprise, then, that by the simplest word counting and apart from the ubiquitous ‘impression’ and ‘idea’, ‘imagination’ and related words are

the theoretically laden lexical area with most occurrences in Book 1 of the Treatise.1

It is thus only fair to say that the imagination, in Book 1 of the Treatise, jumps to the eye. But if we consider Hume scholarship, we find a very different situation. The role, importance, and nature of the imagination in Hume’s philosophy has long been an interpretive blind spot. Two classic studies, Kemp Smith’s The Philosophy of David Hume (1941) and Barry Stroud’s Hume (1977), fail to give proportionate space and attention to the imagination. Kemp Smith’s wellknown individuation, in the philosophy of Hume’s Treatise, of Hutchesonian and Newtonian strands, the first biological in character, with an insistence on instincts, passions, emotions, and sentiments, the second mechanistic, with perceptions treated as simples and association as the sole mechanism, confines the imagination to the latter one.2 Insofar as the imagination plays any role in Kemp Smith’s interpretation, it is almost exclusively a negative one: the hinge on which Hume’s failed explanatory programme in terms of association of ideas turns.3 Kemp Smith contrasts the imagination with the important category of natural beliefs, which he regards as one of Hume’s achievements. He recognizes that natural (irresistible, causally determined, justificationindependent) beliefs have their grounds in the imagination; but he holds that the phenomenon of natural belief is more important and less hypothetical than such explanation.4 Hume’s allthingsconsidered position should have been what he ended up with in the first Enquiry: dropping the search for associative mechanisms underlying, say, the natural belief in the external world; and treating such belief ‘as being, like the moral sentiments, in itself an ultimate’.5 The importance of the imagination in Hume’s philosophy is no greater than that of a ‘corollary to his early theory of belief’.6

With Stroud we take a huge step forward. Stroud has a much more balanced understanding of the role of the imagination in Hume’s philosophy. Still, rather than discussing it thematically, on a par with the theory of ideas and with passions and moral sentiments, Stroud only addresses imagination in passing. In his conclusive, important reflections on Hume’s naturalism, Stroud concentrates his criticisms on the explanatory shortcomings of the imagination. The ‘act of

1 ‘Imagination’ and related words like ‘fancy’, ‘imagine’, ‘imagining’, ‘imaginary’, ‘fiction’, ‘feign’, ‘feigning’, and ‘fictitious’ sum up to 374 occurrences in Book 1. To get a sense of how much this is, consider that ‘belief’ and related verbal forms have 203 occurrences; ‘sensation’, ‘sensations’, and ‘senses’, 216; ‘reason’, as name and as a verb, 211; and ‘feeling’, 46. Only if we consider ‘impression’/‘impressions’ (respectively, 224 and 191 occurrences) and, of course, ‘idea’/‘ideas’ (respectively, 655 and 439) do we find philosophically important words with more occurrences.

2 N. Kemp Smith, The Philosophy of David Hume (1941), Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2005, 550.

3 Kemp Smith, Philosophy of Hume, 533, 535.

4 Kemp Smith, Philosophy of Hume, 409, 449, 493.

5 Kemp Smith, Philosophy of Hume, 535.

6 Kemp Smith, Philosophy of Hume, 462–3.

feigning the continued existence of bodies’ fails to add anything significant to the coherence and constancy of our experience and thus ‘does not seem to make any difference to any of our thoughts’.7 In the same vein, Stroud denies that Hume has any ‘satisfactory account’ of the complex modal implications of causal inference and causal cognition.8 His assessment culminates in reproaching Hume, because of his ‘theory of ideas’, for failing to understand that having an idea is ‘a matter of having a certain ability, capacity or competence’.9 Which is precisely what I would say is the distinctive cognitive contribution of Hume’s imagination. There is some similarity between Stroud’s and Kemp Smith’s overall assessments of Hume’s imagination. Both point to deep confusions, even inconsistencies, in Hume’s conception of it. Stroud in particular individuates a ‘curious tension’ between Hume’s view of the imagination ‘as the home of the “sensitive” or “passionate” rather than the “cogitative”, part of our nature’ and the ‘very strong “intellectual” or “cognitive” flavour’ (particularly in the account of the idea of body) he imparts to it.10 One is then left wondering what sense to make of Hume’s obstinate, almost perverse concern with the imagination.

Much has changed in Hume scholarship since 1941, even since 1977, also in connection with Hume’s theory of the imagination. In a classical work from 1983, J. P. Wright, in antithesis to Kemp Smith and Stroud, points out that association and imagination, rather than feeling or the passions, should be given pride of place in interpreting Hume.11 And recent and very recent scholarship has done and is doing important work to bring into view the pervasive and important explanatory roles of Hume’s imagination, as well as the philosophical problems they raise. To mention only a few names, I have in mind the work of scholars like Garrett, Owen, Loeb, Rocknak, Cottrell, Ainslie, and Costelloe.12 However, I think that there is much interpretive and philosophical work still to be done in this area. Because, as Kemp Smith and Stroud witness, careful and intelligent readers may conclude that Hume’s imagination is beset with confusions, tensions, even inconsistencies. That in Hume’s philosophy the imagination is like a

7 B. Stroud, Hume, Routledge, London 1977, 235. 8 Stroud, Hume, 235.

9 Stroud, Hume, 232. 10 Stroud, Hume, 108.

11 J. P. Wright, The Sceptical Realism of David Hume, Minnesota University Press, Minneapolis 1983, 209–10.

12 D. Garrett, Cognition and Commitment in Hume’s Philosophy, Oxford University Press, New York 1997; D. Garrett, Hume, Routledge, Oxford/New York 2015; D. Owen, Hume’s Reason, Oxford University Press, New York 1999; L. Loeb, Stability and Justification in Hume’s Treatise, Oxford University Press, New York 2002; S. Rocknak, Imagined Causes: Hume’s Conception of Objects, Springer, Dordrecht/New York 2013; J. Cottrell, ‘Hume: Imagination’, in Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy http://www.iep.utm.edu/humeima/; J. Cottrell, ‘A Puzzle about Fictions in Hume’s Treatise’, forthcoming; D. Ainslie, Hume’s True Skepticism, Oxford University Press, New York 2015; T. M. Costelloe, The Imagination in Hume’s Philosophy, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2018. Before this recent surge, the one monograph dedicated to Hume’s imagination was J. Wilbanks, Hume’s Theory of the Imagination, Nijoff, The Hague 1968.

wastepaper basket, where all sorts of otherwise unaccounted for phenomena find some accommodation. A magical faculty in the worst sense of practical magic, without true systematic role and conceptual unity.

I think that this interpretive problem is still in many ways open. Interestingly, concern about the unity and the functions of the imagination has emerged also in contemporary philosophical discussion. The last two decades have witnessed a resurgence or, more exactly, a surge of philosophical interest in the imagination. This, however, has been accompanied with reservations about whether there is any significant common factor, any sort of unity of kind underlying the different applications of the concept (or name?) of the imagination. So, for instance, in the entry on imagination for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, we find the remark that ‘There is a general consensus among those who work on the topic that the term “imagination” is used too broadly to permit simple taxonomy.’ Peter Strawson is also quoted to this effect.

The uses, and applications, of the terms ‘image’, ‘imagine’, ‘imagination’, and so forth make up a very diverse and scattered family. Even this image of a family seems too definite. It would be a matter of more than difficulty to identify and list the family’s members, let alone their relations of parenthood and cousinhood.13

This diversity or even confusion of uses seems to unveil an irreducible and hardly manageable multiplicity in the concept of imagination. In a recent article, Amy Kind has argued that it is not an accidental matter, or an expression of the different aims philosophers and cognitive scientists have in their research, that the imagination proves to be so recalcitrant to a unitary treatment. The heterogeneity of the imagination, as she points out, is determined by deep, possibly unavoidable tensions among its explanatory roles (engagement with fiction, pretence, mindreading, and modal cognition) and the demands they make on its features (for instance, whether supposing is a variety of imagining; whether and how imagining has motivational import).14 This is the philosophical problem with the imagination: whether, to what extent, and in what sense it has theoretical unity and marks a cognitive and perhaps an epistemic kind. Reflection on Hume’s theory of imagination may perhaps allow us to make progress with this problem.

13 See http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/imagination/ (authored by Shenyi Liao and Tamar Gendler). Strawson’s quotation is from P. Strawson, ‘Imagination and Perception’, in Experience and Theory, L. Foster and J. W. Swanson (eds.), University of Massachusetts Press (Amherst) (31–54), 31.

14 A. Kind, ‘The Heterogeneity of Imagination’, in Erkenntniss, 2013, 78 (14–159).

1.2 The Imagination in Hume’s Treatise

There are thus pressing interpretive and philosophical reasons for addressing in a systematic way Hume’s imagination. In fact, the theory of the imagination is in many respects the key to understanding Hume’s philosophy in the Treatise.

1.2.1 The Works of the Imagination

At all the important steps of the analyses and arguments of Book 1, Hume refers to ideas and capacities which are deployed in our cognitive practices but cannot be explained with sense experience or a priori, but only with the imagination. To get a sense of the cognitive work of Hume’s imagination, it may be convenient to have them present at a glance.

Perfect Ideas: Imagination can detach all ideas from the context of their first occurrence in sense experience; because of this capacity, it can separate all its ideas (1.1.3.1)

Association: The imagination combines the perfect ideas it has separated, forming whatever complex contents it pleases. It proceeds according to ‘universal principles’, so as to put in place the ideas that are the ‘common subjects of our thoughts and reasoning’ (1.1.4.1)

Generality: Imagination explains how general words get their meanings and how particular ideas are applied ‘beyond their nature’, allowing us to reason to general conclusions. This also explains ‘distinctions of reason’, aspectual thoughts, as well as the intentionality of thinking (1.1.7.7)

Modality: Imagination allows thinking of the same objects as existing in different situations and with different properties from the ones actually given in experience. This is also the root of a priori, demonstrative reasoning (1.2.4.11)

Space and Time: The ideas of space and time as general frames or structures of our experience, possibly existing without being occupied by things or events, are owing to the imagination (1.2.5.29)

Geometric Equality: The imagination explains the idea of a standard of equality of size on which we rely in geometry. Imagination in general produces the ‘ideas which are most essential to geometry’ (1.2.4.24)

Inference to Unobserved Objects: Only the imagination explains how from the present experience of an object we can conclude to the past or future existence of another one (1.3.2.2)

Uniformity of Nature: The ‘principle’ that ‘the course of nature continues always uniformly the same’ is owing to imagination, not to sense, memory, or reason (1.3.6.11)

Belief: The imagination, in particular its power to enliven ideas, puts in place the contents and the attitudes that constitute cognition of matters of fact neither perceived nor remembered, but only inferred (1.3.8.7)

Causation: The idea of cause issues from a complex response of the imagination to repeated patterns of observed objects. This also explains the belief in the necessity of a cause for any beginning of existence (1.3.7.14–15)

Doxastic Deliberation: We can get to causal conclusions by reflective causal reasoning, by comparing causal ideas, and by applying rules of causal judgment, because of the contents made available by the imagination and in the cognitive context it defines (1.3.8.14)

Degrees of Probability: With the ‘fancy’, by conveying and distributing assent to different ideas, we come to the idea of the likelihood of events and of its degrees (1.3.12.22)

Causal Necessity: The ‘new original idea’ of causal necessity derives from the multiplicity of observed successions, only by way of their effects on the imagination and on its transitions (1.3.14.20)

Powers: The natural ‘biass’ to assume that causation consists in powers located in bodies depends on imagination’s spreading internal impressions on external objects (1.3.14.25)

General Rules: The general rules by which we ought to judge of causes and effects are formed by the imagination (1.3.15.11)

Belief-Revision: We can effectively reflect on and correct beliefs based on reasoning, without any threat of regress, because of the embedding of this practice in the imagination (1.4.1.10)

External Existence: Our natural, unshakeable belief of a real and durable world is produced neither by the senses nor by reason, but by the imagination (1.4.2.14)

Identity: The principle of the individuation and identity of objects is possible because the imagination, in relation to the idea of time, can occupy different viewpoints on objects taken as unchanging (1.4.2.29)

Epistemic Evaluation: Functional and causal differences between principles of the imagination fix the reference of our distinctions between regular and irregular patterns of reasoning, all equally grounded in the imagination; imagination is the ‘ultimate judge of all systems of philosophy’ (1.4.4.1)

Self: We have no impression and idea of the self as what our several perceptions inhere to; but we have a natural propensity to imagine our internal simplicity and identity (1.4.6.16)

In a nutshell, the explanation of conceptual thinking, of a priori and a posteriori reasoning, of the structures of the external and internal world, the method of

moral and natural philosophy, the objects and criteria of epistemic evaluation all ultimately depend on the properties and activities of the imagination.

1.2.2 Hume’s Problem: Cognitive Gaps

The list of the works of imagination is certainly impressive. But it may look like a mixed bag. It spans across modes of thinking (contextindependence, generality, modality), cognitive capacities (reasoning, doxastic deliberation and beliefrevision, epistemic evaluation), cognitive structures (space and time, uniformity of nature, causal connections, powers, external existence, identity, self), and mental states (belief). However, I think that Hume’s imagination harbours an important, unifying theoretical pattern, which hinges on a complex view of our acquaintance with objects, of its limits, and of the nature of mental activity.

As it emerges from the list, the imagination makes its entrance and operates where sense experience and the understanding or reason cannot explain ideas and cognitive capacities deployed in our ordinary and philosophical cognitive practices.15 Furthermore, and most importantly, in all the cases I have listed, no matter how different the ones from the others, it is not by accident but a matter of natural necessity if sense experience or the understanding fail to provide us with such ideas and capacities. The contents of the relevant ideas and the corresponding capacities cannot be reduced to objects and properties; therefore they cannot in principle be explained with sense experience or intellectual insight. These cognitive gaps are unavoidable and irreparable; they are marks of human cognitive nature.

Hume’s response to the limits of our natural representation or apprehension of objects is neither to explain away the relevant ideas nor to resort to some nonnaturalistic cognitive faculty. There is no hint, in Hume, of any devaluation of the sensible sources of content; no hint of the rationalist thesis that objects are given in sensation only in a confused and indistinct manner. The input of sense experience forms a primitive, irreducible, and perfectly sound layer of the natural mind. Hume, rather, accurately individuates the ways in which ideas and cognitions issuing from sense experience or available a priori fail to match our cognitive practices and our worldview. Against this background, he advances alternative explanations of the missing elements by resorting to a complex of mental operations which he (quite appropriately, I would say) refers back to the faculty of imagination. The primary role of Hume’s imagination is to fill the cognitive gaps left open by ideas representing sensible objects or by the understanding with the naturalistic, empirically explainable production of new ideas and of cognitive changes. In Hume’s philosophy, the imagination has a unitary, positive, and constructive

15 On the gapfilling function of Hume’s imagination see Wilbanks, Hume’s Theory of the Imagination, 154–5.

theoretical role: integrating our sensible representations of objects and our understanding with contents of new kinds and, in this way, explaining and vindicating (many of) our ordinary and philosophical cognitive practices. In this connection, I think that Kant’s interpretation of the fundamental inspiration of Hume’s philosophy (whose misunderstanding by the common sense school he bitterly complains about in the Prolegomena) is deep and insightful.

Among philosophers, David Hume came nearest to envisaging this problem [‘How are a priori synthetic judgments possible?’], but still was very far from conceiving it with sufficient definiteness and universality. He occupied himself exclusively with the synthetic proposition regarding the connection of an effect with its cause (principium causalitatis), and he believed himself to have shown that such an a priori proposition is entirely impossible. If we accept his conclusion, then all that we call metaphysics is a mere delusion whereby we fancy ourselves to have rational insight into what, in actual fact, is borrowed solely from experience, and under the influence of custom has taken the illusory semblance of necessity.16

Hume came nearest to recognizing the problem of the synthetic a priori, because he realized, at least with reference to causality, that the necessity of the causal nexus excluded that causal thought and cognition had their sources either in sensibility or in simple concepts.17 Kant thus agrees with Hume that there is a necessary cognitive gap corresponding to causal content and cognition and that this raises a special problem of constitutive explanation (a howpossible? problem). And he correctly identifies the imagination as Hume’s response to this newly discovered, systematic problem, even though he rejects such response as mistaking ‘subjective necessity (i.e., habit) for an objective necessity (from insight)’.18

Since [Hume] could not explain how it can be possible that the understanding must think concepts, which are not in themselves connected in the understanding, as being necessarily connected in the object [. .], he was constrained to derive them from experience, namely, from a subjective necessity (that is, from custom), which arises from repeated association in experience.19

16 I. Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, Palgrave, London 2003, 55 (in ‘Introduction’, 6: ‘The general problem of pure reason’). See also 127 (in ‘Transcendental Deduction’, 14: ‘Transition to the transcendental deduction of the categories’). See, for a careful and informative account of Kant’s reading and interpretation of Hume’s philosophy, A. Anderson, Kant, Hume, and the Interruption of Dogmatic Slumber, Oxford University Press, New York 2020, 8–9, 87–89, 145–60.

17 See I. Kant, Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004, 7 (in ‘Preface’): ‘He indisputably proved that it is wholly impossible for reason to think such a connection a priori and from concepts, because this connection contains necessity; and it is simply not to be seen how it could be, that because something is, something else necessarily must also be.’

18 Kant, Prolegomena, 7. 19 Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, 127.

1.2.3 Imagination and Inference

Hume makes very strong claims about the role of the imagination in the production of ideas and in cognitive change. It is thus important to take a first look at what allows Hume’s imagination to perform such a role. The first, crucial point is that he indissolubly connects the function of filling the gaps of object representation with the inferential character of the activity of the imagination. Representation of objects is confined, for human nature, to sense experience and to its storage in memory. (Hume dismisses the rationalist view of reason as a priori objectrepresenting faculty.) The imagination can overcome the necessary, natural limits of object representation precisely because, as a cognitive faculty of human nature, it is inferential and not object representing. Because of this, it is not under the constraints of our natural representation of objects.20 It can widen and change the scope and the patterns of our thinking and cognition because it consists in transitions of ideas and not in acquaintance with objects.

The second point (which I can only mention here) is the complex internal structure of Hume’s imagination. It operates inferentially in the guise of implicit or explicit, immediate or reflective comparisons of available ideas, based on their contents and relations. In this guise, the imagination realizes our general capacities for reasoning. But its inferential character also consists in immediate mental transitions, which change ideas by their concurrence with its own primitive dispositions and put in place contents that would otherwise be missing and that we compare in reasoning. The dual character of Hume’s imagination and its unity as a faculty will be examined in due course, when we come to discuss what I call the Structural Principle. What is important, right now, is that the production of new kinds of ideas and cognitive capacities is realized by the imagination in the different ways or levels at which it engages in transitions among ideas, based on empirically ascertainable, nonrepresentational inferential principles. It is in connection with these transitions, or considered dynamically, that the principles of association and association itself are cognitively important and make for a radical change in what ideas and cognitions are available to our minds.

The foundation of Hume’s philosophy in Book 1 of the Treatise is thus the natural distinction of kind between objectrepresenting contents, ideas, and faculties (sense and memory) and inferential ones (imagination). And the distinction, within this latter, between inferences grounded on the contents and relations of ideas, with the character of reasoning, and mental transitions caused by the interaction of ideas with its nonrepresentational principles. Nothing short of this conceptual pattern seems up to explaining how natural cognitive gaps can be

20 For an interpretation of Hume’s views on mental content very close to the one I am proposing, see K. Schafer, ‘Hume’s Unified Theory of Mental Representation’, European Journal of Philosophy, 23, 4, 2015 (978–1005).

filled in a naturalistic way. Such gaps are inherent to our natural capacity of object representation. If the mind could not tap some other, radically different but equally natural source of content, there would be no remedy to such incompleteness.

It is also enormously interesting that Hume’s imagination, in this way, comes in many respects close to our views of it. Four central features that contemporary philosophy and cognitive science identify as distinctive of imagination—its essential imagistic character, its proceeding in a broadly inferential way, its making available information about the world without explicitly representing it, its enacting or simulating mental states and properties—have clear counterparts in Hume. It is also widely recognized that, in these ways, imagination contributes in important and irreducible respects to our cognitive outreach and to its improvement. I will introduce and discuss these matters as we go on. But we can say that its overall function and its close connections with contemporary views retrospectively sanction Hume’s identification of the imagination as ‘a kind of magical faculty in the soul’ (1.1.7.15).

1.3 Imagination, Naturalism, and Scepticism

Because of its central importance for Hume’s philosophy overall, the theory of the imagination provides essential conceptual keys for its interpretation. I want to outline briefly how the theory of imagination is systematically significant for Hume’s naturalism, his epistemological ambitions, and his stance on scepticism.

1.3.1 Imagination and the Science of Human Nature

The philosophical programme of the Treatise is well expressed by its full title: A Treatise of Human Nature: Being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects. The ‘science of MAN’ (Introduction 4), the ‘science of human nature’ (Introduction 9), the empirical study of human nature, is the execution of this ‘attempt’. We can gain a comprehensive and deep understanding of all that is relevant for philosophy only from the standpoint of human nature. ‘’Tis evident, that all the sciences have a relation, greater or less, to human nature; and that however wide any of them may seem to run from it, they still return back by one passage or another’ (Introduction 4). This is because our nature includes the cognitive resources which can account for our success in all the sciences, even those with little or no relation to it (‘Mathematics, Natural Philosophy, and Natural Religion’, Introduction 4). Of course, the sciences that have human nature as their object (‘Logic, Morals, Criticism, and Politics’, Introduction 5) are

also only appropriately understood from the perspective it affords. Constructing and vindicating this sort of naturalism is thus the general aim of the Treatise: ‘Human Nature is the only science of man; and yet has been hitherto the most neglected’ (1.4.7.14).

The science of human nature is, of course, empirical. ‘As the science of man is the only solid foundation for the other sciences, so the only solid foundation we can give to this science itself must be laid on experience and observation’ (Introduction 7). In fact, experimental moral philosophy, the ‘application of experimental philosophy to moral subjects’ by ‘some late philosophers in England’: ‘Mr. Locke, my Lord Shaftsbury, Dr. Mandeville, Mr. Hutchinson, Dr. Butler, &c.’, as Hume recalls in a footnote (Introduction 7 fn. 1), has followed the steps and taken up the method of experimental natural philosophy. Deferring to this tradition, Hume makes his case for a ‘reformation’ of moral philosophy in the spirit of natural philosophy.

For to me it seems evident, that the essence of the mind being equally unknown to us with that of external bodies, it must be equally impossible to form any notion of its powers and qualities otherwise than from careful and exact experiments, and the observation of those particular effects, which result from its different circumstances and situations (Introduction 8).21

Against this background, the importance of the imagination for Hume’s naturalism is perfectly clear. ‘Logic’ is the subject matter of Book 1 of the Treatise, the explanation of ‘the principles and operations of our reasoning faculty, and the nature of our ideas’ (Introduction 5); or, as Hume summarizes it conclusively, the full explanation of the ‘nature of our judgment and understanding’ (1.4.6.23). Hume’s imagination is central to this explanation and crucially contributes to its naturalist and empiricist character. Restricting our attention to Book 1, the most serious threat to Hume’s naturalism is the option, chosen in the Cartesian, rationalist tradition, to infer from the limits of our sensible cognition of objects the need for a different, nonsensible kind of objectrepresenting ideas. Hume makes this point with initial reference to the ideas of mathematics, but then extends it to philosophy in general.

21 Hume’s experimental approach to the mind is one we are nowadays familiar with, both in philosophy and in cognitive science. Hume would subscribe to the following programmatic statement, which refers, significantly, to the imagination: ‘Our suggestion is that philosophers interested in the imagination shift their methodology from the traditional paradoxandanalysis model to a more empiricallyoriented phenomenaandexplanation model’, J. Weinberg & A. Meskin, ‘Puzzling Over the Imagination: Philosophical Problems, Architectural Solutions’, in S. Nichols, ed., The Architecture of the Imagination, Clarendon Press, Oxford 2006 (175–202), 177.

’Tis usual with mathematicians, to pretend, that those ideas, which are their objects, are of so refin’d and spiritual a nature, that they fall not under the conception of the fancy, but must be comprehended by a pure and intellectual view, of which the superior faculties of the soul are alone capable. The same notion runs thro’ most parts of philosophy, and is principally made use of to explain our abstract ideas, and to shew how we can form an idea of a triangle, for instance, which shall neither be an isosceles nor scalenum, nor be confin’d to any particular length and proportion of sides. (1.3.1.7)

This important, programmatic text deserves our attention. The core of the contrast between Hume and the Cartesian tradition is not metaphysical or epistemological; rather, it is a contrast between the nature of ideas and of mental activity. Hume agrees with the rationalists (and with Kant) that our sensible acquaintance with objects does not provide us with all the ideas that support our overall cognition. It does not provide us with the conceptual contents required for cognitive rationality. But, against this background, Hume’s (and Kant’s) path radically diverges from that of the rationalists. These latter, admittedly in different ways, identify the source of the cognitive limits of object representation in its sensible character. The content of sense experience is confused and obscure, fundamentally because of the mediation of body and the senses. What is required is a different, clear, and distinct mode of object representation; and reason and the understanding can secure it. These faculties, which are free from the constraints of sensibility, afford the ‘pure and intellectual view’ and deliver the ideas ‘of so refin’d and spiritual a nature’ that acquaint us with the right kind of (intelligible, rational) objects for mathematical and in general a priori knowledge. By contrast, Hume (and, to some extent, Kant) understands the cognitive limits of sense and memory in terms of limitedness rather than of confusion and obscurity. Sense and memory are not the locus of obscure and confused ideas; their content is not a defective, undetermined form of what would be clear and distinct to the intellect. Sense and memory are marked by the natural limits of our primitive cognitive contact with objects; but within such limits, they are as clear and distinct as human cognition can be. The cognitive gaps that sense and memory leave open can be filled only by a separate, nonrepresentational cognitive faculty. If sense and memory are not intrinsically flawed, the task they set is one of articulation and integration, not of extraction by the intellect of a rational core of content. This task is performed by the imagination, a perfectly natural, empirically scrutable, contentproductive faculty. Of the ideas presumed to be of ‘so refin’d and spiritual a nature’, we should rather say that they fall ‘under the conception of the fancy’. In this way, the imagination not only contributes to fully explaining the nature of our ideas and the principles of our understanding: it acts as a closure (that’s all) clause in Hume’s naturalistic logic.