The EFMD Business Magazine | Iss1 Vol.17 | www.efmd.org Business School Sustainability Revisited: Sustainable No More?

Global Responsibility?

We hold the questions to which there are no simple answers and on which we must urgently act. Join a collaborative and impactoriented inquiry focused on making global responsibility real in how we learn, live and lead.

Visit grli.org

In strategic partnership with

Global Focus

The EFMD Business Magazine Iss.1 Vol.17 | 2023

Executive Editor

Matthew Wood / matthew.wood@efmdglobal.org

Advisory Board

Eric Cornuel

Howard Thomas

John Peters

Design & Art Direction

Jebens Design / www.jebensdesign.co.uk

Photographs & Illustrations

©Jebens Design Ltd / EFMD unless otherwise stated

Editorial & Advertising

Matthew Wood / matthew.wood@efmdglobal.org Telephone: +32 2 629 0810

www.globalfocusmagazine.com www.efmd.org

©EFMD

Rue Gachard 88 – Box 3, 1050 Brussels, Belgium

More ways to read Global Focus

You can read Global Focus in print, online and on the move, in English, Chinese, Russian or Spanish

Go to globalfocusmagazine.com to access the online library of past issues

Your say

We are always pleased to hear your thoughts on Global Focus, and ideas on what you would like to see in future issues.

Please address comments and ideas to Matthew Wood at EFMD: matthew.wood@efmdglobal.org

3

Business School Sustainability Revisited: Sustainable No More?

Kai Peters and Howard Thomas reflect on their 2011 Global Focus article and 2018 book, and update the thoughts and developments since then

11

Is small beautiful? An exploration of Micro-credentials

A panel of experts consider: “Is small beautiful?”, hoping to shed some light onto the subject of micro-credentials, a topic that both excites and exercises policymakers, employers, educators, and learners

17

Defining environmental challenges

CEMS academics and corporate partners explore the implications for business leaders and schools alike 23

Academics working across the boundaries - conflict of interest or mutual enrichment?

In contrast to most of their counterparts in the corporate sector, business school academics are often given the opportunity (if not encouraged by some schools) to work beyond the boundaries of their schools, say Patrick De Greve, Nicola Kleyn and Mark Smith

29

An Emerging Market Perspective on the Internationalisation of Business Schools

Many schools from these regions are committed to internationalisation but face both barriers and opportunities not always appreciated by those from economies where resources and infrastructure are more readily available. By Wafah El Garah, Piet Naude and Michael Osbaldeston

1 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

41

Contents

35

Business School 5.0: Continuously Rewired, BoundarySpanning

It has become somewhat commonplace to argue that business schools need to transform themselves. True, but in Ulrich Hommel and Martin Meyer’s view, too limiting to chart the trajectory ahead

41

The Power of Teams and Communities

Griet Houbrechts and Anna Jirova ask: how do we best prepare our institutions to thrive in this fastpaced and barely predictable environment?

47

From research for publication to research for impact

Thousands of articles are published every year in “top academic journals”, however this massive effort rarely impacts businesses, policies or society, either directly or indirectly. By Kamran Razmdoost

51

Building reputation through quality management of accreditations and ranking

Many business schools would testify that before they entered the world of accreditations and rankings, they gave less attention to analysing and strategising stakeholder perceptions and public conversations about their school, Daniel Kahn, Björn Kjellander and Benjamin Stévenin ask why

57

79

How Business Schools can help employers effectively manage an ageing workforce Realising the true value of older workers is crucial, says Sarah Hardcastle

85

Six strategies to enhance international recruitment Cara Skikne conducted a series of interviews with professionals in the higher education space to fnd some fresh ideas to take international student recruitment to the next level

89

The Innovative Management Education Ecosystem

Jordi Diaz, Daphne Halkias and Paul W. Thurman ask how business schools can join the reskilling revolution?

93

High wire act: The reinvention of African business schools to amplify their impact

Should African business schools be turning their focus inwards to tackle the continent's most signifcant problems or outwards, to compete against the best-ranked schools in the world? By Jon Foster-Pedley

99

Getting

unstuck: how to put your university´s transformation back on track

If your institution is stuck between the certainties of a successful past and the unrealised opportunities of the future, getting unstuck is easier than it might appear - here´s how. By Giuseppe Auricchio and Evgeny Káganer

63

How applied strategic projects can help executive participants drive change

Accelerated by transformative global events in the last few years, it has become ever more critical for senior and aspiring leaders within organisations to ‘re-set’ their understanding of markets, organisations, customers, and citizens. Mike Cooray and Rikke Duus investigate

73

Teaching sustainability management

Rüdiger Hahn observes: I have two children, both at kindergarten age. When they approach me or my wife with questions on sustainability it always strikes me that we could be so much further forward with sustainability if everybody would do their part

AAUBS collaborates with international organisations to solve global challenges through data science Students and researchers at Aalborg University Business School (AAUBS) explore data-driven insights to help the missions of UNESCO, OECD and other organisations. Roman Jurowetzki reports

103

Eight Pillars of Employee Engagement and Evolutionary Change

Vlatka Ariaana Hlupic outlines the eight pillars of humane leadership, employee engagement, and evolutionary change that are taking place in businesses right now, right across the world.

109

Social education becomes more relevant at Fundação Dom Cabral

Fundação Dom Cabral (FDC) has evolved as one of the most relevant business, leadership and executive training schools in the world. Nádia Rampi looks at its focus on social education

2 Contents | Global Focus

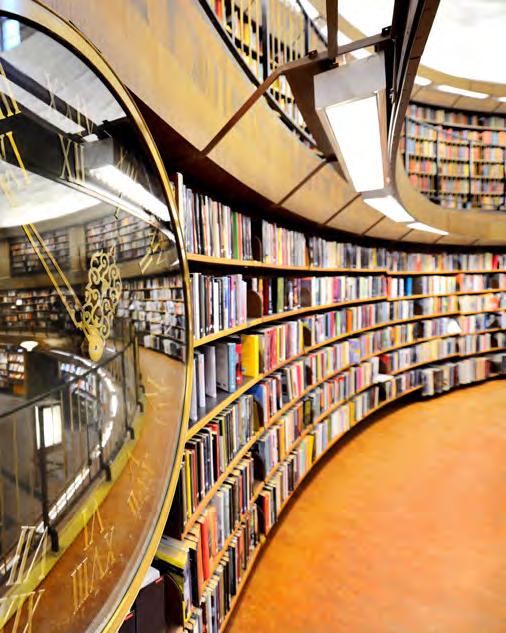

Business School Sustainability Revisited: Sustainable No More?

3 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

Kai Peters and Howard Thomas reflect on their 2011 Global Focus article and 2018 book, and update the thoughts and developments since then

If one looks dispassionately at the business school landscape, it quickly becomes obvious that not all business schools are alike

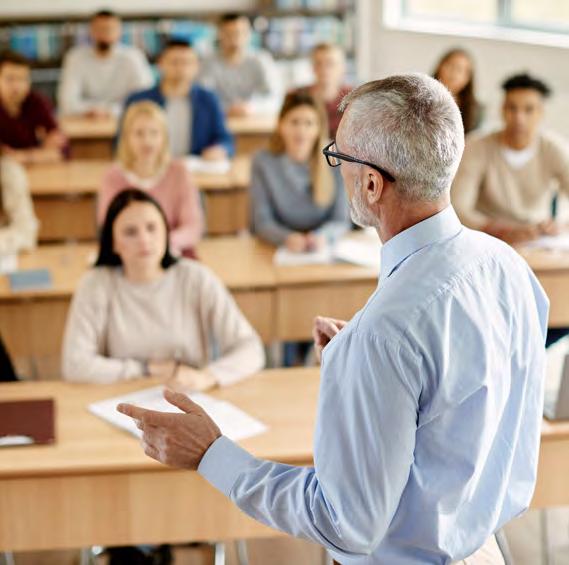

In 2011, we wrote an article for Global Focus entitled “A Sustainable Model for Business Schools”. In that article, we explored an area we felt was under-investigated: namely examining the sources and uses of business school income. How much did students or executive education participants pay? How many were in a classroom at the same time and consequently how much daily income was generated by the faculty member standing in front of the class? How many hours did faculty members teach annually and consequently what were the carrying costs per faculty member per day? When one applied these measures, what could one conclude about a sensible mix of activities to ensure that a business school generated sufficient surpluses from reasonably predictable and sustainable sources.

The article took on a life of its own, ultimately leading to a book which appeared in 2018 entitled “Rethinking the Business Model of Business Schools”. The book provided greater detail and drew attention to the range of per diem income that faculty could generate. At the low end of the spectrum, perhaps surprisingly, was consulting and customised executive education where an individual faculty member could, except at very exclusive business schools, generally generate €2500 to €10.000 per diem. At the other end, it was really a matter of how many students were in the classroom paying how much. The highest per diem income we could identify was a US-based Executive MBA class where there were 80 students in the cohort each paying $180,000. This led to a per diem income for the faculty member at the front of the class of about $240.000. Surely business schools needed to reflect on their portfolio mix and class compositions more than we felt they all did.

Now, over ten years after the original article and from this side of Covid, this short article is meant to reflect on, and update, the thoughts we had originally voiced and the developments since. To achieve this, we will look at the business school eco-system through a number of lenses, and draw on some of our own recent work, as well as a small number of additional sources (a complete literature update simply cannot be captured in a short article) which address contextual developments. We look at four areas: structural issues at universitybased and independent business schools; we revisit sources of income; investigate spend on students and the value they get from their business school; and lastly ask what alternatives to traditional business school education have arisen since 2011 should students, and often their parents, feel that ever-increasing tuition fees no longer offer sensible value for money.

1. Structural Issues

If one looks dispassionately at the business school landscape, it quickly becomes obvious that not all business schools are alike. In a 2006 Advanced Institute of Management Research (AIM) white paper, Ivory et al, looking at the UK context, differentiated between elite, research-intensive business schools and inclusive, teaching-oriented institutions. That differentiation still resonates but misses out on an additional crucial factor – whether the business school is independent or part of a wider university. This second factor makes a world of difference from many perspectives. In an independent business school, the dean

4 Business School Sustainability Revisited: Sustainable No More? | Kai Peters and Howard Thomas

is either the boss, or in some cases, second-incommand and reporting to a managing director. There are challenges brought about by the need to have all professional service and compliance functions on the payroll at an independent business school compared to a university where they are shared across a broader portfolio. Size, thus matters, as does the mix of a fixed versus variable payroll. In any case, the institution is autonomous and has the rights and responsibilities to steer the business school in a chosen direction.

At many university-based business schools, the job of the dean is now increasingly to tow the university party line and to hand over as much cash as possible to the central university coffers where it is spent to cross-subsidise other faculties and research centres. In addition to this long-bemoaned and increasingly punitive central university taxation level, an additional trend is evident in many institutions: the increasing centralisation of all but teaching. Anecdotally evident in Australian institutions as well, it is a clear trend in the UK environment. In Peters (2021), the trend to centralisation is critiqued insofar as it diminishes the ability of the business school to be responsive to market trends and additionally, it imposes layers of often unreliable bureaucracy on the school. As an example, when marketing and recruitment is centralised and sufficient student numbers are not attracted, the business school has no opportunity to counteract the shortfall. A recently published Chartered Association of Business Schools white paper (2022) expands on this. The research, conducted among 51 UK business school-based professionals confirms this trend. The report concludes that where centralisation works, professional service staff report centrally but are embedded within the business schools. Strains appear when the balance between centralisation and decentralisation is not well thought through and staff sit and report centrally. In this case, the perceived efficiencies are negated by the lack of responsiveness.

Inclusive Free Standing University Based 5

Often private, for profit, and teaching only

Exclusive Often private, but elite research based Often elite and research intensive EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

Across the world, extensive disruption has been caused by COVID-19. In many cases, student numbers were significantly reduced. While teaching online mitigated some of the damage, it has become clear that in many cases progression rates have fallen significantly. Kong and Patra (2022), writing about the Singapore experience, note an additional concomitant factor – geopolitics. Government support for university funding is reducing, tuition caps for national students have been imposed, and business schools thus increasingly look to international students to fund their activities.

Covid-19

Across the world, extensive disruption has been caused by COVID-19. In many cases, student numbers were signifcantly reduced

Often broad access, often research-lite

2. Portfolio of Activities

In the UK, the situation has been made even worse through Brexit. Where in the past, EU students were entitled to UK funding, they are now considered international students who are expected to pay at least twice as much in real money, not the previous half-as-much through the previous graduate tax loan scheme. In that scheme, loan repayments are required once the graduate reaches an income level of about £30,000 per annum. To note additionally, is that the interest rates charged are adjusted annually at RPI plus 3% which in these high inflationary times is very expensive indeed. In practice, this has led to the disappearance of nearly all EU students who had previously comprised up to about 20% of some UK business schools’ student body. Business schools, and universities, now scramble to make up this shortfall through attracting students from other markets. In the UK, this has meant to look for ever greater numbers of students primarily from India, China and Nigeria. Not only does this lead to an unbalanced classroom experience, it is also a dangerous business model to have so many of one’s eggs in three politically volatile

baskets exacerbated by changing work permit regulations in the host countries. At present, 20% of students in the UK are international. Given that they basically pay twice as much as national students, something like a third of income is now derived from these international students. Indian students are in the UK because of the right to a post-study work visa. Similar visa regulations exist in Australia, Canada and the US among other countries. These rules could change at any minute. In our humble experience, trusting the government is even more fraught than trusting centralising universities.

The effects of changing conditions have affected different ‘products’ in different ways. Undergraduate programmes face larger challenges due to their length and overall cost. PG programmes have grown, but in many schools this is due to international students, certainly in the UK, most would not exist without them. Executive education programmes, all but annihilated during Covid, have not returned to pre-pandemic volumes. Identifying an ideal portfolio mix is thus becoming increasingly challenging.

6 Business School Sustainability Revisited: Sustainable No More? | Kai Peters and Howard Thomas

3. Spend on Students

So, what are students actually getting for their money? Hazenbush (2022), writing for the Graduate Management Admissions Council, as well as Kirkpatrick (2020) writing as managing director of careers at Kellogg School of Management cite the usual reasons: greater career opportunities, access to new industries and functions, accelerating career paths, expanding networks, and, of course, increasing salaries significantly. No surprises there.

While all of these factors will apply for students at many schools, there are a number of factors that candidates applying to business school should consider additionally. Specifically, what happens to the money that students spend on ever-higher tuition fees? We’ve already noted that international students are often required to spend twice as much as local students. Whether they get twice as much in services and value is surely open to discussion. We posit that there is also a significant difference between standalone and university-based business schools. No doubt stand-alone business schools do need to pay for all kinds of professional services, estate-maintenance, etc., one can make a case that spending is fundamentally used for business school attendees.

At university-based business schools, it is generally much more complex. Since its introduction in 2000, UK universities are required to submit detailed financial information to the government. The data, known as TRAC, “The Transparent Approach to Costing” is based on “Time Allocation Studies” where faculty members must fill in a time sheet at three different points in the academic year to show what students get. Data is provided on a subject area basis. As will be no surprise, STEM subjects like medicine and engineering cost about twice as much to deliver as do business subjects. At a detailed level, one can also see that in many university-based business schools, about 25% of tuition is directly attributable to teaching, 50% goes on central university functions where one can ask oneself whether business students benefit, and another 25% goes on further cross-subsidisation.

25%

in many university-based business schools, about 25% of tuition is directly attributable to teaching

If it isn’t the actual teaching provision that generates value for the student, it needs to be the additional services received. At stand-alone business schools, the career services to student ratio can be 1:50. At university-based schools, where career services have been centralised, it can be more akin to 1:200 or lower.

The question candidates and their parents must ask themselves is what is the trade-off between tuition costs and the quality of the experience? Will attending a particular institution indeed provide all the benefits noted by Hazenbush and Kirkpatrick, or will one’s career prospects be that of a “graduate burger flipper”?

7 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

4. Choices

Rather than only considering the tradeoffs between stand-alone versus universitybased business schools or between inclusive and exclusive business schools, as Ghosh and Thomas (2022) as well as Fournier and Thomas (2022) note, candidates also have other options that are well worth considering. These include lower cost degrees from prestigious institutions, sandwich courses that combine study with work and progression pathways including online / face-to-face combinations. Hommel and Peters (2021) point to the irony of the broad range of countries that had signed up to the Bologna Accord, but where it is nevertheless very difficult to switch institutions and receive accreditation of prior learning (APL). This dilemma has been exacerbated by the many micro-credentials that are available as online learning. Two agreements, notably the

European MOOC Consortium and the Digital Credentials consortium which includes Europe and North America, have developed common formats and suitable credits for completed and assessed modules. Additionally, some universities, MIT, and Boston University, have developed MicroMasters, effectively one-third of masters’ degrees. They are a bargain at $1500 all in. They are also recognised by 20+ other institutions as a pathway onto their masters, allowing students to waive one-third of the courses and fees. In theory, one could complete two MicroMasters at MIT and switch to another of the many institutions that can accredit up to two-thirds from elsewhere. All-in costs for the masters, two-thirds of which would come from MIT, would be around $5000. As a comparison, the face-to-face version of the MIT masters costs about $77,000. The MBA, at MIT, by way of comparison, today suggests a budget of $240,000 for tuition plus accommodation. Of related interest here is that France has implemented a state-run system called VAE, Valorisation des Acquis de l’Expérience, of accrediting prior-learning as the Ministry of Education was fed up with institutions not recognising learning from elsewhere.

A similar APL construct exists where students have acquired professional body standards. Chartered members of bodies ranging from accounting to human resource management can gain two-thirds accreditation of prior learning from a host of universities and ‘top-up’ to a masters degree for one-third of the cost of the complete programmes.

An additional route one could consider is that of apprenticeships. In many countries, it is possible to complete one’s UG degree in a structured, government-supported manner, on a part-time basis in combination with employment. The tuition cost to the student is zero, and, for example at Accenture, they receive an annual salary of approximately £20,000 per year during their apprenticeship.

8 Business School Sustainability Revisited: Sustainable No More? | Kai Peters and Howard Thomas

5. Conclusion

From the perspective of business school leadership, the need to closely monitor the portfolio mix and related income streams in 2022 remains as it did in 2011. That said, significant changes have come about within the portfolio. The number of international students in the UK has nearly doubled with most of that growth, and thus increasing dependence, on India and China. This same trend appears to hold true in most of the large host countries including Australia, Canada and the United States. European students are increasingly looking to Europe for education with an ever-increasing number of courses being offered in English. Where funding is direct to the university, this can be to the consternation of local ministries of education. Where the ministries have cut back on university funding, international students are needed to balance the books for business schools. On the positive side, there are new opportunities with innovative pathways, top-ups, APL and microcredentialling, and apprenticeships.

We note that in university-based business schools, students, especially international students, need to be alert to the fact that much of their tuition fee is spent on activities that have very little to do with them and from which benefits can be tangential at best. Candidates need to be alert to what it is they want from management education. If they are after knowledge, skills and behaviours to, for instance, manage in the family business, it is a different choice set than if they need extensive career support facilities and connections to powerful alumni.

Ghosh and Thomas (2022) look at the question of value from a slightly different angle: whether the value from management education should be considered a public or a private good. From the public good perspective, they note that the rite of passage of attending higher education is generally recognised by civil society. Additionally, the skills developed in that process are economically useful. Nevertheless, society increasingly questions costs involved to the state. From the private good side, especially for students attending elite

educational institutions, they note elements similar to those noted by Kirkpatrick (2020) and Hazenbush (2022), but also critique the Veblenite conspicuous consumption. In contrast to Kirkpatrick and Hazenbush, they point out that elite institutions may be a significant factor in subsequent income-earning potential for graduates, but endogenous variables make causation claims difficult.

In conclusion, we suggest that business schools, wherever possible, focus as much on the value of their education to students as on the income generation of the portfolio mix of their activities. Only if genuine value is produced for students, and the willingness to pay is recognised by both the students and the students’ parents, can it be sustainable over the long run. The challenge is thus to identify programmes and services that are both affordable to students but also lead to positive feedback and lifelong benefit.

9 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

About the Authors

Kai Peters is Pro-Vice-Chancellor, Business and Law, at Coventry University, UK.

Howard Thomas is the lmmediate Past Dean of Fellows at the British Academy of Management, Emeritus Professor at Singapore Management University and Senior Advisor at EFMD Global.

Further information: Chartered Association of Business Schools (2022) Exploring Professional Service Models in UK Business Schools https://charteredabs.org/ exploring-professional-services-models-in-uk-business-schools/ accessed 14 October, 2022

Fournier, S. and Thomas, H. (2022) A zero-based cultural perspective on dealing with the hybrid reality of teaching in business schools. Global Focus: THE EFMD Magazine https://www.globalfocusmagazine. com/a-zero-based-cultural-perspective-on-dealing-with-the-hybrid-reality-ofteaching-in-business-schools/ accessed 24 October, 2022

Ghosh, A. and Thomas, H (2022) The Global Pandemic and Management Education: Is Management Education a Valuable Long-Lived Financial Asset? In Managing Complexity and COVID-19 in Life, Liberty, or the Pursuit of Happiness. Edited By Ghosh, A., Haldar, A., and Bhaumik, K. London: Routledge

Hazenbush, M. (2022) Is Business School worth it? https://www.mba.com/ business-school-and-careers/salary-and-roi/is-business-school-worth-it accessed 17 October, 2022

Hommel, U., Peters, K. (2021) Shared Learning in Higher Education: Toward a Digitally-Induced Model in A. Kaplan (editor): Digital Transformation and Disruption of Higher Education, Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, Ivory, C., Miskell, P., Shipton, H., White, A., Moeslin, K., & Neely, A. (2006). UK business schools : historical contexts and future scenarios: summary report from an EBK/AIM Management Research Forum. (Academic White Paper). Advanced Institute of Management Research (AIM).

Kirkpatrick, L. (2020) Is an MBA Degree Really Worth it? Harvard Business Review online https://hbr.org/2020/12/is-an-mba-degree-really-worth-it Kong, L. and Patra, S. (2022) Universities in and Beyond a Pandemic in Managing Complexity and COVID-19 in Life, Liberty, or the Pursuit of Happiness. Edited By Ghosh, A., Haldar, A., and Bhaumik, K. London: Routledge Office for Students (2022) TRAC Data 2020-2021 https://www. offceforstudents.org.uk/publications/annual-trac-2020-21/ accessed 19 October, 2022

Peters, K., Smith, R., & Thomas, H., (2018). Rethinking the Business Models of Business Schools: A Critical Review and Change Agenda for the Future. Bradford: Emerald Publishing Peters, K., Thomas, H. (2011). A sustainable model for business schools. Global Focus: The EFMD Business Magazine, 5(2), 24-27.

Peters, K. (2021) The Marketisation of Higher Education. In Branch, J.D., (editor) The Marketisation of Higher Education, London: Palgrave MacMillan UK Department of Education (2019) Understanding costs of undergraduate provision in Higher Education: Costing study report

Authors – KPMG LLP https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/ uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/fle/909349/Understanding costs_of_undergraduate_provision_in_higher_education.pdf accessed 19 October, 2022

10 Business School Sustainability

No More? | Kai

and

Revisited: Sustainable

Peters

Howard Thomas

Is small beautiful? An exploration of Micro-credentials

At the EFMD Annual conference in Prague in June 2022 a panel of experts considered the question: “Is small beautiful?”, hoping to shed some light onto the subject of micro-credentials, a topic that both excites and exercises policymakers, employers, educators, and learners. By Keith Pond

11 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

So, why micro-credentials?

Micro-credentials have gained the attention of the online community in recent times but have a long history according to panel member Professor Mark Brown, Director of the National Institute for Digital Learning at Dublin City University. A St. John’s Ambulance First Aid Certificate from 1833 is a very early example of a skills-based short course where a microqualification signals a specific proficiency.

Since those pioneering days of credentialling, micro-credentials have become synonymous with short, flexible, stackable, affordable, inclusive qualifications focused on skills development. Most recently they have proliferated through the medium of online instruction.

12 Is small beautiful? An exploration of Micro-credentials | Keith Pond

Contrast those characteristics with the more traditional university offerings of bachelor or master degree programmes - typically longer, more rigid, costlier, and more selective, and often subsidised by the state, and you begin to understand why micro-credentials give opportunities to upskill workforces and engage lifelong learners in ways that more conventional qualifications do not. Although it is often intended that micro-credentials complement traditional academic courses, rather than replace them. Courses offering micro-credentials have relevance for other key stakeholders as well:

• Employers who need up-to-date skills in their recent recruits and established workforce.

• Universities and business schools offering “taster” courses to attract students and to offer flexibility in the executive education area.

• Commercial providers, seeking to extend their markets

• Learners seeking low cost, low impact ways to boost their studies and update their skills.

• Faculty members keen to maintain and enhance their credentials in teaching and facilitation.

Andy Poole, Partnerships Director at Coursera, contributed to the discussion, emphasizing the focus on skills demanded by employers – typically, IT, project management, cyber-security and data analysis skills. Often these are skills that update continuously and so do not fit comfortably in a settled curriculum. He also notes the rapid expansion of microcredential offerings and the awakening of higher education to this innovation.

Figure 1. The credential ecology

…and how are micro-credentials defined and regulated?

Maria Kelo, Director of the Institutional Development Unit of the European Universities Association (EUA), our final discussant, commented that whilst micro-credentials were well established, there is no single definition of them. Working with others in the European MOOC Consortium, Maria has recently contributed to work that promises a common framework and language that aligns with current qualifications. To date there is no agreement on the size (in terms of credits), duration, level(s), or regulation of micro-credentials.

13 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

Credit Bearing Non Credit Bearing Bundled Unbundled

Macro-credentials Formal Accredited Degrees Non-status Awards Semi-Formal Courses Non-Accredited Nano-credentials Informal & Non-Formal Digital Badges & Certificates Micro-credentials Formal & Semi-Formal Accredited & Stackable Credential Ecology

The “ecology” indicates that unbundled micro-credentials have the capacity to be credit bearing – although many are not

Mark Brown, and fellow authors, provide a very useful “credential ecology” in their 2020 paper :

The “ecology” indicates that unbundled micro-credentials have the capacity to be credit bearing – although many are not. This raises the issue of acceptance and quality. Without an agreed global definition of micro-credentials, it may be many years before an accepted quality benchmark is developed. In the EU, a definition was agreed in June 2022:

“ ‘Micro-credential’ means the record of the learning outcomes that a learner has acquired following a small volume of learning. These learning outcomes will have been assessed against transparent and clearly defined criteria. Learning experiences leading to micro-credentials are designed to provide the learner with specific knowledge, skills and competences that respond to societal, personal, cultural, or labour market needs. Micro-credentials are owned by the learner, can be shared and are portable. They may be stand-alone or combined into larger credentials. They are underpinned by quality assurance following agreed standards in the relevant sector or area of activity.”

14 Is small beautiful? An exploration of Micro-credentials | Keith Pond

Unbundled

Not all micro-credentials have defined credits attached to them, nor are there any systematic methods or approaches to recognise such credits

It is inevitable that further regulation of micro-credentials will emerge. The simplest assumption is that regulators will use the same sort of quality framework as existing programmes offered by HEIs. But this is limiting as it excludes alternative providers.

Alternative providers (i.e. non-HEI providers, which could be private companies, public bodies, non-profit organisations, or others) are a real complication. “Micro-credential” is not a trademarked or regulated term. Unlike the term “degree”, anyone can use it, without meeting a set of standards or regulations. However, good practice can be promoted so that learners are clear about what Dil Sidhu from edX calls “the 7 Cs”:

This leaves the field open for business schools wishing to promote themselves using “tasters”, or hoping to reach larger audiences, widen access to learning and engage alumni and employers. For example, through a Coursera partnership with Highered, industry microcredentials are available to, and being used by EFMD member schools around the world to help students build skills for high-demand job roles using content from leading organisations including Google, IBM, and Meta.

…but how can learners use micro-credentials?

The short answer is that it really depends, suggests Maria Kelo. Clearly, they can develop new skills or update their practice with technology-based applications noted earlier. However, for the moment, not all microcredentials have defined credits attached to them, nor are there any systematic methods or approaches to recognise such credits. The most likely scenario is that acceptance will be on a case-by-case basis. Institutions with rigorous quality assurance processes, such as HEIs, may have an advantage in the short-term.

Is the topic current and in demand by employers?

What is the reputation of the institution and faculty/subject matter experts?

Do employers look favourably upon this micro-credential?

What is this going to cost me financially and is it worth it?

What is the commitment I'm being asked to make to complete?

Will I be able to improve my career prospects with this micro-credential?

Will completing this micro-credential connect me with a community of learners?

15 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

Figure 2. The 7 Cs of Microcredentials

Content Creator Credential Cost Commitment Consequences Community

HEIs

Institutions with rigorous quality assurance processes, such as HEIs, may have an advantage in the short-term.

In practice, credential evaluation is cumbersome, slow, and expensive. For systems that consider the institution as a whole (where institutions are self-accrediting and self-awarding) the evaluation of single micro-credentials is left to the internal quality assurance mechanisms of the institution. External quality assurance bodies, such as EFMD, can then review the internal mechanisms explicitly related to micro-credentials. As this is still something quite new, many institutions probably do not have focused mechanisms and policies in place, but the expectation is that they should create and develop them – and swiftly!

The vision of many HEI and commercial providers is to achieve a quality benchmark through currency, efficacy, and branding. This will enable micro-credentials to be applied to social media profiles, such as LinkedIn, to CVs and to university applications. Micro-credentials that conform to the benchmark should also be stackable, in a true modular sense – another key benefit for the part-time and non-traditional learner. There is clear opportunity here for external bodies to offer their own benchmark standards and potentially an “exchange” facility to reassure potential learners of the quality of the credential.

So, is beauty in the eye of the beholder?

There is much benefit that so many can gain from micro-credentials. Institutions, employers, governments, and learners will all find them helpful towards their separate and different objectives.

In the longer term, national authorities will wish to regulate, hopefully for quality assurance purposes. This should work well, provided national governments and their agencies are guided by global good practice and the needs of all stakeholders.

If micro-credentials can open higher education to less well represented parts of global society and empower them to make a difference to their own lives then, yes, there’s beauty in that.

About the Author

Keith Pond is Director of the EFMD Global Online Course Certification Scheme (EOCCS), and chaired the panel on micro-credentials at the EFMD Annual Conference in Prague in June 2022.

Further information:

EU, 2022, A European approach to micro-credentials available at: https://education.ec.europa.eu/education-levels/higher-education/ micro-credentials

Brown et al., 2020, The Global Micro-credential Landscape: Charting a New Credential Ecology for Lifelong Learning, National Institute for Digital Learning, Dublin City University

EU, 2022, Council recommendation 2022/C 243/02, available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.C_.2022.243.01.0010.01.ENG

Dil Sidhu from edX helped to develop the panel but was unable to join it. Many thanks Dil.

16

of Micro-credentials | Keith Pond

Is small beautiful? An exploration

Defning environmental challenges

CEMS academics and corporate partners explore the implications for business leaders and schools alike

One of the most efficient ways to understand these environmental challenges is to use the planetary boundary framework (established by Rockström and the Stockholm Resilience Centre). This identifies nine areas of concern and shows how they are all deeply interrelated

17 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

In September 2021 a survey of 4,206

CEMS alumni from 75 countries identified environmental concerns as the greatest challenge facing modern business leaders. CEMS decided to harness the power of its unique network of academics and corporate partners from around the world to explore what ‘environmental challenges’ means in practice, what type of leaders we will need to address these challenges and how business schools should be responding.

It’s easy to talk about ‘environmental challenges’ but what do you see those challenges as actually being?

Dr Camille Meyer, University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business: Currently, climate change is dominating environmental coverage. In fact, we are facing a whole raft of environmental challenges. Biodiversity loss in particular is extremely concerning as at the current rate of disappearance of species and extinction, we are facing the risk of a humandriven sixth mass extinction

Unfortunately, although discussion is emerging it is not yet where it should be. While some geographical regions might be said to be leading the conversation, no-one has yet grasped the full complexity of the issues we’re facing. Equally there needs to be more awareness of impact - how that will differ around the world and how that effects the urgency of action by individual governments. It is crucial to raise awareness of the full planetary boundarieswhere they’ve been crossed, where we are facing more risk and how each impacts the other.

One of the most efficient ways to understand these environmental challenges is to use the planetary boundary framework (established by Rockström and the Stockholm Resilience Centre). This identifies nine areas of concern and shows how they are all deeply interrelated. Take land-use change, for example. Deforestation changes the land-use, impacting the biodiversity and increasing greenhouse gas emissions. Land-use change also effects the phosphorous and nitrogen cycles that are causing dead zones in the ocean.

18

environmental challenges | The CEMS Network

Defning

Professor Lars Jacob Tynes Pedersen Head of the Centre for Sustainable Business at the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH): A further challenge is the debate about who is responsible for driving action. Conversations around a company’s footprint can also be complex. Some pollutants (such as emissions coming out of a chimney) are easy to track back to a particular company – but others (such as microplastics in the sea) are almost impossible. For this reason, we are having two conversations simultaneously. One is around the sustainability effects of the business broadly speaking, and how companies might address them by making changes to business models, strategies and operations. The other is a more value-laden discussion. What should a company act on, regardless of whether it is a win-win opportunity for them? This is exemplified when you consider it in terms of the social arena: a company must take responsibility for human rights violations, yet the discussion is more ambiguous when it comes to the environment.

Mirko Warschun Senior Partner and Managing Director, Board Advisor and LeadConsumer and Retail Business, Kearney: It’s a vast topic that will certainly have an impact on business, and companies must plan accordingly. For example, rising temperatures and extreme weather conditions will impact agriculture, which in turn, will impact business. Elsewhere, water scarcity will force populations to move. At Kearney, on every project, we consider these topics daily because no business decisions can be taken without first understanding the environmental challenges and implications from industry to industry. If organisations want to be successful, this cannot be delegated to a Chief Sustainability Officer, it’s the daily duty of all leaders.

Angela Hultberg

Global Sustainability

Director, Kearney: What business leaders must understand, and the good ones already do, is that the climate crisis will have an impact on every aspect of business regardless of how we handle it. For example, you can pay to build a wall to keep the water out of your building, or you can pay to clean it up after it’s come in.

Either way, you must do something. Leaders must assign a value to sustainability and a cost to inaction. They must understand not only how climate change is directly impacting their business but what they could lose if they don’t act. Then, irrespective of industry, leaders should feed this thinking into business planning, priorities, and investment decisions. What type of leaders will we need to tackle this crisis?

What needs to shift in order for global organisations to really make an impact when it comes to environmental challenges?

Professor Dirk S. Hovorka the University of Sydney Business School: As companies, we must also move away from the idea that growth is the ultimate goal and that the world’s resources are infinite. Sustainable development is an oxymoron, as you cannot develop indefinitely - there is going to be an end to growth in a finite planet. Leaders need to recognise that if they want their organisations, people and biodiversity – the world – to thrive in the future, they have to change their ideology.

It must shift away from the primary purpose of profit and prioritise other values. We must shift to the primary goal of being good ancestors. To be a good ancestor is to look out for the wellbeing not only of people but of the

Rising temperatures and extreme weather conditions will impact agriculture, which in turn, will impact business

19 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

entire biosphere. Creating capital and wealth and institutions and workforces — these are only intermediate goals which should serve the ultimate goal of human and animal wellbeing. To achieve this, we need to have a broader perspective and broader collective agreement on the goals we are trying to achieve, including leaving a legacy for the future

Heidi Robertson Group Head of Diversity and Inclusion at ABB: We cannot leave the solution to grand environmental or societal challenges up to governments or global corporations. Each and every one of us can make decisions that influence the world for future generations. It takes all of us to succeed. Every day. For an organisation to make a meaningful impact in this regard, I believe that we must shift from a hierarchical to an ecosystem-oriented modus operandi.

In ABB, we operate in a decentralised business model where empowerment and accountability are key principles. Each of us comes together as pieces of the puzzle to drive the company, environment and community around us, forward.

We have found that younger generations, in particular, thrive on this bold approach emphasizing empowerment. There is an expectation and a desire to influence change, not to be part of a pattern of directive leadership. That is why I am so positive about the next generation—there seems to be an innate courage to take real and decisive steps.

What type of leaders will we need?

Christine Ip CEO Greater China, United Overseas Bank: Firstly, it’s essential that leaders have a strong, growth mindset. This means they are aware of how every small thing can make a positive difference and they exemplify that by living a healthy and disciplined lifestyle, in terms of physical and mental health and wellbeing, and an appreciation of the natural world.

Secondly, leaders must have a determination to succeed and a strong ability to execute. ESG can be very abstract, so leaders need to successfully share the vision, set out very clear objectives, and then set measurements around them. At the end of every year, many slight changes across an organisation can add up to a quantum leap.

20

Defning environmental challenges | The CEMS Network

Founded in 1988, CEMS is a global alliance of 34 business schools and universities collaborating with 70+ industry-leading multi-national corporations, 8 social partners and over 16,000 alumni to deliver the renowned CEMS Master in International Management.

Thirdly, leaders must cultivate an open and inclusive mindset. They can and should draw on past experience to inform decision-making, but the world has changed to such an extent that we need to look to the younger generation as well. They are more conscious of ESG and leaders should be humble, listen and learn from them.

Crucially, leaders must model the behaviours they want replicated across the organisation. This isn’t about setting KPIs – although that’s important – but creating a culture of trust that empowers employees to make decisions that are based on wider ESG considerations. By having KPIs in place that look to wider ESG measures and modelling the right behaviours, people will make slight changes that together add up to a big shift for an organisation.

Leaders must also find the courage to do the right thing – focusing not only on the future of our customers, but on future generations.

Professor Andrew Delios NUS Business School National University of Singapore: We will need leaders who understand who they are, are in touch with their personal values and use these values as the basis for their tough decisions. In an increasingly complex world, its vital to be selfaware, as this will drive your decision making. Such self-aware leaders will naturally be drawn to organisations whose vision, mission and strategic objectives espouse their values.

Equally, leaders will need to value the importance of introspection, continually reflecting on how they’ve handled challenging situations and how they could do better. This process creates truly authentic leaders that people are willing to follow. Talented people everywhere will be drawn to these leaders, and their organisations, and work collaboratively to achieve shared goals.

21 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

We need bold leaders who will empower employees to develop this change, support it, fight through complacency, build coalitions and martial stakeholders

We need bold leaders who will set strong organisational objectives that drive the cultural change needed for a greater focus on ESG issues. They must empower employees to develop this change, support it, fight through complacency, build coalitions and martial stakeholders. They need the courage to push the rock to the top of the mountain and then let it roll down.

The will is there, especially among the younger generation. Employees are all citizens who know that something needs to be done to address environmental challenges and who want to make a change — they just need someone to lead them in that direction. If bold, self-aware leaders make these changes they will be rewarded as they will be preparing their people and organisations to manage multiple strategic objectives, which will be key to being a successful corporation in the future.

Professor Dirk S. Hovorka the University of Sydney Business School: Our leadership philosophy must change into something far more collective to avoid climate catastrophe. One common mistake, made by many business schools, is the promotion of the ‘guru’ leadership philosophy. The great leader who has a clear vision, can stand on stage and motivate people. The only issue is that while we wait for the guru leader to solve our environmental problems and lead us to the promised land of profitability and corporate responsibility, nothing else happens –no one needs to do anything.

In fact, everyone’s activities are interconnected and there are consequences to our collective activity that we may not see. They may be quite distant, or they may not occur for some time but they’re going to accumulate and have an impact that may be far beyond what we each personally do. If individuals and executives adopt the ‘collective’ leadership philosophy we can effect positive change more quickly. As individuals (acting collectively) we can lead this agenda, adopt positive behaviours, buy from ethical companies, and elect conscientious politicians.

Full interviews with the experts quoted in this article and their recommendations for what this means for business schools can be found in the CEMS report ‘Leading for the Future of Our Planet’ at https://cems.org/news-events/news/ leading-future-our-planet

22 Defning environmental challenges | The CEMS Network

Academics working across the boundaries - confict of interest or mutual enrichment?

In contrast to most of their counterparts in the corporate sector, business school academics are often given the opportunity (if not encouraged by some schools) to work beyond the boundaries of their schools, say Patrick De Greve, Nicola Kleyn and Mark Smith

23 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

Accreditation bodies and external advisory boards are often keen to see evidence and preferably impact from consulting and engagement with business and government alike

These arrangements may be with other faculties in home universities, with other (usually non-competing) schools or with external science and education-related entities, and include activities such as research collaborations, teaching and examination engagements and editorships for academic journals. Increasingly, faculty are being offered attractive and sometimes lucrative opportunities to work with corporates and other organisations in a panoply of roles where they are paid to speak, write, promote, educate, train, design, research, advise, consult and serve as board members. There is a high demand for these talents, and they are well compensated.

In some cases, external faculty work may deepen and strengthen the school’s brand name and demand for its offerings. In others, the outcome may not be so rosy. Faculty may lose focus on their home institution, they may monopolise relationships derived through their schoolwork for personal gain, and may even become direct competitors of their business school employer either as individuals or in setting up competing external organisations.

Navigating the tricky terrain of whether, and if so how, faculty should work across boundaries is complex and requires a nuanced understanding of the school’s environment, stakeholders and ethos. We explore the positive and negative effects of external faculty work, how tensions might be resolved and show how one of our schools has contracted with faculty to benefit both the faculty and the school in responding to external opportunities.

The upside

For faculty, extra-organisational work has been regarded as a source of freedom, an opportunity to enrich and legitimise an academic profile, and in the case of paid work, an attractive opportunity to augment faculty earnings. Extraorganisational teaching can bring benefits to both schools and their faculty including prestige, access to new networks and opportunities to learn about different contexts including technological and physical infrastructures, and ways of working in classrooms.

Accreditation bodies and external advisory boards are often keen to see evidence and preferably impact from consulting and engagement with business and government alike. Such work can also be used to supplement growing calls on the academy to provide evidence of impact on public policy and practice. This exposure to other organisations can enrich much of the offering in the classroom for MBA students and other executives. The diversity of experiences with practice complements academic training and can provide legitimacy for faculty who engage with highly experienced students. Furthermore, there is a certain prestige for the business school in being able to record evidence of consulting and advisory work for leading blue-chip companies.

24 Academics working across the boundaries - conflict of interest or mutual enrichment? | Patrick De Greve, Nicola Kleyn and Mark Smith

Engagement with practice also provides schools with an opportunity to augment linear academic trajectories that rely solely on an intense focus on research and publications. This can provide opportunities to attract strong practitioners as teaching faculty and to provide alternative options to career academics who may wish to lessen their focus on scholarly research.

There’s also an argument to be made that as many business schools preach and teach about the importance of entrepreneurship, faculty members who thrive from participating in entrepreneurial activities like start-ups, scale ups, board mandates and PE involvement showcase their expertise in action. ‘Walking the talk’ can enable them to have more impact in teaching, act as a role model and be inspirational for the next generation of talents. Of course, for the faculty member themselves, the income models (share allocations and options, incentive plans, free agent fees, sign up bonuses) that come with these assignments are even more lucrative than billing by the hour and serve as a stark reminder that maybe it’s time for business schools to rethink their standard rewards systems.

The downside

What’s good for faculty may not necessarily be in the interest of the business schools that home these permanent academics. Business education is expensive and supporting research and other activities that do not bring direct income streams have made schools and their deans more attentive to what they expect from faculty. A new breed of academic managers with new perspectives and pressures are paying greater attention to the management of academic resources and questioning the wisdom of traditional norms. They face renewed pressure to align the skills and talents of their faculty with opportunities to build income and brand equity and to manage these across new modes of delivery. Part of their focus is to scrutinise potential conflicts of interest, particularly in the arenas of executive education and consulting, which are growing areas and a valuable source of income for many schools.

Unlike members of a true gig economy, permanent faculty who leverage market opportunities do so from guaranteed and secure positions at their alma mater. They can price their services at marginal cost with no repayment to the institution (or the citizenry that might fund these in the case of public institutions) for investments made over the career of the faculty member. Not only have their institutions invested in their skills and knowledge; they have often funded the development of teaching materials and other intellectual property that is not theirs to sell on.

From a client perspective many large corporations, corporate universities, L&D departments, etc., are well structured and master their needs in such a way that they have the maturity to cherry pick their faculty of choice and design impactful programmes around them, coordinating and facilitating the entire learning journey. In using the faculty member’s title and

25 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

affiliation, they benefit both from the brand of the business school and the capabilities of the professor while the home school gains little beyond lost executive education revenue opportunities.

Whilst deans and professional managers might bemoan the behaviour of their faculty, they complicate matters by using temporary teachers and short-term contracts. These provide built-in flexibility and capacity for core teaching activities, sometimes at the cost of precariousness for the individuals involved. While these teachers may deliver a large proportion of total hours on the key ‘product’ of the school they may not be loyal. However, using ‘fly-in’ faculty might bring fresh perspectives that benefit the school and its faculty community. All too often though, there’s little opportunity or incentive for such faculty to spend time building relationships

that would ensure alignment with a school’s brand, sustained engagement with students and a chance to imbibe the culture of their host school. And why should they? They have other engagements to fulfil, which in many cases might be to teach at competitor schools. The growing demand for online materials further complicates the situation. In many cases, there is nothing that prevents faculty from recording courses for other schools (perhaps even from their home offices) which can then be branded and resold, over and over.

The pressures and paths that have led to our current situation are unlikely to recede. What is needed now are new ways of doing things that tackle the tension and keep both the ‘good money’ and talented faculty members in our schools.

26

Academics working across the boundaries - conflict of interest or mutual enrichment? | Patrick De Greve, Nicola Kleyn and Mark Smith

A different way - Vlerick’s academic partners

When designing its faculty model Vlerick Business School differentiated between individual career builders and institution builders and created differential incentive systems, career paths and expectations towards them. Some faculty benefit from a more traditional model. For those who are entrepreneurial and seek to grow in partnership with Vlerick, a new faculty model, the Academic or PURE PLAY Partnership was created. The relationship is characterised by a strong “psychological contract” as of the level of associate professor for those faculty that subscribe to the institutional agenda, the strategy, the ambition and who want to commit the full 100%. Faculty members who have top talents and have built a trusted relationship are provided with, and generate opportunities to teach, research and provide service within the school.

The academic partnership offers faculty significant entrepreneurship, freedom, and autonomy to be fully engaged in the school’s agenda avoiding the temptation for them to be “seduced” by outside activities. In return, the school pays a premium to these faculty and has invested in elaborate reporting systems, feedback and evaluation processes to monitor and report on the multiple dimensions of the job to be done. The academic partner evaluation system is perhaps the magic formula to make it all happen and make them ‘hunt as a pack’ (to quote the McKinsey saying). Vlerick took learnings from incentive systems in the corporate and consulting worlds to design a model that allows the money from all activities the academic partners undertake to stay in the school. All renumeration first comes into the school, it is jointly used to make progress on our ambition and strategic agenda and if the school does well it can/could be distributed in second order.

The academic partnership rationale is one of pure play and is based upon four strong foundations: a business and entrepreneurship focus, a deep-rooted psychological contract and strong commitment towards the

institution, an aligned human resource strategy and policy focusing on partner development and feedback and finally, one that is backed by a solid legal, social security and engagement contract. Full disclosure of all activities and full transparency is key to making it work.

Vlerick has found that the partnership model enables unity in diversity, as it allows faculty with very different profiles (from research-focused to teaching focused) to be equal partners in building the school.

Vlerick still has its other career track, the pure academic path (assistant, associate, full professor) where these talents focus more on individual careers. The School allows these faculty to spend one day a week outside the school. Ideally, they seek to buy off this day (so-called overload teaching or overload in research) so that faculty spend it at ‘home’. ‘Because if they are great, relevant, on the edge, why would we want them to do their gig somewhere else?’

In a world with a shortage of academics business schools may need to ensure their teaching talent is fully utilised at home before sharing it with others

27 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

Resolving the dilemma

Left unchecked, the growing number of outside opportunities will challenge the job security, autonomy and flexibility that are hallmarks of being a faculty member in a tenured position. It is folly for faculty to ignore the lure of the external. So too is seeking to treat faculty as corporate employees and prohibiting all external engagements. Schools need to find a middle road that is likely to involve overhauling incentive and performance systems and processes along with legal and psychological contracts with faculty.

In a world with a shortage of academics business schools may need to ensure their teaching talent is fully utilised at home before sharing it with others. Inculcating this principle in both regulations and culture could prevent undesirable situations. An example of which involved a faculty member who avoided fulfilling obligations within their home business school, citing overwork, but who was then found to be spending days teaching elsewhere in the same university. Another situation involved two faculty members who set up a private executive education business, whereby they were paid dividends (the disclosure of which was not required) and which did not conflict with faculty limitations on earnings.

For some schools, a Vlerick-like option is feasible. For others, particularly public universities where salaries may be highly regulated if not capped, other solutions need to be found. As schools, we need to ask questions of ourselves. How innovative and entrepreneurial do we want to be? Do we have the courage and the energy to design appropriate social and financial incentives alongside tracking and monitoring systems that disincentivise behaviour which hurts our institutions? The first step is to acknowledge and understand the problem and to share it within our communities so that we can find win-win defensible solutions that balance the needs of faculty, schools, funders, and clients.

Patrick

Nicola Kleyn is a Professor of Corporate Marketing at the Department of Marketing, Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University (RSM).

Mark Smith is Director and a Professor at Stellenbosch Business School, Stellenbosch University.

28

Academics working across the boundaries - conflict of interest or mutual enrichment? | Patrick De Greve, Nicola Kleyn and Mark Smith

About the Authors

De Greve is Director General of Vlerick Business School.

An Emerging Market Perspective on the Internationalisation of Business Schools

This reflection on internationalisation is provided by Wafah El Garah, Piet Naude and Michael Osbaldeston who have gained significant experience in emerging market contexts, strengthened by participating in the EFMD Deans Across Frontiers (EDAF) programme which deliberately focuses on developing countries in, for example, Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Many schools from these regions are committed to internationalisation but face both barriers and opportunities not always appreciated by those from economies where resources and infrastructure are more readily available

29 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

The issues faced by employers are increasingly global. Companies and NGOs are being progressively organised internationally with a global focus

Recent developments in internationalisation

The internationalisation of higher education has achieved greater prominence in recent years due to a combination of factors:

The issues faced by employers are increasingly global. Companies and NGOs are being progressively organised internationally with a global focus. Students have increasingly been taking an international perspective when deciding where to study, often deliberately choosing to go abroad to widen their learning experience. Emerging market schools often operate in contexts where global issues such as climate change, geopolitics, poverty, inequality and radicalisation are present in concentrated form.

In business schools, strategies for internationalisation have generally focused on structural issues such as international research and publications, student and faculty diversity, international partners and networks, and international corporate connections.

Yet there is a strong argument for rebalancing attention towards processes that are more outcome-related, with greater focus on the development of international relevance and impact.

So, what is meant by ‘internationalisation’ in a management education context, and how best can it be assessed, is an increasingly complex question.

30 An Emerging Market Perspective on the Internationalisation of Business Schools | Wafah El Garah, Piet Naude and Michael Osbaldeston

EFMD Quality Services has developed a model which encourages thinking beyond nationality mix

What is understood by “internationalisation”?

Internationalisation has generally been perceived as being reflected in the mix of nationalities among students and faculty, together with advisory board members, partner schools and recruiting organisations.

While a school’s cultural diversity, measured by nationality, is important, a much deeper understanding of internationalisation results from an assessment of how a school has adapted its education and research to an increasingly global managerial world; how a school responds to unexpected international shocks such as the global pandemic; and how a school has incorporated recent developments in information technology (see below) into its learning methodologies.

Deeper evidence of the degree of internationalisation can be reflected in research that explores international challenges, education that embraces an international curriculum and is accessible across the world, and exposure that encourages international mobility and employment. The growth of joint programmes, the dissemination of online learning, the establishment of satellite campuses, increasing institutional collaboration and partnerships, and the emergence of cross-cultural mergers and other forms of restructuring are all part of this complex and multi-faceted concept.

The EFMD guiding model for internationalisation

To assist academic leaders in understanding the degree of internationalisation of a business school, the EFMD Quality Services has developed a model which encourages thinking beyond nationality mix, incorporates recognition of the local (emerging market) context and is founded on a deep respect for diversity, including cultural and education system differences. It integrates a wide range of international measures, grouped into four broad categories:

• Policy issues influencing the development of the whole school (e.g., strategy, reputation, governance)

• Content aspects of the learning and development process (e.g., curriculum, learning resources, research and development, skills and competencies, languages)

• Context issues resulting from the background experience of the various stakeholders (e.g., faculty, visiting professors, students, exchanges, alumni, professional staff)

• Elements of the wider Network in which the school participates (e.g., executive education, clients, recruiters, partners, alliances, satellite campuses, joint programmes, franchising)

31 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

This model has been adopted by EFMD Quality Services to underpin the international element of all its quality assessment (EQUIS and EFMD Programme Accreditation) and development systems (EFMD Deans Across Frontiers).

While this more inclusive interpretation of internationalisation has been generally welcomed by member schools across the world, there continue to be pressures to further refine standards, incorporate new areas of assessment and anticipate developments in global management education; none more so than in the context of the current turbulent business environment and the rapid development of schools in emerging economies.

Opportunities that technology brings for schools in emerging markets

Information technology has proven to be a driving force for internationalisation. It is an effective tool to support and coordinate international activities, especially for schools in emerging markets.

Business schools across the globe are leveraging information technology to enhance their internationalisation through reaching out to students, faculty, and researchers internationally. Although the integration of IT in higher education in developing countries has been slow, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated its adoption especially in teaching and learning. The forced shift to remote learning by the pandemic has presented several challenges to schools in these countries, such as inadequate IT infrastructure. It has also provided opportunities for new connections and digital partnerships both locally and internationally.

Schools in developing countries are increasingly using IT to overcome several obstacles that hinder internationalisation activities, such as the cost of student and faculty mobility, political conditions, health circumstances associated with visa restriction, and cultural and social issues, among others.

32

An Emerging Market Perspective on the Internationalisation of Business Schools | Wafah El Garah, Piet Naude and Michael

Osbaldeston

IT can enable internationalisation in different practical ways. For instance, virtual exchanges are becoming an acceptable teaching and learning practice where students of different backgrounds and geographic locations connect through information technology platforms and work together on academic projects supervised by their professors. Through virtual exchanges, learners can gain meaningful intercultural experience as well as learn how to use digital technology efficiently, which are skills required for employment in the 21st century.

Virtual visiting scholars is a recent trend in internationalisation that many schools are adopting today which aims at strengthening international collaborative research. Through international virtual visiting scholar programmes, professors from different universities can collaborate on research projects across borders using online collaboration tools without the need for costly and time-consuming travel.

Schools are increasingly open to creating these positions to help bring international expertise to their campuses, expand their resources, and further enrich their educational programmes. Additionally, schools in developed countries, as part of their social responsibility, can share their online faculty development workshops with online visiting faculty, hence contributing to their growth.

Virtual international guest speakers are also another recent initiative that schools are adopting to enhance the international learning dimension within the classroom. Inviting international speakers virtually helps deal with several difficulties inherent in arranging faceto-face guest speakers such as travel distance, availability and cost.

In today's global society, all business schools must prioritise developing global citizens. It is evident that the advances in information technology and digitalization provide a real opportunity for schools in emerging markets to connect, share resources across borders, and develop digital partnerships and ecosystems.

Ethical questions related to internationalisation in emerging markets

Internationalisation of management education for schools from emerging economies raises both “internal” and “external” ethical questions.

From an “internal” perspective, there is a moral obligation on schools to provide students with a good local grounding, but also – as stated above - with vital global perspectives on business and leadership.

This requires more than a well-sounding vision to be “globally recognised” or “internationally competitive.” Very specific objectives need to be set that are both taking contextual realities (visa restrictions, currency volatility, geographical isolation, social instability) into account and also striving to creatively transcend “barriers” to an international learning experience, such as the examples from technology cited above.

33 EFMD Global Focus_Iss.1 Vol.17 www.globalfocusmagazine.com

The latter may include investment in appropriate virtual learning technologies; shortterm assignments for visiting international faculty; programme content that relishes context but also reorients globally; affordable exchange opportunities coupled with internationalisationat-home experiences; and transnational research cooperation in the form of publications, position papers, and conferences.

Too few schools from the Global South realise that their apparent “difference” to developed economy schools is in fact an opportunity. Attractive combinations of academic, corporate and cultural activities lead to increasing interest from incoming student groups who are required to spend a portion of their studies in non-national territories.

From an “external” perspective, one may note three ethical issues:

First, the requirement for contextual fairness in assessing the internationalisation of emerging market schools. Schools – like for example those in the EFMD Deans Across Frontiers (EDAF) programme – often operate under trying geographical, financial, social, and (sometimes) political conditions. These often rule out any “easy” idea of activities normally associated with internationalisation. It makes no sense to judge a school negatively due to low incoming/ outgoing student numbers if visa policies lie outside its control. As a case in point, incoming student groups from developed countries recently cancelled a visit to South Africa due to a limited Ebola outbreak in West Africa, about 4,500km away.

Second, the social responsibility of wellresourced schools from developed countries to deliberately pursue cooperation with schools from emerging economies. This co-operation should fulfil the norms of reciprocal respect for autonomy (especially in a power-asymmetry) in determining the agenda, and the norm of mutual benefit via increased interaction.

Third, the requirement to resist and overcome a colonial mind-set along the discriminatory axes of centre/periphery, universal/local, normative/ deviation, intellectually superior/inferior and so forth. Working, for example, with EDAF schools, and operating ourselves for many years under challenging circumstances, we have persistently seen the error of under-estimation of local wisdom and the joy of fulfilling high internationalisation ambitions.

Enhancing multi-lateral management education

There are concerning signs of unilateral and nationalistic populism around the world, undermining the belief that multilateral relations can bring benefits to all. By enhancing the vision for truly inclusive internationalisation, business schools in fact contribute to a major social good on a global scale.

About the Authors

Wafa El Garah is Professor of Information Systems, EFMD Fellow, former Vice President and former Dean, Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, Morocco.

Piet Naude is the immediate past Director and Professor of Ethics at University of Stellenbosch Business School, South Africa, and Director of the EFMD Deans Across Frontiers (EDAF) programme.

Michael Osbaldeston is Emeritus Professor at Cranfield University School Of Management, UK and a Former Director of Quality Services, EFMD, Belgium.