11 minute read

Nur’aishah Shafiq The Apostate

from Airport Road 11

The Apostate

Nur’aishah Shafiq

ENDING ... There are great gashes in the world that we love with so much pain. —Muriel Rukeyser

The room went utterly silent, save for the scratch of pen on paper and the incessant tap-tap-tap of typing. Words hung suspended in the air, formless without voice. The suspense was straight out of a film confrontation; you could practically see the camera panning the set, cutting from one impassive face to the next before zeroing on a young girl in the background, her wide eyes marring the tableau of otherwise perfect composure. I would’ve savored the drama if I weren’t so disappointed at being part of the scene.

The instigator settled back in his chair, replete at a job well done. Still, no one spoke. I almost chewed through my cheek to stop myself from laughing hysterically, a reaction that would’ve shattered the unspoken protocol of the meeting. And we couldn’t have that. Decorum is everything at the United Nations.

The silence persisted for enough time to signal an appropriate level of disapproval, before the facilitator noted down the offending statement for further deliberation. Deliberate when, you ask? Probably in future negotiations the planet cannot afford. I looked around, even then waiting for someone’s interjection, an exclamation of outrage perhaps towards the words of the Russian delegate—that we shouldn’t consider human rights and gender when implementing the Paris Agreement. Apparently, the wellbeing of people, especially women, was an inappropriate point to

aise when discussing how best to avert, address and minimize the loss and damage associated with impacts of climate change.

The words were a weapon well-wielded, but only because the silence meant no one had thrown themselves forward to obstruct the bullet’s flight. Instead, an entire room of people who claimed to care about the welfare of our planet and its inhabitants acquiesced to the violence at hand. I had come to partake in the fervour of climate action, but rather found myself a collaborator in the killing of our commitment to democracy and equality, for I too stayed silent. Wordlessly, I helped bury the remnants of a just political system, riddled with wounds, rendering environmentalism just another fever dream of the egalitarian spirit.

And thus, my faith was broken.

It had been breaking for some time. In the weeks preceding my excursion as a youth delegate to COP25, the 2019 UN conference on climate change, I moved through time in the torpor of disillusionment. The absence of fanaticism on my part for this ‘opportunity’ was a sacrilege even I did not yet care to acknowledge. But I had grown weary trying to compel others to care, to give a damn for once about the state of our world and the fragility of our future. Worse still, I was tired from constantly questioning my actions, from the dread that I was doing it all wrong. Every effort abided by the scripture of contemporary environmentalism, and yet I saw so little fruit borne from my work.

I mobilized students in sustainability initiatives, facilitated environmental education and awareness. I organized events and attended conference upon conference in order to help my fellow peers learn how the environmental crisis was being politically addressed. And yet, those who didn’t care still preached their ignorance about how the ways we ate,

moved, bought, consumed, lived was threatening humanity’s continued existence on Earth. Was exploiting countless people and ravaging nature in order to uphold our lifestyles. Those who did care remained largely apathetic to the possibility of change, experiencing disempowerment about their perceived smallness within the largeness of our problems. It was this latter group that hurt my conviction the most. I remember two of the most environmentally-conscious people I know confide that they’ve given up caring about how flying on holidays spewed carbon into the sky; they’d rather travel and experience all there is to life before it’s gone then “waste” their chances to “live” on actions that didn’t even make a difference.

And so on the brink of my pilgrimage to Madrid, where thousands of environmentalists would gather to deliberate implementing the Paris Agreement, I wavered—my devotion to that great religion was not what it once was, when I was first converted to it in high school and initiated in its ways upon entering college. For so long, I believed in the capacity of top-down mechanisms such as that of the UN to bring about the large-scale radical transformations that we so clearly need. I fostered my activism in the opportunity to attend COP whilst still at university, thinking that I would be one step closer to influencing the decisions that really mattered in facing climate change. To break the Machine that burns fossil fuels with abandon, that prioritises economic growth over the sanctity of human life, that treats the planet as cannon fodder for the progress of our civilisation.

Before Spain, I had been so caught up in the doing doing doing, I failed to see that the cause to which I was a devout follower was a religion of the Machine. I wanted to believe that the political elite would drive actions that reversed the harm we had done the natural world and its countless denizens. Because they had more power than I did, had been in this

game longer, and knew what they were doing while I was just a rookie, a mere acolyte. So when I got to that negotiation hall, when I heard the Russian delegate disregard that foundational ideal of equality—that all are deserving of human rights—when all this happened, I stayed silent. I stayed silent because everyone else did too. I cooled the rage that burned within me to join that tableau of perfect stone seen in everyone else’s reactions.

I was and still am ashamed at my complicity. My one consolation is that in the silence I found revelation. How can an environmentalism that rubs shoulders with the powerful ever heal the gashes that such power leads to in the first place? We invest in the political game, in climate treaties, and inter-government collaboration, seduced by promises of ‘meaningful change.’ We want so badly to believe that strategies like carbon trading and renewable energy are the answers to our problems, because they’ll preserve our current way of life and all its conveniences. All we need to do is substitute one resource for another—oil for sunlight, plastic for biodegradables—and monetize carbon to let the free market work its infallible magic. This way, we can still have our development, since such changes render it ‘sustainable’.

In donning shiny suit-and-tie ensembles appropriate for corporate settings, we shed our mantle of eco-warrior to become merely cogs colluding in the machinations of our alienating system, one that abides by a single principle—grow alone or die together. You can claim that environmentalism is completely different than the engines of economic growth, that it cares for the environment in a way the Machine does not. Well. Tell me then, how does environmentalism perceive the Earth?

From above. As if humans are separate from nature, as if nature is there for us to experience, for us to save. Yes, unlike the engineers of the

Machine, we are not lords bearing dominion over lesser beings. But we environmentalists figure ourselves nature’s saviour, its steward, which of course is predicated on the conviction that first we are its destroyer, and it is in need of our protection. Did there ever exist a race more arrogant? We need the natural world, this planet of ours, in a way it has never needed us. The myth of our own self-importance is one we’re resistant in facing, a myth exemplified by us naming this historical period the Anthropocene— the age of human influence.

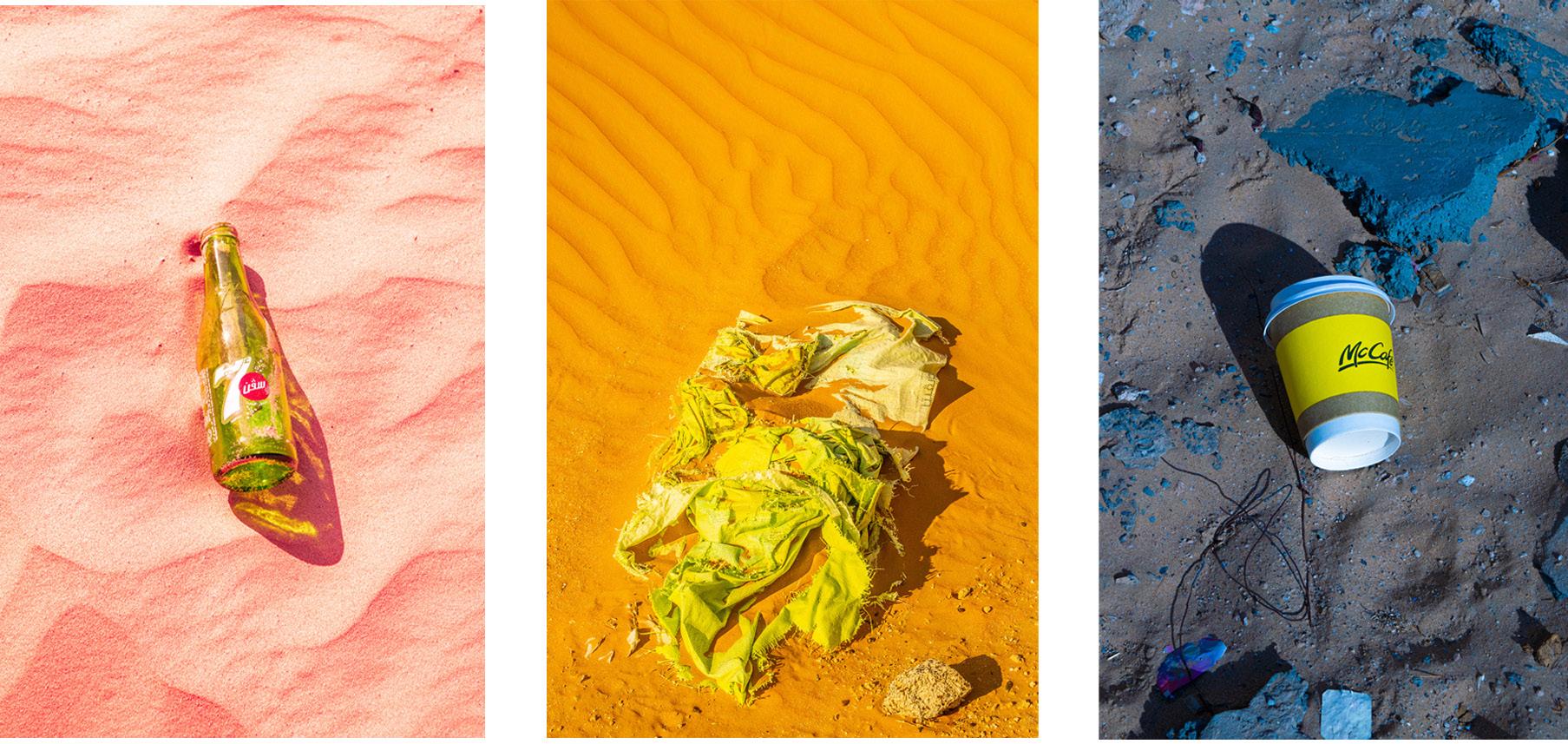

What if we are never able to escape our own myth? The atmosphere continues to warm, the seas expanding in their effort to kiss the sky. Our years on this Earth grow shorter. And yet, narratives perpetuated by both environmentalist and plutocrat marry the human race to a future that cannot exist, one where we preserve the values that underlie environmental degradation and socio-economic injustices. Values that claim we are free to sacrifice each other and the planet’s wealth without consequence, for the sole purpose of our own comfort and pleasure.

Do you see then, the end towards which we run? When all that is left of us are the peaks of ivory towers, once the oceans finish their work of drowning and the air blazes with the sun’s fury.

... IS BEGINNING we are all compost, not posthuman. —Donna Haraway

The future however, is not here yet. And until it arrives, we must act on even the slimmest chance that we have within us an ability to still affect what shape the future will take.

But how to act, I asked myself, when so much of what I knew fell through the cracks in my conviction. I had been an arrow once, in my singleminded commitment towards environmentalism. But an arrow is still a weapon and the world needs more than violence. That of words, of silence. And most of all, the violence at the heart of the Machine—the violence of lovelessness, that commitment towards individual interests over the welfare of all others.

How, you ask, does one oppose lovelessness? I won’t claim any expertise, but perhaps speaking of my relationship to Aiin can offer something to that end.

Aiin is my sister, born twelve years after me, through whom I have learned intimately the fear that I may never succeed in building a world in which she will always be protected. It’s a primordial being, this fear, settling within me against that other beast, the deep-seated instinct every species possesses for their own eventual extinction.

When I first realised the existential implications of climate change and environmental degradation, I resigned myself to the chance that I might never be a mother. How can I possibly subject another to a life in which the only certainty is the fragility of our existence? To the ease with which our bodies give in to the effects of both words and silence. Nor can I bring myself to subject the world’s existing inhabitants with the burden of supporting yet another life. Despite these considerations, I may never even reach the age wherein I’ll have to act upon them. Such are the circumstances we face.

But in Aiin, I have tasted motherhood; I have touched a shard of this delicate far-off abstract that may never come to be but for this gift in the

present moment, and I have felt the sting of this touch, of knowing that my life is no longer my own. Was it ever though?

We individuals do not live in isolation from the rest of the world. Everything we see around us, everything we experience, everything that we are, is the result of myriad organisms working in tandem with one another. Is the product of innumerable processes, spanning from the chemical and geological laws that shape the Earth, to the human forces of politics and economic organization. From the food we eat and the air we breathe, to the clothes we wear and the environments we inhabit, we belong in a web of webs that interlink with a complexity that lies beyond human comprehension.

What happens however, when a web begins to fray at its threads? Its unravelling unravels the next web and the next, destruction travelling through a chain of connection, multiplying interminably until the entire network of life collapses. This is what is happening now, because we refuse to acknowledge that we aren’t invincible from such breakdown.

We are vulnerable. But there is much strength left to be found. I find mine in Aiin, who taught me the meaning of kinship, to put the needs of others before oneself. These others need not pertain only to those who share our blood, or even our taxonomy. To act on the knowledge that our choices resound through infinite lives, we must first change the way we conceive of ourselves. Rethinking our positionality on this Earth, not as superior creatures that only look down, but as one in greater relation to all with whom we share this planet, human and non-human alike.

Start by telling stories that challenge the myth of our self-importance, until such stories become values ingrained within us, ones upon which we can build a world community based on more than just exploitation

and selfishness. Strive to end the Anthropocene by conceiving an age of kinship, one in which we are bound to all others, in love and by choice.

So Aiin is more than just my sister, more than just the shade of my maybe-child. She is every life, both present and future, to whom I am obligated to try—to try and protect, preserve, build for, heal. For whom I must be accountable for my actions and strive to live in such a way that I do as little harm to those I call my own.

Nothing about this is easy. Indeed, there are already losses we must mourn, as we mourn the death of a family member. Many of these losses we may never come back from. But facing this truth, instead of pretending resurrection is possible, is more productive in envisioning what the future ahead could look like. Nothing of what I have said is new. But the lack of such knowledge manifesting in the practical realities of modern life, in the ways we speak about our place in this world, suggest a need to continue writing of it.

The work at hand, to challenge lovelessness, is a mighty task indeed. We don’t know how much time there is left. But I will not stop trying, even if I am alone, I shall not stop until the certainty of humanity’s fate is sealed with the future’s arrival. Aiin, this I promise you.