23 minute read

The Virtual Circus: A Comparison of Appropriation of The Black Body in 19th & 20th Century Freak Shows and Contemporary Instagram Trends – Tatyana Brown

from Exit 11, Issue 03

The Virtual Circus: A Comparison of Appropriation of The Black Body in 19th & 20th Century Freak Shows and Contemporary Instagram Trends

TATYANA BROWN

Black people have a history in the United States of having their bodies used for white consumption. In the late 19th and early 20th century, Black people were placed on stages and in cages in zoos, and museums. The “freaks” on display at museums, zoos, carnivals, and sideshows can be compartmentalized into five classes: natural freaks, people of determination with physical deformities; self-made freaks, who generate their own curious identity (i.e. tattooed people); novelty act artists, who are noted for their performances rather than their bodies (i.e. fire-eaters); “gaffed freaks,” who use performances to fake physical deformities (i.e. unattached “Siamese Twins”); and non-Western freaks, ethnic people (i.e. “savages” and “cannibals”) who were typically kidnapped from communities of color, often as children, to perpetuate stereotypes of being the lowest humans in the social hierarchy to white crowds for their entertainment.1 The non-Western freaks, and in the case of this paper, specifically those of the Black race, were intentionally advertised to cater to

1 Springhall, John. 2008. “The Freak Show Business: Step Right Up, Folks.” The Genesis of Mass Culture: Show Business Live in America, 1840 to 1940, 37-56

white people’s “voyeuristic interest in the culturally strange, the primitive, the bestial or the exotic,” creating a power dynamic that allows the audience to self-perceive as normal, while making the distinction that the performers were separate, or more accurately, beneath humanity.2 In the past, Black children were kidnapped, placed in cages and on stages, and made to grow up exhibiting their Black bodies so white people may perceive and do with them what they choose. Today, the sentiment behind freak shows is echoed on a virtual stage, where non-Black people, especially those who are white or white passing, not only look at the Black body, but take features of it to attach to themselves for social gain. Social media platforms like Instagram allow for the quick spread of mass culture under the influence of cultural actors, as well as their sometimes institutionally racist biases. The recently popular aesthetic of the “Instagram Baddie”, or “Insta Baddie” for short, is an example of this, as it often entails the display of large lips, dark skin, small waists, wide hips, afrocentric hairstyles like cornrows or laid edges, and Black-American originated fashion aesthetics like long nails and colorful wigs. This aesthetic is used to make people look older, sexier, and more mature, which relates to how people see Black children, especially girls, who naturally have this body type as older than they actually are. This paper will try to connect the larger story of racist history in freakshows to internet trends on Instagram that appropriate Black physicality and show how Black people historically have suffered for it.

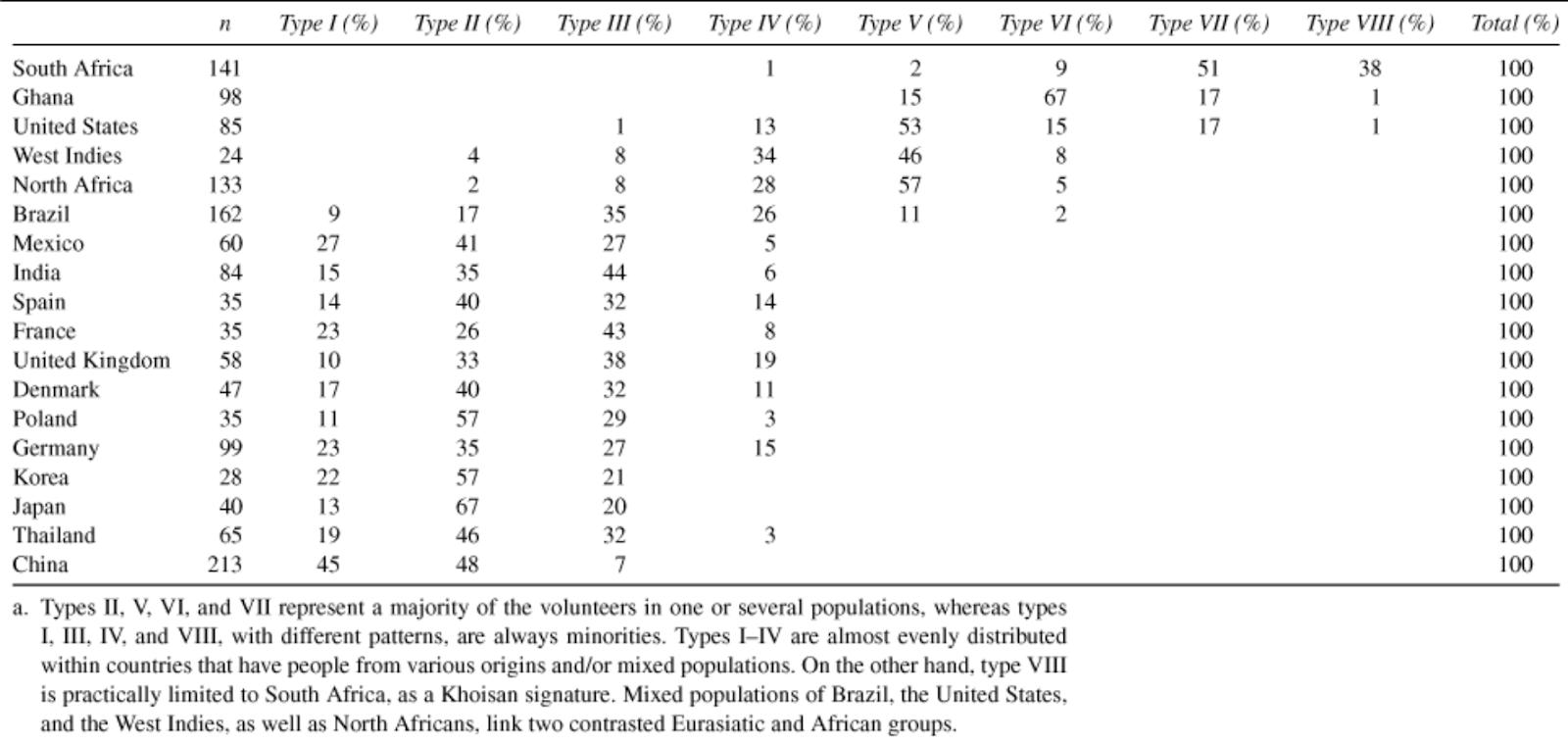

Afro-centric hairstyles are among the most popular of Black body features that non-Black people appropriate or exploit. Black hair tends to be treated like a spectacle, as it stands out when compared to the hair types more commonly presented in races without African ancestry. One human biology study conducted by the National Institute of Health found that of the 8 types of human hair, 4 of them were only prevalent in countries with a large presence of Black people like the West Indies, Ghana, South Africa and the United States (refer to Figure 1).3 Therefore, the afro-centric hair type both encompasses half the range of human hair types and is largely exclusive to the Black race.

2

3 Ibid.

Payne, Joanna. “The ‘Good Hair’ Study Results.” Perception Institute, 2018

While there is variation among the hair types of non-Black races, afro-textured hair tends to be the only to be naturally curly, coily, kinky, or wooly.

Fig.1: The geographical spread of hair types in the Good Hair Study by the National Institute of Health

With the uniqueness of the afro-textured hair types also comes the uniqueness of the hairstyles used to care for them. Afro-textured hair types are often prone to dryness, tangling, and fragility. Historically, styles like cornrows, bantu knots, and twists have been used to protect the moisture, hydration and strength of afro-textured hair.4 Many

other races cannot achieve afrotextured hair unless manipulated to do so, and by extension, their hair does not demand the same care methods as afro-textured hair does. Consequently, non-Black people have little reason to use afro-texture hairstyles for the health of their hair, so their use tends to be for stylistic purposes. If there were not social and political consequences for Black people wearing afro-texture hairstyles in the United States, non-Black people wearing the same hairstyles

4 Allen, Maya. “The Fascinating History of Braids You Never Knew About.” Byrdie, Byrdie, 29 Apr. 2019

would be acceptable, as there would be no power dynamic between them. However, afro-texture hairstyles have a political history in America that does not fare in favor of Black people.

Afro-texture hairstyles are often

criminalized in public American institutions like schools, military, airports, and businesses when worn by Black people. In 1981, Renee Rogers, a Black woman flight attendant employed by American Airlines for 11 years was told that her cornrows violated the company’s grooming policy and she was instead asked to wear her hair in a bun.5 Just 5 years ago, in 2014, the U.S. Pentagon, which oversees the military, lifted its ban on some dreadlocks, cornrows and twisted braids to be worn by female military personnel, revising the original policy that disallowed styles that are “matted and unkempt.”6 In 2018, Andrew Johnson, a Black 16-year-old wrestler in New Jersey, was ordered by a referee to cut off his dreadlocks or forfeit his wrestling match. So, in order to participate, he chose to have them cut, and a white woman came from the sidelines and sloppily chopped them off.7 Black American people like Andrew have a history of making their hair complicit to Eurocentric standards of beauty and professionality to participate in daily life. Much of this comes from non-Black people making laws about grooming and their biases seeping into the institutions they run. In one study, white women, who make up a large majority of female managers in the U.S.,8 were found to demonstrate the highest bias against afro-textured hair, rating it as “less beautiful,” “less sexy/ attractive” and “less professional than smooth hair.”9 The combination of these beliefs and the laws that enforce them leave Black people internalizing

5 Tharps, Johnson. “Library Guides: Title VII’s Application of Grooming Policies and Its Effect on Black Women’s Hair in the Workplace: Rogers v. Am. Airlines, Inc. 6 Henderson, Nia-Malika. “Pentagon Reverses Black Hairstyle Restrictions.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 13 Aug. 2014 7 Blackistone, Kevin B. “Wrestler Being Forced to Cut Dreadlocks Was Manifestation of Decades of Racial Desensitization.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 28 Dec. 2018

8

Elmer, Vickie. “Women in Top Management.” SAGE Business Researcher, 2015 9 Bates, Karen Grigsby. “New Evidence Shows There’s Still Bias Against Black Natural Hair.” NPR, NPR, 6 Feb. 2017

fear of retaliation against their hair, and therefore, fear of being marginalized from basic needs like job acquisition and school attendance. Black women are almost twice as likely to experience social pressure at work to straighten their hair compared to white women.10

At a national scale, Black people are aware that they are often legally, socially and politically defenseless when it comes to their hair; yet, non-Black people are allowed to not only wear the same hairstyles without consequences but also profit socially and financially from doing so.

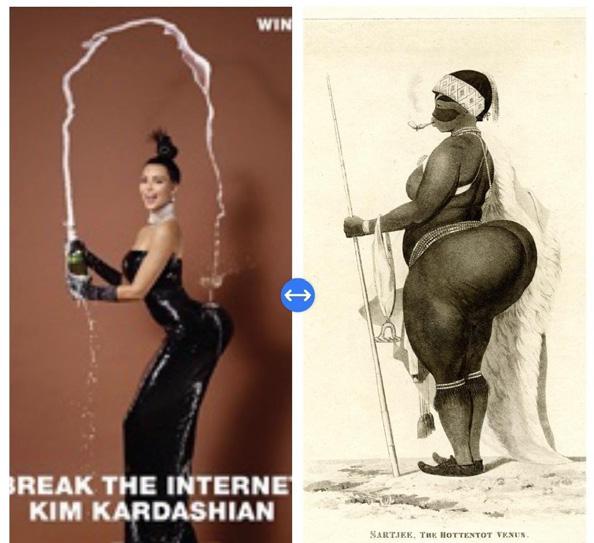

On January 30th, 2018, Kim Kardashian posted an image of herself on Instagram with blonde cornrows stretching down to her shoulders, decorated with a set of 3 beads on each braid. Her caption was “BO WEST”, accrediting the style to Bo Derek, a white female model and actress who appeared in the 1979 film 10 with the same hairstyle.11 There are clear power dynamics here: it took one white actress in a Hollywood film to have a hairstyle renamed after her though it has been worn by Black women since as early as 3500 B.C; and it took one white social media influencer to receive over 2.3 million likes on Instagram for the same hairstyle, except perhaps without beads, that Black people have often had to file lawsuits about to wear in everyday spaces. 12 There is a curiosity and exotification that non-Black people apply to hair textures they

10 Payne, Joanna. “The ‘Good Hair’ Study Results.” Perception Institute, 2018 11 Pham, Jason. StyleCaster. “Kim Kardashian Fires Back at People Accusing Her of Cultural Appropriation over Her Braids.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 30 Jan. 2018 12 Allen, Maya. “The Fascinating History of Braids You Never Knew About.” Byrdie, Byrdie, 29 Apr. 2019

cannot achieve. Kim Kardashian leverages the exotification of afro-textured hair in her advantage, noting herself on Snapchat that she is “really into [her Bo Derek braids],” and implicitly promoting to her audience that they should be too.13 The hairstyle becomes part of her brand, and considering she is the 6th most followed person on Instagram,14 a social media platform used by 1 billion users as of June, 2018,15 the message of appropriation of Black physicality being acceptable reaches far. Using afro-texture hairstyles promotes her in two ways. First, her Eurocentric body features, which are the features already praised by both laws and people for their beauty, allow her to be perceived as beautiful, and a pinch of afro-texture hairstyle pushes her from beautiful to exotic, which may explain why the “Insta Baddie” aesthetic reaches for racial ambiguity, a balance between ideal Afrocentric and Eurocentric features.16 Her cornrows are an accessory to whiteness, if you will. Second, she makes an industry out of making the Black body seem more attainable to those not born with it, pushing non-Black women to wear afro-texture hairstyles, unblurring the mysterious line that separates the Black body from the non-Black body. Though cornrows are not meant for her hair, they are a signifier of afro-textured hair, therefore wearing them gives non-Black people a certain proximity to exotified Blackness, while remaining comfortably within the Eurocentric beauty standard. There is a deeper racist history to the satisfaction non-Black people get from being able to breach the curiosity of the afro-textured hair. The many pictures Kim Kardashian posts in cornrows, her online stage, national attention, non-Black audience, and blatant disregard for the harm it does to Black people has a strong resemblance to the white managers of the Barnum & Bailey circus who put Black people in circuses for white people to see their hair.

13 Pham, Jason. StyleCaster. “Kim Kardashian Fires Back at People Accusing Her of Cultural Appropriation over Her Braids.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 30 Jan. 2018 14 “Top 25 Instagram Influencers in 2019 - The Most Followed Instagrammers (Visualization).” Influencer Marketing Hub, 16 May 2019 15 Carman, Ashley. “Instagram Now Has 1 Billion Users Worldwide.” The Verge, The Verge, 20 June 2018

16 Yancy, George. “Whiteness and the Return of the Black Body.” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy. 2005

Though Kim Kardashian’s domination of Instagram and the Barnum & Bailey Circus’ domination of American entertainment are 100 years apart, they echo each other. While there is no longer a physical stage, Kim Kardashian presents herself on the virtual stage of Instagram, and while it may not physically travel America like the Barnum & Bailey Circus did, it does indeed cross state and international boundaries. Similar to how Instagram is a top form of entertainment today, with users spending 53 minutes per day on average with the app,17 the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey sideshow, also known as “The Big One”, was the top form of entertainment in America in the 1920s and ‘30s.18 Freak shows at the time were a primary source of entertainment, drawing hundreds of thousands of people in some cases.19 This is significant because both platforms carry a social weight, in the sense that they have the authority to influence.

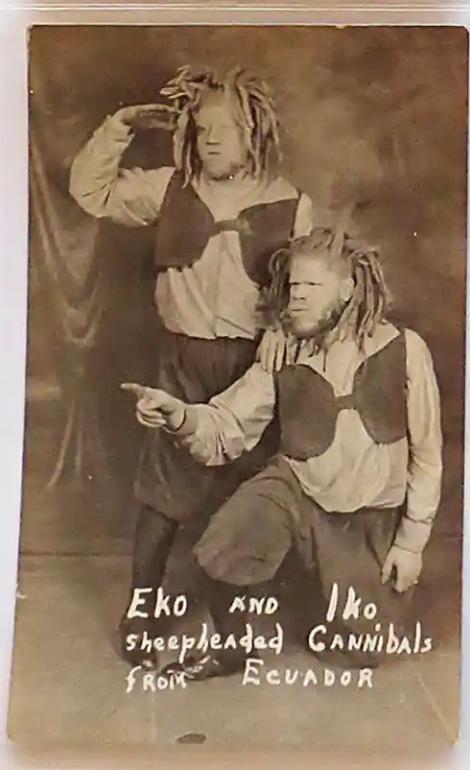

Additionally, both the circus and Kim Kardashian’s Instagram presence confirm Western racial hierarchies by representing people of color in degrading ways to draw and entertain white crowds. In 1899, two boys of the ages of nine and six years old were abducted from their home in Truevine, Virginia, USA to be performers in the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus.20 In the era of eugenics, a science set on improving

17 Molla, Rani, and Kurt Wagner. “People Spend Almost as Much Time on Instagram as They Do on Facebook.” Vox, Vox, 25 June 2018

18 Ferranti, Seth. 2016. “The Horrifying True Story of the Black Brothers Forced to Become Circus Freaks - VICE.” Vice. VICE. October 22, 2016 19 “Human Zoos: America’s Forgotten History of Scientific Racism.” 2019. Youtube. Discovery Science. February 17, 2019 20 Ferranti, Seth. 2016. “The Horrifying True Story of the Black Brothers Forced to Become Circus Freaks - VICE.” Vice. VICE. October 22, 2016

the genetic quality of a human population by excluding the genetic groups judged by white people to be inferior, the Muse brothers were used as an example of what should be genetically removed. The Muse brothers were granted by the circus to be used as a case study in a textbook called You and Heredity, where the author describing their bodies then wrote “by sterilization and birth control we might reduce the proportion of the ‘unfit’, and by stimulating births in other quarters we might increase somewhat the proportion of the ‘fit’.”21 George and Willie Muse were Black albino, with blue eyes, white skin, and kinky blonde dreadlocks, described by You and Heredity as “the odd effect produced by combing out the woolly strands and letting them grow for exhibition purposes.”22 At the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey’s “Greatest Show on Earth” the boys were raised being forced to act as “cannibals” biting heads off chickens and snakes, “ambassadors from mars,” and most notably, sheep-headed “freaks,” in which they were made to run frantically through an obstacle course of sorts and be captured.23 Their kinky hair, which they were told by their manager to grow into dreadlocks, was used to assign them the qualities of being untamed, filthy, and primitive, all of which resemble qualities of animals. In the early twentieth century, the comparison of Black people to animals was common, as anthropology was being established based on the idea of mapping civilizations from highest to the lowest, where the lowest were Africans. These were scientific beliefs, upheld by “leading men of science from Harvard and Princeton and Columbia University [who] were saying that Africans are midway between an orangutan and a human being.”24 This, in turn, validated white people to feel secure as the superior race and therefore justified in doing what they willed with Black people and their bodies. Kim Kardashian’s Instagram post of her in cornrows works in a similar manner as it delivers the idea that white people are allowed to use Black body parts for their own consumption.

21 Scheinfeld, Amram. You and Heredity; Assisted in the Genetic Sections by Morton D. Schweitzer. JB Lippincott Co, 1939 22 Ibid.

23 Jeffries, Stuart. “American Freakshow: the Extraordinary Tale of Truevine’s Muse Brothers.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 Mar. 2017 24 “Human Zoos: America’s Forgotten History of Scientific Racism.” 2019. Youtube. Discovery Science. February 17, 2019

The usage of Black people against their will to entertain and satisfy white consumers and validate their curiosities about Black people’s hair is also used as a financial opportunity for entertainment businesses like the Barnum & Bailey Circus and the Kardashian brand. In one image, Kardashian poses with blonde braids flowing down her back, captioning the photo “Futuristic Barbie. They’re here!!! Ultralight Beams are BACK with 3 new shades and 3 classic shade favorites!!! Shop now at KKWBEAUTY.COM.” In this post, she associated her image, in which she wears a traditionally afro-texture hairstyle with the mystifying nature of the future then links it to her makeup products, which have yielded her $350 Million net worth.25 The way she presents herself is used to imply that her consumers can take on the same image, and they do. The recent trend of “Instagram baddie,” largely championed by the Kardashian sisters goes beyond just appropriating Black hair. It also goes as far as encouraging nonBlack people to pursue larger lips, darker skin, wider hips, and the Ghetto Fabulous fashion aesthetic,26 which was created by African Americans. Kim Kardashian’s sister, Kylie Jenner, who has also worn cornrows on her Instagram page, profits off of the enlargement of lips with her product the Kylie Jenner Lip Kit, which recently made Jenner a “self-made” billionaire by 20 years old.27 Kim Kardashian’s other sister, Khloe Kardashian, whose

25 Robehmed, Natalie. “How 20-Year-Old Kylie Jenner Built A $900 Million Fortune In Less Than 3 Years.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 14 May 2019 26 Smith, Danyel. “Ghetto-Fabulous”. The New Yorker. 21 April 1996 27 Robehmed, Natalie. “How 20-Year-Old Kylie Jenner Built A $900 Million Fortune In Less Than 3 Years.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 14 May 2019

for her show Revenge Body, in which she works with other people to achieve their “dream body” while stunting her own, which has a shocking resemblance to the natural body of many Black women: small waist, large breasts, large bottom. The Instagram baddie aesthetic, which heavily relies on Kardashian images and makeup products, has taken over Instagram, with the hashtags #baddie and #baddies combined having over 3 million posts. The Kardashians have created an industry out of the appropriation of the Black body, making it a part of mass culture, especially among young women. Kim, Kylie and Khloe have also all had children with Black men, which is another sign of their interest in the Black body particularly. Similarly, the Barnum & Bailey Circus was incredibly lucrative during its time. In his day, P.T. Barnum was considered a major entrepreneur from his expansion of the idea of the circus. He is still celebrated today for his “innovative ideas” by the 2017 film The Greatest Showman, which grossed $435,000,000 worldwide.29 Some performances, like the singer the “Swedish nightingale” earned him $500,000 in profit.30 During the time of George and Willie Muse, then called Eko and Iko, they were top performers in the circus. People would pay the equivalent of $30 to take pictures with them.31 However, their pay always favored the circus and never them personally. After their abduction, James Herman “Candy” Shelton, acted as their manager “as they toured the US in a series of circuses, using the money they earned to pay for their board, lodging and clothes, but never letting them have their wages.”32 The circus used the money they

28 Friedman, Megan. “Kylie Jenner Says ‘Not a Dime’ of Her Billions Was Inherited.” Harper’s BAZAAR, Harper’s BAZAAR, 21 Mar. 2019 29IMDb, The Greatest Showman. IMDb.com, Inc. 30 Biography Editors. “P.T. Barnum.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 16 Apr. 2019 31 Jeffries, Stuart. “American Freakshow: the Extraordinary Tale of Truevine’s Muse Brothers.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 Mar. 2017 32 Jeffries, Stuart. “American Freakshow: the Extraordinary Tale of Truevine’s Muse Brothers.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 Mar. 2017

gained only to keep the brothers’ performance in motion and maintain the overall profit of the circus. Though George and Willie both had their bodies exploited to entertain white curiosity for 27 years, they still suffered financially while white people gained profit. Lastly, perpetrators of this violence like the Kardashians and the Barnum & Bailey Circus avoid responsibility and pretend that their actions are harmless. The Barnum & Bailey Circus exploited more than just the Muse brothers because they also set the precedent that other Black people were meant to be treated that way. Members of the cast of the Barnum & Bailey Circus were used to justify the genetic separation or disposal of Black people, such as the case of the Muse brothers. Today’s laws and institutions still express ideas about the Black body not having much value and about Black humanity being limited. Though the Barnum & Bailey Circus may not have exclusively created these ideas, it has done work nationally to reinforce them. Newspapers and public writings shared in being desensitized about the exploitation of black bodies in zoos, museums and freakshows. One New York Times article from

1906 wrote about Ota Benga, a Congolese boy kidnapped to be placed in a cage in the St. Louis World’s Fair and, after it ended, the Bronx Zoo. The article downplayed the severity of the treatment Ota Benga received in these facilities: it indicated he was not in a cage, but a “vast room… a sort of balcony in the open air”; it stated that the purpose of giving Ota Benga a monkey was intended to show “a remote parentage between human and animal being”; it describes Ota Benga’s activities as childlike and jolly by saying “[he] swings himself, counts his money, plays with the chimpanzee, fixes his arrow, all the time good-humored, cheerful, happy.”33 Ota Benga killed himself at 27 years old. The reduction of

33 M.s. Gabriel, M.d. “OTA BENGA HAVING A FINE TIME.; A Vistor at the Zoo Finds No Reason for Protests About the Pygmy.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 13 Sept. 1906

his suffering in the explanation to the public is to reduce the need for blame against white people for their actions and to reduce the guilt that white people experience. Similarly, Kylie Jenner’s response to criticism about her wearing cornrows was “mad if I do, mad if I don’t,” which blatantly disregards the harm that her appropriation has on Black people. When criticized for her “Bo Derek Braids” post, Kim Kardashian’s response was “I’ve definitely had my fair share of backlash when I’ve worn braids. I’ve been fortunate to be able to travel around the world and see so many different cultures that have so many different beauty trends.”34 In this response, she victimizes herself by focusing on the backlash she has received and not the ramifications for the Black community, such as continued institutional racism. When these non-Black people who appropriate the Black body were criticized, they had the comfort of knowing their consequences are minimal. This is the same response that has existed throughout the history of American Black body exploitation. John Springhall, author of Genesis of Mass Culture: Show Business Live in America, 1840 to 1940, captures this well:

“Whites in blackface also set off the African American in what would now be seen as a self-evident racist stereotype. Novelist Caryl Phillips has a famous black performer complain: “Everything in goddamn vaudeville is always rush, rush, rush, with the Jews playing the Germans, and the Germans playing the Irish, and the Irish playing the Chinese, and everybody thinking they can play colored because what’s a poor colored man going to do to stop them?”35

The perception of the powerlessness among people of color when exploited by white people is evident. Black people know they are limited in their legal and political defense, and white people know they have the advantage of seeming harmless.

The Kardashian family and the Barnum & Bailey circus echo each other in the way they exploit the Black body. In both contemporary and historic times,

34 Pham, Jason. StyleCaster. “Kim Kardashian Fires Back at People Accusing Her of Cultural Appropriation over Her Braids.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 30 Jan. 2018 35 Springhall, John. 2008. “Blackface Minstrelsy: The First All-American Show.” The Genesis of Mass Culture: Show Business Live in America, 1840 to 1940, 57–80

they have taken advantage of the largest social platforms, confirmed western racial hierarchies, monetized their use of the Black body and assumed they have done no harm in executing it all.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Maya. “The Fascinating History of Braids You Never Knew About.”

Byrdie, Byrdie, 29 Apr. 2019, www.byrdie.com/history-of-braids. Bates, Karen Grigsby. “New Evidence Shows There’s Still Bias Against

Black Natural Hair.” NPR, NPR, 6 Feb. 2017, www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/02/06/512943035/newevidence-shows-theres-still-bias-against-black-natural-hair.

Biography Editors. “P.T. Barnum.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 16 Apr. 2019, www.biography.com/business-figure/pt-barnum. Blackistone, Kevin B. “Wrestler Being Forced to Cut Dreadlocks Was

Manifestation of Decades of Racial Desensitization.” The Washington

Post, WP Company, 28 Dec. 2018, www.washingtonpost.com/sports/wrestler-being-forced-to-cutdreadlocks-was-manifestation-of-decades-of-racial-desens itization/2018/12/27/66f520ba-0a10-11e9-85b6-41c0fe0c5b8f_story. html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.7e8990a379ee. Carman, Ashley. “Instagram Now Has 1 Billion Users Worldwide.” The Verge,

The Verge, 20 June 2018, www.theverge.com/2018/6/20/17484420/instagram-users-onebillion-count.

Elmer, Vickie. “Women in Top Management.” SAGE Business Researcher, 2015, https://businessresearcher.sagepub.com/sbr-1645-955352666211/20150427/women-in-top-management. Ferranti, Seth. 2016. “The Horrifying True Story of the Black Brothers Forced to Become Circus Freaks - VICE.” Vice. VICE. October 22, 2016. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/zn83w4/the-horrifying-truestory-of-the-black-brothers-forced-to-become-circus-freaks.

Friedman, Megan. “Kylie Jenner Says ‘Not a Dime’ of Her Billions Was

Inherited.” Harper’s BAZAAR, Harper’s BAZAAR, 21 Mar. 2019, www.harpersbazaar.com/celebrity/latest/a22117965/kardashian-familynet-worth/.

Henderson, Nia-Malika. “Pentagon Reverses Black Hairstyle Restrictions.”

The Washington Post, WP Company, 13 Aug. 2014, www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/she-the-people/wp/2014/08/13/ pentagon-reverses-black-hairstyle restrictions/?utm_term=.c81c9ab2372e. “Human Zoos: America’s Forgotten History of Scientific Racism.” 2019.

Youtube. Discovery Science. February 17, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nY6Zrol5QEk. IMDb, The Greatest Showman. IMDb.com, Inc.

Jeffries, Stuart. “American Freakshow: the Extraordinary Tale of Truevine’s

Muse Brothers.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 Mar. 2017, www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/15/american-freakshow-theextraordinary-tale-of-ruevines-use-brothers.

M.s. Gabriel, M.d. “OTA BENGA HAVING A FINE TIME.; A Vistor at the Zoo Finds

No Reason for Protests About the Pygmy.” The New York Times, The New

York Times, 13 Sept. 1906, www.nytimes.com/1906/09/13/archives/ota-benga-having-a-fine-time-avistor-at-the-zoo-finds-no-reason.html.

Molla, Rani, and Kurt Wagner. “People Spend Almost as Much Time on

Instagram as They Do on Facebook.” Vox, Vox, 25 June 2018, www.vox.com/2018/6/25/17501224/instagram-facebook-snapchat-timespent-growth-data.

Kopano Ratele. 2005. “Proper Sex, Bodies, Culture and Objectification.”

Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, no. 63: 32–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/4066627. Payne, Joanna. “The ‘Good Hair’ Study Results.” Perception Institute, 2018, https://perception.org/goodhair/results/.

Pham, Jason. StyleCaster. “Kim Kardashian Fires Back at People Accusing Her of Cultural Appropriation over Her Braids.” Business Insider,

Business Insider, 30 Jan. 2018, www.businessinsider.com/kim-kardashian-braids-culturalappropriation-accusations-response-2018-1.

Robehmed, Natalie. “How 20-Year-Old Kylie Jenner Built A $900 Million

Fortune In Less Than 3 Years.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 14 May 2019, www.forbes.com/sites/forbesdigitalcovers/2018/07/11/how20-year-old-kylie-jenner-built-a-900-million-fortune-in-less-than-3years/#183be1d9aa62. Salesa, Damon. “Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus: A Ghost Story and a Biography, by Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully.” Victorian Studies 53, no. 2 (2011): 329-31. https://doi:10.2979/victorianstudies.53.2.329 Springhall, John. 2008. “Blackface Minstrelsy: The First All-American Show.”

The Genesis of Mass Culture: Show Business Live in America, 1840 to 1940, 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230612129_4. Springhall, John. 2008. “The Freak Show Business: Step Right Up, Folks.”

The Genesis of Mass Culture: Show Business Live in America, 1840 to 1940, 37-56. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9780230612129_3. Tharps, Johnson. “Library Guides: Title VII’s Application of Grooming Policies and Its Effect on Black Women’s Hair in the Workplace: Rogers v.

Am. Airlines, Inc., 527 F. Supp. 229 (S.D.N.Y. 1981).” Rogers v. Am. Airlines,

Inc., 527 F. Supp. 229 (S.D.N.Y. 1981) - Title VII’s Application of Grooming Policies and Its Effect on Black Women’s Hair in the Workplace - Library Guides at

University of Missouri Libraries, 2017, https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/c.php?g=593919&p=4124519. “Top 25 Instagram Influencers in 2019 - The Most Followed Instagrammers (Visualization).” Influencer Marketing Hub, 16 May 2019, https://influencermarketinghub.com/top-instagram-influencers-in-2019/. Yancy, George. 2005. “Whiteness and the Return of the Black Body.”

The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 19 (4): 215–41. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25670583?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.