13 minute read

PHOTOGRAPH: The Arabian Dream Mareya Khouri Smelly Sounds – Phonetic Symbolism in Scent – Lachlan Pham

from Exit 11, Issue 03

Smelly Sounds: Phonetic Symbolism in Scent

LACHLAN PHAM

Stinky. Musty. Stench. Dusty. Stale. All these words describe a scent and contain a /st/ consonant cluster. One might also astutely discern the distinctively negative connotation shared amongst these words, perhaps going so far as to associate a sense of subtle yet inescapable displeasure that accompanies exposure to these scents. This correlation between the sounds of a word and its connotation may initially seem purely coincidental. However, it would be unjust and wholly unscientific to dismiss such a relationship based on an intuition. After all, the concept of phonetic symbolism, which refers to the nonarbitrary connection between semantics and speech sounds, is a well-demonstrated phenomenon in several languages including English. Granted, its occurrence is most prominent in – and mainly limited to – lexical fields relating to hearing itself such as onomatopoeia, but the reach of phonetic symbolism has been found to extend into the sense of sight. The same may potentially apply to olfaction until proven otherwise which naturally leads us to the hypothesis:

Individual phonemes of scent words contribute meaningfully to their connotation.

From the outset, the hypothesis for this investigation is perfectly set up for disproof. In applying the oft-inapplicable phenomenon of phonetic symbolism and examining an already tenuous relationship between scent and sound, I was fully prepared to find nothing of statistical significance and, in many regards, this study finds that there is indeed insufficient evidence to support the hypothesis. Nevertheless, any socio-linguistic paper would be incomplete with a merely cursory foray into the immensely multifaceted realm of connotation. Ultimately, connotation relies on a complex amalgamation of context and lived experience and whilst the sounds of scent words may not necessarily share a direct causative link with connotation,

it certainly is one factor among many. This paper will be divided into two discrete sections. The first will resemble a free-form research paper, which attempts to establish a quantifiable relationship between scent words’ phonemes and connotations in English. The second part seeks to justify any findings and contrast them with the French language.

PART 1

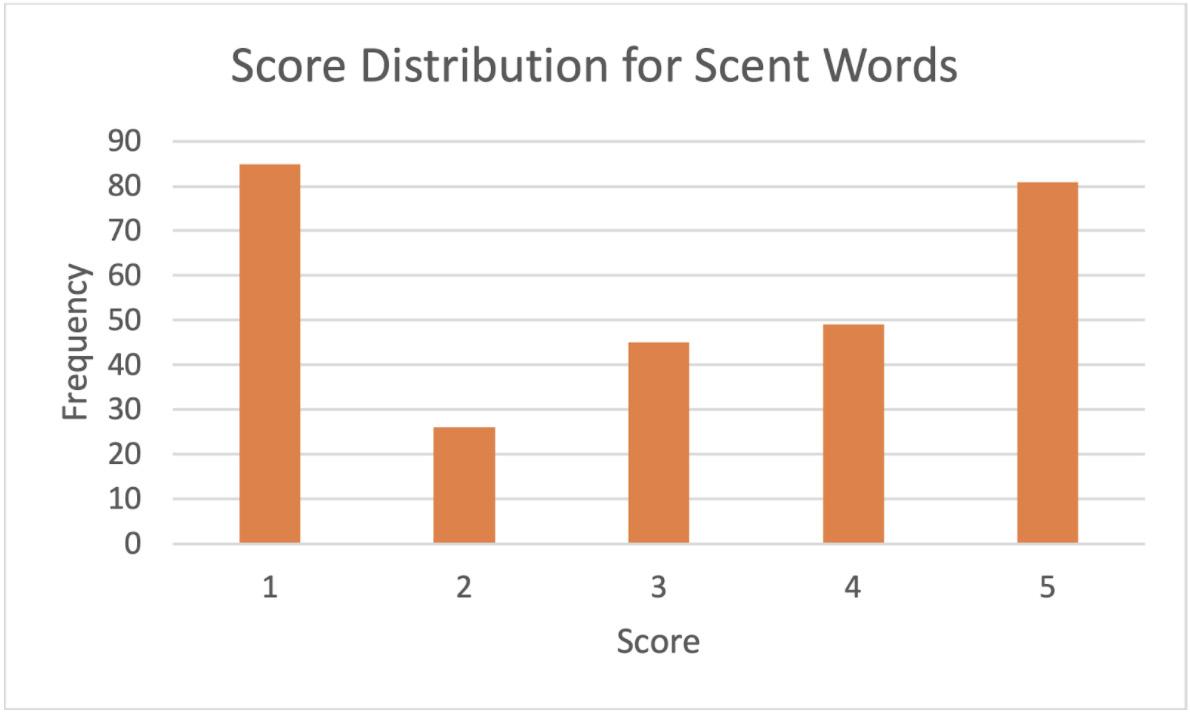

To determine if there is a relationship between the phonemes of scent words and connotation, 287 scent-related words were first collected. These words range from sources of scent (deodorant, skunk) and emotions caused by the act of smelling (intoxicating, nauseating) to likenesses (savoury, floral) and direct descriptions (musky, pungent). The words were subsequently input into a simple program through which a subjective score from 1 to 5 was assigned to the word based on the positivity of its connotation. The scores were given mainly based on SentiWordNet, which is essentially a large online repository of words and their corresponding scores along two spectra: negative-positive and subject-objective (Esuli). The data for the repository is created via a machine learning process in computational linguistics which gathers information about words via association, relying on the assumption that if a word is commonly surrounded by or defined by positive words, it is also a positive word (Esuli). The same applies to the other metrics as well. Importantly, some of the scores sourced from the repository were selectively overwritten as they were subjectively inaccurate – a natural consequence of its indirect and inhuman judgement capacity. The same words were also translated into their individual phonemes according to the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), using another online repository, the Carnegie Mellon Pronouncing Dictionary Corpus Reader (Bird et al); each phoneme was given the same score as its source word. The IPA was selected due to its status as the international standard, making it the most robust open-source transcription library. With this information, a discrete frequency histogram of scores was established for the words:

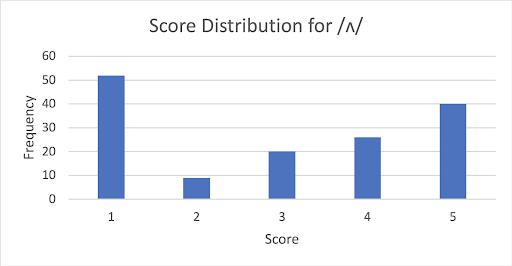

This plot allows us to make a direct comparison with the score distribution for each individual phoneme. If a specific sound does indeed contribute meaningfully to the connotation of scent words, its score distribution is expected to differ appreciably from that of scent words. Conversely, if it shares a similar distribution then the effect of the phoneme on the sound’s meaning, at least along the positivity spectrum, cannot be proven and may as well be random. What the latter situation likely indicates is that the phoneme itself makes no difference to the connotation of the word and thus it should be found proportionally in words of all scores. To compare the above frequency histogram to those of the phonemes, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied, which allows for determination of equality for two one-dimensional probability distributions. For most phonemes, it was found that there was no statistically significant difference for its distribution, essentially confirming the nonrelation between individual phoneme and a word’s meaning; we can be more than 95% certain that the score distribution for a phoneme is not different than the distribution for all scent words. This can be qualitatively demonstrated by the /ʌ/ phoneme, for example:

Evidently, this score distribution strongly resembles the score distribution for scent words, being bimodal, peaking at the extremes score of 1 and 5 and having the fewest 2 scores. Exceptionally, a few phonemes did demonstrate a statistically significant difference in distribution, but these results were disregarded as they were more likely attributable to a low sample size. That is to say, there were several phonemes whose distribution did differ from the distribution of all scent words but this is probably better explained by the few data points available for these phonemes. Additionally, due to the high variance values, using the student’s t-test (which is technically inappropriate for non-normal distributions), no significant difference was found between the mean scores for the phonemes and scent words.

Despite these negative findings, there appeared nevertheless to be minor differences in the average score for the scent words and the phonemes. For example, the mean score for the scent words was 3.05 whereas the mean score for the /s/ phoneme was 2.69. With this, each word was given a ‘sound value’ score which was calculated by summing the difference between each of its phonemes and 3.05. The ‘sound value’ score for the word stink (/stIŋk/): score’stink’ = meanscore(/s/) - 3.05 + meanscore(/t/) - 3.05 +meanscore (/I/)-3.05 +…

This produced a normal distribution of ‘sound value’ scores around an approximately 0 mean. These scores were compared with the originally assigned score for the words and it was found that negatively connoted words (score lower than 3), positively connoted words (score greater than 3) and neutrally connoted words (score of around 3) corresponded at a level of 53% to the sign of its ‘sound value’. This contrasts with an expected

36% if the distribution were merely random and points to the unintended conclusion that it is rather the unequal combination of only slightly positive or negative phonemes which reflects a word’s connotation. In summary, these results show that individual phonemes are not associated with a scent word’s connotation at least along the positive-negative spectrum. This is made evident by the fact that no single phoneme is noticeably overrepresented in positively connoted or negatively connoted words. That said, if we are to consider the sum of the minor deviations of the scores for each phoneme from the average of all scent words, we find that this is a much more reliable predictor to determine the connotation of scent words.

PART 2

As previously noted, the study of phonetic symbolism is rather limited because, by and large, these relationships do not exist in most lexical fields. The reason scent is being considered at all is because it falls into the category of sense where phonetic symbolism has been identified. Onomatopoeia, in a much more literal sense, demonstrates a relationship between meaning and sound, with words like ‘bang’, ‘woof’ and ‘murmur’ evidence of an attempt to imitate sounds with human language. As for sight, the relationship is a little less obvious with seemingly arbitrary sounds demonstrating some identifiable semantic patterns. For example ‘gl-’ is commonly seen in words associated with light and brightness: ‘glare’, ‘glimmer’ and ‘glow’ (Sadowski). Both these phenomena are documented in linguistic literature. On the other hand, there is no literature on the sense of smell despite the identification of some potential patterns. Crucially, this investigation into the phonetic symbolism of scent words provides a preliminary analysis to address this gap in the literature.

However, while it is one thing to identify these patterns as part 1 seeks to do, it is entirely another to justify how they may exist, which is ultimately the intent of part 2. An analysis on the phonetic symbolism in brand names found that the front vowels connoted sharpness as a consequence of its high position in the mouth and shortness (Lowrey et al). This matches the expectations for /ʌ/ and /i/, which had close to average mean scores. These sounds are prominent in several negative biting smells ‘acrid’, ‘acid’

and ‘rancid’. But sharpness is not necessarily negative, it is often related to spices or intense fruity smells, which explains the presence of these vowels in ‘citronella’ and ‘cinnamon’. Conversely, back vowels like /u/ and /ʊ/, which scored more highly are perceived as “smoother, richer and creamier” (Lowrey et al). These sounds, in scent words, are almost always positive as in the terms ‘perfume’, ‘aroma’ and ‘pheromone’. The relatively low-scoring velar nasal /ŋ/ preceding /k/ finds itself in several negatively-connoted ‘stink’, ‘skunk’, ‘rank’ and ‘dank’ reflective of “disgust and dislike” (Lowrey et al). The existence of phonetic symbolism is abundantly clear, but its cause remains ambiguous.

Whilst a class poll confirmed the relationship between the sound of words and their connotations, it also brought into question the causative link. To test whether the identified relationships are a consequence of convenient, cherry-picked examples or if the attributed scores of the phonemes truly reflect, in some manner, the connotation of the scent words, a survey consisting of 9 fabricated lexemes was presented to a class. In this way, one can attempt to verify the connotations of phonemes without confl ating them with the connotations of the words to which they belong. For each made-up word, participants were requested to determine whether they believed the word to be positive, neutral or negative based purely on its sound so that its spelling does not influence the sentiment towards the word. In general, the ‘sound value’ of the word corresponded strongly with the overall sentiment felt towards each word. The ‘gaïac’ (/geIək/) stems from a technical French word for a type of tree and also has a ‘sound value’ of close to 0; six of eleven respondents believed the word to be neutral. Similarly, the word ‘pidous’ (/pidəs/) was composed of the lowest scoring phonemes whereas the word ‘umori’ (/umɔri/), was composed of the highest scoring phonemes; seven respondents found the words negative and positive respectively. However, upon hearing the justifications for their responses, it became clear that, given no context for these words and being exposed to them for the first time, the respondents relied much more heavily on their understanding of similar sounding words rather than assessing the fabrications on their own auditory merits. ‘Pidous’, for example, was compared to ‘penis’ and ‘umori’ to the Japanese term,

‘umami’. These observations show that the experiment ultimately did not succeed in evoking connotation based on sound rather than on already known words, but it leads to a more nuanced conclusion. The very failure of this experiment is indicative of an indirect causal link; the identified correlation may rather come from association with other similar words. That is to say, one manufactures links between connotation and sound as they draw connections between phonemes and the meaning of known words. The intuition that the phonetic symbolism in scent is coincidental stems from this very fact. After all, there seems to be no reason for the sounds of scent words to reflect what the words mean because the processes of developing neologisms and appropriating loanwords are largely independent of phonetics.

The greatest challenge to this investigation’s hypothesis were interviews with three native French speakers from Tunisia, Morocco and Burkina Faso, which emphasised that connotation, more often than not, is independent from sound. Initially, the exploration of French was intended as merely a comparative analysis with the phonetic symbolism of English scent words. Given that English derives much of its vocabulary from French and the two languages share similar roots, the expectation was that there would be valuable comparisons from which to extract a discussion on cultural and linguistic determinism. Instead, and inadvertently, the fact that the native speakers came from wildly varying backgrounds and gave often opposing opinions, reinforced the highly subjective and individualistic nature of connotation. These interviews were simple, involving the oral presentation of several French-related scent words followed by a rapid-fire verbal response consisting of the associative thoughts each individual had about the word. After an explanation of phonetic symbolism, all interviewees felt hesitant to make sweeping generalisations about the sound-meaning relationship. One interviewee would begin identifying a phonetic pattern such as a ‘bodied’ sense to the /ø/ phoneme in voluptueux (voluptuous) and crémeux (creamy) but immediately backtrack, upon considering some exceptions. An interesting observation made was that French speakers place significant emphasis on ease of pronunciation and fluidity of expression. Consequently, words which are more difficult to pronounce i.e. cause greater

strain on facial muscles such as the /g/ and /r/ phonemes in ‘rugueux’ (rough) often had negative connotations. (Importantly, the standard English postalveolar approximant /r/ is distinct from the French guttural uvular fricative /r/, which demands a more strenuous narrowing of the uvula.) This remark is an interesting counterpoint to the indirect causative link in phonetic symbolism; the unpleasant and mildly uncomfortable production of certain sounds can result in negative sentiments. That said, notable among the responses were the ones that relied on a personal explanation. The word ‘terreux’ (earthy) received significantly different opinions amongst the interviewees with one fondly reminded of their childhood games in the rain during the typically dry Burkina Faso climate whilst another recounted their miserable days of trudging through mud. These contrasting attitudes fall strongly in line with the views of Rachel Herz who contends that “our responses to odors are learned, not innate” (202). She states that acquisition of the emotional meaning of smells occurs through experience, citing her enjoyment of skunk smell and another’s distaste for the smell of rose (195). The high variance of opinion toward smell further weakens the link between sound and smell; it is impossible to discover a consistent relationship for phonetic symbolism if the measured variable, connotation, varies significantly from individual to individual. Distilling the influences of connotation into just phonemes is perhaps an interesting thought-experiment but it fails, like any other quantitative metric, to accurately and reliably encapsulate meaning. The investigation has shown that, at the very least, constituting phonemes may be used to predict the connotation of a scent word as negative, neutral or positive at an accuracy of 53%, but this may be a correlative consequence rather than a causative one. Ultimately, the more significant qualities of scent words are a subjective matter, best informed by idiosyncratic experience, context and opinion.

WORKS CITED

Bird, Steven, Ewan Klein, and Edward Loper. Natural Language Processing with

Python: Analyzing Text with the Natural Language Toolkit. O’Reilly Media, Inc, 2009.

Dubois, Danièle. “From Psychophysics to Semiophysics: Categories as Acts of

Meaning.” Speaking of Colors and Odors, edited by Martina Plumacher and Peter

Holz. John Benjamins Publishing, 2007, pp.169–84. Esuli, Andrea. The SentiWordNet Sentiment Lexicon, 2019. https://github.com/aesuli/SentiWordNet.

Herz, Rachel. “I Know What I Like: Understanding Odor Preferences.” The Smell

Culture Reader, edited by Jim Drobnick, Bloomsbury, 2006. Lowrey, Tina M., and L. J. Shrum. “Phonetic Symbolism and Brand Name

Preference.” Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 34, no. 3, pp.406–14. https://doi.org/10.1086/518530. Peterfalvi, Jean-Michel. 1964. “Etude du symbolisme phonétique par l’appariement de mots sans signification à des figures.” L’Année psychologique, vol. 64, no. 2, pp.411–32. https://doi.org/10.3406/psy.1964.27255. Sadowski, Piotr. “The sound as an echo to the sense: The iconicity of English gl-words.” The Motivated Sign, edited by Olga Fischer and Max Nannyohn

Benjamins Publishing, 2001, pp.69-88.