FUTURE ARCHIVES 2225

Eloïse

Landscape

Volume I / Portfolio

Mercer / s2250437 / MLA

Architecture

INDEX

Project Statement

FUTURE ARCHIVES 2225 / The Vatnajökull Botanical Parks - Landscapes of Memory, Ruin, and Resilience 5

PART ONE / ATMOSPHERIC SPECULATIONS

Chapter One

DELIQUESCING / DYNAMIC ATMOSPHERIC SYSTEMS OF THE VATNAJÖKULL 8

PART TWO / ATMOSPHERIC FUTURES

Chapter Two

THE FUTURE RUINS OF THE SAUÐÁRDALUR 34

Chapter Three

THE EXPERIMENTAL FOREST LABORATORIES OF SKAFTAFELL 70

Chapter Four

HIDDEN TRASURES / MICOBIAL ECOLOGIES OF THE GRÍMSVÖTN SUBGLACIAL LAGOON 130

Chapter Five

POSTCARDS FROM THE FUTURE 140

2

3

4

FUTURE ARCHIVES 2225

The Vatnajökull Botanical Parks - Landscapes of Memory, Ruin, and Resilience

‘Future Archives 2225’ proposes the future transformation of the Vatnajökull Glacier – in concert with glacial melt and atmospheric change – into a large-scale Botanical Park comprised of countless ‘archive gardens’. Each site responds uniquely to the notion of archiving, whether through active preservation of its present conditions, through responding to glacial memories, recording landscape change over time, or the implementation of future conditions. This portfolio details the conceptual interventions across three sites in particular, each of which represents a highly atmospherically unique and ecologically valuable landscape, and each of which is under threat from the powerful landscape forces at play as a consequence of large-scale, exponential glacial melt. The man-made reservoir and former wetland landscape of the Sauðárdalur Valley; the birch forests of Skaftafell and the surrounding Skeiðarársandur outwash plain; and the microbial ecologies and hydrology of the Grímsvötn geothermal subglacial caldera.

Whilst the interventions for each site respond individually to contrasting ideas of the archive, they are equally united by a regime of disturbances designed to encourage and sustain life – and landscapes – for future generations to come. United still, by a wider conceptual framework, a sense of materiality and, most essentially, a universal manifesto of ecological preservation and resilience during increasingly uncertain climatic futures. In accordance with a landcape defined by contrasts – the land of ice and fire - The Future Archive for the Vatnajökull Botanical Parks is defined by moments of both stasis and dynamism, by narratives of loss and hope, destruction and life. Far more than a landscape of memory or memorialisation, the Future Archive recognises a great need to preserve the significant cultural histories bound up in the transient ice of the glacier, to transform them into something solid and tangible. It is a landscape of futurality, for the creation of futures that have a future.

‘We do have a future and a past, but the future takes the form of a circle expanding in all direction, and the past is not surpassed but revisited, repeated, surrounded, protected, recombined, reinterpreted and reshuffled’

- Bruno Latour

5

Project Statement

Part One

ATMOSPHERIC SPECULATIONS

6

7

Chapter One

DELIQUESCING / THE DYNAMIC ATMOSPHERIC SYSTEMS OF THE VATNAJÖKULL

8

9

1Eloïse Mercer, “Into the Cyanosphere,” assignment for Landscape architecture design exploration: Part 1, MLA Landscape Architecture (Edinburgh University, 2022).

1Eloïse Mercer, “Into the Cyanosphere,” assignment for Landscape architecture design exploration: Part 1, MLA Landscape Architecture (Edinburgh University, 2022).

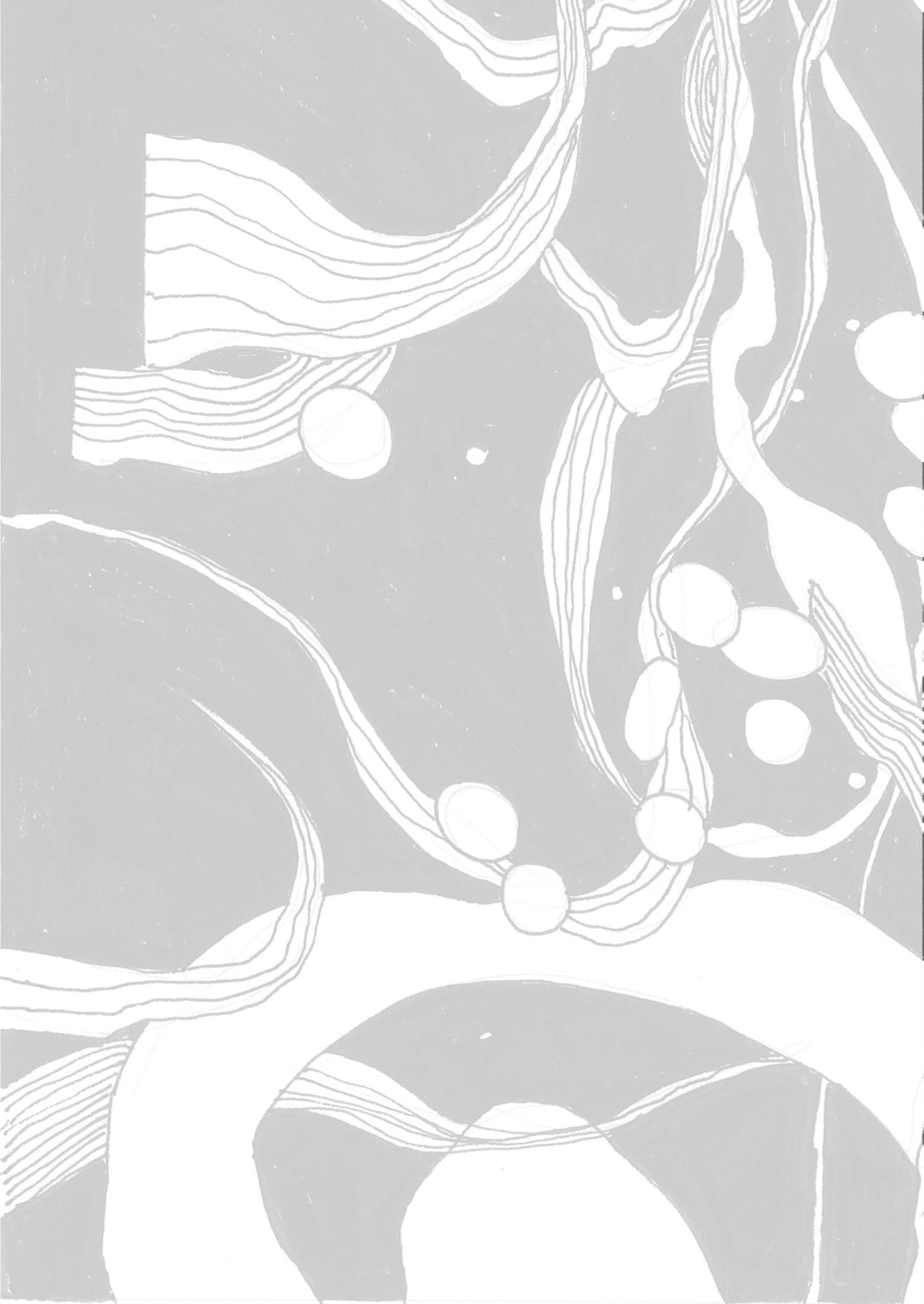

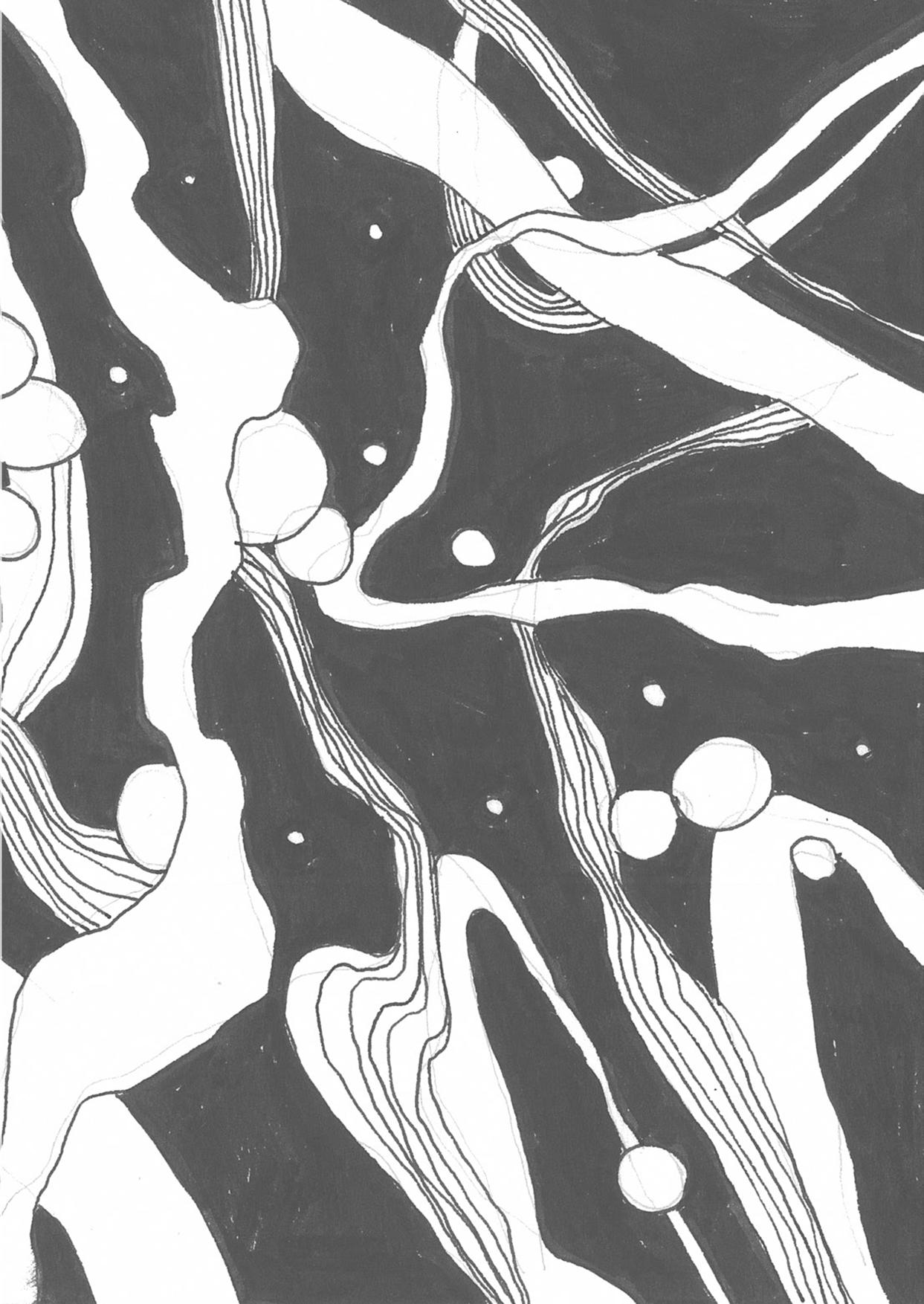

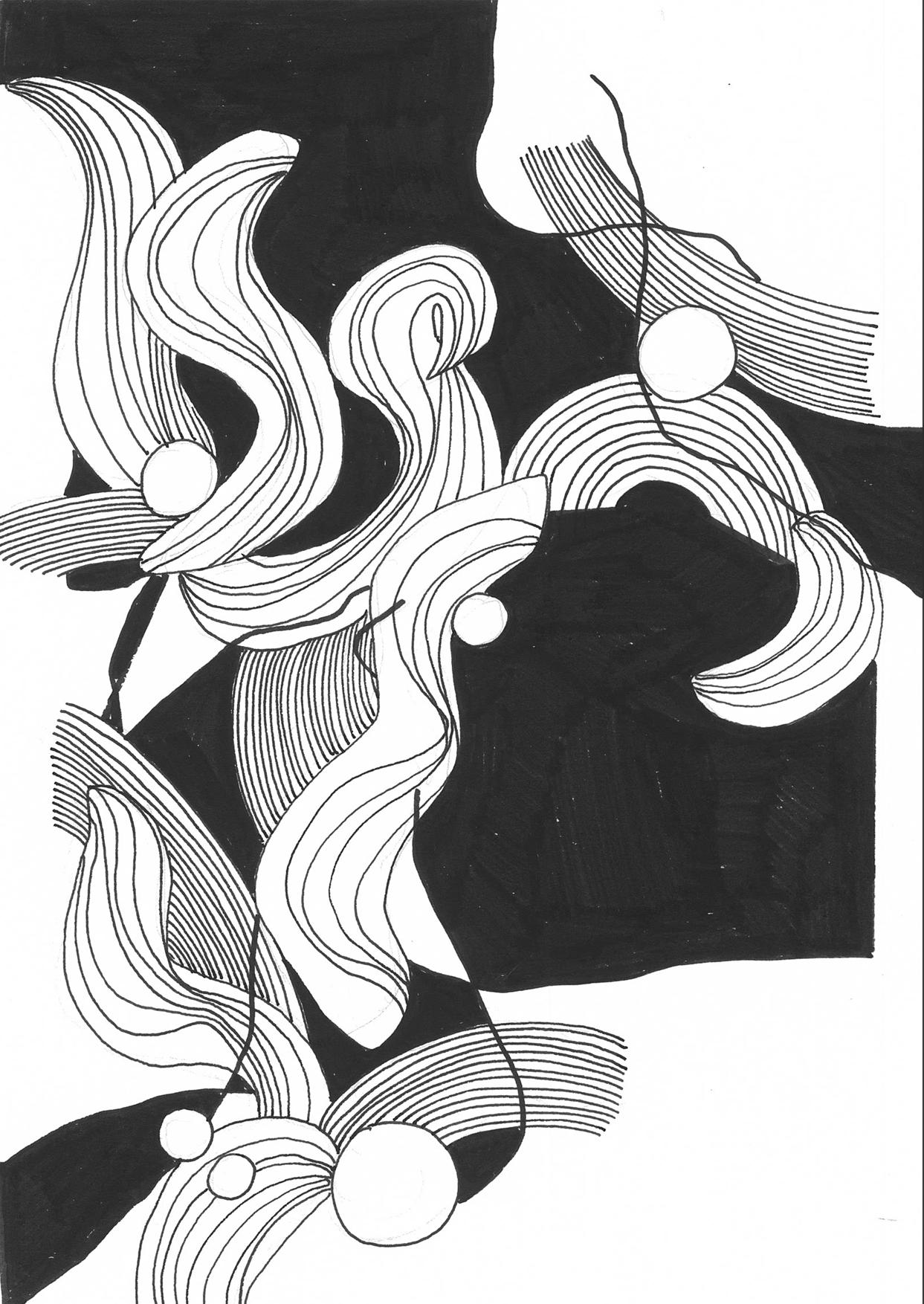

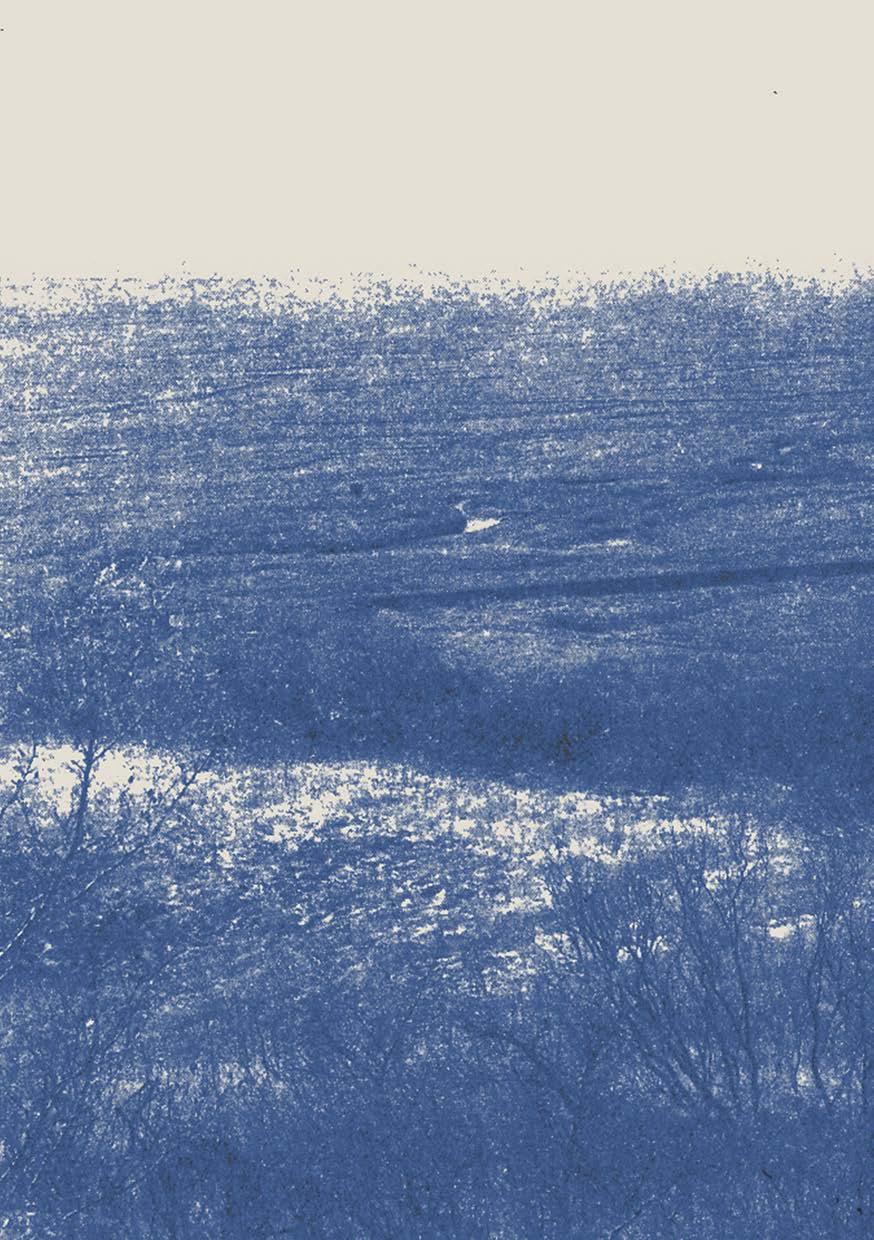

Grounding / Into the Cyanosphere

The atmospheric landscape of Iceland is, undoubtedly, of a highly unique and dynamic nature. A boundless horizon of blues, the shifting curtains of green and violet light of the Aurora, black sand beaches, waterfalls, rainbows, vast rivers of ice, and days of limitless light or darkness. It was this such fascination with the dynamics of light, climate and landscape dynamics that drew me into the realm of the Vatnajökull through the lens of atmosphere itself. Following on from my design explorations during the first semester, which focused on fieldwork methods of printmaking with melting glacial ice to produce an atmospheric ‘archive’ of present and historic landscape conditions, I began to consider the expansion of the project – both spatially and temporally – to consider global atmospheric and glacial futures in the shadow of large-scale ice melt. This recalibration of the conceptual narrative of my project led me from sky to ice to a new shade of blue: water.

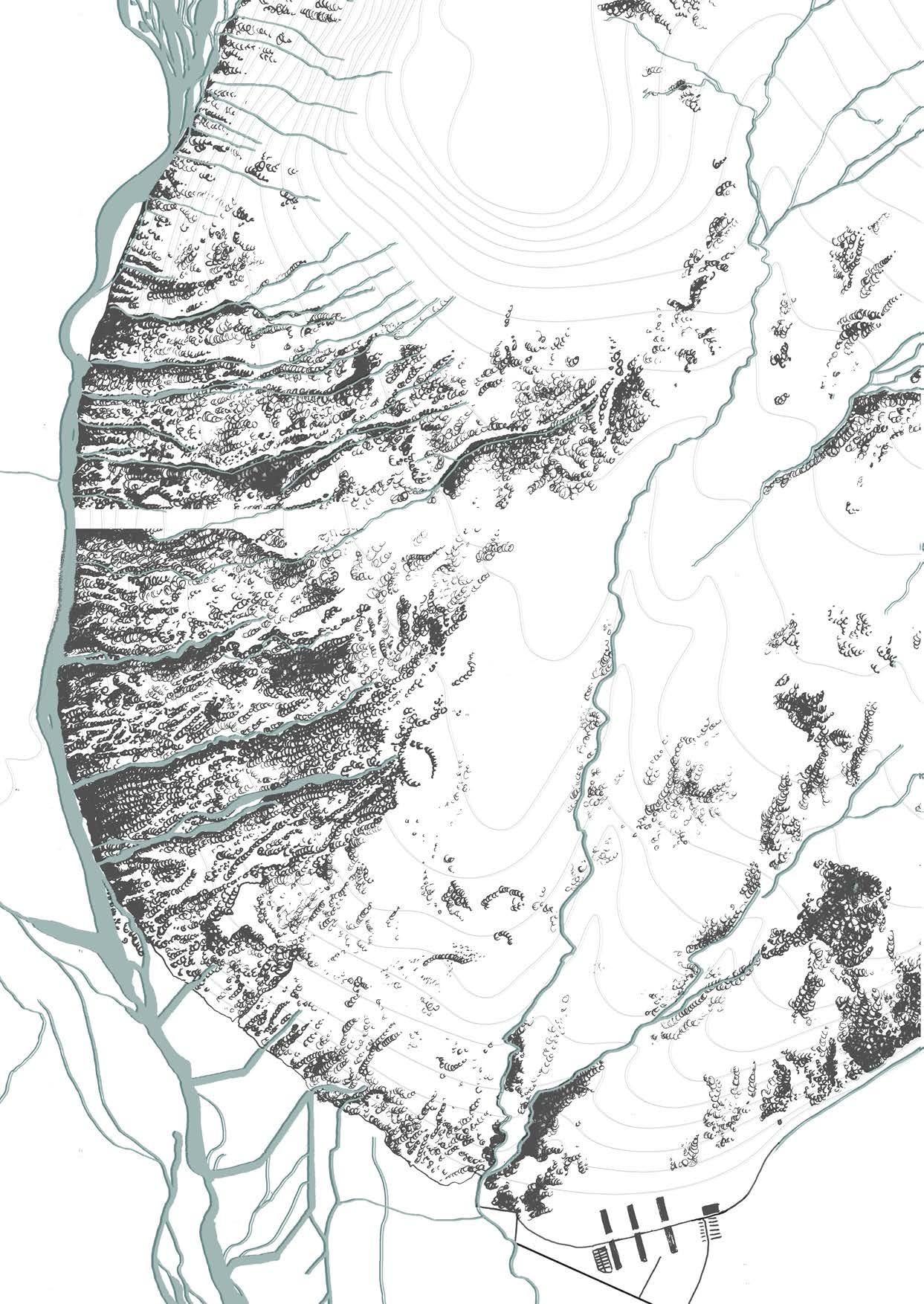

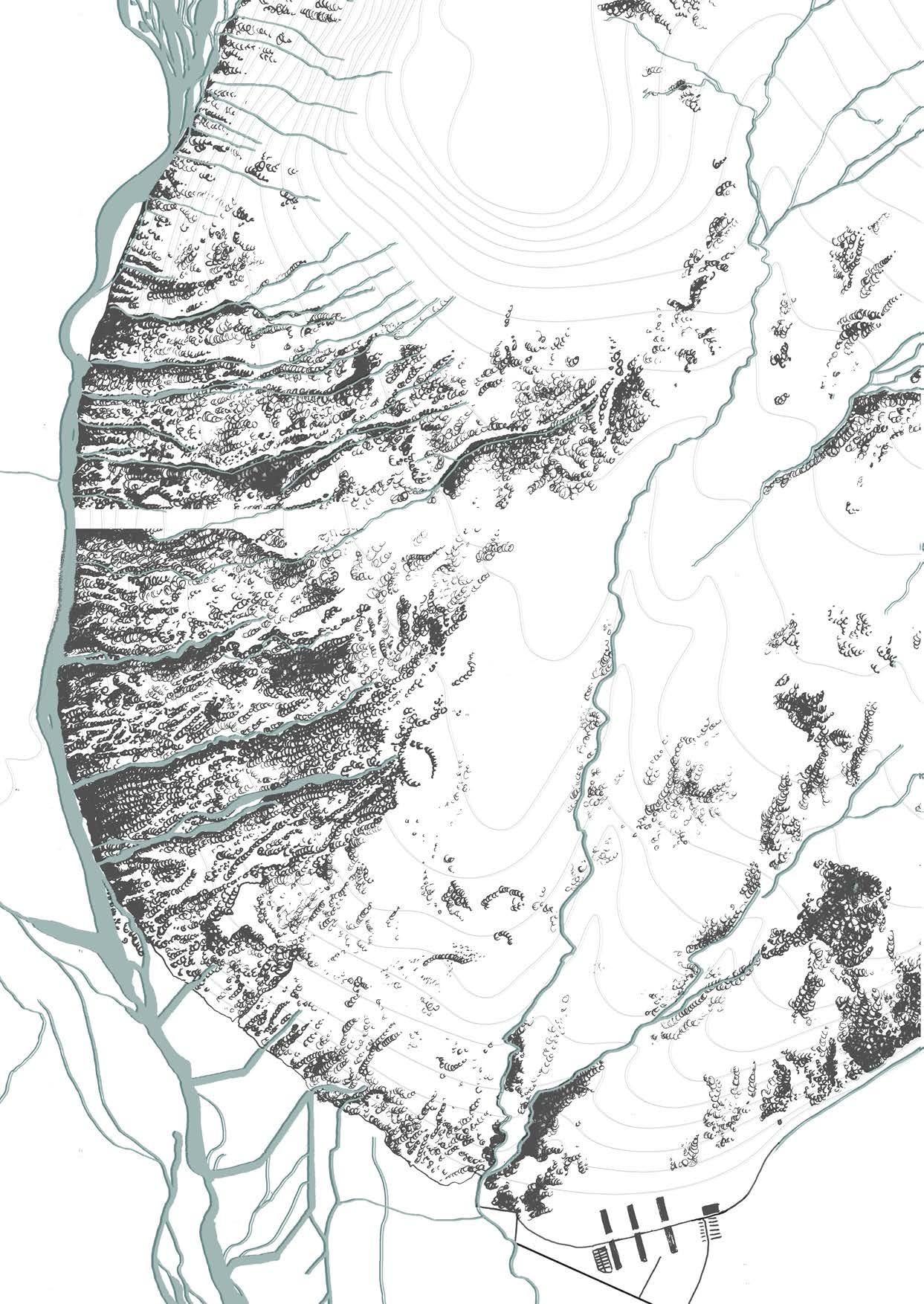

In oder to paint a comprehensive picture of the speculative future of a potentially ice-less Icelend, in the wake of complete glacial melt, I began to investigate unknown and unexplored territory: under the ice. Through an interpolation of subglcacial topographies measured by echoing imagery - which revealed the lowest subglacial elevations - as well as existing contours of the wider territory, predicted sea level rise, and an undertsanding of the morphological tendency of the rivers to braid and carve valleys; I sought to develop a speculative map of future water networks that illustrates the future watery landscape of the former glacier.

Deliquescing, or becoming liquid, represents not only the dynamic processes which bridge the gap between my conceptual thinking of semester one and two, but an emergent theme of anchoring design interventions in the dynamic atmospheric processes of the landscape itself. Speicifcally, anchored within the global impact of widespread glacial melt.

What could the memories preserved within the ice become? Which future landscape archives might emerge? How will the distinct atmosphere of the landscape transform as it becomes liquid?

12

Deliquescing

(n) to become liquid; To melt away; To disappear as if by melting.

Existing water networks at sites of Inestigation within the Vatnajökull

14

Skaftafell

Grímsvötn

Sauðárdalur

15

Subglacial topographies

Carving

The formative power of water on the landscape, which - in Iceland, owing to the morphology of the landscapehas a tendency to braid in lower energy environments. In more ferocious instances, the force of water has carved entire valleys.

17

18

PLUCKING

‘Glimpses of smoothly moulded granite bore witness to a much larger ice sheet that had covered Patagonia 20,000 years ago. Yet despite the erosive force of thousands of years of moving ice, the mountain sides were often lumpy, crumpled like used paper bags, capped by gleaming snowdrifts. This apparent contradiction of juxtaposed smooth and roughly hewn rock reflects two important processes by which glaciers sculpt their landscape, which often occur on different sides of a mountain when buried by ice. ‘Abrasion’, a bit like sanding, occurs on the upstream side as the glacier flows over the obstacle and its base melts under pressure, while ‘plucking’ (or quarrying) happens on the downstream side, when meltwater worms its way into rock crevices and freezes as pressure is relieved the rock becomes weakened and fragments are eventually pulled away from the mountain as the ice moves downhill’2

19

2Jemma Wadham, Ice Rivers: A Story of Glaciers, Wilderness, and Humanity (London: Penguin Random House UK, 2022), 122.

20

21

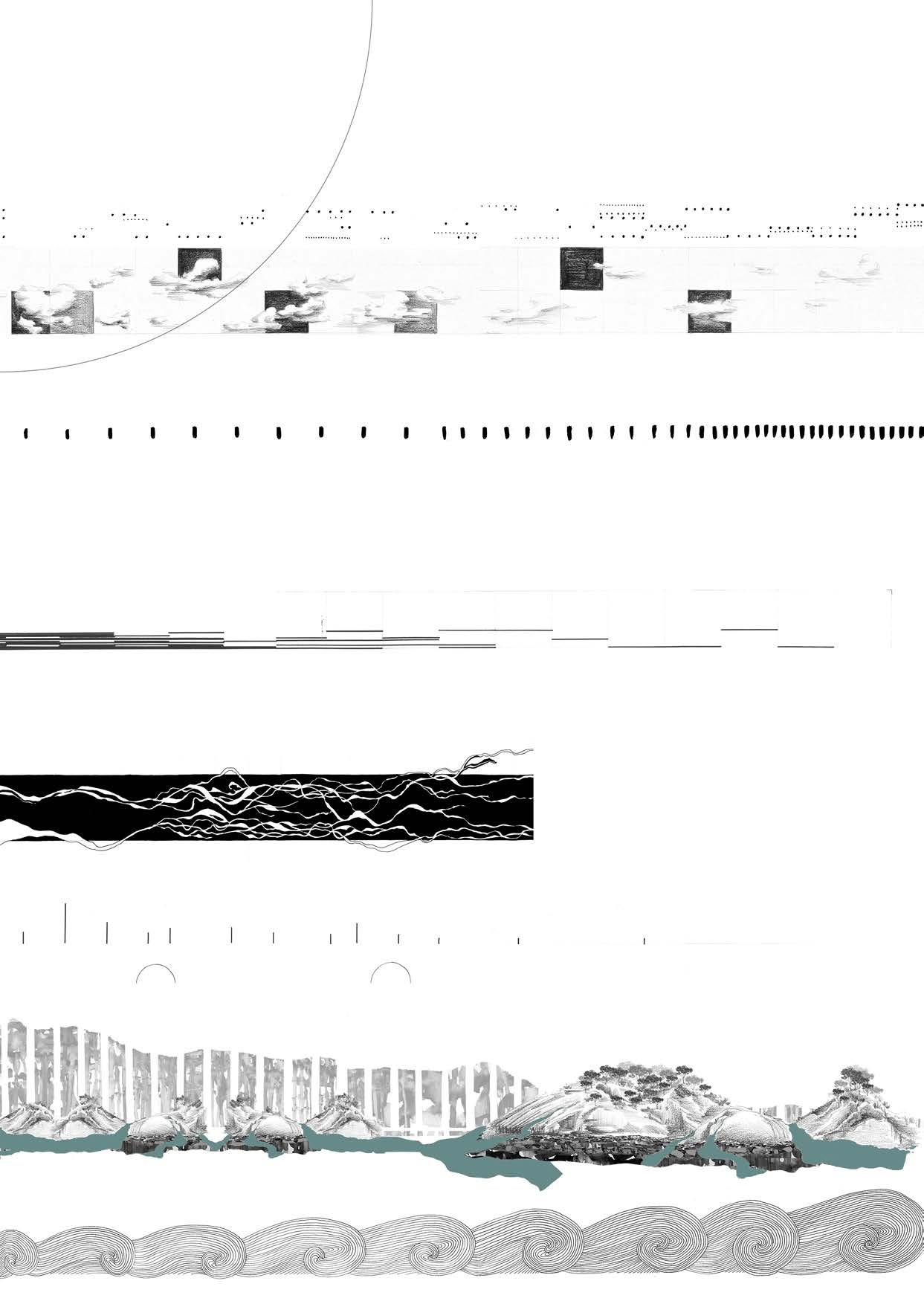

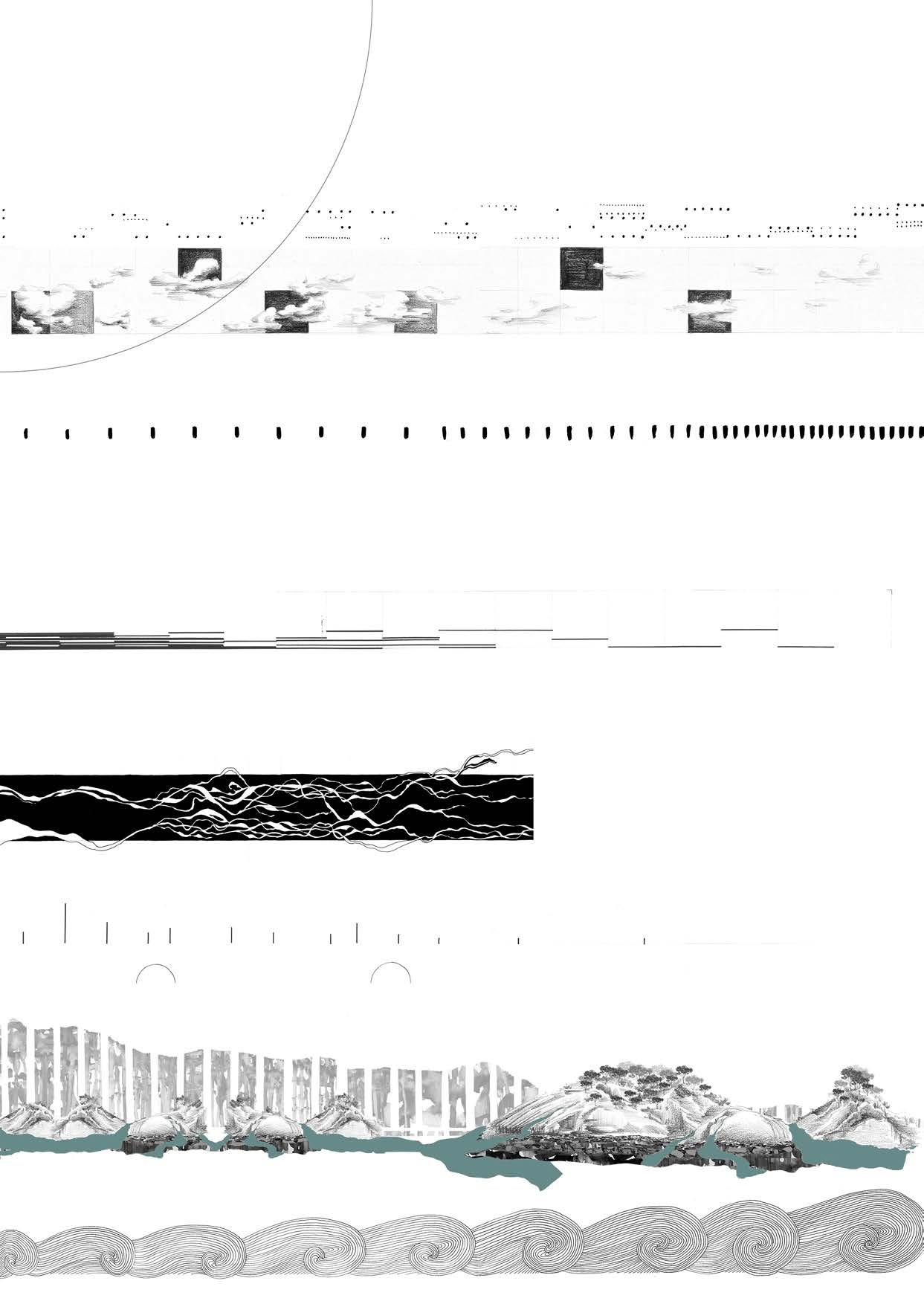

Scoring the dynamic atmopsheric systems of the landscape with increasing climate instablility over the next two hundred years

Prevalence of sunlight

Projected cloud change

Volcanic eruptions

Sublacial light levels

Frequency and intensity of Jökaulhaups

Glacial discharge

Glacial melt

Disrupted ecological succession

Sea level rise

22

23

Katie Paterson, First There is a Mountain, Various locations along the UK Coastline, March 31 - October 27 2019, Participatory Artwork. https://www.firstthereisamountain.com

Katie Paterson, First There is a Mountain, Various locations along the UK Coastline, March 31 - October 27 2019, Participatory Artwork. https://www.firstthereisamountain.com

GLACIER SANDCASTLES

Inspried by Katie Paterson’s ‘First There is a Mountain’3, I began to experiment with more sculptural, active experiments in the expanded sense of drawing. Using negative impressions of the Vatnajökull’s topographies, I built sandcastles on the beach, scultping sand into microgeological forms of the glacier. In an exploration of the formative - and often destructive - effect of water on these fragile landscapes, ocean tides and poured water recreated the vast geological forces at play. Smoothing ragged peaks, braiding rivers, carving valleys, and swelling lagoons. Through the creation of these ephemeral models, and film, I began to mediate on the post-glacial, watery future of the Vatnajökull at large, and explore which new landforms might emerge.

3Katie Paterson, First There is a Mountain, Various locations along the UK Coastline, March 31 - October 27 2019, Participatory Artwork.

‘The river of course becomes smaller a these tributarie are passed. It shrinks first to a brook, then to a stream; this again divides itself into a number of smaller streamlets, ending in mere threads of water. These constitute the source of the river, and are usully found among the hills /

a brief residence among the mountains would prove to you that they are fed by rains /

Whence comes the rain which forms the mountain streams? Rain does not come from a clear sky. It comes from clouds. But what are clouds? /

What, then, is this thing which at one moment is transparent and invisible, and at the next moment visible as a dense opaque cloud? It is the stream or vapour of water from the boiler /

Is there any fire in nature which produces the clouds of our atmopshere? There is : the fire of the sun /

Thus, by tracing backward, without any break in the chain of occurences, our river from its end to its real beginnings, we come at length to the sun /

You soon learn that the mountain snow feeds the glacier. By some means or other the snow is converted into ice. But whence comes the snow? Like the rain, it comes from the coulds, which, as before, can be traced to vapour raised by the sun. Without solar fire we could have no atmospheric vapour, without vapour no clouds, without clods no snow, and without snow no glaciers. Curious then as the conclusion may be, the cold ice of the [Vatnajökull] has its origins in the heat of the sun. 4

28

4John Tyndall, “Clouds, Rains and Rivers,” in The Forms of Water in Clouds and Rivers, Ice and Glaciers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 2-7.

29

30

‘We have here a example of the manner in which phenomena, apparently remote, are connected together in this wonderful system of things that we call Nature. You cannot study a snowflake profoundly without being led back to it step by step to the constitution of the sun. It is thus throughout Nature. All its parts are interdependent, and the study of any one part completely would really involve the study of it all.’5

31

5 John Tyndall, “The Waves of Light,” in The Forms of Water in Clouds and Rivers, Ice and Glaciers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 14.

Part Two / Proposal

ATMOSPHERIC FUTURES

My investigations into the dynamic atmsopheric systems unfolding in the coming centuries led me to consider the diverse range of hydrologies that would emerge following glacial melt. I landed on three sites in particular - each of high conservation value and unique water charactersistics - to explore within my proposals for the Vatnajökull Botanical Parks. The manmade resevoir and former wetland systems of the Sauðárdalur valley; the frequently flooded plains of the birch forests of Skeiðarársandur and Skaftafell; and the unique habitat of the Grímsvötn subglacial geothermal caldera. Each site represents unique possibilities to respond to the notion of ‘archiving’, distinct in character, yet united by their regime of disturbances, their moments of stasis and dynamisism, and their focus on preserving and facilitating ecological resilience.

32

33

Chapter Two

THE FUTURE RUINS OF

THE

SAUÐÁRDALUR

34

35

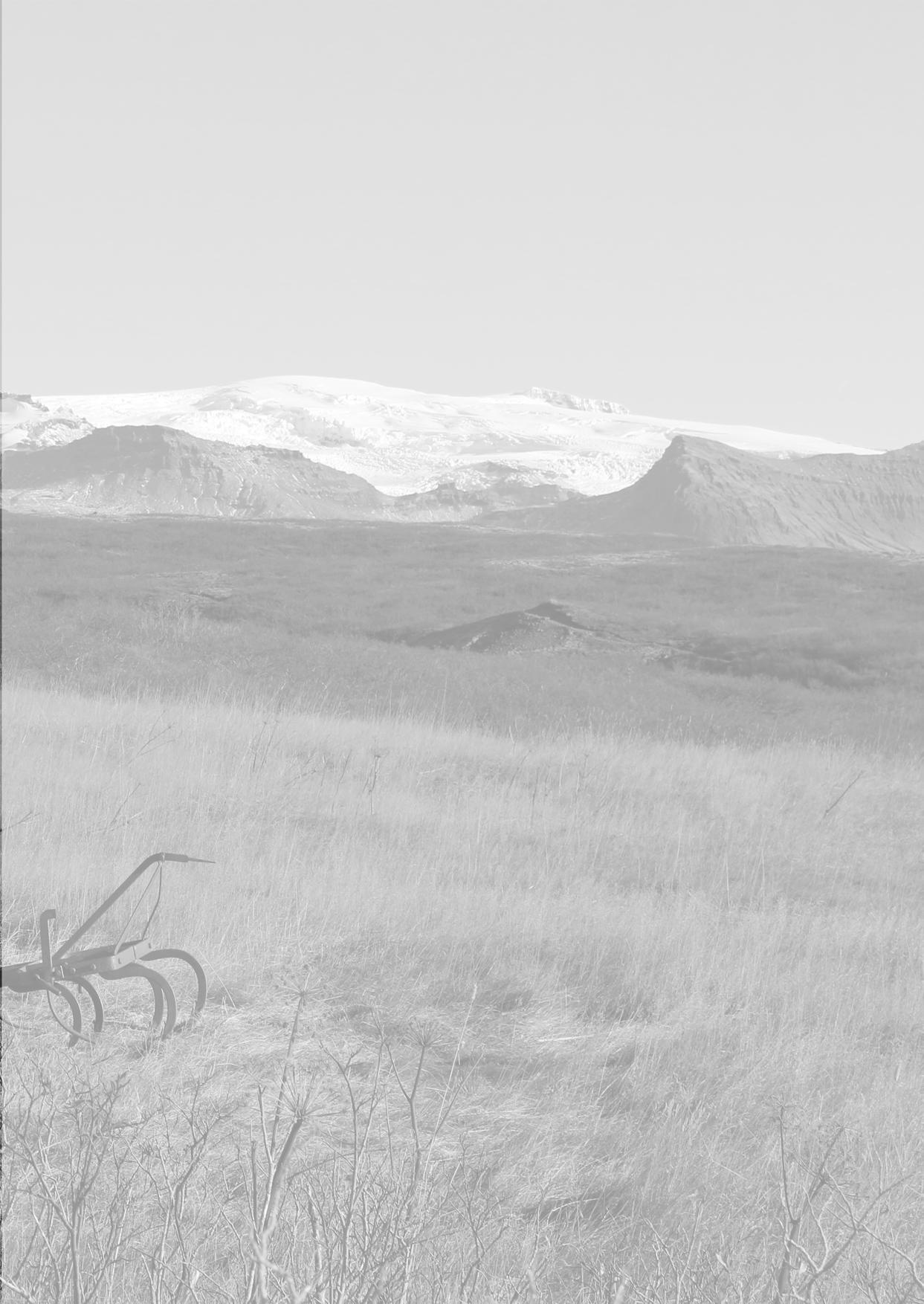

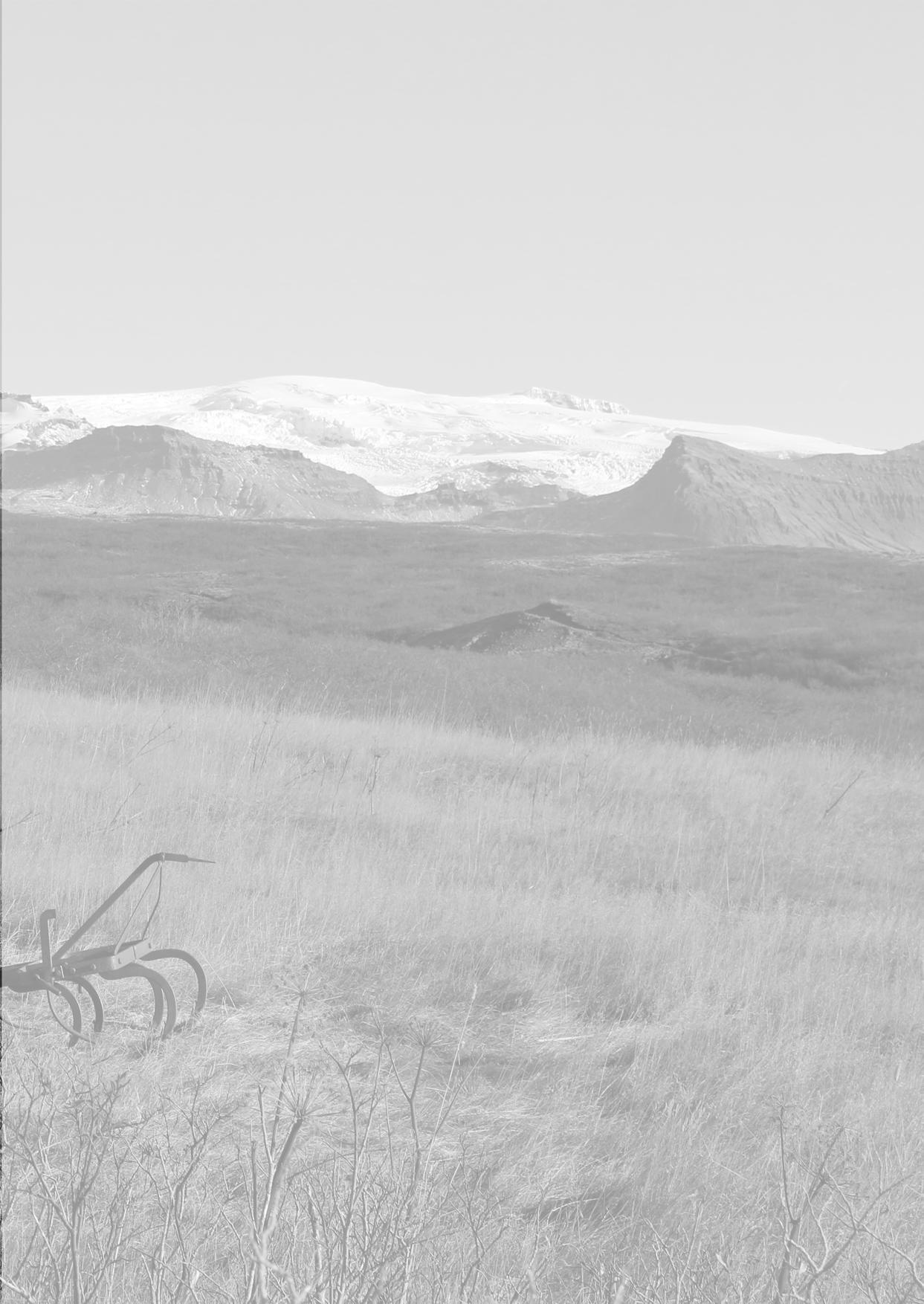

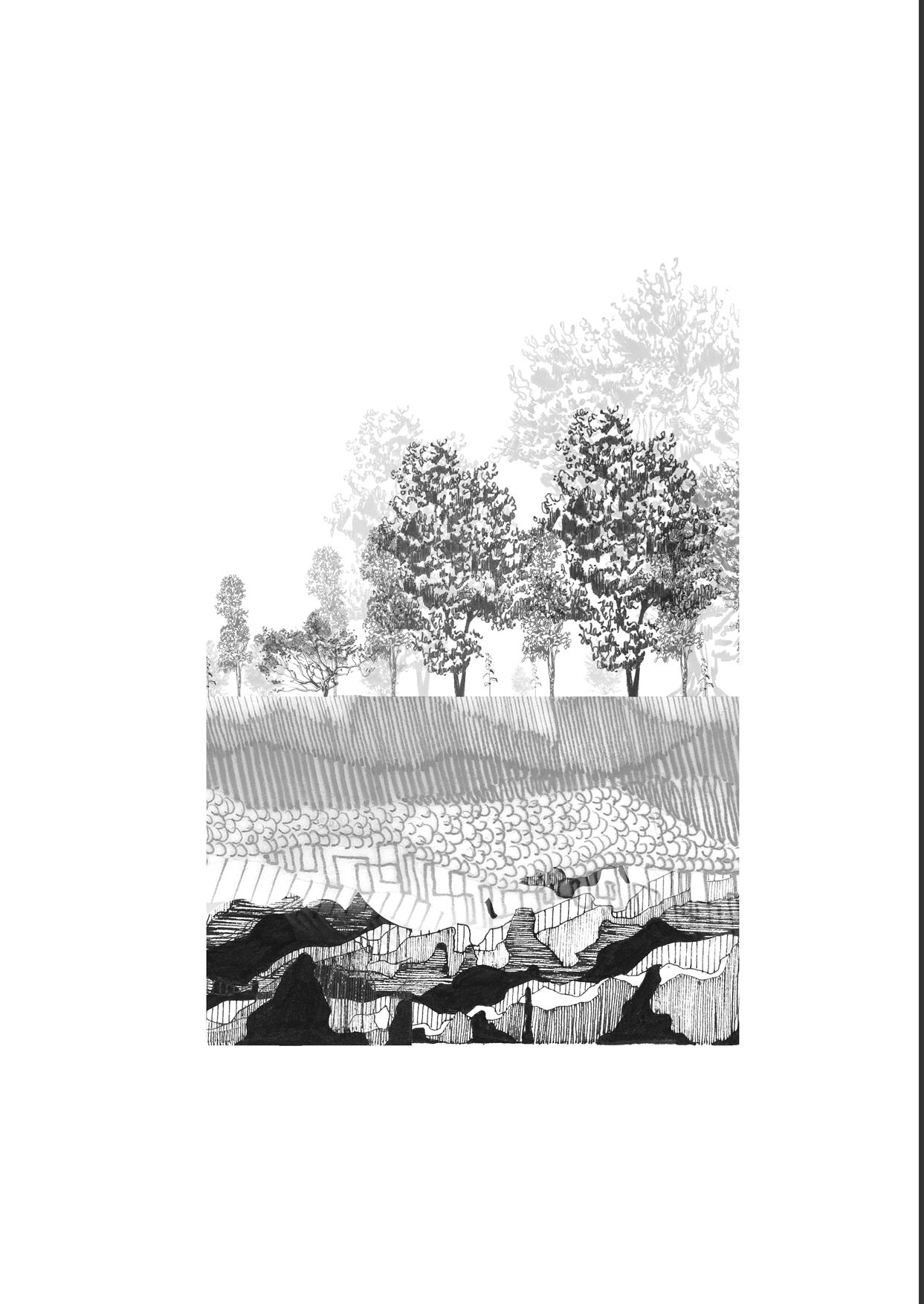

Existing conditions of the Sauðárdalur Valley

The Sauðárdalsstífla is one of five dams that, since their comlpetion in the Autumn of 2006, have captured the power of the Jökulsá á Dal river to create the Hálslón storage Reservoir. What was once a highly dynamic and forceful landscape, carving valleys and braided rivers fom the glacier out to the sea, now feeds the production of power for the Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant. The remains of the north-easterly region of Iceland, which is known to have once been a far more lively landscape - acting as a refuge for poets and artists6, as well as ecologically in the form of extensive wetland and heathlands, fed routinely with glacial flour from jökaulhaups - is now a barren place, starved of water, nutrients and life.

36

6Andri Snær Magnasson, On Time and Water: A Histry of Our Future (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2021).

37

Materiality and form of the Sauðárdalsstífla

In line with the inherently contrasting qualities of the landscape of Icelandthe land of ice and fire - the materiality and form of the Sauðárdalsstífla impose an urban-ness and rigidity upon an otherwise wildly dynamic landscape. The combination of concrete, loose

stone and basalt, juxtaposed with the ebbs and flows of water create a sense of tension between humanimposed lines of forces against the natural desire for the landscape to shift. All the same, the the structure is monumental in scale, a reflaction of the Vatnajökull‘s natural monuments - mountains, volcanoes, glaciers - in the blue of the distance.

38

39

40

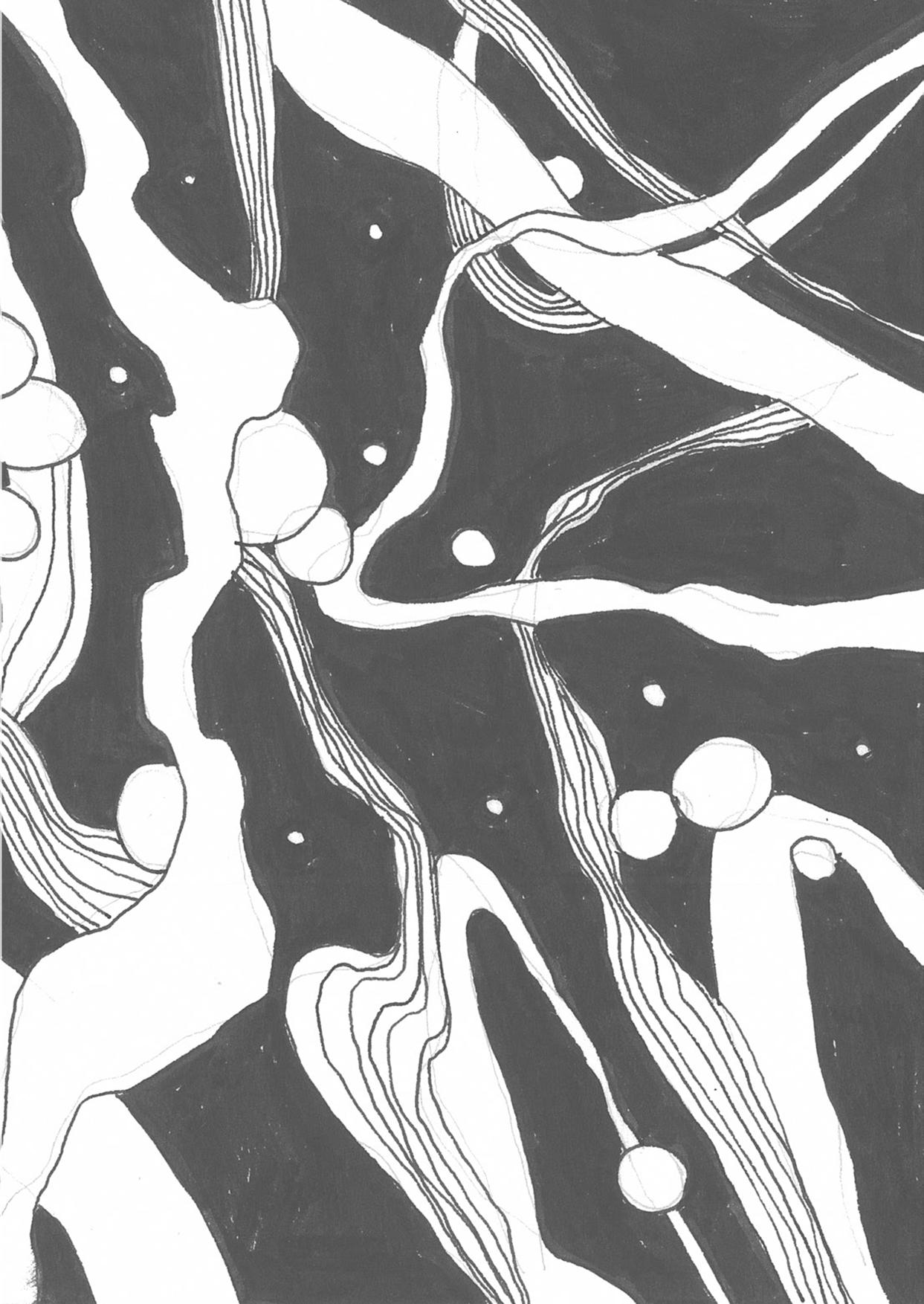

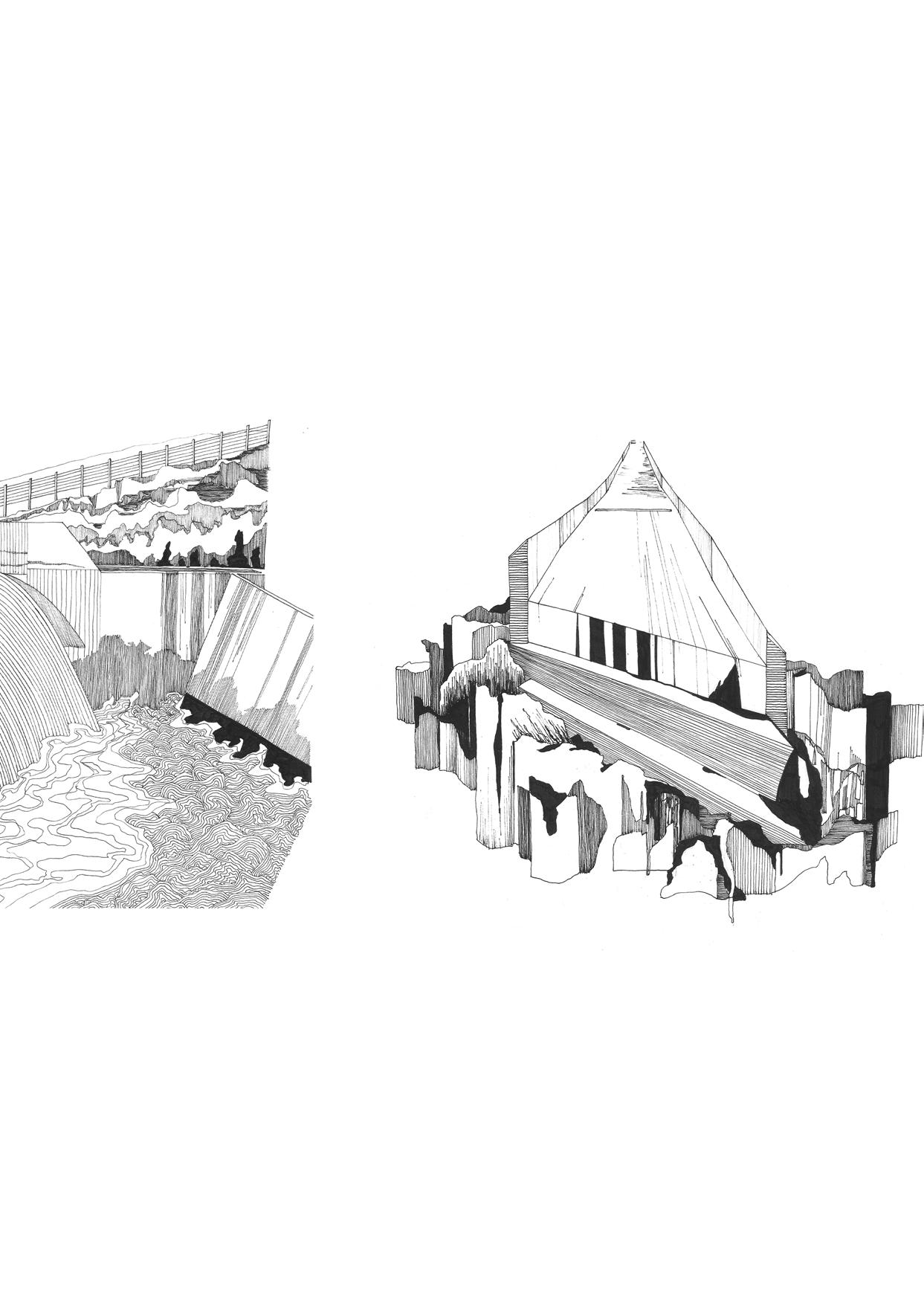

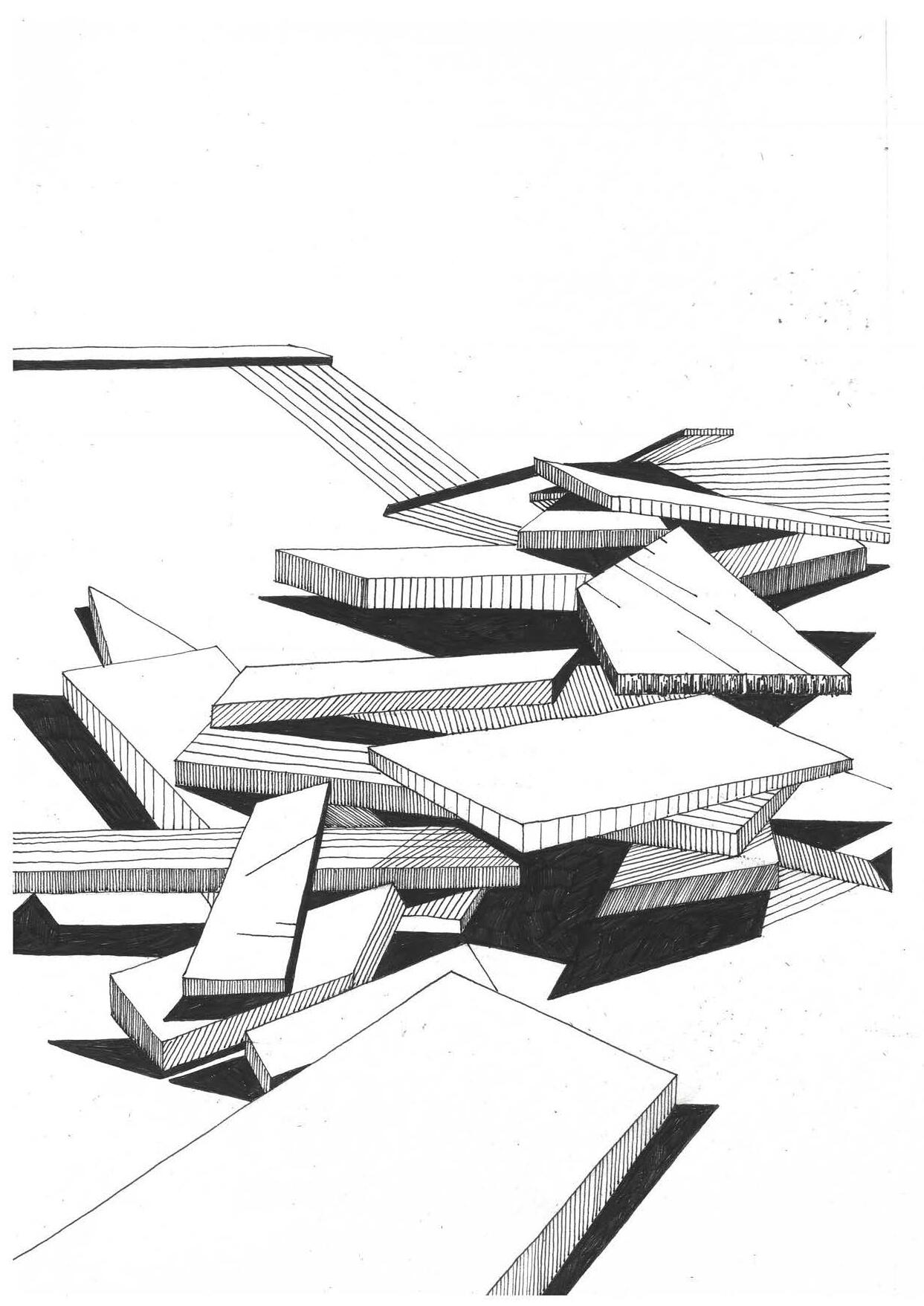

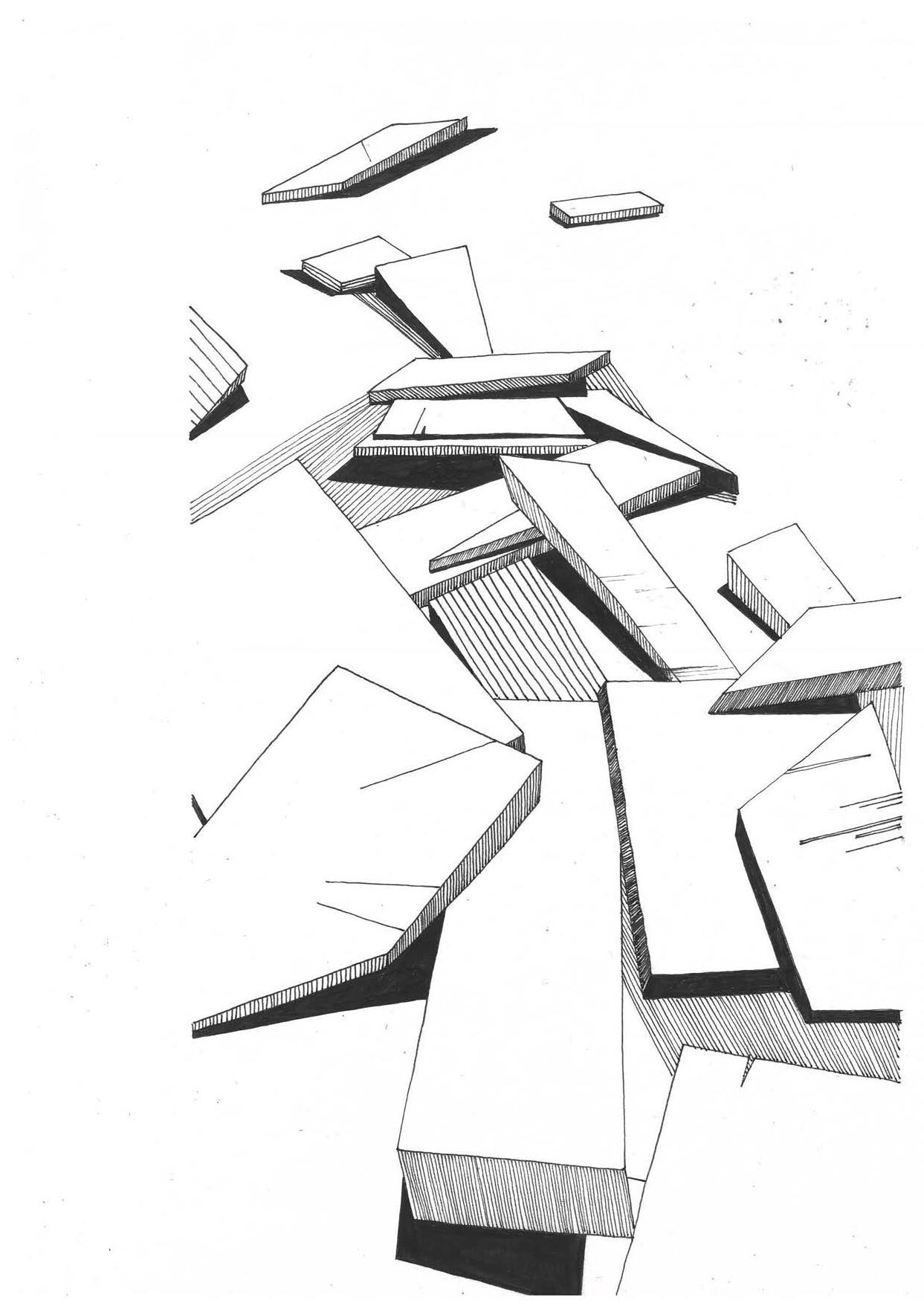

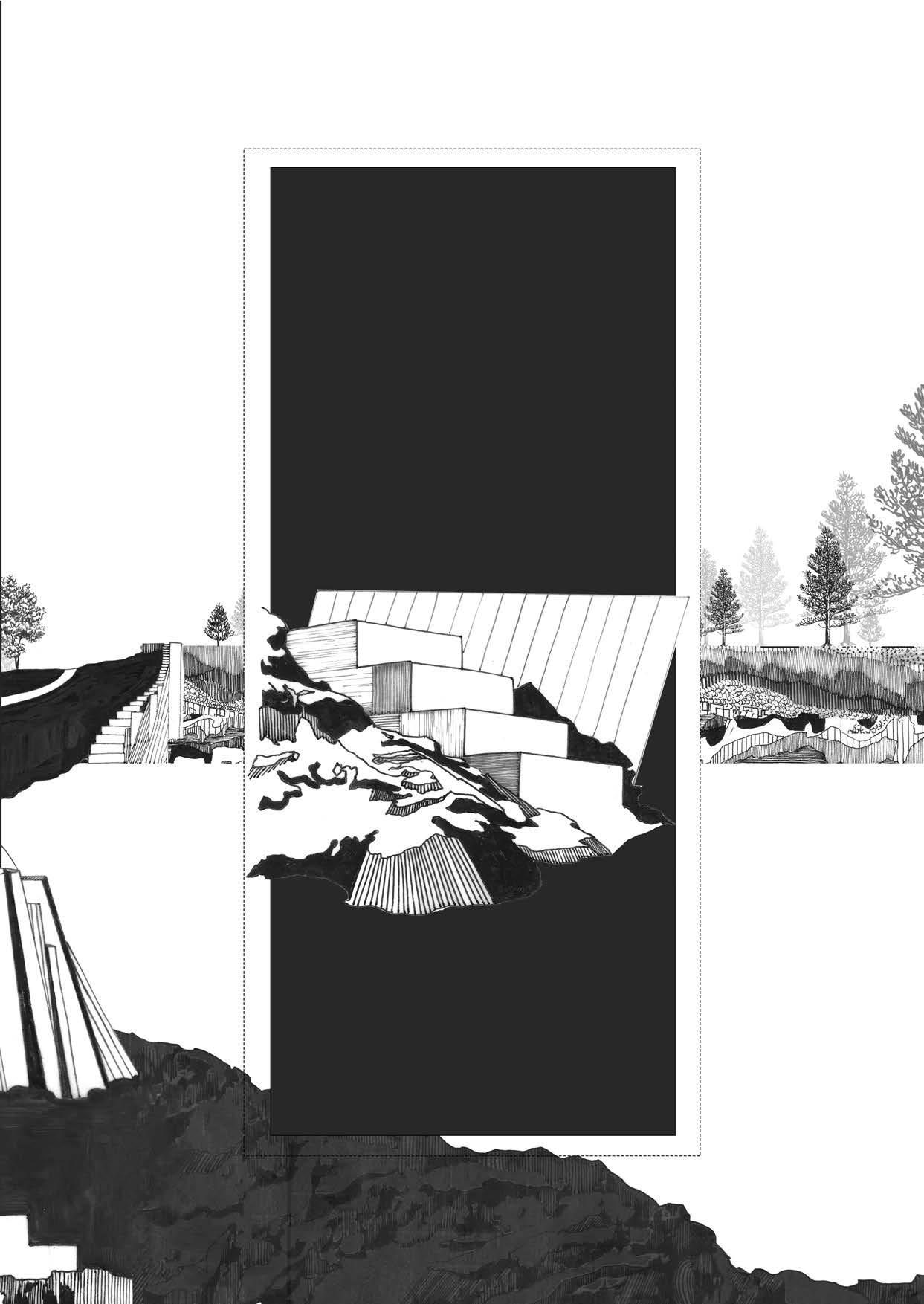

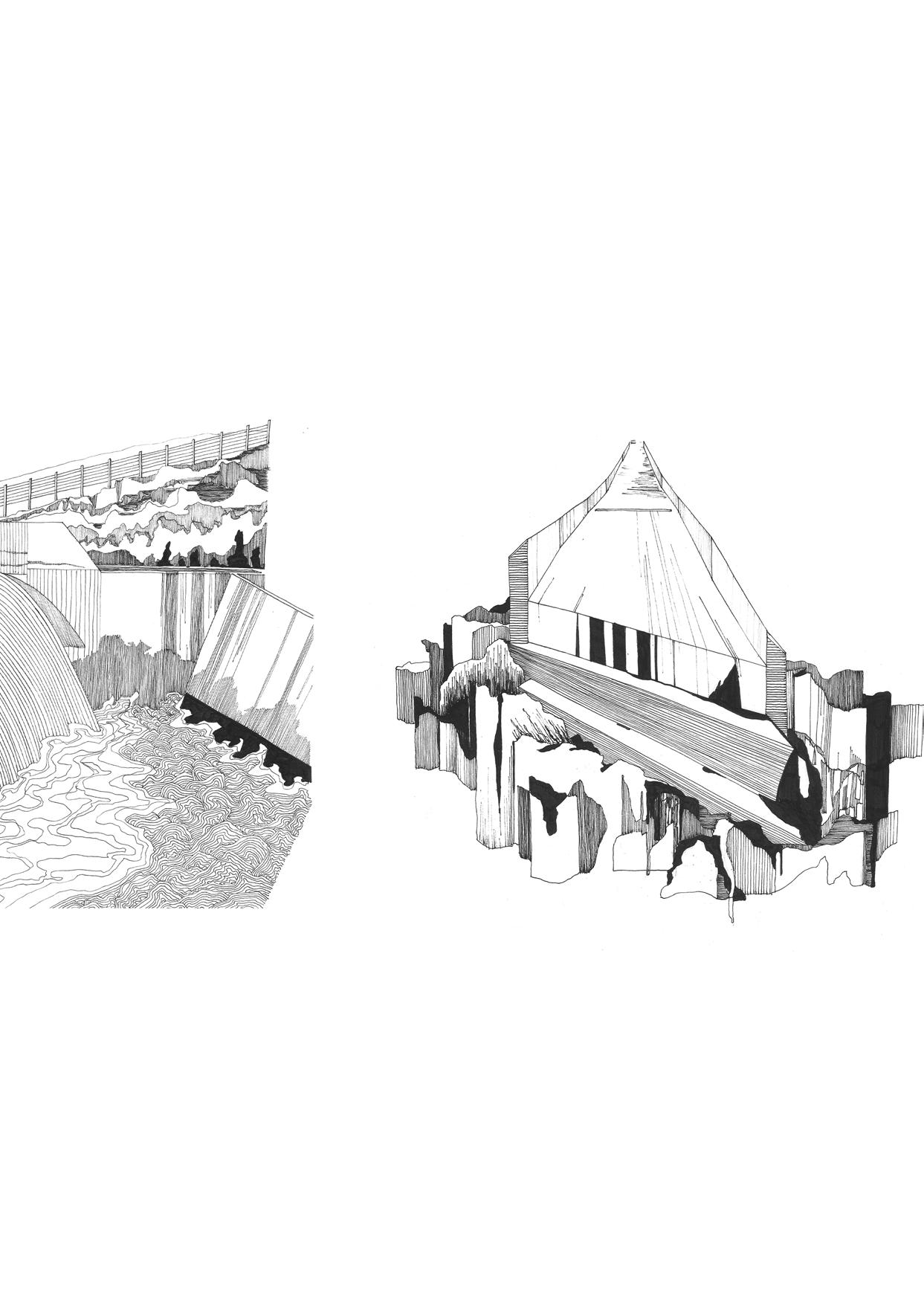

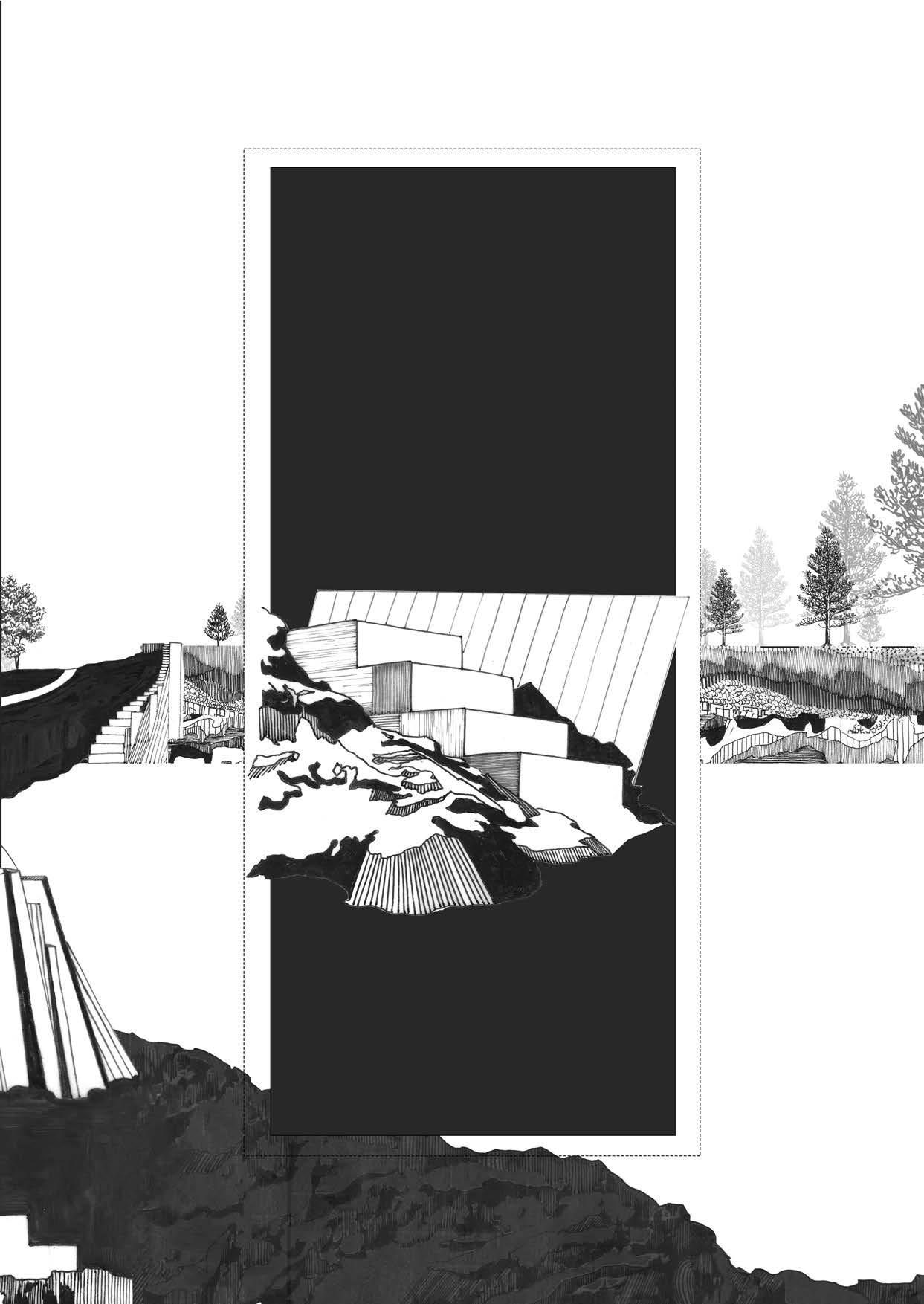

DELTAWERK / Landscape installation and ‘Hardcore Heritage’

The Atlas of drawings I created in study of RAAAF’s landscape project ‘Deltawerk’7 proved instrumental in the conceptual development of of my interventions for the dam site. Where I had originally thought to propose the decomissioning of the dam and renaturalisation of the Jökulsá á Dal river system, I imagined the reuse of materials would take on relatively formal and conventional forms: a wetland walkway, walls, and so on. However, my studies of ‘Deltawerk’, as well as RAAAF’s radical approach to preserving cultural heritage, so called ‘Hardcore Heritage’, sparked new ideas on how the landscape might transform in line with my conceptual notions of archives, memory, and the natural and atmospheric processes of the landscape itself. The irregular arrangements of the concrete pieces, the angled placement, as well as the monumental scale of the project, contribute not only to a unique, vast, and immersive landscape experience, they encourage a more unprogrammed use of the space.

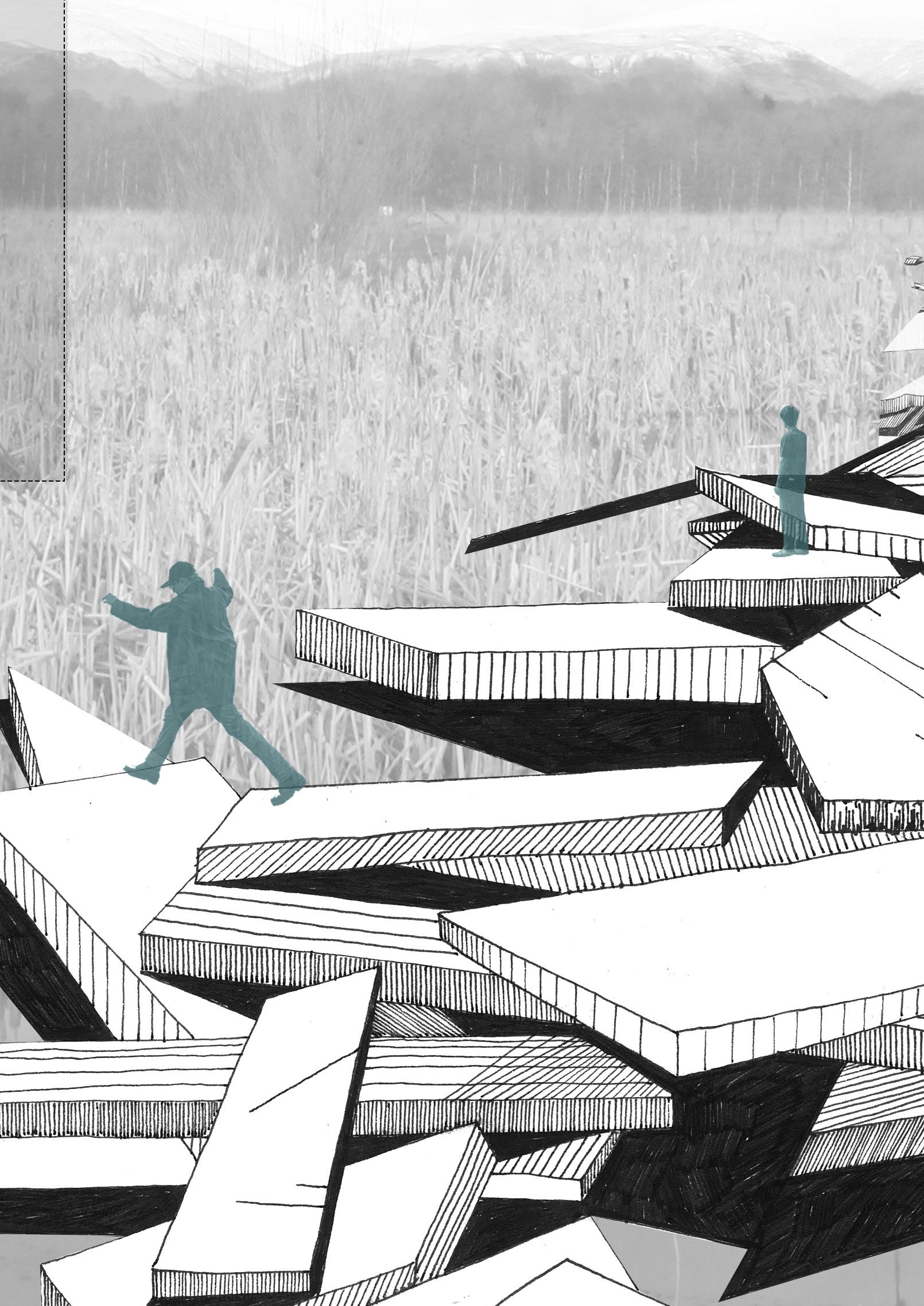

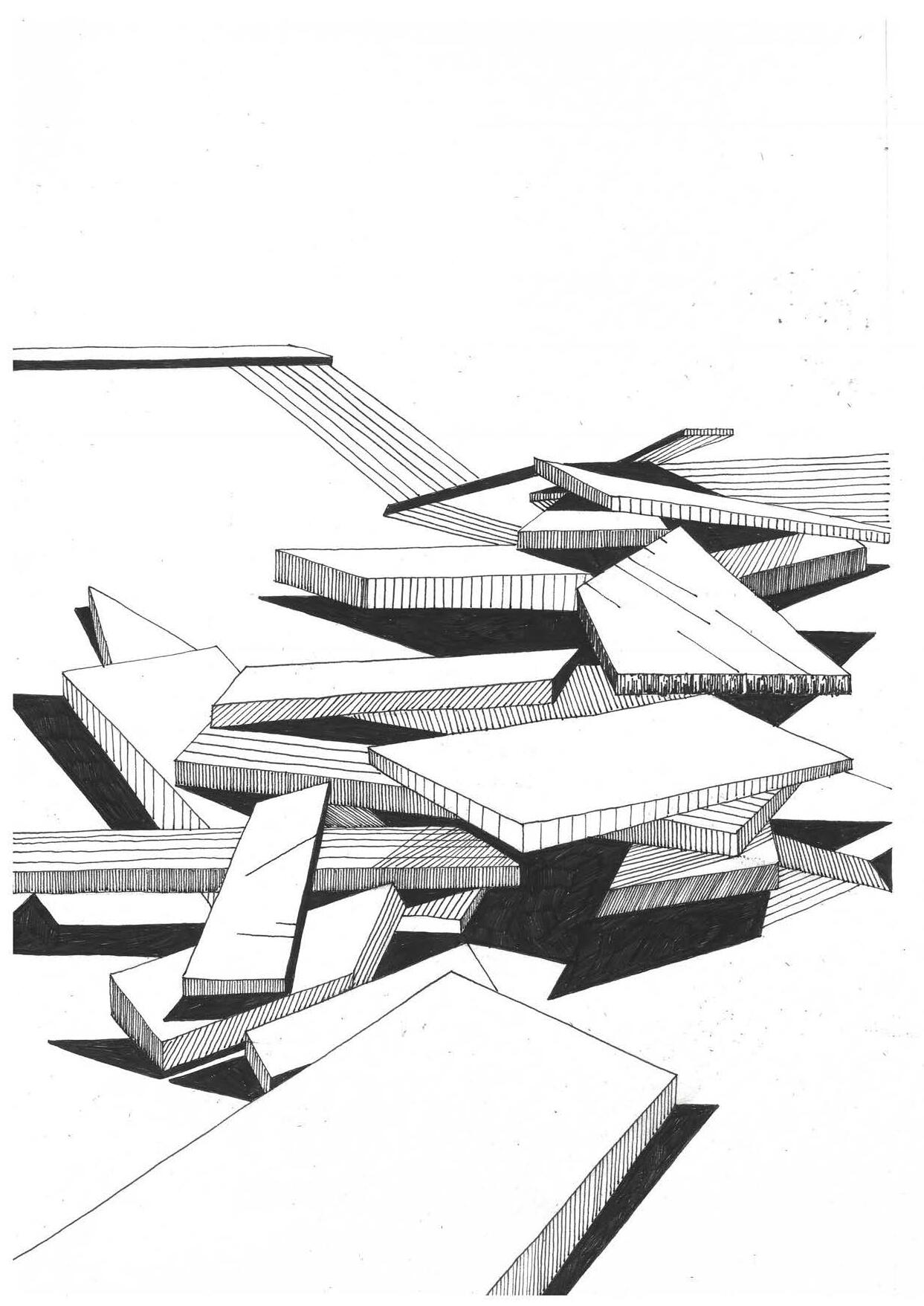

I began to envision the decommisioning of the Sauðárdalsstífla as a design intervention for the creation of new ruins - the enduring structures transformed into monuments for the future that speak to urban glacial legacies. At the same time, the walkway could take on a more spontaneous form. In a manner comparable to glacial erratics, the concrete pieces of the dam might ‘land’, either through falling or placement, within the landscape. Once placed, they would be allowed to shift and eventually erode with the forces of the water released from the resevoir. The result is a walkway that continues to extend and transform with both the deconstruction of the dam and the changing energies of the landscape; which hopes to stimulate a higher engangement and sense of exploration or play within the landscape. As open-ended and continual a project, the experience of the ruins - both of the walkway and the dam itself - is ephemeral. Still, at any given time, one might be able to step into the ruined landscape and catch a glimpse of what once was, with possibilities to imagine what might yet be.

41

7RAAAF / Atelier de Lyon, Deltawerk, 2018, landscape architecture installation project, Noordoostpolder, the Netherlands, accessed April 1 2023, https://www.raaaf.nl/en/projects/1005_deltawerk.

42

43

44

Exctraction of forms for decomissioning of the Sauðárdalsstífla

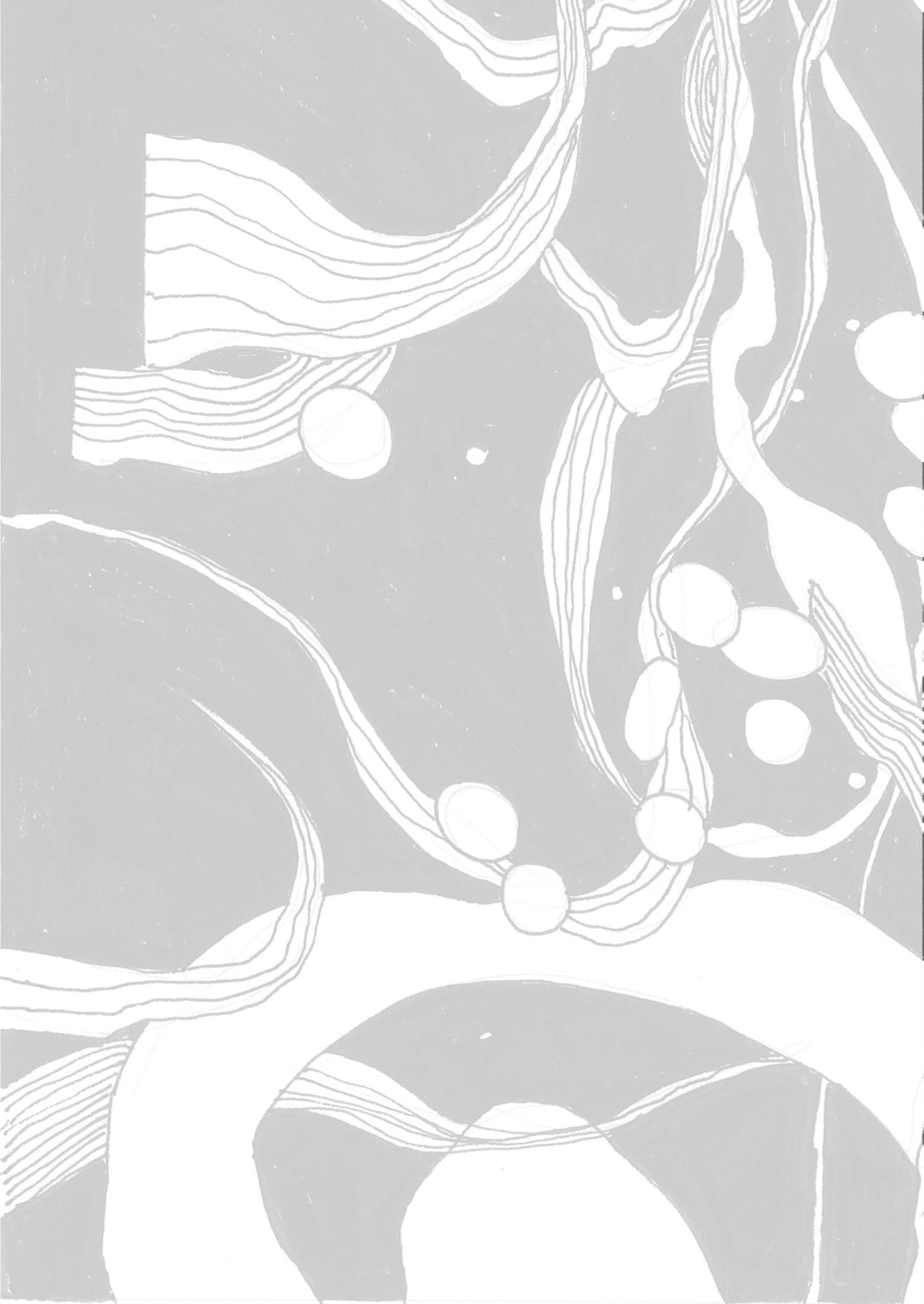

In order to develop a design for the decomissioning of the dam - as well as the future form of the new ruins - I turned once again to my drawing archives of the ‘Deltawerk‘ project. In tracing the patterns created by light and shadow, I extraced geometric shapes and angled lines to compose a design of destruction.

45

Proposed decomissioning of the Sauðárdalsstífla

The proposed choreography for the deconstruction of the structure takes cues from the Elwha and Glines Canyon dam rmoval project of 2011-2014 to employ the notch and release approach. The slow process of this method allows water to drain gradually and consistently from notches cut into the concrete. As the sediment trapped behind the dam flows downstream in a steady rate, the affected ecosystems downstream are allowed to adjust to the changes gradually8. The sediment influx, over several years, transforms the morphology of the river channels from a tendency to pool (as seen in the existing conditions map on page 37), towards a tendency to braid, as seen ubiquitously accross the outwash plains, valleys and coastlines of the Vatnajökull. These geomorphic alterations have significant ecological implications for the river system, supporting the community of organisms that make their home in the riverbed, and improving the habitat structure for birds, fish, insects, and more. Despite the vast scale of the proposed interventions to deconstruct the Sauðárdalsstífla, and the brutalism of the concrete materials and forms, it is the hope that this sensitive and careful approach will nurture the ecosystem of the valley, allowing it to flourish. A design of destruction juxtaposed with a narrative of rebirth: the rebirth of the Jökulsá á Dal river.

1,100m

8“Elwha River Restoration,” National Park Service, accessed March 3 2023, https://www.nps.gov/olym/learn/nature/elwha-ecosystem-restoration.htm

46

47

1,100m

48

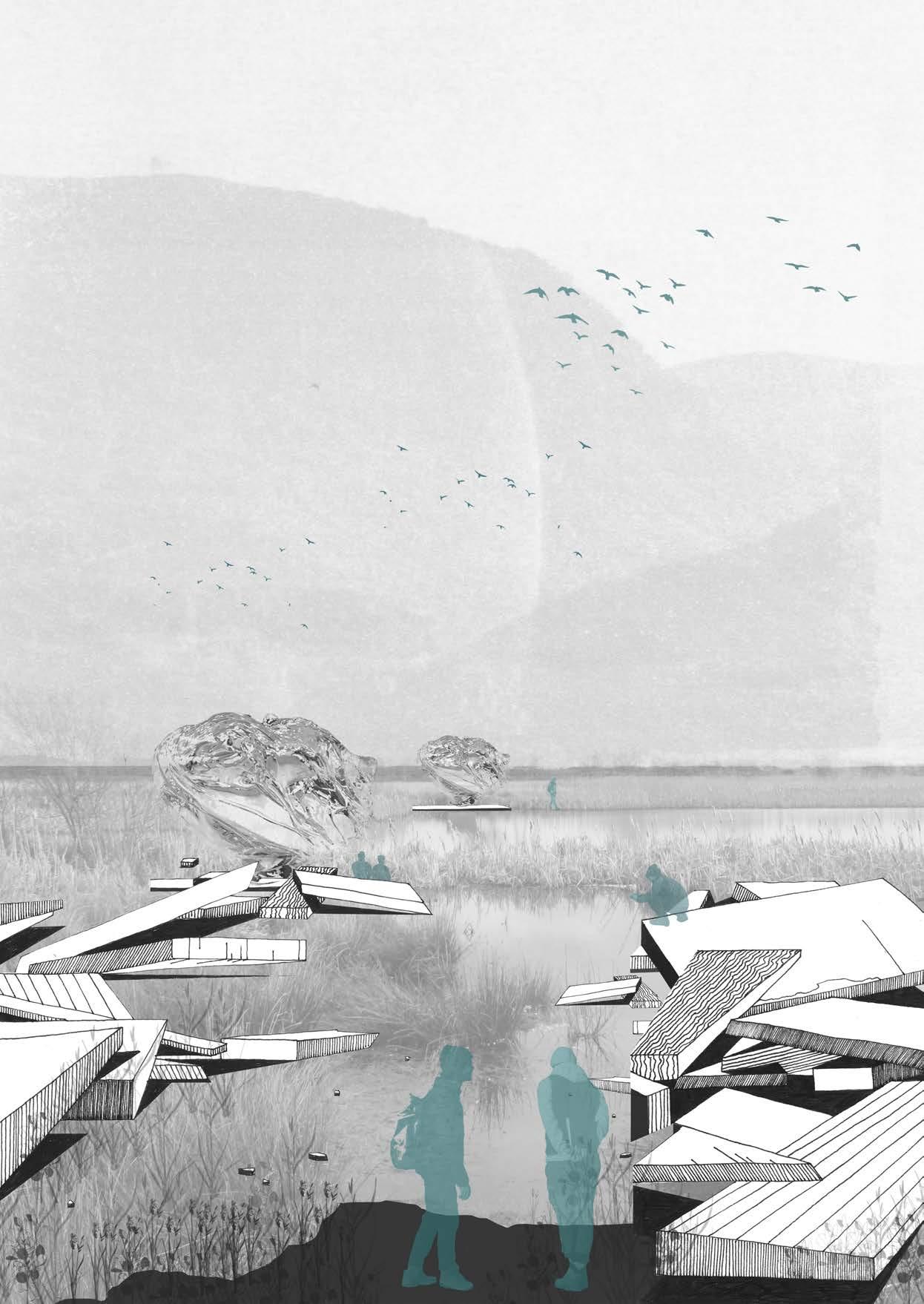

The Future Ruins of the Sauðárdalur

For the complete archival collection, see Appendix, 142.

49

50

51

Proposal for the Future Ruins of the Sauðárdalur Valley

52

53

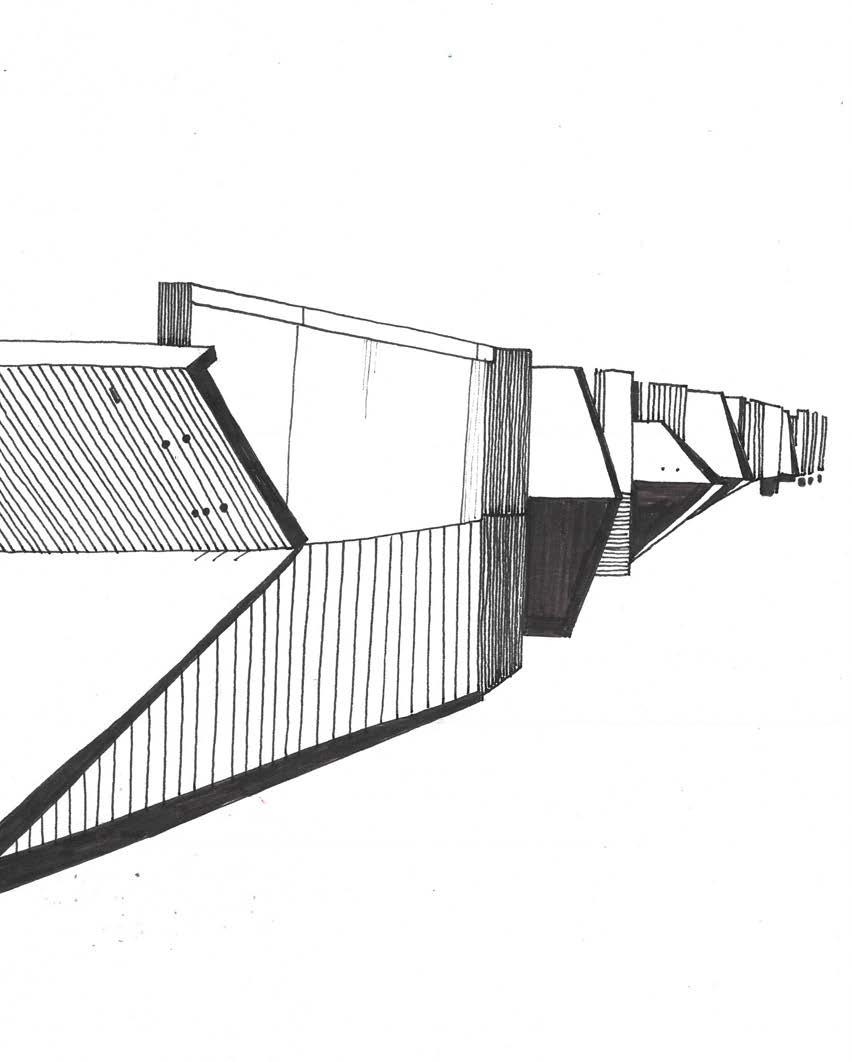

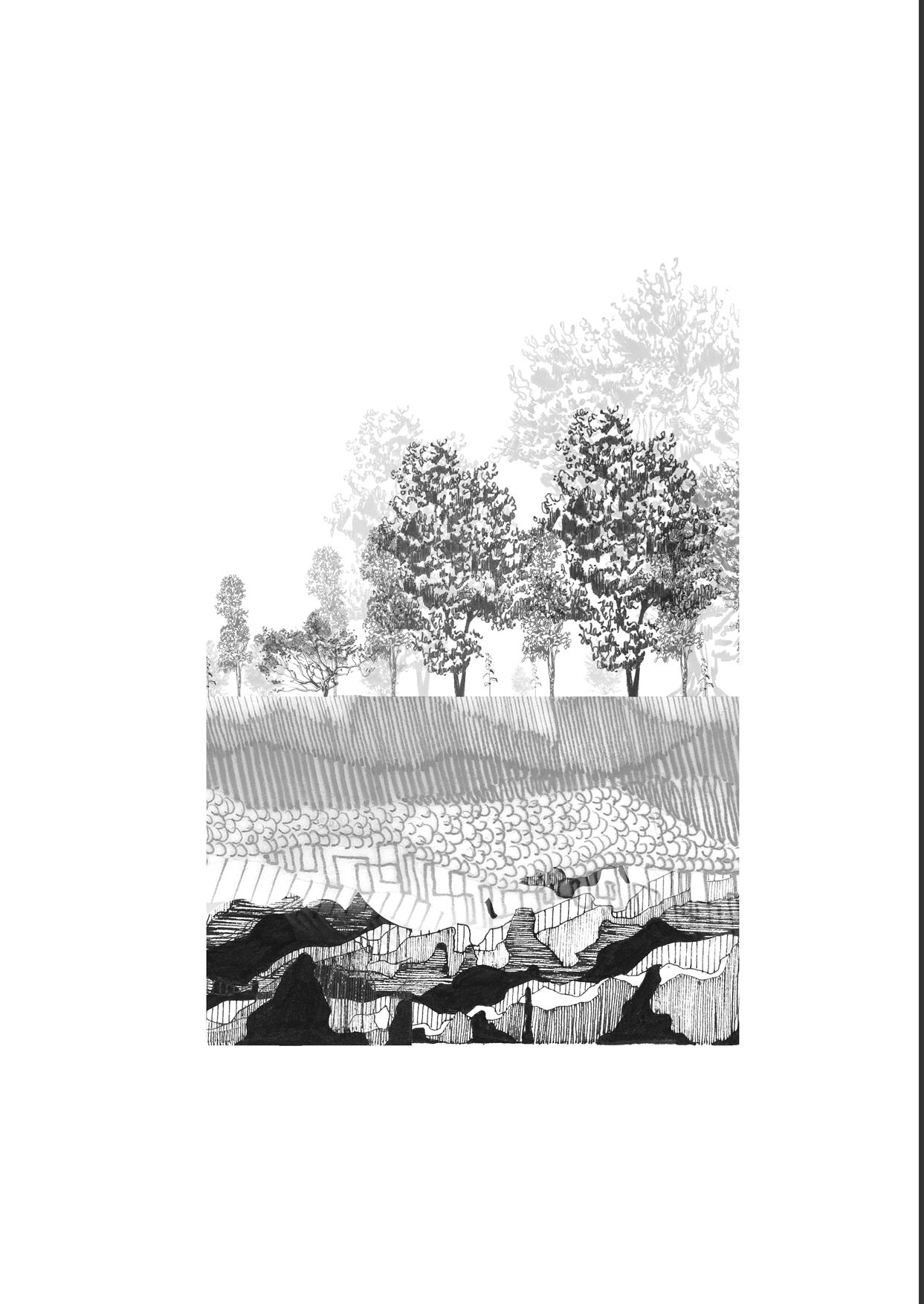

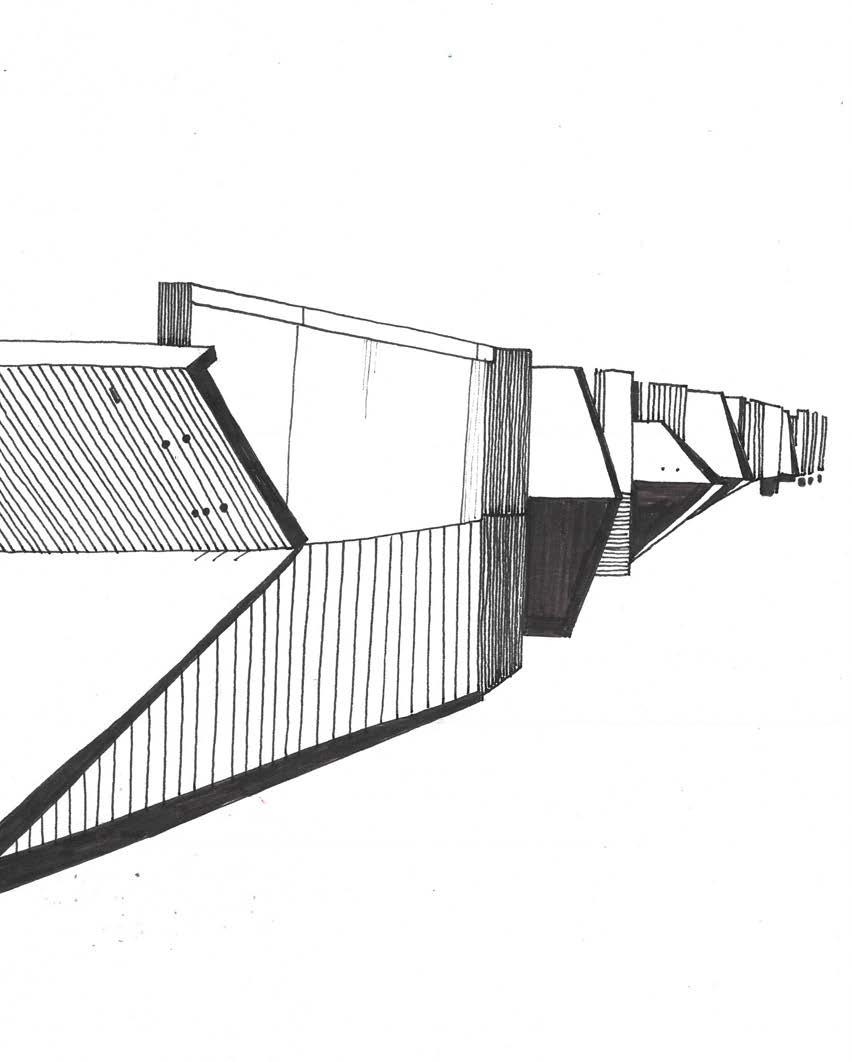

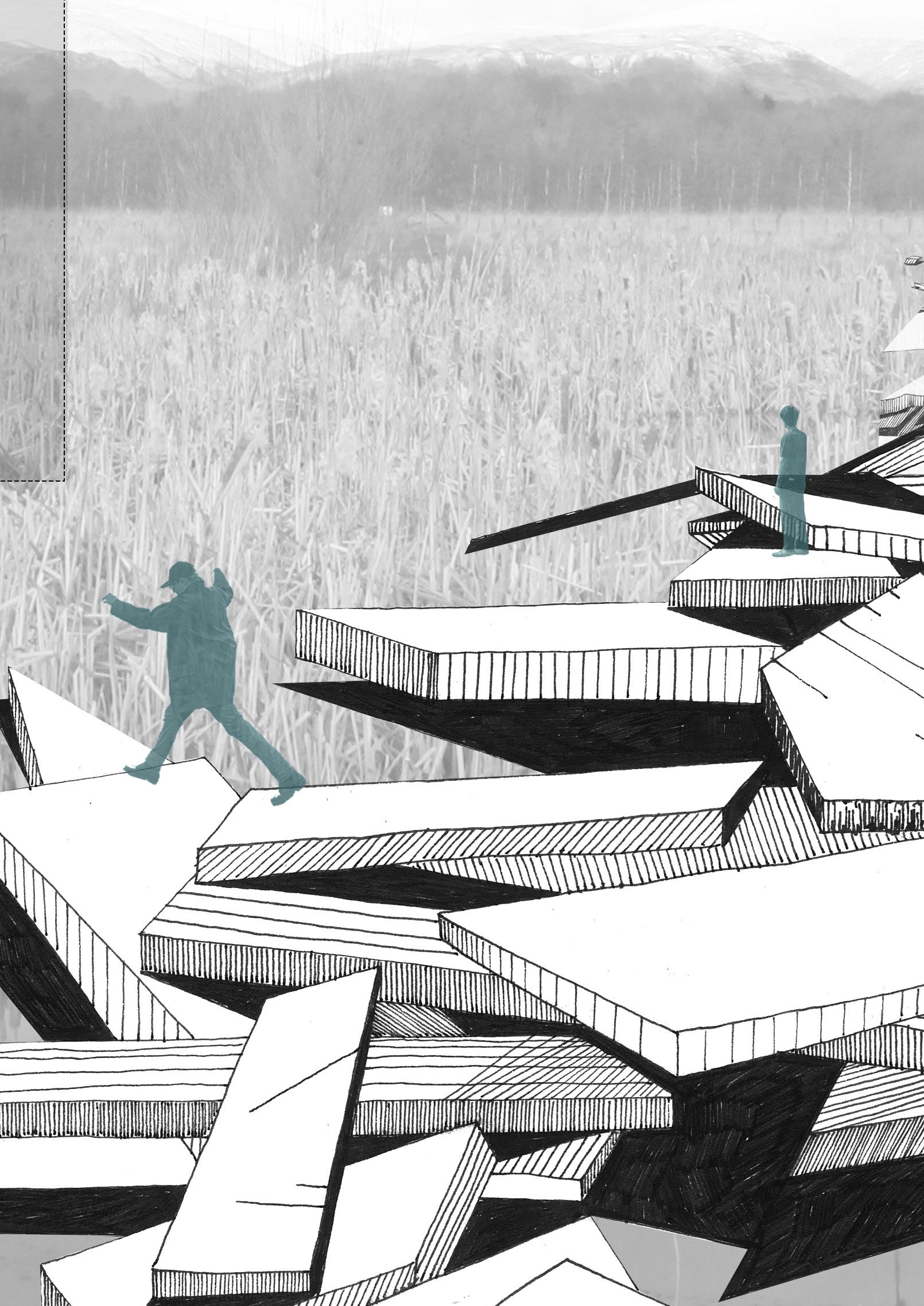

DETAIL / Walkway of Evolution, Erosion, and Erratic

The materiality and form of the walkway in the Sauðárdalur Valley is one that will continue to extend and erode in tandem with the ruination of the dam itself. What begins as a large-scale installation of concrete slabs will be allowed to move and gradually disintegrate according to the force and flow of the waters travelling down from the resevoir. The result is a dynamic walkway that leads backwards through time, through ruination itself, to the crumbling remains of the monumental Sauðárdalsstífla.

54

55

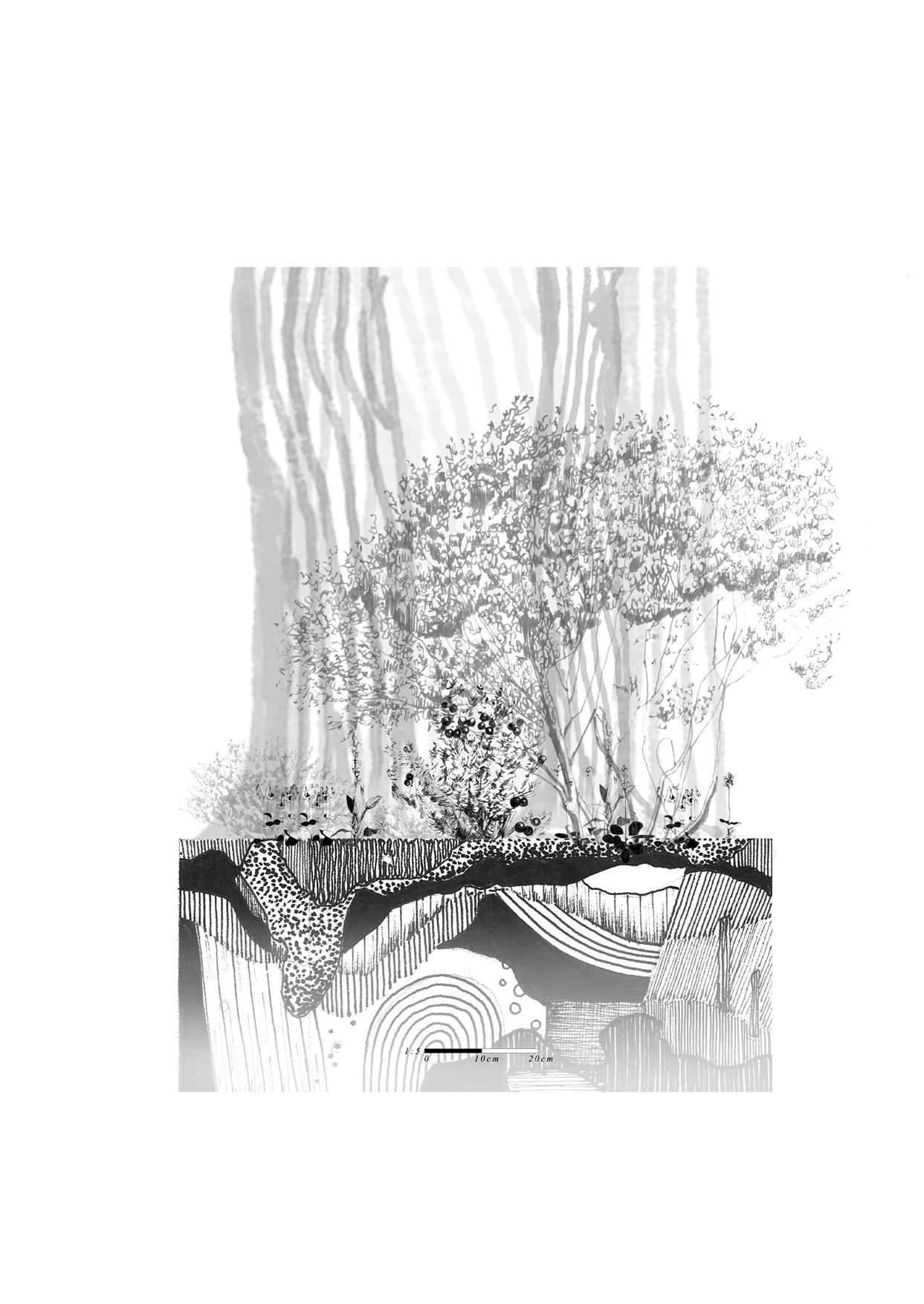

MORE-THAN-HUMAN FUTURES / WETLAND ECOLOGIES

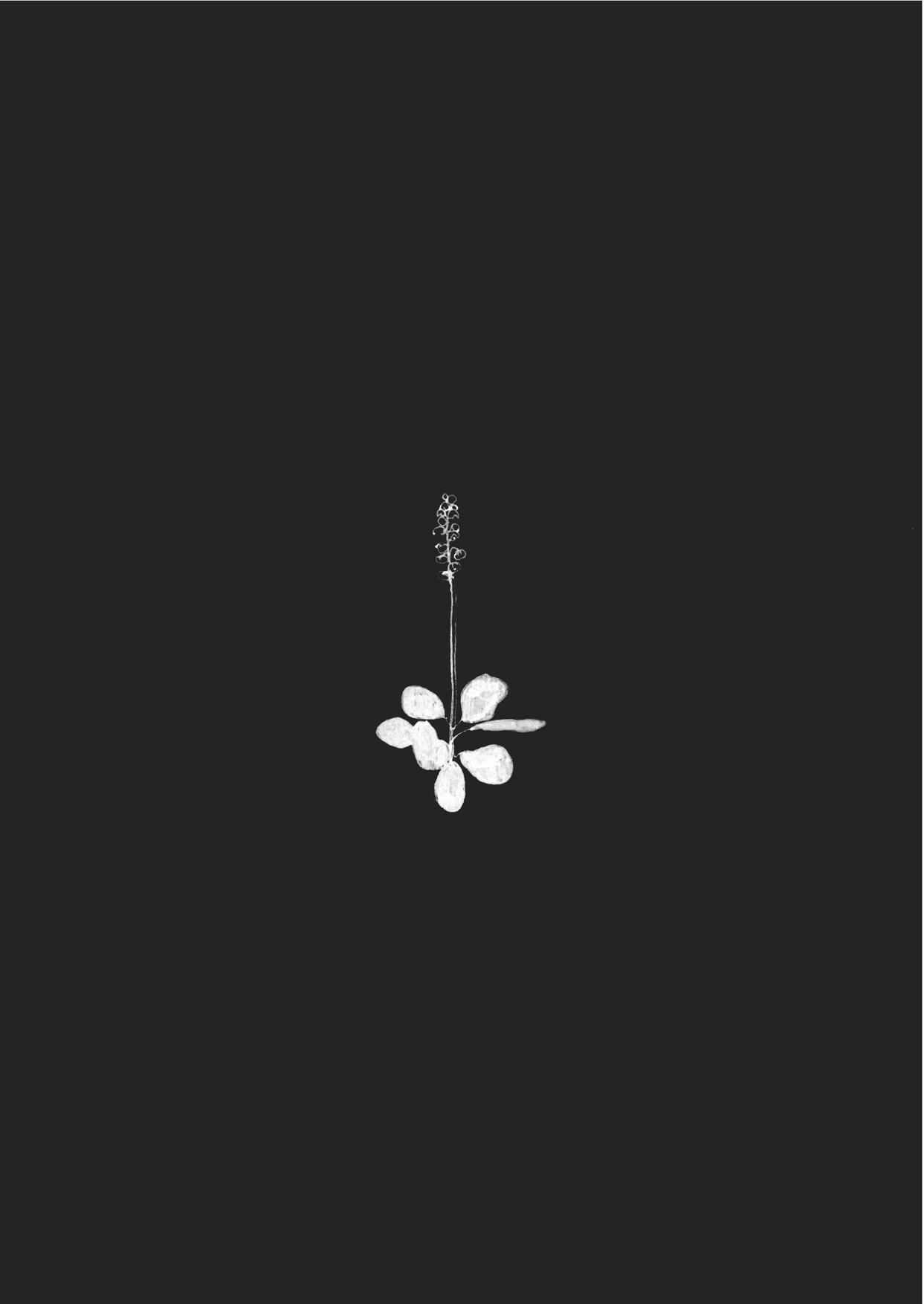

Visualising the future ruins of the Sauðárdalur as a haven for wildlife: a network of braided river channels and streams, pools, and bogs that will encourage the regeneration of wetland ecologies that once proliferated the region. The influx of sediment and glacial flour following the deconstruction of the dam should settle into the riverbeds, providing a richly nutritious substrate to support the growth of native wetland sepcies such as the common cottongrass, arctic willow, or lessertwayblade. Nooks and crevices within the cracked and eroded concrete create a valuable habitat for rarer microecologies such as the fountain apple moss of racomitrium. It is through this gradual process of renaturalisation and ecological succession that the project aims to re-establish a lively yet resilient wetland landscape and ecosystem.

56

57

For the complete archival collection of Future Wetland Ecologies, see Appendix, 78.

58

59

60

MORE-THAN-HUMAN FUTURES / AVIAN ECOLOGIES

Wetlands are equally some of the most valuable, and most threatened, habitats in the world. Highly dynamic in nature, they represent an incredibly intricate ecosystem which plays host to a huge diersity of wildlife. The conservation and creation of wetlands for birds in particular - whether acting as important resting areas for migrating birds, or breeding grounds for water birds - is of great importance during the biodiversity crisis we find ourselves in today9. More than that, as the climate continues to destabilse, and glacial melt accelerates, we may find ourselves living in an era of increasing freshwater scarcity. Through the renaturalisation of this wetland landscape, not only is the memory of the meltwater from the glacier preserved, it in turn restores life to this barren landscape. In the coming decades and centuries, we might hope to see the return and multiplication of Whimbrels, Golden plovers, Dunlins and Greylag geese to name a few.

61 9“Wetlands,” WWT, accessed February 28 2023, https://www.wwt.org.uk/discover-wetlands/wetlands/

62

For the complete archival collection of Future Wetland Ecologies, see Appendix, 78.

63

HUMAN FUTURES / THE EXPERIENTIAL

The human experience of being in the ruinous landscape of the Sauðárdalur will be complex and multi-faceted. A contrary place of both memorialisation and the continual manifestation of futures, of creation and destruction, of actively archiving and preserving information whilst allowing dynamic landscape process to unfold unfettered, a place teeming with life juxtaposed with implications of death (the glacier) and destruction (the dam). It is the ambition of the project that the numerous layers to the experiential dimension of the landscape will encourage a varied, creative, and spontaneous use of the ruins. Some may come to reflect, some to explore, observe, play, or create. The space - acting as a contemplation on glacial histories, transitions, and futures - will be a different experience not only for each person that visits, but each year, season, or occasion of their visit.

64

65

HUMAN FUTURES / ARTISTS RESIDENCE 2100

An integral component of the proposed interventions at the Sauðárdalur site is the implementation of an Artists Residency programme, as a continuation of the explorations in atmospheric printmaking of my initial design hypothesis. Whilst reusing the glasshouse constructions of my first semester, the narrative of the project expands - from printmkaing with melting glacial ice to create an atmopsheric archive - to invite artists to record the transitional processes of the Vatnajökull as it becomes liquid. The result, the gradual yet continual accumulation of a physical Future Archive for the Vatnajökull Botanical Park, as well as the creation of new rituals and ceremonies to draw people back to this hidden landscape.

66

67

For the full Artists Residence Pamphlet, see Appendix, 101.

68

69

Chapter Three

THE EXPERIMENTAL FOREST LABORATORIES OF SKAFTAFELL

70

71

Existing birch forest

Existing water networks

Existing contours

Existing transport networks

Existing conditions of the Skaftafell hillside

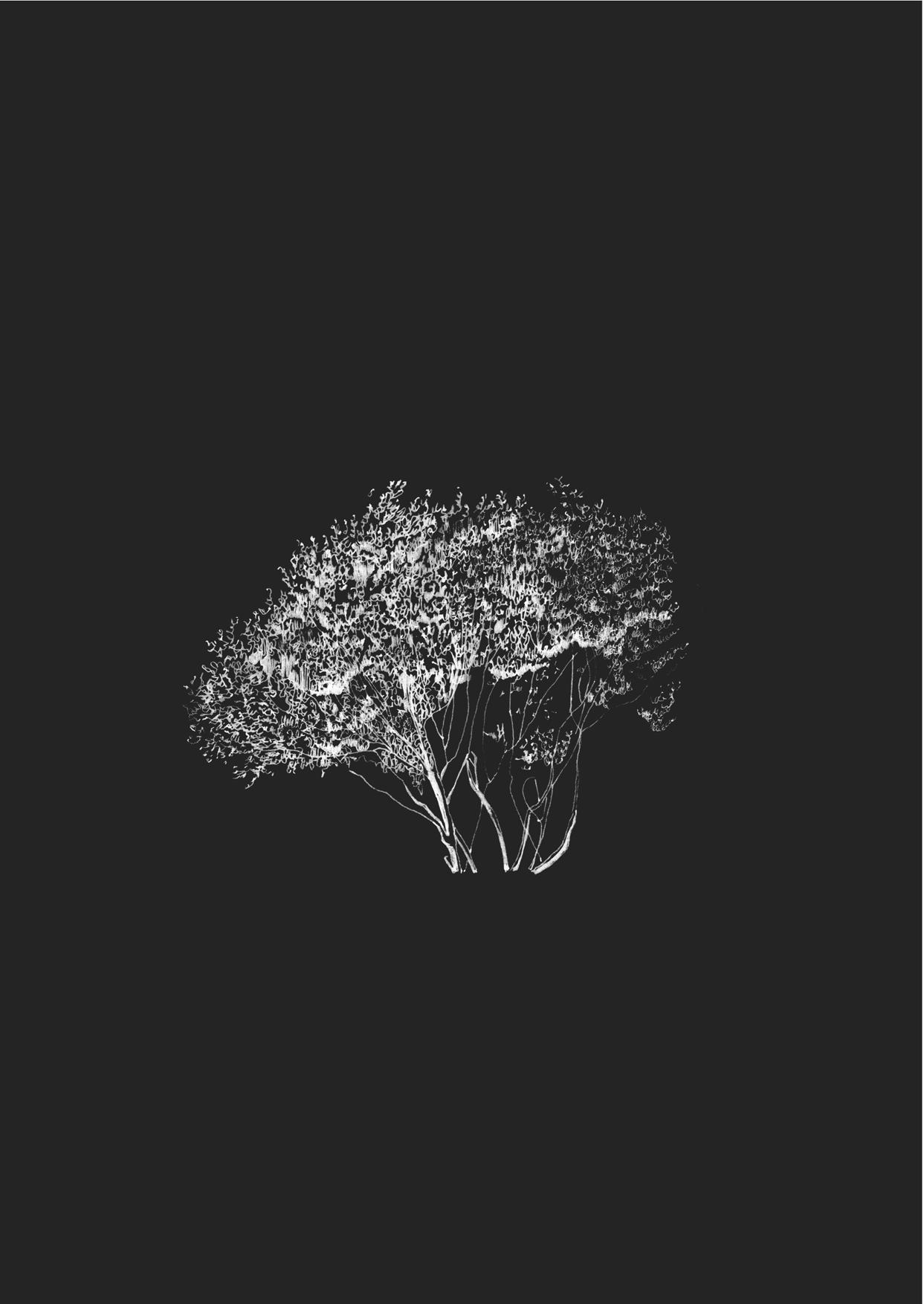

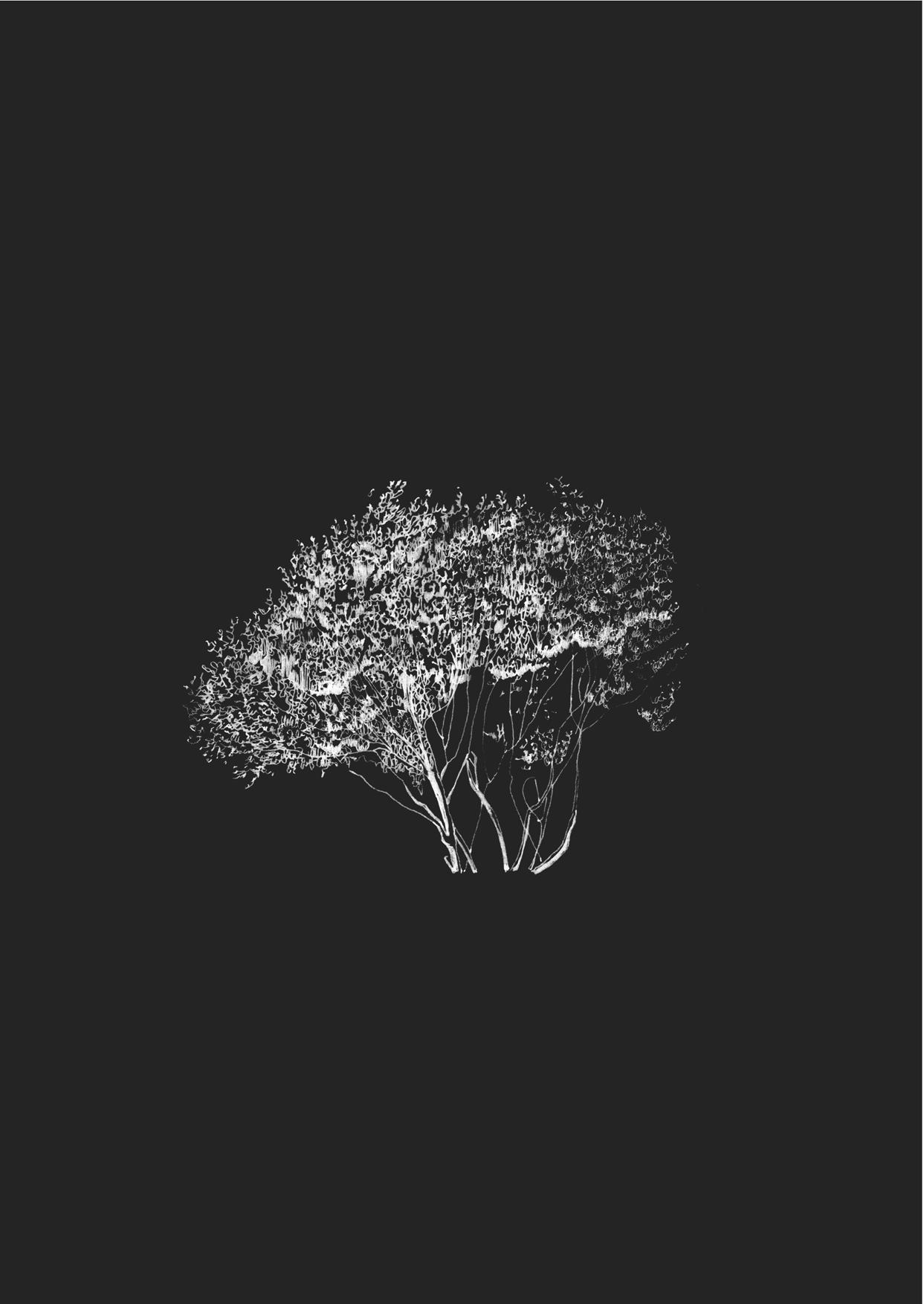

Skaftafell, and the surrounding Skeiðarársandur outwash plain, is a unique and wildly dynamic landscape in the south east of Iceland. Although it is home to one of the largest areas of birchwood in Iceland, due to the instability of the landscape, a history of prolific glacial surges, overgrazing, and generally harsh climatic conditions, these Betula nana rarely grow more than 2m tall.. With the frequency and intensity of jökaulhaups predicted to increase as the glacier melts, the landscape will grow more unstable than ever, creating ever harsher conditions for possible regeneration or maturation of the forest.

72

73

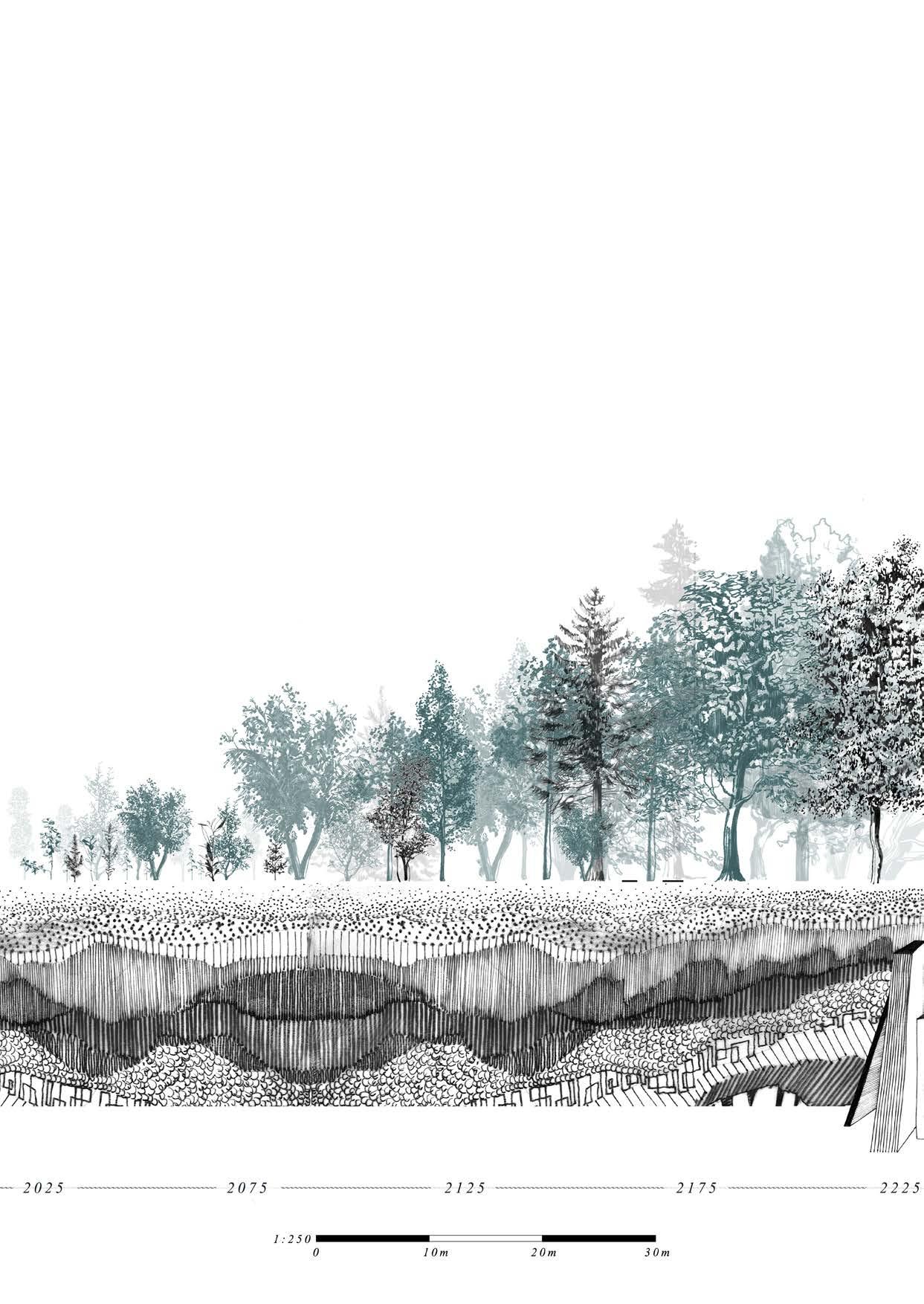

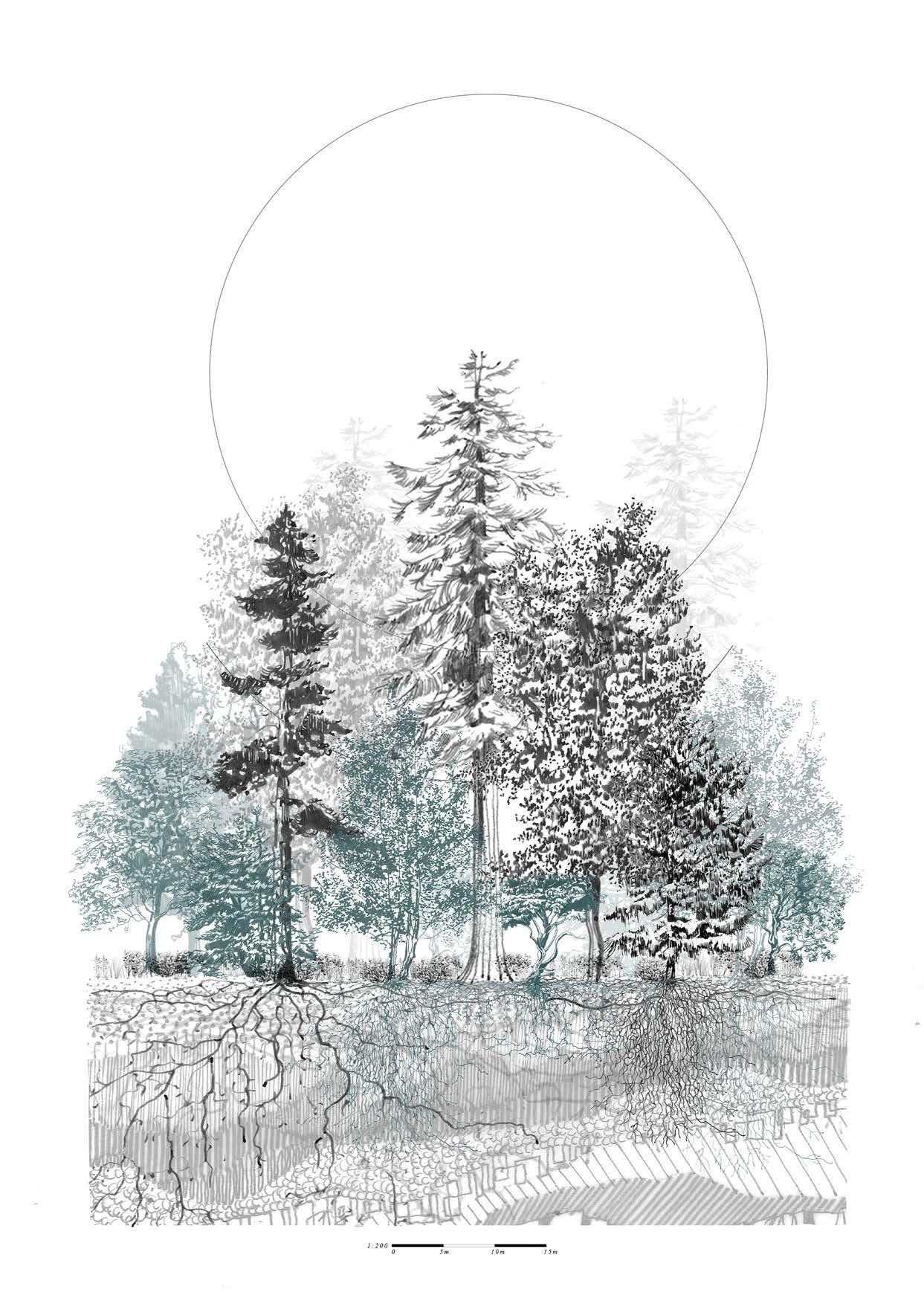

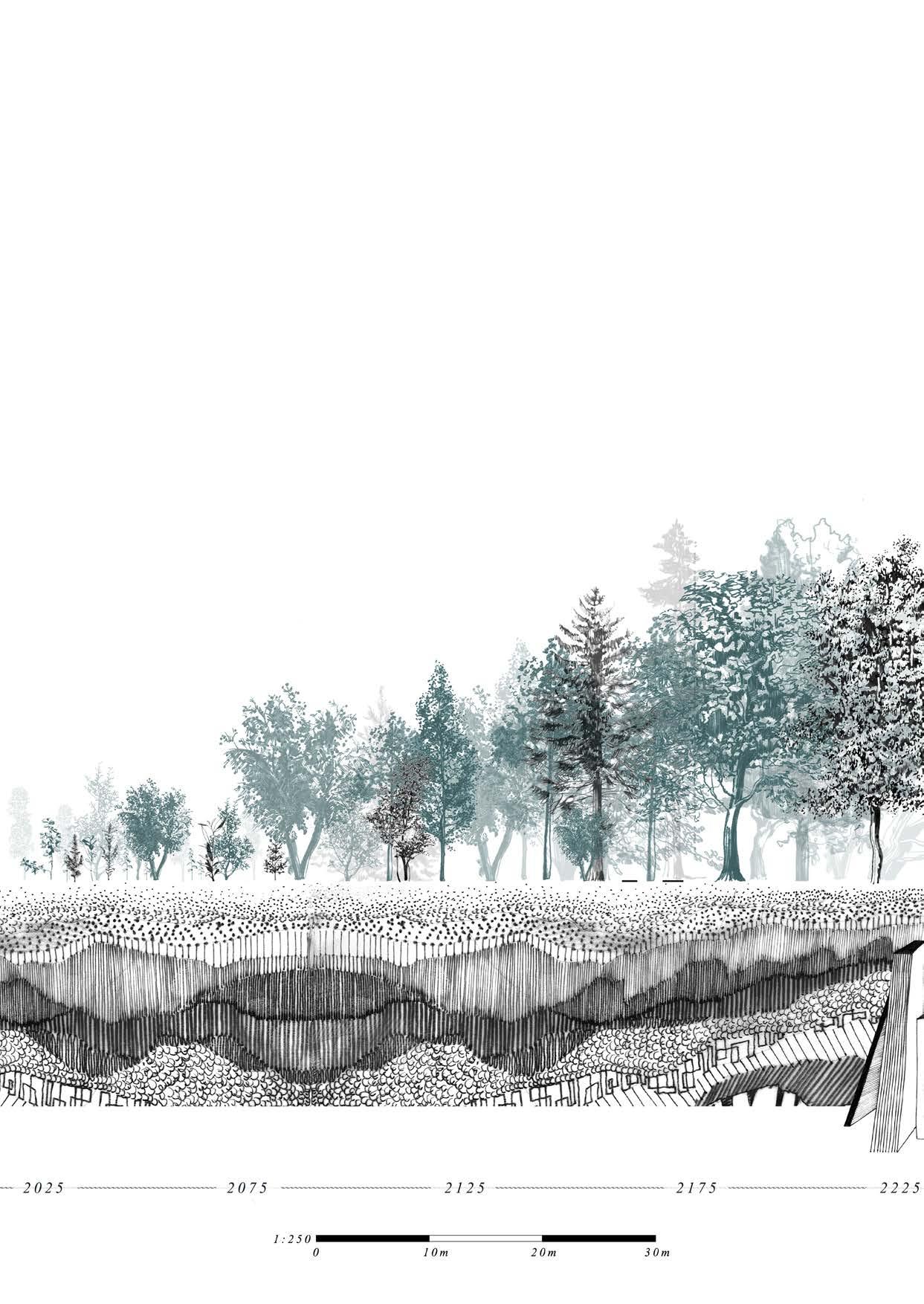

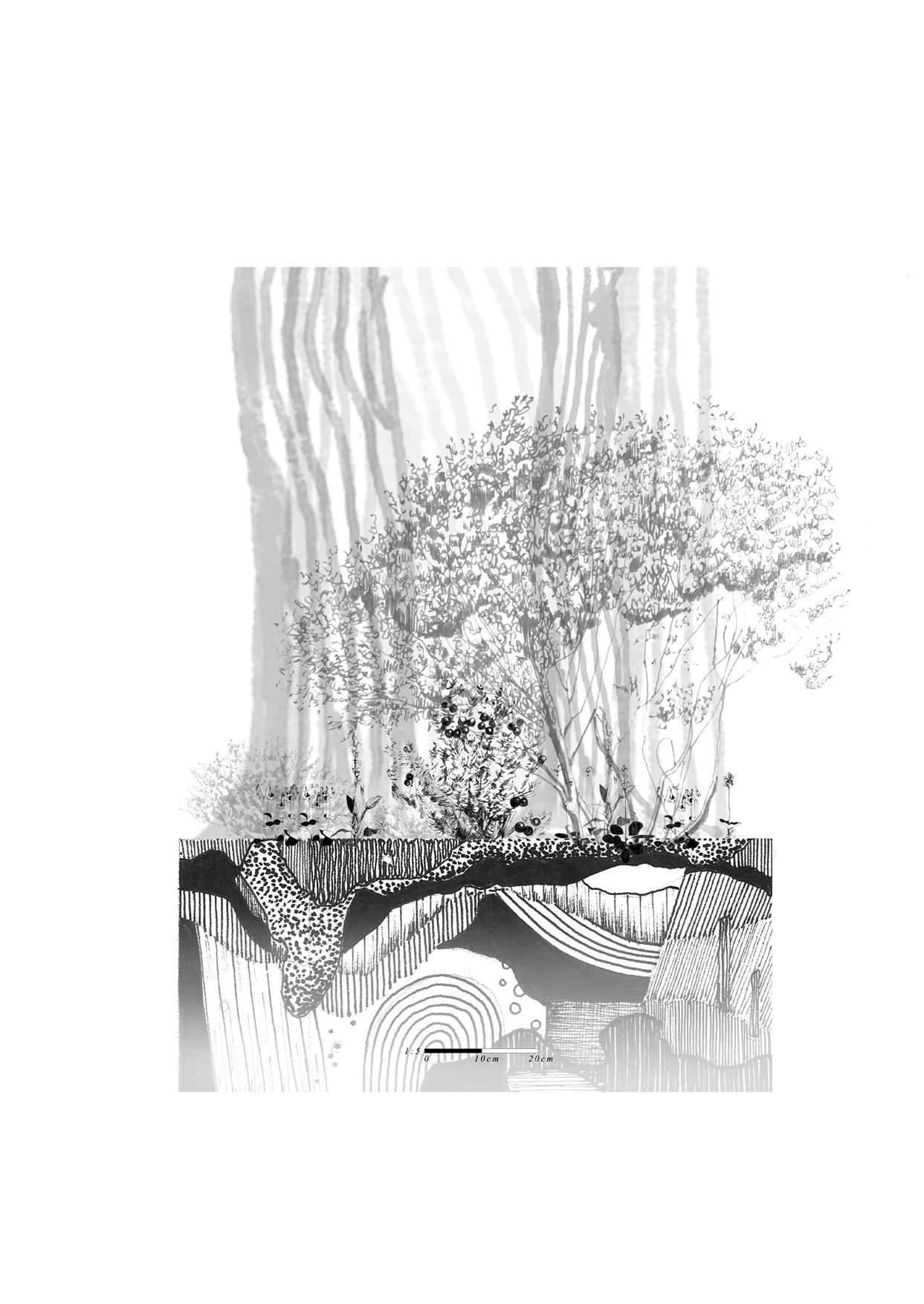

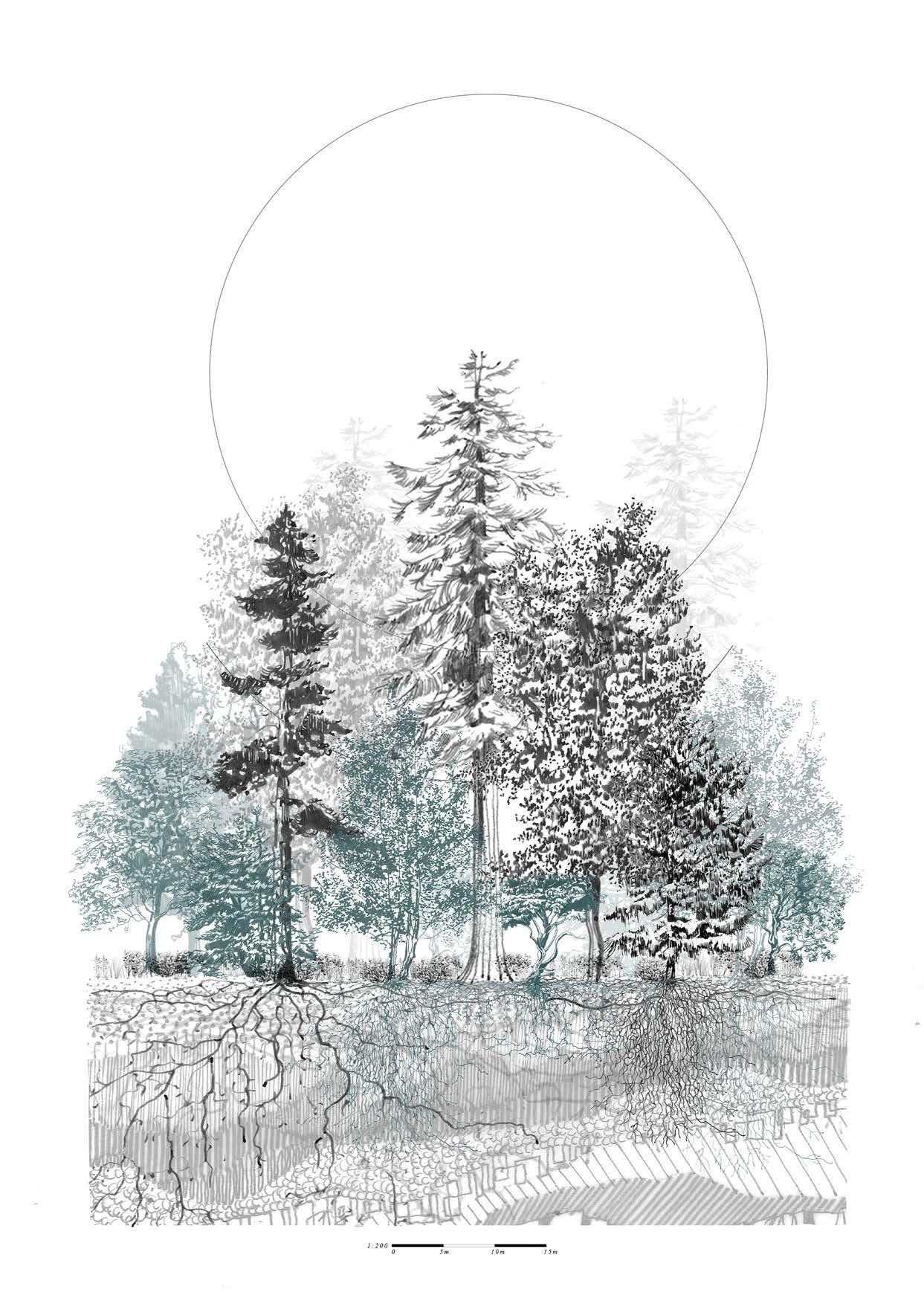

Proposal for the Experimental Forest Laboratories, and Future Ancient Woodlands of Skaftafell

The experimental forest laboratories the project proposes for the site at Skaftafell represent efforts to establish ecological resilience in times of deeply uncertain climatic futures, and stability in an everunstable landscape. Drawing inspiration from Alnrp’s ‘Landscape Laboratory’, which placed emphasis on research and experimentation within the field of urban woodland design and implementation, the experimental forests are an attempt to demonstrate what is possible in efforts of reforestation and conservation. Oftentimes, the ecological narrative can be dominated by ‘minimal intervention’ or the reintroduction of native species. The project, as counter-intuitive as it may seem, dares to invert this ethos, proposing radical intervention, heavy maintenance, and the introduction of global species to an otherwise-sparse ecosystem.

The forest networks will be interconnected by walkways to allow visitors to move between sites of distinct atmospheres and ecologies. Whilst each laboratory will be highly individual in its methods of design, maintenance regime, and stewardship; they are unified conceptually by the common narratives of landscape archives, ecological resilience, and the creation of [future] ancient woodlands.

74

75

Landscape Archive / Proposal for a [Future] Ancient

BOREAL ICELANDIC BIRCHWOOD

76

77

78

The preservation of the existing birch forest upon the plains of the Skeiðarársandur, and hillsides of Skaftafell, is integral to the reforestation movement in contemporary Iceland, with the potential to develop into Iceland’s biggest mature birch forest in the absence of catastrophic climate events. Whilst the afforestation movement in the 20th century largely focused on enclosing areas of birch woodland to protect from overgrazing during the summer months10; my proposal, by contrast, seeks to extend these efforts through time and space, through the elevation of the existing forest to develop into Iceland’s first Ancient Birchwood. The laboratory itself will be built up into an island of sorts, in constructed soils utilising displaced materials from the first site at Sauðárdalur. The form of the laboratory is particularly unique, its design derived from the shapes of existing dwarf birch forests of the Skeiðarársandur. This is not only a reference to the origins of the forest in future history, but another facet to the archive narrative, as a preservation of past landscape forms. It is the ambition that, through the physical elevation of the trees, as well as rigorous human management, the emergent woodland will be afforded protection from the elements and animals alike. This provides valuable security, space, and time to develop into an Ancient forest for the future, bringing with it ecological stability and resilience.

For the complete Icelandic Birchwood Inventory , see Appendix, 36.

10 “Forestry in a treeless land 2017,” Icelandic Forest Service,

March

2023, https://www.skogur.is/static/files/2017/ Forestry_in_treeless_land_BKL_210x260mm.pdf

accessed

17

79

80

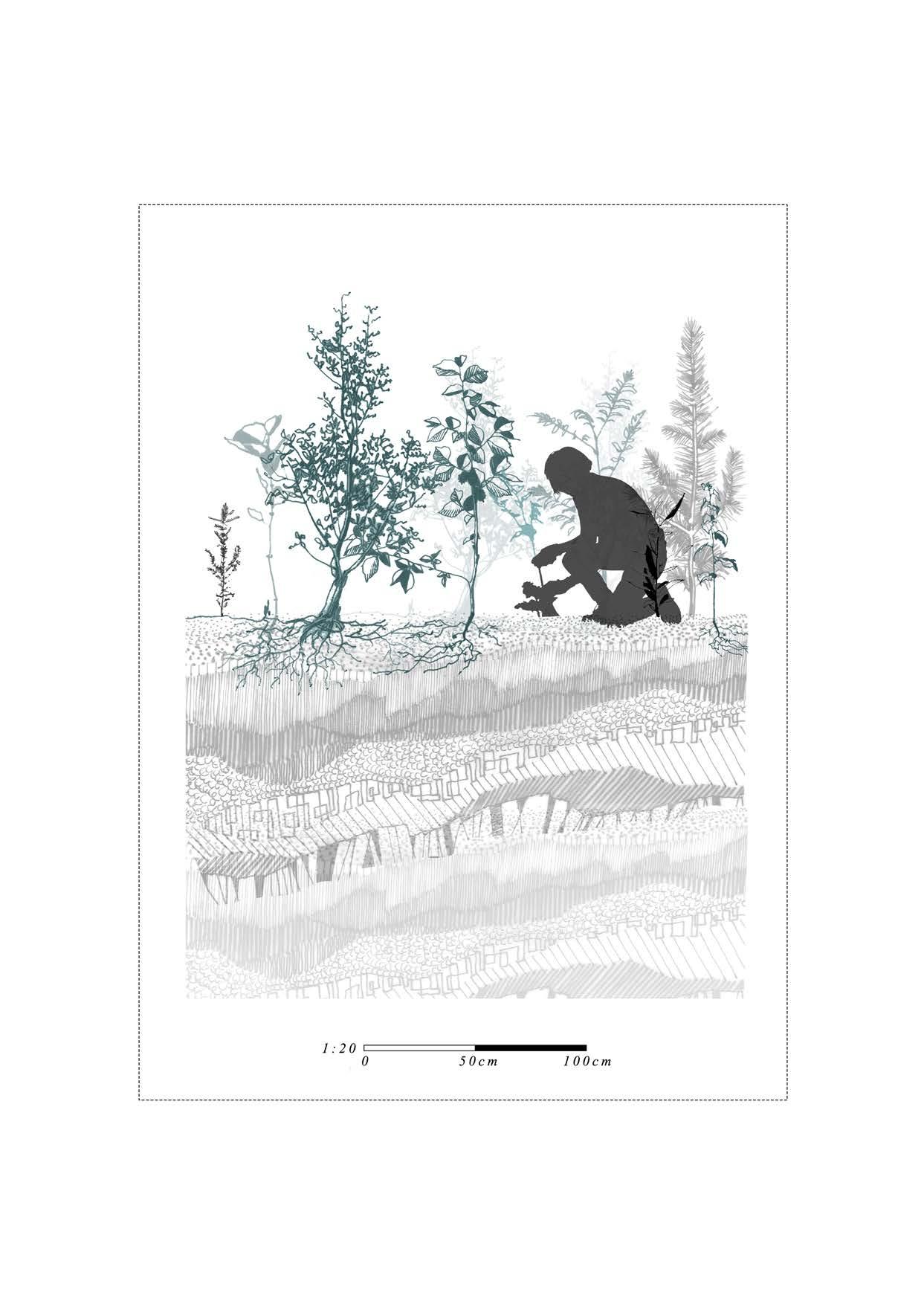

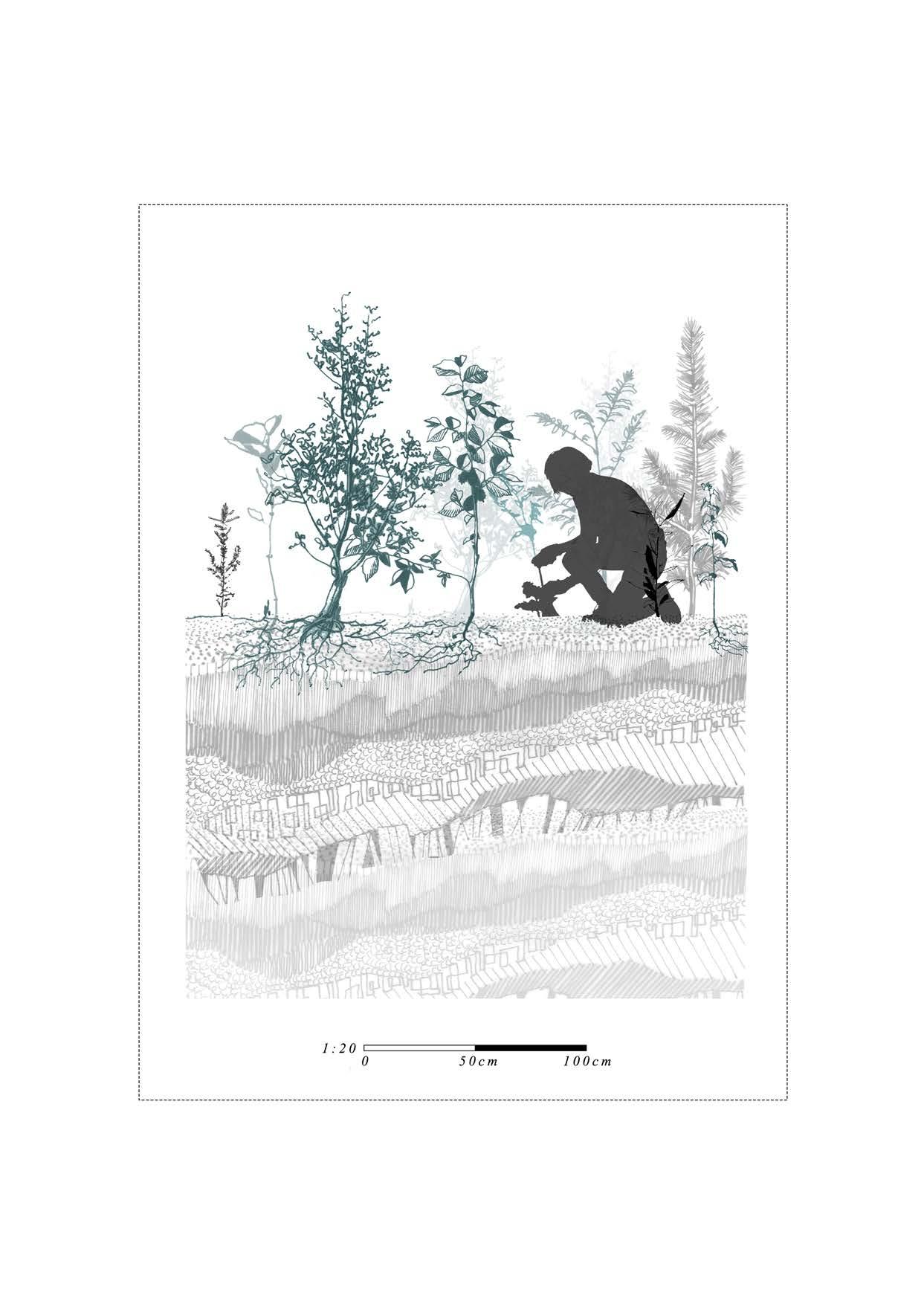

PHASE ONE / CONSTRUCTION

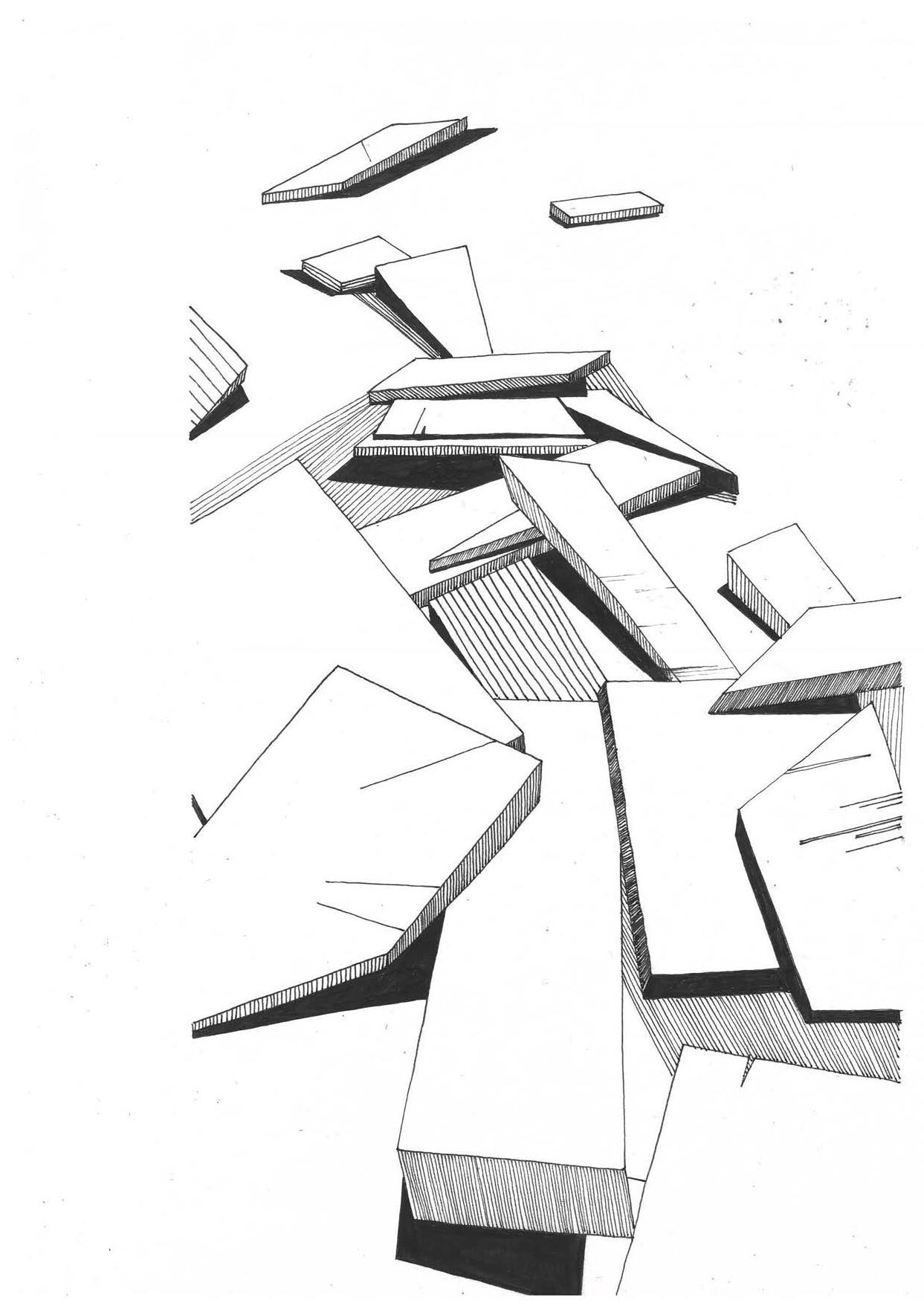

Soils and Structures. Each unique forest laboratory ‘island’ is built up to 5m above the existing ground level, with an even-level surface on the top, using a combination of local materials including those reclaimed from the deconstruction of the Sauðárdalsstífla dam. The idea being that each site within the archive, whilst dramatically different from one another, may be united by a sense of shared materiality.

Concrete, basalt and sediment from the Sauðárdalur Valley site will be used in the construction of soils for the forest laboratories. In line with the idea of designs of distrubance, and recognition that it may be through such disruption (e.g. of soils and structures) that new life is stimulated. The novel substrates constructed will encourage new forms of growth, colonisation and succession, while the height of the structures afford a sense of stablity to an otherwise highly unstable and unpredictable landscape - permitting each forest to grow, mature, and grow old in the safety of the landscape laboratory.

81

PHASE ONE / CONSTRUCTION

The surrounding structure of each laboratory takes its form from an histroical forest, as a form of replication of landscapes lost. Concrete from the deconstruction of the Sauðárdalsstífla dam will be used to encase the constructed soils. In some cases these pieces will be arranged regularly, in strong straight lines and monumental panels. In others, they will be piled upon one another, leaning, slanted and cracked, in dialogue with the narrative of ruination running through the design interventions at the Sauðárdalur.

82

83

84

Angelica

Smooth-stalked meadow grass

Nootka lupine

Wood cranesbill

Birch saplings

PHASE TWO / IMPLEMENTATION, SUCCESSION

Betula pubescens and Betula nana, which currently colonise the hillside at Skaftafell, have a tendency to ‘sprint’ uphill, followed by their companion species to suceed in their wake. For this reason, the design of the Icelandic Birchwood laboratory includes a gradianted slope the opens out from the laboratory back into the hillside. This encourages the surrounding Birch to follow their natural patterns of succession, as well as providing them with valuable higher ground in which to seek refuge from the prolific jökaulhaups which have plagued the nearby Skeiðarársandur over the last century, and which are expected to become more frequent and unpredictable as the climate continues to destabilise. At this stage, any birch trees that were displaced during the construction process can be re-planted, accelerating the intial stages of ecological succession.

Following on from the construction of the site, transplantation, and the initial succession of local birch, we might expect to see more species begin to colonise as the site settles and stabilises. Valerian, stone brambles, nootka lupines might emerge, as well as the highly unusual black elfin saddle fungi that thrives in Birchwoods. Birds such as the Icelandic wren, redpoll, and snipe may begin to migrate, all contributing to an emergent, thriving ecosystem.

85

Valerian

For the legend / complete archival collection of Birchwood Ecologies, see Appendix, 60.

86

87

88

PHASE THREE / MATURITY, STEWARDSHIP, EXPERIENCE

As the years pass, and the Birchwood begins to establish and mature, it will be the task of the foresters overseeing the project to remove any unwanted scrub or shoots that may opoortunistically colonise the ground. The purpose of this is an exercise in maintaining the woodland as aunique Birchwood-oriented ecosystem that will develop to ancient age. Any species that might threaten to invade, outcompete, succeed, or otherwise disrupt the balance of this ecosystem will be relocated to the a separate laboratory - the Arboretumwhere natural processes of succession will be allowed to unfold in a more wild way.

As the Birchwood develops, regenerates, and matures in the coming decades and centuries, it will offer visitors the richly unique experience of walking through Iceland’s first Ancient Birch Forest. It might speak to some through evocations of cultural memory, and of the denselyforested land that Iceland once was, long ago. To others, it might demonstrate hope for the future possibilities of re-forestation as the landscape undergoes immeasurable change. In the wake of glacial melt, the transition and memory of the landscape can be measured instead in the rings of the trees, seen in the rough edges of the bark, heard through the birdsong that dances between the leaves. It is a landscape of both the past and the future of Iceland.

89

TRANSECT THROUGH TIME 90

91

Landscape Archive / Proposal for a [Future] Ancient

BOREAL CALEDONIAN PINEWOOD

92

93

94

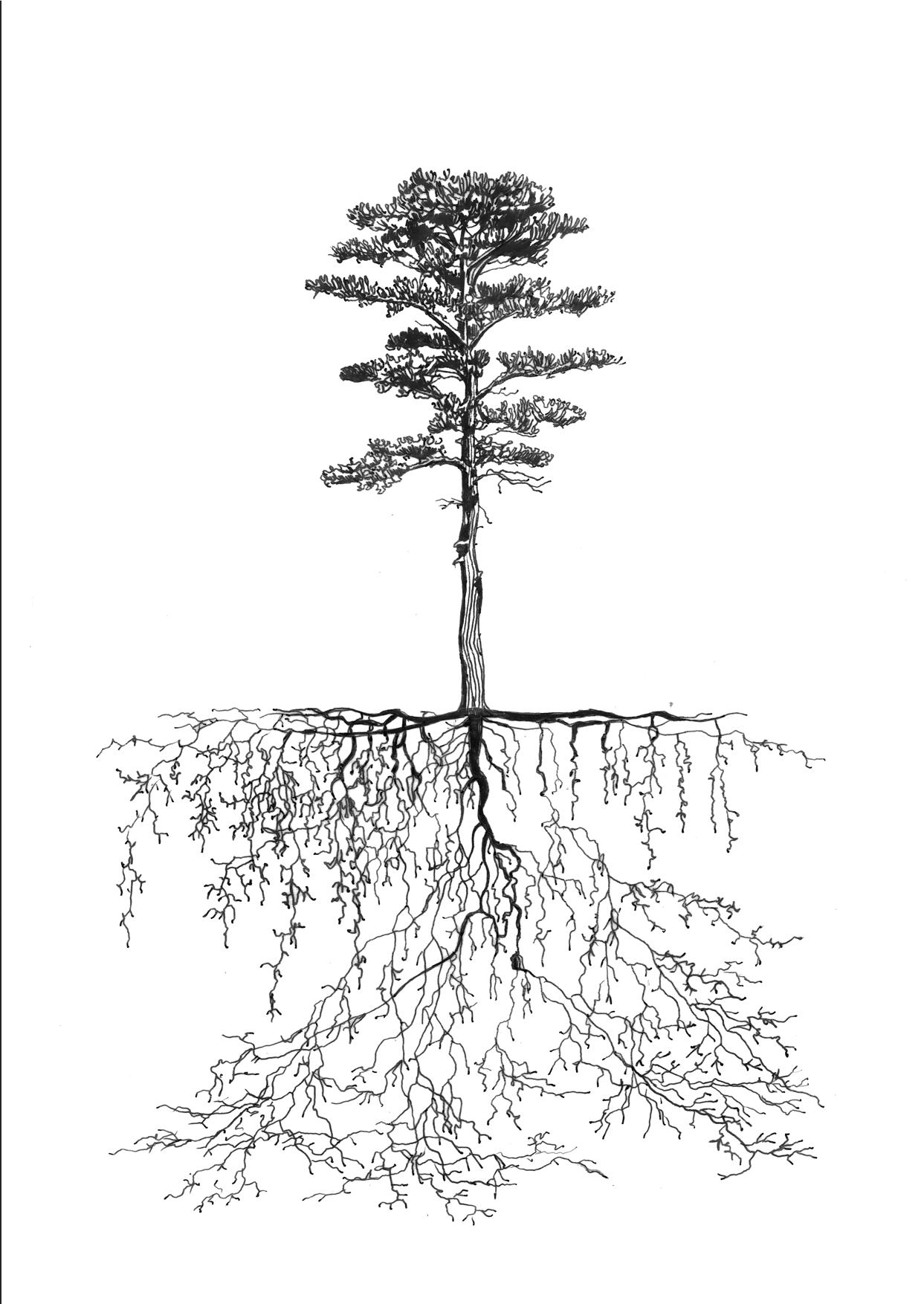

Since the very beginnings of my design explorations in the realm of the Vatnajökull, I had positioned the postglacial landscapes of Scotland - such as the Pentland Hills and the Cairngorms - in dialogue with Iceland. As a way of relating to this new and faraway place, but also as a study of how Iceland’s speculative postglacial futures might unfold. How might the landscape take shape? Which ecologies might emerge? It later transpired, during the process of scoring the landscape’s projected atmopsheric change, that I began to realise just how fitting such a comparison might be. With a forecasted increase of 8’C over the next two hundred years, the future climate of the Vatnajökull is forecasted to fall almost perfectly in line with that of the contemporary Scottish Highlands. Furthermore, in a troubling parallel, where a mere 1% of trees remain of a historically forsted Iceland11, it is equally just 1% of the ancient Caledonian Pinewood that once blanketed Scotland endures today.12

Whilst, certainly, there are valuable landscapes and atmopsheres being lost to the world as the glacier recedes, there are equally conditions emerging that may find themselves threatened elsewhere in the world. How might we shift the narrative, from one of loss, to one of hope? As the ancient Caledonian Pinewoods of Scotland become fewer and further between, under increasing threat from global warming and human action, the emergent postglacial landscape of Iceland might offer conditions in which they have space to thrive.

The [Future] Ancient Caledonian Pinewood of my proposal follows this line of reasoning. It is an experiment in establishing global ecological resilience in times of increasingly uncertain futures. It acts as an archive of atmospheres and landscapes lost to our actions, and in-actions. It is my belief that by integrating unlikely companions, such Icelandic Birchwood and Caledonian Pinewood, more-than-human species will engage in an act of active collaboration to strengthen both the resilience of Iceland’s fragile ecosystem, and our planet as a whole. This experimental proposition for the future of forestry and reforestation takes in the global view, taking unprecedented change as an opportunity for preservation, remediation, and resilience.

11“History of Forests in Iceland,” Icelandic Forest Service, accessed February 18, 2023, https://www.skogur.is/en/forestry/forestryin-a-treeless-land/history-of-forests-in-iceland.

12“Caledonian Pinewood Recovery,” Trees for Life, accessed March 1 2023, https://treesforlife.org.uk/about-us/caledonianpinewood-recovery.

For the complete Caledonian Pinewood Inventory, see Appendix, 26. 95

PHASE ONE / CONSTRUCTION

In addition to the construction of soils, and the surrounding post-industrial structure, the Caledonian Pinewood laboratory proposes another re-use of the concrete materials: a set of wide, winding steps leading through a valley of birch trees, edging along the towering external walls of the laboratory and leading into the forest itself. Whilst the majority of paths are constructed to be either flat or gently sloped to allow universal access to the forests, the implentation of these steps provide a more challenging ascent for any hillwalkers exploring the slopes. More than this, it offers the unique atmospheric experience of transitioning between native birch hillside, through an imposing valley, into a foreign world itself: Ancient Caledonian Pinewood.

96

97

0.5m 1.5m

PHASE TWO / TRANSPLANTATION

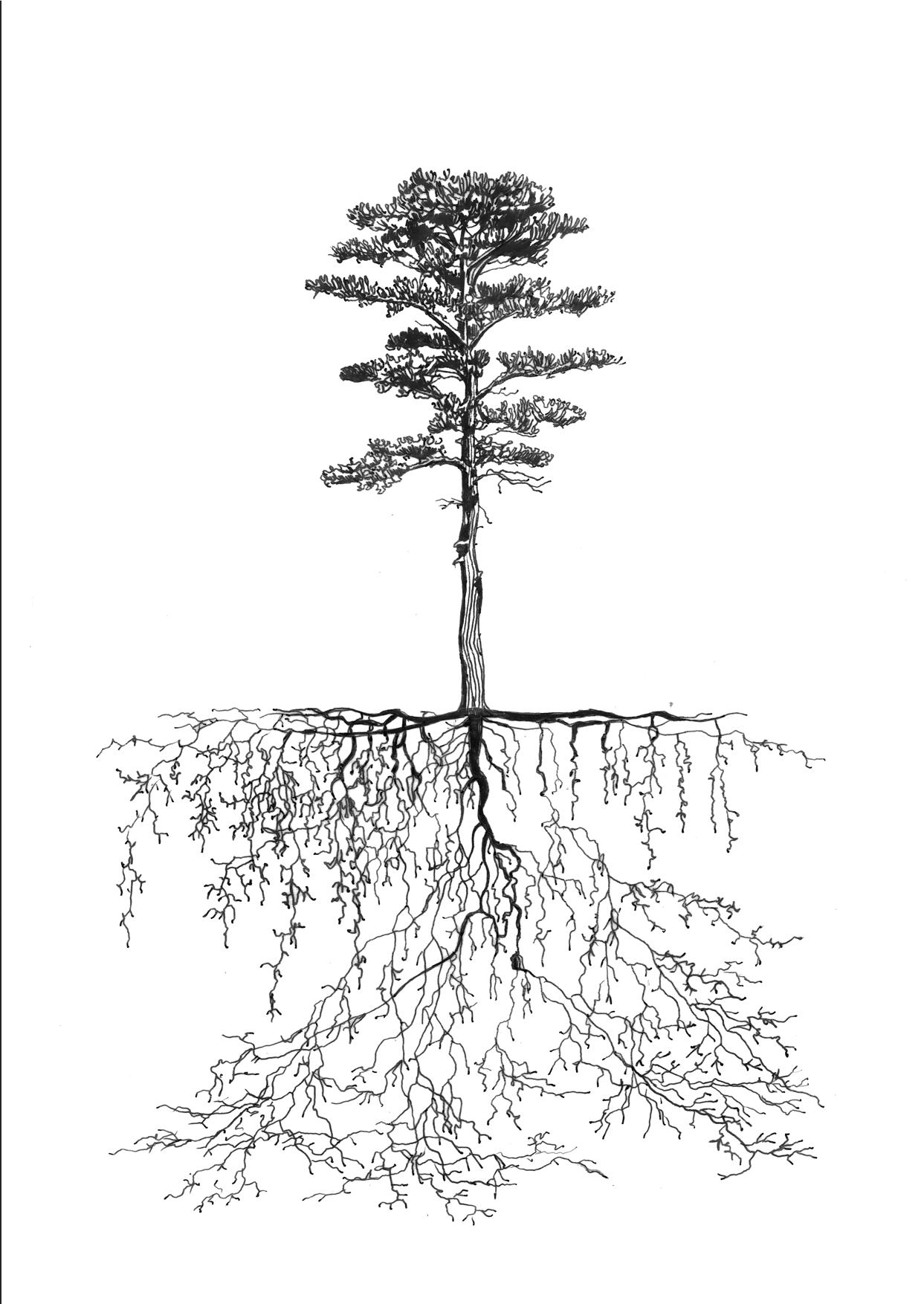

Upon completion of the construction stage for the laboratory, bareroot Scots Pine trees will be transplanted in the following spring once they reach a height of 80cm. By this stage in their development, they should be hardy enough to withstand the colder Icelandic winters, but it will be at the discretion of the foresters caring for the forest if they should be protected with a layer of mulch in the intial years. During this time, they will grow quickly, soon coming to establish strong root systems that, in time, will entwine to form the comlpex and intricate network that supports the life of all the forest.

98

99

100

Eared willow

Blaeberry

Bell heather

Crowberry

PHASE THREE / ECOLOGICAL SUCCESSION AND ESTABLISHMENT

In the intial stages of succession within the Pinewood, we might hope to see the emergence of characteristic species that occur nowhere else. Blaeberry and bell heather, twinflower and creeping lady’s tresses. Potentially the emergence of rare species of tooth fungi such as the blue tooth, or networks of wood hedgehog fungi that grow in symbiosis with the trees.

Whilst in colder, drier climates, such as the east coast of Scotland, Scot’s Pine dominates the tree canopy; milder or more humid environments can result in a more diverse collection of species.13 As the climate crisis intensifies, we might anticipate the colonisation of tree species including rowan, alder, juniper, birch, holly, and hazel. In efforts to preserve this landscape as close to a native Caledonian Pinewood as possible, the project proposes to have any emergent saplings relocated through transplantation into the Arboretum.

101 13”Caledonian Pinewood Recovery,” Trees for Life, accessed February 12 2023, https://treesforlife.org.uk/ about-us/caledonian-pinewood-recovery.

For the legend / complete archival collection of Caledonian Pinewood Ecologies, see Appendix, 41.

102

103

PHASE FOUR / COLONISATION AND MIGRATION

The unique habitat of the Caledonian Pinewoods provide refuge for an abundance of rare and specialised species. As the forest matures, and the climate shifts, we might hope to see the migration of certain species of bird, invertebrates, and insects alongside the increasing ecological resilience of the forest. Black grouse, red squirrels and pine martens might find a home here, as well as endangered pine hoverfly species that feed on old or deadwood.

104

105

intermediate wintergreen lesser twayblade twinflower Eared willow Bell heather

106

For the legend / complete archival collection of Future Tree Species, see Appendix, 12. 107

108

PHASE FIVE / FOREST MATURITY, EXPERIENTIAL DIMENSION

Almost two hundred years on from the initial transplantation phase, the unique experience of the Ancient Caledionian Pinewood, so far removed from its native homeland, is recreated in an island of concrete, jutting out bizarrely from the hillside of Skaftafell. Below, an increasingly dense thicket of dwarf birchwood creeps up the mountain, and once-raging waterfalls are reduced to the trickle of streams. On almost all sides, the view of dozens of forest islands, connected by a network of raised walkways, each united through a common tale, yet an entirely unique experience, ecosystem, and atmosphere unto their own. The walk through the forests of Skaftafell could take days, but it would be possible to spend years learning their stories, with every threshold offering the possibility of entering a new world entirely. To the north, in the watery remains of the Vatnajökull, new lagoons and a hundred rivers braid their way between the hills. To the south, the endless blue of the delta merging with the horizon of the sea. Birdsong, then, a cloudless sky.

109

TRANSECT THROUGH TIME 110

111

Landscape Archive / Proposal for a [Future] Ancient

GLOBAL ARCHIVAL ARBORETUM

112

113

114

The proposal for a Global Archival Arboretum as part of the wider network of experimental forest laboratories at Skaftafell is a further investigation into the possibilities of establishing ecological resilience for the forested landscapes of Iceland, and the world at large.

The design for the form of the laboratory is derviced from the existing Hallormsstaður National Forest on the east coast of Iceland., and speaks once again to landscapes of the past, from the perspective of the future. The laboratory also takes inspiration from Hallormsstaður - as one of the country’s largest and most diverse forests - and seeks to continue and go beyond what the woodland has already achieved for the biodiversity of Iceland.

Unlike the previous two laboratory proposals, the Archival Arboretum will be allowed to develop in a far wilder way, the only human intervention to be the transplantation of otherwise displaced trees. Whilst this encourages the natural processes of ecological succession and colonisation to proceed relatively uninhibited, the introduction of nonnative species, for instance from the Caledionian Pinewood laboratory, will generate an entirely novel ecosystem in itself, potentially the first of its kind in Iceland. Within what is currently an ecologically poor landscape, the new relationships forged between unlikely companion species might prove to strengthen both the ecological biodiversity and resilience of the site.

115

116

CASE STUDY / Hallormsstaður National Forest

Considered to be contemporary Iceland’s largest forest, the Hallormsstaður spans an area of over 740 hecatres. Whilst the majority of the canopy is comprised of native birch, the forest has been the site of large scale trials of exotic species, and is home to the Hallormsstaður Arboretum: a tree collection of over 80 species from accross the world.14

14 “Hallormsstaður National Forest,” Visit Egilsstadir, accessed March 14 2023, https://visitegilsstadir.is/en/things-to-see/hallormsstadur-national-forest/

117

118

CASE STUDY / Öskjuhlíð, Reykjavík

Öskjuhlíð, albeit small, is considered to be an example of one of Iceland’s best woodlands. Home to nearly 200,000 trees of species including native birches, spruces, conifers and pines. The sheltered conditions of the hill, in the centre of Reykjavik, has allowed some of the oldest trees to reach heights of over 15 metres15, in stark contrast to the dwarf birch woodlands currently surviving on the plains of the Skeiðarársandur - demonstrating that, given correct and stable conditions, forests may yet thrive in the tree-less land of the Vatnajökull.

119

15“Öskjuhlíð,” Guide to Iceland, accessed March 12 2023, https://guidetoiceland.is/travel-iceland/drive/oskjuhlid-hill

Siberian larch 120

Rowan

Sitka

PHASE ONE / CONSTRUCTION

- The onstruction of the soils and structures -

PHASE TWO / TRANSPLANTATION

Following completion of the construction stage accross the forest sites, preliminary transplantations can begin to take place. To begin with, tree species and saplings that were displaced during phase one - whether due to topographical alterations or the need to clear access for machinery and vehicles - will be transplanted into the novel soil. These species may include dwarf birch, holly, or alder; and represent the initial foundations upon which ecological succession will unfold in the future, determining not only which species of plants, insects and animals may come to colonise the forest, but what kind of experiential qualities the place may earn in time.

Downy birch

Sitka spruce

Holly

Hazel

121

Alder

PHASE THREE / ECOLOGICAL SUCCESSION AND ESTABLISHMENT

Following the comlpetion of the initial transplatation phase of the project, subsequent ecological succession may begin to unfold. In the coming decades, we might begin to see the migration and colonisation of native species local to the likes of the Hallormsstaður or Öskjuhlíð forests, such as sitka spruce, black cottonwood or siberian larch. Seed dispersal through wind or via birds might encourage these seeds to take root, supported by the novel conditions of the soil. At the same time, we may see the further establishment of transplanted species such as birch, alder, or hazel.

Sitka spruce

Alder

Sitka spruce

Alder

122

Hazel

Sibreian larch

Sibreian larch

123

Black cottowood

Rowan Aspen

124

Transplanted species are represented in blue, with native colonisers depicted in black

PHASE FOUR / FOREST MATURITY

A forest for the future, and for ecological resilience, the experimental nature of the Archival Arboretum is difficult to predict or pin down. We might see hardier, native species such as the lodgepole pine dominate the canopy, with transplanted species such as juniper or rowan struggling to compete. Owing to increasingly milder climates, we might see the invasion of wholly unprecedented foreign species from overseas or the experimental implementation of exotic trees at Hallormsstaður. What is certain to be seen, with each new metre of growth, layer of bark, with each new mushroom or catepillar, the history of the landscape reveal itself to us - through all its struggle, transition, and successas a living archive of this transformative period in the history of the Vatnajökull. More than the past, what will it suggest for our future? And what will we learn about the possibilities afforded by experimental forestry. What is possible?

Holly Lodgepole pine Sitka spruce Alder

Holly Lodgepole pine Sitka spruce Alder

125

Black cottowood Siberian larch Juniper Hazel

126 TRANSECT THROUGH TIME

127

For the legend / complete archival collection of Future Tree Species, see Appendix, 12.

128

129

Chapter Four

HIDDEN TREASURES / THE MICROBIAL ECOLOGIES OF THE GRÍMSVÖTN

SUBGLACIAL LAGOON

130

131

For the complete archival collection of Cryolake Microecologies, see Appendix, 152.

132

Existing conditions of the Grímsvötn subglacial geothermal caldera

The Grímsvötn subglacial geothermal caldera is one of three calderas above the central subglacial volcano in the Vatnajökull, and represents one of the rarest, most valuable habitats on earth. Characterised by darkness, scarce oxygen, abundant methane and hydrodgen, with plenty of organic material, they posses a unique and self-sufficient biome; ‘a bit like a terranium, only substituting the glass with ice and the plants with algae’ 16. Once believed to be sterile wastelands, it has only recently been discovered that these geothermal subglacial lakes are in fact furnished with tiny life forms: vibrant ecosystems of microorganisms that function as a nutrient factory for all life downstream of the glacier, released through glacial flour in the meltwater. It has also been noted that these environments might serve as analogies for the earliest habitats on earth, as well as offering opportunities to study life in extreme environments on modern earth, and life as it may exist elsewhere in our solar system.

As rare and uniquely ecologically valuable as it is, the Grímsvötn subglacial lake is equally under particular and direct from impending glacial melt. Currently encased by as much as 300m of ice, the exponential retreat of the glacier is threatening to irrevocably alter this habitat, endangering the microbial ecologies - and by consequence - the ecologies of all life that they support downstream.

133

16Jemma Wadham, Ice Rivers: A Story of Glaciers, Wilderness, and Humanity (London: Penguin Random House UK, 2022), 102.

‘Our conception of glaciers was gradually being transformed from cold, sterile deserts to nutrient factories for a whole range of neighbouring ecosystems’17

134

17Jemma Wadham, Ice Rivers: A Story of Glaciers, Wilderness, and Humanity (London: Penguin Random House UK, 2022), 102.

135

136

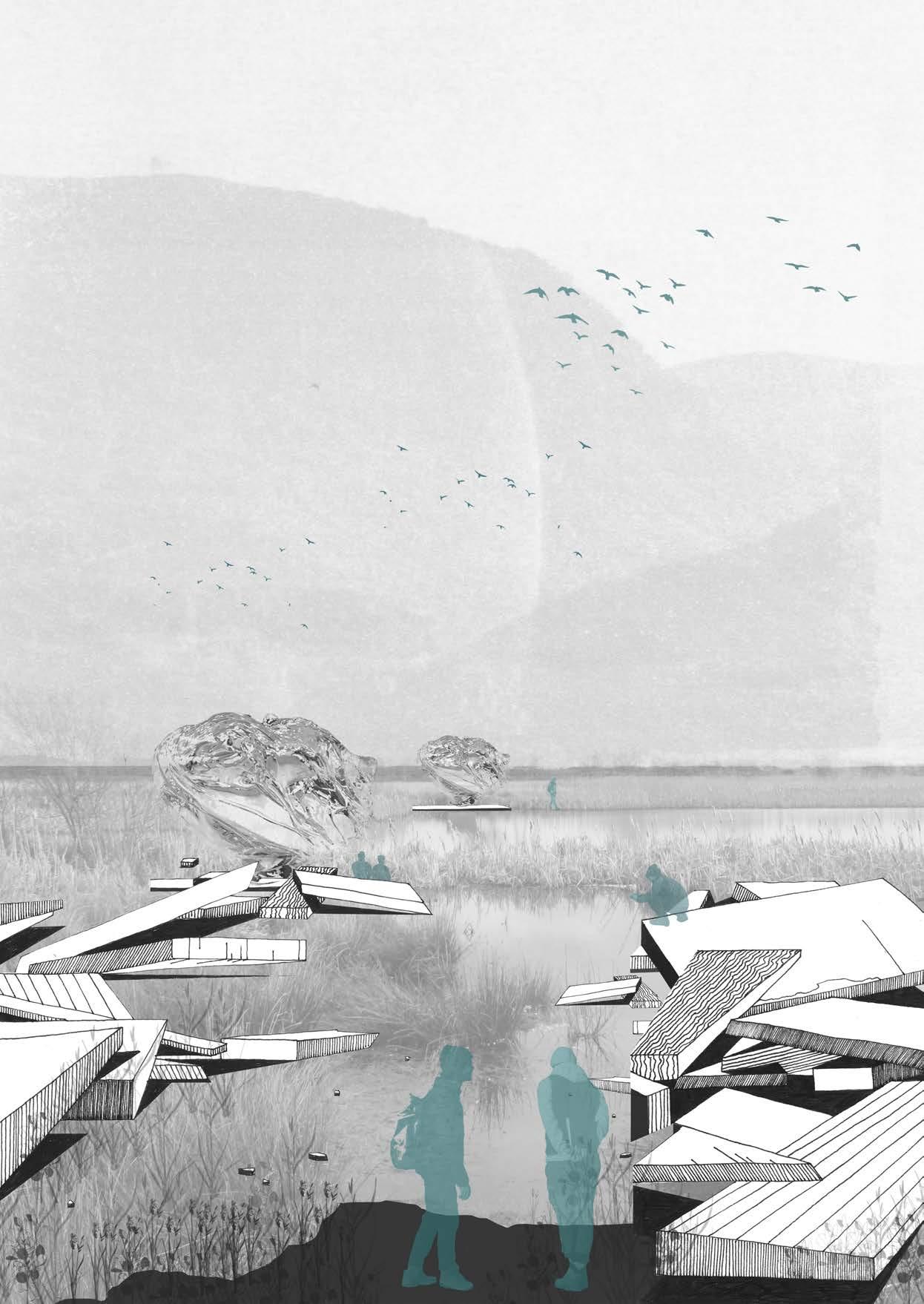

Proposal for a cryolake landscape installation at Grímsvötn

The conceptual proposal for the site at Grímsvötn is a cryolake installation to draw attention to the need to preserve and value the unseen microbial ecologies that live beneath the ice of the glacier. ‘Cryolakes’ are cryconite holes covered with thin ice sheets, often interconnected by tiny watery channels also covered with ice roofs, and represent a micro-scale model of the larger Grímsvötn lagoon. The proposal is to install artificial domes of black glass on top of cryconite holes as they emerge surrounding the site, as a means of preserving subglacial conditions even as the ice melts, blocking out the majority of light and oxygen. The first cryolakes to have the glass installed might develop richer microbiomes with time, resulting in a network of tiny, hidden ecosystems working to preserve subglacial life for a post-glacial future.

Whilst the proposal for this site is largely conceptual, and oriented around the more-than-human experience on the microbial scale, the installation might spark a conversation amongst those visiting the park, drawing vital attention to the emerging conversation around the importance of subglacial ecologies.

137

138

The conceptual proposals behind the installation of glass domes over emergent cryolakes surrounding the former subglacial lagoon at Grímsvötn represent part of a wider thesis for the future Vatnajokull Botanical Park - that of numerous, potentially hundreds of, ‘archive gardens’ that each responds uniquely to notions of archiving.

Where the proposals for the Grímsvötn site relate to a universal maifesto of ecological preservation for disappearing landscapes, other prospective sites might disrupt the existing landscape in order to create novel atmospheric conditions, or more stability to facilitate future ecological development. Some sites might seek to create unique atmospheric experiences for human visitors, acting as a legacy for glacial atmospheres lost. Some might physically ‘archive’ the processes of the landscape as living museums of sorts, or serve as memorials for the glacier for future generations

139

Chapter Five

POSTCARDS FROM THE FUTURE

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

ENDNOTES

1Eloïse Mercer, “Into the Cyanosphere,” assignment for Landscape architecture design exploration: Part 1, MLA Landscape Architecture (Edinburgh University, 2022).

2Jemma Wadham, Ice Rivers: A Story of Glaciers, Wilderness, and Humanity (London: Penguin Random House UK, 2022), 122.

3Katie Paterson, First There is a Mountain, Various locations along the UK Coastline, March 31 - October 27 2019, Participatory Artwork.

4John Tyndall, “Clouds, Rains and Rivers,” in The Forms of Water in Clouds and Rivers, Ice and Glaciers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 2-7.

5 John Tyndall, “The Waves of Light,” in The Forms of Water in Clouds and Rivers, Ice and Glaciers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 14.

6Andri Snær Magnasson, On Time and Water: A Histry of Our Future (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2021).

7RAAAF / Atelier de Lyon, Deltawerk, 2018, landscape architecture installation project, Noordoostpolder, the Netherlands, accessed April 1 2023, https://www.raaaf.nl/en/projects/1005_deltawerk.

8“Elwha River Restoration,” National Park Service, accessed March 3 2023, https://www.nps.gov/olym/ learn/nature/elwha-ecosystem-restoration.htm

9“Wetlands,” WWT, accessed February 28 2023, https://www.wwt.org.uk/discover-wetlands/wetlands/

10“Forestry in a treeless land 2017,” Icelandic Forest Service, accessed March 17 2023, https://www.skogur. is/static/files/2017/Forestry_in_treeless_land_BKL_210x260mm.pdf

11“History of Forests in Iceland,” Icelandic Forest Service, accessed February 18, 2023, https://www.skogur. is/en/forestry/forestry-in-a-treeless-land/history-of-forests-in-iceland.

12“Caledonian Pinewood Recovery,” Trees for Life, accessed March 1 2023, https://treesforlife.org.uk/aboutus/caledonian-pinewood-recovery.

13”Ibid.

14 “Hallormsstaður National Forest,” Visit Egilsstadir, accessed March 14 2023, https://visitegilsstadir.is/en/ things-to-see/hallormsstadur-national-forest/

15“Öskjuhlíð,” Guide to Iceland, accessed March 12 2023, https://guidetoiceland.is/travel-iceland/drive/oskjuhlid-hill

16Jemma Wadham, Ice Rivers: A Story of Glaciers, Wilderness, and Humanity (London: Penguin Random House UK, 2022), 102.

17Ibid. 104.

Caledonian Pinewood Recovery,” Trees for Life, accessed March 1 2023, https://treesforlife.org.uk/about-us/ caledonian-pinewood-recovery.

Elwha River Restoration,” National Park Service, accessed March 3 2023, https://www.nps.gov/olym/learn/ nature/elwha-ecosystem-restoration.htm

Forestry in a treeless land 2017,” Icelandic Forest Service, accessed March 17 2023, https://www.skogur.is/ static/files/2017/Forestry_in_treeless_land_BKL_210x260mm.pdf

History of Forests in Iceland,” Icelandic Forest Service, accessed February 18, 2023, https://www.skogur.is/ en/forestry/forestry-in-a-treeless-land/history-of-forests-in-iceland.

“Hallormsstaður National Forest,” Visit Egilsstadir, accessed March 14 2023, https://visitegilsstadir.is/en/ things-to-see/hallormsstadur-national-forest/

“Öskjuhlíð,” Guide to Iceland, accessed March 12 2023, https://guidetoiceland.is/travel-iceland/drive/oskjuhlid-hill

Paterson, Katie. First There is a Mountain, Various locations along the UK Coastline, March 31 - October 27 2019, Participatory Artwork.

Magnasson, Andri. On Time and Water: A Histry of Our Future. 2021. London: Serpent’s Tail.

Mercer, Eloïse. “Into the Cyanosphere.” Assignment for Landscape architecture design exploration: Part 1, MLA Landscape Architecture. Edinburgh University, 2022. Unpublished.

RAAAF / Atelier de Lyon, Deltawerk, 2018, landscape architecture installation project, Noordoostpolder, the Netherlands, accessed April 1 2023, https://www.raaaf.nl/en/projects/1005_deltawerk.

Tyndall, John. “Clouds, Rains and Rivers,” in The Forms of Water in Clouds and Rivers, Ice and Glaciers 2012. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tyndall, John. “The Waves of Light,” in The Forms of Water in Clouds and Rivers, Ice and Glaciers. 2012. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wadham, Jemma. Ice Rivers: A Story of Glaciers, Wilderness, and Humanity. 2022. London: Penguin Random House UK.

“Wetlands,” WWT, accessed February 28 2023, https://www.wwt.org.uk/discover-wetlands/wetlands/

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1Eloïse Mercer, “Into the Cyanosphere,” assignment for Landscape architecture design exploration: Part 1, MLA Landscape Architecture (Edinburgh University, 2022).

1Eloïse Mercer, “Into the Cyanosphere,” assignment for Landscape architecture design exploration: Part 1, MLA Landscape Architecture (Edinburgh University, 2022).

Katie Paterson, First There is a Mountain, Various locations along the UK Coastline, March 31 - October 27 2019, Participatory Artwork. https://www.firstthereisamountain.com

Katie Paterson, First There is a Mountain, Various locations along the UK Coastline, March 31 - October 27 2019, Participatory Artwork. https://www.firstthereisamountain.com

Sibreian larch

Sibreian larch

Holly Lodgepole pine Sitka spruce Alder

Holly Lodgepole pine Sitka spruce Alder