From Generation to Generation

The last of the Holocaust survivors are dying. It’s on this generation to remember their stories. Stories filled with hardship and hope, loss and remembrance. Stories hidden in documents, photographs, and objects scattered like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Stories rarely told, that bring a tear to your eye when the words finally spill out. My family is one of these stories. Both sides of my family are Jewish and emigrated from Eastern Europe during the Holocaust. They leave behind memories of their lives affected by the Holocaust in photos, diaries, memoirs, official documentation, letters, and oral tales. By piecing together materials from my family’s personal archives and my own, this book explores stories left behind and form the memory of our history, a narrative shared by the hundreds of thousands of families who survived the terror of persecution during the Holocaust. This book is a telling of our story, a documentation of our history. This book is our memory.

”The situation was very bad. They were catching us, killing us, starving us. And we knew that something terrible was awaiting us. So we decided that we had to build a hiding place.”

The light of life is a finite flame.

Like Shabbat candles, life is kindled, it burns, it glows, it is radiant with warmth and beauty. But it soon fades, its substance consumed, and it is no more.

In light we see; in light we are seen. The flames dance and our lives are full. But as night follows day, the candle of our life burns down and gutters. There is an end to the flames. We see no more and are no more seen, yet we do not dispair, for we are more than a memory slowly fading into darkness. With our lives we give life. Something of us can never die: we move in the eternal cycle of darkness and death, of light and life.

Meditations before Kaddish i

Meditations before Kaddish i

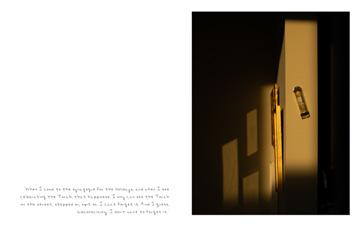

”When I come to the synagogue for the holidays, and when I see celebrating the Torah, that happiness, I only can see the Torah on the street, stepped on, spit on. I can’t forget it. And I guess, subconsciously, I don’t want to forget it.”

They didn’t change our names, we did. Rolf became Ralph. Erika became Erica. Buckling under the pressure to conform, to assimilate. ”Steinberger,” stone mountain in German, was close to crumbling into ”Hill.”

word ’home’ now sounds almost strange to my ears. I had a beautiful, cozy home, a home with a wonderful family, but what has happened to this home of mine?”

”The

She was beautiful, he says about her, the woman I’ve never met and never will. The mother of my father, who I never called Grandma.

I never met Erika, but Dad always says I have her chin.

If not for the Holocaust, they would never have left Germany.

If not for the Holocaust, they would never have met.

If not for the Holocaust, I would never have been born.

”It was a small city. We knew each other, everybody knew each other. And nothing is left. They can say nothing happened; let them go to our city.”

The German Shepherds gnawed at her hands, leaving them forever mangled. But the dogs didn’t kill her

Someoneiswatchingoverme.

She left her hiding place with her husband, leaving her parents behind. Her parents’ bunker was later discovered by the Nazis.

Someoneiswatchingoverme.

After Liberation Day, many Jews stayed in Poland, where the killings later continued. But she took her family to Czechoslovakia, from where they were able to flee to the United States.

Someoneiswatchingoverme.

”’All my life I was a Zionist. I prayed and always hoped that I would live to see my homeland, Eretz Israel. But never will I see my homeland, but you and many survivors will. To regain our pride and dignity as Jews, the only way is our Eretz Israel. The day will come. Miracles will happen and we will regain our homeland, Eretz Israel. Yom Israel chai. Long live my people.’

That was my father’s last sentence.”

Farther and farther they traveled from home. A home destroyed when they left, probably in shambles now. But who knows, because we won’t be going back. Not safe for them then, not safe for me now.

”May it be the will of the Lord to lead us to the destination. Live in joy and peace. Protect us from all enemies. From evil, bigots, and robbers. From catastrophe and all the dangers of the journey. Bless our Lord. Grant us grace and mercy. Bless our Lord who listens to our prayers. Amen.

Leave now and God will protect you.”

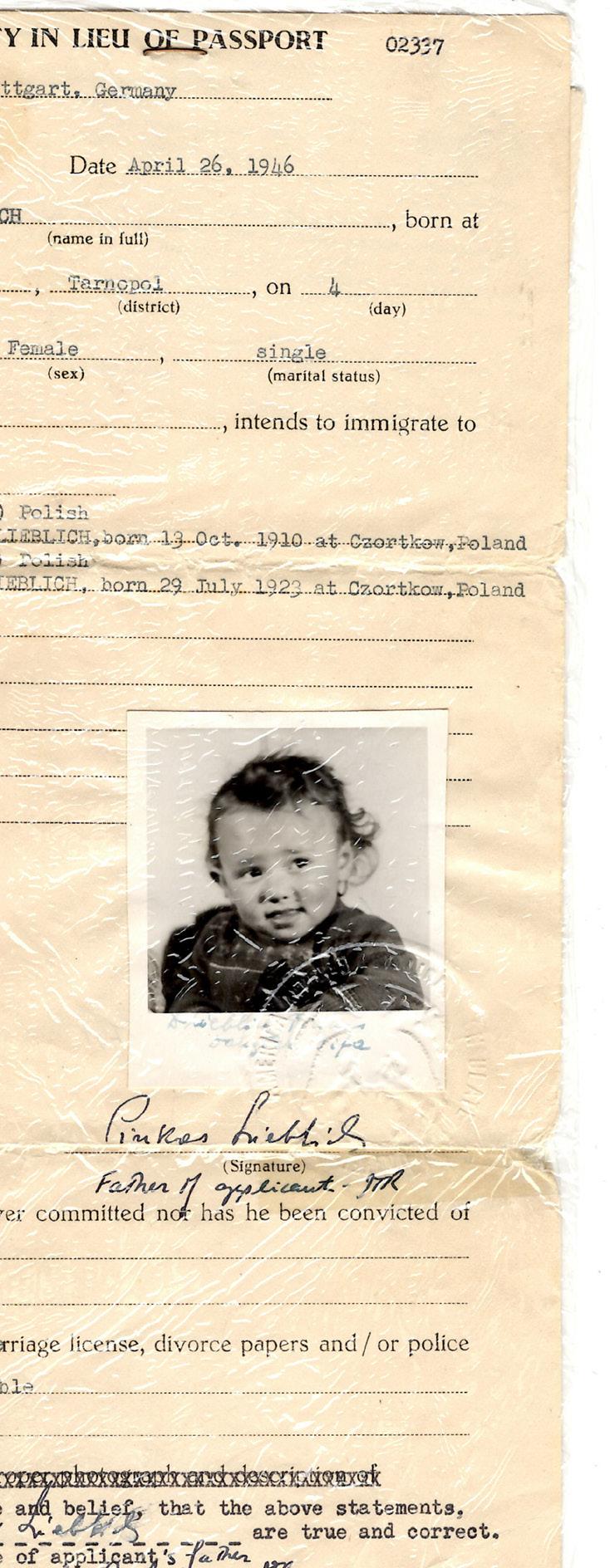

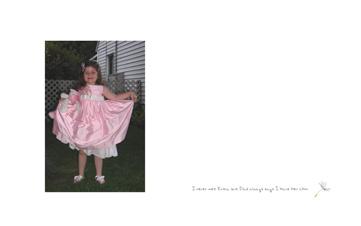

”She was the first child born after the Holocaust. Her birth brought us hope in a future for the new generation.”

”I’m not alone. Thank God for that. No, I am not alone. This is my family.”

Florence Lieblich, nee Fryma Mayer, Meier, Majer

My maternal great grandmother, my mother’s mother’s mother, born in Czortkow. Escaped Poland after the war and fled to Czechoslovakia, Germany, and finally the United States with her daughter Gloria and husband Phil. Lived in New York until her death, and had one daughter, two granddaughters, and four great grandchildren.

Gloria Kaplan, nee Gifa Lieblich

My maternal grandmother, my mother’s mother, born in Czortkow. Escaped Poland with her parents, Florence and Phil. Currently splitting time between Florida and Massachusetts with her husband, ie my grandfather, Michael. Has two daughters and four grandchildren.

Philip, Phil Lieblich, nee Pinkas Lieblich

My maternal great grandfather, my mother’s mother’s father, born in Czortkow. Escaped Poland with his wife, Florence, and daughter, Gloria. Died in a hotel while in Israel for a medical conference, and had one daughter and two granddaughters, as well as four great grandchildren whom he never met.

Ralph Steinberger, nee Rolf Steinberger

My paternal grandfather, my father’s father, born in Germany. Left to the United States before the war,

and went back to Europe to fight for the Americans.

Met his wife Erica once he came back from the war, and had a daughter and a son, as well as two grandchildren, one of whom he never met.

Erica Steinberger, nee Erika Loebl, Lobl

My paternal grandmother, my father’s mother, born in Bamberg. Fled Germany with her brother, Werner, on the kindertransport to England, and met their parents in Quito, Ecuador, where they had escaped to. Moved to the United States where she met her husband, Ralph, and had a daughter and a son, as well as two grandchildren whom she never met. Died after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease.

Werner Loval, nee Werner Loebl,Lobl

My paternal great uncle, my father’s mother’s brother, born in Bamberg. Fled Germany with his sister, Erica, and after the war, settled down in Israel. Had four children, twelve grandchildren, and seven great grandchildren, all of whom lived in Israel with him, and most of whom were close by when he died this past November.

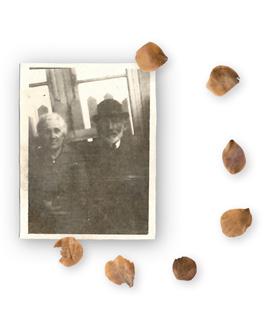

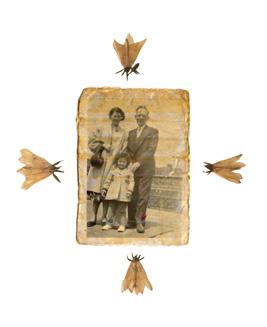

Florence Lieblich with her daughter Gloria in the United States a few years after they emigrated from Czortkow, Poland, near the end of World War II. Florence and her husband, Philip, left Poland with their daughter to seek a better life for themselves, free from persecution.

Left: A framed photograph of me as a child cooking with Great Grandma Florence.

Right: One of the notes left in an envelope filled with notes from Florence written on Post It Notes and scraps of paper. Undated and unaddressed. It reads: ”The day has arrived with the birth of your precious bundle of joy. The future will be filled for both of you. Happiness and joyous always. All my love, Florence.”

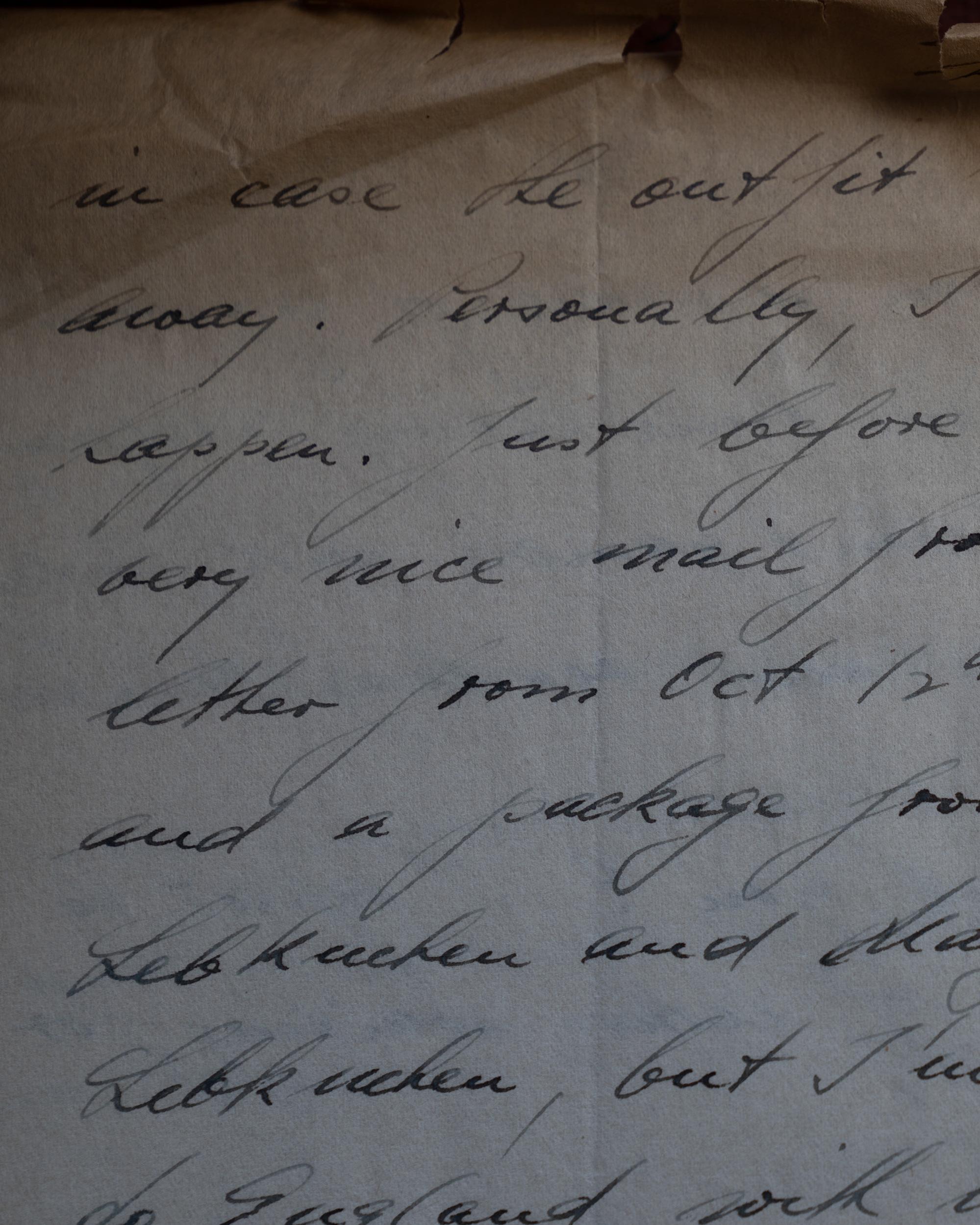

Left: A letter written by Florence to the Galician Federation of New York, asking them to help her locate her brother, Rabbi Mordechai Mayer, who left for New York before the war broke out in Poland. She wrote this in Stuttgart, Germany, where they were staying after fleeing Poland and before they were allowed to register to immigrate to the U.S.

Right: A portrait of Florence in her school

clothes. Taken before the war.

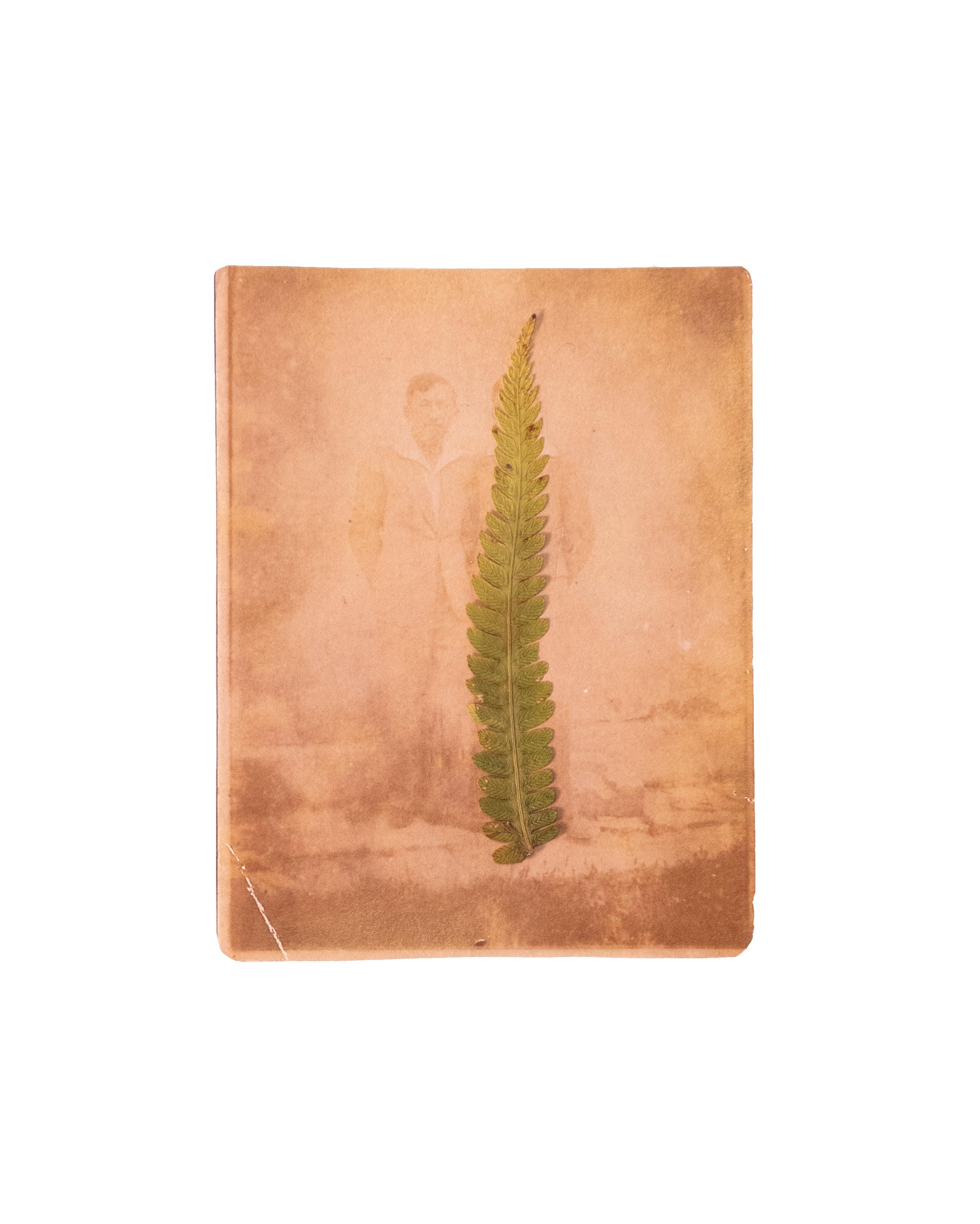

Erica Loebl in Ecuador, in her gown after she was named beauty queen of Quito’s Jewish community. Erica and her brother Werner left their home in Bamberg, Germany, on the Kindertransport to England, leaving behind their parents, Sally and Freida. After being denied entry into multiple different countries, including the U.S., Sally and Freida were granted entry to Ecuador, where Erica and Werner eventually met them. Daisies, which I placed along the rim of Erica’s gown, represent beauty and new beginnings.

A swastika badge, which Ralph Steinberger took from a dead Nazi while he was working in prisoner of war camps, resting on top of letters he wrote to his parents as seen reflected through his compact mirror. Born in Germany, Ralph fled to the U.S. and served in the war. My grandfather the chemist was fluent in German, and thus an asset to the Americans, so even though he didn’t have any formal medical training, he worked as a medic and pharmacist in German prisoner of war camps, primarily in France.

A photograph, hidden behind ivy, of Florence and Phil in a bunker in Poland alongside other Jews. Florence’s parents, Rabbi Meir and Gitel Mayer, foresaw that Florence’s dear friend Phil would keep their daughter safe, so Rabbi Meir married the two before sending them to Phil’s hiding place and saying goodbye forever. The quote is from an interview with Florence conducted by the USC Shoah Foundation, which, along with many other organizations, helped record first person testimonies from the Holocaust in order to preserve their stories. Certificates of identification for Florence, Gloria, and Phil, which they received in order to immigrate to the U.S. Ferns point the way forward.

A portrait of Efraim Lieblich, Phil’s brother, who did not survive the war. The leaves of the ginkgo tree, which can live to be thousands of years old, bury the photo and juxtapose Efraim’s short life.

Phil with an unknown woman. Highlighted is the town in Poland in which the family of my maternal grandfather, Michael, came from.

A portrait of Ralph in his army uniform, rephotographed through the magnifying lens of an antique film camera. Layered on top is a translucent rendering of one of the many letters Ralph wrote to his parents during the war.

Phil’s parents, Feiga and Mendel Lieblich. Phil was the only one in their family to survive the Holocaust.

The last night of Chanukah. The Jewish holiday celebrates the rededication of the Second Temple of Jerusalem, after the Greeks had destroyed it. Though there was only enough oil found to light a lamp for one night, the lamp stayed lit for eight, which is the reason for the eight nights of Chanukah and the eight candles on the Chanukiah, or Chanukah menorah. Jews

have been persecuted throughout history, from the ancient Greeks to the modern day Nazis, but still, Judaism perseveres. The passage on the right, a meditation recited before the Kaddish, which is a prayer to mourn those who have died, relates our lives to that of a candle, once bright with light and life, but eventually consumed by darkness and death. Though our individual candles may go out, the light of Judaism is still aflame.

Right: A mezuzah on a door frame in my maternal grandparents’ living room. Placed in the liminal space between rooms, between an ”outside” and an ”inside,” the mezuzah is a reminder that God is protecting that space and watching over you. It contains prayers and passages from the Torah blessing God and reminding us that there is only one God.

Left: The quote is from an interview with Florence conducted by the USC Shoah Foundation, in which she recalls the sight of Nazis stepping and spitting on the Torah, a sign of disrespect and hatred.

Phil, left, and Efraim together before the war. Phil survived, Efraim did not.

A portrait of Florence’s brother Mordechai and her mother Gitel atop one Czortkow’s synagogues before it was destroyed by the Nazis. The lavender represents the calmness of the pre war days.

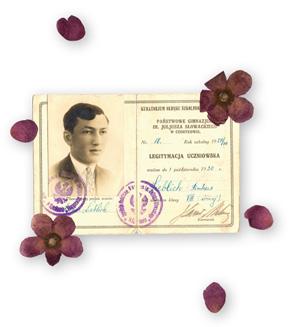

Phil’s ID for medical school in Czortkow, where he was a licensed doctor. He continued his profession after he immigrated to the states, and Florence said in her memoir that after he died, it was a loss not only to herself and their family, but to his patients, who were always his first priority. I find that it is those who have lost many that always have the urge to save many more.

Ralph’s dog tags from the war, resting on top of letters he wrote to his parents in New York. Though his dog tags used his German name, Rolf, he signed his letters home with its Americanized version, Ralph.

Left: Dad cooks Ralph’s barbecue chicken at our annual family reunion in Copake, New York. He wears his dad’s chicken cooking shirt, now ripped at the seams, as he does every year on the one night that we host dinner. Ralph and Erica bought the house in the background, which my aunt now owns, because the area reminded them of Tegernsee in their home country of Germany, as both are peaceful towns on the shore of a lake. They drove their two children to the house every weekend during the warm months, where the family would go swimming, pick blueberries, and play by the stream. Now, every summer, we travel to Copake to do the same, to carry on those traditions.

Right: Werner’s certificate of identity, used to sail from England to Argentina before meeting his parents in Ecuador.

Erica in front of her dad’s business car in Bamberg, Germany. The background is an entry, written in German script, from Erica’s tagebuch or diary, which her grandmother gave her for her birthday. She kept wrote regularly in this diary, followed by a second

one, until she was in Quito, Ecuador, bringing it with her and keeping a historical record of the Holocaust through the eyes of a young woman. No one in my family really knew about the diaries until my aunt Barbara found them while sifting through Erica’s belongings after she died. Her brother Werner immediately remembered the diaries and their significance, and he translated them and included copies within his memoir, ”We Were Europeans.”

Left: Erica and Werner by their dad’s business car in Bamberg, Germany.

Right: The Loebl family, Werner, Freida, Sally, and Erica, on a walk in Bamberg.

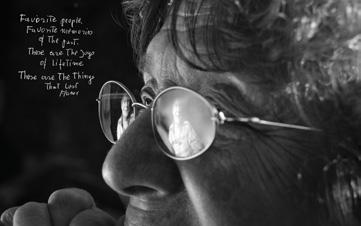

A portrait of Gloria, with her husband Michael reflected in her glasses. The note, undated and unaddressed, is from an envelope filled with notes from Florence written on Post It Notes and scraps of paper. It reads: ”Favorite people. Favorite memories of the past. These are the joys of lifetime. These are the things that last. Florence.”

A drawing of Erica’s hometown of Bamberg, Germany. In the corner is a quote from the translated version of her diary.

Erica in her Purim costume, before the war. The dandelion seeds reflect the daintiness of youth and the passage of time.

Me before my preschool graduation.

Ralph and Erica the year they were married. On top of the photo is a German Reichpfennig, engraved with a federal eagle and a swastika, both symbolic of Nazi Germany. Photographed through the lens of an antique film camera. Erica’s mother and Ralph’s mother knew each other from their girlhood in Germany, and they reconnected after they both immigrated to New York. They discovered they had children who were both of ”marriageable” age, Werner said in his memoir, and the rest was history.

A photograph of Florence and Gloria in the United States a few years after they emigrated from Czortkow, Poland, near the end of the war. Next to it, a ginkgo leaf and the envelope filled with notes from Florence written on Post It Notes and scraps of paper.

A portrait of Phil on top of Czortkow before the city was destroyed.

A quote from an interview with Florence conducted by the USC Shoah Foundation.

A photograph of Florence, Phil, and Gloria in the United States a few years after they emigrated from Czortkow, Poland, near the end of the war.

A portrait of Phil in Czortkow, seemingly peering through a stalk of goldenrod, keeping watch and protecting.

Florence, Phil, and Gloria in New York. Florence always said that someone was watching over her, she survived so many near death experiences where it was impossible for her to believe otherwise. The flowers surrounding the photo represent all those watching over her, whether she meant God, her parents, or others.

A photograph of Phil, used for his certificate of identification.

A photograph of Florence, used for her certificate of identification.

A tattered Israeli flag flying above the streets of Israel. Taken on a family trip. The passage on the right is an excerpt from Florence’s memoir, entitled ”Someone is Watching Over Me.”

Florence and Gloria on a train in the U.S. Maple seeds represent strength and endurance, and although their paths are dizzying as they fall from the tree, they eventually travel safely to the ground.

Out the car window en route to Copake, New York, for our annual family reunion. The passage is an excerpt from Florence’s memoir, in which her father recites the traveler’s prayer, typically said before a journey, to Florence before she departs with Phil to hide in a bunker.

A photograph of Florence and Gloria in New York. Beneath it, a radiogram sent from Florence’s brother welcoming her and her family to the country.

Left: Florence pushing Gloria on a swing in the U.S.

Right: A quote from an interview with Florence conducted by the USC Shoah Foundation.

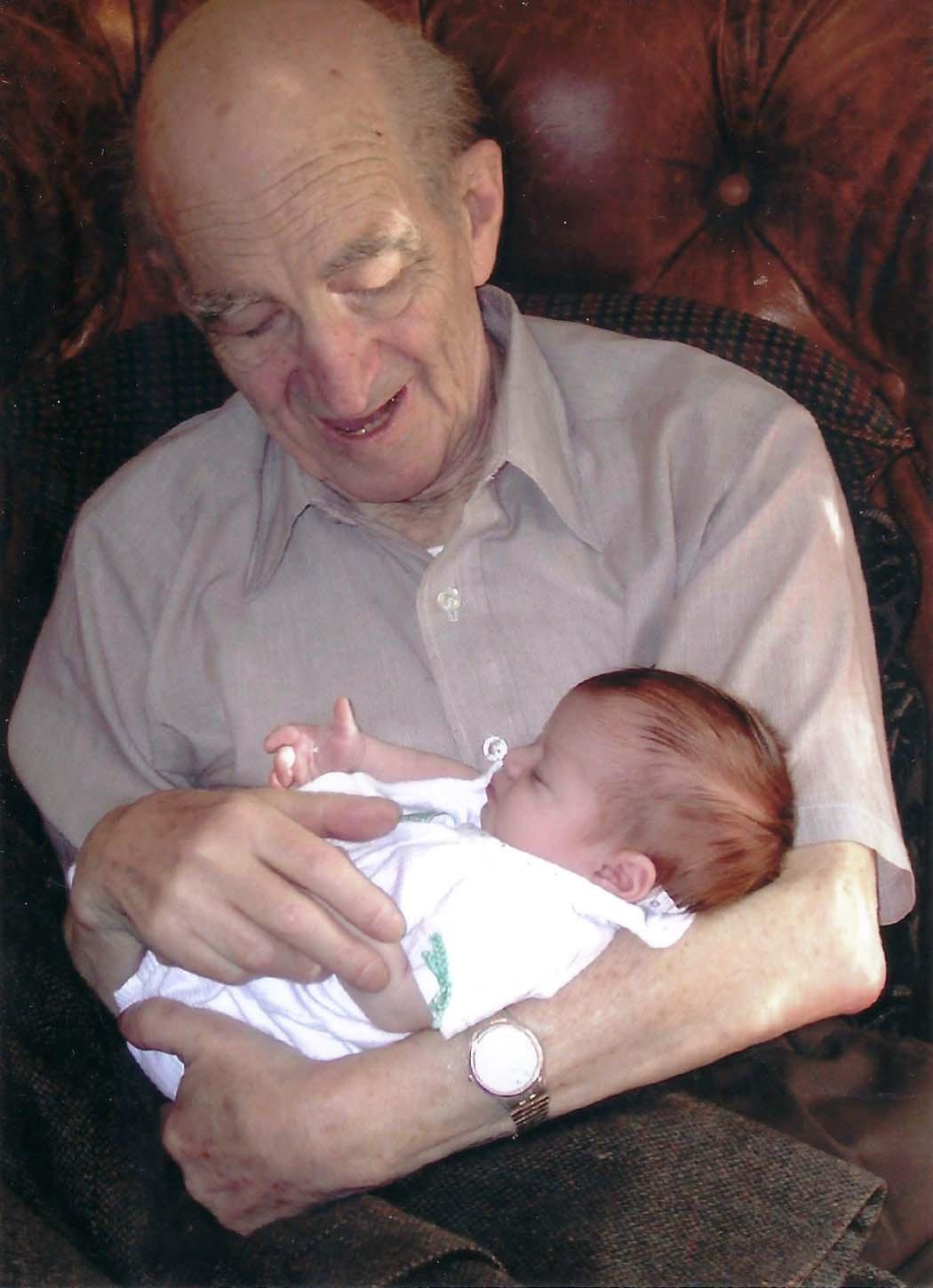

Ralph holding me, just days after I was born. He flew out to California for my birth, the only time I met my grandfather, as he died one year later at his home in New York. Dad loves the photo because of the beam of light falling onto the two of us. The background is of the bedroom with the twin beds in our Copake house, the bedroom that my sister and I sleep in when we visit during the summer, the bedroom that my dad and his sister used to sleep in when they would visit every weekend. It’s plastered in the same wallpaper, that is now just beginning to peel.

A quote from an interview with Florence conducted by the USC Shoah Foundation.