SPRING 2024

“Our goal is not just to develop algorithms from a diagnostic perspective, but also to be able to prognosticate disease outcome and predict therapeutic response.”

Anant Madabhushi, PhD,Member of the Cancer Immunology Research Program at Winship Cancer Institute and executive director, Emory Empathic AI for Health Institute

“You have to trust your doctors. You have to stay with them. You have to take their advice. It’s important that you really understand the options and the treatments. Don’t be afraid to ask questions.”

Keith Sievers, Survivor

Winship Magazine | Spring 2024

From the Executive Director 2 In the News

Pioneering Perspective 3

CASSANDRA QUAVE, PHD The Magic of Nature’s Pharmacy: Lessons from the Yew Tree Welcome to Winship 4 Four Scientists Who are Changing the World of Cancer Cover Story

Emory | Winship Magazine is published biannually by the communications office of Winship Cancer Institute, a part of the Woodruff Health Sciences Center of Emory University, emoryhealthsciences.org. Articles may be reprinted in full or in part if source is acknowledged. If you have story ideas or feedback, please contact john.manuel.andriote@emory.edu. © Emory University

The Quiet Revolution: How AI is Changing Cancer Medicine 6 Features

Keith Sievers Finds His “ Warrior Mode”: Small Victories are Key to Staying Strong During Long Treatments 14

The Cancer Moonshot: How Winship is Working to End Cancer as We Know It 18

Emory University is an equal opportunity/equal access/affirmative action employer fully committed to achieving a diverse workforce and complies with all federal and Georgia state laws, regulations and executive orders regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. Emory University does not discriminate on the basis of race, age, color, religion, national origin or ancestry, sex, gender, disability, veteran status, genetic information, sexual orientation, or gender identity or expression.

Winship Navigates Industry Drug Shortage 24

Repurposing Old Drugs for New Uses in Innovative Cancer Care 26 Around Winship

Philanthropy: Grateful Patient Funds

Surgical Oncology Research Fellowship 30

Inspiring Hope: Cicely Lakisha Leufroy 32

Website: winshipcancer.emory.edu. To view past magazine issues, go to winshipcancer.emory.edu/magazine.

Editor: John-Manuel Andriote Art Director: Marco Alarcón

Lead Photographers: Jenni Girtman, Jack Kearse

Contributors: Andrea Clement, Susannah Conroy, Javier De Jesus, Jenny Owen

. The beginning of spring brings exciting new possibilities to improve the lives of the patients we serve. Driven by our discovering cures for cancer and inspiring hope,” Winship marches forward, building on its strong trajectory of accomplishments in recent years. In this issue, we hope to take you on a journey of exploration as we showcase exciting new developments in cancer care and research at Winship.

special designation means for Winship’s role in helping to fulfill the goals of the National Cancer Plan, the strategy for achieving the nation’s goal of reducing cancer deaths by 50% by the year 2047.

At the heart of everything we do at Winship is providing our patients with the best chance of surviving cancer and thriving. That’s why we feel enormous gratitude when a patient takes the time to share with others about their experience at Winship. In this issue, Keith Sievers shares his dramatic story and equally dramatic outcome thanks to his participation in a clinical trial.

“At

the heart of everything we do at Winship is providing our patients with the best chance of surviving cancer and thriving.”

We begin by considering three of the thousands of botanicals—plants, trees and their leaves, bark, flowers, berries and fruit—that have been found to possess positive effects in treating cancer. We look at drugs that have been used to treat common conditions and were repurposed to treat cancer. Alongside the new uses for old drugs, we examine the shortages of some widely used cancer drugs— and how Winship’s pharmaceutical team works to ensure that a steady supply is available for our patients.

Our cover story delves into the quickly evolving role of artificial intelligence (AI) in cancer research and care. We look inside the “brain” of AI and explore the fascinating and exciting AI-related work under way at Winship that is already revolutionizing important aspects of cancer care.

We were honored in 2023 to receive the five-year renewal from the National Cancer Institute as one of the country’s few NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers. We explore in this issue what this

We couldn’t provide the best cancer care without the dedication and passion of our nurses. We are pleased to shine a light on infusion nurse Cicely Lakisha Leufroy in this issue’s “Inspiring Hope” interview.

Our impact would be critically limited without the support of our generous donors. We highlight a Winship patient and donor who chose to contribute toward educating future cancer doctors, nurses and researchers.

Thank you for your interest and support.

With deep appreciation,

Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, FACP, FASCOPIONEERING PERSPECTIVE

n a small churchyard in the countryside village of Fortingall, Scotland, there stands an ancient tree—perhaps the oldest in Europe—protected by a stone wall. To reach it, you must first walk through a small cemetery, its grounds covered in lush green grass, and moss filling the spaces between headstones carved with names and symbols from a time long past. Known as the Fortingall Yew, this particular tree is estimated to be thousands of years old. In Celtic lore, the yew tree symbolizes death and resurrection and is used in rituals linked to magic, fertility and power.

As a medical ethnobotanist, I have visited this tree and many other “magical” plants across the globe in my search for knowledge about the treasures the plant kingdom has to offer for the future of our medicines.

The English yew tree (scientific name: Taxus baccata) is special not only because of its long lifespan and ties to magic, but also for its toxic properties. Its evergreen needles, bark and seed cones are full of poisons. The only part of the yew that is not poisonous is its fleshy red aril, which surrounds the single seed of each cone. This part is edible if you spit out the seed. The wood of the English yew is easy to carve and was the preferred material for crafting early musical instruments such as the lute and the infamous medieval English longbow.

In the 1950s, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) established the Cancer Chemotherapy National Service Center to develop new cancer therapies. Initially focused on testing known and synthetic compounds, the program expanded in the 1960s through a partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), exploring natural sources for cancer cures. Between 1960 and 1981, over 30,000 samples were collected for cancer testing.

One notable sample was from the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia), a relative of the English yew, collected in Washington State in 1962 by USDA botanist Arthur Barclay. In 1964, chemists Monroe Wall and Mansukh Wani, supported by an NCI contract, discovered that the yew tree extract was toxic to living cells, isolating the most potent compound, paclitaxel.

Paclitaxel’s 30-year journey from discovery to FDA approval faced numerous challenges. Selected for clinical development in 1977, it was approved for treatment of ovarian cancer in 1991 and for breast cancer in 1994. Biochemist Susan Horwitz, in 1977,

elucidated how paclitaxel impedes cancer growth by arresting cell division and inducing cancer cell death while stabilizing the microtubules, a mechanism distinct from other drugs.

Another major hurdle was production scalability, as the slow-growing yew tree couldn’t supply sufficient bark. The first breakthrough came from the toxic needles of the English yew, commonly used in landscaping. Chemists could convert a similar compound from garden clippings into the drug. Today, paclitaxel (also known as Taxol®) is mass-produced in fermentation tanks with plant cells serving as mini drug factories. It has been used to treat more than 1 million patients, making it one of the most widely used antitumor drugs.

Like the yew tree’s story, other vital cancer medications were discovered by examining medicinal plants and optimizing their active chemical structures as drugs. Consider etoposide, derived from the mayapple plant, used to treat cancers like testicular, prostate, bladder, stomach and lung cancer. Another example is the vinca drugs from the Madagascar periwinkle: vincristine, effective against leukemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma and Wilms tumor; and vinblastine, used for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, non-small cell lung cancer, bladder cancer, brain cancer, melanoma and testicular cancer.

There are an estimated 374,000 plant species on Earth, with about 9% (over 34,000) documented for use in various traditional medicines. However, a vast majority of these medicinal species (98%) have not yet undergone rigorous scientific study to identify their active molecules or to evaluate their safety and effectiveness in treating human diseases.

This scenario presents a vast, untapped reservoir of potent chemistry in nature, waiting to be explored. Numerous “magical” plants from folklore remain to be studied. The key is in our willingness to look. w

Cassandra Quave, PhD, is a medical ethnobotanist focused on documenting and pharmacologically evaluating plants used in traditional medicine. A member of the Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics Research Program at Winship Cancer Institute, she serves as the curator of the Herbarium, the Thomas J. Lawley, MD, Professor of Dermatology and associate professor of dermatology and human health at Emory University School of Medicine, where she is also the assistant dean of research cores.

Meet four of Winship’s outstanding research scientists whose day-to-day work is changing the game in important ways for people with cancer.

DAVID S. YU is a member of the Cell and Molecular Biology Research Program at Winship Cancer Institute and a radiation oncologist specializing in head and neck, breast and lung cancers at Grady’s Loughlin Radiation Oncology Center. Yu, MD, PhD, holds the Jerome Landry, MD, Chair of Cancer Biology and is a professor, director of the division of cancer biology and vice chair for biology research in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine.

Q: What is an example of how you have translated insights from interacting with patients and lab researchers to innovative therapies, and how have those therapies improved the quality of life for people with cancer?

A: In collaboration with Winship researcher Baek Kim, PhD, we have found a novel role for cellular enzyme SAMHD1 as a DNA repair factor that

TYLER S. BEYETT is a member of the Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics Research Program at Winship Cancer Institute and an assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology at Emory University School of Medicine. His research is primarily focused on the clinical development of allosteric EGFR inhibitors for drug-resistant lung cancers, and his lab is generally interested in kinases and phosphatases.

Q: Your research is primarily focused on the clinical development of “allosteric EGFR inhibitors” for drug-resistant lung cancers. What are these and why are they important for lung cancer?

A: Many therapeutics work by binding to specifically shaped pockets in the cancer-causing molecule. Some patients treated with EGFR inhibitors become resistant to these therapeutics. This resistance is often due to changes in the shape of the protein molecule near where the drugs bind, and it is particularly difficult to develop new drugs that bind to the altered

mediates resistance to DNA damaging agents, such as radiation therapy, in breast cancer and other cancer types. Interestingly, this same cellular enzyme is well known for preventing HIV infection. Vpx, a protein that supports HIV-2, degrades SAMHD1. We exploited this natural way for HIV-2 to degrade SAMHD1 by packaging Vpx in virus-like particles. We showed that these particles can degrade SAMHD1 in breast cancer cells and tumors and can make cancer cells and tumors vulnerable to radiation therapy.

Q: What are you most excited about?

A: We are investigating our strategy of using the virus-like particles containing Vpx to help stem-cell-like CD8+ T cells mature. These cells then kill infected or malignant cells and make it possible to treat breast cancer with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. This enables the body's natural defenses to recognize and attack cancer cells more effectively.

binding site found in some patients’ tumors. We are tackling this problem by developing drugs that bind to alternative, or allosteric, pockets in the protein whose shape has not changed. These allosteric inhibitors can be used to treat patients who are resistant to other therapeutic options.

Q: Your lab is also interested in studying kinases and phosphatases. What are they and what are their normal roles compared to what happens to them in cancer?

A: Signals to grow or not are often transmitted through our cells by proteins called kinases and phosphatases. These signals involve the addition or removal of a phosphate group from a series of molecules in a specific order. Kinases and phosphatases add and remove phosphates, respectively, and careful balance is needed between the two for proper health. When kinases or phosphatases abnormally function, usually as the result of genetic mutations, the wrong signals are sent through our cells. In cancers, growth signals are always being sent, causing cells to grow uncontrollably. Many therapeutics work by altering the function of kinases or phosphatases to stop the unwanted growth signals from being transmitted.

XU JI is a member of Winship’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program and an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine. Her research focuses on leveraging her quantitative research skills and theoretical grounding in health services research for improved pediatric cancer care and cancer survivorship.

Q. Why are big data analysis, administrative data, data linkage and statistical modeling important for pediatric cancer care and survivorship?

A: The novel linkages and statistical application of population-based data (e.g., administrative insurance records, medical records, cancer registries, geospatial data) allow the generation of rigorous, realworld evidence pertaining to the gaps in health and health care after a diagnosis of pediatric cancer. Such evidence informs new interventions in clinical practice and health policy changes designed to improve the lives of people with, and survivors of, pediatric cancer.

Q. How you are able to leverage your quantitative research skills and theoretical grounding in health

SARWISH RAFIQ is a member of the Cancer Immunology Research Program at Winship Cancer Institute, program leader for Winship’s CAR T Basic/Translational Research and an assistant professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. She is a translational research scientist with a broad background in the preclinical development of immune-based treatments for cancer.

Q: Why is immunotherapy such a powerful approach to treating cancer?

A: The immune system is the body’s natural defense mechanism against infections and diseases such as cancer. However, cancer cells often develop mechanisms to evade detection by the immune system. Immunotherapy aims to boost the body’s immune response against cancer. There are many advantages to this approach. Immunotherapy can be more precise and target cancer cells specifically while sparing normal, healthy cells. Furthermore, this type of treatment can create a lasting effect on the immune system, called immunological memory, wherein immune cells may continue to patrol the body, recognizing and eliminating cancer cells even after the initial treatment.

services research to benefit pediatric cancer care and survivorship?

A: To launch my research career in pediatric cancer care and cancer survivorship, I received internal funding that allowed me to analyze administrative Medicaid data to examine insurance issues among pediatric cancer survivors. We found that a substantial proportion of survivors (ranging from 24% to 47%, depending on the specific survivor cohort under study) were insured with Medicaid. Among these, over one-half experienced gaps in Medicaid coverage and in their care. These gaps were associated with inferior cancer outcomes compared to those with private insurance or uninterrupted Medicaid.

In one study, my colleagues and I linked Medicaid insurance data to the established cohort from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, a retrospective cohort of 30,803 adult survivors of pediatric cancer recruited from 30 institutions across the U.S. who were diagnosed between 1970-1999. We used the linked dataset to quantify patterns of health care utilization among Medicaid-insured survivors, overall and by sociodemographic groups, following Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

Finally, as the immune system is highly dynamic and can evolve to recognize new threats, immunotherapy has the potential to adapt to changes in cancer cells to avoid resistance to treatment.

Q: What obstacles remain in expanding CAR T technology for more widespread use in cancer?

A: CAR T-cells are a type of treatment in which a patient’s T-cells (a type of immune system cell) are changed in the laboratory so they will attack cancer cells. Although CAR T-cells have been remarkably effective against certain types of blood cancer, expanding the number of patients who can benefit from this therapy faces challenges. First, the process of engineering personalized T-cells for each patient is complex and resource-intensive. High costs can limit accessibility, making it challenging for many patients to afford this treatment. The time it takes to manufacture CAR T-cells can also be a challenge. In some cases, patients with rapidly progressing cancers may not have enough time to wait for the production of personalized CAR T-cells. Current research is looking at ways to create a more “off-the-shelf” CAR T-cell product that can be universally used in patients. Finally, CAR T-cells can be suppressed in the microenvironment of tumors, especially for solid tumors. Maintaining or boosting their efficacy here is an active area of research. w

Nearly a decade ago, Winship Cancer Institute head and neck cancer specialist and medical oncologist Nabil Saba, MD, helped diagnose a patient with what looked like easily treatable tonsil cancer.

“We told him, ‘You have a 95% chance or higher to get cured from this,’” Saba recalls.

Sometimes in cancer, though, the statistics don’t pan out in a patient’s favor, even an athlete in his early 30s. “Despite the clinical picture,” says Saba, “he had recurrent disease that was metastatic and that was not at the time responsive to treatment.”

Saba, The Lynne and Howard Halpern Chair in Head and Neck Cancer Research at Winship and professor and vice chair for quality and safety in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine, says, “The human eye is limited. We only rely on what we see in front of us—the pathologic diagnosis and the scans.”

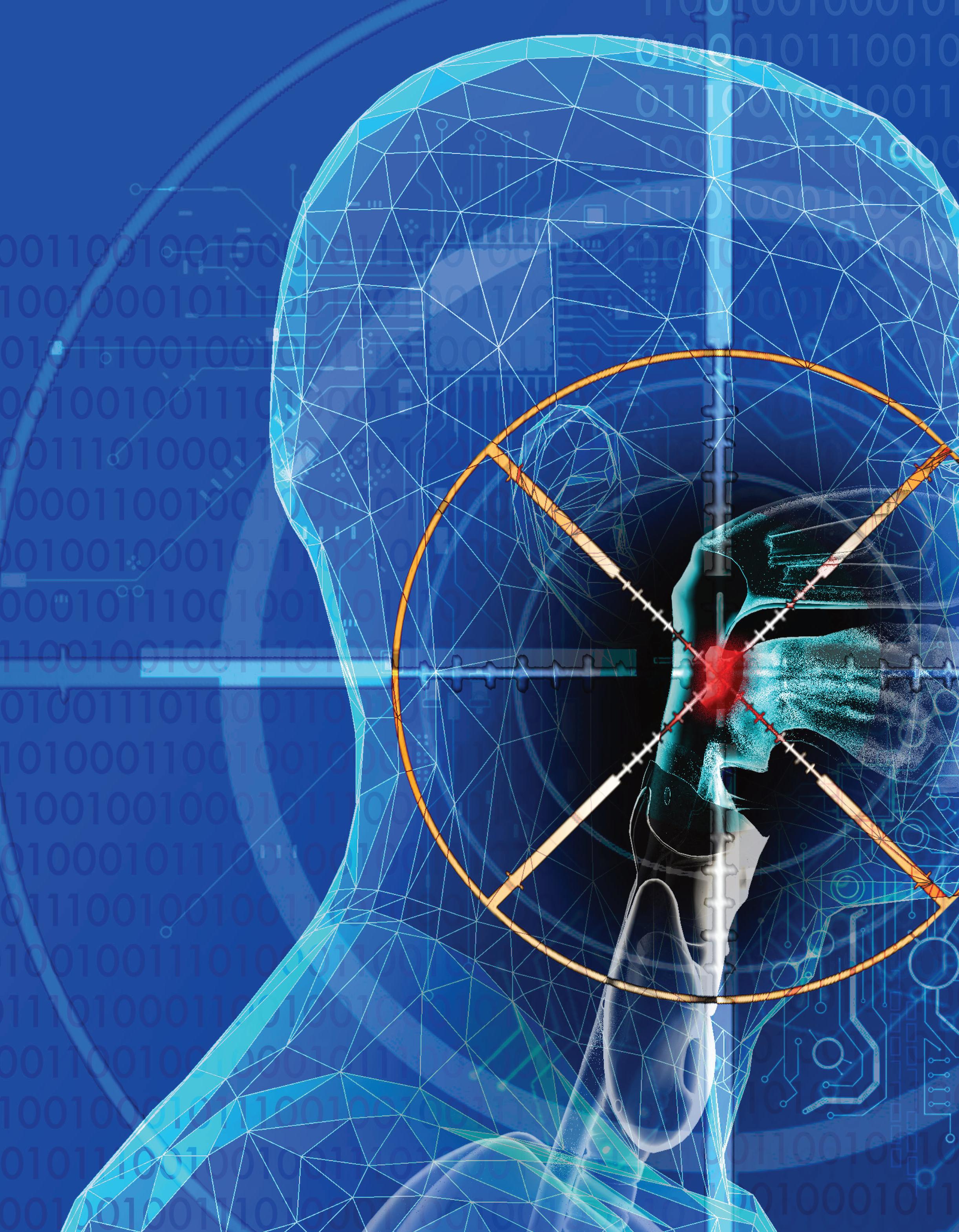

Today, Winship is home to a host of cutting-edge research in artificial intelligence (AI) that has the potential to drastically shift how physicians approach cancer care, from diagnosis to treatment to long-term survivorship. Powerful programs are available to support human eyes, able to recognize patterns, connections and warning signs far below our sensory thresholds.

reimagine how doctors diagnose and treat cancer. In this setting, the AI-related work at Winship happening across fields and types of cancers has the potential to help turn widespread precision medicine from a pipe dream into the new standard of care. It can help to increase the efficiency and accuracy of radiology work, and even forge more equity in a field with stubbornly persistent racial disparities in patient outcomes.

Recalling his patient with tonsil cancer, Saba says, “I think perhaps AI could have detected that this is not your regular-behaving HPV-related disease. If we had known about this outcome, we would have treated these patients differently from the beginning.”

From the realm of science fiction to a sudden, very real reality, artificial intelligence is here—and it’s rapidly shifting the fundamentals of how we live and work.

From handy uses like digital personal assistants to more insidious applications like deepfakes—realistic but false digital recreations of celebrities saying things they never really said, or fabricated news footage that spreads misinformation—AI harnesses machine learning algorithms and neural networks to teach computers how to perform what was previously inconceivable. AI creates in ways that were once open only to human minds, and on a scale far vaster than our brains can conceptualize unaided.

“As we get more and more information, there are only so many crunches that we can do as humans,” says Sunil Badve, MD, a member of Winship’s Cell and Molecular Biology Research Program and professor and vice chair of pathology cancer programs in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine of Emory University School of Medicine. “That’s when computers come in and start crunching all these different relationships. Out of the whole haystack, all these needles are pulled out and brought together, and now we can have a better understanding of what’s going on.”

“ As we get more and more information, there are only so many crunches that we can do as humans.”

Sunil Badve, MD

Anant Madabhushi, PhD, a member of Winship’s Cancer Immunology Research Program, is deeply and publicly involved in Emory’s AI work. A professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, Madabhushi holds secondary appointments in the Departments of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Biomedical Informatics (BMI) and Pathology. Madabhushi collaborates with faculty across numerous disciplines to discover the potential of AI in cancer detection, treatment and survivorship. He is also the executive director of the Emory Empathetic for AI Health Institute (Empathi), which launched in November 2023.

This revolution reaches into scientific discovery at Winship, where researchers are increasingly using the tools of AI to

Empathi, under the umbrella of Emory’s campuswide AI.Humanity Initiative, seeks to harness AI to improve cancer detection, risk and treatment response predictions. And it seeks

to do so in studies that incorporate AI technology from the start. Utilizing AI in research from the start represents a push forward from the current status quo, where most work is retrospective, since algorithms need to learn on big sets of pre-existing data. Madabhushi says this approach will provide tools to better stratify risk before treatment and to monitor the patient’s response early on.

AI-related research at Winship could ultimately change cancer medicine by offering the option of less extreme regimens with fewer side effects for cancers less likely to recur. “Our goal is not just to develop algorithms from a diagnostic perspective, but also to be able to prognosticate disease outcome and predict therapeutic response,” says Madabhushi.

causality—the likelihood—of therapeutic benefit, and ultimately whether the patient is going to survive,” says Badve. He has been collaborating with Madabhushi since 2015 on using AI to predict which cases of DCIS, or “stage 0” breast cancer, will progress to invasive disease. “Survival is the goal,” he says. “Can we predict it based on whatever parameters we have?”

Badve’s own work looks at breast cancer using multi-omics— or multiple biological systems, such as the microbiome and the genome—to discover patterns and relationships. “As you increase the dimensionality of the data, you’re going to be able to understand more facets,” he says.

The increased information also allows algorithms to start identifying things through increasingly smaller fragments. “If we are familiar with somebody, we can see their back or the way they walk and know who it is,” says Badve. Similarly, we recognize known faces while iPhone facial recognition “knows” the same face by analyzing collections of data points. The idea for AI, Badve says, is that computers “get better and better at recognizing things even without 100% of the image being there.”

In 2022, Madabhushi and his co-authors published a paper in the journal Science demonstrating, for the first time, that the appearance of the vasculature (arrangement of blood vessels) around a lung tumor is indicative of whether or not the cancer is likely to spread. The vessels feeding tumors are more “twisted” in cases where they are likelier to be treatment resistant. In more responsive tumors, the vasculature appeared more orderly. AI could recognize this patterning because of its ability to detect subtle patterns within large, unwieldy data sets.

The new knowledge could potentially help doctors see how treatments are working before standard indicators, like change in tumor size, are visible. “AI is now prizing out subtle hallmarks that might give us earlier evidence of treatment response or lack thereof,” Madabhushi says.

AI’s ability to analyze huge quantities of data and detect patterns that human eyes can’t discern unaided is one way the technology may completely change the course of cancer diagnoses and treatments, alerting doctors to disease indicators yet to be discovered.

“What we are trying to do in cancer research is forecast the

AI-based pattern detection reaches beyond what’s happening inside a patient’s body. Abeed Sarker, PhD, a member of Winship’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program and an associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Informatics at Emory University School of Medicine, uses machine learning to scrape social media datasets to learn what people discuss in community and how it differs from what they say to physicians. In his collaborations with Winship, Sarker has pulled information from patients with breast cancer tweeting about their experiences on why many of them—especially younger patients—don’t adhere to some medical recommendations. These are the type of data that are rarely gathered by physicians and, if they are, are unlikely to be recorded in patient electronic health records.

Sarker wondered whether there are other sources of information that can be used to identify why people are not adhering. He and collaborators Mylin Torres, MD, a breast cancer expert and researcher who co-leads Winship’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program, and Mayo Clinic AI scientist Imon Banerjee, PhD, built an algorithm and a data set of patients with cancer tweeting about their experiences.

“We saw a lot of breast cancer survivors on whom the treat ments are working fine, but it’s impacting their everyday lives,” Sarker says. “That is specifically a problem with younger people, because they may want to keep their social lives active, and these cancer treatments are not allowing them to.”

define the target,” says Xiaofeng Yang, PhD, DABR, a member of Winship’s Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics Research Program and an associate professor and vice chair for medical physics research in the Department of Radiation Oncology of Emory University School of Medicine. Yang’s work integrates machine learning with MRI to improve predictions of tumor recurrence and decrease the amount of time it takes to read the images needed to diagnose and create treatment plans. For example, he says, it takes doctors about two hours to manually map out radiation pathways for head and neck cancer treatment. With AI assistance, that work can get done in under half an hour, saving valuable time and resources.

The team earlier presented a conference poster that explored the feasibility of combining electronic health records with social media posts. Most Winship patients approached for that research were happy to provide access to both platforms to seek new insights.

“These language models identify patterns in language that are generalizable and that can detect information such as disclosure of breast cancer status, disclosure of side effects, disclosure of sentiment,” Sarker says. “One person saying something does not really make a signal. If there are hundreds of people associating negative sentiment with a medication, that is a signal.”

Another major focus of Winship’s research at the intersection of AI and cancer involves using the technology to improve the precision of diagnoses and treatment planning. This helps to better individualize treatments for each patient while saving radiologists time and improving their accuracy. Which is to say, researchers are using AI in cancer diagnosis to realize the potential of precision medicine.

“We want to use advanced imaging to more accurately

Yang’s research also looks at incorporating AI into medical imaging. This can help personalize treatments by, for example, using stronger protocols for cancers that are more likely to recur, or identifying tumor borders with increased precision to allow for more targeted radiation. This lessens the chance of severe side effects that occur with larger tumor borders.

Besides personalizing standard treatments, this AI-aided pattern recognition can help realize the potential of personalized (precision) medicine, which creates protocols specifically tailored to a patient’s own biology. It’s long been considered, but has yet to become, the gold standard toward which many cancer treatments are heading.

“The response rates for immunotherapy are something like 20% to 25%,” says Madabhushi, referring to the type of personalized medicine that harnesses patients’ own immune systems to help eradicate disease. He says that using AI in pattern recognition before treatment helps to predict which patients will respond or not, again helping to hone precision medicine’s potential. AI can then help radiologists track whether treatments are working.

“People are notoriously bad at measuring things,” says Elizabeth Krupinski, PhD, a member of Winship’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program and professor and vice chair for research in the Department of Radiology and Imaging

Sciences at Emory University School of Medicine. “People make mistakes. It’s very hard sometimes to measure tumor changes as a function of growth.” She adds, “Computers are far more consistent at the very least in what they measure and how they measure things.”

Krupinski, an experimental psychologist, looks at how radiologists incorporate AI into their workflows, and how they can do so in ways most likely to increase diagnostic efficiency and decrease errors.

Imaging Technology News called this a “crisis,” because “there are just not enough of us to get the work done.”

Krupinski says things are going to change “in a pretty significant way.” She cited the example of using mammograms to diagnose the presence of breast cancers. “The frequency of finding cancers is relatively low,” she says. “If an AI system could triage cases with a very high degree of certainty, finding cases that are truly negative, it would dramatically change the way mammographers read images. And it’s going to give them more time to look at the images where the AI thinks something is going on.”

AI can be presented in a number of ways. “There are heat maps, probability maps and sometimes there are little arrows pointing or segmentation,” Krupinski says. “You can give a lot of different kinds of information to somebody and you have three choices: it can have zero impact, it can have a positive impact or it can have a negative impact.” She assesses impacts through eye gaze and medical decision-making studies, giving radiologists AI tools and watching how they use them to see how they might do so more effectively. “If I can help radiologists decrease those error rates—to help them improve their performance and diagnose the images more accurately—that’s where I see my role,” she says.

Just like virtually every other metric of health and well-being in the United States, cancer diagnosis and survival rates contain racebased disparities. Although white people are most likely to be diagnosed with cancer in this country, Black and Indigenous people are more likely to die from it. To cite just one specific example, Black women are diagnosed with breast cancer 4% less frequently than white women are, but have a 40% higher mortality rate.

Fellow Winship Cancer Prevention and Control researcher Judy Wawira Gichoya, MD, MS, associate professor in the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences at Emory University School of Medicine, has found that using AI to weed out malignancy currently decreases radiologists’ accuracy, because they don’t tend to double-check the images that AI labels benign as closely.

Learning how to work with AI’s capabilities instead of against it could be a game-changer. Technology that helps radiologists flag scans with a high likelihood of malignancy has the potential of improving both speed and accuracy, while lightening the load on overworked doctors.

Radiologists review upwards of hundreds of images daily, in long shifts that increase the chances of error. Some 54% of radiologists suffer from burnout, according to a 2022 Medscape report.

While systemic racism has produced a multitude of factors that create and perpetuate discrepancies, AI has the potential to help diminish them—but only if the algorithms are trained on data sets that include sufficient representation from all races and ethnicities.

Like most medical research, existing AI algorithms are primarily trained on data sets made up of disproportionately white patients. The implications are huge: if diseases present differently across races, and machines can only accurately predict patterns as they appear in one of them, deploying AI more widely will only increase health care disparities as algorithms reinforce biased recognition patterns.

“The goal is that we have to make sure that these tools really work across a plurality of populations,” says Madabhushi.

Winship researchers repeatedly note that one strength of the institute’s research program is that it treats a remarkably diverse

patient population, allowing their AI to train on data sets more representative of the global population.

Madabhushi says it’s difficult to interpret the where, how and why of AI’s algorithms. “While it can generate some pretty amazing, unexpected predictions or results,” he says, “the challenge is that it is very unclear as to what the basis or the bedrock of those predictions is.” This means that if the system ends up being biased, it’s basically impossible to understand where it went offtrack.

The demographic advantage of being located in Atlanta and serving the area’s diverse patients is prioritized by many of Winship’s AI researchers, who stress that building equity into new technologies is essential. “I don’t think there is any place like Emory Healthcare and Winship that has such diversity in their cohorts,” Sarker says. “I think it’s very unique in the United States.”

Gichoya says her work as a member of Winship’s Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program, and a core part of Empathi, is about “promoting health equity using data science.” She compiles diverse data sets with multiple types of imaging—such as pathology and radiology pictures—“to leverage images that are routinely acquired to see what else they can tell us about the patient,” and to expand researcher access to these sorts of resources. She says AI’s scaled pattern recognition ability can identify the “hidden signals” in images that human eyes wouldn’t identify as significant. This presents many opportunities, says Gichoya, such as her and her collaborators’ finding that it’s possible to identify a patient’s race with high accuracy using AI to look at patient imaging.

This and other indicators can give information about “how fast you’re aging, what sort of area you live in, your sex,” Gichoya says. It can allow physicians to learn about how people live, what their prognosis might be and how to tailor treatments accordingly. Badve notes that combining a multidimensional analysis of tumors with patient demographics might allow for more accurate predictions of how the cancer will behave, again leading to more personalized treatments.

The research focus on realizing the great potential—and avoiding the pitfalls—of AI may well have broad impacts on patient health as Winship methods, technologies and mentees proliferate. But all the innovation is ultimately aimed at one thing: helping the next patient facing a terrifying cancer diagnosis get the best possible chance at recovery and a long, symptom-free survival.

“I think it has a great potential to change things rapidly for us,” Saba says, “to hopefully lead to faster discoveries and better translation to improving care for patients.” w

Small victories are key to staying strong during long treatments

by John-Manuel AndrioteIt started with a spot on his forehead in January 2020. Turned out it was a type of skin cancer, squamous cell carcinoma. As the COVID-19 pandemic got under way that winter and spring, Keith Sievers was receiving radiation treatment.

Six months into his treatment, though, Sievers noticed a lump in his neck. That’s when an ear, nose and throat surgeon at a local community hospital, where he was being treated, recommended he pursue the surgery he needed at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University.

The surgeon said the procedure would be “delicate” because of its proximity to the nerves and major arteries that pass through the neck. “You need a surgeon who does this all day, every day,” Sievers recalls him as saying. “I could certainly operate on you, but you need to be at Winship.”

Sievers credits that surgeon’s referral to Winship as “the” key contribution toward saving his life.

Like other new Winship patients, Sievers—together with his wife, Robin Sievers—came in to meet the Winship team who would be caring for him.

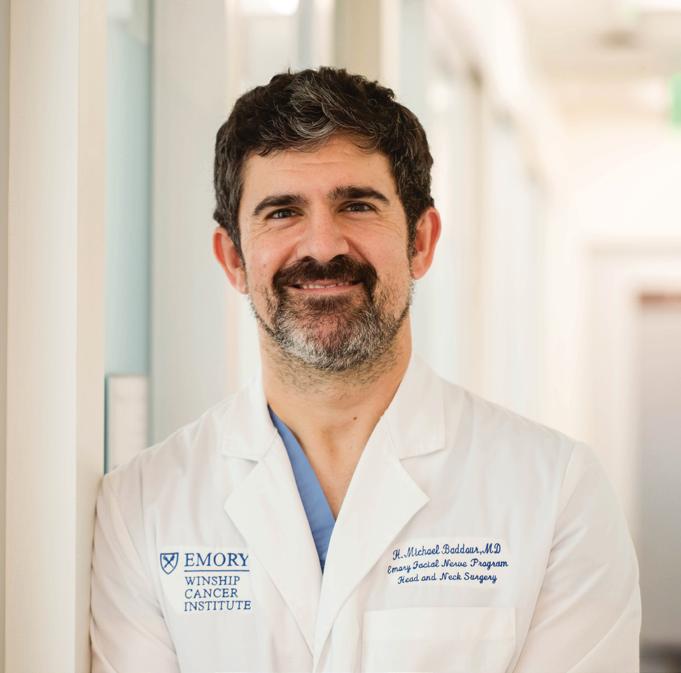

The surgery would be performed by H. Michael Baddour, Jr., MD, an expert in head and neck surgical oncology and complex microvascular reconstruction at Winship, and associate professor in the Department of Otolaryngology at Emory University School of Medicine.

His team also included Soumon Rudra, MD, a Winship researcher and radiation oncologist specializing in the treatment of head and neck cancer and gastrointestinal cancer, and assistant professor at Emory University School of Medicine.

His medical oncologist was Nabil F. Saba, MD, FACP, director of Head and Neck Oncology and the Lynne and Howard Halpern Chair in Head and Neck Cancer Research at Winship and professor at Emory University School of Medicine.

The daylong visit also included meetings with a dental oncologist, pharmacologist, speech therapist and even a swallowing therapist.

Baddour emphasizes that Sievers himself—and each one of his other patients—is “the primary person on the team.” He explains, “They are the ultimate decision-makers driving their own care. And I feel like the only way

they can make a decision is if they have all the information.”

Saba says, “Having patients actively participate in the decision-making is important to navigate the complex treatment programs.” He adds, “I think trust is a key ingredient of success.”

Sievers agrees. “You have to trust your doctors,” he says. “You have to stay with them. You have to take their advice. It’s important that you really understand the options and the treatments. Don’t be afraid to ask questions.”

Most important of all, says Sievers, is to recognize in the partnership “how hard these people are working, and how difficult their jobs are. You really have to show them that you respect what they’re doing, and that you appreciate them.”

Sievers’ team recommended the surgery. He had the surgery within a couple of weeks, followed by proton radiation therapy.

Complicating an already difficult experience, Sievers’ personal drama played out against the backdrop of the growing COVID19 pandemic. Loved ones were routinely barred from visiting family members or friends in hospitals because of the rampant fear of contagion. “I had to drop him off at the curb for the surgery,” Robin Sievers recalls. “I couldn't go in the hospital, and that was hard for both of us.”

By the end of his second year with cancer—which had included surgery, proton therapy and recovery—Sievers was receiving scans every three months. That’s

how he found out the cancer had spread into his lung. “It was a fairly significant tumor,” he says with understatement.

Both Sievers met with Saba. This time Saba explained that going after the tumor with radiotherapy may not be sufficient to achieve long-term control; “zapping it” couldn’t guarantee Keith’s survival when the cancer already had recurred before. He recalls Saba as saying, “Look, it’s spread three times. We need to be concerned about the bigger picture.”

After discussing traditional treatments as well as potential treatments being tested in clinical trials, “We elected to go with the trial,” says Sievers.

As it happens, the choice to participate in the clinical trial was an auspicious one.

“At the end of five months,” says Sievers, “the tumor was gone, a complete response.” He adds, “And, knock on wood, I’ve been clean ever since.”

Getting to this point was not easy. Every two weeks, the Sievers made the 70-mile drive each way from their home in the north Georgia mountains to Atlanta, so Keith could receive what he calls “a miracle drug” because of how he says it “really stamped out the cancer.” The drug was an immunotherapy drug being tested in the trial with or without another agent called cetuximab.

As of the time of our

not

Keith defied the odds after his surgeries, when he only played 18 holes at Hilton Head but walked the entire distance. (Photo credit: Robin Sievers)

interview, in December 2023, Sievers returns to Winship every three months for a set of scans, and every six weeks to have the port flushed. He doesn’t even have to take maintenance medication.

Rudra, like Sievers’ other care team members, marvels at Sievers’ active participation in his own care.

“I just want to note,” Rudra says, “how thoughtful and considerate Keith was in his decision to enroll in a clinical trial.” He points out that enrolling in a clinical trial doesn’t guarantee a good outcome. “Yet Keith did it because he thought he could help future patients.” He adds, “Keith and Robin spent significant amounts of time traveling and answering extra questions about his treatments due to his clinical trial participation.”

For Keith Sievers, with Robin at his side the entire time, the sacrifice of time and effort seemed like nothing when compared to the potential payoff: improving his own health and contributing to the advancement of research that could benefit others. It was a natural outgrowth of the couple’s operating philosophy.

Keith explained that after his

initial diagnosis, he found three things to be the most challenging to deal with. First, he says, is facing your mortality. “You always are aware of it, but you really have to look it in the eye, and that just takes some time to let it settle in.”

Then there is the fear of the unknown, about “what’s going to happen next,” and a lot of uncertainty. Finally, there is the waiting—for appointments, for procedures, for results. Every step takes time.

“Once you get through the uncertainty,” Sievers says, “and once you get into the battle and you’re doing something about it, you really feel like now you’ve got some control—and that’s really helpful for people.”

He had to push past claustrophobia to be able to remain strapped to a table for 45 minutes—with a full facial mask covering his face—to receive proton therapy on his neck. “I took pride in that,” he says.

“Winning those little victories is uplifting to people,” Sievers says. “If you look at it like a fight, and you look at it like, ‘I may lose a battle or two along the way, but I’m going to win this war’ and you really focus

on winning the battles, that really is uplifting and helps to win the war.” w

First lady Jill Biden visited Emory University September 15 to learn about groundbreaking research focused on training the immune system to prevent, treat and cure cancers and other diseases.

Hope surged when President Joe Biden and First Lady Jill Biden reignited the Cancer Moonshot in 2022 after it first launched in 2016. The program’s goal is to “end cancer as we know it”— reducing cancer mortality by at least 50% within the next 25 years and improving the effect of cancer on patients, their families and caregivers.

Achieving this bold vision requires a strategy. That’s exactly what the National Cancer Institute (NCI) rolled out in its comprehensive National Cancer Plan. The plan’s focus is “to achieve a society where every person with cancer lives a full and active life, and to prevent most cancers so that few people need to face this diagnosis.”

The National Cancer Plan establishes eight goals (see sidebar, page 20) we must achieve to prevent cancer, reduce mortality from cancer and maximize quality of life for people living with cancer. The plan describes the goals as “aspirational statements, describing an ideal future, and represent opportunities for everyone and every organization to contribute to our continued progress against cancer.”

As Georgia’s only NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, Winship already is working to end cancer as we know it, says Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, FACP, FASCO, Winship’s executive director and the Robert C. Goizueta Chair for Cancer Research at Emory University School of Medicine. “Winship has programs, projects and centers already in place that are addressing the key objectives of the National Cancer Plan,” he says.

This isn’t coincidental. Kimberly F. Kerstann, PhD, Winship’s chief administrative officer and associate director for research administration, explains that the NCI’s Office of Cancer Centers— the entity that evaluates and supports cancer centers for NCI

Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, FACP, FASCO

designation —uses its NCI designation review and approval process to “guide us in how we align our work in support of the strategic plan of the NCI.”

This process ensures that all 72 NCIdesignated Cancer Centers nationwide are working toward improvements that help us accomplish the goals of reducing cancer mortality by 50% and changing the experience of cancer.

To illustrate how Winship plays an important role in helping to achieve the Cancer Moonshot, Kerstann points to the recent three-year, $24.8 million award from the new federal Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) to Winship researcher Philip Santangelo, PhD, a professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Emory and Georgia Institute of Technology. The first-ever ARPA-H cooperative agreement will support the development of a cutting-edge programmable approach to prevent, treat and potentially cure diseases such as cancer, autoimmune disorders and infectious diseases.

After the award was announced, First Lady Jill Biden visited Emory in September 2023 to see Santangelo’s lab, underscoring the importance of his work

to the Cancer Moonshot’s goals of preventing and developing effective treatments for cancer.

Beyond the ARPA-H project, Winship’s researchers have been instrumental in developing some of the most widely used cancer treatments. Winship research has led to 145 patents for new cancer therapies, and two-thirds of today’s FDA-approved cancer treatments were available in clinical trials at Winship prior to receiving FDA approval. Winship contributes to the National Cancer Plan’s goal of delivering optimal care by integrating its research breakthroughs into our cancer care to provide the very best care available. Each year Winship serves more than 17,000 patients newly diagnosed with cancer. The care they receive is provided by leading cancer specialists collaborating across disciplines to tailor treatment plans to their needs. They are also offered innovative therapies and clinical trials, comprehensive patient and family support services and a care experience aimed at easing the burden of cancer.

While the NCI identifies their highlevel strategy, Kerstann says, “We as NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers are mandated to understand the needs of the population within our particular catchment (service) area, and implement strategies based on those particular needs.” She says that because Winship serves the unique, diverse population of Georgia, “it’s important for us

5.

7.

8.

to take that local information back to the national group to ensure that the interests of Georgia are represented.”

Winship’s community is very diverse. Ramalingam notes that more than half of Georgia’s people belong to minority communities. Besides serving patients from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, Winship’s catchment area also includes Georgians in rural areas, given that 77% of Georgia’s landmass is defined as rural.

“Living in a very diverse state,” says Ramalingam, “we are reminded every day, during these encounters with our patients and communities, the extent of inequities that exist at various levels. We know that disparities exist not just based on race, but also on a rural vs. urban basis, and other various factors.”

Addressing these disparities—by race or ethnicity, geographic location, socioeconomic status or other factors—has long been a top priority at Winship, even before the National Cancer Plan made eliminating inequities its fourth goal.

“Our focus,” Ramalingam says, “is to eliminate inequities so everyone has access to cutting-edge advances and the opportunity to participate in research.”

Winship works actively to engage people in our research. Engaging the community in all types and phases of cancer research brings important societal issues and the lived experience of Georgians to the forefront, informing scientists in ways that lead to studies that are more responsive to the needs of Georgia communities. Engaging community members as partners in research also helps foster a collaborative and ethical foundation for scientific discovery.

To help eliminate inequities and ensure equal access to research, a

philanthropic gift allowed Winship in 2023 to create the Winship Center for Cancer Health Equity Research (see sidebar on page 23). Ramalingam says, “I think the Center will help us take our programs and research in disparities to an even higher level.”

Population sciences research at Winship is “closely engaged with” the National Cancer Plan’s number one goal: to prevent cancer, says Timothy L. Lash, DSc, MPH, Winship’s associate director of population sciences and the Rollins Professor and Chair of the Department of Epidemiology in the Rollins School of Public Health.

Lash says, “If you think about where there’s opportunities for cancer prevention, it starts with tobacco control, and especially in a state like Georgia, where tobacco prevalence is higher than in some states.” For this reason, he calls tobacco cessation Winship’s number-one focus for cancer prevention research. Second is weight gain, which is

critically important not only for preventing heart disease and diabetes but also for cancer. “Among people who are not tobacco smokers, with no history of tobacco use, excess weight is probably the most common risk factor for cancer, and it’s related to all types of cancer,” Lash says.

Third is HPV vaccination, which prevents human papillomavirus—a known risk factor for cervical cancer, head and neck cancers, oral cancers, and cancers of the anus, vagina and penis. “There’s an effective vaccine, but the uptake of the vaccine is highly variable by geography,” says Lash.

A fourth top focus of Winship’s cancer prevention research is sun safety. Then there are smaller but still important risk factors, such as alcohol use and occupational hazards such as radiation and asbestos. “The American Cancer Society says that we know how to prevent 70% of cancers already,” says Lash. “We know how to prevent a lot of cancer.”

An important key to preventing a lot of late-stage cancers is regular screenings that can detect cancer early and permit intervention before they become more difficult to treat. Winship’s scientists research evidence-based interventions and programs that increase screening and early detection. Winship created the website Your Connection to Early Detection to provide Georgia residents with a comprehensive resource for finding low-cost cancer screenings in their local area.

The availability and use of data is

“the basic foundation of everything we do at Winship,” says Madhusmita Behera, PhD, Winship’s chief informatics and data officer, noting that maximizing data utility is the seventh goal of the National Cancer Plan. In her role, Behera has been able to enhance and build a data infrastructure “that has immensely supported our research and operations, including our clinical trials.”

The data Winship collects and analyzes comes from a variety of sources— including clinical data, genomics data and imaging data. Behera says the data are important in helping to notice trends for scientific discoveries, answer research questions related to patient outcomes, patient treatment response and patient safety. “We need it for all of those critical components of cancer research and clinical care,” she says.

Behera points out that “a huge part” of the Winship clinical staff’s daily responsibilities involve accessing electronic health records (EHR) for clinical operations. “The fact that we have made it easier for accessing data of that nature makes it all the more important for how we care for our patients,” she says, adding that data also “have really allowed us

to provide the opportunity for clinical trials participation to a large number of patients.”

The eighth goal of the National Cancer Plan is optimizing the workforce. This means cultivating a diverse workforce that “reflects the communities served and meets the needs of all people with cancer and those at risk for cancer.”

Educating and training the people who comprise Winship’s clinical and research teams has long been a priority for Winship (see the story in Winship Magazine’s Summer 2023 issue).

Winship Deputy Director Adam Marcus, PhD, Winship 5K Research Professor in the Emory Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, points to Winship’s full range of educational programs for learners of all ages and career levels. “Many of our training programs span learners of a variety of ages and a variety of steps in their career,” he says. “That’s to really ensure that we’re training the next generation and that the next generation of the health care and research workforce is indeed diverse.”

Winship has a tripartite mission of providing clinical care, conducting research and educating the current and future workforce. “Education is also a focus of the National Cancer Plan,”

says Lawrence Boise, PhD, Winship’s associate director for education and training and the R. Randall Rollins Chair in Oncology in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. Decades before the National Cancer Plan, Winship was committed to educating future clinicians and researchers as part of a major university. Today, Boise says, “Winship has programs that start from as early as middle school, through career development programs for faculty members.”

Boise emphasizes that while it’s important to build the workforce, it’s equally important to build a diverse workforce. “We all recognize that we strengthen our opportunities by diversifying our workforce. We also recognize that students want to train with people that they can identify with, and patients often want to be seen by people they can identify with,” he says. It has to do, in part, with a “feeling of trust.”

Ildemaro J. Gonzalez, MBA, Winship’s chief diversity officer, says the NCI measures and evaluates the efforts to achieve diversity within NCIdesignated Comprehensive Cancer Centers as part of its criteria for designation. “We have to show and demonstrate our efforts,” says Gonzalez. He explains that doing so entails four aims: (1) having the right infrastructure; (2) growing

the pipelines of future clinicians and researchers; (3) recruiting individuals from under-represented populations; and (4) accountability.

Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) matter to patient outcomes and to understanding the disease, says Gonzalez. “We want to diversify the participants in our clinical trials so that then our findings are applicable to a broader group of the population.” DEI also matters to Winship’s workforce. “This is not about counting the numbers,” Gonzalez says. “This is not about ‘I have three Hispanic faculty members, two African American and so on.’ This is about what their perspective, research and expertise bring to our patients and to the science.”

Whether they are developing evidence-based cancer prevention interventions, educating future researchers and clinicians or directly caring for our patients, Winship’s workforce is dedicated to changing cancer as we know it.

As Ramalingam puts it, “Our program’s focus on cancer prevention, early detection, treatment, care, community engagement, diversifying our workforce, utilizing data and reducing inequities, and are highly aligned with the goals of the National Cancer Plan.” w

Goal 4 of the National Cancer Plan is to eliminate inequities in cancer care. These include risk factors, incidence, treatment side effects and mortality. Eliminating these disparities requires equitable access to prevention, screening, treatment and survivorship care.

Reducing the burden of cancer and promoting cancer health equity throughout Georgia are at the heart of the mission of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University. To support its efforts, Winship created a new Winship Center for Cancer Health Equity Research to focus on eliminating cancer disparities in Georgia and nationwide.

“Winship has a long history of working toward more equitable cancer health outcomes, and this strategic focus will accelerate our efforts in significant ways,” says Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, Winship’s executive director.

Theresa Wicklin Gillespie, PhD, Winship’s associate director for community outreach and engagement and the new center’s inaugural director, calls it “a golden opportunity.” She explains, “The time is right to have a center like this, so that we can make a real impact in terms of the lack of equity in cancer health outcomes.”

The center is made possible by generous gifts from the Wilbur and Hilda Glenn Family Foundation and Southern Company. It will address cancer disparities by examining biological, behavioral and social factors affecting cancer development, risk and response to therapy. It will fund new studies, strengthen collaborations and improve representation in Winship’s clinical trials.

Winship’s center will be unique in two ways among the nation’s cancer centers that have developed their own centers focused on cancer health equity. First, the center will focus on research across the entire continuum of cancer research. Gillespie says, “This means that the center encourages investigators to pursue basic, translational, clinical and population science research examining underlying basic mechanisms, factors that impact and viable solutions related to cancer health equity.”

Second, the center will focus on the costs and cost-effectiveness of interventions in order to promote policy changes. “Often,” says Gillespie, “interventions or therapeutics are not always concerned about the costs or cost-effectiveness.” Although they provide good measures of how well resources are being used to produce the desired outcome— reducing the burden of cancer—Gillespie says costs and cost-effectiveness “are often not included in many research studies.” This is despite the fact that, “policy changes may be dependent on demonstrating how much certain interventions may cost and, most importantly, how cost-effective they are and how well they contribute to the key outcomes in cancer.”

The center also will be different by intentionally incorporating a variety of perspectives in its research and the interventions it develops—perspectives from the community, patients, health care providers and disciplines across the continuum of cancer research. This will allow study of the underlying causes of cancer disparities, including basic science mechanisms, and opportunity to design creative approaches to reduce them.

“Winship is ‘Where Science Becomes Hope,’” says Gillespie. “The Winship Center for Cancer Health Equity Research will focus on this important research related to reducing cancer disparities and promoting cancer health equity to find ways to ensure that the science is equitable and the hope is accessible to all people in Georgia, and beyond.”

Theresa Wicklin Gillespie, PhDWhen tornado damage in the summer of 2023 shut down a pharmaceutical plant in North Carolina, the pharmacy staff at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University quickly took notice. Like meteorologists tracking a storm, they began to calculate how the plant closure might affect the supply of drugs for Winship patients.

Fortunately, the plant closure was short lived. In late September, the facility reopened and resumed production of medications to meet patient needs and replenish hospital system inventories on a priority basis.

Unfortunately, though, drug shortages are commonplace in the United States today. At the end of June 2023, more than 300 drugs were in short supply, based on quarterly data from the University of Utah Drug Information Service.

Ryan Haumschild, PharmD

Ryan Haumschild, PharmD

Most experts point to the generic drug market as the primary cause. Because these low-cost drugs yield low profit margins, only a few companies make them. “If one of those companies closes because of manufacturing problems, it impacts the sustainable supply chain for that medication,” Haumschild explains.

In recent months, the United States has experienced a shortage of 15 cancer drugs caused by manufacturing and supply chain issues.

Three of these drugs—cisplatin, carboplatin and methotrexate—are generic chemotherapy drugs used safely for decades to treat patients with cancer.

Late last year, the manufacturing plant in India that makes cisplatin and methotrexate ceased production after failing to meet U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) quality control standards. Up until then, the company supplied 50% of these drugs in this country. Additionally, the cisplatin shortage led to increased demand for carboplatin as an alternative chemotherapy treatment.

The FDA—backed by President Biden’s commitment to end cancer through the Cancer Moonshot—has taken steps to help alleviate these shortages. Actions include working with cancer drug manufacturers to increase production capacity and bring companies that had stopped producing cisplatin and carboplatin back to the U.S. market.

The FDA also cleared the way to import more cisplatin from overseas and worked with five manufacturers to increase methotrexate supplies.

“Drug shortages are something we’ve always had to deal with,” says Ryan Haumschild, PharmD, director of pharmacy for Winship Cancer Institute and Emory Healthcare. “It’s become more of an issue in the past 10 years.”

The factors driving these shortages are varied: manufacturing issues, production delays, regulations that slow the expansion of production facilities overseas, increases in drug demand, discontinuation of a particular drug and the occasional natural disaster, like the tornado in North Carolina.

“So far, we haven’t had any issues with our supply of immunotherapy drugs,” says Jonathon Kaufman, MD, medical director and section chief of the Winship Cancer Institute Ambulatory Infusion Centers. “Carboplatin has been the most concerning, and we’ve asked our teams to use a non-carboplatin approach to treatment when they can.”

Kaufman adds that during summer 2023, there was an issue with fludarbine, a chemotherapy drug used in patients with hematologic malignancies. “Other cancer centers had experienced a shortage, which affected us very late,” Kaufman says. “We did have to initiate our shortage plan, but we’ve overcome that. We had to shift treatment using another drug for a very short time.”

By nature, the term “drug shortage” is concerning. “But ‘shortage’ doesn’t mean that a medication is unavailable,” says Kaufman. “If we did not implement changes in treatment when they are needed and

no new medication was available, then it’s possible that medication would not be available in the future. Fortunately, with our dedicated approach, we have not faced this situation.”

Drug inventories can vary among the nation’s comprehensive cancer centers at any given time. “When we’ve had a shortage of a medication, our cancer center partners have stepped in to help when their inventories were okay,” says Kaufman. “We’ve reciprocated when they have a need.”

While the shortage of immunotherapy drugs has been challenging for cancer centers in general, Winship has managed any shortages through a rigorous approach based on preparation, collaboration and transparency.

“Dr. Haumschild and our clinical and operational pharmacy managers, pharmacy technicians and buyers do a great job of monitoring drug supply data and staying ahead of things by making sure we have an adequate supply of medications and that we’re prepared for shortages,” says Kaufman. “We have the ability to withstand shortages up to four months. If we reach that point, we then consider other drug treatment options so that we stay prepared.”

Haumschild and the Emory Healthcare pharmacy leadership team are constantly looking ahead—anticipating shortages, staying up to speed with manufacturers, taking the pulse on drug volumes nationally and locally and participating in the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists and other organizations. Once a week, Haumschild and Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, Winship’s executive director, join other comprehensive cancer center

leaders on a conference call with FDA leaders to discuss drug shortage issues and strategies.

“We work very hard to stay ahead of drug shortages, including the current shortage of chemotherapy drugs,” says Haumschild. “At any point in time, some supplies become more stable while others may not. We have to keep physicians and everyone else up to date.”

When a potential drug shortage arises, Haumschild, Kaufman and others work closely with Winship’s disease teams (for lung, breast, lymphoma, myeloma and other types of cancer) to determine how best to conserve current drug supply and, if needed, manage changes in treatment from a medication on shortage to one with equivalent benefits for patients.

All disease teams follow best practice guidelines for drug shortages developed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Oncology Nursing Society. They also work closely with Winship ethicist Rebecca Pentz, PhD, to determine the best way to steward drug supply, now and in the future, to ensure ethical and equitable treatment for patients.

Open communication is key to managing any drug shortage issue. “We’re transparent with physicians and we’re transparent with patients,” says Kaufman. “We inform patients when a change in treatment is needed, and why, and assure them the change is appropriate and does not compromise their care.”

Each week, Haumschild takes part in another Emory Healthcare system pharmacy conference call to monitor the landscape of drug shortages as products on shortage change frequently due to manufacturer issues or demand.

“At Winship, we’ve really been lucky,” he says. “We have not had to withhold care from patients because of drug shortages. That’s because we’re so intentional about staying ahead of these shortages as much as possible every day.

“I like to think we are a duck that sits gently on top of water,” says Haumschild, “but we’re pedaling like crazy underneath so our patients have a seamless experience and the best possible outcomes they can.” w

FEATURE WINSHIP

reating a disease with a drug already FDA-approved to treat something else, known as drug repurposing, can offer new treatment options for patients with unmet medical needs. It can provide advantages over new drug development in that the existing drugs’ safety and pharmacokinetic properties (how drugs move throughout and interact with the body) are already known. Repurposing drug studies also tends to have a shorter clinical development timeline than new drugs.

ScD

ScD

Best of all, repurposed drugs also may represent a more effective and affordable way to treat cancer, according to Vikas P. Sukhatme, MD, ScD, Woodruff Professor and founding director of Emory University School of Medicine’s Morningside Center for Innovative and Affordable Medicine. Sukhatme also is the cofounder of GlobalCures, a nonprofit conducting clinical trials on promising cancer therapies that are not being pursued because they aren’t considered profitable. The Morningside Center is dedicated to investigating these so-called “financial orphans,” Sukhatme says. “Generic existing/approved non-cancer drugs form the largest class of financial orphans, as do some supplements and lifestyle changes.”

Once a potential new use is identified for a drug, it then undergoes preclinical and clinical testing to evaluate its efficacy and safety for the potential new indication. If the drug is found to be effective and safe, regulatory agencies can consider approving it for the new indication—offering patients a new treatment option.

“We need to subject the many ideas we have [for repurposing

various drugs] to proper clinical studies to validate or invalidate them,” says Sukhatme. “Academic health centers that house major cancer centers, such as Winship, can play a key part, especially assessing safety and feasibility and for developing biomarkers to stratify those most likely to respond.”

Sukhatme also points out the importance of engaging the community. “Our aspirational goal,” he says, “is to create a national network of caregivers in the community to do this.” Such a network would allow the researchers to collect real-world off-label treatment

data with outcomes that can be extracted into a registry to complement clinical trials (registry-based studies).

Physicians and researchers at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University are continually studying and developing new ways to treat various cancers with repurposed drugs. Here are a few examples.

The idea of treating cancer by unleashing the immune system dates back to the late 1800s and early 1900s, when William Coley injected bacteria into patients with cancer to instigate an immune response. “He had some success in multiple tumor types, but the work was largely ignored, hard to reproduce, quite toxic and not competitive with the advent of chemotherapy,” says Sukhatme. Some success was achieved years later in renal cancer and melanoma with high doses of certain immune modulators, but again it didn’t work with other tumors.

The era of immunotherapy began about a decade ago when certain solid tumor types responded to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. This innovative treatment uses a class of drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors. Much like other immunotherapies, the goal of checkpoint blockade immunotherapy is to strengthen the body’s immune system and enhance its ability to fight off harmful invaders.

“The major challenge now,” says Sukhatme, “is to improve the response rate and durability of response by discovering combinations of drugs.” In fact, he says there are data for several cancer types that respond even more effectively to immunotherapy with checkpoint blockade when it’s used with certain non-cancer drugs or supplements—including histamine 1 blockers, beta blockers, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, fenofibrates, vitamin B5, magnesium and some probiotics.

“Statin drugs appear to enhance the survival of patients with head and neck cancer, for reasons that we do not fully understand,” says Nicole Schmitt, MD, FACS, co-director for translational research in Winship’s Head and Neck Program and associate professor in the Department of Otolaryngology at Emory University School of

Medicine. Data from laboratory and animal studies suggest that statin drugs can “directly kill” cancer cells—potentially by ‘starving’ them of the cholesterol-related byproducts they need—and enhance immune cells’ ability to fight the cancer as well.

Statin drugs offer significant benefits for treating head and neck cancers. Large clinical studies show they improve survival. Animal studies, though not yet confirmed in human studies, suggest they improve responses to immune therapy. Human studies show they reduce severity and incidence of hearing loss in patients treated with chemoradiation. A phase 2 human study in Europe also has confirmed they reduced the severity of radiation fibrosis, a skin condition affecting people treated with radiation. “Statins may improve not only quantity but quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer,” Schmitt says.

Beta blockers are typically prescribed to treat high blood pressure or other cardiovascular-related issues such as angina or arrhythmia. Winship researchers have studied another potential use for propranolol—a beta blocker often prescribed for heart problems, anxiety or migraines: as a treatment for multiple myeloma, a cancer of the blood’s plasma cells. Studies show beta blockers like propranolol may increase multiple myeloma cells’ sensitivity to specific therapeutics.

“Beta blocker effects on cancer are likely complex, targeting the cancer directly and indirectly,” says Malathy Shanmugam, PhD, MS, a member of Winship’s Cell and Molecular Biology Research

Program and associate professor in the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology at Emory University School of Medicine. Her team investigates based upon the premise that cancer causes stress, which leads to inflammation within the bone marrow—where multiple myeloma cells reside—making the bone marrow microenvironment even more susceptible to cancer.

Specific beta blockers can shut down the signals that promote the inflammation and related tumor growth. Although studies led by Shanmugam in this area are promising, more research is needed to determine the significance of the findings, and the ideal uses for the best outcomes. Shanmugam notes that one published study shows that the beta blocker propranolol—typically used to treat high blood pressure—improves the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival of patients with multiple myeloma.

The question now is which patients benefit the most from beta blockers and which beta blocker is most effective. Although several clinical trials are under way in different disease contexts, the use of beta blockers in myeloma has not been extensively tested. “Future studies can allow for selective beta blockers to be repurposed for multiple myeloma therapy in specific contexts,” Shanmugam says, including an LLS grant-supported study she is leading through 2025, “Investigating anti-neoplastic effects of beta blockers in multiple myeloma.” She adds, “Any knowledge we gain about how beta blockers can prevent development and progression or improve sensitivity to existing therapy can help in repurposing these drugs for multiple myeloma therapy.”

Another potential breakthrough in repurposing drugs for cancer care involves the possible application of a drug used to prevent tics in patients with Tourette’s Syndrome. It may potentially provide some benefits to patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a cancer of the bone marrow that interferes with the normal production of red and white blood cells and platelets. The research on potentially repurposing these psychotropic drugs is in its early stages, according to Kevin Bunting, PhD, member of Winship’s Cell and Molecular Biology Research Program, Aflac Field Force Cancer Innovative Therapy Chair in the Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, and a professor in the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Hematology and Oncology, at Emory University School of Medicine.

Bunting says the work is limited to cell lines in the lab. Although it shows “proof of concept,” he says they need to optimize drug delivery to avoid side effects from the combination therapy. It will be necessary to formulate the drug in a particular way, or use nanoparticles, to deliver it to humans at a therapeutic dosage. But human patientlevel data are not yet available. “It’s early translational research,” Bunting says, “which is inherently hard to predict going forward.” He adds that he would like to return to this therapeutic work in the future.

Sukhatme says Winship is running half a dozen repurposed drug trials, and the number is expected to double this year. Research

continues to provide answers as to the best uses for repurposed drugs, even the best time of day to take them.

Sukhatme is optimistic about the future of repurposed drugs to prevent many types of cancers from recurring. “We expect all types of cancer to benefit [from repurposed drugs],” he says. “We have ideas for drugs to be given at the time of surgery for cancers that have not metastasized macroscopically, that could prevent or delay cancer recurrence. We have ideas for interventions that will make checkpoint blockade [immunotherapy] more efficacious. And we have ideas for treating metastatic disease with drugs that prevent a cancer cell from adapting to the harsh environment where it exists when it forms a tumor mass.”