Among domesticated animals, the dog, always our faithful companion, is probably the creature closest to humans. The Latin writer Columella long ago stressed the importance of dogs in everyday life:

For what human being more clearly or so vociferously gives warning of the presence of a wild beast or of a thief as does the dog by its barking?What servant is more attached to his master than is a dog? What companion more faithful? What guardian more incorruptible? What more wakeful night-watchman can be found? Lastly, what more steadfast avenger or defender (De Re Rustica [On Agriculture], VII.XII.1)?

An extensive ancient literary tradition treats the behavior, both negative and positive, of the dog. In the Iliad, Homer portrays dogs as semi-wild beasts that prey on the bodies of warriors killed at the battle of Troy, as guardians of the flocks, and as hunters. Aesop, in several fables, describes dogs in situations that allude to human folly and greed. Aristotle’s De Animalibus Historia and Xenophon’s Cynegeticus are dedicated not only to the classification of dog breeds (the lists include about 60), but also to their habits and qualities. The dog’s major functions, as stressed by Columella, were household and herd guard, hunting assistant, faithful personal companion, and favorite pet. In some myths, the dog was imagined as a companion of the gods, a god itself (a god transformed into a dog), or a fantastic beast.

Much information on human communications with dogs, both in real life and in myth, can be found in Greek, Roman, Near Eastern, and Egyptian art. Representations of the dog, said to be the second-most-depicted animal in Classical art (following the image of the horse), illustrate the various breeds known in antiquity.

Ancient works of art and literature have preserved many names of dogs, one of which has been chosen for this presentation: Argos, the hunting dog and faithful companion of Odysseus. The hero and his pet present an expressive example of a human relationship with a dog, whose image is suggestively recognized here in a series of Greek and Roman cameos (cat. nos. 1–7).

Introduction 5

I The Argos dog cameos 9 II Guard dogs 29 III Hunting dogs 65 IV Pet dogs 83 V Companions of the Gods 105 VI Monstrous dogs 141 VII Warrior dogs 165 VIII Dogs of the Near East and Egypt 173

Works cited 203

Selected bibliography 205

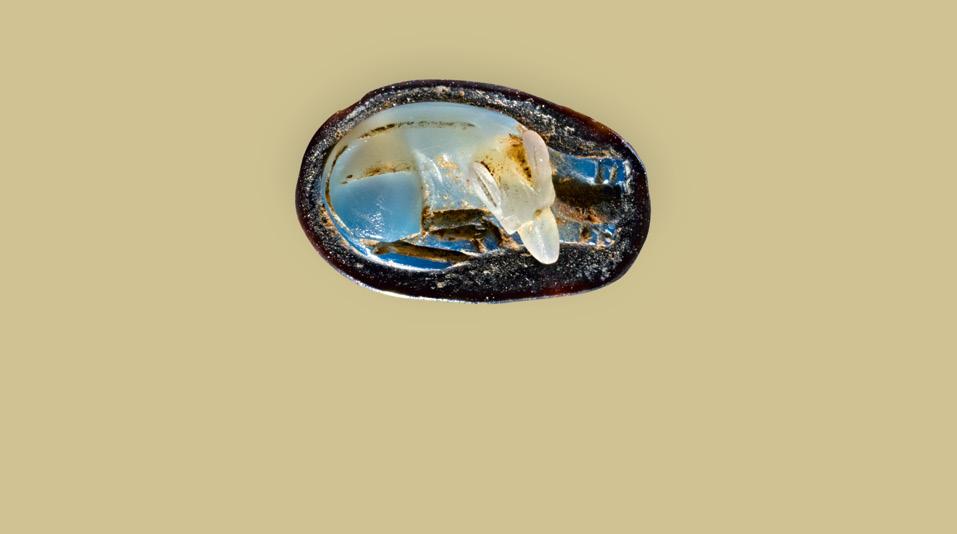

On a series of cameos and their glass paste replicas of the 2nd century B.C.–2nd century A.D., a dog is represented viewed from above: the animal reclines on its side, the head resting on, between, or even off the front paws stretched out before it. The choice of stone varies, from opaque and semi-translucent to translucent: there are agate (cat. nos. 2, 3), sard, sardonyx, onyx (cat. no. 6), nicolo, and even amethyst (cat. no. 4) cameos. Several less expensive glass casts imitating the stone cameos prove the popularity of the motif (cat. nos. 1, 5). All gems are usually small in size, and their carving is sometimes rather summary. Typically, the dog’s body is modeled in broad, rounded volumes, and the abundant long mane of hair is represented as a two-tiered mass; the tail curved around the hind legs is incised with several parallel lines. The best examples have finer modeling employing grooves and incisions to indicate the wavy hair on the head, around the neck, and on the body. The natural color layering of the gemstone was skillfully used to separate the body from the background or to represent the patches of different coloring of the animal’s hide. With the several existing replicas of the type, it seems, however, that the gem cutters avoided direct copying and enjoyed the variations that were based on observations from life. The dog represented on cameos could be a short-haired animal with pointed ears and muzzle, but the majority of images depict a hound with its characteristic large body, shaggy mane, and tufted tail—a Molossian hound.

The composition of the figure seen from above is quite unique in Greek and Roman art and does not occur in painting or sculpture in the round. One may conclude that it was designed by gem cutters, specifically for the inlay in a piece of jewelry that would be seen from above, such as a ring or a bracelet. The image of a dog on a personal piece of jewelry could have an apotropaic significance. Some similar representations are accompanied by a legend telling the wearer “γρηγορι” (Be wakeful!).

The same subject of a sleeping dog appears on ceramic Greek vases (see cat. no. 20) and Roman lamps. A very curious example is provided by an Italic bronze coin minted in Hatria (Picenum), a Latin colony in central Italy, in the first quarter of the 3rd century B.C.; the reverse of this unusually large and heavy cast coin represents in relief a dog lying asleep. It has been said that the dog, famous for loyalty to is owner, symbolizes the loyalty that the city showed to Rome.

An educated person in the Graeco-Roman world could evoke a literary work, for example, a poem by Homer, and associate the image of a sleeping dog with Argos, the dog of Odysseus. In a famous scene of Odysseus returning home to Ithaca disguised as a beggar, the warrior was immediately recognized by his faithful dog:

And a hound that lay there raised his head and pricked up his ears, Argos, the hound of Odysseus, of the steadfast heart

In days past the young men were wont to take the hound to hunt the wild goats, and deer, and hares; but now he lay neglected, his master gone (Homer, Odyssey, XVII 291–297).

Indeed, keeping the basic composition of the animal lying down, the dog could be represented as awake, raising the head, the ears pricked up and alert as if something or someone had just disturbed his sleep (cat. no. 6). Acknowledging the presence of his master, Argos does not betray his master with a bark and assumes the appropriate attitude:

Yet even now, when he marked Odysseus standing near, he wagged his tail and dropped both his ears, but nearer to his master he had no longer strength to move. Then Odysseus looked aside and wiped away a tear (XVII, 301–304).

A moment later, the devoted dog dies:

But as for Argos, the fate of black death seized him straightway when he had seen Odysseus in the twentieth year (XVII, 326–327).

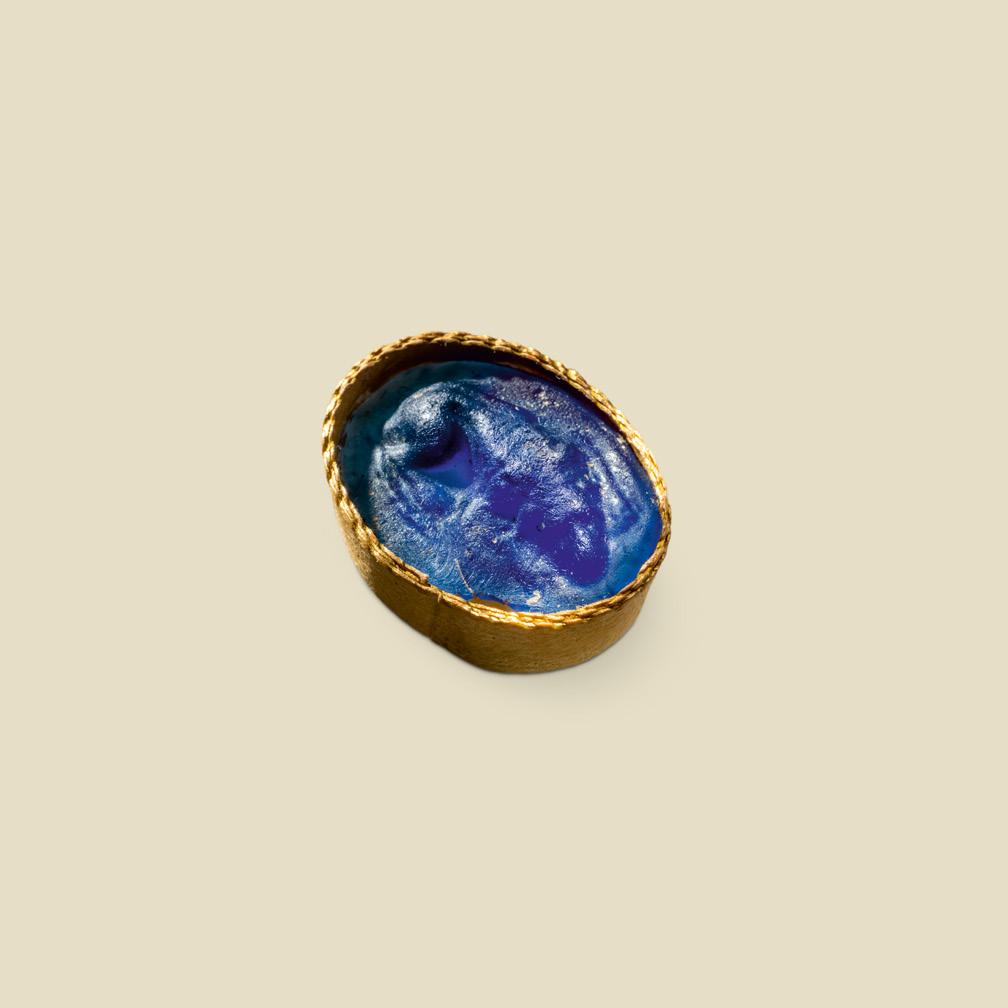

Greek, Late Hellenistic, 2nd–1st century B.C.

Gold bracelets, glass cameos

Bracelets D: 7.3 cm (2.8 in); cameos L: 1.8 cm (0.7 in)

Each bracelet is composed of a thick gold sheet with repoussé geometric ornaments consisting of two rows of zigzags and dots. The ends are terminated with spiral volutes made of gold wire. In the middle, an oval-shaped glass cameo in a gold setting is attached to the band with the aid of tiny wire loops. Each glass cameo has a dark background and features a resting dog modeled in opaque white and light brown colors. The representation of the dog captures the characteristic moment of an animal at rest with its head placed on the forelegs.

Ex- Swedish private collection, acquired in the 1970s; ex- European private collection, 2002.

Roman, 1st–2nd century A.D. Agate, gold

L: 2.1 cm (0.8 in), W: 1.9 cm (0.74 in)

Typical for the series of carved gems representing a sleeping dog seen from above, this cameo is one of the best thanks to the high quality of the modeling. Pronounced grooves define the fur on its neck and tail, and the polishing confirms the image of the well-fed and well-groomed favorite dog.

Ex- Felix Feuardent (1819-1907) collection, Paris, prior to 1907; thence by descent; ex- Swiss private collection.

Sigilli imperiali, capolavori della glittica antica, Minute Beauty, Masterpieces of Ancient Glyptic, Lugano, 2008, no. 60.

Roman, 2nd century A.D. Banded agate, gold L: 2.1 cm (0.8 in), W: 1.8 cm (0.7 in)

The cameo of banded agate has an attractive semi-translucent, shining gray background. The animal’s body, its soft skin skillfully modeled from the opaque white layer of the cameo, contains occasional light-brown inclusions that imitate the naturally occurring color patches of the dog’s skin.

Christie’s, London, 11 December 1996, lot 118.

Roman, 1st–2nd century A.D. Amethyst

L: 1.6 cm (0.6 in)

The image of a sleeping dog often appears in cameos; this one is a very rare example of the type executed in a beautiful translucent amethyst.

Private family collection, assembled in the 1970s–1980s.

Roman, 1st–2nd century A.D. Glass, paper frame L: 1.9 cm (0.74 in)

Less expensive glass cameos replicate the motif that appears on Roman Imperial gems. The glass versions were widespread, their popularity suggesting a possible apotropaic significance.

Ex- Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886–1965) collection, Rome, acquired in the late 19th–early 20th century; ex- private collection, Monaco, 1970s; thence by descent.

Roman, 1st–2nd century A.D.

Onyx

L: 1.3 cm (0.5 in)

On this onyx cameo, the Molossian hound remains lying down but awake, with raised head, pricked-up ears, very alert. The representation could be associated with Argos, the dog of Odysseus, recognizing him in a beggar approaching his home in Ithaca.

Frank Sternberg AG, Zurich, 26 November 1991, lot 901; ex- private collection.

Roman, 1st century A.D. Mother of pearl D: 6.0 cm (2.3 in)

Its large size and outstanding carving make this round cameo unique. Cut from a large piece of mother of pearl, it is decorated with a dog of the Molossian breed. The animal, seen in his right profile, is finely carved in high relief. The impression of the canine’s strength is emphasized by his large head and a number of sculpted details: the thick folds of skin on the forehead, especially around the eyebrows; the deeply inset eyes with their carved pupils; and the powerful, half-open fanged mouth. The dog raises his right front paw, displaying its strong musculature. The small holes pierced on the border of the cameo served to fix it in a frame of another material: the size and the shape of the piece suggest that it was the terminal of a fulcrum, the attachment decorating the slanting end of Hellenistic and Roman couches (klinai).

Provenance Ex- Artemis gallery, Munich, 2002.

The dogs who “keep painful watch about sheep in a fold, when they hear the wild beast” (Iliad, X, 185), the swift and angry dogs ready to follow the intruder, were repeatedly mentioned by Homer. Virgil advised readers to take good care of them:

Nor be thy dogs last cared for; but alike

Swift Spartan hounds and fierce Molossian feed

On fattening whey. Never, with these to watch, Dread nightly thief afold and ravening wolves (Georgics, III, 404–407).

Guarding herds, however, was not established as an independent theme in Greek Archaic and Classical visual art, but made its appearance in the so-called pastoral reliefs and paintings of the late Hellenistic period, which depict the countryside with shepherds, their stocks, and rural sanctuaries. In Roman art, such scenes were incorporated into larger mythological representations to mark a peaceful rural landscape: for example, on a sarcophagus panel with the representation of the story of Selene and Endymion, the shepherd seated on a rock is giving a treat to his dog.

Front-door floor mosaics as warning signs, discovered in some houses at Pompeii, portray the dog, a household guard, barking and confronting an unwanted visitor. One of them, at the entrance of the House of the Tragic Poet, with a large image of a dog, bears the inscription cave canem (Beware the Dog!). The dog has a collar, and it is chained. In Pompeii, archaeologists have found actual remains of a bronze-studded collar worn by an unfortunate watchdog who was left chained up during the disastrous eruption that buried the city and many of its inhabitants.

In a different capacity, as a tomb guardian, the dog became a meaningful image in funerary sculpture. The natural qualities of the animal, especially its ferocity and bravery, contributed to the choice of the dog as protector of the grave. A freestanding sculpture of a dog seated on its haunches in a frontal position, or sometimes dogs set in pairs, would be placed in the graveyard, similar to the most noble kind adopted for such monuments: larger in size, and thus even more impressive, the figure of the fearsome lion. On marble grave stelai of the late Archaic and Classical periods, the motif of the dog was also employed in the context of daily life: the dog was often depicted as a companion standing next to the figure of his master and looking up, directly into his eyes, still a faithful animal of the deceased. In such representations, the realistic and symbolic meanings were interconnected; in Greek thought, the dog had chthonic (related to the Underworld) associations, most probably because of its close connection to Hecate and Hermes.

Roman, 1st–2nd century

A.D. ChalcedonyL: 6.0 cm (2.3 in)

This completely preserved figure of a recumbent animal was carved from a single piece of chalcedony. Its semi-translucent bluish white surface is smoothly polished, demonstrating the great skill of the craftsman. Although the modeling is somewhat summary, the composition captures the dog’s resting pose: the dog lies flat with its pointed muzzle on outstretched forepaws. Although only several incised lines, some shallow and others deep, indicate the anatomy (eyes, nostrils, claws, ribs), the neck fur, and the collar, the representation is nevertheless realistic. No tail is represented; instead, a bored hole indicates that the piece was attached to an object as its handle. (There are some deposits inside the incision lines below the head and between the forepaws, and a few chips around the hole and on the bottom of the piece.) The design combines figurative representation and functional device; characteristic is the pointed muzzle of the dog which perfectly suits the narrow shape of the piece. The carved figure could have served as the handle of a knife or a spoon; another possibility might be that the piece was attached to a patera, a shallow libation bowl with a straight handle.

Ex- British private collection; ex- US private collection, New York, 2001.

Graeco-Persian, second half of the 5th century B.C. Chalcedony L: 2.9 cm (1.1 in), W: 2.2 cm (0.8 in), H: 1.2 cm (0.4 in)

Superb gem color and very fine engraving distinguish this large scaraboid with a convex back and a pierced suspension hole. Two seated dogs are represented symmetrically in a heraldic composition, looking at each other, evoking images on Mesopotamian seals from the late 3rd millennium B.C. The schematic composition of the figures is enriched by the naturalistic rendering: the bodies seen from the back in three-quarter view were modeled with critical anatomical knowledge. The physical traits leave no doubt that these are the Molossian hounds famous for their strength and ferocity. The combination of deep rounded carving with carefully engraved details typifies the virtuoso technique employed by the gem cutters of the Classical period. A close parallel for the composition of the seated dog (but one less fine in its modeling) is presented by the chalcedony scaraboid in the Hermitage Museum assigned by John Boardman to the Wyndham Cook Group.

Provenance Ex- UK private collection, 1971.

Greek, late 4th century B.C. Bronze D: 15.5 cm (6.1 in)

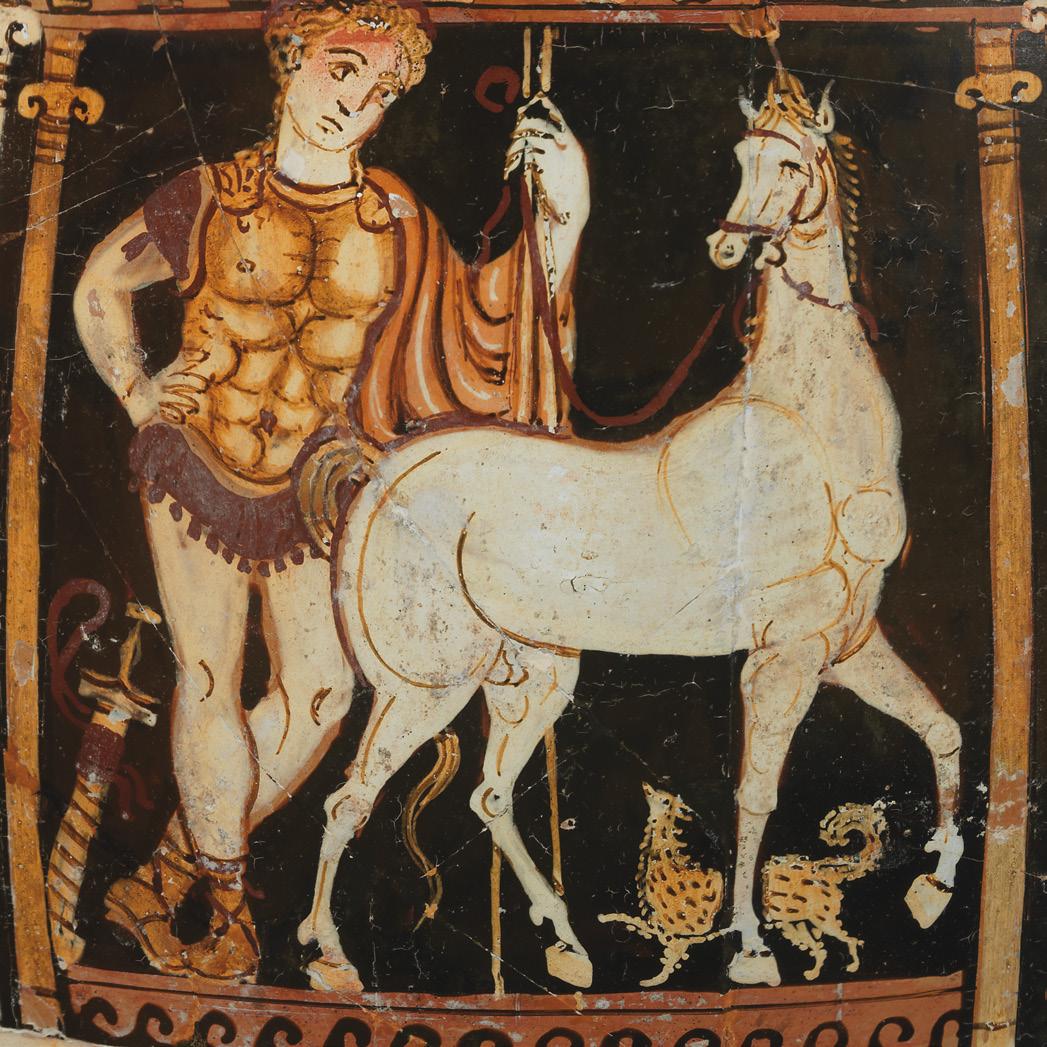

The piece consists of two sections, the mirror and its lid. The exterior section of the lid is magnificently decorated in high relief, while the interior presents an engraved scene with two satyrs. The ring that would enable one to open and hang the object is preserved. On the lid’s exterior, three human figures are represented.

On the left, a young man sits on a rock. Dressed in the "Oriental style," he wears boots and a short tunic (with long sleeves, folded over his chest, and held by a belt) under which are trousers. His Phrygian cap partially covers his long hair, which falls below his shoulders. Both tunic and trousers are richly decorated with incised flowers. He gazes to the right, at the young woman seated before him.

The young woman, too, sits on a rock, in a pose that is almost symmetrical to that of the young man. Her long curly hair touches her shoulders. She wears an ankle-length chiton and a himation (outer garment) that covers her legs and shoulders. In her right hand, she holds a part of the himation, as if to hide herself from the young man's gaze, a gesture typical of erotic scenes.

The scene represents two of the most famous characters of Greek mythology, Helen and Paris, accompanied by a small Eros with spread wings, a symbol of their union, and a dog. The dog's presence is undoubtedly to identify Paris as a shepherd, as illustrated on other artworks of the 5th and 4th centuries B.C.

Ex- German private collection, 1970s; ex- Swiss private collection, 2006.

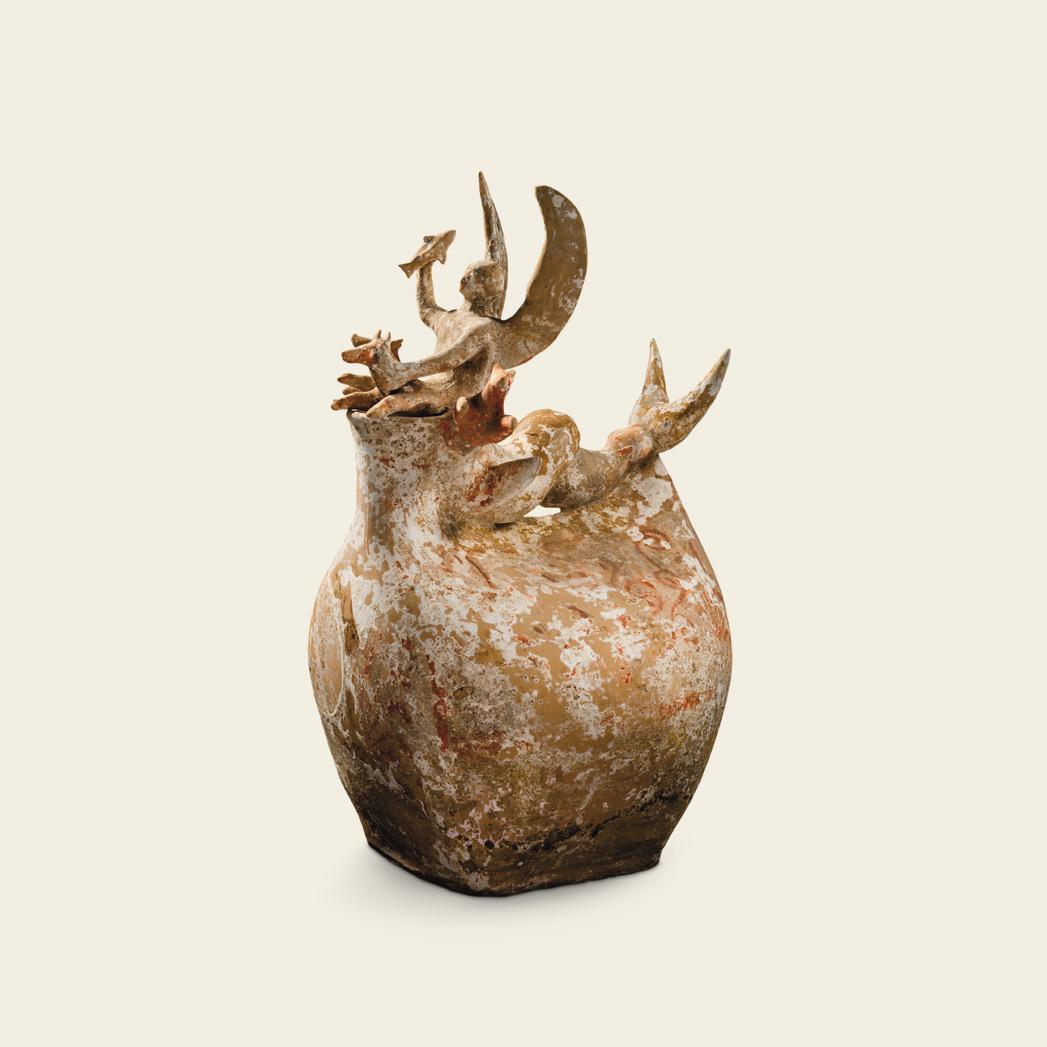

Greek, South Italian, Apulian, ca. 330 B.C. Terracotta, pigments H: 79.0 cm (31.1 in)

This krater (a large wine container) is a vessel of impressive scale and decoration. Its ample ovoid body sits on a sturdy circular foot; its tall, flaring neck is surmounted by volutes that cap the handles. Each handle is decorated with a gorgoneion (head of Medusa) in relief; the lower parts of the handles are duck-shaped heads that join the shoulders of the vase. Graceful figures of winged Erotes are painted on the handles below the volutes. Although the entire vessel is richly painted, mostly in the red-figure technique, some selected figures and various small details are painted or highlighted with white, yellow, or red pigments.

On Side A, a quadriga driven by the winged Nike, goddess of victory, is depicted on the neck. A heroized warrior, a youth clad in cuirass, short tunic, and mantle, with a large sword on the ground at left, stands inside a funerary shrine (a naiskos with Ionic capitals); he holds two spears and the reins of his horse. A little pet, his faithful Maltese dog, gazes up at him. The combination of the figures and their composition are very similar to contemporary Greek stone grave stelai. Four figures who participate in a ritual appear on the sides of the naiskos: two youths and two young women with offerings (a box, bunches of grapes, a mirror, a tambourine, a fan, a pair of soft boots). In the technique of painting, the employment of red, white, and yellow pigments produces remarkable pictorial effects: this is especially noticeable is the golden shine of the cuirass and in the skillful shading that imitates chest and body musculature in metallic relief.

On Side B, similar figures with offerings are represented on the sides of a monumental stele decorated with garlands and wreaths, with an elegant loutrophoros (vessel used to carry water at weddings and funerals) placed at its base. The remaining surface is abundantly ornamented with an egg-and-dart motif, waves, tongues, meander bands, and palmette scrolls. The manner of this vase painter has been compared to that of the Baltimore Painter, one of the most prolific and significant artists of later Apulian vase painting, whose workshop was probably situated near the city of Canosa.

Ex- private collection, Neuchâtel; ex- Payot private collection, Clarens, Switzerland.

Roman, 2nd century A.D. Chalcedony D: 3.9 cm (1.5 in)

This disc-shaped piece perforated on both its horizontal and vertical axes is a phalera, a decorative element with cross-like perforations to receive the suspension straps. It could have served as an amulet worn by a civilian or as a military ornament, a mark of honor (sets of phalerae could adorn a soldier’s cuirass); it could also have been worn with horse trappings. Gorgoneia and heads of Erotes are the most common subjects employed for phalerae; a sleeping dog is a very rare one. Modeled in high relief, the hound rests with his head between his outstretched forepaws. The curving line of his spine and long tail follows the curved edge of the stone. Several parallel and wavy incision lines mark the details of the fur on both sides of the spine.

Provenance Ex- private collection; Christie’s, New York, 13 December 2002, lot 613.

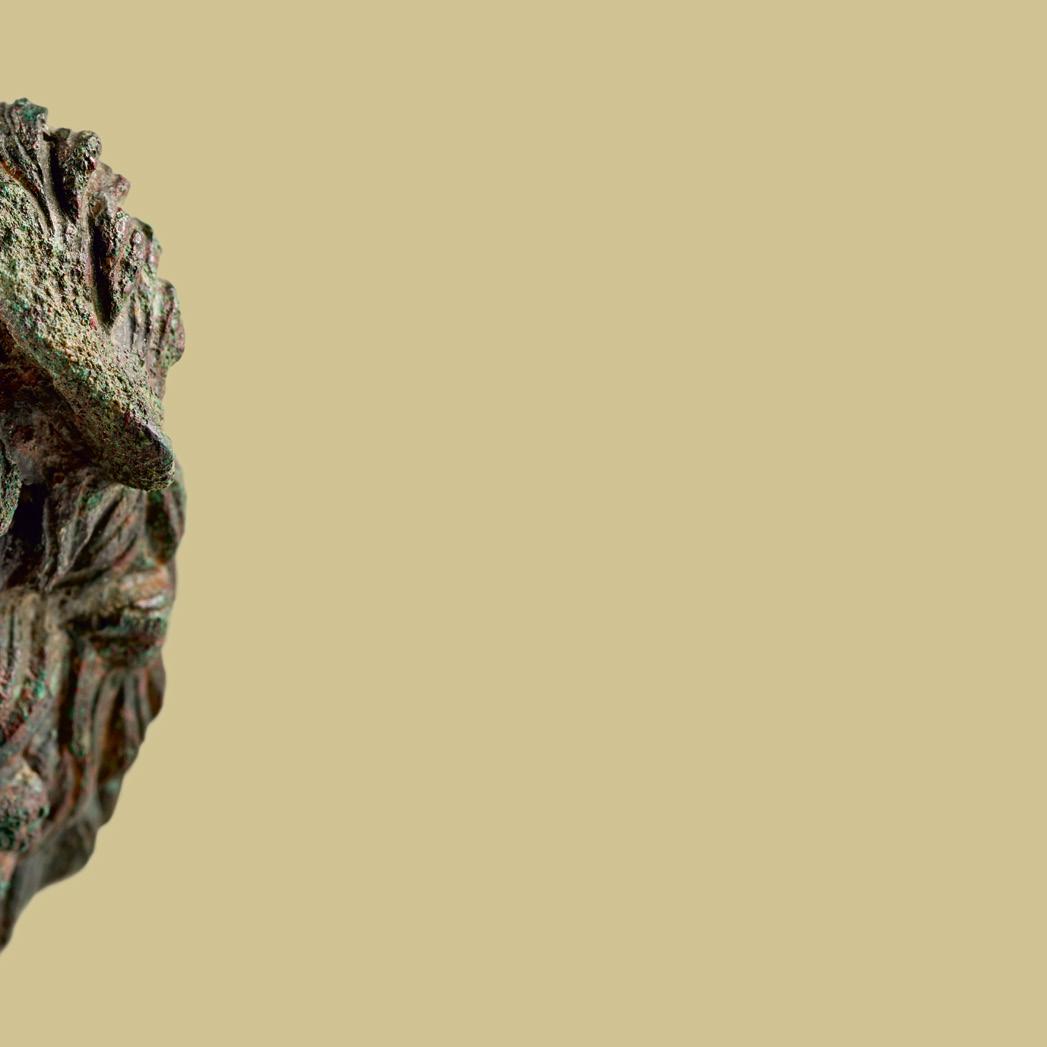

Graeco-Roman, 1st century A.D.

Bronze H: 12.0 cm (4.7 in)

This fulcrum of exceptional artistic quality was hollow cast in the form of a dog protome (the head and neck or upper torso of an animal or a person). The neck is long and curved, adorned with a shaggy coat of curly ringlets. The face is sensitive, its eyes wide and downcast, its ears downturned and topped with the same thick curly fur that covers the neck. The face is adorned with shorter fur, delicately rendered. The mouth is opened slightly, revealing the hound’s canine teeth. The skillful modeling of the face and neck illustrate the Graeco-Roman taste for naturalistic detail.

Bronze attachments in the form of animal heads (also mules and horses) decorated the slanting end of Hellenistic and Roman klinai (couches), on which diners and revelers ate and drank during dinner parties and symposia. Although the dog’s iconography does not directly link it to symposia, dogs are common enough on pieces like this one: this dog may be a watchdog or guardian of the feast, most probably a Molossian hound, which was prized in antiquity for such skills.

Ex- UK private collection; ex- US private collection, acquired in London, 16 February 1996.

“ Animal heads decorated fulcra (slanting supports) of Hellenistic and Roman klinai (couches) in the dinner setting or a symposium. This dog may be considered the guardian of the feast. ”

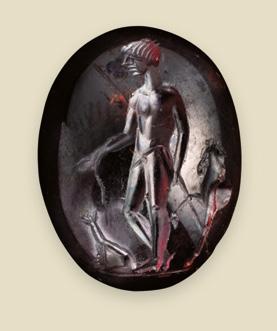

Roman, ca. 1st century B.C. Garnet

L: 2.15 cm (0.8 in)

The oval-shaped intaglio depicts a youthful nude hunter ready to depart for a hunt; he is holding a spear and probably a fillet. In front of him is a seated dog, while behind him are the foreparts of a horse.

Ex- Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886–1965) collection, Rome, acquired in the late 19th–early 20th century; Christie’s, New York, 6 December 2007, lot 319.

“

Giorgio Sangiorgi was a dedicated connoisseur and he acquired gems all over Europe throughout his lifetime in the early to middle 20th century. ”

Physical qualities (strength, swiftness of movement, and potential ability to fight) enable the dog to be a perfect hunting companion. Homer speaks of hunting dogs—“two sharp-fanged hounds, skilled in the hunt, press hard on a doe or a hare in a wooded place” (Iliad, X, 360–361)—who were able to follow not only a wild goat or boar, but also a lion. Argos, the dog of Odysseus, was a hunting hound praised by his master for his speed. Numerous breeds of dogs were known in antiquity to be employed as living tools in hunting; among them were Indian, Cretan, Molossian, Laconian, Italian (Umbrian and Tuscan), Gallic, and North African dogs. Based on their skills, different breeds were intended to hunt different animals; the dogs would have been trained since puppyhood to learn specific tactics and behaviors. Xenophon describes the main physical characteristics required of hunting dogs:

First, then, they should be big. Next, the head should be light, flat and muscular; the lower parts of the forehead sinewy; the eyes prominent, black and sparkling; the forehead broad, with a deep dividing line; the ears small and thin with little hair behind; the neck long, loose and round; the chest broad and fairly fleshy; the shoulder-blades slightly outstanding from the shoulders; the forelegs short, straight, round and firm; the elbows straight; the ribs not low down on the ground, but sloping in an oblique line; the loins fleshy, of medium length, and neither too loose nor too hard; the flanks of medium size; the hips round and fleshy at the back, not close at the top, and smooth on the inside; the under part of the belly itself slim; the tail long, straight and thin; the thighs hard; the shanks long, round and solid; the hind-legs much longer than the fore-legs and slightly bent; the feet round (Cynegeticus, 4.1).

Maintaining royal prestige required monarchs to keep the best hunting dogs. In the Ptolemaia, the famous festival procession of Ptolemy II (r. 284–246 B.C.) in Alexandria, onlookers admired, among the many exotic marchers, “two hunters carrying gilded hunting-spears. Dogs were also led along, numbering two thousand four hundred, some Indian, the others Hyrcanian or Molossian or of other breeds” (Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, V, 201B).

A number of ancient art works, including Greek vases (with the famous François Vase among them, which bears seven dogs’ names in the scene of the Calydonian Boar Hunt) and stone stelai, and especially Roman mosaics, preserve dogs’ names. Many are “speaking names,” such as Speed, Might, Force, Fly Like the Wind, Rusher, Victory, Tigris (tiger), Lupa (she-wolf), and Ladas (the name of the celebrated Spartan runner, which became synonymous with swiftness of foot). A list of forty-seven names appears in Xenophon’s Cynegeticus (7.5).

Roman, 2nd–3rd century A.D. Sardonyx

L: 1.7 cm (0.6 in)

This small cameo is an excellent example of the design and technique of gem cutting: the two figures in profile, a collared hound pursuing a large boar, are shown at the height of a very fast chase when the dog has just overtaken the larger animal. Using the differently colored natural layers, the gem cutter has modeled the dog’s figure in white over the boar’s profile in the brown layer beneath so that the shapes and details of each anatomy are clearly recognizable.

Frank Sternberg AG, Zurich, 26 November 1991, lot 898; ex- private collection.

Roman, 1st century A.D. Glass, paper frame L: 2.7 cm (1.0 in)

A rider hunting a boar became an especially popular subject among Roman gem cutters, probably reflecting the iconography of the Roman emperor’s hunt on marble reliefs (for example, the tondo relief with Hadrian’s hunt on the Arch of Constantine in Rome) or the legendary hunts of Alexander the Great. Peritas, a favorite dog of Alexander’s, who accompanied him on his campaigns, was famous for attacking and beating both a lion and an elephant.

It is also possible that the scene represents the mythological Hunt of the Calydonian Boar. This famous tale concerns the giant boar that the angry goddess Artemis sent to ravage the region of Calydon in Aetolia; the creature was killed by the hero Meleager. In the representation, two dogs—looking small compared to the beast—bravely attack the kneeling, already wounded boar, while the hunter on horseback raises one arm to slay it with his spear.

Ex- Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886–1965) collection, Rome, acquired in the late 19th–early 20th century; ex- private collection, Monaco, 1970s; thence by descent.

Roman, 3rd–4th century A.D. Bronze 30.5 cm (12.2 in) across

This sizable fragment comprises a circular offering-dish within a richly decorated hexagonal frame. The surface is entirely covered with animalistic representations cast in shallow relief. The hexagonal border of the outer form is decorated with ovae, while the surface between the border and the dish presents pairs of storks. Alternating pairs eat plants under a tree or from a large kantharos; each pair is arranged in a heraldic design. The inner sunken ring reserved by the narrow ornamental bands of beads follows the circular shape of the dish; its relief depicts dogs bringing down a wild bull and dogs chasing a hare, with a tree dividing the scenes.

Ex- European art market; Christie’s, South Kensington, 5 October 2000, lot 228.

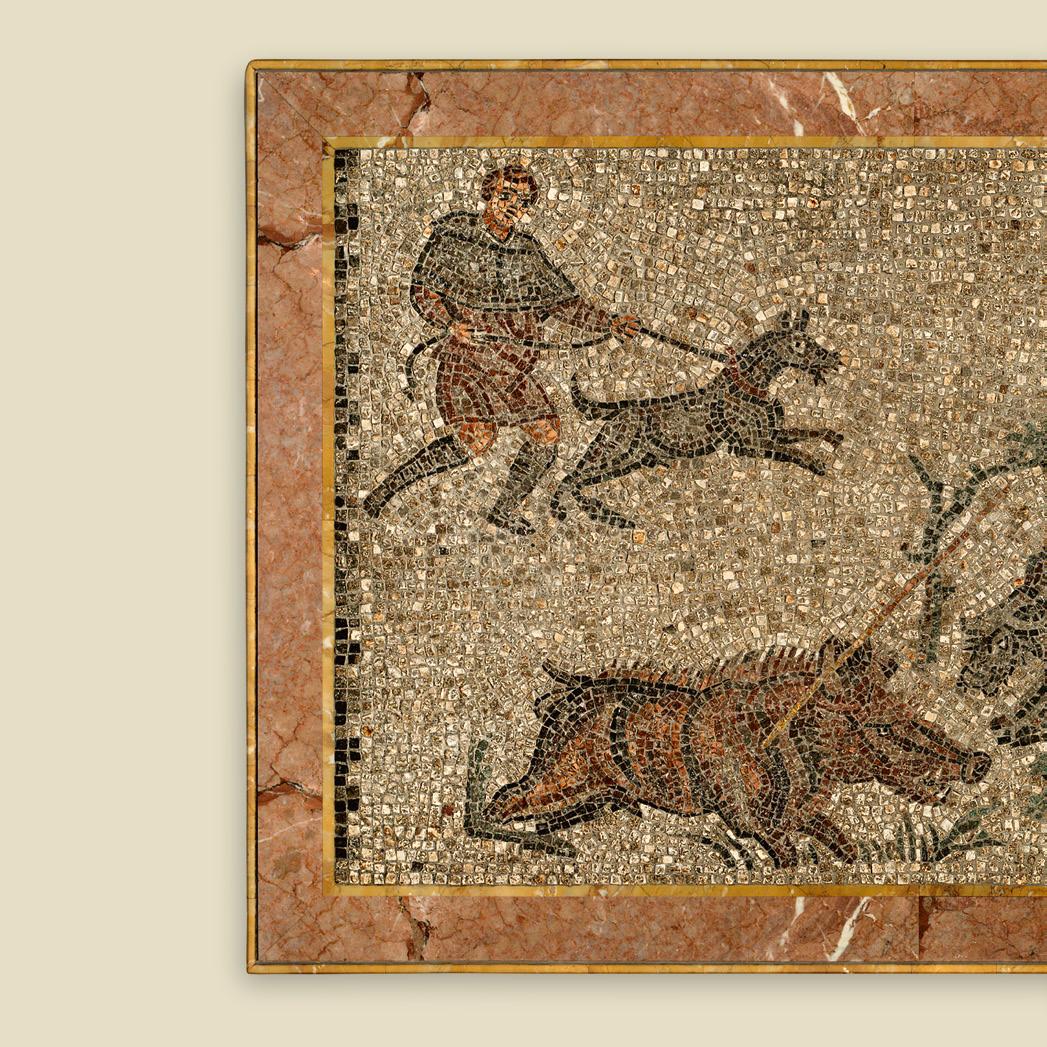

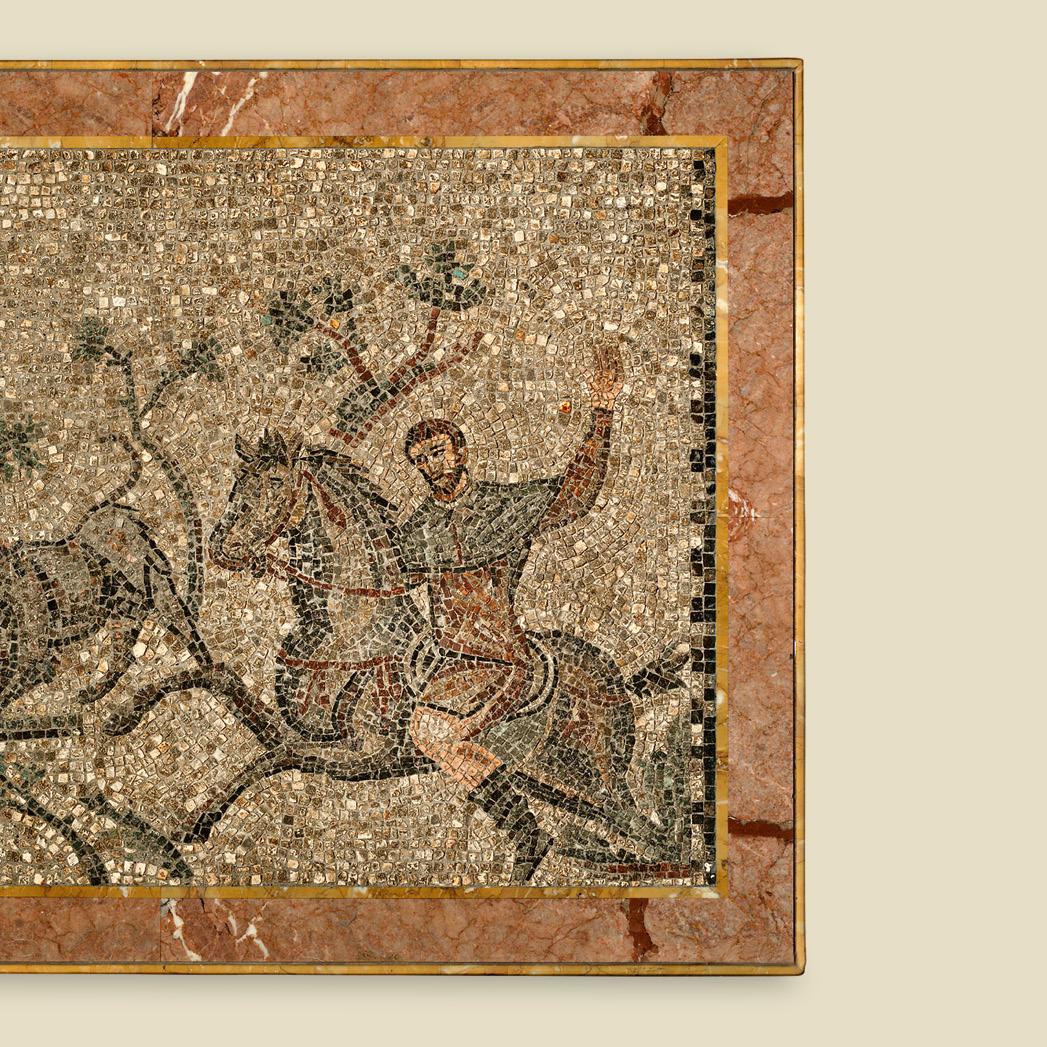

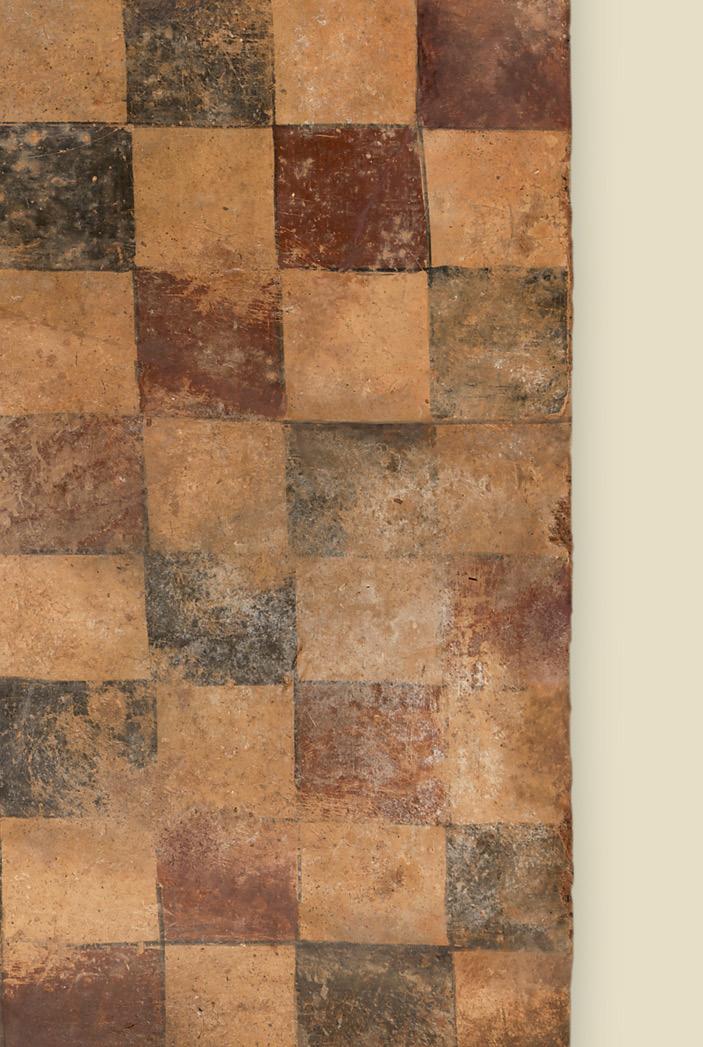

Roman, 4th–5th century A.D. Mosaic, stone tesserae W: 55.0 cm (21.6 in), L: 138.0 cm (54.3 in)

This is a fragment of a larger composition representing different episodes of the hunt. The wild boar is attacked by the equestrian hunter and wounded by his lance. The scene is dynamic, and every figure is shown in vigorous motion: the equestrian hunter’s arm is still raised even though he has just thrown the lance, while the dog is barking as he faces the wild beast. A companion following the leashed greyhound rushes to help the hunter. Both men are dressed in a long-sleeved tunic and a cape that folds over their shoulders; their lower legs are protected by wool socks and bands (fasciae crurales). The scene takes place in a landscape with a few trees and bushes that suggest more vegetation, such as a forest or a grove.

Hunting series were a very popular genre in the art of mosaic during the Roman Empire. Such scenes were especially admired and commissioned by owners of villas and estates and became a sort of self-representation and documentation of life in the countryside. The scenes reflecting the episodes of everyday life often bear the names of the hunters, their companions, and even their horses and dogs.

Ex- French private collection, Paris, ca. 1940.

Assyrian, 8th–7th century B.C. Pink marble

H: 2.8 cm (1.1 in)

A crowned king is dressed in an elaborate tunic and trousers. Armed with a bow, arrow, and quiver, he is represented as a mighty hunter confronting both a rearing lion and a large boar with bristling back. In a powerful action, he aims his bow at the lion; one arrow has reached the lion’s head, while another arrow has already hit the boar’s back. A dog, whose figure is depicted above the boar, attacks the animals from the side. A crescent moon appears in the sky.

Christie’s, New York, 30 May 1997, lot 9.

Many works of Greek and Roman art and literature convey the idea of pet dogs in antiquity. Human attitudes toward pets and their behavior were, in fact, the same as today’s. Nothing was more natural than to have a charming, faithful friend that gave great pleasure to its owner:

… the master’s pet puppy dog fawning on him day in and day out. The puppy ate his fill of food from the master’s table and was also given many treats by the household servants (Aesop, The Donkey and the Pet Dog).

And there was nothing unnatural for a human to grieve when a beloved companion passed away. Tombs for dogs and portraits of them existed in antiquity. The exaggerated affection toward his pet is presented by Trimalchio (Petronius, Satyricon), who directed that the sculpture of a little pet dog be placed at the feet of his own funerary statue, while next would be a statue of his wife leading her own dog. Publius, Martial’s friend, commissioned a portrait of his pet:

Issa is more playful than the sparrow of Catullus. Issa is more pure than the kiss of a dove. Issa is more loving than any maiden. Issa is dearer than Indian gems. The little dog Issa is the pet of Publius. If she complains, you will think she speaks. She feels both the sorrow and the gladness of her master. She lies reclined upon his neck, and sleeps, so that not a respiration is heard from her. And, however pressed, she has never sullied the coverlet with a single spot; but rouses her master with a gentle touch of her foot, and begs to be set down from the bed and relieved. Such modesty resides in this chaste little animal; she knows not the pleasures of love; nor do we find a mate worthy of so tender a damsel. That her last hour may not carry her off wholly, Publius has her limned in a picture, in which you will see an Issa so like, that not even herself is so like herself. In a word, place Issa and the picture side by side, and you will imagine either both real, or both painted (Martial, Epigrams, I, 109).

Memory of a touching relationship between a child and her faithful friend is preserved in a scene on the child’s tombstone: the girl teases her pet dog to jump to her hand, in which she holds a bird (symbol of the fragility of life). The dog is Maltese, a canis melitaeus, a famous breed of lapdogs in antiquity, which was often mentioned by Greek and Roman authors. Pliny the Elder finds the practical use of such a dog as a healing remedy: “Those puppies too that we call Melitaean relieve stomach-ache if laid frequently across the abdomen” (Natural History, 30.43). It has been observed that if these dogs were actually exported from Malta (according to the name of the breed), some sort of industry must have existed on the island to meet the demand.

Classical tradition also contains moralistic discussions about human relationships with dogs. As early as Homer, Odysseus wonders aloud about “table dogs” that were kept to serve as showpieces for their masters (Odyssey, XVII, 309–310). Many centuries later, Plutarch relates the story of Alcibiades, a famous 5th-century B.C. Athenian statesman and military leader, who, in order to provide a distraction from his own activities, docked the tail of his pet dog “of wonderful size and beauty,” for which he had paid 70 minas. When the citizens of Athens criticized him for his, he explained: “That’s just what I want. I want Athens to talk about this, that it may say nothing worse about me” (Life of Alcibiades, 9.1)

Greek, Hellenistic, late 4th–3rd century B.C. Terracotta, pigment D: 10.0 cm (3.9 in)

This ceramic mold-made vase is shaped in the form of a dozing dog that has curled up for warmth. The charming representation perfectly illustrates the natural and open relationship the ancients had with their animals and, more generally, with the natural world surrounding them. The body of the canine is finely modeled; lightly incised lines indicate fur on the head (with a white mark in the shape of a wave), back, and legs. The pointed snout, long ears, forehead and eyes, forelegs and tail are all rendered three dimensionally. The end of the tail protrudes from the circle drawn by the body, as if the dog were moving the tip of its tail while dozing and reopening its eyes for a moment.

Ex- Swiss private collection, assembled in the 1970s.

Greek, Late Archaic, ca. late 6th–early 5th century B.C. Carnelian

L: 1.85 cm (0.7 in), W: 1.5 cm (0.5 in)

The fragmentary intaglio represents a nude youth holding a lyre (barbiton); he is bending over a dog, offering food or teasing it with a treat. The depicted scene could also be a lesson to train the dog to execute some kind of a trick while accompanying it with music, to entertain guests at a banquet. The pose of the dog, with the advanced and raised foreleg, the upturned tail, and the head turned backward and up, is full of life and shows the animal’s complete engagement in the action.

Private family collection, acquired in the 1990s.

Roman, 1st century A.D. Stone and glass paste tesserae, marble frame H: 47.0 cm (18.5 in), W: 43.0 cm (17.0 in)

This extremely rare and beautiful mosaic depicts both an animalistic scene and a still-life. Executed with technical expertise, the artisan utilized very tiny, vibrantly colored tesserae made of stone and glass paste. Some of the mosaic tesserae were placed to create an outline that would separate the picture’s subject from the background (this elaborate technique was called opus vermiculatum). Other tesserae were combined with masterly skill to produce light and shade on the forms. Depicted is a moment of discovery in which a magnificent white Maltese dog dangerously faces another household pet, a partridge. The canine rests on a pillow atop the folding stool, whereas the bird is opposite, standing on a cista (lidded cylindrical box) covered with woven ornaments. The objects that were inside it are now displayed at the front (bottom) of the composition, as if ready to be used: the double-sided, beige-colored ivory comb and a multicolored glass vessel, an alabastron, the former no doubt to comb the long hair of the favorite pet and the latter perhaps to apply a perfumed oil to it.

The original black marble frame and ancient mortar are also preserved; these form the emblema, a figurative design that resembles a real painting and would have been inserted into a larger floor-mosaic composition, surrounded by floral or geometric patterns. Alternatively, this image could have been a portrait of a favorite pet set on the wall in a cubiculum, the master’s bedroom.

The Gilbert collection, Cambridge, Massachusetts, acquired in Geneva, 4 December 2000.

Roman, 1st–2nd century A.D.

Carnelian L: 1.2 cm (0.4 in)

The intaglio represents a dog, apparently standing in front of its (implied) master in a palestra and holding his sports attributes, a globular aryballos (container for oil that athletes applied to their skin) and a metallic strigil (an implement used by athletes to scrape oil and sweat from their bodies after exercising). A dog with his master inside the palestra was a frequent motif in Attic red-figure vase painting of the Classical period. However, the iconography of the dog holding the attributes in its mouth is quite rare. The Latin letters “DI” above the dog could refer either to the owner’s name or to the two letters of the dog’s epithet “divinus.”

Ex- Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886–1965) collection, Rome, acquired in the late 19th–early 20th century; ex- private collection, Monaco, 1970s; thence by descent.

Roman, 2nd century A.D. Bone

L: 6.0 cm (2.3 in), H: 2.3 cm (0.9 in)

A pug-type dog with a plump body and chubby legs emerges from a foliate capital to form a folding knife handle. The short-legged canine, wearing a collar, stands on an extended plinth. Depicted in a lively pose with his head turned toward the viewer, the pet, clearly a well-fed home companion, appears to be engaged in play with his master.

Ex- Leo Mildenberg (1913–2001) collection, Zurich, Switzerland, 1960s–1980s; Christie’s, London, 26 October 2004, lot 204.

KOZLOFF A. P., et al., More Animals in Ancient Art from the Leo Mildenberg Collection, Mainz am Rhein, 1986, p. 54, no. II, 161.

Roman, ca. 3rd century A.D. Bronze H: 13.5 cm (5.3 in), L of chain: 86.0 cm (33.8 in)

The cast bronze figure is hollow and served as an ampulla, a portable container for perfumed oil or unguent: a suspension loop on each side of the dog’s body is decorated with vine-leaf attachments to which a long and massive bronze chain, looking like a fancy dog’s leash, was attached. The dog’s open mouth functioned as a spout, and there is a fill hole with a hinged lid on the animal’s back. The dog (male, its sex is indicated), probably not very young, with heavy paws, is represented seated with his head turned to his left. His coat is stippled except for shaggy tufts of hair shaped around his neck and back. The large rimmed eyes have incised pupils and irises. The small head, corpulent neck, and bulky body with a short tail suggest that this house-dog was pampered and overfed. Ampullae in the shape of a bear were very popular in the Roman Imperial period; those in the form of a dog were much rarer.

Christie’s, New York, 7 December 1995, lot 83.

“

This portable container for perfumed oil or unguent has suspension loops decorated with vine-leaves to which a long and massive bronze chain, looking like a fancy dog’s leash, was attached. ”

Several Greek myths provide a variety of local stories connecting dogs with the gods. In Sicily, according to Aelian (Claudius Aelianus, De Natura Animalium, XI, 20), hounds were sacred to Adranos, the fire god who lived below Mount Etna. At least a thousand of them guarded his shrine and grove, and accompanied good-hearted visitors.

The gods possessed the magical power of transformation, sometimes choosing to appear in the guise of a dog. Taking the form of a hound, the river god Krisimos fell in love with the nymph Egesta (also Segesta); his image, along with the head of the nymph, appears on a series of coins minted by the city of Segesta in Sicily (cat. nos. 26–29). A different story concerns the Trojan queen Hecuba, who, having lost her children during the sack of Troy, threw herself into the sea; the goddess Hecate saved her and transformed her into a dog (Hyginus, Fabulae, 243). Hecate, goddess of witchcraft, magic, the night and moon, was usually represented holding torches. The howling of a dog, which was considered her sacred animal, announced her approach. Hecate assisted Demeter when the latter was searching for her daughter Persephone, abducted by Hades and taken to the Underworld to be his consort. Hecate was also seen as a benevolent goddess who gave wealth and blessings to mortals. In many works of art, Hecate appears with a dog at her side.

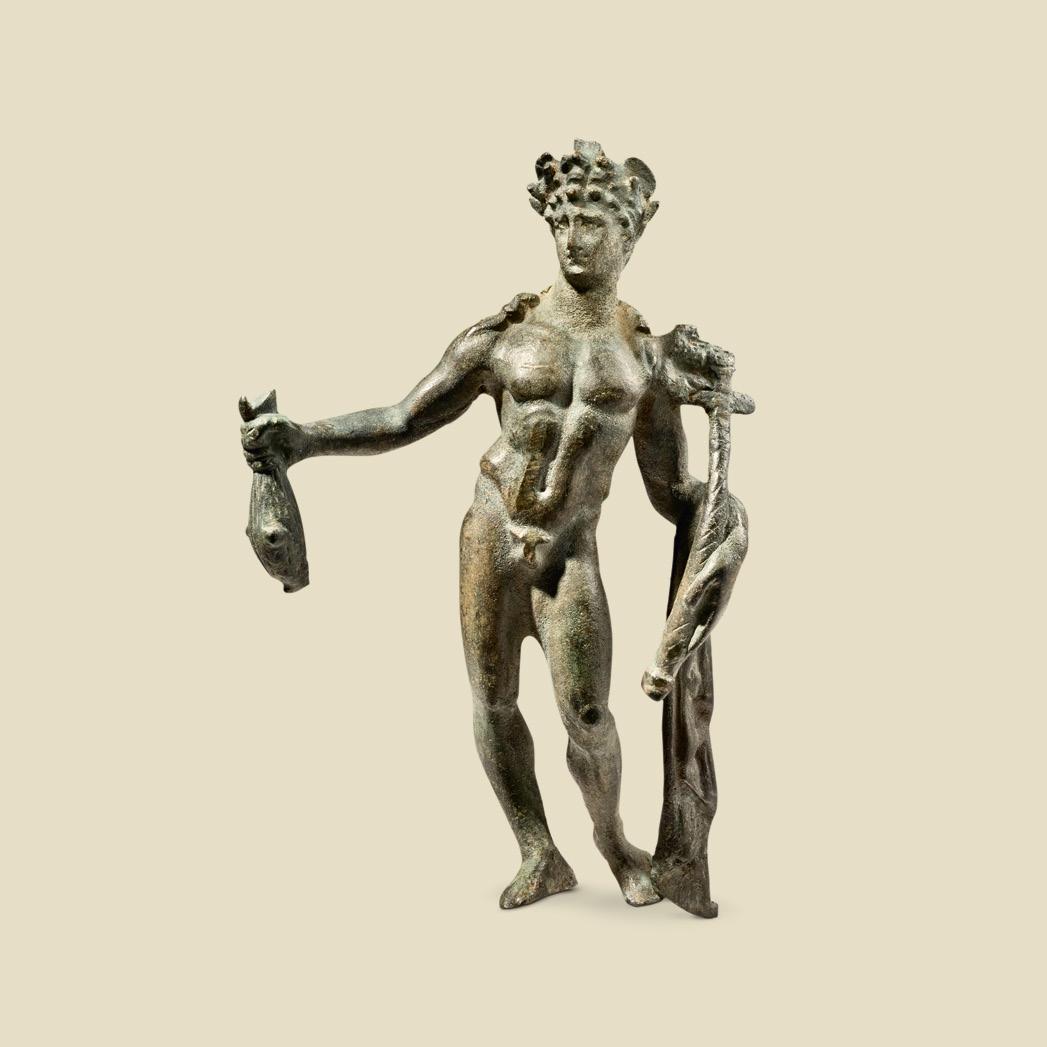

The messenger god Hermes/Mercury (see cat. no. 34) was also the patron of many areas of human and domestic animal life. As the patron deity of animal husbandry, he oversaw the guard dogs who watched over the herds and protected homes and sanctuaries. Zeus himself commanded “that glorious Hermes should be lord over dogs and all flocks that the wide earth nourishes” (Homeric Hymn 4 to Hermes, 569–571). Zeus also decreed that Hermes should be herald and messenger of the gods in the Underworld; he became the god who led and guided the souls of the dead to Hades. Another patron of the flocks, the rustic god Pan, was also closely associated with hunting; successful hunters often dedicated collars and leashes of their “keen-scented hounds” at his shrine (Anthologia Graeca, 6, 34–35).

Just as dogs functioned as hunting assistants to humans, a dog always accompanied the powerful hunting goddess Artemis/ Diana. Xenophon even credited her with their invention: “Game and hounds are the invention of gods, of Apollo and Artemis” (Cynegeticus, 1.1). As the birth goddess, Artemis was also the patron of dogs: “To little Calathina, in labour with her puppies, Leto’s daughter gave an easy delivery. Artemis hears not only the prayers of women, but knows how to save also the dogs, her companions in the chase” (Anthologia Graeca, 9, 303). Thus, Artemis was widely worshipped as patron of the family and the younger generation, her role similar to that of Juno, wife of Jupiter. Pliny the Elder recorded and praised the famous bronze statue of a dog by Lysippus in the shrine of the mother of the gods:

[O]ur own generation saw on the Capitol in the shrine of Juno, a bronze figure of a hound licking its wound, the miraculous excellence and absolute truth to life of which is shown not only by the fact of its dedication in that place but also by the method taken for insuring it; for as no sum of money seemed to equal its value, the government enacted that its custodians should be answerable for its safety with their lives (Natural History, 34.17).

Based on this record, it seems clear that sculptural images of dogs were considered appropriate dedications to certain gods, such as Hecate, Hermes, Pan, and Artemis. Both male and female healing deities were depicted with dogs who themselves were thought to possess healing qualities; and votive offerings in the form of canine representations have been found in their sanctuaries. In one of the stories about the birth of the healing god Asclepius (see cat. no. 35), the newborn boy was left by his mother on a mountain. Guarded by the watchdog of the herd, he survived on milk from one of the goats pastured there.

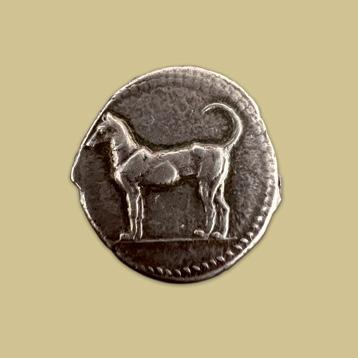

Sicilian, ca. 475–455 B.C. Silver 8.41 g

Obverse: a hound (Krisimos), its head lowered and tail raised, stands facing to the right. Reverse: the head of the nymph Segesta faces to the right; her hair is turned up on the back of her neck and held in place by a broad diadem.

Dr. Busso Peus Nachf., auction 349, Frankfurt, 1996, lot 50.

Sicilian, ca. 460 B.C. Silver 8.75 g

Obverse: a hound (Krisimos) with its tail raised stands facing to the left.

Reverse: the head of the nymph Segesta faces to the right; her hair is turned up on the back of her neck and held in place by broad diadem.

Gerhard Hirsch Nachfolger, Auction XIX, Munich, 11 November 1907; ex- Clarence Sweet Bement (1843-1923) collection; Lucien Naville, Auction VI, Lucerne, 28 January 1924, lot 428; ex- SpencerChurchill (1876 -1964) collection; Ars Classica, auction XIV, Lucerne, 2 July 1929, lot 104; The Numismatic Auction Ltd, auction 3, New York, 1 December 1985, lot 29.

Sicilian, ca. 415-405 B.C. Silver 8.75 g

Obverse: a hound (Krisimos) with its tailed raised stands facing to the right. Reverse: the head of the nymph Segesta faces to the right with an ivy leaf in the field.

Provenance

Ex- Münzen & Medaillen, auction 43, Basel, 1970, lot 38; Bank Leu, auction 71, Zurich, 1997, lot 57.

Sicilian, ca. 412–400 B.C. Silver 8.27 g

Obverse: a hound, facing to the right, stands on a stag’s head and seizes it by the nose; in the upper field is the head of the river god Krisimos.

Reverse: the head of the nymph Segesta faces to the right; her hair is up and she wears a headband (sphendone); on the left of the field is an ivy leaf.

Ex- Walter Niggeler collection; Bank Leu - Münzen & Medaillen, Auction Niggeler I, Switzerland, 1965, lot 134; Bank Leu, auction 25, Zurich, 1980, lot 61; ex- Hagen Tronnier collection; Fritz Rudolf Künker Münzhandlung, auction 94, Germany, 2004; ex- Jameson collection.

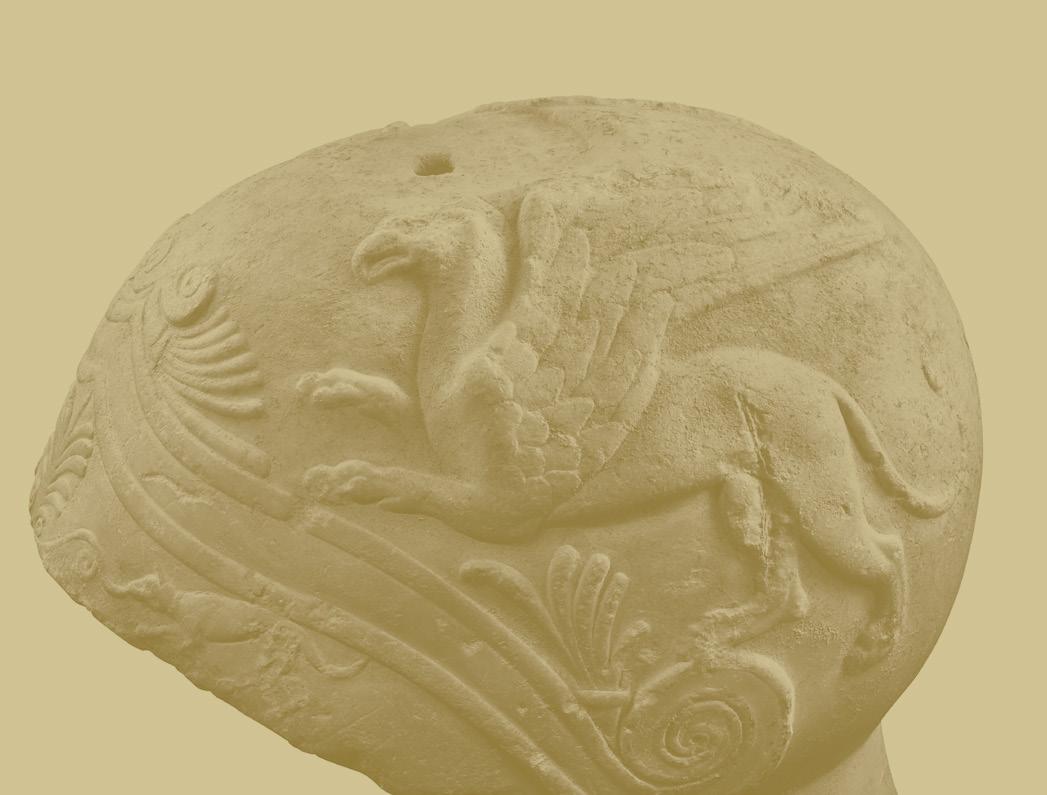

South Italian, Apulian, ca. 330–310 B.C. Terracotta D: 71.0 cm (27.9 in)

The figural decoration is limited to the inner part of the vessel. A continuous garland of leaves, overpainted in white and yellow, surrounds a frieze of waves, providing a border for the main subject depicted in the tondo: Nike, the Greek goddess of victory, has launched her biga (chariot) at full speed toward the left. The speed of the race is emphasized by the spread wings of the goddess and the raised forelegs of the horses. In the field, a white dog precedes the horses while leaves, flowers, and pebbles characterize the natural environment in which the scene unfolds. The goddess, painted in white with gold highlights, is depicted in three-quarter view. Her wings qualify her as a supernatural, or even mythological, being. Stylistically, this patera can be attributed to the work of late redfigure Apulian painters, including the so-called White Sakkos Group and the Kantharos Group, who often painted scenes similar to those depicted here. This patera, which is among the largest examples currently preserved, would probably have been used for ritual observances.

Ex- European private collection, acquired in Munich, 1992.

Attributed to the Painter of Oxford 1920 Greek, Attic, ca. 450 B.C.

Terracotta

H: 15.80 cm (6.2 in), D: 10.10 cm (3.9 in)

A red-figure lekythos of extremely fine quality is decorated with Artemis in her role as hunter. The goddess is moving rapidly to the right, bowstring drawn. She wears a long, finely pleated chiton with an overfold (apoptygma) that is girdled at her waist. A panther’s skin is draped around her shoulders. Her hair is dressed under a cap (saccos), with an errant lock just in front of her ear. In the field is a quiver, capped at both ends.

Hesperia Arts Auction, New York, 27 November 1990, lot 119; The Gilbert Collection, Cambridge, Massachusetts, acquired in London, 17 February 1995.

Exhibited and Published

“Images of Women in the Classical World,” Smith College Museum of Art, 9 April 2003–23 June 2003, p. 50, no. 11.

“

As the birth goddess, Artemis was also the patron of dogs: “To little Calathina, in labour with her puppies, Leto’s daughter gave an easy delivery. Artemis hears not only the prayers of women, but knows how to save also the dogs, her companions in the chase” (Anthologia Graeca, 9, 303). ”

Roman, late 1st century A.D. Marble

H: 74.90 cm (29.4 in)

Although the arms and legs are not preserved, the statue presents an assured and intriguing image, heightened by precise workmanship on fine marble. The individual features of the young girl’s face suggest a portrait of the Roman period, while her dress, attribute, and pose recall the goddess Diana. On the back of the figure is a cylindrical quiver attached with a strap; its diagonal cross-strap is seen on the front; this piece would be a typical attribute of the goddess of hunting, Artemis/Diana. She wears a short, sleeveless chiton tucked up to her knees to make running easier; the long overfold, apoptygma, is girdled high under her breasts and knotted. A hunting dog might have been represented at her side.

The affiliation of an individual with a deity had an important meaning in Roman religious culture: a specific god or goddess could be considered his/her personal or family helper and protector. Diana, the virgin goddess, symbolizes chastity, so her image would be particularly appropriate for a votive or commemorative statue of a young girl.

Ex- Swiss private collection, Neuchâtel, acquired in the 1960s.

Graeco-Roman, 1st century B.C.–1st century A.D. Marble

H: 27.0 cm (10.6 in), W: 27.5 cm (10.8 in), L: 32.0 cm (12.5 in)

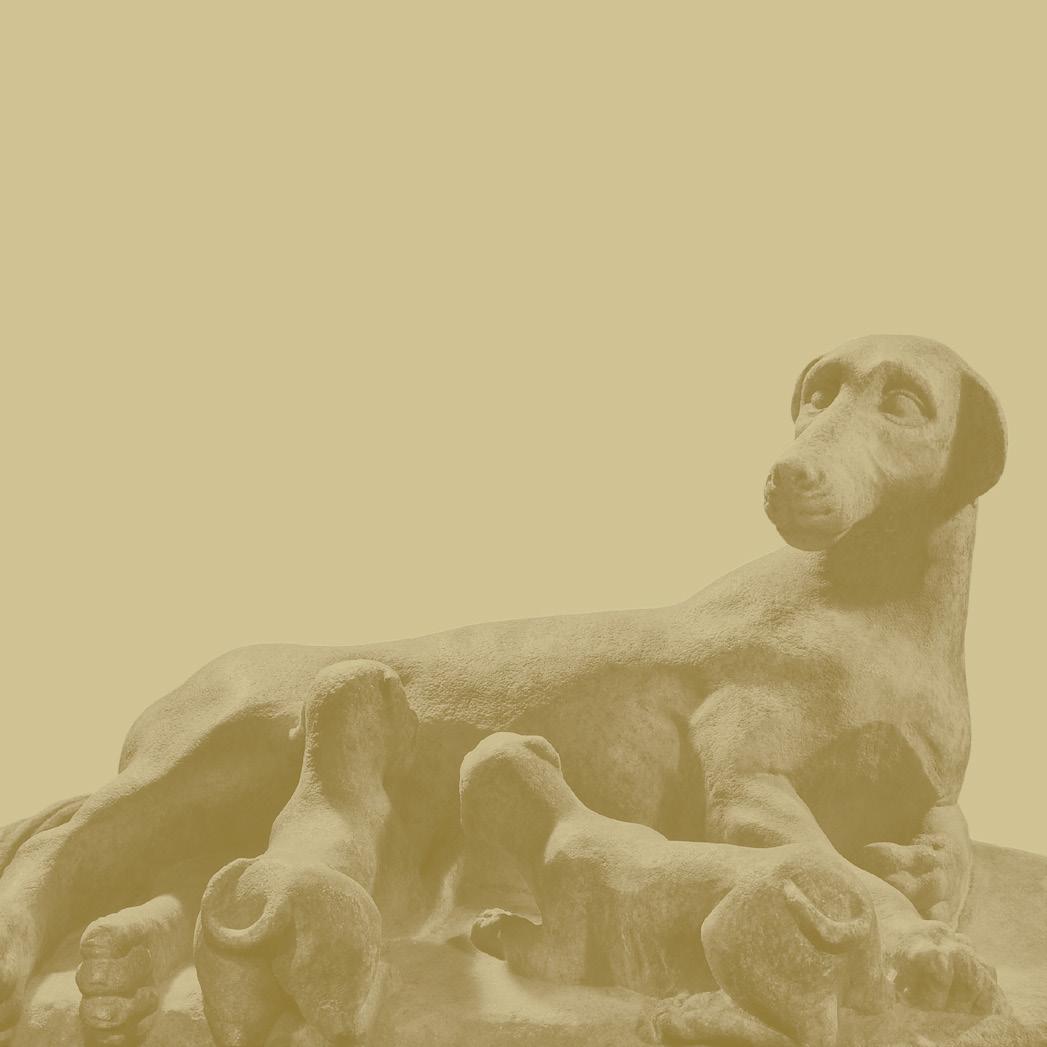

Among all existing representations of dogs in Classical art, this piece is one of the most complete and compelling story-telling compositions. The group is remarkable for the observation of every part of the action and the realistic representation of the scene. A bitch, lying prone on the ground and stretching her feet, has just raised and turned her head toward two puppies to see if they are doing well. The newborns, with eyes still shut, are insecure on their feeble feet; they are nursing at the mother’s nipples, and their curling tails expose their enthusiastic involvement in the nourishing process. The mother is exhausted from giving birth and is still frail, as seen from the exposed dorsal bones and ribs, her tired eyes recessed beneath prominent brows.

The peaceful mood and small size of the present group would have made it a desirable piece for the decoration of a garden or a fountain setting in a house or villa. Sculptural images of dogs were considered appropriate dedications to the gods that were patrons of the family and the younger generation (Juno, Diana).

Provenance Ex- Swiss private collection, 1967–1968.

“

Sculptural images of dogs were considered appropriate dedications to the gods that were patrons of the family and the younger generation (Juno, Diana). ”

Roman, 2nd century A.D. Bronze H: 14.2 cm (5.5 in)

The youthful god of commerce, Hermes in Greek mythology and Mercury in Roman, is represented with several attributes indicating his multiple duties. As one of the supreme gods, he attends their reunions and feasts; thus, his head is adorned with a large wreath fastened at the back with long ribbons the ends of which lie over his shoulders. As messenger of the gods, he usually wears winged shoes and a winged cap, but these are omitted from this statuette; however, small wings are visible on both sides of his head above the wreath. Leaning against his shoulder and held in his left hand is the herald’s staff, or caduceus, with two entwined snakes at the top. The staff possessed magical powers, one of which was to bring a dream sometimes associated with sudden death. Mercury guided the souls of the dead to the Underworld. In this capacity, he was also associated with the Egyptian god Thoth, the judge of the dead, who was depicted with the head of an ibis; here, an ibis plume appears at the center of Mercury’s wreath. Because of his activities as messenger and guide, Mercury was a traveler never at rest: the traveler’s long cloak, a chlamys, is seen hanging over his left forearm. As the protector of financial gain and commerce, Mercury here holds a purse full of coins in a bag made of skin that preserves the shape of a small animal.

Ex- European private collection, acquired in 2000.

Roman, 1st century A.D. Bronze H: 10.1 cm (3.9 in)

The bronze figurine represents the Roman god of healing and medicine, Asclepius. A mature man with a long beard is standing in a relaxed pose, with his weight on his right leg and his left knee bent; the head is slightly turned to his right and lowered. He is dressed in a long himation, which leaves his right shoulder and most of the torso bare; and he wears sturdy sandals (trochades). The arrangement of the folds on the front of his garment is marked by a large diagonal overfold; the folds fan across the back and cascade down from his left arm. He holds a scroll in his left hand. There was another attribute in his right hand, probably a serpent-entwined staff, the most characteristic attribute of the god. His hair is bound in a fillet; the face with its finely modeled features is framed by abundant curly locks. This small sculpture could have been a votive offering or a figure kept among other images of the gods, the family protectors, in a home shrine (lararium).

Provenance UK Art market, London; Christie’s, New York, 7 December 2000, lot 616; ex- New York private collection.

Graeco-Roman, 1st century B.C.–1st century A.D. Bronze; silver (inlays), niello H: 71.1 cm (27.9 in), L: 81.3 cm (32.0 in), W: 52.4 cm (20.6 in)

Very few Roman bronze tables have survived; among them, this one is an outstanding example because of its considerable size and elaborate decoration. The rectangular top is supported by four slender legs of intricate composition: each leg is a combination of straight, convex, and concave parts. Only the upper part suggests an architectural element (shaped as a pilaster capital with ivy-leaf cymation); the middle part is a fantasy combination consisting of an acanthus scroll with a springing wolf’s head set above the animal’s lower leg and paw. Animal paws as finials of furniture legs are typical for Greek and Roman chairs, stools, candelabra, and tripods; however, the spatial arrangements of all three parts of the leg in this piece make them look like individual sculptures.

The quality of sculptural modeling of the animal heads is remarkable. The bronze maker does not miss any detail: the strands of the thick mane are plastically rendered, with the incision of separate locks; the eyes are pierced so that the deep shadow from the depression creates a strong illusion of an intense gaze; and the canine teeth appear from an open mouth. The look is fierce and aggressive, projecting an apotropaic function. The wolf is associated with Apollo, as well as with Mars and his sons, the future founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, who were adopted by a she-wolf.

Ex- Prof. Luigi Grassi (1858–1937), private collection, Florence (Prof. L. Grassi owned a wellestablished art gallery in Florence in Via Cavour); Arturo Grassi (1899–1971), lived in New York 1945– 1960; Piero Tozzi (1882–1974), Piero Tozzi Galleries, New York, acquired 1 August 1946 (inventory docs: no. 760 dated 1947 & 1953); Peter Tozzi Jr., Piero Tozzi Galleries, New York, inherited in 1974.

Exhibited and Published Smith College Museum of Art, “POMPEIANA” exhibition, Northampton, Massachusetts, November 18–December 15, 1948, no. 16 (one leg).

“

Animal paws as finials of furniture legs are typical for Greek and Roman tables; however, the spatial arrangements of all three parts of the leg in this piece make them look like individual sculptures. ”

Cerberus, the hound of hades

On their visits to the Underworld, Hermes or Hecate could not miss seeing the monstrous guard at its gates, the three-headed dog Cerberus, the hound of Hades, who was there to prevent the escape of the shades of the dead. Different authors report different numbers of its heads; it could be fifty or even a hundred, in addition to many snakes covering its skin. The terrifying beast was captured by the fearless Herakles in his Twelfth and final Labor ordered by King Eurystheus, who devised “no other task mightier than this” (Homer, Odyssey XI, 624).

Cerberus had a brother, the monstruous hound Orthrus, a twoheaded, serpent-tailed dog, who guarded the cattle of Geryon on the island of Erytheia. For his Tenth Labor, Herakles slew both Orthrus and his master.

A sea-monster, the dangerous skylla Skylla is a mythological beast most famously described in Homer’s Odyssey on Odysseus’s journey home: inside the cave “lives Skylla, yelping hideously; her voice is no deeper that a young puppy’s but she herself is a fearsome monster; no one could see her and still be happy, not even a god if he went that way. She has twelve feet all dangling down, six long necks with a grisly head on each of them, and in each head a triple row of crowded and close-set teeth, fraught with black death—these were dreadful dog-heads” (XII, 85–88).

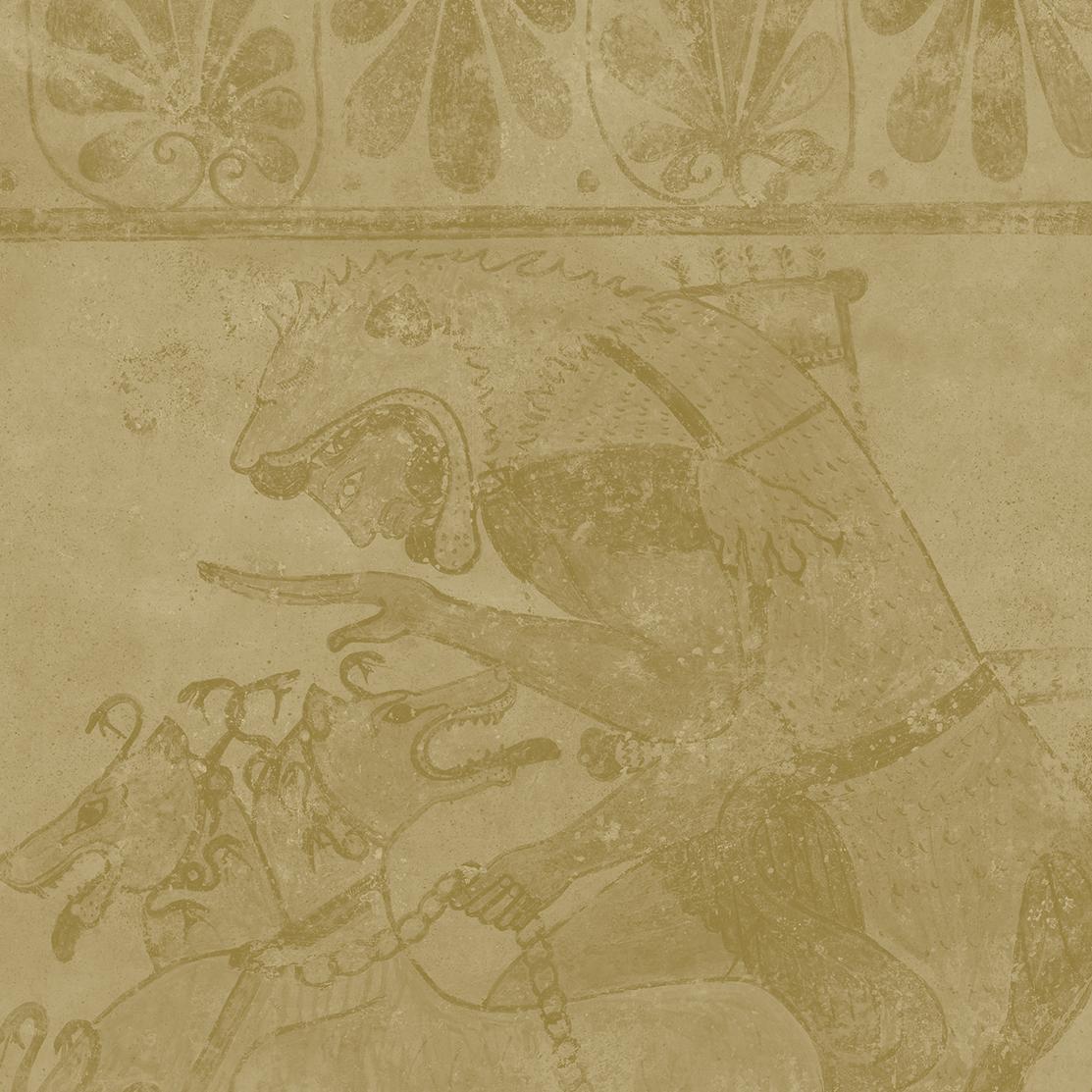

The image of Skylla, attested in Attic red-figure pottery as early as the 5th century B.C., became especially popular in the decorative arts (silver, bronze, and terracotta medallions, appliqués, and statuettes) of the Western Greek colonies in the 4th century B.C. and the Hellenistic period. The most spectacular monumental composition appears in the colossal marble group of Skylla known through the sculpture found in the grotto of Tiberius at Sperlonga (in modern-day Campania, north of Naples; dated to the early 1st century A.D., its bronze original is dated back to the 2nd century B.C.). The dramatic baroque sculpture was designed as a multifigure composition that included the giant figure of Skylla and the ship of Odysseus; the monster emerges from the sea, holds the rudder, and pushes the prow in an attempt to sink the ship while the dogs at her waist snatch and devour the sailors. The terracotta figures on plastic vases, such as the one presented within (see cat. no. 40), could be regarded as forerunners of larger sculptural groups of the Hellenistic period.

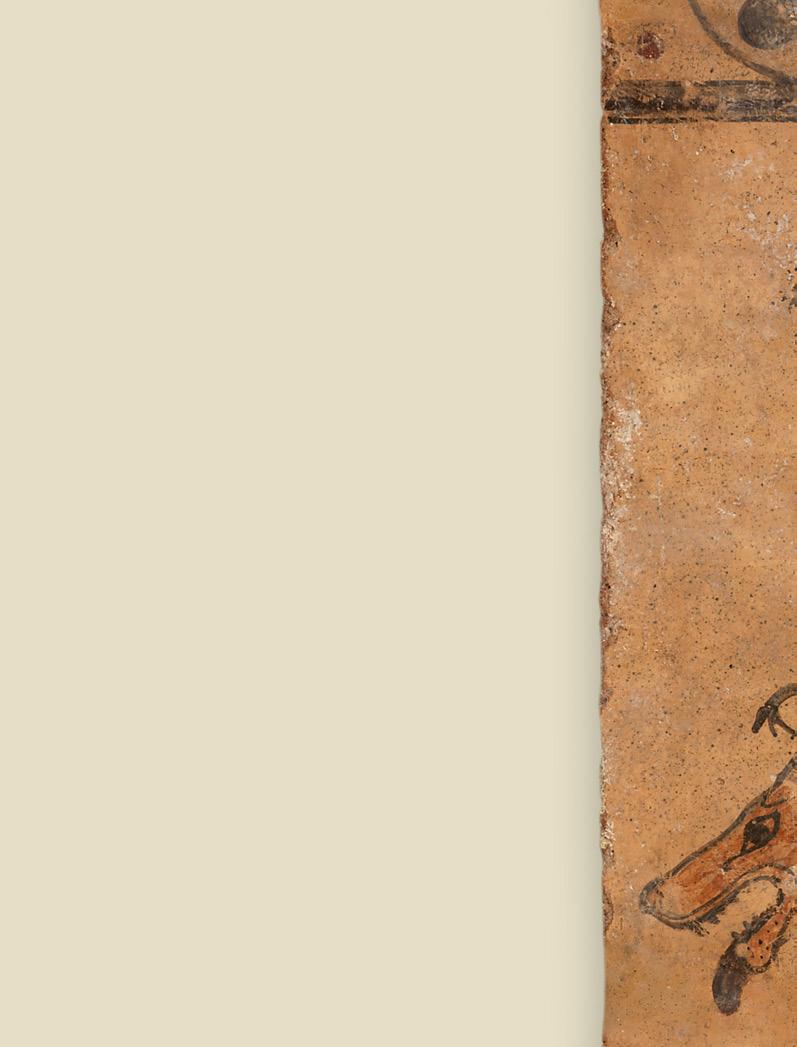

Etruscan, late 6th century B.C. Terracotta, pigments

H: 118 cm (46.4 in), W: 53 cm (20.8 in), Thickness: 3.5 cm (1.3 in)

This extraordinary panel has a figural scene that was executed following the black-figure technique of contemporary vase painting. It depicts the Twelfth Labor of Herakles, when the hero was tasked with descending into Hades to bring the hellish dog Cerberus back to earth, to King Eurystheus. Cerberus is a Greek mythological monster, presented in Hesiod’s Theogony: he has the body of a dog with a dragon’s tail and snakes on his spine. He has an imprecise number of dogs’ heads which varies depending on the ancient author: in iconography, there are, most often, three of them. In mythology, Cerberus is the guardian of the Underworld, chained in front of its gate to prevent the deceased from leaving and the living from possibly visiting them. Aside from this, the only mythological episode in which he appears is linked to the legend of the Labors of Herakles.

The present painting deals with the first part of the story, since Herakles is represented kneeling behind the dog (which he has already chained) and trying to coax him. Despite the monster’s fierce air and his three open and threatening mouths, he now seems to obey the hero and goes to the left with his temporary master (at the end of the story, Herakles returns the dog to Hades). Herakles is easily recognizable by his lion’s skin, which serves as his coat, and his weapons: the sword suspended on the right flank with a thick belt, and, especially, his quiver filled with arrows adorned with tiny feathers. The panel was probably part of a larger architectural set that included other similar paintings, with the subject being all Twelve Labors of Herakles.

Ex- M. Pichotin private collection, Paris, late 1960s; Visconti Gallery, Paris; ex- Mr. & Mrs. C. private collection, Switzerland, acquired in Paris, 1978; imported to Switzerland in 1978.

“

This extraordinary panel depicts the Twelfth Labor of Herakles, when the hero was tasked with descending into Hades to bring the hellish dog Cerberus back to earth. ”

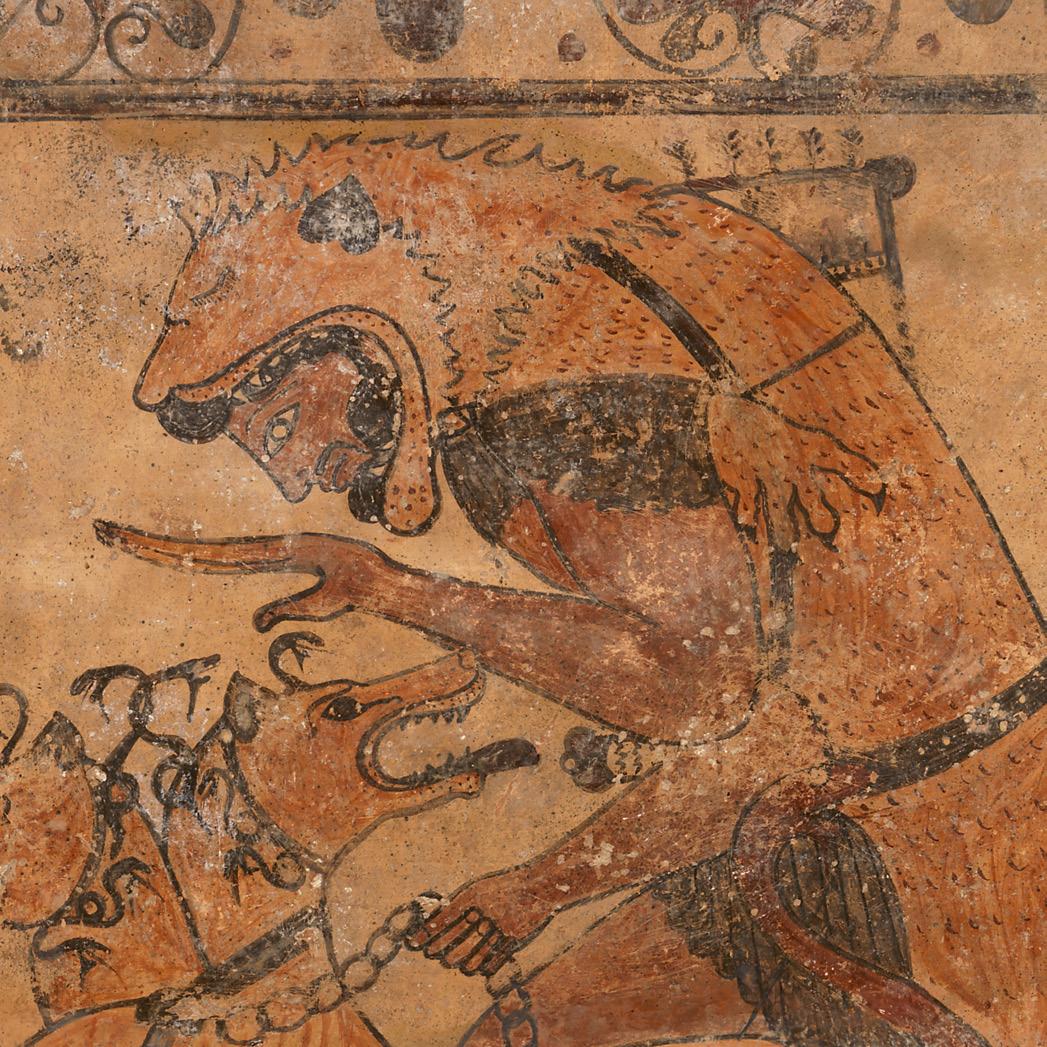

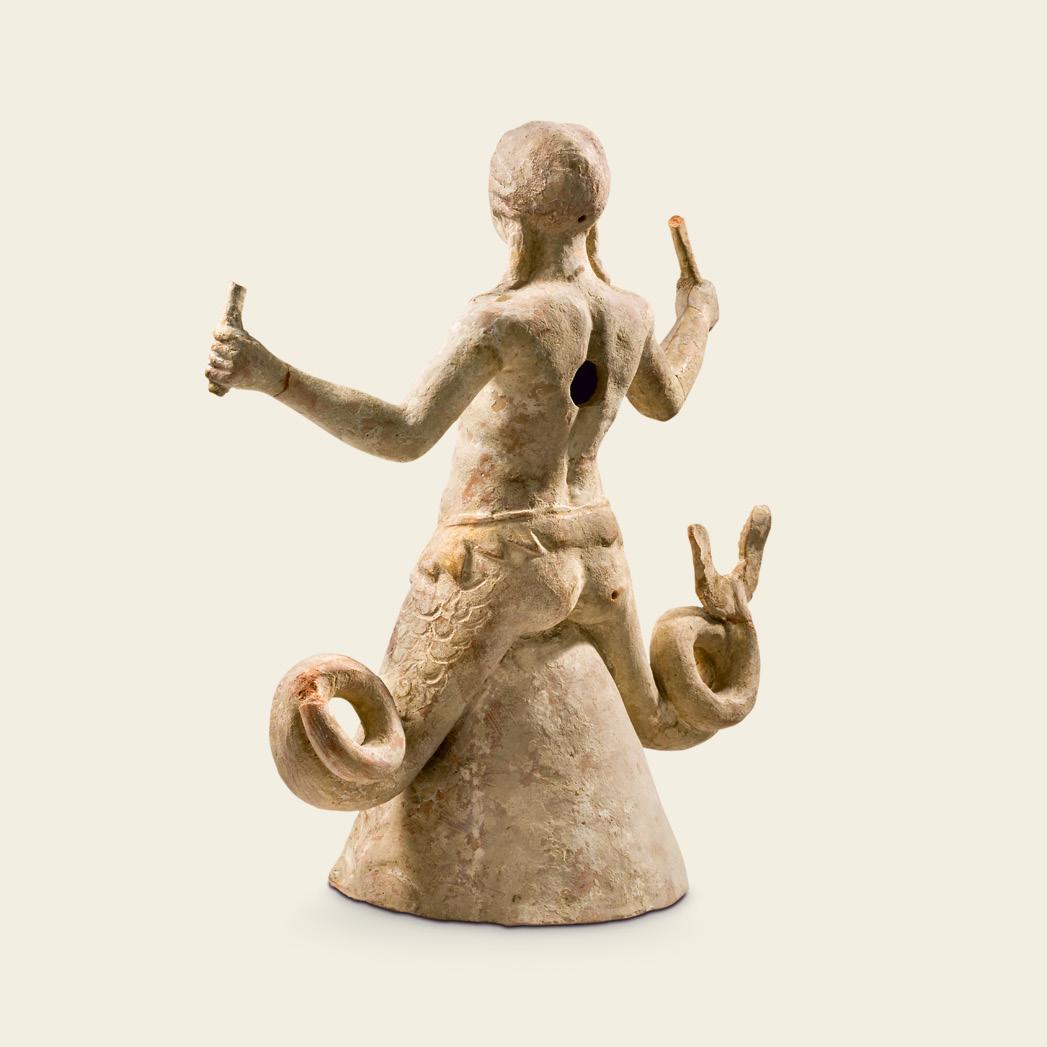

Greek, Canosan, ca. 300 B.C.

Terracotta, pigments H: 37.0 cm (14.5 in), D: 23.5 cm (9.2 in)

The usual shape of the askos (flask with an ample body resembling a wineskin and a handle meeting the spout) was transformed into a sculptural presentation of the mythological group of Skylla; the figures take the place of a handle and overlap the vessel’s spout. The hybrid monster has the long, twisted body of a fish, the upper body of a young woman, with raised wings behind, and several limbs shaped as dogs emanating from her hips. The group is fully three-dimensional, emphasized by the front and side projections of the dogs looking to snatch their victims. The female torso is frontal: Skylla leads the attacking action, directing the front dog with her left arm while grasping a fish (that resembles a small dolphin) with her right hand. The terracotta surface was initially covered with white slip and painted. The dogs were painted red; the remains of color are also seen on the body’s ornaments of scrolls and palmettes; a large palmette is fully preserved on the rear side.

Provenance Ex- Swiss private collection, 1960s.

Published Hellas & Roma, Art grec insolite, Terres cuites hellénistique de Grande Grèce dans les collections privées genevoises, Geneva, 1988, p. 8, n° 2 (ill.).

Greek, Sicilian, late 5th century B.C. Terracotta L: 17.5 cm (6.8 in)

With a frightening visage, the mythical female monster Skylla adorns the front of this unusually shaped askos. Transformed by a Sicilian artist into a highly animated ceramic decoration, she wears a necklace and an amulet. Her neatly coiffed, curly hair frames her forehead, above which is the circular mouth of the askos. With her sphinx-like, empty expression, emphasized by staring eyes and thin lips, Skylla’s appearance does little to convince us of her humanity or good intentions. A double ribbed handle extends from the back of Skylla’s neck to the exterior part of the vessel where it takes on a new function as the two ribs loop around on either side of the vessel and terminate in open-mouthed, writhing snakes. Two dogs’ heads sprout up from Skylla’s shoulders, from which arms with hands resembling snakes’ heads arch around prominently featured breasts; she kneels on tubular-shaped forelegs. Dark brown glaze accentuates face and hair, arms, feet, handle, snakes, the dogs’ heads, spout, and rim of the mouth. Highly unusual and almost unique in its representation of Skylla, this askos type (with suspension lugs or handles, the wide mouth for ease of filling and the narrow spout for pouring) was intended for cult purposes and the pouring of libations.

Provenance Sotheby’s, London, 29 March 1971, lot 130; Sotheby’s, London, 10 July 1979, lot 270; ex- Clark collection, Michigan.

Exhibited Detroit Institute of Art, 1983–2004.

Greek, Hellenistic, 3rd–2nd century B.C. Terracotta, remains of pigments H: 28.6 cm (11.2 in)

A cone-shaped base covered with an incised wavy pattern to indicate water supports the figure of the female monster Skylla emerging from the sea. The fantastic creature is imaged as half-human, half-beast; long curling tails of a dragon covered with fish scales take the place of human legs. Skylla appears as a beautiful maiden, with a charming and pleasant expression on her face, which has regular features. Her hairstyle is carefully arranged: the hair parted above the forehead is spread over her bare shoulders in long tresses. The nudity of the upper torso makes the look of the young girl even more attractive; however, the beauty hides the danger of her powers.

In this example and several others, the monster’s waist is not surrounded by dogs; rather, fish fins with a central floral element are arranged like a belt. Skylla is represented upright, with two hands grasping the rudder of a ship and probably the anchor or oar, reminders of her attack. The composition of the figure with human arms and serpentine coils extended to the sides is symmetrical and well-balanced. The remains of pigments (blue, yellow) testify that initially the piece was painted and had a vivid, decorative appearance.

Ex- estate of Dr. Jacob Hirsch (1874–1955), New York; ex- Tom Verzi collection, New York; ex- Sheldon and Barbara Breitbart collection, New York–Arizona, acquired in 1966.

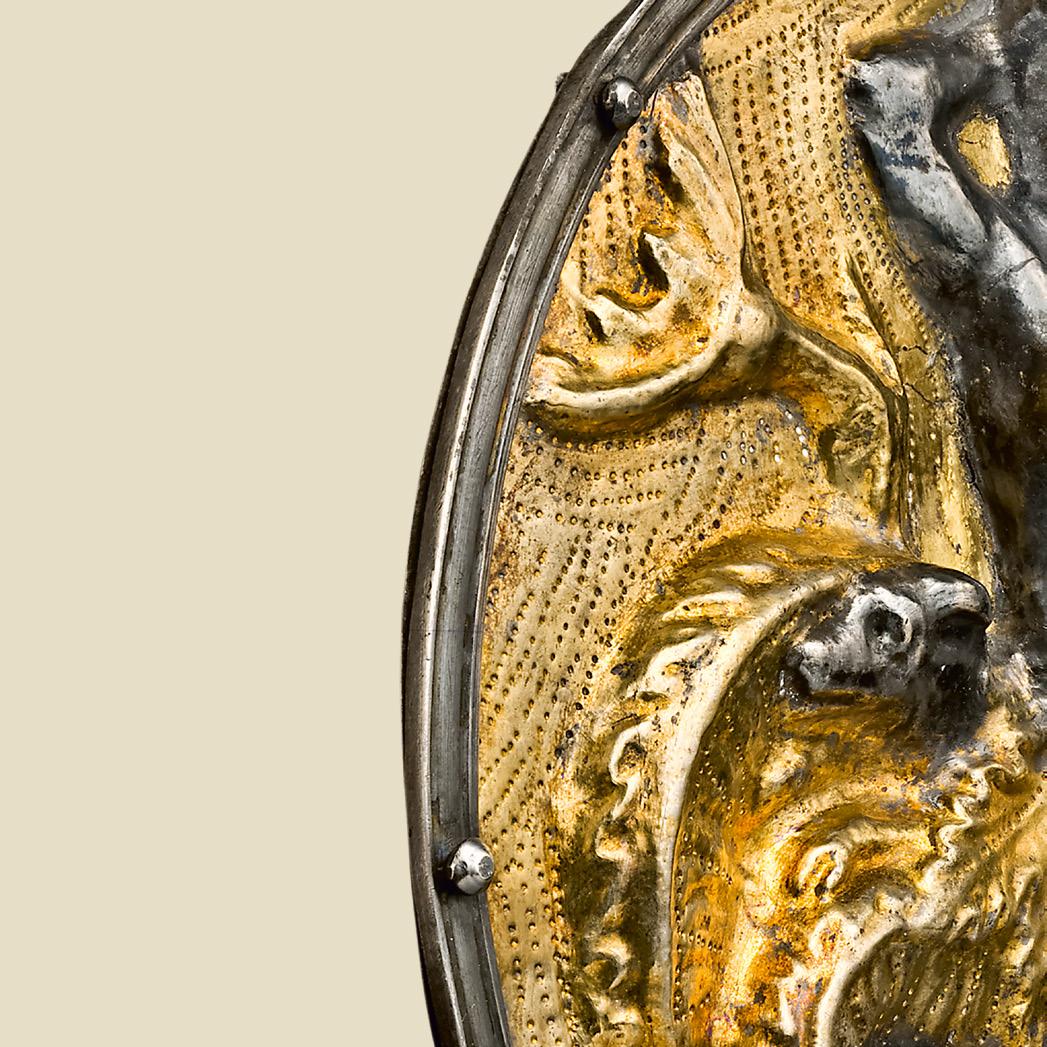

Roman, 1st century B.C.–1st century A.D.

Gilded silver D: 16.9 cm (6.6 in)

This roundel, or tondo, was hammered from a silver plaque and then decorated in repoussé from the inside to represent the figural scene. For the two-colored effect, extensive gilding was applied to the background (sky and sea), to the body of the sea monster, and to her skirt comprised of acanthus leaves. Skylla is represented upright, grasping the rudder of a ship in her hands. Her serpentine volutes enclose two sailors, whose bodies are dislocated, while three dogs’ heads appear between the large leaves forming her skirt. The sky is rendered by regular curved lines, while the waves of the sea form a lively surface in low relief. The object is outstanding both for its weight and for its diameter (well above average size), making this example one of the largest specimens attested.

Ex- private collection, London, acquired before 1962; ex- Maître Jean Clostre collection, Geneva.

The use of dogs in ancient warfare was limited and uncommon. The poet of the epic battle of Troy, who mentions nine dogs of Achilles fed beneath his table (Iliad, X, 173), two of which were sacrificed on the funerary pyre of Patroclus, never speaks of dogs in actual combat. In contrast, the Roman author Aelian (Claudius Aelianus), writing about events that probably happened in the first half of the 7th century B.C., describes the combat of the Magnetes, who border upon the Mæander River in Asia Minor, against the Ephesians: “When hand-to-hand combat began, then the dogs, released forward, brought confusion into the formation of the enemy, for they turned out to be terrible, wild and ferocious” (Varia Historia, XIV, 46). Herodotus reports that when Xerxes invaded Greece in the early 5th century B.C., the Persian army was accompanied by Indian dogs (7, 187); presumably, these were guard dogs. When Strabo names the goods of Britain, he mentions “the dogs sagacious in hunting; the Kelts use these, as well as their native dogs, for the purposes of war” (Geography, IV, 5, 2).

In later periods, it became more common to train dogs to ensure the security of city walls and towers, to use in patrol, and even to deliver messages. Nevertheless, the memory of dogs trained in combat in Asia Minor survived in the figurative arts. Fighter dogs are represented on the Pergamon Altar, where they fight on the side of the Olympians: in the scene with Hecate, two massive dogs with long ears and long hair appear on the sides of the goddess attacking and biting the Giants.

Roman, 1st–2nd century A.D. Marble

H: 28.2 cm (11.1 in)

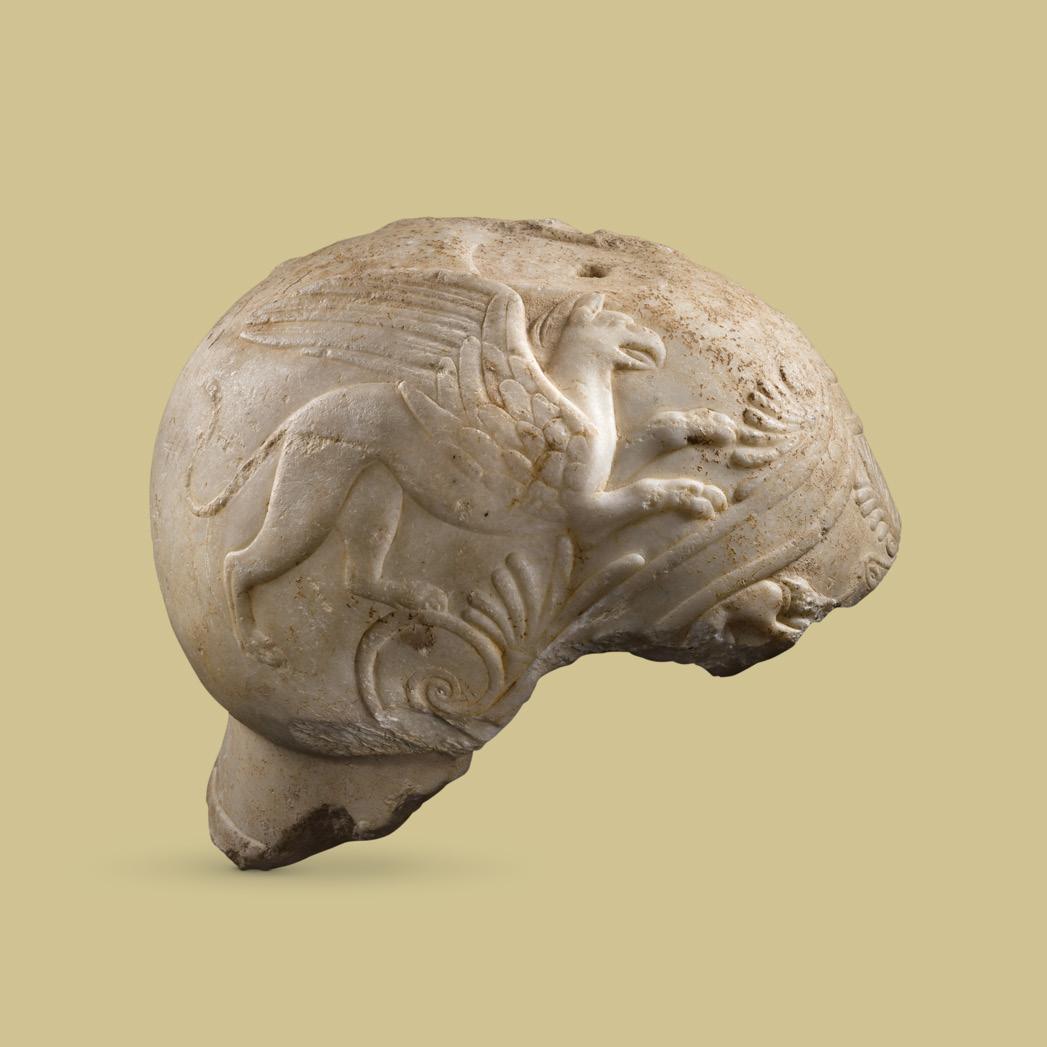

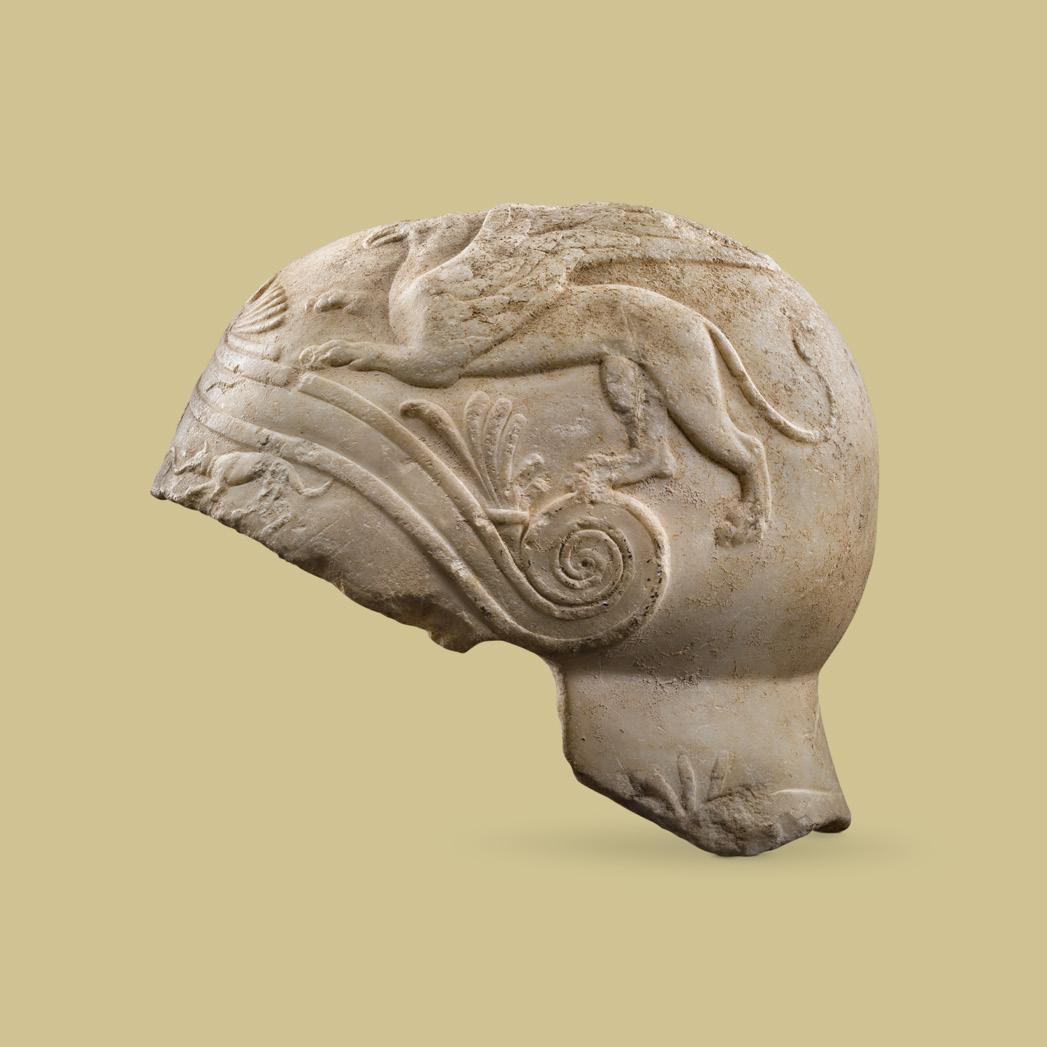

The helmet with decorative reliefs has constituted an important part of the marble figure designated as the Ares Borghese type. It represents a standing youth, nude except for a helmet; according to the reconstruction of the prototype, he held a shield on his left arm. The athletic body stands in a calm and confident pose, with well-articulated musculature.

The helmet itself was classified as belonging to a pseudo-Attic type that had been in use since the early Hellenistic period. The representation does not have cheek guards. The rear cranium of the marble helmet is supplied with a neck protector and decorated with half-palmettes on each side. A flattened zone on the top and a drilled hole were prepared to affix the separately made crest (probably from a different material); in some variants, the support of the crest is shaped as the figure of a crouching sphinx. The figural design on each side of the cranium is identical, including the representation of winged griffins. The visor terminating in volutes has a peaked frontlet. Its linear pattern is combined with symmetrical figural and ornamental motifs: the heraldic composition places one dog on either side of a central palmette with scrolling tendrils; half-palmettes, placed beside the volutes, adorn the peak. The dogs with long snouts, short ears, long tails, and sleek bodies are identified as of Laconian, or Spartan, breed. A story told by Pausanias, who describes the sacrifice of puppies dedicated to Ares at a sanctuary near Sparta (Description of Greece 3, 14, 9), may explain the presence of these dogs on this helmet of Ares.

Ex- McAlpine Ancient Art, London; Ex- American private collection, 1985.

The domestication of dogs from wolves in Western Asia occurred about 12,000 years ago. Since the most ancient period in Mesopotamia, dogs were used in hunting (stag, boar, lion), and they were also trained as watchdogs to guard the flocks. Sumerian cuneiform documents testify to the existence of dog farms. In the 4th and the 3rd millennium, representations of dogs spread throughout the entire Near Eastern world, from Egypt to Mesopotamia, from Elam to northeastern Iran, and to the cultures of the Indus. Hunting dogs are best known as ferocious mastiffs depicted in scenes of the royal hunt on Assyrian reliefs from the palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (7th century B.C.), and the same mastiffs were represented as powerful guardians in lifesized seated statues of the Achaemenid period at Persepolis.

Dogs played a significant role in religious beliefs since they were associated with certain gods (Enlil, Marduk, Ninurta, and Ea). Texts reveal that Marduk, the patron deity of the city of Babylon, possessed four dogs. Inscriptions name the dog as a symbol of the goddess of healing Gula, also called Ninisina. Like the goddess herself, the dogs were believed to possess magical healing powers (specifically, their tongues and saliva). Worshippers brought many clay figurines of dogs to her temple as votive offerings. The records of King Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 B.C.) specifically name the placing of gold, silver, and bronze statuettes of dogs “whose limbs were strong, whose bodily proportions were massive” as deposits in the gates of Gula’s temple at Babylon.

Images of dogs also had an apotropaic meaning and were often placed as foundation deposits to avert evil influences. Ritual texts indicate the canonical number and the colors that should be used to paint the figurines; they also direct that the name of each dog be inscribed on its back. “Biter of his Enemy,” “Catcher of the Enemy”—such names are known from the finds at Kish. A set of five clay figurines of dogs that was found in the North Palace at Nineveh had different inscriptions, such as “Loud is his bark,” “Don’t think, bite!”

The earliest representations of dogs are found in Egyptian Neolithic rock art of the Western and Eastern Deserts. Studies of the great number of depicted animals show that the ancient Egyptians were making an intentional effort to create and maintain specific breeds. One of them is a watchdog known in two types: a slender, curly-tailed canine with erect ears; and a lop-eared creature with a shorter, heavier muzzle and a curved tail. There were also shortlimbed dogs and mastiffs. As elsewhere, the Egyptian dogs were guards, hunting companions, status symbols, and favored pets; about seventy dogs’ names are known from texts and inscriptions (for example: “The Tail is a Lion’s,” “Brave One,” “Good Watcher”). Many dogs were buried along with their human owners, some with great honors. The tomb of King Antef II of Dynasty XI contained a stele carved with the names of the king’s four dogs and a statue group of them.

A number of canine deities in Egyptian religion exhibit qualities of wild canids: the wolf, the jackal, and the dog. Anubis, the most important funerary god, related to burial and afterlife, “lord of the sacred land,” combined the physical features of both the jackal and the dog; the animal head was attached to a human body. Anubis was associated with the cult of Isis and Osiris. According to myth, dogs accompanied Isis during her search for Osiris and protected her from wild animals. Mummified dogs were found as votives where Anubis was worshipped.

Near Eastern, Late Uruk–Djemdet Nasr Period, ca. 3300–2900 B.C. Calcite; stone 3 cm, 3.6 cm, 2.7 cm, 2.7 cm, 3.4 cm, 2.2 cm, 3.6 cm, 3.8 cm, 4.5 cm

Massive shaggy dogs are recognizable among the carved images on stamp seals from the Late Uruk–Djemdet Nasr period (ca. 3300–2900 B.C.). Because of the schematic style of their representation, they are often described as quadrupeds or canids, but some undoubtedly retain the dog’s anatomy and attitude (such as pointed ears and turned-up tails). Images of dogs appear as individual representations, and, as guards of the flocks, they also accompany pictures of sheep. With the action of sealing to protect property (a box, a storage jar, a storeroom), the stamp seals acquired an amuletic value and became a symbol of protection.

Ex- Mr. Duroc-Danner private family collection, London–Geneva, acquired between 1950 and 1970; Private collection.

36322, 36321, 36486 37141, 37137, 36583 36585, 36590, 36595

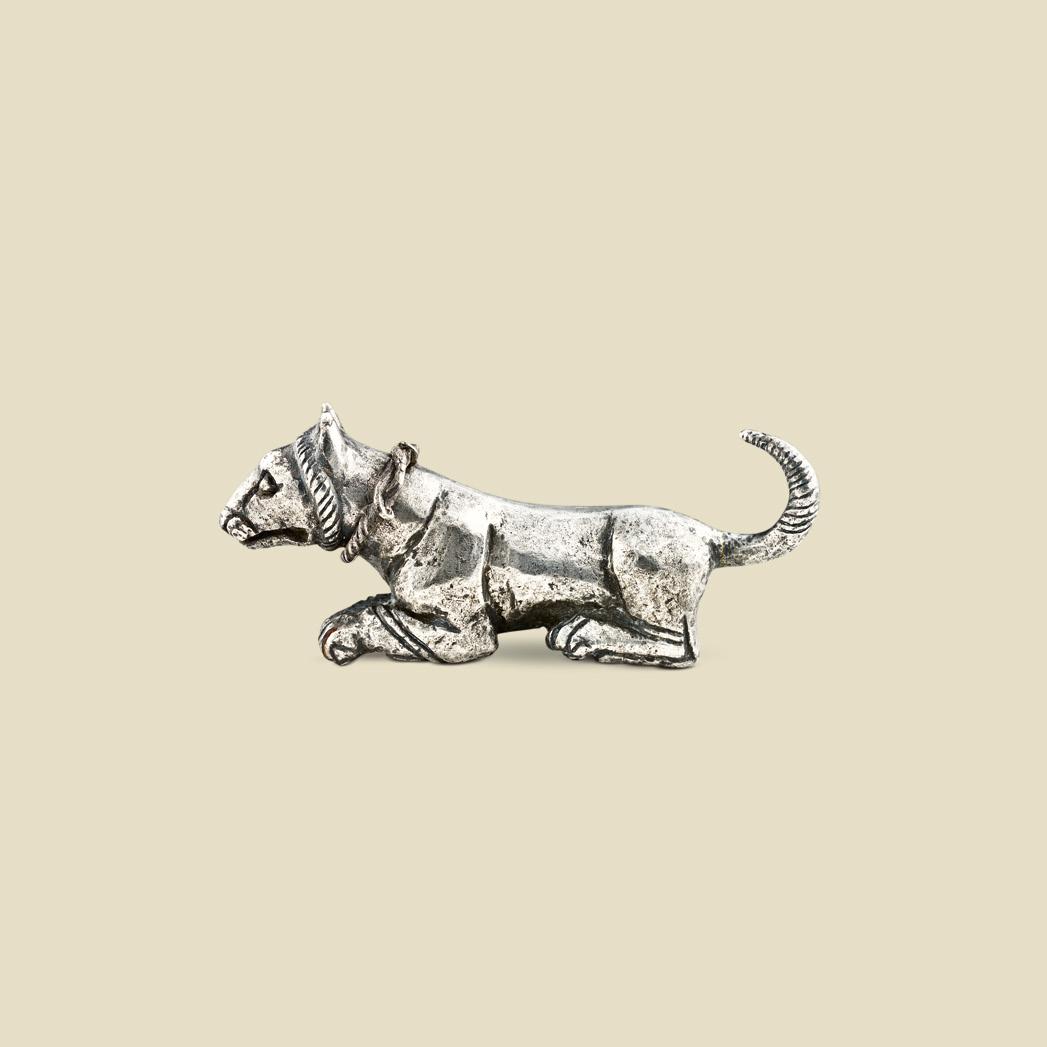

Proto-Elamite, ca. 3rd millennium B.C. Silver L: 11.7 cm (4.6 in); weight: 485 g (1.06 lb)

The outstanding state of preservation and the technical skills of the craftsman make this object a true masterpiece. The statuette of a seated hound is solid cast in precious silver; both its dimensions and its weight are truly impressive. The composition of the seated animal is marked by the well-observed details of its attitude: the dog’s tail is raised; the head is directed toward an invisible prey. Although such an attitude is close to that of felines (lions in particular), it is more probable that the sculptor wished to represent a canid: the pointed shape of the muzzle, the raised tail, and especially the collar (which is completely separate and made of a twisted silver wire) are all characteristics of a dog. Both incisions and sculptural modeling were employed to shape the dog’s specific anatomical details. Figurines made of solid precious metal are incredibly rare in Mesopotamian art.

Provenance Ex- de Chambrier private collection, Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 1966.

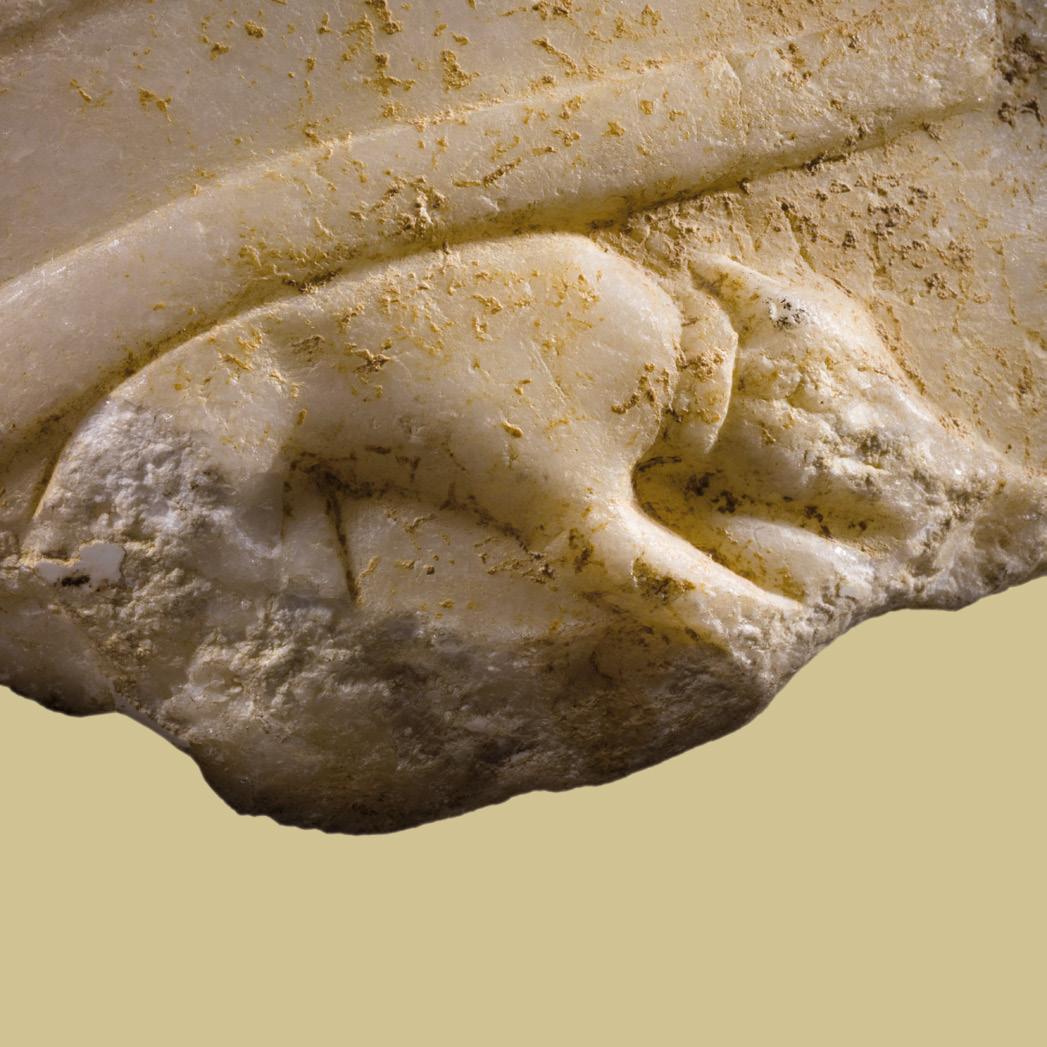

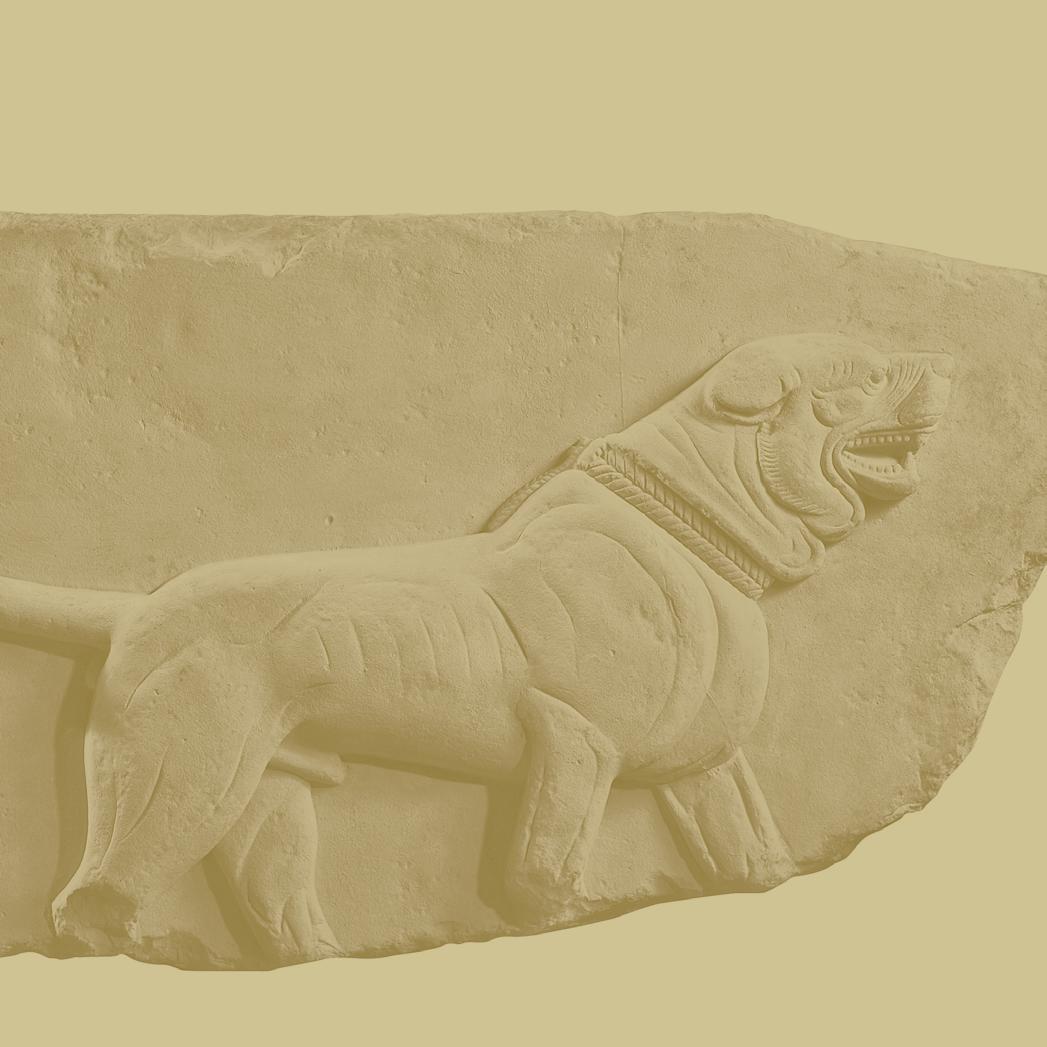

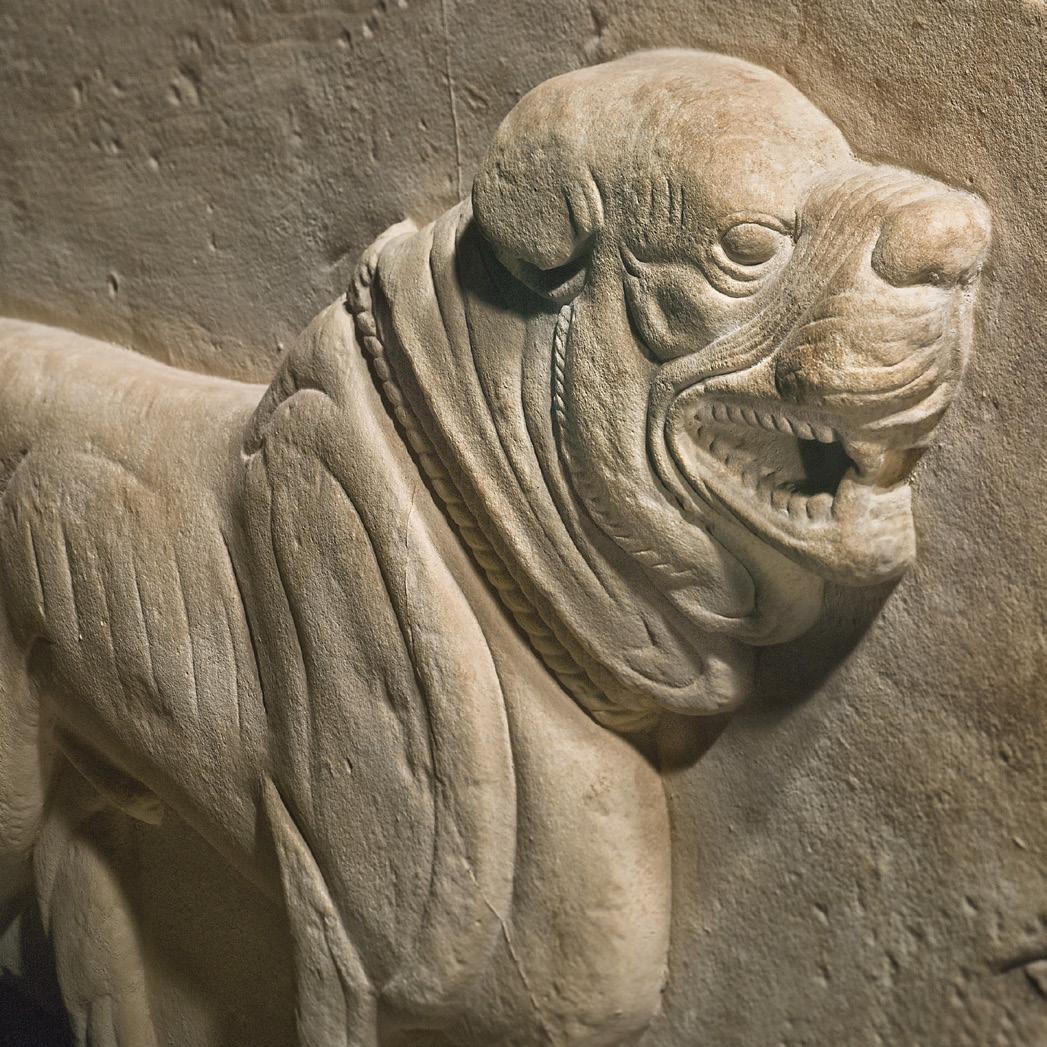

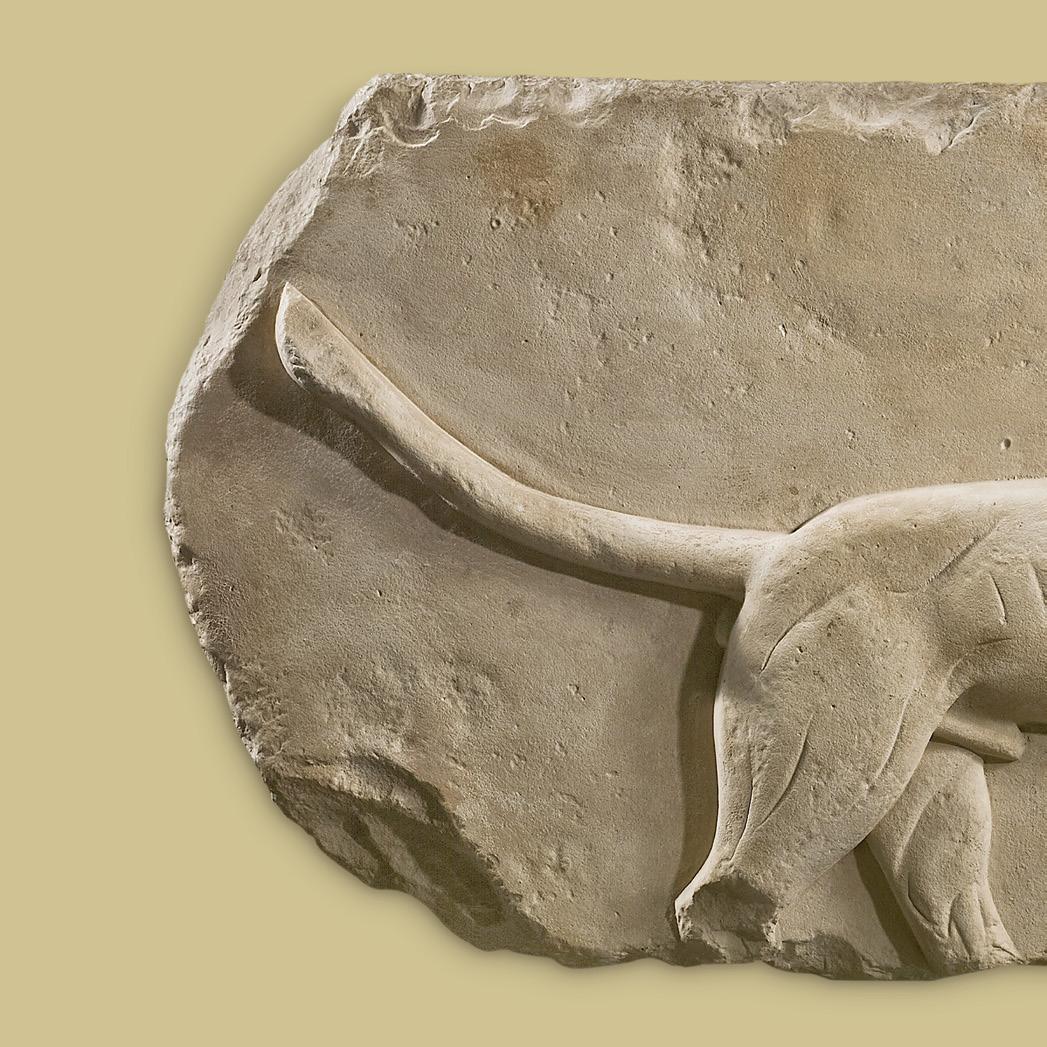

Old Babylonian, ca. 1900–1584 B.C. Limestone with traces of pigment L: 97.5 cm (39 in), H: 51.0 cm (25 in)

Depicted in strict profile, this majestic dog strides with confidence and grace with his long tail poised behind him. Wearing a braided collar that still bears traces of its original dark red pigment, this animal possesses a sense of strength and quiet power. His body is muscular and taut, his proportions refined. The facial features, including the wrinkles of his muzzle and folds of skin around his neck, are stylized, adding to the aesthetic appeal of the piece. The dog depicted is most likely a mastiff, a type of dog often depicted in Old Babylonian art.

This relief was probably part of a large architectural complex, such as a religious altar or shrine, due to the sacred nature of the dog in ancient Near Eastern religion. In turn, the monumental scale of this relief, as well as the refined execution and composition, suggests that this was a commission of the highest order. This magnificent relief most likely represents the personification of Health, as the dog, who embodies physical perfection and prowess, often stood as a substitute for the actual depiction of Gula, the goddess of Health.

Ex- European private collection, Italy–Switzerland, acquired before 1940; imported to the US in 2001.

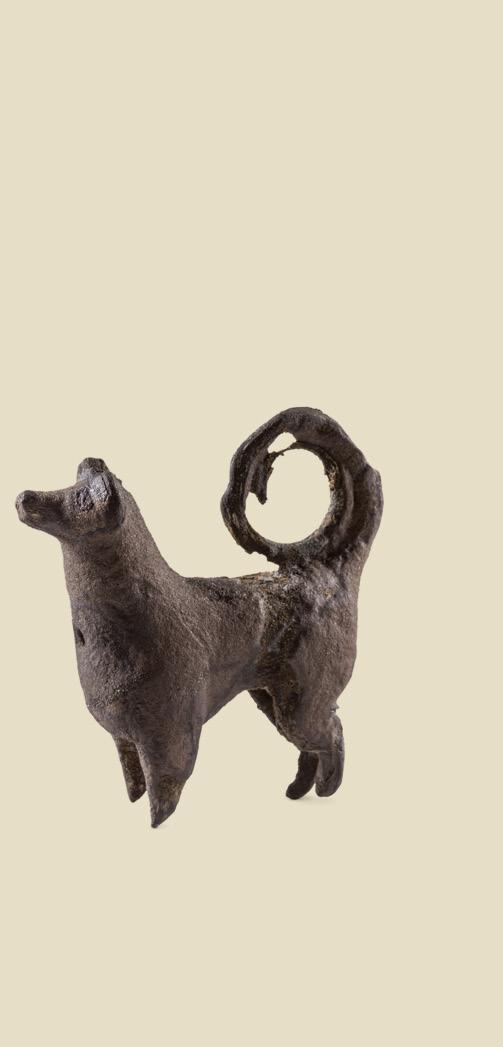

Proto-Sumerian, ca. 3300–3000 B.C. Silver

H: 4.2 cm (1.6 in); H: 4.0 cm (1.5 in); H: 4.0 cm (1.5 in); H: 3.2 cm (1.2 in)

The cast silver figurines were most probably amulets believed to possess protective powers. The modeling of each small sculpture displays knowledge of the anatomy and proportions of the animal’s body; ears and muzzles are well articulated. In each piece, the naturalistic treatment is combined with a rather schematic long tail, thick at the base and coiled like a hunting horn.

Ex- private collection, Switzerland, 2001.

Egyptian, Late Period, 26th Dynasty, 7th–6th century B.C. Gypsum plaster, pigments H: 11.1 cm (4.3 in)

This head represents Anubis, the canine god, who was considered the most important Egyptian funerary deity before the rise of the cult of Osiris. Leader of the dead and lord of the sacred land (desert areas where the cemeteries were situated), he was specifically called a master of the place where embalming was carried out. In myth, it was Anubis who embalmed the body of Osiris and the deceased king.

The head was carved in limestone, often used by Egyptian sculptors on account of its malleability. The animal’s features are accurately rendered and immediately recognizable: long pointed ears, eyes set close to each other, long muzzle, and a mane with incised lines representing strands of fur. Although the head’s color is limited mainly to black (symbol of the fertile, regenerative earth), the expressiveness of the image, especially around the eyes, is remarkable; here, where the iris is set close to the upper eyelid, the representation reproduces a direct and fixed gaze. The erect ears strengthen the alert attitude. A headcloth, which rests behind the ears, creates a round shape on the back of the head; two lappets frame the sides of the narrow neck. The encircling ring below the neck is part of a pectoral. Statues of Anubis have been found in many temple chapels; his images have also been discovered inside tombs.

Private family collection, assembled in the 1970s–1980s.

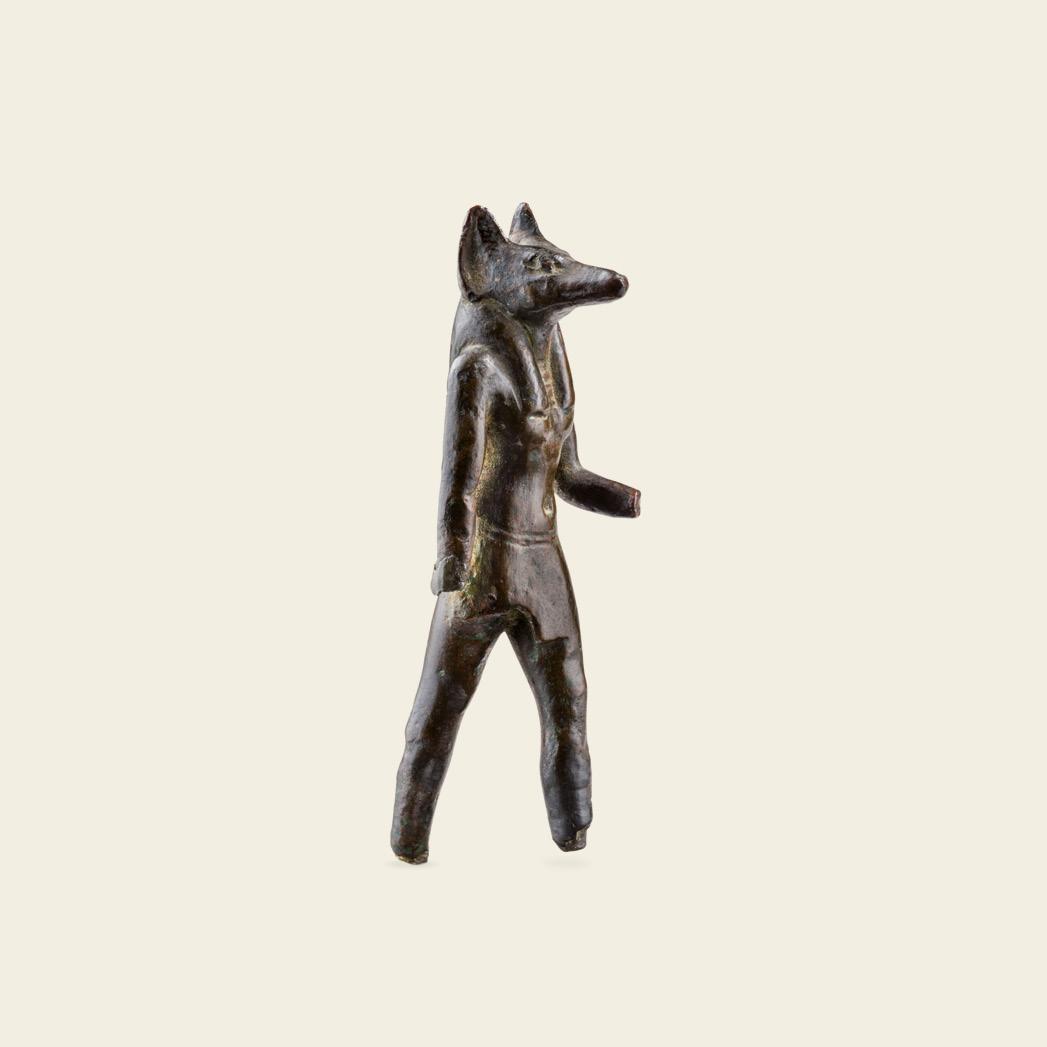

Egyptian, Late Period, ca. 716–30 B.C. Bronze H: 10.8 cm (4.2 in)

The striding jackal-headed god wears a short royal kilt, broad collar, and tripartite wig; he was formerly holding the ankh in one hand and the waj-scepter in the other.

Sotheby's, New York, 14 December 1993, lot 394; The Gilbert collection, Cambridge, Massachusetts, acquired in New York, 14 December 1993.

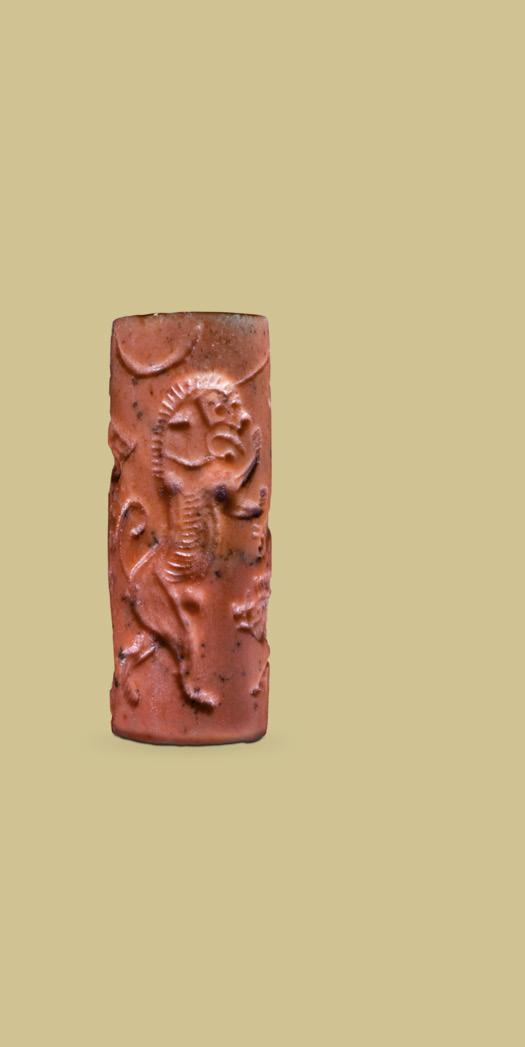

Neo-Assyrian, ca. 800–600 B.C.

Chalcedony H: 2.0 cm (0.7 in), L: 1.6 cm (0.6 in)

One of the finest of its type in existence, this conoid stamp seal pierced through the top has curving faces. On the base, a standing goddess with four wings, Lamashtu, is represented holding objects in each raised hand. She is depicted frontally save for the head, which is sideways. She wears a robe that is thrown back to expose her body. On one of the sides is a lunar crescent with a figure of Sîn, the moon-god, who is shown from the thighs up, raising one hand; he has a long beard and a round hat with a knob on the flat top. Beneath the crescent are two boat-like structures, each with a disc and rays beaming from it. On each side of this lunar god and the boats is a merman wearing a domed hat with a knob. On the other major side is the demon Pazuzu: looking human in shape, he has four wings, talons of a bird of prey substituting for feet, and a lower body covered with snakeskin. His bizarre head is square-shaped, with furrowed brow, snarling lion-like face, wrinkled cheeks, small rounded ears, fringed beard, and lined neck. He raises one hand while lowering the other. To his left on the adjacent face is a big dog seated on its haunches, symbol of the healing goddess Gula.

Provenance Ex- Surena collection, London, 1997.

AELIAN, Historical Miscellany, Loeb Classical Library, translated by N. G. Wilson, Cambridge, MA, London, 1997.

AESOP’S FABLES, translated by L. Gibbs, Oxford, New York, 2002.

COLUMELLA, On Agriculture, De Re Rustica, vol. 2 (books 5–9), Loeb Classical Library, translated by E. S. Forster and Edward H. Heffner, Cambridge, MA, 1954.

THE EPIGRAMS BY MARTIAL, Bohn’s Classical Library, London, 1897.