7 minute read

Electrified mine fleets: Off the starting blocks

Four years after Newmont Goldcorp made history with the world’s first all-electric gold mine at the Borden site in Ontario, Canada, fleet electrification has gathered a lot of pace. Almost all tier 1 mining companies are currently trialling electric equipment, from small ancillary vehicles to massive hauling trucks — the holy grail of carbon-free mining.

In Australia alone, BHP has begun operating 16 battery-electric Epiroc Jumbos at Olympic Dam; Rio Tinto is testing the Caterpillar battery electric 793 mining truck at its new Gudai Darri iron ore mine; AngloGold Ashanti is trialling a 65-ton Sandvik electric underground mining truck at the Sunrise Dam site; and Fortescue is preparing to deploy a 240-ton electric mining haul truck developed in partnership with Liebherr.

Advertisement

While the race to full fleet electrification is still very much in its first few laps, the experience gained by first movers is already providing some insights about what this transformation means for the mining industry.

No One Size Fits All

The first thing that has become clear through the development and testing of electric equipment is that even when the sector matures, no one technology will have monopoly. Among the most popular low and zero-carbon technologies that are currently being developed are standalone and trolley-assisted batteryelectric vehicles, hydrogen fuel cell engines, and diesel substitutes. Based on existing pilots, battery- electric equipment appears to be the primary technology miners are betting on.

“We chose the battery-electric approach rather than hydrogen because a lot of our projects are very close to renewable energy sources so it doesn’t make sense to incur the additional cost of transferring those photons through an electrolysis program into hydrogen and then deal with the cost of storing hydrogen prior to filling up your truck, explained Shane Clark, General Manager of Strategy and Growth at MACA. “It makes a lot more sense to use the energy at the source to charge an electric vehicle, and that stationary storage could help firm the grid,” he said, adding that even the players that began their journey with a stronger focus on hydrogen seem to have pivoted towards BEVs, “given how impressive the current battery-electric prototypes are”.

Still, hydrogen will likely have a role to play in the transition, and some equipment manufacturers are working on combining the two technologies. As a case in point, First Mode’s hybrid hydrogen and battery-powered nuGen engine should be available on the market in 2025 following a successful one-year trial at Anglo American’s platinum group metals mine in Mogalakwena, South Africa.

Since each mine presents different needs and characteristics, from location, type of pit, mine life and metal extracted to grid connection and availability of renewable resources, experts recommend evaluating and trialling the most suitable technology at the site before implementing a specific solution at a larger scale.

“There is no one solution that fits every mine or every piece of equipment at the mine or even every application scenario at every mine. The solution will also vary regionally due to the availability of green energy,” explained Michael Lewis, Technical Director at Komatsu. “For example: a deep pit mine with a long life may be best suited for battery/trolley whereas a more shallow pit may be better suited for battery with static charging or hydrogen fuel cell.”

To meet clients’ requirements, Komatsu has adopted a poweragnostic approach to truck development, allowing a mine to purchase a diesel power truck and later retrofit it with one of the company’s decarbonized solutions, such as battery or hydrogen.

Deepening Relationships Between Miners And Oems

Because of this broad diversity in both mine profiles and electrification solutions, finding the right technology for a specific site requires strong collaboration between miners and their OEMs.

For miners, it involves an adjustment from purely transactional relationships, and a willingness to share longer-term plans with their OEMs.

Industry-wide initiatives like the Electric Mine Consortium and the BluVein Consortium are promoting the type of open cooperation needed to accelerate the sector’s transition, but certain OEMs have also launched their own platforms to gather feedback from a variety of potential mining customers. That’s the case of Caterpillar’s Early Learner Program, launched in 2021 with BHP, Freeport-McMoRan, Newmont, Rio Tinto and Teck Resources, or Komatsu’s Greenhouse Gas Alliance, started the same year with Rio Tinto, BHP, Codelco and Boliden.

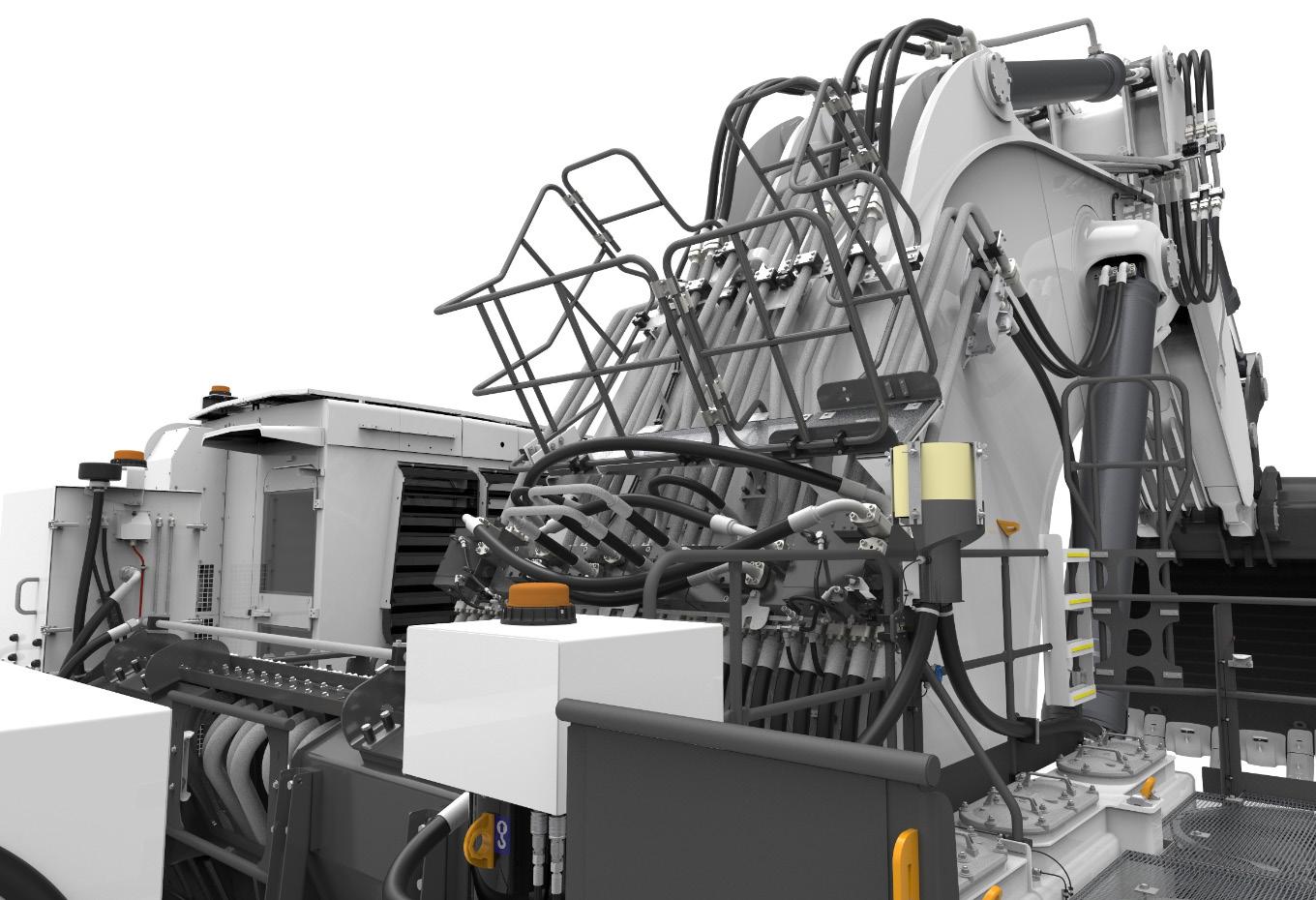

Photo courtesy Liebherr

OEMs are also having to expand the scope of their operations to offer unique solutions aligned with miners’ ambitions and requirements. According to Julian Soles, CEO of First Mode: “OEMs are starting to realise that they need to go much further beyond their traditional boundaries to support miners in this transition, as the change extends beyond the platform itself.”

Overall, OEMs are slowly shifting their focus from the traditional product level to the systems level, and this is going to have an impact on their business models. “We may see OEMs having to provide different payment options, such as leases for batteries or bundling of system elements so miners only need to make monthly payments to smooth out those higher costs,” added Soles.

There is another reason why OEMs might make adjustments to their business models in the future: as the electrification of global transportation progresses, the competition to obtain the materials to manufacture battery-electric vehicles is set to heat up.

“The size and scale of the automotive sector is a challenge for the comparatively small mining sector. The mining industry may have to leverage its position as the primary producer of the key ingredients in the battery supply chain to secure certainty of supply,” explained Paul Murphy, Executive General Manager, Future Industries Project at Liebherr.

Some OEMs are accelerating their development processes in order to lower their waiting times for battery components. Others are choosing slightly different battery chemistries to avoid direct competition with the automotive sector. “Lithium titanate oxide is a power-optimised, long-life chemistry that does not provide the energy density nor cost competitiveness required in automotive applications. For us, the safety, power optimization and higher lifetime contribute to a safer, lower overall total cost of ownership of our solution. Automotive companies have historically used NMC, NCA and some are now looking at LFP, which compete for many of the same raw materials, but have different manufacturing and supply chains to deliver a completed battery cell,” said Soles at First Mode.

NuGen Truck courtesy First Mode

The sector is also likely to become more vertically integrated as OEMs seek to secure the supply of battery minerals they need to build electric fleets.

Filling Technology And Supply Gaps

While we are all watching the development of new types of battery or hydrogen-powered mining vehicles very closely, it’s important to remember that interim solutions, such as hybrid diesel-electric vehicles or truck retrofits, are already available today to help miners achieve decarbonisation targets.

Photo courtesy Liebherr

Of course, switching from diesel to electric vehicles will reduce miners’ carbon footprint — but let’s not forget that manufacturing the tens of thousands of vehicles currently in operation also generated significant emissions. Retrofit solutions offer a relevant alternative to brand new equipment and ensure that operational vehicles are not wasted.

“OEMs transitioning from their current production runs to full BEV is going to be very difficult. They’re going to need robust supply chains out on very long horizons, so more dynamic manufacturers who can work both with the OEMs and battery packaging companies will be out to fill that niche with retrofit solutions,” said Clark at MACA.

But whatever technology they end up choosing, it’s important for miners to begin preparing now for the transition. “The OEMs,distributors and customers need to work together to ensure that their timeline for decarbonisation aligns with the ability to both procure the equipment and technology and enabling infrastructure but also prepare the mine for any process changes required. There will be capacity limitations but effective collaboration between the OEMs and the operators will minimise any mismatch,” advised Lewis at Komatsu.

Decarbonised fleets may still be gathering momentum, but it’s time for miners to begin the journey if they haven’t already. Considering supply chain pressures, starting a transparent conversation and setting expectations with OEMs now could determine whether or not climate goals are met within established deadlines.