6 minute read

Escher and the Optical Illusion

ESCHER

AND THE OPTICAL ILLUSION

Most people have vaguely heard of the name and recall seeing these amazing sketches, but unlike other geniuses such as Dali or Da Vinci, M.C. Escher is a surprisingly unsung artist of undoubted skill and fascination. WORDS MICHEL CRUZ

Day and Night © Vyychan | Dreamstime.com “The flat shape irritates me – I feel like telling my objects, you are too fictitious, lying there next to each other static and frozen: do something, come off the paper and show me what you are capable of! …So I make them come out of the plane.”

Houdini is known as the most magical illusionist, but when it comes to the arts, not even Leonardo Da Vinci or Hieronymus Bosch can hold a pencil to M.C. Escher, the unchallenged master of the optical illusion. Such are the dimensions and depths of field created by this fascinating artist that they boggle the mind and play with the senses. That MC Escher was an artist with the unequalled ability to create the apparently impossible is a given, evoking a cult status that continues to grow.

Born Maurits Cornelis Escher in Leeuwarden, in the Frisian region of The Netherlands, the artist later known as M.C. Escher had a somewhat precarious start to life. Though born to an affluent family in a home that now houses the Princesshof Ceramics Museum, Escher was a sickly child with on-going health conditions that did little to aid his poor grades at school. ›

A mesmerising optical illusion

The intricate detail of the Alhambra was a major source of fascination for M.C. Escher

For most a maze, for Escher pure inspiration The Escher Museum in The Hague, featuring works of the Dutch graphical artist

One skill that stood out throughout all of this was an innate ability to draw, which he practised alongside carpentry and the piano. A brief flirtation with architecture ended due to what Escher himself believed was a lack in mathematical ability, leading him to switch to the field of decorative arts that would become his life’s work. At the time, in the years between the world wars, The Netherlands was home to a rich generation of graphic artists, architects and painters who followed a vernacular version of Art Deco-inspired designs.

INSPIRED BY THE ALHAMBRA

M.C. Escher benefited from this environment, working alongside leading artists as he developed his technical skill and artistic eye. In spite of this, it was visits to Italy, where he would later live, and southern Spain, that formed the vision of the young artist and created the foundations for the mesmerising threedimensional works he would ultimately become known

Classic Escher — Belvedere, 1958 © Vyychan | Dreamstime.com for. Travelling through Andalucía, he became fascinated by the patterned artwork of Moorish buildings, and this unlocked a passion for geometrical symmetry that had lain dormant within.

Though Escher claimed no understanding of maths, he took to this complex geometry like a fish to water, first copying the intricate detail of Moorish tilework and decorative detailing, and later creating his own derivations. The repetitive patterns had a trance-like effect on him, and sparked an interest in a field of mathematics – tessellation – that would form the basis of his artwork. Visiting the Alhambra in 1936, he said of his feverish sketching of its many details: “It remains an extremely absorbing activity, a real mania to which I have become addicted, and from which I sometimes find it hard to tear myself away.”

Thus inspired, he also perfected his technical skills and the ability to reproduce – and ultimately create – incredibly complex and detailed patterns. This evolution in his career was temporarily interrupted by the rising tide of Mussolini’s Fascist Italy, which forced Escher and his Swiss wife to move to Chateaud’Oex in Switzerland, and later to Brussels before settling back in The Netherlands in 1941. Many of his best works date from this period, which formed the prelude to his rise to fame in the 1950s. ›

Try not to get dizzy

THE MYSTERY OF GENIUS

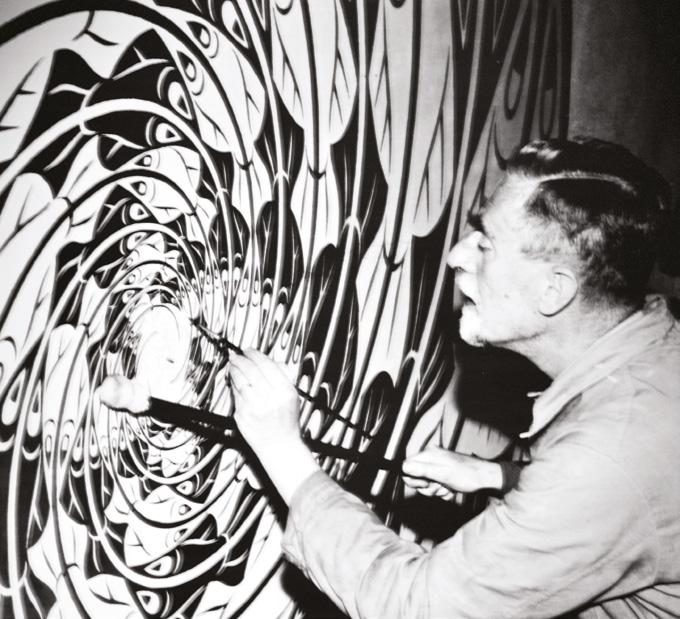

He would also lecture, design stamps for the Dutch authorities and produce artwork for commercial and artistic purposes, but it is his unique take on geometrical relationships that would make him famous. M.C. Escher was awarded the Knighthood of the Order of Orange Nassau in 1955, and in 1967 was made an Officer of the order, shortly before the production of Snakes, a large woodcut with threefold rotational symmetry that would be his last work and the ultimate culmination of his mastery of technical drawing and incredibly complex detail.

The snakes create a meandering pattern of interlocking rings that move on into infinity towards the centre and the edge of a circle. Designed and created with a perfection that was the hallmark of the artist, it is a typical example of the way in which he somehow created full-circle images that, for all their complexity, always remain connected in a logical way. At the heart of this is a perfect mathematical symmetry – quite unusual for someone who professed to have no mathematical skills but is nonetheless regarded as one of the greatest geometrical artists of all time. ›

Classic Escher – enough detail to drive a sane person crazy

Few minds could have conjured up such perfect illusion

Geometry with a sense of humour

Two ‘impossible’ hands with pencils draw each other

The genius of patterns before the onset of computerised images © Vyychan | Dreamstime.com

The mesmerising thing about Escher’s art is that everything works

Escher is immortalised in works that continue to baffle mind and eye just as they did in the previous century. He wouldn’t be the first artist to become more famous after life, but M.C. Escher stands out for the form of his work, with few peers who would even tackle the complexity that marks his oeuvre. Like the mosaics that originally inspired him, pieces such as Reptiles, from 1943, can be viewed as an engaging whole, or in mesmerising detail, and though every element fits to perfection – or maybe because of this – the image appears alive with movement. Just one of the many optical illusions that this alchemist of the artistic form has produced.

It takes a special mind to conceive the complex, interwoven shapes that bring to life the mystical world conjured up by Escher’s works; a special hand to turn them to reality, whether representing animals, landscapes, staircases or machinery, such as in the case of Relativity, House of Stairs and Ascending and Descending, three absolute masterpieces in which art transcends into engineering.

Though others have tried and we now live in a world of computer-aided designs, no-one has been able to recapture the magic of M.C. Escher’s eye for detail and ability to titillate the senses and tickle the brain with such visual illusion. e