5 minute read

SEIZING THE NARRATIVE

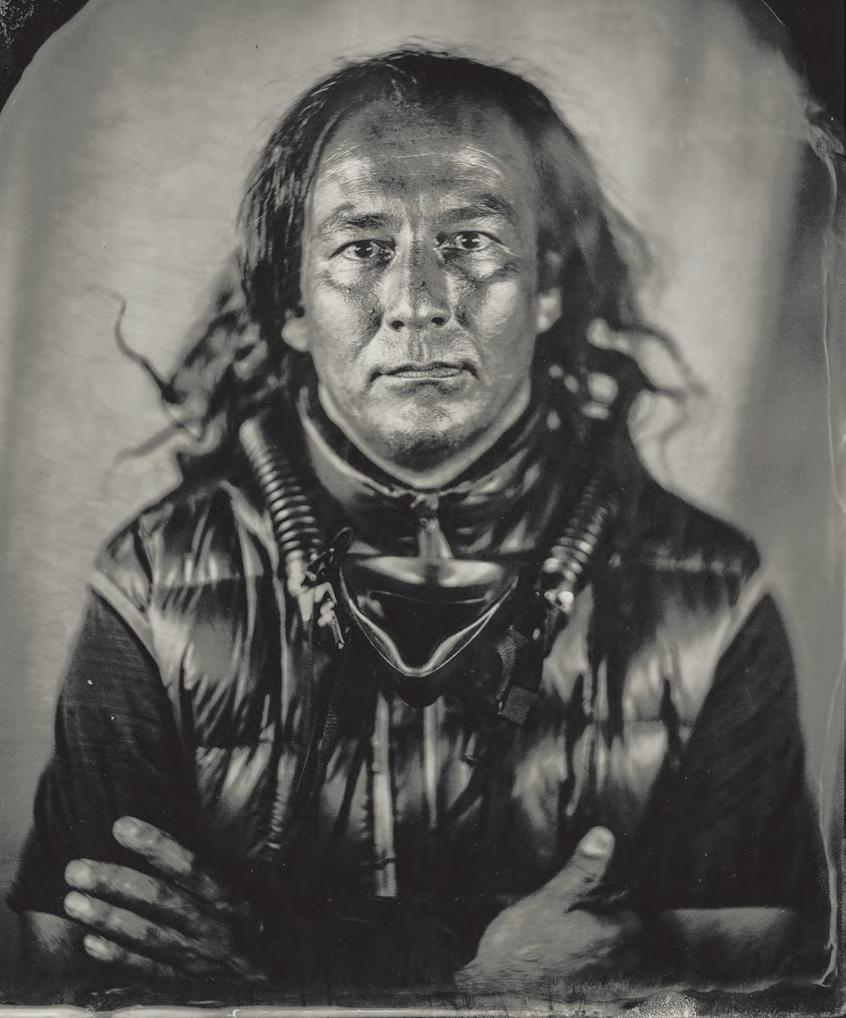

The indigenous people in Will Wilson’s portraits play an active role in how they are represented

BY GINGER WOLFE-SUAREZ

The Mennello Museum of American

Art’s timely exhibition In Conversation: Will Wilson is a compelling and forward-facing exploration of contemporary portraiture. Photographer Will Wilson, Diné (Navajo), has created a body of work that gives the public a deeper understanding of authentic indigenous culture. The exhibition provides the public a point of departure to reflect on the challenges that continue to face the indigenous peoples of America. Hundreds of tribes and communities lived here in Florida for thousands of years, prior to Europeans. What is the photographer’s responsibility to the people they depict, and what is accuracy and truth in contemporary photography?

Indigenous culture has been romanti- cized and inaccurately depicted throughout American history. The people in Will Wilson’s portraits had an active role in the photo-making, and provided cooperation and consent regarding how they were ultimately represented. Those photographed also chose any items they held and had agency in how those objects were depicted as well. Ideas of counter-narrative, the ethics of representation, and the forms of labor it takes for artists and cultural workers to confront bias came to mind. only to indigenous people, but to land in its natural state.

In the portrait of Nakotah LaRance, for example, who is a citizen of the Hopi Nation, LaRance squats rather than sits. He chose headphones; a manga novel and a hoop rest on his lap. The wall texts tell us he has six World Champion Hoop Dancing titles.

Wilson’s photographs are juxtaposed against early 20th-century photographer Edward S. Curtis’ images from The North American Indian (1907-1930), work from which is also on view. In this way, the show becomes a curatorial investigation into identity and assumptions, not only about human beings but also about the land itself.

IN CONVERSATION:

WILL WILSON through Feb. 12

Exhibition text reveals that Wilson traveled through Oklahoma in 2016. During this time he photographed many Pawnee people — outdoors, rather than indoors. In a portrait of William “Bill” H. Howell, the result is dappled sunlight, perhaps the shapes cast by trees, and the handle of a bicycle. The viewer may reflect on the relationship our culture has not

Mennello Museum of American Art 900 E. Princeton St. mennellomuseum.org

$5 arts@orlandoweekly.com

In Conversation is eloquent and sincere in its representation of an active rather than passive relationship between artist, curator and historical documenta. This traveling exhibition from Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas may be the best example of a show that fulfills the curator’s responsibility to the present, past and future simultaneously that I have seen in recent years. Bringing it to Orlando shows foresight and vision on the part of the Mennello, an institution that deeply benefits the citizens of Central Florida it serves.

BY SETH KUBERSKY

Nude Nite, once the city’s steamiest art show, returns this week with all the expected artwork au naturel and bodypainted performers. But this is also a daughter’s tribute to her mother

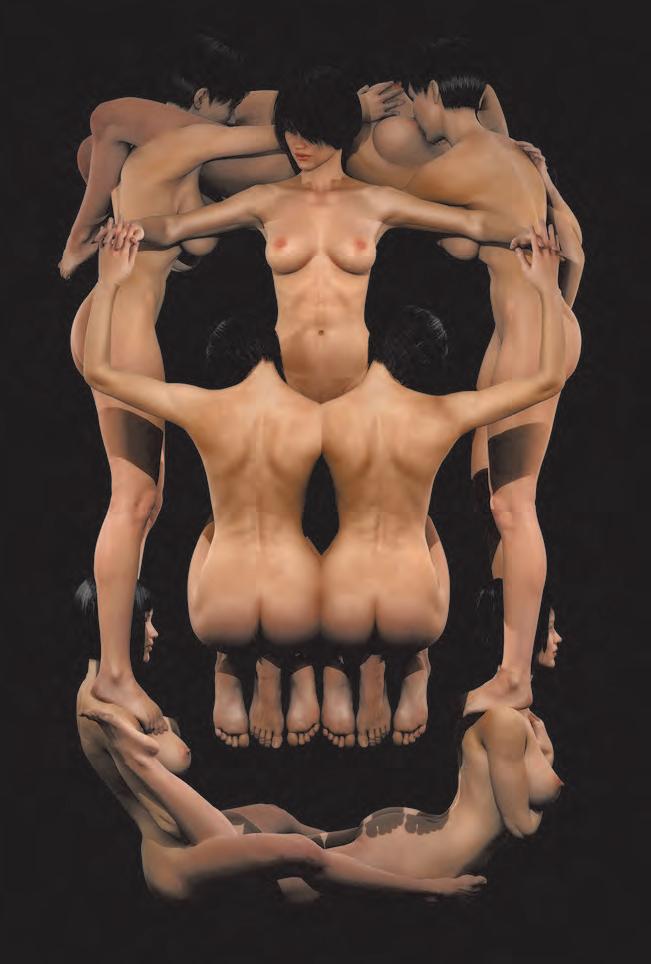

For more than 15 years, Orlando’s Nude Nite (nudenite.com) was the city’s steamiest annual art show, always packing its warehouse galleries full of eager oglers admiring au naturel artwork and body-painted performers. The popular party was put on pause after the 2020 edition because organizer Kelly Stevens passed away in 2021. Now, Stevens’ 23-year-old daughter Sloan Waranch has picked up the banner (with the blessings of her siblings) and rebooted Nude Nite in tribute to her mother. I spoke with Waranch ahead of Nude Nite’s return on Feb. 9-11 at the Canvas Event Venue, to hear how this year’s theme, “Prism,” reflects the journey she’s traveled coming to terms with her mom’s death.

Shortly after this column kicked off in early 2008, one of my first reviews was of Nude Nite, which was then crammed into Colonial Drive’s former Cameo Theater. Although my early hot take was quite cynical, critiquing the crowd flow and aesthetic quality, I grew to appreciate the event over the ensuing years, and I always found at least one provocative piece to admire. But it only feels like Nude Nite has been a part of my life forever; it quite literally has been for Waranch, whose earliest memories include “painting walls with her [Stevens], finding random stuff on the street that she would use for an art installation.”

Waranch recalls that Nude Nite grew out of her mother — whom she describes as a “Southern debutante, but also a total rebel at heart” — wanting to “give artists a space to bring their art that … wasn’t getting accepted into any other gallery,” and to “transform the idea of the gallery and create a whole experience that makes people think differently about themselves [and] about the world.”

An earlier version of Nude Nite ran from 1996 to 2002, created by promoter Victor

Perez. Stevens’ version started in 2005, and Waranch says, “I don’t even know who Victor is, to be honest; I just remember my mom putting the show together.”

Every Nude Nite is an adults-only celebration of the flesh, but Waranch hopes this year’s edition also has a spiritual side inspired by loss and healing. Prior to her mother’s passing, Waranch told her that she “wasn’t interested in [continuing Nude Nite]; it was my mom’s thing.” But weeks after Stevens’ death, she discovered her mom’s unpublished memoir, titled Prism, which provided the impetus and theme for Nude Nite’s revival. The mostly complete book is about “seeing your life through a different lens and embracing the changes of life. And the show is a lot about embracing who you are right now, but also being able to transform the way we think about our experiences — good or bad — and being able to embrace them and use them as our power.”

Waranch, who studied psychology at UCF and worked there on Title IX mental health, didn’t go small when mounting her firstever event. She credits her confidence to her mother, who “believed in everyone, I think, more than people believed in themselves.” Nude Nite’s new two-level venue near the Florida Mall includes an industrial indoor gallery along with an outdoor area, which will feature over 130 pieces of art, plus

Insta-worthy installations like an emotional baggage claim, a tunnel of lost love and a butterfly garden lounge. “It’s a lot of selfreflection, but also really fun things as well,” says Waranch, explaining that Nude Nite has “always been a mix of something fun and a little taboo, but everything there has a purpose behind it.”

While following in her mother’s footsteps, Waranch is still putting her own stamp on the event, particularly with the “statement of purpose” that everyone will read upon entering. “I can just hear my mom going, ‘You’ve got to do it your way,’” she says. “‘You’re gonna have to learn, and you’re gonna have to pivot a million times, and things aren’t gonna work out. But you’re gonna have to find a solution, and that’s why you’re doing this.’”

She’s also still finding her own way; when we spoke, she was “still trying to work on if there’s going to be full genitalia showing,” saying that decision would be a “last-minute kind of thing.”

Either way, she emphasizes that Nude Nite is ultimately not about being “erotic or more sexual … because it really is about the human body.

“There’s this thing that happens when you see people who are nude, and you’re stripped down of your job and how much you make. [The body is] the one thing we all share.” skubersky@orlandoweekly.com