5 minute read

“The world you’re about to see ain’t yours’

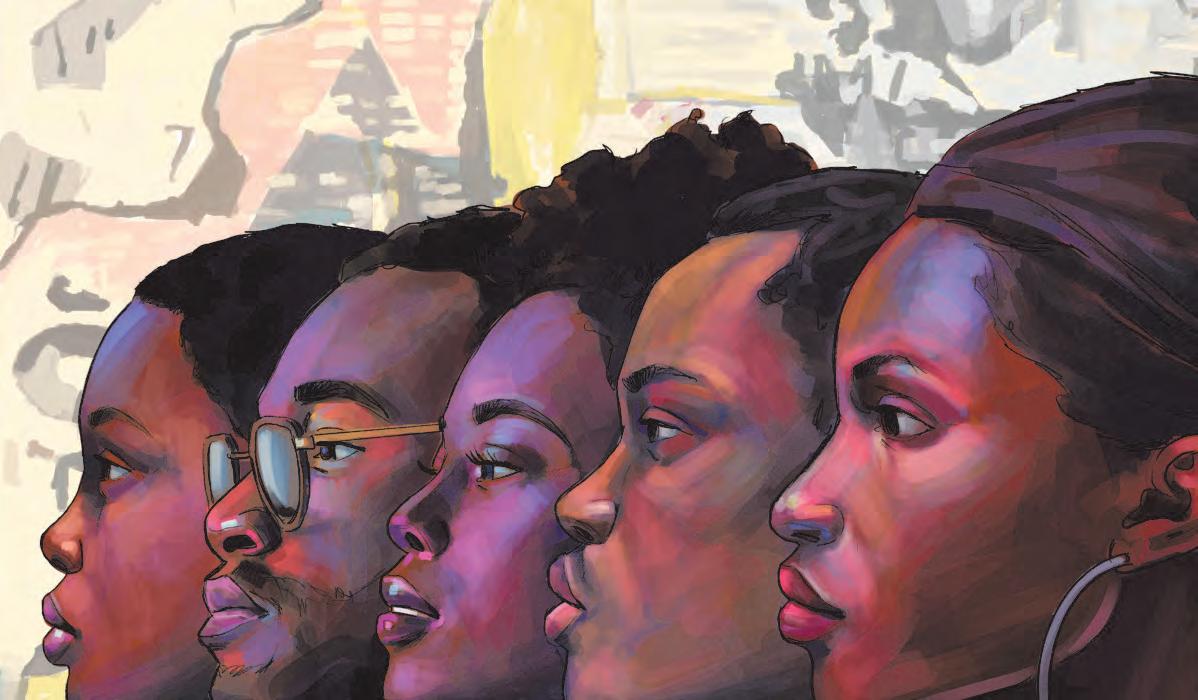

Apologies to Lorraine Hansberry (You Too, August Wilson) runs through Oct. 30 | Courtesy Image

Orlando Shakes stages Apologies to Lorraine Hansberry, parsing identity politics in a post-Trump, segregated United States

BY CAROLINE HULL

“The world you’re about to see ain’t yours.” In Apologies to Lorraine Hansberry (You Too, August Wilson), playwright Rachel Lynett envisions an alternate history, a world in which the election of Donald Trump triggered a second Civil War that split the United States. Against the background of this segregated, “historically inaccurate” world, a domestic drama plays out in a small community within an all-Black state as an Afro-Latinx person moves to town. Apologies to Lorraine Hansberry premiered at PlayFest 2020, so it seems like kismet that as PlayFest 2022 approaches, Apologies has returned to the Orlando Shakes’ stage as a fully staged production, running through Oct. 30. In the interim, Lynett’s original script won a Yale Drama Series Prize. Orlando Weekly caught up with Lynett for a talk about the layers embedded in the contemporary Black experience,

the power of “messy” women, and the necessity of “blistering honesty.”

Both the story told on stage in ‘Apologies to Lorraine Hansberry’ and the story of the play’s success in the world are incredibly inspiring.

For me, Apologies is about a playwright fighting with APOLOGIES TO LORRAINE HANSBERRY (YOU TOO, AUGUST WILSON) their characters. I wanted to answer the question: What is the Black experi-Through Oct. 30 ence? And as I was writing

Goldman Theater, Lowndes Shakespeare Center the play, I realized there 812 E. Rollins St. isn’t one answer and I’m orlandoshakes.org not the person to answer. I 407-447-1700 can give a piece of it but not $25-$57 all of it. And the message I wanted to send was it’s not monolithic. Yes, I’m Black but I’m also proudly Afro-Latine, proudly Belizean with a Mexican grandfather and a Honduran grandmother. There are layers to Blackness and we have to make room for all of it.

[ arts + culture ]

What do you hope the audience takes away from this?

My answer is frustrating: “something.” I hope the audience takes something away from the performance, but I don’t want to dictate what that is. That’s not my job. I want to write the kind of plays that people talk about days after they saw the play, but what those conversations are isn’t up to me. I think counter to how I was trained, I don’t believe in handing the audience a lesson or a theme. I’m even pulling back from dictating every line the actors say. If theater is a collaborative art, then the audience (and the performers) are part of that collaboration. You don’t tell your collaborators what to think, you trust that they’ll bring their piece to it.

What do initially inspired you to pursue playwriting?

I’m not sure I was inspired. It almost feels like I was pushed to it. Growing up, I didn’t realize there was a such thing as a “playwright.” All the playwrights we read about in school were dead and all the shows I saw at theaters were the same way (or they were musicals).

I wanted to be a lawyer. Then I got to college and kept changing my major as I was failing through classes. In my junior year I was a film major thinking I’d go into editing or criticism and I had to take a “fine art credit” which I thought was weird since my major was fine arts. I ended up taking a Script Analysis class that changed my life. Not only was it the only class I wasn’t failing, but our teacher also had an amazing syllabus. She’d assumed we read Beckett and Shakespeare already, so her syllabus was 70 percent women playwrights, 60 percent playwrights of color, 25 percent queer playwrights. … She said she wanted us to know theater was more than one thing. And it radically changed my opinion of theater. I switched my major the night after reading Cloud Nine by Caryl Churchill.

Even then, though, I wanted to be a stage manager, working my way up to eventually being an artistic director. As I was stage managing, I remember noticing the plays I read weren’t the plays I was seeing performed. Also, as good of a job as my teacher did, we didn’t read a lot of queer writers of color; it was one or the other. I remember asking, “Where are the Black queer playwrights?” And I was told there weren’t any.

That’s when I started writing. I told myself I’d write enough plays that no one else could ever say that again. I’ve written 36 now and have found a network of other queer playwrights of color.

I read your artist’s statement on your website, and it moved me — especially the quote “These women are neither saints nor villains; they’re eternally both.” I’d like to hear even more about your mission as a writer and what that means to you.

I love messy women on stage, on screen, in our stories. Too often “messy” means single with a drinking problem. And often that messy woman is white. I’m not discrediting that, but I’d like to expand how we see messy women. Black women are told our whole lives we have to carry the community on our back, be the defenders, the “strong Black woman.” What does that look like when you add ambition, to a world that wasn’t built for us? What compromises do we have to make? Whom do we have to leave behind to move forward?

In all of my plays, I write about women who make really hard and questionable decisions to have a better life. The American dream Willy Loman clutched onto was never built for us. We had to carve our way and that means making choices that sometimes work against what’s good for us. What do those stories look like? What’s at stake to get a piece of the dream?

arts@orlandowekly.com orlandoweekly.com ● OCT. 19-25, 2022 ● ORLANDO WEEKLY 21