7 minute read

FUTURE-SAHEL

The seeds of a resilient future for the Sahel

The Great Green Wall initiative was established to stop desertification of the Sahel, a zone of Northern Africa south of the Sahara. A deeper understanding of the complex social and ecological systems along the Great Green Wall path is a prerequisite to inform effective actions, a topic central to the work of the Future-Sahel project, as Dr Deborah Goffner explains.

The Sahel region marks the transition between the Sahara desert and Sudanian Savanna and spans the width of Northern Africa, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. The Sahel is increasingly vulnerable to desertification, with human activities and climate change contributing to land degradation. “The Sahel is undergoing major transitions. There are more people and livestock, so there is increasing pressure on natural resources,” says Dr Deborah Goffner. The Great Green Wall (GGW) initiative was established in 2007 to address concern about desertification through reforestation and other interventions, yet these must reflect the diversity of the Sahel if they are to be effective, a topic central to Dr Goffner’s work as Principal Investigator of the FutureSahel project. “There’s no one-size-fits-all solution,” she acknowledges.

Future-Sahel project

By building a deeper understanding of the social and ecological systems along the GGW, Dr Goffner and her colleagues in the project, including researchers from different disciplines and GGW decision makers, aim to help improve natural resource management in the Sahel. Historically the region was sparsely populated, with nomadic populations migrating in and out as a function of resource availability, but this began to change towards the end of the colonial

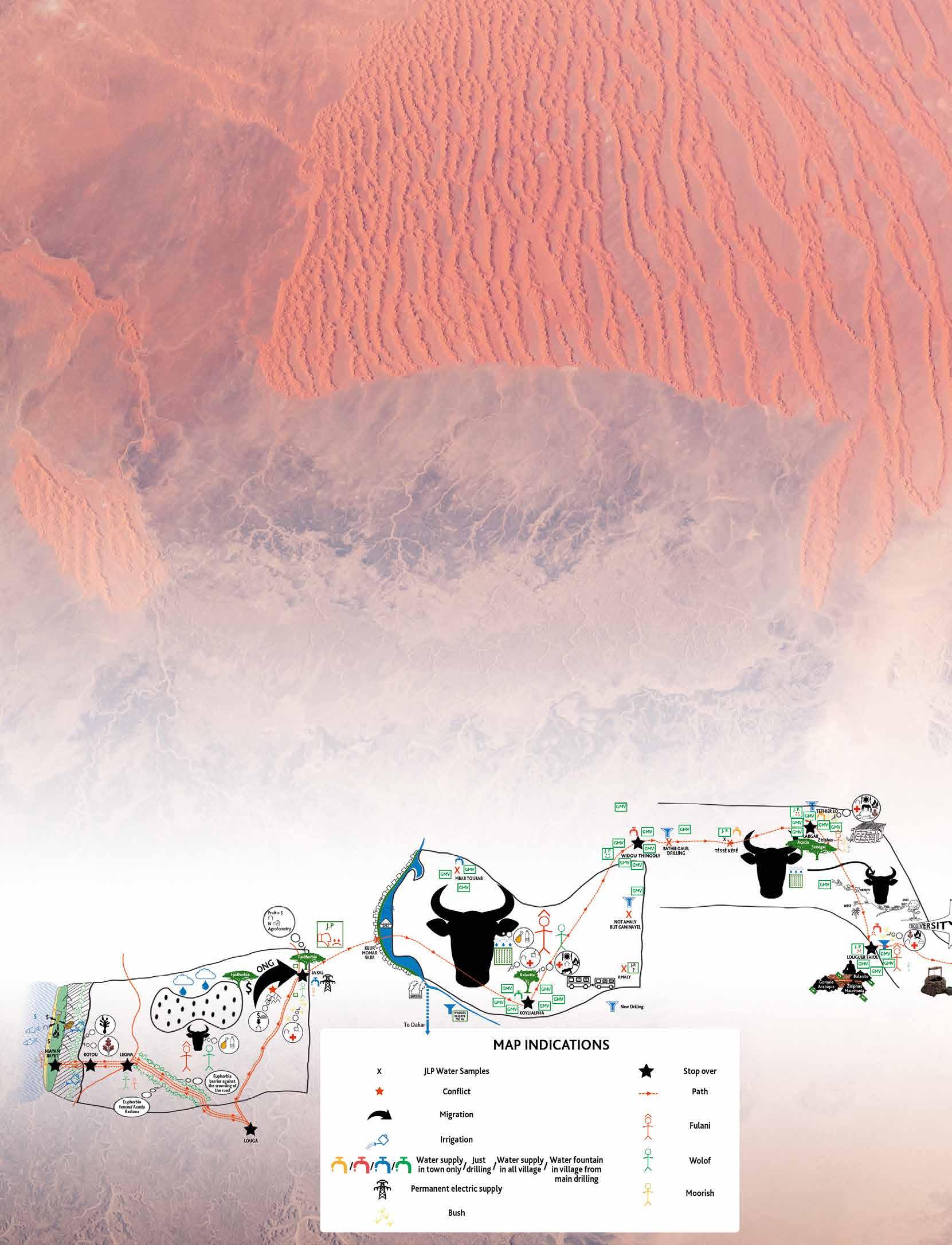

Social-ecological system diversity along the GGW path as depicted by a group of multidisciplinary Future Sahel researchers

period as authorities aimed to sedentarise herders by providing year-round water access. “This was a game-changer,” says Dr Goffner. Previously nomadic populations started to settle permanently into certain areas, heightening pressure on resources, which was intensified by subsequent droughts. “The drought of 1973 caused many fatalities and a lot of international aid was pumped in. We’ve traced the history of the region and looked into how Senegal dealt with these shocks. This gives invaluable insight into the region’s resilience in the past,” outlines Dr Goffner.

The primary focus is on understanding the current situation however, which will help researchers identify how resilience can be enhanced across the region. Populations in some areas may still depend on the forests for food, energy, construction, fodder and medicine, what researchers call ‘provisioning’ ecosystem sevices. “These can be thought of as the the benefits provided to humans by natural products,” says Dr Goffner. Dr Goffner has travelled across the Sahel, gathering data from different areas along the GGW. “What ecosystem services are available in different areas? What services are important?” she continues. “The main goal is to ensure that

We created a social-ecological database in which we have centralized geographically explicit ecological and social data for the GGW path. So now we can build layered maps, and bring together information on things like population density, land use, vegetation, and soil type in a specific area.

we can nudge the Wall actions in a way

that ensures abundant, durable delivery of ecosystem services.” . A wealth of relevant geo-spatialized data concerning the GGW path is also available from national archives, from which researchers have characterised the historical and current situation in different parts of the Sahel. “We created a social-ecological database in

Composite diagram recreated from original hand drawn maps made by Margaux Mauclaire

which we centralized geographically explicit ecological and social data for the GGW path. So now we can build layered maps, and bring together information on things like population density, land use, vegetation, and soil type in a specific area,” says Dr Goffner. This enables Dr Goffner to gain deeper insights into these different social-ecological systems and how different social and ecological parameters are interconnected. “Now we can characterise the current situation so areas can be restored in meaningful ways,” she says.

This social-ecological database provides the basis on which researchers can then look to assess what actions are suitable in which areas . One part of this work involves investigating how biodiversity can be maximised along the GGW. “We have been doing ethno-botanical research. We try to understand how people interact with plants, what they use them for and how they use them, what their daily routines are, and how dependent they are on different resources. We have focused on indigenous tree species. From this data, we have identified a shortlist of trees that we tested in reforestation trials, to determine which species can reasonably be planted at a large scale in different areas along the GGW path,” explains Dr Goffner. A number of field trials have been held, while researchers are also studying the impact of deferred grazing on woody regeneration. “We study the reforested trees, but also natural regeneration occurring in the enclosed plots. In some areas, natural regeneration produces greater amounts of biomass than the planted trees, which have low survival rates,”says Dr Goffner.

Wayfinder platform

The wider aim here is to help enhance the resilience of the region overall and provide a basis for more effective management of natural resources. The Wayfinder platform, a tool developed by the Stockholm Resilience Centre together with the Resilience Alliance and the Australian Resilience Centre, plays a central role in this work.

“We piloted the Wayfinder process in the project in the heart of the Ferlo UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve,” says Dr Goffner. The platform is designed to reflect the complexity of social-ecological systems in a multi-stakeholder, participatory manner. “The Wayfinder platform is essentially a process that facilitates the navigation towards a desirable future,” outlines Dr Goffner. “For example, actions like apiculture, natural regeneration and tree planting are all embedded in the social context, and it’s absolutely essential to take that into account. Throughout the process, we need to constantly examine whether an action is taking us closer to a desired future.”

The trans-disciplinary nature of the project is an important attribute, as it brings together researchers from different disciplines to develop a broader perspective, including biologists, ecologists, geographers and social scientists. Dr Goffner and her colleagues also work with local people, such as high-level administrators, foresters, youth groups and herders, who all play an important role. “We essentially coreflect upon, co-produce and co-construct the project,” she says. By working together with local stakeholders , Dr Goffner hopes to help point the way towards a more sustainable future for the Sahel. “Instead of starting out by talking about the problems, we spoke about aspirations. What does a positive future look like? What are the obstacles? What actions can we take to address them?” she outlines.

International cooperation is essential to address the major issues around climate change in vulnerable regions like the Sahel, yet individual actions can have a positive impact on the local level. Local stakeholders of course have diverse viewpoints when it comes to the future, yet Dr Goffner is clear that equitable access to ecosystem services should be at the heart of any future natural resource management strategy. “No matter what vision of the future we decide upon and navigate towards, ensuring equitable access to ecosystem services will be central to it,” she stresses.

FUTURE-SAHEL Multi-scale approaches for best resource management practices of Sahelian landscapes in the Great Green Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative context Project Objectives

Our aim is to produce scientific data to “nudge” the African Great Green Wall (GGW) along a positive trajectory. We gather, generate, and integrate knowledge from a wide range of disciplines, while taking into account the complexity of diversity of the socio-ecological systems along the GGW path. We then use this knowledge to inform GGW natural resource management in Senegal. The latter is made possible by the transdisciplinary nature of the project, i.e. incorporating the Senegalese National GGW agency in charge of GGW decision- making and implementation as partners of Future Sahel.

Project Funding

Agence National de la Recherche France (Future-Sahel ANR15-CE03-0001)

Project Partners

• International CNRS Research Unit n° 3189 “Environment, Health and Societies” (Senegal/France) -Deborah Goffner (coordinator), Jean-Luc Peiry, Aliou Guissé • Stockholm University, Stockholm Resilience Centre (Sweden) -Line Gordon • Senegalese National Great Green Wall Agency (Senegal) - Papa Sarr

Contact Details

Project Coordinator, Deborah Goffner International CNRS Research Unit n° 3189 “Environment, Health and Societies” 51, Bd Pierre Dramard - 13344 Marseille cedex 15, France T: +33 6889 69544 E: deborah.goffner@cnrs.fr W: http://future-sahel.blogspot.com

Deborah Goffner

Deborah Goffner is a plant biologist and research director for the CNRS (Centre National de Recherche Scientifique), France. Currently based half-time in Dakar, Senegal and half-time as a visiting senior scientist at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, Sweden, she heads a research group at the UMI (International Research Unit) 3189 “Environment, Health, and Societies”. She coordinated the Future Sahel program funded by the French National Research Agency (ANR) from 2016-2019.