The seeds of a resilient future for the Sahel The Great Green Wall initiative was established to stop desertification of the Sahel, a zone of Northern Africa south of the Sahara. A deeper understanding of the complex social and ecological systems along the Great Green Wall path is a prerequisite to inform effective actions, a topic central to the work of the Future-Sahel project, as Dr Deborah Goffner explains. The Sahel region marks the transition between the Sahara desert and Sudanian Savanna and spans the width of Northern Africa, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. The Sahel is increasingly vulnerable to desertification, with human activities and climate change contributing to land degradation. “The Sahel is undergoing major transitions. There are more people and livestock, so there is increasing pressure on natural resources,” says Dr Deborah Goffner. The Great Green Wall (GGW) initiative was established in 2007 to address concern about desertification through reforestation and other interventions, yet these must reflect the diversity of the Sahel if they are to be effective, a topic central to Dr Goffner’s work as Principal Investigator of the FutureSahel project. “There’s no one-size-fits-all solution,” she acknowledges.

Future-Sahel project By building a deeper understanding of the social and ecological systems along the GGW, Dr Goffner and her colleagues in the project, including researchers from different disciplines and GGW decision makers, aim to help improve natural resource management in the Sahel. Historically the region was sparsely populated, with nomadic populations migrating in and out as a function of resource availability, but this began to change towards the end of the colonial

period as authorities aimed to sedentarise herders by providing year-round water access. “This was a game-changer,” says Dr Goffner. Previously nomadic populations started to settle permanently into certain areas, heightening pressure on resources, which was intensified by subsequent droughts. “The drought of 1973 caused many fatalities and a lot of international aid was pumped in. We’ve

ecosystem sevices. “These can be thought of as the the benefits provided to humans by natural products,” says Dr Goffner. Dr Goffner has travelled across the Sahel, gathering data from different areas along the GGW. “What ecosystem services are available in different areas? What services are important?” she continues. “The main goal is to ensure that we can nudge the Wall actions in a way

We created a social-ecological database in which we have centralized geographically explicit ecological and social data for the GGW path. So now we can build layered maps, and bring together information on things like population density, land use, vegetation, and soil type in a specific area. traced the history of the region and looked into how Senegal dealt with these shocks. This gives invaluable insight into the region’s resilience in the past,” outlines Dr Goffner. The primary focus is on understanding the current situation however, which will help researchers identify how resilience can be enhanced across the region. Populations in some areas may still depend on the forests for food, energy, construction, fodder and medicine, what researchers call ‘provisioning’

that ensures abundant, durable delivery of ecosystem services.” . A wealth of relevant geo-spatialized data concerning the GGW path is also available from national archives, from which researchers have characterised the historical and current situation in different parts of the Sahel. “We created a social-ecological database in

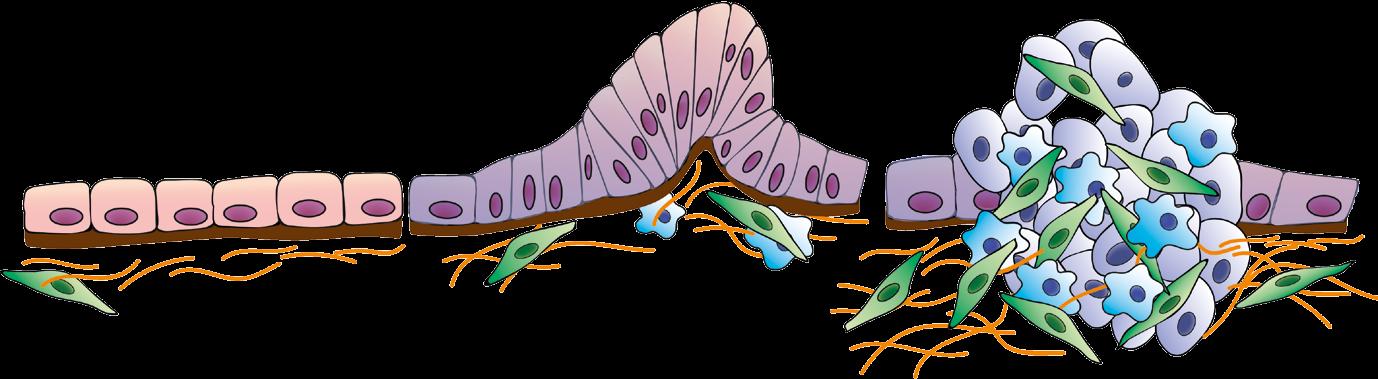

Social-ecological system diversity along the GGW path as depicted by a group of multidisciplinary Future Sahel researchers

Composite diagram recreated from original hand drawn maps made by Margaux Mauclaire

40

EU Research