40 minute read

Conclusion

In What Way? And After?

In What Way? — Co-evaluation

Advertisement

The Europan 16 Juries Discuss Evaluation Criteria

On the occasion of the Forum of Cities and Juries in San Sebastián (ES) on November 5, 2021, members of the 9 Europan 16 national juries met to discuss the culture they can share on the projects submitted on the 40 sites proposed to the session on the theme: Living Cities. They exchanged on the criteria they can share on the two thematic axes of the session: the metabolic approach and the inclusive dimension of the projects. This article relates their views and exchanges.

1 — METABOLISM

AGLAÉE DEGROS, EUROPAN SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE

MEMBER — For this Europan 16 competition the city is not considered as a machine, but as an organism with its own ecology made of human and non-human actors, an organism that is sensitive to climate (flood, avalanche, desertification…) and based on interconnections. Considering the experts involved in the co-evaluation of projects with the 9 Europan national juries, which are identical in their organisation, yet different in culture and skills —What criteria, but also what speech, can they share in the way they study the projects?

CLARA LOUKKAL, LANDSCAPER, FRENCH JURY —

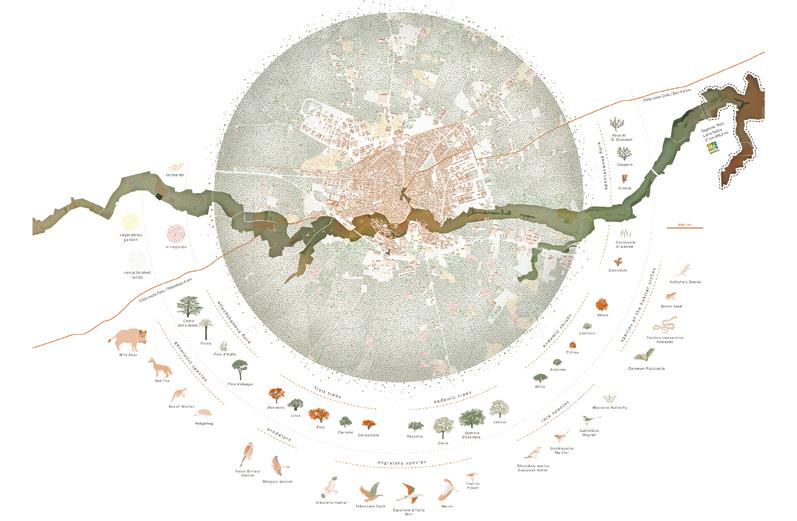

Three criteria can be shared to assess the relevance of new project themes and which also resonate with the general theme of Living Cities. Good metabolic projects integrate the interrelationships that are already existing on a site, that is, not only the buildings or the open public space, but also the interrelationships that are taking place within the site: between the various users but also between all the productions, the emissions, the energy consumption, etc. Another criterion to identify metabolic projects is that they are designed as experimental processes, based on observation and on the setting up of pilot projects and prototypes. Finally, these projects work on different scales of time and space simultaneously. They can have an impact in the very short-term, because they set up observation and experimentation processes and at the same time, they can plan these processes in the very long-term to reintegrate them into the city. It is about considering the infinitely small as well as the very large. There is a whole series of projects in this sixteenth session that are interested in non-human actors for example and which, at the same time, consider large territories and all the scales that exist between the two. A good example of this approach is the LABO RABO project on the Grenoble site in the French Alps. It is located in a basin between three mountain ranges and is regularly affected by very hot climatic events and pollution peaks. The project proposes to create a laboratory for the acclimatisation of new plants, which will be tested on the rocky spur and then gradually integrated into the city (fig.1). The project talks about cycles, recycling of materials, reuse of existing buildings… The project pays a very detailed attention to everything that exists on site and to the evolution the project could follow.

CARLES ENRICH, ARCHITECT, SPANISH JURY — The question of interscalarity is a very important criterion. For example, the Open Horizons project in Roquetas de Mar (ES) develops on three parallel scales, while keeping a transcalar vision. At the territorial level, it integrates a temporal dimension that anticipates processes

2 — Roquetas de Mar (ES), special mention — Open Horizons > See more P.143

that could develop over 30, 40, 50 years. This includes the geological, time and territorial scales, but also a metabolic level with the idea of the water cycle (fig.2). The project then locates some project opportunity spaces in the interfaces between the city and the agricultural fields. Some spaces are left somewhat undefined, but at the same time the project raises questions about their potential connections with the development of the whole city. These are project spaces on which a water management system is proposed to recover rainwater and therefore improve the relationship with the subsoil while at the same time guaranteeing an exchange interface between the city and the fields. The project identifies potentials areas where the interactions can take place. The city boundaries are more porous with the fields, which makes it possible to propose the construction of more compact housing in order to avoid destroying boundaries and fragmenting the city within the territory. Proposing compact buildings makes it possible to maintain the areas as a space of opportunity and of geological and natural exchange.

THORSTEN ERL, ARCHITECT, GERMAN JURY — The young generation has understood the ecological requirements of the city as a design element. In Schwäbisch Gmünd (DE) the project RISE (Resilient, Innovative, Social and Energetic) proposes the extension of a river floodplain as a design element (fig.3). The project also has a technical, programmatic focus by getting greywater and rainwater into the new development. A new water tower is designed with water reservoirs for greywater and rainwater, which supplies not only the entire district, but also the main open spaces at the city entrance, that acts as a gathering point for a railroad, a road, a river, and a mountain skyline. This transverse direction from the mountain to the river, this perforation of the urban configuration is central in the project to create areas of separation and collective gathering, but also in a social, inclusive dimension to design different housing typologies implemented by cooperatives. And in this project, as in many others, the absence of cars in a residential area is an important point in terms of inclusion, as the public space becomes more adaptable.

BENOÎT MORITZ, EUROPAN BELGIQUE SECRETARY,

BELGIAN JURY — Some of the projects in this session consider metabolism at different scales, starting from the building itself and its qualities of renovation, as well as of integration of construction waste flows and of potential production flows, therefore addressing the issue of the productive city. It is the case in Brussels (BE) with the project Architecture Centre for Regenerative Materials, which proposes the conversion of an architectural centre on a linear street and with underground surfaces. The project starts from the underground surfaces where a centre called the Centre for Regenerative Materials is to be created;

3 — Schwäbisch Gmünd (DE), special mention — RISE > See more P.159

it would host a fungus production that, through a fermentation process, would allow building thermal insulation panels (fig.4). But the Centre would also process a second type of stream, and construction waste would be processed in order to produce the thermal insulation panels. The building itself would become a demonstration site to show the renovation process and train a vulnerable population in sustainable construction. Finally, it would be a place of information on the challenges of transforming existing buildings.

THORSTEN ERL — The hybrid use of a building is indeed a criterion. Hybridty can mean combining technical elements, but also social dimensions that come together. In the water tower mentioned on the Schwäbisch Gmünd site, there is also the idea of a meeting place for citizens with a café on the rooftop and offices inside. It is important to make it clear to developers that the hybrid use of a building is important and that they then need committees, groups of people, of actors to manage different uses under one roof (fig.5). And this is when the juries have to pay attention to the post-competition processes and support the clients to implement these ideas of functional hybridity. CLARA LOUKKAL — These projects bring out new themes to which we are supposed to respond as architects, landscape architects and urban planners, but we cannot master them all and be a specialist in everything: recycling, biodiversity, architecture… The projects are qualitative in the way they show how the interrelationships between the elements have an impact on the city and on our way of building today. In the Grenoble project, the way they transform certain ideas of the project into short-term pilot actions is a way of immediately bringing these questions to the scale of the project (fig.6).

BENOÎT MORITZ — How can an archive centre become a living place? It is rather this ambition that the jury was interested in, that shows how different functions can form a system inside a building (fig.7) and also be interesting for the whole city, especially on the issue of construction waste management. The question of a jury’s choice in relation to a potential implementation consists of taking a rather strong position and saying that this public infrastructure must remain 100% public; a message to the client that will be there for the implementation.

5 — Schwäbisch Gmünd (DE), special mention — RISE > See more P.159 7 — Brussels (BE), winner — Architecture Centre for Regenerative Materials > See more P.197

CARLES ENRICH — There are different levels of project implementation. There are projects with a more defined, more concrete scale, as is the case with the Brussels building, which allows for systematisation, for programming in case the building is implemented; it is much easier than the case of the Roquetas de Mar project, which proposes a strategy to open up a debate (fig.8). Because it is a project developed on a large time scale and the implementation is rather a planning project inviting multidisciplinary work with geologists, landscape architects, topographers, etc. And it is good that Europan allows these two visions to coexist: a territorial vision with a landscape scale and planning in time, and a more concrete vision with projects that are easier to implement in the short-term.

CLARA LOUKKAL — I think that a good metabolic project is not only a project that sets out all these questions of cycles and scales in a theoretical way —from the insect to the large territory. What some teams are trying to show is, for example, how all these elements have an impact on the territories. Today, many projects propose to reuse specific waste or to create methanisation plants; some energy projects for example allow for a more virtuous and cyclical energy for certain buildings. But the whole question is to show —and the good projects indeed do this— how these new infrastructures have an impact on the territory, how they are going to be built, where they are settled, whether they respect the topography, what it changes in the city… These are both architectural and territorial projects which directly impact our way of doing things. And I think that a good project for Europan 16 is a project that manages to make the connection between these questions of cycles and their concrete impacts on our territories.

BENOÎT MORITZ — Is there a new form of space connected to an architecture form that considers some aspects of metabolism? This is still but a question, but there is a different aesthetic quality that is appearing, which is much more connected to a form of aesthetic of the ecological transition with the idea of working on the materials recovery while actually making architecture. So, this also leads to new architectural expressions, to a new language. The jury preferred projects that make sense —and also have some aesthetic quality— compared to the idea of recovering a building and working on the flows or even producing new elements.

TINA SAABY, URBANIST, SWEDISH JURY — The second concept identified by Europan 16 is inclusivity. To talk about inclusivity, we need to design projects that work as an invitation, like the Vitality! project in Västerås (SE) that tackles the question of transformation of a former industrial area (fig.9). The project is clear in the way to communicate on the making process. The team explains what is going on not only to the jury but also to the people that will be involved later on: the way they work on uses, jobs, transversal activities while connecting with the theme of Living Cities. The project is also an invitation to work with the knowledge linked to a global network, a global knowledge that they give to the people that will be involved in the process. The project works on inclusivity in terms of communication, of activities, of transversality, of comprehension, and of sharing knowledge, with an open human scale and a very good design. As jury members, how do we use the thematical foundation of the competition? For me, being a good Europan jury member is first to understand the client and the city, especially because they are not part of the jury, and try to listen and understand what the projects’ dreams are. Then of course try to share what is good architecture. The thematical foundation is very important in this forum, because we have guidelines to study all the projects and a way to discuss them and see if there is a general tendency. And I think the theme is also important for young architects because it can be inspiring before starting the project.

BENNI EDER, ARCHITECT, AUSTRIAN JURY — Another criterion for assessing the inclusivity of projects is the consideration of the site history. As in the Free Mühlgang project in Graz (AT) where the historical dimension is very important. On the strategic site, occupied by a shopping mall, the urban river —the Mühlgang River— is reduced to its infrastructural dimension. The project designers investigated the history of this green and blue infrastructure and argued that there are very inclusive traces and historical events, although they were lost. In a quite poetic and narrative way, they develop the project on the potential of water and green that can once again become inclusive elements. The project work on two scales articulating the reconversion of this large-scale green and blue infrastructure with the scale of a permeable building —a platform as a statement for inclusive architecture (fig.10). On top of this territorial and object scales, there is also the programmatic level, which relates to the context history, just like

10 — Graz (AT), runner-up — Free Mühlgang > See more P.133

11 — Risøy (NO), special mention — Life in All its Settings > See more P.59

archiving, identifying things that are forgotten and not represented anymore in terms of social and human interest —the education level, the legal existence and also the physical body.

NINA LUNDVALL, ARCHITECT, NORWEGIAN JURY —

Inclusive design means “being generous”. This debate on inclusivity coincides with the Cop26. At this stage of the competition we have to see the projects for their ideas and not as finish projects. It is at this stage of ideas that we can talk about inclusivity and diversity. For example, the project Life in all its settings à Risøy (NO) shows both a deep understanding of the site as well as social awareness. It is an island with small-scale housing directly next to large-scale ferries and shipyards. This project understands that the identity of the place lies in the relationship between both scales, but that in terms of inclusivity and accessibility, the residential district and the public space are cut off from the edge of the island, which is privatised. Their vision is to make the island more communal, more accessible and less privatised by proposing green interventions that highlight the different qualities of the island (fig.11).

SOCRATES STRATIS, EUROPAN SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE

MEMBER — What kind of impacts do the proposals have on large territories (and not only on project sites)? What kind of multi-planning effects can they have? How to understand that small strategic interventions do not only fall under the discipline of architecture anymore, but play a role at the territorial scale? Is it the entanglement of all these scales that we have to champion? How to intervene with small changes that have an impact on natural elements such as restoring rainwater flows or thinking about the energy system? We need design tools that do not depend on just one discipline in order to discuss this creative entanglement of scales.

AGLAÉE DEGROS — Some of you have mentioned that the public space is an interface to inclusivity. Can’t we just say that the public space is the place of inclusivity?

VITTORIO BRIGNARDELLO, DIRECTOR OF THE TERRITORIAL PLANNING DEPARTMENT, CITY OF VERBANIA (IT), ITALIAN JURY — The interest of Europan is that even though we, as urban managers, know our city quite well, young international architects will look at it with fresh eyes. And when the items of a situation and a project are so complex, the public space is the main focus to achieve inclusivity. There are three levels: the social and jobs level, the common vision of life connected to the public space, and the private space, the landscape. Working on these three levels at the same time is not easy. The public space is the ultimate level where the other elements can meet —the landscape, work, and the social and private spaces. It is what the

project Learning from the Lama in Bitonto (IT) tries to achieve (fig.12). The project works on 4 elements: — An urban green continuity with the Lama Balice regional park, that penetrates inside the different cities; — Water management of the Lama Balice and a better management of the rainwater in the city and valley. This is the ecological view of the project; — Management of the agriculture production chain to guarantee biodiversity agriculture and develop agricultural service. This is important for the jobs and for social inclusivity; — Development of rural tourism with the implementation of paths around cities.

NINA LUNDVALL — In the project Life in all its Settings in Risøy (NO), the focus is on the public space (fig.13). The city doesn’t want housing proposals. But of course, inclusive design is not only about every social level, every sex, ability or background; it is also about every kind of space, which can be private, commercial or public. In the project there is a real consideration of time: going back in time, looking at history, considering the existing. But we have to admit that projects like this one take a long time to implement and it includes a lap time that can be used to discuss with all the stakeholders.

CARLES ENRICH — I believe that the public space is the most metabolically sensitive part of the urban environment. Because cities need public spaces “without a program”, public spaces to keep as a space reserve for the future. In Barcelona for example, we are studying the Barceloneta district and we know that with climate change, in the next 30 years, we will lose 70% of the beach due to the rise in sea level. The beach is going to retreat and the public spaces that are in the second line behind the current beach will become the next beach in 20-30 years. That is why public space is sensitive to metabolism and it is interesting to set up this working line, the limits of these reserve public spaces. It is not so much the design or the program that is important, but rather this more metabolic idea of integrating the spaces with a life cycle, which allow for change and adaptation to climate change, and trying to introduce these movements, this dynamic into the cities. It is not a question of over-designing the spaces but of creating public spaces without programs to deal with the climatic conditions, the water cycles, etc.

CLARA LOUKKAL — There is a pitfall to avoid today in terms of public space, which is precisely “over-programming”. There is a drive towards greater versatility, because we realise that the public spaces that are constantly being redesigned are those that were originally programmed for specific uses that very quickly became obsolete, that changed and evolved. I believe that we would gain a lot in terms of public space resilience if we left the door open to uses that we do not yet know.

AGLAÉE DEGROS — When defining the theme, we tried to combine metabolism with inclusivity. Wouldn’t it be risky if the transformation of these public spaces did not reach the people we want to reach? Because there is often a kind of gentrification related to the transformation of the public space. This is an open question for all the projects that really focus on public space as a place of inclusivity.

BENNI EDER — In the context of the Graz site, it is not just about public space. The project site is located on a private property, but there is also the Mühlgang River, this urban infrastructure between public and private space (fig.14). And the team did a nice selection of criteria (accessibility, porosity, connectivity…) that in a way describes their approach and is not limited to the public space only. It is more about the definition of the space quality than a problem of public and private space.

13 — Risøy (NO), special mention — Life in All its Settings > See more P.59

NINA LUNDVALL — In the Norwegian jury, we had a really interesting and heated discussion about the site in Risøy with one project in particular, which one member considered as “too complete”. How much do you have to do to develop a place, to change a place? Does this change always have to be physical? Because the beauty and the identity of a place are not just about making it all green. There is something viable in the hard edge of this industrial place for example. The challenge of a project is to balance or negotiate the existing values with the need for change while still preserving the identity.

THORSTEN ERL — And as we are considering inclusivity, we also have to consider the opposite. What are the elements of exclusion in a site? There are special elements like fences or boundaries that contribute to this as well as programmatic elements like privatisation of spaces. So, we have to analyse these negative aspects of exclusion to find new criteria for inclusion.

AGLAÉE DEGROS — The process of Europan juries have been explained as a sort of negotiation on the projects between what the clients want and the competition theme, which is expressed in the ideas carried by the projects. And for this session, the theme of Living Cities induces a certain shift from the client perspective, especially public clients who are the vast majority. We mentioned a masterclass with clients to develop their viewpoints and some projects go as far as already reconsidering the program itself. It is the task of the jury to question that and Europan must be a pilot in this shift.

E16 juries Presentation

BELGIQUE / BELGIË / BELGIEN DEUTSCHLAND

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL ORDER

Valérie Depaye (BE) — Director ERIGES (Régie Communale Autonome de Seraing) (BE) – ERIGES Hardwin Dewever (BE) — Director of the Urban Renewal Projects division at Municipal company AG Vespa, Antwerpen (BE) – ag vespa Nel Vandevanet (BE) — Project Director of the Architectural and artistic heritage department, City of Brussels (BE)

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Carlos Arroyo (ES) — Architect, urbanist, teacher, Carlos Arroyo Architects, Madrid (ES) – www.carlosarroyo.net Lisa De Visscher (BE) — Architect, Head redactor of A+ Architecture, Brussels (BE) – A+ Architecture www.a-plus.be

Pol Esteve (ES) — Architect, GOIG office, London (UK) & Madrid (ES) Laura Falcone (IT) — Architect, 2D4, Napoli (IT) – E11 Winner www.2d4.eu

Philippe Rahm (CH) — Architect, Philippe Rham Architects, Paris (FR) – www.philipperahm.com

PUBLIC FIGURE

Eric Corijn (BE) — Cultural philosopher and social scientist, Director of the Brussels Academy (BE) URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL ORDER

Saskia Hebert (DE) — Architect, subsolar* architektur & stadtforschung, Berlin (DE) – www.subsolar.net Timo Munzinger (DE) — Doctor, German Association of Cities – www.staedtetag.de/english Iris Reuther (DE) — Doctor, Professsor, Senate Building Director of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (DE)

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Thorsten Erl (DE) — Doctor, professor, architect, Metris Architekten + Stadtplaner, Heidelberg (DE) www.metris-architekten.de

Kyung-Ae Kim-Nalleweg (DE) — Architect, Kim Nalleberg architects, Berlin (DE) – www.kimnalleweg.com Anna Popelka (AT) — Architect, PPAG architects, Vienna (AT) www.ppag.at Ali Saad (DE) — Architect, Bureau Ruiz Saad — Architecture Urbanism Research, Berlin (DE) – www.ruizsaad.de Marika Schmidt (DE) — Architect, MRSCHMIDT Architekten, Berlin (DE) – www.marikaschmidt.de

PUBLIC FIGURE

Kaye Geipel (DE) — Architectural critic, Deputy Editor-in-chief Bauwelt, Berlin (DE) – www.bauwelt.de

SUBSTITUTE

Dr. Irene Wiese-von Ofen (DE) — Architect, Board of Directors Europan Deutschland

ESPAÑA FRANCE

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL ORDER

Iñaqui Carnicero (ES) — General Director of Urban Agenda and Architecture, Ministry of Transports, Mobility and Urban Agenda (ES) – Europan España President Niek Hazendonk (NL) — Landscape Architect, Den Haag (NL) Rocío Peña (ES) — Architect, estudio peña ganchegui, San Sebastian (ES) – www.ganchegui.com

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Mariona Benedito (ES) — Architect, landscape architect, teacher, MIM-Arquitectes, Barcelona (ES) – www.mim-a.com Tina Gregoric (SL) — Architect, Dekleva Gregoric Architects, Ljubljana (SL) – www.dekleva-gregoric.com Enrique Krahe (ES) — Architect, Enrique Krahe architecture species, Madrid (ES) / Delft (NL) – Former Europan winner in Spain – www.enriquekrahe.com Eva Luque (ES) — Architect, elap arquitectos ingenieros slp, teacher, Almería (ES) – www.elap.es Arantza Ozaeta (ES) — Architect, tallerde2, Madrid (ES) – Former Europan winner in Spain – www.tallerde2.com

PUBLIC FIGURE

Socrates Stratis (CY) — Architect, urbanist, Associate Professor at the University of Cyprus, Nicosia (CY) – www.socratesstratis.com URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL ORDER

Nicolas Binet (FR) — Consultant urban renewal, housing, planning, Marseille (FR) – www.linkedin.com/Nicolas Binet Jean-Baptiste Butlen (FR) — Chief Engineer of bridges, water and forests, Deputy Director of the DGALN, DHUP, Paris (FR) www.ecologie.gouv.fr Sophie Rosso (FR) — Deputy Director of REDMAN immobilier, Paris (FR) – www.redman.fr

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Sophie Delhay (FR) — Architect, Paris (FR) www.sophie-delhay-architecte.fr André Kempe (NL) — Architect, Atelier Kempe Thill, Rotterdam (NL) – www.atelierkempethill.com Sonia Lavadinho (CH) — Urbanist, anthropologist, blfuid, Genève (CH) – www.bfluid.com Clara Loukkal (FR) — Landscape architect and urbanist, altitude 35, Saint-Denis (FR) – www.altitude35.com Caterina Tiazzoldi (IT) — Architect, designer, Turin (IT) www.archinect.com/tiazzoldi

PUBLIC FIGURE

Francis Rambert (FR) — Director of the architectural creation, Cité de l’architeture & du patrimoine, Paris (FR) www.citedelarchitecture.fr

SUBSTITUTE

Carles Enrich (ES) — Architect, Barcelona (ES) – Former Europan winner E12, E13, E14, E15 – www.carlesenrich.com SUBSTITUTES

Fabienne Boudon (FR) — Architect and urbanist, teacher, co-founder of Particules, Paris/Berlin (FR/DE) www.particule-s.eu Vincent Josso (FR) — Polytechnic engineer, urbanist, co-founder of Le Sens de la Ville, Paris (FR) www.lesensdelaville.com

ITALIA

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL ORDER

Vittorio Brignardello (IT) — Director of the Territorial Planning Department, City of Verbania (IT) www.comune.verbania.it

Giovanni Squitieri (IT) — Coordinator of the Presidential Committee of the Sustainable Development Foundation, Roma (IT) – www.fondazionesvilupposostenibile.org

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Jordi Bellmunt (ES) — Architect, landscape and public space design, B2B, Barcelona (ES) – www.b2barq.com Christine Dalnoky (FR) — Landscape architect, educator and researcher, L’Isle sur la Sorgue (FR) Edoardo Milesi (IT) — Architect, Archos, Montalcino (IT) www.archos.it

Guendalina Salimei (IT) — Architect, T-Studio, associate professor at the Faculty of Architecture of the Sapienza – University of Roma (IT) – www.tstudio.net

PUBLIC FIGURE

Maurizio Carta (IT) — Urban planner, architect, full professor of urban planning at the Department of Architecture – University of Palermo (IT) – www1.unipa.it/maurizio.carta

SUBSTITUTES

Simona Ferrari (IT) — Architect, scientific assistant ETHZ, Zurich (CH) – E15 winner in Verbania (IT) www.landscapeinbetween.com Caterina Rigo (IT) — Architect, PhD student and research fellow on strategies design issues for the revitalization of territories at UnivPM, Ancona (IT) – E15 special mention in Laterza (IT)

NORGE

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL ORDER

Berit Skarholt (NO) — Architect, Deputy Director in the Department for Planning, Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation (KMD) Aga Skorupka (PL) — Professor, social psychologist, head of social science at Rodeo Architects, Oslo (NO) www.rodeo-arkitekter.no

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Henri Bava (FR) — Landscape architect, TER office, chairman of the Landscape Architecture Department at K.I.T., Paris (FR) www.agenceter.com Nina Lundvall (SE) — Architect, Caruso St John Architects associate director, London (UK) – www.carusostjohn.com Sabine Müller (DE) — Architect, Principal at SMAQ Architecture Urbanism and Research, Berlin (DE), Professor at Oslo School of Architecture, Oslo (NO) – SMAQ Architecture Urbanism and Research

Øystein Rø (NO) — Architect and founding partner, Transborders studio, Oslo (NO) www.transborderstudio.com

PUBLIC FIGURE

Wenche Dramstad (NO) — Researcher at NIBIO, Head of Research in the Landscape Monitoring Department www.nibio.no

SUBSTITUTES

Gro Bonesmo (NO) — Architect, Professor and co-founder of Space group, Oslo – www.spacegroup.no Merete Gunnes (NO) — Landscape architect, Founder and director of Landscape design at TAG- arkitekter in Bergen (NO) https://www.tagarkitekter.no/ Linn Runeson (SE) — Architect, urbanist, managing director at edit AS – www.edit.land

Joakim Skajaa (NO) — Architect, founder of SKAJAA Arkitektkontor, curator of contemporary architecture at the National Museum, Oslo (NO) – www.skajaa.com

ÖSTERREICH

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL ORDER

Andreas Hofer (CH) — Architect, director of IBA‘27, Stuttgart (DE) – www.iba27.de/en/team/andreas-hofer-3/ Elisabeth Merk (DE) — Architect, Planning Director of the City of Munich, honorary Prof. at the TUMunich (DE) https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisabeth_Merk

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Susanne Eliasson (FR/SE) — Architect, Grau strudio, Paris (FR) www.grau-net.com Akil Scafe-Smith (UK) — Architecte, RESOLVE, researcher at LSE Cities – www.resolvecollective.com

Paola Vigano (IT) — Architect, urbanist, Studio Paola Vigano, Milan (IT); Professor in Urban Design at the EPFL Lausanne (CH) and at IUAV Venice (IT) – www.studiopaolavigano.eu Bernd Vlay (AT) — Architect, StudioVlayStreeruwitz, teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna (AT) – www.vlst.at

PUBLIC FIGURE

Elke Krasny (AT) — Cultural theorist, curator, urbanist, author, PhD, Professor at the Academy of Fine Arts of Vienna (AT) www.elkekrasny.at

SUBSTITUTES

Benni Eder (AT) — Architect, studio Eder Krenn, teacher at TU Vienna (AT), E13 winner in Linz (AT) www.studioederkrenn.com

Daniela Herold (AT) — Architect, THuM ateliers, Linz (AT), E7 winner in Salzburg (AT) – www.thum.co.at

SUISSE / SCHWEIZ / SVIZZERA / SVIZRA

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL ORDER

Ariane Widmer Pham (CH) — Architect-urban planner, State of Geneva urban planner (CH)

Claudia Bauersachs (CH) — Director Plannification and bulding at Wohnen & Mehr, Basel (CH) – www.wohnen-mehr.ch Ola Söderström (SE) — Professor of Social and Cultural Geography, University of Neuchâtel (CH) – www.unine.ch

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Mireille Adam Bonnet (CH) — Architect, Atelier Bonnet, Geneva (CH) – www.bonnet-architectes.ch Pascal Christe (CH) — Mobility engineer, Christe & Gygax Ingénieurs Conseils, Yverdon-les-Bains (CH) www.cgingenieurs.ch

Sarah Haubner (DE) — Architect, Office Oblique, Zürich (CH), E14 winner in Kriens (CH) – www.officeoblique.com Mathias Heinz (AT) — Architect, Pool Architekten, Zürich (CH) – www.poolarch.ch Lukas Schweingruber (CH) — Landscape architect, Studio Vulkan, Zürich (CH) www.studiovulkan.ch

PUBLIC FIGURE

Frédéric Bonnet (FR) — Architect urban planner, Obras, Paris (FR) – www.obras.fr

SUBSTITUTES

Yony Santos (CH) — Architect, Typicaloffice, E13 winner, Genève (CH) – www.typicaloffice.ch Barbara Stettler (CH) — Architect, SIA internal Affairs department, Biel (CH) – www.sia.ch

SVERIGE

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL ORDER

Tina Saaby (DK) — Architect urbanist, City architect of Gladsaxe (DK) – https://twitter.com/tinasaaby Jessica Segerlund (SE) — Art curator, Head of place development at Älvstranden, Göteborg (SE) https://alvstranden.com/

URBAN / ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Karing Bradley (SE) — Associate professor urban planning and environment at the KHT, Stockholm (SE) – www.kth.se/en/som Anna Chavepayre (FR) — Architect, Collectif Encore, Labastide Villefranche (FR) – www.collectifencore.com Bengt Isling (SE) — Landscape architect, Nyréns arkitektkontor, Stockholm (SE) – www.nyrens.se Ted Schauman (FI) — Architect urbanist, Schauman & Nordgren Architects, Helsinki (FI) www.schauman-nordgren.com

PUBLIC FIGURE

Christer Larsson (SE) — Architect, Adjunct Professor at Lund University, Malmö (SE) – Christer Larsson

SUBSTITUTE

Tove Fogelström (SE) — Architect, AndrénFogelström, Stockholm (SE), E15 Winner in Täby (SE) www.andrenfogelstrom.se

And After?

— Co-production

It is first a competition on territorial, urban and architectural scales aiming to bring out talents capable of formalizing strong and creative ideas in response to contexts given by cities and in relation to a theme reflecting social, economic, cultural and environmental issues of European cities. It is therefore a labelling procedure for young talented designers — architects, landscapers, urbanists…— based on innovative ideas. For this E16 session on the inspiring theme of Living Cities — Inclusivity and Metabolism, 40 sites were selected to participate to the competition, offering the young professionals a set of situations of the Anthropocene that mix natural and historical qualities with spatial problems —infrastructures, fragmentation, anti-ecologic areas…— a result of the last decades of functionalist urban development. A change of paradigm operates in this session’s winning teams’ projects, that shows more respect for the living dimension of the sites and the existing, yet articulated to its social evolution, trying to create hybridity between a metabolic approach and an inclusive attitude at different scales between the two parameters. For the winning teams there is a direct “benefit” of participating and being rewarded: receive an award of €12,000 for the winners and €6,000 for the runners-up, accounting all in all to more than €75,000. The second benefit for the winning teams is the advertising

done through catalogues, interviews and publica-

tions in the different Europan countries and at the European level (just like the present catalogue). We would like to reinforce these indirect effects of promotion. Helped by the National Secretariats in each country the goal is to make the winning teams —thanks to the Europan label— access other orders and competitions where they can develop their talents.

But the most challenging part of Europan is the postcompetition phase: to make the winning teams develop their ideas to a negotiated project on the sites, that will integrate all the local actors. In this part —the implementation phase— the key to the success is to start a discussion with all the actors on the winning ideas and to federate them around main guidelines that could be, for the people in charge of urban planning, a structure to start the process in time. The contexts’ territorial or urban dimension make the challenge complex, as many factors can delay or even prevent the development of a process right after the competition or along the way: political changes, economic crisis, multiplicity of soil property, soil contamination, lands resale to others investors, multiplicity of actors involved, arrival of news actors at different levels. But despite the difficulties, which vary from one context to another, a significant part of the sites is transformed thanks to several elements: the relevance of the winning ideas, the team’s ability to be part of an operational process, the other partners’ ability to engage in innovative proposals for their territories and to manage adaptative processes.

An important phase is what we call the intermediary phase, which takes place after the competition, but before any decision is made on the contractual phase. During this period, there are different ways, depending on the countries and contexts, to create a connection between the local actors: owners, municipalities, administration, users… and the young professionals. Sometimes it can be a workshop with the two or three teams selected by the jury for a phase of discussion and exchange to see which projects better corresponds to the situation; or, on larger sites, to see how several ideas can be developed together in a positive way. It is a period when the sites representatives better understand the ideas selected in their diversity and the teams that carry them. Of course, after some months of this intermediary phase it is important that the actors integrate the ideas in an operational process in steps and professional contracts be given to the teams to continue the procedure.

To illustrate different types of implementations, three processprojects are presented on different scales and diversity of implementation methods:

— In Wien (AT), Europan 10, on a 10-ha site with the goal to implement 1,000 housing units, the fundamental idea was to develop a diversity of housing architecture around a grid of gardens shared by the inhabitants at the proximity scale. Ten years of negotiation were necessary to federate all the actors through an intense participation process. The winning team was in charge of the design with an addition of experts and they managed, with the city of Wien, all the urban project involving a multiplicity of clients (private, social, public…) and built –as architects– one part of the whole, including 82 housing units. The continuity of the different phases and the coherency of the initial idea were maintained despite the necessary program changes.

— In Marseille (FR), Europan 12, a social housing estate was demolished due to its obsolescence, and replaced by a new district, unfinished to this day. In a beautiful natural Mediterranean landscape, the runner-up team proposed to hybridize new types of collective housing with public spaces. The project was also integrated in a participative process. A first step was to test a sport space; then a 7.5-ha public space was developed integrating leisure space for the inhabitants of the districts, and particularly the young people. Today the building of a new type of collective housing is in progress, offering quality private spaces and a good relation between indoor and outdoor.

— In Lasarte-Oria (ES), Europan 15, the construction of a building of 100 housing units with workspaces has started in a natural environment. It is a project at a smaller scale, nevertheless mixing architectural and landscape levels. During the implementation process, in order to integrate the jury’s request to open the internal courtyard, the work-housing mix inside the building was further developed, with variable devices following the different floors.

These 3 very different implementation processes show that it is first necessary to have a strong winning idea as a base for discussion between the actors; then, to properly integrate the specificity of the place and its potential evolution on uses; to make participative procedures that enrich the projects and give them their credibility; and then, of course, it is essential that the negotiated idea/project be supported by the party in charge of the implementation through procedures that often have to be invented in order to reach the innovative dimension of the project.

I hope that a majority of the E16 winning ideas can be integrated in such positive and productive processes in order to participate to the big change in the Nature-Culture relationship to see projects emerge reinforcing biodiversity, mixing the respect for the living (human and non-human actors) with the social evolution of the contexts, and imagining new ways to reinvest the existing in order to reinvent the future.

EUROPAN 10 — 2009-2022 FULL PROCESS PROJECT COMPLETED ARTICULATING URBAN, LANDSCAPE AND ARCHITECTURAL SCALES ARE (AUSTRIAN REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT GMBH) CITY OF VIENNA - MA21 OFFICE

Towards a habitable suburbanity

THE CITY OF VIENNA PROPOSED FOR E10 A 10 HECTARES SITE LOCATED IN THE SOUTHERN PART OF THE CITY TO

DEVELOP A RESIDENTIAL

DISTRICT AND RESPOND TO URBAN GROWTH

THE PRIZE-WINNING IDEA IS TO DEVELOP ON THESE 10 HECTARES A DIVERSITY OF WAYS OF LIVING AROUND A GRID OF SMALL GARDENS, SHARED SPACES OF PROXIMITY

WITHOUT MODIFYING THE PRINCIPLE OF THE GREEN GRID, THE PROJECT HAD TO EVOLVE TOWARDS BUILT DENSIFICATION, MULTIPLYING THE TYPOLOGIES

ENRIQUE ARENAS LAORGA (ES) LUIS BASABE MONTALVO (ES) LUIS PALACIOS LABRADOR (ES) ARCHITECTS ARENAS BASABE PALACIOS ARQUITECTOS, MADRID (ES) ESTUDIO@ARENASBASABEPALACIOS.COM WWW.ARENASBASABEPALACIOS.COM

with reasoned densities and shared natural spaces

MANY ACTORS HAVE BEEN INVOLVED DURING 10 YEARS IN A PARTICIPATORY PROCESS: PLANNERS, PROMOTERS, URBAN AND LANDSCAPE EXPERTS, USERS…

©Schreiner, Kastler – Büro für Kommunikation THE OFFICE SUPERVISED THE IMPLEMENTATION OF 1000 HOUSING UNITS ACCORDING TO THEIR STRATEGY AND

DESIGNED AND BUILT 82 HOUSING UNITS

IN PART OF THE DISTRICT

EUROPAN 12 — 2013-2022 FULL PROCESS PROJECT COMPLETED ARTICULATING URBAN, LANDSCAPE AND ARCHITECTURAL SCALES MARSEILLE RÉNOVATION URBAINE ERILIA SOLEAM / CITY OF MARSEILLE

Rehabilitation of a social district

IN THE DIFFICULT DISTRICTS IN THE NORTH OF MARSEILLE, A LARGE COMPLEX WAS DEMOLISHED AND REPLACED BY A

NEIGHBOURHOOD THAT NEEDED TO BE COMPLETED

WITH THE OTHER RUNNERUP TEAM, THE DANISH OFFICE ARKI_LAB, IS DEVELOPED A PARTICIPATORY APPROACH ON THE FUTURE OF THE SITE, PRELIMINARY TO THE IMPLEMENTATION THE PRIZE-WINNING PROJECT FROM CONCORDE OFFICE DISSOCIATES THE LAND OWNERSHIP FROM THE BUILDING, STRUCTURED BY A 5 X 5 M GRID WITH LOW-COST FLEXIBLE RENTALS

SIMON MOISIÈRE (FR), JEAN RODET (FR) ADIRNE ZLATIC (FR) ARCHITECTS NICOLAS PERSYN (FR) GEOGRAPHER CONCORDE, MARSEILLE (FR) CONCORDE@CONCORDE-A-U.COM WWW.CONCORDE-A-U.COM

by connecting creative public spaces and mixed housing

A PARTICIPATORY PLAYGROUND IS USED AS TEST TO THINK ABOUT

CREATIVE PUBLIC

SPACES PROJECT (2HA), CONNECTION BETWEEN FRAGMENTS AND LANDSCAPE

A MIXED HABITAT —PLANNED IN THE COMPETITION— IS IN PROGRESS IN THE SOUTH OF THE SITE, DESIGNED BY CONCORDE OFFICE. TO BE FOLLOWED…

EUROPAN 15 — 2019-2022 PROCESS PROJECT IN PROGRESS ARTICULATING LANDSCAPE AND ARCHITECTURAL SCALES

Hybridize housing and workspaces

IN A RURAL AND SUBURBAN AREA, THE CHALLENGE IS THE DESIGN OF A NEW TYPE OF HABITAT THAT PROMOTES THE PRODUCTION

REINFORCING BIODIVERSITY, THE PRIZE-WINNING PROJECT IS SET UP ON THE SLOPE AND PROPOSED A MIXED OF HOUSING (100 DWELLINGS) AND PRODUCTIVE SPACES

ALEX ETXEBERRIA AIERTZA (ES) EDUARDO LANDIA (ES) ARCHITECTS TARTE. ARKITEKTURA, ZARAUTZ (ES) TARTE@TARTEARKITEKTURA.COM WWW.TARTEARKITEKTURA.COM ELE ARKITEKTURA, DURANGO (ES) EDUARDOLANDIA@ELEARKITEKTURA.COM WWW.ELEARKITEKTURA.COM

thanks to a change in regional regulations

FROM THE COMPETITION TO THE IMPLEMENTATION THE PROJECT EVOLVED: AT THE REQUEST OF THE JURY THE 2 BRANCHES OF THE BUILDING HAVE BEEN SHORTENED AND A POROSITY OF THE COURTYARD CREATED

TO MIX USES, THE REGIONAL

REGULATIONS HAVE

BEEN ADAPTED. THE GROUND FLOOR BECOMES PRODUCTIVE; ON THE UPPER FLOOR ARE HOUSING + WORK DUPLEXES

Europan 16 Secretariats

europan EUROPE 16 bis rue François Arago 93100 Montreuil — FR +33 962529598 contact@europan-europe.eu www.europan-europe.eu

PARTICIPATING COUNTRIES

europan BELGIQUE / BELGIË / BELGIEN c/o Architects House Rue Ernest Allard 21 1000 Bruxelles — BE secretariat@europan.be www.europan.be

europan DEUTSCHLAND Friedrichstraße 23 A 10969 Berlin — DE +49 3039918549 mail@europan.de www.europan.de

europan ESPAÑA Paseo de la Castellana 12 28046 Madrid — ES +34 914352200 (ext. *214) europan.esp@cscae.com www.europan-esp.es

europan FRANCE – GIP EPAU 16 bis rue François Arago 93100 Montreuil — FR +33 148577266 contact@europanfrance.org www.europanfrance.org

europan ITALIA c/o Consiglio Nazionale Architetti PPC Via Santa Maria dell’Anima 10 00186 Roma — IT +39 0662289030 contact@europan-italia.eu www.europan-italia.org

europan NORGE Møllendalsveien 17 5009 Bergen — NO post@europan.no www.europan.no europan ÖSTERREICH c/o Haus der Architektur Palais Thinnfeld Mariahilferstrasse 2 8020 Graz — AT +43 1212768034 office@europan.at www.europan.at

europan SUISSE / SCHWEIZ / SVIZZERA / SVIZRA c/o Bart & Buchhofer Architekten AG Alleestrasse 11 2503 Biel — CH +41 323656665 bureau@europan.swiss www.europan.swiss

europan SVERIGE c/o Asante Architecture & Design Brännkyrkagatan 98 11726 Stockholm — SE +46 706577192 / +46 707141987 info@europan.se www.europan.se

PARTNER COUNTRIES

europan HRVATSKA c/o Ministry of Construction Republike Austrije 20 10000 Zagreb — HR info@europan.hr www.europan.hr

europan NEDERLAND c/o URBANOFFICE Architects Zeeburgerpad 16 1018 AJ Amsterdam — NL info@europan.nl www.europan.nl

europan SUOMI – FINLAND Malminkatu 30 00100 Helsinki — FI info@europan.fi www.europan.fi

Europan 16 results This book is published in the context of the sixteenth session of Europan

HEAD OF PUBLICATION Didier Rebois — Secretary General of Europan

EDITORIAL SECRETARY Françoise Bonnat — Europan Europe responsible of Europan publications

AUTHORS Carlos Arroyo Zapatero — architect, urban planner, Carlos Arroyo Arquitecto, teacher in Madrid’s Universidad Europea (ES) Céline Bodart — PhD in Architecture, researcher, teacher at Paris-la-Villette School of Architecture (FR) Aglaée Degros — architect, Artgineering in Brussels (BE), professor and director of the Institute of Urban Planning in Graz (AT) Julio de la Fuente — architect, urban planner, Gutiérrez-delaFuente Arquitectos, Madrid (ES) Miriam García García — PhD in Architecture, landscaper, urban planner, Landlab, professor, Barcelona (ES) Didier Rebois — architect, Secretary General of Europan, teacher at the ESA school of architecture, Paris (FR) Nicolás Martínez Rueda — architect, founder of DOCEXDOCE Architecture Competition, Barcelona (ES) Socrates Stratis — PhD in Architecture, urban planner, co-founder of AA & U, Associate professor, Nicosia (CY) Dimitri Szuter — architect, researcher, dancer and performer. Co founder of the P.E.R.F.O.R.M!, Paris (FR) Bernd Vlay — architect, teacher, director of StudioVlayStreeruwitz, president of Europan Österreich — Wien (AT) Chris Younès — anthro-philosopher, professor at the ESA school of architecture. Founder and member of the Gerphau research laboratory, Paris (FR), founder and member of ARENA

ENGLISH TRANSLATION Frederic Bourgeois

GRAPHIC DESIGN AND LAYOUT Radiographique — Léa Rolland & Redouan Chetuan www.radiographique.com

PRINTING UAB Balto print (Vilnius, Lithuania)

EDITED BY Europan Europe Montreuil, France www.europan-europe.eu

ISBN n° 978-2-914296-33-5 Legally registered Second quarter 2022

16