A year ago today, ETHS went on hard lockdown. It started midway through first period with a code white, or a soft lockdown— students were already tense with COVID-19 cases spiking and the semester about to end. Soon, the school was buzzing with confusion and speculation.

The next period, the loudspeaker’s chimed yet again, and then-Superintendent Dr. Eric Witherspoon announced a code red, also known as a hard lockdown, in which everyone in the building was instructed to hide wherever they were until given the all clear. Students were given little information for hours, and rumors spread about a possible school shooting.

Two and a half hours later, when the all clear was finally given and Witherspoon shared what had happened, two students found with guns, emotions remained high.

“It was just fear the entire time,” senior Alice Lavan shared at the time. “I think, at a certain point, I was just so overwhelmed and anxious, and the emotions had just built up so much that any good news wasn’t really going to make me feel better.”

Eleven months later, in November, ETHS students and families received a “Community Notice” via email. It explained that a student had brought a loaded gun to school that day, and that there was “no knowledge of any threat or any danger to staff or students.”

The next morning, students heard that same loudspeaker chime, and Dr. Marcus Campbell, the current superintendent, addressed not only the events of the day prior but also mounting concerns throughout the community about how to make ETHS safe.

“I want to be clear about a goal of ours, and hopefully all of us will share this: let’s keep weapons out of ETHS. I don’t want metal detectors. I don’t like what they mean; I don’t like what they would make the school feel like. Logistically, they’re a mess to implement. There are many, many problems with it. And when we have measures like that, it compromises all of our humanity. I trust you to make the right choice not to bring weapons to school. But if we continue to find them, we’re going to have to find ways to keep them technically out of

In the space between these two announcements, the discourse on safety—in both schools and the broader community—has shifted in many ways. Campbell’s first day as the district superintendent was July 5, the day after a mass shooting at the Highland Park parade. One of his first actions as the superintendent was expressing sympathy for those lost. Last year, a shooting at the Mobil on Green Bay Road left five teenagers shot, one of which died. More recently, at the McDonalds only a block away from ETHS, shots were fired after school. These are only a few of the gun-related incidents in and around the Evanston community.

Simultaneously, ETHS has been grappling with the relationship between safety and discipline. After COVID-19, the school reworked policies to allow leniency as students readjusted to in person education. But this year, the school administration has reversed many of those rules and put in place policies aimed at what many on the administrative team have referred to as ‘loving accountability,’ with the aim of increasing student academic success. However, many students have focused less on the rationale behind these policies and more on the consequences. From policies barring phones from classrooms to stricter rules around lunch and tardies, students have expressed feeling more controlled and more surveilled.

While students are having those conversations, the discussions among the adult community around ETHS are often focused on a different set of issues. At the Nov. 14 school board meeting, staff members communicated a problem with ‘in-school truants,’ a term for students who are showing up to school every day but not attending class. Administrators and teachers are working to help support students who struggled during online learning while also making adjustments to make the school physically safer.

Just last week, Principal Taya Kinzie sent home an email to students and families that listed out the changes that have been made, while also adding that the school will “continue to look at layers of deterrence. This includes sophisticated weapons detection systems that can maximize both our wellbeing and our human-

ity.”

As the school negotiates how to make itself physically safe and support academic success, there is the question of who historically has felt safe at ETHS. According to the 5Essentials survey, a yearly survey schools distribute to determine how well they are doing across five core elements of the school experience as determined by researchers at the University of Chicago, Black students at ETHS have reported feeling the most unsafe at school out of any racial group the survey accounts for over the last four years. Black ETHS students’ responses to questions about safety in and around school yielded a score of 36 from 5Essentials, compared to white ETHS students’ score of 45. Over the last four years, Black students have consistently reported feeling the least safe out of any racial group at ETHS.

It is a year to the day of ETHS’ hard lockdown. Heading into 2023 and beyond, the school’s efforts to protect students’ physical safety may be in tension with supporting the emotional safety of its most marginalized students. As a community, we are living through a moment where we are forced to reexamine our personal relationship with safety and ask ourselves what we need to do to make our school and community safe in every aspect of the word.

In this issue, each story will examine one aspect of safety in Evanston or ETHS. Each piece can stand on its own, but we’ve created this set of stories as a whole to illustrate our attempt at a nuanced, in-depth portrait of safety in our community. We’ve placed pieces about the connections created between safety officers and students next to articles about the way that safety presence can create discomfort for many, and pieces about ETHS setting the stage for positive change next to critiques of its policies. We hope that you take the time to read as many of these pieces as possible, identify the broader trends and tensions that exist and consider the vision of this community that we have presented you with alongside your own views and experiences.

By Ahania Soni Executive Editor

By Ahania Soni Executive Editor

When speaking about safety, we tend to hear the word “after.” “After Columbine,” “After September 11th,” “After Sandy Hook,” etc. We use these scarring events as markers to gauge dramatic shifts. We focus on the post-event atmosphere, but never the before. When the ETHS and broader Evanston community discusses safety, many of us fall back into this language: “After Highland Park,” “After the gas station shooting” and “After December 16th.” But the reality is, there are students that have felt unsafe at ETHS before all of these events, and many of those students are from marginalized communities.

Conversations about safety at ETHS are happening between students, parents and guardians, teachers and administrators, and The Evanstonian has a commitment to the Evanston community to thoroughly and intentionally address this topic. Too often, these discussions are solely driven by measures to make school physically protected from violence, and in the process, the conversation becomes dominated by policies and practices that yield fear, surveillance and control. That said, ETHS will not be a truly safe place until marginalized students are free from excessive policing and discipline within their educational experience.

This begins with acknowledgement of past and present injustice, conscious community building and deliberate policies to change the current climate surrounding safety at ETHS. Recently, the administration has instilled policies that have contributed to a culture of fear. These policies include an uptick in surveillance, an increased focus on policing the hallways and ‘in school truants’ as well as a harsher procedure surrounding disciplinary infractions such as being tardy or having a phone in class. ETHS students should be able to follow the rules, because they trust the people who made them, rather than fear those in charge.

The first step in building trust is clear communication and transparency. The school needs to increase its education surrounding expectations for students and what will follow in the event that these expectations are compromised. This includes advertising the importance of the Pilot and carefully breaking down the key ele-

ments of the Pilot in digestible formats for students, potentially through teachers, announcements and/or emails. In addition, we also urge the administration to carefully reconsider what offenses are eligible for expulsion and how that information is organized in the Pilot. For example, on page 38 of the Pilot, pepper spray is listed as a prohibited item, which is not noted as eligible for expulsion. However, on page 41, pepper spray is categorized under weapons, which can warrant expulsion for up to two calendar years. This conflicting information creates a lack of clarity for students reading the handbook. In our investigation of this topic, we interviewed two separate students who had no previous disciplinary violations and complied with the administration after being found with pepper spray on their person, yet they were given a recommendation for expulsion. This lack of clarity poses the question: when does ETHS choose expulsion and why? Statistics show that the vast majority of suspensions and expulsions are administered to students of color, which we explore later in this issue. In order to bridge this gap, the administration must take measures to prevent students of color from being eligible for expulsion and revise the severity of punishments that students receive based on their infraction.

To be clear, The Evanstonian does not condone any violation of the school’s code of conduct, but at a school full of teenagers, mistakes are bound to happen in addition to violation s with intent, and there needs to be a careful and equitable procedure in place to appropriately manage these occurrences. When a student is convicted of a school offense, the administration must practice full transparency throughout every stage of the disciplinary process. Many students do not know their options and rights when it comes to this corrective procedure, and it is the administration’s responsibility to fully and honestly reveal this information to students. Misconceptions about Pilot policy and the appeal process drive students to accept consequences that they do not believe align with their behavior. Students at ETHS are being sent to attend school at a different location, because when presented with this option in lieu

of further consequence, they can be coerced to believe that if they do not accept this deal, they will be expelled. These students do not know who to talk to and what support they have available to them, and therefore, they are disadvantaged throughout this process.

Broadly, because of these aforementioned factors, our current discipline system does not work. This process should be student-centered and equitable, but instead, it is often impersonal and discriminatory. A possible solution to this is a peer jury, with which some districts across the country report having found success, or the school could consider any of the plethora of restorative justice practices that are being implemented in other places. In 2016, when ETHS made the leap of changing the school dress code, the administration replicated the recommended dress code by the Oregon National Organization for Women in order to create an effective new model. In changing the current discipline policy, we expect the administration to, once again, use procedural models that are built on the foundation of equity to form a thoughtful and effective revised structure. In addition, when a student endures a disciplinary consequence that excludes them from attending school at ETHS, the administration must provide more support to help them return to ETHS classrooms.

Following a return from a long suspension or alternative schooling program, students are often left feeling isolated and sometimes unsupported. We advise the administration to establish a reintegration program to confirm that a student is in a healthy state of mind and feels prepared to return to ETHS. Part of this may include initiating a meeting between the student and a school mental health professional to equip the student with the proper resources to return to school. In a school with over 3,600 students, the administration must go the extra mile to protect students and their social-emotional wellbeing with individualized support.

We understand that physical safety is a priority. The Evanstonian does not attempt to conceal or underplay the suffering that gun violence has infected our nation with, nor the right to a physically safe school. We acknowledge that safety

in high schools is a national concern, and the community has a right to emotionally and assertively invest in it. Physical safety must be a priority, but it cannot be prioritized over mental and emotional safety of students. They must be co-existing forces, and that is the balance that we ask the administration to conscientiously reflect upon and integrate into ETHS procedure.

We would like to acknowledge our position when analyzing this topic, which has historically disserviced students of color at a disproportionate rate in comparison to their white counterparts. As a primarily white editorial board and publication, we acknowledge that white students have not been historically disenfranchised by the policies and procedures we discuss in this issue, and as a result, our personal experiences affect our ability to accurately report on these stories and see our identities reflected in these pieces.

We recognize that the safety concerns we investigate throughout this issue pertain to high schools across the nation, and we are privileged that we have the resources at ETHS to address this topic in a meaningful manner. However, at a school and a community that has been nationally recognized as leaders for change, it is shameful that despite having the awareness and the capability to create policies that reinforce empathy, we still find ourselves producing policies that dehumanize marginalized students. ETHS must do better.

As you engage with this issue, it is vital that the conversation does not end here. The Evanstonian recognizes that safety in high schools is a nuanced topic, and we have not at all addressed all aspects of this issue. The community and the administration must commit to tackle this historically significant topic through ongoing reflection, dialogue and action. We have a long way to go to make school a safe space, both physically and emotionally for all students, but we hope that our December issue of The Evanstonian serves as a piece of this continuum that moves us towards justice.

Content warning: This article contains descriptions of gun violence and its after-effects.

A 13-year-old Bulls fan is preparing for the next school day at Haven Middle School. It’s a Thursday, and he only has a week left before graduation and then his birthday. He’s an eighth grader, so he’ll be moving on to Evanston Township High School next school year. It should have been one of the happiest weeks for him all year. His family had just set up a motion detector light outside of his aunt’s house. The boy steps outside a side door to test the new feature. He is struck by a stray bullet. The child runs back inside the house and tells his aunt that he has been shot before immediately collapsing to the floor. The boy’s name is Wayne Hoffman, and he died in Evanston on June 6, 1997 at 12:50 a.m. Evanston is a community grappling with gun violence. It was then, and it is today. The events of last year’s lockdown at ETHS, and other situations involving guns—from the killing of Devin McGregor, an Evanston elementary school student, the shooting at the McDonald’s on Dempster Street, to the gun found on a student inside the school last month have contributed to a growing awareness of how guns are currently impacting Evanston.

At ETHS, there have been a number of policies, both implemented and pondered, that aim to combat the issue of school safety head on, with the school putting into place new safety procedures to more accurately know who is in the building at all times as well as considering the implementation of metal detectors or other alert detection systems. To understand where the fear of guns comes from and why the Evanston area has been struggling with it, we must look back forty years, to when the Evanston City Council passed its first ordinance banning handguns.

***

Forty years ago, on Sept. 13, 1982, the City Council passed an ordinance banning handguns in the city limits. The ban was in place to limit violent crime in the City of Evanston. It was enforced lightly, with a limited number of police officers imposing the will of that particular law.

Evanston was, at the time, the largest city to ban handgun possession. The law prohibited possession of handguns within city limits. Before this law was passed, 10 percent of Evanston residents owned a handgun, compared to 15 percent nationwide. And yet, the ordinance did not have a discernible impact. Evanston had a 24 percent drop in armed robberies in the following years, versus 21 percent across the U.S. That three percent was a difference of six robberies, going from 193 to 187.

Evanston already had five percent fewer guns than the national average when the handgun ordiance was implemented. Only 74 handgun violations occurred from 1983-1985.

Evanston was a safe city then, and compared

to the rest of the country, it still is today. The most recent FBI crime rate statistics are from 2019, when Evanston had a total of 115 violent crimes. During 2020, the city had a total of 130 violent crimes. This means that for every 606 people in Evanston, one was a victim of a violent crime. Not only is this almost half of the armed robberies alone from 1983, but it is also lower than the country-wide average. Just as crime has dramatically decreased since it peaked nation-wide in the 1990s, the same is true in Evanston. Still, COVID-19 had a dramatic effect on the nation, and one way its impact has been felt is through an increase in crime following decades of decreases. Yet, there have been a number of gun-related incidents in the last 13 months that have led Evanstonians to another period of fear across the community with regards to guns.. ***

In the city of Evanston, gun violence has come in waves. One of the waves of violence is from the mid to late 1990s, when two teenage students and one ETHS graduate were shot and killed on separate occasions in Evanston. All three of the murders could be connected to gang violence.

The first of the incidents came on June 11, 1996, when 1995 graduate Andrew Young was shot and killed while he waited at a stoplight at Howard and Clark Streets in Chicago. Young was a speed skater who had trained with gold medalist Dan Jansen. After 10 years of training, he decided to call it quits so he could attend DeVry Technical Institute. He was slated to start school there in the fall of the year he died.

Gunman Mario Ramos had graduated from ETHS two days before. His accomplice, Roberto Lazcalo, was fifteen at the time of the shooting. Ramos and Lazcalo came to the stoplight on a motorcycle where Young was waiting in a car. Ramos walked to the driver’s side and fired off several shots. According to an old Evanstonian article, witnesses claim that Lazcalo flashed a gang sign as Young was shot. Young was not known to have had any involvement in gangs, but it appears he was the target of one anyway.

It was only a few months later on Dec. 12, 1996, when fifteen-year-old sophomore student Ronald Walker II was murdered as he left a grocery store near ETHS. He was shot twice with a handgun, once in the forehead and once in the left ear. Walker died almost instantly. According to former Evanston Police Lt. Charles Wernick in a news conference, “There was no confrontation. In our estimation, it was nothing short of an execution,” he said.

Almost a year later, it was uncovered by the Evanston Police Department that Walker had been shot by Frank Drew, an Evanston resident, and Jeffrey Lurry. The two gunmen claimed to have shot Walker because they mistakenly believed he was a member of a rival gang. Drew and Lurry were walking in the territory of a rival gang, dressed in all black. After seeing Walker, they approached him after he exited a corner grocery store. Both Drew and Lurry fled on foot after the killing, afraid of retribution for their ac-

tions from either a gang or the police.

The death shocked everyone in Evanston, sparking anti-violence and anti-gang marches throughout the city. Sherry Walker, Ronald’s mother, was distraught.

“I always wanted to be to this point where I could be a little at peace. I’m not totally at peace, because my son is gone; he’s never coming back,” she said at a news conference close to a year after the shooting.

The next incident came on June 5, 1997, the day that Hoffman was shot. The thirteen-yearold eighth grader who went to Haven Middle School was only a week away from graduating and moving on to ETHS when he was the tragic victim of a sniper attack and shot in the back in the middle of his shoulder blade.

The murder was not intentional. Hoffman was shot by a stray bullet that was meant for a gang gathered on the front porch of his aunt’s home. The shooters, Jeffrey Williams and Larry Cox, had several altercations earlier in the day leading up to the final confrontation with the group. Hoffman was not part of any of the arguments.

“It is indescribable,” said Cmdr. Michael Gresham, former head of the Evanston Police Department’s investigative services division in an Evanston Review article. “I just hate to use the ‘wrong place, wrong time’ [phrase], but he took what somebody shot at somebody else.”

Many in the community were shocked by the murders. It almost felt as though they were random, like the flu. Swift and painful. three past, present and future ETHS students had been killed at a young age, without the city being able to see what people they would turn out to be.

Young’s twin brother Sam, who was in the passenger’s seat during the shooting, described the moment after the shot was fired.

“Drew just faded. I watched his spirit leave.”

The same could be said of Hoffman, Walker and many other gun violence victims.

***

When researching spikes in gun violence, one of the questions that immediately comes up is why? Why does gun violence act the way that it does? Northwestern professor of sociology Andrew Papachristos had that same question in the

mid-2000s and answered it through a research study, titled Modeling Contagion Through Social Networks to Explain and Predict Gunshot Violence in Chicago, 2006 to 2014.

Using the underlying principle of Papachristos’ research, the spike in gun violence around the late nineties can be attributed to something called the contagion effect. When it pertains to gun violence, ‘contagion’ is the idea that the change in gun violence trends can be compared to that of a virus. This explains the wave-like nature of gun violence over time. It also serves to explain outbreaks in armed violence, like the short stretch from 1996 to 1997.

In the study which was published on Jan. 3, 2017, in JAMA Internal Medicine, Papachristos’ research team at Yale studied the probability of an individual becoming the victim of gun violence using an epidemiological approach.

“Academics, when they study these things, contagion, or spread, a crime rate, what has an impact? So I started trying to think about how it actually spreads. One of the questions I had was, ‘Do you catch a bullet like you catch a cold?” Papachristos said.

The study analyzed a social network of individuals that were arrested over eight years in Chicago through an epidemiological lens. Of the 138,163 participants arrested between Jan. 1, 2006, and March 31, 2018, 9,773 were subjects of gun violence. One of the other questions Papachristos tried to answer was whether or not there was an element of randomness to gun violence. The answer to that was, no.

“When we look at disputes or the distribution of violence, whether it’s Chicago or Oakland or New York or New Jersey or Evanston, violence concentrates in a small number of places, specifically in the social networks. This is true through lots of social phenomena. But one of the things they say is what type of epidemic is it? It’s not as contagious as COVID or the flu; it’s very specific. It’s more like Hepatitis C or a sexually transmitted disease,” Papachristos said. “You have to do certain things or be in certain situations to contract it,” Papachristos said.

The results of the study concluded social contagion accounted for a staggering 63.1 per-

cent of 11,123 gun violence episodes. Subjects of gun violence were shot on average 125 days after their “infector,” a previous victim of gun violence the subject knew. The network map looks similar to one tracking infectuous disease.

“Back in the early 2000s, one of the things we did was we took shooting cases, like you see in the old movies. I started making connections between individuals in cases literally trying to map it out,” said Papachristos. This is almost the exact same thing that contact tracers do when tracking COVID-19 cases.

“It’s this network science,” explains Papachristos, “especially in epidemiology, where they use it to track diseases. I took those methods and started applying it to records of shootings, arrest records and other sorts of records to see if I could create or trace this information. It’s contact tracing.”

building was secure, a lockdown was called. While there was no active shooter, the memory of that day lives vividly in the mind of students.

Six months later, on Aug. 28, five-year-old Devin McGregor, a kindergartener at Willard Elementary School, was shot. He was so full of life that his family members gave him the nickname “Boom” for his upbeat attitude. McGregor was so excited to have started school that he wanted to go and visit his father in Rogers Park to tell him all about it. He was just getting buckled in for the car ride home when a black sedan pulled up and fired shots at the family. McGregor was shot in the head. He passed away a couple of days later.

On Sept. 2, there was a shooting at McDonald’s, only a few blocks from ETHS. Although the shooting was targeted, an isolated incident, the event still scared many in the area. It made

school year—literacy, equity, post-high school planning and social-emotional learning are the school’s main areas of focus.

Multiple board members voiced their support of action to prevent violence in Evanston.

“At ETHS, we don’t shy away from difficult topics. [Gun violence] has got to be pretty up there in one of the most difficult topics. If a topic makes us uncomfortable, we still go there, because we recognize that it’s important for our students to dive into these topics,” president Pat Savage-Williams said at the meeting. “There’s been a lot happening. Our students have been threatened, traumatized and hurt; some have even been killed. That’s been happening. Educators and parents have lived with the reality that gun violence and shootings seem to be a part of our community. It’s not just Evanston; it’s nationwide, like an epidemic. It’s put us all on edge. Our kids are scared, our staff is scared, I’m scared.”

On Nov. 9, an incident occurred at ETHS where a student was found to have had a gun inside the building. The retrieved gun had not been fired. Administration, in conjunction with the EPD, had determined that there was no active threat of violence to any students or staff, which is why a lockdown was not called.

Guns have been a problem for much of Evanston, but it’s challenging to devise a solution to gun violence because it’s such a complex issue.

“We don’t actually know why [gun violence] went up after 2020,” Papachristos says. “We don’t know the reasons why it was down earlier, and there’s not one thing that happened now. There was a confluence of things that happened that made gun violence and homicides escalate the last couple years.”

That fact—that there are a number of factors that have amalgamated into the problem of community gun violence— makes it extremely difficult. Every answer has its questions, for example, does the benefit of student resource officers and metal detectors outweigh the possible racial profiling that has become so synonymous with those solutions?

“Experiencing gun violence is trauma, and living with the fear of gun violence is also trauma. Many of our students live with this trauma, impacting every aspect of their lives. Trauma is both the outcome of and the precursor to violence, creating a vicious cycle,” third-year board member Elizabeth Rolewicz said at the September school board meeting.

One of the common themes in the outbreak in the nineties was gangs. Whether it be Walker being shot because someone thought he was a member of a rival gang or Lazcalo reportedly throwing up a gang sign after he had shot Young. However, as Papchristos explains, stereotyping all gangs as dangerous can only worsen the problem. If people think gangs are unsafe, then people will feel unsafe, and one of the reasons people carry guns is to feel safer. It’s a vicious cycle.

“Most gangs are not highly organized. Groups are not like you see in the movie Training Day; they tend to be smaller crews of guys from a particular neighborhood who get together for protection and for fun. Sometimes, they get involved in illegal behavior. Most of the time, they don’t,” says Papachristos, “But conflict is a really important element. So if you’re afraid of one group, your gang might say to start carrying a gun because they feel the need for protection. Gangs don’t create gun violence, but they can amplify it. They can also amplify everything because there’s a built-in group process.”

The group process refers to the connection between the members of the gang. If someone calls another person a name alone, they can easily walk away. They don’t know each other, or care. But when a group dynamic is built-in, everything changes. Another member can say something like, “Are you just going to let him say that?” and the situation escalates. If another member says that and they have a gun, then everything changes again, especially if there are people pressuring others to use it. That’s when the dynamic becomes very dangerous.

The conclusion of the study, through intensive research into gangs, social networks and armed violence was that gun violence follows an epidemic style of contagion, transmitted through people by social interaction.

***

The first case in this recent wave of gun violence in Evanston, what one could consider the index case of the new wave, occurred on Nov. 28, 2021, as the Evanston Police Department responded to multiple 911 calls at a Mobil gas station located just off Green Bay Road. They arrived on the scene to find five wounded high school students. One of them, Carl Dennison, senior at Niles North, died on the scene. While the remaining four survived, so did the trauma from their experience.

Then, a month later, ETHS was put on lockdown on Dec. 16, 2021. The “code red” was called after students were found to be smoking marijuana in a bathroom in the school. When Safety searched those students, they discovered two handguns and immediately recovered them. As the school and the police determined that the

students unsure whether or not the school would be safe.

One of these students present at the shooting was sophomore Ethan Arnold. It was an ordinary afternoon as he walked to the nearby Starbucks with some friends. He suddenly heard three gunshots and started to get concerned.

“There was this big delivery truck right by the Starbucks. I heard a clattering noise, because I guess it broke the glass of the car the guy was in. And I thought it was the truck. But a couple of my friends who were by the McDonald’s ran by, and they’re like, ‘There’s a shooter!’ I was like, ‘No, there’s not. What are you talking about?’ I wasn’t entirely convinced there was a shooter, so I was nervous but not freaking out,” said Arnold.

“When acts of mass violence are repeated in this way, they start to feel more and more [overwhelming], and a sense of hopelessness starts to set in. Human bodies are not meant to be so frequently in a state of agitation. Some people may become desensitized to violence as a defense.

People feel so overwhelmed by the stress and worry that they have to compartmentalize it to a certain extent,” said Vaile Wright, senior director for healthcare innovation at the American Psychological Association (APA) in an interview with The Washington Post.

Arnold is one of many who have experienced this phenomenon of desensitization.

“The lockdown was scary for me, although I was kind of tucked in a room that was far from any entrances. When I had to go inside the Starbucks and hide, I wasn’t as freaked out this time, just because I had been through the process before,” Arnold said.

The many close calls with gun violence have affected Arnold in irreversible ways.

“I’m definitely very cautious. If I hear a loud noise, I’m like, ‘Whoa, was that another gun,’ and I always have an escape route. So even at school, I have a little plan for how to get out of whichever room I’m in,” Arnold said.

On Sept. 12, the District 202 School Board held its first meeting of the school year, focusing on gun violence. There have been numerous instances of high-profile gun violence in Evanston and the surrounding areas in recent years, such as the killing of Devin McGregor and the shooting at a McDonald’s on Dempster, only a few blocks away from the school. These instances have hit close to home, especially for an Evanston community with little experience in these situations. The ETHS School Board met to discuss, among other things, gun violence and its growing presence in the Evanston community. The school views gun violence as a public health issue. However, it was not made one of the key priorities the school announced heading into the

“My first day on this job was July 5. The first thing I have to do is get a message out about the violence to our friends in Highland Park,” saysSuperintendent Dr. Marcus Campbell. “I called every staff person who I know [who] lives in different areas, and I began to think about last year’s events, the lockdown. Think about what happened over the summer, where a 10-year old came to camp here with a gun. And I’ve said this over and over that the proliferation of guns in this country and in this community puts us all at risk. So when the murder happened last year, at the gas station, that set a lot of motion, and a lot of students tell me that they’re scared.”

Tervalon Sargent, McGregor’s grandfather, explained how guns had impacted him in an interview with ABC 7 Eyewitness News.

“You see it all the time, but it never hits until it happens to your family, and now I’m a part of another family because I’m a part of the families

“In addition to those who are victims of gun violence, there are many people impacted by the violence as it ripples through communities. There are many factors that contribute to a culture of gun violence, and this makes it a very difficult problem to solve,” she said.

Solutions have been proven effective on a national scale in other countries by implementing harsh gun laws. Still, it is challenging to control gun violence locally when gun laws are regulated at the federal level of government.

“There should be further psychological testing and to have shown a need for a gun before someone can purchase one,” Arnold says.

Solutions presented in other countries have worked, some similar to those that Arnold proposed. Evanston and the U.S. can look towards these countries for inspiration. In France, the right to own a gun is not inherent in its constitution. To own a gun, you need a hunting or sporting license that requires a psychological evaluation and must be renewed yearly. The punishment for

that this has happened to, and it’s the worst feeling ever. All these kids want to do is go to school and play, and they can’t even do that. That’s messed up. They can’t even do that, and it just keeps happening. It just keeps happening. We got to do something. We got to do something. “We got to do something.”

***

The ETHS administration has been attempting to find a solution to guns in the school.

“I’m trying to figure out how to partner with the city,” Campbell says, “But what can we all do together to help our kids feel safe? What needs to happen? What is happening on the city side? And so the city’s addressing their concerns. They are working with families that have been impacted by the violence in the community. For example, if a student has been impacted by violence in this town, we’ve got to provide them an education. How is the city supporting [that effort]? Our social workers and other mental health professionals are doing a little bit of talk therapy for students, but they don’t prescribe meds. They don’t diagnose. We’re working with the city to get a more collaborative effort going, so that we are all talking about what [the administration] sees from an education side, or what they see from some of the residents rather than just so we have a lot of differing plans in motion. I feel really confident about what I’ve heard from city officials so far.”

having a firearm without a valid license is a fine and a maximum of seven years in prison.

These policies were all implemented with the safety of students in mind

“I’m on the City Benefits Reimagining Public Safety Committee,” says Papachristos. “People don’t feel safe, so they’re going to do stuff to protect themselves, and one of the things they do is they’re going to carry weapons. So everything should be done with that kind of sense in mind. But the most important thing I would say is you want students to feel safe. The key is you need people to feel safe. There’s not one particular thing that can be done, whether it’s just more security, or whatever; it won’t work on its own. I don’t know what I would do if I was running a school with [4,000 students.] That’s not even a question I’m going to try and answer.” ***

After the death of Hoffman in 1997, students at ETHS took action. On Monday, June 9, the call of the wards occurred. The call of the wards is a forum in which council members may raise various issues affecting the community. It is an opportunity for the Evanston community to come together and speak out about difficult topics. There was one major topic on everyone’s minds that night, the murder of Hoffman just four days before.

At 8:00 am, bright and early, H-Hall is already flooded with students; groups with their heads together crowded in the lobby, down and up the stairs, lingering in front of lockers and classroom doorways. Who is it that greets them as they enter through Entrance One? Who is posted outside the main office and all throughout the building, in their blue and bright orange uniforms? ETHS’ safety officers.

The safety department at ETHS has a lot on their shoulders—from dealing with spats in the North Wing to reports of weapons or drug use, and overall keeping everyone in and around the building safe. Often, students can be intimidated by safety staff, since they’re the ones who step in when kids are violating school rules or when dangerous situations break out. But there’s more to them than keeping order, of course.

Necus Mayne is a safety officer and an alumni of ETHS. He’s worked as a safety officer for 10 years, monitoring the halls from North to South to East wing. Most of the safety officers actually graduated from ETHS, Mayne says—as many as 75 to 80 percent of the staff.

“It means a little bit more for us when we come back to give back to the same school we graduated,” he says. “We take a lot of pride in our jobs, and a lot of pride in trying to help these kids navigate throughout the building.”

ETHS, like all schools, has had its fair share of difficulties, ranging from mere hallway fights to situations as intense as last year’s lockdown. But though there will always be students who don’t follow the regulations set in place, Mayne believes that the students and staff here care about keeping the school safe.

“For the most part, I have faith in the majority of the kids that go here to make the right decisions. Now, we understand kids make mistakes, and part of being an adult is trying to model for them how to kind of rebound from those mistakes,” he says. “[But] I think it’s a community job to keep schools safe. It doesn’t just come from the safety department. It comes from the students, it comes from the teachers.”

While it may take everyone that is a part of the school community to keep ETHS safe, safety officers are the ones who have to physically

deal with rule violations. They are certified in CPR, CPI (non-violent crisis prevention) and AED through the American Red Cross, as well as FEMA-certified for crisis management. For any type of crisis de-escalation, especially when it’s physical, they’re prepared. But they never intervene in a fight without multiple units present and only after they’ve given verbal cues, Mayne discloses.

“I feel like usually when I speak, kids listen,” Mayne says. “But protocol is, you don’t intervene in a fight unless there are multiple units there to assist to basically restrain whoever the parties are.”

But the safety officers do more than just break up fights and monitor the hallways. They greet students at the doors every morning, scan their IDs at lunch, help track down their lost or stolen items and generally make an effort to connect with the student body.

“[A lot of] the safety officers are very friendly and talk with students,” one student shares. “They break up fights, but they also help students to class. They look out for all of [us].”

As much as the safety officers do for this school, though, there are some things that are left in the hands of higher authority. When it comes to dealing with the bigger issues, like reports of a weapon or a lockdown, the EPD (Evanston Police Department) assists and guides the safety department. But because there are two SROs (School Resource Officers) on campus, they’re often already on the scene before the safety officers.

“I personally have not found any [items that violate school code,] but obviously, I have co-workers, if we do find something like that, we don’t touch it. We leave it for [the] EPD,” Mayne says. “If the tip is that the most extreme weapon is in the building, then the SROs are going to be involved.”

But when it comes to reports of drugs or a physical fight in the hallway, the safety officers take charge in those situations. During instances like basic searches because of a marijuana smell or a fight, an SRO might not be involved right away. In cases like that, the safety officers take the lead. While Mayne does believe that ETHS is a safe school, part of being a safety officer is always being prepared for the worst-case scenario or something to happen at the school. They

have to be able to adapt to any situation, with the people’s safety in mind more than anything.

“Obviously from a safety standpoint, we’re always on our toes. You have to always expect the unexpected. That’s just a part of the job,” he says. “Anything could happen, anywhere, [on] any given day. That’s got to be the approach for someone in the safety department.”

Mayne makes it clear, though, that safety isn’t in the position to reprimand students or hand out punishment; more than anything, their job is to ensure the student’s, and faculty’s, safety. Even if they’re the ones who go directly into the situations, they don’t partake in disciplinary action.

“Honestly, when we look at our jobs, we don’t have consequences or discipline,” Mayne voices. “That’s not our job; that really comes from the dean’s office. We look at our jobs mostly as being mentors and providing guidance to the kids that we can get through [to] on a daily basis.”

Many students can attest to feeling that guidance.

“I think it’s important for the safety officers to have this type of relationship with students,”

one says. “It shows that safety officers are here to help [kids], not intimidate or penalize them.”

Of course, lots of students may not see that side. When they’re in the dean’s office because a safety officer found them violating school conduct, they may not recognize that they’re doing their job, but as the ones to rat them out to the administrators. Mayne understands the latter perspective but thinks it’s misguided.

“There’s a misconception about the department and what our jobs are like,” Mayne says. “We all have a vested interest in the success of our students. And I think it’s hard sometimes for a teenager to grasp that concept. When we come in, we might look like the bad guys. You know what I’m saying?”

“[But] we’re just doing our jobs. We want to make sure that everyone is safe,” he continues. “We have to step in and we [have] to make sure that that student gets help.”

On Sept. 23, East Dundee Deputy Police Chief Schenita Stewart was announced as the new Evanston Police Chief. Stewart, an Evanston native and ETHS graduate, is the first fulltime police chief since Demitrous Cook retired on June 7, 2021. She steps into a department that is under constant scrutiny from the Evanston community, which has a vocal anti-policing faction. In spite of the criticism, Stewart is ready to get to work.

“It’s a great challenge, but I’m very optimistic that we’re going to be able to do some good things here within the city limits,” she says.

Stewart has spent 23 years in law enforcement, including 15 years in police leadership roles. As an ETHS student, she played on the girls varsity basketball team and, to this day, takes pride in her playing career. In her new role, Stewart emphasizes that she will lead as a longtime Evanston resident first and a police chief second.

As I sat down to interview her, she stressed her humanity over her status. “I don’t know how you’re going to view me after this, but you may not view me as the chief of police, right? You may just view me as Schenita: someone that went to ETHS and is an Evanstonian just like you, and that’s what’s important to me,” Stewart highlights.

She brings this mentality in the face of police violence that has ravaged the country. According to the Washington Post, over 1,000 Americans have been killed by police in 2022 alone. Additionally, Black Americans have been killed at over twice the rate of white Americans since 2015.

In Evanston, the police department faces questions about over-policing in Black and brown neighborhoods. For example, in 2018, a 44-yearold Black man named Ronald Louden was bar-

bequing for family and friends in a parking lot in Evanston. Body camera footage shows police approaching him, tasing him and shoving him face-first to the ground. They allegedly provided no explanation for their presence. Louden said he couldn’t breath and he feared for his life. Ultimately, he pleaded guilty to a weapon’s charge, although the weapon was in the car.

The Louden incident shows, in the context of the 2020 police killings of George Floyd and Brianna Taylor, that Evanston is far from immune to the police brutality that has rocked the country for decades.

As Stewart works to build trust in the community, she acknowledges that over-policing is problematic. She emphasizes “getting away from … arresting people and giving people tickets. That’s not how you build a partnership with the community.”

She isn’t just speaking as a police officer; she’s speaking as a victim of the very same over-policing. “I still hold on to a negative encounter I had with a police officer when I was in the police academy,” she says. “I was driving back home in Evanston to my grandfather’s house, and I was pulled over and taken out of a car at gunpoint. That had a lasting effect on me. I can’t get rid of that.”

Another priority for Stewart is holding herself and Evanston Police Department officers accountable for their actions.

“I’m the chief of police. I have to own [tensions with the community]. I won’t blame that on anybody. It’s up to me to change it, so when I don’t, you should come back to me and say ‘You’re the chief of police; what’s going on with your partnerships?’”

Stewart believes that this self-awareness will be the key to executing on her vision for a more personable and communicative police department. She also believes that her mentality will

help officers connect with youth, expressing that youth outreach is an area in the police department that was lacking under previous chiefs, but it’s an issue that she will prioritize.

Internally, Stewart will accomplish her goals by promoting the officers who “embody community policing and procedural justice.” She also plans to create a Spanish-speaking Police Academy in conjunction with the Hispanic and Latinx officers in the department.

Overall, this job is close to Stewart’s heart. Understanding the role of police and combating violence in and around Evanston is a personal issue, not just because she grew up in Evanston, but also because violence is an issue that continues to affect her life.

“Since I was 17 years old, I’ve been dealing with gun violence ... But recently, my nephew’s son, a five-year old, was murdered in Rogers Park. I’m always trying to work as a chief to make sure we establish the right protocol, the right people to try to deter as many incidents as possible.”

This is Stewart’s mission: she exudes warmth and kindness, carrying a passion for building a connection and mutual trust with the Evanston community.

“It’d be naive of me to say, ‘You know what? We do great.’ We don’t. We can do better in any partnership, and I have to be humble enough to know that and work on that.”

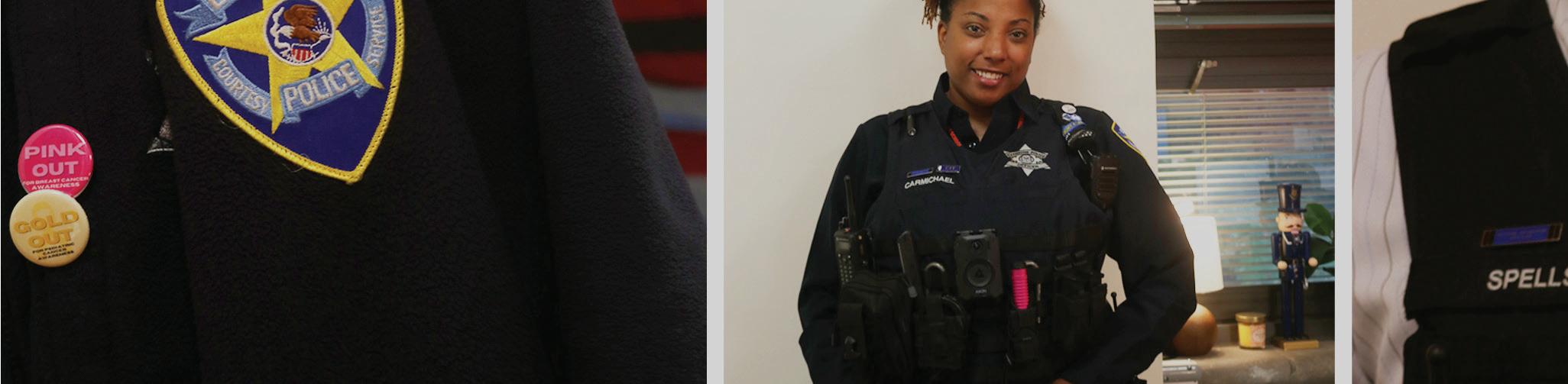

During sixth period on one Wednesday afternoon, I walk into the School Resource Officers’ (SRO) office on the first floor of the North wing. I am greeted by two people, broad smiles on their faces, welcoming me to take a seat. The chair is plush and comfortable. Two desks sit next to a coffee machine, with a bowl of leftover Halloween candy by the door. A large orange wall towers over the rest of the office, a stark contrast from the beige classrooms that ETHS students are used to. For the next 20 minutes, we discuss everything from school spirit to horror movies. This interaction and this office is everything that SRO Loyce Spells wants police at ETHS to represent. Alongside the other SRO at ETHS, Officer Grace Carmichael, Spells believes in establishing connections, building trust, and having dialogue with students.

“The bulk of our work is in the counselor, mentor role,” Spells says. “Not to say that we’re not busy doing the law enforcement side of things, because we are, trust me, but we are very intentional about building relationships and being a presence, a positive presence.”

SROs were first employed in Evanston schools in 1966, and their prevalence in schools across the country has grown in the last 50 years. In 1975, as the Center for Education Policy Analysis reports, Evanston was in the one percent of schools that reported having SROs. By 2018, 58 percent of schools across the U.S. had SROs patrolling their campuses.

The purpose of these officers is to provide defense against external threats like school shooters. However, the City of Evanston emphasizes the specific need for SROs to be available and accessible to students.

According to the Evanston city government, “All School Resource Officers (SROs) are appropriately vetted, trained and guided by clear policy in order to cultivate relationships of mutual respect and understanding, and foster a safe, supportive and positive learning environment for students.”

Notably, SROs at ETHS are funded by the Evanston Police Department. This is contrary to most other SRO programs, which are paid for by the school. The uniqueness of this situation matters because many conversations nationally about SROs are framed around the investment that a school is making into police. In this case, however, ETHS isn’t paying a cent, making the presence of SROs much more appealing to school administrators.

For Officer Spells, it doesn’t matter who funds his position. He firmly believes in his mission as an SRO and as an ETHS community member. Spells has been in the Evanston Police Depart-

ment for 20 years. He has seen police departments across the country criticized for their frequent violence against black people. He has seen his own department called into question as well, especially in the aftermath of the 2020 shooting of George Floyd. He has seen protesters take to the streets; some simply protesting to stop the violence, with others shouting that “All cops are bastards,” and calling for the defunding or abolishment of the police.

In light of all this, Spells goes back to his roots. Growing up as a black man in America, Spells was far from immune to racist police officers. “The majority, if not all, of my encounters with law enforcement personally or through family and friends from six or seven years of age were bad. So I grew up despising law enforcement,” Spells explains. “It actually fuels what I do today. It guides me to be the officer that I never saw growing up.”

Spells sees working at ETHS as an opportunity to change the negative perception that Evanston youth have of the police; a perception that they may carry with them for the rest of their lives.

Additionally, Spells is working on a couple of changes to bring SROs closer to the student body. First, he hopes to add the decals of ETHS sports teams to the back of the SROs’ squad cars. Spells is also in the process of changing his dress code from the usual blue police uniform to less formal attire underneath the usual bulletproof vest.

While these may seem like small changes, Spells believes in the importance of integrating SROs into school culture. “The blue uniform and the uniform in general sends this inadvertent message that ‘You’re not a part of us. You’re an outsider,’ as opposed , ‘If you are part of us, you’re one of many in this community.’”

Spells wants police officers to be humanized and not alienated. He wants connections to be genuine and not forced. And he wants to be a resource, not a burden.

“I really believe that you have two very good SROs at the school,” says Evanston Police Chief Schenita Stewart, who was appointed in late September. “And I think it’s important to clarify that because, in the past and in other agencies I know of, they’ve put [the role of SRO] off to get [bad officers] off the street.”

Chief Stewart brings up an important point about the credibility of SROs: some police departments assign their least trusted officers to work in schools. Therefore, instead of doing extensive and necessary training on how to properly interact with students, officers are thrown into schools, essentially as a punishment. This offers a semi-explanation for the viral stories and videos of police harming students in schools. Stories

like the one of Brian, an 11th grader in Philadelphia who had an argument with an SRO about using the bathroom without a pass. The disagreement resulted in the officer throwing Brian to the ground and putting him in a chokehold.

Spells believes that isolated incidents shouldn’t define his role at ETHS. “Are there people who have bad encounters with law enforcement? Understood. But the presence of Loyce Spells, the presence of Officer Grace Carmichael, is not causing harm to anyone.”

Spells’ reaction to those incidents only solidifies his belief in the function of SROs. However, while he sees the benefit of his presence at ETHS, others don’t. Many Evanstonians consider SROs as a threat to the student body, doing more harm than good. This sentiment is exemplified in the work of the Moran Center, an Evanston youth advocacy non-profit and outspoken opposer of SROs.

In a study published in 2020, the Moran Center layed out their argument for removing SROs from ETHS. “When armed law-enforcement officers or SROs are employed in a full-time capacity on-campus, they inevitably become involved in situations where their involvement is unwarranted and causes matters to escalate unnecessarily,” the study says.

This rationalization brings up another crucial factor in the conversations around SROs: the school-to-prison pipeline. The Moran Center argues that the presence of police at ETHS directly results in more arrests, which sends teenagers into the criminal justice system. They say that students at schools with SROs are much more likely to be arrested for discretionary criminal violations like disorderly conduct or battery than schools without SROs.

Furthermore, the study questions the main purpose of SROs, which the ETHS website says is to “protect students and staff from external threats, such as a school shooter on campus.”

“While many school districts have created and maintained SRO programs to address [external threats], the hard truth is that there is no research or data establishing that SROs make schools safer or play a role in preventing school violence,” the study declared.

This is a big talking point for people that oppose the presence of SROs and anti-SRO people who don’t see any reason for police to be in school. It also is an uncomfortable truth for the students and staff who want to feel safe in the case of a shooting at the school.

The ETHS community is especially wary of guns as the school arrives at the one-year anniversary of last year’s lockdown. That fateful morning, ETHS students and staff hid in corners of dark rooms, awaiting and dreading who might

come through the door next. I sat in the corner of North Cafeteria, and I will not soon forget the silent tension and frightful whispers as we tried to figure out what was going on. We watched as police officers with automatic weapons patrolled the halls and the exterior of the school. It felt dystopian, surreal and absolutely terrifying. And finally, after several hours of tense silence, we were sent home. I had never been closer to the reality of school shootings.

Since then, there have been a series of violent tragedies across the country. It has been seven months since the Uvaldi, Texas shooting that killed 19 elementary school students and two teachers. It has been over five months since the July 4 shooting that killed seven people less than 30 minutes from Evanston households.

Violence in schools and across communities has instilled fear in children and adults alike.

Young students practice lockdown drills before they know how to do multiplication, and parents can’t even guarantee that their child will come home at the end of the school day. Furthermore, to this point, there has been no sufficient response to this violence. Parents and guardians would love to believe that SROs are protecting their children, but as the Moran Center says, they can’t promise students safety from an external threat.

So, if it’s proven that SROs won’t prevent a shooting, is there any benefit to having them at ETHS in the context of guns and outside threats?

Chief Stewart believes so. “There have been a few incidents of weapons being recovered on school grounds…if this was a situation where there weren’t firearms recovered, I would say, ‘Maybe we don’t need SROs.’ But I don’t think we’re at that stage yet,” Stewart says.

The way Stewart sees it, SROs are necessary in a school that has had multiple guns found on campus in the past year. She cites a situation just a few weeks ago when a student was found with a gun shortly after the school day ended. Those are the situations, she says, that an SRO is needed in.

However, Stewart sees a world where SROs might not be necessary at ETHS. As a longtime Black Evanston resident and ETHS alum, Stewart understands what it’s like to be at ETHS in the presence of police. Much like Spells, she has had scary encounters with police over the course of her life. Because of that, Stewart is not naive about the inherent dangers of policing in schools. For now, though, Stewart is pleased to have passionate officers in the school.

While many rave about the ETHS SROs, it doesn’t address the broader problem that the country has with policing in schools. However, Spells has a vision for how to combat those issues. He wants to put an end to police department practices that put the least trusted officers in schools. He wants universal training to prepare officers to work in a school. And most importantly, he wants passionate SROs like himself, who care about the students that they interact with every day.

For Spells, the key is that “you prepare [SROs] to succeed in that role. It’s not just that you hope that they will. It’s that the police department and the city along with the school district work together to prepare the SROs to succeed.”

Overall, the Moran Center and other advocates from removing SROs raise major concerns about the importance and effectiveness of SROs. And as the discussion around police remains a heated issue, the best thing that Evanston police can do is stay focused on the connections that they make and the community that they build.

As Chief Stewart steps into her new role, that community is her number one priority. “The understanding that our actions when we wear this uniform can not only affect one person,” Stewart says, “but a family or generations of people that think a certain way. And that is the day-to-day contact and respect [that] we have to build back.”

Hoffman’s killing was a series in a larger portion of events, featuring the killing of Andrew Young, as well as Ronald Walker II, both former or current ETHS students. The butchering of Hoffman provided a spark for students around the school. They organized a rally against violence, which took place on the anniversary of the

slaying of Young. Around 100 people gathered along Dodge Avenue to make their opinions known and memorialize the late Hoffman.

To make sure their voices were heard and that no change would be left to chance, the students leading the rally presented a “Petition Against Violence” at the call of the wards. The petition was signed by more than 75 people, and praised by Fourth Ward Alderman Steve Bernstein.

The petition read, “We, the students of Evanston Township High School, demand action from those with the power to make changes. We demand the creation of a plan which will stop the senseless violence which has engulfed our community.”

“They issued us a challenge,” said Bernstein at the meeting, “We’ve been grappling with this problem for [20 years] and nobody has come up

with a solution. What I think we must do—and we must not wait a minute longer—is to declare a war on violence in this city. I don’t have any of the answers, but I think it’s incumbent on us as a City Council to come up with these answers.”

25 years later, Evanston is dealing with the same problems and trying to come up with answers.

Attempting to buck criticism of police, school’s SROs build trust, serve as mentorsPhotos by Aaliya Weheliye, collage by Clara Gustafson, Ahania Soni, Aaliya Weheliye

Teachers are vital to school safety. From the reassuring gestures given before unit tests to the warm “hellos’’ uttered in between passing periods, educators help students feel safe and seen in a space that has historically reinforced violence, control and fear. Because of teachers’ lived experiences as both students and educators, they hold wisdom that must be taken into account when discussing school safety.

“I grew up during a time where I witnessed [some of the first] mass school shootings. I was in sixth grade when Columbine happened, and I remember coming home from school and watching the news and seeing kids running out of lunch. I was like, ‘What is going on? How could this happen?’ [It] felt so strange to see students bringing guns into schools, and then to see students [being] murdered in school. It was such a strange reality for me to navigate. [When I became] a teacher at ETHS, there was a lockdown drill within three weeks of my first year. [So,] from that time I was in sixth grade to my time as high school history teacher, I’ve understood what those dynamics are. I’ve had this really interesting journey [with safety in school],” says ETHS History teacher Corey Winchester.

Winchester is currently taking a leave of absence to pursue his PhD in Learning Sciences at Northwestern University. In previous years, he has taught United States History and Sociology of Class, Gender and Race. Outside of the classroom, Winchester has served as the staff coordinator of Students Organized Against Racism (SOAR) since 2012. With such an extensive background at ETHS, he has experienced several aspects of the school’s culture. In fact, one of Winchester’s first memories of ETHS related to safety in school.

“In my first year [teaching] I was given a [history] textbook called The Americans. It’s a textbook that students typically receive if they take United States History honors. So I start flipping through the pages, and I get to a section in the back of the book that’s about new issues in the 21st century. And the topic is school safety. There’s a picture of my neighborhood high school in [Philadelphia,] called Bartram High School, of Black students walking through metal detectors. The conversation was about school safety, but with a firm focus on an inner-city school with predominantly students of color,” he says.

Winchester underscores a pertinent aspect of conversations surrounding physical safety in school. Like textbooks, many Americans perceive that gun violence is an issue that students solely in urban settings experience. This not only perpetuates myths that gun violence disproportionately occurs in areas where higher populations of Black and brown students live, but it is also factually incorrect. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, of the 318 school shootings committed between 2009-2019, 140 occurred in urban areas, 80 in suburban areas, 50 in rural areas, 48 in towns and 21 couldn’t be matched. Meaning, less than half of the total school shootings occurred in urban settings.

“School safety [has] been mythologized as an issue that we see only kids in urban settings experiencing, but [students in suburban and rural areas also] have to negotiate this reality where folks are bringing in guns in schools,” Winchester explains.

Regardless of where a school is located, it is imperative that all educational institutions enforce measures to protect students from guns without making them feel like highly surveilled spaces.

“Navigating around [vio-

lence] has been fairly normal in schools. [But] what was very different was how schools institutionally responded to those threats of violence. [Some schools responded] by installing metal detectors or increasing police presence in schools. [As a result,] schools then slowly became a highly surveillanced space. And that was a transition that I witnessed throughout my schooling. So from sixth grade to when I graduated high school, these were some of the things, like going through metal detectors, [that] made school feel like I was walking through the airport.”

Winchester attributes schools’ increased surveillance to 9/11, in which the federal government responded to al Qaeda’s terrorist attacks by developing an extensive security framework. Consequently, this affected how public spaces, including schools, were po-

Jim Crow is a sociological text depicting the legacy of mass-incarceration in the U.S., a criminal justice system spawned by profound inequities created after the abolition of slavery, including Jim Crow laws and the War on Drugs. Unfortunately, as our nation’s criminal justice system expanded to hold more prisoners, our schools transformed with it. National concerns about crime and discipline led schools to adopt more punitive policies, resulting in the funneling of students into the carceral system in a phenomenon called the “school-to-prison pipeline.” According to the ACLU, the school-to-prison pipeline is “a disturbing national trend wherein youth are funneled out of public schools and into the juvenile and criminal legal systems. Many of these youth are Black or brown, have disabilities, or histories of poverty, abuse, or neglect

“Why is it that when kids go to school, they have to learn how to protect themselves and operate from a place of fear? Also, why is there a conversation about arming teachers? I didn’t sign up [for that]. When I became an educator, I didn’t want to be a soldier or a police officer. That is not the work I wanted to do, and I’m not going to do that. We have to change how society functions, so that schools don’t become barriers of defense against the ills that society has placed upon it.”

liced.

“9/11 really changed the dynamic for how folks thought about safety and security in the nation. Because of the terrorist attacks, the way that the United States responded with things like the Patriot Act, the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security, and in the policing that happened in multiple contexts, from airport security to increased security and government buildings, all that also was happening at the same time. So we’ve seen this hyper policing of public spaces that I also think is important historical context to add in . . . So there’s been this trajectory of surveillance and policing public spaces. Schools, unfortunately, given the fact that we do live in a violent society, were also a place where that has happened.”

Like Winchester describes, schools in the modern era are surveilled similarly to public fora. But as schools across the country tighten their safety procedures through the inclusion of things like automated locks, metal detectors, high-depth cameras and School Resource Officers (SRO’s) new problems arise: when safety measures increase, discipline often proliferates, too.

“When Michelle Alexander, who wrote The New Jim Crow, came to Evanston like a decade ago, she [talked about how] there are two institutions that criminalize in Evanston: the police department and our school systems. And there’s something to be said about that. I think what this requires is for us to really think about discipline differently.”

As referenced above, The

and would benefit from additional support and resources. Instead, they are isolated, punished and pushed out.”

Winchester expands on this concept, highlighting the dramatic effect punishment and discipline has on students’ futures if they are convicted of a crime during high school.

“There’s two places [where students] get in trouble on some type of permanent file record. It’s [with our] schools, and it’s with our police. That has implications if you’re in school, and you’re looking to apply to colleges, trade schools and jobs. In that respect, how we police in schools also mirrors how folks are policed and criminalized in real life. If you’re convicted of a crime, and you’re applying for jobs that [record] has implications on job applications . . . It has implications on access period.”

As schools navigate discipline and the criminalization of youth, an important question must be asked: how are students emotionally impacted by punitive policies? When students feel that they can’t fully express their identities from policies that regulate how they physically show up, it affects their sense of emotional security. According to Winchester, these were the circumstances that led ETHS to remove the dress code in 2016.

“[Students not feeling like they could express their identities fully] is one of the things that led us to get rid of the

dress code policy. School safety doesn’t just look like police presence in school, but it’s also how we put in laws. In high school, we have policies or rules [that decide] what kids can and can’t do. And some of that was coming down to how students’ bodies were being received by folks. And if you look at it [from a racialized lens], mostly Black and brown kids were policed more than white students based on what they were wearing,” he says. “Part of the dress code policy said that you couldn’t wear hats in the buildings, and that was something that impacted black males. And [that’s] not to say that other folks didn’t wear hats in the building. But the kids who were disproportionately told to take off their hats were Black male students. White male students and white female students also wore hats but they weren’t being policed for it in the same way. That’s just one example of how people’s identities are associated with particular actions, particular clothing items. We begin to racialize how people are showing up. And that’s a problem.”

The racialization of clothing can impact students in macro ways.

“In school spaces, we don’t always have the opportunity to express our identities fully. For example, we witnessed how ETHS policed bodies during graduation. I think most folks are aware that the administration didn’t let an indigenous student walk during graduation because he wore an important religious symbol of his culture.”

Winchester is referencing last year’s graduation where senior Nimkii Curley did not receive his diploma on commencement day for embroidering his cap with traditional Ojibwe floral beadwork and an eagle feather. According to the Evanston Roundtable, the eagle feather “is sacred and used for prayer. [It] represents generational respect, continuity and responsibility to one’s community.” For these reasons, when event coordinators and safety personnel asked him to remove his cap because ETHS does not allow students to modify their caps and gowns, he refused. As a result, Curley was directed to sit in the bleachers with his family until the ceremony ended.

“[A] safe school wouldn’t create those types of violence,” Winchester says, finishing his thoughts about anti-indigenous actions at ETHS.

For him, schools have a long way to go to become safe environments both physically and emotionally. But in the absence of equitable, safe schooling, teachers and students have curated meaningful relationships to move beyond an institution that historically dehumanizes.

“At the end of the day,” Winchester concludes, “your human connection to me is on a human level, as opposed to a level that’s predicated on power. So teachers and students, we’re doing this work in a way that is based on relational trust. Understanding one another’s humanity [is about] seeing each other as equals in a level of respect towards one another’s experiences . . . If we began to make sure that our laws actually reflected some of these human relations that we have with one another, [we’d begin to approach safety with a more humanizing lens]. But until we examine power, and understand how power is used as a tool for dehumanization, we can’t make power work in ways where we exist in humanizing relations with one another.”

History teacher, SOAR coordinator talks school safety, the dangers of increased security, school-to-prison pipeline

The United States has the largest prison population in the world, with nearly one out of every 100 people in America behind bars. This is primarily due to unfair laws and practices that were created to put large numbers of Black people in prison. These laws and practices have been implemented in America since the end of the Civil War and have dramatically increased the prison population and damaged Black communities. This practice of locking up an enormous percent of our population, specifically from Black communities, is called mass incarceration, and it’s one of the most important issues that America faces. Ava DuVernay’s award-winning documentary, 13th, shines a light on the historical and political background of mass incarceration.

According to 13th, the history of mass incarceration has its roots deep in American history. It began after the 13th amendment was passed in 1865, outlawing slavery in the United States. After slavery was abolished, the southern economy was destroyed and Black people were gaining freedom. White southerners’ wanted to rebuild

the southern economy and weaken Black communities, so they exploited a loophole in the 13th Amendment which allowed the slavery as punishment for a crime. They unfairly imprisoned an enormous number of innocent Black people who had recently been freed from slavery in order to re-enslave them and take away their newly gained freedom. Mass incarceration continued in the 20th century, further damaging Black communities. Actions taken by the federal government such as Presidents Nixon and Reagan’s “War on Drugs” was specifically created to lock up even larger numbers of Black people. Laws introduced by the Clinton administration, such as the 1994 Crime Bill and the Three-strikes Law, further exacerbated this problem. Mass incarceration remains an important issue in this country, as shown by America only having five percent of the world’s population, yet 25 percent of the world’s prison population. And our justice system still targets Black communities, with one out of every three Black boys today expected to go to prison in their lifetime.

Mass incarceration is also fueled by the school-to-prison pipeline, a pattern seen in many public schools wherein primarily Black students

are funneled directly from school into the prison system. Although Black students only make up 16 percent of students enrolled in public school, 31 percent of all school-related arrests are of Black students. Detail on this topic is given in Anna Deavere Smith’s movie, Notes From the Field. The movie explains how much of the time this happens due to a failure to provide enough mental health support in schools. Many students in public schools, especially Black students, deal with trauma that can impair them academically, socially and emotionally. Acting out is often a result of this trauma, but instead of helping students deal with their trauma, schools usually punish these students through suspension, expulsion, or by sending them to jail.