30 minute read

Jóvenes para siempre Forever Young

by EXIT

Every so often in the art world a classic lost work is discovered. Most of these long-ignored pieces were the work of great artists in their youth. They might be drawings by Goya, a portrait sketch by Rembrandt, papers, a canvas or a board even. They are small treasures that the deep-sea fish that is time has nibbled away at, unfinished works, mere outlines that would ordinarily be of little value but which are priceless and command record sums at auction, awakening not so much the interest of a public yearning for surprise and novelty (provided that it hails from the past), but of experts, who find in these early works the hand, the gaze and the themes that the artist went on to develop in their later years. They are clues, footprints that lead us to the real treasure, to the museum. These works mark the start of the creative journeys of the grand masters of art history, small masterpieces of no great importance at the time of their creation, pieces designed for honing and learning a craft. Contained in each of them is the fresh breath of an ephemeral youth made eternal by the line of the drawing, the shading of a face, the internal structure. These are the early pieces created by geniuses when they were mere adolescents. They inspire admiration in us and reveal to us the interests of artists who later became instantly recognisable. They show us how they started out. Along with the lines and colour of the drawing, they all contain something more on their surface: a type of magic, a trace of a hand and breath engraved in the surface, something of the gaze of a young artist not yet aware of the greatness that awaited them.

Cada cierto tiempo el mundo del arte descubre o recupera una obra desaparecida, ignorada, del arte clásico. La mayoría de las veces se trata de obras de juventud de artistas de renombre: unos dibujos de Goya, un boceto de un retrato de Rembrandt, papeles, algún lienzo, una pequeña tabla. Son como pequeños tesoros carcomidos por los peces del fondo abisal del tiempo, obras inacabadas, apuntes, que por sí mismos suelen tener escaso valor, pero… pero son piezas de un valor incalculable, récords en subastas, que despiertan el interés no ya de un público ansioso de sorpresas y de novedades (siempre que estas vengan del pasado), sino sobre todo de los especialistas, que descubren en ellas, en esos inicios, la mano, la mirada, los temas que desarrollaría ese artista en su madurez. Son indicios, las huellas que nos han de llevar al tesoro real, al museo. Son las obras que iniciaron el camino creativo de los grandes maestros de la historia, pequeñas óperas primas que no tuvieron mayor importancia en su momento, piezas de entrenamiento, de aprendizaje. Pero cada una de ellas guarda en su interior un soplo fresco de una juventud pasada temporalmente, pero eterna en la línea de un dibujo, en el sombreado del rostro, en la estructura interna. Son las primeras que hicieron esos genios de la historia del arte cuando solo eran apenas unos adolescentes. Nos inspiran admiración y nos informan de cuáles fueron sus intereses, de cómo empezaron a ser quienes luego reconoceremos. Todos ellos guardan en su superficie, junto con la línea y el color del dibujo, algo más: una suerte de magia, de algo que la mano y su aliento han dejado grabado en su superficie, la huella de la mirada del joven artista que no tenía conocimiento aún de lo grande que sería.

Hoy el tiempo va demasiado rápido y, si en el pasado un movimiento estético duraba varios siglos y se mezclaba con otros en sus inicios y en sus últimas bocanadas, hoy las tendencias, las corrientes, los “ismos”, son como las temporadas otoño y primavera de las firmas de moda; cambian de tal forma que el ayer se tiene que dejar atrás a toda velocidad para dejar espacio a un breve hoy.

Time goes by too fast these days. Whereas the aesthetic movements of the past lasted several centuries and fused with others in their beginnings and their dying gasps, the trends, currents and -isms of today are akin to a fashion house’s autumn and spring seasons. Such is the pace of change, that they are abandoned with great haste to make way for their successors. Nor do we look back with eyes wide open, choosing instead to charge headlong into the future, to nowhere in particular. In this endless race, artists have no youth to speak of, or perhaps youth is all they have, in that that they seem to reach us as end products with all updates already installed. Over the years, however, there has been a growing interest in recovering the early works of the most contemporary artists. The one difference is that they are not to be found abandoned in dusty attics, though we might just come across them in a flea market.

Y no miramos atrás con una mirada abierta, más bien parece que huimos hacia adelante, hacia ningún lado. En esa carrera interminable, los artistas apenas tienen juventud. O tal vez solo puedan tener juventud. Parece que ya vienen de fábrica en perfectas condiciones y con todas las actualizaciones al día. Sin embargo, de un tiempo a esta parte se observa un creciente interés por la recuperación de las primeras obras de los artistas más actuales. Claro que ya no se trata de obras que aparezcan abandonadas en antiguos desvanes, ni cosas así. Tal vez en algún mercadillo.

Desde Picasso, todo artista que se precie de serlo sabe que debe guardar hasta las servilletas de los bares y los cuadernos de apuntes. No se desecha nada, todo se cataloga, se fotografía y se guarda, esperando que, en no demasiado tiempo (por supuesto aún en vida del artista), este trozo de un pasado intermitente valga en el mercado una cifra maravillosa y sea incluido en las retrospectivas en museos, donde, por primera vez, se verá cara a cara con un público real. Y así sucede en las retrospectivas y muestras antológicas, pero también cada vez más en las galerías más importantes (esos nuevos y auténticos museos de arte contemporáneo), donde nos encontramos con esas primeras obras, a veces incluso inocentes, de artistas esenciales de la historia del arte del futuro, los nombres que han cambiado nuestra forma de entender el mundo, que han marcado las coordenadas de cómo vernos a nosotros mismos y situarnos en la sociedad actual.

Se trata ya no de una ópera prima en el sentido estricto, ya que todos sabemos que esa primera obra es la última de toda una serie de descartes, como esos papeles que acaban en la papelera y por el suelo del estudio del escritor antes de que este acabe su novela. Estas obras que nos devuelven al joven artista que está, con suerte, aún dentro del artista maduro de hoy, son las primeras que el artista, o tal vez alguien cercano a él, consideró lo suficientemente hecha para ser mostrada, guardada, considerada. Por suerte, en el arte actual, en el que prima la cultura, el conocimiento, la capacidad intelectual y la experiencia, más tal vez que en ninguna otra época anterior, ya no existen niños prodigio, así que lo que nos encontramos es siempre al adolescente, a una mujer o a un hombre joven aún, pero ya formado, que conoce el oficio y que ha visto mucho: museos, libros, revistas. En resumen, que ha perdido la inocencia junto con la virginidad hace ya unos años. Esa circunstancia es importante, porque ya no hay sorpresas; sí hallazgos, y las huellas, los indicios que nos llevan a sus trabajos más recientes, están más frescos, son más evidentes.

Since the days of Picasso, any self-respecting artist knows they have to keep hold of everything down to their notebooks and the serviettes they dab their lips with in the local bar. Nothing is thrown away. Everything is catalogued, photographed and kept in the hope that, in the not too distant future (while the artist is still alive, of course), this remnant of an intermittent past is worth a mind-blowing amount of money on the market and is featured in museum retrospectives, where, for the first time, it comes face to face with a real audience. We see this at retrospectives, solo exhibitions, and increasingly at major galleries (these new and authentic museums of contemporary art), where we come across the first works – unknowingly created in some cases – of artists essential to the future of the history of art, the names that have altered the way we see the world, who have mapped out the coordinates of how we see and place ourselves in modern society. They are not first works in a strict sense. We all know they are the last in an entire series of discards, like the scrunched-up sheets of paper that writers toss in the bin or on the floor in the process of writing a novel. These works, which take us back to the young artist who hopefully still resides in the mature artist of today, are the first that they, or perhaps someone close to them, regarded as sufficiently complete to be exhibited, kept and considered. Fortunately, in today’s art – in which culture, knowledge, intellectual capacity and experience come before all else, more so perhaps than in any other period –there is no such thing as the child prodigy. What we are faced with instead is the adolescent, a woman or man who is still young but who has already learned their trade and seen a lot: museums, books, magazines. In short, they lost their innocence, along with their virginity, years ago. It’s an important point, because there are no such thing as surprises anymore. What we have are discoveries, traces and clues that lead us to their most recent work, their freshest, most obvious pieces.

Los fotógrafos vienen caracterizados de fábrica por la superabundancia de obra que generan allí por donde pasan. Superados unos inicios complicados, con el auge de las nuevas tecnologías que, en poco menos de un siglo, nos han llevado desde las horas de exposición en total inmovilidad hasta el uso de la Inteligencia Artificial (observen que en menos tiempo que los albores del primer Renacimiento, o los últimos coletazos del Barroco, por poner solo unos ejemplos), los fotógrafos en sentido estricto, aquellos profesionales de la imagen creada a través de una máquina (tanto los documentalistas como los de la fotografía directa, la callejera, la de moda, y todos los subgéneros que existen), han llenado nuestras retinas con millones de imágenes, en su mayoría con el mismo resultado que los millones de toneladas de plásticos que llenan los océanos

Photographers are known for the vast amount of work they produce. Having overcome challenging beginnings, they have given us millions of images to feast our eyes on, most of which have the same effect as the millions of tons of plastic that fill the oceans of our once-blue world. They have been able to do so thanks to the boom in new technologies, which, in the space of a century more or less, has taken us from exposure times of several hours to the emergence of AI, which is less time than that covered the dawn of the Early Renaissance or the last throes of the Baroque, to give but two examples. We are talking here about photographers in the strictest sense, experts who use a device to create images, both documentary makers and those who take photographs of the street, the fashion world and in every possible subgenre. But if we hack our way through the mass of photographers each de un mundo que fue azul. Pero si nos abrimos paso entre la selva de fotógrafos que hoy en día luchan por tener su fotolibro, llegamos al núcleo de la fotografía como una de las bellas artes. Si nos trasladamos al siglo pasado, a la década de los 70, encontraremos a esos artistas que, en su gran mayoría, no eran todavía artistas, sino estudiantes de Bellas Artes, estudiantes de pintura, de escultura, y de otras materias menos técnicas como estética o Historia del Arte. No eran fotógrafos, pero decidieron probar un nuevo lenguaje para hablar de cosas que aún no tenían forma en el mundo real, en nuestra sociedad. Imágenes, formas, situaciones, historias y conceptos, que ellos crearían. Pues, como artistas, las herramientas pueden ser todas y cualquiera, porque lo importante es lo que se construye con ellas, y lo que todos ellos han construido es una alteración transversal de la realidad, una forma de representar la realidad de maneras inimaginables para los fotógrafos tradicionales de ese momento. Inimaginables para todos nosotros, y de alguna manera también para ellos, que fueron descubriendo el fuego, desarrollando ese conocimiento transformador como un juguete maravilloso y milagroso que nos resitúa en un mundo diferente.

La importancia de la creación fotográfica en los cambios de la representación del arte es algo que todavía no se ha estudiado adecuadamente. El papel fundamental de algunos artistas, a través de la práctica fotográfica, no solo ha abierto caminos inimaginables en el vocabulario y temario artístico, sino que ha sido un reencuentro con el núcleo duro de la historia de la pintura y de la esencia del fighting to create their own book of photos, we come to the core of it all, to photography as a fine art. In venturing back to the 1970s, we come across artists who were by and large not yet artists but students of fine art, painting, sculpture and other less technical subjects, such as aesthetics and art history. Though not photographers, they decided to experiment with a new language to speak of things that had yet to take shape in the real world, in our society – the images, forms, situations, stories and concepts that they created. As artists, they could use any tool at their disposal, for what matters is what they created with them. And what they have all built is a transversely altered reality, a manner of representing reality in ways that were not just unimaginable to conventional photographers of the day and to us but to them as well. They were in the process of discovering fire, using and developing this transformational knowledge as an awe-inspiring, miraculous toy that relocates us to a different world. arte desde las pinturas rupestres hasta nuestros días. Esa transformación no se ha hecho desde la fotografía, sino desde el arte en su más pura definición. Ha sido hecha por una amplia generación de artistas que, en un momento determinado, decidió que la fotografía era el camino correcto para hacer ese trabajo. Y lo decidieron en un momento en el que eran apenas unos jóvenes desconocidos. Esa fue su ópera prima. Una primera obra que muchos de ellos siguen desarrollando, que otros han radicalizado y que alguno ha convertido en una costumbre. Posiblemente es ese un momento histórico doblemente importante en la historia del arte, no solamente por el cambio que imprime a su desarrollo, sino porque viene hecho por personas, hombres y mujeres muy jóvenes, sin obra anterior, cuyas primeras obras son, mirando desde hoy —una media de 40 años después—, firmes y rotundas, con un éxito prácticamente inmediato, y que han llenado con abundancia y diversidad la escena artística de este ya casi medio siglo. Por eso, la ópera prima de los fotógrafos de esa generación resulta tan enriquecedora. Son muchos los nombres, con edades con un margen de 40 años, como mucho, entre los maestros y los alumnos, entre Walker Evans y Cindy Sherman, o entre Bernd y Hilla Becher y Thomas Ruff, o algo más ajustado entre Andres Serrano y Sophie Calle. Pero son muchos, y rellenan todas las casillas de este puzle, en su diversidad. Tantos nombres, que es imposible nombrarlos a todos. Desde Francesco Jodice a Daniel Canogar, desde Karen Knorr a Robert Mapplethorpe, Gabriele Basilico, John Coplans, Stéphane Couturier, Louise Lawler, Nic Nicosia, Jörg

Not enough time has yet been spent studying the importance of photography in changing the way in which art is depicted. The fundamental role of artists who have engaged in photography has not only opened previously unimagined avenues in the themes and vocabulary of art, but has also led to a re-engaging with the hard core of the history of painting and the essence of art from cave paintings through to today. This transformation has not been fashioned by photography but by art in its purest sense. It has been made possible by a sizeable generation of artists who, in a given moment, decided that photography was the best way to do this job. And they chose to do so at a time when they were unknown youngsters. This was their debut work, which many of them continue to develop, while others have taken it to an extreme and some have made a habit of it. Potentially, it is a landmark moment in the history of art, not just for the change it has effected on its development, but because it has been fashioned by very young women and men with no body of work behind them, whose first works are, looking back at them today – an average of 40 years later – resolute, emphatic and enjoyed virtually instant success and which have filled the art scene for the best part of the last 50 years with abundance and diversity. That is why the debut works of that generation’s photographers are so enriching. There are many of them, with a gap of no more than 40 years between teachers

Sasse, Larry Sultan… Cada uno con una mirada analítica, diferente, radicalmente nueva y libre. Y, además, con unas primeras obras que aparecían en las ferias y en las galerías aún frescas, que iban abriendo la mente de cada generación, transformando las últimas décadas en un escenario artístico radicalmente diferente. Tal vez desde el estallido del conceptual no se ha vivido nada similar.

Las primeras obras de estos artistas, curiosamente —y en contra de todo lo que había ocurrido anteriormente en la historia del arte— son, en muchos casos, las más conocidas o unas de las más conocidas de todo su trabajo. Y en ocasiones también, con esa obsesión casi enfermiza que solo tiene el artista fotógrafo, esa ópera prima se sigue renovando, creciendo, modelándose durante toda su vida. Como en el caso de los Becher, de los que no se puede hablar de una serie de obras, sino de una sola obra desarrollada en series durante toda su vida creativa. Por eso, en muchos casos (especialmente los fotógrafos alemanes, pero no solo ellos), las series empiezan en la década de los 70 y siguen a través de las décadas, saltando años, dejándolas, retomándolas en paralelo con nuevas series. Pero no todos estos fotógrafos han trabajado en series, muchos son los que agrupan su producción simplemente por años. No importa, hablamos de una época en la que el propio uso de la fotografía frente a otros lenguajes clásicos y aceptados socialmente como obra de arte, mientras que la fotografía no lo era (y en cierto modo aún no lo acaba de ser), implicaba que la libertad era absoluta en forma, método o tema y en todas sus características expositivas. No solamente dejaron atrás los pequeños formatos y el blanco y negro como una cárcel de oscuridad, sino que lo recuperarían ellos mismos años después para dotarlo de otro sentido narrativo totalmente contrario al que había tenido históricamente.

Un caso especialmente importante y en ocasiones olvidado de ópera prima, y de prácticamente ópera única, es la obra de John Coplans, que hizo de su cuerpo no solo un campo de batalla, sino un radically different art scene. We have perhaps not seen its like since conceptualism burst on to the scene. and students, between Walker Evans and Cindy Sherman, or Bernd and Hilla Becher and Thomas Ruff, or a smaller gap between Andres Serrano and Sophie Calle. They are so diverse they that they complete every part of the puzzle, so numerous that it is impossible to name them all: from Francesco Jodice to Daniel Canogar, and from Karen Knorr to Robert Mapplethorpe, Gabriele Basilico, John Coplans, Stéphane Couturier, Louise Lawler, Nic Nicosia, Jörg Sasse, Larry Sultan et al. They each have a viewpoint that is analytical, different, radically new and free. And it is expressed in first works that were still fresh when they appeared in exhibitions and galleries, that opened the minds of each generation, turning the last few decades into a

Strangely enough, and in a reverse of the entire history of art up to that point, many of the debut pieces of these artists are the best known, or among the best known, of their entire oeuvre. On occasion, and out of that almost unhealthy obsession that only the photographer artist has, we also find that these works continue to renew, grow and shape themselves throughout their working lives. Such is true of the Bechers, who created not so much a series of works as a single work developed as a series during the course of their creative lives. Though a fine example, the German photographers are not unique. Many artists created series that began in the 70s and continued through the decades, skipping years in some cases, leaving them and then picking them up again at the same time as starting new series. Not all these photographers produced series, however. Many categorised their creative output by years, not that that really matters. We are talking about a period in which the very use of photography, as opposed to other classic languages socially accepted as art – which photography was not; something that remains true to a point today – implied that freedom was absolute in terms of form, method or theme and in all its exhibitory features. After dispensing with small formats and the prison of darkness that is black and white, they went back to it years later to lend it a narrative meaning totally at odds with what had gone before.

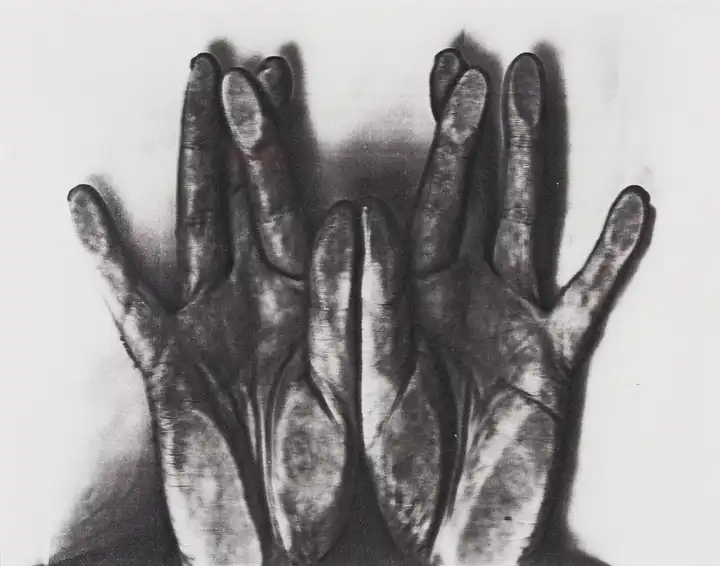

One especially important and occasionally forgotten debut work – one could argue that it is his only work – is that of John Coplans (1920-2003), who made both a battlefield and an exclusive photographic territorio fotográfico excluyente. Coplans (1920-2003) fue crítico, director de museo, escritor, comisario, uno de los fundadores de Artforum…, y a los 64 años, en los años 80 del siglo XX, dejó todo y se dedicó a la fotografía por completo. Solamente fotografiará su propio cuerpo desnudo, en fragmentos, detalladamente, sin ocultar su edad, en blanco y negro, en grandes tamaños. Una obra preciosista, única y personal, irrepetible, que nos obligó a repensar la idea de la representación del cuerpo, del desnudo y del autorretrato, de la edad, del paso del tiempo, de la autoría… La ópera prima de un hombre de 60 años que empezaba así una nueva etapa de su vida, que era nuevo, joven otra vez.

¿Qué buscamos en estas primeras obras de los que hoy son los fotógrafos más importantes? Posiblemente una forma de mirar diferente, un método de análisis de la realidad nuevo, subjetivo. Podemos definir básicamente dos tipologías de obras que, en su mayoría, se marcan desde el principio y se desarrollan y perfeccionan a lo largo del tiempo, pero también podemos ver cómo esas dos formas centrales se entrecruzan y se enriquecen, así como casos en los que se territory of his body. A critic, museum, writer, curator and one of the founders of the contemporary art magazine Artforum, Coplans gave it all up at the age of 64 to devote all his energies to photography. His only subject was his naked body, which he would photograph in fragments, in detail, without concealing its age, in black and white and in large format. It is an exquisite oeuvre, unique, personal and one of a kind, and it forces us to rethink the whole idea of the representation of the body, nudes and self-portraits, age, the passage of time, authorship, etc. It is the debut work of a sexagenarian embarking on a new stage in his life, made new and young again.

What do we look for in these early works of photographers who are now the utilizan indistintamente según los intereses. Y, en definitiva, cómo cada artista se apoya en aspectos muy diferentes que sí aparecen desde el principio como marca propia en sus trabajos iniciales, aunque con el tiempo la sofisticación formal pueda tapar esa esencia más naif característica de los primeros trabajos. Hay una clara línea de artistas que basan su obra en la mirada hacia el exterior: mira a su alrededor, observa incluso cómo su propia vida y sentimientos, sus experiencias más personales, rebotan en el mundo exterior, y eso es lo que centra su fotografía. Una especie de narración en la que siempre el propio artista es eje y centro. Su mirada lo justifica y, de alguna forma, años después, podremos ver a través de sus obras contada su propia vida. Y, a través de sus vidas y de sus experiencias, reconoceremos las nuestras, las de todos, veremos el paso de la vida por delante de nosotros.

Alberto García-Alix retrata su entorno desde sus inicios. Mirando a su alrededor retrata los lugares en los que vive, en los que duerme una noche, las calles por las que pasa, los bares, y especialmente a los amigos, los compañeros de viaje. Cambia el entorno, cambian los compañeros de viaje, aparecen otras ciudades, otros paisajes, la mirada se hace más triste, por momentos la alegría y el amor se desvanecen, pero se mantiene la amistad. La vida sigue. Nan Goldin ha construido toda su carrera hablándonos de ella misma, de su vida, de sus amigos y de su familia, de sus desengaños; sin embargo todos hemos visto nuestras propias vidas en sus imágenes. Ha retratado una época que no fue bonita, una vida de violencia cotidiana y de pérdidas, una vida vulgar como la mayoría de las vidas, biggest names in their field? Possibly a different way of looking at things, a method for analysing a new, subjective reality. We can essentially identify two types of works that, for the most part, are mapped out from the outset and are developed and perfected over time, though we can also see how these two central forms can interlink and feed off each other and how they are also used interchangeably, depending on the interests of the artist in question. In short, we also see how artists each rely on very different aspects that can be identified as a framework from the earliest stages of their output, although the formal sophistication they develop over time can conceal this more naïve essence, a feature of their early works. There is a clear line of artists who base their work on their outward gaze. They look around themselves and observe, even, how their lives, feelings and most personal experiences bounce off the outside world, which provides a focal point for their photography. It is a form of narration in which the artist is front and centre at all times. Their gaze justifies it and, in some way, we are able to see, years later, the stories of their lives told through their works. And it is through their lives and experiences that we recognise our own, the lives of everyone. We see life pass before our eyes.

Alberto García-Alix started out by capturing his surroundings, looking around and portraying the places in which he lives or spends the nights, the streets he walks through, the bars, and most of all his friends, his travel companions. The surroundings change, as do the travel companions, while other cities and landscapes appear. There is a growing sadness in his gaze, with happiness and love vanishing altogether at times, but the friendship remains and life goes on. Nan Goldin has spent her entire career talking just about that, about her life, friends and family, her disappointments. Despite it all, we have all seen our own lives in her images. She depicted a period that was in no way beautiful, a life of everyday violence and loss, an entirely unexceptional life – as most of them are – and turned it into a seminal artwork in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Created between 1979 y la ha convertido en una obra de arte seminal con su Balada de la dependencia sexual (The Ballad of Sexual Dependency) realizada entre 1979 y 1986, sin duda su obra más importante, y una de las primeras. Pero toda su obra posterior gira siempre en torno a ella como la protagonista que nos representa a todos. Incluso su primera película, triunfadora en la Bienal de Venecia de 2022, habla de su lucha contra el dolor, contra las drogas y contra las farmacéuticas; una lucha de miles de personas también, de toda una sociedad. Tanto Alberto García-Alix —cuyos últimos trabajos giran hacia el vídeo— como Nan Goldin —abiertamente dedicada casi en exclusiva al cine— trasladan sus experiencias de una forma ficcional (bien a través de la narración poética como de la “neoficción” documentalista) a la imagen en movimiento, dando un paso formal que atraviesa la fotografía para acercarse al cine.

En el nuevo documentalismo tenemos cientos de ejemplos de esta nueva creatividad y libertad a la hora de elegir el tema, pero lo que realmente les caracteriza es la forma en la que tratan dicho tema, cómo lo cotidiano y anodino se convierte en el centro. La idea es el tema. Lo que sucede sigue siendo el objetivo, pero puede ser contado de formas diferentes, en tiempos nuevos, retratar no un hecho and 1986, it is undoubtedly her most important work and one of the first. All her subsequent work revolves around her as the central character, an everywoman who represents all of us. Even her first film, a winner at the 2022 Venice Biennale, speaks of her fight against pain, drugs and pharmaceuticals, a fight experienced by thousands of other people, by society as a whole. Both García-Alix, who has gravitated towards video in his latest work, and Goldin – now openly and almost exclusively dedicated to cinema – convey their experiences in a fictional manner (both through poetic narration and documentary-style “neofiction”) to the moving image, taking a formal step that moves from photography to something closer to cinema.

The new approach to documenting things give us hundreds of examples of sino su memoria, contado por alguien que no tiene relación con lo sucedido. El punto central se encuentra fuera de foco. Un paso más allá de ese documentalismo es el que dan los artistas que construyen historias que, o bien interpretan ellos mismos como actores de sus imágenes, o bien buscan quienes cuenten su idea delante de la cámara. Una de las primeras obras de Sophie Calle (Les Aveugles, 1986) nos habla de qué es la belleza, de qué imagen es la representación física y real de la belleza a través de las opiniones de personas ciegas de nacimiento, personas que nunca han visto el mar, ni el cielo, ni una flor, y que definen cómo esos tópicos son, también para ellos, como para casi todo el mundo, la representación de la belleza. Pero antes, en 1982, contratándose como camarera de hotel, fotografía las prendas personales de los huéspedes cuando dejan las habitaciones para ser limpiadas (L’Hôtel, 1982). A través de estas imágenes reconstruye quiénes pueden ser. Antes aún, en la obra Les dormeurs (1979), fotografía a personas a las que paga para que duerman en su propia cama. La idea de yo y otro se funden y se confunden. Como en su vídeo de 1995 No sex last night, un viaje por carretera con un amigo con el que, acostándose juntos cada noche, nunca consigue tener sexo. El destino era Las Vegas, donde this new creativity and freedom when it comes to choosing theme, though what really characterises them is the way in which they treat this theme, how the everyday and the anodyne becomes the focus. The idea is the theme. What happens is still the objective, but it can be relayed in different ways, in new times, portraying not so much an event as its memory, told by someone entirely unconnected to events. The central point is out of focus.

Some artists take a step beyond this form of documenting things by creating stories that they themselves act out in their own images or by inviting others to convey their idea in front of the camera. One of Sophie Calle’s first works, Les Aveugles (1986) talks to us about the nature of beauty, about which image is a real and physical representation of beauty through the opinions of people who were born blind, people who have never seen the sea, the sky or a flower, and who express how such things come to represent beauty, just as they do for nearly everyone. Four years earlier, working as a housekeeper in a hotel, she photographed items of clothing left by guests when she went in to clean their rooms (L’Hôtel, 1982). Through these images, she tries to reconstruct who they might be. In an earlier work, Les dormeurs (1979), she photographs people she has paid to sleep in her bed. The idea of self and the other fuse together and become confused with each other. The same is true of her 1995 video No sex last night, a road trip with a friend with whom she sleeps every night but without ever having sex. The setting is Las Vegas, where they get married and spend their first night as newlyweds in the car, without consummating their marriage. A photographer, writer se casan y pasan la primera noche de casados en el coche, sin tener sexo. Sophie Calle, fotógrafa, escritora y puntualmente actriz y directora de cine, confiesa: “Nunca pensé que llegaría a ser artista cuando empecé. No consideraba que lo que hacía era arte”. Esa actitud en torno a lo que se considera arte, con una idea institucionalizada y canónica, no estaba en ninguna de estas óperas primas de una nueva generación de creadores que sobrevuelan los géneros y los lenguajes, que pasan de una serie, de una época, a otra, sin el peso de la historia del arte sobre sus hombros. Sin embargo, algunos artistas fotógrafos han superado cualquier duda sobre su carácter de artista ya desde sus primeros pasos. Son aquellos que han construido sus obras a partir de planteamientos claramente conceptuales, al margen de narraciones concretas, al margen de la búsqueda de un planteamiento colectivo, social o historicista. Aunque sus obras sean formalmente figurativas, fotográficamente realistas, y esencialmente narrativas, no hablan de ficciones sino de ideas, de planteamientos estéticos, y con unos argumentos esencialmente vinculados con la mirada, con la presencia de la imagen, con el campo de las prácticas visuales. Sin duda Jeff Wall es el más destacado y el que más ha influido en la fotografía más conceptual de las últimas décadas. En la línea de la escuela de fotografía inglesa, de una frialdad conceptual de la que Paul Graham es el principal y más elegante ejemplo, Wall ha puesto en los circuitos teóricos de la fotografía conceptos que ya se venían usando en círculos fotográficos británicos, como el tableau vivant, muy cercano a la staged photography, la fotografía construida o escenificada. Pero él lo ha hecho para justificar no la narración, sino la mirada. En sus primeras series, sobre todo en Movie Audience de 1979, nos pone delante del retrato en primer plano de personas que están viendo una proyección and occasional actress and director, Calle once said: “I did not think about becoming an artist when I began. I did not consider what I was doing as art.” The institutionalised, canonical view of what art should be was absent from the first works of a new generation of creators who flitted from one gender and language to another and from one series and period to another, without the weight of art history on their shoulders. Some photographers overcame any doubts about they may have had about being artists at the very start of their careers, constructing their work upon evidently conceptual approaches and avoiding specific narrations and the search for a collective, social or historicist approach. Although their works are formally figurative, photographically realistic and essentially narrative, they do not talk of fictions but of ideas, aesthetic proposals, and arguments that are essentially connected to the gaze, the presence of the image, the field of visual practices. There can be no question that Jeff Wall is the most prominent of these and the most influential in terms of the most conceptual photography of the last few decades. Influenced by the British school of photography and its conceptual coolness – the leading and most elegant example of which is Paul Graham – Wall has introduced into photography’s theoretical circuits concepts that were used in British circles, such as the tableau vivant, a very close relative of staged photography. He has done so to explain the gaze rather than the narration. In his first series, most notably in Movie Audience (1979), he positions us in front of close-up portraits of people watching a film. We only see them, but what they are watching is present in cinematográfica. Solo los vemos a ellos, pero es en sus ojos, en su mirada, donde está presente lo que ellos ven, y ese es el punctum de la fotografía, ahí es donde se dirige la mirada del espectador, esa es la clave de la imagen. Esa forma de centrar el tema, la idea de la que trata la obra, de una manera oblicua, codificada, se desarrolla en todas sus series desde el inicio de su trabajo. Su alusión a una obra de arte de la historia, a un concepto filosófico concreto, a partir de algo en apariencia totalmente ajeno, pero que, según miramos, vemos cómo se vincula progresivamente, es característico de su trabajo: la alusión intelectual.

Unos fotógrafos construyen su obra mirando a su alrededor. Otros marcan el camino de que mirar hacia adentro es la única vía para poder ver y contar algo definitivo.

Some photographers create their work by looking at the world around them. The path taken by others involves looking inwards, as if it were the only way to see and tell something definitive.

Así, parece que unos fotógrafos construyen su obra mirando en torno a sí, a su alrededor, lo que ellos ven, cómo lo ven, desde dónde miran, y nos dan las claves de algunas de estas primeras obras. Otros marcan el camino de que mirar hacia adentro es la única vía para poder ver y contar algo definitivo. Artistas jóvenes que empiezan a ver su propio camino, un camino que a lo largo de los años se bifurcará, pero que siempre, o casi siempre, vuelve al origen. Cuando se expusieron por primera vez las primeras fotografías de Cindy Sherman, lo que sería su ópera prima —un trabajo escolar de their eyes, their gaze, and that is the punctum of photography, the point where the spectator fixes their eye, the key to the image. That manner of centring the theme, the idea behind the work, which is oblique and encoded, is developed in all Wall’s series, from his earliest works. His allusion to an art work, a specific philosophical concept based on something that appears at first to be entirely unconnected but which gradually becomes so the more we look, is typical of his work. It is an intellectual allusion.

It seems, therefore, that some photographers create their work by looking at the world around them, at what they see, how they see it and where they see it from, giving us clues to some of these first works. The path taken by others involves looking inwards, as if it were the only way su paso por la escuela de Bellas Artes—, Sherman ya era una de las más importantes artistas de la escena de Nueva York, presente en libros y exposiciones, un nombre básico de la fotografía y el arte actual, más aún: una de las artistas que consiguió que fotografía y arte contemporáneo fueran considerados una misma cosa. Esas primeras pequeñas fotografías en blanco y negro nos mostraban a la propia artista transformándose en todas y cada una de las tipologías de los viajeros de la línea de autobús que la llevaba de su casa a la escuela cada día, personas de todas las edades, sexos y razas. Ella era todos, igual que a lo largo de todas sus series ella será todos: los payasos, las mujeres violadas, las viejas ricas, los personajes históricos, ya en color y en grandes formatos. Pero en esas pequeñas y delicadas imágenes de su primer trabajo está la definición de quién es y cuál es la aportación al arte actual de Cindy Sherman. Algo parecido sucede en todas estas óperas primas, algunas incluso son las obras principales de estos artistas, que han hecho de lo cotidiano —y hasta cierto punto vulgar— del mundo doméstico (como Thomas Ruff) imágenes ya simbólicas, obras que alargan sus raíces en las siguientes generaciones de fotógrafos y de otras tipologías de artistas, invadiendo campos en los márgenes como el cómic, el cine, la música o la literatura.

A través de todas estas óperas primas podemos llegar a la conclusión de que tal vez no sea tan importante morir joven y dejar un cadáver bello y hermoso, como un regalo que se da a alguien que no lo quiere. Todos fuimos alguna vez jóvenes y hermosos, y aunque nuestros cuerpos se hayan degradado y nuestras ideas se hayan convertido en teorías brillantes, en grandes obras, y también, por qué no, en grandes y estrepitosos fracasos, por el camino dejamos lo mejor de nosotros: hermosos trabajos que nunca envejecerán, que siempre serán igualmente atractivos, que siempre serán jóvenes, y hermosos, tal y como todos fuimos un día. ¶ to see and tell something definitive. They are young artists who start to glimpse their own way, one that forks off after a few years but which always, or nearly always, returns to the start. By the time Cindy Sherman’s earliest photographs were first exhibited – a college project on her time at art school that would later become her first work –she was already one of the most important artists on the New York scene, a feature of books and exhibitions and a key figure in modern art and photography. What is more, she was in instrumental in contemporary art and photography coming to be regarded as one and the same thing. These first few photographs in black and white show the artist transforming herself into all the passengers she sees on the bus that takes her from home to college every day, people of all ages, sexes and races. She was all of them, just as she would be all of them throughout all her series: clowns, rape victims, rich old ladies and historical figures, by now in colour and large format. But in those small, delicate images of her early work lies the definition of who Sherman is and her contribution to the art of today. Something similar happens in all these first works, some of which are the most important produced by these artists, who have fashioned already iconic images from the everyday – and to some extent vulgar – nature of the domestic world (among them Thomas Ruff), works whose roots extend into subsequent generations of photographers and other types of artists, spilling over into fringe areas such as comics, cinema, music and literature.

In studying all these first works we can come to the conclusion that perhaps it is not so important to die young and leave a beautiful corpse behind us, like an unwanted gift. We have all been young and beautiful once, and though our bodies have deteriorated and our ideas have become brilliant theories, great works or, why not, great and calamitous failures, we have given the best of ourselves along the way: gorgeous works that never grow old and will always be young, beautiful and attractive, like we all were one day. ¶