16 minute read

IN TOUCH WITH THE ISS

Engaging the public

BY EDWARD GOLDSTEIN

Early in the Kennedy administration, there was a raging debate in Washington about the advisability of conducting Alan Shepard’s Freedom 7 Mercury launch in public (May 5, 1961) 1 . After all, the argument went, the United States would lose tremendous prestige if our Redstone rocket blew up on live television before the eyes of the world. NASA’s internal documents suggested the flight had only a 75 percent chance to succeed. Kennedy chose the path of openness, stating in his address to Congress proposing a moon landing (May 25, 1961), “We take an additional risk by making it in full view of the world, but as shown by the feat of astronaut Shepard, this very risk enhances our stature when we are successful.”

Indeed, from NASA’s early years on, public engagement in the excitement of our space missions has been an integral part of the American space endeavor and how we wanted to project our space triumphs to the world. But whereas in NASA’s infancy the public was mostly limited to cheering on our space achievements as armchair spectators, the International Space Station has expanded the realm of public engagement on many fronts both in the United States and globally, truly making it the people’s space station.

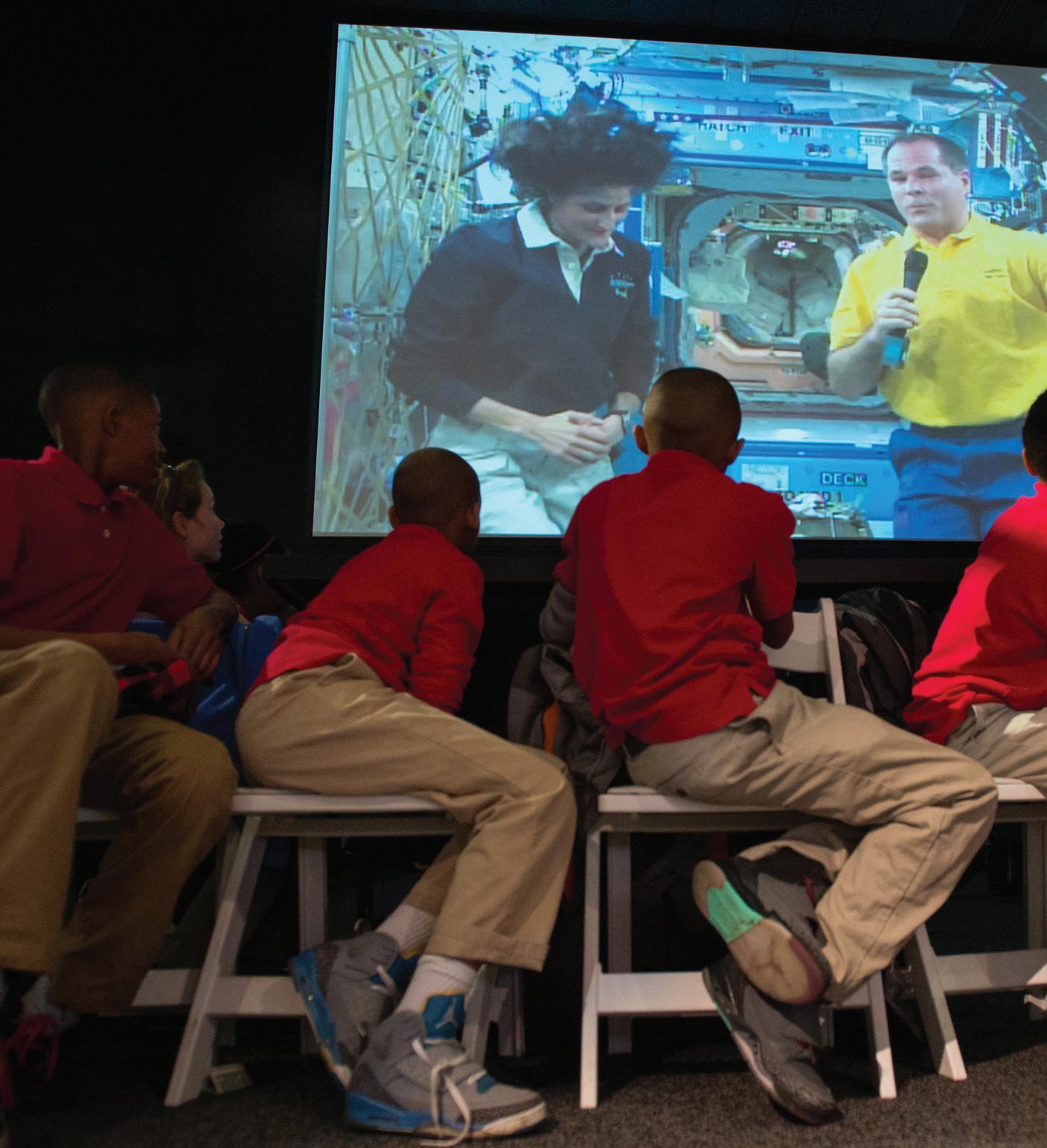

International Space Station Expedition 33 flight engineer Kevin Ford (on screen) answers questions from students during a downlink event held in honor of International Education Week at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

At a most basic level, the public can experience the space station not just via television, but in the flesh. Unlike past NASA space vehicles, the massive orbiting laboratory is easily visible to the naked eye. During pre-dawn and dusk passes overhead, it is the third brightest object in the sky, making stately arcs from horizon to horizon. Go to: https://spotthestation.nasa.gov/ to plug in your location and find the precise time and place the space station will be presenting an awe-inspiring light show in the skies above you.

President John F. Kennedy delivers a speech announcing his goals for the nation’s space effort to land a human being on the Moon before a crowd of 35,000 people in the football stadium at Rice University in Houston, Texas, on Sept. 12, 1962. Kennedy recognized the importance and value of being open with the public in regard to NASA’s space missions and activities.

A close-up of astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr. in his space suit inside the Mercury capsule. The launch of the historic Mercury-Redstone 3 mission, during which Shepard became the first American in space, was televised and watched by millions in the United States.

But even beyond spectating opportunities, including, of course, the millions who have personally viewed a launch to the space station from the Kennedy Space Center, the orbiting laboratory has provided unprecedented opportunities for direct public engagement with our astronauts onboard the facility, and for student investigators to design and participate in space station experiments.

ISS STEMONSTRATIONS AND ASTRO SOCKS

Consider the work of Becky Kamas, NASA’s STEM on Station activity manager. Kamas’ days are filled with programs engaging primarily with K-12 students, their teachers and parents, and community members in space station missions. Through regularly scheduled educational downlinks or “STEMonstrations” from the orbital outpost, her office has reached millions of students. “When a school district or science center hosts a downlink, they have an opportunity to make it a community-wide event,” she said. “So, it is not just the students who get to sit in the auditorium for 20 minutes while they are chatting with the astronauts. It really becomes a community event where the entire district or community gets behind it and participates in STEM activities leading up to or even after sending up questions to the astronauts. It goes far beyond those 20 minutes for those students in the auditorium. It has a very broad reach.”

advertisement

Kamas explains that schools interested in participating in a downlink must develop an education plan to maximize STEM content, a technology plan to make the event happen seamlessly, and a community outreach plan to “engage VIPs, legislators, STEM professionals, and other educational organizations in the community.”

NASA astronaut Kjell Lindgren uses a HAM radio to speak with operators down on Earth during Expedition 45. The International Space Station is equipped with amateur radio equipment allowing astronauts to share the excitement of space exploration and to inspire and ignite interest among students and others on the ground.

Even more intrepid students can have oneon-one audio conversations with space station astronauts by participating in the Amateur Radio on the International Space Station (ARISS) program. This opportunity is made possible by a consortium of national amateur radio organizations in the participating space station countries.

Expedition 56 flight engineer Ricky Arnold works with a student-designed experiment using Nanoracks commercial science hardware in July 2019. The study is researching the impacts og microgravity on tissue regeneration, concrete properties, and the growth of plants, fungi, and bacteria. The research introduces student s to the principles of space science, possibly leading to careers as scientists.

Kamas’ office also helps spur student STEM education through involvement in space station research. “That means everything from curriculum support materials that teachers can use in the classroom to challenges for students where they tackle real-world problems and help propose and design solutions to flying payloads.” Kamas adds that working with Nanoracks through their research hardware and facilities in the ISS U.S. National Lab, they are also helping college students design experiments for the near zero-gravity environment. She said, “We are requiring those higher education students to engage K-12 students in citizen science related to their experiment. There is no better way to get students involved than to have them do hands-on work side-by-side with those researchers. An example would be having the K-12 students doing ground research that would provide the space researcher with parallel data, or even having the students run analysis on the data, providing useful content back to the researchers.”

Pictured below are three examples of items designed and manufactured by students through NASA’s HUNCH project.

Astronaut Reid Wiseman uses a soft, collapsible HUNCH crew quarter organizer that features removable mesh pockets.

A double locker produced by students houses the Phase Change Experiment aboard the space station.

Astronauts in orbit on the space station model footpads created by students.

A favorite example for Kamas of student engagement involves the creation of “astro socks.” She tells it this way: “It stemmed from a conversation when we were meeting with Microsoft Education and we were telling about how when you go to the ISS, the calluses migrate from the bottom of your feet to the top of your feet because astronauts use their feet to hook up under those hold bars. We showed a video of Peggy Whitson taking off her socks and you see the skin flaking off. They thought this was just fascinating and that middle-school students would just love this; you get to see cool gross body science stuff. And from that, we developed an engineering design challenge where students actually built a prototype device that astronauts can put on their feet to alleviate some of the pressure.” Kamas noted that during a downlink to the Museum of Flight in Redmond, Washington, attended by 250 students, the participants asked astronaut Jessica Meir about the pressure her feet feel in space. Astronaut Dottie Metcalf-Lindenburger was in Redmond in the audience. The students got to share their designs with her as well. “It was really a great culminating event from the very beginning of doing the design to being able to talk to an astronaut on the space station about this realworld problem that impacts her.”

STUDENT-CREATED HARDWARE AND MEALS

Through NASA’s HUNCH project, students also get the opportunity to design flight hardware for the space station. HUNCH, shorthand for “High School Students United with NASA to Create Hardware,” was started by NASA Payload Training Capability Project Manager Stacy Hale in 2003. Hale had learned from observing his high school-aged son that project-based learning opportunities could not only spur students’ academic development but could also provide useful training equipment for the space station.

Today, through HUNCH, students design prototypes and bend metal on items that help space station crews be more productive. HUNCH students have produced 1,340 items flown to the orbiting laboratory, including stowage lockers, crew quarter organizers, footpads, EVA wire ties, a galley table, and sleeping bag liners.

HUNCH students have also proved themselves adept at skills that might get them a gig on the Food Channel. “Five years ago, we asked a couple crewmembers what they would think if we started a culinary challenge,” noted Hale. “And they were excited about it. They were excited about the variety that might come in. We talked to the Food Lab and they were all in favor of it. The culinary students design an entrée or side dish, learn how to preserve it, and the food science behind it. Once, we sent some food up to the ISS; the crew used their laptops to call the school directly and talk to the teachers and students and thank them.”

HUNCH has significantly impacted students’ lives in Hale’s estimation. “I can go into a classroom at the beginning of the year and no one is looking me in the eye, but towards the middle of the year you can see that they feel good about themselves,” he said. “They realize that they can make something that is going to be used by astronauts, either in space or to train to prepare for what they do in space. It gives them some confidence, making them excited about what they are going to do in the future. I can point to four or five people who now have jobs at NASA who came up through this. I can also point to others who are working with the technology that they learned doing HUNCH.”

Damascus as seen from the International Space Station in an image acquired via EarthKAM.

HONORING SALLY RIDE’S LEGACY

The late Dr. Sally Ride, America’s first woman in space, is a presence on the space station through the EarthKAM (Earth Knowledge Acquired by Middle school students) project, which has engaged a million students in taking Earth images from a space station-based Nikon D2Xs digital camera, controlled by a Lenovo (IBM) T61p laptop. Kay Taylor, director of education at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center’s Space Camp in Huntsville, Alabama, tells the story:

“EarthKAM was started by Dr. Ride [in 1995 as a space shuttle camera called KidSat]. She was not only motivated by seeking a way to engage students in space science, but also I think she realized when you are in space, you have a very rare perspective on our planet,” said Taylor. “So, she came up with this concept of allowing students to control a camera from space.” The U.S. Space and Rocket Center partners with the University of Alabama-Huntsville and Teledyne Brown Engineering on the project, the second longest-used payload in space station history. Participating Sally Ride Earth- KAM middle school classes request a certain location to be photographed, based on the latitude and longitude coordinates beneath the space station’s orbital path, and the captured image is stored for further investigation. “We’ve had some images of the pyramids at Giza, we’ve had some great shots of the Amazon,” said Taylor. “But if there is a rock star in Sally Ride EarthKAM, it has got to be Australia. That continent is gorgeous. You get great coastline images with gorgeous emerald waters. You are looking at the greenery or the gold and yellows of the deserts. For educators who use these images in a variety of ways, the complexity of the images, the variety of the terrain, provide a great way to teach ecology or art.” Taylor noted the Sally Ride EarthKAM, like other NASA space station science engagement activities, is a free resource. “We have teachers that have been using the program for years. It is a great way to empower a 12-, 13-, 14-year-old student to control a live scientific instrument 250 miles above our heads on our space station. That’s powerful.”

Above: A view of the Sally Ride EarthKAM hardware set up for use in the Window Observation Research Facility (WORF) aboard the International Space Station. Below: A Canadian student form Good Shepherd School in Peace River, Alberta studies orbital paths of the International Space Station. Students participating in EarthKAM missions review space station orbit racks to identify available images.

THE GREATEST SOCIAL MEDIA PLATFORM

Communications from NASA missions were once limited to garbled orbital to ground radio communications. Live television from space only came into play beginning with the Apollo 7 mission in October 1968. Now, the space station provides NASA (and partner agencies) an excellent platform to produce one of the most dynamic social media presences on and beyond Earth. “The Space Act [NASA’s 1958 founding legislation] requires that we share information by the broadest means available,” observed Leah Cheshier, social media manager at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. “Right now it’s social media. We’ve had our accounts for several years now [Facebook: International Space Station (4 million followers); Twitter: @Space_ Station (3 million followers); Instagram: www. nasa.gov/instagram; Snapchat: www.snapchat. com/add/NASA]. And we share the science that goes on aboard the ISS, the upgrades to the space station, details about spacewalks, and mission coverage of spacecraft arriving and departing. We share beautiful imagery and show people around the world a perspective they would never ordinarily get to see. So, it’s really a great platform to build awareness about how we are working on the ISS to benefit everyone on Earth.”

To Cheshier, “public engagement is so much easier when we have social media. I think it’s the most direct way to talk to the public.” She added, “When media was just television, radio, and newspapers, you didn’t really get that other side, the two-way communications that give people the opportunity to say what they love, or even share what they love with other people.”

Above and below: NASA is active on social media, engaging millions of followers on Twitter, Facebook, and other platforms with details about space station activities and beautiful Earth imagery captured on orbit.

While the space station does not have its own YouTube account, it did provide the setting for Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield’s 2013 YouTube rendition of David Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” which became an overnight sensation with more than 47 million views and counting (www.youtube.com/ watch?v=KaOC9danxNo). In a video describing his musical tribute, Hadfield said, “NASA is tens of thousands of people. I think that overall, they saw that it allowed people to see spaceflight for what it really is. It’s people exploring the rest of the universe, living in an environment we have never been in before. We are up there just experiencing things like anybody else is. We are taking the culture we were raised with to a new place and adapting it. And that, I think, is a healthy and natural thing to do. And so, NASA, to a large degree, really loved it. And there are all sorts of stuff NASA is doing now using social media, using YouTube, using technology onboard to try to help people understand spaceflight even better.”

Hadfield also noted that, during his first space shuttle flight (STS-74, 1995), “there were no digital cameras, so every picture was film. There was no internet. And in fact, real-time communications with the vehicle was just radio. It is really difficult to share a magnificent experience just by radio … Imagine if Michelangelo were lying on his back painting the Sistine Chapel and he had a web cam next to him, and you could ask him questions. We had no idea what Michelangelo was thinking. We only see the result. I think seeing and understanding the process and the human side of it is a really important part of the creation of new things and the exploration of new places.”

CELEBRATING OUR DIVERSITY

A key factor in the space station truly being the people’s space station is that its crews represent something special that is relatable to all people: They look more like us. The early years of space exploration were almost exclusively a white male endeavor. While there is still work to be done in diversifying the astronaut corps, today’s astronauts have begun to better reflect our nation’s melting pot of races and cultures. It is celebrated, but in a sense not remarkable, that women astronauts command space station missions or conduct spacewalks. And crewmembers are now scientists, engineers, doctors, teachers, and not just test pilots. And yes, even a few non-astronauts have flown to the orbital outpost as space tourists.

NASA astronaut Cady Coleman, Expedition 27 flight engineer, plays a flute in the JAXA Kibo laboratory onboard the International Space Station during some free time. While in orbit on the space station, Coleman played a duet with Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull.

THE INTERNATIONAL DIMENSION

The space station is also a truly international endeavor, with crew participants coming from the United States, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Italy, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and the United Arab Emirates.

In 2003, Chinese taikonaut Yang Liwei became his nation’s first man in space, flying aboard a Shenzou 5 spacecraft and orbiting the Earth 14 times. During his flight, he received a radio greeting in Chinese and English, sent via Mission Control from astronaut Ed Lu, who was then part of Expedition 7 aboard the space station. Lu, whose parents were born in China, remarked to his fellow space station crewmate Yuri Malenchenko, “Yuri, guess what? Right now, 66.7 percent of the people in space are now Chinese.” China is the third nation to independently launch humans to space, but was banned from participating in the International Space Station by a 2011 law.

Yang Liwei, China's first taikonaut, flew into space in 2003 aboard a Shenzou 5 spacecraft.

Because of its international dimensions, the space station is a reflection, as Hadfield observed, of our globe’s rich cultural diversity. John Uri, manager of the Johnson Space Center’s History Office, put it this way: “You look at [the] space station and you see an engineering feat. But there are people living up there, and so there is a societal impact as well with people living up there for six months; they kind of have to continue living their lives to some degree. So, I like looking at various things such as how they celebrate their birthdays. The other thing I like to look at is music. Many of these astronauts and cosmonauts are musically talented. Cady Coleman plays the flute and did a duet [of the song “Bourrée” in 2011] with Ian Anderson [founder of Jethro Tull] and created a video of that which was just fascinating.”

Uri also said, “Food is such an integral part of every culture. And with this being a multinational project, astronauts from different countries bring their own foodstuffs. There have been sushi parties onboard. The French bring their specialties. Then there is exercise and sports. [Sunita L.} Williams ran a marathon [on a space station treadmill in 2007, coinciding with the Boston Marathon, with an official completion time of 4:23.10]. They end up watching events like the Super Bowl and the World Cup. They even had a tennis match onboard [participants in the 2018 match were U.S. astronauts Drew Feustel, Serena Auñón-Chancellor, Ricky Arnold, and European Space Agency astronaut Alexander Gerst].”

NO BORDERS

While it is a cliché that from space, astronauts marvel that they see no national borders, the perspective this vantage point affords continues to resonate with space travelers and people on Earth who see cooperation in the heavens as a role model for how we can get beyond our destructive conflicts. As astronaut Scott Kelly put it in his book Endurance, his account of his year onboard the space station, “When people ask whether the space station is worth the expense, this is something I always point out. What is it worth to see two former bitter enemies transform weapons into transport for exploration and the pursuit of scientific knowledge? What is it worth to see former enemy nations turn their warriors into crewmates and lifelong friends? This is impossible to put a dollar figure on, but, to me, it’s one of the things that makes this project worth the expense, even worth risking our lives.” So, while 20 years of cooperation between men and women of different nationalities on the space station has not dramatically altered the mindset of nations regarding the conduct of events here on terra firma, the people’s space station at least provides an example of how things can be.

1. https:/history.nasa.gov/SP-4201/chll-3.htm