16 minute read

ACROSS THE PACIFIC: STRATEGY, TACTICS, AND THE NUTS AND BOLTS OF “ISLAND-HOPPING”

BY CRAIG COLLINS

American planning for a war against Japan began as early as 1897, amid rising tensions over the state of the Hawaiian islands, where thousands of Japanese worked in the sugar industry. In 1898, stirred by a wave of nationalism arising from the Spanish-American War, the United States annexed Hawaii over vigorous Japanese protests, and its victory over Spain gave it possession of new territories: the Philippine islands and Guam, one of the Mariana Islands, about 1,600 miles south of Tokyo. From the start, American leaders understood and were troubled by the vulnerability of these new possessions, which were separated from the continental United States by more than 8,000 miles of ocean. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt called the Philippines “our heel of Achilles.”

“Flat-nose Flossie,” a Landing Ship, Tank (LST), unloads a Landing Vehicle, Tracked (LVT) on the beach at Iwo Jima, Feb. 19, 1945. Specialized ships and vehicles like the LST and LVT were a vital part of United States tactics in the Pacific war.

U.S. Navy Photo

As an Entente Power of World War I, Japan was crucial in securing Pacific and Indian Ocean sea lanes against the Imperial German Navy, and during the war seized Germany’s island colonies in the Mariana, Caroline, and Marshall islands. Japan emerged from the war a modern industrial state and a great geopolitical power, and its occupation of the Northern Marianas established a ring of Imperial outposts around Guam.

American war plans of that period adopted the code name of the probable enemy, and the early plan for a hypothetical war with Japan, designated the Orange plan, called for the Army to defend the Philippines until the Navy could send reinforcements across the Pacific, where a decisive naval battle, reminiscent of World War I’s Battle of Jutland, would determine the outcome of the war.

The role of the Marine Corps, which had landed at Guantanamo Bay to establish a coaling station for U.S. Navy ships during the Spanish-American War, was not well defined in the early Orange plan; traditionally, Marine units had been deployed to occupy and defend forward naval bases. Two Marine intelligence officers, Maj. Dion Williams and Capt. Earl Hancock “Pete” Ellis, began to study the plan and envision a role for Marines in a Pacific conflict.

The Pacific Fleet’s battle line burns at Pearl Harbor. War Plan Orange’s original incarnation, where the fleet would sail for a decisive battle with the Japanese after which the Philippines would be relieved, was rendered moot by the attack. It was replaced by War Plan Rainbow 5, based in large part on a pre-war strategy developed by Marine Corps visionaries.

National Archives Photo

Ellis was among the first to recognize that Japan’s new outposts made it likely, if war broke out in the Pacific, that both the Philippines and Guam would fall almost immediately, before reinforcements could arrive. Marine Corps units and Army troops would face the task of attacking and seizing Japanese bases in the Pacific – in the Marshalls, Carolines, Marianas, and Philippines.

Ellis wrote a plan to systematically reduce Japan’s presence in the Marshall Islands, titled “Operations Plan 712: Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia.” His theories, which were limited by the equipment and ordnance then available to the U.S. military, called for the amphibious assault of these islands, with fire support from naval warships. His plan constituted the first attempt at an amphibious assault doctrine and strategy. While the amphibious Allied campaigns of the Pacific would look much different from those he envisioned, Ellis’ plan revolutionized the role of fleet Marines: Instead of defending advance bases, they would attack and seize them from the enemy, with the support of military technology including submarines and aircraft – both of which were relatively new to the world. By the mid-1930s, the Marine Corps had developed an amphibious operations doctrine and had established the Fleet Marine Force, designed explicitly for amphibious assault.

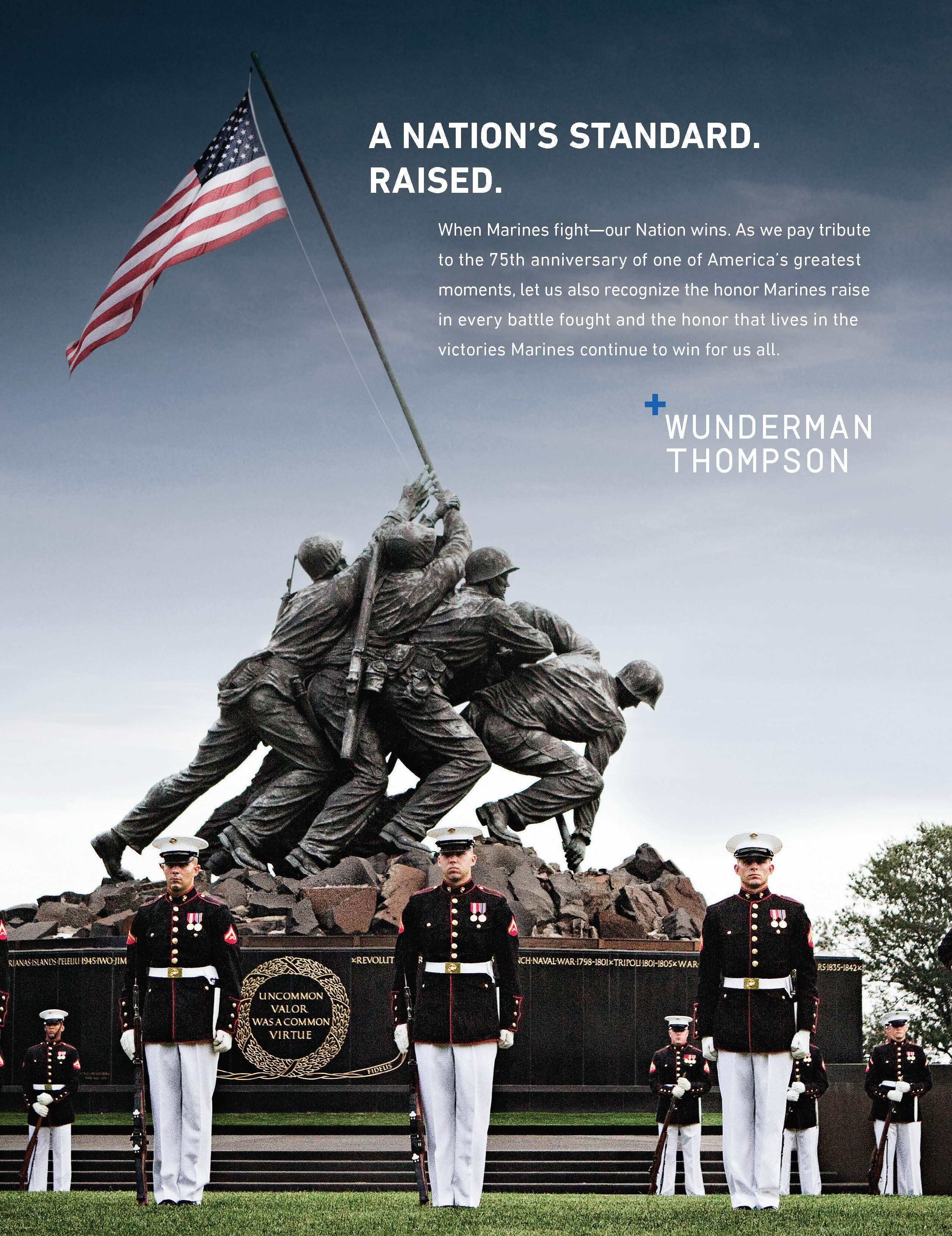

advertisement

The U.S. war plan that emerged in 1941, after Pearl Harbor, was the Rainbow 5 plan, which called for the United States to defeat Germany before focusing its attention on Japan. The strategy for Japan’s defeat was a two-pronged offensive that integrated some elements of Ellis’s plan. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Allied Commander in the Southwest Pacific Area, would isolate the Japanese stronghold on Rabaul Island, in what is now Papua New Guinea, by advancing along the northern coast of New Guinea, while Adm. William “Bull” Halsey would seize the island of Guadalcanal and drive along the Solomon chain toward New Guinea. Meanwhile Adm. Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet, would lead the Central Pacific Campaign, beginning at the equator and routing Japanese troops from the Gilbert, Marshall, and Mariana islands, gradually advancing toward the Japanese mainland.

LOGISTICS: BUILDING THE FLEET TRAIN

Projecting and sustaining American military might across the vast distances of the Pacific presented a significant challenge. American naval planners estimated, after World War I, that a fleet of warships lost about 10 percent of its combat power for every 1,000 miles it operated away from its base. Driving Japanese defenders from island strongholds and advancing toward mainland Japan would require U.S. forces to travel 5,000 to 7,000 miles from the closest naval station at Pearl Harbor; engage and defeat the Japanese naval defenders at sea; overwhelm land-based defenders with amphibious assault forces; design and build bases, airstrips, and seaports on captured islands; and defend these bases from enemy recapture.

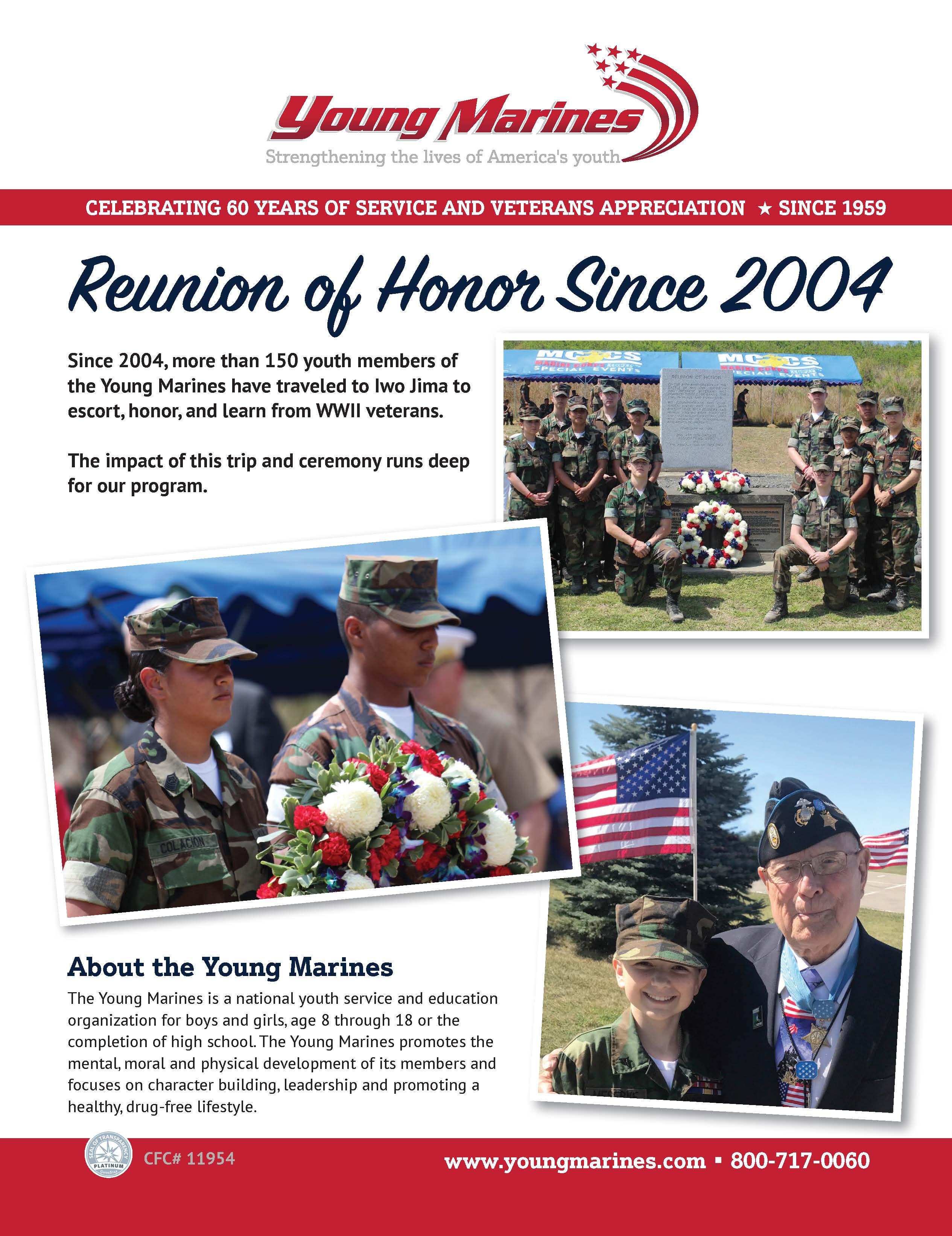

Vought Kingfisher floatplanes of Detachment 14, Scouting Squadron Two (VS-2) dispersed in the trees on Bora Bora during July-August 1942. While the concept of seizing advance island bases and using them as airfields and logistics bases was sound, Operation Bobcat, in accomplishing this on Bora Bora, proved there were many kinks to work out in turning theory into practice.

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photo

While force projection doctrine and the American war machine ramped up to produce the ideas and hardware the military would need to pull this off, it quickly became clear that the challenge the U.S. military confronted in the Pacific was largely one of logistics – the science of moving, supplying and maintaining military forces. Just days after Pearl Harbor, American forces on Wake Island surrendered to Japanese invaders after an American relief expedition, hindered by refueling problems and a lack of modern oilers, was called off. Operation Bobcat, the first deployment of U.S. forces to the Pacific after Pearl Harbor, was a joint Army-Navy task force sent from the East Coast, through the Panama Canal, to construct a naval fueling base on Bora Bora, in the South Pacific territory of French Polynesia. The up-front challenges of this operation – securing shipping assets and converting them to military use; assembling men and materiel; identifying cargo; finding adequate loading facilities – were prelude to the troubles and delays the task force encountered after arriving in mid-February 1942. The most infamous of these became evident when personnel discovered that the heavy tractors and trucks needed to unload the five transport ships had been the first items loaded stateside – meaning they were stowed deep in the ships’ holds beneath the 20,000 tons of supplies they were meant to unload. For the 52 days it took to correct this and other mistakes, the transports and their escorts were sitting ducks, idling off the coast of Bora Bora – which, fortunately, was never attacked by the Japanese and served as a vital fuel facility for Allied ships crossing the Pacific.

The comically bad logistics of Operation Bobcat provided the wake-up call the military needed to develop and refine the Allies’ devastating amphibious campaigns. The scope and timing of many Allied operations in the Pacific were influenced by the availability of supplies and equipment, particularly of shipping and landing craft, but despite these setbacks, the Allied victory is today largely attributed to the superior logistics of American planners.

One of the grand logistic achievements of World War II was the establishment of the fleet train, the lifeline of the Pacific Fleet, which at its peak consisted of 358 ships: freighters, oilers, escort carriers, destroyers, destroyer escorts and tugs. This was accelerated by the creation of an At Sea Logistics Service Group (ASLSG), a floating supply base complete with tenders, repair ships, and concrete barges. The ASLSG provided a nerve center for Navy logistics and underway replenishment (UNREP). The capacity ultimately achieved by the Fleet Train is staggering: The invasion of Okinawa, for example, was aided by the underway delivery of more than 10 million barrels of fuel oil; more than 320,000 barrels of diesel; more than 25 million gallons of aviation fuel; nearly a thousand replacement aircraft, and more than 15,000 bags of mail.

Nimitz established a basic charter for joint logistics in the Pacific, outlining a supply policy for advance bases. Operationally, this policy reached a pinnacle of complexity and efficiency under the Tenth Army’s Island Command, led by Maj. Gen. Fred C. Wallace. The command, which consisted of more than 150,000 personnel at its peak, was a huge multi-service organization including combat, engineer, anti-aircraft, military government, communications, and supply units. By the end of the Okinawa invasion, Island Command had built 18 airstrips, 164 miles of road, supplied 183,000 troops from all services, and administered military government to nearly 200,000 people on the island.

On islands where there was a large joint base – such as Guam, which provided an Army air base as well as the western Pacific’s principal naval base – Army engineer troops were largely responsible for building Army facilities, and Navy construction battalions – Seabees – for Navy facilities, but the unified construction command was so large, and shared so many personnel and resources, that the two branches often built installations together.

Seabees use Marston matting to make repairs and complete construction of the airstrip at Henderson Field in Guadalcanal in 1942. The Seabees and Army engineer battalions, and technologies like Marston matting, were key to constructing U.S. bases, supporting the advance across the Pacific.

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photo

By contrast, the appallingly bad logistics of the Japanese military – constrained by the empire’s unswerving vision of a short war that would be concluded with a “decisive battle” and subsequent treaty negotiations – proved the fatal weakness in its strategy to defend the homeland from an extended perimeter of island bases. Sixty percent or more of the 1.74 million Japanese troops who died in the war succumbed to starvation, rather than battle wounds.

The United States and its allies exploited this weakness, and turned the vast distances of the Pacific into an advantage through operations that came to be framed strategically as “island-hopping” or “leap-frogging”: bypassing strongly fortified Japanese garrisons and taking weakly defended islands – by surprise, when possible – and quickly establishing airfields. With Allies dug in around them, these strongholds would be cut off and left to “wither on the vine.”

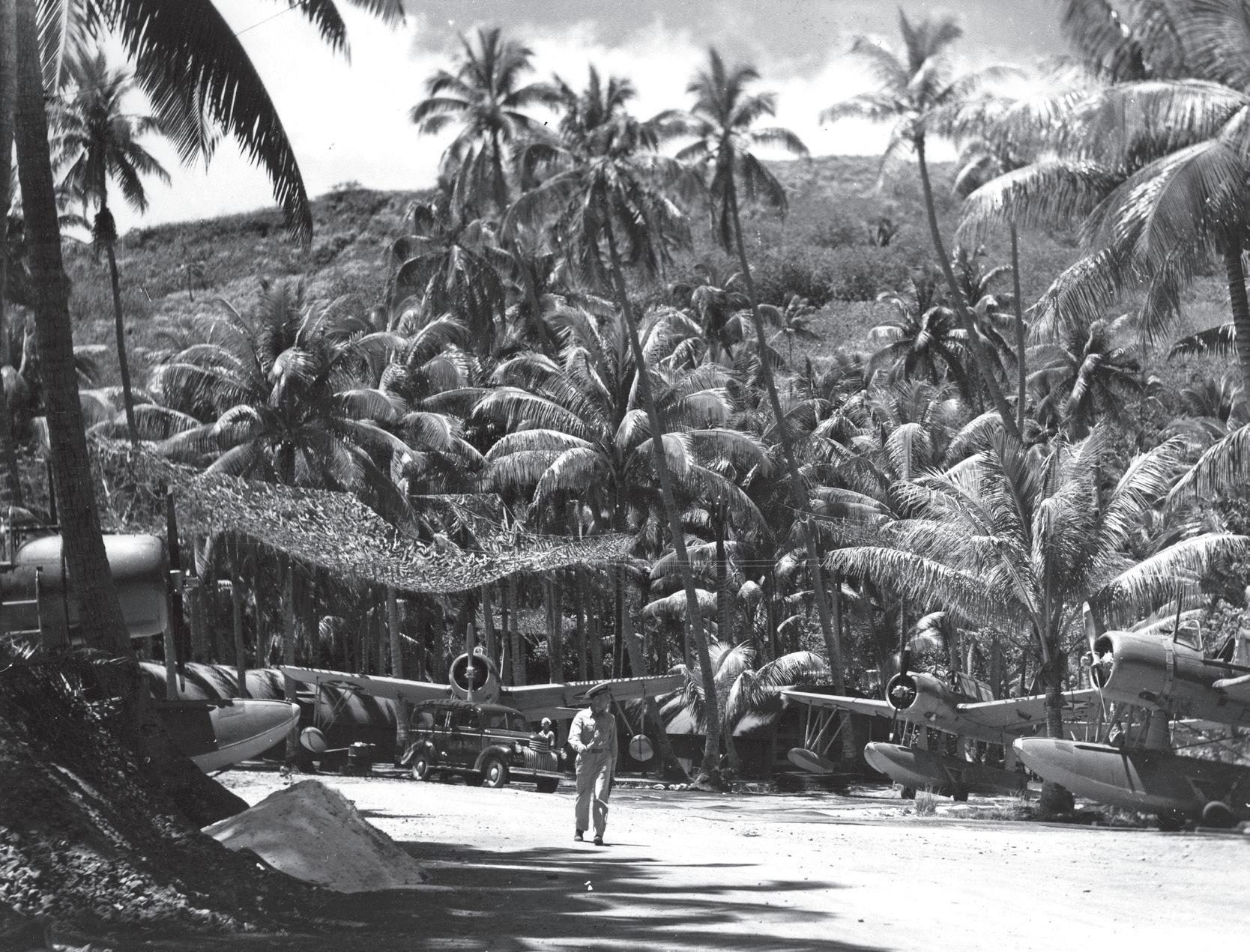

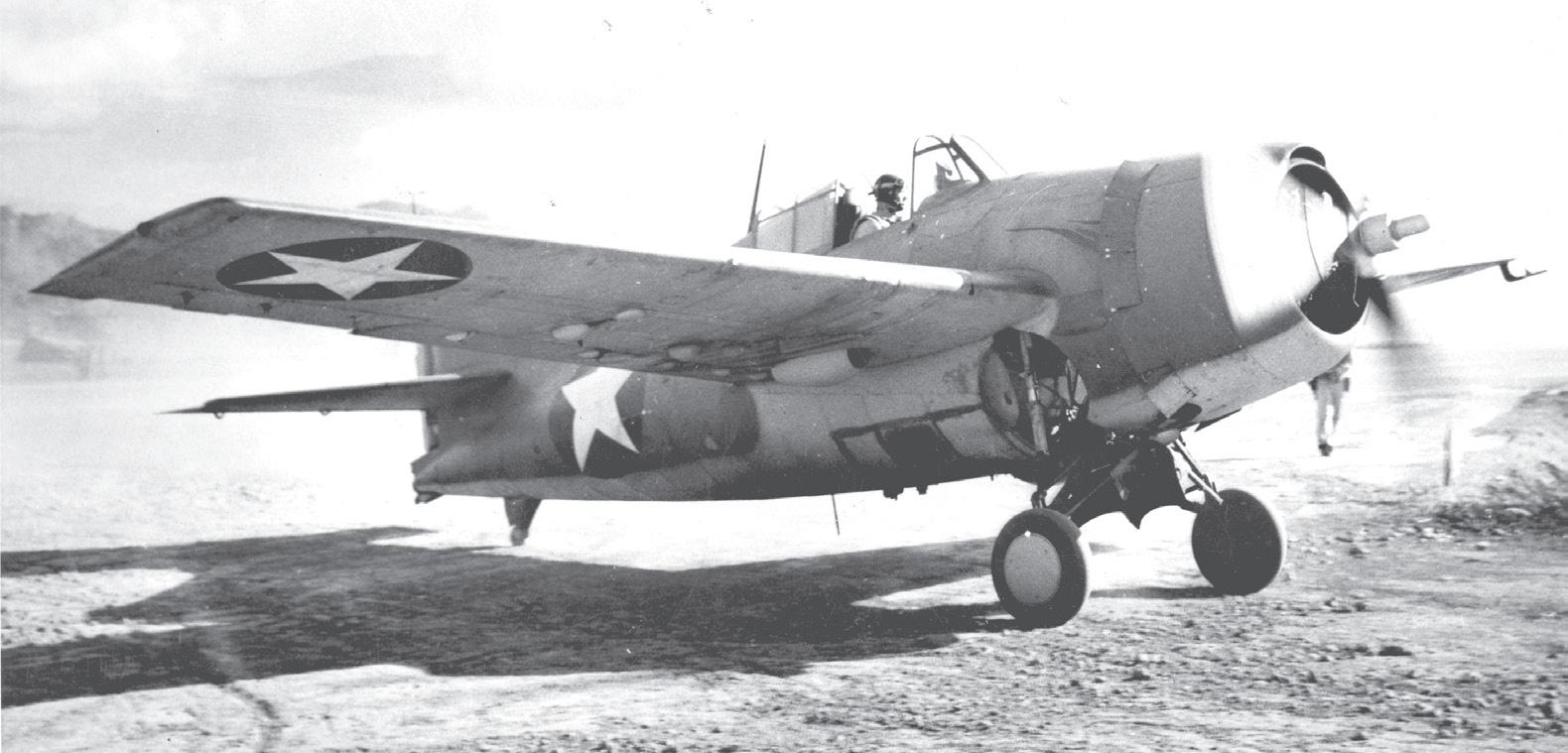

A Marine Corps F4F Wildcat returns to Henderson Field after a sortie. Once seized, islands became unsinkable aircraft carriers from which Navy, Marine Corps, and Army Air Forces squadrons carried the fight to the enemy.

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photo

Allied amphibious assaults often followed this strategy: In the North Pacific, after Japan had seized the Aleutian Islands of Kiska and Attu, U.S. and Canadian forces avoided the Kiska garrison and took nearby Attu, cutting Kiska off from the west and forcing the Japanese to evacuate. In the Solomons, the assault on Vella Lavella bypassed the Japanese garrison at Kolombangara; this was followed by landings on Cape Torokina, avoiding the Japanese garrison on Bougainville. Nimitz, overriding the preference of his entire staff, ordered that Kwajalein, in the center of the Marshall Islands group, be seized before attempting assaults on any of the group’s strongly defended atolls. Allied troops under MacArthur, too, adapted this strategy in their overland campaigns through the jungles of New Guinea, bypassing Japanese garrisons on their way toward the Philippines.

The choice to bypass Japanese strongholds often seemed dictated by circumstances, rather than grand strategy, and there were notable exceptions: The capture of Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands, for example, cost the lives of more than 1,000 Marines, with an additional 2,100 wounded, for an airstrip that proved too short to accommodate U.S. bombers. At the time, Marine forces had captured several nearby islands with minimal casualties, and Seabee battalions had built airfields on them. One hundred miles to the north, for example, a company of 78 Marine reconnaissance scouts, with fire support from the submarine USS Nautilus, seized the island of Abemama, where Seabees built an airfield that B-24 bomber squadrons used to attack Japanese targets in the Marshall Islands. Tarawa was abandoned within months, as operations pushed northward into the Marshalls, where the Allies established a fleet base at Eniwetok. Unfortunately, Tarawa would neither be the bloodiest battle of the Pacific nor the last time the Marines were thrown straight into the teeth of the enemy’s defenses.

NEW TECHNOLOGIES ON AIR, SEA, AND LAND

The island-hopping strategy required air supremacy, to keep newly established Allied garrisons from becoming isolated themselves. At the outset of the war, American strategists – many of them World War I veterans – envisioned the aircraft carrier as an important supporting element for the battleships that would fight, in the style of Jutland, the war’s decisive naval battles. But carriers quickly superseded the battleship as the Navy’s capital ships. Fleet formations were built around them in units such as the carrier task group, in which battleships were relegated to supporting roles.

In August 1942, the Allies began their Pacific counteroffensive with an amphibious landing at Guadalcanal Island, in the southern Solomons, where a Japanese airfield threatened mainland Australia. In this first combined-arms assault on an island base, the U.S. military demonstrated the basics of how it would win the Pacific. Elite Marine troops landed ashore and drove inland while carrier-based ground-attack aircraft and naval gunfire pounded the enemy. The airfield – named Henderson Field in honor of a Marine bombing squadron commander who died at Midway – was captured quickly, renovated by Seabees, and quickly put into American service, but the battle to hold onto it was a grinding six-month campaign that involved several major land, sea, and aerial battles, ultimately killing or driving out tens of thousands of overextended and undersupplied Japanese troops.

Despite enemy fire, Marines wade toward shore at Tarawa Island. Landing boats and barges brought them to within 500 yards of the beach, but the coral bottom prevented the boats coming any closer to the shore. LVTs were able to cross the reef and deliver Marines and supplies to the shore, but there were too few and most were knocked out. Casualties were heavy.

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photo

Maintaining air supremacy required the Allies to work fast in rebuilding or constructing airfields, and Seabees were aided by innovations such as Marston matting: lightweight, perforated, interlocking steel planks that provided good traction and drainage and were used to pave airstrips and roads. At Guadalcanal, Seabees built additional airstrips at Koli Point, 6 miles from Henderson Field. The matting enabled U.S. forces to build airfields with astonishing speed, allowing land-based bombers and fighters to isolate bypassed Japanese garrisons by air. After the fleet formations advanced to established new Allied bases, these air forces were supplemented by light naval forces in the often poorly charted waters around these islands, including small motor torpedo boats – which had already proven their value by driving off a Japanese resupply convoy to Guadalcanal in December 1942.

It was the urgent need to protect Australia that had spurred the Guadalcanal invasion; the Allies weren’t really ready for such an undertaking. The Japanese array of naval warfare technology, including its worldclass torpedoes and the Zero fighter aircraft, outclassed its American counterparts. It wasn’t until 1943 that the Navy introduced the F6F Hellcat, which significantly outmatched the Zero.

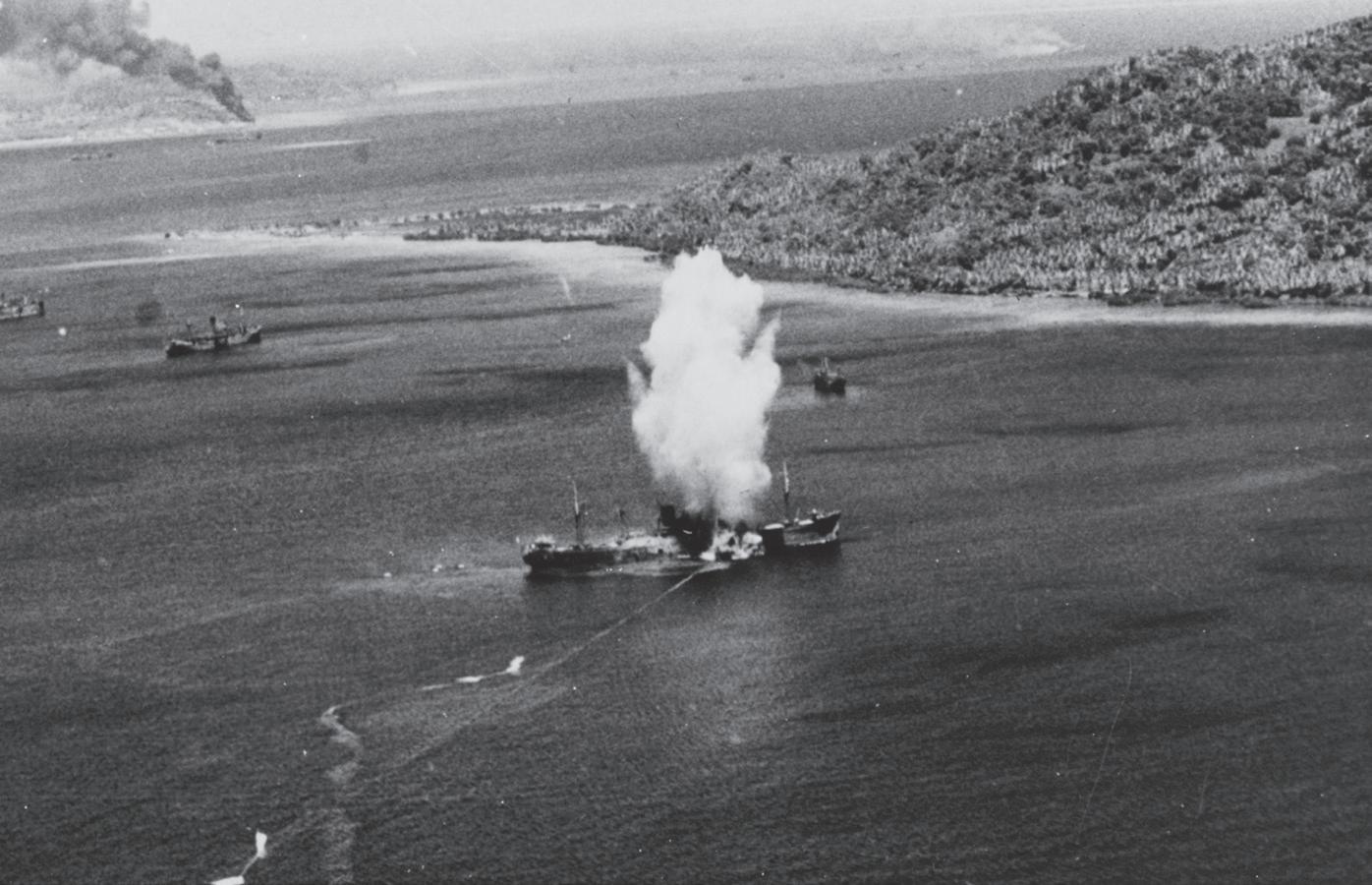

Much preferred, if possible, over fighting bloody battles for fortified Japanese islands was to bypass them entirely, isolate them by air and sea blockade, and let them “wither on the vine” as in the case of the Japanese bastions on Rabaul and Truk. Here a torpedo hits a Japanese cargo ship during the first day of U.S. Navy carrier air raids on Truk, Feb. 17, 1944.

U.S. Marine Corps Photo

Once in control of the Solomons, Allied forces demonstrated the devastating effect of land- and carrier-based aircraft. In the fall of 1943, American, Australian, and New Zealand aviators flew sustained bombing raids from Solomons airfields against the heavily fortified Japanese airfields and port of Rabaul. Their work was soon supplemented by bombers and fighters dispatched from the carrier air groups of the USS Saratoga, Princeton, Bunker Hill, Essex, and Independence. The attacks, which lasted through February 1944, destroyed two of Rabaul’s four airstrips, destroyed dozens of Japanese planes, and left Rabaul an isolated outpost that posed little danger to Allied operations in the area. In mid-February, Adm. Marc Mitscher’s Task Force 58, comprising four carrier task groups carrying more than 500 planes, launched a massive air and surface attack on Truk Lagoon in the Caroline Islands. With the support of seven battleships and numerous cruisers, destroyers, and submarines, TF58 destroyed 16 Japanese vessels, more than 250 planes, and nearly 200,000 tons of shipping. With Truk’s air defenses decimated, it became, like Rabaul, a toothless outpost, without hope of resupply or reinforcement.

advertisement

From the earliest days of the Orange plan, the Navy and Marine Corps had been exploring better ways of getting men and equipment across beaches in amphibious landings. The Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP) – the shallow-draft “Higgins boat” that had brought waves of allied troops to the beaches of Normandy – proved crucial to the Guadalcanal landings but nearly useless at Tarawa Atoll, where shallow reefs brought them to a halt and troops were forced to wade ashore under withering fire. The experimental Landing Vehicle, Tracked (LVT), the amphibious “Alligator” tractors originally designed for rescues in the Florida swamps and tested as cargo carriers at Guadalcanal, proved capable of traversing the Tarawa reefs, but there weren’t nearly enough. After Tarawa, the Marine Corps reconfigured its assault forces to include battalions of armored and cargo LVTs, along with companies of the wheeled amphibious craft, the DUKW (“the Duck”) that had also been used at Normandy. A full range of LVT variants were used in the campaign for the Marshall Islands, and DUKWs were used to cross the coral reefs in amphibious landings at islands such as Saipan and Guam.

Ships of the fighting fleet in December 1944 at Ulithi Atoll, a major staging and logistics base for the U.S. Navy during World War II. At middle, foreground to background, are the aircraft carriers USS Wasp, USS Yorktown, USS Hornet, USS Hancock, USS Ticonderoga, and USS Lexington, with more aircraft carriers, destroyers, cruisers, and other warships surrounding them.

National Archives Photo

A larger variation on the theme of the flat-bottomed Higgins boat, the Landing Craft, Mechanized (LCM), was used to bring light tanks ashore during amphibious landings. Since the LVT was a vehicle itself, it was later modified to become an “amtank.”

Troop mobility remained a significant challenge throughout the Pacific campaign, and a number of solutions were created. The Navy developed a specialized LST, or Landing Ship, Tank, a flat-keeled craft that could be beached to offload tanks, vehicles, cargo, and troops through a bow equiped with huge front doors. Other multipurpose amphibious craft included the Dock Landing Ship, or LSD, fitted with a well dock to transport and launch landing craft; and two types of attack transports: the APA (troop) and AKA (cargo) transports that carried their own fleet of landing craft aboard.

A small part of the U.S. Navy fleet steams along the coast of Leyte island during the invasion of the Philippines in October 1944. While not as warlike and impressive as the “murderers’ row” of U.S. Navy aircraft carriers and other warships in the top photo, the ships shown here – transports and cargo ships, oilers, and support vessels – were what kept the fleet moving and fighting.

National Archives Photo

Marine landing forces often faced fierce resistance from Japanese defenders who were dug into fortified positions. Reducing these defenses without unacceptable losses was a significant challenge. Kinetic weaponry – high-angle artillery, mortars, and pack howitzers – along with light armored vehicles helped to provide fire support from the beaches. But expeditionary forces found guns and rockets to be cumbersome and not as effective as needed for digging Japanese forces out of concrete bunkers, machine gun nests, and pillboxes. A suite of incendiary weapons – napalm bombs and portable or tank-mounted flamethrowers – proved dreadfully effective at dislodging or dispatching dug-in enemies. Mechanized flamethrowers, mounted aboard both Sherman tanks and LVTs, were used in amphibious operations from Saipan to Okinawa.

The U.S. military’s island-hopping campaigns gave the joint forces an unprecedented opportunity to project power across the globe by land, sea, and air. The terms “jointness” and “multi-domain operations” are rooted in the strategy and operations that unfolded in the Pacific war against Japan, and despite all that has changed in the 75 years since, the overwhelming successes of the island-hopping campaign offer several lessons that still apply: the importance of balancing offensive power with operational reach (unlike the overextended Japanese); of joint doctrine, training, and operations in multi-domain operations; and of staying on the technological cutting edge with investments in modernization.

The 2018 National Defense Strategy integrates these lessons in anticipating a different kind of multi-domain theater in the Pacific, a region that has reemerged as a 21st-century priority. It may still be true, as MacArthur once told Congress, that the Pacific Ocean and its island chains offer “a protective shield for all the Americas” – but not in the way he originally meant. Today, with Japan as a key regional ally, MacArthur’s statement takes on a significantly different meaning. Army Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, reaffirmed this in his visit to Tokyo in November 2019, when he met with Japanese leaders and reaffirmed that a free and fair Indo-Pacific region was “the No.1 regional priority for the United States military.”