32 minute read

Submarines at War: From the Turtle to U-boats, nuclear submarines, and unmanned systems

By Dwight Jon Zimmerman

For centuries, a nation's maritime might was defined by its surface navy, with the battleship being the epitome of gunship supremacy. The battleship’s surface suzerainty ended in the 20th century, supplanted in the air by aircraft carriers and underwater by submarines.

The submarine’s potential as a weapon of war was first demonstrated during the American Revolution in 1776 by David Bushnell, who invented the Turtle. His clam-shaped, man-powered submersible would sneak up to an unsuspecting enemy ship, attach an explosive charge, and escape before the explosive detonated. Bushnell’s Turtle was put to the test the night of Sept. 6, 1776. The quarry was the British man-o’-war, HMS Eagle, docked in New York Harbor. The captain, crew, and power plant performed in a precedent-establishing harmony of purpose as the Turtle made its way toward its anchored target. Not only did all work as one, they were one: Sgt. Ezra Lee. With head, hands, arms, legs, and feet in near-constant motion as he operated his boat, Lee reached the Eagle and attempted to attach his torpedo. His effort failed, and he was forced to retreat, his mission unfulfilled. Two other Turtle missions were also unsuccessful. Even so, the Turtle had demonstrated that attacks by a submersible were possible.

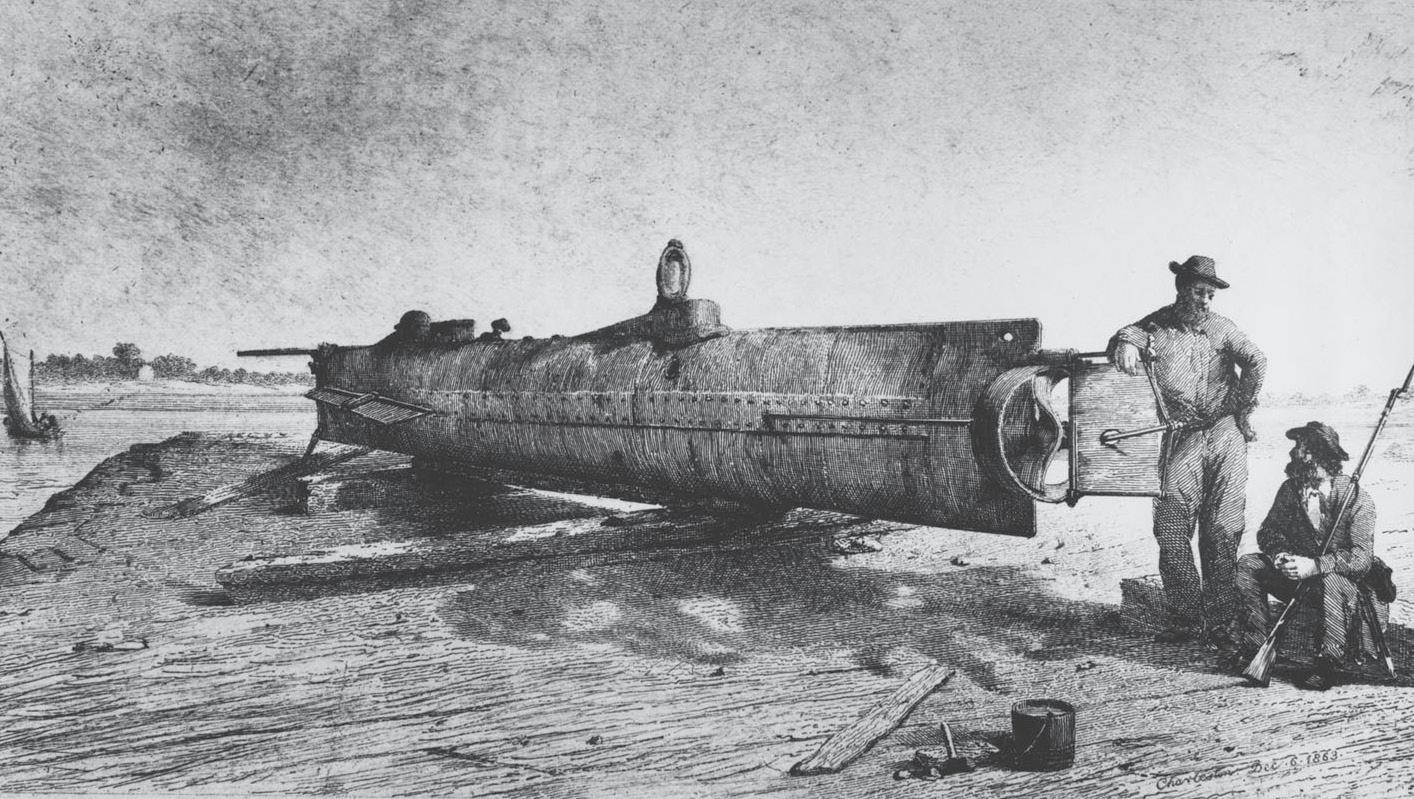

Drawing of the Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley. A small hand-powered submarine, Hunley was built privately at Mobile, Alabama, in 1863, based on plans furnished by Horace Lawson Hunley, James R. McClintock, and Baxter Watson. On Feb. 17, 1864, she sank USS Housatonic by detonating a spar torpedo against her side, but was also sunk herself.

The next significant event in the combat history of submarines occurred during the American Civil War. The Union blockade of Confederate ports – the Anaconda Plan – was having its effect in preventing supplies from reach ing Confederate ports. Necessity – in this case survival – being the mother of invention, the Confederate government encouraged any proposal that offered credible hope of breaking the blockade. One such response was the CSS H. L. Hunley, named after one of its main financial contributors and designers. The cigar-shaped craft, fashioned from a converted boiler, was 5 feet in diameter and powered by a crew that rotated hand cranks attached to a drive shaft.

On the night of Feb. 17, 1864, the Hunley embarked on its first mission. Slipping out into the dark water of Charleston Harbor, the Hunley’s orders were to lodge into the hull of an enemy ship a torpedo (mine) mounted at the end of a 15-foot spar protruding from the Hunley’s bow. After it had been attached, the Hunley would detach from the torpedo and, as it backed away, its skipper, Lt. George Dixon, would pull a rope trigger, detonating the explosive. The Hunley’s victim that night was the wooden-hulled USS Housatonic. The Hunley successfully buried the torpedo in the Housatonic’s hull, detonated the torpedo, and sank the ship. But the Hunley did not survive its history-making mission. For reasons unknown, the Hunley sank with all hands soon after its victim. Though spectacular historically, strategically the sinkings were non-factors regarding the war’s outcome.

The former German submarine UB-148 at sea, after having been surrendered to the United States. World War I showed how effective U-boats could be against a maritime nation, a lesson taken to heart and applied against the Allies in World War II.

Sinking of the Linda Blanche out of Liverpool, a painting by Willy Stöwer, depicts the attack by U-boat U-21 on the Linda Blanche during World War I. The Linda Blanche was sunk on Jan. 30, 1915, after allowing all crew and passengers to disembark, a practice that fell by the wayside as the war progressed.

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, submarines reached maturity as a strategic weapon of war. Though all the major world powers possessed submarines in 1914, the story of World War I submarine operations is dominated by Germany’s U-boats, which came close to single-hand edly knocking Great Britain out of the war – a remarkable achievement, because Germany had only 20 operational U-boats in 1914.

Their effectiveness was dramatically demonstrated on Sept. 22, 1914, less than two months after the start of the war. Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen in the U-9 attacked and sank three British cruisers, the Aboukir, Hogue, and Cressy. The action made Weddigen a hero, with the Kaiser awarding him the Pour le Mérite, Germany’s highest military decoration. The sinkings stunned the British. One commentator wrote, “What wonder that men the world over began to predict the abandonment even of the dreadnoughts, for all their weight of armor on their sides will avail them not a whit against attack from below. … [T]he submarine, and its scarcely less sinister coadjutor, the airship, may put an end to the … floating forts of steel which the Powers have been building.” Though battleships would still be constructed, the torch of naval power had been passed to the relatively small submarine.

U-boat operations were notable for their on-again, off-again adherence to rules of engagement (ROE) originally specified in the Declaration of Paris in 1856. The ROE de tailed the procedure under which a merchant vessel flying a belligerent’s flag could be sunk. Essentially the attacker had to deliver fair warning of its intent and then allow the vessel’s crew sufficient time to board life rafts and clear the ship. Only then could the warship sink it. Merchant ships under a neutral flag, even if they carried munitions for one of the belligerent powers, were exempt from at tack. Numerous diplomatic efforts were made to address the changes and developments in ships, weaponry, and technology, the last being the Declaration of London in 1909, which ended in failure. One reason was prescient ly observed by Baron Marschall von Bieberstein of the German delegation who noted the conference should not adopt rules “whose strict observance may be rendered impossible by the force of circumstances.”

The “force of circumstances” became tragic reality on May 7, 1915, when the British passenger liner Lusitania was torpedoed and sunk by the U-20. The fact that British registry had it listed as an armed merchant cruiser and that it was carrying rifle ammunition for the Allies was lost in the outrage felt in the then-neutral United States upon news that 128 American citizens lost their lives in the attack. Crisis diplomatic maneuvering between the American and German governments temporarily suspended U-boat operations and successfully forestalled America’s entry into the war that year.

Meanwhile, British submarines were making their mark. One British submarine hero was Max Horton, commander of the E-9, whose success in sinking iron ore ships transiting between Sweden and Germany caused the Baltic to be temporarily renamed “Horton’s Sea.” And, during the otherwise ill-fated Dardanelles campaign, exploits in the Sea of Marmara by Martin Naismith of the E-11, which included the sinking of a transport in the harbor of Constantinople, made him a legend.

Submarine E9 alongside at Reval, 1915, commanded by then-Lt. Cmdr. Max Horton. Horton’s success while commanding E9 was such that the Baltic was for a time referred to as “Horton’s Sea.” He also began the tradition of submarines flying the Jolly Roger flag upon returning from successful patrols.

Germany’s greatest U-boat captain was arguably Lothar von Arnauld de la Periére. In one four-week patrol in the summer of 1916 in the Mediterranean Sea, Arnauld’s U-35 sank 54 ships totaling 91,150 tons. What was unusual was that he used only four torpedoes – most of the ships were sunk by his deck gun. Arnaud, awarded the Pour le Mérite, would end the war as Germany’s submarine ace of aces with 194 ships sunk, totaling more than 450,000 tons.

In the final months of the war, a young U-boat officer proposed a new method of submarine operations, one that would have squadrons of U-boats launch coordinated attacks instead of independent, solo strikes. But Oberleut nant zur See Karl Dönitz in the U-68 was captured before he could test his concept.

Meanwhile, the United States had done little to prepare itself for possible entry into the conflict. So it was that its submarine force, like every other part of the military, was inadequate to the task demanded when America declared war on Germany in 1917. The U.S. Navy’s submarines had a negligible presence in World War I.

When World War I ended in 1918, the Central Powers had built a total of 375 U-boats. They had sunk more than 7,600 ships totaling more than 15 million tons. More than half the vessels sunk were British. Estimates predicted that if Germany had been able to deploy even 50 more U-boats, she would have won the war. Little wonder then that in the following years, Great Britain advocated the abolition of submarines and, when that failed, their strict regulation.

Despite a sincere belief that World War I was the “war to end all wars” and budget constraints caused by the worldwide economic collapse of the Great Depression, submarine design and development continued. When World War II began in 1939, Dönitz was the commanding officer of U-boat fleet that was composed of 22 boats suit able for operations in the Atlantic – only two more than the Kaiser’s fleet in 1914 and far below the estimated 300 a Kriegsmarine study projected were necessary to defeat Great Britain. But Dönitz was unable to wait for more of the Type VII and Type IX U-boats to arrive.

U-278, a Type VIIC German U-boat, photographed from a long-range Liberator bomber during World War II. U-278 survived World War II, unlike so many other U-boats.

Dönitz gave one of his promising commanders, Günter Prien of U-47, a mission designed to spectacularly challenge the might of the Royal Navy. On the night of Oct. 12-13, 1939, less than a month and a half after the start of the war, Prien and the U-47 entered the Royal Navy base at Scapa Flow and sank the battleship Royal Oak. Prien and the U-47 returned to a hero’s welcome. The Battle of the Atlantic had begun in earnest.

Another U-boat captain was Otto Kretschmer, whose successes early in the war also marked him for distinction. His success, though, was achieved despite a consistent failure of his torpedoes. During one six-month period that included 97 days at sea, Kretschmer’s U-23 fired 23 torpedoes, but 15 of them failed. Kretschmer’s frustration became so great that after capturing a supply ship and forcing the crew to evacuate, he conducted torpedo tar get practice in order to determine the cause of failure. He reported that “the magnetic firing mechanism had to be reset every time we entered a new zone.” Dönitz quickly supplied his U-boats with reliable torpedoes.

The fall of France in June 1940 ushered in a period of the war in the Atlantic the U-boat force called the “Happy Time.” Now with bases extending from the Bay of Biscay to above the Arctic Circle, the U-boats could, and did, range at will. The top three U-boat skippers, Prien, Kretschmer, and Joachim Schepke, would lead the way in tallying 1,395,298 tons of shipping sunk, amounting to an average of three freighters or tankers sunk per day. All this was accomplished by only 11 to 13 U-boats. It was a damning indictment at how ill-prepared the British admiralty was. Even the adoption of the convoy system provided little help during this period, for anti-submarine warfare escort construction had been ignored. Dönitz believed that Germany could win the war if his U-boats, working with Luftwaffe bombers, could sink 700,000 tons of shipping a month. As 1941 dawned, it appeared very likely that this goal would be attained.

But Dönitz would not completely have his way. The Brit ish had broken the German Enigma code, and its use was slowly making a difference. In one 10-day period in March 1941, Dönitz lost his top three skippers. Prien and Schepke fell in action, and Kretschmer and his crew were captured. Even so, his “wolf pack” tactics, conceived in World War I, were making his U-boats collectively more dangerous than they were individually. One of the high points of U-boat and Luftwaffe combined operations was the attack on convoy PQ-17 in June and July of 1942, where 24 merchantmen bound for Murmansk were sunk. Though the U-boats would experience another “Happy Time” along the East Coast of the United States in 1942, America’s industrial might soon had in quantity such anti-submarine assets as K-class blimps, long-range bombers, destroyer escorts, and escort carriers. These, plus the use of convoys and sophisticated sonar, would reduce the U-boat threat almost to the level of a manageable nuisance by D-Day.

Compared to World War I, the U.S. submarine fleet was in substantially better condition when it went to war in 1941. Though the S-class boats harbored in bases in the Philippines, Pearl Harbor, and elsewhere were outdated, they were still useful. And new submarine production was well underway, promising even better boats for the fleet in the not-too-distant future.

USS Wahoo (SS 238) off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, July 14, 1943.

With the U.S. Pacific Fleet crippled following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the submarines assumed an immediate importance in fighting against Japanese offensives that reached as far south as the Dutch East Indies, as far east as Midway, and as far west as India. Overseeing the U.S. Navy’s submarines and crews in the Indian and Pacific oceans was Commander, Submarine Force Pacific Fleet (COMSUBPAC) Vice Adm. Charles Lockwood. “Uncle Charlie” Lockwood became one of the outstanding theater commanders of the war. His concern for the welfare of the men under his command and their boats earned their enduring love and respect. Whenever a boat returned from patrol, Uncle Charlie made a point of always being at the pier to greet the crews.

During the first year of the war, the submariners’ effectiveness was hampered by two things. One was the peacetime doctrine of frugality in expenditure of torpedoes, and caution and deliberation in attack that some skippers were unable to overcome once the real shooting war started. The other was faulty torpedoes. The latter problem was cogently expressed by an exasperated Lt. Cmdr. Dudley “Mush” Morton, skipper of the Wahoo and one of the early stars in the submarine service. During an attack on a convoy, he reported that of three torpedoes fired, one exploded prematurely, one ran wild, and the third scored a direct hit on its target, with his sound officers recording a definite “thud with a dud.”

In addition to exploding prematurely, or not at all, torpedoes also ran too deep or too shallow. In one harrowing instance, a torpedo even turned on the submarine that launched it (the submarine fortunately escaped disaster). Worse, there was no consistent pattern to the assorted malfunctions. Complicating things further was bureaucratic intransigence from the Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance that claimed, despite mounting evidence that included field tests conducted by Lockwood, that the fault lay with the submariners and not with the torpedoes. Many submarine commanders would suffer relief and transfer before the problems with the Mark VI magnetic exploder, the depth control mechanism, and the contact exploder were identified. Almost two years passed before new torpedoes correcting the design flaws reached the fleet.

The torpedoed Japanese destroyer Yamakaze sinking on June 25, 1942, approximately 75 miles southwest of Yokahama Harbor, Japan, photographed through the periscope of the U.S. Navy submarine USS Nautilus (SS 168).

Yet, despite being hobbled by an unreliable main battery, submarine skippers still managed to sink ships, with some earning the Navy Cross and a few receiving the Medal of Honor. When Mush Morton took command of the Wahoo, he told his crew, “We will take every reasonable precaution, but our mission is to sink enemy shipping.” When the Wahoo returned from the first patrol under his command on Feb. 7, 1943, eight small Japanese flags, signifying eight sunken ships (postwar analysis would lower that total), were flying from a halyard, and an upended broomstick, signifying a clean sweep, was lashed to the periscope. Morton and the Wahoo became famous. Later, during a patrol in the Sea of Japan, the Wahoo, after sinking three freighters and a passenger ship, failed to radio a scheduled report on Oct. 23, 1943. With sadness, Lockwood concluded that the Wahoo had been lost. The sunken submarine was found in 2006, lying in about 213 feet (65 meters) of water in the La Perouse (Soya) Strait between the Japanese island of Hokkaido and the Russian island of Sakhalin.

Lt. Cmdr. Lawson P. “Red” Ramage of the Parche was among the first skippers to go into action using an American version of the wolf pack tactic. He achieved individual distinction during a mission at the end of July 1944 in an action later called “Ramage’s Rampage.” After conducting a coordinated attack on a Japanese convoy, Ramage successfully maneuvered the Parche into the middle of the cluster of ships. Under Ramage’s direction from the conning tower, the surfaced Parche fired torpedoes and maneuvered with such aggressive skill that the disoriented Japanese escorts wound up shooting at each other in their attempts to hit the Parche. Credited with the sinking of several ships, Ramage received the Medal of Honor. Lt. Cmdr. Dick O’Kane, skipper of the Tang, was responsible for sinking 31 enemy ships before his capture, making him the highest individual American scorer in the war. O’Kane survived his experience as a prisoner of war and eventually received the Medal of Honor.

A submarine officer peers through the periscope of a U.S. Navy submarine during World War II.

Another Medal of Honor recipient was Cmdr. Joseph Enright of the Archerfish. In November 1944, the Archer fish scored the biggest kill ever made by a submarine when it torpedoed the 72,000-ton aircraft carrier Shinano just outside Tokyo Bay.

But sinking ships was only one part of the submarine’s many missions in the war. The Nautilus and Argonaut were tasked with carrying Carlson’s Raiders on the daring raid on Japanese installations on Makin Atoll in August 1942. In so doing they became the first submarines to serve as troop transports in what would later be called a special operations mission. Other submarines would be deployed on missions that included the drop off, pick up, and sup plying of coast watchers and other agents, the retrieval and rescue of downed pilots and air crews, reconnaissance, and mine laying.

In his final report of the war in 1945, Lockwood stated that U.S. submarines had sunk 4,000 Japanese ships total ing 10 million tons. Three-fifths of the Japanese merchant fleet had been sent to the bottom of the sea. The cost of this success was high. Fifty-two boats, 374 officers, and 3,131 enlisted men, constituting a 22 percent casualty rate, had been lost. Though this was the highest loss rate of all the services, the result was an achievement that all but iso lated the Japanese Home Islands. So effective had the U.S. Navy’s submarines become that the waters around Japan were virtually owned by American submariners.

The U.S. Navy nuclear submarine Skate (SSN 578), at the North Pole, 1962. Nuclear power transformed submarine design and operations.

The end of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War opened a new chapter in the use of submarines. With the installation of nuclear power plants, a submarine’s ability to stay submerged was now limited only by the amount of supplies that could be stored for the crew.

Naval operations in the Korean War and Vietnam War were largely conducted by the surface fleets. Submarines made their mark on the strategic side as stealthy, mobile platforms for ballistic missiles and in the black operations of intelligence gathering. The submarine’s contribution to the latter was so extensive and so valuable that most of the information about their missions is still classified. With a wide range of ultra-sensitive listening devices, and protected by increasingly ultra-quiet technology, submarines eavesdropped on radio transmissions, tapped into undersea cables, and photographed boats and ships sub merged and on the surface in training operations and at ports. For some of the submarines, the waters of the Barents Sea and the Sea of Okhotsk became more familiar than the waters of their homeports.

When Iraq invaded Kuwait on Aug. 2, 1990, the first stage of the international coalition response led by the United States was initiated. Operation Desert Shield saw deployment of military ground and air assets to the Middle East, primarily to Saudi Arabia, and a naval cordon stationed in the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. The most visible aspect of this naval cordon was the carrier battle groups. But nuclear submarines were also on station and ready to strike. On Jan. 17, 1991, Operation Desert Storm was launched. The Los Angeles-class submarine Louisville in the Red Sea was the first to fire Tomahawk cruise missiles, and together with Pittsburgh, launched 12 Tomahawks (the Louisville eight and the Pittsburgh four) at Iraqi targets. Other attack sub marines, both American and from other nations, stood guard over the incredible amount of cargo ships carrying war supplies.

America’s submarines made a larger contribution 12 years later in Operation Iraqi Freedom, which finally saw the end of Saddam Hussein’s regime. This time, a dozen Los Angeles-class nuclear-powered submarines participated. The Cheyenne fired the first Tomahawk shot at a Baghdad bunker that was believed to be occupied by Iraq’s ruler. Other submarines stationed in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, and the Arabian Sea included the Columbia, Providence, San Juan, Newport News, Boise, Montpelier, Key West, Augusta, Toledo, Pittsburgh and Louisville. The submarines fired a large share of the 802 Tomahawks aimed at strategic Iraqi targets.

The Russian Yasen-class cruise missile submarine Severodvinsk.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 resulted in years of neglect and reduction of the Russian navy. Overall it shrank to about one-fourth the size of its Soviet forebear, and its submarine force went from a high of almost 400 boats in 1985 to a low of just 63 in 2008. Maintenance and training were hit just as hard. Then, in 2008, the Russian navy dramatically began to rebuild.

Aging ships were retired and replaced, enlistment and training of personnel were overhauled, and new generations of ships of all types began being built. The result in the Russian submarine fleet has been dramat ic. After a series of delays, the first Yasen-class nuclear attack boat Severodvinsk underwent sea trials in Sep tember 2011 and became operational in 2014. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) rates it as being quieter than the Los Angeles-class boats, but not as quiet as the Seawolf- and Virginia-class submarines. Simulta neously, Russia went forward with construction of the Borei-class nuclear ballistic missile submarines. Yury Dolgorukiy, the first in the class, passed sea trials in 2010 and was commissioned in 2013.

In 2010, Russian shipyards began construction of the Novorossisk, the first of a class of up to 13 Varshavyanka-class diesel-electric attack submarines that incorporate state-ofthe-art stealth technology. In a November 2013 press conference, the Novorossisk’s captain, Konstantin Tabachny, said, “Our potential opponents call it the ‘Black Hole’ due to the very low noise emission and visibility of the submarine. To be undetectable is the main quality for a submarine. And this whole project really fits its purpose.”

And as the new boats were commissioned, Moscow began increasing global submarine operations. In March 2015, Adm. Viktor Chirkov, commander in chief of the Russian navy, stated, “From January 2014 to March 2015 the intensity of patrols by submarines has risen by al most 50 percent as compared to 2013.” These patrols have extended into areas once patrolled by its Soviet counterparts.

For example, in late 2012, a Sierra II-class nucle ar-powered attack submarine was discovered just 200 miles off the eastern coast of the United States. A more sobering incident occurred in the opening months of 2014. A Russian Vishnya-class Auxiliary General Intelligence (AGI, or electronic reconnaissance) ship together with an ocean-going tug was identified operating in international waters off the coast of Florida near U.S. Navy air and submarine bases. Analysts believed that the AGI was using sophisticated computer technology and sensors to track submarines through the subtle changes in the surface of the sea caused by the transit ing submerged boat.

Meanwhile in the waters around Europe in October 2014, the Swedish navy detected what it believed to be a “foreign submarine” conducting operations in its territorial waters of the Baltic Sea. And on April 27, 2015, vessels in Finland’s navy detected a “possible underwater object” inside its territorial waters. Though neither the Swedish nor Finnish navies were able to identify or force the objects to surface, suspicions are that they were Russian submarines, something Moscow officially denies.

In October 2016, Britain’s Royal Navy reported it detected two Akula-class nuclear attack submarines in the Irish Sea and one Kilo-class submarine in the English Channel, all en route to support Russian operations in Syria. A naval source stated the “Russian submarines made it clear that they wanted us to know they were there.”

These and other similar actions by the Russian navy are part of what Adm. James Foggo III, commander of United States Naval Forces Europe - Africa and of Allied Joint Force Command Naples, has called the “Fourth Battle of the Atlantic” (the others occurring in World Wars I and II and the Cold War).

In a June 2016 article in Proceedings, he wrote, “Once again, an effective, skilled, and technologically advanced Russian submarine force is challenging us. … Not only have Russia’s actions and capabilities increased in alarm ing and confrontational ways, its national-security policy is aimed at challenging the United States and its NATO allies and partners.”

He noted that this Russian push-back has created an “arc of steel” that runs from the Arctic Ocean south though the Baltic Sea and down to the Black Sea. Already Russia has imposed its will over the coastal waters of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, and has challenged NATO power-projection capabilities elsewhere.

“We’ve seen the creation of new classes of all sorts of submarines and ships,” Foggo told the Atlantic Council in 2018. “I’m more concerned with submarine warfare – Dolgorukiy, Severodvinsk, Petersburg, the six new Kilos now operating in the Black Sea, and two of which have remained in the Mediterranean and have launched the Kalibr missile from the Mediterranean. The Kalibr missile is an impressive missile; a land attack cruise missile, and if launched from any of these bodies of water, including the Caspian … can range any one of the capitals in Europe. It’s important that we have situational awareness and know what the Russians are doing in the undersea space at all times.”

In October 2019, Norway reported that it had discovered 10 submarines of the Russian northern fleet operating in North Atlantic waters off its coast. It was the largest gathering of Russian submarines since the Cold War.

The Russian Boreiclass submarine Yuriy Dolgorukiy at the mouth of the White Sea in 2010, part of a new era of Russian submarine technology and capability.

Further evidence of the Russian navy’s increased capability occurred on Oct. 30, 2019, when the SSBN Prince Vladimir, the first upgraded Borei II-(A)-class submarine, stationed in the White Sea, test-fired while submerged an SS-N-32 Bulava ballistic missile that successfully hit its target a continent away on the Kura test range on the Kamchatka Peninsula. This was part of the submarine’s final validation trials. The Prince Vladimir is the first of a planned five SSBNs of the Borei II-(A)-class. Two are presently under construction and scheduled to be delivered in 2026 and 2027. Part of the Navy’s response has been to reactivate the 2nd Fleet, covering the U.S. East Coast and the North Atlantic, which had been deactivated in 2011 due to a perceived decline of Russian navy ambitions and operations.

The U.S. Navy faces a similar challenge in the Pacific with the “new kid on the blue water navy block” – the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) – and everyone’s favorite rogue nation, North Korea.

Up until the 1980s, the Chinese navy was a littoral force. That began to change in the latter half of the 1980s, when the government embarked on a ship-building and buying program designed to give its navy blue-water capability. China possesses the world’s fastest-growing navy and the most powerful navy in the region, with around 400 surface combatants, submarines, amphibious ships, patrol craft and specialized types, according to Reuters. China has used its navy to buttress its sovereignty over resource rich regions in the China Sea claimed in whole or in part by other regional nations. The territories in dispute include the Paracel and Spratly island chains, the Scarbor ough Shoals, and other outcrops, atolls, sandbanks, and reefs. And it plans a regional force powerful enough to forestall any attempt by the U.S. Navy to intercede.

To further its claim, China transformed several reefs in the South China Sea into man-made island military bases. To raise its surface fleet’s profile, China has invested in aircraft carriers. The first was the Liaoning (the former Varyag, an Admiral Kuznetsov-class carrier purchased from the Ukraine), regarded by experts as more of a show piece political statement. More serious are several types of carriers under construction or development. But the PLAN’s force acknowledged as a genuine strategic threat is its submarine fleet, one with second-strike nuclear ballistic missile capability. The government has repeatedly demonstrated that it is not afraid to flex that growing submarine muscle.

A Chinese Song-class submarine. One surfaced within five miles of the carrier Kitty Hawk while she was operating in the Pacific in 2006.

Examples of that muscle-flexing include the October 2006 Kitty Hawk incident, in which a Song-class diesel attack submarine shadowed the aircraft carrier’s battle group undetected before surfacing within torpedo range of the Kitty Hawk, numerous passages of Chinese submarines of a variety of types travel ing through or just beyond Japanese territorial waters, and the tailing of the USS George Washington in October 2008 by two submarines – a Song-class boat and a Han-class nuclear powered sub – during the carrier’s voyage from Japan to South Korea. In 2014 China deployed its nuclear-powered submarines for the first time ever in the Indian Ocean. One such mission involved a joint naval exercise with Iran and another involved an anti-piracy operation around the Horn of Africa.

In September 2016, the Chinese and Russian navies conducted Joint Sea 2016. What set this exercise apart from previous ones was that it was held for the first time in the South China Sea. The size of its participation put the region on notice that Russia is also expanding its na val presence in the Pacific Rim.

Then, in one of the most provocative actions thus far, in December 2016, a Chinese warship seized a U.S. Navy underwater drone called a “glider” operating in international waters off Subic Bay in the Philippines. Launched by the USNS Bowditch, a civilian-crewed oceanographic ship operated by Military Sealift Command, the glider typically collects unclassified data such as water temperatures and salinity levels. The warship intercepted the glider before the Bowditch could recover it and refused to release the drone despite repeated radio requests to do so. Following a démarche issued by the State Department, the drone was returned.

Experts agree that China’s expanding naval program and actions are part of an emerging strategy designed to assert its power and blunt or thwart U.S. intervention in the Pacific Rim. China now has the largest attack submarine fleet in the world. Its Jin-class nuclear powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) are equipped with JL-2 nuclear ballistic missiles with a range of about 4,000 nautical miles. This gives China the capability of launching a nuclear missile attack on the West Coast of the United States from locations deep within the Pacific Ocean. And new, more technologically advanced submarines, such as the Type-095 Tang-class attack submarines under construction at the Bohai Shipyard, are expected to be operational very soon.

On the defensive side, China is developing an “Underwater Great Wall” of UUVs, other maritime robots and seafloor sensors tailored to defend naval bases with surveillance UUVs, counter torpedo defenses, and a net worked minefield of armed and smart UUVs supported by automated underwater listening posts.

North Korea upped the maritime ante in the region when on May 9, 2015, the Korean People’s Army Navy announced the successful submarine test-launch (apparently from a submersible barge) of a “Polaris-1” ballistic missile. North Korea has about 70 submarines of all types, from midget to diesel-electric ballistic missile subs. It’s a littoral force possessing a modified Soviet-era fleet not technologically advanced enough to avoid detection by the U.S. Navy. That said, the country’s ballistic subs could hide long enough to launch a missile attack against South Korea or Japan with little or no warning.

The U.S. Navy has responded to China’s and North Korea’s actions in a variety of ways. Joint exercises in the region have increased, as have plans to more closely work together with regional nations wishing assistance in asserting their sovereignty and rights of passage. The vast undersea microphone network originally designed to track Soviet submarines is be ing updated. With regard to its submarine force, the U.S. Navy has assigned 60 percent of its undersea force to the Pacific. In 2015, Submarine Squadron 15, stationed at Naval Base Guam then consisting of the Los Angeles-class fast-attack submarines USS Oklahoma City, USS Key West, and USS Chicago, was reinforced with a fourth Los Angeles-class sub, the USS Topeka. And the Pacific submarine fleet has been reinforced with the new Virginia-class nuclear submarines USS Texas, Hawaii, North Carolina, Mississippi, Illinois, and Missouri.

And just as drones have transformed operations in the air and on land, so too are drones, called unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) and autonomous under water vehicles (AUVs), reshaping operations under water. The 2004 The Navy Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (UUV) Master Plan, an update of a 2000 document, identified and prioritized nine capabilities for drones: ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance), mine countermeasures, ASW, inspection/identification, oceanography, communication/navigation network node, payload delivery, information operations, and time critical strike. Regularly updated, it has served as a blueprint for the Navy’s expanding development and use of UUVs and AUVs.

The Los Angeles-class attack submarine USS Chicago (SSN 721) at periscope depth off the coast of Malaysia during the seventh annual Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training (CARAT) 2001 exercise. Along with building the most stealthy and capable submarines possible, such as the Virginia-class submarines now replacing the Los Angeles class, the U.S. Navy continues to work with allies and partners to ensure the safety and maritime strategic interests of the nation.

If the U.S. Navy’s submarines are regarded as a force multiplier weapon system (and they are), then UUV and AUV drones are a huge force multiplier for submarines. A UUV/AUV-equipped submarine can simultaneously con duct multiple missions, some many miles from the boat itself, literally being in many places at one time. For example, such a submarine deployed in the South China Sea off the Spratly Islands could have one drone conduct offshore reconnaissance and another monitor traffic through the Balabac Strait while the submarine shadows PLAN fleet activity off the Spratlys.

In 2015 the Navy began testing the deployment of Remus 600 UUVs from Dry Deck Shelters aboard Virginia-class submarines. Manufactured by Hydroid, a division of Kongsberg Maritime, the Remus 600 is an AUV equipped with dual-frequency side-scanning sonar technology, synthetic aperture sonar, acoustic imaging, video cameras and GPS devices. Unlike many UUVs that have to be controlled by a human operator, the Remus 600 can be programmed to operate independently. The 11-meter-long Dry Deck Shelter enables the boat to launch divers or UUVs/AUVs while submerged, and other UUVs are being developed for launch and recovery from tubes in the Virginia Payload Module.

Drones in a variety of shapes, sizes, and capabilities are at varying stages in the pipeline. In 2017 the U.S. Navy made history when it commissioned Unmanned Undersea Vehicle Squadron 1 (UUVRON-1), the first ever naval squadron composed entirely of undersea drones. The squadron is tasked to conduct a variety of operations and serve as a test bed for the development and deployment of next generation unmanned underwater vehicles.

SEALs and divers from SEAL Delivery Vehicle Team (SDVT) 1 swim back to the guided-missile submarine USS Michigan (SSGN 727) during an exercise for certification on SEAL delivery vehicle operations in the southern Pacific Ocean. The exercises educated operators and divers on the techniques and procedures related to the delivery vehicle and its operations.

Past missions have included mine clearing, surveil lance, and ocean floor mapping, augmenting, not replacing, manned Navy missions. The squadron will be particularly useful on missions that are too dangerous to put men on, or those missions that are too mundane and routine but important – like monitoring.

Literally the biggest news in the UUV world is the Orca Extra Large Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (XLUUV). As part of the Navy’s rapid acquisition program, it awarded Boeing a contract to deliver five XLUUVs and assorted support elements.

Boeing’s Orca is based on its Echo Voyager, an XLUUV created for testing purposes only. Up to 85 feet long and weighing as much as 50 tons, it is designed to have a range of 6,500 nautical miles. Among its features is a payload bay capable of carrying a wide variety of cargo, from weapons such as torpedoes and mines, to reconnaissance equipment and supplies.

Also on the rapid acquisition program is the smaller Large Displacement Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (LD UUV), called Snakehead. The Snakehead LDUUV is designed for intelligence, surveillance, and mine countermeasures missions, and is based on a modular, open architecture that will give the Navy flexibility to quickly modify it in response to new mission requirements. Specifications call for the Snakehead to be capable of conducting missions longer than 70 days in open ocean and littoral seas, being fully autonomous, long-endurance, and land-launched with advanced sensing for littoral environments. Prototypes have undergone trials, and production is slated for 2020 and 2021. The Office of Naval Research, for example, is developing an AUV capable of conducing missions longer than 70 days in ocean and littoral seas. The AUV would be capable of being launched from a variety of platforms and its mis sions would include IRS, ASW, mine counter measures, and offensive operations.

The Seawolf-class fast-attack submarine USS Connecticut (SSN 22) transits the Pacific Ocean during Annual Exercise (ANNUALEX 21G). Only three Seawolf-class submarines were constructed before giving way to the Virginia class.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are also being tested and developed, such as Switchblade, a tube-launched aerial drone that can operate from a submarine. Manufactured by AeroVironment, it is a battery-powered UAV capable of carrying an explosive warhead or an ISR package, and was successfully launched from a U.S. Navy submarine’s trash-disposal unit while the submarine was at periscope depth. In 2013 the Naval Research Laboratory also successfully launched a Sea Robin XFC from a submerged submarine.

The U.S. Navy and its allies are working aggressively to hone ASW skills that had atrophied in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Along with much improved technologies and new classes of ships and submarines, interoperability and cooperation between navies has moved to the forefront. International naval exercises such as Dynamic Mongoose (North Sea and Norwegian Sea), BALTOPS (Baltic Sea), Dynamic Manta (central Mediterranean Sea), and Sea Breeze (Black Sea), amongst others, are either entirely focused on or include aggressive training in coordinated ASW operations.

Submarines began as a naval novelty. By World War II, they had become such a force to be reckoned with that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill publicly confessed that the war against the U-boats was the only war he feared. During the Cold War, they achieved extraordinary distinction in intelligence operations. De spite competition from other nations’ fleets, U.S. Navy submarines’ ability to reveal their presence only when launching attack remains unmatched. And now with drone UUVs and AUVs becoming available, the ability to protect the United States’ maritime strategic interests will only get better for the branch of the Navy known as the “Silent Service.”