By Brian Walker

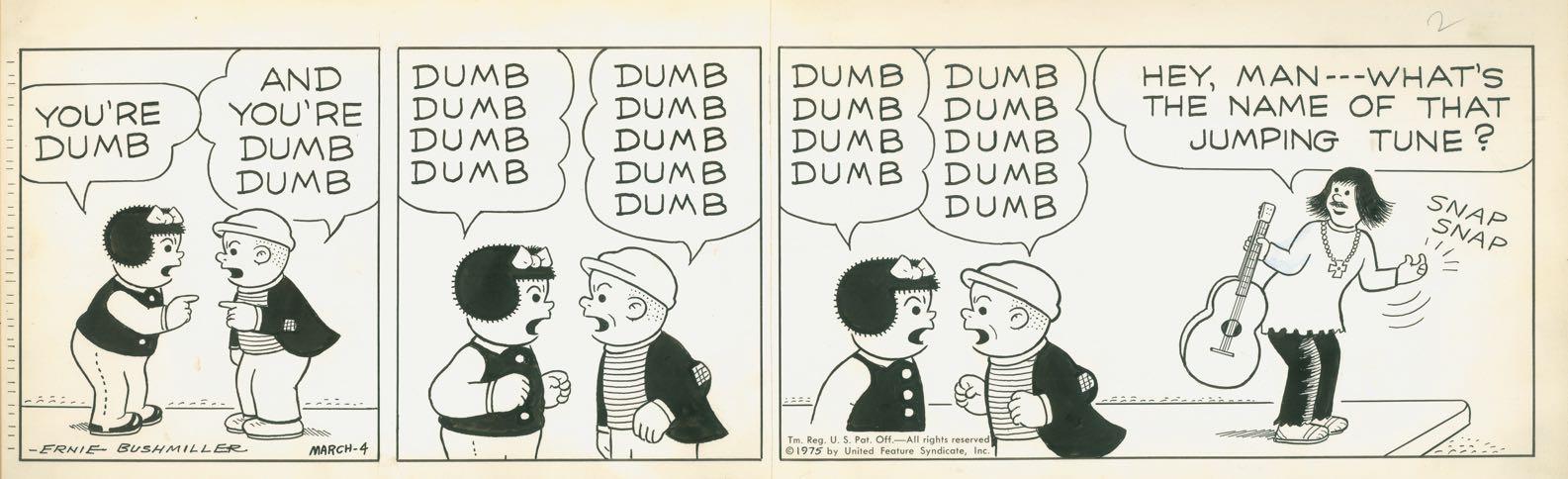

Ernie Bushmiller rarely did interviews and never wrote a revealing memoir. His work stood by itself, and like a true professional he didn’t let his own opinions and interests interfere with the function of his creation. A devotee of classical literature, Ernie’s advice to young cartoonists was to “dumb it down.” He understood that a comic strip is a medium of mass entertainment – that its success depended on communicating to the widest audience. He purposely wrote his strip for the common people of the world. This unpretentious egalitarianism is exactly why many cultural elitists despise Nancy They miss the point. To appreciate the perfection of Bushmiller’s creation, readers have to let their defenses down, step out of the role of critic, and accept it for what it is. A comic strip, pure and simple.

Ernest Paul Bushmiller was born in the south Bronx, at 633 East 137th Street on August 23, 1905. “When I was a small child,” he remembered, “we lived in a poor neighborhood in a cold water flat with gas lights. Although we were poor, we ate well and always were secure in the knowledge that our parents loved us and

we loved them.” He had two sisters, one younger and one older, and his parents were both recent immigrants. Ernest Bushmiller Sr., Ernie’s father, was born in 1874 in Germany, the youngest of six children. His father, a high school teacher, and his mother, a newspaper reporter, both died when he was less than twoyears-old, leaving him in the care of a semi-senile grandmother. After she died, Ernie Sr. left for America at the age of fifteen.

Elizabeth Hall, Ernie’s mother, was the daughter of Irish Protestants who lived in a thatched-roof farmhouse in Northern Ireland. All three of her brothers were policemen in Belfast. She immigrated in 1894. Ernie’s parents met on the streets of New York.

His father struggled to support the family working as a bartender and selling life insurance. He also gave humorous chalk-talks at Tony Pastor’s vaudeville theater on 14th Street and was a voracious reader with an impressive knowledge of history and literature. He was a major influence on his son and always encouraged his artistic interests.

privately-published multipage picture-stories were widely distributed and wildly impactful, leaving the world a new art form in their wake.

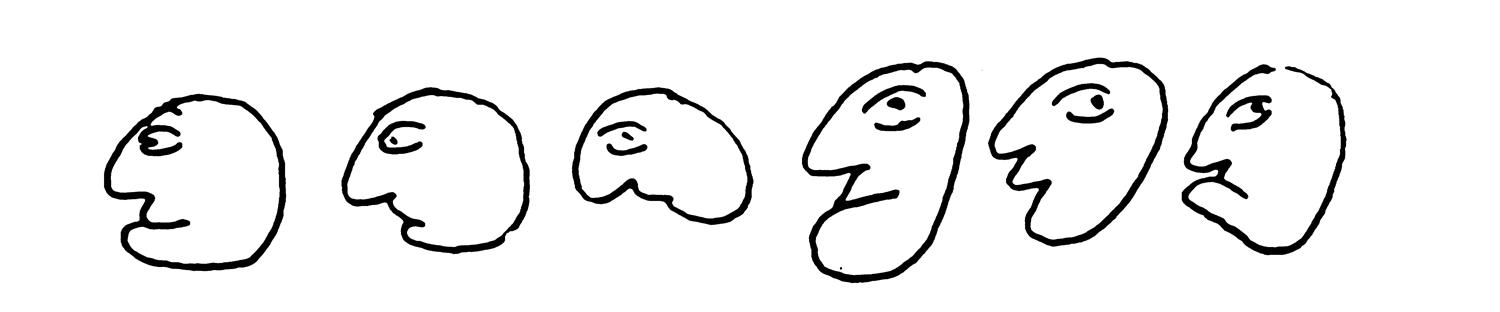

In his Art and Illusion (1960), E.M. Gombrich assesses Töpffer’s revolutionary ideas on writing with pictures. Gombrich tells us that from nearly out of nowhere “…Töpffer comes out with his psychological discovery—you can evolve a pictorial language without any reference to nature, without learning to draw from a model. The line drawing, he says, is purely conventional symbolism…Moreover, the artist who uses such an abbreviatory style can always rely on the beholder to supplement what he omits. In a skilled and complete painting, any gap will be disturbing; in Töpffer’s style these elliptic expressions are read as part of the narrative.” Rodolphe Töpffer, from the“Essay du Physiognomie” (1845)

“Discover expression in the staring eye or gaping jaw of a lifeless form, and what might be called ‘Töpffer’s law’ will come into operation—it will not be classed just as a face but will acquire a definite character and expression, will be endowed with life, with a presence. If there is a hierarchy of clues to which we react instinctively, expression will surely trump light. For any drawing of a human face, however inept, however childish, possesses, by the very fact that it has been drawn, a character and an expression… All he must do is to vary his scrawl systematically.”

“Vary his scrawl systematically” is precisely what Ernie Bushmiller did so methodically, for so long. In fact what we have come to think of as “iconic” Nancy took many decades to distill down to its quintessential Nanciness. But to what end? Ever in search of the “perfect gag,” this compulsive craftsman simultaneously sought the perfect gag’s perfect vessel, incrementally adjusting his marks over the years with the cool, patient skill of a safecracker. Once the tumblers clicked and perfection revealed itself, he stuck with the winning combination until the end.

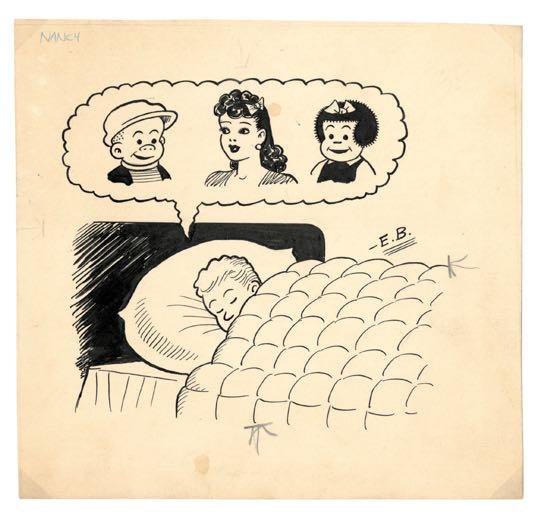

The Dawn of Nancy World, meet Nancy’s face. All of the basic elements arrived together on day one, panel 3: dots for eyes, intersecting ovoid shapes for upper and lower skull, and the dense frizz crowned with a large bow. While all these components would, in time, receive considered revisions, Nancy’s nose began as (and would always remain) a pencil-thin black slot.

Before introducing Nancy as the wisenheimer niece to straight-aunt Fritzi Ritz, Bushmiller tried out several other youngsters for that role, all nephews, male cousins, or boyish factotums, all with different facial structures than Nancy, particularly in that key area between the eyes and mouth. In fact, it is hard to find any character who appeared in the Fritz Ritz strip prior to Nancy (or any other comic strip for that matter) who possessed such a singularly linear nasal appendage. Was this the magic element that caused readers to clamber for more Nancy? We await the inevitable PhD theses.

Nancy began her comics career as a walk-on in another woman’s feature, a precocious young relative (with the visual emphasis on young) who dropped in now and again to ruffle adult feathers and exit stage left. The public cheered, and her presence in the strip soon became a permanent living arrangement. Accordingly, her delineation would now demand consistency and distinction. This crosshatch hairdo experiment did not last too long, and it points to how emblematic her hair was soon to become. With all the other basic ingredients in place, yet without those trademark inkblot earmuffs, well, it just ain’t quite Nancy. Functional as well as stylish, that solid black shape would soon help comics readers to swiftly locate and track their favorite character’s daily antics. (And imagine how many cumulative man hours Bushmiller was saved from all that fussy, weaving pen-work; day after day, decade after decade.)

In June 1938 the comic strip formerly known as Fritzi Ritz suddenly became known as Nancy and a star was born. Now complete with aforementioned blot, this is beginning to feel like the sassy, self-possessed kid that we could instantly pick out on any page of funnies. And yet, Darwin scholars take note; there is also an unmistakable simian quality here in the protruding brow and furry fringe. Nancy’s features seem uncomfortably

Definitely my favorite merchandise from the 1990s are these four limited edition cookie jars, made by “Pottery by JD” out of Palm Coast, Florida. The Sluggo Head cookie jar is very rare.

Musical figurines were released by Schmid Bros. Inc. in 1968. When you wind them they rotate and play “Second Hand Rose.” The company also made Nancy musical drinking mugs, but the music box takes up so much room in the cup, there’s hardly any room for the beverage.

“Sluggo” and “Sluggo’s Girl Friend” are soft vinyl dolls that come in two sizes and whistle when you squeeze them. Their hands have little notches to hold lollipops. When you find these dolls now, they can be weirdly sticky. From Dreamland Creations, 1955. A photo of Ernie with these dolls, and their lollipops, is on page two.