India’s cow economy Democracy in Africa: slipping backwards Bureaucrats, meet algorithms Revenge fantasies in country music AUGUST 20TH– 26TH 2016

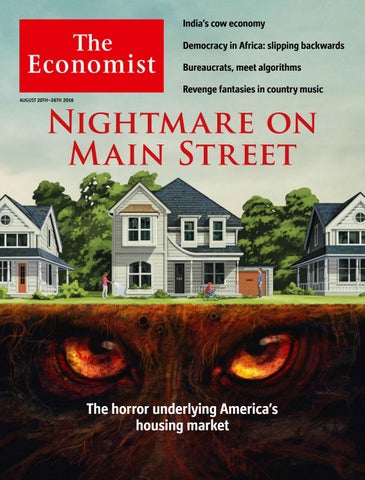

Nightmare on M ain Street

The horror underlying America’s housing market

India’s cow economy Democracy in Africa: slipping backwards Bureaucrats, meet algorithms Revenge fantasies in country music AUGUST 20TH– 26TH 2016

Nightmare on M ain Street

The horror underlying America’s housing market