4 minute read

How does one summarize a museum’s collection and history into a single exhibition?

The Farnsworth at 75: New Voices from Maine in American Art (on view through December) is a celebration of the museum’s collection, its history, and its community, as well as its role and Maine’s role in the history of American art. To encapsulate the magnitude of this legacy, as well as so many artists’ contributions to the canon of art history, is impossible. Instead, the Farnsworth’s galleries offer intimate moments of discovery, wonder, and dialogue across media and time, and an acknowledgement that the exhibition is a mere microcosm of the collection.

Advertisement

Comprising more than 15,000 objects, the collection is the museum’s greatest strength and is nationally recognized as one of the finest holdings of American art. Since the inception of its collection, the Farnsworth has acquired works by young, emerging artists, such as 27-old Andrew Wyeth in 1944 and the contemporary artists whose works represent the more recent acquisitions in this exhibition. Each artist has a singular perspective, and each object has a unique story, whose interpretations may be expanded with 21st-century discourses and perspectives.

Today, these works neighbor one another in new configurations, arranged in thematic galleries that present the artists’ ideas and renderings on the landscape, the sea, industry, abstraction, and so much more. We invite you to look, ponder, question, and challenge ideas, concepts, and artistic styles. How do the art, artists, and ideas on display encourage us to see things anew? How do the works speak to each other in exciting and unexpected ways? What dialogues about the many chapters of American art history and Maine’s role in writing them interest you?

ANN CRAVEN (born 1967)

Portrait of a Robin II (Looking, After Picabia) 2022, 2022

Oil on linen

84 x 60 inches

Gift of the artist on the occasion of the Museum’s 75th Anniversary, 2022.45

© Ann Craven

Ann Craven paints lushly colored portraits of the moon, birds, and flowers, which she revisits in serial fashion. Like robins in nature, each of her iterations of the subject is the same but different. For her, painting multiple versions of an image is a way to conflate the momentary with the constant—a symbol of time and memory. Each work is inscribed with the date, time, and place of its making, as in a diary. Her series of birds was inspired by illustrations found in her grandmother’s ornithology books, which she often combines with images drawn from art history. In this work, the background flowers reference the work of the early-20th-century French avant-garde painter Francis Picabia.

ALVAN FISHER (1792–1863)

Camden Hills and Harbor, c. 1852

Oil on canvas

27 1/8 x 35 7/8 inches

Gift of Philip and Frances Hofer, 1966.1478

Alvan Fisher was among the earliest professional landscape painters who visited Maine in search of subject matter. He painted a number of romantic views of harbors, and emphasized the rugged beauty of Maine that appeared to dwarf human presence. In his view of Camden Harbor he emphasized the curves of cliffs, mountains, and boat sails in order to frame the theatrical scene struck by shafts of light and viewed by awestruck figures.

LAUREN FENSTERSTOCK (born 1975)

Scrying 7, 2017

Shells, mouth-blown glass, obsidian, rubber 41 x 33 x 12 inches

Museum Purchase, Lynne Drexler Acquisition Fund, 2022.9 © Lauren Fensterstock

Lauren Fensterstock’s work explores the history of nature. She has been obsessed with the tool, the Claude glass, or black mirror. It was used by artists to reflect the landscape in miniature and, in doing so, to merge details and reduce the strength of color so that the artist is presented with a broad picture of the scene and a certain tonal unity.

In Scrying 7, the black mirror becomes a domestic tool–not to view an exterior landscape but to explore an interior one. Encircled by the forms of the shell grotto, the absence and presence of the glass replaces the penetrating and potentially mystical space of the cave.

JEREMY FREY (born 1978)

Urchin Basket , 2008

Split and dyed brown ash

Museum Purchase, Lynne Drexler Acquisition Fund, 2022.19

© Jeremy Frey

Native American peoples have inhabited the land we now call Maine for over 13,000 years. Its waters— from its ocean and rivers to ponds and lakes—provided important food sources for the Wabanaki, or People of the Dawnland. The Passamaquoddy and other coastal people collected sea urchins, among other crustaceans, as part of their diet.

Jeremy Frey’s basket is inspired by the small round animal with a hard shell. To construct it, he weaves materials over a hand-carved mold—a meticulous and time-consuming process. The use of the color purple, along with the smooth woven surface, symbolizes the lifecycle of the urchin itself, suggesting that this basket is a dedication to the deceased creature when it was found on the beach.

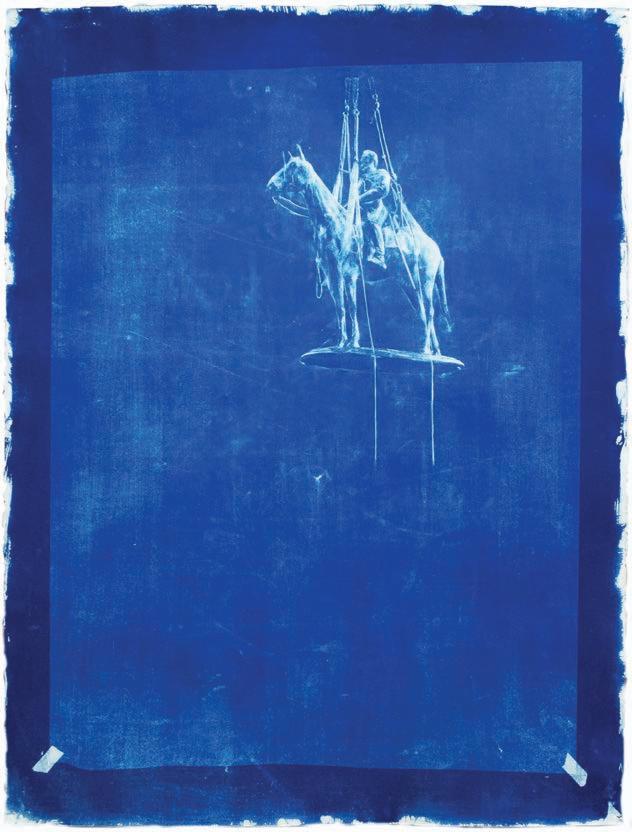

AARON T STEPHAN (born 1974)

Untitled, Stonewall, 2020 Cyanotype on paper

56 x 42 inches

Museum Purchase, Lynne Drexler Acquisition Fund, 2022.32

© Aaron Stephan

Aaron Stephan’s large-scale cyanotypes address questions of what it traditionally means to make public art and monuments. A cyanotype is a historic photographic process that produces cyan blueprints through exposure to UV (ultraviolet) light. Stephan began this series at the outset of the 2020 pandemic. Later that year, nearly 200 Confederate monuments across the country were dismantled. Stephan responded with images that reveal “the fragility and falseness” of monuments once intended to convey strength and power.

FITZ HENRY LANE (1804-1865)

Owl’s Head Light, Rockland, Maine, c. 1856

Oil on canvas

20 1/8 x 33 1/8 inches

Bequest of Mrs. Elizabeth B. Noyce, 1997.3.31

Penobscot Bay was a favorite subject for Fitz Henry Lane, who sailed on several occasions along the Gloucester, Massachusetts coast as far as Mount Desert Island in Maine seeking inspiration for his work. This scene of storm-tossed boats and heavy seas in Rockland Harbor was one of several paintings devised from sketches he made during an 1855 voyage along the Maine coast.

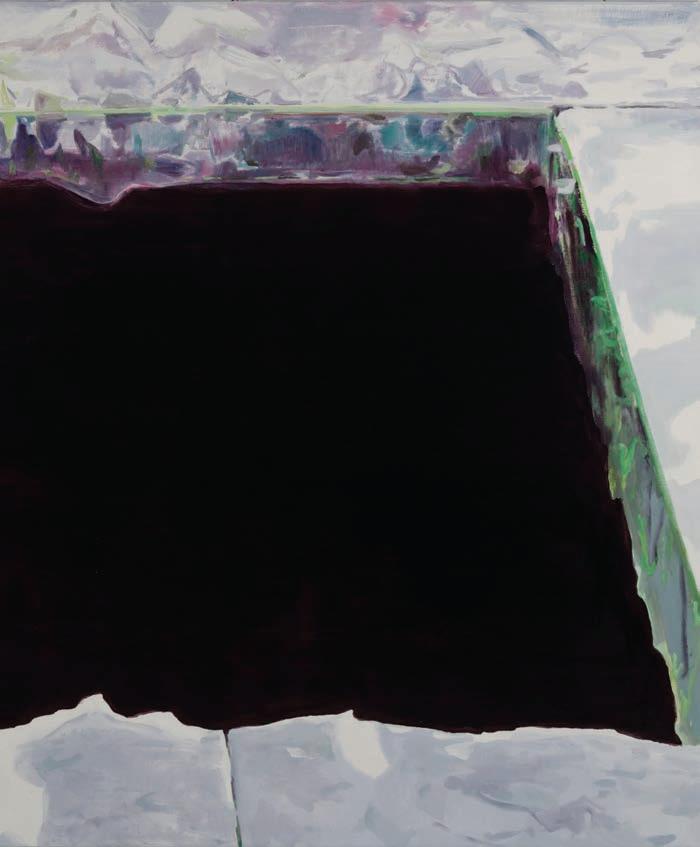

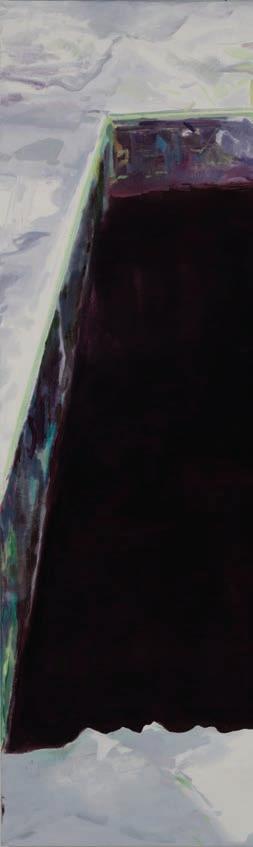

ERIC AHO (born 1966)

Ice Cut (Violet Kennebec), 2022

Oil on linen

80 x 90 inches

Museum Purchase, Lynne Drexler Acquisition Fund, 2022.28

© Eric Aho

This painting explores the history of the global ice industry in the 19th century. Ice from the Kennebec River in Maine was notable for its remarkable color qualities, pureness, and flavor. The excised blocks were a special blue and set the industry standard for quality. In the winter of 1891, there were no fewer than 40 ice harvesting operations at work on the Kennebec, each with an attendant ice house on the riverbank. Holes carved into the ice, such as the one in this painting, at about this same scale, marked the first step in the harvesting process.

This painting’s central shape is a deep inky violet because its particular hue was taken from direct observation of water passing beneath the ice in winter.