44 minute read

Remains of A World

REMAINS OF A WORLD

Advertisement

Searching for the Remains of Silence

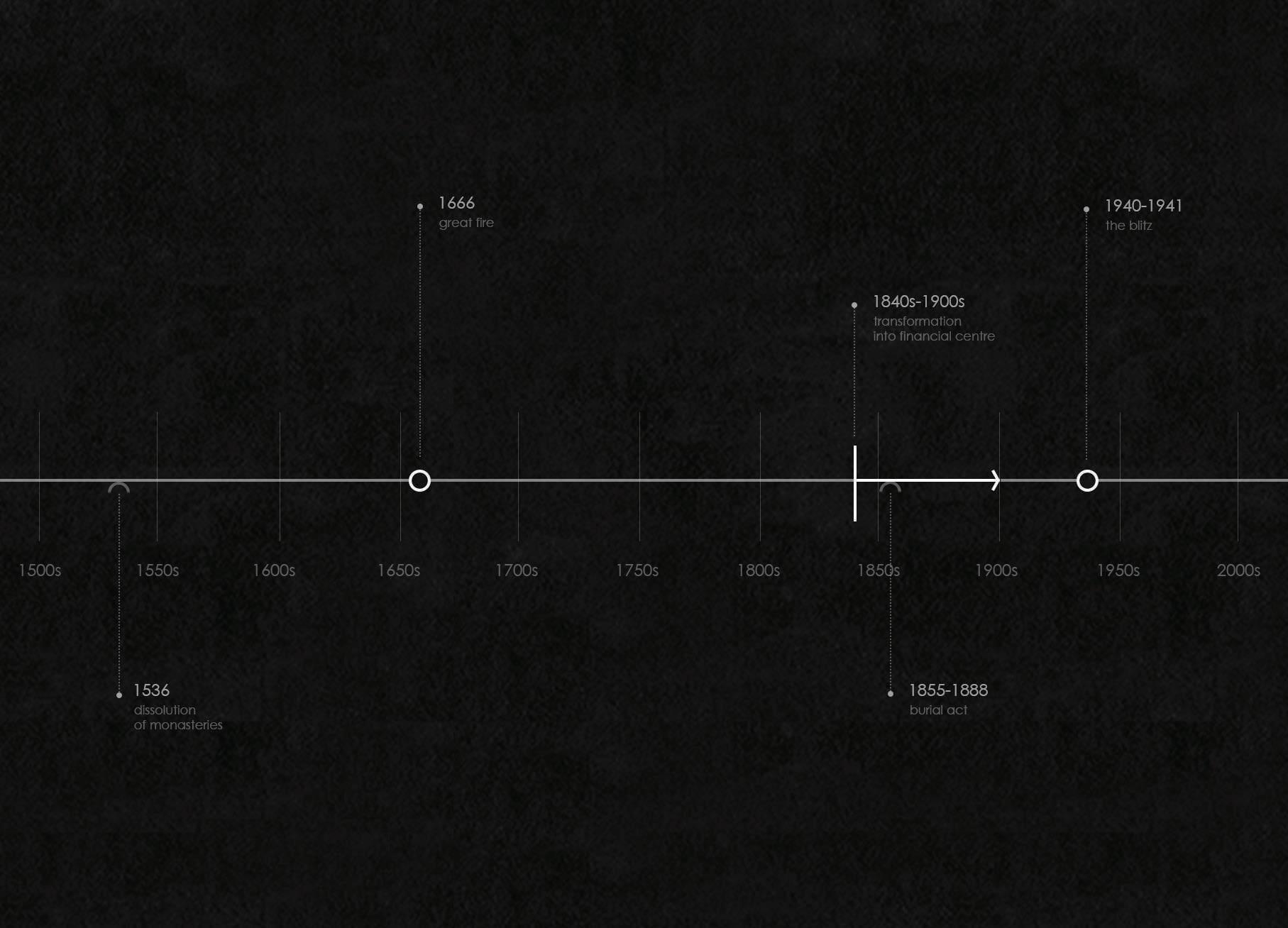

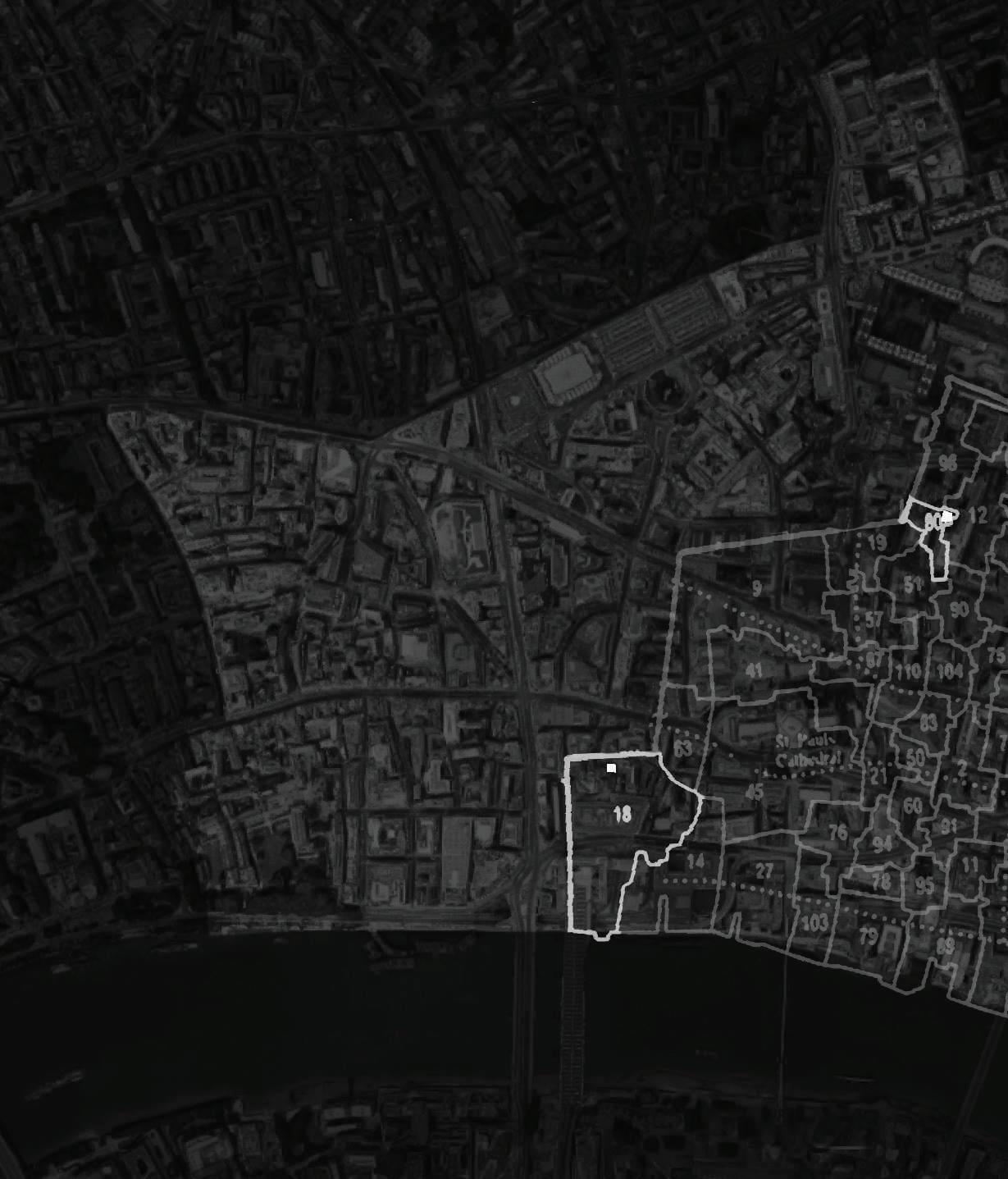

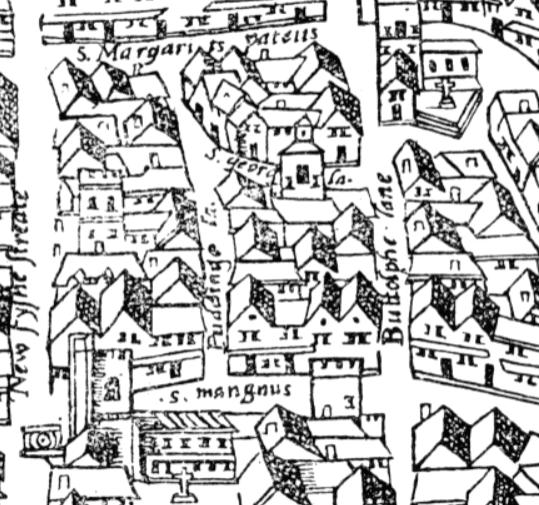

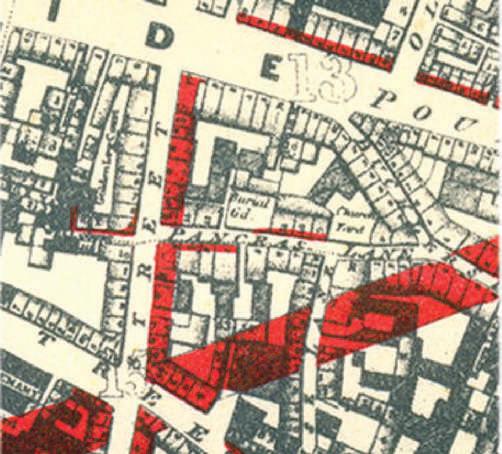

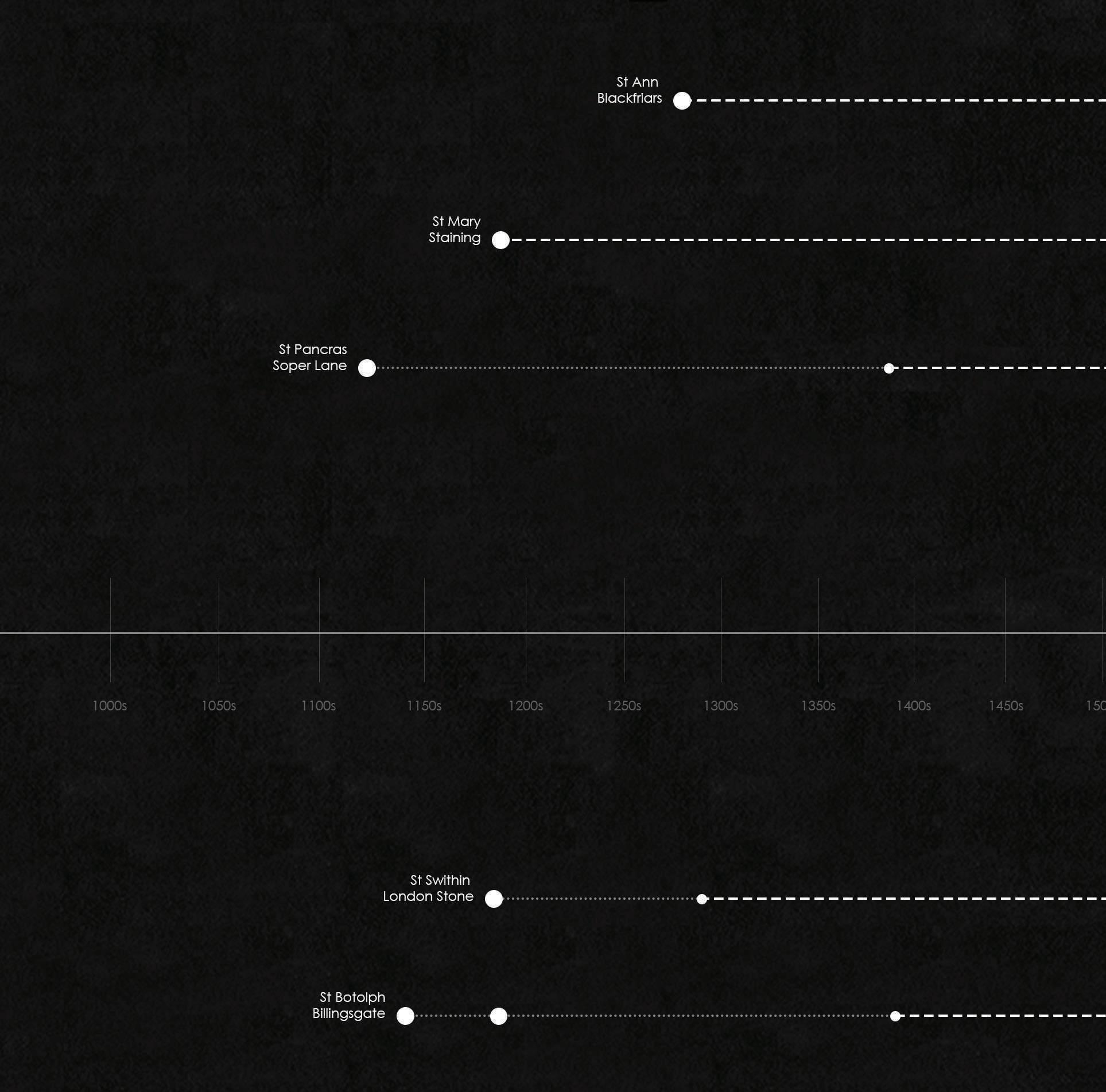

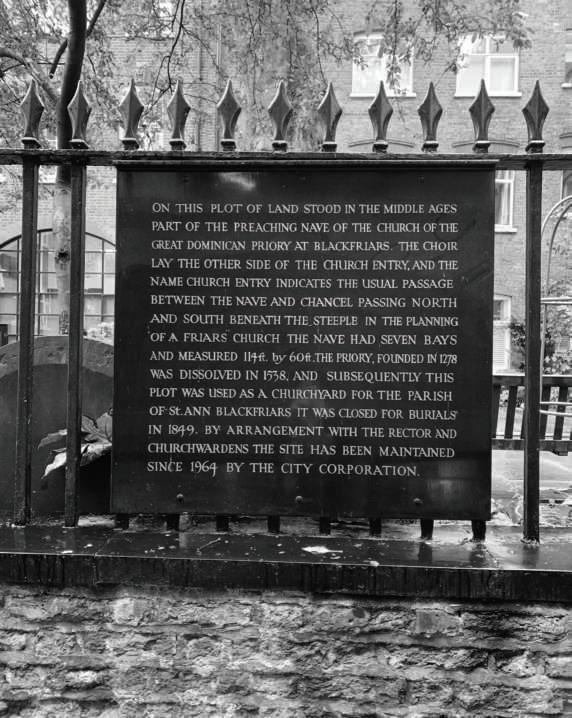

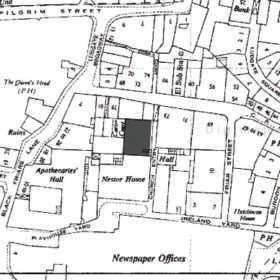

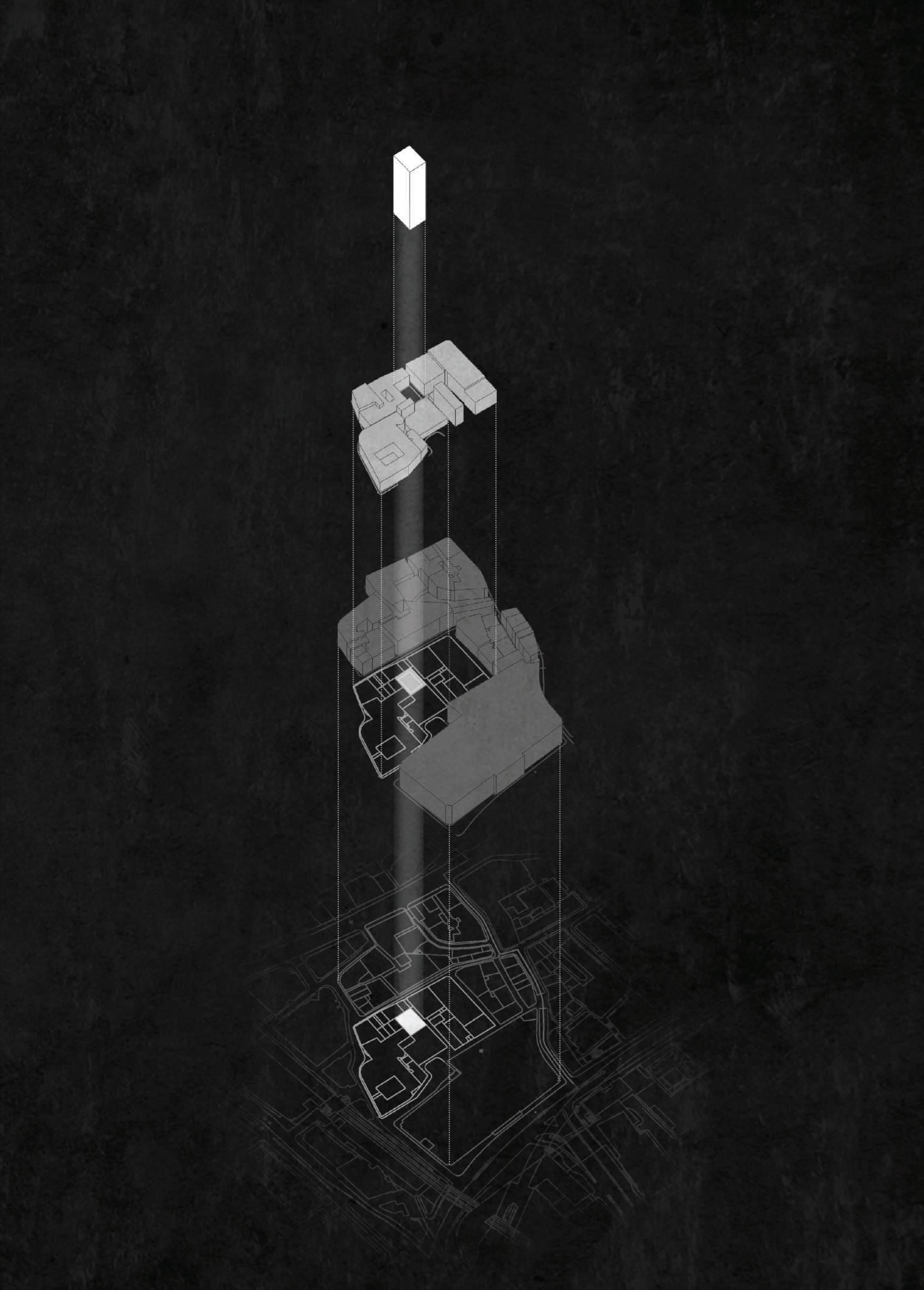

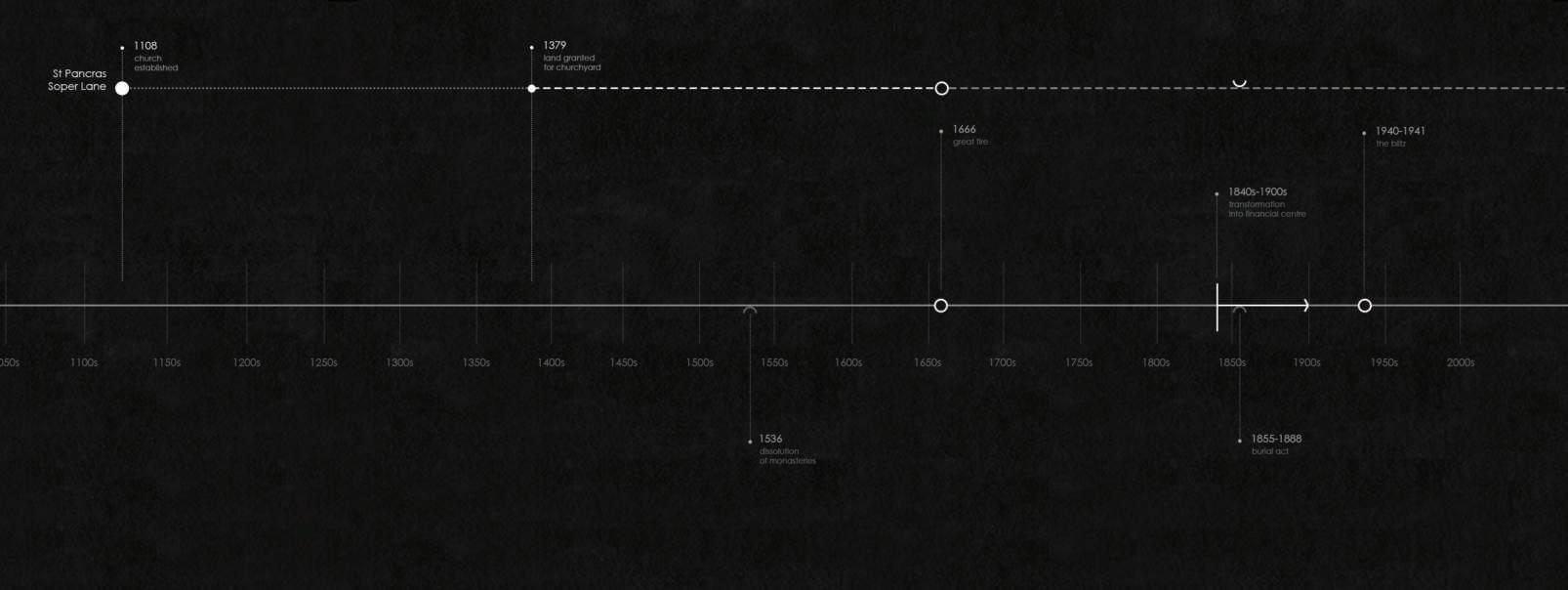

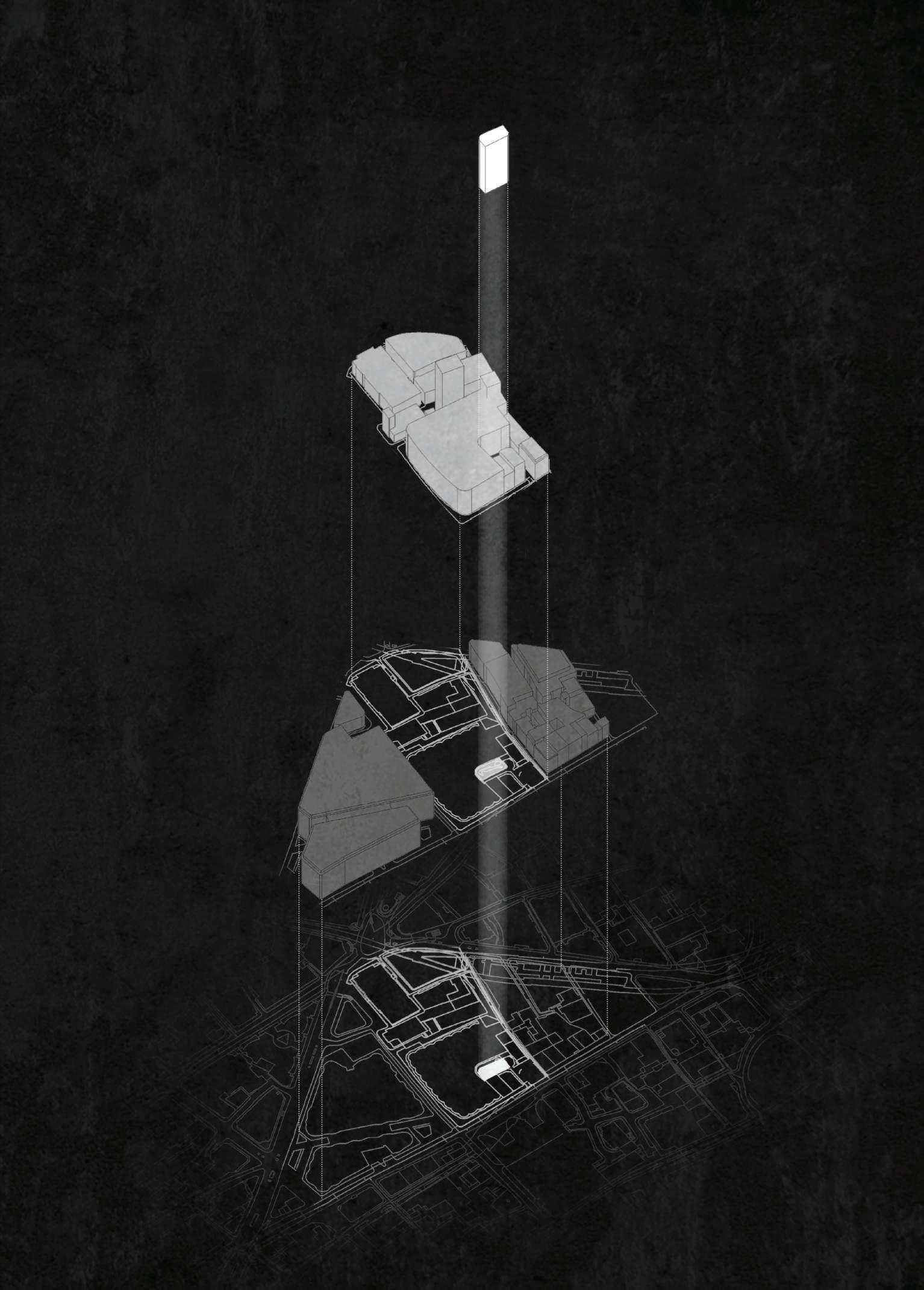

The thesis explores the concepts of silence, interiority and contemplation in urban scale within the context of the City of London, one of the densest and oldest areas in London. It has been an urban palimpsest over the course of history, written and rewritten through the events of major impact such as the Great Fire and the Blitz. (fig.1) However the transformation of the City with the 19th century, constituted a contextual infrastructure for the reconstruction years following the Blitz and therefore, played a substantial role in the development of the area into the corporate face of London as we know today.

The City was overwhelmingly residential until this time with its own traditions from politics to even hours of rising and dining. 1 But starting with the 1840s, it was subject to serious depopulation and modernisation, transforming into a financial and commercial enclave less and less desirable to live in. Indeed, despite the increasing population of London in general, the demographics of the area show a rapid decline during this period; from 107,000 in 1861 to 51,000 in 1881, and finally to 27,000 in 1901. 2 Apart from the tremendous rise of the land value and rents, this was partially due to the improvements in transportation, thanks to technological developments of the industrial revolution. Introduction of new railways and underground transportation made it easier to live outside the City whilst commuting in for work. The convulsions of the 1860s with several railway companies seeking a terminus in the City 3 , added more and more to the growing hustle of the area, leaving it amidst a web of loud steam-engines. Nonetheless, such improvements entailed alteration of the street layout, especially through street enlargements that little by little engulfed in small lanes and building blocks. This was also necessary to accommodate the increasing car traffic, along with the underground infrastructure. Demolition to a great extent followed these changes; many of the sites were combined to build larger commercial buildings. However, “The most conspicuous casualties were the parish churches.” as Bradley and Pevsner explain. 4 The redundant churches and churchyards were sold for financial purposes, a routine started with 1860s and continued until around 1905.* And, although the towers were occasionally kept and the burial grounds usually preserved, they were devoured by the new urban fabric, especially after the post-war reconstruction of the area with increasing building heights and the dominance of skyscrapers. 1 Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, London I: The City of London, (London: Penguin Books, 1945), pp. 87. 2 Bradley and Pevsner, pp. 101. 3 Bradley and Pevsner, pp. 102. 4 Bradley and Pevsner, pp. 101. * The sites were sold by the Church to finance the extensions in the suburbs. The ones in the financial district were especially vulnerable. (Bradley and Pevsner, pp. 102-3.) There were voices raised against this situation as also seen in British Periodicals with the following remark; ‘If the people of London knew what they were losing, the work of destruction would not go on so smoothly’. (British Architect, The Preservation of Old London Churches, British Periodicals, (1887), pp. 153.)

Yet, the fragments of churches and churchyards which survived this transformation and the Blitz, impose an interesting relationship with the area’s existing composition. Especially the burial grounds, which today make up most of the available open spaces within the dense urban fabric of the City.

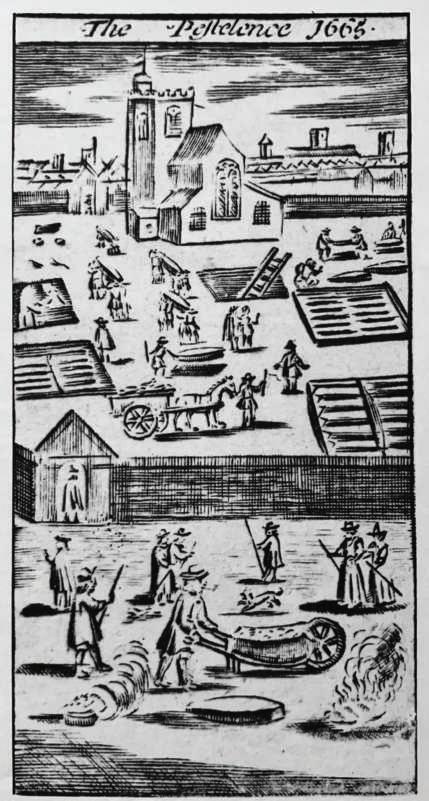

fig6. St Giles Cripplegate during the Great Plague, one of the parishes suffered the most with 4838 deaths.

fig7. Only tombstone left at St Augustine Papey laid on the pavement of the site as a memorial.

fig8. St Bartholomew the Great in the 19th century.

The City Churchyards

“Such strange churchyards hide in the City of London.” Charles Dickens

Today, long after Dickens and much more pleasantly than his time, the unique assemblage of the burial grounds with modern structures of the City continues to surprise. Though pushed, squeezed, sliced or moulded in between office blocks, these shapeless pockets seem to remain immune to the changes time brought to their surroundings, and offer a moment of stillness, like a rare oasis, in the midst of the metropolitan.

Their fragmented presence is very much intertwined with the course of events that shaped the City’s history. Most of them have existed even before the Reformation, some got their churches destroyed and never rebuilt in the Great Fire and some were altered due to infrastructure improvements of the Victorian Era. Finally, in the 1850s, almost all of them got closed for burials with the Burial Act, as they were overcrowded and posed significant health risks. Then on, they were mostly cleared of burials and their contents reburied elsewhere. 4 Nonetheless, the legislation put these sites under protection 5 from the following changes that took place in the area, especially after the War. During the period of post-war construction, they became designated reference points to rebuild the city around, mainly to determine the streets, along with the city churches and their remains. 6 Though, the preservation of the damaged churchyards altogether, was subject to serious debate at the time, as from the clearings rose the opportunity to rebuild the City. Amidst this aggressive property speculation, H. Casson, one of the strong supporters of preservation of these sites as open spaces, pointed out that ‘the City is sadly deficient in such open spaces, which can give glimpses of green against the livid grey of pavements and buildings, affording places of relaxation and retreat’. 7 Eventually, the remaining churchyards were turned into public gardens, often enclosed by layers of huge corporate buildings. 4 City of London Churchyards Statement of Significance, Local Development Scheme: Historic Environment Strategy, (2017), pp. 10. 5 Brian Plummer and Shewan Don, City Gardens : An Open Spaces Survey in the City of London, (London: Belhaven, 1992.) 6 William Holford and Charled Holdon, The City of London: a record of destruction and survival; the proposals for reconstruction as incorporated in the final report of the planning consultants, C.H.Holden and W.G.Holford, presented, in 1947, to the Court of Common Council, (London: Architectural Press, 1951), pp. 231-264. 7 Andrea Pane, ‘Bombed churches as war memorials’ Conservation of World War II Ruins in England: Fate of London City Churches. pp. 10.

Voids Filled with Silence

An Interpretation of the Preserved Void within a Highly Profitable World

Besides historical and urban significance, their existence presents an interesting counterpart to the highly material realm of corporate capital. As mentioned earlier, the development of the City since the 1800s has been very much under the influence of financial institutions, and the pragmatic approach to the existing urban layout this entailed. Business associations and transactions required a close proximity to the Bank of England and the Royal Stock Exchange in order to facilitate the spread of information, which primarily heated up the demolition process at the central periphery in the 19th century. Similarly, the remains of the medieval street scheme with labyrinthine web of narrow passages and alleys became an integral part of the informal patterns of exchange, 8 and therefore secured their value in the profitable world of the market.

Although this benefited the preservation of the smaller streets as a way of reinstating the market during the post-war planning, which was highlighted in Holford and Holden’s 1947 plan, 9 it had further impact on the skyline of the area. The Building Act which had previously restricted the height now placed strict limits on the area of a structure due to the high demand of office buildings.* Despite the fact that this whole profit-based view of the urban structure receded with the introduction of automation technologies and changes in the economic parameters, its impact on the composition of the area remained.

Yet, what can preserved churchyards signify or symbolise in this context?

First of all, it is necessary to understand further implications of this foregoing approach on the City. Within this materialistic perception, the City is rendered as an embodiment of profit, size and power, deprived of deeper meaningful implications which communicate other aspects of human condition. As Philip Sheldrake suggests, it becomes a giant “commodity parcelled into multiple activities and ways of organising time”, 10 thus implying an image, perhaps an imago mundi, which is restricted to the parameters of material existence. This image is reflected in the architectural realm through volumetric grandeur that is ensured by scale and height, and measured through strong visibility.

In the midst of this volumetric power structure, the ‘emptiness’ comprised within the churchyards offers a release. It poses rather an invisible form of value which is determined by the immediate de-materialisation and thus, opposes the otherwise dominant attitude. The feeling inherent in their existence as ‘voids frozen in time’, punctures not only the urban mass of the area, but also the immense speed and hustle embedded in the City. Indeed, this situation correlates to what Sheldrake describes as “a need for spaces that encourage and deepen the attentiveness, a contemplative awareness” through the construction (or, as in this case, preservation) of “spaces for ‘thinking time’, silence and solitude”. 11 Thus, these open spaces constitute a fragmented link of contemplative pockets, by maintaining their historic reference and meaning.

8 Amy Thomas, ‘Money Walks: The Economic Role of the Street in the City of London 1947- 1993’, Opticon1826, (16): 20, pp. 1-15. 9 Thomas, pp. 4. 10 Philip Sheldrake, ‘Placing the Sacred: Transcendence and the City’. Literature and Theology, 21(2007), pp. 245. 11 Sheldrake, pp. 254-255.

Overall, what seems to be a peculiar act of ‘void’ preservation, becomes an opportunity to offer intangible moments of stillness and contemplation in an area frequently defined by visibility and material existence; starting an organic yet paradoxical conversation between the invisible and the material in the City.

Through the influence of the historic and theoretical composition aforementioned, the project embarks upon an urban research within this rich dialogue, focusing particularly on the remaining churchyards left without a church building. What started as a quest to find intervals of silence amidst the City, is taken a step further at this point to determine whether these remaining silent pockets of the City show any architectural similarities with the preceding contemplative spaces that are studied. Thus, the methodology of this research is very much determined by the preceding discussion of silence, contemplation and interiority.* * See Listening to Silence Section

5 of the remaining churchyards are located and analysed as sample contemplative sites in relation to their surroundings; St Mary Staining, St Pancras Soper Lane, St Ann Blackfriars, St Swithin London Stone and St Botolph Billingsgate (One Tree Park). They have all become hidden ‘urban rooms’ which are reinterpreted as manifestations of the ‘silent void’, sunk deep beneath a plateau of office blocks.

Since the 17th century, they remain as orphaned burial grounds without a relevant church building in the vicinity; no tower, no particular architectural ruin or remain to mark their location. Therefore, their presence is more of a silent one, as they are devoid of physical/ visible trace and got further alienated from their surroundings in the course of time. They remain undisturbed and hidden behind layers of huge office blocks, enclosed within an organic and urban version of spatial layering.

Yet, unlike other contemplative sites in the area, particularly other churchyards such as St Mary Aldermanbury or Christchurch Greyfriars, their relative scale amidst high-rise buildings accentuates a deep sense of interiority. As they shrink and become small ‘contained’ voids, an interesting sense of entering an interior/room unfolds upon one’s encounter with the sites. This is accompanied by a feeling of solitude, though they are open public spaces, and perhaps further encouraged by the momentary removal from distractions of the surrounding city hustle.

SITES

St Ann Blackfriars

Location. Church Entry, EC4V 5EX, London, UK

Related Parish. 18 | St. Ann Blackfriars

Listed Structure. St. Ann’s Vestry Hall

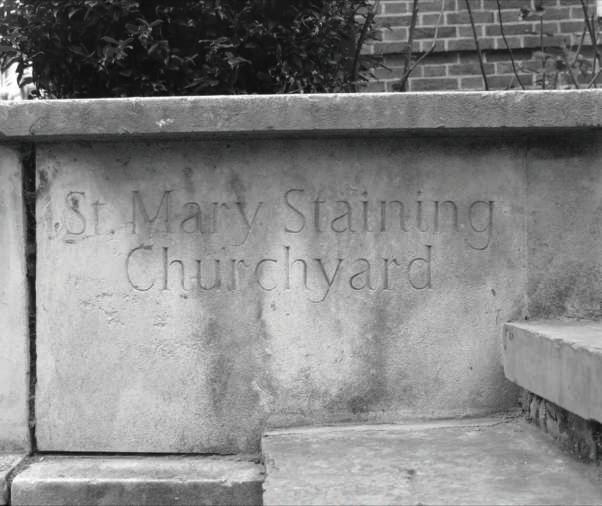

St Mary Staining

Location. Oat Lane/St Albans Court, EC2V 7EE, London, UK

Related Parish. 80 | St. Mary Staining

Listed Structure. None

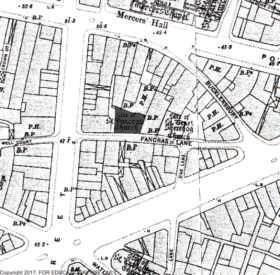

St Pancras Soper Lane

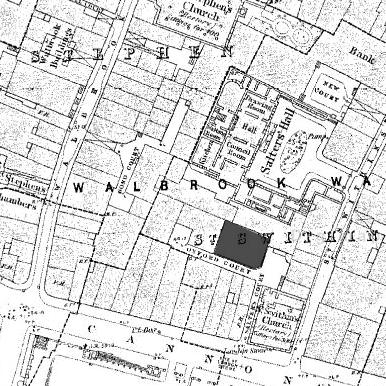

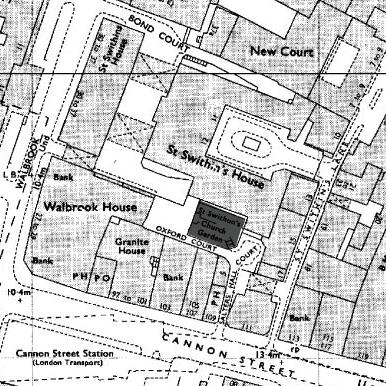

St Swithin London Stone

Location. Pancras Lane, EC2R 8JR, London, UK

Related Parish. 99 | St. Pancras Soper Lane

Listed Structure. The Site is a Scheduled Ancient Monument

Location. Salter’s Hall Court, Oxford Court, Cannon Street, EC4N 8AL, London, UK

Related Parish. 108 | St. Swithin London Stone

Listed Structure. London Stone (111 Cannon Street)

St Botolph Billingsgate (One Tree Park)

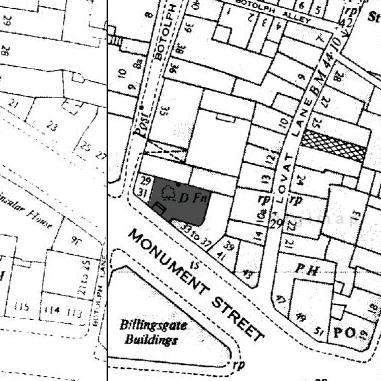

Location. Botolph Lane, Monument Street, EC3R 8BT, London, UK

Related Parish. 31 | St. Botolph Billingsgate

Listed Structure. None

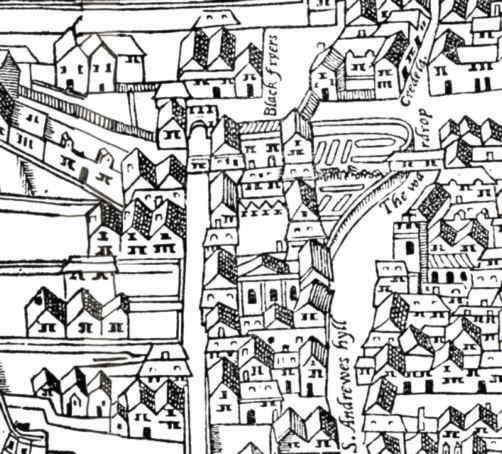

St Ann Blackfriars *

*The original priory church was demolished in 1550 after becoming a parish church in 1544. A new church building was constructed in 1597, approximately 36 years after Agas map was drawn. Therefore the exact location of the site on the map is rather uncertain. This section here shows a very likely location estimated from a comparison of the streets and surroundings in relation to other maps.

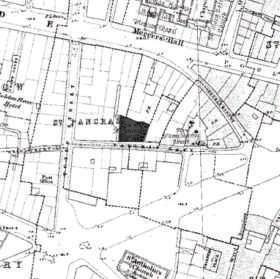

St Mary Staining

St Pancras Soper Lane St Swithin London Stone St Botolph Billingsgate * (One Tree Park)

*For the burial ground of St Botolph Billingsgate was separate from the church, there are two locations displayed on the section here; an estimated location of the burial ground (in bold) and the church building. The preserved street names Botolph Lane, Pudding Lane and St George Lane suggest the marked location for the graveyard, when the historic maps are compared.

Before the Great Fire

Before the Great Fire, sites preserve their integrity with the presence of related church buildings. The bird’s eye view from the 16th century also provides a general idea about the heights of the surrounding structures.

‘Civitas Londinum’ (known as the Agas Map) drawn by Ralph Agas in 1561.British Library.

St Ann Blackfriars St Mary Staining

St Pancras Soper Lane St Swithin London Stone St Botolph Billingsgate (One Tree Park)

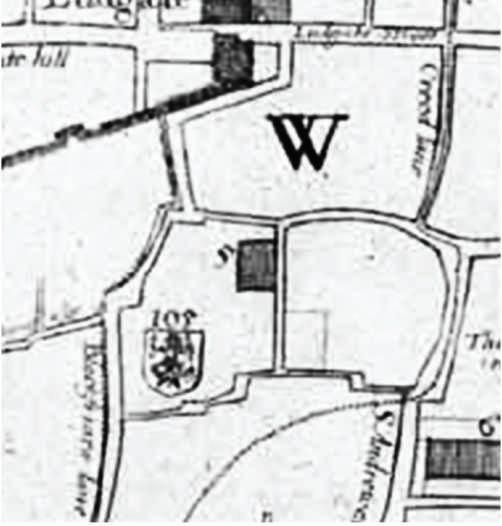

The Great Fire - 1666

1666 marks a turning point for the sites, as the associated church buildings were destroyed during the Great Fire. None were re-built except for St Swithin, which had its building designed by Christopher Wren and constructed in 1667-8. Despite the destruction, sites sustained their significance as burial grounds until the Burial Act. They remained as ‘voids’ whilst the city was rebuilt, becoming pinpoints during this process.

Hollar’s ‘Exact’ Survey of the City of London drawn by Wenceslaus Hollar in1667. The National Archives.

St Ann Blackfriars St Mary Staining

St Pancras Soper Lane St Swithin London Stone St Botolph Billingsgate (One Tree Park)

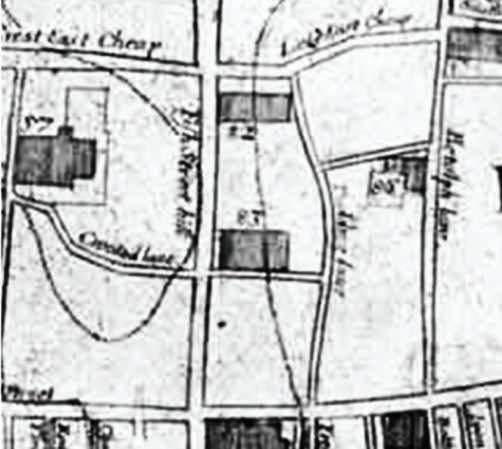

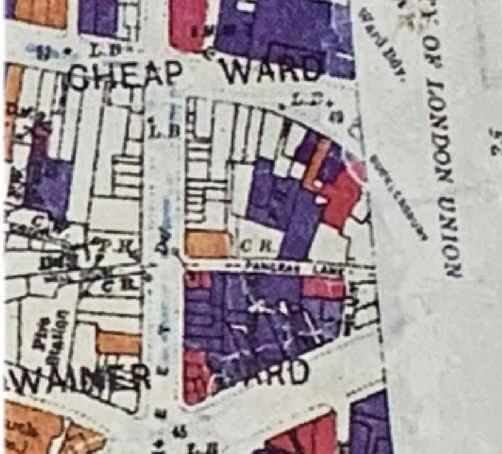

19th Century Alterations

Sections above show the sites in relation to the street improvements made in the City of London during 1851-1902. The expansions are significant as they suggest an increase in street activity and therefore, most probably in the sound levels of the streets. The current conditions of the sites support this assumption as the general sound mapping analysis on the following pages suggest (pp.36-42). The two most affected locations are St Pancras and St Botolph. Apart from the expansion on the Queen St drawing the former closer on the west side, diagonal street expansion on the south create an enclosure of major streets with the Cheapside St on the north. The latter, on the other hand, is directly affected with the expansion of Monument St resulting in loss of a small section from the south of the site.

Baseplate: Wyld’s Plan of the City of London 1842, Adjustments on the map: 1905.

St Ann Blackfriars St Mary Staining

St Pancras Soper Lane St Swithin London Stone St Botolph Billingsgate (One Tree Park)

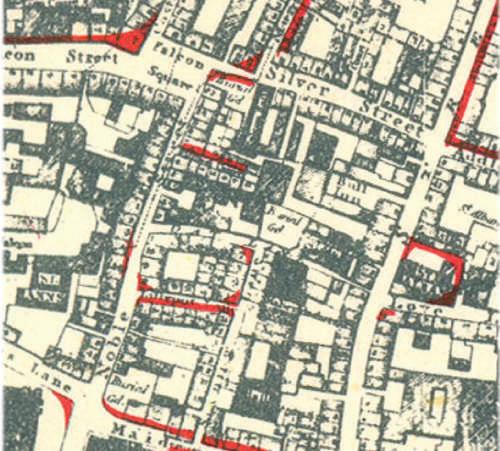

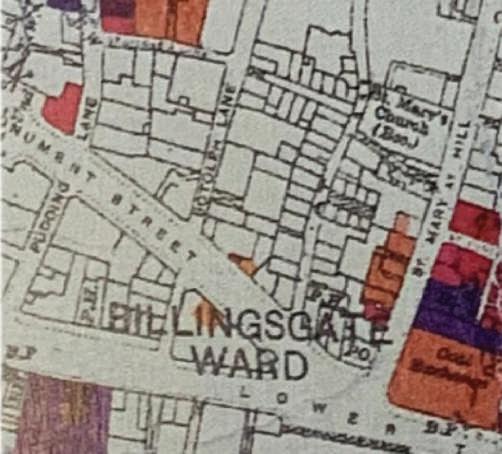

World War II

The bomb damage maps render how the surroundings of the sites were affected during the Blitz. As seen, St Mary Staining, St Pancras and St Swithin are subject to severe damage. This devastation which was followed by a rapid reconstruction period played a substantial part for the increasing height of the immediate boundaries of the mentioned sites.

The London County Council Bomb Damage Maps No. 62-63, 1939-45.London Metropolitan Archives.

total destruction minor damage

repair is doubtfuldamage beyond repair clearance areas repairable at cost

St Ann Blackfriars St Mary Staining

St Pancras Soper Lane St Swithin London Stone St Botolph Billingsgate (One Tree Park)

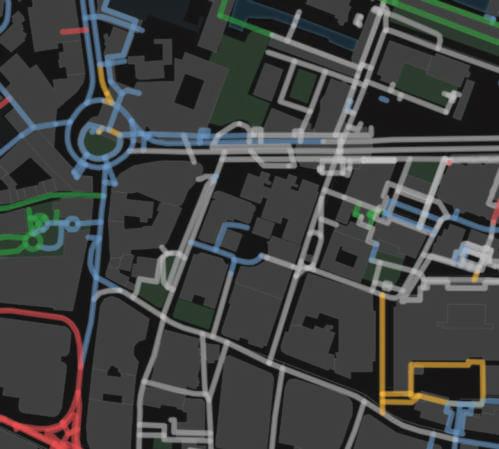

Sound Compositions

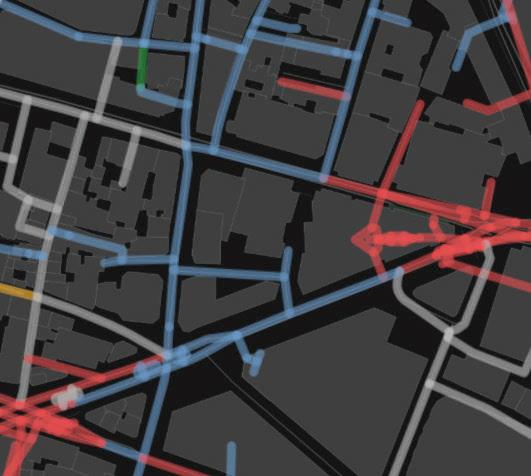

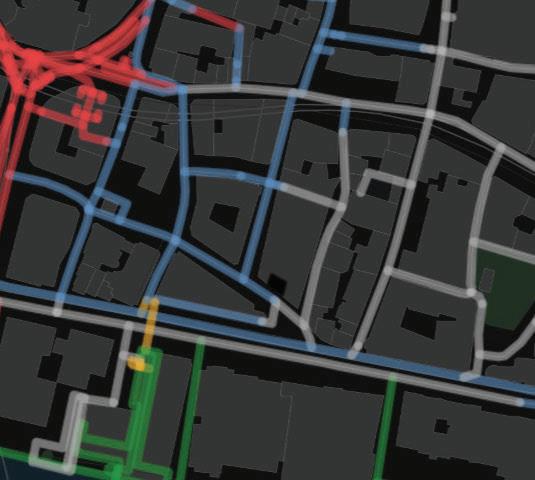

The sections above provide the sound compositions for each site, though not necessarily the noise levels. The dominant sounds in the close parameter of the sites can be observed as human and building originated according to the maps.

‘Urban Sound Dictionary’ by Chatty Maps. http://goodcitylife.org/chattymaps/index.php

transport nature human music building

St Ann Blackfriars St Mary Staining

St Pancras Soper Lane St Swithin London Stone St Botolph Billingsgate (One Tree Park)

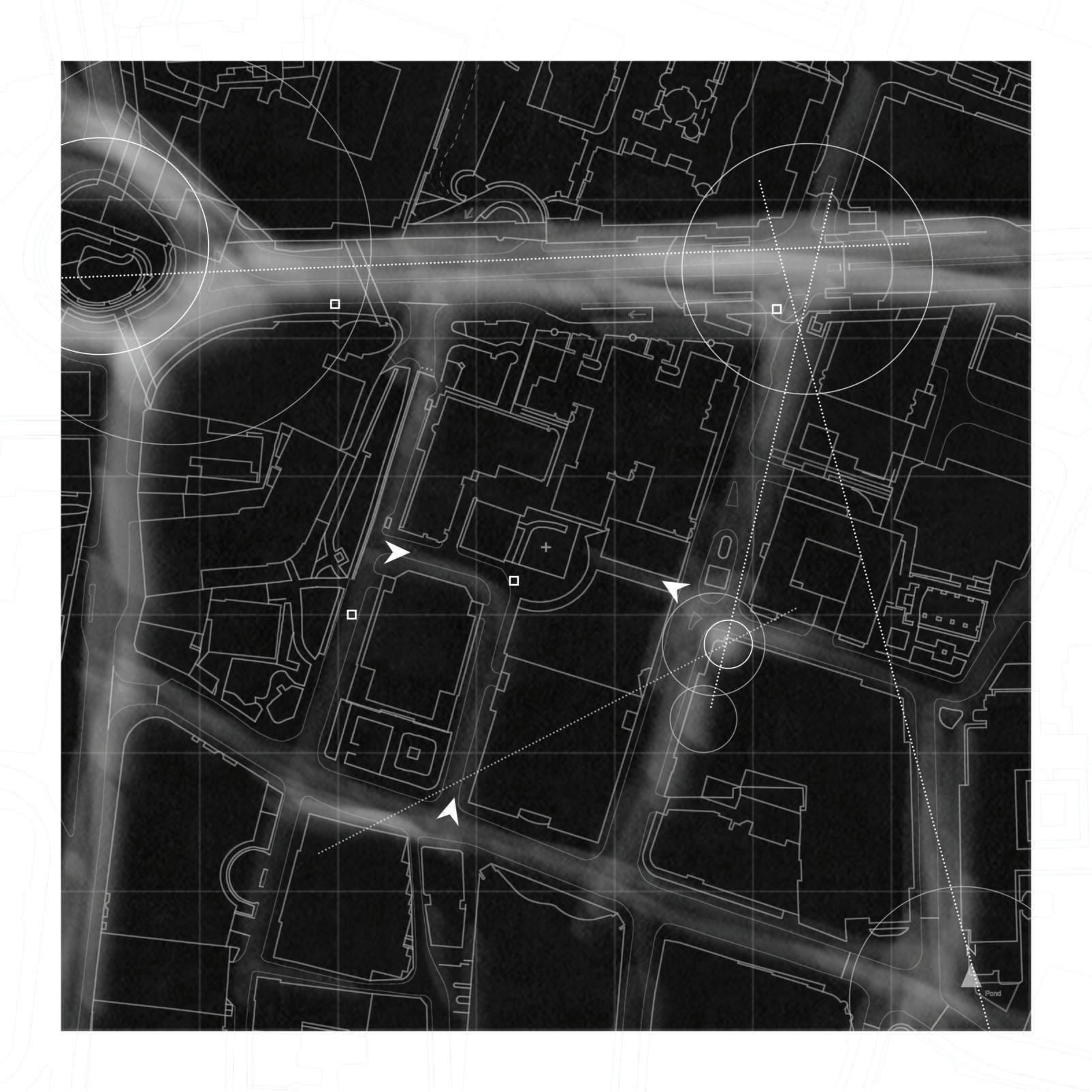

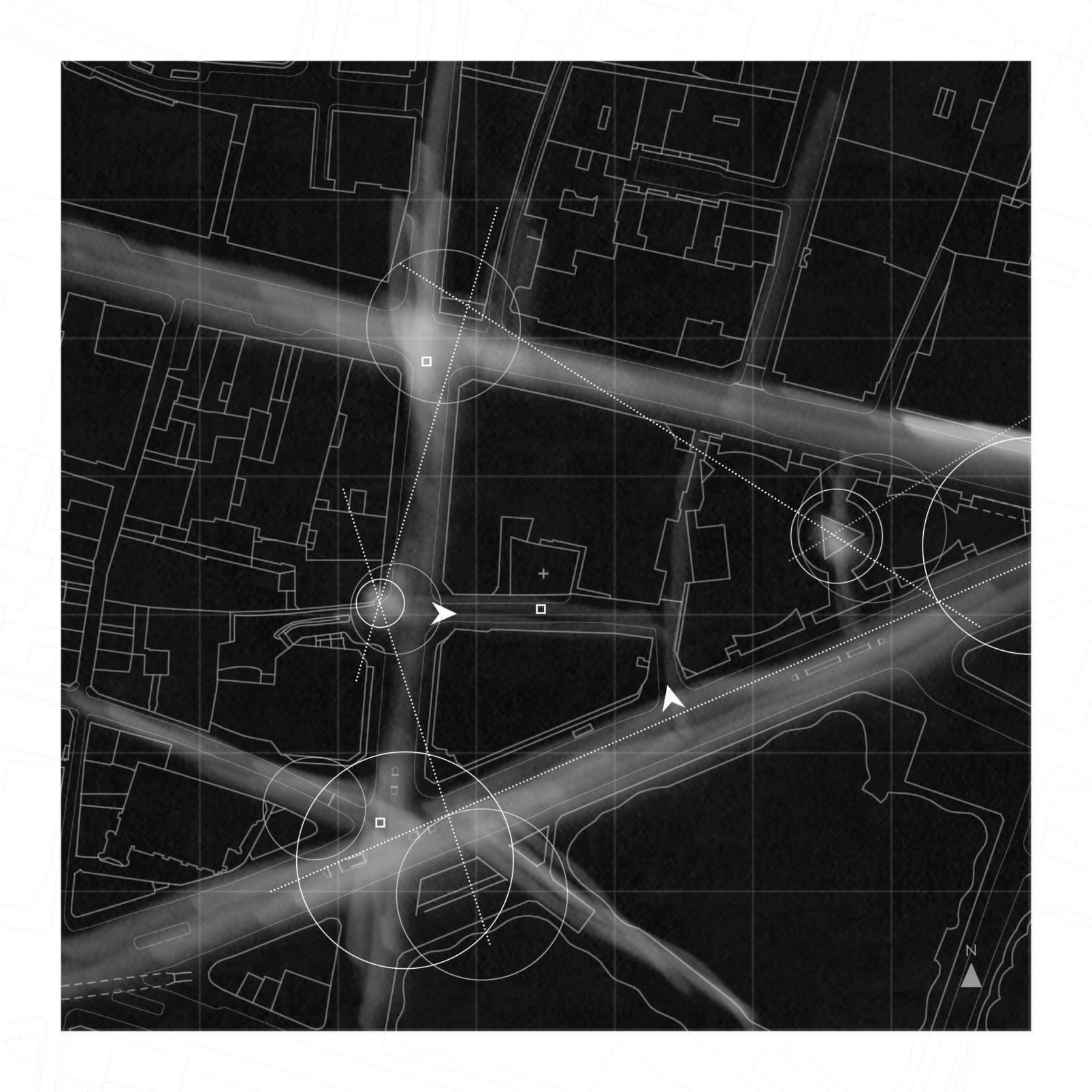

Sound Levels & Site Access

The following pages introduce a general sound study of the sites through systematic visits and are accompanied by sound recordings along the marked points. The intention is to further articulate the experience of accessing the locations in relation to silence and its role in evoking contemplation. In general, the access to the sites underline the comparative perception of silence by a gradual decrease in levels and types of sound. It is possible to experience an auditory layering through this gradation, which intensifies the perception of the sites as contemplative pockets. The sound recordings reveal that the reduction of transportation noise is noteworthy.

Major sound sources in the areas such as pubs, railways, major traffic junctions etc. and their impacts Access points to the sites Sound recording points Site Location

pub

pub

pub

pub

railway

junction

pub

pub

pub

junction

junction

minor point

pub

pub

junction

pub

junction

plaza

junction

plaza

junction

plaza

junction

tube station

pub

junction

pub

pub

pub

attraction

pub

junction

Historic Note on the Soundscapes of the Sites

It is necessary at this stage to note that the contemporary soundscape of the City churchyards perhaps differ to a great extent than what they used to be. First of all, considering the large number of parishes and the proximity of the burial grounds to the churches, they were left amidst the impact of church bells, which were ‘the most obvious soundmarks in the acoustically dense soundscape’ of London. 1

On the other hand, they have been a vivid part of the daily life since the early Middle Ages, which would contribute to the composition of the soundscapes. Along with the relatives of the deceased, they were constantly visited by groups of people for various reasons from providing water if they contained a well; administrative meetings concerning the parish and ward affairs; and to the open-air sermons. 2 These churchyards used to echo with the sounds of daily life. St Mary Staining would be such an example as the name of the street adjacent to the site, Oat Lane, suggests the existence of an oat market right next to the churchyard.

Therefore, it is not possible to presume these sites as silent isolated pieces of lands, nor attribute the potential of a contemplative experience entirely to the gradual reduction of sound. Although it is an important part of the experience in approaching the sites, it is rather meaningful together with the other qualities embedded in their composition.

1 Bruce R. Smith, The Acoustic World of Early Modern England: attending the O-factor, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), pp. 53. 2 City of London Churchyards Statement of Significance, pp. 10.

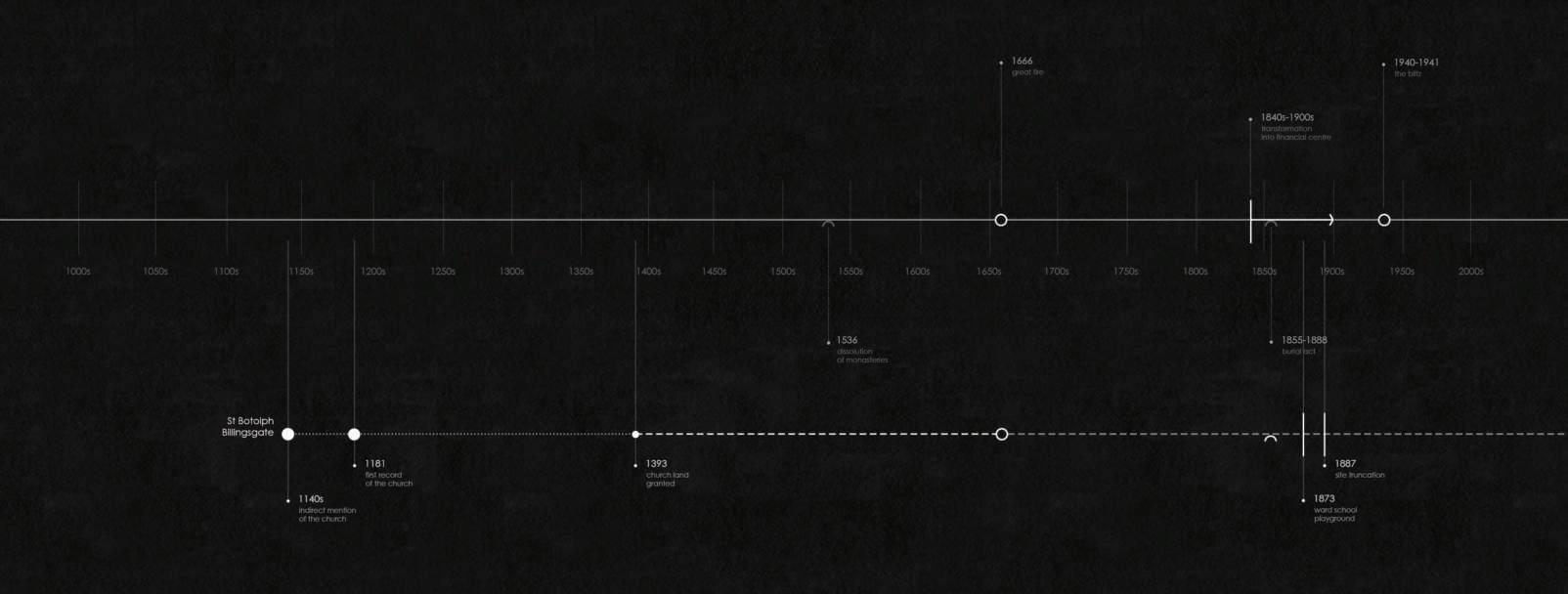

Major drastic events Establishment of the related church and/or the first mention in the records Land granted Constitutional changes

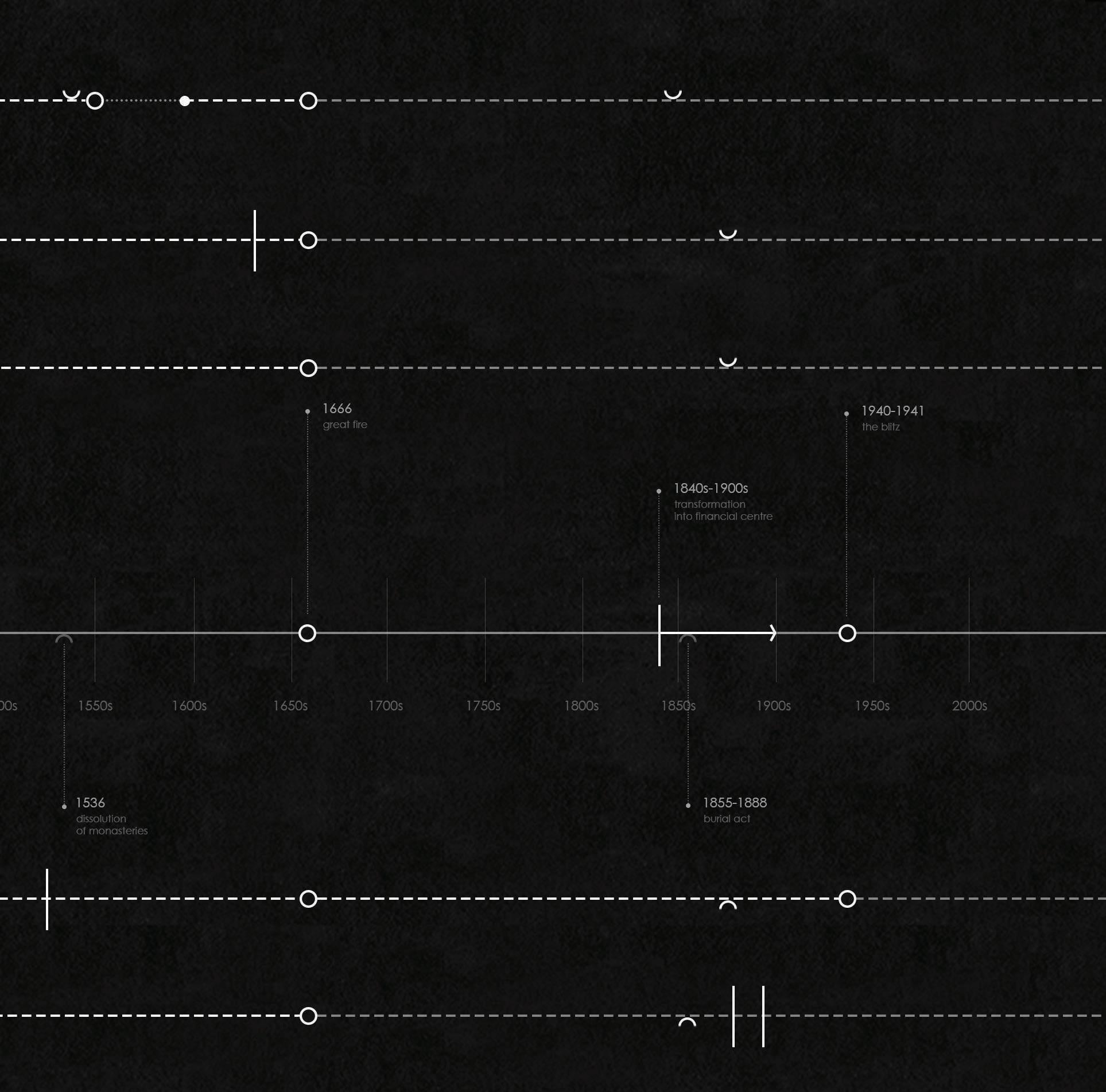

fig16. Historic plaque at the entrance of the site.

fig17. Churchyard entrance gate. fig18. Look towards the north of the site.

fig20. View of the Church Entry, with the site railings on the right.

fig21. Remains of the former churchyard.

fig22. Look towards the north-west corner of the site from the entrance.

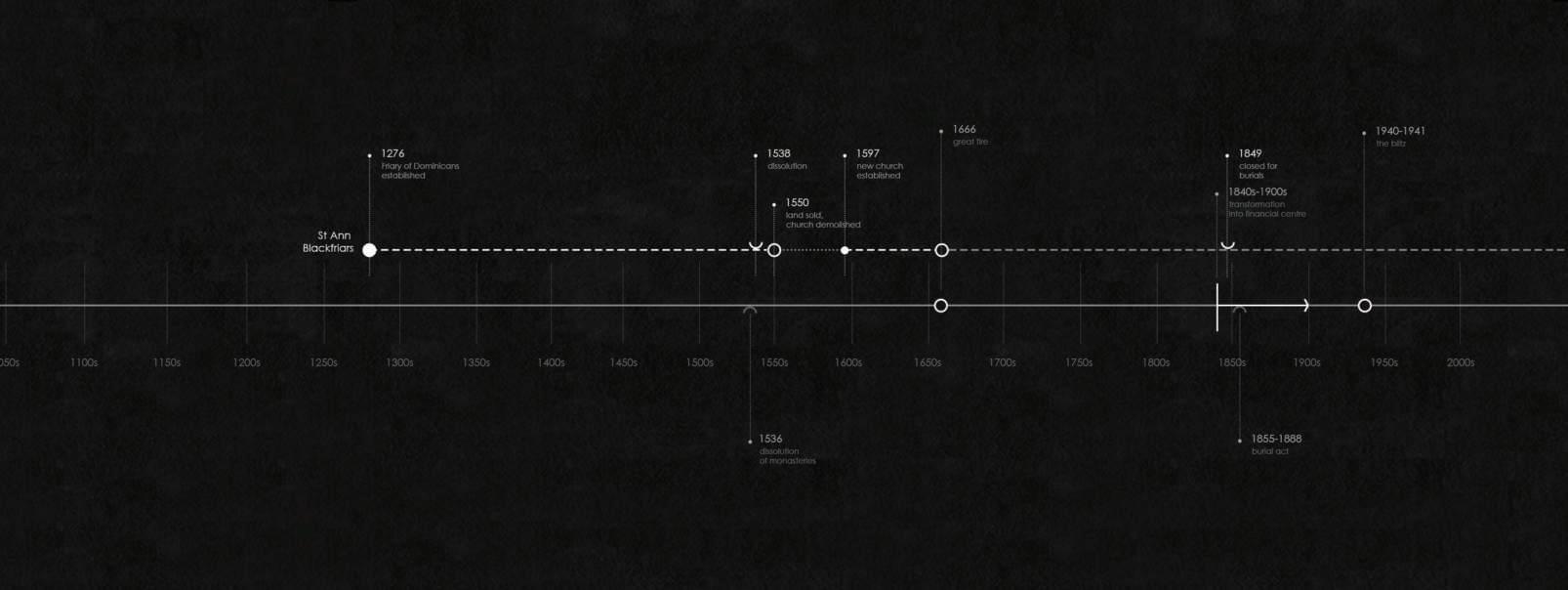

Brief History: St Ann Blackfriars

St Ann Blackfriars church was initially established as a priory in 1276 for Dominican Order. Following the dissolution of the monasteries, it became a parish church in 1544, yet only survived until 1550 when the land was sold and the building was demolished. In 1597, new St Ann Blackfriars church was constructed on the Ireland Yard site. Part of the old Friary church site, entered through the Church Entry, was turned into a burial ground for St Ann. The new church building was lost in the Great Fire, however the burial grounds continued to function until the termination of burial in 1849. Today, the site is enclosed by the brick façades of adjacent buildings, all of which are offices. The elevation of the land itself reduces the perceived height of the surrounding structures to four storeys, although they are five storeys in street level. Still, the size and the isolation of the site sustains the feeling of interiority. Church Entry remains a quiet passage, despite its proximity to Blackfriars Station.

aerial view. 2018 map. 1960 map. 1950 map. 1910

intimus

intimus

interior

interior

inter

inter

fig23. Entrance from St Alban’s Court.

fig24. Look towards south east corner of the site.

fig25. Look towards south east corner of the site, the Pewterer’s Company building on the right.

fig27. Steps leading to the elevated land, defining a threshold.

fig28. Detail from the steps with the engraving. fig29. The ‘interiors’ of the site, surroundings reflecting the landscape back.

Brief History: St Mary Staining

One of the earliest referrals to the church is in 1189 as “Ecclesia de Staningehage”. The name of the church and Staining Lane suggests association with the name of a landowner from Staines. The Oat Lane adjacent to the site was the location of the Oat Market that existed by 16th century. Although the church was repaired in 1630, it burnt down in 1666 and wasn’t restored. However the burial ground remained as an open space. Today, it is surrounded by buildings with a variety of size and material. On the west is the brick wall which provides insights into the three storey building of the Pewterer’s Company with an impressive interior. The rest of the adjacent structures are tall buildings with glass façades, similarly offering indiscreet views of the offices inside. The landscaping of the site is further reflected and duplicated on these, creating a relief from their overwhelming scale. Yet, the blocks of skyscrapers, especially 88 Wood Street located on the north, protect the site from the traffic noise of busy London Wall Street.

aerial view. 2018 map. 1960 map. 1940 map. 1870

intimus

interior

inter

fig30. Look towards Pancras Lane from Queen St with the trees spilling from the site.

fig31. Historic plaque to the Great Fire. fig32. Detail of the ‘interiors’ of the site showing day light conditions.

fig35. Details of the pavement design and the seating.

fig34. The existing trees emphasize the verticality of the site.

fig36. Details of the seating and the landscape.

Brief History: St Pancras Soper Lane

Established in 1108, the church was granted the site in 1379. In 1550 the churchyard existed as a sliver of land, yet following the destruction of the church building in 1666, the site as a whole was turned into a burial ground. It was closed to burials in 19th century and remained as an open space. The excavations on the site in 1963-4 revealed parts of the destroyed church (foundations and tower wall in particular) and a well. The remains are preserved 0.6-0.9m below the ground and the site is designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument in 1979. Today, the site is surrounded by two major streets; Cheapside, which continues as Poultry, and Queen Victoria. The area is again dominated by commercial buildings. The churchyard is engulfed in the back of a six-to-seven-storey office building; facing the glass covered atrium of another one across Pancras Lane. As this glass structure is shorter, the north wall/façade of the site is washed by natural light during day. A small corner of the famous No.1 Poultry is revealed on the east side, right at the turn to Sise Lane.

aerial view. 2018 map. 1960 map. 1895 map. 1870

intimus

interior

inter

fig38. Former churchyard now public garden in 2011, with memorial to Catrin Glyndwr.

fig37. ‘Interiors’ of the site, landscaping in conversation with the adjacent façades. fig39. Engraving showing St Swithin London Stone Church in 1839.

fig41. Bomb-damaged Wren church ruins with London Stone, picture taken in 1962 just before the remains were demolished.

fig43. Engraving showing the south front of the Wren church and Cannon Street in 1831, the churchyard remains hidden from the street.

fig42. Look towards the site from the junction of Cannon Street and Salter’s Hall Court.

fig44. Look inside the garden towards entrance gate.

Brief History: St Swithin London Stone

The churchyard was established in 1286, originally with a church building set back from the street with the churchyard in between. During the construction of a new and larger building in 1420, the site arrangement has changed; the church moved to the junction of St Swithun’s Lane and Canwikstrete, leaving a narrow passage to access the churchyard. After the Great Fire the church was rebuilt by Christopher Wren in 1667-8, however was bombed during World War II. The church was known as St Swithin London Stone, as the famous London Stone was located outside of the south wall. Today, the stone which is known to be a landmark since 1100s and was located at the site in 1742, is relocated on the south front of the building that occupies the bombed church. The churchyard remains as an open space, although it is completely devoured by office complexes. It is completely hidden from the Cannon Street and its hustle, particularly the Cannon Street Station. The ‘interior’ of the site is primarily determined by a retained brick façade, hiding behind a glass structure, and the curved reflective façades of a tall modern office building.

aerial view. 2018 map. 1970 map. 1950 map. 1870

intimus

interior

inter

fig45. Engraving from 1839 showing the Church of St George Botolph Lane, which the parish joined in 16th century.

fig46. Look towards the Church of St George Botolph Lane from Botolph Lane in 1814, revealing the height of the surrounding structures at the time.

fig47. ‘Interiors’ of the site today with the the single tree giving its name to the park.

fig49. Detail of the Gatepiers from inside the site.

fig50. Gatepiers of the churchyard remaining. fig51. Look towards the site from Monument Street, from the east of the site.

Brief History: St Botolph Billingsgate

The church was first recorded in 1181, but an earlier mention suggests its foundation was in 1140s. The site was granted in 1393 and the churchyard became the upper burying ground of the parish which was located at the south of Lower Thames Street. The church building burned down in the Great Fire and was not rebuilt, however the churchyard remained. The parish was later joined to the St. George Botolph Lane, for which the churchyard became an additional burial ground. By 1873 according to the OS maps, the burial ground has become a playground for a War School established in the east of the site. In 1887, site was subject to minor alterations as it was partially truncated during the extension of Monument Street to Lower Thames Street. Currently, the churchyard is squeezed by a residential hall, carving out a small volume with monotonous brick façades; five storey high on one side, eight storey high on the other. Although it is nearby the Monument and a local pub, the site still provides a moment of tranquillity. The commercial building located right across, protects the site from the buzzing traffic of Lower Thames Street.

aerial view. 2018 map. 1950 map. 1890 map. 1870

intimus

interior

inter