Editor

Members of the Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention (I-Health) have made great advances in understanding the basic causes of disease and improving the quality of life. The I-Health research groups in cancer, infectious diseases and human health and dementia represent multidisciplinary collaborations across FAU colleges and with regional clinical partners. The present Journey to Health focuses on research activities from all these research groups and more.

In 2021, the Florida Department of Health awarded the Cancer Center of Excellence (CCE) designation to the Memorial Cancer Institute Florida Atlantic University (MCIFAU) partnership, which includes Scripps Florida and the Gift of Life. The MCIFAU CCE is the fifth CCE in Florida, joining the University of Florida Health Cancer Center, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Mayo Clinic Florida, and the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center. Several MCIFAU CCE initiatives are detailed on pages 10 and 11. Additional cancer-related studies from I-Health members are highlighted on page 5.

The infectious diseases research group has been engaged in numerous SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19-based initiatives. Members of I-Health oversee research examining the psychological impacts of the pandemic (page 5), modeling the impact of the economy on the elimination of COVID-19, evaluating communities at highest risk to COVID-19, and examining genomic information to detect different variants prior to international spread (page 15), predicting outbreaks based on mobility data and age and predicting clinical trial success (page 16), evaluating the spread of COVID-19 and understanding governmental reactions to COVID-19 (page 17).

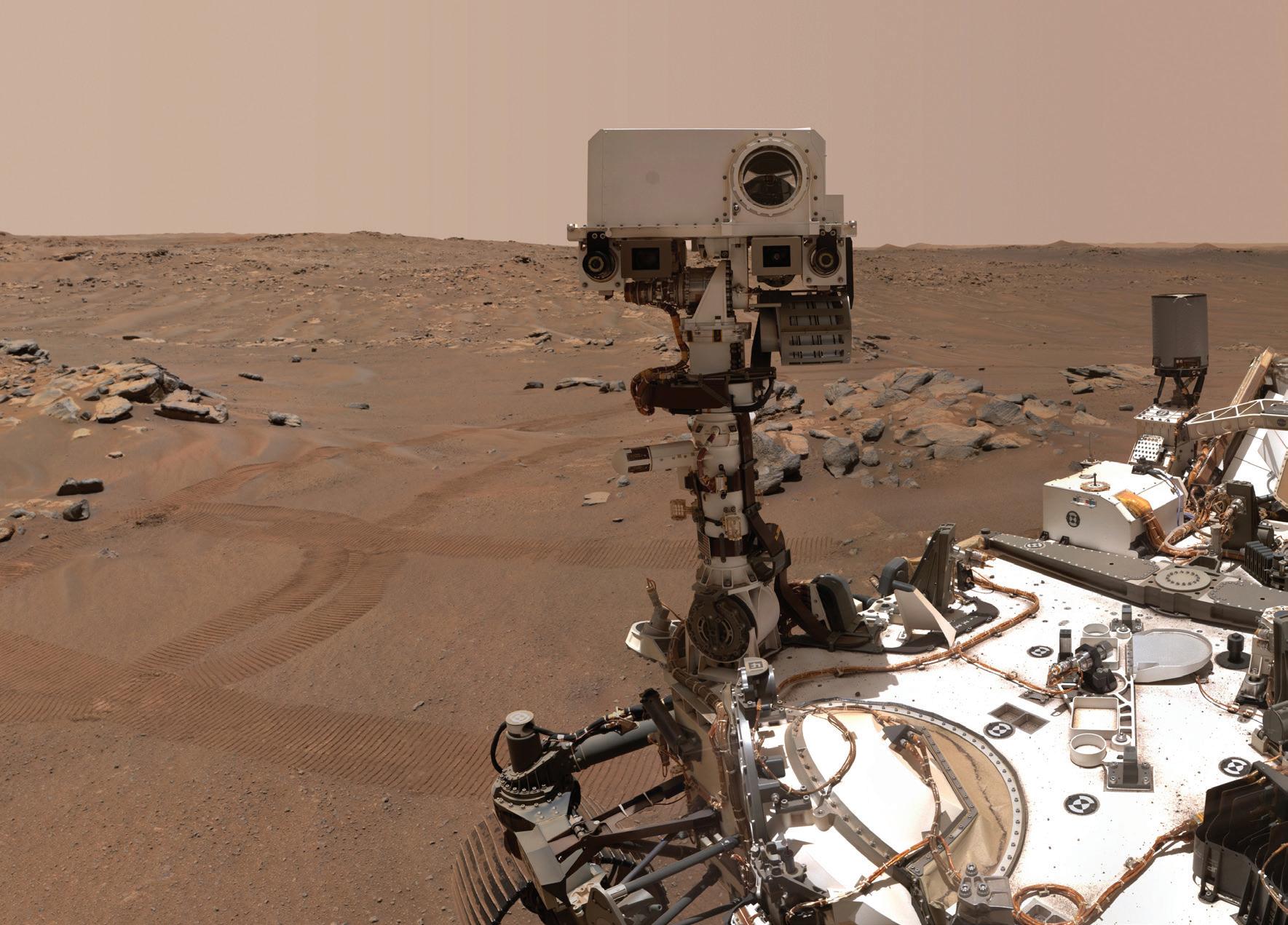

I-Health is also engaged in the Planetary Protection Center of Excellence Mars Sample Return (MSR) project (pages 18 and 19). The current MSR mission involves the acquisition (by the Perseverance rover) and return of scientifically selected Martian regolith samples for investigation in Earth laboratories. This mission defines sterilization parameters to both ensure scientific integrity of collected samples and prevent any forward (other celestial bodies) and backward (Earth) contamination.

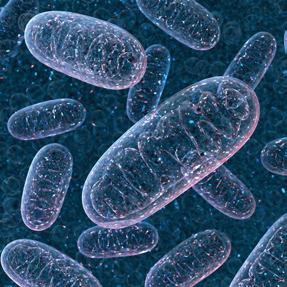

The human health and dementia research group considers all stages of human development and afflictions which primarily impact the neurons of the human brain, resulting in diseases that are presently incurable. I-Health research in this area includes improving outcomes for veterans with mild traumatic brain injury (pages 4 and 7), monitoring cognitive change (pages 5, 8, 9 and 26), determining the unique factors that impact cognitive decline in Hispanics (pages 24 and 25), and evaluating how mitochondria impacts neuron function and subsequent neurodegenerative diseases (pages 22 and 23).

Finally, technological innovations within the I-Health membership include the development of microfluidic devices for monitoring sickle cell anemia and malaria (pages 12 and 13) and using artificial intelligence to predict outcomes of gene mutations (pages 20 and 21). All-in-all, the contributions to human health described in Journey to Health are exciting and, in many cases, paradigm shifting.

Executive Director, Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention Professor, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry

Cammi Clark, Ph.D.

Contributing Writers and Copy Editors

Bethany Augliere, Shavantay Minnis, Judy Gelman Myers, Wynne Parry

Photographers

Wally Aime, Bethany Alex, Jenna Cicero, Alex Dolce, Jultmartin Eugene, iStock.com, Gregory Macleod, NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

Design and Graphics

Craig Korn, Katarzyna Bytnar

Notice: Reasonable requests should be sent to the Division of Research at least 20 days in advance via dorcommunications@fau.edu.

Daniel C. Flynn, Ph.D.

Vice President for Research 561-297-0777 fau.research@fau.edu

Gregg Fields, Ph.D.

Executive Director, Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention (I-Health) Co-Director, MCIFAU FDoH Cancer Center of Excellence

Professor, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry 561-799-8577 fieldsg@fau.edu

Member of the University Research Magazine Association

COVER DESIGN: FRENTUSHA, ARTACET / ISTOCK.COM, CRAIG KORN

To discover new treatment methods for veterans with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), Cheryl Krause-Parello, Ph.D., a professor and interim associate dean for nursing research and scholarship in FAU’s Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing, is going directly to the source — veterans.

With a $250,000 pilot award from the Eugene Washington Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Engagement Awards program, Krause-Parello is creating a project called Mind Over Matter (MOM) to learn and engage with the veteran population. Through the program she will lead a team of researchers and veterans to answer questions about living with mild TBI. The goal is to find treatment options that are effective, acceptable and meaningful to veterans whose daily tasks and capabilities are limited because of a TBI.

Krause-Parello is also the director of Canines Providing Assistance to Wounded Warriors, an initiative to advance the health and well-being of members of the armed forces.

In addition, a $123,800 gift from the Phil and Susan Smith Family Foundation, Susan A. Smith, and the Phil Smith Automotive Group has helped launch a new program called the FAU Veteran Canine Rescue Mission program, which matches FAU student veterans and alumni veterans with dogs from the Humane Society of Broward County, trained for service, emotional support or companionship. The program, which also includes a research component on the human-canine bond, will serve as a resource for more than 1,300 military and veteran students currently at FAU.

Day 1: Sample Day 2: Test

Four researchers recently earned a pilot grant for a project that allows them to use an anti-inflammatory drug to decrease damage to the heart muscles — a side effect of cancer treatment — while increasing death to cancer cells.

The leads on the project include:

In a first-of-its-kind study, FAU researchers determined that mice can distinguish the difference between a 2D image of an object versus the physical object itself.

The ability to recognize a 3D object after viewing an image is primarily found in humans and is known as picture-to-object equivalence. For the study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, Robert W. Stackman Jr., Ph.D., dean in FAU’s Graduate College, and professor in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Science, allowed laboratory mice to view photographs of a novel object for 30 seconds. The next day the mice were presented with a 3D version of that same object as well as something new. Turns out, the mice wanted to explore the object they previously saw in the photograph. Results from the study reveal that mice use higher-order cognitive processes to correlate a 3D object with the 2D image.

For Stackman, who is also a member of FAU Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention, FAU Stiles-Nicholson Brain Institute, FAU Jupiter Life Science Initiative, and the FAU Center for Complex Systems and Brain Sciences, the next step is to use the mice as a model to research visual perceptions and recognition.

ILLUSTRATION BY ROBERT W. STACKMAN JR., PH.D.• Shailaja Allani, Ph.D., associate scientist, Charles E. Schmidt College of Science

• Herbert Weissbach, Ph.D., Emeritus professor, Charles E. Schmidt College of Science

• Claudia Rodrigues, Ph.D., associate professor of biomedical science, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine

• Howard Prentice, Ph.D., professor of biomedical science, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine

Tarsha Jones, Ph.D., an assistant professor of nursing in the Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing, recently earned a $772,525 Career Development Award from the National Institutes of Health, which will help fund her efforts to improve health outcomes among young, racially- and ethnically-diverse, breast cancer survivors in South Florida.

Her research titled, “Decision Support for Multigene Panel Testing and Family Risk Communication among Racially/Ethnically Diverse Young Breast Cancer Survivors,” supports Jones’ further development to improve multigene panel testing and cancer risk-reduction among this population and promote family-risk communication among their at-risk family members.

The project goal is to contribute to the findings and testing of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer among diverse young patients.

Atthe cross section of neuroscience and psychology, Chad Forbes, Ph.D., digs a little deeper to better understand what’s going on inside the brain, including how the brain changes during stress or what happens when people experience biases and prejudices.

“Ultimately, what I’m studying are cognitive processes, such as memory or how the different regions of the brain communicate when you are trying to solve a difficult math problem,” said Forbes, an associate professor of psychology in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Science. Forbes is also a member of FAU’s Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention (I-Health), and associate director of FAU’s Stiles-Nicholson Brain Institute.

In addition, he recently co-authored a study in the journal Social Science & Medicine that examined the relationship between racial discrimination and negative physical health outcomes. “We found that if you experienced more bias in a given region, both Black and white patients were more likely to die from chronic stress-oriented diseases, but those relationships were stronger for Black patients,” he said.

To do such research, his lab, the Forbes Social Neuroscience Laboratory, combines standard psychology methods such as surveys and questionnaires, with neuroscience tools, like examining the brain’s electrical activity using an electroencephalogram test or MRIs.

Forbes, a first-generation college student, said he’s always been interested in human physical and mental health. “I’ve always been motivated to help others in whatever way I can,” he said.

Originally, he attended college with the plan to become a doctor. Yet, after earning a C in organic chemistry, he said he knew he would never get into medical school. “I really was kind of lost and didn’t know what to do, but I had taken this introduction to psychology class and loved it,” Forbes said.

Eventually, he earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology with minors in biology and chemistry at California State University Long Beach. He went on to earn both his master’s and doctorate degrees in social and cognitive neuroscience from the University of Arizona. Forbes also pursued postdoctoral training in cognitive neuroscience at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in at National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, both based in Maryland. Before joining FAU, he spent a decade as an associate professor in the department of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Delaware.

Now Forbes said he is excited by the opportunities provided by being an I-Health member, the way it facilitates interdisciplinary collaborations, and the chance to expand his research that wasn’t available to him before. “Being here and being a part of I-Health has been truly exciting,” he said. “I want to do good in the world.”

Few, if any, treatment options are available for those who have suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) — researchers at FAU want to change that.

Chad Forbes, Ph.D., is the principal investigator on a new $25,000 pilot grant funded by I-Health. In collaboration with three additional FAU researchers, the team will examine the effects of laser-light therapy on brain function in veterans who have suffered a mild TBI.

“One of the hallmark consequences of a TBI is inflammation, or swelling in the brain,” Forbes said. “And one hypothesis is that swelling affects a lot of cognitive function and brain function, but we still don’t really understand how.”

So, Forbes and his team want to determine if repeated exposure of this near infrared light at a certain frequency could reduce that inflammation. At the same time, they’ll be collecting data on the brain network during higher-order cognitive processes, such as “figuring out a really tough math problem,” Forbes added.

The other team members on the grant include:

Beth Pratt, Ph.D., assistant professor, Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing, faculty fellow, I-Health, and associate investigator, Canines Providing Assistance to Wounded Warriors (CPAWW)

Cheryl A. Krause-Parello, Ph.D., interim associate dean for nursing research and scholarship, Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing, faculty fellow, Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention, and director of CPAWW

Behnaz Ghoraani, Ph.D., associate professor, College of Engineering and Computer Science, faculty fellow, Institute for Sensing and Embedded Network Systems Engineering

Ruth Tappen, Ed.D., RN, FAAN, spent a lifetime ensuring nursing home residents and people with dementia live with dignity, more independence and quality of life through her research and innovative approach to care.

In honor of her impact on the nursing profession, Tappen, the Christine E. Lynn Eminent Scholar and professor in FAU’s Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing, recently earned the 2021 International Nurse Researcher Hall of Fame award at the 32nd International Nursing Research Congress in Singapore.

Her career began at Wagner College in New York, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in nursing, followed by a master’s and doctorate in

Tappen, Ed.D.nursing education at Teacher’s College, Columbia University, N.Y.

After earning her degrees, Tappen steered her career toward research, starting with work on a colleague’s grant at the University of Miami. “That experience opened my eyes to the great wide world of grant funding,” she said. “Not a grant for grant’s sake, but for the opportunity to do projects and studies we wouldn’t have had the resources to do otherwise.”

Tappen joined FAU’s faculty in 1995 and began integrating ethnogeriatric content (health care for older adults from diverse ethnic populations) into a nursing specialty track in the master’s program. She was also instrumental in obtaining a grant from

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to establish a doctorate in nursing practice degree program at the College of Nursing.

In addition, through a start-up award from the Administration on Aging, she founded the Louis and Anne Green Memory and Wellness Center on FAU’s Boca Raton campus. The Center has a statesupported diagnostic unit, adult day center and other activities and educational programs for people with memory disorders, their families and caregivers.

“I can remember when people with advanced Alzheimer’s disease were tied in a chair and ignored. No more. Here we treat people with dignity and respect, no matter how advanced the disease,” said

Tappen, who served as director of the center for seven years. “Our research tells us that people with memory disorders often know much more and can do much more than we typically give them credit for.”

Tappen regularly serves as a study panel member for National Institutes of Health (NIH) and is a member of a Veterans Administration Merit Review Panel.

Her latest research, funded by a $5.3 million award from NIH, involves testing an in-vehicle sensor system that gives older drivers warnings of early cognitive change. The system is comprised of cameras that follow the driver’s eyes and objects around the vehicle and another sensor placed under the seat that records how fast the driver is going,

how they do at night and in bad weather. The data will help researchers develop algorithms that detect early cognitive change.

She’s also collaborating on a device to predict falls before they happen. The team is using large datasets, wearable sensors, and electronic health records to monitor changes in people before they fall.

“We have to understand that these diseases aren’t happening to numbers. They’re happening to real people with real families who really care about them,” Tappen said. “Understanding that principle shapes the way we conduct our research.”

We have to understand that these diseases aren’t happening to numbers. They’re happening to real people with real families who really care about them.”

— Ruth Tappen, Ed.D., RN, FAANFrom left, Ruth Tappen, Ed.D., and Ximena Levy, Ph.D., collaborate on a $5.3 million award from the National Institutes of Health, which involves testing an in-vehicle sensor system that gives older drivers warnings of early cognitive change.

Rapid advancement in cancer therapy is making the prospect of longer, healthier lives a reality for more patients. But ensuring everyone a more hopeful future requires the field to face up to past oversights.

Historically, the studies that have fueled progress in cancer care have focused on white patients to the exclusion of others. A collaborative effort between the FAU and Memorial Healthcare System’s Memorial Cancer Institute (MCI), seeks to address this long-standing deficit.

“Cancer research, like the rest of medicine, faces a major challenge right now,” said Gregg Fields, Ph.D., executive director of the Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention (I-Health). “We know certain diseases, including cancer, hit some racial or ethnic groups harder than others, and that some treatment strategies aren’t equally effective for everyone.”

The partnership between MCI and FAU, which the state has designated as a Florida Cancer Center of Excellence, leverages the two institutions’ combined research and medical expertise to move toward a solution. Together, they are gathering and storing samples and information from predominantly Black or Hispanic patients — contributions that will fuel studies to better understand and treat this devastating disease.

The researchers plan to establish a collection that covers a wide range of solid tumors, which they will house in FAU’s Clinical Research Unit on the Boca Raton campus. Teams are already collecting specimens from two types of solid tumors, breast and pancreatic cancer, while the partners, along with Tampa General Hospital and the University of South Florida, are seeking funding to broaden their effort.

MCI’s patient population reflects the diversity of South Florida. Nineteen percent of patients are Black, and another 19% are Hispanic, so promoting

health equity in cancer care is a priority for the institute, said Luis E. Raez, M.D., MCI’s medical director and chief scientific officer.

“For many years, we assumed if a treatment works for whites, it works for everybody,” Raez said. “We were wrong, because there are tremendous disparities in cancer clinical outcomes among whites, Asians, Blacks and Hispanics.”

For example, a small study at MCI found that minority lung cancer patients fared more poorly than white patients when using a new immunotherapy drug that helps the body’s immune system fight the disease.

Social and economic determinants, such as income level or access to health insurance, can’t fully explain disparities like this, he said. “There are biological and genetic factors that need to be addressed,” he said.

To begin to correct this long-standing bias, researchers must make a concerted effort to reach out to people who are traditionally underrepresented in medical research and clinical trials.

With a $220,000 grant from the Community Foundation of Broward focusing on breast cancer, a team from MCI has already begun seeking patients. Those who participate receive screening and treatment, and they have the option of contributing blood, and, if they have breast cancer, tumor tissue to the research effort.

Once samples are collected, researchers at FAU will step in. They plan to search for genetic differences, such as changes in a single letter

of the DNA code, unique to Black and Hispanic women. By creating genetic profiles of patients and following how the women fare, researchers hope to better understand how genetic factors can play into disparities.

Their findings could help explain a racial paradox within this field: While Black women develop breast cancer slightly less frequently than white women, the disease is more deadly for them. The reasons appear quite complex, but research has implicated biology, including ancestry and the control of gene expression.

Researchers are also recruiting patients with a second type of malignancy: pancreatic cancer, which is among the deadliest form of cancer for anyone. For this project, FAU and MCI have joined forces with Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. At this New York lab, scientists are taking their studies of patients’ cancer cells a step further, by growing them into small, spherical replicas of tumors known as organoids.

They use these organoids to lay the scientific groundwork for a much-needed screening test for early-stage disease and a method for determining the most potentially effective treatment for a particular patient. Samples from South Florida patients will diversify the collection the New York researchers have on hand for this research.

There’s still a lot to be done, but Fields said he is optimistic about what patient contributions today could mean for the future. “What we’ve learned is that using samples from patients gives us much more accurate information, especially when it comes to treatment strategies,” he said.

We know certain diseases, including cancer, hit some racial or ethnic groups harder than others, and that some treatment strategies aren’t equally effective for everyone.”

— Gregg Fields, Ph.D.

Understanding how blood cells move throughout the body could aid Sarah Du, Ph.D., in the treatment and even prevention of life-threatening diseases like sickle cell anemia and malaria.

“A single drop of blood can tell us a lot,” said Du, a mechanical engineer and associate professor in the College of Engineering and Computer Science. “From an engineering perspective, I’m very curious about the electrical and mechanical properties of the red blood cells because they tell the body how much oxygen to carry and when there is low oxygen, it creates diseases.”

To do this, Du develops tools like biosensors and microfluidic devices, or very small devices, to study red blood cells. She uses these tools to understand the properties of blood cells and get as close to a single drop of blood as possible, she said. Her devices also mimic the natural flow and function of red blood cells, using electrical signals inside the device to measure blood activity.

“Unlike traditional petri dishes that can only examine steady non-moving cells, our devices can examine the blood flow, the oxygen concentration and the cell-to-cell interaction without being concerned that the natural movement will disrupt our findings,” Du said.

When Du has a drop of blood under her devices, she can determine how much oxygen passes through, and how rigid the red blood cells become when no oxygen is available, she said.

Since red blood cells need to be extremely flexible and easily transformed to deliver oxygen into the different organs for the body to function, Du’s devices can detect when the oxygen fails to move and how diseases like sickle cell anemia begin to progress.

“When we are looking at the difference between diseased blood cells and normal ones, the life span of the red blood cells is often shorter allowing us to know which disease to look at,” she said. “In sickle cell, for example, the lifespan is only 15 days compared to the 120 days of a normal red blood cells. This could be attributed to the much weaker mechanical properties.”

With this information, Du said one of her goals is to provide a rapid, patient-specific drug efficacy testing to improve the oxygen delivery in the blood of sickle cell patients and the other is to create a point of care at-home device for people. The latter is close to completion.

“Once we saw how this method was more improved than using a traditional microscope and petri dish to examine the mechanical properties of red blood cells and how it relates to diseases, we wanted to see if we can bring these testing methods to the patients and to the field,” Du said. “Now with a single drop of blood, we have biosensors inside portable disposable devices with a phone application that can test red blood cells to determine and monitor the state of the disease.”

Prior to Du’s work in red blood cells and creating devices to study their mechanical properties,

she studied fabrication techniques on how to make microfluidic devices in 2011 while earning her doctorate degree at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J.

She completed her postdoctoral studies in 2014 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass., where she continued learning about microfluidic devices as well as the properties of red blood cells.

Coming to FAU a month later in 2014, Du has since earned awards from the National Science Foundation for her portable smart sensor and application project and now with her methods for testing red blood cells using microfluidic devices and biosensors, she’s using it to work on other projects such as studying human organs with a chip.

Since malaria is a disease that can even target pregnant women, Du is targeting her efforts to support the placenta.

Using a microfluidic device, she said, and a micro sensing chip, they can create a mock version that simulates the placenta barrier of a woman with malaria disease.

“If we can capture a single cell from a placenta and examine it on a chip, we can compare how the malaria-infected blood, which can cause birth defects and sometimes death to the baby, behaves differently compared to normal blood,” Du said. “It’s a method that can contribute greatly to the health of women around the world.”

In 2020, more than 241 million people had malaria, and 627,000 succumbed to it, according to the World Health Organization.

In an effort to decrease the number of people who die each year from this life-threatening disease, Sarah Du, Ph.D., recently earned a $25,000 I-Health pilot award to create a device that diagnoses those affected with malaria.

Malaria is caused by a parasite that lives in mosquitoes. When an infected female mosquito bites a human, it then enters the bloodstream and infects and destroys red blood cells. Since this parasite has the potential to multiply in the blood and cause blood loss, Du’s goal is to research living and dead parasites found in malaria disease.

Du will collaborate with Andrew Oleinikov, Ph.D., professor of biomedical science in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, on the project titled “Development of a Microfluidic Cell Prism for Label-Free Cell Sorting Between Live and Dead Plasmodium Falciparum Parasites,” which will result in a tool that collects tiny amounts of blood on a microchip, called a microfluidic device.

Sarah Du, Ph.D.

Sarah Du, Ph.D.

AsSARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, spawns new variants in its race across the globe, scientists at FAU are working to better understand how it’s transmitted, how to design success into a clinical trial, and how different societies respond to a health emergency. Their research enhances global efforts to combat this pandemic and those that are sure to come.

When determining if infectious diseases like the flu or COVID-19 could be eliminated by human behavior rather than pharmaceuticals, it’s the economy that might matter most, according to a recent study by FAU researchers.

For Florida communities that struggled with health and social challenges before the COVID-19 pandemic, things are even worse now due to a higher risk of infection and death, according to a recent study published in the journal Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities

Lead author Patrick Bernet, Ph.D., associate professor in the College of Business, analyzed the Florida county COVID-19 infection and death counts reported through March 2021 and supplemented that data with socioeconomic characteristics and 2020 presidential results. Results revealed that Florida counties with more Black residents had disproportionately higher COVID-19 infection and mortality rates. The disparities are even more pronounced in counties with larger Republican vote shares. Bernet said he hopes this data helps inform policy decisions that allocate resources where they will do the most good and customize messaging to improve protective measures, such as vaccination.

Tuncer, Ph.D.The study, led by Necibe Tuncer, Ph.D., an associate professor in the department of mathematical sciences, Charles E. Schmidt College of Science, was recently published in the Journal of Biological Dynamics. Tuncer and collaborators compared two models, one that examined the impact of full social distancing and another that incorporated an economic component.

Results reveal that disease elimination might be possible, but it depends on the economy. According to the first model, if the entire population practices complete social distancing it’s possible to eliminate disease. However, that’s not realistic, according to the authors. The second model shows that if the economy is weaker than the social norms, elimination of the disease is only possible if the entire population practices complete social distancing. If the economy is stronger than the social norms, then elimination is possible with some portion of the population practicing complete social distancing at the expense of the economy.

Ph.D.Beyond safe and effective vaccines, it’s possible that studying the genetic code of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is also helpful to reduce serious illness and death, according to FAU researchers.

All viruses have the ability to mutate as they spread through a population, leading to variants. Viruses with RNA as the genetic material, like influenza and SARS-CoV-2, can mutate faster than viruses with DNA.

In a new study, published in the journal Lancet, and led by first author, Janet D. Robishaw, Ph.D., senior associate dean for research and chair of the department of biomedical science in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, results show studying the genome means detecting different variants well before they spread. It also generally improves understanding of which variants are circulating, where, and their impact, according to the study.

Early detection of a COVID-19 outbreak is important to save people’s lives and restart the economy. Since outbreaks depend to a large degree on people’s social behavior, an university-industry collaboration teamed scientists from FAU’s College of Engineering and Computer Science with researchers from LexisNexis, a global data analytics company. The team developed a deep-learning model combining data on people’s mobility — how much they move around by walking, cars or buses — with statistics on previous COVID-19 outbreaks, government policies and demographic information such as age. The results, recently published in Journal of Big Data, accurately predict county-level outbreaks in the U.S. two weeks in advance.

The findings show that when people move around, the virus reproduces more. Because an increase in mobility increases interactions between people, especially in areas with high population density, adding mobility data to forecasting models helps scientists estimate COVID-19 growth and evaluate the effectiveness of policies such as mask mandates, according to Behnaz Ghoraani, Ph.D., senior author of the publication, associate professor in the department of electrical engineering and computer science, and fellow of the FAU Institute for Sensing and Embedded Network Systems Engineering (I-SENSE).

The study also demonstrates that the age of a population impacts the spread of the virus: average daily cases decrease in populations that have more retirees (65 and older) and increase with populations that have more young people (14 to 44).

Using this model to predict an outbreak of COVID-19 two weeks in advance helps manage this pandemic, as well as future pandemics, by ensuring that healthcare facilities are well prepared for what’s to come.

Clinical trials are necessary for determining the safety and efficacy of a drug, vaccine or device, but they are costly and time consuming, according to researchers in the College of Engineering and Computer Science. The scientists recently developed a computational model that can predict whether a clinical trial will succeed or be withdrawn due to a variety of factors, including insufficient enrollment, lack of funding/resources and business/sponsor decisions. The model can help clinicians design trials that optimize their efforts and reduce resources.

The researchers built a testbed of 4,441 COVID-19 trials from ClinicalTrial.gov with the objective of creating features that characterize successful COVID-19 clinical trial reports. Four types of features (statistics, keywords, drugs and embedding) were formulated to represent each clinical trial. The features characterize each clinical trial by considering clinical trial administration, eligibility criteria, clinical study design (e.g., whether placebo groups are involved), drug types, study keywords, as well as embedding features commonly used in state-of-the-art machine learning. Results show that keyword features are most informative for COVID-19 trial prediction, followed by drug features, statistics features, and embedding features. The study was recently published in PLOS ONE

Xingquan “Hill” Zhu, Ph.D., senior author and a professor in the College of Engineering and Computer Science, points out that clinical trials involve a great deal of resources and time, including planning and recruiting human subjects. Being able to predict the likelihood of whether a trial might be terminated or not down the road will help stakeholders better manage their resources and procedures. Such computational approaches may even help society as a whole redirect efforts toward combating the global COVID-19 pandemic, he said.

Len Treviño, Ph.D.

Some nations have been more effective than others at curbing the spread of COVID-19 within their borders. To understand how some countries successfully protect the lives of their citizens during a pandemic, researchers at FAU’s School of Business, in collaboration with colleagues at other universities, combined insights from cross-cultural research, social psychology and public health literature to explain the factors that impact a nation’s response to an epidemic.

The study analyzed COVID-19 case data for the first three months of infection in 107 nations, along with factors such as stringency of government policies and how quickly they were implemented. The study was recently published in the Journal of International Business Studies

The researchers categorized countries according to whether they prioritize individual or collective behavior, the extent to which they

accept unequal distribution of power, status and authority (power distance), the extent to which they feel threatened by ambiguities (uncertainty avoidance), and whether they prioritize ego goals versus social goals (masculinity-femininity). The study showed that stringent government policies applied early on attenuated pandemic growth, and that this effect was more pronounced in collectivistic than individualistic nations, and in high rather than low power distance nations.

Len Treviño, Ph.D., director of international business programs in the College of Business, said he believes that countries should provide clear messages early on regarding the potential mortality and morbidity of a pandemic, and that in order to have the intended impact, the focus and content of these messages should be tailored to the nation’s cultural context. Nevertheless, Treviño and his coauthors argue that all countries should attempt to unify their citizens by pointing out that adhering to pandemic control measures and a healthy economy go hand-in-hand.

Public health efforts to stop pandemics like COVID-19 depend heavily on predicting how they spread. Borivoje “Borko” Furht, Ph.D., a professor in the department of electrical engineering and computer science in FAU’s College of Engineering and Computer Science, and director of the National Science Foundation Research Center, and his team collaborated with data analytics company LexisNexis to create a mathematical algorithm that models and tracks the spread of COVID-19 from the county level to the global.

Using big data about personal relationships, health center locations and known mechanisms for spread of the disease, the model looks forward, predicting infection from a given patient into the community, and backward, tracing verified infections to a possible patient zero.

“Let’s say someone gets COVID. In a matter of 20 minutes, we can see the whole network around this person — neighbors, friends, employees — so we can immediately start tracking who they may be in contact with,” Furht said. “Our mathematical model immediately calculates how far anyone is from this infected person and the possibility that they might get COVID.”

Furht, who is basing the COVID-19 algorithm on a previous successful model of Ebola, said the Global COVID-19 Spread Tracking project has been released as a publicly available open-source website.

By Bethany Augliere

By Bethany Augliere

In July 2020, NASA’s Perseverance rover was launched to Mars. Upon landing Feb, 18, 2021, it’s goal became to look for past and present signs of life. When samples obtained by the rover return to Earth, Gregg Fields, Ph.D., is part of a team to help understand how to break the chain of contact with the Martian environment, ensuring all Martian material is contained and no possible stowaways survive the journey to Earth.

“While the risk is extremely low of any uncontained material, one wants a welldeveloped and highly effective approach to ensure the neutralization of hypothetical stowaways,” said Fields, executive director of FAU’s Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention, and professor in the department of chemistry and biochemistry, Charles E. Schmidt College of Science.

The car-sized rover landed in the Jerezo Crater, a 28-mile-wide basin located in the planet’s northern hemisphere. Experts believe that around 3.5 billion years ago, a river flowed into

a body of water about the size of Lake Tahoe, which straddles the border of California and Nevada. This is one of the best places to search for signs of microbial life, as the ancient river could have collected and preserved organic molecules, according to NASA.

While the rover searches, it will use up to 43 sample tubes, most of which are set to return to Earth as early as 2031, as part of the Mars sample return campaign being planned by NASA and the European Space Agency. The spacecraft is equipped with seven instruments, 25 cameras — the most ever in deep-space exploration — and even a helicopter the size of a tissue box to take aerial images.

Before the rover was ever even sent to space, NASA and its engineers worked hard to prevent Earth’s microbes from potentially contaminating Mars. That way, scientists also know that any potential discovery of life did in fact, originate on the red planet. Upon the samples’ return, now the goal is to ensure that no uncontained or unsterilized material is returned to Earth.

Prior to FAU joining the team, the three laboratories working on this potential problem include the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory based out of California, Nelson Laboratories headquartered in Utah, and Johnson & Johnson based in New Jersey. In June 2021, when they needed complementary techniques for the analysis of proteins and their degradation products, they reached out to Fields, whose laboratory has studied protein behaviors for more than 30 years.

Currently, the idea is to seal the sample tubes in two redundant containers. This includes heat sterilization of the joint between the halves of the primary container at a temperature high enough to break down any external organisms or proteins. The question is what temperature is required and for how long.

To test this, the other laboratories send Fields heat-treated samples of a yeast prion protein. Then, Fields’ laboratory uses a combination of analytical techniques, such as mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography,

to look at how much of the protein sample has broken down. So far, he’s tested the protein treated at 350- and 450-degrees Celsius (662- and 842-degrees Fahrenheit) and will ultimately test protein samples treated at 500-degrees Celsius (932-degrees Fahrenheit). “500-degrees Celsius has been specified as the sterilization parameter, but my laboratory’s ongoing work provides possible flexibility if needed in engineering parameters,” Fields said. The goal is to

break the proteins down into the amino acid components, which are the building blocks of proteins.

As the samples are expected to return to Earth in about 10 years, Fields has time to continue experimenting. “Do I actually believe there are dangerous microorganisms and proteins on Mars,” Fields asked? “No, I really don’t. But we still have to protect against it by behaving at all times like there could be a hazard.”

While the risk is extremely low of any uncontained material, one wants a well-developed and highly effective approach to ensure the neutralization of hypothetical stowaways.”

— Gregg Fields, Ph.D

By Shavantay Minnis

By Shavantay Minnis

Raquel Assis, Ph.D., examines what happens to genes once they mutate. Do they evolve into traits like having red hair and freckles, or do they duplicate and delete to cause severe diseases, like cancer?

Using artificial intelligence (AI), Assis’ new approach trains machines to predict the outcomes of an altered gene. Her work creates a path for evolutionary biologists and other geneticists to develop better disease treatment approaches.

“Structural variations, or large-scale differences in our DNA, are key to both evolutionary adaptation and diseases like cancer or lung disease,” Assis said. “Our new machine learning methods will enable us to answer targeted questions about how structural variations drive evolutionary innovation.”

Assis, a faculty fellow in the Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention, and associate professor in the College of Engineering and Computer Science, recently earned a $1.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and a $596,571 grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) for this and other projects. She will develop machine learning techniques that use genomic data to predict the short term and long-term evolutionary outcomes of DNA differences in both humans and animals.

Think of those who are lactose intolerant, she said, it began as a mutation in the genes, where a majority of the population had problems digesting milk. But once it evolved, individuals were able to continue drinking milk without any real harm. Yes, it’s still a mutation, just not one that creates major problems like diseases, she said.

“Defining a gene’s function is hard to quantify, but with our machine learning algorithms we can gain insight into how gene functions evolve after duplications, inversions, and other largescale mutations,” she said. “These methods will also allow evolutionary biologists to answer an array of questions related to evolution across different species.”

When Assis began her research, she created computerized software programs to help researchers get a closer look at the connection between genes and traits. Her program could classify the functional outcomes of duplicate genes and other structural variations from patterns hidden in the genes.

She spent most of her efforts looking at the functional outcomes of large-scale variations or mutations like duplications, which create copies of existing genes. Such mutations can often lead to either an adaptation, such as a stronger immune response to a new pathogen, or a disease like cancer and diabetes.

“Because duplication is the most common type of structural variation observed in nature, much of my earlier work focused on developing approaches for learning about the evolution of duplicate genes,” Assis said. “Now I plan to design similar techniques for studying other important classes of structural variations.”

When Assis entered college as a first-generation student at the University of Florida, she started her studies in biology, where she learned about the evolution of genomes, which is the complete blueprint of all the individual genes in the human body. Her interest in the genome and other neuroscience courses led her to complete a bachelor’s degree in psychology and zoology in 2006, she said.

Her time as an undergraduate also led her to questions like “why is there so much variation within genes” and “what kind of software programs could study it,” she said. Realizing that these programs were not created yet, during her doctorate program at the University of Michigan in 2007, Assis began studying bioinformatics, a field that combines computer science and biology to study genomes. There she created her first computer software program called Bridges, which allowed her to identify and search for similarities in the DNA of one human to the next.

Once she earned her doctoral degree in 2011, Assis continued her study of genomes as a NIH postdoctoral fellow at the University of California,

Berkeley. During her time there she designed the first method for predicting the evolutionary outcomes of duplicate genes.

When she completed her NIH postdoctoral fellowship in 2013, the following year she started a research and teaching position as an assistant professor in the department of biology at Pennsylvania State University.

In 2019, she joined FAU and immediately continued her work in bioinformatics creating other methods to study structural variations. Now with a five-year NIH Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award and three-year NSF grant, Assis plans to further her work using machine learning to study the evolution of genes and determine other questions like how natural selection shapes the evolutionary trajectories of structural variations, she said.

“What I enjoy most about my research on structural variations is that it has the potential to create a bigger picture for scientists to view human diseases,” Assis said. “And much like our genes, this picture continues to evolve.”

By Shavantay Minnis

By Shavantay Minnis

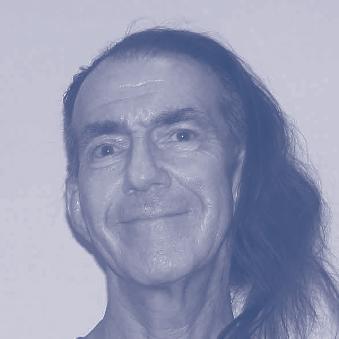

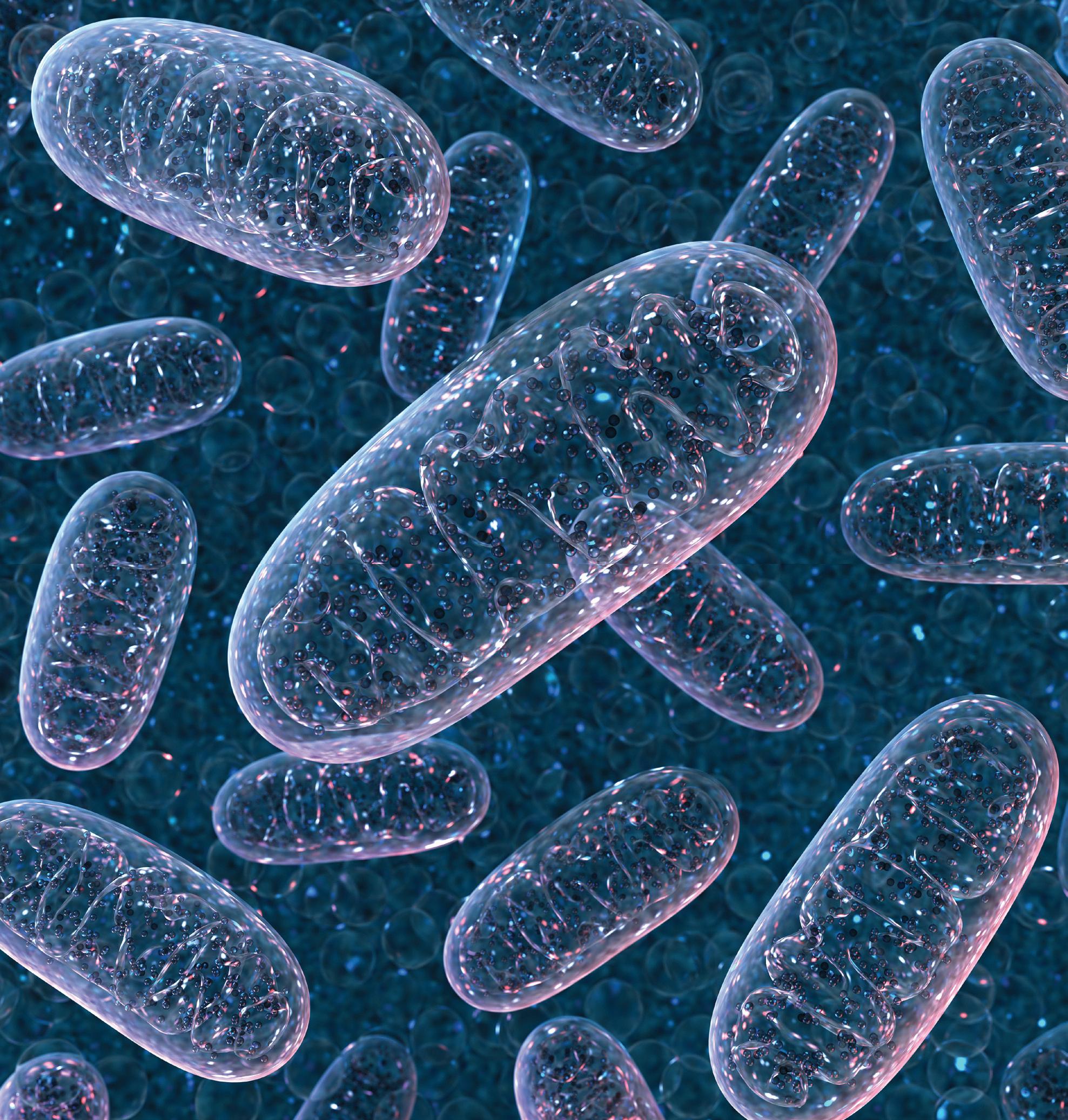

Studying how mitochondria support neurons could help Gregory Macleod, Ph.D., shed light on the mysteries surrounding neurodegenerative diseases.

Macleod, a professor in the Harriet L. Wilkes Honors College, and a member of the Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention, recently earned a five-year $1.8 million award from the National Institutes of Health to study how mitochondria — the powerhouses of a cell — support neuron function.

His research goal is to collect information that might be leveraged for therapeutic approaches to neurodegenerative diseases. “Mitochondria keep popping up as ‘persons of interest’ in neurodegenerative diseases,” Macleod said. “And, although ours is basic research, it’s needed to build on our understanding of what is already known about mitochondria and neurons.”

Working with Drosophila, a tiny fruit fly, Macleod examines genes and the effects of their mutations on mitochondrial movement inside neurons. Mitochondrial movement is critical to a neuron’s health, so when they cease movement, it disrupts neuron function leading to various disorders, such as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Macleod’s approach includes inserting or removing genes from the fly to determine which gene and which mutation is responsible for problems with mitochondrial movement, he said. A process assisted by a dozen graduate and undergraduate students.

“At the moment, we are examining 25 different genes because of their association with mitochondria and the plasma membrane, as we suspect that a number of them might be involved in arresting mitochondrial movement,” he said.

“Beyond mitochondrial movement, we are also interested in the role of mitochondria in the synthesis of the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain; glutamate,” said Macleod, who is also a member in the FAU

Stiles-Nicholson Brain Institute. “The synthesis of neurotransmitters is one of those overlooked facets of mitochondrial function that might yet explain the association between mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegenerative disease,” he said.

For his work on glutamate, Macleod and his team introduce engineered genes into the fly, which produce fluorescent proteins sensitive to glutamate. They can then measure the glutamate levels in the neurons with a specialized microscope that detects the fluorescence.

As glutamate levels increase in neurons, the fluorescent proteins become brighter. These measurements allow them to calculate how much energy the mitochondria spend making neurotransmitters, and also provide a benchmark level against which they can test for contributions from different genes towards matching glutamate levels with the demands of neurotransmission. “Neurons need to manage this process carefully as the release of excess glutamate will overexcite neighboring neurons, possibly leading to their death,” he said.

Gregory Macleod, Ph.D.Through the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience, Macleod has access to cutting-edge expertise in electron microscopy. The microscopes use electrons to capture images of biological materials giving unparalleled resolution of neurons and their mitochondria.

“They’ve given us a lot of assistance, and if it wasn’t for their help collecting data, we wouldn’t have been successful at landing our recent grant,” Macleod said.

Max Planck is also one of the reasons Macleod says he came to FAU eight years ago. Previously he’ was an assistant professor at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

“I’m excited about the opportunity to collaborate with researchers of this caliber, and to continue learning new methods that help us understand the pathology of diseases,” Macleod said.

By Wynne Parry

By Wynne Parry

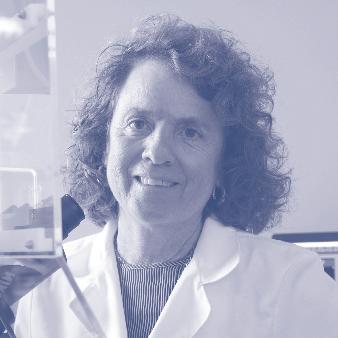

Researchers know age and genetic variation can increase susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease. Some, however, are wondering how a person’s life experiences — specifically culture and language — might contribute.

Idaly Vélez-Uribe, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow, and her mentor Mónica Rosselli, Ph.D., neuropsychologist, are working to understand how a unique set of factors shared by many Hispanics might affect their vulnerability, or resistance, to the

devastating decline in brain function associated with Alzheimer’s.

Much previous research on this disease has focused on white, non-Hispanic patients at the expense of other groups. However, representation matters in these studies because Hispanics, like African Americans, have higher rates of Alzheimer’s. What’s more, Hispanics are the most rapidly growing racial or ethnic group in the country.

Rosselli, a professor of psychology in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Science, and Vélez-Uribe suspect that experiences common among Hispanics — such as the stress of resettling in a new country, a culture of family involvement, and the ability to speak both English and Spanish — might alter their risk for abnormal cognitive decline and dementia, including that seen in Alzheimer’s. For example, some research suggests that bilingualism has a protective effect on the aging brain, a controversial possibility they are currently investigating.

In spring 2021, Vélez-Uribe was among four FAU researchers to receive funding from the Florida Department of Health’s Ed and Ethel Moore Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program. These grants support early-stage projects and, in Vélez-Uribe’s case, professional training for new investigators. The two-year, $99,051 grant will aid her goal of becoming an independent researcher.

So far, decades of intense scientific effort yielded only relatively modest improvements in treatment for Alzheimer’s, an irreversible brain disease that is among the most common causes of death in the U.S. Meanwhile, the stakes continue to grow.

“Because the U.S. has an aging population, Alzheimer’s is expected to place a growing burden — both emotional and financial — on society in the decades to come,” said Gregg Fields, Ph.D., executive director of the Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention. “We urgently need to develop more effective ways to detect and treat this condition.”

Researchers at FAU are attacking the problem from many angles, a handful of which are represented in these grants. For their part,

Vélez-Uribe and Rosselli are working on a federally-funded project, called the 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease & Research Center (ADRC), which recruits patients for longterm studies. ADRC includes a collaborative network of investigators from FAU, the University of Florida, University of Miami, Florida International University and Mount Sinai Medical Center. Half of the patients it enrolls are Hispanic.

In their research, Rosselli and Vélez-Uribe look for links between features of the brain, such as the size of certain regions within it, and cognitive function. These mental processes could include, for example, the ability to recall the right word, to remember facts or events, or perform activities necessary for daily living. Rosselli and Vélez-Uribe also investigate how these attributes may vary for older people of different ethnicities or who speak two languages.

Vélez-Uribe began researching Alzheimer’s after first studying the neuropsychology of bilingualism in younger people, an interest motivated by her own experience as a Spanish speaker. In her native Colombia, she could not tolerate the crass humor of the cartoon South Park. But her reaction changed when she watched the show in English. “I saw my husband watching it, and I found myself interested. I was even able to laugh at the jokes,” she said.

The experience became the basis for her master’s and doctoral research, which found evidence that bilingual people experience emotions less intensely in their second language. The move to Alzheimer’s felt like a natural continuation of this work in crosscultural neuropsychology, she said.

In April 2021, the state’s Ed and Ethel Moore Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program awarded a series of grants to the university. In addition to funding for Idaly Vélez-Uribe, Ph.D., and Mónica Rosselli, Ph.D., the grants are supporting the following research projects:

• Growing evidence suggests that cholesterol deficiency may contribute to aging-associated brain disorders including Alzheimer’s. Qi Zhang, Ph.D., a research assistant professor of biomedical science in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, is investigating whether or not rebalancing brain cholesterol can reduce or even reverse neurological degeneration.

• Using cells in culture and mice, Howard Prentice, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical science in the Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, will investigate the ability of sulindac, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, to protect against harmful neurological changes that occur in Alzheimer’s.

One in three older adults die with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias, but for certain minority groups, that risk is up to two times greater, and that risk is further increased for those in rural areas, according to Lisa Wiese, Ph.D.

To address a lack of early detection and management of dementia in rural and ethnically- and racially-diverse areas, Wiese, Ph.D., received a $250,000 grant from the Florida Department of Health’s Ed and Ethel Moore Foundation for Alzheimer’s Disease Research. “It’s a trifecta of increased disparities experienced by rural racially, ethnically diverse and older adults,” said Wiese, an associate professor in FAU’s Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing. “Our hope is to address those disparities for people facing greater risks of developing dementia in underserved communities.”

For this project, titled, “Optimizing Rural Community Health Through Interdisciplinary Dementia Detection and Care (ORCHID),” Wiese and collaborators will focus on a cluster of farming communities comprised of Belle Glade, Pahokee, Canal Point and South Bay, together known as the Glades.

Nursing students, who live near or in the Glades, will partner with faith health educators at various churches in the community to offer brain health education and

free health assessments related to Alzheimer’s risk, such as high blood pressure and diabetes. They will then follow residents identified with disease risk to connect with FAU College of Nursing adult gerontological nurse practitioners for more in-depth cognitive assessments, which are shared with primary care providers. Providers in the intervention group will receive dementia detection, diagnosis, management guidelines for disclosing dementia diagnoses, and strategies to address barriers to dementia diagnosis and care. Nursing students will support residents and their caregivers in connecting with available community resources, coordinated by Healthier Glades and Lake Okeechobee Rural Health Network.

Wiese and colleagues want to test if this community-based participatory research will increase rates of dementia understanding, diagnosis and management, thus creating — a model for decreasing dementia disparities in rural settings.

We’ve recognized that there are 12 potentially modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias,” said Wiese, including managing diabetes and high blood pressure, quitting smoking or getting enough sleep. “There is so much we can do to prevent or delay cognitive decline.” When it comes to dementia prevention, Wiese added, “early detection is the key. The earlier you intervene, the more successful those interventions are.”

Two FAU researchers were recently awarded a 2022 I-Health pilot grant for $25,000 to discover if adding an online exercise regime for older adults at risk of developing dementia in rural underserved communities can enhance brain health.

The co-principal investigators include Lisa Wiese, Ph.D., and JuYoung Park, Ph.D., a professor in the College of Social Work and Criminal Justice.

Through the project, titled “Testing a digital learning and online chair yoga intervention among rural underserved older adults at risk for cognitive decline,” students of Glades Central Community High School in Belle Glade, will partner with older adults to provide technology training. Through the grant, refurbished laptops are being supplied to the participants. One group of residents will participate in brain games, while another group will participate in virtual chair yoga sessions twice a week. The researchers will compare the two groups for change in activity levels and feelings of loneliness and isolation.

Researchers will follow-up at three and six months. “We’re excited about what we might find,” Wiese said.

Memorial Healthcare System’s groundbreaking partnership with Florida Atlantic University has led to a Florida Cancer Center of Excellence designation for Memorial Cancer Institute and FAU.

One of only five cancer centers in the state to earn this designation, our partnership combines FAU research and Memorial cancer expertise, providing patients with greater access to clinical trials.

Memorial Cancer Institute and FAU — stronger together in providing advanced cancer care for our patients.

Part of the brain of a living fruit fly maggot magnified 1000 times showing nerve cell bodies and their processes. A novel transgene generates different fluorescent colors in different nerve cells according to the identity of the splice isoform of a protein in that cell. Researchers’ ability to genetically modify fruit flies make them invaluable in studies into the genetic basis of neurodegenerative diseases.

GREGORY MACLEOD, PH.D.

GREGORY MACLEOD, PH.D.