23 minute read

Fauquier Livestock Exchange barely missed a beat

Stan Stevens has worked at the Fauquier Livestock Exchange nearly three decades.

Quite a mouthful ….

Advertisement

What one grower has to say about local, “ “Our current context for many people has prioritized health and reliability over cheapness and convenience. Of course, I am the most biased opinion to be had, but I heartily concur. If you want the healthiest food for you and your family, the best source is from a local farmer you can know, who is raising food with practices that most imitate natural biological systems. Here at Whiffletree, that means animals are outside on continually fresh pasture, non-GMO feed, no antibiotics, no chemicals, and beef that is 100% grass-fed. (We call this eating) local and sustainable for health. But also, (we should) eat local for beauty. Part of what many people think is special and worth preserving in Fauquier County is the beautiful farmland. Exploration in any direction in Fauquier leads to green fields, babbling streams and peaceful forests. Many people do not have the luxury of all this beauty that we have all around us. seasonal eating (hint: it’s all good)

The best way to preserve farmland is to support farms that are producing the tastiest and healthiest food. When a farm is economically viable, they stay a farm.

Livestock sales critical to region

Fauquier Livestock Exhange's Stan Stevens explains how the local ag economy relies on a regular rotation of sales

Stan Stevens knows from experience the nightmare of spring, 2020 to a livestock producer.

“Offering these livestock sales is important to the community,” says Stevens, acting general manager at a sales facility in Marshall. “We have an agricultural base to this county. We have producers and growers, people with cattle, feeders, calves, some dairy cows, and they need a place to buy and sell.

“If we close for long, the ag economy suffers, and everybody loses.”

Stevens, who’s worked at the Fauquier Livestock Exchange nearly 30 years, says though their twicemonthly cattle and livestock sales are popular, their equipment sale is even bigger. “We missed our April sale because of COVID,” Stevens explains. “We’re having one in October, and it’ll be wild. The traffic will circle the block,” and he means a country block. “We sell everything from claw hammers to bulldozers. People will come from everywhere to buy, to sell, to trade, to talk.

“It’s been a strange year.”

He’s been acting manager since the prior general manager resigned. “This year, especially, you need a strong general manager, someone who’s out in the community,” says officer manager Shelley Merryman. “Even through COVID, we never closed. Everybody’s pitching in to keep these sales going for the farmers, to bring it back to what it was.”

“I look at it as a wake-up call,” Stevens says of the lockdown crisis. “I mean, you should have a garden, even just a few plants in pots on your porch if that’s what you can do. You should have a side of (local) beef in your freezer. We’ve got to go back to the self-reliance method, or we’re doomed.”

Cattle sales are scheduled Oct. 9 and 23, Nov. 13 and Dec. 11. A horse and tack sale is set Oct. 17. fauquierlivestockexchange.com

COURTESY PHOTO Jesse Straight

Your local farm purchases keep beautiful farms as your neighbors. Also, eat local for your economy. When you purchase from any independent, locally-owned business – including local farms – you’re putting your hard-earned money in the hands of other community members who are the most likely to care about our community. Let's fill up our community with people who live and work here – those are the people who are most likely to have our community's long-term interests at heart. – JESSE STRAIGHT

Whiffletree Farm, Warrenton

PHOTOS BY RANDY LITZINGER Mary Stright was known for playing childrens records on her record player in Room 3 at Bradley Elementary in Warrenton and formed a special bond with hundreds of kindergartens over her 34 years teaching, so much so that she’s routinely invited to graduations, weddings, and baby showers of former students

Kindergarten teacher Mary Stright recalls a career spent developing ‘future adults’ in the classroom

By Vineeta Ribeiro

Even at age 5, Mary Stright (born Mary Corica) knew she wanted to be a teacher.

Daughter of Italian immigrants – complete with the Ellis Island trunk, she used to line up her dolls and stuffed animals in a spare room upstairs as her pupils. She used a chalkboard, she says, to instill the early lessons to her first students.

Fast forward six decades, and Stright has just retired after 34 years in a real classroom, having traded stuffed animals for upwards of a thousand kindergarten students.

Stright routinely receives invitations to graduations, weddings and baby showers, proof of the continuing admiration of students. She even receives letters from the grandparents of children.

Stright has even taught the children of former kindergarteners. There have been a mother-son, a father-son and a father-daughter combo.

“Wow, I feel old,” she says, saying it is a privilege to carry education across the generations. Too, she’s taught all three children for at least seven families.

Stright was born in Johnstown, Pennsylvania in 1954. She studied at University of Pittsburgh, earning a bachelors in early childhood education and social work in 1976. 22 FALL 2020

Her first posting in education was directing a daycare center at Seton Hill University. She moved to Fauquier County in 1985, spending her career at Central Elementary and C.M. Bradley Elementary.

With such an extended career, it comes as no surprise Stright has often been the subject of essays devoted to “My Favorite Teacher” long after her students have left elementary school.

“Parents are partners in their child(ren)s’ education,” Stright maintains. She recalls the story of a young boy who came to her class as a retention. “This boy had an impish smile and a fun-loving nature, for which his wonderful family never made excuses.

“(I) fell in love with the child,” she says, though on occasion would have to send a behavior note home in his backpack.

The notes never seemed to arrive, Stright says. She and the mother did a little detective work and solved the mystery – “the boy was planting the notes in a bush on his way home from the bus.”

Soon, Stright earned the boy’s trust, and the bush was bypassed as a messaging system.

Mornings in Stright’s Room 3 began with journal writing, and, naturally, young students would finish their assignment quickly then begin a relentless chorus: “What do I do now?”

As with many things, Stright had an easy solution. She’d play a Hap Palmer relaxation record to time the task. For the duration of one song, the children were required to write. As Stright points out, even 3 minutes is an eternity for a 5 year old.

The record-playing worked so well that, by the end of the term, Stright says her students developed the patience and persistence to listen to an entire side of the record while they filled in details, drew backgrounds and progressed to writing entire sentences.

She recalls a school board member dropping by her class one morning and seeing the silent intensity and detailed efforts of the young pupils. “The

Mary Stright

Age: 65 Education: Bachelors - early childhood education and social work, 1976, University of Pittsburgh Schools she taught at: C.M. Bradley Elementary 1990-2019, Central Elementary 1985-1990, director of lab school at Seton Hill University, daycare director at Seton Hill University Family: Husband, John, 66. daughters Jeana, 35; Ashley, 32; Aimee, 31

board member assumed they were rising second-graders,” Stright says.

Stright reflects on the innocence of children who imagine that their teachers live at the school. “These children are amazing,” she says. “They love you unconditionally. The little flowers they bring you, notes of love, pictures of ‘you’ drawn with love – there is no better gift.

“I counted it as a personal failure” when a child was not developmentally ready to progress to first grade after a year under Stright’s tutelage. “There is no easy way to explain to a 5-year-old that he or she will be in kindergarten again while friends are walking across the hall to first grade.”

She likened early education to learning to walk: If a child was not developmentally ready to walk, there was no sense in trying to get him to run. "It's hard to put into words just how good Mary Stright is,” says Alison Apffel, for 17 years a bus driver for the county, and mother of Ethan Apffel, who was in Stright’s 2007 class. “She just always has been there for him.”

Kaleb Scott (class of 2014) and sister Kiki Scott (class of 2019), have fond memories of their kindergarten days. “Mrs. Stright made learning fun from the very start,” says Kaleb. “From the treasure chest to Clifford the big red dog, she went above and beyond to make kindergarten an unforgettable start to education.”

“Mrs. Stright taught me how to stay in the lines while coloring, and in life,” adds a more philosophical Kiki.

Their mother, Kristy WheelerScott, is also a big fan.

“Both of my children were fortunate to be called Room 3 friends,” Wheeler-Scott says. “Mary Stright is hands-down, the best of the best. She’s a gift and was born to teach.

“Not only does she set the groundwork for success in the classroom and academics, she nurtures and guides children to be good humans. (They) truly do learn all they need to know about life by being ... in Mary’s classroom. I’m forever thankful for her and the far-reaching influence she’s had.

“She has kept in touch with my children throughout their lives, celebrating their accomplishments and, almost 20 years later, we still anticipate opening the mailbox to find a card written in that distinct Mary Stright handwriting. She is a legend.”

Challenges

Stright recalls one of her biggest challenges was managing a classroom of children of varying ages and abilities. Some enter kindergarten at age 4, while others are about to turn 6. “The standards of learning for kindergarten are forever changing,” Stright says. But one thing remained constant: “These precious children come to you from many different backgrounds. They all are looking to be loved, accepted and made to feel welcome in a safe and positive learning environment.”

When she arrived in Fauquier County in the mid-1980s, the county had just instituted full-day kindergarten. Previously, Stright had been director of a “kindergarten lab” school at a college in Pennsylvania.

Through the years, Stright says, she’s learned to regard children not as kids but as adults in training. She hopes it will spread to home life: “Spend time with your children as a family, make traditions, show your love for them by your actions and read together daily.”

She adhered to her own advice with her own family: Stright and husband, John, raised three girls born in the space of four years: Jeana, Ashley, and Aimee. In their early 30s now, all three hold advanced degrees. One is an architect, another a social worker, and the youngest, an assistant direcAnnual Pirate Day at Bradley Elementary.

tor of university advising.

Although it was challenging to spend a full day with a roomful of youngsters and then come home to her own young children, Stright feels she was “fortunate to have a husband who valued education, consistency in discipline and showing love and commitment to our children.” Although he commuted from Fairfax County, he was the girls’ homework helper. “We were a team,” says Stright of the co-parenting model. “It is nice to have technology, but nothing takes the place of being actively engaged with your children.

“I tried to instill values, kindness, trust and a sense of well-being in each Room 3 friend,” Stright says. She taught through the years of fire drills and tornado drills, more recently adding earthquake drills and lockdown drills.

Stright remembers one of her students bursting into tears during a lockdown when the doorknob was rattled from the outside. It was just an administrator to ensure the door was properly locked, but Stright had to comfort her distraught pupils. “I was willing to lay down my life for any of those kids,” she says, tears welling up. “I mean, they’re your kids.”

In return for her work year after year, Stright received hugs, smiles, greetings and expressions of “I love you” before the children left. “[These things] don’t come with a price tag. There is no better gift.”

Stright regularly is invited to the graduations of her previous students.

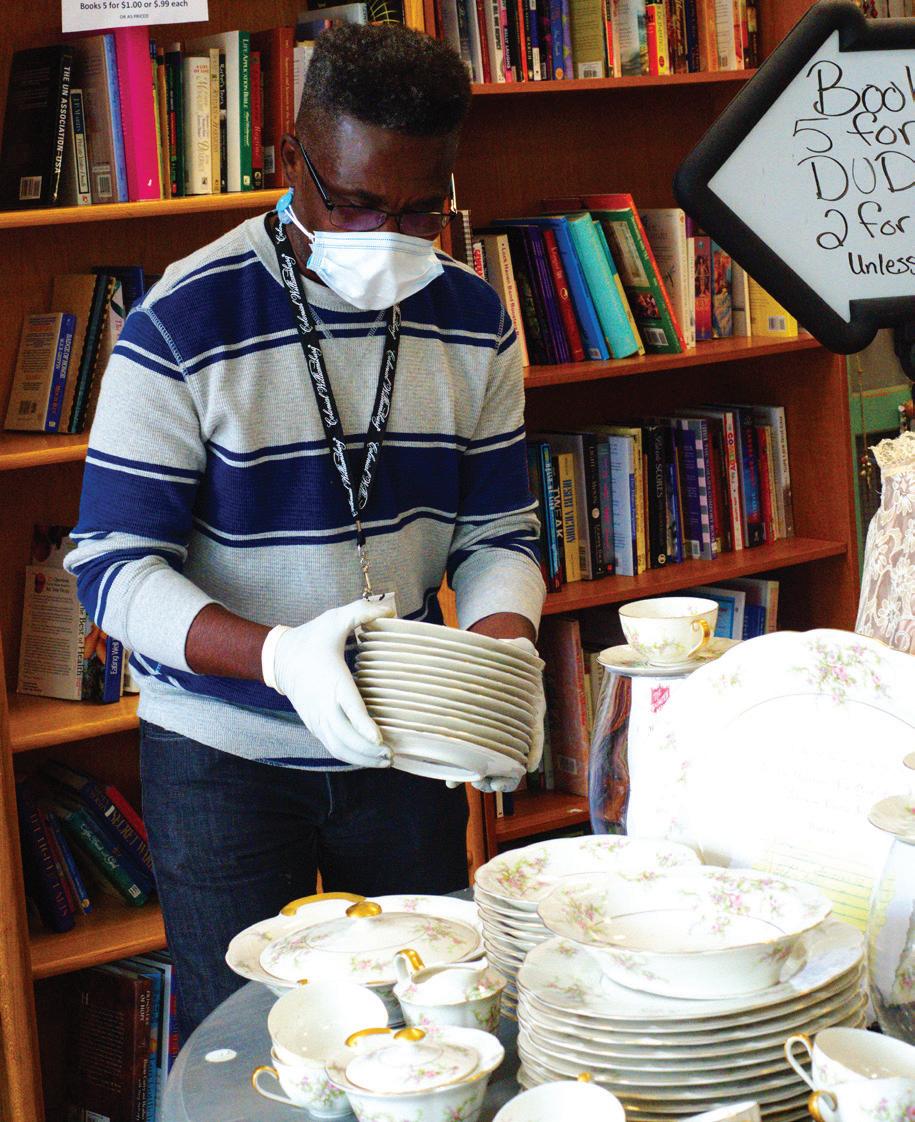

Salvation for your table setting design this season

Fun finds at Fauquier’s Salvation Army

The keys to setting an elegant dinner table are texture, layers and colors.

The autumn season in the Piedmont rolls in with reds, yellows and oranges, and your dining choices can reflect the new hues.

“It doesn't have to cost a fortune to set handsome table (from finds) at the Salvation Army,” says Warrenton Salvation Army store’s Christmas Hargrove. An added benefit, purchases “support the community.”

Expert tips for a festive fall table:

• A colorful table runner adds flair and elegance (you don’t have to buy one – a scarf from your wardrobe can work, or a fabric remnant can be neatly trimmed as a stand-in.) • A low centerpiece makes conversation easy. • Anchor the centerpiece with seasonal items (small pumpkins, bird feathers tucked in a decorative jar or vase, a bowl of unhulled nuts.) • Plate “chargers” take it from family supper to fine dining – the Salvation Army has lots of boldly colored stoneware plates that can easily serve as chargers, or use rattan placemats to elevate the experience. • Place dinnerplates on top of the chargers for Warrenton’s Salvation Army is a treasure trove of finds for the fall dining table. This set of Haviland china was listed for $40 for 48 pieces.

presentation during cocktail hour; swap them out for pre-plated salad plates when dinner starts. • Move it up another step and use folded cloth or

linen napkins – matching or not. • Fun placecards can be made from found items in your own yard or from hiking in the area. One idea is to write your guests’ names on small flat rocks with a dark Sharpie; or find colorful fallen leaves from trees and write names on those. Set the placecards on top of each dinner plate. • Add candle tapers or votive candles if desired, or use an array of battery-powered candles if preferred. * Make wise silverware choices when setting your table. While placing all utensils on the table before serving your meal may meet Emily Post etiquette standards, to be honest, a table meant for 10 set for 12 can get rather tight. • To keep your table orderly, consider bringing fresh utensils with each course, like a fine dining restaurant. Serve individual salad or hot appetizer plates with a salad fork (place the plates right on the charger you’ve pre-set.) When you clear places, take utensils away, swapping for the main course plate and a fresh knife and dinner fork. • Clear the dinner dishes after everyone has finished (don’t rush this) and settled into conversation. Pause production (again, take a cue from high-end restaurants - there’s a lot of careful timing involved) before serving dessert and offering coffee, tea or after-dinner aperitifs. • Bring in dessert plates or bowls with the appropriate silverware and include a teaspoon if serving coffee.

COME ON IN TO STOKES AND FIND THAT PERFECT PAIR!

WORK BOOTS LOGGERS COWBOY BOOTS

King Toe Steel Toe Too!

$139.99

Steel Toe Waterproof

Comfy

$114.99 $179.99

$119.99

HIKING BOOTS

$134.99

LADIES COWBOY BOOTS

$74.99

$129.99 $119.99 Teal or Pink $129.99

KIDS COWBOY BOOTS

KIDS LOGGERS RIDING BOOTS

DINGO $109.99 Black or Brown $136.99

KIDS SNOW BOOTS

$44.99 9 1/2 to 2 1/2

$34.99 9 1/2 to 5 1/2 Square Toe $36.99 Pink

BOYS & GIRLS HUNTING BOOTS

Close Out $64.99 Now $49.99 GIRLS $24.99 BOYS $26.99

$134.99

$119.99 SPECIAL

$84.99 $84.99

LADIES WORK BOOTS

$124.99 $99.99 SPECIAL

$94.99 Steel Toe Also

HUNTING BOOTS

$84.99 SPECIAL $179.99 SPECIAL

Stokes General Store Co., Inc.

“At The Bridge” • 533 E. Main Street, Front Royal, Va.

STORE HOURS: Mon.-Thurs. 8:30am-6pm Fri. 8:30am-6pm • Sat. 8:30-6pm 540.635.4437 Sunday 10am-4pm 1.800.252.1162

Food

LIFE & STYLE Wine

WAY BEYOND EATING AND DRINKING

The best thing since sliced bread? Pull-apart rolls.

•Follow the food system, literally, farm to fork •Mother Fudger Kim Sayermarsh has great taste when it comes to pleasing the palate

Squashed Is pumpkin a fruit? We’re questioning everything. Characteristics of vegetables: Typically prepared in a savory manner, vegetables are the leaves, roots and stems of They're not just for summer a plant, such as celery, potatoes and broccoli. Seeds grow separate from the part that is eaten. anymore. Try these tips for Characteristics of fruits: a cool fall crop of storage Fruits contain seeds in or on their flesh. Fruit seeds are eaten along with the flesh of the item. squash and holiday-ready summer squash. Unlike with seeds pumpkins, gourds and more of summer squash, seeds of most winter squash, such as pumpkin By Sandy Greeley seeds, can be roasted for snacks. Because of their tough skin, When your kids complain about being forced to eat their vegetables, point out that squash is actuwinter squash can be stored for long periods of time in a dark, ally a fruit. cool cupboard.

Botanically speaking, the yellow Historians sugand green fruits of this low-growing gest squash plants rambler come in numerous sizes, originated in Central America, shapes, colors, textures, even seathough their relatives also presons. Summer squashes include Edible sumably grew in Africa and Asia. zucchini, yellow crookneck, patand beautiful, squash But historians do attribute to Centypan and others. Winter squashes blossoms are part of tral Americans the knack and skills – harvested in the fall – include the payoff of planting of domesticating squash, probably butternut, acorn, spaghetti squash, fall-fruiting squash varieties around 10,000 BCE. pumpkin and more. Winter squash are harvested in like spaghetti squash, acorn squash and pumpkins. Records confirm that explorer Christopher Columbus took squash the mature stage when the outer back to Europe, where it spread in skin becomes tough. This makes them usually popularity from Spain and Portugal. harder to peel and the inside flesh requires lonItalians take credit for creating the hybridized ger cooking times; the skins are not eaten as with zucchini squash in the 19th century near the area

PHOTO BY LEAH CHALDARES Acorn, butternut and delcotta illustrate some of the many shapes, size and colors squash come in.

of Milan. The zucchini returned to America in the early 20th century, where it has since become a staple of the American kitchen.

To extend the storage time for winter squash, make sure to cure your autumn harvest. Curing concentrates natural sugars and causes the skin to harden, helping stored squash resist rot.

Curing takes 10 to 14 days of simply letting the squash sit in a warm place with good air circulation. Set squash on an elevated rack or mesh frame—chicken wire stretched across a frame or a window screen will do.

Cure blue hubbard, buttercup, butternut and spaghetti squash. Acorn squash is a winter squash that should not be cured.

Store cured squash in a cool, dark, dry place. Don’t store squash near apples pears or other ripening fruit. Ethylene gas will cause rot. Winter squashes can store up to six months if handled correctly.

Graduation is no time to learn you haven’t saved enough for college.

For a free, personalized college cost report, contact your Edward Jones financial advisor today.

Stanley M Parkes, AAMS®

Financial Advisor 400 Holiday Ct Suite 107 Walker Business Park Warrenton, VA 20186 540-349-9741

www.edwardjones.com

Member SIPC

Farm to fork – We’re pretty far removed from the food system

Learn the production schedule In chickens, as in other sources of what’s on your dinner plate of protein, knowing your farmer, and knowing their livestock living

By Amanda Gray, DVM conditions, is a winning strategy for health – your own, the ani

Few Americans remember the days when most mals’ and the earth’s. products were bought locally and not through the commercial supply chain. Eggs were gathered from a coop in the yard – or from the neighbor’s coop, and depending on which processor, and, therefore, inmeat came from the farmer down the road or the spection process, they use. Local buyers have the equivalent. The global economy hadn’t yet touched luxury of being able to literally go to a farm and local food sourcing, and everybody knew their food confirm the living conditions, and can even go to – where it came from, what it looked like, how it the processing plant to custom-order cuts. lived, and why it tasted so delicious. Pork: It takes pork seven months to go farm to

Because it was local. fork.

This disconnect makes it Local is best, both Industry standard is for no surprise how far we’ve become removed from the food chain. There’s a lot to understand about how a ham sandwich goes from a pig rooting in the mud in the corner of a pasture to thin-shaved slices sold over a franchise deli counter. Once you learn and understand animal husbandry, though, you grow to appreciate the producers and the livestock animals themselves. Take a look at the timeline involved in how products go from start to finish, sows to give birth in farrowing crates and for piglets to nurse there for three weeks before they are moved to an enclosed but roomy nursery where they stay for six to eight weeks. Commercial hogs are moved to finishing facilities where they are fed a specific diet to produce uniform muscle, and gain weight quickly. They stay there about 16 weeks before they processing. Again, federal or state inspectors ensure safety of for producers and processors • Fauquier's Finest Bealeton • Gadell's Processing (wild game only) Catlett • Lebanese Butchers Warrenton • The Whole Ox butcher shop Marshall • Blue Ridge Meats Front Royal • Adams Custom Slaughter Amissville from farm to table: meat before it is packaged and marketed for sale Beef: Beef takes two to three years to grow from birth to finish weight. Beef cattle spend six to eight months with their mothers – most places, spending their time on pasture. Small family farms often keep hogs – two to 20, even more – in a more natural, less industrial manner. Pigs are relatively low maintenance,

When weaned, young cattle go to what are called stockers or backgrounders. There, their diet consists of different pasture grasses, and they gain weight and build protein.

Production cattle then go to a feedyard for four to six months where they are fed scientifically formulated diets to build muscle, add weight and produce tender, flavorful meat. All cattle in feedlots receive regular care both from handlers and from veterinarians when necessary.

Grass-fed beef cattle remain on pasture, though many are fed supplemental grain or corn to tenderize the muscles and enrich the flavor of the meat.

Under federal or state jurisdiction, inspectors and veterinarians are at every meat packing plant in the nation to ensure appropriate handling and meat quality.

Finally, meat products go to buyers who market to grocery stores, or to value-added producers who make products like broth, jerky, smoked meat and processed deli cuts. Some meat is exported, some sold directly to restaurants, other meat is sold more locally via farmers markets, on

or sent for extra processing. farm sales and direct sales to local buyers. Grass-fed and pasture-raised beef is a speciality of

Small, local producers can sell their product Virginia’s Piedmont region, with cattle a big part of by the piece or by the whole (or half, or quarter,) Fauquier’s farm economy.

Safety first

USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service plays a pivotal role in maintaining the consistent, safe and fresh food supply we have all come to expect in the U.S. FSIS implements strict regulations for farms that produce or grow out animals, and check for drug residues, facility standards and transport standards. They are also responsible for the surveillance and elimination of food-borne disease outbreaks.

For farmers markets and smaller operations, this responsibility shifts to state and local authorities.

happy with a safely fenced enclosure with shelter and access to water around the clock and access to food either free-choice or fed at regular intervals.

Producers can choose to keep hogs on concrete – easier to keep clean, and less maintenance, or on pasture – which certainly yields a happier pig, since pigs crave nothing more than rooting in the dirt and mud with their snouts, but it is harder to keep clean and a couple hogs will decimate an acre of grass pasture and light woodland and brush within weeks.

Certain heritage breeds of pig – Mangalista, Duroc and others – take a bit longer to grow to processing weight, as much as 10-12 months. Their meat is much darker, almost red like beef, with excellent yield and commands a higher price per-pound since it costs more to produce.

Chicken: It takes five to seven weeks for a chicken to go from fertilized egg to a fried drumstick at your backyard picnic. Commercially grown broiler chicks hatch in hatcheries; within 72 hours, they are taken to what are called rearing or grow-out sheds where they mature.

Like all ground-nesting birds, baby chicks are born able to run and feed themselves; the mental image of a helpless baby bird in a nest, being fed for weeks by a pair of attentive adult parents is true for tree-nesting birds.

Chickens are fed different diets according to their maturity stage. Commercial breeds reach optimal processing weight at about seven weeks.

Some commercial chicken is sold labeled as “free-range,” but buyers do well to learn what this amorphous term actually means. For locally produced chicken, the term would usually mean a friendly flock of backyard poultry that comes when they’re called for hand-tossed treats, living with a lawn to scratch for insects by day and a snug, safe coop to sleep in at night.

But industrial-scale poultry producers are able to co-opt the term “free-range” though that’s absolutely not the reality. The USDA's definition of free range is that birds have “outdoor access” for part of the day during certain stages of their life. In some cases, this can mean access only through a “pop hole,” with no full-body access to the outdoors and no minimum space requirement. This means that a free-range label can be applied to chickens that have never actually been outside, only had “the opportunity” to go outside. FALL 2020 29